User login

Disability in medicine: My experience

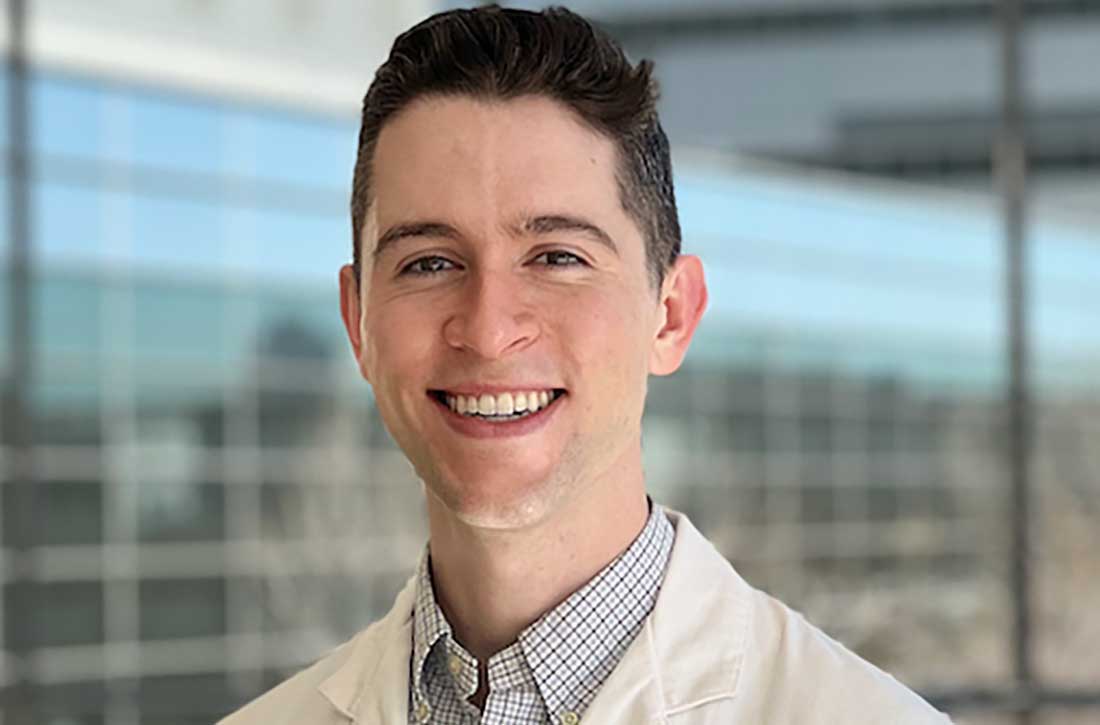

What does a doctor look like? Throughout history, this concept has shifted due to societal norms and increased access to medical education. Today, the idea of a physician has expanded to incorporate a myriad of people; however, stigma still exists in medicine regarding mental illness and disability. I would like to share my personal journey through high school, college, medical school, and now residency, and how my identity and struggles have shaped me into the physician I am today. There are few conversations around disability—especially disability and mental health—in medicine, and through my own advocacy, I have met many students with disability who feel that medical school is unattainable. Additionally, I have met many medical students, residents, and pre-health advisors who are happy for the experience to learn more about a marginalized group in medicine. My hope in sharing my story is to offer a space for conversation about intersectionality within medical communities and how physicians and physicians in training can facilitate that change, regardless of their position or specialty. Additionally, I hope to shed light on the unique mental health needs of patients with disabilities and how mental health clinicians can address those needs.

Perceived weaknesses turned into strengths

“Why do you walk like that?” “What is that brace on your leg?” The early years of my childhood were marked by these questions and others like them. I was the kid with the limp, the kid with a brace on his leg, and the kid who disappeared multiple times a week for doctor’s appointments or physical therapy. I learned to deflect these questions or give nebulous answers about an accident or injury. The reality is that I was born with cerebral palsy (CP). My CP manifested as hemiparesis on the left side of my body. I was in aggressive physical therapy throughout childhood, received Botox injections for muscle spasticity, and underwent corrective surgery on my left leg to straighten my foot. In childhood, the diagnosis meant nothing more than 2 words that sounded like they belonged to superheroes in comic books. Even with supportive parents and family, I kept my disability a secret, much like the powers and abilities of my favorite superheroes.

