User login

Transillumination for Improved Diagnosis of Digital Myxoid Cysts

Practice Gap

Myxoid cysts are among the most common space-occupying lesions involving the nail unit. Their etiology has not been fully elucidated, but these cysts likely form due to leakage of synovial fluid following trauma or chronic wear and tear. They are highly associated with osteoarthritis and typically are found in close proximity to the distal interphalangeal joints.1 Myxoid cysts often extend into the eponychium, where mechanical stress on the nail matrix may lead to nail dystrophy, most commonly resulting in a longitudinal groove in the nail plate (Figure, A). The presence of multiple myxoid cysts is not uncommon. Differentiation of this lesion from other nodules of the digits, including epidermoid cysts, acquired digital fibrokeratomas, and giant cell tendon sheath tumors often is challenging without a biopsy.

Technique

The normal nail unit transmits light to some extent, and masses may be identified by how easily they transmit light relative to the adjacent skin. Solid tumors of the nail unit, such as acquired digital fibrokeratomas and giant cell tendon sheath tumors, will not transmit light, while myxoid cysts transmit light easily. A dermatoscope can be used to project light from the dorsal digit through the nail unit. The area occupied by the myxoid cyst will appear bright compared to the surrounding skin (Figure, B). Drainage of the lesion using an 18-gauge needle yielded a clear jellylike fluid that was consistent with a myxoid cyst. This technique aids in localizing and characterizing the myxoid cyst for treatment or drainage. Physician assessment of transillumination has been shown to demonstrate clinical accuracy and high intraobserver reliability in differentiating between cystic and solid tumors.2

Practice Implications

Transillumination is a valuable technique that may aid dermatologists in both the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of myxoid cysts. Location is important to consider when choosing a treatment option. Although lower recurrence rates are achieved with nail surgery, permanent nail dystrophy is likely when cysts are in close proximity to the nail matrix.3 When multiple cysts are present, only the largest may be apparent. Transillumination can guide the physician in achieving more accurate and thorough drainage of the cyst contents, negating the need for more costly imaging modalities. Dermatologists may utilize transillumination as a rapid and economical diagnostic method for space-occupying lesions involving the nail unit.

- Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:364-369.

- Erne HC, Gardner TR, Strauch RJ. Transillumination of hand tumors: a cadaver study to evaluate accuracy and intraobserver reliability. Hand (N Y). 2011;6:390-393.

- Fritz GR, Stern PJ, Dickey M. Complications following mucous cyst excision. J Hand Surg Br. 1997;22:222-225.

Practice Gap

Myxoid cysts are among the most common space-occupying lesions involving the nail unit. Their etiology has not been fully elucidated, but these cysts likely form due to leakage of synovial fluid following trauma or chronic wear and tear. They are highly associated with osteoarthritis and typically are found in close proximity to the distal interphalangeal joints.1 Myxoid cysts often extend into the eponychium, where mechanical stress on the nail matrix may lead to nail dystrophy, most commonly resulting in a longitudinal groove in the nail plate (Figure, A). The presence of multiple myxoid cysts is not uncommon. Differentiation of this lesion from other nodules of the digits, including epidermoid cysts, acquired digital fibrokeratomas, and giant cell tendon sheath tumors often is challenging without a biopsy.

Technique

The normal nail unit transmits light to some extent, and masses may be identified by how easily they transmit light relative to the adjacent skin. Solid tumors of the nail unit, such as acquired digital fibrokeratomas and giant cell tendon sheath tumors, will not transmit light, while myxoid cysts transmit light easily. A dermatoscope can be used to project light from the dorsal digit through the nail unit. The area occupied by the myxoid cyst will appear bright compared to the surrounding skin (Figure, B). Drainage of the lesion using an 18-gauge needle yielded a clear jellylike fluid that was consistent with a myxoid cyst. This technique aids in localizing and characterizing the myxoid cyst for treatment or drainage. Physician assessment of transillumination has been shown to demonstrate clinical accuracy and high intraobserver reliability in differentiating between cystic and solid tumors.2

Practice Implications

Transillumination is a valuable technique that may aid dermatologists in both the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of myxoid cysts. Location is important to consider when choosing a treatment option. Although lower recurrence rates are achieved with nail surgery, permanent nail dystrophy is likely when cysts are in close proximity to the nail matrix.3 When multiple cysts are present, only the largest may be apparent. Transillumination can guide the physician in achieving more accurate and thorough drainage of the cyst contents, negating the need for more costly imaging modalities. Dermatologists may utilize transillumination as a rapid and economical diagnostic method for space-occupying lesions involving the nail unit.

Practice Gap

Myxoid cysts are among the most common space-occupying lesions involving the nail unit. Their etiology has not been fully elucidated, but these cysts likely form due to leakage of synovial fluid following trauma or chronic wear and tear. They are highly associated with osteoarthritis and typically are found in close proximity to the distal interphalangeal joints.1 Myxoid cysts often extend into the eponychium, where mechanical stress on the nail matrix may lead to nail dystrophy, most commonly resulting in a longitudinal groove in the nail plate (Figure, A). The presence of multiple myxoid cysts is not uncommon. Differentiation of this lesion from other nodules of the digits, including epidermoid cysts, acquired digital fibrokeratomas, and giant cell tendon sheath tumors often is challenging without a biopsy.

Technique

The normal nail unit transmits light to some extent, and masses may be identified by how easily they transmit light relative to the adjacent skin. Solid tumors of the nail unit, such as acquired digital fibrokeratomas and giant cell tendon sheath tumors, will not transmit light, while myxoid cysts transmit light easily. A dermatoscope can be used to project light from the dorsal digit through the nail unit. The area occupied by the myxoid cyst will appear bright compared to the surrounding skin (Figure, B). Drainage of the lesion using an 18-gauge needle yielded a clear jellylike fluid that was consistent with a myxoid cyst. This technique aids in localizing and characterizing the myxoid cyst for treatment or drainage. Physician assessment of transillumination has been shown to demonstrate clinical accuracy and high intraobserver reliability in differentiating between cystic and solid tumors.2

Practice Implications

Transillumination is a valuable technique that may aid dermatologists in both the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of myxoid cysts. Location is important to consider when choosing a treatment option. Although lower recurrence rates are achieved with nail surgery, permanent nail dystrophy is likely when cysts are in close proximity to the nail matrix.3 When multiple cysts are present, only the largest may be apparent. Transillumination can guide the physician in achieving more accurate and thorough drainage of the cyst contents, negating the need for more costly imaging modalities. Dermatologists may utilize transillumination as a rapid and economical diagnostic method for space-occupying lesions involving the nail unit.

- Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:364-369.

- Erne HC, Gardner TR, Strauch RJ. Transillumination of hand tumors: a cadaver study to evaluate accuracy and intraobserver reliability. Hand (N Y). 2011;6:390-393.

- Fritz GR, Stern PJ, Dickey M. Complications following mucous cyst excision. J Hand Surg Br. 1997;22:222-225.

- Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:364-369.

- Erne HC, Gardner TR, Strauch RJ. Transillumination of hand tumors: a cadaver study to evaluate accuracy and intraobserver reliability. Hand (N Y). 2011;6:390-393.

- Fritz GR, Stern PJ, Dickey M. Complications following mucous cyst excision. J Hand Surg Br. 1997;22:222-225.

Infographic: Applications for the Ketogenic Diet in Dermatology

This infographic is available in the PDF above.

This infographic is available in the PDF above.

This infographic is available in the PDF above.

