User login

An Algorithm for Managing Spitting Sutures

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

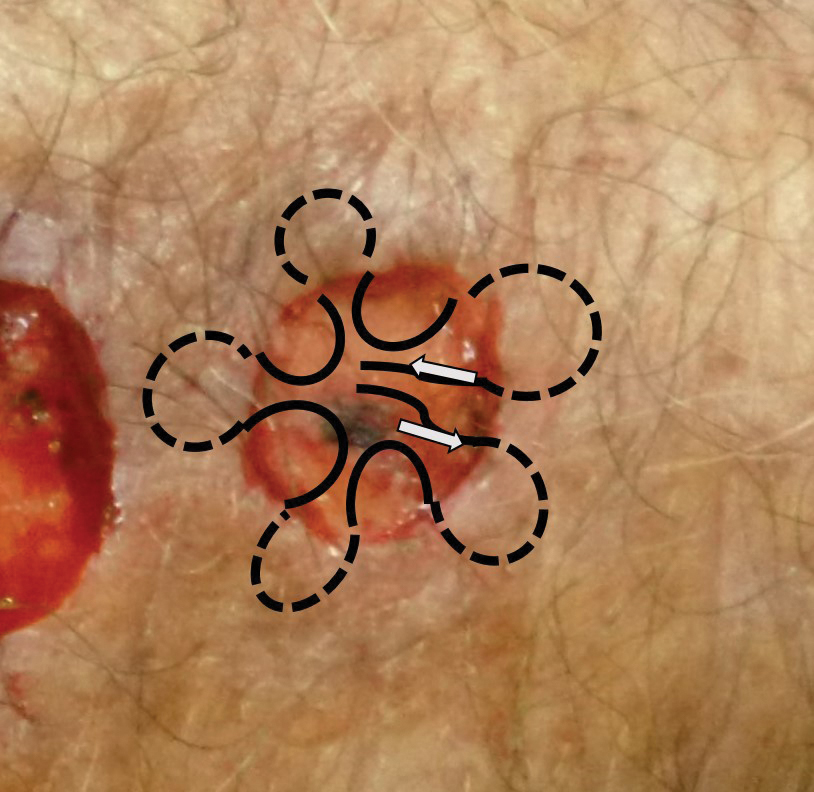

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

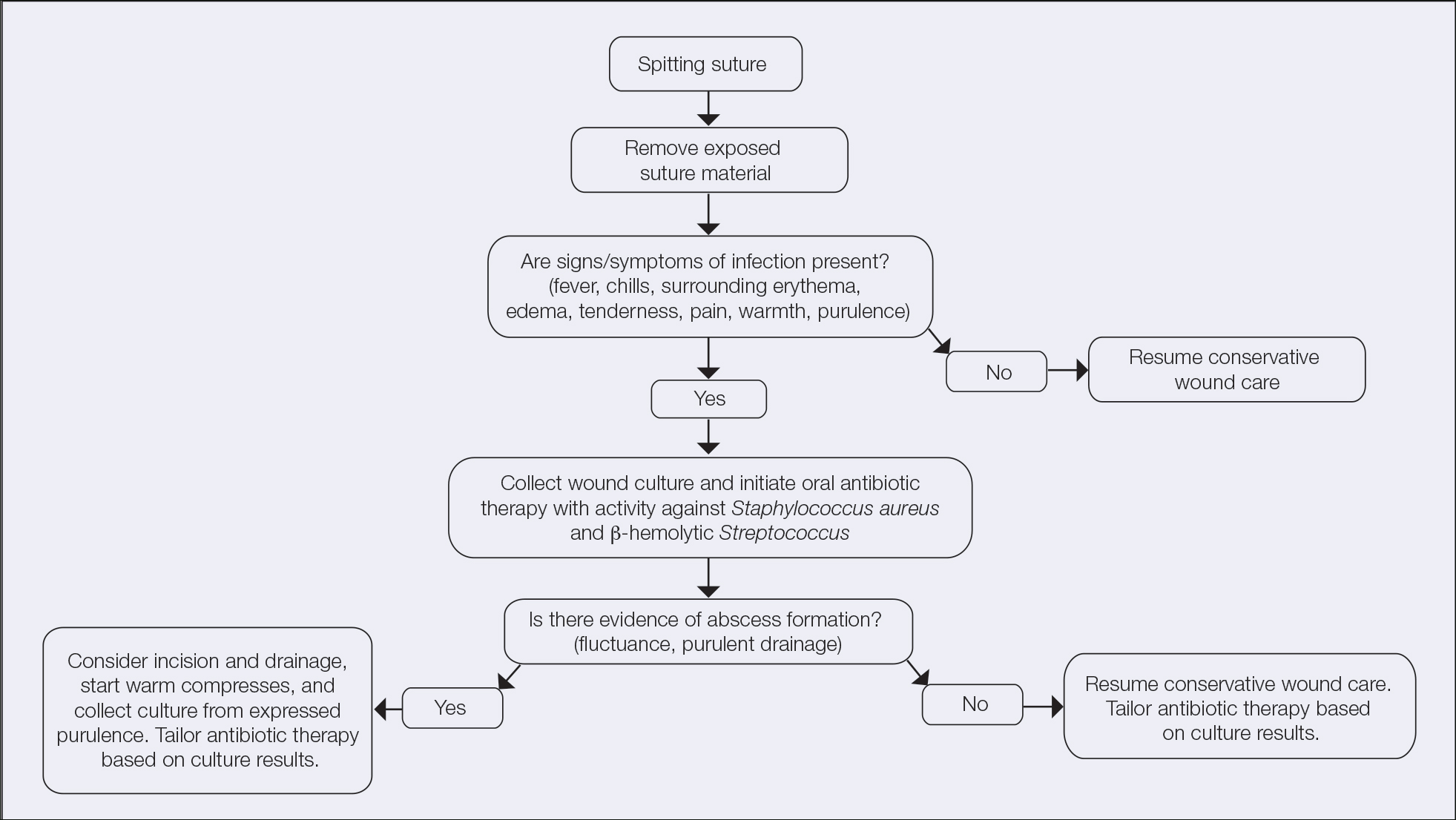