However, like all great origin stories, what I once thought were weaknesses turned out to be strengths that pushed me through college, medical school, and now psychiatry residency. Living with a disability has shaped how I see the world and relate to my patients. My experience has helped me connect to my patients in ways others might not. These properties are important in any physician but vital in psychiatry, where many patients feel neglected or stigmatized; this is another reason there should be more doctors with disabilities in medicine. Unfortunately, systemic barriers are still in place that disincentivize those with a disability from pursuing careers in medicine. Stories like mine are important to inspire a reexamination of what a physician should be and how medicine, patients, and communities benefit from this change.

My experience through medical school

My path to psychiatry and residency was shaped by my early experience with the medical field and treatment. From the early days of my diagnosis at age 4, I was told that my brain was “wired differently” and that, because of this disruption in circuitry, I would have difficulty with physical activity. I grew to appreciate the intricacies of the brain and pathology to understand my body. With greater understanding came the existential realization that I would live with a disability for the rest of my life. Rather than dream of a future where I would be “normal,” I focused on adapting my life to my normal. An unfortunate reality of this normal was that no doctor would be able to relate to me, and my health care would focus on limitations rather than possibilities.

I focused on school as a distraction and slowly warmed to the idea of pursuing medicine as a career. The seed was planted years prior by the numerous doctors’ visits and procedures, and was cultivated by a desire to understand pathologies and offer treatment to patients from the perspective of a patient. When I applied to medical school, I did not know how to address my CP. Living as a person with CP was a core reason for my decision to pursue medicine, but I was afraid that a disclosure of disability would preclude any admission to medical school. Research into programs offered little guidance because most institutions only listed vague “physical expectations” of each student. There were times I doubted if I would be accepted anywhere. Many programs I reached out to about my situation seemed unenthusiastic about the prospect of a student with CP, and when I brought up my CP in interviews, the reaction was often of surprise and an admission that they had forgotten about “that part” of my application. Fortunately, I was accepted to medical school, but still struggled with the fear that one day I would be found out and not allowed to continue. No one in my class or school was like me, and a meeting with an Americans with Disabilities Act coordinator who asked me to reexamine the physical competencies of the school before advancing to clinical clerkships only further reinforced this fear. I decided to fly under the radar and not say anything about my disability to my attendings. I slowly worked my way through clerkships by making do with adapted ways to perform procedures and exams with additional practice and maneuvering at home. I found myself drawn to psychiatry because of the similarities I saw in the patients and myself. I empathized with how the patients struggled with chronic conditions that left them feeling separated from society and how they felt that their diagnosis was something they needed to hide. When medical school ended and I decided to pursue psychiatry, I wanted to share my story to inspire others with a disability to consider medicine as a career given their unique experiences. My experience thus far has been uplifting as my journey has echoed so many others.

A need for greater representation

Disability representation in medicine is needed more than ever. According to the CDC, >60 million adults in the United States (1 in 4) live with a disability.1 Although the physical health disparities are often discussed, there is less conversation surrounding mental health for individuals with disabilities. A 2018 study by Cree et al2 found that approximately 17.4 million adults with disabilities experienced frequent mental distress, defined as reporting ≥14 mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days. Furthermore, compared to individuals without a disability, those with a disability are statistically more likely to have suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts.3 One way to address this disparity is to recruit medical students with disabilities to become physicians with disabilities. Evidence suggests that physicians who are members of groups that are underrepresented in medicine are more likely to deliver care to underrepresented patients.4 However, medical schools and institutions have been slow to address the disparity. A 2019 survey found an estimated 4.6% of medical students responded “yes” when asked if they had a disability, with most students reporting a psychological or attention/hyperactive disorder.5 Existing barriers include restrictive language surrounding technical standards influenced by long-standing vestiges of what a physician should be.6

An opportunity to connect with patients

I now do not see myself as having a secret identity to hide. Although my CP does not give me any superpowers, it has given me the opportunity to connect with my patients and serve as an example of why medical school recruitment and admissions should expand. Psychiatrists have been on the forefront of change in medicine and can shift the perception of a physician. In doing so, we not only enrich our field but also the lives of our patients who may need it most.

1. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, et al. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(32):882-887.

2. Cree RA, Okoro CA, Zack MM, et al. Frequent mental distress among adults, by disability status, disability type, and selected characteristics—United States 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1238-1243.

3. Marlow NM, Xie Z, Tanner R, et al. Association between disability and suicide-related outcomes among US adults. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(6):852-862.

4. Thurmond VB, Kirch DG. Impact of minority physicians on health care. South Med J. 1998;91(11):1009-1013.

5. Meeks LM, Case B, Herzer K, et al. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among US medical schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(20):2022-2024.

6. Stauffer C, Case B, Moreland CJ, et al. Technical standards from newly established medical schools: a review of disability inclusive practices. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2022;9:23821205211072763.

What does a doctor look like? Throughout history, this concept has shifted due to societal norms and increased access to medical education. Today, the idea of a physician has expanded to incorporate a myriad of people; however, stigma still exists in medicine regarding mental illness and disability. I would like to share my personal journey through high school, college, medical school, and now residency, and how my identity and struggles have shaped me into the physician I am today. There are few conversations around disability—especially disability and mental health—in medicine, and through my own advocacy, I have met many students with disability who feel that medical school is unattainable. Additionally, I have met many medical students, residents, and pre-health advisors who are happy for the experience to learn more about a marginalized group in medicine. My hope in sharing my story is to offer a space for conversation about intersectionality within medical communities and how physicians and physicians in training can facilitate that change, regardless of their position or specialty. Additionally, I hope to shed light on the unique mental health needs of patients with disabilities and how mental health clinicians can address those needs.

Perceived weaknesses turned into strengths

“Why do you walk like that?” “What is that brace on your leg?” The early years of my childhood were marked by these questions and others like them. I was the kid with the limp, the kid with a brace on his leg, and the kid who disappeared multiple times a week for doctor’s appointments or physical therapy. I learned to deflect these questions or give nebulous answers about an accident or injury. The reality is that I was born with cerebral palsy (CP). My CP manifested as hemiparesis on the left side of my body. I was in aggressive physical therapy throughout childhood, received Botox injections for muscle spasticity, and underwent corrective surgery on my left leg to straighten my foot. In childhood, the diagnosis meant nothing more than 2 words that sounded like they belonged to superheroes in comic books. Even with supportive parents and family, I kept my disability a secret, much like the powers and abilities of my favorite superheroes.

However, like all great origin stories, what I once thought were weaknesses turned out to be strengths that pushed me through college, medical school, and now psychiatry residency. Living with a disability has shaped how I see the world and relate to my patients. My experience has helped me connect to my patients in ways others might not. These properties are important in any physician but vital in psychiatry, where many patients feel neglected or stigmatized; this is another reason there should be more doctors with disabilities in medicine. Unfortunately, systemic barriers are still in place that disincentivize those with a disability from pursuing careers in medicine. Stories like mine are important to inspire a reexamination of what a physician should be and how medicine, patients, and communities benefit from this change.

My experience through medical school

My path to psychiatry and residency was shaped by my early experience with the medical field and treatment. From the early days of my diagnosis at age 4, I was told that my brain was “wired differently” and that, because of this disruption in circuitry, I would have difficulty with physical activity. I grew to appreciate the intricacies of the brain and pathology to understand my body. With greater understanding came the existential realization that I would live with a disability for the rest of my life. Rather than dream of a future where I would be “normal,” I focused on adapting my life to my normal. An unfortunate reality of this normal was that no doctor would be able to relate to me, and my health care would focus on limitations rather than possibilities.

