User login

Sirolimus reduced posttransplant skin cancer risk

Sirolimus protects organ-transplant recipients against developing skin cancer, reducing their risk by 40%, according to a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Dermatology on Jan. 20.

Recipients of solid organs are at three- to fourfold higher risk of developing cancer, compared with the general population, and the most common type they get is nonmelanoma skin cancer. The risk of developing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is 65-250 times higher in organ-transplant recipients. Drugs that reduce the growth and proliferation of tumor cells by inhibiting mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), including sirolimus, are believed to reduce this cancer risk, said Pritesh S. Karia of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, and his associates (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jan 20. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5548).

The investigators reviewed the electronic medical records of 329 patients (mean age, 56 years) who underwent organ transplantation at one of the two medical centers during a 9-year period and who then developed a cancer of any type. The study participants received renal (53.8%), heart (17.6%), lung (16.4%), liver (10.3%), or mixed-organ (1.8%) transplants. The most common index cancers they developed post transplant included cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (31.9%), basal cell carcinoma (22.5%), and melanoma (2.7%).

Of the 329 patients, 97 (29.5%) then received sirolimus, while 232 (70.5%) did not. During a median follow-up of 38 months, 130 of these patients (39.5%) developed a second posttransplant cancer. The sirolimus-treated group showed a reduction in risk for cancer of any type, compared with the group that did not receive sirolimus (30.9% of 97 vs. 43.1% of 232).

Nearly all (88.5%) of the second posttransplant cancers that developed were skin cancers, and sirolimus reduced the risk of skin cancers by 40%. The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year rates of skin cancer after an index posttransplant cancer were 9.3%, 20.6%, and 24.7% in the sirolimus group, compared with 17.7%, 31.0%, and 35.8%, respectively, in the untreated group, “thus demonstrating a lower risk for skin cancer with sirolimus treatment,” they said.

“Even for patients who have already had difficulty with skin cancer formation, mTOR inhibition appears to be of benefit. No difference in cancer outcomes was observable between sirolimus-treated and [untreated] groups because poor outcomes were rare,” Mr. Karia and his associates wrote.

These findings suggest that sirolimus chemoprevention should be considered for the subset of organ-transplant recipients who develop post-transplant cancer, they noted. The results also highlight the need for dermatologists and transplant physicians “to be aware of skin cancer history, coordinate regular posttransplant surveillance of skin cancers” in patients with organ transplant recipients, especially those with a history of skin cancer, and to communicate closely “as skin cancers form to consider reduction in immunosuppressive therapy or conversion to an mTOR-based regimen if skin cancer formation is of concern,” they added.

This study was supported by sirolimus manufacturer Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Mr. Karia and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Sirolimus protects organ-transplant recipients against developing skin cancer, reducing their risk by 40%, according to a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Dermatology on Jan. 20.

Recipients of solid organs are at three- to fourfold higher risk of developing cancer, compared with the general population, and the most common type they get is nonmelanoma skin cancer. The risk of developing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is 65-250 times higher in organ-transplant recipients. Drugs that reduce the growth and proliferation of tumor cells by inhibiting mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), including sirolimus, are believed to reduce this cancer risk, said Pritesh S. Karia of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, and his associates (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jan 20. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5548).

The investigators reviewed the electronic medical records of 329 patients (mean age, 56 years) who underwent organ transplantation at one of the two medical centers during a 9-year period and who then developed a cancer of any type. The study participants received renal (53.8%), heart (17.6%), lung (16.4%), liver (10.3%), or mixed-organ (1.8%) transplants. The most common index cancers they developed post transplant included cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (31.9%), basal cell carcinoma (22.5%), and melanoma (2.7%).

Of the 329 patients, 97 (29.5%) then received sirolimus, while 232 (70.5%) did not. During a median follow-up of 38 months, 130 of these patients (39.5%) developed a second posttransplant cancer. The sirolimus-treated group showed a reduction in risk for cancer of any type, compared with the group that did not receive sirolimus (30.9% of 97 vs. 43.1% of 232).

Nearly all (88.5%) of the second posttransplant cancers that developed were skin cancers, and sirolimus reduced the risk of skin cancers by 40%. The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year rates of skin cancer after an index posttransplant cancer were 9.3%, 20.6%, and 24.7% in the sirolimus group, compared with 17.7%, 31.0%, and 35.8%, respectively, in the untreated group, “thus demonstrating a lower risk for skin cancer with sirolimus treatment,” they said.

“Even for patients who have already had difficulty with skin cancer formation, mTOR inhibition appears to be of benefit. No difference in cancer outcomes was observable between sirolimus-treated and [untreated] groups because poor outcomes were rare,” Mr. Karia and his associates wrote.

