User login

Total margin control surgery warranted for high-risk keratinocyte carcinomas

MILAN – A recent meta-analysis found that total margin control surgery substantially cut the risk of recurrence in patients with high-risk keratinocyte carcinomas, Chrysalyne Schmults, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

While standard excision will cure the vast majority of low-risk basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), those classified as high risk are best treated with the advanced surgical procedure, also referred to as circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA), said Dr. Schmults, director of the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

For high-risk cases, CCPDMA has superior outcomes, compared with standard excision, according to results of the meta-analysis conducted by Dr. Schmults and colleagues. The meta-analysis has not yet been published.

The in the meta-analysis of medical literature from 1993 to 2017.

“This is a really big drop,” Dr. Schmults said. “If you do total margin control surgery on your perineural invasive cases, you’re going to drop your recurrence rate by two-thirds, and that’s a really big difference.”

For carcinomas without perineural invasion, the recurrence rate is about 4.5% for standard excision and about 2.0% for CCPDMA, the analysis showed. “That’s a difference, but it’s not a big enough difference that we’re going to start doing total margin control surgery on every single basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma that comes to us,” Dr. Schmults commented.

Using techniques such as Mohs surgery that allow for CCPDMA, nearly 100% of the surgical margin can be seen; by contrast, standard histology allows for visualization of only about 1% of the marginal surface, according to Dr. Schmults.

While CCPDMA may have superior outcomes for high-risk keratinocyte carcinomas, defining what constitutes high risk remains a challenge, particularly for patients with BCCs. “We don’t have good literature on which are the rare, bad basal cells,” she said.

But more clarity may be on the way. In a paper under review for publication on Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) staging criteria for BCC, Dr. Schmults and colleagues describe a subset of patients with BCC at higher risk of metastasis and death based on specific high-risk tumor characteristics.

High risk is better defined for SCCs. According to the BWH classification system for cutaneous SCCs, developed by Dr. Schmults and colleagues, high-risk features include larger tumor diameter, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion, and tumor invasion beyond subcutaneous fat or to bone.

Patients with SCC classified as high stage by the BWH system have about a 25% risk of metastasis or death. “These patients really need that total margin control surgery,” Dr. Schmults said.

High-stage SCC patients who did not get Mohs surgery in a study (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:327-34) conducted by Dr. Schmults and her associates, had a quadrupling in risk of death from disease, compared with those who did get the procedure in a more recent study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Mar;80[3]:633-8).

“These are fairly small studies,” she pointed out. But the large meta-analysis she presented at the meeting showed the same result, “that the higher the stage, the worse your tumor is, and whether it’s basal cell or squamous cell, the greater the advantage for total margin control surgery.”

Dr. Schmults reported that she is the panel chair for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines on nonmelanoma skin cancer, and that she was a cutaneous SCC committee member for the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer cancer staging system. She also participated in the development of the BWH staging system for SCC.

MILAN – A recent meta-analysis found that total margin control surgery substantially cut the risk of recurrence in patients with high-risk keratinocyte carcinomas, Chrysalyne Schmults, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

While standard excision will cure the vast majority of low-risk basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), those classified as high risk are best treated with the advanced surgical procedure, also referred to as circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA), said Dr. Schmults, director of the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

For high-risk cases, CCPDMA has superior outcomes, compared with standard excision, according to results of the meta-analysis conducted by Dr. Schmults and colleagues. The meta-analysis has not yet been published.

The in the meta-analysis of medical literature from 1993 to 2017.

“This is a really big drop,” Dr. Schmults said. “If you do total margin control surgery on your perineural invasive cases, you’re going to drop your recurrence rate by two-thirds, and that’s a really big difference.”

For carcinomas without perineural invasion, the recurrence rate is about 4.5% for standard excision and about 2.0% for CCPDMA, the analysis showed. “That’s a difference, but it’s not a big enough difference that we’re going to start doing total margin control surgery on every single basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma that comes to us,” Dr. Schmults commented.

Using techniques such as Mohs surgery that allow for CCPDMA, nearly 100% of the surgical margin can be seen; by contrast, standard histology allows for visualization of only about 1% of the marginal surface, according to Dr. Schmults.

While CCPDMA may have superior outcomes for high-risk keratinocyte carcinomas, defining what constitutes high risk remains a challenge, particularly for patients with BCCs. “We don’t have good literature on which are the rare, bad basal cells,” she said.

But more clarity may be on the way. In a paper under review for publication on Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) staging criteria for BCC, Dr. Schmults and colleagues describe a subset of patients with BCC at higher risk of metastasis and death based on specific high-risk tumor characteristics.

High risk is better defined for SCCs. According to the BWH classification system for cutaneous SCCs, developed by Dr. Schmults and colleagues, high-risk features include larger tumor diameter, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion, and tumor invasion beyond subcutaneous fat or to bone.

Patients with SCC classified as high stage by the BWH system have about a 25% risk of metastasis or death. “These patients really need that total margin control surgery,” Dr. Schmults said.

High-stage SCC patients who did not get Mohs surgery in a study (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:327-34) conducted by Dr. Schmults and her associates, had a quadrupling in risk of death from disease, compared with those who did get the procedure in a more recent study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Mar;80[3]:633-8).

“These are fairly small studies,” she pointed out. But the large meta-analysis she presented at the meeting showed the same result, “that the higher the stage, the worse your tumor is, and whether it’s basal cell or squamous cell, the greater the advantage for total margin control surgery.”

Dr. Schmults reported that she is the panel chair for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines on nonmelanoma skin cancer, and that she was a cutaneous SCC committee member for the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer cancer staging system. She also participated in the development of the BWH staging system for SCC.

MILAN – A recent meta-analysis found that total margin control surgery substantially cut the risk of recurrence in patients with high-risk keratinocyte carcinomas, Chrysalyne Schmults, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

While standard excision will cure the vast majority of low-risk basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), those classified as high risk are best treated with the advanced surgical procedure, also referred to as circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA), said Dr. Schmults, director of the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

For high-risk cases, CCPDMA has superior outcomes, compared with standard excision, according to results of the meta-analysis conducted by Dr. Schmults and colleagues. The meta-analysis has not yet been published.

The in the meta-analysis of medical literature from 1993 to 2017.

“This is a really big drop,” Dr. Schmults said. “If you do total margin control surgery on your perineural invasive cases, you’re going to drop your recurrence rate by two-thirds, and that’s a really big difference.”

For carcinomas without perineural invasion, the recurrence rate is about 4.5% for standard excision and about 2.0% for CCPDMA, the analysis showed. “That’s a difference, but it’s not a big enough difference that we’re going to start doing total margin control surgery on every single basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma that comes to us,” Dr. Schmults commented.

Using techniques such as Mohs surgery that allow for CCPDMA, nearly 100% of the surgical margin can be seen; by contrast, standard histology allows for visualization of only about 1% of the marginal surface, according to Dr. Schmults.

While CCPDMA may have superior outcomes for high-risk keratinocyte carcinomas, defining what constitutes high risk remains a challenge, particularly for patients with BCCs. “We don’t have good literature on which are the rare, bad basal cells,” she said.

But more clarity may be on the way. In a paper under review for publication on Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) staging criteria for BCC, Dr. Schmults and colleagues describe a subset of patients with BCC at higher risk of metastasis and death based on specific high-risk tumor characteristics.

High risk is better defined for SCCs. According to the BWH classification system for cutaneous SCCs, developed by Dr. Schmults and colleagues, high-risk features include larger tumor diameter, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion, and tumor invasion beyond subcutaneous fat or to bone.

