User login

Anxiety, inactivity linked to cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s disease patients who develop anxiety early in their disease are at risk for reduced physical activity, which promotes further anxiety and cognitive decline, data from nearly 500 individuals show.

Anxiety occurs in 20%-60% of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients but often goes undiagnosed, wrote Jacob D. Jones, PhD, of California State University, San Bernardino, and colleagues.

“Anxiety can attenuate motivation to engage in physical activity leading to more anxiety and other negative cognitive outcomes,” although physical activity has been shown to improve cognitive function in PD patients, they said. However, physical activity as a mediator between anxiety and cognitive function in PD has not been well studied, they noted.

In a study published in Mental Health and Physical Activity Participants were followed for up to 5 years and completed neuropsychological tests, tests of motor severity, and self-reports on anxiety and physical activity. Anxiety was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait (STAI-T) subscale. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). Motor severity was assessed using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-Part III (UPDRS). The average age of the participants was 61 years, 65% were men, and 96% were White.

Using a direct-effect model, the researchers found that individuals whose anxiety increased during the study period also showed signs of cognitive decline. A significant between-person effect showed that individuals who were generally more anxious also scored lower on cognitive tests over the 5-year study period.

In a mediation model computed with structural equation modeling, physical activity mediated the link between anxiety and cognition, most notably household activity.

“There was a significant within-person association between anxiety and household activities, meaning that individuals who became more anxious over the 5-year study also became less active in the home,” reported Dr. Jones and colleagues.

However, no significant indirect effect was noted regarding the between-person findings of the impact of physical activity on anxiety and cognitive decline. Although more severe anxiety was associated with less activity, cognitive performance was not associated with either type of physical activity.

The presence of a within-person effect “suggests that reductions in physical activity, specifically within the first 5 years of disease onset, may be detrimental to mental health,” the researchers emphasized. Given that the study population was newly diagnosed with PD “it is likely the within-person terms are more sensitive to changes in anxiety, physical activity, and cognition that are more directly the result of the PD process, as opposed to lifestyle/preexisting traits,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of self-reports to measure physical activity, and the lack of granular information about the details of physical activity, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the inclusion of only newly diagnosed PD patients, which might limit generalizability.

“Future research is warranted to understand if other modes, intensities, or complexities of physical activity impact individuals with PD in a different manner in relation to cognition,” they said.

Dr. Jones and colleagues had no disclosures. The PPMI is supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Parkinson’s disease patients who develop anxiety early in their disease are at risk for reduced physical activity, which promotes further anxiety and cognitive decline, data from nearly 500 individuals show.

Anxiety occurs in 20%-60% of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients but often goes undiagnosed, wrote Jacob D. Jones, PhD, of California State University, San Bernardino, and colleagues.

“Anxiety can attenuate motivation to engage in physical activity leading to more anxiety and other negative cognitive outcomes,” although physical activity has been shown to improve cognitive function in PD patients, they said. However, physical activity as a mediator between anxiety and cognitive function in PD has not been well studied, they noted.

In a study published in Mental Health and Physical Activity Participants were followed for up to 5 years and completed neuropsychological tests, tests of motor severity, and self-reports on anxiety and physical activity. Anxiety was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait (STAI-T) subscale. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). Motor severity was assessed using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-Part III (UPDRS). The average age of the participants was 61 years, 65% were men, and 96% were White.

Using a direct-effect model, the researchers found that individuals whose anxiety increased during the study period also showed signs of cognitive decline. A significant between-person effect showed that individuals who were generally more anxious also scored lower on cognitive tests over the 5-year study period.

In a mediation model computed with structural equation modeling, physical activity mediated the link between anxiety and cognition, most notably household activity.

“There was a significant within-person association between anxiety and household activities, meaning that individuals who became more anxious over the 5-year study also became less active in the home,” reported Dr. Jones and colleagues.

However, no significant indirect effect was noted regarding the between-person findings of the impact of physical activity on anxiety and cognitive decline. Although more severe anxiety was associated with less activity, cognitive performance was not associated with either type of physical activity.

The presence of a within-person effect “suggests that reductions in physical activity, specifically within the first 5 years of disease onset, may be detrimental to mental health,” the researchers emphasized. Given that the study population was newly diagnosed with PD “it is likely the within-person terms are more sensitive to changes in anxiety, physical activity, and cognition that are more directly the result of the PD process, as opposed to lifestyle/preexisting traits,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of self-reports to measure physical activity, and the lack of granular information about the details of physical activity, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the inclusion of only newly diagnosed PD patients, which might limit generalizability.

“Future research is warranted to understand if other modes, intensities, or complexities of physical activity impact individuals with PD in a different manner in relation to cognition,” they said.

Dr. Jones and colleagues had no disclosures. The PPMI is supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Parkinson’s disease patients who develop anxiety early in their disease are at risk for reduced physical activity, which promotes further anxiety and cognitive decline, data from nearly 500 individuals show.

Anxiety occurs in 20%-60% of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients but often goes undiagnosed, wrote Jacob D. Jones, PhD, of California State University, San Bernardino, and colleagues.

“Anxiety can attenuate motivation to engage in physical activity leading to more anxiety and other negative cognitive outcomes,” although physical activity has been shown to improve cognitive function in PD patients, they said. However, physical activity as a mediator between anxiety and cognitive function in PD has not been well studied, they noted.

In a study published in Mental Health and Physical Activity Participants were followed for up to 5 years and completed neuropsychological tests, tests of motor severity, and self-reports on anxiety and physical activity. Anxiety was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait (STAI-T) subscale. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). Motor severity was assessed using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-Part III (UPDRS). The average age of the participants was 61 years, 65% were men, and 96% were White.

Using a direct-effect model, the researchers found that individuals whose anxiety increased during the study period also showed signs of cognitive decline. A significant between-person effect showed that individuals who were generally more anxious also scored lower on cognitive tests over the 5-year study period.

In a mediation model computed with structural equation modeling, physical activity mediated the link between anxiety and cognition, most notably household activity.