These findings suggest that sirolimus chemoprevention should be considered for the subset of organ-transplant recipients who develop post-transplant cancer, they noted. The results also highlight the need for dermatologists and transplant physicians “to be aware of skin cancer history, coordinate regular posttransplant surveillance of skin cancers” in patients with organ transplant recipients, especially those with a history of skin cancer, and to communicate closely “as skin cancers form to consider reduction in immunosuppressive therapy or conversion to an mTOR-based regimen if skin cancer formation is of concern,” they added.

This study was supported by sirolimus manufacturer Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Mr. Karia and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Sirolimus protects organ-transplant recipients against developing skin cancer, reducing their risk by 40%, according to a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Dermatology on Jan. 20.

Recipients of solid organs are at three- to fourfold higher risk of developing cancer, compared with the general population, and the most common type they get is nonmelanoma skin cancer. The risk of developing cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is 65-250 times higher in organ-transplant recipients. Drugs that reduce the growth and proliferation of tumor cells by inhibiting mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), including sirolimus, are believed to reduce this cancer risk, said Pritesh S. Karia of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, and his associates (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jan 20. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5548).

The investigators reviewed the electronic medical records of 329 patients (mean age, 56 years) who underwent organ transplantation at one of the two medical centers during a 9-year period and who then developed a cancer of any type. The study participants received renal (53.8%), heart (17.6%), lung (16.4%), liver (10.3%), or mixed-organ (1.8%) transplants. The most common index cancers they developed post transplant included cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (31.9%), basal cell carcinoma (22.5%), and melanoma (2.7%).

Of the 329 patients, 97 (29.5%) then received sirolimus, while 232 (70.5%) did not. During a median follow-up of 38 months, 130 of these patients (39.5%) developed a second posttransplant cancer. The sirolimus-treated group showed a reduction in risk for cancer of any type, compared with the group that did not receive sirolimus (30.9% of 97 vs. 43.1% of 232).

Nearly all (88.5%) of the second posttransplant cancers that developed were skin cancers, and sirolimus reduced the risk of skin cancers by 40%. The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year rates of skin cancer after an index posttransplant cancer were 9.3%, 20.6%, and 24.7% in the sirolimus group, compared with 17.7%, 31.0%, and 35.8%, respectively, in the untreated group, “thus demonstrating a lower risk for skin cancer with sirolimus treatment,” they said.

“Even for patients who have already had difficulty with skin cancer formation, mTOR inhibition appears to be of benefit. No difference in cancer outcomes was observable between sirolimus-treated and [untreated] groups because poor outcomes were rare,” Mr. Karia and his associates wrote.

These findings suggest that sirolimus chemoprevention should be considered for the subset of organ-transplant recipients who develop post-transplant cancer, they noted. The results also highlight the need for dermatologists and transplant physicians “to be aware of skin cancer history, coordinate regular posttransplant surveillance of skin cancers” in patients with organ transplant recipients, especially those with a history of skin cancer, and to communicate closely “as skin cancers form to consider reduction in immunosuppressive therapy or conversion to an mTOR-based regimen if skin cancer formation is of concern,” they added.

This study was supported by sirolimus manufacturer Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Mr. Karia and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Sirolimus protects organ-transplant recipients against skin cancer.

Major finding: The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year rates of skin cancer after an index posttransplant cancer were 9.3%, 20.6%, and 24.7% in the sirolimus group, compared with 17.7%, 31.0%, and 35.8% in the untreated group.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 329 organ-transplant recipients who had already developed one cancer likely related to their immunosuppressive therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by sirolimus manufacturer Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Mr. Karia and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Hong Kong zygomycosis deaths pinned to dirty hospital laundry

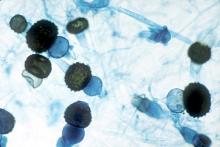

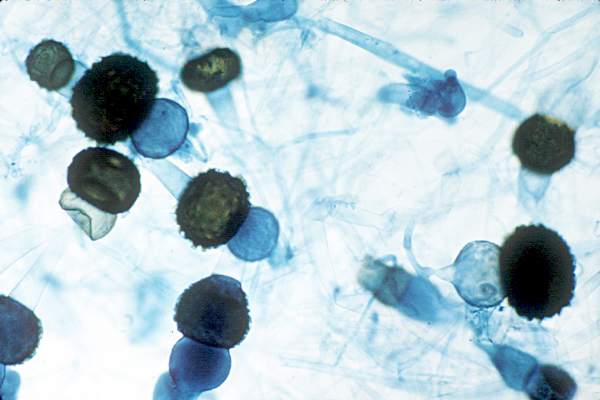

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Contaminated laundry led to an outbreak of cutaneous and pulmonary zygomycosis that killed three immunocompromised patients and sickened three others at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.

