User login

Optimal psychiatric treatment: Target the brain and avoid the body

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

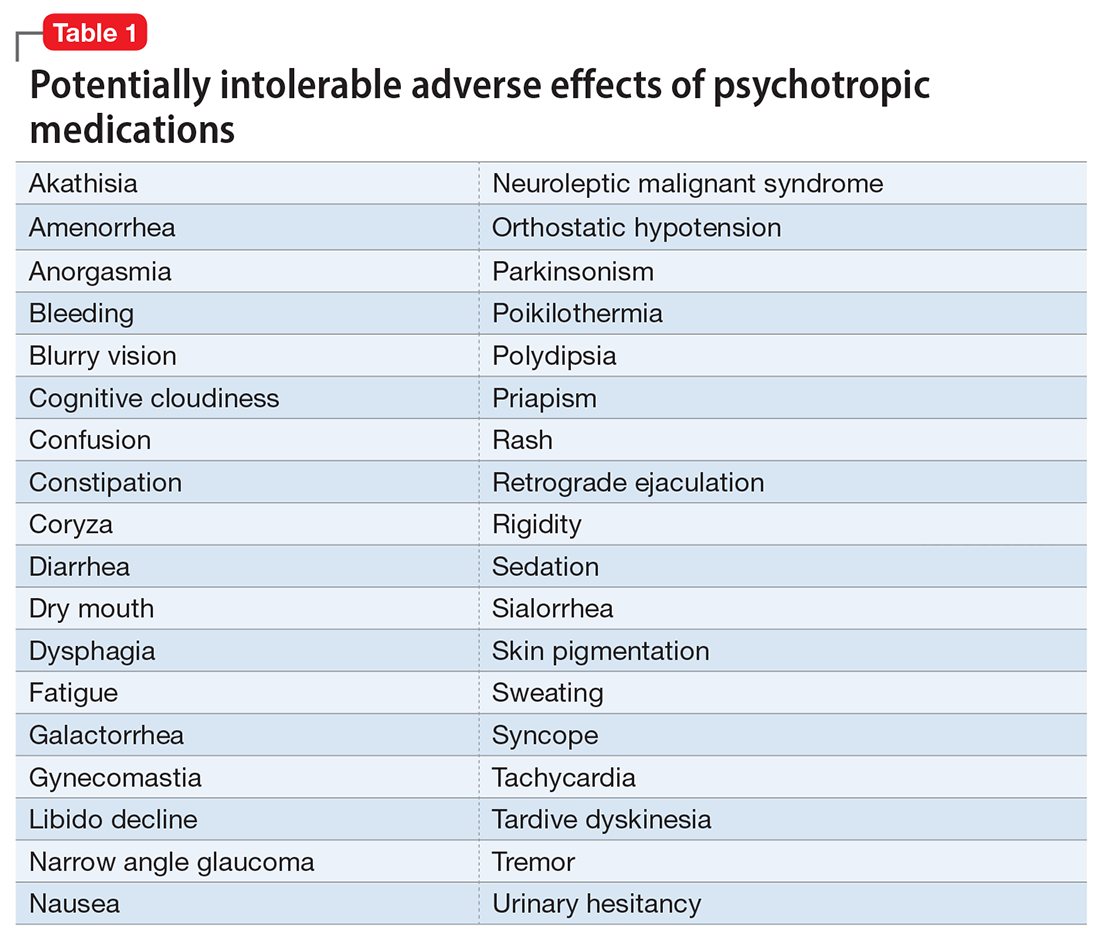

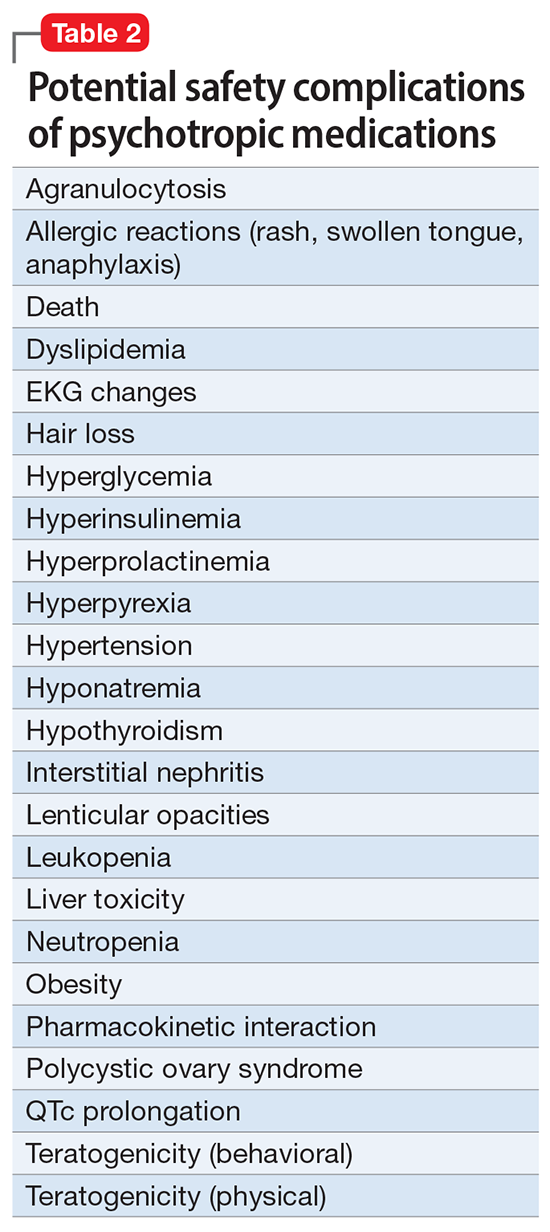

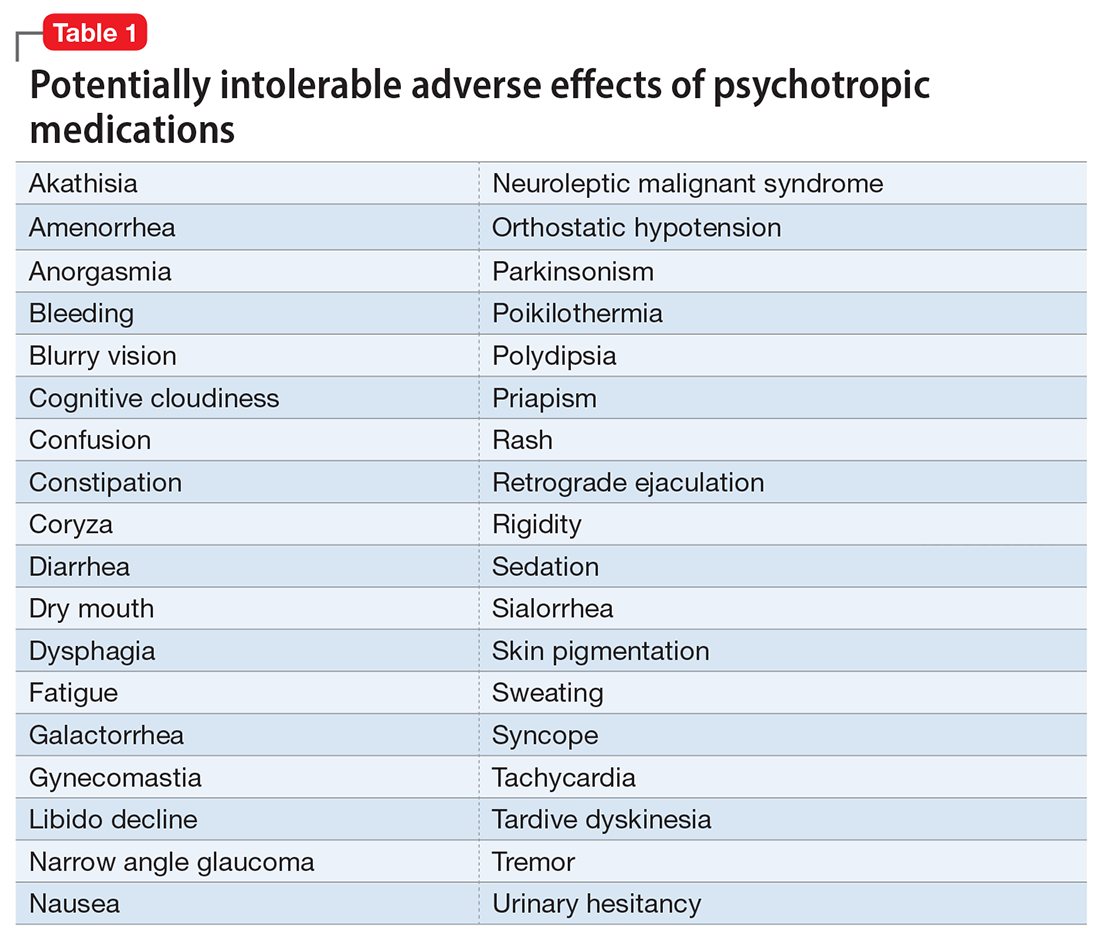

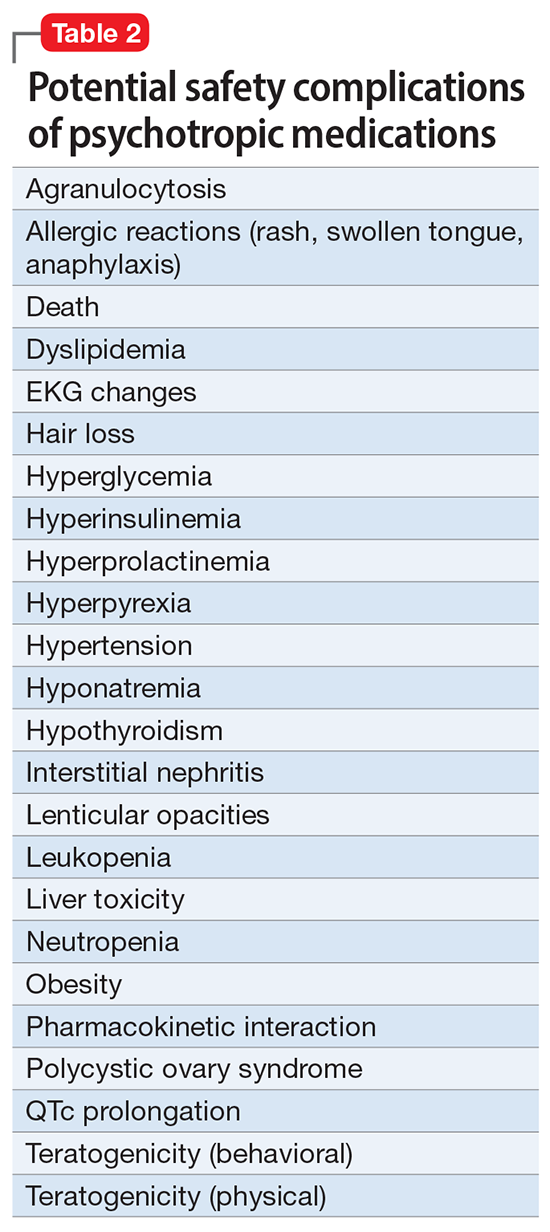

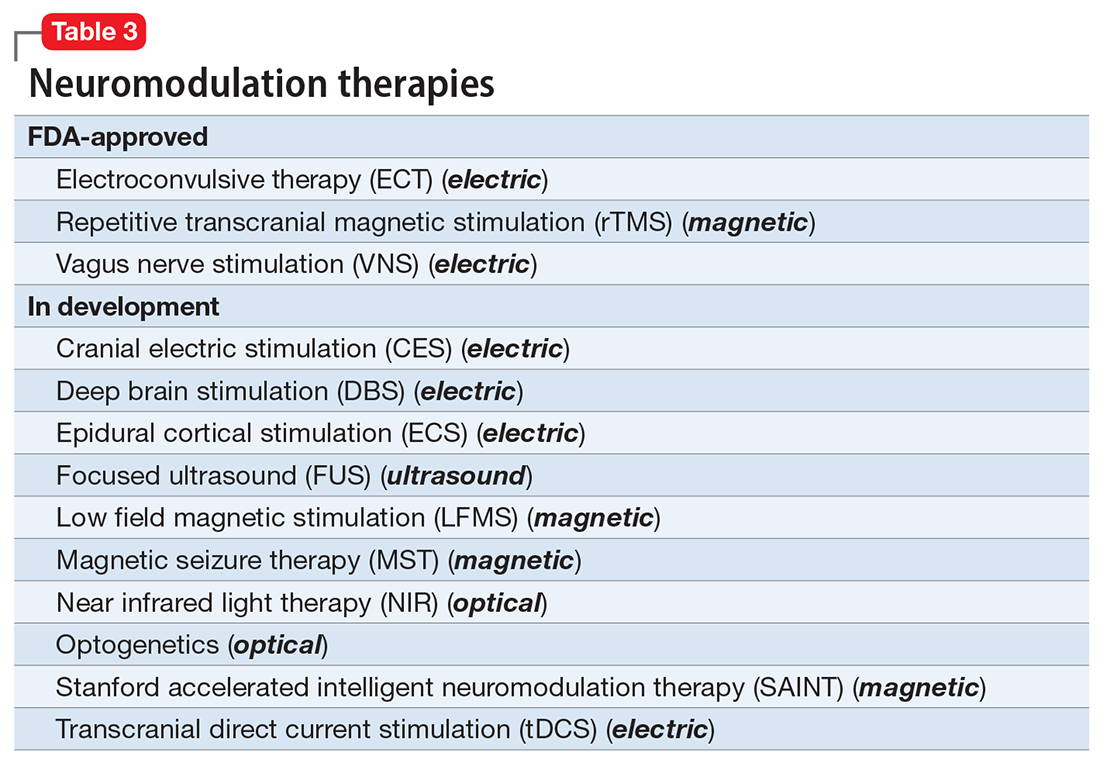

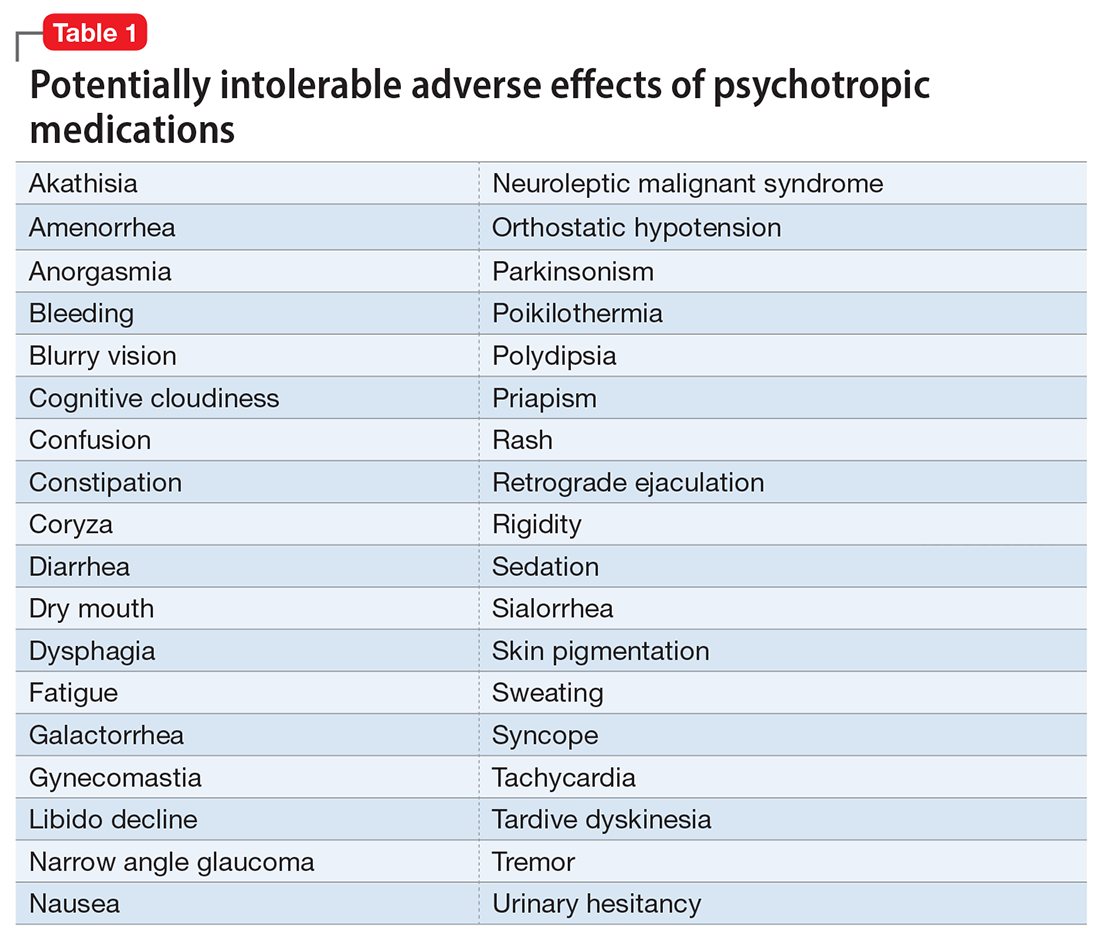

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

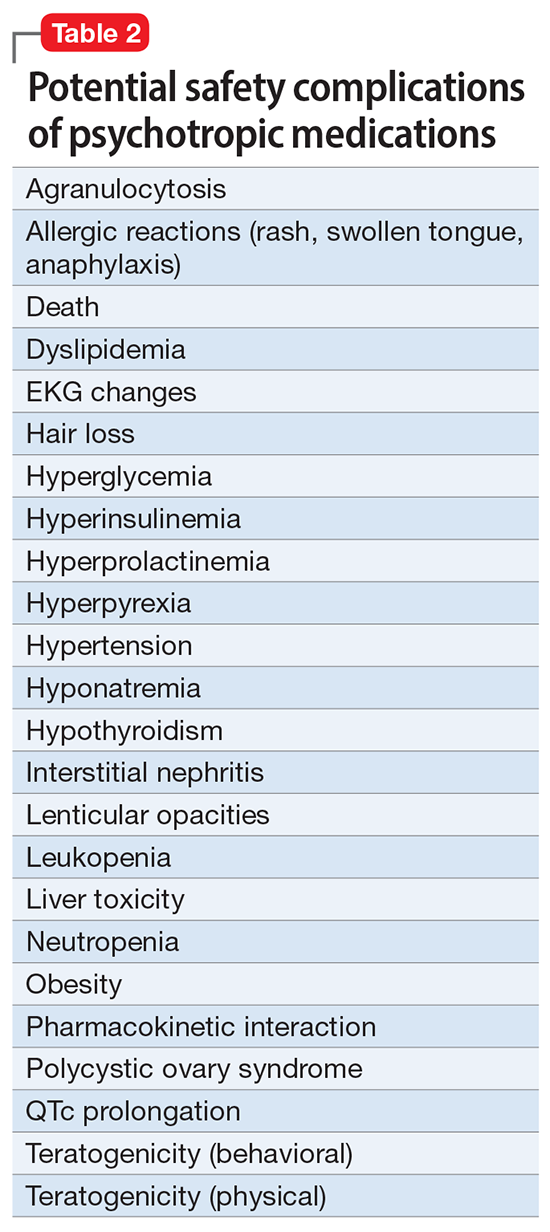

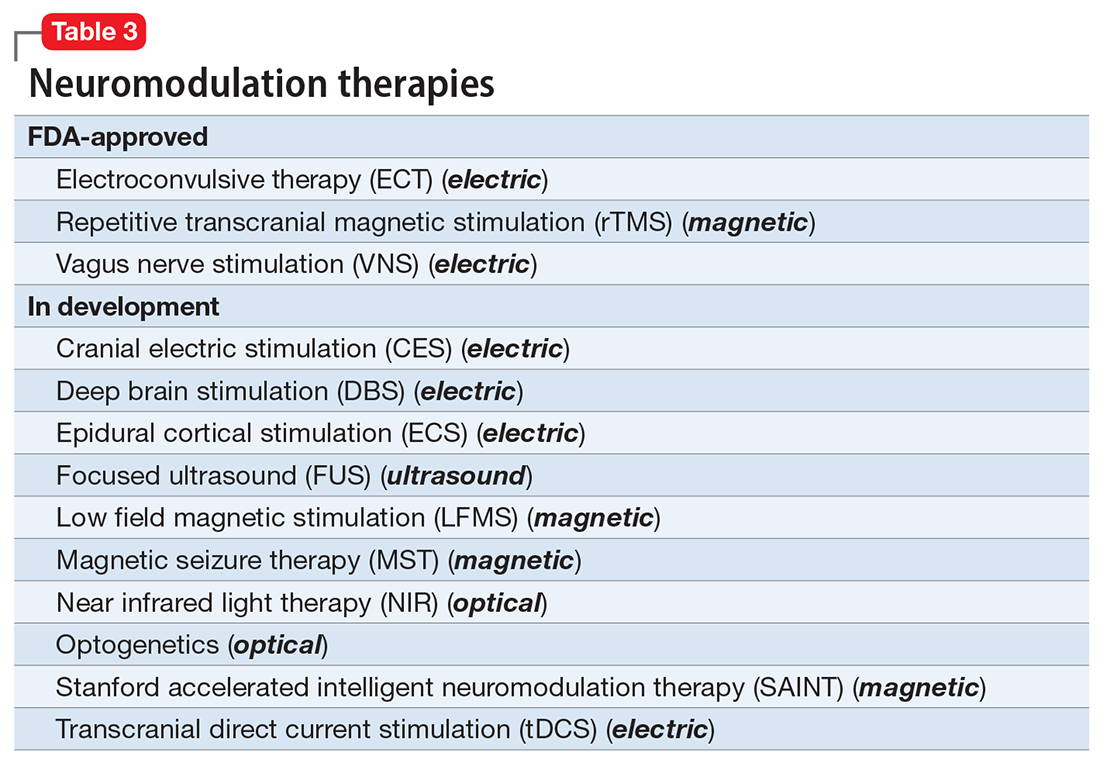

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

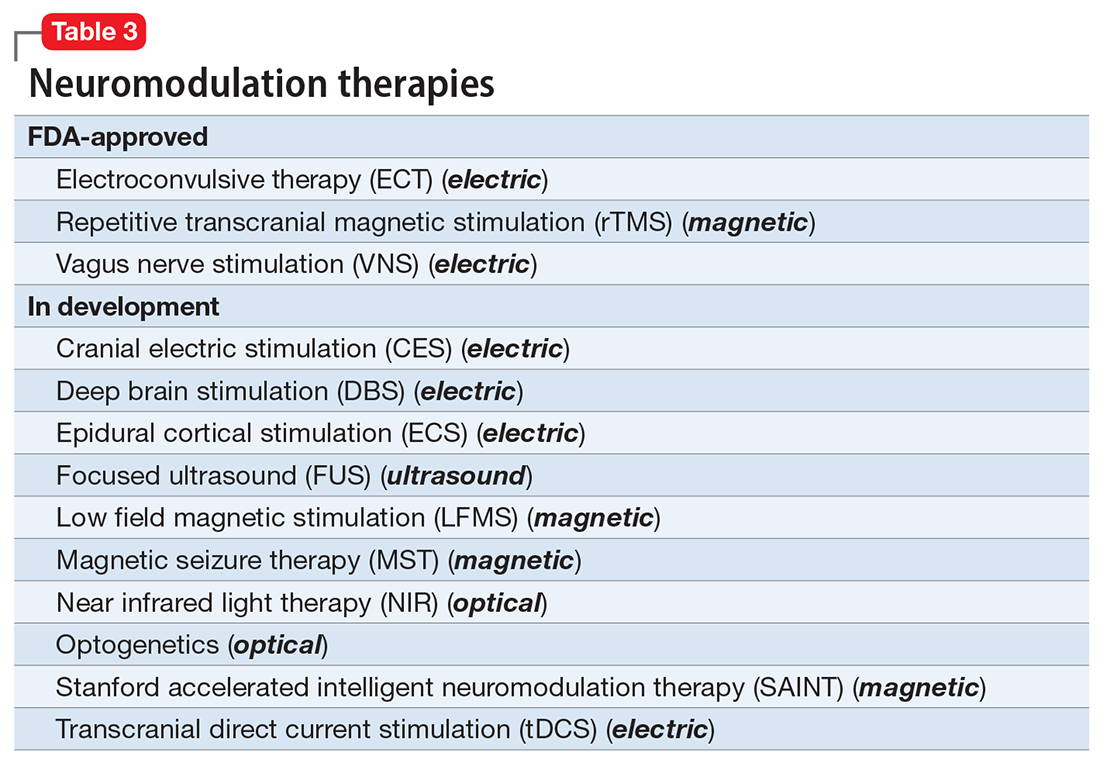

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

A new ultrabrief screening scale for pediatric OCD

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 1-2% of the population. The disorder is characterized by recurrent intrusive unwanted thoughts (obsessions) that cause significant distress and anxiety, and behavioral or mental rituals (compulsions) that are performed to reduce distress stemming from obsessions. OCD may onset at any time in life, but most commonly begins in childhood or in early adulthood.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention is an empirically based and highly effective treatment for OCD. However, most youth with OCD do not receive any treatment, which is related to a shortage of mental health care providers with expertise in assessment and treatment of the disorder, and misdiagnosis of the disorder is all too prevalent.

Aside from the subjective emotional toll associated with OCD, individuals living with this disorder frequently experience interpersonal, academic, and vocational impairments. Nevertheless, OCD is often overlooked or misdiagnosed. This may be more pronounced in youth with OCD, particularly in primary health care settings and large nonspecialized medical institutions. In fact, research indicates that pediatric OCD is often underrecognized even among mental health professionals. This situation is not new, and in fact the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom stated that there is an urgent need to develop brief reliable screeners for OCD nearly 20 years ago.

