User login

Growth hormone levels predict postsurgical acromegaly remission

Elevated growth hormone levels had a negative impact on remission in acromegaly patients undergoing transsphenoidal adenomectomies, researchers from Emory University in Atlanta concluded after a retrospective, multivariate analysis of case studies.

To determine the impact of preoperative growth hormone (GH), Dr. Jeremy Anthony and his associates examined the case files of 79 acromegaly patients who underwent transsphenoidal adenomectomy between 1994 and 2013 at Emory and assigned them to two groups on the basis of their preoperative GH levels, using 40 ng/mL as the cutoff.

Biochemical remission was defined as normal insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) during follow-up of more than 3 months in the absence of adjuvant therapy. The results were released at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists on May 15 in Las Vegas.

Group A, with preoperative GH levels greater than 40 ng/mL, comprised 19 patients with a mean age of 43 years and an average follow-up of 38 months. They had larger, more invasive tumors, higher preoperative IGF-1 levels, higher immediate postoperative GH, and more residual tumors at 3 months, compared with the 60 patients in group B, who had preop GH levels of 40 ng/mL or less, a mean age of 47 years, and 43 months of follow-up.

In group A, three patients (15%) had remission at 3 months, but two patients had recurrence within 2 years. In group B, 35 patients (58%) had remission at 3 months with no recurrence during follow-up.

On univariate analysis, lower preoperative GH was a predictor of remission. In a multivariate analysis, however, lack of cavernous sinus invasion was the only predictor of remission.

"The relationship of GH elevation and cavernous sinus invasion should be further defined, as should the molecular fingerprint and the potential role of preoperative medical treatment in this group of patients," Dr. Anthony and his associates wrote.

No disclosures were reported.

Elevated growth hormone levels had a negative impact on remission in acromegaly patients undergoing transsphenoidal adenomectomies, researchers from Emory University in Atlanta concluded after a retrospective, multivariate analysis of case studies.

To determine the impact of preoperative growth hormone (GH), Dr. Jeremy Anthony and his associates examined the case files of 79 acromegaly patients who underwent transsphenoidal adenomectomy between 1994 and 2013 at Emory and assigned them to two groups on the basis of their preoperative GH levels, using 40 ng/mL as the cutoff.

Biochemical remission was defined as normal insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) during follow-up of more than 3 months in the absence of adjuvant therapy. The results were released at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists on May 15 in Las Vegas.

Group A, with preoperative GH levels greater than 40 ng/mL, comprised 19 patients with a mean age of 43 years and an average follow-up of 38 months. They had larger, more invasive tumors, higher preoperative IGF-1 levels, higher immediate postoperative GH, and more residual tumors at 3 months, compared with the 60 patients in group B, who had preop GH levels of 40 ng/mL or less, a mean age of 47 years, and 43 months of follow-up.

In group A, three patients (15%) had remission at 3 months, but two patients had recurrence within 2 years. In group B, 35 patients (58%) had remission at 3 months with no recurrence during follow-up.

On univariate analysis, lower preoperative GH was a predictor of remission. In a multivariate analysis, however, lack of cavernous sinus invasion was the only predictor of remission.

"The relationship of GH elevation and cavernous sinus invasion should be further defined, as should the molecular fingerprint and the potential role of preoperative medical treatment in this group of patients," Dr. Anthony and his associates wrote.

No disclosures were reported.

Elevated growth hormone levels had a negative impact on remission in acromegaly patients undergoing transsphenoidal adenomectomies, researchers from Emory University in Atlanta concluded after a retrospective, multivariate analysis of case studies.

To determine the impact of preoperative growth hormone (GH), Dr. Jeremy Anthony and his associates examined the case files of 79 acromegaly patients who underwent transsphenoidal adenomectomy between 1994 and 2013 at Emory and assigned them to two groups on the basis of their preoperative GH levels, using 40 ng/mL as the cutoff.

Biochemical remission was defined as normal insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) during follow-up of more than 3 months in the absence of adjuvant therapy. The results were released at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists on May 15 in Las Vegas.

Group A, with preoperative GH levels greater than 40 ng/mL, comprised 19 patients with a mean age of 43 years and an average follow-up of 38 months. They had larger, more invasive tumors, higher preoperative IGF-1 levels, higher immediate postoperative GH, and more residual tumors at 3 months, compared with the 60 patients in group B, who had preop GH levels of 40 ng/mL or less, a mean age of 47 years, and 43 months of follow-up.

In group A, three patients (15%) had remission at 3 months, but two patients had recurrence within 2 years. In group B, 35 patients (58%) had remission at 3 months with no recurrence during follow-up.

On univariate analysis, lower preoperative GH was a predictor of remission. In a multivariate analysis, however, lack of cavernous sinus invasion was the only predictor of remission.

"The relationship of GH elevation and cavernous sinus invasion should be further defined, as should the molecular fingerprint and the potential role of preoperative medical treatment in this group of patients," Dr. Anthony and his associates wrote.

No disclosures were reported.

FROM AACE 2014

Major finding: Acromegaly patients with preoperative GH levels greater than 40 ng/mL had a 15% remission rate at 3 months, compared with 58% in those with lower preop GH levels.

Data source: A retrospective case series of 79 acromegaly patients who underwent transsphenoidal adenomectomy between 1994 and 2013.

Disclosures: No disclosures were reported.

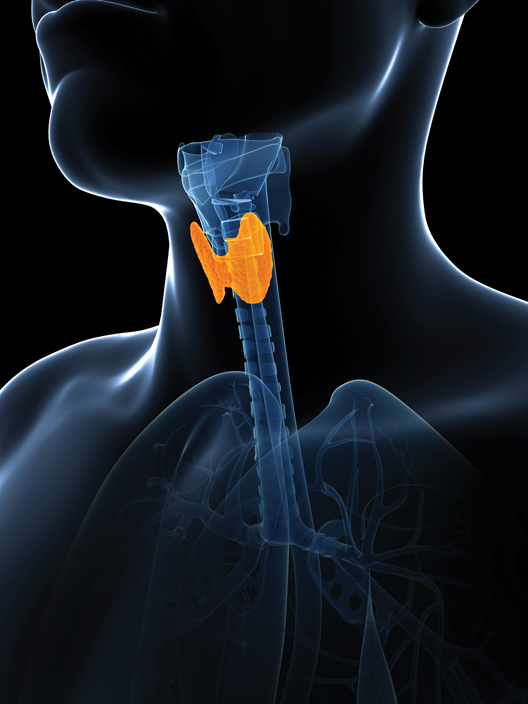

Think ‘celiac disease’ in patients requiring high-dose levothyroxine

CHICAGO – Hypothyroid patients who need either at least 125 mcg or 1.5 mcg/kg of levothyroxine per day in order to remain euthyroid should routinely be tested for celiac disease, Dr. Richard S. Zubarik asserted at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

In his cross-sectional study of 400 consecutive patients with hypothyroidism who underwent testing for celiac disease, 5% of those on a levothyroxine dose at or above that threshold were found to have biopsy-confirmed celiac disease.

Mass screening for celiac disease in the broad U.S. population isn’t recommended at present because the prevalence – 0.75% is deemed too low to justify such a practice. However, current national and international guidelines do recommend routine testing for case finding in selected populations known to be at increased risk of celiac disease. These include, for example, patients with asymptomatic iron-deficiency anemia, who have a celiac disease prevalence of 2.3%-5%. Thus, the 5% prevalence of celiac disease in hypothyroid patients requiring high-dose levothyroxine in order to maintain a euthyroid state is at least as high as, and perhaps higher than, the prevalence in groups having a guideline-recommended indication for testing, noted Dr. Zubarik, professor of medicine and director of GI endoscopy at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Testing involves a simple serologic test for tissue transglutaminase. An elevated level triggers endoscopy with duodenal biopsies. A positive biopsy confirms the diagnosis and warrants initiation of a gluten-free diet.