Patients with SCC classified as high stage by the BWH system have about a 25% risk of metastasis or death. “These patients really need that total margin control surgery,” Dr. Schmults said.

High-stage SCC patients who did not get Mohs surgery in a study (J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32[4]:327-34) conducted by Dr. Schmults and her associates, had a quadrupling in risk of death from disease, compared with those who did get the procedure in a more recent study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Mar;80[3]:633-8).

“These are fairly small studies,” she pointed out. But the large meta-analysis she presented at the meeting showed the same result, “that the higher the stage, the worse your tumor is, and whether it’s basal cell or squamous cell, the greater the advantage for total margin control surgery.”

Dr. Schmults reported that she is the panel chair for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines on nonmelanoma skin cancer, and that she was a cutaneous SCC committee member for the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer cancer staging system. She also participated in the development of the BWH staging system for SCC.

REPORTING FROM WCD2019

Response endures in cemiplimab-treated patients with cutaneous SCC

MILAN – In an updated analysis of a pivotal phase 2 study, Michael R. Migden, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Median duration of response was not reached at the time of the analysis, with probability of no progression or death above 80% at the 20-month mark, according to Dr. Migden, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

The safety profile of cemiplimab in this study was comparable with what has been reported for other anti–programmed death agents, he said in an oral presentation at the meeting.

While the median time to response was less than 2 months, about one-fifth of patients with locally advanced disease had “unconventional” late responses, occurring up to 10 months after starting treatment, Dr. Migden said. “If you’re just putting someone on some agent like this for a few months, and say, ‘well, I don’t see anything improving,’ it could be one of these patients in this 20% that deserve a little bit longer therapy.”

Cemiplimab (Libtayo) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for patients with locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) who are not suitable for curative surgery or radiation, Dr. Migden said in his presentation. That approval was based in part on previously reported results from the phase 2 study, known as EMPOWER-CSCC-1, which demonstrated that cemiplimab had substantial antitumor activity and durable responses.

In this update on EMPOWER-CSCC-1, Dr. Migden described results for 78 patients with locally advanced CSCC and 59 with metastatic CSCC who received weight-based intravenous cemiplimab for up to 96 weeks, with optional retreatment for those who had disease progression during the follow-up period. This was an older population, with a mean age of 72 years, and more than 80% were male. About one-third had prior systemic therapy, and the majority had prior cancer-related radiotherapy and surgery.

The objective response rate was 43.6% in the locally advanced group and 49.2% in the metastatic group; this numerical difference of less than 3 percentage points was not statistically significant, according to Dr. Migden.

More importantly, he said, the disease control rate (responses, stable disease, and noncomplete response/nonprogressive disease) was 79.5% in the locally advanced group and 71.2% in the metastatic group.

Time to response was “quite rapid” at a median of 1.9 months in both groups, though 7 of the 34 responders in the locally advanced group had unconventional late responses, taking 6-10 months to get to the point of response, Dr. Migden said.

The probability of being event free (such as no progression or death) has remained relatively flat, he added. In the metastatic cohort, event-free probability was 96.4% at 6 months, 88.9% at 12 months, and 82.5% at 20 months, with a 16.5-month median duration of follow-up, while in the locally advanced cohort, the event-free probability was 96.2% at 6 months, 87.8% at both 12 months and 20 months, with a median follow-up of 9.3 months.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported for 28.5% in these patients, though Dr. Migden noted that treatment emergent does not necessarily mean related to the study drug. Immune-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater were seen in 11.7% of patients, and adverse events leading to discontinuation were reported for 8.8%.

Dr. Migden reported disclosures related to Regeneron, Novartis, Genentech, Eli Lilly, and Sun Pharmaceutical.

MILAN – In an updated analysis of a pivotal phase 2 study, Michael R. Migden, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Median duration of response was not reached at the time of the analysis, with probability of no progression or death above 80% at the 20-month mark, according to Dr. Migden, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

The safety profile of cemiplimab in this study was comparable with what has been reported for other anti–programmed death agents, he said in an oral presentation at the meeting.

While the median time to response was less than 2 months, about one-fifth of patients with locally advanced disease had “unconventional” late responses, occurring up to 10 months after starting treatment, Dr. Migden said. “If you’re just putting someone on some agent like this for a few months, and say, ‘well, I don’t see anything improving,’ it could be one of these patients in this 20% that deserve a little bit longer therapy.”

Cemiplimab (Libtayo) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for patients with locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) who are not suitable for curative surgery or radiation, Dr. Migden said in his presentation. That approval was based in part on previously reported results from the phase 2 study, known as EMPOWER-CSCC-1, which demonstrated that cemiplimab had substantial antitumor activity and durable responses.

In this update on EMPOWER-CSCC-1, Dr. Migden described results for 78 patients with locally advanced CSCC and 59 with metastatic CSCC who received weight-based intravenous cemiplimab for up to 96 weeks, with optional retreatment for those who had disease progression during the follow-up period. This was an older population, with a mean age of 72 years, and more than 80% were male. About one-third had prior systemic therapy, and the majority had prior cancer-related radiotherapy and surgery.

The objective response rate was 43.6% in the locally advanced group and 49.2% in the metastatic group; this numerical difference of less than 3 percentage points was not statistically significant, according to Dr. Migden.

More importantly, he said, the disease control rate (responses, stable disease, and noncomplete response/nonprogressive disease) was 79.5% in the locally advanced group and 71.2% in the metastatic group.

Time to response was “quite rapid” at a median of 1.9 months in both groups, though 7 of the 34 responders in the locally advanced group had unconventional late responses, taking 6-10 months to get to the point of response, Dr. Migden said.

The probability of being event free (such as no progression or death) has remained relatively flat, he added. In the metastatic cohort, event-free probability was 96.4% at 6 months, 88.9% at 12 months, and 82.5% at 20 months, with a 16.5-month median duration of follow-up, while in the locally advanced cohort, the event-free probability was 96.2% at 6 months, 87.8% at both 12 months and 20 months, with a median follow-up of 9.3 months.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported for 28.5% in these patients, though Dr. Migden noted that treatment emergent does not necessarily mean related to the study drug. Immune-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater were seen in 11.7% of patients, and adverse events leading to discontinuation were reported for 8.8%.

Dr. Migden reported disclosures related to Regeneron, Novartis, Genentech, Eli Lilly, and Sun Pharmaceutical.

MILAN – In an updated analysis of a pivotal phase 2 study, Michael R. Migden, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Median duration of response was not reached at the time of the analysis, with probability of no progression or death above 80% at the 20-month mark, according to Dr. Migden, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

The safety profile of cemiplimab in this study was comparable with what has been reported for other anti–programmed death agents, he said in an oral presentation at the meeting.

While the median time to response was less than 2 months, about one-fifth of patients with locally advanced disease had “unconventional” late responses, occurring up to 10 months after starting treatment, Dr. Migden said. “If you’re just putting someone on some agent like this for a few months, and say, ‘well, I don’t see anything improving,’ it could be one of these patients in this 20% that deserve a little bit longer therapy.”

Cemiplimab (Libtayo) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for patients with locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) who are not suitable for curative surgery or radiation, Dr. Migden said in his presentation. That approval was based in part on previously reported results from the phase 2 study, known as EMPOWER-CSCC-1, which demonstrated that cemiplimab had substantial antitumor activity and durable responses.

In this update on EMPOWER-CSCC-1, Dr. Migden described results for 78 patients with locally advanced CSCC and 59 with metastatic CSCC who received weight-based intravenous cemiplimab for up to 96 weeks, with optional retreatment for those who had disease progression during the follow-up period. This was an older population, with a mean age of 72 years, and more than 80% were male. About one-third had prior systemic therapy, and the majority had prior cancer-related radiotherapy and surgery.