I focused on school as a distraction and slowly warmed to the idea of pursuing medicine as a career. The seed was planted years prior by the numerous doctors’ visits and procedures, and was cultivated by a desire to understand pathologies and offer treatment to patients from the perspective of a patient. When I applied to medical school, I did not know how to address my CP. Living as a person with CP was a core reason for my decision to pursue medicine, but I was afraid that a disclosure of disability would preclude any admission to medical school. Research into programs offered little guidance because most institutions only listed vague “physical expectations” of each student. There were times I doubted if I would be accepted anywhere. Many programs I reached out to about my situation seemed unenthusiastic about the prospect of a student with CP, and when I brought up my CP in interviews, the reaction was often of surprise and an admission that they had forgotten about “that part” of my application. Fortunately, I was accepted to medical school, but still struggled with the fear that one day I would be found out and not allowed to continue. No one in my class or school was like me, and a meeting with an Americans with Disabilities Act coordinator who asked me to reexamine the physical competencies of the school before advancing to clinical clerkships only further reinforced this fear. I decided to fly under the radar and not say anything about my disability to my attendings. I slowly worked my way through clerkships by making do with adapted ways to perform procedures and exams with additional practice and maneuvering at home. I found myself drawn to psychiatry because of the similarities I saw in the patients and myself. I empathized with how the patients struggled with chronic conditions that left them feeling separated from society and how they felt that their diagnosis was something they needed to hide. When medical school ended and I decided to pursue psychiatry, I wanted to share my story to inspire others with a disability to consider medicine as a career given their unique experiences. My experience thus far has been uplifting as my journey has echoed so many others.

A need for greater representation

Disability representation in medicine is needed more than ever. According to the CDC, >60 million adults in the United States (1 in 4) live with a disability.1 Although the physical health disparities are often discussed, there is less conversation surrounding mental health for individuals with disabilities. A 2018 study by Cree et al2 found that approximately 17.4 million adults with disabilities experienced frequent mental distress, defined as reporting ≥14 mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days. Furthermore, compared to individuals without a disability, those with a disability are statistically more likely to have suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts.3 One way to address this disparity is to recruit medical students with disabilities to become physicians with disabilities. Evidence suggests that physicians who are members of groups that are underrepresented in medicine are more likely to deliver care to underrepresented patients.4 However, medical schools and institutions have been slow to address the disparity. A 2019 survey found an estimated 4.6% of medical students responded “yes” when asked if they had a disability, with most students reporting a psychological or attention/hyperactive disorder.5 Existing barriers include restrictive language surrounding technical standards influenced by long-standing vestiges of what a physician should be.6

An opportunity to connect with patients

I now do not see myself as having a secret identity to hide. Although my CP does not give me any superpowers, it has given me the opportunity to connect with my patients and serve as an example of why medical school recruitment and admissions should expand. Psychiatrists have been on the forefront of change in medicine and can shift the perception of a physician. In doing so, we not only enrich our field but also the lives of our patients who may need it most.

What does a doctor look like? Throughout history, this concept has shifted due to societal norms and increased access to medical education. Today, the idea of a physician has expanded to incorporate a myriad of people; however, stigma still exists in medicine regarding mental illness and disability. I would like to share my personal journey through high school, college, medical school, and now residency, and how my identity and struggles have shaped me into the physician I am today. There are few conversations around disability—especially disability and mental health—in medicine, and through my own advocacy, I have met many students with disability who feel that medical school is unattainable. Additionally, I have met many medical students, residents, and pre-health advisors who are happy for the experience to learn more about a marginalized group in medicine. My hope in sharing my story is to offer a space for conversation about intersectionality within medical communities and how physicians and physicians in training can facilitate that change, regardless of their position or specialty. Additionally, I hope to shed light on the unique mental health needs of patients with disabilities and how mental health clinicians can address those needs.

Perceived weaknesses turned into strengths

“Why do you walk like that?” “What is that brace on your leg?” The early years of my childhood were marked by these questions and others like them. I was the kid with the limp, the kid with a brace on his leg, and the kid who disappeared multiple times a week for doctor’s appointments or physical therapy. I learned to deflect these questions or give nebulous answers about an accident or injury. The reality is that I was born with cerebral palsy (CP). My CP manifested as hemiparesis on the left side of my body. I was in aggressive physical therapy throughout childhood, received Botox injections for muscle spasticity, and underwent corrective surgery on my left leg to straighten my foot. In childhood, the diagnosis meant nothing more than 2 words that sounded like they belonged to superheroes in comic books. Even with supportive parents and family, I kept my disability a secret, much like the powers and abilities of my favorite superheroes.