The 400 consecutive patients on treatment for hypothyroidism in Dr. Zubarik’s study averaged 59 years of age, and 82% were women. Thirty percent of participants required 125 mcg or more of levothyroxine, and 29% needed at least 1.5 mcg/kg daily in order to maintain euthyroid status. Dr. Zubarik and his coinvestigators selected those doses as their threshold in the cross-sectional study because their earlier retrospective study had suggested patients requiring that much levothyroxine might have an increased prevalence of concomitant celiac disease (Am. J. Med. 2012;125:278-82). The group requiring an elevated dose and those who were able to remain euthyroid on lower doses were similar in age, sex, weight, body mass index, and the prevalence of diabetes.

All subjects took a serologic tissue transglutaminase test, and those with an elevated level underwent endoscopy with biopsies.

Eight of the 400 patients had an elevated serum tissue transglutaminase level, and seven of the eight were subsequently confirmed as having biopsy-proven celiac disease. Six of the seven patients with celiac disease met or exceeded the levothyroxine dose threshold.

Gastrointestinal symptoms weren’t helpful in differentiating the hypothyroid patients with and without celiac disease. Scores on the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale weren’t significantly different between the two groups.

Malabsorption of vitamins, minerals, nutrients, and medications is not uncommon in patients with celiac disease, which accounts for the increased disease prevalence seen among patients with iron-deficiency anemia. Whether the increased prevalence of celiac disease among hypothyroid patients requiring elevated doses of levothyroxine is the result of levothyroxine malabsorption or perhaps a consequence of more severe hypothyroidism being present in patients with concomitant celiac disease is an unanswered question Dr. Zubarik plans to study.

The association between thyroid disease and celiac disease is independent of gluten exposure and most likely stems from a common genetic predisposition, the gastroenterologist said.

This study was carried out free of commercial support. Dr. Zubarik reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Hypothyroid patients who need either at least 125 mcg or 1.5 mcg/kg of levothyroxine per day in order to remain euthyroid should routinely be tested for celiac disease, Dr. Richard S. Zubarik asserted at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

In his cross-sectional study of 400 consecutive patients with hypothyroidism who underwent testing for celiac disease, 5% of those on a levothyroxine dose at or above that threshold were found to have biopsy-confirmed celiac disease.

Mass screening for celiac disease in the broad U.S. population isn’t recommended at present because the prevalence – 0.75% is deemed too low to justify such a practice. However, current national and international guidelines do recommend routine testing for case finding in selected populations known to be at increased risk of celiac disease. These include, for example, patients with asymptomatic iron-deficiency anemia, who have a celiac disease prevalence of 2.3%-5%. Thus, the 5% prevalence of celiac disease in hypothyroid patients requiring high-dose levothyroxine in order to maintain a euthyroid state is at least as high as, and perhaps higher than, the prevalence in groups having a guideline-recommended indication for testing, noted Dr. Zubarik, professor of medicine and director of GI endoscopy at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Testing involves a simple serologic test for tissue transglutaminase. An elevated level triggers endoscopy with duodenal biopsies. A positive biopsy confirms the diagnosis and warrants initiation of a gluten-free diet.

The 400 consecutive patients on treatment for hypothyroidism in Dr. Zubarik’s study averaged 59 years of age, and 82% were women. Thirty percent of participants required 125 mcg or more of levothyroxine, and 29% needed at least 1.5 mcg/kg daily in order to maintain euthyroid status. Dr. Zubarik and his coinvestigators selected those doses as their threshold in the cross-sectional study because their earlier retrospective study had suggested patients requiring that much levothyroxine might have an increased prevalence of concomitant celiac disease (Am. J. Med. 2012;125:278-82). The group requiring an elevated dose and those who were able to remain euthyroid on lower doses were similar in age, sex, weight, body mass index, and the prevalence of diabetes.

All subjects took a serologic tissue transglutaminase test, and those with an elevated level underwent endoscopy with biopsies.

Eight of the 400 patients had an elevated serum tissue transglutaminase level, and seven of the eight were subsequently confirmed as having biopsy-proven celiac disease. Six of the seven patients with celiac disease met or exceeded the levothyroxine dose threshold.

Gastrointestinal symptoms weren’t helpful in differentiating the hypothyroid patients with and without celiac disease. Scores on the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale weren’t significantly different between the two groups.

Malabsorption of vitamins, minerals, nutrients, and medications is not uncommon in patients with celiac disease, which accounts for the increased disease prevalence seen among patients with iron-deficiency anemia. Whether the increased prevalence of celiac disease among hypothyroid patients requiring elevated doses of levothyroxine is the result of levothyroxine malabsorption or perhaps a consequence of more severe hypothyroidism being present in patients with concomitant celiac disease is an unanswered question Dr. Zubarik plans to study.

The association between thyroid disease and celiac disease is independent of gluten exposure and most likely stems from a common genetic predisposition, the gastroenterologist said.

This study was carried out free of commercial support. Dr. Zubarik reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Hypothyroid patients who need either at least 125 mcg or 1.5 mcg/kg of levothyroxine per day in order to remain euthyroid should routinely be tested for celiac disease, Dr. Richard S. Zubarik asserted at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

In his cross-sectional study of 400 consecutive patients with hypothyroidism who underwent testing for celiac disease, 5% of those on a levothyroxine dose at or above that threshold were found to have biopsy-confirmed celiac disease.

Mass screening for celiac disease in the broad U.S. population isn’t recommended at present because the prevalence – 0.75% is deemed too low to justify such a practice. However, current national and international guidelines do recommend routine testing for case finding in selected populations known to be at increased risk of celiac disease. These include, for example, patients with asymptomatic iron-deficiency anemia, who have a celiac disease prevalence of 2.3%-5%. Thus, the 5% prevalence of celiac disease in hypothyroid patients requiring high-dose levothyroxine in order to maintain a euthyroid state is at least as high as, and perhaps higher than, the prevalence in groups having a guideline-recommended indication for testing, noted Dr. Zubarik, professor of medicine and director of GI endoscopy at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Testing involves a simple serologic test for tissue transglutaminase. An elevated level triggers endoscopy with duodenal biopsies. A positive biopsy confirms the diagnosis and warrants initiation of a gluten-free diet.

The 400 consecutive patients on treatment for hypothyroidism in Dr. Zubarik’s study averaged 59 years of age, and 82% were women. Thirty percent of participants required 125 mcg or more of levothyroxine, and 29% needed at least 1.5 mcg/kg daily in order to maintain euthyroid status. Dr. Zubarik and his coinvestigators selected those doses as their threshold in the cross-sectional study because their earlier retrospective study had suggested patients requiring that much levothyroxine might have an increased prevalence of concomitant celiac disease (Am. J. Med. 2012;125:278-82). The group requiring an elevated dose and those who were able to remain euthyroid on lower doses were similar in age, sex, weight, body mass index, and the prevalence of diabetes.

All subjects took a serologic tissue transglutaminase test, and those with an elevated level underwent endoscopy with biopsies.

Eight of the 400 patients had an elevated serum tissue transglutaminase level, and seven of the eight were subsequently confirmed as having biopsy-proven celiac disease. Six of the seven patients with celiac disease met or exceeded the levothyroxine dose threshold.

Gastrointestinal symptoms weren’t helpful in differentiating the hypothyroid patients with and without celiac disease. Scores on the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale weren’t significantly different between the two groups.

Malabsorption of vitamins, minerals, nutrients, and medications is not uncommon in patients with celiac disease, which accounts for the increased disease prevalence seen among patients with iron-deficiency anemia. Whether the increased prevalence of celiac disease among hypothyroid patients requiring elevated doses of levothyroxine is the result of levothyroxine malabsorption or perhaps a consequence of more severe hypothyroidism being present in patients with concomitant celiac disease is an unanswered question Dr. Zubarik plans to study.

The association between thyroid disease and celiac disease is independent of gluten exposure and most likely stems from a common genetic predisposition, the gastroenterologist said.

This study was carried out free of commercial support. Dr. Zubarik reported having no financial conflicts.