The objective response rate was 43.6% in the locally advanced group and 49.2% in the metastatic group; this numerical difference of less than 3 percentage points was not statistically significant, according to Dr. Migden.

More importantly, he said, the disease control rate (responses, stable disease, and noncomplete response/nonprogressive disease) was 79.5% in the locally advanced group and 71.2% in the metastatic group.

Time to response was “quite rapid” at a median of 1.9 months in both groups, though 7 of the 34 responders in the locally advanced group had unconventional late responses, taking 6-10 months to get to the point of response, Dr. Migden said.

The probability of being event free (such as no progression or death) has remained relatively flat, he added. In the metastatic cohort, event-free probability was 96.4% at 6 months, 88.9% at 12 months, and 82.5% at 20 months, with a 16.5-month median duration of follow-up, while in the locally advanced cohort, the event-free probability was 96.2% at 6 months, 87.8% at both 12 months and 20 months, with a median follow-up of 9.3 months.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported for 28.5% in these patients, though Dr. Migden noted that treatment emergent does not necessarily mean related to the study drug. Immune-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater were seen in 11.7% of patients, and adverse events leading to discontinuation were reported for 8.8%.

Dr. Migden reported disclosures related to Regeneron, Novartis, Genentech, Eli Lilly, and Sun Pharmaceutical.

REPORTING FROM WCD2019

Advanced basal cell carcinoma responds to pembrolizumab in proof-of-concept study

MILAN – A checkpoint inhibitor given with or without targeted therapy resulted in robust response rates in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma, according to an investigator in a recent proof-of-concept study.

The side effect profile for the progressive death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda), plus or minus the hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (Erivedge), was “not out of range” with what’s been observed in other cancer types, said Anne Lynn S. Chang, MD, a medical dermatologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Taken together, these safety and efficacy results suggest pembrolizumab could prove useful for patients with advanced basal cell carcinomas, Dr. Chang said in an oral presentation at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Unexpectedly, dual therapy with pembrolizumab and vismodegib was not clearly superior to pembrolizumab alone, though the two arms are not directly comparable in this nonrandomized, investigator-initiated study, according to Dr. Chang.

“That was a surprise for us, but this is a subjective and a small study,” she told attendees at the conference.

There is currently a multi-institutional clinical trial underway to evaluate another PD-1 inhibitor, cemiplimab, in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma previously treated with a hedgehog pathway inhibitor, she said.

While a large fraction of basal cell carcinomas are cured by resection, those that are locally advanced or metastatic to lymph nodes or distant organs are challenging to manage. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors, which include vismodegib and sonidegib, are the only Food and Drug Administration–approved drug class in this setting, but more than half of patients do not have a response to treatment, and another 20% or so will initially respond but develop resistance, Dr. Chang said.

Other treatments that have been tried in advanced basal cell carcinomas include taxanes, platinum-based agents, 5-fluorouracil, and everolimus, but their efficacy is unclear, according to Dr. Chang, because of a lack of systematic studies.

Investigators thought PD-1 inhibitors might be promising in basal cell carcinoma for a few reasons, Dr. Chang said. In particular, PD-1 inhibitor treatment response has been linked to mutational burden and PD–ligand 1 expression, and advanced basal cell carcinomas have the largest mutational burden of all human cancers, a large proportion of which express PD-L1.

There are multiple case reports in the literature suggesting that advanced basal cell carcinoma is responsive to PD-1 inhibitors, she added.

In the study, nine patients received 200 mg infusion of pembrolizumab every 3 weeks, and seven received the pembrolizumab infusions plus oral vismodegib 150 mg per day.

The pembrolizumab monotherapy group included patients who had tumor progression on vismodegib, did not tolerate vismodegib, or had contraindications to vismodegib. The pembrolizumab-vismodegib regimen was used in patients who had prior stable or partial responses to hedgehog pathway inhibitors.

The overall response rate was 38%, or 6 of 16 patients, with a 70% probability of 1-year progression-free survival and 94% probability of 1-year overall survival, Dr. Chang reported.

The results did not make the case that pembrolizumab and vismodegib was superior to pembrolizumab alone, though as Dr. Chang noted, the numbers of patients were small. Response rates were 29% (two of seven patients) in the combination arm and 44% (four of nine patients) in the monotherapy arm.

There were 24 immune-related adverse events in the trial; the most serious was hyponatremia, which was reversible, according to Dr. Chang. The overall rates of grade 3-4 adverse events were 22% for pembrolizumab monotherapy and 17% for dual therapy.

A report on the study has also been published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Funding for the study was provided by Merck. Dr. Chang reported serving as a clinical investigator and advisory board member for studies sponsored by Genentech-Roche, Merck, Novartis, and Regeneron.

MILAN – A checkpoint inhibitor given with or without targeted therapy resulted in robust response rates in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma, according to an investigator in a recent proof-of-concept study.

The side effect profile for the progressive death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda), plus or minus the hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (Erivedge), was “not out of range” with what’s been observed in other cancer types, said Anne Lynn S. Chang, MD, a medical dermatologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Taken together, these safety and efficacy results suggest pembrolizumab could prove useful for patients with advanced basal cell carcinomas, Dr. Chang said in an oral presentation at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Unexpectedly, dual therapy with pembrolizumab and vismodegib was not clearly superior to pembrolizumab alone, though the two arms are not directly comparable in this nonrandomized, investigator-initiated study, according to Dr. Chang.

“That was a surprise for us, but this is a subjective and a small study,” she told attendees at the conference.

There is currently a multi-institutional clinical trial underway to evaluate another PD-1 inhibitor, cemiplimab, in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma previously treated with a hedgehog pathway inhibitor, she said.

While a large fraction of basal cell carcinomas are cured by resection, those that are locally advanced or metastatic to lymph nodes or distant organs are challenging to manage. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors, which include vismodegib and sonidegib, are the only Food and Drug Administration–approved drug class in this setting, but more than half of patients do not have a response to treatment, and another 20% or so will initially respond but develop resistance, Dr. Chang said.

Other treatments that have been tried in advanced basal cell carcinomas include taxanes, platinum-based agents, 5-fluorouracil, and everolimus, but their efficacy is unclear, according to Dr. Chang, because of a lack of systematic studies.

Investigators thought PD-1 inhibitors might be promising in basal cell carcinoma for a few reasons, Dr. Chang said. In particular, PD-1 inhibitor treatment response has been linked to mutational burden and PD–ligand 1 expression, and advanced basal cell carcinomas have the largest mutational burden of all human cancers, a large proportion of which express PD-L1.

There are multiple case reports in the literature suggesting that advanced basal cell carcinoma is responsive to PD-1 inhibitors, she added.

In the study, nine patients received 200 mg infusion of pembrolizumab every 3 weeks, and seven received the pembrolizumab infusions plus oral vismodegib 150 mg per day.

The pembrolizumab monotherapy group included patients who had tumor progression on vismodegib, did not tolerate vismodegib, or had contraindications to vismodegib. The pembrolizumab-vismodegib regimen was used in patients who had prior stable or partial responses to hedgehog pathway inhibitors.

The overall response rate was 38%, or 6 of 16 patients, with a 70% probability of 1-year progression-free survival and 94% probability of 1-year overall survival, Dr. Chang reported.

The results did not make the case that pembrolizumab and vismodegib was superior to pembrolizumab alone, though as Dr. Chang noted, the numbers of patients were small. Response rates were 29% (two of seven patients) in the combination arm and 44% (four of nine patients) in the monotherapy arm.