Infographic: Inpatient Dermatology Consultations

Infographic: Monitoring Acne Patients on Oral Therapy Survey Results and Practice Recommendations

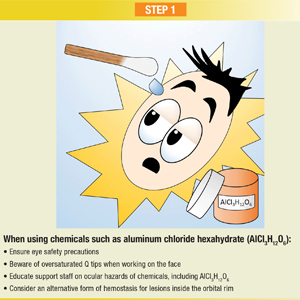

Infographic: Step-by-Step Guide to Managing Ocular Chemical Burns

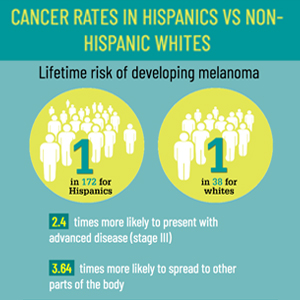

Infographic: Skin Cancer Stats in Hispanic Patients

Debunking Acne Myths: Patients Need Photoprotection, Not a Tan

Myth: Getting a Tan Helps Improve Acne

Acne has a multifaceted impact on patients, and facial acne in particular can impair self-image, psychological well-being, and ability to develop relationships. Patients cope with the clinical presentation of the disease in various ways, such as wearing makeup to cover blemishes, changing their hair color or diet, or getting regular facials. A common misconception is that a tan will help resolve acne.

A 2014 study on the burden of adult female acne (N=208) found that 5.3% of patients go to tanning salons or lay out in the sun to cope with their acne and 17% use self-tanning products to make their acne less visible. Many patients (40%) also believed that sunscreen exacerbates acne. Furthermore, a study of adolescents in Stockholm reported that those with acne, eczema, or psoriasis used sunbeds more than others without skin diseases.

The risk of developing skin cancer from sun exposure or UV light has been well established, and there is no evidence that UV light helps improve acne. A 2015 review of the literature on tanning bed use and phototherapy associated with treatment of conditions such as acne reported that experimental trials have been conducted for various light source therapies (eg, blue light, red-blue light, photodynamic therapy); however, there is no direct evidence for UV light.

In fact, acne patients should be counseled on the importance of photoprotection. Many acne therapies leave patients predisposed to UV damage, and UV damage generates free radical formation, which has been implicated in acne flares.

Expert Commentary

Often I hear from patients they feel tanning helps improve their acne. I tell them there is no evidence this is at all true. Just like cream makeup can camouflage acne, so too can tanning. But, trying to hide your blemishes does not actually help nor treat them. And moreover, tanning is so dangerous for potential skin cancer later in life.

—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

Boldeman C, Beitner H, Jansson B, et al. Sunbed use in relation to phenotype, erythema, sunscreen use and skin diseases. a questionnaire survey among Swedish adolescents. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:712-726.

Bowe WP, Kircik LH. The importance of photoprotection and moisturization in treating acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S89-S94.

Radack KP, Farhangian ME, Anderson KL, et al. A review of the use of tanning beds as a dermatological treatment. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:37-51.

Tanghetti EA, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:22-30.

Myth: Getting a Tan Helps Improve Acne

Acne has a multifaceted impact on patients, and facial acne in particular can impair self-image, psychological well-being, and ability to develop relationships. Patients cope with the clinical presentation of the disease in various ways, such as wearing makeup to cover blemishes, changing their hair color or diet, or getting regular facials. A common misconception is that a tan will help resolve acne.

A 2014 study on the burden of adult female acne (N=208) found that 5.3% of patients go to tanning salons or lay out in the sun to cope with their acne and 17% use self-tanning products to make their acne less visible. Many patients (40%) also believed that sunscreen exacerbates acne. Furthermore, a study of adolescents in Stockholm reported that those with acne, eczema, or psoriasis used sunbeds more than others without skin diseases.

The risk of developing skin cancer from sun exposure or UV light has been well established, and there is no evidence that UV light helps improve acne. A 2015 review of the literature on tanning bed use and phototherapy associated with treatment of conditions such as acne reported that experimental trials have been conducted for various light source therapies (eg, blue light, red-blue light, photodynamic therapy); however, there is no direct evidence for UV light.

In fact, acne patients should be counseled on the importance of photoprotection. Many acne therapies leave patients predisposed to UV damage, and UV damage generates free radical formation, which has been implicated in acne flares.

Expert Commentary

Often I hear from patients they feel tanning helps improve their acne. I tell them there is no evidence this is at all true. Just like cream makeup can camouflage acne, so too can tanning. But, trying to hide your blemishes does not actually help nor treat them. And moreover, tanning is so dangerous for potential skin cancer later in life.

—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

Myth: Getting a Tan Helps Improve Acne

Acne has a multifaceted impact on patients, and facial acne in particular can impair self-image, psychological well-being, and ability to develop relationships. Patients cope with the clinical presentation of the disease in various ways, such as wearing makeup to cover blemishes, changing their hair color or diet, or getting regular facials. A common misconception is that a tan will help resolve acne.

A 2014 study on the burden of adult female acne (N=208) found that 5.3% of patients go to tanning salons or lay out in the sun to cope with their acne and 17% use self-tanning products to make their acne less visible. Many patients (40%) also believed that sunscreen exacerbates acne. Furthermore, a study of adolescents in Stockholm reported that those with acne, eczema, or psoriasis used sunbeds more than others without skin diseases.

The risk of developing skin cancer from sun exposure or UV light has been well established, and there is no evidence that UV light helps improve acne. A 2015 review of the literature on tanning bed use and phototherapy associated with treatment of conditions such as acne reported that experimental trials have been conducted for various light source therapies (eg, blue light, red-blue light, photodynamic therapy); however, there is no direct evidence for UV light.

In fact, acne patients should be counseled on the importance of photoprotection. Many acne therapies leave patients predisposed to UV damage, and UV damage generates free radical formation, which has been implicated in acne flares.

Expert Commentary

Often I hear from patients they feel tanning helps improve their acne. I tell them there is no evidence this is at all true. Just like cream makeup can camouflage acne, so too can tanning. But, trying to hide your blemishes does not actually help nor treat them. And moreover, tanning is so dangerous for potential skin cancer later in life.

—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

Boldeman C, Beitner H, Jansson B, et al. Sunbed use in relation to phenotype, erythema, sunscreen use and skin diseases. a questionnaire survey among Swedish adolescents. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:712-726.

Bowe WP, Kircik LH. The importance of photoprotection and moisturization in treating acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S89-S94.

Radack KP, Farhangian ME, Anderson KL, et al. A review of the use of tanning beds as a dermatological treatment. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:37-51.

Tanghetti EA, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:22-30.

Boldeman C, Beitner H, Jansson B, et al. Sunbed use in relation to phenotype, erythema, sunscreen use and skin diseases. a questionnaire survey among Swedish adolescents. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:712-726.

Bowe WP, Kircik LH. The importance of photoprotection and moisturization in treating acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S89-S94.

Radack KP, Farhangian ME, Anderson KL, et al. A review of the use of tanning beds as a dermatological treatment. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:37-51.

Tanghetti EA, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, et al. Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:22-30.

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Psoriasis Is More Than Skin Deep

Myth: Psoriasis Is Only a Skin Problem

Psoriasis is predominantly regarded as a skin disease because of the outward clinical presentation of the condition. However, psoriasis is a disorder of the immune system and its damage may be more than skin deep.

Psoriasis commonly presents on the skin and nails, but a growing body of evidence has suggested that psoriasis is associated with systemic comorbidities. Up to 25% of psoriasis patients develop joint inflammation, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) may precede skin involvement. There also is a risk for cardiovascular complications. Because of the emotional distress caused by psoriasis, patients may develop psychosocial disorders. Other conditions in patients with psoriasis include diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, Crohn disease, and the metabolic syndrome.