“There was a significant within-person association between anxiety and household activities, meaning that individuals who became more anxious over the 5-year study also became less active in the home,” reported Dr. Jones and colleagues.

However, no significant indirect effect was noted regarding the between-person findings of the impact of physical activity on anxiety and cognitive decline. Although more severe anxiety was associated with less activity, cognitive performance was not associated with either type of physical activity.

The presence of a within-person effect “suggests that reductions in physical activity, specifically within the first 5 years of disease onset, may be detrimental to mental health,” the researchers emphasized. Given that the study population was newly diagnosed with PD “it is likely the within-person terms are more sensitive to changes in anxiety, physical activity, and cognition that are more directly the result of the PD process, as opposed to lifestyle/preexisting traits,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of self-reports to measure physical activity, and the lack of granular information about the details of physical activity, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the inclusion of only newly diagnosed PD patients, which might limit generalizability.

“Future research is warranted to understand if other modes, intensities, or complexities of physical activity impact individuals with PD in a different manner in relation to cognition,” they said.

Dr. Jones and colleagues had no disclosures. The PPMI is supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including numerous pharmaceutical companies.

FROM MENTAL HEALTH AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Early data for experimental THC drug ‘promising’ for Tourette’s

Oral delta-9-tetrahydracannabinol (delta-9-THC) and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), in a proprietary combination known as THX-110, is promising for reducing tic symptoms in adults with Tourette syndrome (TS), new research suggests.

In a small phase 2 trial, investigators administered THX-110 to 16 adults with treatment-resistant TS for 12 weeks. Results showed a reduction of more than 20% in tic symptoms after the first week of treatment compared with baseline.

“We conducted an uncontrolled study in adults with severe TS and found that their tics improved over time while they took THX-110,” lead author Michael Bloch, MD, associate professor and co-director of the Tic and OCD Program at the Child Study Center, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., told this news organization.

Dr. Bloch added that the next step in this line of research will be to conduct a placebo-controlled trial of the compound in order to assess whether tic improvement observed over time in this study “was due to the effects of the medication and not related to the natural waxing-and-waning course of tic symptoms or treatment expectancy.”

The findings were published online August 2 in the Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences.

‘Entourage effect’

“Several lines of evidence from clinical observation and even randomized controlled trials” suggest that cannabis (cannabis sativa) and delta-9-THC may be effective in treatment of tic disorders, Dr. Bloch said.

“Cannabinoid receptors are present in the motor regions important for tics, and thus, there is a potential mechanism of action to lead to improvement of tics,” he added.

However, “the major limitations of both cannabis and dronabinol [a synthetic form of delta-9-THC] use are the adverse psychoactive effects they induce in higher doses,” he said.

Dr. Bloch noted that PEA is a lipid messenger “known to mimic several endocannabinoid-driven activities.”

For this reason, combining delta-9-THC with PEA is hypothesized to reduce the dose of delta-9-THC needed to improve tics and also potentially lessen its side effects.

This initial open-label trial examined safety and tolerability of THX-110, as well as its effect on tic symptoms in adults with TS. The researchers hoped to “use the entourage effect to deliver the therapeutic benefits of delta-9-THC in reducing tics with decrease psychoactive effects by combining with PEA.”

The “entourage effect” refers to “endocannabinoid regulation by which multiple endogenous cannabinoid chemical species display a cooperative effect in eliciting a cellular response,” they write.

The investigators conducted a 12-week uncontrolled trial of THX-110, used at its maximum daily dose of delta-9-THC (10 mg) and a constant 800-mg dose of PEA in 16 adults with TS (mean age, 35 years; mean TS illness duration, 26.6 years).

Participants had a mean baseline Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) score of 38.1 and a mean worst-ever total tic score of 45.4.

All participants were experiencing persistent tics, despite having tried an array of previous evidence-based treatments for TS, including antipsychotics, alpha-2 agonists, VMAT2 inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and topiramate (Topamax).

Significant improvement

Results showed significant improvement in tic symptoms with TXH-110 treatment over time (general linear model time factor: F = 3.06, df = 7.91, P = .006).

At first assessment point, mean YGTSS improvement was 3.5 (95% confidence interval, 0.1-6.9; P = .047). The improvement not only remained significant but continued to increase throughout the 12-week trial period.

At 12 weeks, the maximal improvement in tic symptoms was observed, with a mean YGTSS improvement at endpoint of 7.6 (95% CI, 2.5-12.8; P = .007).

Four patients experienced a greater than 35% improvement in tic symptoms during the trial, whereas 6 experienced a 25% or greater improvement. The mean improvement in tic symptoms over the course of the trial was 20.6%.

There was also a significant improvement between baseline and endpoint on other measures of tic symptoms – but not on premonitory urges.

The patients experienced “modest” but not significant improvement in comorbid symptoms, including attentional, anxiety, depressive, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Adverse events

All participants experienced some mild side effects for “a couple hours” after taking the medication, particularly during the course of dose escalation and maintenance. However, these were not serious enough to warrant stopping the medication.

These effects typically included fatigue/drowsiness, feeling “high,” dry mouth, dizziness/lightheadedness, and difficulty concentrating.

Side effects of moderate or greater severity necessitating changes in medication dosing were “less common,” the investigators report. No participants experienced significant laboratory abnormalities.

One patient discontinued the trial early because he felt that the study medication was not helpful, and a second discontinued because of drowsiness and fatigue related to the study medication.

Twelve participants elected to continue treatment with THX-110 during an open extension phase and 7 of these completed the additional 24 weeks.

“THX-110 treatment led to an average improvement in tic symptoms of roughly 20%, or a 7-point decrease in the YGTSS total tic score. This improvement translates to a large effect size (d = 0.92) of improvement over time,” the investigators write.

More data needed

Commenting on the findings, Yolanda Holler-Managan, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics (neurology), Northwestern University, Chicago, cautioned that this was not a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group placebo-controlled study.