There were 24 immune-related adverse events in the trial; the most serious was hyponatremia, which was reversible, according to Dr. Chang. The overall rates of grade 3-4 adverse events were 22% for pembrolizumab monotherapy and 17% for dual therapy.

A report on the study has also been published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Funding for the study was provided by Merck. Dr. Chang reported serving as a clinical investigator and advisory board member for studies sponsored by Genentech-Roche, Merck, Novartis, and Regeneron.

MILAN – A checkpoint inhibitor given with or without targeted therapy resulted in robust response rates in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma, according to an investigator in a recent proof-of-concept study.

The side effect profile for the progressive death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda), plus or minus the hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (Erivedge), was “not out of range” with what’s been observed in other cancer types, said Anne Lynn S. Chang, MD, a medical dermatologist at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Taken together, these safety and efficacy results suggest pembrolizumab could prove useful for patients with advanced basal cell carcinomas, Dr. Chang said in an oral presentation at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Unexpectedly, dual therapy with pembrolizumab and vismodegib was not clearly superior to pembrolizumab alone, though the two arms are not directly comparable in this nonrandomized, investigator-initiated study, according to Dr. Chang.

“That was a surprise for us, but this is a subjective and a small study,” she told attendees at the conference.

There is currently a multi-institutional clinical trial underway to evaluate another PD-1 inhibitor, cemiplimab, in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma previously treated with a hedgehog pathway inhibitor, she said.

While a large fraction of basal cell carcinomas are cured by resection, those that are locally advanced or metastatic to lymph nodes or distant organs are challenging to manage. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors, which include vismodegib and sonidegib, are the only Food and Drug Administration–approved drug class in this setting, but more than half of patients do not have a response to treatment, and another 20% or so will initially respond but develop resistance, Dr. Chang said.

Other treatments that have been tried in advanced basal cell carcinomas include taxanes, platinum-based agents, 5-fluorouracil, and everolimus, but their efficacy is unclear, according to Dr. Chang, because of a lack of systematic studies.

Investigators thought PD-1 inhibitors might be promising in basal cell carcinoma for a few reasons, Dr. Chang said. In particular, PD-1 inhibitor treatment response has been linked to mutational burden and PD–ligand 1 expression, and advanced basal cell carcinomas have the largest mutational burden of all human cancers, a large proportion of which express PD-L1.

There are multiple case reports in the literature suggesting that advanced basal cell carcinoma is responsive to PD-1 inhibitors, she added.

In the study, nine patients received 200 mg infusion of pembrolizumab every 3 weeks, and seven received the pembrolizumab infusions plus oral vismodegib 150 mg per day.

The pembrolizumab monotherapy group included patients who had tumor progression on vismodegib, did not tolerate vismodegib, or had contraindications to vismodegib. The pembrolizumab-vismodegib regimen was used in patients who had prior stable or partial responses to hedgehog pathway inhibitors.

The overall response rate was 38%, or 6 of 16 patients, with a 70% probability of 1-year progression-free survival and 94% probability of 1-year overall survival, Dr. Chang reported.

The results did not make the case that pembrolizumab and vismodegib was superior to pembrolizumab alone, though as Dr. Chang noted, the numbers of patients were small. Response rates were 29% (two of seven patients) in the combination arm and 44% (four of nine patients) in the monotherapy arm.

There were 24 immune-related adverse events in the trial; the most serious was hyponatremia, which was reversible, according to Dr. Chang. The overall rates of grade 3-4 adverse events were 22% for pembrolizumab monotherapy and 17% for dual therapy.

A report on the study has also been published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Funding for the study was provided by Merck. Dr. Chang reported serving as a clinical investigator and advisory board member for studies sponsored by Genentech-Roche, Merck, Novartis, and Regeneron.

