User login

MD-IQ only

Endometriosis and Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

What is the link between endometriosis and abnormal uterine bleeding?

Dr. Lager: This is an important question because when people first learn about endometriosis, common symptoms include pain with periods, pelvic pain, but not necessarily abnormal uterine bleeding. However, many patients do complain of abnormal uterine bleeding when presenting with endometriosis.

There are a couple of reasons why abnormal uterine bleeding is important to consider. Within the spectrum of endometriosis, vaginal endometriosis can contribute to abnormal vaginal bleeding, most commonly cyclic or postcoital. The bleeding could be rectal due to deeply infiltrative endometriosis, although gastrointestinal etiologies should be included in the differential. Another link is coexisting diagnoses such as fibroids, adenomyosis, and endometrial polyps. In fact, the rates for coexisting conditions with endometriosis can be high and vary from study to study.

As an example, some studies show rates between 7% and 11%, where adenomyosis coexists with endometriosis. Other studies look at magnetic resonance imaging for adenomyosis and deep infiltrative endometriosis and find that women younger than 36 years have rates as high as 90% for coexisting diagnoses, and 79% for all women, regardless of the diagnosis.

The overlap is high. When I think particularly about adenomyosis and endometriosis, in some ways, the conditions are along a spectrum where adenomyosis involves ectopic endometrial glands in the myometrium, whereas endometriosis involves ectopic tissue outside of the uterus, predominantly in reproductive organs, but can be anywhere outside of the endometrium. So, when I think about abnormal uterine bleeding particularly associated with dysmenorrhea or pelvic pain, this can often be included in the constellation of symptoms for endometriosis.

Furthermore, it is important to rule out other causes of abnormal uterine bleeding because they would potentially change the treatment.

What are the current treatment options for endometriosis and abnormal uterine bleeding?

Dr. Lager: Treatments for endometriosis are inclusive of any overlapping conditions and we use a multidisciplinary approach to address symptoms. Medical treatments include hormonal management, including birth control pills, etonogestrel implants (Nexplanon), levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, progestin-only pills, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, GnRH antagonists, and combination medications. Some medications do overlap and work for both, such as combined GnRH antagonists, estradiol, and progesterone.

Surgical management includes diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis. If there is another coexisting diagnosis that is structural in nature, such as endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, or fibroids, surgical management may include hysteroscopy, myomectomy, or hysterectomy as indicated. When we consider surgical and nonsurgical approaches, it is important to be clear on the etiology of abnormal uterine bleeding to appropriately counsel patients for what the surgery could entail.

Have you found there to be any age or racial disparities in endometriosis treatment?

Dr. Lager: One of the things that is important about endometriosis, and in medicine in general, is to really think about how we approach race as a social construct. In the past, medicine has included race as a risk factor for certain medical conditions. And physicians in training were taught to use these risk factors to determine a differential diagnosis. However, this strategy has limited us in understanding how historical and structural racism affected patient diagnosis and treatment.

If we think back to literature that was published in the 1950s or the 1970s, Dr. Meeks was one of the physicians who described a set of characteristics of patients with endometriosis. He commented that typical patients were women who were goal-oriented, had private insurance, and experienced delayed marriage, among other traits.

The problem with this characterization was that patients would then present with symptoms of endometriosis who did not fit the original phenotype as historically described and they would be misdiagnosed and thus treated incorrectly. This incorrect treatment further reinforced incorrect stereotypes of patient presentations. These misdiagnoses could lead to unfortunate consequences in their activities of daily living as well as reproductive outcomes. We do not have data on how many patients may have been misdiagnosed and treated for pelvic inflammatory disease because they were not White, did not have private insurance, or had children early. This is an example of areas where we need to recognize systemic racism and classism and work hard to simply do better for our patients.

Although misdiagnosing based on stereotypes has decreased over time, I still think that original thinking can certainly affect patient referrals. When we look at the data of patients who are diagnosed with endometriosis, we find a higher rate of White patients (17%) compared to Black (10.1%), Asian (11.3%), and Hispanic patients (7.4%). Ensuring that all of our patients are getting appropriate referrals and diagnosis should be a priority.

When we think about the timing to initial diagnosis, globally, we know that there is a delay in diagnosis anywhere from 7 to 12 years, and then on top of that, those social constructs decrease the rate of diagnosis for certain patient populations. Misdiagnosis based on social constructs is unacceptable and one aspect that I think is very important to point out.

In a more recent study of 12,000 patients in 2022, the rate of surgical complications associated with endometriosis surgery was higher in women who were Black, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Native American/American Indian than in women who were White. These groups have a much higher rate of complications and higher rates of laparotomy—an open procedure—versus laparoscopy. In younger women, there is a higher rate of oophorectomy at the time of surgery for endometriosis than in older women.

Are there any best practices you would like to share with your peers?

Dr. Lager: For patients with abnormal uterine bleeding, it is important to consider other diagnoses and not assume that abnormal bleeding is solely related to endometriosis, while considering deeply infiltrative endometriosis in the differential.

When patients do present with cyclical bleeding, especially, for example, after hysterectomy, it is important to examine for either vaginal or vaginal cuff endometriosis because there can be other reasons that patients will have abnormal uterine bleeding related to atypical endometriosis.

It is important to know the patient’s history and focus on each patient’s level of pain, how it affects their day-to-day activities, and how they are experiencing that pain.

We all should be working to improve our understanding of social history and systemic racism as best as we can and make sure all patients are getting the right care that they deserve.

What is the link between endometriosis and abnormal uterine bleeding?

Dr. Lager: This is an important question because when people first learn about endometriosis, common symptoms include pain with periods, pelvic pain, but not necessarily abnormal uterine bleeding. However, many patients do complain of abnormal uterine bleeding when presenting with endometriosis.

There are a couple of reasons why abnormal uterine bleeding is important to consider. Within the spectrum of endometriosis, vaginal endometriosis can contribute to abnormal vaginal bleeding, most commonly cyclic or postcoital. The bleeding could be rectal due to deeply infiltrative endometriosis, although gastrointestinal etiologies should be included in the differential. Another link is coexisting diagnoses such as fibroids, adenomyosis, and endometrial polyps. In fact, the rates for coexisting conditions with endometriosis can be high and vary from study to study.

As an example, some studies show rates between 7% and 11%, where adenomyosis coexists with endometriosis. Other studies look at magnetic resonance imaging for adenomyosis and deep infiltrative endometriosis and find that women younger than 36 years have rates as high as 90% for coexisting diagnoses, and 79% for all women, regardless of the diagnosis.

The overlap is high. When I think particularly about adenomyosis and endometriosis, in some ways, the conditions are along a spectrum where adenomyosis involves ectopic endometrial glands in the myometrium, whereas endometriosis involves ectopic tissue outside of the uterus, predominantly in reproductive organs, but can be anywhere outside of the endometrium. So, when I think about abnormal uterine bleeding particularly associated with dysmenorrhea or pelvic pain, this can often be included in the constellation of symptoms for endometriosis.

Furthermore, it is important to rule out other causes of abnormal uterine bleeding because they would potentially change the treatment.

What are the current treatment options for endometriosis and abnormal uterine bleeding?

Dr. Lager: Treatments for endometriosis are inclusive of any overlapping conditions and we use a multidisciplinary approach to address symptoms. Medical treatments include hormonal management, including birth control pills, etonogestrel implants (Nexplanon), levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, progestin-only pills, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, GnRH antagonists, and combination medications. Some medications do overlap and work for both, such as combined GnRH antagonists, estradiol, and progesterone.