The contamination was traced to a contract laundry service that was, in short, a microbe Disneyland. It was hot and humid, with sealed windows, dim lights, and a thick layer of dust on just about everything. Washers weren’t hot enough to kill spores; washed items were packed while warm and moist; and dirty linens rich with organic material were transported with clean ones (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1006).

Of 195 environmental samples, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples. Freshly laundered items – including clothes and bedding – had bacteria counts of 1,028 colony forming units (CFU)/100 cm2, far exceeding the “hygienically clean” standard of 20 CFU/100 cm2 set by U.S. healthcare textile certification requirements.

Queen Mary didn’t regularly audit its linens for cleanliness and microbe counts. “Our findings [suggest] that such standards should be adopted to prevent similar outbreaks,” said the investigators, led by Dr. Vincent Cheng, an infection control officer at Queen Mary, one of Hong Kong’s largest hospitals and a teaching hospital for the University of Hong Kong.

It has since switched to a new laundry service.

The outbreak ran from June 2 to July 18, 2015, during Hong Kong’s hot and humid season, which didn’t help matters.

The six patients were 42-74 years old; one had interstitial lung disease and the rest were either cancer or transplant patients. Infection was due to the spore-forming mold Rhizopus microsporus. Two pulmonary and one cutaneous infection patient died.

Length of stay was the most significant risk factor for infection; the mean interval from admission to diagnosis was more than 2 months.

“Pulmonary zygomycosis due to contaminated hospital linens has never been reported.” Clinicians need to “maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,” the investigators said.

The U.S. recently had a cutaneous outbreak in Louisiana; hospital linens contaminated with Rhizopus species killed five immunocompromised children there in 2015.

“Invasive zygomycosis is an emerging infection that is increasingly reported in immunosuppressed hosts;” previously reported sources include adhesive bandages, wooden tongue depressors, ostomy bags, damaged water circuitry, adjacent building construction activity, and, as Queen Mary reported previously, contaminated allopurinol tablets.

Detecting the problem isn’t easy. None of the Replicate Organism Detection and Counting contact plates at Queen Mary recovered zygomycetes from the contaminated linen items. It took sponge swapping to find it; “without the use of sponge swab and selective culture medium, the causative agents in this outbreak would have been overlooked,” the investigators said.

Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors did not have any financial conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Clinicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis in immunosuppressed patients,

Major finding: Of 195 environmental samples at the contaminated laundry, 119 (61%) were positive for Zygomycetes, as well as 100% of air samples.

Data source: Epidemiological study in Hong Kong.

Disclosures: Hong Kong government services helped support the work. The authors do not have any financial conflicts of interest.

Denosumab boosts BMD in kidney transplant recipients

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients in the POSTOP trial.

Major finding: After 12 months, total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001).

Data source: POSTOP, a study of 90 patients who were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Pediatric heart transplant results not improving

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.

A multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for early mortality after transplant: age younger than 12 months (hazard ration [HR] 7.2) and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (HR 5). Late-phase mortality risk factors were age younger than 12 months (HR 3) and donor/recipient race mismatch (HR 2.2).

“Survival was not affected by era, underlying anomaly, prior Fontan, sensitization or pulmonary artery augmentation,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

Among the risk factors, longer bypass times may be a surrogate for a more complicated operation, the authors said. But where prior sternotomy is a risk factor following a heart transplant in adults, the study found no such risk in children. Another risk factor previous reports identified is pulmonary artery augmentation, but, again, this study found no risk in the pediatric group.

The researchers looked at days on the waiting list, with a median wait of 39 days in the study group. In all, 175 children were listed for transplants, but 51 did not go through for various reasons. Most of the children with CHD who had a heart transplant had previous surgery; only 13% had a primary heart transplant, mostly in the earlier phase of the study.

Dr. Alsoufi and coauthors also identified African American race as a risk factor for lower survival, which is consistent with other reports. But this study agreed with a previous report that donor/recipient race mismatch was a significant risk factor in white and African American patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:204-9). “While our finding might be anecdotal and specific to our geographic population, this warrants some investigation and might have some impact on future organ allocation algorithms and immunosuppression management,” the researchers wrote.

The authors had no relevant disclosures. Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta provided study funding.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.

A multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for early mortality after transplant: age younger than 12 months (hazard ration [HR] 7.2) and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (HR 5). Late-phase mortality risk factors were age younger than 12 months (HR 3) and donor/recipient race mismatch (HR 2.2).

“Survival was not affected by era, underlying anomaly, prior Fontan, sensitization or pulmonary artery augmentation,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

Among the risk factors, longer bypass times may be a surrogate for a more complicated operation, the authors said. But where prior sternotomy is a risk factor following a heart transplant in adults, the study found no such risk in children. Another risk factor previous reports identified is pulmonary artery augmentation, but, again, this study found no risk in the pediatric group.