However, like all great origin stories, what I once thought were weaknesses turned out to be strengths that pushed me through college, medical school, and now psychiatry residency. Living with a disability has shaped how I see the world and relate to my patients. My experience has helped me connect to my patients in ways others might not. These properties are important in any physician but vital in psychiatry, where many patients feel neglected or stigmatized; this is another reason there should be more doctors with disabilities in medicine. Unfortunately, systemic barriers are still in place that disincentivize those with a disability from pursuing careers in medicine. Stories like mine are important to inspire a reexamination of what a physician should be and how medicine, patients, and communities benefit from this change.

My experience through medical school

My path to psychiatry and residency was shaped by my early experience with the medical field and treatment. From the early days of my diagnosis at age 4, I was told that my brain was “wired differently” and that, because of this disruption in circuitry, I would have difficulty with physical activity. I grew to appreciate the intricacies of the brain and pathology to understand my body. With greater understanding came the existential realization that I would live with a disability for the rest of my life. Rather than dream of a future where I would be “normal,” I focused on adapting my life to my normal. An unfortunate reality of this normal was that no doctor would be able to relate to me, and my health care would focus on limitations rather than possibilities.

I focused on school as a distraction and slowly warmed to the idea of pursuing medicine as a career. The seed was planted years prior by the numerous doctors’ visits and procedures, and was cultivated by a desire to understand pathologies and offer treatment to patients from the perspective of a patient. When I applied to medical school, I did not know how to address my CP. Living as a person with CP was a core reason for my decision to pursue medicine, but I was afraid that a disclosure of disability would preclude any admission to medical school. Research into programs offered little guidance because most institutions only listed vague “physical expectations” of each student. There were times I doubted if I would be accepted anywhere. Many programs I reached out to about my situation seemed unenthusiastic about the prospect of a student with CP, and when I brought up my CP in interviews, the reaction was often of surprise and an admission that they had forgotten about “that part” of my application. Fortunately, I was accepted to medical school, but still struggled with the fear that one day I would be found out and not allowed to continue. No one in my class or school was like me, and a meeting with an Americans with Disabilities Act coordinator who asked me to reexamine the physical competencies of the school before advancing to clinical clerkships only further reinforced this fear. I decided to fly under the radar and not say anything about my disability to my attendings. I slowly worked my way through clerkships by making do with adapted ways to perform procedures and exams with additional practice and maneuvering at home. I found myself drawn to psychiatry because of the similarities I saw in the patients and myself. I empathized with how the patients struggled with chronic conditions that left them feeling separated from society and how they felt that their diagnosis was something they needed to hide. When medical school ended and I decided to pursue psychiatry, I wanted to share my story to inspire others with a disability to consider medicine as a career given their unique experiences. My experience thus far has been uplifting as my journey has echoed so many others.

A need for greater representation

Disability representation in medicine is needed more than ever. According to the CDC, >60 million adults in the United States (1 in 4) live with a disability.1 Although the physical health disparities are often discussed, there is less conversation surrounding mental health for individuals with disabilities. A 2018 study by Cree et al2 found that approximately 17.4 million adults with disabilities experienced frequent mental distress, defined as reporting ≥14 mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days. Furthermore, compared to individuals without a disability, those with a disability are statistically more likely to have suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicide attempts.3 One way to address this disparity is to recruit medical students with disabilities to become physicians with disabilities. Evidence suggests that physicians who are members of groups that are underrepresented in medicine are more likely to deliver care to underrepresented patients.4 However, medical schools and institutions have been slow to address the disparity. A 2019 survey found an estimated 4.6% of medical students responded “yes” when asked if they had a disability, with most students reporting a psychological or attention/hyperactive disorder.5 Existing barriers include restrictive language surrounding technical standards influenced by long-standing vestiges of what a physician should be.6

An opportunity to connect with patients

I now do not see myself as having a secret identity to hide. Although my CP does not give me any superpowers, it has given me the opportunity to connect with my patients and serve as an example of why medical school recruitment and admissions should expand. Psychiatrists have been on the forefront of change in medicine and can shift the perception of a physician. In doing so, we not only enrich our field but also the lives of our patients who may need it most.

1. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, et al. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(32):882-887.

2. Cree RA, Okoro CA, Zack MM, et al. Frequent mental distress among adults, by disability status, disability type, and selected characteristics—United States 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1238-1243.

3. Marlow NM, Xie Z, Tanner R, et al. Association between disability and suicide-related outcomes among US adults. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(6):852-862.

4. Thurmond VB, Kirch DG. Impact of minority physicians on health care. South Med J. 1998;91(11):1009-1013.

5. Meeks LM, Case B, Herzer K, et al. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among US medical schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(20):2022-2024.

6. Stauffer C, Case B, Moreland CJ, et al. Technical standards from newly established medical schools: a review of disability inclusive practices. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2022;9:23821205211072763.

1. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, et al. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(32):882-887.

2. Cree RA, Okoro CA, Zack MM, et al. Frequent mental distress among adults, by disability status, disability type, and selected characteristics—United States 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1238-1243.

3. Marlow NM, Xie Z, Tanner R, et al. Association between disability and suicide-related outcomes among US adults. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(6):852-862.

4. Thurmond VB, Kirch DG. Impact of minority physicians on health care. South Med J. 1998;91(11):1009-1013.

5. Meeks LM, Case B, Herzer K, et al. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among US medical schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(20):2022-2024.

6. Stauffer C, Case B, Moreland CJ, et al. Technical standards from newly established medical schools: a review of disability inclusive practices. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2022;9:23821205211072763.