REPORTING FROM WCD2019

Painless Nodule on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

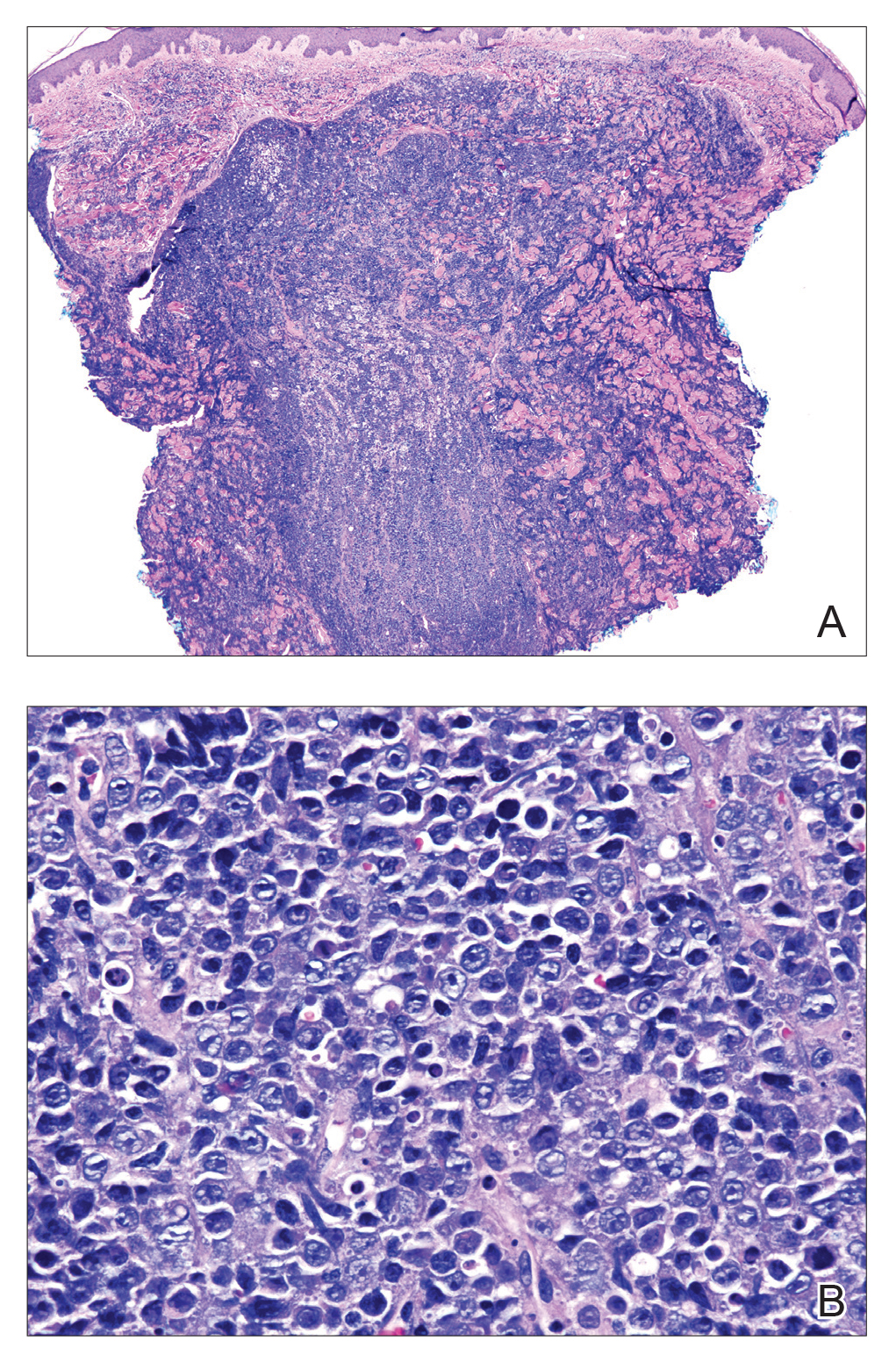

Histopathologic examination revealed a diffuse dense proliferation of large, atypical, and pleomorphic mononuclear cells with prominent nucleoli and many mitotic figures representing plasmacytoid cells in the dermis (Figure). Immunostaining was positive for MUM-1 (marker of late-stage plasma cells and activated T cells) and BCL-2 (antiapoptotic marker). Fluorescent polymerase chain reaction was positive for clonal IgH gene arrangement, and fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for C-MYC rearrangement in 94% of cells. Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization also was positive. Rare cells stained positive for T-cell markers. CD20, BCL-6, and CD30 immunostains were negative, suggesting that these cells were not B or T cells, though terminally differentiated B cells also can lack these markers. Bone marrow biopsy showed a similar staining pattern to the skin with 10% atypical plasmacytoid cells. Computed tomography of the left leg showed an enlargement of the semimembranosus muscle with internal areas of high density and heterogeneous enhancement. The patient underwent decompression of the left peroneal nerve. Biopsy showed a staining pattern similar to the right skin nodule and bone marrow, consistent with lymphoma.

He was diagnosed with stage IV human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) and received 6 cycles of R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) without vincristine with intrathecal methotrexate, followed by 3 cycles of DHAP (dexamethasone, high dose Ara C, cisplatin) with bortezomib and daratumumab after relapse. Ultimately, he underwent autologous stem cell transplantation and was alive 13 months after diagnosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that most commonly arises in the oral cavity of individuals with HIV.1 In addition to HIV infection, PBL also is seen in patients with other causes of immunodeficiency such as iatrogenic immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation.1 The typical disease presentation is an expanding mass in the oral cavity; however, 34% (52/151) of reported cases arose at extraoral primary sites, with a minority of cases confined to cutaneous sites with no systemic involvement.2 Cutaneous PBL presentations may include flesh-colored or purple, grouped or solitary nodules; an erythematous infiltrated plaque; or purple-red ulcerated nodules. The lesions usually are asymptomatic and located on the arms and legs.3

On histologic examination, PBL is characterized by a diffuse monomorphic lymphoid infiltrate that sometimes invades the surrounding soft tissue.4-6 The neoplastic cells have eccentric round nucleoli. Plasmablastic lymphoma characteristically displays a high proliferation index with many mitotic figures and signs of apoptosis.4-6 Definitive diagnosis requires immunohistochemical staining. Typical B-cell antigens (CD20) as well as CD45 are negative, while plasma cell markers such as CD38 are positive. Other B- and T-cell markers usually are negative.5,7 The pathogenesis of PBL is thought to be related to Epstein-Barr virus or human herpesvirus 8 infection. In a series of PBL cases, Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus 8 was positive in 75% (97/129) and 17% (13/75) of tested cases, respectively.1

The prognosis for PBL is poor, with a median overall survival of 15 months and a 3-year survival rate of 25% in HIV-infected individuals.8 However, cutaneous PBL without systemic involvement has a considerably better prognosis, with only 1 of 12 cases resulting in death.2,3,9 Treatment of PBL depends on the extent of the disease. Cutaneous PBL can be treated with surgery and adjuvant radiation.3 Chemotherapy is required for patients with multiple lesions or systemic involvement. Current treatment regimens are similar to those used for other aggressive lymphomas such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone).1 Transplant recipients should have their immunosuppression reduced, and HIV-infected patients should have their highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens optimized. Patients presenting with PBL without HIV should be tested for HIV, as PBL has previously been reported to be the presenting manifestation of HIV infection.10

The differential diagnosis for a rapidly expanding, vascular-appearing, red mass on the legs in an immunosuppressed individual includes abscess, malignancy, Kaposi sarcoma, Sweet syndrome, and tertiary syphilis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sameera Husain, MD (New York, New York), for her assistance with histopathologic photographs and interpretation.

- Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:261-267.

- Heiser D, Müller H, Kempf W, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma of the lower leg in an HIV-negative patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E202-E205.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413-1420.

- Gaidano G, Cerri M, Capello D, et al. Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:622-628.

- Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:8-12.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:804-809.

- Horna P, Hamill JR, Sokol L, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E274-E276.

- Desai RS, Vanaki SS, Puranik RS, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting as a gingival growth in a previously undiagnosed HIV-positive patient: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1358-1361.

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

Histopathologic examination revealed a diffuse dense proliferation of large, atypical, and pleomorphic mononuclear cells with prominent nucleoli and many mitotic figures representing plasmacytoid cells in the dermis (Figure). Immunostaining was positive for MUM-1 (marker of late-stage plasma cells and activated T cells) and BCL-2 (antiapoptotic marker). Fluorescent polymerase chain reaction was positive for clonal IgH gene arrangement, and fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for C-MYC rearrangement in 94% of cells. Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization also was positive. Rare cells stained positive for T-cell markers. CD20, BCL-6, and CD30 immunostains were negative, suggesting that these cells were not B or T cells, though terminally differentiated B cells also can lack these markers. Bone marrow biopsy showed a similar staining pattern to the skin with 10% atypical plasmacytoid cells. Computed tomography of the left leg showed an enlargement of the semimembranosus muscle with internal areas of high density and heterogeneous enhancement. The patient underwent decompression of the left peroneal nerve. Biopsy showed a staining pattern similar to the right skin nodule and bone marrow, consistent with lymphoma.

He was diagnosed with stage IV human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) and received 6 cycles of R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) without vincristine with intrathecal methotrexate, followed by 3 cycles of DHAP (dexamethasone, high dose Ara C, cisplatin) with bortezomib and daratumumab after relapse. Ultimately, he underwent autologous stem cell transplantation and was alive 13 months after diagnosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that most commonly arises in the oral cavity of individuals with HIV.1 In addition to HIV infection, PBL also is seen in patients with other causes of immunodeficiency such as iatrogenic immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation.1 The typical disease presentation is an expanding mass in the oral cavity; however, 34% (52/151) of reported cases arose at extraoral primary sites, with a minority of cases confined to cutaneous sites with no systemic involvement.2 Cutaneous PBL presentations may include flesh-colored or purple, grouped or solitary nodules; an erythematous infiltrated plaque; or purple-red ulcerated nodules. The lesions usually are asymptomatic and located on the arms and legs.3

On histologic examination, PBL is characterized by a diffuse monomorphic lymphoid infiltrate that sometimes invades the surrounding soft tissue.4-6 The neoplastic cells have eccentric round nucleoli. Plasmablastic lymphoma characteristically displays a high proliferation index with many mitotic figures and signs of apoptosis.4-6 Definitive diagnosis requires immunohistochemical staining. Typical B-cell antigens (CD20) as well as CD45 are negative, while plasma cell markers such as CD38 are positive. Other B- and T-cell markers usually are negative.5,7 The pathogenesis of PBL is thought to be related to Epstein-Barr virus or human herpesvirus 8 infection. In a series of PBL cases, Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus 8 was positive in 75% (97/129) and 17% (13/75) of tested cases, respectively.1

The prognosis for PBL is poor, with a median overall survival of 15 months and a 3-year survival rate of 25% in HIV-infected individuals.8 However, cutaneous PBL without systemic involvement has a considerably better prognosis, with only 1 of 12 cases resulting in death.2,3,9 Treatment of PBL depends on the extent of the disease. Cutaneous PBL can be treated with surgery and adjuvant radiation.3 Chemotherapy is required for patients with multiple lesions or systemic involvement. Current treatment regimens are similar to those used for other aggressive lymphomas such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone).1 Transplant recipients should have their immunosuppression reduced, and HIV-infected patients should have their highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens optimized. Patients presenting with PBL without HIV should be tested for HIV, as PBL has previously been reported to be the presenting manifestation of HIV infection.10

The differential diagnosis for a rapidly expanding, vascular-appearing, red mass on the legs in an immunosuppressed individual includes abscess, malignancy, Kaposi sarcoma, Sweet syndrome, and tertiary syphilis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sameera Husain, MD (New York, New York), for her assistance with histopathologic photographs and interpretation.