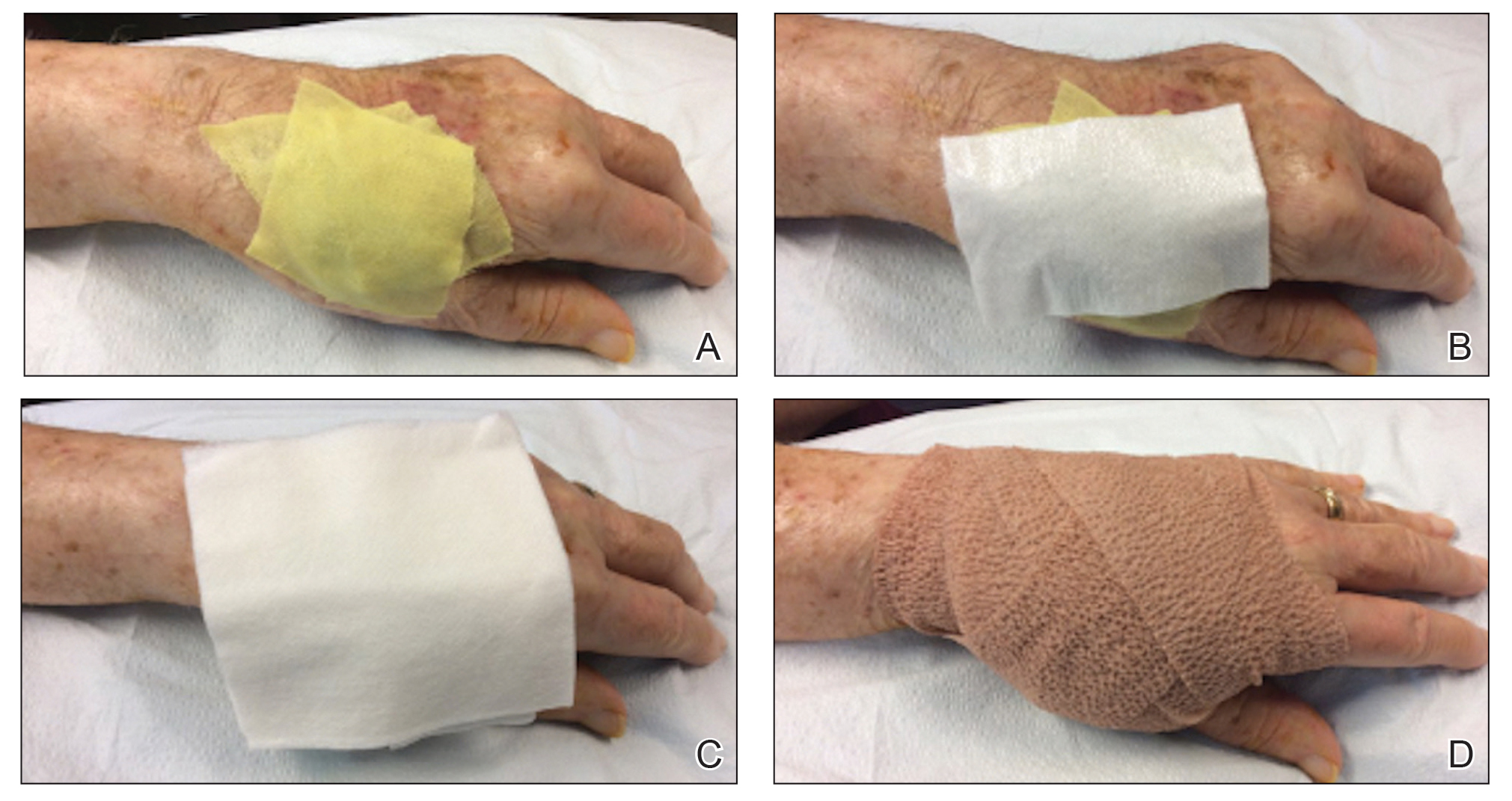

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570

Fulminant Hemorrhagic Bullae of the Upper Extremities Arising in the Setting of IV Placement During Severe COVID-19 Infection: Observations From a Major Consultative Practice