AT DDW 2014

Major finding: Five percent of hypothyroid patients who needed 125 mcg or more of levothyroxine daily in order to remain euthyroid proved to have previously undiagnosed celiac disease, a prevalence deemed high enough to warrant routine testing for the GI disease in that population.

Data source: This was a cross-sectional study involving 400 consecutive patients being treated for hypothyroidism, all of whom underwent serologic testing for celiac disease via the serum tissue transglutaminase test.

Disclosures: This study was carried out free of commercial support. Dr. Zubarik reported having no financial conflicts.

VIDEO: When to screen for celiac disease in hypothyroidism

CHICAGO – Patients with hypothyroidism who needed higher doses of levothyroxine were more likely to have celiac disease, according to a study released at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

In a study of 400 patients with hypothyroidism, about 5% of those who needed at least 125 mcg/day of levothyroxine also had celiac disease, according to Dr. Richard Zubarik of the University of Vermont, Burlington.That prevalence rate tops even the rate among patients with iron deficiency anemia, for whom celiac disease screening is recommended.

In a video interview, Dr. Zubarik explains which patients with hypothyroidism should be screened for celiac disease, and he discusses what mechanisms might link the need for higher levels of levothyroxine with an increased risk of celiac disease.

CHICAGO – Patients with hypothyroidism who needed higher doses of levothyroxine were more likely to have celiac disease, according to a study released at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

In a study of 400 patients with hypothyroidism, about 5% of those who needed at least 125 mcg/day of levothyroxine also had celiac disease, according to Dr. Richard Zubarik of the University of Vermont, Burlington.That prevalence rate tops even the rate among patients with iron deficiency anemia, for whom celiac disease screening is recommended.

In a video interview, Dr. Zubarik explains which patients with hypothyroidism should be screened for celiac disease, and he discusses what mechanisms might link the need for higher levels of levothyroxine with an increased risk of celiac disease.

CHICAGO – Patients with hypothyroidism who needed higher doses of levothyroxine were more likely to have celiac disease, according to a study released at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

In a study of 400 patients with hypothyroidism, about 5% of those who needed at least 125 mcg/day of levothyroxine also had celiac disease, according to Dr. Richard Zubarik of the University of Vermont, Burlington.That prevalence rate tops even the rate among patients with iron deficiency anemia, for whom celiac disease screening is recommended.

In a video interview, Dr. Zubarik explains which patients with hypothyroidism should be screened for celiac disease, and he discusses what mechanisms might link the need for higher levels of levothyroxine with an increased risk of celiac disease.

At DDW 2014

Thyroglobulin washout boosts diagnostic sensitivity in recurrent thyroid cancer

PHOENIX – In patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancer, fine-needle aspiration cytology and thyroglobulin washout was a highly sensitive and specific means of detecting metastatic disease, according to a retrospective analysis.

Surgeon-performed FNA-Tg washout appears to increase the diagnostic accuracy in detecting metastatic disease in this patient population. Routine performance of the combined modalities should be considered in patients with suspicious metastatic lymphadenopathies, said Dr. Hossam Mohamed of the division of endocrine and oncological surgery in the department of surgery at Tulane University, New Orleans.

In a retrospective study of 117 patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancer, the combination of surgeon-performed fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) with fine-needle aspiration thyroglobulin washout (FNA-Tg) had a 100% specificity, 94.9% sensitivity, and negative predictive value of 93.75%, with a diagnostic accuracy of 97.1%, he said.

"Cervical lymph node involvement has been reported to be up to 46% at initial diagnosis, hence ultrasonography and fine-needle aspiration have been standard diagnostic modalities used to detect and evaluate cervical lymph nodes in patients with thyroid malignancies," he said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

His team hypothesized that by adding surgeon-performed ultrasonography with Tg washout to FNAC for the management of patients with suspicious lymphadenopathies, they might be able to increase the accuracy of the combined tests for detecting metastatic disease in patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancers.

In a retrospective study, they looked at results for patients who underwent preoperative FNAC and FNA-Tg washout followed by selective neck dissection. All dissections were performed by senior author Dr. Emad Kandil, chief of the endocrine surgery section at Tulane University.

They correlated the test results with the final pathology results of the dissected lymph nodes, and compared the sensitivity and specificity of the combined modalities to those of standard FNAC alone.

Of the 117 patients, 76% were female, and mean age was 52 years. Nearly half of the patients (47.6%) had cervical lymph node dissections, 39.7% had modified radical lymph node dissections, 6.35% had combined modified-radical, and 12.7% had combined modified-radical and cervical resections. Half of the group required second resections.

When the researchers compared the individual modalities to the final pathology results, they found that the respective sensitivity of FNAC, FNA-Tg, and the two combined were 84.6%, 89.4%, and 94.9%. They found the respective specificities to be 100%, 96.8%, and 100%.

The negative predictive value of FNAC was 87.1%. and of FNA-Tg was 85.7%. When the two diagnostic methods were used together, they ruled out metastases with 93.75% accuracy.

"Only one patient had a negative lymph node pathology with a positive FNA-Tg washout, which we couldn’t find an explanation for," Dr. Mohamed said.

Two patients who had negative FNA-Tg washout levels had evidence of atypical cells on FNAC and elevated serum Tg levels. These patients were therefore taken to surgery, and were found to have metastatic disease on final pathology, he said.

The study was internally funded. Dr. Mohamed reported having no financial disclosures.

PHOENIX – In patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancer, fine-needle aspiration cytology and thyroglobulin washout was a highly sensitive and specific means of detecting metastatic disease, according to a retrospective analysis.

Surgeon-performed FNA-Tg washout appears to increase the diagnostic accuracy in detecting metastatic disease in this patient population. Routine performance of the combined modalities should be considered in patients with suspicious metastatic lymphadenopathies, said Dr. Hossam Mohamed of the division of endocrine and oncological surgery in the department of surgery at Tulane University, New Orleans.

In a retrospective study of 117 patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancer, the combination of surgeon-performed fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) with fine-needle aspiration thyroglobulin washout (FNA-Tg) had a 100% specificity, 94.9% sensitivity, and negative predictive value of 93.75%, with a diagnostic accuracy of 97.1%, he said.

"Cervical lymph node involvement has been reported to be up to 46% at initial diagnosis, hence ultrasonography and fine-needle aspiration have been standard diagnostic modalities used to detect and evaluate cervical lymph nodes in patients with thyroid malignancies," he said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

His team hypothesized that by adding surgeon-performed ultrasonography with Tg washout to FNAC for the management of patients with suspicious lymphadenopathies, they might be able to increase the accuracy of the combined tests for detecting metastatic disease in patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancers.

In a retrospective study, they looked at results for patients who underwent preoperative FNAC and FNA-Tg washout followed by selective neck dissection. All dissections were performed by senior author Dr. Emad Kandil, chief of the endocrine surgery section at Tulane University.

They correlated the test results with the final pathology results of the dissected lymph nodes, and compared the sensitivity and specificity of the combined modalities to those of standard FNAC alone.

Of the 117 patients, 76% were female, and mean age was 52 years. Nearly half of the patients (47.6%) had cervical lymph node dissections, 39.7% had modified radical lymph node dissections, 6.35% had combined modified-radical, and 12.7% had combined modified-radical and cervical resections. Half of the group required second resections.

When the researchers compared the individual modalities to the final pathology results, they found that the respective sensitivity of FNAC, FNA-Tg, and the two combined were 84.6%, 89.4%, and 94.9%. They found the respective specificities to be 100%, 96.8%, and 100%.

The negative predictive value of FNAC was 87.1%. and of FNA-Tg was 85.7%. When the two diagnostic methods were used together, they ruled out metastases with 93.75% accuracy.

"Only one patient had a negative lymph node pathology with a positive FNA-Tg washout, which we couldn’t find an explanation for," Dr. Mohamed said.

Two patients who had negative FNA-Tg washout levels had evidence of atypical cells on FNAC and elevated serum Tg levels. These patients were therefore taken to surgery, and were found to have metastatic disease on final pathology, he said.

The study was internally funded. Dr. Mohamed reported having no financial disclosures.