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

Histopathologic examination revealed a diffuse dense proliferation of large, atypical, and pleomorphic mononuclear cells with prominent nucleoli and many mitotic figures representing plasmacytoid cells in the dermis (Figure). Immunostaining was positive for MUM-1 (marker of late-stage plasma cells and activated T cells) and BCL-2 (antiapoptotic marker). Fluorescent polymerase chain reaction was positive for clonal IgH gene arrangement, and fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for C-MYC rearrangement in 94% of cells. Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization also was positive. Rare cells stained positive for T-cell markers. CD20, BCL-6, and CD30 immunostains were negative, suggesting that these cells were not B or T cells, though terminally differentiated B cells also can lack these markers. Bone marrow biopsy showed a similar staining pattern to the skin with 10% atypical plasmacytoid cells. Computed tomography of the left leg showed an enlargement of the semimembranosus muscle with internal areas of high density and heterogeneous enhancement. The patient underwent decompression of the left peroneal nerve. Biopsy showed a staining pattern similar to the right skin nodule and bone marrow, consistent with lymphoma.

He was diagnosed with stage IV human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) and received 6 cycles of R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) without vincristine with intrathecal methotrexate, followed by 3 cycles of DHAP (dexamethasone, high dose Ara C, cisplatin) with bortezomib and daratumumab after relapse. Ultimately, he underwent autologous stem cell transplantation and was alive 13 months after diagnosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that most commonly arises in the oral cavity of individuals with HIV.1 In addition to HIV infection, PBL also is seen in patients with other causes of immunodeficiency such as iatrogenic immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation.1 The typical disease presentation is an expanding mass in the oral cavity; however, 34% (52/151) of reported cases arose at extraoral primary sites, with a minority of cases confined to cutaneous sites with no systemic involvement.2 Cutaneous PBL presentations may include flesh-colored or purple, grouped or solitary nodules; an erythematous infiltrated plaque; or purple-red ulcerated nodules. The lesions usually are asymptomatic and located on the arms and legs.3

On histologic examination, PBL is characterized by a diffuse monomorphic lymphoid infiltrate that sometimes invades the surrounding soft tissue.4-6 The neoplastic cells have eccentric round nucleoli. Plasmablastic lymphoma characteristically displays a high proliferation index with many mitotic figures and signs of apoptosis.4-6 Definitive diagnosis requires immunohistochemical staining. Typical B-cell antigens (CD20) as well as CD45 are negative, while plasma cell markers such as CD38 are positive. Other B- and T-cell markers usually are negative.5,7 The pathogenesis of PBL is thought to be related to Epstein-Barr virus or human herpesvirus 8 infection. In a series of PBL cases, Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus 8 was positive in 75% (97/129) and 17% (13/75) of tested cases, respectively.1

The prognosis for PBL is poor, with a median overall survival of 15 months and a 3-year survival rate of 25% in HIV-infected individuals.8 However, cutaneous PBL without systemic involvement has a considerably better prognosis, with only 1 of 12 cases resulting in death.2,3,9 Treatment of PBL depends on the extent of the disease. Cutaneous PBL can be treated with surgery and adjuvant radiation.3 Chemotherapy is required for patients with multiple lesions or systemic involvement. Current treatment regimens are similar to those used for other aggressive lymphomas such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone).1 Transplant recipients should have their immunosuppression reduced, and HIV-infected patients should have their highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens optimized. Patients presenting with PBL without HIV should be tested for HIV, as PBL has previously been reported to be the presenting manifestation of HIV infection.10

The differential diagnosis for a rapidly expanding, vascular-appearing, red mass on the legs in an immunosuppressed individual includes abscess, malignancy, Kaposi sarcoma, Sweet syndrome, and tertiary syphilis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sameera Husain, MD (New York, New York), for her assistance with histopathologic photographs and interpretation.

- Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:261-267.

- Heiser D, Müller H, Kempf W, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma of the lower leg in an HIV-negative patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E202-E205.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413-1420.

- Gaidano G, Cerri M, Capello D, et al. Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:622-628.

- Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:8-12.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:804-809.

- Horna P, Hamill JR, Sokol L, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E274-E276.

- Desai RS, Vanaki SS, Puranik RS, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting as a gingival growth in a previously undiagnosed HIV-positive patient: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1358-1361.

- Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:261-267.

- Heiser D, Müller H, Kempf W, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma of the lower leg in an HIV-negative patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E202-E205.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413-1420.

- Gaidano G, Cerri M, Capello D, et al. Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:622-628.

- Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:8-12.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:804-809.

- Horna P, Hamill JR, Sokol L, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E274-E276.

- Desai RS, Vanaki SS, Puranik RS, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting as a gingival growth in a previously undiagnosed HIV-positive patient: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1358-1361.

A 44-year-old man presented with numbness and a burning sensation of the left lateral leg and dorsal foot of 3 days' duration as well as a left foot drop of 1 day's duration. A painless red nodule on the right shin also developed over a 10-day period. He had been diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus a year prior and reported compliance with antiretroviral therapy. There was a newly identified, well-demarcated, 6-cm, round, red-purple, flat-topped, nodular tumor with central depression on the right lateral shin. Ultrasonography of the nodule revealed a heterogeneous septate structure with increased vascularity. There was no regional or generalized lymphadenopathy. Laboratory values were notable for microcytic anemia. The white blood cell count was within reference range. Human immunodeficiency virus RNA viral load was elevated (3183 viral copies/mL [reference range, <20 viral copies/mL]). Two punch biopsies of the nodule were performed.

Phototherapy: Is It Still Important?

Phototherapy has been used to treat skin diseases for millennia. From the Incas to the ancient Greeks and Egyptians, nearly every major civilization has attempted to harness the sun, with some even worshipping it for its healing powers.1 Today, phototherapy remains as important as ever. Despite the technological advances that have brought about biologic medications, small molecule inhibitors, and elegant vehicle delivery systems, phototherapy continues to be a valuable tool in the dermatologist’s armamentarium.

Patient Access to Phototherapy

An important step in successfully managing any disease is access to treatment. In today’s health care landscape, therapeutic decisions frequently are dictated by a patient’s financial situation as well as by the discretion of payers. Costly medications such as biologics often are not accessible to patients on government insurance who fall into the Medicare “donut hole” and may be denied by insurance companies for a myriad of reasons. Luckily, phototherapy typically is well covered and is even a first-line treatment option for some conditions, such as mycosis fungoides.

Nevertheless, phototherapy also has its own unique accessibility hurdles. The time-consuming nature of office-based phototherapy treatment is the main barrier, and many patients find it difficult to incorporate treatments into their daily lives. Additionally, office-based phototherapy units often are clustered in major cities, making access more difficult for rural patients. Because light-responsive conditions often are chronic and may require a lifetime of treatment, home phototherapy units are now being recognized as cost-effective treatment options and are increasingly covered by insurance. In fact, one study comparing psoriasis patients treated with home narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) vs outpatient NB-UVB found that in-home treatment was equally as effective as office-based treatment at a similar cost.2 Because studies comparing the effectiveness of office-based vs home-based phototherapy treatment are underway for various other diseases, hopefully more patients will be able to receive home units, thus increasing access to safe and effective treatment.