Although there were several attempts to develop brief screening scales for adults and youth with OCD, none of them were found to be suitable for use as rapid screening tools in nonspecialized settings. One of the primary reasons is that OCD is associated with different “themes” or dimensions. For example, a child with OCD may engage in cleaning rituals because the context (or dimension) of their obsessions is contamination concerns. Another child with OCD, who may suffer from similar overall symptom severity, may primarily engage in checking rituals which are related with obsessions associated with fear of being responsible for harm. Therefore, one child with OCD may score very high on items assessing one dimension (e.g., contamination concerns), but very low on another dimension (e.g., harm obsessions).

This results in a known challenge in the assessment and psychometrics of self-report (as opposed to clinician administered) measures of OCD. Secondly, development of such measures requires very large carefully screened samples of individuals with OCD, with other disorders, and those without a known psychological disorder – which may be more challenging than requiring adult participants.

To accomplish this, we harmonized data from several sites that included three samples of carefully screened youths with OCD, with other disorders, and without known disorders who completed multiple self-report questionnaires, including the 21-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV).

Utilizing psychometric analyses including factor analyses, invariance analyses, and item response theory methodologies, we were able to develop an ultrabrief measure extracted from the OCI-CV: the 5-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV-5). This very brief self-report measure was found to have very good psychometric properties including a sensitive and specific clinical cutoff score. Youth who score at or above the cutoff score are nearly 21 times more likely to meet criteria for OCD.

This measure corresponds to a need to rapidly screen for OCD in children in nonspecialized settings, including community mental health clinics, primary care settings, and pediatric treatment facilities. However, it is important to note it is not a diagnostic measure. The measure is intended to identify youth who should be referred to a mental health care professional to conduct a diagnostic interview.

Dr. Abramovitch is a clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist based in Austin, Tex., and an associate professor at Texas State University. Dr. Abramowitz is professor and director of clinical training in the Anxiety and Stress Lab at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. McKay is professor of psychology at Fordham University, Bronx, N.Y.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 1-2% of the population. The disorder is characterized by recurrent intrusive unwanted thoughts (obsessions) that cause significant distress and anxiety, and behavioral or mental rituals (compulsions) that are performed to reduce distress stemming from obsessions. OCD may onset at any time in life, but most commonly begins in childhood or in early adulthood.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention is an empirically based and highly effective treatment for OCD. However, most youth with OCD do not receive any treatment, which is related to a shortage of mental health care providers with expertise in assessment and treatment of the disorder, and misdiagnosis of the disorder is all too prevalent.