PHOENIX – In patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancer, fine-needle aspiration cytology and thyroglobulin washout was a highly sensitive and specific means of detecting metastatic disease, according to a retrospective analysis.

Surgeon-performed FNA-Tg washout appears to increase the diagnostic accuracy in detecting metastatic disease in this patient population. Routine performance of the combined modalities should be considered in patients with suspicious metastatic lymphadenopathies, said Dr. Hossam Mohamed of the division of endocrine and oncological surgery in the department of surgery at Tulane University, New Orleans.

In a retrospective study of 117 patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancer, the combination of surgeon-performed fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) with fine-needle aspiration thyroglobulin washout (FNA-Tg) had a 100% specificity, 94.9% sensitivity, and negative predictive value of 93.75%, with a diagnostic accuracy of 97.1%, he said.

"Cervical lymph node involvement has been reported to be up to 46% at initial diagnosis, hence ultrasonography and fine-needle aspiration have been standard diagnostic modalities used to detect and evaluate cervical lymph nodes in patients with thyroid malignancies," he said at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

His team hypothesized that by adding surgeon-performed ultrasonography with Tg washout to FNAC for the management of patients with suspicious lymphadenopathies, they might be able to increase the accuracy of the combined tests for detecting metastatic disease in patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancers.

In a retrospective study, they looked at results for patients who underwent preoperative FNAC and FNA-Tg washout followed by selective neck dissection. All dissections were performed by senior author Dr. Emad Kandil, chief of the endocrine surgery section at Tulane University.

They correlated the test results with the final pathology results of the dissected lymph nodes, and compared the sensitivity and specificity of the combined modalities to those of standard FNAC alone.

Of the 117 patients, 76% were female, and mean age was 52 years. Nearly half of the patients (47.6%) had cervical lymph node dissections, 39.7% had modified radical lymph node dissections, 6.35% had combined modified-radical, and 12.7% had combined modified-radical and cervical resections. Half of the group required second resections.

When the researchers compared the individual modalities to the final pathology results, they found that the respective sensitivity of FNAC, FNA-Tg, and the two combined were 84.6%, 89.4%, and 94.9%. They found the respective specificities to be 100%, 96.8%, and 100%.

The negative predictive value of FNAC was 87.1%. and of FNA-Tg was 85.7%. When the two diagnostic methods were used together, they ruled out metastases with 93.75% accuracy.

"Only one patient had a negative lymph node pathology with a positive FNA-Tg washout, which we couldn’t find an explanation for," Dr. Mohamed said.

Two patients who had negative FNA-Tg washout levels had evidence of atypical cells on FNAC and elevated serum Tg levels. These patients were therefore taken to surgery, and were found to have metastatic disease on final pathology, he said.

The study was internally funded. Dr. Mohamed reported having no financial disclosures.

AT SSO 2014

Key clinical point: Adding surgeon-performed ultrasonography with thyroglobulin washout to fine-needle aspiration cytology increases the accuracy of detecting metastatic disease in patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancers.

Major finding: The negative predictive value of fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) with fine-needle aspiration thyroglobulin washout (FNA-Tg) was 93.75%.

Data source: Review of prospectively collected data on 117 patients with recurrent papillary thyroid cancer.

Disclosures: The study was internally funded. Dr. Mohamed reported having no financial disclosures.

High-volume surgeons have best adrenalectomy outcomes

PHOENIX – There is more evidence that it’s best to go with the pros: Adrenalectomies performed by higher-volume surgeons are associated with fewer complications, lower costs, and shorter lengths of stay than are those done by surgeons who dabble in the procedure.

The findings, presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, come from a cross-sectional study of outcomes on all patients who underwent unilateral, partial, or bilateral adrenalectomies in the United States over a 7-year span.

"The frequency of adrenalectomy has steadily increased in the United States within the last few years, and with improvement of diagnostic and imaging modalities it’s likely that the rate of adrenal surgery will continue to rise," said Dr. Adam Hauch, a research resident in the department of surgery at Tulane University, New Orleans.

The prospects for the growth in the procedure prompted Dr. Hauch and colleagues to look at clinical and economic outcomes following adrenalectomy, and to see how surgeon volume, diagnosis, and type of surgery might affect outcomes.

They drew on discharge data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project – National Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS), an administrative database sponsored by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The information included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes identifying all adult patients who underwent adrenalectomies in U.S. hospitals from 2003 through 2009. Patients were divided into benign and malignant lesion groups.

The investigators found 7,829 procedures. Mean patient age was 50 years, most of the patients (74.4%) were white, and the majority were female (58.2%) and were privately insured (58.9%). Nearly all of the patients (98.3%) had one or no comorbidities at the time of admission. Only 42 patients (0.5%) died during their hospital stays.

More than three-fourths of the procedures (79.2%) were for benign disease; the remaining 20.8% of surgeries were for malignancies.

Low-volume surgeons, defined as those who performed one or fewer adrenalectomies on average per year, performed 41.7% of all procedures, compared with 34.7% for intermediate-volume surgeons (two to five per year) and 23.6% for high-volume surgeons (more than five per year).

The vast majority (97.1%) of procedures were unilateral/partial, and approximately 95% of surgeons in each experience category performed such procedures. Procedures for malignant disease accounted for 10.6% of cases for low-volume surgeons, 6.3% for intermediate-volume docs, and 4.3% of the most prolific surgeons.

It’s complicated

Risks for any complication were significantly higher among low-volume surgeons (18.8% of their cases), compared with 14.6% for those in the middle, and 11.6% for the high-volume operators (P less than .0001). High-volume performers had significantly lower risk for cardiovascular complications (P = .0008), pulmonary complications (P = .0481), bleeding (P = .0106), and technical difficulties during surgery (P = .0024).

In an analysis adjusted for patient demographic factors, payer, primary diagnosis, obesity, comorbidities, inpatient death, admission type, hospital teaching status and volume, surgeon, and type of procedure, low-volume surgeons were nearly twice as likely as were high-volume surgeons to have complications (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.822, P less than .0001), and intermediate-volume surgeons had a nearly 1.5-fold higher risk (aOR 1.479, P = .0044).

Other risk factors for complications were bilateral vs. unilateral procedures (aOR 2.165, P = .0018), and malignant vs. benign disease (aOR 1.685, P less than .0001).

Not surprisingly, complications more than doubled mean total case charges, which ranged from $33,659 for uncomplicated unilateral cases to $73,021 for complicated cases (P = .0013), and from $47,284 for bilateral cases with no complications, to $141,461 for two-sided procedures with complications (P = .0221). Charges were higher for malignant cases than for benign cases without complications (P less than .0001), but complications brought the charges for both benign and malignant cases closer together .

Charges for noncomplicated procedures performed by high-volume surgeons were a comparative bargain at $27,324, compared with $33,499 for low- and intermediate-volume surgeons combined (P = .001). However, there were no significant differences by surgeon volume when complications arose.

Similarly, lengths of stay were prolonged when complications ensued for both unilateral cases (mean 3.7 days vs. 9.3 for complicated cases, P = .0042) and for bilateral cases (9.3 vs. 19.8, P = .025).

Higher volume surgeons managed to get patients out faster, averaging 2.7 days for cases without complications, compared with 4.2 for low/intermediate-volume surgeons (P less than .0001). When complications arose, patients of higher-volume surgeons still had shorter lengths of stay (8.5 vs. 10.4 days), but this difference was not statistically significant.

Dr. Lawrence Kim, professor of surgery at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said after the presentation that the study showed the limitations of using administrative data.

He said that approximately "98% of the patients [in the study presented] had no comorbidities, which just does not mesh with the realities I have ever faced with adrenal patients."

The study was internally funded. Dr. Hauch reported having no financial disclosures.