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

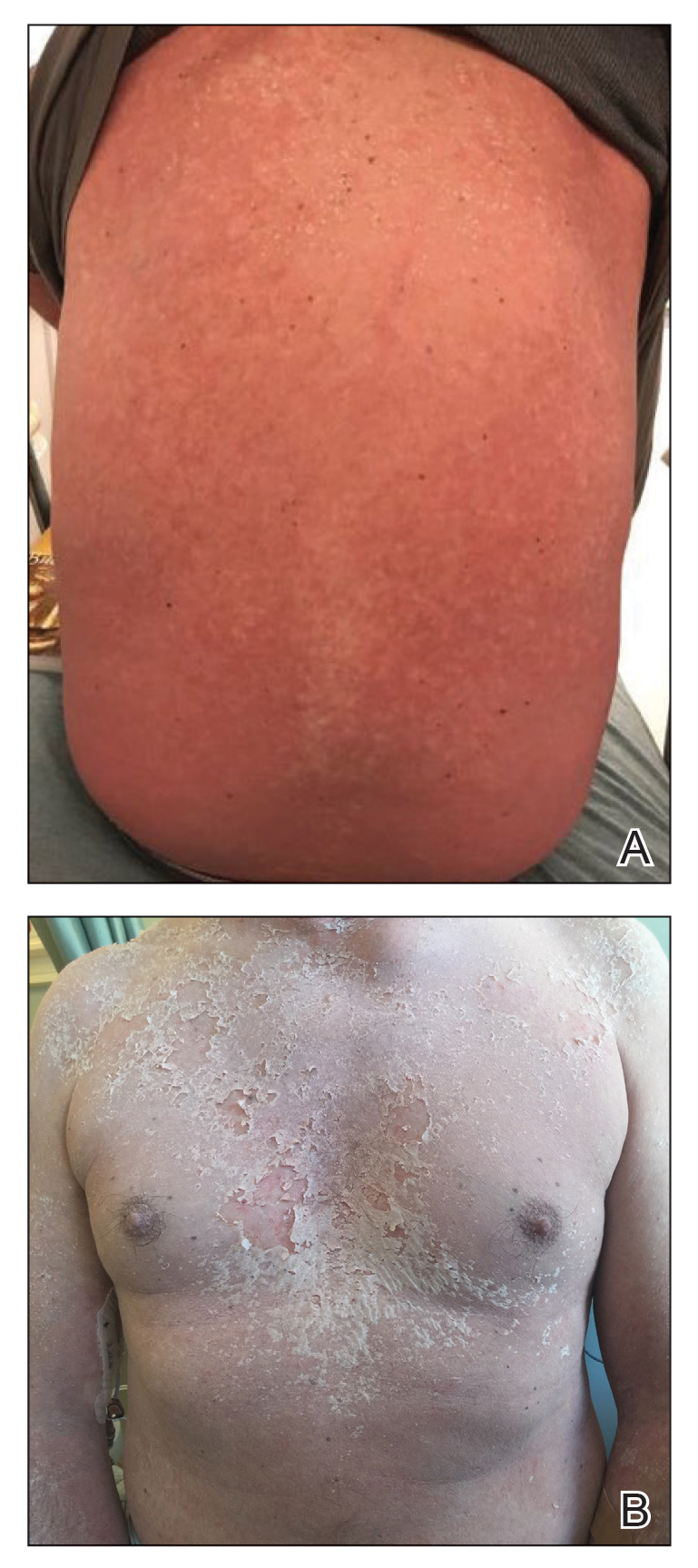

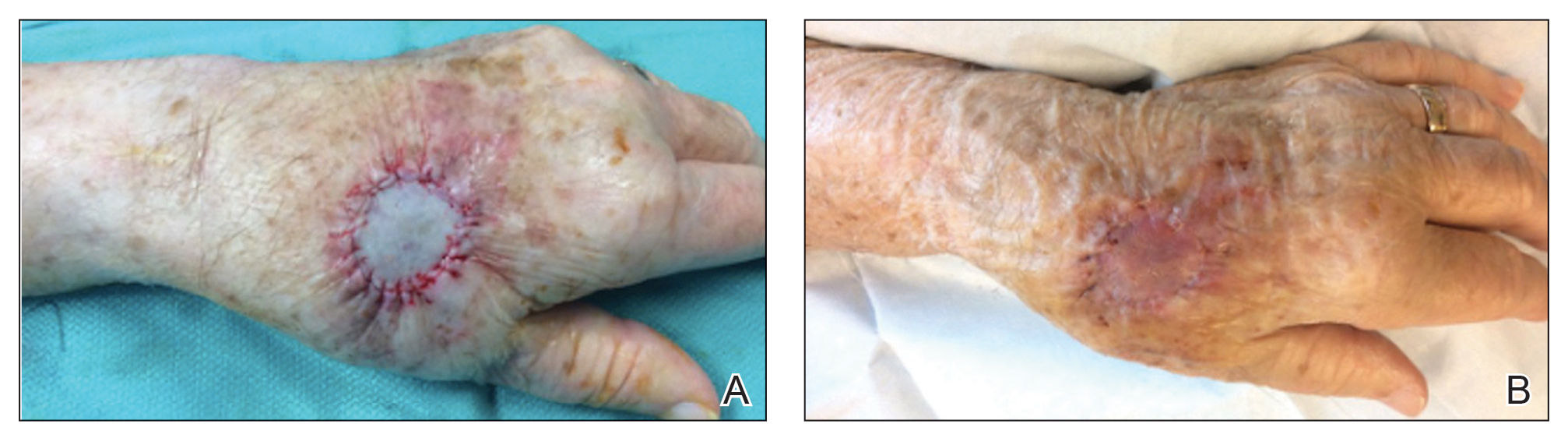

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

Practice Points

- Hemorrhagic bullae are an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 infection in hospitalized individuals.

- Although there is no reported treatment for COVID-19–associated hemorrhagic bullae, we recommend supportive care and management of underlying etiology.

Synthetic snake venom to the rescue? Potential uses in skin health and rejuvenation

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras,four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras,four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras,four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

Cutaneous Complications Associated With Intraosseous Access Placement

Intraosseous (IO) access can afford a lifesaving means of vascular access in emergency settings, as it allows for the administration of large volumes of fluids, blood products, and medications at high flow rates directly into the highly vascularized osseous medullary cavity.1 Fortunately, the complication rate with this resuscitative effort is low, with many reports demonstrating complication rates of less than 1%.2 The most commonly reported complications include fluid extravasation, osteomyelitis, traumatic bone fracture, and epiphyseal plate damage.1-3 Although compartment syndrome and skin necrosis have been reported,4,5 there is no comprehensive list of sequelae resulting from fluid extravasation in the literature, and there are no known studies examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications. In this study, we sought to evaluate the dermatologic impacts of this procedure.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review approved by the institutional review board at a large metropolitan level I trauma center in the Midwestern United States spanning 18 consecutive months to identify all patients who underwent IO line placement, either en route to or upon arrival at the trauma center. The electronic medical records of 113 patients (age range, 10 days–94 years) were identified using either an automated natural language look-up program with keywords including intraosseous access and IO or a Current Procedural Terminology code 36680. Data including patient age, reason for IO insertion, anatomic location of the IO, and complications secondary to IO line placement were recorded.