Surgical management includes diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis. If there is another coexisting diagnosis that is structural in nature, such as endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, or fibroids, surgical management may include hysteroscopy, myomectomy, or hysterectomy as indicated. When we consider surgical and nonsurgical approaches, it is important to be clear on the etiology of abnormal uterine bleeding to appropriately counsel patients for what the surgery could entail.

Have you found there to be any age or racial disparities in endometriosis treatment?

Dr. Lager: One of the things that is important about endometriosis, and in medicine in general, is to really think about how we approach race as a social construct. In the past, medicine has included race as a risk factor for certain medical conditions. And physicians in training were taught to use these risk factors to determine a differential diagnosis. However, this strategy has limited us in understanding how historical and structural racism affected patient diagnosis and treatment.

If we think back to literature that was published in the 1950s or the 1970s, Dr. Meeks was one of the physicians who described a set of characteristics of patients with endometriosis. He commented that typical patients were women who were goal-oriented, had private insurance, and experienced delayed marriage, among other traits.

The problem with this characterization was that patients would then present with symptoms of endometriosis who did not fit the original phenotype as historically described and they would be misdiagnosed and thus treated incorrectly. This incorrect treatment further reinforced incorrect stereotypes of patient presentations. These misdiagnoses could lead to unfortunate consequences in their activities of daily living as well as reproductive outcomes. We do not have data on how many patients may have been misdiagnosed and treated for pelvic inflammatory disease because they were not White, did not have private insurance, or had children early. This is an example of areas where we need to recognize systemic racism and classism and work hard to simply do better for our patients.

Although misdiagnosing based on stereotypes has decreased over time, I still think that original thinking can certainly affect patient referrals. When we look at the data of patients who are diagnosed with endometriosis, we find a higher rate of White patients (17%) compared to Black (10.1%), Asian (11.3%), and Hispanic patients (7.4%). Ensuring that all of our patients are getting appropriate referrals and diagnosis should be a priority.

When we think about the timing to initial diagnosis, globally, we know that there is a delay in diagnosis anywhere from 7 to 12 years, and then on top of that, those social constructs decrease the rate of diagnosis for certain patient populations. Misdiagnosis based on social constructs is unacceptable and one aspect that I think is very important to point out.

In a more recent study of 12,000 patients in 2022, the rate of surgical complications associated with endometriosis surgery was higher in women who were Black, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Native American/American Indian than in women who were White. These groups have a much higher rate of complications and higher rates of laparotomy—an open procedure—versus laparoscopy. In younger women, there is a higher rate of oophorectomy at the time of surgery for endometriosis than in older women.

Are there any best practices you would like to share with your peers?

Dr. Lager: For patients with abnormal uterine bleeding, it is important to consider other diagnoses and not assume that abnormal bleeding is solely related to endometriosis, while considering deeply infiltrative endometriosis in the differential.

When patients do present with cyclical bleeding, especially, for example, after hysterectomy, it is important to examine for either vaginal or vaginal cuff endometriosis because there can be other reasons that patients will have abnormal uterine bleeding related to atypical endometriosis.

It is important to know the patient’s history and focus on each patient’s level of pain, how it affects their day-to-day activities, and how they are experiencing that pain.

We all should be working to improve our understanding of social history and systemic racism as best as we can and make sure all patients are getting the right care that they deserve.

What is the link between endometriosis and abnormal uterine bleeding?

Dr. Lager: This is an important question because when people first learn about endometriosis, common symptoms include pain with periods, pelvic pain, but not necessarily abnormal uterine bleeding. However, many patients do complain of abnormal uterine bleeding when presenting with endometriosis.

There are a couple of reasons why abnormal uterine bleeding is important to consider. Within the spectrum of endometriosis, vaginal endometriosis can contribute to abnormal vaginal bleeding, most commonly cyclic or postcoital. The bleeding could be rectal due to deeply infiltrative endometriosis, although gastrointestinal etiologies should be included in the differential. Another link is coexisting diagnoses such as fibroids, adenomyosis, and endometrial polyps. In fact, the rates for coexisting conditions with endometriosis can be high and vary from study to study.

As an example, some studies show rates between 7% and 11%, where adenomyosis coexists with endometriosis. Other studies look at magnetic resonance imaging for adenomyosis and deep infiltrative endometriosis and find that women younger than 36 years have rates as high as 90% for coexisting diagnoses, and 79% for all women, regardless of the diagnosis.

The overlap is high. When I think particularly about adenomyosis and endometriosis, in some ways, the conditions are along a spectrum where adenomyosis involves ectopic endometrial glands in the myometrium, whereas endometriosis involves ectopic tissue outside of the uterus, predominantly in reproductive organs, but can be anywhere outside of the endometrium. So, when I think about abnormal uterine bleeding particularly associated with dysmenorrhea or pelvic pain, this can often be included in the constellation of symptoms for endometriosis.

Furthermore, it is important to rule out other causes of abnormal uterine bleeding because they would potentially change the treatment.

What are the current treatment options for endometriosis and abnormal uterine bleeding?

Dr. Lager: Treatments for endometriosis are inclusive of any overlapping conditions and we use a multidisciplinary approach to address symptoms. Medical treatments include hormonal management, including birth control pills, etonogestrel implants (Nexplanon), levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, progestin-only pills, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, GnRH antagonists, and combination medications. Some medications do overlap and work for both, such as combined GnRH antagonists, estradiol, and progesterone.

Surgical management includes diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis. If there is another coexisting diagnosis that is structural in nature, such as endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, or fibroids, surgical management may include hysteroscopy, myomectomy, or hysterectomy as indicated. When we consider surgical and nonsurgical approaches, it is important to be clear on the etiology of abnormal uterine bleeding to appropriately counsel patients for what the surgery could entail.

Have you found there to be any age or racial disparities in endometriosis treatment?

Dr. Lager: One of the things that is important about endometriosis, and in medicine in general, is to really think about how we approach race as a social construct. In the past, medicine has included race as a risk factor for certain medical conditions. And physicians in training were taught to use these risk factors to determine a differential diagnosis. However, this strategy has limited us in understanding how historical and structural racism affected patient diagnosis and treatment.

If we think back to literature that was published in the 1950s or the 1970s, Dr. Meeks was one of the physicians who described a set of characteristics of patients with endometriosis. He commented that typical patients were women who were goal-oriented, had private insurance, and experienced delayed marriage, among other traits.

The problem with this characterization was that patients would then present with symptoms of endometriosis who did not fit the original phenotype as historically described and they would be misdiagnosed and thus treated incorrectly. This incorrect treatment further reinforced incorrect stereotypes of patient presentations. These misdiagnoses could lead to unfortunate consequences in their activities of daily living as well as reproductive outcomes. We do not have data on how many patients may have been misdiagnosed and treated for pelvic inflammatory disease because they were not White, did not have private insurance, or had children early. This is an example of areas where we need to recognize systemic racism and classism and work hard to simply do better for our patients.

Although misdiagnosing based on stereotypes has decreased over time, I still think that original thinking can certainly affect patient referrals. When we look at the data of patients who are diagnosed with endometriosis, we find a higher rate of White patients (17%) compared to Black (10.1%), Asian (11.3%), and Hispanic patients (7.4%). Ensuring that all of our patients are getting appropriate referrals and diagnosis should be a priority.

When we think about the timing to initial diagnosis, globally, we know that there is a delay in diagnosis anywhere from 7 to 12 years, and then on top of that, those social constructs decrease the rate of diagnosis for certain patient populations. Misdiagnosis based on social constructs is unacceptable and one aspect that I think is very important to point out.