Aside from the subjective emotional toll associated with OCD, individuals living with this disorder frequently experience interpersonal, academic, and vocational impairments. Nevertheless, OCD is often overlooked or misdiagnosed. This may be more pronounced in youth with OCD, particularly in primary health care settings and large nonspecialized medical institutions. In fact, research indicates that pediatric OCD is often underrecognized even among mental health professionals. This situation is not new, and in fact the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom stated that there is an urgent need to develop brief reliable screeners for OCD nearly 20 years ago.

Although there were several attempts to develop brief screening scales for adults and youth with OCD, none of them were found to be suitable for use as rapid screening tools in nonspecialized settings. One of the primary reasons is that OCD is associated with different “themes” or dimensions. For example, a child with OCD may engage in cleaning rituals because the context (or dimension) of their obsessions is contamination concerns. Another child with OCD, who may suffer from similar overall symptom severity, may primarily engage in checking rituals which are related with obsessions associated with fear of being responsible for harm. Therefore, one child with OCD may score very high on items assessing one dimension (e.g., contamination concerns), but very low on another dimension (e.g., harm obsessions).

This results in a known challenge in the assessment and psychometrics of self-report (as opposed to clinician administered) measures of OCD. Secondly, development of such measures requires very large carefully screened samples of individuals with OCD, with other disorders, and those without a known psychological disorder – which may be more challenging than requiring adult participants.