Results

We identified an overall complication rate of 2.7% (3/113), with only 1 patient showing isolated cutaneous complications from IO line placement. The complications in the first 2 patients included compartment syndrome following IO line placement in the right tibia and needle breakage during IO line placement. The third patient, a 30-year-old heart transplant recipient, developed tense bullae on the left leg 5 days after a resuscitative effort required IO access through the bilateral tibiae. The patient had received vasopressors as well as 750 mL of normal saline through these access points. Two days after resuscitation, she developed an enlarg

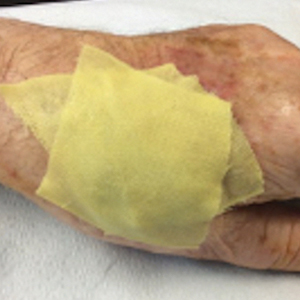

At a scheduled 7-month dermatology follow-up, the wound bed appeared to be healing well with surrounding scarring with no residual bleeding or drainage (Figure 2) despite the patient reporting a protracted course of wound healing requiring debridement due to eschar formation and multiple follow-up appointments with the wound care service.

Comment

The most commonly reported complications with IO line placement result from fluid infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue secondary to catheter misplacement.1,3 Extravasated fluid may lead to tissue damage, compartment syndrome, and even tissue necrosis in some cases.1,4,5 Localized cellulitis and the formation of subcutaneous abscesses also have been reported, albeit rarely.3,5

In our retrospective cohort review, we identified an additional potential complication of IO line placement that has not been widely reported—development of large traumatic bullae. It is most likely that this patient’s IO catheter became dislodged, resulting in extravasation of fluids into the dermal and subcutaneous tissues.

Our findings support the previously noted complication rate of less than 1% following IO line placement, with an overall complication rate of 2.7% that included only 1 patient with a cutaneous complication.2 Given this low incidence, providers may not be used to recognizing such complications, leading to delayed or incorrect diagnosis of these entities. While there are certain conditions in which IO insertion is contraindicated, including severe bone diseases (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomyelitis), overlying cellulitis, and bone fracture, these conditions are rare and can be avoided in most cases by use of an alternative site for needle insertion.2 Due to the widespread utility of this tool and its few contraindications, its use in hospitalized patients is rapidly increasing, necessitating a need for quick recognition of potential complications.

From previous data on the incidence of traumatic blisters with underlying bone fractures, there are several identifiable risk factors that could be extended to patients at high risk for developing cutaneous IO complications secondary to the trauma associated with needle insertion,6 including wound-healing impairments in patients with fragile lymphatics, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, or collagen vascular diseases (eg, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome). Patients with these conditions should be closely monitored for the development of bullae.6 While the patient we highlighted in our study did not have a history of such conditions, her history of cardiac disease, recent resuscitation attempts, and immunosuppression certainly could have contributed to suboptimal tissue agility and repair after IO line placement.

Conclusion

Intraosseous access is a safe, effective, and reliable option for vascular access in both pediatric and adult populations that is widely used in both prehospital (ie, paramedic administered) and hospital settings, including intensive care units, emergency departments, and any acute situation where rapid vascular access is necessary. This retrospective chart review examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications associated with IO line placement at a level I trauma center revealed a total complication rate similar to those reported in previous studies and also highlighted a unique postprocedural cutaneous finding of traumatic bullae. Although no unified management recommendations currently exist, providers should consider this complication in the differential for hospitalized patients with large, atypical, asymmetric bullae in the absence of an alternative explanation for such skin findings.