In a more recent study of 12,000 patients in 2022, the rate of surgical complications associated with endometriosis surgery was higher in women who were Black, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Native American/American Indian than in women who were White. These groups have a much higher rate of complications and higher rates of laparotomy—an open procedure—versus laparoscopy. In younger women, there is a higher rate of oophorectomy at the time of surgery for endometriosis than in older women.

Are there any best practices you would like to share with your peers?

Dr. Lager: For patients with abnormal uterine bleeding, it is important to consider other diagnoses and not assume that abnormal bleeding is solely related to endometriosis, while considering deeply infiltrative endometriosis in the differential.

When patients do present with cyclical bleeding, especially, for example, after hysterectomy, it is important to examine for either vaginal or vaginal cuff endometriosis because there can be other reasons that patients will have abnormal uterine bleeding related to atypical endometriosis.

It is important to know the patient’s history and focus on each patient’s level of pain, how it affects their day-to-day activities, and how they are experiencing that pain.

We all should be working to improve our understanding of social history and systemic racism as best as we can and make sure all patients are getting the right care that they deserve.

New guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management released

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CANNABIS AND CANNABINOID RESEARCH

Prepare for endometriosis excision surgery with a multidisciplinary approach

Introduction: The preoperative evaluation for endometriosis – more than meets the eye

It is well known that it often takes 6-10 years for endometriosis to be diagnosed in patients who have the disease, depending on where the patient lives. I certainly am not surprised. During my residency at Parkland Memorial Hospital, if a patient had chronic pelvic pain and no fibroids, her diagnosis was usually pelvic inflammatory disease. Later, during my fellowship in reproductive endocrinology at the University of Pennsylvania, the diagnosis became endometriosis.

As I gained more interest and expertise in the treatment of endometriosis, I became aware of several articles concluding that if a woman sought treatment for chronic pelvic pain with an internist, the diagnosis would be irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); with a urologist, it would be interstitial cystitis; and with a gynecologist, endometriosis. Moreover, there is an increased propensity for IBS and IC in patients with endometriosis. There also is an increased risk of small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), as noted by our guest author for this latest installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Iris Orbuch, MD.

Like our guest author, I have also noted increased risk of pelvic floor myalgia. Dr. Orbuch clearly outlines why this occurs. In fact, we can now understand why many patients have multiple pelvic pain–inducing issues compounding their pain secondary to endometriosis and leading to remodeling of the central nervous system. Therefore, it certainly makes sense to follow Dr. Orbuch’s recommendation for a multidisciplinary pre- and postsurgical approach “to downregulate the pain generators.”

Dr. Orbuch is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Los Angeles who specializes in the treatment of patients diagnosed with endometriosis. Dr. Orbuch serves on the Board of Directors of the Foundation of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists and has served as the chair of the AAGL’s Special Interest Group on Endometriosis and Reproductive Surgery. She is the coauthor of the book “Beating Endo – How to Reclaim Your Life From Endometriosis” (New York: HarperCollins; 2019). The book is written for patients but addresses many issues discussed in this installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller, MD, FACOG, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology, department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago. He has no conflicts of interest to report.

Patients with endometriosis and the all-too-often decade-long diagnostic delay have a variety of coexisting conditions that are pain generators – from painful bladder syndrome and pelvic floor dysfunction to a small intestine bacterial system that is significantly upregulated and sensitized.

For optimal surgical outcomes, and to help our patients recover from years of this inflammatory, systemic disease, we must treat our patients holistically and work to downregulate their pain as much as possible before excision surgery. I work with patients a few months prior to surgery, often for 4-5 months, during which time they not only see me for informative follow-ups, but also pelvic floor physical therapists, gastroenterologists, mental health professionals, integrative nutritionists, and physiatrists or pain specialists, depending on their needs.1

By identifying coexisting conditions in an initial consult and employing a presurgical multidisciplinary approach to downregulate the pain generators, my patients recover well from excision surgery, with greater and faster relief from pain, compared with those using standard approaches, and with little to no use of opioids.

At a minimum, given the unfortunate time constraints and productivity demands of working within health systems – and considering that surgeries are often scheduled a couple of months out – the surgeon could ensure that patients are engaged in at least 6-8 weeks of pelvic floor physical therapy before surgery to sufficiently lengthen the pelvic muscles and loosen surrounding fascia.

Short, tight pelvic floor muscles are almost universal in patients with delayed diagnosis of endometriosis and are significant generators of pain.

Appreciating sequelae of diagnostic delay

After my fellowship in advanced laparoscopic and pelvic surgery with Harry Reich, MD, and C. Y. Liu, MD, pioneers of endometriosis excision surgery, and as I did my residency in the early 2000s, I noticed puzzlement in the literature about why some patients still had lasting pain after thorough excision.

I didn’t doubt the efficacy of excision. It is the cornerstone of treatment, and at least one randomized double-blind trial2 and a systematic review and meta-analysis3 have demonstrated its superior efficacy over ablation in symptom reduction. What I did doubt was any presumption that surgery alone was enough. I knew there was more to healing when a disease process wreaks havoc on the body for more than a decade and that there were other generators of pain in addition to the endometriosis implants themselves.

As I began to focus on endometriosis in my own surgical practice, I strove to detect and treat endometriosis in teens. But in those patients with longstanding disease, I recognized patterns and began to more fully appreciate the systemic sequelae of endometriosis.

To cope with dysmenorrhea, patients curl up and assume a fetal position, tensing the abdominal muscles, inner thigh muscles, and pelvic floor muscles. Over time, these muscles come to maintain a short, tight, and painful state. (Hence the need for physical therapy to undo this decade-long pattern.)

Endometriosis implants on or near the gastrointestinal tract tug on fascia and muscles and commonly cause constipation, leading women to further overwork the pelvic floor muscles. In the case of diarrhea-predominant dysfunction, our patients squeeze pelvic floor muscles to prevent leakage. And in the case of urinary urgency, they squeeze muscles to release urine that isn’t really there.

As the chronic inflammation of the disease grows, and as pain worsens, the patient is increasingly in sympathetic overdrive (also known as ”fight or flight”), as opposed to a parasympathetic state (also known as “rest and digest”). The bowel’s motility slows, allowing the bacteria of the small intestine to grow beyond what is normal, leading to SIBO, a condition increasingly recognized by gastroenterologists and others that can impede nutrient absorption and cause bloat and pain and exacerbate constipation and diarrhea.