To accomplish this, we harmonized data from several sites that included three samples of carefully screened youths with OCD, with other disorders, and without known disorders who completed multiple self-report questionnaires, including the 21-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV).

Utilizing psychometric analyses including factor analyses, invariance analyses, and item response theory methodologies, we were able to develop an ultrabrief measure extracted from the OCI-CV: the 5-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV-5). This very brief self-report measure was found to have very good psychometric properties including a sensitive and specific clinical cutoff score. Youth who score at or above the cutoff score are nearly 21 times more likely to meet criteria for OCD.

This measure corresponds to a need to rapidly screen for OCD in children in nonspecialized settings, including community mental health clinics, primary care settings, and pediatric treatment facilities. However, it is important to note it is not a diagnostic measure. The measure is intended to identify youth who should be referred to a mental health care professional to conduct a diagnostic interview.

Dr. Abramovitch is a clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist based in Austin, Tex., and an associate professor at Texas State University. Dr. Abramowitz is professor and director of clinical training in the Anxiety and Stress Lab at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. McKay is professor of psychology at Fordham University, Bronx, N.Y.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 1-2% of the population. The disorder is characterized by recurrent intrusive unwanted thoughts (obsessions) that cause significant distress and anxiety, and behavioral or mental rituals (compulsions) that are performed to reduce distress stemming from obsessions. OCD may onset at any time in life, but most commonly begins in childhood or in early adulthood.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention is an empirically based and highly effective treatment for OCD. However, most youth with OCD do not receive any treatment, which is related to a shortage of mental health care providers with expertise in assessment and treatment of the disorder, and misdiagnosis of the disorder is all too prevalent.

Aside from the subjective emotional toll associated with OCD, individuals living with this disorder frequently experience interpersonal, academic, and vocational impairments. Nevertheless, OCD is often overlooked or misdiagnosed. This may be more pronounced in youth with OCD, particularly in primary health care settings and large nonspecialized medical institutions. In fact, research indicates that pediatric OCD is often underrecognized even among mental health professionals. This situation is not new, and in fact the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom stated that there is an urgent need to develop brief reliable screeners for OCD nearly 20 years ago.

Although there were several attempts to develop brief screening scales for adults and youth with OCD, none of them were found to be suitable for use as rapid screening tools in nonspecialized settings. One of the primary reasons is that OCD is associated with different “themes” or dimensions. For example, a child with OCD may engage in cleaning rituals because the context (or dimension) of their obsessions is contamination concerns. Another child with OCD, who may suffer from similar overall symptom severity, may primarily engage in checking rituals which are related with obsessions associated with fear of being responsible for harm. Therefore, one child with OCD may score very high on items assessing one dimension (e.g., contamination concerns), but very low on another dimension (e.g., harm obsessions).

This results in a known challenge in the assessment and psychometrics of self-report (as opposed to clinician administered) measures of OCD. Secondly, development of such measures requires very large carefully screened samples of individuals with OCD, with other disorders, and those without a known psychological disorder – which may be more challenging than requiring adult participants.

To accomplish this, we harmonized data from several sites that included three samples of carefully screened youths with OCD, with other disorders, and without known disorders who completed multiple self-report questionnaires, including the 21-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV).

Utilizing psychometric analyses including factor analyses, invariance analyses, and item response theory methodologies, we were able to develop an ultrabrief measure extracted from the OCI-CV: the 5-item Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV-5). This very brief self-report measure was found to have very good psychometric properties including a sensitive and specific clinical cutoff score. Youth who score at or above the cutoff score are nearly 21 times more likely to meet criteria for OCD.

This measure corresponds to a need to rapidly screen for OCD in children in nonspecialized settings, including community mental health clinics, primary care settings, and pediatric treatment facilities. However, it is important to note it is not a diagnostic measure. The measure is intended to identify youth who should be referred to a mental health care professional to conduct a diagnostic interview.

Dr. Abramovitch is a clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist based in Austin, Tex., and an associate professor at Texas State University. Dr. Abramowitz is professor and director of clinical training in the Anxiety and Stress Lab at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. McKay is professor of psychology at Fordham University, Bronx, N.Y.

Study finds high rate of psychiatric burden in cosmetic dermatology patients

results from a large retrospective analysis showed.

“As the rate of cosmetic procedures continues to increase, it is crucial that physicians understand that many patients with a psychiatric disorder require clear communication and appropriate consultation visits,” lead study author Patricia Richey, MD, told this news organization.

While studies have displayed links between the desire for a cosmetic procedure and psychiatric stressors and disorders – most commonly mood disorders, personality disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, and addiction-like behavior – the scarce literature on the subject mostly comes from the realm of plastic surgery.

“The relationship between psychiatric disease and the motivation for dermatologic cosmetic procedures has never been fully elucidated,” said Dr. Richey, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and conducts research for the Wellman Center for Photomedicine and the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “A possible association between psychiatric disorder and the motivation for cosmetic procedures is critical to understand given increasing procedure rates and the need for clear communication and appropriate consultation visits with these patients.”

For the retrospective cohort study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Richey; Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at MGH; and Ryan W. Chapin, PharmD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reviewed the medical records of 1,000 patients from a cosmetic dermatology clinic and 1,000 patients from a medical dermatology clinic, both at MGH. Those who crossed over between the two clinics were excluded from the analysis.

Patients in the cosmetic group were significantly younger than those in the medical group (a mean of 48 vs. 56 years, respectively; P < .0001), and there was a higher percentage of women than men in both groups (78.5% vs. 21.5% in the cosmetic group and 61.4% vs. 38.6% in the medical group; P < .00001).

The researchers found that 49% of patients in the cosmetic group had been diagnosed with at least one psychiatric disorder, compared with 33% in the medical group (P < .00001), most commonly anxiety, depression, ADHD, and insomnia. In addition, 39 patients in the cosmetic group had 2 or more psychiatric disorders, compared with 22 of those in the medical group.

Similarly, 44% of patients in the cosmetic group were on a psychiatric medication, compared with 28% in the medical group (P < .00001). The average number of medications among those on more than one psychiatric medication was 1.67 among those in the cosmetic dermatology group versus 1.48 among those in the medical dermatology group (P = .020).

By drug class, a higher percentage of patients in the cosmetic group, compared with those in the medical group, were taking antidepressants (33% vs. 21%, respectively; P < .00001), anxiolytics (26% vs. 13%; P < .00001), mood stabilizers (2.80% vs. 1.10%; P = .006), and stimulants (15.2% vs. 7.20%; P < .00001). The proportion of those taking antipsychotics was essentially even in the two groups (2.50% vs. 2.70%; P = .779).

Dr. Richey and colleagues also observed that patients in the cosmetic group had significantly higher rates of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and ADHD than those in the medical group. “This finding did not particularly surprise me,” she said, since she and her colleagues recently published a study on the association of stimulant use with psychocutaneous disease.

“Stimulants are used to treat ADHD and are also known to trigger OCD-like symptoms,” she said. “I was surprised that no patients had been diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder, but we know that with increased patient access to medical records, physicians are often cautious in their documentation.”

She added that the overall results of the new study underscore the importance of consultation visits with cosmetic patients, including obtaining a full medication list and accurate medical history, if possible. “One could also consider well-studied screening tools mostly from the mood disorder realm, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire–2,” Dr. Richey said. “Much can be gained from simply talking to the patient and trying to understand him/her and underlying motivations prior to performing a procedure.”

Evan Rieder, MD, a New York City–based dermatologist and psychiatrist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the analysis as demonstrating what medical and cosmetic dermatologists have been seeing in their practices for years. “While this study is limited by its single-center retrospective nature in an academic center that may not be representative of the general population, it does demonstrate a high burden of psychopathology and psychopharmacologic treatments in aesthetic patients,” Dr. Rieder said in an interview.