Results from surveys conducted by the National Psoriasis Foundation from 2003 to 2011 found that the diagnosis of psoriasis preceded PsA in the majority of patients by a mean period of 14.6 years. Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were more likely to develop PsA than patients with mild psoriasis. Furthermore, patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to develop diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

In a Cutis editorial, Dr. Jeffrey Weinberg emphasizes that the role of the dermatologist “is to identify and educate patients with psoriasis who are at risk of systemic complications and ensure appropriate follow-up for their treatment and overall health.” An infographic created by the American Academy of Dermatology illustrates areas of the body that may be impacted by psoriasis beyond the skin; for example, patients may develop eye problems, weight gain, or mood changes. Consider distributing this infographic to patients to show how psoriasis can affect more than their skin.

More Cutis content is available on psoriasis comorbidities:

- Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Bebo B. Psoriasis comorbidities: results from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys 2003 to 2011. Dermatology. 2012;225:121-126.

- Can psoriasis affect more than my skin? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/psoriasis-signs-and-symptoms/can-psoriasis-affect-more-than-my-skin. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Psoriasis: more than skin deep. Harv Mens Health Watch. 2010;14:4-5. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/psoriasis-more-than-skin-deep. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Weinberg JM. More than skin deep. Cutis. 2008;82:175.

Myth: Psoriasis Is Only a Skin Problem

Psoriasis is predominantly regarded as a skin disease because of the outward clinical presentation of the condition. However, psoriasis is a disorder of the immune system and its damage may be more than skin deep.

Psoriasis commonly presents on the skin and nails, but a growing body of evidence has suggested that psoriasis is associated with systemic comorbidities. Up to 25% of psoriasis patients develop joint inflammation, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) may precede skin involvement. There also is a risk for cardiovascular complications. Because of the emotional distress caused by psoriasis, patients may develop psychosocial disorders. Other conditions in patients with psoriasis include diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, Crohn disease, and the metabolic syndrome.

Results from surveys conducted by the National Psoriasis Foundation from 2003 to 2011 found that the diagnosis of psoriasis preceded PsA in the majority of patients by a mean period of 14.6 years. Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were more likely to develop PsA than patients with mild psoriasis. Furthermore, patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to develop diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

In a Cutis editorial, Dr. Jeffrey Weinberg emphasizes that the role of the dermatologist “is to identify and educate patients with psoriasis who are at risk of systemic complications and ensure appropriate follow-up for their treatment and overall health.” An infographic created by the American Academy of Dermatology illustrates areas of the body that may be impacted by psoriasis beyond the skin; for example, patients may develop eye problems, weight gain, or mood changes. Consider distributing this infographic to patients to show how psoriasis can affect more than their skin.

More Cutis content is available on psoriasis comorbidities:

Myth: Psoriasis Is Only a Skin Problem

Psoriasis is predominantly regarded as a skin disease because of the outward clinical presentation of the condition. However, psoriasis is a disorder of the immune system and its damage may be more than skin deep.

Psoriasis commonly presents on the skin and nails, but a growing body of evidence has suggested that psoriasis is associated with systemic comorbidities. Up to 25% of psoriasis patients develop joint inflammation, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) may precede skin involvement. There also is a risk for cardiovascular complications. Because of the emotional distress caused by psoriasis, patients may develop psychosocial disorders. Other conditions in patients with psoriasis include diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, Crohn disease, and the metabolic syndrome.

Results from surveys conducted by the National Psoriasis Foundation from 2003 to 2011 found that the diagnosis of psoriasis preceded PsA in the majority of patients by a mean period of 14.6 years. Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis were more likely to develop PsA than patients with mild psoriasis. Furthermore, patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to develop diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

In a Cutis editorial, Dr. Jeffrey Weinberg emphasizes that the role of the dermatologist “is to identify and educate patients with psoriasis who are at risk of systemic complications and ensure appropriate follow-up for their treatment and overall health.” An infographic created by the American Academy of Dermatology illustrates areas of the body that may be impacted by psoriasis beyond the skin; for example, patients may develop eye problems, weight gain, or mood changes. Consider distributing this infographic to patients to show how psoriasis can affect more than their skin.

More Cutis content is available on psoriasis comorbidities:

- Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Bebo B. Psoriasis comorbidities: results from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys 2003 to 2011. Dermatology. 2012;225:121-126.

- Can psoriasis affect more than my skin? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/psoriasis-signs-and-symptoms/can-psoriasis-affect-more-than-my-skin. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Psoriasis: more than skin deep. Harv Mens Health Watch. 2010;14:4-5. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/psoriasis-more-than-skin-deep. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Weinberg JM. More than skin deep. Cutis. 2008;82:175.

- Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Bebo B. Psoriasis comorbidities: results from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys 2003 to 2011. Dermatology. 2012;225:121-126.

- Can psoriasis affect more than my skin? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/psoriasis-signs-and-symptoms/can-psoriasis-affect-more-than-my-skin. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Psoriasis: more than skin deep. Harv Mens Health Watch. 2010;14:4-5. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/psoriasis-more-than-skin-deep. Accessed December 10, 2018.

- Weinberg JM. More than skin deep. Cutis. 2008;82:175.

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Remove Psoriasis Scales Gently

Myth: Pick Psoriasis Scales to Remove Them

Patients may be inclined to pick psoriasis scales that appear in noticeable areas or on the scalp. However, they should be counseled to avoid this practice, which could cause an infection. Instead, Dr. Steven Feldman (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) suggests putting on an ointment or oil-like medication to soften the scale. “Almost any kind of moisturizer will change the reflective properties of the scale so that you don’t see the scale,” he advised. He also suggested descaling agents such as topical salicylic acid or lactic acid. His patient education video is available on the American Academy of Dermatology website should you wish to direct your patients to it.

Because salicylic acid is a keratolytic (or peeling agent), it works by causing the outer layer of skin to shed. When applied topically, it helps to soften and lift psoriasis scales. Coal tar over-the-counter products also can be used for the same purpose. The over-the-counter product guide from the National Psoriasis Foundation is a valuable resource to share with patients.

Expert Commentary

I agree that it is very important to treat scale very gently. In addition to risk for infection, picking and traumatizing scale can lead to worsening of the psoriasis. This is known as the Koebner phenomenon. The phenomenon was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1876 as the formation of psoriatic lesions in uninvolved skin of patients with psoriasis after cutaneous trauma. This isomorphic phenomenon is now known to involve numerous diseases, among them vitiligo, lichen planus, and Darier disease.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg, MD (New York, New York)

Feldman S. How should I remove psoriasis scale? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Accessed October 31, 2018.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Over-the-counter products. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Published June 2017. Accessed October 31, 2018.

Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

Myth: Pick Psoriasis Scales to Remove Them

Patients may be inclined to pick psoriasis scales that appear in noticeable areas or on the scalp. However, they should be counseled to avoid this practice, which could cause an infection. Instead, Dr. Steven Feldman (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) suggests putting on an ointment or oil-like medication to soften the scale. “Almost any kind of moisturizer will change the reflective properties of the scale so that you don’t see the scale,” he advised. He also suggested descaling agents such as topical salicylic acid or lactic acid. His patient education video is available on the American Academy of Dermatology website should you wish to direct your patients to it.

Because salicylic acid is a keratolytic (or peeling agent), it works by causing the outer layer of skin to shed. When applied topically, it helps to soften and lift psoriasis scales. Coal tar over-the-counter products also can be used for the same purpose. The over-the-counter product guide from the National Psoriasis Foundation is a valuable resource to share with patients.