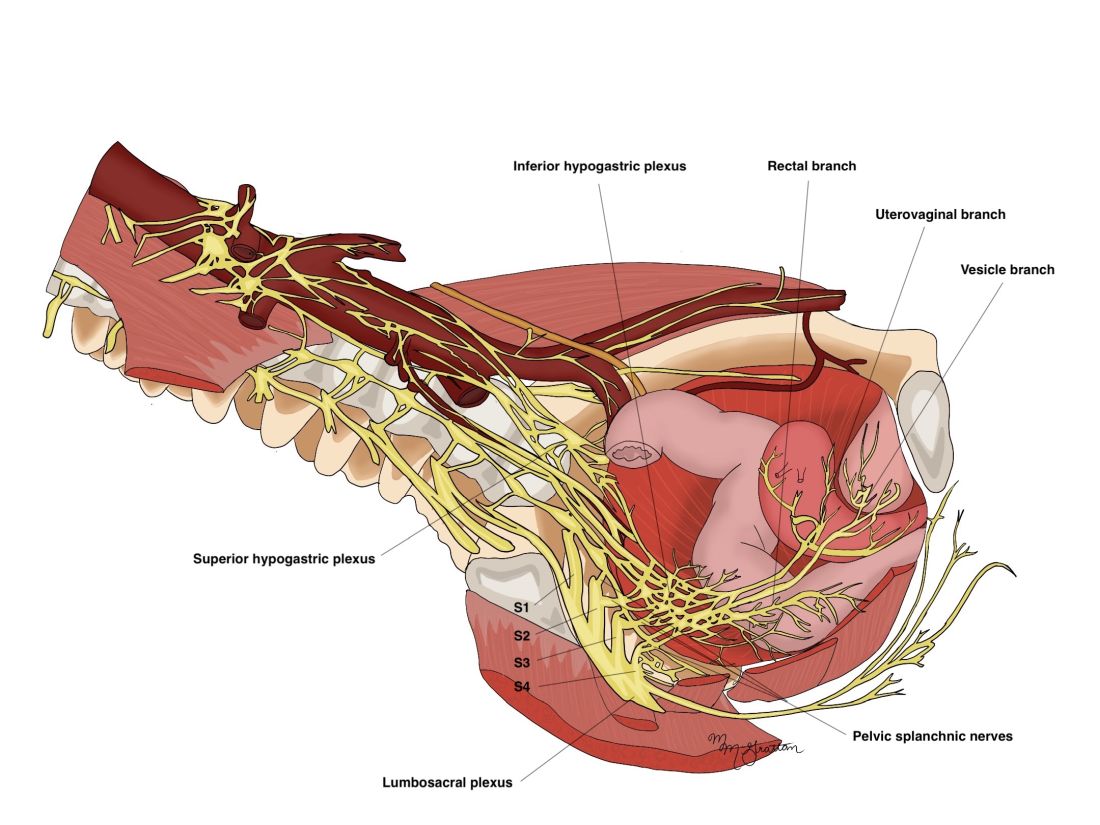

Key to my conceptualization of pain was a review published in 2011 by Pam Stratton, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, and Karen J. Berkley, PhD, then of Florida State University, on chronic pain and endometriosis.4 They detailed how endometriotic lesions can develop their own nerve supply that interacts directly and in a two-way fashion with the CNS – and how the lesions can engage the nervous system in ways that create comorbid conditions and pain that becomes “independent of the disease itself.”