While there are nuances to the surgical technique to remove the adrenal gland, what makes adrenal surgery unique is not necessarily the procedural aspect of it, but rather the clinical work-up and preoperative preparation of the patient. Adrenal tumors are often hormonally active. Depending on the type of hormonal activity, the needs of the patient before, during, and after surgery vary greatly. Is volume in this study really more of a marker for the patients who underwent appropriate work-up and treatment before surgery, and not a marker of the technical demands of the operation? And this study does not take into consideration the surgeon skill in advanced laparoscopy, as while some of these surgeons may be performing one or two adrenal cases a year, they also perform laparoscopic colon, kidney, pancreas, spleen, liver, or stomach surgery. These are cases with just as much, if not more, technical demands in the operating room.

And what about how the gland is removed? There are at least nine different surgical approaches to the adrenal gland. Is it open or is it minimally invasive? Are you approaching it from the front, the back, or laterally? Are you using the robot? And does it really matter if you are only doing two cases a year? While super-high-volume centers (they do way more than just five cases a year) are publishing their outcomes with using the robot and approaching the adrenal gland from the back, they also allude to the learning curve of the various procedures, as well as the progression in surgical approach acquisition. But what has yet to be determined is when should that additional approach be attempted? At what clinical volume does having eight different ways to take out the adrenal gland matter? Shouldn’t the first step be having one way to take out the adrenal gland that results in good outcomes? And how often do you need to perform each approach to ensure that you as the surgeon are at your best? And what about the fact that the anatomy for a right is completely different from the left? The combinations quickly become endless.

While we can continue to publish research showing high volume is better, we have to acknowledge that not all Americans have access to a high-volume surgeon. The barriers to accessing this care are complex, and are due to both system and patient factors. It is not just as simple as ensuring that everyone has health insurance.

Sarah Oltmann, M.D., is clinical instructor of endocrine surgery at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

While there are nuances to the surgical technique to remove the adrenal gland, what makes adrenal surgery unique is not necessarily the procedural aspect of it, but rather the clinical work-up and preoperative preparation of the patient. Adrenal tumors are often hormonally active. Depending on the type of hormonal activity, the needs of the patient before, during, and after surgery vary greatly. Is volume in this study really more of a marker for the patients who underwent appropriate work-up and treatment before surgery, and not a marker of the technical demands of the operation? And this study does not take into consideration the surgeon skill in advanced laparoscopy, as while some of these surgeons may be performing one or two adrenal cases a year, they also perform laparoscopic colon, kidney, pancreas, spleen, liver, or stomach surgery. These are cases with just as much, if not more, technical demands in the operating room.

And what about how the gland is removed? There are at least nine different surgical approaches to the adrenal gland. Is it open or is it minimally invasive? Are you approaching it from the front, the back, or laterally? Are you using the robot? And does it really matter if you are only doing two cases a year? While super-high-volume centers (they do way more than just five cases a year) are publishing their outcomes with using the robot and approaching the adrenal gland from the back, they also allude to the learning curve of the various procedures, as well as the progression in surgical approach acquisition. But what has yet to be determined is when should that additional approach be attempted? At what clinical volume does having eight different ways to take out the adrenal gland matter? Shouldn’t the first step be having one way to take out the adrenal gland that results in good outcomes? And how often do you need to perform each approach to ensure that you as the surgeon are at your best? And what about the fact that the anatomy for a right is completely different from the left? The combinations quickly become endless.

While we can continue to publish research showing high volume is better, we have to acknowledge that not all Americans have access to a high-volume surgeon. The barriers to accessing this care are complex, and are due to both system and patient factors. It is not just as simple as ensuring that everyone has health insurance.

Sarah Oltmann, M.D., is clinical instructor of endocrine surgery at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

While there are nuances to the surgical technique to remove the adrenal gland, what makes adrenal surgery unique is not necessarily the procedural aspect of it, but rather the clinical work-up and preoperative preparation of the patient. Adrenal tumors are often hormonally active. Depending on the type of hormonal activity, the needs of the patient before, during, and after surgery vary greatly. Is volume in this study really more of a marker for the patients who underwent appropriate work-up and treatment before surgery, and not a marker of the technical demands of the operation? And this study does not take into consideration the surgeon skill in advanced laparoscopy, as while some of these surgeons may be performing one or two adrenal cases a year, they also perform laparoscopic colon, kidney, pancreas, spleen, liver, or stomach surgery. These are cases with just as much, if not more, technical demands in the operating room.

And what about how the gland is removed? There are at least nine different surgical approaches to the adrenal gland. Is it open or is it minimally invasive? Are you approaching it from the front, the back, or laterally? Are you using the robot? And does it really matter if you are only doing two cases a year? While super-high-volume centers (they do way more than just five cases a year) are publishing their outcomes with using the robot and approaching the adrenal gland from the back, they also allude to the learning curve of the various procedures, as well as the progression in surgical approach acquisition. But what has yet to be determined is when should that additional approach be attempted? At what clinical volume does having eight different ways to take out the adrenal gland matter? Shouldn’t the first step be having one way to take out the adrenal gland that results in good outcomes? And how often do you need to perform each approach to ensure that you as the surgeon are at your best? And what about the fact that the anatomy for a right is completely different from the left? The combinations quickly become endless.

While we can continue to publish research showing high volume is better, we have to acknowledge that not all Americans have access to a high-volume surgeon. The barriers to accessing this care are complex, and are due to both system and patient factors. It is not just as simple as ensuring that everyone has health insurance.

Sarah Oltmann, M.D., is clinical instructor of endocrine surgery at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

PHOENIX – There is more evidence that it’s best to go with the pros: Adrenalectomies performed by higher-volume surgeons are associated with fewer complications, lower costs, and shorter lengths of stay than are those done by surgeons who dabble in the procedure.

The findings, presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, come from a cross-sectional study of outcomes on all patients who underwent unilateral, partial, or bilateral adrenalectomies in the United States over a 7-year span.

"The frequency of adrenalectomy has steadily increased in the United States within the last few years, and with improvement of diagnostic and imaging modalities it’s likely that the rate of adrenal surgery will continue to rise," said Dr. Adam Hauch, a research resident in the department of surgery at Tulane University, New Orleans.

The prospects for the growth in the procedure prompted Dr. Hauch and colleagues to look at clinical and economic outcomes following adrenalectomy, and to see how surgeon volume, diagnosis, and type of surgery might affect outcomes.

They drew on discharge data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project – National Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS), an administrative database sponsored by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The information included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes identifying all adult patients who underwent adrenalectomies in U.S. hospitals from 2003 through 2009. Patients were divided into benign and malignant lesion groups.

The investigators found 7,829 procedures. Mean patient age was 50 years, most of the patients (74.4%) were white, and the majority were female (58.2%) and were privately insured (58.9%). Nearly all of the patients (98.3%) had one or no comorbidities at the time of admission. Only 42 patients (0.5%) died during their hospital stays.

More than three-fourths of the procedures (79.2%) were for benign disease; the remaining 20.8% of surgeries were for malignancies.

Low-volume surgeons, defined as those who performed one or fewer adrenalectomies on average per year, performed 41.7% of all procedures, compared with 34.7% for intermediate-volume surgeons (two to five per year) and 23.6% for high-volume surgeons (more than five per year).

The vast majority (97.1%) of procedures were unilateral/partial, and approximately 95% of surgeons in each experience category performed such procedures. Procedures for malignant disease accounted for 10.6% of cases for low-volume surgeons, 6.3% for intermediate-volume docs, and 4.3% of the most prolific surgeons.

It’s complicated

Risks for any complication were significantly higher among low-volume surgeons (18.8% of their cases), compared with 14.6% for those in the middle, and 11.6% for the high-volume operators (P less than .0001). High-volume performers had significantly lower risk for cardiovascular complications (P = .0008), pulmonary complications (P = .0481), bleeding (P = .0106), and technical difficulties during surgery (P = .0024).

In an analysis adjusted for patient demographic factors, payer, primary diagnosis, obesity, comorbidities, inpatient death, admission type, hospital teaching status and volume, surgeon, and type of procedure, low-volume surgeons were nearly twice as likely as were high-volume surgeons to have complications (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.822, P less than .0001), and intermediate-volume surgeons had a nearly 1.5-fold higher risk (aOR 1.479, P = .0044).