“While psychiatric illness is not a contraindication to cosmetic treatment, a high percentage of patients with ADHD, OCD, and likely [body dysmorphic disorder] in cosmetic dermatology practices should give us pause.” The nature of these diseases may indicate that some people are seeking aesthetic treatments for reasons yet to be elucidated, he added.

“It certainly indicates that dermatologists should be equipped to screen for, identify, and provide such patients with the appropriate resources for psychological treatment, regardless if they are deemed appropriate candidates for cosmetic intervention,” he said.

In an interview, Pooja Sodha, MD, director of the Center for Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, noted that previous studies have demonstrated the interplay between mood disorders and dermatologic conditions for years, namely in acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and immune mediated disorders.

“In these conditions, the psychiatric stressors can worsen the skin condition and impede treatment,” Dr. Sodha said. “This study is an important segue into further elucidating our cosmetic patient population, and we should try to ask the next important question: how do we as physicians build a better rapport with these patients, understand their motivations for care, and effectively guide the patient through the consultation process to realistically address their concerns? It might help us both.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Sodha reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Rieder disclosed that he is a consultant for Allergan, Almirall, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dr. Brandt, L’Oreal, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever.

results from a large retrospective analysis showed.

“As the rate of cosmetic procedures continues to increase, it is crucial that physicians understand that many patients with a psychiatric disorder require clear communication and appropriate consultation visits,” lead study author Patricia Richey, MD, told this news organization.

While studies have displayed links between the desire for a cosmetic procedure and psychiatric stressors and disorders – most commonly mood disorders, personality disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, and addiction-like behavior – the scarce literature on the subject mostly comes from the realm of plastic surgery.

“The relationship between psychiatric disease and the motivation for dermatologic cosmetic procedures has never been fully elucidated,” said Dr. Richey, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and conducts research for the Wellman Center for Photomedicine and the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “A possible association between psychiatric disorder and the motivation for cosmetic procedures is critical to understand given increasing procedure rates and the need for clear communication and appropriate consultation visits with these patients.”

For the retrospective cohort study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Richey; Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at MGH; and Ryan W. Chapin, PharmD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reviewed the medical records of 1,000 patients from a cosmetic dermatology clinic and 1,000 patients from a medical dermatology clinic, both at MGH. Those who crossed over between the two clinics were excluded from the analysis.

Patients in the cosmetic group were significantly younger than those in the medical group (a mean of 48 vs. 56 years, respectively; P < .0001), and there was a higher percentage of women than men in both groups (78.5% vs. 21.5% in the cosmetic group and 61.4% vs. 38.6% in the medical group; P < .00001).

The researchers found that 49% of patients in the cosmetic group had been diagnosed with at least one psychiatric disorder, compared with 33% in the medical group (P < .00001), most commonly anxiety, depression, ADHD, and insomnia. In addition, 39 patients in the cosmetic group had 2 or more psychiatric disorders, compared with 22 of those in the medical group.

Similarly, 44% of patients in the cosmetic group were on a psychiatric medication, compared with 28% in the medical group (P < .00001). The average number of medications among those on more than one psychiatric medication was 1.67 among those in the cosmetic dermatology group versus 1.48 among those in the medical dermatology group (P = .020).

By drug class, a higher percentage of patients in the cosmetic group, compared with those in the medical group, were taking antidepressants (33% vs. 21%, respectively; P < .00001), anxiolytics (26% vs. 13%; P < .00001), mood stabilizers (2.80% vs. 1.10%; P = .006), and stimulants (15.2% vs. 7.20%; P < .00001). The proportion of those taking antipsychotics was essentially even in the two groups (2.50% vs. 2.70%; P = .779).

Dr. Richey and colleagues also observed that patients in the cosmetic group had significantly higher rates of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and ADHD than those in the medical group. “This finding did not particularly surprise me,” she said, since she and her colleagues recently published a study on the association of stimulant use with psychocutaneous disease.

“Stimulants are used to treat ADHD and are also known to trigger OCD-like symptoms,” she said. “I was surprised that no patients had been diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder, but we know that with increased patient access to medical records, physicians are often cautious in their documentation.”

She added that the overall results of the new study underscore the importance of consultation visits with cosmetic patients, including obtaining a full medication list and accurate medical history, if possible. “One could also consider well-studied screening tools mostly from the mood disorder realm, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire–2,” Dr. Richey said. “Much can be gained from simply talking to the patient and trying to understand him/her and underlying motivations prior to performing a procedure.”

Evan Rieder, MD, a New York City–based dermatologist and psychiatrist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the analysis as demonstrating what medical and cosmetic dermatologists have been seeing in their practices for years. “While this study is limited by its single-center retrospective nature in an academic center that may not be representative of the general population, it does demonstrate a high burden of psychopathology and psychopharmacologic treatments in aesthetic patients,” Dr. Rieder said in an interview.

“While psychiatric illness is not a contraindication to cosmetic treatment, a high percentage of patients with ADHD, OCD, and likely [body dysmorphic disorder] in cosmetic dermatology practices should give us pause.” The nature of these diseases may indicate that some people are seeking aesthetic treatments for reasons yet to be elucidated, he added.

“It certainly indicates that dermatologists should be equipped to screen for, identify, and provide such patients with the appropriate resources for psychological treatment, regardless if they are deemed appropriate candidates for cosmetic intervention,” he said.

In an interview, Pooja Sodha, MD, director of the Center for Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, noted that previous studies have demonstrated the interplay between mood disorders and dermatologic conditions for years, namely in acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and immune mediated disorders.

“In these conditions, the psychiatric stressors can worsen the skin condition and impede treatment,” Dr. Sodha said. “This study is an important segue into further elucidating our cosmetic patient population, and we should try to ask the next important question: how do we as physicians build a better rapport with these patients, understand their motivations for care, and effectively guide the patient through the consultation process to realistically address their concerns? It might help us both.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Sodha reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Rieder disclosed that he is a consultant for Allergan, Almirall, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dr. Brandt, L’Oreal, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever.

results from a large retrospective analysis showed.

“As the rate of cosmetic procedures continues to increase, it is crucial that physicians understand that many patients with a psychiatric disorder require clear communication and appropriate consultation visits,” lead study author Patricia Richey, MD, told this news organization.

While studies have displayed links between the desire for a cosmetic procedure and psychiatric stressors and disorders – most commonly mood disorders, personality disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, and addiction-like behavior – the scarce literature on the subject mostly comes from the realm of plastic surgery.

“The relationship between psychiatric disease and the motivation for dermatologic cosmetic procedures has never been fully elucidated,” said Dr. Richey, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and conducts research for the Wellman Center for Photomedicine and the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “A possible association between psychiatric disorder and the motivation for cosmetic procedures is critical to understand given increasing procedure rates and the need for clear communication and appropriate consultation visits with these patients.”

For the retrospective cohort study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Richey; Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center at MGH; and Ryan W. Chapin, PharmD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reviewed the medical records of 1,000 patients from a cosmetic dermatology clinic and 1,000 patients from a medical dermatology clinic, both at MGH. Those who crossed over between the two clinics were excluded from the analysis.

Patients in the cosmetic group were significantly younger than those in the medical group (a mean of 48 vs. 56 years, respectively; P < .0001), and there was a higher percentage of women than men in both groups (78.5% vs. 21.5% in the cosmetic group and 61.4% vs. 38.6% in the medical group; P < .00001).