- Day MW. Intraosseous devices for intravascular access in adult trauma patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2011;31:76-90. doi:10.4037/ccn2011615

- Petitpas F, Guenezan J, Vendeuvre T, et al. Use of intra-osseous access in adults: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2016;20:102. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1277-6

- Desforges JF, Fiser DH. Intraosseous infusion. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1579-1581. doi:10.1056/NEJM199005313222206

- Simmons CM, Johnson NE, Perkin RM, et al. Intraosseous extravasation complication reports. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:363-366. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70053-2

- Paxton JH. Intraosseous vascular access: a review. Trauma. 2012;14:195-232. doi:10.1177/1460408611430175

- Uebbing CM, Walsh M, Miller JB, et al. Fracture blisters. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:131-133. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(09)80152-7

Intraosseous (IO) access can afford a lifesaving means of vascular access in emergency settings, as it allows for the administration of large volumes of fluids, blood products, and medications at high flow rates directly into the highly vascularized osseous medullary cavity.1 Fortunately, the complication rate with this resuscitative effort is low, with many reports demonstrating complication rates of less than 1%.2 The most commonly reported complications include fluid extravasation, osteomyelitis, traumatic bone fracture, and epiphyseal plate damage.1-3 Although compartment syndrome and skin necrosis have been reported,4,5 there is no comprehensive list of sequelae resulting from fluid extravasation in the literature, and there are no known studies examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications. In this study, we sought to evaluate the dermatologic impacts of this procedure.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review approved by the institutional review board at a large metropolitan level I trauma center in the Midwestern United States spanning 18 consecutive months to identify all patients who underwent IO line placement, either en route to or upon arrival at the trauma center. The electronic medical records of 113 patients (age range, 10 days–94 years) were identified using either an automated natural language look-up program with keywords including intraosseous access and IO or a Current Procedural Terminology code 36680. Data including patient age, reason for IO insertion, anatomic location of the IO, and complications secondary to IO line placement were recorded.

Results

We identified an overall complication rate of 2.7% (3/113), with only 1 patient showing isolated cutaneous complications from IO line placement. The complications in the first 2 patients included compartment syndrome following IO line placement in the right tibia and needle breakage during IO line placement. The third patient, a 30-year-old heart transplant recipient, developed tense bullae on the left leg 5 days after a resuscitative effort required IO access through the bilateral tibiae. The patient had received vasopressors as well as 750 mL of normal saline through these access points. Two days after resuscitation, she developed an enlarg

At a scheduled 7-month dermatology follow-up, the wound bed appeared to be healing well with surrounding scarring with no residual bleeding or drainage (Figure 2) despite the patient reporting a protracted course of wound healing requiring debridement due to eschar formation and multiple follow-up appointments with the wound care service.

Comment

The most commonly reported complications with IO line placement result from fluid infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue secondary to catheter misplacement.1,3 Extravasated fluid may lead to tissue damage, compartment syndrome, and even tissue necrosis in some cases.1,4,5 Localized cellulitis and the formation of subcutaneous abscesses also have been reported, albeit rarely.3,5

In our retrospective cohort review, we identified an additional potential complication of IO line placement that has not been widely reported—development of large traumatic bullae. It is most likely that this patient’s IO catheter became dislodged, resulting in extravasation of fluids into the dermal and subcutaneous tissues.

Our findings support the previously noted complication rate of less than 1% following IO line placement, with an overall complication rate of 2.7% that included only 1 patient with a cutaneous complication.2 Given this low incidence, providers may not be used to recognizing such complications, leading to delayed or incorrect diagnosis of these entities. While there are certain conditions in which IO insertion is contraindicated, including severe bone diseases (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomyelitis), overlying cellulitis, and bone fracture, these conditions are rare and can be avoided in most cases by use of an alternative site for needle insertion.2 Due to the widespread utility of this tool and its few contraindications, its use in hospitalized patients is rapidly increasing, necessitating a need for quick recognition of potential complications.

From previous data on the incidence of traumatic blisters with underlying bone fractures, there are several identifiable risk factors that could be extended to patients at high risk for developing cutaneous IO complications secondary to the trauma associated with needle insertion,6 including wound-healing impairments in patients with fragile lymphatics, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, or collagen vascular diseases (eg, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome). Patients with these conditions should be closely monitored for the development of bullae.6 While the patient we highlighted in our study did not have a history of such conditions, her history of cardiac disease, recent resuscitation attempts, and immunosuppression certainly could have contributed to suboptimal tissue agility and repair after IO line placement.