The researchers looked at days on the waiting list, with a median wait of 39 days in the study group. In all, 175 children were listed for transplants, but 51 did not go through for various reasons. Most of the children with CHD who had a heart transplant had previous surgery; only 13% had a primary heart transplant, mostly in the earlier phase of the study.

Dr. Alsoufi and coauthors also identified African American race as a risk factor for lower survival, which is consistent with other reports. But this study agreed with a previous report that donor/recipient race mismatch was a significant risk factor in white and African American patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:204-9). “While our finding might be anecdotal and specific to our geographic population, this warrants some investigation and might have some impact on future organ allocation algorithms and immunosuppression management,” the researchers wrote.

The authors had no relevant disclosures. Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta provided study funding.

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.

A multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for early mortality after transplant: age younger than 12 months (hazard ration [HR] 7.2) and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (HR 5). Late-phase mortality risk factors were age younger than 12 months (HR 3) and donor/recipient race mismatch (HR 2.2).

“Survival was not affected by era, underlying anomaly, prior Fontan, sensitization or pulmonary artery augmentation,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

Among the risk factors, longer bypass times may be a surrogate for a more complicated operation, the authors said. But where prior sternotomy is a risk factor following a heart transplant in adults, the study found no such risk in children. Another risk factor previous reports identified is pulmonary artery augmentation, but, again, this study found no risk in the pediatric group.

The researchers looked at days on the waiting list, with a median wait of 39 days in the study group. In all, 175 children were listed for transplants, but 51 did not go through for various reasons. Most of the children with CHD who had a heart transplant had previous surgery; only 13% had a primary heart transplant, mostly in the earlier phase of the study.

Dr. Alsoufi and coauthors also identified African American race as a risk factor for lower survival, which is consistent with other reports. But this study agreed with a previous report that donor/recipient race mismatch was a significant risk factor in white and African American patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:204-9). “While our finding might be anecdotal and specific to our geographic population, this warrants some investigation and might have some impact on future organ allocation algorithms and immunosuppression management,” the researchers wrote.

The authors had no relevant disclosures. Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta provided study funding.

Key clinical point: Pediatric heart transplantation outcomes for congenital heart disease haven’t improved in the current era, indicating ongoing challenges.

Major finding: Ten years following heart transplantation, 13% of patients had undergone retransplantation, 43% had died without retransplantation, and 44% were alive without retransplantation.

Data source: A review of 124 children with congenital heart disease who had heart transplantation at a single center.

Disclosures: The study authors had no relationships to disclose.

Artificial pancreas improved glycemia after islet cell transplant

A closed-loop insulin pump with continuous glucose monitor produced significantly better blood glucose control in patients who have received islet cell transplants after pancreatectomy, compared with regular insulin injections, a pilot study has found.

Fourteen adults who received auto-islet transplants after pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis were randomized either to receive a closed-loop insulin pump system or the usual treatment of multiple insulin injections for 72 hours after transition from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin following surgery.

Researchers observed a significantly lower mean serum glucose in the insulin pump group, compared with the control group, with the highest average serum glucose level in individual patients in the pump group still being lower than the lowest average in the control group.

These improvements in glycemia were not associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemia in the closed-loop pump group and patients in the closed-loop pump group also required a significantly lower total daily insulin dose than did the control group, according to a paper published Nov. 20 in the American Journal of Transplantation.

“Success of islet engraftment is heavily dependent on maintenance of narrow-range euglycemia in the post-transplant period,” wrote Dr. Gregory P. Forlenza of the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his coauthors (Am J Transplant. 2015 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13539).

“This technology was shown in this study to provide some statistically and clinically significant improvements in glycemic parameters in adults after TP [total pancreatectomy] with IAT [intraportal islet autotransplantation] without producing associated increased episodes of hypoglycemia or adverse events.”

The study was funded by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of an investigator-initiated grant. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A closed-loop insulin pump with continuous glucose monitor produced significantly better blood glucose control in patients who have received islet cell transplants after pancreatectomy, compared with regular insulin injections, a pilot study has found.

Fourteen adults who received auto-islet transplants after pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis were randomized either to receive a closed-loop insulin pump system or the usual treatment of multiple insulin injections for 72 hours after transition from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin following surgery.

Researchers observed a significantly lower mean serum glucose in the insulin pump group, compared with the control group, with the highest average serum glucose level in individual patients in the pump group still being lower than the lowest average in the control group.

These improvements in glycemia were not associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemia in the closed-loop pump group and patients in the closed-loop pump group also required a significantly lower total daily insulin dose than did the control group, according to a paper published Nov. 20 in the American Journal of Transplantation.

“Success of islet engraftment is heavily dependent on maintenance of narrow-range euglycemia in the post-transplant period,” wrote Dr. Gregory P. Forlenza of the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his coauthors (Am J Transplant. 2015 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13539).