Expert Commentary

I agree that it is very important to treat scale very gently. In addition to risk for infection, picking and traumatizing scale can lead to worsening of the psoriasis. This is known as the Koebner phenomenon. The phenomenon was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1876 as the formation of psoriatic lesions in uninvolved skin of patients with psoriasis after cutaneous trauma. This isomorphic phenomenon is now known to involve numerous diseases, among them vitiligo, lichen planus, and Darier disease.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg, MD (New York, New York)

Myth: Pick Psoriasis Scales to Remove Them

Patients may be inclined to pick psoriasis scales that appear in noticeable areas or on the scalp. However, they should be counseled to avoid this practice, which could cause an infection. Instead, Dr. Steven Feldman (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) suggests putting on an ointment or oil-like medication to soften the scale. “Almost any kind of moisturizer will change the reflective properties of the scale so that you don’t see the scale,” he advised. He also suggested descaling agents such as topical salicylic acid or lactic acid. His patient education video is available on the American Academy of Dermatology website should you wish to direct your patients to it.

Because salicylic acid is a keratolytic (or peeling agent), it works by causing the outer layer of skin to shed. When applied topically, it helps to soften and lift psoriasis scales. Coal tar over-the-counter products also can be used for the same purpose. The over-the-counter product guide from the National Psoriasis Foundation is a valuable resource to share with patients.

Expert Commentary

I agree that it is very important to treat scale very gently. In addition to risk for infection, picking and traumatizing scale can lead to worsening of the psoriasis. This is known as the Koebner phenomenon. The phenomenon was first described by Heinrich Koebner in 1876 as the formation of psoriatic lesions in uninvolved skin of patients with psoriasis after cutaneous trauma. This isomorphic phenomenon is now known to involve numerous diseases, among them vitiligo, lichen planus, and Darier disease.

—Jeffrey M. Weinberg, MD (New York, New York)

Feldman S. How should I remove psoriasis scale? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Accessed October 31, 2018.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Over-the-counter products. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Published June 2017. Accessed October 31, 2018.

Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

Feldman S. How should I remove psoriasis scale? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Accessed October 31, 2018.

National Psoriasis Foundation. Over-the-counter products. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/scaly-skin/psoriasis/tips-for-managing-psoriasis/how-should-i-remove-psoriasis-scale. Published June 2017. Accessed October 31, 2018.

Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

Composite Fixation of Proximal Tibial Nonunions: A Technical Trick

ABSTRACT

Nonunion after a proximal tibia fracture is often associated with poor bone stock, (previous) infection, and compromised soft tissues. These conditions make revision internal fixation with double plating difficult. Combining a plate and contralateral 2-pin external fixator, coined composite fixation, can provide an alternative means of obtaining stability without further compromising soft tissues.

Three patients with a proximal tibia nonunion precluding standard internal fixation with double plating were treated with composite fixation. All 3 patients achieved union with deformity correction at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months). The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°) and postoperative ROM returned to pre-injury levels.

Composite fixation can be a helpful adjunct in the treatment of this challenging problem.

Continue to: Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion...

Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion is challenging, compromised by limited bone stock, pre-existing hardware, stiffness, poor soft tissue conditions, and infection. The goals of treatment include bone union, re-establishment of both joint stability and lower extremity alignment, restoration of an anatomic articular surface, and recovery of function.1 Currently, various treatment options such as plate fixation, bone grafting, intramedullary nailing, external fixation, functional bracing, or a combination of these are available.1-8 Rigid internal fixation is the gold standard for most nonunions. However, sometimes local soft tissues or bone quality preclude standard internal fixation. Bolhofner9 described the combination of a single plate and an external fixator on the contralateral side for the management of extra-articular proximal tibial fractures with compromised soft tissues, and the technique known as composite fixation was coined. The external fixator on 1 side and the plate on the other, generate a balanced, stable environment while limiting the use of foreign hardware, thereby avoiding both additional soft-tissue damage and periosteal stripping.9-11 In this technical article, we describe the indication, technique, and outcomes of 3 patients with proximal tibial nonunions, who were successfully treated with composite fixation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATIENTS

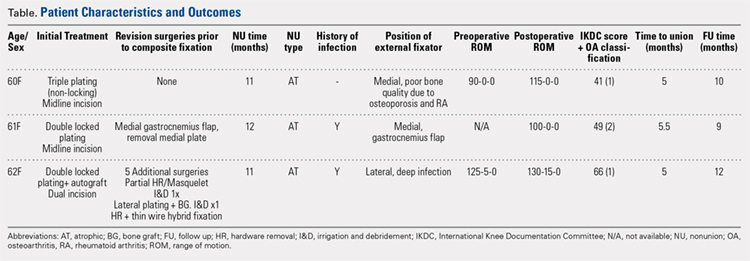

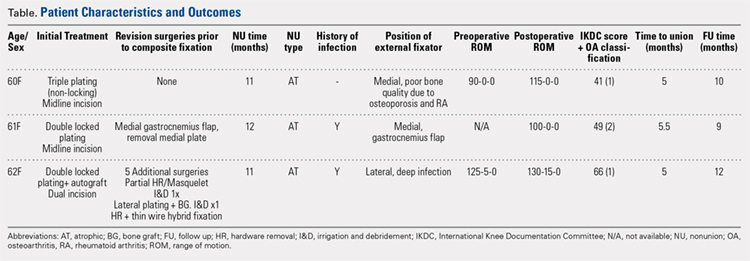

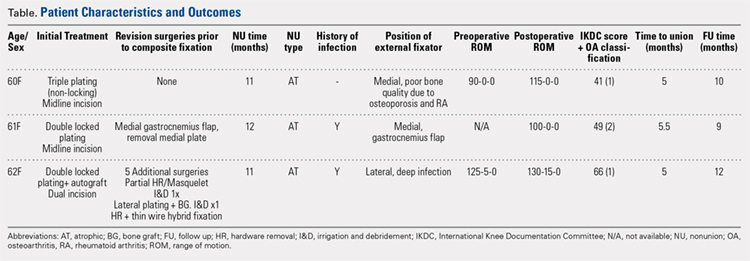

Between January 2014 and July 2016, 3 patients each with a proximal tibial nonunion that developed after a bicondylar tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker type VI) were treated with composite fixation (Table). The 3 patients were female with an average age of 61 years (range, 60-62 years), and a body mass index of 23.7 kg/m2 (range, 19.0-31.9 kg/m2). All 3 patients had sustained a tibial plateau fracture that was primarily treated with open reduction and internal fixation. Two of them had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and were being treated with methotrexate and Humira (adalimumab) (case 1), and with methotrexate, prednisolone, and etanercept (case 3). The etanercept was discontinued after discussion with the treating rheumatologist when a deep infection developed. Two patients (cases 1 and 2) were referred to us because of their nonunions. All 3 patients developed extra-articular nonunions with compromised bone stock. Two patients had developed deep infections during treatment of their plateau fractures; 1 of these patients underwent a medial gastrocnemius flap for wound coverage (case 1). The second patient (case 3) with a deep infection underwent partial hardware removal, a Masquelet salvage procedure, and revision plate fixation. However, the infection recurred. The hardware was removed, and 2 débridements with conversion to a hybrid external fixator with thin wire fixation were done. Due to her longstanding rheumatoid arthritis, the patient had bilateral valgus knee malalignment causing the ring fixator to strike her contralateral knee when she walked. The period from the initial tibial plateau fracture to our composite fixation averaged 11.3 months (range, 11-12 months). Indications for the use of the composite fixation comprised previously infected soft tissue on the lateral side and inability to walk with a hybrid thin wire fixator because of valgus knees (case 3), a medial gastrocnemius flap (case 2), and poor bone quality (case 1). Follow-up consisted of clinical examination, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test that is a standardized test for mobility, and radiographic evaluation at routine appointments up to 1 year or until healed.12 At the last follow-up visit, patients filled out the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee form.13