Wide Range of Treatment Indications

Another merit of phototherapy is its ability to be used in almost all patient populations. It is one of the few modalities whose indications span the entire length of the human lifetime—from pediatric atopic dermatitis to chronic pruritus in elderly patients. Phototherapy also is one of the few treatment options that is safe to use in patients with an active malignancy or in patients who have multiple other medical conditions. Comorbidities including congestive heart failure, chronic infections, and demyelinating disorders often prevent the use of oral and injectable medications for immune-mediated disorders such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. In patients with multiple comorbidities whose disease remains uncontrolled despite an adequate topical regimen, phototherapy is one of the few effective treatment options that remain. Additionally, there is a considerable number of patients who prefer external treatments for cutaneous diseases. For these patients, phototherapy offers the opportunity to control skin conditions without the use of an internal medication.

Favorable Safety Profile

Phototherapy is a largely benign intervention with an excellent safety profile. Its main potential adverse events include erythema, pruritus, xerosis, recurrence of herpes simplex virus infection, and premature skin aging. The effects of phototherapy on skin carcinogenesis have long been controversial; however, data suggest a clear distinction in risk between treatment with NB-UVB and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA). A systematic review of psoriasis patients treated with phototherapy found no evidence to suggest an increased risk of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer with NB-UVB treatment.3 The same cannot be said for psoriasis patients treated with PUVA, who were noted to have a higher incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer than the general population. This increased risk was more substantial in American cohorts than in European cohorts, likely due to multiple factors including variable skin types and treatment regimens. Increased rates of melanoma also were noted in American PUVA cohorts, with no similar increase seen in their European counterparts.3

Broad vs Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies have dominated the health care landscape over the last few years, with the majority of new medications being highly focused and only efficacious in a few conditions. One of phototherapy’s greatest strengths is its lack of specificity. Because the field of dermatology is filled with rare, overlapping, and often poorly understood diseases, nonspecific treatment options are needed to fill the gaps. Many generalized skin conditions may lack treatment options indicated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Phototherapy is the ultimate untargeted intervention and may be broadly used for a wide range of cutaneous conditions. Although classically utilized for atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, NB-UVB also can effectively treat generalized pruritus, vitiligo, urticaria, and seborrheic dermatitis.4 Not to be outdone, PUVA has shown success in treating more than 50 different dermatologic conditions including lichen planus, alopecia areata, and mycosis fungoides.

Final Thoughts

Phototherapy is a safe, accessible, and widely applicable treatment for a range of cutaneous disorders. Although more precisely engineered internal therapies have begun to replace UV light in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, phototherapy likely will always remain an ideal treatment for a wide cohort of patients. Between increased access to home units and the continued validation of its excellent safety record, the future of phototherapy is looking bright.

- Grzybowski A, Sak J, Pawlikowski J. A brief report on the history of phototherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:532-537.

- Koek MB, Sigurdsson V, van Weelden H, et al. Cost effectiveness of home ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis: economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2010;340:c1490.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):22-31.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ledo E, Ledo A. Phototherapy, photochemotherapy, and photodynamic therapy: unapproved uses or indications. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:77-86.

Phototherapy has been used to treat skin diseases for millennia. From the Incas to the ancient Greeks and Egyptians, nearly every major civilization has attempted to harness the sun, with some even worshipping it for its healing powers.1 Today, phototherapy remains as important as ever. Despite the technological advances that have brought about biologic medications, small molecule inhibitors, and elegant vehicle delivery systems, phototherapy continues to be a valuable tool in the dermatologist’s armamentarium.

Patient Access to Phototherapy

An important step in successfully managing any disease is access to treatment. In today’s health care landscape, therapeutic decisions frequently are dictated by a patient’s financial situation as well as by the discretion of payers. Costly medications such as biologics often are not accessible to patients on government insurance who fall into the Medicare “donut hole” and may be denied by insurance companies for a myriad of reasons. Luckily, phototherapy typically is well covered and is even a first-line treatment option for some conditions, such as mycosis fungoides.

Nevertheless, phototherapy also has its own unique accessibility hurdles. The time-consuming nature of office-based phototherapy treatment is the main barrier, and many patients find it difficult to incorporate treatments into their daily lives. Additionally, office-based phototherapy units often are clustered in major cities, making access more difficult for rural patients. Because light-responsive conditions often are chronic and may require a lifetime of treatment, home phototherapy units are now being recognized as cost-effective treatment options and are increasingly covered by insurance. In fact, one study comparing psoriasis patients treated with home narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) vs outpatient NB-UVB found that in-home treatment was equally as effective as office-based treatment at a similar cost.2 Because studies comparing the effectiveness of office-based vs home-based phototherapy treatment are underway for various other diseases, hopefully more patients will be able to receive home units, thus increasing access to safe and effective treatment.

Wide Range of Treatment Indications

Another merit of phototherapy is its ability to be used in almost all patient populations. It is one of the few modalities whose indications span the entire length of the human lifetime—from pediatric atopic dermatitis to chronic pruritus in elderly patients. Phototherapy also is one of the few treatment options that is safe to use in patients with an active malignancy or in patients who have multiple other medical conditions. Comorbidities including congestive heart failure, chronic infections, and demyelinating disorders often prevent the use of oral and injectable medications for immune-mediated disorders such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. In patients with multiple comorbidities whose disease remains uncontrolled despite an adequate topical regimen, phototherapy is one of the few effective treatment options that remain. Additionally, there is a considerable number of patients who prefer external treatments for cutaneous diseases. For these patients, phototherapy offers the opportunity to control skin conditions without the use of an internal medication.

Favorable Safety Profile

Phototherapy is a largely benign intervention with an excellent safety profile. Its main potential adverse events include erythema, pruritus, xerosis, recurrence of herpes simplex virus infection, and premature skin aging. The effects of phototherapy on skin carcinogenesis have long been controversial; however, data suggest a clear distinction in risk between treatment with NB-UVB and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA). A systematic review of psoriasis patients treated with phototherapy found no evidence to suggest an increased risk of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer with NB-UVB treatment.3 The same cannot be said for psoriasis patients treated with PUVA, who were noted to have a higher incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer than the general population. This increased risk was more substantial in American cohorts than in European cohorts, likely due to multiple factors including variable skin types and treatment regimens. Increased rates of melanoma also were noted in American PUVA cohorts, with no similar increase seen in their European counterparts.3

Broad vs Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies have dominated the health care landscape over the last few years, with the majority of new medications being highly focused and only efficacious in a few conditions. One of phototherapy’s greatest strengths is its lack of specificity. Because the field of dermatology is filled with rare, overlapping, and often poorly understood diseases, nonspecific treatment options are needed to fill the gaps. Many generalized skin conditions may lack treatment options indicated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Phototherapy is the ultimate untargeted intervention and may be broadly used for a wide range of cutaneous conditions. Although classically utilized for atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, NB-UVB also can effectively treat generalized pruritus, vitiligo, urticaria, and seborrheic dermatitis.4 Not to be outdone, PUVA has shown success in treating more than 50 different dermatologic conditions including lichen planus, alopecia areata, and mycosis fungoides.

Final Thoughts

Phototherapy is a safe, accessible, and widely applicable treatment for a range of cutaneous disorders. Although more precisely engineered internal therapies have begun to replace UV light in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, phototherapy likely will always remain an ideal treatment for a wide cohort of patients. Between increased access to home units and the continued validation of its excellent safety record, the future of phototherapy is looking bright.