Other risk factors for complications were bilateral vs. unilateral procedures (aOR 2.165, P = .0018), and malignant vs. benign disease (aOR 1.685, P less than .0001).

Not surprisingly, complications more than doubled mean total case charges, which ranged from $33,659 for uncomplicated unilateral cases to $73,021 for complicated cases (P = .0013), and from $47,284 for bilateral cases with no complications, to $141,461 for two-sided procedures with complications (P = .0221). Charges were higher for malignant cases than for benign cases without complications (P less than .0001), but complications brought the charges for both benign and malignant cases closer together .

Charges for noncomplicated procedures performed by high-volume surgeons were a comparative bargain at $27,324, compared with $33,499 for low- and intermediate-volume surgeons combined (P = .001). However, there were no significant differences by surgeon volume when complications arose.

Similarly, lengths of stay were prolonged when complications ensued for both unilateral cases (mean 3.7 days vs. 9.3 for complicated cases, P = .0042) and for bilateral cases (9.3 vs. 19.8, P = .025).

Higher volume surgeons managed to get patients out faster, averaging 2.7 days for cases without complications, compared with 4.2 for low/intermediate-volume surgeons (P less than .0001). When complications arose, patients of higher-volume surgeons still had shorter lengths of stay (8.5 vs. 10.4 days), but this difference was not statistically significant.

Dr. Lawrence Kim, professor of surgery at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said after the presentation that the study showed the limitations of using administrative data.

He said that approximately "98% of the patients [in the study presented] had no comorbidities, which just does not mesh with the realities I have ever faced with adrenal patients."

The study was internally funded. Dr. Hauch reported having no financial disclosures.

PHOENIX – There is more evidence that it’s best to go with the pros: Adrenalectomies performed by higher-volume surgeons are associated with fewer complications, lower costs, and shorter lengths of stay than are those done by surgeons who dabble in the procedure.

The findings, presented at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, come from a cross-sectional study of outcomes on all patients who underwent unilateral, partial, or bilateral adrenalectomies in the United States over a 7-year span.

"The frequency of adrenalectomy has steadily increased in the United States within the last few years, and with improvement of diagnostic and imaging modalities it’s likely that the rate of adrenal surgery will continue to rise," said Dr. Adam Hauch, a research resident in the department of surgery at Tulane University, New Orleans.

The prospects for the growth in the procedure prompted Dr. Hauch and colleagues to look at clinical and economic outcomes following adrenalectomy, and to see how surgeon volume, diagnosis, and type of surgery might affect outcomes.

They drew on discharge data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project – National Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS), an administrative database sponsored by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The information included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes identifying all adult patients who underwent adrenalectomies in U.S. hospitals from 2003 through 2009. Patients were divided into benign and malignant lesion groups.

The investigators found 7,829 procedures. Mean patient age was 50 years, most of the patients (74.4%) were white, and the majority were female (58.2%) and were privately insured (58.9%). Nearly all of the patients (98.3%) had one or no comorbidities at the time of admission. Only 42 patients (0.5%) died during their hospital stays.

More than three-fourths of the procedures (79.2%) were for benign disease; the remaining 20.8% of surgeries were for malignancies.

Low-volume surgeons, defined as those who performed one or fewer adrenalectomies on average per year, performed 41.7% of all procedures, compared with 34.7% for intermediate-volume surgeons (two to five per year) and 23.6% for high-volume surgeons (more than five per year).

The vast majority (97.1%) of procedures were unilateral/partial, and approximately 95% of surgeons in each experience category performed such procedures. Procedures for malignant disease accounted for 10.6% of cases for low-volume surgeons, 6.3% for intermediate-volume docs, and 4.3% of the most prolific surgeons.

It’s complicated

Risks for any complication were significantly higher among low-volume surgeons (18.8% of their cases), compared with 14.6% for those in the middle, and 11.6% for the high-volume operators (P less than .0001). High-volume performers had significantly lower risk for cardiovascular complications (P = .0008), pulmonary complications (P = .0481), bleeding (P = .0106), and technical difficulties during surgery (P = .0024).

In an analysis adjusted for patient demographic factors, payer, primary diagnosis, obesity, comorbidities, inpatient death, admission type, hospital teaching status and volume, surgeon, and type of procedure, low-volume surgeons were nearly twice as likely as were high-volume surgeons to have complications (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.822, P less than .0001), and intermediate-volume surgeons had a nearly 1.5-fold higher risk (aOR 1.479, P = .0044).

Other risk factors for complications were bilateral vs. unilateral procedures (aOR 2.165, P = .0018), and malignant vs. benign disease (aOR 1.685, P less than .0001).

Not surprisingly, complications more than doubled mean total case charges, which ranged from $33,659 for uncomplicated unilateral cases to $73,021 for complicated cases (P = .0013), and from $47,284 for bilateral cases with no complications, to $141,461 for two-sided procedures with complications (P = .0221). Charges were higher for malignant cases than for benign cases without complications (P less than .0001), but complications brought the charges for both benign and malignant cases closer together .

Charges for noncomplicated procedures performed by high-volume surgeons were a comparative bargain at $27,324, compared with $33,499 for low- and intermediate-volume surgeons combined (P = .001). However, there were no significant differences by surgeon volume when complications arose.

Similarly, lengths of stay were prolonged when complications ensued for both unilateral cases (mean 3.7 days vs. 9.3 for complicated cases, P = .0042) and for bilateral cases (9.3 vs. 19.8, P = .025).

Higher volume surgeons managed to get patients out faster, averaging 2.7 days for cases without complications, compared with 4.2 for low/intermediate-volume surgeons (P less than .0001). When complications arose, patients of higher-volume surgeons still had shorter lengths of stay (8.5 vs. 10.4 days), but this difference was not statistically significant.

Dr. Lawrence Kim, professor of surgery at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said after the presentation that the study showed the limitations of using administrative data.

He said that approximately "98% of the patients [in the study presented] had no comorbidities, which just does not mesh with the realities I have ever faced with adrenal patients."

The study was internally funded. Dr. Hauch reported having no financial disclosures.

AT SSO 2014

Major finding: Patients of low-volume surgeons were nearly twice as likely as were those of high-volume surgeons to have complications following adrenalectomy (adjusted odds ratio 1.822, P less than .0001).

Data source: Cross-sectional analysis of data on 7,829 patients.

Disclosures: The study was internally funded. Dr. Hauch reported having no financial disclosures.

Autoimmune disease coalition seeks to increase physician knowledge

WASHINGTON – Some 64% of family physicians are "uncomfortable" or "stressed" when diagnosing autoimmune disease, and almost three-quarters said they have not been given adequate training in diagnosing and treating the conditions, according to a small survey.

The survey of 130 family physicians was conducted by the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association (AARDA) last fall. The association has queried physicians each year since the mid-1990s on a variety of issues relating to the care and treatment of patients with any one of the 100 or so diseases that fall into the autoimmune category.

The AARDA, along with the National Coalition of Autoimmune Patient Groups, is pushing for more comprehensive autoimmune disorder centers where patients can receive focused and coordinated care from specialists who are more intimately involved with the diseases.

The autoimmune facilities would be modeled on comprehensive cancer centers.

Now, patients struggle to find specialists who can accurately diagnose and treat their conditions. "There’s no such thing as the autoimmunologist," said Stanley Finger, Ph.D., the AARDA’s vice chairman of the board, at a briefing.

Patients responding to AARDA surveys report that it takes 4-5 years to get an accurate diagnosis, and that they see an average of five physicians before they get that diagnosis. At least half of patients are labeled chronic complainers and told that their symptoms are figments of their imagination, Dr. Finger said.

But 75% say they would seek care at a specialized center if it existed.

Improving diagnosis also requires increasing physician awareness and education. In the AARDA’s most recent survey, almost 60% of family physicians said that they had only one or two lectures on autoimmune disease in medical school, said Dr. Finger, who is also president of Environmental Consulting and Investigations in Bluffton, S.C.

"It doesn’t give a lot of time for these physicians to become experts," Dr. Finger said. "Because of that, they don’t feel very good about the training they have received."