The researchers found that 49% of patients in the cosmetic group had been diagnosed with at least one psychiatric disorder, compared with 33% in the medical group (P < .00001), most commonly anxiety, depression, ADHD, and insomnia. In addition, 39 patients in the cosmetic group had 2 or more psychiatric disorders, compared with 22 of those in the medical group.

Similarly, 44% of patients in the cosmetic group were on a psychiatric medication, compared with 28% in the medical group (P < .00001). The average number of medications among those on more than one psychiatric medication was 1.67 among those in the cosmetic dermatology group versus 1.48 among those in the medical dermatology group (P = .020).

By drug class, a higher percentage of patients in the cosmetic group, compared with those in the medical group, were taking antidepressants (33% vs. 21%, respectively; P < .00001), anxiolytics (26% vs. 13%; P < .00001), mood stabilizers (2.80% vs. 1.10%; P = .006), and stimulants (15.2% vs. 7.20%; P < .00001). The proportion of those taking antipsychotics was essentially even in the two groups (2.50% vs. 2.70%; P = .779).

Dr. Richey and colleagues also observed that patients in the cosmetic group had significantly higher rates of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and ADHD than those in the medical group. “This finding did not particularly surprise me,” she said, since she and her colleagues recently published a study on the association of stimulant use with psychocutaneous disease.

“Stimulants are used to treat ADHD and are also known to trigger OCD-like symptoms,” she said. “I was surprised that no patients had been diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder, but we know that with increased patient access to medical records, physicians are often cautious in their documentation.”

She added that the overall results of the new study underscore the importance of consultation visits with cosmetic patients, including obtaining a full medication list and accurate medical history, if possible. “One could also consider well-studied screening tools mostly from the mood disorder realm, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire–2,” Dr. Richey said. “Much can be gained from simply talking to the patient and trying to understand him/her and underlying motivations prior to performing a procedure.”

Evan Rieder, MD, a New York City–based dermatologist and psychiatrist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the analysis as demonstrating what medical and cosmetic dermatologists have been seeing in their practices for years. “While this study is limited by its single-center retrospective nature in an academic center that may not be representative of the general population, it does demonstrate a high burden of psychopathology and psychopharmacologic treatments in aesthetic patients,” Dr. Rieder said in an interview.

“While psychiatric illness is not a contraindication to cosmetic treatment, a high percentage of patients with ADHD, OCD, and likely [body dysmorphic disorder] in cosmetic dermatology practices should give us pause.” The nature of these diseases may indicate that some people are seeking aesthetic treatments for reasons yet to be elucidated, he added.

“It certainly indicates that dermatologists should be equipped to screen for, identify, and provide such patients with the appropriate resources for psychological treatment, regardless if they are deemed appropriate candidates for cosmetic intervention,” he said.

In an interview, Pooja Sodha, MD, director of the Center for Laser and Cosmetic Dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, noted that previous studies have demonstrated the interplay between mood disorders and dermatologic conditions for years, namely in acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and immune mediated disorders.

“In these conditions, the psychiatric stressors can worsen the skin condition and impede treatment,” Dr. Sodha said. “This study is an important segue into further elucidating our cosmetic patient population, and we should try to ask the next important question: how do we as physicians build a better rapport with these patients, understand their motivations for care, and effectively guide the patient through the consultation process to realistically address their concerns? It might help us both.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Sodha reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Rieder disclosed that he is a consultant for Allergan, Almirall, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dr. Brandt, L’Oreal, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Clinical psychoeconomics: Accounting for money matters in psychiatric assessment and treatment

Despite money’s central role in our psychic lives, many trainees – and some seasoned practitioners – skirt around financial issues. Some clinicians confess that inquiring about patients’ finances feels “too personal.” They fear that asking about money could suggest that the clinician is primarily concerned with getting paid. Some clinicians feel that looking into patients’ finances might be unprofessional, outside one’s scope of practice. But it is not.

Trainees often receive little guidance concerning money matters in patients’ lives and treatments, considerations we have labeled clinical psychoeconomics. Considerable evidence suggests that financial concerns often provoke emotional distress and dysfunctional behaviors, and directly influence patient’s health care decisions. Financial issues also influence how clinicians view and react to patients.

We have recently reviewed (and illustrated through case vignettes) how money matters might impact psychiatric assessment, case formulation, treatment planning, and ongoing psychiatric treatments including psychotherapies.1 Consider how money affects people’s lives: Money helps people meet multiple practical, psychological, and social needs by enabling them to obtain food, clothing, shelter, other material goods, services, discretionary time, and opportunities. And money strongly influences relationships. Regardless of poverty or wealth, thoughts and behaviors connected to acquiring, possessing, and disposing of money, and feelings accompanying these processes such as greed, neediness, envy, pride, shame, guilt, and self-satisfaction often underly intrapsychic and interpersonal conflicts.

Individuals constantly engage in numerous simultaneous conscious, preconscious, and unconscious neuro-economic trade-offs that determine goals, efforts, and timing. Many are financially influenced. Money influences how virtually all patients seek, receive, and sustain their mental health care including psychotherapy.

Money problems can be associated with insecurity, impotence, feeling unloved, and lack of freedom or subjugation. Individuals may resent how they’re forced to acquire money, and feel shamed or morally injured by their jobs, financial dependence on other family members, public assistance, or their questionable ways of obtaining money.

Impoverished individuals may face choosing between food, housing, medications, and medical care. Domestically abused individuals may reluctantly remain with their abusers, risking physical harm or death rather than face destitution. Some families tolerate severely disabled individuals at home because they rely on their disability checks and caregiver payments. Suicides may turn on how individuals forecast financial repercussions affecting their families. Desires to avoid debt may lead to treatment avoidance.

Individuals with enough money to get by face daily financially related choices involving competing needs, desires, values, and loyalties. They may experience conflicts concerning spending on necessities vs. indulgences or spending on oneself vs. significant others.

Whereas some wealthy individuals may assume unwarranted airs of superiority and entitlement, others may feel guilty about wealth, or fearful that others like them only for their money. Individuals on the receiving end of wealth may feel emotionally and behaviorally manipulated by their benefactors.

Assessment

Assessments should consider how financial matters have shaped patients’ early psychological development as well their current lives. How do patients’ emotions, thoughts, and behaviors reflect money matters? What money-related pathologies are evident? What aspects of the patient’s “financial world” seem modifiable?

Financial questions should be posed colloquially. Screeners include: “Where do you live?”, “Who’s in the home?”, “How do you (all) manage financially?”, “What do you all do for a living?”, “How do you make ends meet?”, and “What financial problems are you facing?” Clinicians can quickly learn about patients’ financial self-sufficiencies, individuals for whom they bear financial responsibility, and others they rely on for support, for example, relatives. If patients avoid answering such questions forthrightly, particularly when financial arrangements are “complicated,” clinicians will want to revisit these issues later after establishing a firmer alliance but continue to wonder about the meaning of the patient’s reluctance.

When explicit, patients, families, and couples are fully aware of the conflicts but have difficulty resolving financial disputes. When conflicts are implicit, money problems may be unacknowledged, avoided, denied, or minimized. Conflicts concerning money are often transmitted trans-generationally.

Psychopathological conditions unequivocally linked to money include compulsive shopping, gambling disorders, miserly hoarding, impulse buying, and spending sprees during hypomanic and manic states. Mounting debts may create progressively insurmountable sources of distress. Money can be weaponized to sadistically create enticement, envy, or deprivation. Some monetarily antisocial individuals compromise interpersonal relationships as well as treatments. Individuals with alcohol/substance use disorders may spend so much on substances that little is left for necessities. Financially needy individuals may engage in morally questionable behaviors they might otherwise shun.