Instead, it was a clinical study to prove safety, tolerability, and dosing of the combination medication in adult patients with TS and “does not provide as much weight, since we do not have many studies on the efficacy of cannabinoids,” said Dr. Holler-Managan, who was not involved with the research.

She noted that the American Academy of Neurology’s 2019 practice guideline recommendations for treatment of tics in individuals with TS and tic disorders reported “limited evidence” that delta-9-THC is “possibly more likely than placebo to reduce tic severity in adults with TS, therefore we need more data.”

The current investigators agree. “Although these initial data are promising, future randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials are necessary to demonstrate efficacy of TXH-110 treatment,” they write.

They add that the psychoactive properties of cannabis-derived compounds make it challenging to design a properly blinded trial.

“Incorporation of physiologic biomarkers and objective measures of symptoms (e.g., videotaped tic counts by blinded raters) may be particularly important when examining these medications with psychoactive properties that may be prone to reporting bias,” the authors write.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant to Dr. Bloch from Therapix Biosciences. The state of Connecticut also provided resource support via the Abraham Ribicoff Research Facilities at the Connecticut Mental Health Center. Dr. Bloch serves on the scientific advisory boards of Therapix Biosciences, and he receives research support from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, NARSAD, Neurocrine Biosciences, NIH, and the Patterson Foundation. The other investigators and Dr. Holler-Managan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oral delta-9-tetrahydracannabinol (delta-9-THC) and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), in a proprietary combination known as THX-110, is promising for reducing tic symptoms in adults with Tourette syndrome (TS), new research suggests.

In a small phase 2 trial, investigators administered THX-110 to 16 adults with treatment-resistant TS for 12 weeks. Results showed a reduction of more than 20% in tic symptoms after the first week of treatment compared with baseline.

“We conducted an uncontrolled study in adults with severe TS and found that their tics improved over time while they took THX-110,” lead author Michael Bloch, MD, associate professor and co-director of the Tic and OCD Program at the Child Study Center, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., told this news organization.

Dr. Bloch added that the next step in this line of research will be to conduct a placebo-controlled trial of the compound in order to assess whether tic improvement observed over time in this study “was due to the effects of the medication and not related to the natural waxing-and-waning course of tic symptoms or treatment expectancy.”

The findings were published online August 2 in the Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences.

‘Entourage effect’

“Several lines of evidence from clinical observation and even randomized controlled trials” suggest that cannabis (cannabis sativa) and delta-9-THC may be effective in treatment of tic disorders, Dr. Bloch said.

“Cannabinoid receptors are present in the motor regions important for tics, and thus, there is a potential mechanism of action to lead to improvement of tics,” he added.

However, “the major limitations of both cannabis and dronabinol [a synthetic form of delta-9-THC] use are the adverse psychoactive effects they induce in higher doses,” he said.

Dr. Bloch noted that PEA is a lipid messenger “known to mimic several endocannabinoid-driven activities.”

For this reason, combining delta-9-THC with PEA is hypothesized to reduce the dose of delta-9-THC needed to improve tics and also potentially lessen its side effects.

This initial open-label trial examined safety and tolerability of THX-110, as well as its effect on tic symptoms in adults with TS. The researchers hoped to “use the entourage effect to deliver the therapeutic benefits of delta-9-THC in reducing tics with decrease psychoactive effects by combining with PEA.”

The “entourage effect” refers to “endocannabinoid regulation by which multiple endogenous cannabinoid chemical species display a cooperative effect in eliciting a cellular response,” they write.

The investigators conducted a 12-week uncontrolled trial of THX-110, used at its maximum daily dose of delta-9-THC (10 mg) and a constant 800-mg dose of PEA in 16 adults with TS (mean age, 35 years; mean TS illness duration, 26.6 years).

Participants had a mean baseline Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) score of 38.1 and a mean worst-ever total tic score of 45.4.

All participants were experiencing persistent tics, despite having tried an array of previous evidence-based treatments for TS, including antipsychotics, alpha-2 agonists, VMAT2 inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and topiramate (Topamax).

Significant improvement

Results showed significant improvement in tic symptoms with TXH-110 treatment over time (general linear model time factor: F = 3.06, df = 7.91, P = .006).

At first assessment point, mean YGTSS improvement was 3.5 (95% confidence interval, 0.1-6.9; P = .047). The improvement not only remained significant but continued to increase throughout the 12-week trial period.

At 12 weeks, the maximal improvement in tic symptoms was observed, with a mean YGTSS improvement at endpoint of 7.6 (95% CI, 2.5-12.8; P = .007).

Four patients experienced a greater than 35% improvement in tic symptoms during the trial, whereas 6 experienced a 25% or greater improvement. The mean improvement in tic symptoms over the course of the trial was 20.6%.

There was also a significant improvement between baseline and endpoint on other measures of tic symptoms – but not on premonitory urges.

The patients experienced “modest” but not significant improvement in comorbid symptoms, including attentional, anxiety, depressive, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Adverse events

All participants experienced some mild side effects for “a couple hours” after taking the medication, particularly during the course of dose escalation and maintenance. However, these were not serious enough to warrant stopping the medication.

These effects typically included fatigue/drowsiness, feeling “high,” dry mouth, dizziness/lightheadedness, and difficulty concentrating.

Side effects of moderate or greater severity necessitating changes in medication dosing were “less common,” the investigators report. No participants experienced significant laboratory abnormalities.

One patient discontinued the trial early because he felt that the study medication was not helpful, and a second discontinued because of drowsiness and fatigue related to the study medication.

Twelve participants elected to continue treatment with THX-110 during an open extension phase and 7 of these completed the additional 24 weeks.

“THX-110 treatment led to an average improvement in tic symptoms of roughly 20%, or a 7-point decrease in the YGTSS total tic score. This improvement translates to a large effect size (d = 0.92) of improvement over time,” the investigators write.

More data needed

Commenting on the findings, Yolanda Holler-Managan, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics (neurology), Northwestern University, Chicago, cautioned that this was not a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group placebo-controlled study.