The AARDA plans to develop a syllabus for medical schools and a continuing education program to help fill physicians’ knowledge gaps.

The group also surveys about 1,000 members of the general public every 5-7 years to gauge awareness of how patients are interacting with physicians. In 1992, only 5% could name an autoimmune disease. That has increased, but only to 15%. In the first survey, 93% of the public thought AIDS was an autoimmune disease. Now, just 21% have that belief.

Borrowing another page from the cancer model, the AARDA and the coalition are seeking to establish an autoimmune disease registry that would be similar to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. The SEER program compiles data about cancer incidence, mortality, and cost. It is widely used by researchers, patients, physicians, and public health agencies.

The autoimmune registry is still a work in progress. There is a huge absence of data in the autoimmune field – for example, no one knows with certainty just how many Americans have any of the various conditions, said Aaron H. Abend, the AARDA’s informatics director.

The registry would aggregate data already being compiled by various individual autoimmune associations. But the effort is in its infancy. The groups still need to agree on governance, data protocols, and other issues, Mr. Abend said. However, the registry will use software that is the standard for registries operated by the National Institutes of Health.

aault@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – Some 64% of family physicians are "uncomfortable" or "stressed" when diagnosing autoimmune disease, and almost three-quarters said they have not been given adequate training in diagnosing and treating the conditions, according to a small survey.

The survey of 130 family physicians was conducted by the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association (AARDA) last fall. The association has queried physicians each year since the mid-1990s on a variety of issues relating to the care and treatment of patients with any one of the 100 or so diseases that fall into the autoimmune category.

The AARDA, along with the National Coalition of Autoimmune Patient Groups, is pushing for more comprehensive autoimmune disorder centers where patients can receive focused and coordinated care from specialists who are more intimately involved with the diseases.

The autoimmune facilities would be modeled on comprehensive cancer centers.

Now, patients struggle to find specialists who can accurately diagnose and treat their conditions. "There’s no such thing as the autoimmunologist," said Stanley Finger, Ph.D., the AARDA’s vice chairman of the board, at a briefing.

Patients responding to AARDA surveys report that it takes 4-5 years to get an accurate diagnosis, and that they see an average of five physicians before they get that diagnosis. At least half of patients are labeled chronic complainers and told that their symptoms are figments of their imagination, Dr. Finger said.

But 75% say they would seek care at a specialized center if it existed.

Improving diagnosis also requires increasing physician awareness and education. In the AARDA’s most recent survey, almost 60% of family physicians said that they had only one or two lectures on autoimmune disease in medical school, said Dr. Finger, who is also president of Environmental Consulting and Investigations in Bluffton, S.C.

"It doesn’t give a lot of time for these physicians to become experts," Dr. Finger said. "Because of that, they don’t feel very good about the training they have received."

The AARDA plans to develop a syllabus for medical schools and a continuing education program to help fill physicians’ knowledge gaps.

The group also surveys about 1,000 members of the general public every 5-7 years to gauge awareness of how patients are interacting with physicians. In 1992, only 5% could name an autoimmune disease. That has increased, but only to 15%. In the first survey, 93% of the public thought AIDS was an autoimmune disease. Now, just 21% have that belief.

Borrowing another page from the cancer model, the AARDA and the coalition are seeking to establish an autoimmune disease registry that would be similar to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. The SEER program compiles data about cancer incidence, mortality, and cost. It is widely used by researchers, patients, physicians, and public health agencies.

The autoimmune registry is still a work in progress. There is a huge absence of data in the autoimmune field – for example, no one knows with certainty just how many Americans have any of the various conditions, said Aaron H. Abend, the AARDA’s informatics director.

The registry would aggregate data already being compiled by various individual autoimmune associations. But the effort is in its infancy. The groups still need to agree on governance, data protocols, and other issues, Mr. Abend said. However, the registry will use software that is the standard for registries operated by the National Institutes of Health.

aault@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – Some 64% of family physicians are "uncomfortable" or "stressed" when diagnosing autoimmune disease, and almost three-quarters said they have not been given adequate training in diagnosing and treating the conditions, according to a small survey.

The survey of 130 family physicians was conducted by the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association (AARDA) last fall. The association has queried physicians each year since the mid-1990s on a variety of issues relating to the care and treatment of patients with any one of the 100 or so diseases that fall into the autoimmune category.

The AARDA, along with the National Coalition of Autoimmune Patient Groups, is pushing for more comprehensive autoimmune disorder centers where patients can receive focused and coordinated care from specialists who are more intimately involved with the diseases.

The autoimmune facilities would be modeled on comprehensive cancer centers.

Now, patients struggle to find specialists who can accurately diagnose and treat their conditions. "There’s no such thing as the autoimmunologist," said Stanley Finger, Ph.D., the AARDA’s vice chairman of the board, at a briefing.

Patients responding to AARDA surveys report that it takes 4-5 years to get an accurate diagnosis, and that they see an average of five physicians before they get that diagnosis. At least half of patients are labeled chronic complainers and told that their symptoms are figments of their imagination, Dr. Finger said.

But 75% say they would seek care at a specialized center if it existed.

Improving diagnosis also requires increasing physician awareness and education. In the AARDA’s most recent survey, almost 60% of family physicians said that they had only one or two lectures on autoimmune disease in medical school, said Dr. Finger, who is also president of Environmental Consulting and Investigations in Bluffton, S.C.

"It doesn’t give a lot of time for these physicians to become experts," Dr. Finger said. "Because of that, they don’t feel very good about the training they have received."

The AARDA plans to develop a syllabus for medical schools and a continuing education program to help fill physicians’ knowledge gaps.

The group also surveys about 1,000 members of the general public every 5-7 years to gauge awareness of how patients are interacting with physicians. In 1992, only 5% could name an autoimmune disease. That has increased, but only to 15%. In the first survey, 93% of the public thought AIDS was an autoimmune disease. Now, just 21% have that belief.

Borrowing another page from the cancer model, the AARDA and the coalition are seeking to establish an autoimmune disease registry that would be similar to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. The SEER program compiles data about cancer incidence, mortality, and cost. It is widely used by researchers, patients, physicians, and public health agencies.

The autoimmune registry is still a work in progress. There is a huge absence of data in the autoimmune field – for example, no one knows with certainty just how many Americans have any of the various conditions, said Aaron H. Abend, the AARDA’s informatics director.

The registry would aggregate data already being compiled by various individual autoimmune associations. But the effort is in its infancy. The groups still need to agree on governance, data protocols, and other issues, Mr. Abend said. However, the registry will use software that is the standard for registries operated by the National Institutes of Health.

aault@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @aliciaault

FROM A MEDIA BRIEFING BY THE AMERICAN AUTOIMMUNE RELATED DISEASES ASSOCIATION

Antiphospholipid, thrombosis histories differently affect pregnancy antithrombotic needs

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Whether a woman with antiphospholipid antibodies meets diagnostic criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome makes a huge difference in her risk of pregnancy failure.

Having antiphospholipid antibodies alone confers only a modest increase in the risks of thrombosis and/or pregnancy mishap, Dr. Megan E.B. Clowse said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium, sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

"You don’t have to jump all over these patients and get them worked up into a tizzy that they’re going to have blood clots or major pregnancy problems if they’ve never had them before," said Dr. Clowse, director of the Duke University Autoimmunity in Pregnancy registry in Durham, N.C.

The published experience indicates that women with antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) but not antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) have roughly a 15% rate of pregnancy loss in their first pregnancy, not much different than the 11% rate in the general population. In contrast, women with untreated APS have up to a 90% pregnancy loss rate. With aspirin at 81 mg/day, this rate drops to 50%, and with dual therapy of low-dose aspirin plus either low-molecular-weight (LMW) or unfractionated heparin, the risk falls further to 25%, still twice that of the general population.

Thus, the distinction between aPL and APS is key. In addition to its implications for pregnancy outcome, it also guides the duration of anticoagulation following thrombosis. Anticoagulation needs to continue indefinitely in patients with APS because of their high risk of another clotting event. Indeed, patients with APS, if left untreated after a thrombotic event, have a 25% chance of another event within the next year, the rheumatologist noted.