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

A fellowship-trained orthopedic trauma surgeon treated all patients. Patients were placed on a radiolucent operating table after general or regional anesthesia. Previous incisions were used. Two patients had a midline incision; the third had both a posteromedial and an anterolateral incision. Five deep tissue cultures were taken after which antibiotics were given intravenously. All unstable or failed hardware was removed. Aggressive débridement of the nonunion was performed. After débridement, multiple holes were drilled with a 2.0 mm drill bit until blood was seen to egress from both sides of the medullary canal. Malalignment of the proximal tibia was corrected and checked fluoroscopically. Fixation was done with an anatomic locking plate (LCP Proximal Tibia Plate 3.5; DePuy Synthes) with a mixture of locking and non-locking screws. In 2 patients, a tricortical graft from the posterior iliac crest was positioned in the defect. Additional autologous bone graft and demineralized bone matrix was added around the nonunion. Although locking screws were used, the fixation did not appear to be strong enough to resist the varus (cases 1 and 2), or the valgus (case 3) deforming forces. Additional fixation was thus needed. However, the contralateral soft tissues were compromised in case 2 (medial gastrocnemius flap), and case 3 (a previously infected area with very tenuous skin laterally), whereas the bone was considered to be of insufficient quality in case 1. The opposite side of the nonunion was stabilized using composite fixation with a 2-pin external fixator to circumvent the need for additional plate fixation. In 2 patients, the plate was placed laterally, and the external fixator medially. In the third patient, the plate was positioned medially, and the external fixator laterally. The plate was always placed first. The external fixator was placed last. Using fluoroscopy, we ensured that the fixator pins would not interfere with the screws. The pins were predrilled and positioned perpendicular to the tibia through small stab incisions. We prefer hydroxyapatite-coated pins (6-mm diameter, XCaliber Bone Screws; Pro-Motion Medical) to increase their holding power in the often osteopenic bone. Postoperative management consisted of toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks and progressed to full weight-bearing at 3 months. Radiographs were taken on postoperative day 1, at 6 weeks, and at 12 weeks until healed. No continuous passive motion was used postoperatively. Antibiotics were continued until cultures were negative. No specific pin care was used. We advised patients to shower daily with the external fixator in place, once the wounds have healed.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

On average, patients were hospitalized for 5 days (range, 3-7 days). There were no postoperative complications. None of the patients developed a clinically significant pin site infection. There were no re-operations during follow-up. All patients achieved union at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months) (Figure 1).

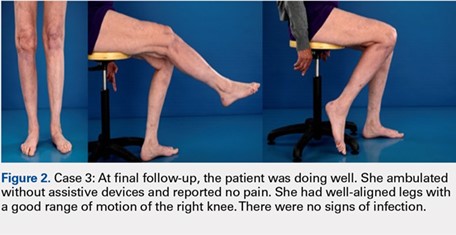

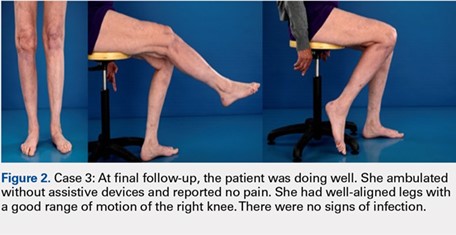

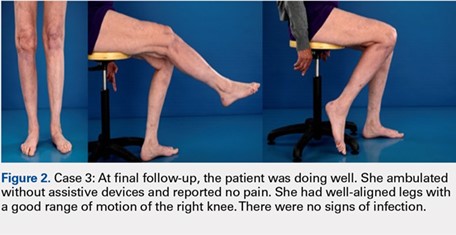

Deformity correction was achieved in all 3 patients. The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°). None of the patients had an extension deficit. TUG test was <8 seconds in all patients. The IKDC knee score averaged 52 (range, 41-66). Of note is that 2 patients already had compromised knee function before the fracture because of rheumatoid arthritis. The Ahlbäck classification of osteoarthritis showed grade 1 in cases 1 and 3, and grade 2 in case 2.14 Postoperative ROM of the knee returned to pre-injury levels in all patients (Figure 2). The 2-pin external fixator was removed at 9 weeks on average (range, 6-12 weeks) postoperatively in the outpatient clinic. At the last follow-up appointment at an average of 10.3 months (range, 9-12 months), all wounds had healed without infection. All patients had a normal neurovascular examination.

DISCUSSION

Nonunion after a proximal tibial fracture is rare.4 In cases when nonunions do develop, they most often pertain to the extra-articular component with the plateau component healed. Surgical exposure for débridements, hardware removal, bone grafting, and revision of fixation carries the risk of wound breakdown, necrosis, and infection. The alternative strategy of composite fixation (a plate combined with a contralateral 2-pin external fixator) to limit additional soft tissue compromise was already described in proximal tibial fractures by Bolhofner.9 He treated 41 extra-articular proximal tibial fractures using this composite fixation technique and attained successful results with an average time to union of 12.1 weeks. There was only 1 malunion, 2 wound infections, and 3 delayed unions.

In our practice, we have extrapolated this idea to an extra-articular nonunion that developed after a tibial plateau fracture. With the use of an external fixator, we provided sufficient mechanical stability of the nonunion without unnecessarily compromising previously infected or tenuous soft tissues, a muscle flap, or further devascularizing poor bone. Limitations of this study include the retrospective data and small sample size prone to bias. However, all patients received the same treatment protocol from 1 orthopedic trauma surgeon, follow-up intervals were similar, and data were acquired consistently.

Meanwhile, we have used this technique in a fourth patient with a septic nonunion of a tibial plateau fracture. All 4 patients in whom we have used this method so far have healed successfully.

CONCLUSION

This technique respects both the demand for minimal soft tissue damage and a maximal stable environment without notable perioperative and postoperative complications. It also offers an alternative option for the treatment of a proximal tibial nonunion that is not amenable to invasive revision dual plate fixation. As such, it can be a useful addition to the existing armamentarium of the treating surgeon.

1. Wu CC. Salvage of proximal tibial malunion or nonunion with the use of angled blade plate. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126(2):82-87. doi:10.1007/s00402-006-0106-9.

2. Carpenter CA, Jupiter JB. Blade plate reconstruction of metaphyseal nonunion of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;332:23-28.

3. Gardner MJ, Toro-Arbelaez JB, Hansen M, Boraiah S, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Surgical treatment and outcomes of extraarticular proximal tibial nonunions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(8):833-839. doi:10.1007/s00402-007-0383-y.

4. Toro-Arbelaez JB, Gardner MJ, Shindle MK, Cabas JM, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Open reduction and internal fixation of intraarticular tibial plateau nonunions. Injury. 2007;38(3):378-383. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2006.11.003.

5. Mechrefe AP, Koh EY, Trafton PG, DiGiovanni CW. Tibial nonunion. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(1):1-18, vii. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2005.12.003.

6. Chin KR, Nagarkatti DG, Miranda MA, Santoro VM, Baumgaertner MR, Jupiter JB. Salvage of distal tibia metaphyseal nonunions with the 90 degrees cannulated blade plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(409):241-249.

7. Devgan A, Kamboj P, Gupta V, Magu NK, Rohilla R. Pseudoarthrosis of medial tibial plateau fracture-role of alignment procedure. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(2):118-121. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1275.2013.02.011.

8. Helfet DL, Jupiter JB, Gasser S. Indirect reduction and tension-band plating of tibial non-union with deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(9):1286-1297.