Instead, it was a clinical study to prove safety, tolerability, and dosing of the combination medication in adult patients with TS and “does not provide as much weight, since we do not have many studies on the efficacy of cannabinoids,” said Dr. Holler-Managan, who was not involved with the research.

She noted that the American Academy of Neurology’s 2019 practice guideline recommendations for treatment of tics in individuals with TS and tic disorders reported “limited evidence” that delta-9-THC is “possibly more likely than placebo to reduce tic severity in adults with TS, therefore we need more data.”

The current investigators agree. “Although these initial data are promising, future randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials are necessary to demonstrate efficacy of TXH-110 treatment,” they write.

They add that the psychoactive properties of cannabis-derived compounds make it challenging to design a properly blinded trial.

“Incorporation of physiologic biomarkers and objective measures of symptoms (e.g., videotaped tic counts by blinded raters) may be particularly important when examining these medications with psychoactive properties that may be prone to reporting bias,” the authors write.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant to Dr. Bloch from Therapix Biosciences. The state of Connecticut also provided resource support via the Abraham Ribicoff Research Facilities at the Connecticut Mental Health Center. Dr. Bloch serves on the scientific advisory boards of Therapix Biosciences, and he receives research support from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, NARSAD, Neurocrine Biosciences, NIH, and the Patterson Foundation. The other investigators and Dr. Holler-Managan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oral delta-9-tetrahydracannabinol (delta-9-THC) and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), in a proprietary combination known as THX-110, is promising for reducing tic symptoms in adults with Tourette syndrome (TS), new research suggests.

In a small phase 2 trial, investigators administered THX-110 to 16 adults with treatment-resistant TS for 12 weeks. Results showed a reduction of more than 20% in tic symptoms after the first week of treatment compared with baseline.

“We conducted an uncontrolled study in adults with severe TS and found that their tics improved over time while they took THX-110,” lead author Michael Bloch, MD, associate professor and co-director of the Tic and OCD Program at the Child Study Center, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., told this news organization.

Dr. Bloch added that the next step in this line of research will be to conduct a placebo-controlled trial of the compound in order to assess whether tic improvement observed over time in this study “was due to the effects of the medication and not related to the natural waxing-and-waning course of tic symptoms or treatment expectancy.”

The findings were published online August 2 in the Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences.

‘Entourage effect’

“Several lines of evidence from clinical observation and even randomized controlled trials” suggest that cannabis (cannabis sativa) and delta-9-THC may be effective in treatment of tic disorders, Dr. Bloch said.

“Cannabinoid receptors are present in the motor regions important for tics, and thus, there is a potential mechanism of action to lead to improvement of tics,” he added.

However, “the major limitations of both cannabis and dronabinol [a synthetic form of delta-9-THC] use are the adverse psychoactive effects they induce in higher doses,” he said.

Dr. Bloch noted that PEA is a lipid messenger “known to mimic several endocannabinoid-driven activities.”

For this reason, combining delta-9-THC with PEA is hypothesized to reduce the dose of delta-9-THC needed to improve tics and also potentially lessen its side effects.

This initial open-label trial examined safety and tolerability of THX-110, as well as its effect on tic symptoms in adults with TS. The researchers hoped to “use the entourage effect to deliver the therapeutic benefits of delta-9-THC in reducing tics with decrease psychoactive effects by combining with PEA.”

The “entourage effect” refers to “endocannabinoid regulation by which multiple endogenous cannabinoid chemical species display a cooperative effect in eliciting a cellular response,” they write.

The investigators conducted a 12-week uncontrolled trial of THX-110, used at its maximum daily dose of delta-9-THC (10 mg) and a constant 800-mg dose of PEA in 16 adults with TS (mean age, 35 years; mean TS illness duration, 26.6 years).

Participants had a mean baseline Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) score of 38.1 and a mean worst-ever total tic score of 45.4.

All participants were experiencing persistent tics, despite having tried an array of previous evidence-based treatments for TS, including antipsychotics, alpha-2 agonists, VMAT2 inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and topiramate (Topamax).

Significant improvement

Results showed significant improvement in tic symptoms with TXH-110 treatment over time (general linear model time factor: F = 3.06, df = 7.91, P = .006).

At first assessment point, mean YGTSS improvement was 3.5 (95% confidence interval, 0.1-6.9; P = .047). The improvement not only remained significant but continued to increase throughout the 12-week trial period.

At 12 weeks, the maximal improvement in tic symptoms was observed, with a mean YGTSS improvement at endpoint of 7.6 (95% CI, 2.5-12.8; P = .007).

Four patients experienced a greater than 35% improvement in tic symptoms during the trial, whereas 6 experienced a 25% or greater improvement. The mean improvement in tic symptoms over the course of the trial was 20.6%.

There was also a significant improvement between baseline and endpoint on other measures of tic symptoms – but not on premonitory urges.

The patients experienced “modest” but not significant improvement in comorbid symptoms, including attentional, anxiety, depressive, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Adverse events

All participants experienced some mild side effects for “a couple hours” after taking the medication, particularly during the course of dose escalation and maintenance. However, these were not serious enough to warrant stopping the medication.

These effects typically included fatigue/drowsiness, feeling “high,” dry mouth, dizziness/lightheadedness, and difficulty concentrating.

Side effects of moderate or greater severity necessitating changes in medication dosing were “less common,” the investigators report. No participants experienced significant laboratory abnormalities.

One patient discontinued the trial early because he felt that the study medication was not helpful, and a second discontinued because of drowsiness and fatigue related to the study medication.

Twelve participants elected to continue treatment with THX-110 during an open extension phase and 7 of these completed the additional 24 weeks.

“THX-110 treatment led to an average improvement in tic symptoms of roughly 20%, or a 7-point decrease in the YGTSS total tic score. This improvement translates to a large effect size (d = 0.92) of improvement over time,” the investigators write.

More data needed

Commenting on the findings, Yolanda Holler-Managan, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics (neurology), Northwestern University, Chicago, cautioned that this was not a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group placebo-controlled study.