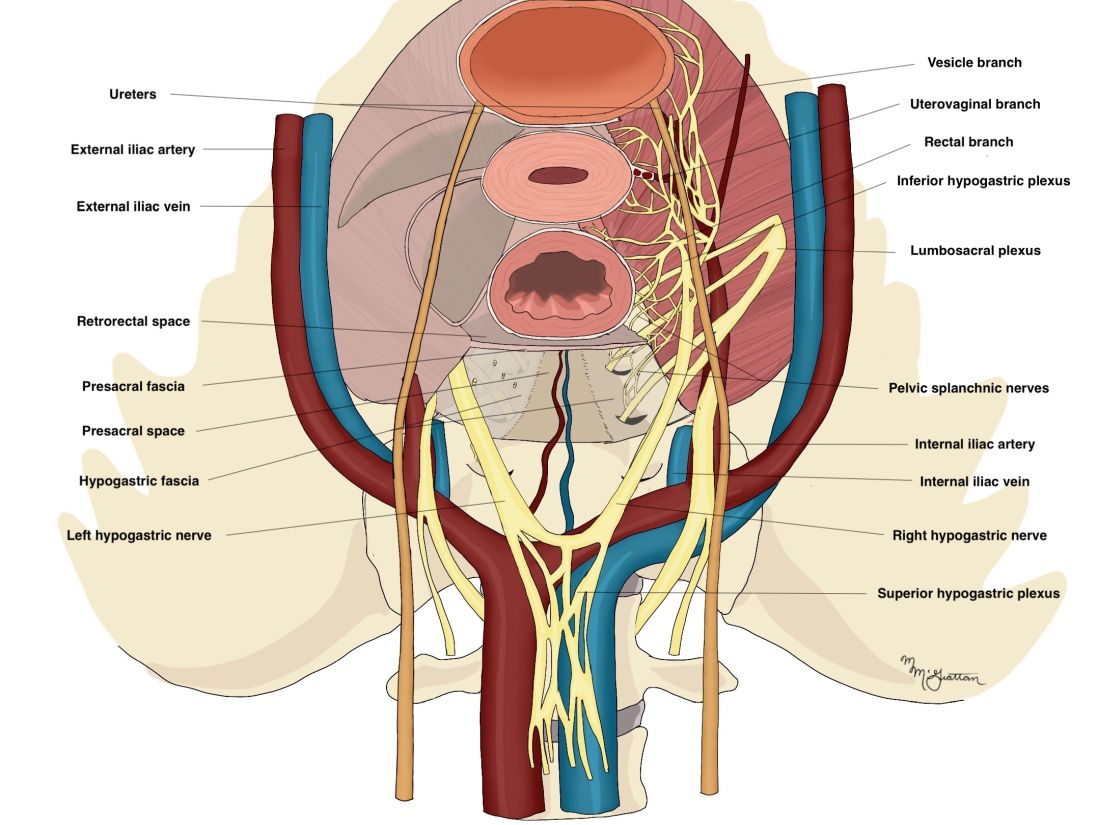

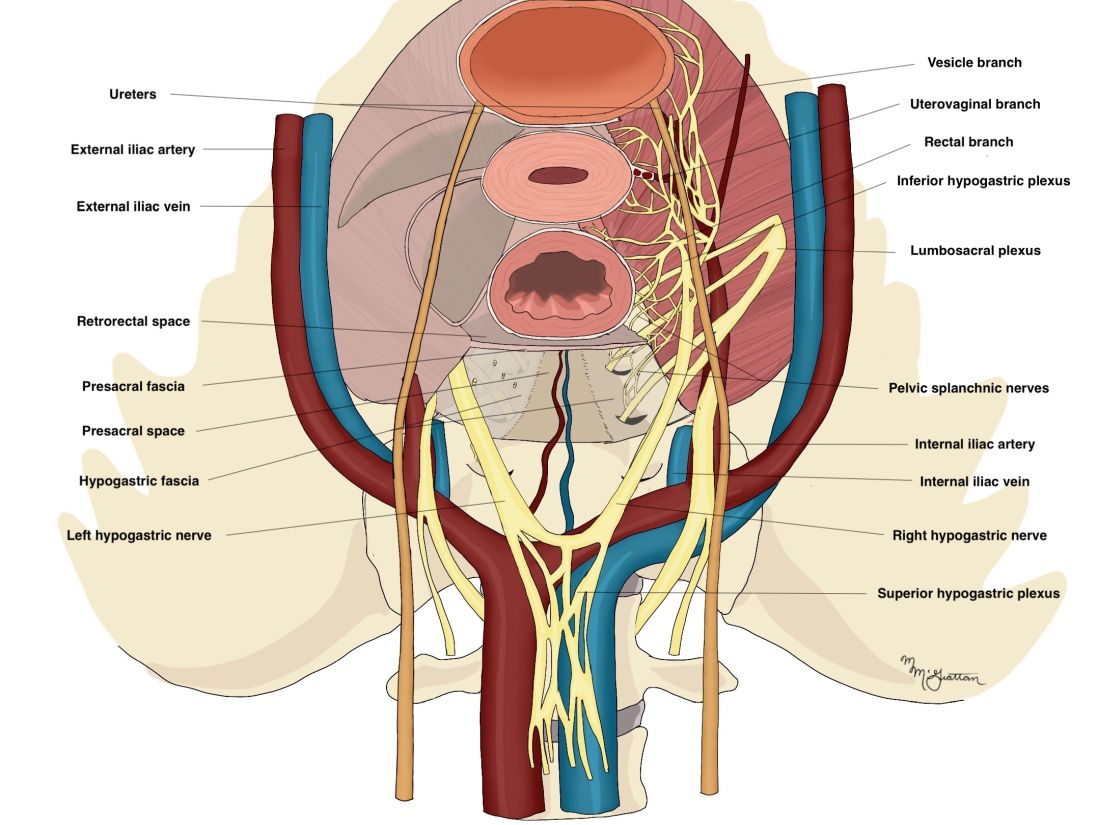

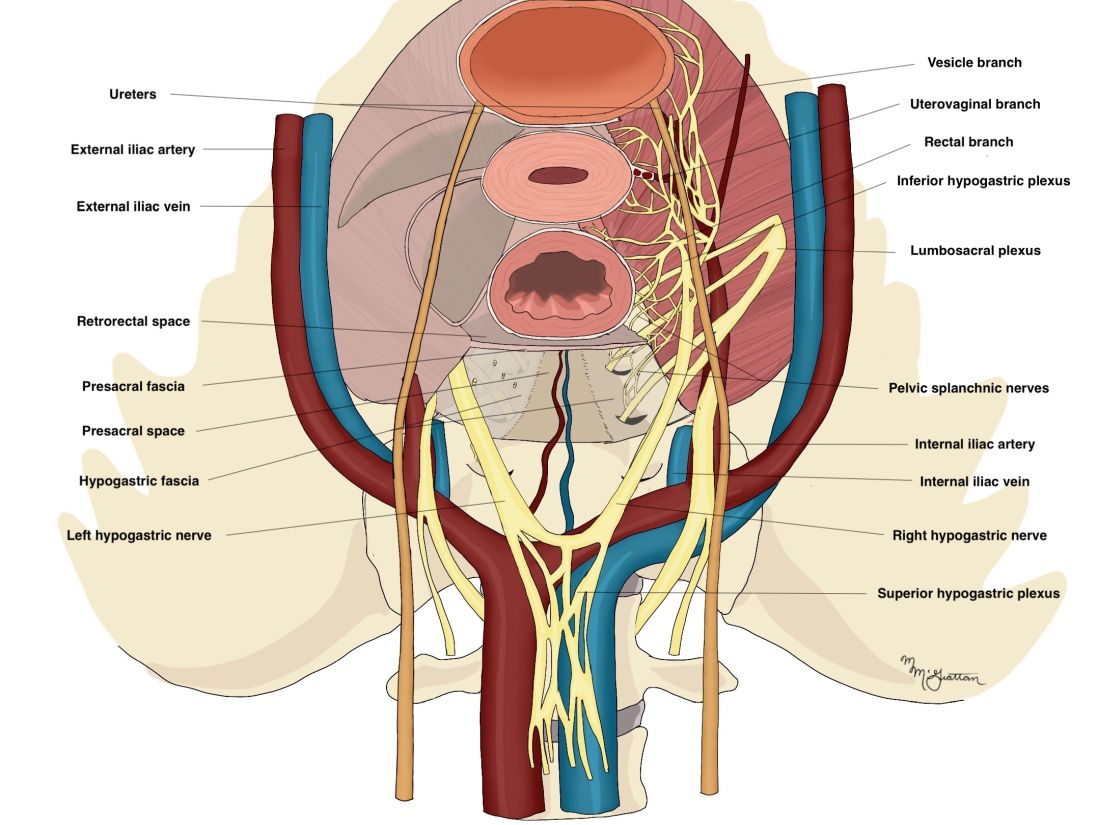

Sensitized peripheral nerve fibers innervating a deeply infiltrating lesion on the left uterosacral ligament, for instance, can sensitize neurons in the spinal sacral segment. Branches of these nerve fibers can extend to other segments of the spinal cord, and, once sensitized themselves, turn on neurons in these other segments. There is a resultant remodeling of the central nervous system, in essence, and what is called “remote central sensitization.” The CNS becomes independent from peripheral neural processes.

I now explain to both patients and physicians that those who have had endometriosis for years have had an enduring “hand on the stove,” with a persistent signal to the CNS. Tight muscles are a hand on the stove, painful bladder syndrome is another hand on the stove, and SIBO is yet another. So are anxiety and depression.

The CNS becomes so upregulated and overloaded that messages branch out through the spinal cord to other available pathways and to other organs, muscles, and nerves. The CNS also starts firing on its own – and once it becomes its own pain generator, taking one hand off the stove (for instance, excising implants) while leaving multiple other hands on the hot stove won’t remove all pain. We must downregulate the CNS more broadly.

As I began addressing pain generators and instigators of CNS sensitization – and waiting for excision surgery until the CNS had sufficiently cooled – I saw that my patients had a better chance of more significant and lasting pain relief.

Pearls for a multimodal approach

My initial physical exam includes an assessment of the pelvic floor for overly tight musculature. An abdominal exam will usually reveal whether there is asymmetry of the abdominal wall muscles, which typically informs me of the likelihood of tightness and pulling on either side of the pelvic anatomy. On the internal exam, then, the pelvic floor muscles can be palpated and assessed. These findings will guide my referrals and my discussions with patients about the value of pelvic floor physical therapy. The cervix should be in the midline of the vagina – equidistant from the left and right vaginal fornices. If the cervix is pulled away from this midline, and a palpation of a thickened uterosacral ligament reproduces pain, endometriosis is 90% likely.

Patients who report significant “burning” pain that’s suggestive of neuropathic pain should be referred to a physical medicine rehabilitation physician or a pain specialist who can help downregulate their CNS. And patients who have symptoms of depression, anxiety disorders (including obsessive-compulsive disorder), or posttraumatic stress disorder should be referred to pain therapists, psychologists, or other mental health professionals, preferably well before surgery. I will also often discuss mindfulness practices and give my patients “meditation challenges” to achieve during the presurgical phase.

Additional points of emphasis about a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach include:

Advanced pelvic floor therapy: Therapists with specialized training in pelvic health and manual therapy utilize a range of techniques and modalities to release tension in affected muscles, fascia, nerves, and bone, and in doing so, they help to downregulate the CNS. Myofascial release, myofascial trigger point release, neural mobilization, and visceral mobilization are among these techniques. In addition to using manual therapy, many of these therapists may also employ neuromuscular reeducation and other techniques that will be helpful for the longer term.

It is important to identify physical therapists who have training in this approach; women with endometriosis often have a history of treatment by physical therapists whose focus is on incontinence and muscle strengthening (that is, Kegel exercises), which is the opposite of what endometriosis patients need.

Treating SIBO: Symptoms commonly associated with SIBO often overlap with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) – namely constipation, diarrhea (or both), and bloating. Indeed, many patients with undiagnosed endometriosis have been diagnosed with IBS. I send every patient who has one of these symptoms for SIBO breath testing, which utilizes carbohydrate substrates (glucose or lactulose) and measures hydrogen and/or methane in the breath.