Phototherapy has been used to treat skin diseases for millennia. From the Incas to the ancient Greeks and Egyptians, nearly every major civilization has attempted to harness the sun, with some even worshipping it for its healing powers.1 Today, phototherapy remains as important as ever. Despite the technological advances that have brought about biologic medications, small molecule inhibitors, and elegant vehicle delivery systems, phototherapy continues to be a valuable tool in the dermatologist’s armamentarium.

Patient Access to Phototherapy

An important step in successfully managing any disease is access to treatment. In today’s health care landscape, therapeutic decisions frequently are dictated by a patient’s financial situation as well as by the discretion of payers. Costly medications such as biologics often are not accessible to patients on government insurance who fall into the Medicare “donut hole” and may be denied by insurance companies for a myriad of reasons. Luckily, phototherapy typically is well covered and is even a first-line treatment option for some conditions, such as mycosis fungoides.

Nevertheless, phototherapy also has its own unique accessibility hurdles. The time-consuming nature of office-based phototherapy treatment is the main barrier, and many patients find it difficult to incorporate treatments into their daily lives. Additionally, office-based phototherapy units often are clustered in major cities, making access more difficult for rural patients. Because light-responsive conditions often are chronic and may require a lifetime of treatment, home phototherapy units are now being recognized as cost-effective treatment options and are increasingly covered by insurance. In fact, one study comparing psoriasis patients treated with home narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) vs outpatient NB-UVB found that in-home treatment was equally as effective as office-based treatment at a similar cost.2 Because studies comparing the effectiveness of office-based vs home-based phototherapy treatment are underway for various other diseases, hopefully more patients will be able to receive home units, thus increasing access to safe and effective treatment.

Wide Range of Treatment Indications

Another merit of phototherapy is its ability to be used in almost all patient populations. It is one of the few modalities whose indications span the entire length of the human lifetime—from pediatric atopic dermatitis to chronic pruritus in elderly patients. Phototherapy also is one of the few treatment options that is safe to use in patients with an active malignancy or in patients who have multiple other medical conditions. Comorbidities including congestive heart failure, chronic infections, and demyelinating disorders often prevent the use of oral and injectable medications for immune-mediated disorders such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. In patients with multiple comorbidities whose disease remains uncontrolled despite an adequate topical regimen, phototherapy is one of the few effective treatment options that remain. Additionally, there is a considerable number of patients who prefer external treatments for cutaneous diseases. For these patients, phototherapy offers the opportunity to control skin conditions without the use of an internal medication.

Favorable Safety Profile

Phototherapy is a largely benign intervention with an excellent safety profile. Its main potential adverse events include erythema, pruritus, xerosis, recurrence of herpes simplex virus infection, and premature skin aging. The effects of phototherapy on skin carcinogenesis have long been controversial; however, data suggest a clear distinction in risk between treatment with NB-UVB and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA). A systematic review of psoriasis patients treated with phototherapy found no evidence to suggest an increased risk of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer with NB-UVB treatment.3 The same cannot be said for psoriasis patients treated with PUVA, who were noted to have a higher incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer than the general population. This increased risk was more substantial in American cohorts than in European cohorts, likely due to multiple factors including variable skin types and treatment regimens. Increased rates of melanoma also were noted in American PUVA cohorts, with no similar increase seen in their European counterparts.3

Broad vs Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies have dominated the health care landscape over the last few years, with the majority of new medications being highly focused and only efficacious in a few conditions. One of phototherapy’s greatest strengths is its lack of specificity. Because the field of dermatology is filled with rare, overlapping, and often poorly understood diseases, nonspecific treatment options are needed to fill the gaps. Many generalized skin conditions may lack treatment options indicated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Phototherapy is the ultimate untargeted intervention and may be broadly used for a wide range of cutaneous conditions. Although classically utilized for atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, NB-UVB also can effectively treat generalized pruritus, vitiligo, urticaria, and seborrheic dermatitis.4 Not to be outdone, PUVA has shown success in treating more than 50 different dermatologic conditions including lichen planus, alopecia areata, and mycosis fungoides.

Final Thoughts

Phototherapy is a safe, accessible, and widely applicable treatment for a range of cutaneous disorders. Although more precisely engineered internal therapies have begun to replace UV light in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, phototherapy likely will always remain an ideal treatment for a wide cohort of patients. Between increased access to home units and the continued validation of its excellent safety record, the future of phototherapy is looking bright.

- Grzybowski A, Sak J, Pawlikowski J. A brief report on the history of phototherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:532-537.

- Koek MB, Sigurdsson V, van Weelden H, et al. Cost effectiveness of home ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis: economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2010;340:c1490.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):22-31.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ledo E, Ledo A. Phototherapy, photochemotherapy, and photodynamic therapy: unapproved uses or indications. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:77-86.

- Grzybowski A, Sak J, Pawlikowski J. A brief report on the history of phototherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:532-537.

- Koek MB, Sigurdsson V, van Weelden H, et al. Cost effectiveness of home ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis: economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2010;340:c1490.

- Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):22-31.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ledo E, Ledo A. Phototherapy, photochemotherapy, and photodynamic therapy: unapproved uses or indications. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:77-86.

Clinical Pearl: Advantages of the Scalp as a Split-Thickness Skin Graft Donor Site

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

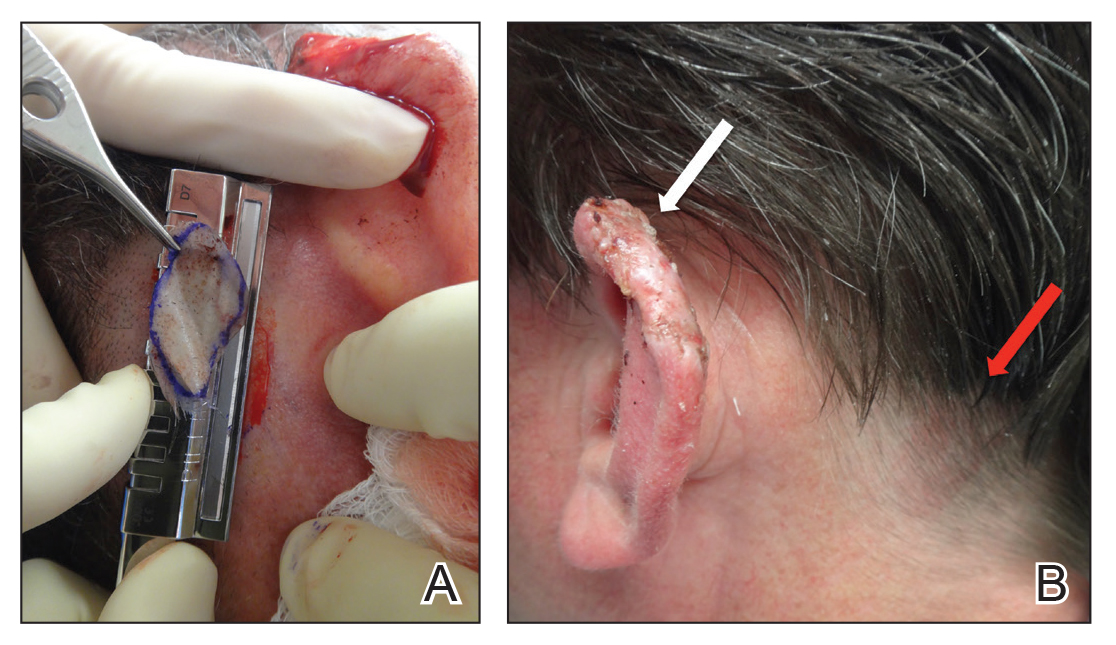

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.