Instead, it was a clinical study to prove safety, tolerability, and dosing of the combination medication in adult patients with TS and “does not provide as much weight, since we do not have many studies on the efficacy of cannabinoids,” said Dr. Holler-Managan, who was not involved with the research.

She noted that the American Academy of Neurology’s 2019 practice guideline recommendations for treatment of tics in individuals with TS and tic disorders reported “limited evidence” that delta-9-THC is “possibly more likely than placebo to reduce tic severity in adults with TS, therefore we need more data.”

The current investigators agree. “Although these initial data are promising, future randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials are necessary to demonstrate efficacy of TXH-110 treatment,” they write.

They add that the psychoactive properties of cannabis-derived compounds make it challenging to design a properly blinded trial.

“Incorporation of physiologic biomarkers and objective measures of symptoms (e.g., videotaped tic counts by blinded raters) may be particularly important when examining these medications with psychoactive properties that may be prone to reporting bias,” the authors write.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant to Dr. Bloch from Therapix Biosciences. The state of Connecticut also provided resource support via the Abraham Ribicoff Research Facilities at the Connecticut Mental Health Center. Dr. Bloch serves on the scientific advisory boards of Therapix Biosciences, and he receives research support from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, NARSAD, Neurocrine Biosciences, NIH, and the Patterson Foundation. The other investigators and Dr. Holler-Managan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low depression scores may miss seniors with suicidal intent

Older adults may have a high degree of suicidal intent yet still have low scores on scales measuring psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, new research suggests.

In a cross-sectional cohort study of more than 800 adults who presented with self-harm to psychiatric EDs in Sweden, participants aged 65 years and older scored higher than younger and middle-aged adults on measures of suicidal intent.

However, only half of the older group fulfilled criteria for major depression, compared with three-quarters of both the middle-aged and young adult–aged groups.

“Suicidal older persons show a somewhat different clinical picture with relatively low levels of psychopathology but with high suicide intent compared to younger persons,” lead author Stefan Wiktorsson, PhD, University of Gothenburg (Sweden), said in an interview.

“It is therefore of importance for clinicians to carefully evaluate suicidal thinking in this age group. he said.

The findings were published online Aug. 9, 2021, in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Research by age groups ‘lacking’

“While there are large age differences in the prevalence of suicidal behavior, research studies that compare symptomatology and diagnostics in different age groups are lacking,” Dr. Wiktorsson said.

He and his colleagues “wanted to compare psychopathology in young, middle-aged, and older adults in order to increase knowledge about potential differences in symptomatology related to suicidal behavior over the life span.”

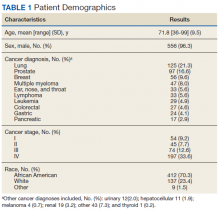

The researchers recruited patients aged 18 years and older who had sought or had been referred to emergency psychiatric services for self-harm at three psychiatric hospitals in Sweden between April 2012 and March 2016.

Among all patients, 821 fit inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. The researchers excluded participants who had engaged in nonsuicidal self-injury (NNSI), as determined on the basis of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The remaining 683 participants, who had attempted suicide, were included in the analysis.

The participants were then divided into the following three groups: older (n = 96; age, 65-97 years; mean age, 77.2 years; 57% women), middle-aged (n = 164; age, 45-64 years; mean age, 53.4 years; 57% women), and younger (n = 423; age, 18-44 years; mean age, 28.3 years; 64% women)

Mental health staff interviewed participants within 7 days of the index episode. They collected information about sociodemographics, health, and contact with health care professionals. They used the C-SSRS to identify characteristics of the suicide attempts, and they used the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) to evaluate circumstances surrounding the suicide attempt, such as active preparation.

Investigators also used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), the Suicide Assessment Scale (SUAS), and the Karolinska Affective and Borderline Symptoms Scale.

Greater disability, pain

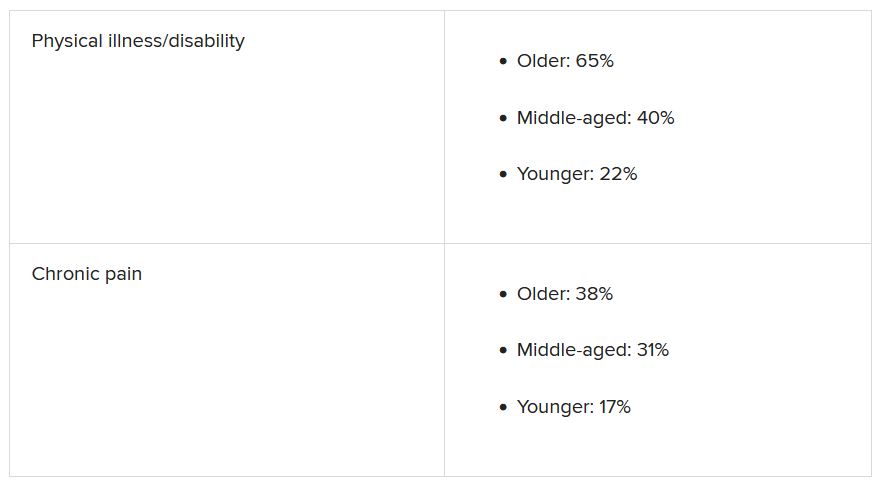

Of the older patients, 75% lived alone; 88% of the middle-aged and 48% of the younger participants lived alone. A higher proportion of older participants had severe physical illness/disability and severe chronic pain compared with younger participants (all comparisons, P < .001).

Older adults had less contact with psychiatric services, but they had more contact than the other age groups with primary care for mental health problems. Older adults were prescribed antidepressants at the time of the suicide attempt at a lower rate, compared with the middle-aged and younger groups (50% vs. 73% and 66%).

Slightly less than half (44%) of the older adults had a previous history of a suicide attempt – a proportion considerably lower than was reported by patients in the middle-aged and young adult groups (63% and 75%, respectively). Few older adults had a history of a previous NNSI (6% vs. 23% and 63%).