Conclusion

Intraosseous access is a safe, effective, and reliable option for vascular access in both pediatric and adult populations that is widely used in both prehospital (ie, paramedic administered) and hospital settings, including intensive care units, emergency departments, and any acute situation where rapid vascular access is necessary. This retrospective chart review examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications associated with IO line placement at a level I trauma center revealed a total complication rate similar to those reported in previous studies and also highlighted a unique postprocedural cutaneous finding of traumatic bullae. Although no unified management recommendations currently exist, providers should consider this complication in the differential for hospitalized patients with large, atypical, asymmetric bullae in the absence of an alternative explanation for such skin findings.

Intraosseous (IO) access can afford a lifesaving means of vascular access in emergency settings, as it allows for the administration of large volumes of fluids, blood products, and medications at high flow rates directly into the highly vascularized osseous medullary cavity.1 Fortunately, the complication rate with this resuscitative effort is low, with many reports demonstrating complication rates of less than 1%.2 The most commonly reported complications include fluid extravasation, osteomyelitis, traumatic bone fracture, and epiphyseal plate damage.1-3 Although compartment syndrome and skin necrosis have been reported,4,5 there is no comprehensive list of sequelae resulting from fluid extravasation in the literature, and there are no known studies examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications. In this study, we sought to evaluate the dermatologic impacts of this procedure.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review approved by the institutional review board at a large metropolitan level I trauma center in the Midwestern United States spanning 18 consecutive months to identify all patients who underwent IO line placement, either en route to or upon arrival at the trauma center. The electronic medical records of 113 patients (age range, 10 days–94 years) were identified using either an automated natural language look-up program with keywords including intraosseous access and IO or a Current Procedural Terminology code 36680. Data including patient age, reason for IO insertion, anatomic location of the IO, and complications secondary to IO line placement were recorded.

Results

We identified an overall complication rate of 2.7% (3/113), with only 1 patient showing isolated cutaneous complications from IO line placement. The complications in the first 2 patients included compartment syndrome following IO line placement in the right tibia and needle breakage during IO line placement. The third patient, a 30-year-old heart transplant recipient, developed tense bullae on the left leg 5 days after a resuscitative effort required IO access through the bilateral tibiae. The patient had received vasopressors as well as 750 mL of normal saline through these access points. Two days after resuscitation, she developed an enlarg

At a scheduled 7-month dermatology follow-up, the wound bed appeared to be healing well with surrounding scarring with no residual bleeding or drainage (Figure 2) despite the patient reporting a protracted course of wound healing requiring debridement due to eschar formation and multiple follow-up appointments with the wound care service.

Comment

The most commonly reported complications with IO line placement result from fluid infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue secondary to catheter misplacement.1,3 Extravasated fluid may lead to tissue damage, compartment syndrome, and even tissue necrosis in some cases.1,4,5 Localized cellulitis and the formation of subcutaneous abscesses also have been reported, albeit rarely.3,5

In our retrospective cohort review, we identified an additional potential complication of IO line placement that has not been widely reported—development of large traumatic bullae. It is most likely that this patient’s IO catheter became dislodged, resulting in extravasation of fluids into the dermal and subcutaneous tissues.

Our findings support the previously noted complication rate of less than 1% following IO line placement, with an overall complication rate of 2.7% that included only 1 patient with a cutaneous complication.2 Given this low incidence, providers may not be used to recognizing such complications, leading to delayed or incorrect diagnosis of these entities. While there are certain conditions in which IO insertion is contraindicated, including severe bone diseases (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomyelitis), overlying cellulitis, and bone fracture, these conditions are rare and can be avoided in most cases by use of an alternative site for needle insertion.2 Due to the widespread utility of this tool and its few contraindications, its use in hospitalized patients is rapidly increasing, necessitating a need for quick recognition of potential complications.

From previous data on the incidence of traumatic blisters with underlying bone fractures, there are several identifiable risk factors that could be extended to patients at high risk for developing cutaneous IO complications secondary to the trauma associated with needle insertion,6 including wound-healing impairments in patients with fragile lymphatics, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, or collagen vascular diseases (eg, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome). Patients with these conditions should be closely monitored for the development of bullae.6 While the patient we highlighted in our study did not have a history of such conditions, her history of cardiac disease, recent resuscitation attempts, and immunosuppression certainly could have contributed to suboptimal tissue agility and repair after IO line placement.

Conclusion