"The diagnosis of APS is actually straightforward, but in patients referred to our lupus clinic from outside I see the term being used pretty fast and loose, and I think it’s somewhat inappropriate to do so. There are many patients with antiphospholipid antibodies who don’t have APS," she continued.

The current diagnostic criteria for APS – the so-called Sydney criteria (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:295-306) – require both laboratory and clinical findings. The laboratory criteria require a finding of lupus anticoagulant, medium- or high-titer IgG or IgM anticardiolipin antibodies, and/or medium- or high-titer anti-beta2-glycoprotein-1 antibody. The test results need to be positive on two occasions 12 weeks apart, although treatment for presumptive APS can start after tentative diagnosis based upon the first positive test.

To meet the vascular criteria for APS, a patient simply has to have had an arterial, venous, or small vessel thrombosis in any tissue or organ. The pregnancy criteria are more elaborate. To qualify, a woman must have had spontaneous abortions at less than 10 weeks’ gestation in at least three or more consecutive pregnancies, or a second- or third-trimester pregnancy loss of a normal fetus, or premature birth of a morphologically normal fetus before week 34 due to preeclampsia or placental insufficiency.

In women with full-blown APS, antibody titers matter quite a bit in terms of pregnancy outcome. In a study of 51 women with APS who were treated with LMW heparin and aspirin throughout 55 pregnancies, the 20 women with antibody titers greater than four times the upper limit of normal had a 35% rate of delivering an appropriately grown baby after 32 weeks’ gestation. The 35 antibody-positive women with titers less than four times the upper limit of normal had a 77% rate of normal delivery (Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2011;90:1428-33).

In women with aPL only, the risk of pregnancy loss may be so low that aspirin isn’t protective. In an intriguing Italian study of 139 pregnancies in 114 women with aPL but not APS, the pregnancy loss rate in 104 pregnancies treated throughout with low-dose aspirin was 7.7%, while in 35 untreated pregnancies the rate was 2.9% (J. Rheumatol. 2013;40:425-9).

"The conclusion here is you can go ahead and use aspirin, but we don’t know that it’s doing a whole lot. Maybe we’re really just treating ourselves," Dr. Clowse mused.

Evidence from the PROMISSE trial, the largest-ever U.S. study of pregnancy loss in lupus patients, points to lupus anticoagulant as the main driver of pregnancy morbidity in patients with aPL. Thirty-nine percent of lupus anticoagulant–positive patients had adverse pregnancy outcomes, compared with just 3% of those without lupus anticoagulant. Unfortunately, treatment with heparin, aspirin, prednisone, or hydroxychloroquine didn’t mitigate the risk (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2311-8).

While pregnancy loss is the biggest concern among most women with APS, it’s important to watch for maternal complications, including early severe preeclampsia, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome, and thrombotic events.

"It’s worth talking to the woman before pregnancy and explaining that, unfortunately, pregnancy loss is not necessarily the worst thing that can happen. Her health can also be at risk," Dr. Clowse observed.

In her own practice, everybody with APS goes on aspirin at 81 mg/day throughout pregnancy, even if there has been no prior pregnancy loss. With a history of three or more consecutive pregnancy losses, the treatment is low-dose LMW heparin plus low-dose aspirin. In women with a history of pregnancy loss that doesn’t reach that level, there is no good evidence to provide guidance as to whether to use low-dose LMW heparin plus aspirin or aspirin alone; however, she tends to be more aggressive in women with lupus anticoagulant or very high titers of the other aPLs. Women with a history of thrombosis, whether arterial or venous, are encouraged to remain on full-dose LMW heparin plus low-dose aspirin throughout pregnancy.

Dr. Clowse reported serving as a consultant to UCB.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Whether a woman with antiphospholipid antibodies meets diagnostic criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome makes a huge difference in her risk of pregnancy failure.

Having antiphospholipid antibodies alone confers only a modest increase in the risks of thrombosis and/or pregnancy mishap, Dr. Megan E.B. Clowse said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium, sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

"You don’t have to jump all over these patients and get them worked up into a tizzy that they’re going to have blood clots or major pregnancy problems if they’ve never had them before," said Dr. Clowse, director of the Duke University Autoimmunity in Pregnancy registry in Durham, N.C.

The published experience indicates that women with antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) but not antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) have roughly a 15% rate of pregnancy loss in their first pregnancy, not much different than the 11% rate in the general population. In contrast, women with untreated APS have up to a 90% pregnancy loss rate. With aspirin at 81 mg/day, this rate drops to 50%, and with dual therapy of low-dose aspirin plus either low-molecular-weight (LMW) or unfractionated heparin, the risk falls further to 25%, still twice that of the general population.

Thus, the distinction between aPL and APS is key. In addition to its implications for pregnancy outcome, it also guides the duration of anticoagulation following thrombosis. Anticoagulation needs to continue indefinitely in patients with APS because of their high risk of another clotting event. Indeed, patients with APS, if left untreated after a thrombotic event, have a 25% chance of another event within the next year, the rheumatologist noted.

"The diagnosis of APS is actually straightforward, but in patients referred to our lupus clinic from outside I see the term being used pretty fast and loose, and I think it’s somewhat inappropriate to do so. There are many patients with antiphospholipid antibodies who don’t have APS," she continued.

The current diagnostic criteria for APS – the so-called Sydney criteria (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:295-306) – require both laboratory and clinical findings. The laboratory criteria require a finding of lupus anticoagulant, medium- or high-titer IgG or IgM anticardiolipin antibodies, and/or medium- or high-titer anti-beta2-glycoprotein-1 antibody. The test results need to be positive on two occasions 12 weeks apart, although treatment for presumptive APS can start after tentative diagnosis based upon the first positive test.

To meet the vascular criteria for APS, a patient simply has to have had an arterial, venous, or small vessel thrombosis in any tissue or organ. The pregnancy criteria are more elaborate. To qualify, a woman must have had spontaneous abortions at less than 10 weeks’ gestation in at least three or more consecutive pregnancies, or a second- or third-trimester pregnancy loss of a normal fetus, or premature birth of a morphologically normal fetus before week 34 due to preeclampsia or placental insufficiency.

In women with full-blown APS, antibody titers matter quite a bit in terms of pregnancy outcome. In a study of 51 women with APS who were treated with LMW heparin and aspirin throughout 55 pregnancies, the 20 women with antibody titers greater than four times the upper limit of normal had a 35% rate of delivering an appropriately grown baby after 32 weeks’ gestation. The 35 antibody-positive women with titers less than four times the upper limit of normal had a 77% rate of normal delivery (Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2011;90:1428-33).

In women with aPL only, the risk of pregnancy loss may be so low that aspirin isn’t protective. In an intriguing Italian study of 139 pregnancies in 114 women with aPL but not APS, the pregnancy loss rate in 104 pregnancies treated throughout with low-dose aspirin was 7.7%, while in 35 untreated pregnancies the rate was 2.9% (J. Rheumatol. 2013;40:425-9).

"The conclusion here is you can go ahead and use aspirin, but we don’t know that it’s doing a whole lot. Maybe we’re really just treating ourselves," Dr. Clowse mused.

Evidence from the PROMISSE trial, the largest-ever U.S. study of pregnancy loss in lupus patients, points to lupus anticoagulant as the main driver of pregnancy morbidity in patients with aPL. Thirty-nine percent of lupus anticoagulant–positive patients had adverse pregnancy outcomes, compared with just 3% of those without lupus anticoagulant. Unfortunately, treatment with heparin, aspirin, prednisone, or hydroxychloroquine didn’t mitigate the risk (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2311-8).

While pregnancy loss is the biggest concern among most women with APS, it’s important to watch for maternal complications, including early severe preeclampsia, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome, and thrombotic events.

"It’s worth talking to the woman before pregnancy and explaining that, unfortunately, pregnancy loss is not necessarily the worst thing that can happen. Her health can also be at risk," Dr. Clowse observed.