9. Bolhofner BR. Indirect reduction and composite fixation of extraarticular proximal tibial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(315):75-83. doi:10.1097/00003086-199506000-00009.

10. Ries MD, Meinhard BP. Medial external fixation with lateral plate internal fixation in metaphyseal tibia fractures. A report of eight cases associated with severe soft-tissue injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(256):215-223.

11. Weiner LS, Kelley M, Yang E, et al. The use of combination internal fixation and hybrid external fixation in severe proximal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):244-250.

12. Alghadir A, Anwer S, Brismee JM. The reliability and minimal detectable change of Timed Up and Go test in individuals with grade 1-3 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:174. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0637-8.

13. Haverkamp D, Sierevelt IN, Breugem SJ, Lohuis K, Blankevoort L, van Dijk CN. Translation and validation of the Dutch version of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1680-1684. doi:10.1177/0363546506288854.

14. Ahlbäck S. Osteoartrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1968;Suppl 277:7-72.

ABSTRACT

Nonunion after a proximal tibia fracture is often associated with poor bone stock, (previous) infection, and compromised soft tissues. These conditions make revision internal fixation with double plating difficult. Combining a plate and contralateral 2-pin external fixator, coined composite fixation, can provide an alternative means of obtaining stability without further compromising soft tissues.

Three patients with a proximal tibia nonunion precluding standard internal fixation with double plating were treated with composite fixation. All 3 patients achieved union with deformity correction at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months). The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°) and postoperative ROM returned to pre-injury levels.

Composite fixation can be a helpful adjunct in the treatment of this challenging problem.

Continue to: Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion...

Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion is challenging, compromised by limited bone stock, pre-existing hardware, stiffness, poor soft tissue conditions, and infection. The goals of treatment include bone union, re-establishment of both joint stability and lower extremity alignment, restoration of an anatomic articular surface, and recovery of function.1 Currently, various treatment options such as plate fixation, bone grafting, intramedullary nailing, external fixation, functional bracing, or a combination of these are available.1-8 Rigid internal fixation is the gold standard for most nonunions. However, sometimes local soft tissues or bone quality preclude standard internal fixation. Bolhofner9 described the combination of a single plate and an external fixator on the contralateral side for the management of extra-articular proximal tibial fractures with compromised soft tissues, and the technique known as composite fixation was coined. The external fixator on 1 side and the plate on the other, generate a balanced, stable environment while limiting the use of foreign hardware, thereby avoiding both additional soft-tissue damage and periosteal stripping.9-11 In this technical article, we describe the indication, technique, and outcomes of 3 patients with proximal tibial nonunions, who were successfully treated with composite fixation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATIENTS

Between January 2014 and July 2016, 3 patients each with a proximal tibial nonunion that developed after a bicondylar tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker type VI) were treated with composite fixation (Table). The 3 patients were female with an average age of 61 years (range, 60-62 years), and a body mass index of 23.7 kg/m2 (range, 19.0-31.9 kg/m2). All 3 patients had sustained a tibial plateau fracture that was primarily treated with open reduction and internal fixation. Two of them had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and were being treated with methotrexate and Humira (adalimumab) (case 1), and with methotrexate, prednisolone, and etanercept (case 3). The etanercept was discontinued after discussion with the treating rheumatologist when a deep infection developed. Two patients (cases 1 and 2) were referred to us because of their nonunions. All 3 patients developed extra-articular nonunions with compromised bone stock. Two patients had developed deep infections during treatment of their plateau fractures; 1 of these patients underwent a medial gastrocnemius flap for wound coverage (case 1). The second patient (case 3) with a deep infection underwent partial hardware removal, a Masquelet salvage procedure, and revision plate fixation. However, the infection recurred. The hardware was removed, and 2 débridements with conversion to a hybrid external fixator with thin wire fixation were done. Due to her longstanding rheumatoid arthritis, the patient had bilateral valgus knee malalignment causing the ring fixator to strike her contralateral knee when she walked. The period from the initial tibial plateau fracture to our composite fixation averaged 11.3 months (range, 11-12 months). Indications for the use of the composite fixation comprised previously infected soft tissue on the lateral side and inability to walk with a hybrid thin wire fixator because of valgus knees (case 3), a medial gastrocnemius flap (case 2), and poor bone quality (case 1). Follow-up consisted of clinical examination, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test that is a standardized test for mobility, and radiographic evaluation at routine appointments up to 1 year or until healed.12 At the last follow-up visit, patients filled out the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee form.13

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

A fellowship-trained orthopedic trauma surgeon treated all patients. Patients were placed on a radiolucent operating table after general or regional anesthesia. Previous incisions were used. Two patients had a midline incision; the third had both a posteromedial and an anterolateral incision. Five deep tissue cultures were taken after which antibiotics were given intravenously. All unstable or failed hardware was removed. Aggressive débridement of the nonunion was performed. After débridement, multiple holes were drilled with a 2.0 mm drill bit until blood was seen to egress from both sides of the medullary canal. Malalignment of the proximal tibia was corrected and checked fluoroscopically. Fixation was done with an anatomic locking plate (LCP Proximal Tibia Plate 3.5; DePuy Synthes) with a mixture of locking and non-locking screws. In 2 patients, a tricortical graft from the posterior iliac crest was positioned in the defect. Additional autologous bone graft and demineralized bone matrix was added around the nonunion. Although locking screws were used, the fixation did not appear to be strong enough to resist the varus (cases 1 and 2), or the valgus (case 3) deforming forces. Additional fixation was thus needed. However, the contralateral soft tissues were compromised in case 2 (medial gastrocnemius flap), and case 3 (a previously infected area with very tenuous skin laterally), whereas the bone was considered to be of insufficient quality in case 1. The opposite side of the nonunion was stabilized using composite fixation with a 2-pin external fixator to circumvent the need for additional plate fixation. In 2 patients, the plate was placed laterally, and the external fixator medially. In the third patient, the plate was positioned medially, and the external fixator laterally. The plate was always placed first. The external fixator was placed last. Using fluoroscopy, we ensured that the fixator pins would not interfere with the screws. The pins were predrilled and positioned perpendicular to the tibia through small stab incisions. We prefer hydroxyapatite-coated pins (6-mm diameter, XCaliber Bone Screws; Pro-Motion Medical) to increase their holding power in the often osteopenic bone. Postoperative management consisted of toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks and progressed to full weight-bearing at 3 months. Radiographs were taken on postoperative day 1, at 6 weeks, and at 12 weeks until healed. No continuous passive motion was used postoperatively. Antibiotics were continued until cultures were negative. No specific pin care was used. We advised patients to shower daily with the external fixator in place, once the wounds have healed.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

On average, patients were hospitalized for 5 days (range, 3-7 days). There were no postoperative complications. None of the patients developed a clinically significant pin site infection. There were no re-operations during follow-up. All patients achieved union at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months) (Figure 1).

Deformity correction was achieved in all 3 patients. The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°). None of the patients had an extension deficit. TUG test was <8 seconds in all patients. The IKDC knee score averaged 52 (range, 41-66). Of note is that 2 patients already had compromised knee function before the fracture because of rheumatoid arthritis. The Ahlbäck classification of osteoarthritis showed grade 1 in cases 1 and 3, and grade 2 in case 2.14 Postoperative ROM of the knee returned to pre-injury levels in all patients (Figure 2). The 2-pin external fixator was removed at 9 weeks on average (range, 6-12 weeks) postoperatively in the outpatient clinic. At the last follow-up appointment at an average of 10.3 months (range, 9-12 months), all wounds had healed without infection. All patients had a normal neurovascular examination.