SIBO is typically treated with rifampin, which stays in the small bowel and will not negatively affect beneficial bacteria, with or without neomycin. Gastroenterologists with more integrative practices also consider the use of herbals in addition to – or instead of – antibiotics. It can sometimes take months or a couple of years to correct SIBO, depending on how long the patient has been affected, but with presurgical diagnosis and a start on treatment, we can remove or at least tone down another instigator of CNS sensitization.

I estimate that 80% of my patients have tested positive for SIBO. Notably, in a testament to the systemic nature of endometriosis, a study published in 2009 of 355 women undergoing operative laparoscopy for suspected endometriosis found that 90% had gastrointestinal symptoms, but only 7.6% of the vast majority whose endometriosis was confirmed were found to have endometrial implants on the bowel itself.5

Addressing bladder issues: I routinely administer the PUF (Pain, Urgency, Frequency) questionnaire as part of my intake package and follow it up with conversation. For just about every patient with painful bladder syndrome, pelvic floor physical therapy in combination with a low-acid, low-potassium diet will work effectively together to reduce symptoms and pain. The IC Network offers a helpful food list, and patients can be counseled to choose foods that are also anti-inflammatory. When referrals to a urologist for bladder instillations are possible, these can be helpful as well.

Our communication with patients

Our patients need to have their symptoms and pain validated and to understand why we’re recommending these measures before surgery. Some education is necessary. Few patients will go to an integrative nutritionist, for example, if we just write a referral without explaining how years of inflammation and disruption in the gut can affect the whole body – including mental health – and that it can be corrected over time.

Also necessary is an appreciation of the fact that patients with delayed diagnoses have lived with gastrointestinal and other symptoms and patterns for so long – and often have mothers whose endometriosis caused similar symptoms – that some of their own experiences can seem almost “normal.” A patient whose mother had bowel movements every 7 days may think that 4-5 day intervals are acceptable, for instance. This means we have to carefully consider how we ask our questions.

I always ask my patients as we’re going into surgery, what percentage better are you? I’ve long aimed for at least 30% improvement, but most of the time, with pelvic floor therapy and as many other pain-generator–focused measures as possible, we’re getting them 70% better.

Excision surgery will remove the inflammation that has helped fuel the SIBO and other coconditions. Then, everything done to prepare the body must continue for some time. Certain practices, such as eating an anti-inflammatory diet, should be lifelong.

One day, it is hoped, a pediatrician or other physician will suspect endometriosis early on. The patient will see the surgeon within several months of the onset of pain, and we won’t need to unravel layers of pain generation and CNS upregulation before operating. But until this happens and we shorten the diagnostic delay, we must consider the benefits of presurgical preparation.

References

1. Orbuch I, Stein A. Beating Endo: How to Reclaim Your Life From Endometriosis. (New York: HarperCollins, 2019).

2. Healey M et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):999-1004.

3. Pundir J et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(5):747-56.

4. Stratton P, Berkley KJ. Hum Repro Update. 2011;17(3):327-46.

5. Maroun P et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(4):411-4.

Dr. Orbuch is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Los Angeles who specializes in endometriosis. She has no conflicts of interest to report.

Introduction: The preoperative evaluation for endometriosis – more than meets the eye

It is well known that it often takes 6-10 years for endometriosis to be diagnosed in patients who have the disease, depending on where the patient lives. I certainly am not surprised. During my residency at Parkland Memorial Hospital, if a patient had chronic pelvic pain and no fibroids, her diagnosis was usually pelvic inflammatory disease. Later, during my fellowship in reproductive endocrinology at the University of Pennsylvania, the diagnosis became endometriosis.

As I gained more interest and expertise in the treatment of endometriosis, I became aware of several articles concluding that if a woman sought treatment for chronic pelvic pain with an internist, the diagnosis would be irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); with a urologist, it would be interstitial cystitis; and with a gynecologist, endometriosis. Moreover, there is an increased propensity for IBS and IC in patients with endometriosis. There also is an increased risk of small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), as noted by our guest author for this latest installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Iris Orbuch, MD.

Like our guest author, I have also noted increased risk of pelvic floor myalgia. Dr. Orbuch clearly outlines why this occurs. In fact, we can now understand why many patients have multiple pelvic pain–inducing issues compounding their pain secondary to endometriosis and leading to remodeling of the central nervous system. Therefore, it certainly makes sense to follow Dr. Orbuch’s recommendation for a multidisciplinary pre- and postsurgical approach “to downregulate the pain generators.”

Dr. Orbuch is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Los Angeles who specializes in the treatment of patients diagnosed with endometriosis. Dr. Orbuch serves on the Board of Directors of the Foundation of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists and has served as the chair of the AAGL’s Special Interest Group on Endometriosis and Reproductive Surgery. She is the coauthor of the book “Beating Endo – How to Reclaim Your Life From Endometriosis” (New York: HarperCollins; 2019). The book is written for patients but addresses many issues discussed in this installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller, MD, FACOG, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology, department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago. He has no conflicts of interest to report.

Patients with endometriosis and the all-too-often decade-long diagnostic delay have a variety of coexisting conditions that are pain generators – from painful bladder syndrome and pelvic floor dysfunction to a small intestine bacterial system that is significantly upregulated and sensitized.

For optimal surgical outcomes, and to help our patients recover from years of this inflammatory, systemic disease, we must treat our patients holistically and work to downregulate their pain as much as possible before excision surgery. I work with patients a few months prior to surgery, often for 4-5 months, during which time they not only see me for informative follow-ups, but also pelvic floor physical therapists, gastroenterologists, mental health professionals, integrative nutritionists, and physiatrists or pain specialists, depending on their needs.1

By identifying coexisting conditions in an initial consult and employing a presurgical multidisciplinary approach to downregulate the pain generators, my patients recover well from excision surgery, with greater and faster relief from pain, compared with those using standard approaches, and with little to no use of opioids.

At a minimum, given the unfortunate time constraints and productivity demands of working within health systems – and considering that surgeries are often scheduled a couple of months out – the surgeon could ensure that patients are engaged in at least 6-8 weeks of pelvic floor physical therapy before surgery to sufficiently lengthen the pelvic muscles and loosen surrounding fascia.

Short, tight pelvic floor muscles are almost universal in patients with delayed diagnosis of endometriosis and are significant generators of pain.

Appreciating sequelae of diagnostic delay

After my fellowship in advanced laparoscopic and pelvic surgery with Harry Reich, MD, and C. Y. Liu, MD, pioneers of endometriosis excision surgery, and as I did my residency in the early 2000s, I noticed puzzlement in the literature about why some patients still had lasting pain after thorough excision.

I didn’t doubt the efficacy of excision. It is the cornerstone of treatment, and at least one randomized double-blind trial2 and a systematic review and meta-analysis3 have demonstrated its superior efficacy over ablation in symptom reduction. What I did doubt was any presumption that surgery alone was enough. I knew there was more to healing when a disease process wreaks havoc on the body for more than a decade and that there were other generators of pain in addition to the endometriosis implants themselves.

As I began to focus on endometriosis in my own surgical practice, I strove to detect and treat endometriosis in teens. But in those patients with longstanding disease, I recognized patterns and began to more fully appreciate the systemic sequelae of endometriosis.

To cope with dysmenorrhea, patients curl up and assume a fetal position, tensing the abdominal muscles, inner thigh muscles, and pelvic floor muscles. Over time, these muscles come to maintain a short, tight, and painful state. (Hence the need for physical therapy to undo this decade-long pattern.)