“This technology was shown in this study to provide some statistically and clinically significant improvements in glycemic parameters in adults after TP [total pancreatectomy] with IAT [intraportal islet autotransplantation] without producing associated increased episodes of hypoglycemia or adverse events.”

The study was funded by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of an investigator-initiated grant. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A closed-loop insulin pump with continuous glucose monitor produced significantly better blood glucose control in patients who have received islet cell transplants after pancreatectomy, compared with regular insulin injections, a pilot study has found.

Fourteen adults who received auto-islet transplants after pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis were randomized either to receive a closed-loop insulin pump system or the usual treatment of multiple insulin injections for 72 hours after transition from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin following surgery.

Researchers observed a significantly lower mean serum glucose in the insulin pump group, compared with the control group, with the highest average serum glucose level in individual patients in the pump group still being lower than the lowest average in the control group.

These improvements in glycemia were not associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemia in the closed-loop pump group and patients in the closed-loop pump group also required a significantly lower total daily insulin dose than did the control group, according to a paper published Nov. 20 in the American Journal of Transplantation.

“Success of islet engraftment is heavily dependent on maintenance of narrow-range euglycemia in the post-transplant period,” wrote Dr. Gregory P. Forlenza of the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his coauthors (Am J Transplant. 2015 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13539).

“This technology was shown in this study to provide some statistically and clinically significant improvements in glycemic parameters in adults after TP [total pancreatectomy] with IAT [intraportal islet autotransplantation] without producing associated increased episodes of hypoglycemia or adverse events.”

The study was funded by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of an investigator-initiated grant. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF TRANSPLANTATION

Key clinical point: A closed-loop insulin pump with a continuous glucose monitor offers significantly better blood glucose control in patients who have received islet cell transplants after pancreatectomy.

Major finding: Closed-loop insulin pumps were associated with a significantly lower mean serum glucose, compared with multiple daily insulin injections.

Data source: Randomized, controlled pilot study in 14 patients receiving auto-islet transplants after pancreatectomy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of an investigator-initiated grant. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Transplant waiting-list registrations dropped after direct acting–antiviral approval

SAN FRANCISCO – The number of new waiting-list registrations for liver transplantation among patients with hepatitis C virus declined significantly after the introduction of second-generation direct-acting antiviral agents, according to a review of United Network for Organ Sharing data.

New waiting-list registrations (NWRs) through March 31, 2015 – based on the most recent data available as of September 2015 – ranged from 740 to 976 per month between August 2012 and March 2015, and a review of the data show that HCV-specific NWRs declined by 23% overall in the 15 months after the Food and Drug Administration approved simeprevir (Nov. 22, 2013) and sofosbuvir (Dec. 6, 2013) vs. the 15 months prior (from 34.8% to 26.8%), Dr. Ryan B. Perumpail reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Further, the proportion of HCV patients without hepatocellular carcinoma among new waiting-list registrations declined by 33% (from 23.0% to 15.4%) and there was a significant decline in NWRs for liver transplants in nonhepatocellular-carcinoma HCV patients from January 2014 to March 2015 (153 per month) vs. August 2012 to October 2013 (mean 188 per month), for a mean difference of 35.0, said Dr. Perumpail of Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, Calif.

Among the HCV-related NWRs for liver transplantation, the proportion without hepatocellular carcinoma declined 12.5% (from 66.3% to 58.0%).

Direct-acting antiviral therapy has been prioritized in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis in an effort to slow clinical disease progress and to induce regression of hepatic histologic damage, Dr. Perumpail explained.

Thought limited by the retrospective design of the study, the findings suggest that the use of direct-acting antivirals contributed to a downward trend in NWRs for liver transplantation among HCV patients without hepatocellular carcinoma.

Dr. Perumpail reported having no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – The number of new waiting-list registrations for liver transplantation among patients with hepatitis C virus declined significantly after the introduction of second-generation direct-acting antiviral agents, according to a review of United Network for Organ Sharing data.

New waiting-list registrations (NWRs) through March 31, 2015 – based on the most recent data available as of September 2015 – ranged from 740 to 976 per month between August 2012 and March 2015, and a review of the data show that HCV-specific NWRs declined by 23% overall in the 15 months after the Food and Drug Administration approved simeprevir (Nov. 22, 2013) and sofosbuvir (Dec. 6, 2013) vs. the 15 months prior (from 34.8% to 26.8%), Dr. Ryan B. Perumpail reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Further, the proportion of HCV patients without hepatocellular carcinoma among new waiting-list registrations declined by 33% (from 23.0% to 15.4%) and there was a significant decline in NWRs for liver transplants in nonhepatocellular-carcinoma HCV patients from January 2014 to March 2015 (153 per month) vs. August 2012 to October 2013 (mean 188 per month), for a mean difference of 35.0, said Dr. Perumpail of Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, Calif.