DISCUSSION

Nonunion after a proximal tibial fracture is rare.4 In cases when nonunions do develop, they most often pertain to the extra-articular component with the plateau component healed. Surgical exposure for débridements, hardware removal, bone grafting, and revision of fixation carries the risk of wound breakdown, necrosis, and infection. The alternative strategy of composite fixation (a plate combined with a contralateral 2-pin external fixator) to limit additional soft tissue compromise was already described in proximal tibial fractures by Bolhofner.9 He treated 41 extra-articular proximal tibial fractures using this composite fixation technique and attained successful results with an average time to union of 12.1 weeks. There was only 1 malunion, 2 wound infections, and 3 delayed unions.

In our practice, we have extrapolated this idea to an extra-articular nonunion that developed after a tibial plateau fracture. With the use of an external fixator, we provided sufficient mechanical stability of the nonunion without unnecessarily compromising previously infected or tenuous soft tissues, a muscle flap, or further devascularizing poor bone. Limitations of this study include the retrospective data and small sample size prone to bias. However, all patients received the same treatment protocol from 1 orthopedic trauma surgeon, follow-up intervals were similar, and data were acquired consistently.

Meanwhile, we have used this technique in a fourth patient with a septic nonunion of a tibial plateau fracture. All 4 patients in whom we have used this method so far have healed successfully.

CONCLUSION

This technique respects both the demand for minimal soft tissue damage and a maximal stable environment without notable perioperative and postoperative complications. It also offers an alternative option for the treatment of a proximal tibial nonunion that is not amenable to invasive revision dual plate fixation. As such, it can be a useful addition to the existing armamentarium of the treating surgeon.

ABSTRACT

Nonunion after a proximal tibia fracture is often associated with poor bone stock, (previous) infection, and compromised soft tissues. These conditions make revision internal fixation with double plating difficult. Combining a plate and contralateral 2-pin external fixator, coined composite fixation, can provide an alternative means of obtaining stability without further compromising soft tissues.

Three patients with a proximal tibia nonunion precluding standard internal fixation with double plating were treated with composite fixation. All 3 patients achieved union with deformity correction at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months). The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°) and postoperative ROM returned to pre-injury levels.

Composite fixation can be a helpful adjunct in the treatment of this challenging problem.

Continue to: Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion...

Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion is challenging, compromised by limited bone stock, pre-existing hardware, stiffness, poor soft tissue conditions, and infection. The goals of treatment include bone union, re-establishment of both joint stability and lower extremity alignment, restoration of an anatomic articular surface, and recovery of function.1 Currently, various treatment options such as plate fixation, bone grafting, intramedullary nailing, external fixation, functional bracing, or a combination of these are available.1-8 Rigid internal fixation is the gold standard for most nonunions. However, sometimes local soft tissues or bone quality preclude standard internal fixation. Bolhofner9 described the combination of a single plate and an external fixator on the contralateral side for the management of extra-articular proximal tibial fractures with compromised soft tissues, and the technique known as composite fixation was coined. The external fixator on 1 side and the plate on the other, generate a balanced, stable environment while limiting the use of foreign hardware, thereby avoiding both additional soft-tissue damage and periosteal stripping.9-11 In this technical article, we describe the indication, technique, and outcomes of 3 patients with proximal tibial nonunions, who were successfully treated with composite fixation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATIENTS

Between January 2014 and July 2016, 3 patients each with a proximal tibial nonunion that developed after a bicondylar tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker type VI) were treated with composite fixation (Table). The 3 patients were female with an average age of 61 years (range, 60-62 years), and a body mass index of 23.7 kg/m2 (range, 19.0-31.9 kg/m2). All 3 patients had sustained a tibial plateau fracture that was primarily treated with open reduction and internal fixation. Two of them had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and were being treated with methotrexate and Humira (adalimumab) (case 1), and with methotrexate, prednisolone, and etanercept (case 3). The etanercept was discontinued after discussion with the treating rheumatologist when a deep infection developed. Two patients (cases 1 and 2) were referred to us because of their nonunions. All 3 patients developed extra-articular nonunions with compromised bone stock. Two patients had developed deep infections during treatment of their plateau fractures; 1 of these patients underwent a medial gastrocnemius flap for wound coverage (case 1). The second patient (case 3) with a deep infection underwent partial hardware removal, a Masquelet salvage procedure, and revision plate fixation. However, the infection recurred. The hardware was removed, and 2 débridements with conversion to a hybrid external fixator with thin wire fixation were done. Due to her longstanding rheumatoid arthritis, the patient had bilateral valgus knee malalignment causing the ring fixator to strike her contralateral knee when she walked. The period from the initial tibial plateau fracture to our composite fixation averaged 11.3 months (range, 11-12 months). Indications for the use of the composite fixation comprised previously infected soft tissue on the lateral side and inability to walk with a hybrid thin wire fixator because of valgus knees (case 3), a medial gastrocnemius flap (case 2), and poor bone quality (case 1). Follow-up consisted of clinical examination, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test that is a standardized test for mobility, and radiographic evaluation at routine appointments up to 1 year or until healed.12 At the last follow-up visit, patients filled out the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee form.13

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

A fellowship-trained orthopedic trauma surgeon treated all patients. Patients were placed on a radiolucent operating table after general or regional anesthesia. Previous incisions were used. Two patients had a midline incision; the third had both a posteromedial and an anterolateral incision. Five deep tissue cultures were taken after which antibiotics were given intravenously. All unstable or failed hardware was removed. Aggressive débridement of the nonunion was performed. After débridement, multiple holes were drilled with a 2.0 mm drill bit until blood was seen to egress from both sides of the medullary canal. Malalignment of the proximal tibia was corrected and checked fluoroscopically. Fixation was done with an anatomic locking plate (LCP Proximal Tibia Plate 3.5; DePuy Synthes) with a mixture of locking and non-locking screws. In 2 patients, a tricortical graft from the posterior iliac crest was positioned in the defect. Additional autologous bone graft and demineralized bone matrix was added around the nonunion. Although locking screws were used, the fixation did not appear to be strong enough to resist the varus (cases 1 and 2), or the valgus (case 3) deforming forces. Additional fixation was thus needed. However, the contralateral soft tissues were compromised in case 2 (medial gastrocnemius flap), and case 3 (a previously infected area with very tenuous skin laterally), whereas the bone was considered to be of insufficient quality in case 1. The opposite side of the nonunion was stabilized using composite fixation with a 2-pin external fixator to circumvent the need for additional plate fixation. In 2 patients, the plate was placed laterally, and the external fixator medially. In the third patient, the plate was positioned medially, and the external fixator laterally. The plate was always placed first. The external fixator was placed last. Using fluoroscopy, we ensured that the fixator pins would not interfere with the screws. The pins were predrilled and positioned perpendicular to the tibia through small stab incisions. We prefer hydroxyapatite-coated pins (6-mm diameter, XCaliber Bone Screws; Pro-Motion Medical) to increase their holding power in the often osteopenic bone. Postoperative management consisted of toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks and progressed to full weight-bearing at 3 months. Radiographs were taken on postoperative day 1, at 6 weeks, and at 12 weeks until healed. No continuous passive motion was used postoperatively. Antibiotics were continued until cultures were negative. No specific pin care was used. We advised patients to shower daily with the external fixator in place, once the wounds have healed.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

On average, patients were hospitalized for 5 days (range, 3-7 days). There were no postoperative complications. None of the patients developed a clinically significant pin site infection. There were no re-operations during follow-up. All patients achieved union at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months) (Figure 1).