Three-quarters of older adults employed poisoning as the single method of suicide attempt at their index episode, compared with 67% and 59% of the middle-aged and younger groups.

Notably, only half of older adults (52%) met criteria for major depression, determined on the basis of the MINI, compared with three quarters of participants in the other groups (73% and 76%, respectively). Fewer members of the older group met criteria for other psychiatric conditions.

Clouded judgment

The mean total SUAS score was “considerably lower” in the older-adult group than in the other groups. This was also the case for the SUAS subscales for affect, bodily states, control, coping, and emotional reactivity.

Importantly, however, older adults scored higher than younger adults on the SIS total score and the subjective subscale, indicating a higher level of suicidal intent.

The mean SIS total score was 17.8 in the older group, 17.4 in the middle-aged group, and 15.9 in the younger group. The SIS subjective suicide intent score was 10.9 versus 10.6 and 9.4.

“While subjective suicidal intent was higher, compared to the young group, older adults were less likely to fulfill criteria for major depression and several other mental disorders and lower scores were observed on all symptom rating scales, compared to both middle-aged and younger adults,” the investigators wrote.

“Low levels of psychopathology may cloud the clinician’s assessment of the serious nature of suicide attempts in older patients,” they added.

‘Silent generation’

Commenting on the findings, Marnin Heisel, PhD, CPsych, associate professor, departments of psychiatry and of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of Western Ontario, London, said an important takeaway from the study is that, if health care professionals look only for depression or only consider suicide risk in individuals who present with depression, “they might miss older adults who are contemplating suicide or engaging in suicidal behavior.”

Dr. Heisel, who was not involved with the study, observed that older adults are sometimes called the “silent generation” because they often tend to downplay or underreport depressive symptoms, partially because of having been socialized to “keep things to themselves and not to air emotional laundry.”

He recommended that, when assessing potentially suicidal older adults, clinicians select tools specifically designed for use in this age group, particularly the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Dr. Heisel also recommended the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale–Revised Version.

“Beyond a specific scale, the question is to walk into a clinical encounter with a much broader viewpoint, understand who the client is, where they come from, their attitudes, life experience, and what in their experience is going on, their reason for coming to see someone and what they’re struggling with,” he said.

“What we’re seeing with this study is that standard clinical tools don’t necessarily identify some of these richer issues that might contribute to emotional pain, so sometimes the best way to go is a broader clinical interview with a humanistic perspective,” Dr. Heisel concluded.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the Swedish state, Stockholm County Council and Västerbotten County Council. The investigators and Dr. Heisel have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older adults may have a high degree of suicidal intent yet still have low scores on scales measuring psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, new research suggests.

In a cross-sectional cohort study of more than 800 adults who presented with self-harm to psychiatric EDs in Sweden, participants aged 65 years and older scored higher than younger and middle-aged adults on measures of suicidal intent.

However, only half of the older group fulfilled criteria for major depression, compared with three-quarters of both the middle-aged and young adult–aged groups.

“Suicidal older persons show a somewhat different clinical picture with relatively low levels of psychopathology but with high suicide intent compared to younger persons,” lead author Stefan Wiktorsson, PhD, University of Gothenburg (Sweden), said in an interview.

“It is therefore of importance for clinicians to carefully evaluate suicidal thinking in this age group. he said.

The findings were published online Aug. 9, 2021, in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Research by age groups ‘lacking’

“While there are large age differences in the prevalence of suicidal behavior, research studies that compare symptomatology and diagnostics in different age groups are lacking,” Dr. Wiktorsson said.

He and his colleagues “wanted to compare psychopathology in young, middle-aged, and older adults in order to increase knowledge about potential differences in symptomatology related to suicidal behavior over the life span.”

The researchers recruited patients aged 18 years and older who had sought or had been referred to emergency psychiatric services for self-harm at three psychiatric hospitals in Sweden between April 2012 and March 2016.

Among all patients, 821 fit inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. The researchers excluded participants who had engaged in nonsuicidal self-injury (NNSI), as determined on the basis of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The remaining 683 participants, who had attempted suicide, were included in the analysis.

The participants were then divided into the following three groups: older (n = 96; age, 65-97 years; mean age, 77.2 years; 57% women), middle-aged (n = 164; age, 45-64 years; mean age, 53.4 years; 57% women), and younger (n = 423; age, 18-44 years; mean age, 28.3 years; 64% women)

Mental health staff interviewed participants within 7 days of the index episode. They collected information about sociodemographics, health, and contact with health care professionals. They used the C-SSRS to identify characteristics of the suicide attempts, and they used the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) to evaluate circumstances surrounding the suicide attempt, such as active preparation.

Investigators also used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), the Suicide Assessment Scale (SUAS), and the Karolinska Affective and Borderline Symptoms Scale.

Greater disability, pain

Of the older patients, 75% lived alone; 88% of the middle-aged and 48% of the younger participants lived alone. A higher proportion of older participants had severe physical illness/disability and severe chronic pain compared with younger participants (all comparisons, P < .001).

Older adults had less contact with psychiatric services, but they had more contact than the other age groups with primary care for mental health problems. Older adults were prescribed antidepressants at the time of the suicide attempt at a lower rate, compared with the middle-aged and younger groups (50% vs. 73% and 66%).

Slightly less than half (44%) of the older adults had a previous history of a suicide attempt – a proportion considerably lower than was reported by patients in the middle-aged and young adult groups (63% and 75%, respectively). Few older adults had a history of a previous NNSI (6% vs. 23% and 63%).

Three-quarters of older adults employed poisoning as the single method of suicide attempt at their index episode, compared with 67% and 59% of the middle-aged and younger groups.

Notably, only half of older adults (52%) met criteria for major depression, determined on the basis of the MINI, compared with three quarters of participants in the other groups (73% and 76%, respectively). Fewer members of the older group met criteria for other psychiatric conditions.

Clouded judgment

The mean total SUAS score was “considerably lower” in the older-adult group than in the other groups. This was also the case for the SUAS subscales for affect, bodily states, control, coping, and emotional reactivity.