Among the HCV-related NWRs for liver transplantation, the proportion without hepatocellular carcinoma declined 12.5% (from 66.3% to 58.0%).

Direct-acting antiviral therapy has been prioritized in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis in an effort to slow clinical disease progress and to induce regression of hepatic histologic damage, Dr. Perumpail explained.

Thought limited by the retrospective design of the study, the findings suggest that the use of direct-acting antivirals contributed to a downward trend in NWRs for liver transplantation among HCV patients without hepatocellular carcinoma.

Dr. Perumpail reported having no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – The number of new waiting-list registrations for liver transplantation among patients with hepatitis C virus declined significantly after the introduction of second-generation direct-acting antiviral agents, according to a review of United Network for Organ Sharing data.

New waiting-list registrations (NWRs) through March 31, 2015 – based on the most recent data available as of September 2015 – ranged from 740 to 976 per month between August 2012 and March 2015, and a review of the data show that HCV-specific NWRs declined by 23% overall in the 15 months after the Food and Drug Administration approved simeprevir (Nov. 22, 2013) and sofosbuvir (Dec. 6, 2013) vs. the 15 months prior (from 34.8% to 26.8%), Dr. Ryan B. Perumpail reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Further, the proportion of HCV patients without hepatocellular carcinoma among new waiting-list registrations declined by 33% (from 23.0% to 15.4%) and there was a significant decline in NWRs for liver transplants in nonhepatocellular-carcinoma HCV patients from January 2014 to March 2015 (153 per month) vs. August 2012 to October 2013 (mean 188 per month), for a mean difference of 35.0, said Dr. Perumpail of Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, Calif.

Among the HCV-related NWRs for liver transplantation, the proportion without hepatocellular carcinoma declined 12.5% (from 66.3% to 58.0%).

Direct-acting antiviral therapy has been prioritized in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis in an effort to slow clinical disease progress and to induce regression of hepatic histologic damage, Dr. Perumpail explained.

Thought limited by the retrospective design of the study, the findings suggest that the use of direct-acting antivirals contributed to a downward trend in NWRs for liver transplantation among HCV patients without hepatocellular carcinoma.

Dr. Perumpail reported having no disclosures.

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2015

Key clinical point: New waiting-list registrations for liver transplantation in patients with hepatitis C virus declined significantly after introduction of second-generation direct-acting antiviral agents.

Major finding: HCV-specific waiting-list registrations declined by 23% in the 15 months after vs. before FDA approval of simeprevir and sofosbuvir (34.8% vs. 26.8%).

Data source: A review of United Network for Organ Sharing data.

Disclosures: Dr. Perumpail reported having no disclosures.

VIDEO: Survival benefits, relapse risks in liver transplant for alcoholic hepatitis

SAN FRANCISCO – Are policies requiring 6 months of abstinence before liver transplantation in severe alcoholic hepatitis justified, given the potential survival advantage that earlier transplantation offers?

Alcoholic hepatitis has an “exceptionally high mortality rate,” noted Dr. Brian Lee of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. But a policy requiring 6 months of abstinence before liver transplantation in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis “is possibly even causing a precondition that’s death for these patients.”

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Dr. Lee discussed a study in which early liver transplantation in 40 patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis achieved a 100% survival rate at 1 year, with a 22% alcohol relapse rate.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Are policies requiring 6 months of abstinence before liver transplantation in severe alcoholic hepatitis justified, given the potential survival advantage that earlier transplantation offers?

Alcoholic hepatitis has an “exceptionally high mortality rate,” noted Dr. Brian Lee of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. But a policy requiring 6 months of abstinence before liver transplantation in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis “is possibly even causing a precondition that’s death for these patients.”

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Dr. Lee discussed a study in which early liver transplantation in 40 patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis achieved a 100% survival rate at 1 year, with a 22% alcohol relapse rate.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Are policies requiring 6 months of abstinence before liver transplantation in severe alcoholic hepatitis justified, given the potential survival advantage that earlier transplantation offers?

Alcoholic hepatitis has an “exceptionally high mortality rate,” noted Dr. Brian Lee of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. But a policy requiring 6 months of abstinence before liver transplantation in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis “is possibly even causing a precondition that’s death for these patients.”

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Dr. Lee discussed a study in which early liver transplantation in 40 patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis achieved a 100% survival rate at 1 year, with a 22% alcohol relapse rate.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2015

EADV: Prophylactic photodynamic therapy benefits transplant recipients

COPENHAGEN – Twice-yearly prophylactic photodynamic therapy for primary prevention of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas is a novel and effective strategy that addresses the problem of accelerated photocarcinogenesis in organ transplant recipients, according to an interim analysis of a multinational, randomized, controlled trial.