Endometriosis implants on or near the gastrointestinal tract tug on fascia and muscles and commonly cause constipation, leading women to further overwork the pelvic floor muscles. In the case of diarrhea-predominant dysfunction, our patients squeeze pelvic floor muscles to prevent leakage. And in the case of urinary urgency, they squeeze muscles to release urine that isn’t really there.

As the chronic inflammation of the disease grows, and as pain worsens, the patient is increasingly in sympathetic overdrive (also known as ”fight or flight”), as opposed to a parasympathetic state (also known as “rest and digest”). The bowel’s motility slows, allowing the bacteria of the small intestine to grow beyond what is normal, leading to SIBO, a condition increasingly recognized by gastroenterologists and others that can impede nutrient absorption and cause bloat and pain and exacerbate constipation and diarrhea.

Key to my conceptualization of pain was a review published in 2011 by Pam Stratton, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, and Karen J. Berkley, PhD, then of Florida State University, on chronic pain and endometriosis.4 They detailed how endometriotic lesions can develop their own nerve supply that interacts directly and in a two-way fashion with the CNS – and how the lesions can engage the nervous system in ways that create comorbid conditions and pain that becomes “independent of the disease itself.”

Sensitized peripheral nerve fibers innervating a deeply infiltrating lesion on the left uterosacral ligament, for instance, can sensitize neurons in the spinal sacral segment. Branches of these nerve fibers can extend to other segments of the spinal cord, and, once sensitized themselves, turn on neurons in these other segments. There is a resultant remodeling of the central nervous system, in essence, and what is called “remote central sensitization.” The CNS becomes independent from peripheral neural processes.

I now explain to both patients and physicians that those who have had endometriosis for years have had an enduring “hand on the stove,” with a persistent signal to the CNS. Tight muscles are a hand on the stove, painful bladder syndrome is another hand on the stove, and SIBO is yet another. So are anxiety and depression.

The CNS becomes so upregulated and overloaded that messages branch out through the spinal cord to other available pathways and to other organs, muscles, and nerves. The CNS also starts firing on its own – and once it becomes its own pain generator, taking one hand off the stove (for instance, excising implants) while leaving multiple other hands on the hot stove won’t remove all pain. We must downregulate the CNS more broadly.

As I began addressing pain generators and instigators of CNS sensitization – and waiting for excision surgery until the CNS had sufficiently cooled – I saw that my patients had a better chance of more significant and lasting pain relief.

Pearls for a multimodal approach

My initial physical exam includes an assessment of the pelvic floor for overly tight musculature. An abdominal exam will usually reveal whether there is asymmetry of the abdominal wall muscles, which typically informs me of the likelihood of tightness and pulling on either side of the pelvic anatomy. On the internal exam, then, the pelvic floor muscles can be palpated and assessed. These findings will guide my referrals and my discussions with patients about the value of pelvic floor physical therapy. The cervix should be in the midline of the vagina – equidistant from the left and right vaginal fornices. If the cervix is pulled away from this midline, and a palpation of a thickened uterosacral ligament reproduces pain, endometriosis is 90% likely.

Patients who report significant “burning” pain that’s suggestive of neuropathic pain should be referred to a physical medicine rehabilitation physician or a pain specialist who can help downregulate their CNS. And patients who have symptoms of depression, anxiety disorders (including obsessive-compulsive disorder), or posttraumatic stress disorder should be referred to pain therapists, psychologists, or other mental health professionals, preferably well before surgery. I will also often discuss mindfulness practices and give my patients “meditation challenges” to achieve during the presurgical phase.

Additional points of emphasis about a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach include:

Advanced pelvic floor therapy: Therapists with specialized training in pelvic health and manual therapy utilize a range of techniques and modalities to release tension in affected muscles, fascia, nerves, and bone, and in doing so, they help to downregulate the CNS. Myofascial release, myofascial trigger point release, neural mobilization, and visceral mobilization are among these techniques. In addition to using manual therapy, many of these therapists may also employ neuromuscular reeducation and other techniques that will be helpful for the longer term.

It is important to identify physical therapists who have training in this approach; women with endometriosis often have a history of treatment by physical therapists whose focus is on incontinence and muscle strengthening (that is, Kegel exercises), which is the opposite of what endometriosis patients need.

Treating SIBO: Symptoms commonly associated with SIBO often overlap with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) – namely constipation, diarrhea (or both), and bloating. Indeed, many patients with undiagnosed endometriosis have been diagnosed with IBS. I send every patient who has one of these symptoms for SIBO breath testing, which utilizes carbohydrate substrates (glucose or lactulose) and measures hydrogen and/or methane in the breath.

SIBO is typically treated with rifampin, which stays in the small bowel and will not negatively affect beneficial bacteria, with or without neomycin. Gastroenterologists with more integrative practices also consider the use of herbals in addition to – or instead of – antibiotics. It can sometimes take months or a couple of years to correct SIBO, depending on how long the patient has been affected, but with presurgical diagnosis and a start on treatment, we can remove or at least tone down another instigator of CNS sensitization.

I estimate that 80% of my patients have tested positive for SIBO. Notably, in a testament to the systemic nature of endometriosis, a study published in 2009 of 355 women undergoing operative laparoscopy for suspected endometriosis found that 90% had gastrointestinal symptoms, but only 7.6% of the vast majority whose endometriosis was confirmed were found to have endometrial implants on the bowel itself.5

Addressing bladder issues: I routinely administer the PUF (Pain, Urgency, Frequency) questionnaire as part of my intake package and follow it up with conversation. For just about every patient with painful bladder syndrome, pelvic floor physical therapy in combination with a low-acid, low-potassium diet will work effectively together to reduce symptoms and pain. The IC Network offers a helpful food list, and patients can be counseled to choose foods that are also anti-inflammatory. When referrals to a urologist for bladder instillations are possible, these can be helpful as well.

Our communication with patients

Our patients need to have their symptoms and pain validated and to understand why we’re recommending these measures before surgery. Some education is necessary. Few patients will go to an integrative nutritionist, for example, if we just write a referral without explaining how years of inflammation and disruption in the gut can affect the whole body – including mental health – and that it can be corrected over time.

Also necessary is an appreciation of the fact that patients with delayed diagnoses have lived with gastrointestinal and other symptoms and patterns for so long – and often have mothers whose endometriosis caused similar symptoms – that some of their own experiences can seem almost “normal.” A patient whose mother had bowel movements every 7 days may think that 4-5 day intervals are acceptable, for instance. This means we have to carefully consider how we ask our questions.

I always ask my patients as we’re going into surgery, what percentage better are you? I’ve long aimed for at least 30% improvement, but most of the time, with pelvic floor therapy and as many other pain-generator–focused measures as possible, we’re getting them 70% better.

Excision surgery will remove the inflammation that has helped fuel the SIBO and other coconditions. Then, everything done to prepare the body must continue for some time. Certain practices, such as eating an anti-inflammatory diet, should be lifelong.

One day, it is hoped, a pediatrician or other physician will suspect endometriosis early on. The patient will see the surgeon within several months of the onset of pain, and we won’t need to unravel layers of pain generation and CNS upregulation before operating. But until this happens and we shorten the diagnostic delay, we must consider the benefits of presurgical preparation.

References

1. Orbuch I, Stein A. Beating Endo: How to Reclaim Your Life From Endometriosis. (New York: HarperCollins, 2019).

2. Healey M et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):999-1004.

3. Pundir J et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(5):747-56.

4. Stratton P, Berkley KJ. Hum Repro Update. 2011;17(3):327-46.

5. Maroun P et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(4):411-4.

Dr. Orbuch is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Los Angeles who specializes in endometriosis. She has no conflicts of interest to report.