Case formulation and treatment planning

Incorporating money matters into case formulations entails demonstrating how financial concerns influenced maladaptive development and distort current attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors.

Concurrently, clinicians should acknowledge patients’ reality-based fiscal decisions, appreciating cultural and family value differences concerning how money should be acquired and spent. Since money often determines frequency and duration of treatment visits, clinicians are ethically obligated to discuss with patients what they might expect from different medications and psychotherapies, and their comparative costs.

Money matters’ impact on psychotherapies

Money matters often affect transference and countertransference reactions. Some reactions stem from how patients and clinicians compare their own financial situations with those of the other.

To help identify and ameliorate money-related countertransference responses, clinicians can reflect on questions such as: “How comfortable are you with people who are much poorer or richer than you are?” “How comfortable are you with impoverished individuals or with multimillionaires or their children?” And “why?” For trainees, all these reactions should be discussed in supervision.

Conclusions

To summarize, four clinical psychoeconomic issues should be routinely assessed and factored into psychiatric case formulations and treatment plans: how financial issues 1) have impacted patients’ psychological development; 2) impact patients’ current lives; 3) are likely to impact access, type, intensity, and duration of treatment visits; and 4) might provoke money-related transference and countertransference concerns.

In advising patients about treatment options, clinicians should discuss each treatment’s relative effectiveness and estimated costs of care. Patients’ decisions will likely be heavily influenced by financial considerations.

Dr. Yager is based in the department of psychiatry, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Kay is based in the department of psychiatry, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio. No external funds were received for this project, and the authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Reference

1. Yager J and Kay J. Money matters in psychiatric assessment, case formulation, treatment planning, and ongoing psychotherapy: Clinical psychoeconomics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2022 Jun 10. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001552.

Despite money’s central role in our psychic lives, many trainees – and some seasoned practitioners – skirt around financial issues. Some clinicians confess that inquiring about patients’ finances feels “too personal.” They fear that asking about money could suggest that the clinician is primarily concerned with getting paid. Some clinicians feel that looking into patients’ finances might be unprofessional, outside one’s scope of practice. But it is not.

Trainees often receive little guidance concerning money matters in patients’ lives and treatments, considerations we have labeled clinical psychoeconomics. Considerable evidence suggests that financial concerns often provoke emotional distress and dysfunctional behaviors, and directly influence patient’s health care decisions. Financial issues also influence how clinicians view and react to patients.

We have recently reviewed (and illustrated through case vignettes) how money matters might impact psychiatric assessment, case formulation, treatment planning, and ongoing psychiatric treatments including psychotherapies.1 Consider how money affects people’s lives: Money helps people meet multiple practical, psychological, and social needs by enabling them to obtain food, clothing, shelter, other material goods, services, discretionary time, and opportunities. And money strongly influences relationships. Regardless of poverty or wealth, thoughts and behaviors connected to acquiring, possessing, and disposing of money, and feelings accompanying these processes such as greed, neediness, envy, pride, shame, guilt, and self-satisfaction often underly intrapsychic and interpersonal conflicts.

Individuals constantly engage in numerous simultaneous conscious, preconscious, and unconscious neuro-economic trade-offs that determine goals, efforts, and timing. Many are financially influenced. Money influences how virtually all patients seek, receive, and sustain their mental health care including psychotherapy.

Money problems can be associated with insecurity, impotence, feeling unloved, and lack of freedom or subjugation. Individuals may resent how they’re forced to acquire money, and feel shamed or morally injured by their jobs, financial dependence on other family members, public assistance, or their questionable ways of obtaining money.

Impoverished individuals may face choosing between food, housing, medications, and medical care. Domestically abused individuals may reluctantly remain with their abusers, risking physical harm or death rather than face destitution. Some families tolerate severely disabled individuals at home because they rely on their disability checks and caregiver payments. Suicides may turn on how individuals forecast financial repercussions affecting their families. Desires to avoid debt may lead to treatment avoidance.

Individuals with enough money to get by face daily financially related choices involving competing needs, desires, values, and loyalties. They may experience conflicts concerning spending on necessities vs. indulgences or spending on oneself vs. significant others.

Whereas some wealthy individuals may assume unwarranted airs of superiority and entitlement, others may feel guilty about wealth, or fearful that others like them only for their money. Individuals on the receiving end of wealth may feel emotionally and behaviorally manipulated by their benefactors.

Assessment

Assessments should consider how financial matters have shaped patients’ early psychological development as well their current lives. How do patients’ emotions, thoughts, and behaviors reflect money matters? What money-related pathologies are evident? What aspects of the patient’s “financial world” seem modifiable?

Financial questions should be posed colloquially. Screeners include: “Where do you live?”, “Who’s in the home?”, “How do you (all) manage financially?”, “What do you all do for a living?”, “How do you make ends meet?”, and “What financial problems are you facing?” Clinicians can quickly learn about patients’ financial self-sufficiencies, individuals for whom they bear financial responsibility, and others they rely on for support, for example, relatives. If patients avoid answering such questions forthrightly, particularly when financial arrangements are “complicated,” clinicians will want to revisit these issues later after establishing a firmer alliance but continue to wonder about the meaning of the patient’s reluctance.

When explicit, patients, families, and couples are fully aware of the conflicts but have difficulty resolving financial disputes. When conflicts are implicit, money problems may be unacknowledged, avoided, denied, or minimized. Conflicts concerning money are often transmitted trans-generationally.

Psychopathological conditions unequivocally linked to money include compulsive shopping, gambling disorders, miserly hoarding, impulse buying, and spending sprees during hypomanic and manic states. Mounting debts may create progressively insurmountable sources of distress. Money can be weaponized to sadistically create enticement, envy, or deprivation. Some monetarily antisocial individuals compromise interpersonal relationships as well as treatments. Individuals with alcohol/substance use disorders may spend so much on substances that little is left for necessities. Financially needy individuals may engage in morally questionable behaviors they might otherwise shun.

Case formulation and treatment planning

Incorporating money matters into case formulations entails demonstrating how financial concerns influenced maladaptive development and distort current attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors.

Concurrently, clinicians should acknowledge patients’ reality-based fiscal decisions, appreciating cultural and family value differences concerning how money should be acquired and spent. Since money often determines frequency and duration of treatment visits, clinicians are ethically obligated to discuss with patients what they might expect from different medications and psychotherapies, and their comparative costs.

Money matters’ impact on psychotherapies

Money matters often affect transference and countertransference reactions. Some reactions stem from how patients and clinicians compare their own financial situations with those of the other.

To help identify and ameliorate money-related countertransference responses, clinicians can reflect on questions such as: “How comfortable are you with people who are much poorer or richer than you are?” “How comfortable are you with impoverished individuals or with multimillionaires or their children?” And “why?” For trainees, all these reactions should be discussed in supervision.

Conclusions

To summarize, four clinical psychoeconomic issues should be routinely assessed and factored into psychiatric case formulations and treatment plans: how financial issues 1) have impacted patients’ psychological development; 2) impact patients’ current lives; 3) are likely to impact access, type, intensity, and duration of treatment visits; and 4) might provoke money-related transference and countertransference concerns.

In advising patients about treatment options, clinicians should discuss each treatment’s relative effectiveness and estimated costs of care. Patients’ decisions will likely be heavily influenced by financial considerations.

Dr. Yager is based in the department of psychiatry, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Kay is based in the department of psychiatry, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio. No external funds were received for this project, and the authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Reference