“The overall aim is to prevent squamous cell carcinoma development. Photodynamic therapy is well established for secondary prevention of further AKs, and these very early data show that it can also be used for primary prevention in very high-risk patients,” Dr. Katrine Togsverd-Bo said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Accelerated carcinogenesis on sun-exposed skin is a major concern in organ transplant recipients (OTRs). They experience early onset of multiple AKs, with field cancerization and up to a 100-fold increased risk of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Moreover, their SCCs are at substantially greater risk of metastasis than SCCs occurring in the general population, noted Dr. Togsverd-Bo of Bispebjerg Hospital and the University of Copenhagen.

She presented an interim analysis of an ongoing 5-year prospective randomized trial in 50 renal transplant recipients at academic dermatology centers in Copenhagen, Oslo, and Gothenburg, Sweden. All participants had clinically normal-appearing skin at baseline, with no history of AKs or SCCs. They are undergoing twice-yearly, split-side photodynamic therapy (PDT) on the face, forearm, and hand, with the opposite side serving as the untreated control.

To date, 25 patients have completed 3 years of the study. At 3 years of prospective follow-up by blinded evaluators, 50% of patients had AKs on their untreated side, compared with 26% on the prophylactic PDT side. The collective number of AKs on untreated skin was 43, compared with just 8 AKs on PDT-treated skin. Seven patients had AKs only on their untreated side, six had AKs on both sides, and none had any AKs only on their PDT-treated side.

The twice-yearly prophylactic PDT regimen consists of a 3-hour application of 20% methyl aminolevulinate as a photosensitizer followed by applications of a conventional LED light at 37 J/cm2.

Dr. Togsverd-Bo reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

COPENHAGEN – Twice-yearly prophylactic photodynamic therapy for primary prevention of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas is a novel and effective strategy that addresses the problem of accelerated photocarcinogenesis in organ transplant recipients, according to an interim analysis of a multinational, randomized, controlled trial.

“The overall aim is to prevent squamous cell carcinoma development. Photodynamic therapy is well established for secondary prevention of further AKs, and these very early data show that it can also be used for primary prevention in very high-risk patients,” Dr. Katrine Togsverd-Bo said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Accelerated carcinogenesis on sun-exposed skin is a major concern in organ transplant recipients (OTRs). They experience early onset of multiple AKs, with field cancerization and up to a 100-fold increased risk of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Moreover, their SCCs are at substantially greater risk of metastasis than SCCs occurring in the general population, noted Dr. Togsverd-Bo of Bispebjerg Hospital and the University of Copenhagen.

She presented an interim analysis of an ongoing 5-year prospective randomized trial in 50 renal transplant recipients at academic dermatology centers in Copenhagen, Oslo, and Gothenburg, Sweden. All participants had clinically normal-appearing skin at baseline, with no history of AKs or SCCs. They are undergoing twice-yearly, split-side photodynamic therapy (PDT) on the face, forearm, and hand, with the opposite side serving as the untreated control.

To date, 25 patients have completed 3 years of the study. At 3 years of prospective follow-up by blinded evaluators, 50% of patients had AKs on their untreated side, compared with 26% on the prophylactic PDT side. The collective number of AKs on untreated skin was 43, compared with just 8 AKs on PDT-treated skin. Seven patients had AKs only on their untreated side, six had AKs on both sides, and none had any AKs only on their PDT-treated side.

The twice-yearly prophylactic PDT regimen consists of a 3-hour application of 20% methyl aminolevulinate as a photosensitizer followed by applications of a conventional LED light at 37 J/cm2.

Dr. Togsverd-Bo reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

COPENHAGEN – Twice-yearly prophylactic photodynamic therapy for primary prevention of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas is a novel and effective strategy that addresses the problem of accelerated photocarcinogenesis in organ transplant recipients, according to an interim analysis of a multinational, randomized, controlled trial.

“The overall aim is to prevent squamous cell carcinoma development. Photodynamic therapy is well established for secondary prevention of further AKs, and these very early data show that it can also be used for primary prevention in very high-risk patients,” Dr. Katrine Togsverd-Bo said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Accelerated carcinogenesis on sun-exposed skin is a major concern in organ transplant recipients (OTRs). They experience early onset of multiple AKs, with field cancerization and up to a 100-fold increased risk of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Moreover, their SCCs are at substantially greater risk of metastasis than SCCs occurring in the general population, noted Dr. Togsverd-Bo of Bispebjerg Hospital and the University of Copenhagen.

She presented an interim analysis of an ongoing 5-year prospective randomized trial in 50 renal transplant recipients at academic dermatology centers in Copenhagen, Oslo, and Gothenburg, Sweden. All participants had clinically normal-appearing skin at baseline, with no history of AKs or SCCs. They are undergoing twice-yearly, split-side photodynamic therapy (PDT) on the face, forearm, and hand, with the opposite side serving as the untreated control.