Importantly, however, older adults scored higher than younger adults on the SIS total score and the subjective subscale, indicating a higher level of suicidal intent.

The mean SIS total score was 17.8 in the older group, 17.4 in the middle-aged group, and 15.9 in the younger group. The SIS subjective suicide intent score was 10.9 versus 10.6 and 9.4.

“While subjective suicidal intent was higher, compared to the young group, older adults were less likely to fulfill criteria for major depression and several other mental disorders and lower scores were observed on all symptom rating scales, compared to both middle-aged and younger adults,” the investigators wrote.

“Low levels of psychopathology may cloud the clinician’s assessment of the serious nature of suicide attempts in older patients,” they added.

‘Silent generation’

Commenting on the findings, Marnin Heisel, PhD, CPsych, associate professor, departments of psychiatry and of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of Western Ontario, London, said an important takeaway from the study is that, if health care professionals look only for depression or only consider suicide risk in individuals who present with depression, “they might miss older adults who are contemplating suicide or engaging in suicidal behavior.”

Dr. Heisel, who was not involved with the study, observed that older adults are sometimes called the “silent generation” because they often tend to downplay or underreport depressive symptoms, partially because of having been socialized to “keep things to themselves and not to air emotional laundry.”

He recommended that, when assessing potentially suicidal older adults, clinicians select tools specifically designed for use in this age group, particularly the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Dr. Heisel also recommended the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale–Revised Version.

“Beyond a specific scale, the question is to walk into a clinical encounter with a much broader viewpoint, understand who the client is, where they come from, their attitudes, life experience, and what in their experience is going on, their reason for coming to see someone and what they’re struggling with,” he said.

“What we’re seeing with this study is that standard clinical tools don’t necessarily identify some of these richer issues that might contribute to emotional pain, so sometimes the best way to go is a broader clinical interview with a humanistic perspective,” Dr. Heisel concluded.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the Swedish state, Stockholm County Council and Västerbotten County Council. The investigators and Dr. Heisel have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older adults may have a high degree of suicidal intent yet still have low scores on scales measuring psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, new research suggests.

In a cross-sectional cohort study of more than 800 adults who presented with self-harm to psychiatric EDs in Sweden, participants aged 65 years and older scored higher than younger and middle-aged adults on measures of suicidal intent.

However, only half of the older group fulfilled criteria for major depression, compared with three-quarters of both the middle-aged and young adult–aged groups.

“Suicidal older persons show a somewhat different clinical picture with relatively low levels of psychopathology but with high suicide intent compared to younger persons,” lead author Stefan Wiktorsson, PhD, University of Gothenburg (Sweden), said in an interview.

“It is therefore of importance for clinicians to carefully evaluate suicidal thinking in this age group. he said.

The findings were published online Aug. 9, 2021, in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Research by age groups ‘lacking’

“While there are large age differences in the prevalence of suicidal behavior, research studies that compare symptomatology and diagnostics in different age groups are lacking,” Dr. Wiktorsson said.

He and his colleagues “wanted to compare psychopathology in young, middle-aged, and older adults in order to increase knowledge about potential differences in symptomatology related to suicidal behavior over the life span.”

The researchers recruited patients aged 18 years and older who had sought or had been referred to emergency psychiatric services for self-harm at three psychiatric hospitals in Sweden between April 2012 and March 2016.

Among all patients, 821 fit inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. The researchers excluded participants who had engaged in nonsuicidal self-injury (NNSI), as determined on the basis of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The remaining 683 participants, who had attempted suicide, were included in the analysis.

The participants were then divided into the following three groups: older (n = 96; age, 65-97 years; mean age, 77.2 years; 57% women), middle-aged (n = 164; age, 45-64 years; mean age, 53.4 years; 57% women), and younger (n = 423; age, 18-44 years; mean age, 28.3 years; 64% women)

Mental health staff interviewed participants within 7 days of the index episode. They collected information about sociodemographics, health, and contact with health care professionals. They used the C-SSRS to identify characteristics of the suicide attempts, and they used the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) to evaluate circumstances surrounding the suicide attempt, such as active preparation.

Investigators also used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), the Suicide Assessment Scale (SUAS), and the Karolinska Affective and Borderline Symptoms Scale.

Greater disability, pain

Of the older patients, 75% lived alone; 88% of the middle-aged and 48% of the younger participants lived alone. A higher proportion of older participants had severe physical illness/disability and severe chronic pain compared with younger participants (all comparisons, P < .001).

Older adults had less contact with psychiatric services, but they had more contact than the other age groups with primary care for mental health problems. Older adults were prescribed antidepressants at the time of the suicide attempt at a lower rate, compared with the middle-aged and younger groups (50% vs. 73% and 66%).

Slightly less than half (44%) of the older adults had a previous history of a suicide attempt – a proportion considerably lower than was reported by patients in the middle-aged and young adult groups (63% and 75%, respectively). Few older adults had a history of a previous NNSI (6% vs. 23% and 63%).

Three-quarters of older adults employed poisoning as the single method of suicide attempt at their index episode, compared with 67% and 59% of the middle-aged and younger groups.

Notably, only half of older adults (52%) met criteria for major depression, determined on the basis of the MINI, compared with three quarters of participants in the other groups (73% and 76%, respectively). Fewer members of the older group met criteria for other psychiatric conditions.

Clouded judgment

The mean total SUAS score was “considerably lower” in the older-adult group than in the other groups. This was also the case for the SUAS subscales for affect, bodily states, control, coping, and emotional reactivity.

Importantly, however, older adults scored higher than younger adults on the SIS total score and the subjective subscale, indicating a higher level of suicidal intent.

The mean SIS total score was 17.8 in the older group, 17.4 in the middle-aged group, and 15.9 in the younger group. The SIS subjective suicide intent score was 10.9 versus 10.6 and 9.4.