Deformity correction was achieved in all 3 patients. The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°). None of the patients had an extension deficit. TUG test was <8 seconds in all patients. The IKDC knee score averaged 52 (range, 41-66). Of note is that 2 patients already had compromised knee function before the fracture because of rheumatoid arthritis. The Ahlbäck classification of osteoarthritis showed grade 1 in cases 1 and 3, and grade 2 in case 2.14 Postoperative ROM of the knee returned to pre-injury levels in all patients (Figure 2). The 2-pin external fixator was removed at 9 weeks on average (range, 6-12 weeks) postoperatively in the outpatient clinic. At the last follow-up appointment at an average of 10.3 months (range, 9-12 months), all wounds had healed without infection. All patients had a normal neurovascular examination.

DISCUSSION

Nonunion after a proximal tibial fracture is rare.4 In cases when nonunions do develop, they most often pertain to the extra-articular component with the plateau component healed. Surgical exposure for débridements, hardware removal, bone grafting, and revision of fixation carries the risk of wound breakdown, necrosis, and infection. The alternative strategy of composite fixation (a plate combined with a contralateral 2-pin external fixator) to limit additional soft tissue compromise was already described in proximal tibial fractures by Bolhofner.9 He treated 41 extra-articular proximal tibial fractures using this composite fixation technique and attained successful results with an average time to union of 12.1 weeks. There was only 1 malunion, 2 wound infections, and 3 delayed unions.

In our practice, we have extrapolated this idea to an extra-articular nonunion that developed after a tibial plateau fracture. With the use of an external fixator, we provided sufficient mechanical stability of the nonunion without unnecessarily compromising previously infected or tenuous soft tissues, a muscle flap, or further devascularizing poor bone. Limitations of this study include the retrospective data and small sample size prone to bias. However, all patients received the same treatment protocol from 1 orthopedic trauma surgeon, follow-up intervals were similar, and data were acquired consistently.

Meanwhile, we have used this technique in a fourth patient with a septic nonunion of a tibial plateau fracture. All 4 patients in whom we have used this method so far have healed successfully.

CONCLUSION

This technique respects both the demand for minimal soft tissue damage and a maximal stable environment without notable perioperative and postoperative complications. It also offers an alternative option for the treatment of a proximal tibial nonunion that is not amenable to invasive revision dual plate fixation. As such, it can be a useful addition to the existing armamentarium of the treating surgeon.

1. Wu CC. Salvage of proximal tibial malunion or nonunion with the use of angled blade plate. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126(2):82-87. doi:10.1007/s00402-006-0106-9.

2. Carpenter CA, Jupiter JB. Blade plate reconstruction of metaphyseal nonunion of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;332:23-28.

3. Gardner MJ, Toro-Arbelaez JB, Hansen M, Boraiah S, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Surgical treatment and outcomes of extraarticular proximal tibial nonunions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(8):833-839. doi:10.1007/s00402-007-0383-y.

4. Toro-Arbelaez JB, Gardner MJ, Shindle MK, Cabas JM, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Open reduction and internal fixation of intraarticular tibial plateau nonunions. Injury. 2007;38(3):378-383. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2006.11.003.

5. Mechrefe AP, Koh EY, Trafton PG, DiGiovanni CW. Tibial nonunion. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(1):1-18, vii. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2005.12.003.

6. Chin KR, Nagarkatti DG, Miranda MA, Santoro VM, Baumgaertner MR, Jupiter JB. Salvage of distal tibia metaphyseal nonunions with the 90 degrees cannulated blade plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(409):241-249.

7. Devgan A, Kamboj P, Gupta V, Magu NK, Rohilla R. Pseudoarthrosis of medial tibial plateau fracture-role of alignment procedure. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(2):118-121. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1275.2013.02.011.

8. Helfet DL, Jupiter JB, Gasser S. Indirect reduction and tension-band plating of tibial non-union with deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(9):1286-1297.

9. Bolhofner BR. Indirect reduction and composite fixation of extraarticular proximal tibial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(315):75-83. doi:10.1097/00003086-199506000-00009.

10. Ries MD, Meinhard BP. Medial external fixation with lateral plate internal fixation in metaphyseal tibia fractures. A report of eight cases associated with severe soft-tissue injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(256):215-223.

11. Weiner LS, Kelley M, Yang E, et al. The use of combination internal fixation and hybrid external fixation in severe proximal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):244-250.

12. Alghadir A, Anwer S, Brismee JM. The reliability and minimal detectable change of Timed Up and Go test in individuals with grade 1-3 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:174. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0637-8.

13. Haverkamp D, Sierevelt IN, Breugem SJ, Lohuis K, Blankevoort L, van Dijk CN. Translation and validation of the Dutch version of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1680-1684. doi:10.1177/0363546506288854.

14. Ahlbäck S. Osteoartrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1968;Suppl 277:7-72.

1. Wu CC. Salvage of proximal tibial malunion or nonunion with the use of angled blade plate. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126(2):82-87. doi:10.1007/s00402-006-0106-9.

2. Carpenter CA, Jupiter JB. Blade plate reconstruction of metaphyseal nonunion of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;332:23-28.

3. Gardner MJ, Toro-Arbelaez JB, Hansen M, Boraiah S, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Surgical treatment and outcomes of extraarticular proximal tibial nonunions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(8):833-839. doi:10.1007/s00402-007-0383-y.

4. Toro-Arbelaez JB, Gardner MJ, Shindle MK, Cabas JM, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Open reduction and internal fixation of intraarticular tibial plateau nonunions. Injury. 2007;38(3):378-383. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2006.11.003.

5. Mechrefe AP, Koh EY, Trafton PG, DiGiovanni CW. Tibial nonunion. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(1):1-18, vii. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2005.12.003.

6. Chin KR, Nagarkatti DG, Miranda MA, Santoro VM, Baumgaertner MR, Jupiter JB. Salvage of distal tibia metaphyseal nonunions with the 90 degrees cannulated blade plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(409):241-249.

7. Devgan A, Kamboj P, Gupta V, Magu NK, Rohilla R. Pseudoarthrosis of medial tibial plateau fracture-role of alignment procedure. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(2):118-121. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1275.2013.02.011.

8. Helfet DL, Jupiter JB, Gasser S. Indirect reduction and tension-band plating of tibial non-union with deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(9):1286-1297.

9. Bolhofner BR. Indirect reduction and composite fixation of extraarticular proximal tibial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(315):75-83. doi:10.1097/00003086-199506000-00009.

10. Ries MD, Meinhard BP. Medial external fixation with lateral plate internal fixation in metaphyseal tibia fractures. A report of eight cases associated with severe soft-tissue injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(256):215-223.

11. Weiner LS, Kelley M, Yang E, et al. The use of combination internal fixation and hybrid external fixation in severe proximal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):244-250.

12. Alghadir A, Anwer S, Brismee JM. The reliability and minimal detectable change of Timed Up and Go test in individuals with grade 1-3 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:174. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0637-8.

13. Haverkamp D, Sierevelt IN, Breugem SJ, Lohuis K, Blankevoort L, van Dijk CN. Translation and validation of the Dutch version of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1680-1684. doi:10.1177/0363546506288854.

14. Ahlbäck S. Osteoartrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1968;Suppl 277:7-72.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Treatment goals for a nonunion are bone union, re-establishment of (joint) stability, extremity alignment, and recovery of function.

- A nonunion of a tibia plateau fracture is often associated with poor soft tissues from previous surgeries and/or infections.

- Ideally a combination of minimal soft tissue damage and maximal stable fixation is used for salvage.

- There is a high risk of complications when using dual plating in these cases.

- A combination of an external fixator with limited internal fixation can be a good alternative.