To date, 25 patients have completed 3 years of the study. At 3 years of prospective follow-up by blinded evaluators, 50% of patients had AKs on their untreated side, compared with 26% on the prophylactic PDT side. The collective number of AKs on untreated skin was 43, compared with just 8 AKs on PDT-treated skin. Seven patients had AKs only on their untreated side, six had AKs on both sides, and none had any AKs only on their PDT-treated side.

The twice-yearly prophylactic PDT regimen consists of a 3-hour application of 20% methyl aminolevulinate as a photosensitizer followed by applications of a conventional LED light at 37 J/cm2.

Dr. Togsverd-Bo reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Prophylactic photodynamic therapy is a new and effective strategy for primary prevention of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas in organ transplant recipients.

Major finding: At 3 years of follow-up, 25 renal transplant recipients collectively had 8 actinic keratoses on the side of their face, forearms, and hands treated with twice-yearly prophylactic photodynamic therapy, compared with 43 AKs on the untreated control side.

Data source: This is an interim 3-year analysis from an ongoing 5-year prospective multinational, randomized, controlled trial involving 50 renal transplant recipients.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this ongoing study.

Big declines seen in aspergillosis mortality

SAN DIEGO – In-hospital mortality in patients with aspergillosis plummeted nationally, according to data from 2001-2011, with the biggest improvement seen in immunocompromised patients traditionally considered at high mortality risk, Dr. Masako Mizusawa reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The decline in in-hospital mortality wasn’t linear. Rather, it followed a stepwise pattern, and those steps occurred in association with three major advances during the study years: Food and Drug Administration approval of voriconazole in 2002, the FDA’s 2003 approval of the galactomannan serologic assay allowing for speedier diagnosis of aspergillosis, and the 2008 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines on the treatment of aspergillosis (Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 1;46[3]:327-60).

“This was an observational study and we can’t actually say that these events are causative. But just looking at the time relationship, it certainly looks plausible,” Dr. Mizusawa said.

In addition, the median hospital length of stay decreased from 9 to 7 days in patients with this potentially life-threatening infection, noted Dr. Mizusawa of Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

She presented what she believes is the largest U.S. longitudinal study of hospital care for aspergillosis. The retrospective study used nationally representative data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Utilization and Cost Project–Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Dr. Mizusawa and coinvestigators defined aspergillosis patients as being at high mortality risk if they had established risk factors indicative of immunocompromise, including hematologic malignancy, neutropenia, recent stem cell or solid organ transplantation, HIV, or rheumatologic disease. Patients at lower mortality risk included those with asthma, COPD, diabetes, malnutrition, pulmonary tuberculosis, or non-TB mycobacterial infection.

The proportion of patients who were high risk climbed over the years, from 41% among the 892 patients with aspergillosis-related hospitalization in the 2001 sample to 50% among 1,420 patients in 2011. Yet in-hospital mortality in high-risk patients fell from 26.4% in 2001 to 9.1% in 2011. Meanwhile, the mortality rate in lower-risk patients improved from 14.6% to 6.6%. The overall in-hospital mortality rate went from 18.8% to 7.7%.

Of note, the proportion of aspergillosis patients with renal failure jumped from 9.8% in 2001 to 21.5% in 2011, even though the treatments for aspergillosis are relatively non-nephrotoxic, with the exception of amphotericin B. The outlook for these patients has improved greatly: In-hospital mortality for aspergillosis patients in renal failure went from 40.2% in 2001 to 16.1% in 2011.

While in-hospital mortality and length of stay were decreasing during the study years, total hospital charges for patients with aspergillosis were going up: from a median of $29,998 in 2001 to $44,888 in 2001 dollars a decade later. This cost-of-care increase was confined to patients at lower baseline risk or with no risk factors. Somewhat surprisingly, the high-risk group didn’t have a significant increase in hospital charges over the 10-year period.

“Maybe we’re just doing a better job of treating them, so they may not necessarily have to use a lot of resources,” Dr. Mizusawa offered as explanation.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this unfunded study.

SAN DIEGO – In-hospital mortality in patients with aspergillosis plummeted nationally, according to data from 2001-2011, with the biggest improvement seen in immunocompromised patients traditionally considered at high mortality risk, Dr. Masako Mizusawa reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The decline in in-hospital mortality wasn’t linear. Rather, it followed a stepwise pattern, and those steps occurred in association with three major advances during the study years: Food and Drug Administration approval of voriconazole in 2002, the FDA’s 2003 approval of the galactomannan serologic assay allowing for speedier diagnosis of aspergillosis, and the 2008 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines on the treatment of aspergillosis (Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 1;46[3]:327-60).

“This was an observational study and we can’t actually say that these events are causative. But just looking at the time relationship, it certainly looks plausible,” Dr. Mizusawa said.