“While subjective suicidal intent was higher, compared to the young group, older adults were less likely to fulfill criteria for major depression and several other mental disorders and lower scores were observed on all symptom rating scales, compared to both middle-aged and younger adults,” the investigators wrote.

“Low levels of psychopathology may cloud the clinician’s assessment of the serious nature of suicide attempts in older patients,” they added.

‘Silent generation’

Commenting on the findings, Marnin Heisel, PhD, CPsych, associate professor, departments of psychiatry and of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of Western Ontario, London, said an important takeaway from the study is that, if health care professionals look only for depression or only consider suicide risk in individuals who present with depression, “they might miss older adults who are contemplating suicide or engaging in suicidal behavior.”

Dr. Heisel, who was not involved with the study, observed that older adults are sometimes called the “silent generation” because they often tend to downplay or underreport depressive symptoms, partially because of having been socialized to “keep things to themselves and not to air emotional laundry.”

He recommended that, when assessing potentially suicidal older adults, clinicians select tools specifically designed for use in this age group, particularly the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Dr. Heisel also recommended the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale–Revised Version.

“Beyond a specific scale, the question is to walk into a clinical encounter with a much broader viewpoint, understand who the client is, where they come from, their attitudes, life experience, and what in their experience is going on, their reason for coming to see someone and what they’re struggling with,” he said.

“What we’re seeing with this study is that standard clinical tools don’t necessarily identify some of these richer issues that might contribute to emotional pain, so sometimes the best way to go is a broader clinical interview with a humanistic perspective,” Dr. Heisel concluded.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the Swedish state, Stockholm County Council and Västerbotten County Council. The investigators and Dr. Heisel have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing sleep in the elderly

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2021

FDA OKs stimulation device for anxiety in depression

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the noninvasive BrainsWay Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (Deep TMS) System to include treatment of comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients with depression, the company has announced.

As reported by this news organization, the neurostimulation system has previously received FDA approval for treatment-resistant major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and smoking addiction.

In the August 18 announcement, BrainsWay reported that it has also received 510(k) clearance from the FDA to market its TMS system for the reduction of anxious depression symptoms.

“This clearance is confirmation of what many have believed anecdotally for years – that Deep TMS is a unique form of therapy that can address comorbid anxiety symptoms using the same depression treatment protocol,” Aron Tendler, MD, chief medical officer at BrainsWay, said in a press release.

‘Consistent, robust’ effect

, which included both randomized controlled trials and open-label studies.

“The data demonstrated a treatment effect that was consistent, robust, and clinically meaningful for decreasing anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from major depressive disorder [MDD],” the company said in its release.

Data from three of the randomized trials showed an effect size of 0.3 when compared with a sham device and an effect size of 0.9 when compared with medication. The overall, weighted, pooled effect size was 0.55.

The company noted that in more than 70 published studies with about 16,000 total participants, effect sizes have ranged from 0.2-0.37 for drug-based anxiety treatments.

“The expanded FDA labeling now allows BrainsWay to market its Deep TMS System for the treatment of depressive episodes and for decreasing anxiety symptoms for those who may exhibit comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from [MDD] and who failed to achieve satisfactory improvement from previous antidepressant medication treatment in the current episode,” the company said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the noninvasive BrainsWay Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (Deep TMS) System to include treatment of comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients with depression, the company has announced.

As reported by this news organization, the neurostimulation system has previously received FDA approval for treatment-resistant major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and smoking addiction.

In the August 18 announcement, BrainsWay reported that it has also received 510(k) clearance from the FDA to market its TMS system for the reduction of anxious depression symptoms.

“This clearance is confirmation of what many have believed anecdotally for years – that Deep TMS is a unique form of therapy that can address comorbid anxiety symptoms using the same depression treatment protocol,” Aron Tendler, MD, chief medical officer at BrainsWay, said in a press release.

‘Consistent, robust’ effect

, which included both randomized controlled trials and open-label studies.

“The data demonstrated a treatment effect that was consistent, robust, and clinically meaningful for decreasing anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from major depressive disorder [MDD],” the company said in its release.

Data from three of the randomized trials showed an effect size of 0.3 when compared with a sham device and an effect size of 0.9 when compared with medication. The overall, weighted, pooled effect size was 0.55.

The company noted that in more than 70 published studies with about 16,000 total participants, effect sizes have ranged from 0.2-0.37 for drug-based anxiety treatments.

“The expanded FDA labeling now allows BrainsWay to market its Deep TMS System for the treatment of depressive episodes and for decreasing anxiety symptoms for those who may exhibit comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from [MDD] and who failed to achieve satisfactory improvement from previous antidepressant medication treatment in the current episode,” the company said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the noninvasive BrainsWay Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (Deep TMS) System to include treatment of comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients with depression, the company has announced.

As reported by this news organization, the neurostimulation system has previously received FDA approval for treatment-resistant major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and smoking addiction.

In the August 18 announcement, BrainsWay reported that it has also received 510(k) clearance from the FDA to market its TMS system for the reduction of anxious depression symptoms.

“This clearance is confirmation of what many have believed anecdotally for years – that Deep TMS is a unique form of therapy that can address comorbid anxiety symptoms using the same depression treatment protocol,” Aron Tendler, MD, chief medical officer at BrainsWay, said in a press release.

‘Consistent, robust’ effect

, which included both randomized controlled trials and open-label studies.

“The data demonstrated a treatment effect that was consistent, robust, and clinically meaningful for decreasing anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from major depressive disorder [MDD],” the company said in its release.

Data from three of the randomized trials showed an effect size of 0.3 when compared with a sham device and an effect size of 0.9 when compared with medication. The overall, weighted, pooled effect size was 0.55.

The company noted that in more than 70 published studies with about 16,000 total participants, effect sizes have ranged from 0.2-0.37 for drug-based anxiety treatments.

“The expanded FDA labeling now allows BrainsWay to market its Deep TMS System for the treatment of depressive episodes and for decreasing anxiety symptoms for those who may exhibit comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from [MDD] and who failed to achieve satisfactory improvement from previous antidepressant medication treatment in the current episode,” the company said.