Introduction: The preoperative evaluation for endometriosis – more than meets the eye

It is well known that it often takes 6-10 years for endometriosis to be diagnosed in patients who have the disease, depending on where the patient lives. I certainly am not surprised. During my residency at Parkland Memorial Hospital, if a patient had chronic pelvic pain and no fibroids, her diagnosis was usually pelvic inflammatory disease. Later, during my fellowship in reproductive endocrinology at the University of Pennsylvania, the diagnosis became endometriosis.

As I gained more interest and expertise in the treatment of endometriosis, I became aware of several articles concluding that if a woman sought treatment for chronic pelvic pain with an internist, the diagnosis would be irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); with a urologist, it would be interstitial cystitis; and with a gynecologist, endometriosis. Moreover, there is an increased propensity for IBS and IC in patients with endometriosis. There also is an increased risk of small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), as noted by our guest author for this latest installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Iris Orbuch, MD.

Like our guest author, I have also noted increased risk of pelvic floor myalgia. Dr. Orbuch clearly outlines why this occurs. In fact, we can now understand why many patients have multiple pelvic pain–inducing issues compounding their pain secondary to endometriosis and leading to remodeling of the central nervous system. Therefore, it certainly makes sense to follow Dr. Orbuch’s recommendation for a multidisciplinary pre- and postsurgical approach “to downregulate the pain generators.”

Dr. Orbuch is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Los Angeles who specializes in the treatment of patients diagnosed with endometriosis. Dr. Orbuch serves on the Board of Directors of the Foundation of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists and has served as the chair of the AAGL’s Special Interest Group on Endometriosis and Reproductive Surgery. She is the coauthor of the book “Beating Endo – How to Reclaim Your Life From Endometriosis” (New York: HarperCollins; 2019). The book is written for patients but addresses many issues discussed in this installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller, MD, FACOG, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology, department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago. He has no conflicts of interest to report.

Patients with endometriosis and the all-too-often decade-long diagnostic delay have a variety of coexisting conditions that are pain generators – from painful bladder syndrome and pelvic floor dysfunction to a small intestine bacterial system that is significantly upregulated and sensitized.

For optimal surgical outcomes, and to help our patients recover from years of this inflammatory, systemic disease, we must treat our patients holistically and work to downregulate their pain as much as possible before excision surgery. I work with patients a few months prior to surgery, often for 4-5 months, during which time they not only see me for informative follow-ups, but also pelvic floor physical therapists, gastroenterologists, mental health professionals, integrative nutritionists, and physiatrists or pain specialists, depending on their needs.1

By identifying coexisting conditions in an initial consult and employing a presurgical multidisciplinary approach to downregulate the pain generators, my patients recover well from excision surgery, with greater and faster relief from pain, compared with those using standard approaches, and with little to no use of opioids.

At a minimum, given the unfortunate time constraints and productivity demands of working within health systems – and considering that surgeries are often scheduled a couple of months out – the surgeon could ensure that patients are engaged in at least 6-8 weeks of pelvic floor physical therapy before surgery to sufficiently lengthen the pelvic muscles and loosen surrounding fascia.

Short, tight pelvic floor muscles are almost universal in patients with delayed diagnosis of endometriosis and are significant generators of pain.

Appreciating sequelae of diagnostic delay

After my fellowship in advanced laparoscopic and pelvic surgery with Harry Reich, MD, and C. Y. Liu, MD, pioneers of endometriosis excision surgery, and as I did my residency in the early 2000s, I noticed puzzlement in the literature about why some patients still had lasting pain after thorough excision.

I didn’t doubt the efficacy of excision. It is the cornerstone of treatment, and at least one randomized double-blind trial2 and a systematic review and meta-analysis3 have demonstrated its superior efficacy over ablation in symptom reduction. What I did doubt was any presumption that surgery alone was enough. I knew there was more to healing when a disease process wreaks havoc on the body for more than a decade and that there were other generators of pain in addition to the endometriosis implants themselves.

As I began to focus on endometriosis in my own surgical practice, I strove to detect and treat endometriosis in teens. But in those patients with longstanding disease, I recognized patterns and began to more fully appreciate the systemic sequelae of endometriosis.

To cope with dysmenorrhea, patients curl up and assume a fetal position, tensing the abdominal muscles, inner thigh muscles, and pelvic floor muscles. Over time, these muscles come to maintain a short, tight, and painful state. (Hence the need for physical therapy to undo this decade-long pattern.)

Endometriosis implants on or near the gastrointestinal tract tug on fascia and muscles and commonly cause constipation, leading women to further overwork the pelvic floor muscles. In the case of diarrhea-predominant dysfunction, our patients squeeze pelvic floor muscles to prevent leakage. And in the case of urinary urgency, they squeeze muscles to release urine that isn’t really there.

As the chronic inflammation of the disease grows, and as pain worsens, the patient is increasingly in sympathetic overdrive (also known as ”fight or flight”), as opposed to a parasympathetic state (also known as “rest and digest”). The bowel’s motility slows, allowing the bacteria of the small intestine to grow beyond what is normal, leading to SIBO, a condition increasingly recognized by gastroenterologists and others that can impede nutrient absorption and cause bloat and pain and exacerbate constipation and diarrhea.

Key to my conceptualization of pain was a review published in 2011 by Pam Stratton, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, and Karen J. Berkley, PhD, then of Florida State University, on chronic pain and endometriosis.4 They detailed how endometriotic lesions can develop their own nerve supply that interacts directly and in a two-way fashion with the CNS – and how the lesions can engage the nervous system in ways that create comorbid conditions and pain that becomes “independent of the disease itself.”

Sensitized peripheral nerve fibers innervating a deeply infiltrating lesion on the left uterosacral ligament, for instance, can sensitize neurons in the spinal sacral segment. Branches of these nerve fibers can extend to other segments of the spinal cord, and, once sensitized themselves, turn on neurons in these other segments. There is a resultant remodeling of the central nervous system, in essence, and what is called “remote central sensitization.” The CNS becomes independent from peripheral neural processes.

I now explain to both patients and physicians that those who have had endometriosis for years have had an enduring “hand on the stove,” with a persistent signal to the CNS. Tight muscles are a hand on the stove, painful bladder syndrome is another hand on the stove, and SIBO is yet another. So are anxiety and depression.

The CNS becomes so upregulated and overloaded that messages branch out through the spinal cord to other available pathways and to other organs, muscles, and nerves. The CNS also starts firing on its own – and once it becomes its own pain generator, taking one hand off the stove (for instance, excising implants) while leaving multiple other hands on the hot stove won’t remove all pain. We must downregulate the CNS more broadly.

As I began addressing pain generators and instigators of CNS sensitization – and waiting for excision surgery until the CNS had sufficiently cooled – I saw that my patients had a better chance of more significant and lasting pain relief.

Pearls for a multimodal approach

My initial physical exam includes an assessment of the pelvic floor for overly tight musculature. An abdominal exam will usually reveal whether there is asymmetry of the abdominal wall muscles, which typically informs me of the likelihood of tightness and pulling on either side of the pelvic anatomy. On the internal exam, then, the pelvic floor muscles can be palpated and assessed. These findings will guide my referrals and my discussions with patients about the value of pelvic floor physical therapy. The cervix should be in the midline of the vagina – equidistant from the left and right vaginal fornices. If the cervix is pulled away from this midline, and a palpation of a thickened uterosacral ligament reproduces pain, endometriosis is 90% likely.