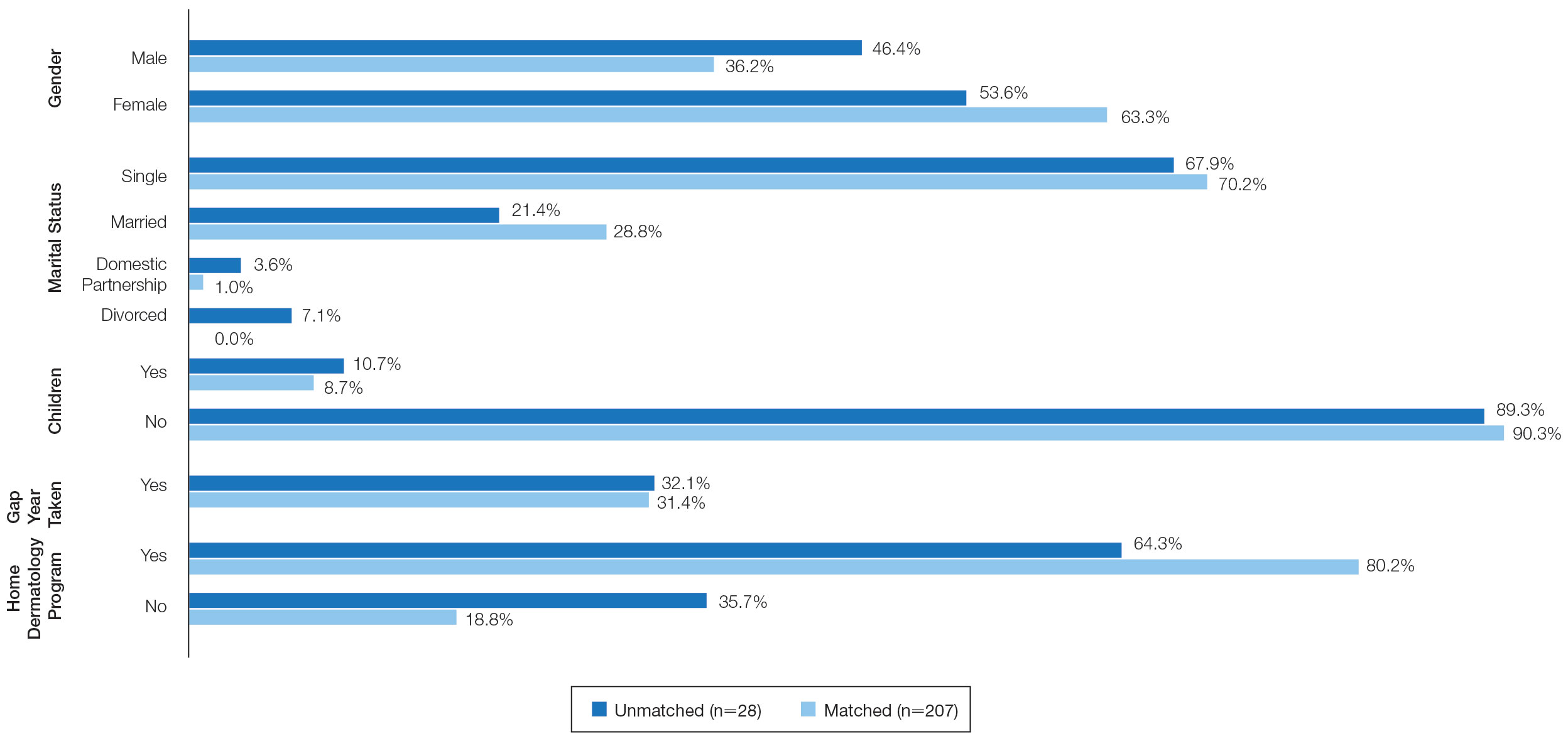

Characteristics of Matched vs Nonmatched Dermatology Applicants

Dermatology residency continues to be one of the most competitive specialties, with a match rate of 84.7% for US allopathic seniors in the 2019-2020 academic year.1 In the 2019-2020 cycle, dermatology applicants were tied with plastic surgery for the highest median US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score compared with other specialties, which suggests that the top medical students are applying, yet only approximately 5 of 6 students are matching.

Factors that have been cited with successful dermatology matching include USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) scores,2 research accomplishments,3 letters of recommendation,4 medical school performance, personal statement, grades in required clerkships, and volunteer/extracurricular experiences, among others.5

The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) publishes data each year regarding different academic factors—USMLE scores; number of abstracts, presentations, and papers; work, volunteer, and research experiences—and compares the mean between matched and nonmatched applicants.1 However, the USMLE does not report any demographic information of the applicants and the implication it has for matching. Additionally, the number of couples participating in the couples match continues to increase each year. In the 2019-2020 cycle, 1224 couples participated in the couples match.1 However, NRMP reports only limited data regarding the couples match, and it is not specialty specific.

We aimed to determine the characteristics of matched vs nonmatched dermatology applicants. Secondarily, we aimed to determine any differences among demographics regarding matching rates, academic performance, and research publications. We also aimed to characterize the strategy and outcomes of applicants that couples matched.

Materials and Methods

The Mayo Clinic institutional review board deemed this study exempt. All applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residency in Scottsdale, Arizona, during the 2018-2019 cycle were emailed an initial survey (N=475) before Match Day that obtained demographic information, geographic information, gap-year information, USMLE Step 1 score, publications, medical school grades, number of away rotations, and number of interviews. A follow-up survey gathering match data and couples matching data was sent to the applicants who completed the first survey on Match Day. The survey was repeated for the 2019-2020 cycle. In the second survey, Step 2 CK data were obtained. The survey was sent to 629 applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residencies in Arizona, Minnesota, and Florida to include a broader group of applicants. For publications, applicants were asked to count only published or accepted manuscripts, not abstracts, posters, conference presentations, or submitted manuscripts. Applicants who did not respond to the second survey (match data) were not included in that part of the analysis. One survey was excluded because of implausible answers (eg, scores outside of range for USMLE Step scores).

Statistical Analysis—For statistical analyses, the applicants from both applications cycles were combined. Descriptive statistics were reported in the form of mean, median, or counts (percentages), as applicable. Means were compared using 2-sided t tests. Group comparisons were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using the BlueSky Statistics version 6.30. P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

In 2019, a total of 149 applicants completed the initial survey (31.4% response rate), and 112 completed the follow-up survey (75.2% response rate). In 2020, a total of 142 applicants completed the initial survey (22.6% response rate), and 124 completed the follow-up survey (87.3% response rate). Combining the 2 years, after removing 1 survey with implausible answers, there were 290 respondents from the initial survey and 235 from the follow-up survey. The median (SD) age for the total applicants over both years was 27 (3.0) years, and 180 applicants were female (61.9%).

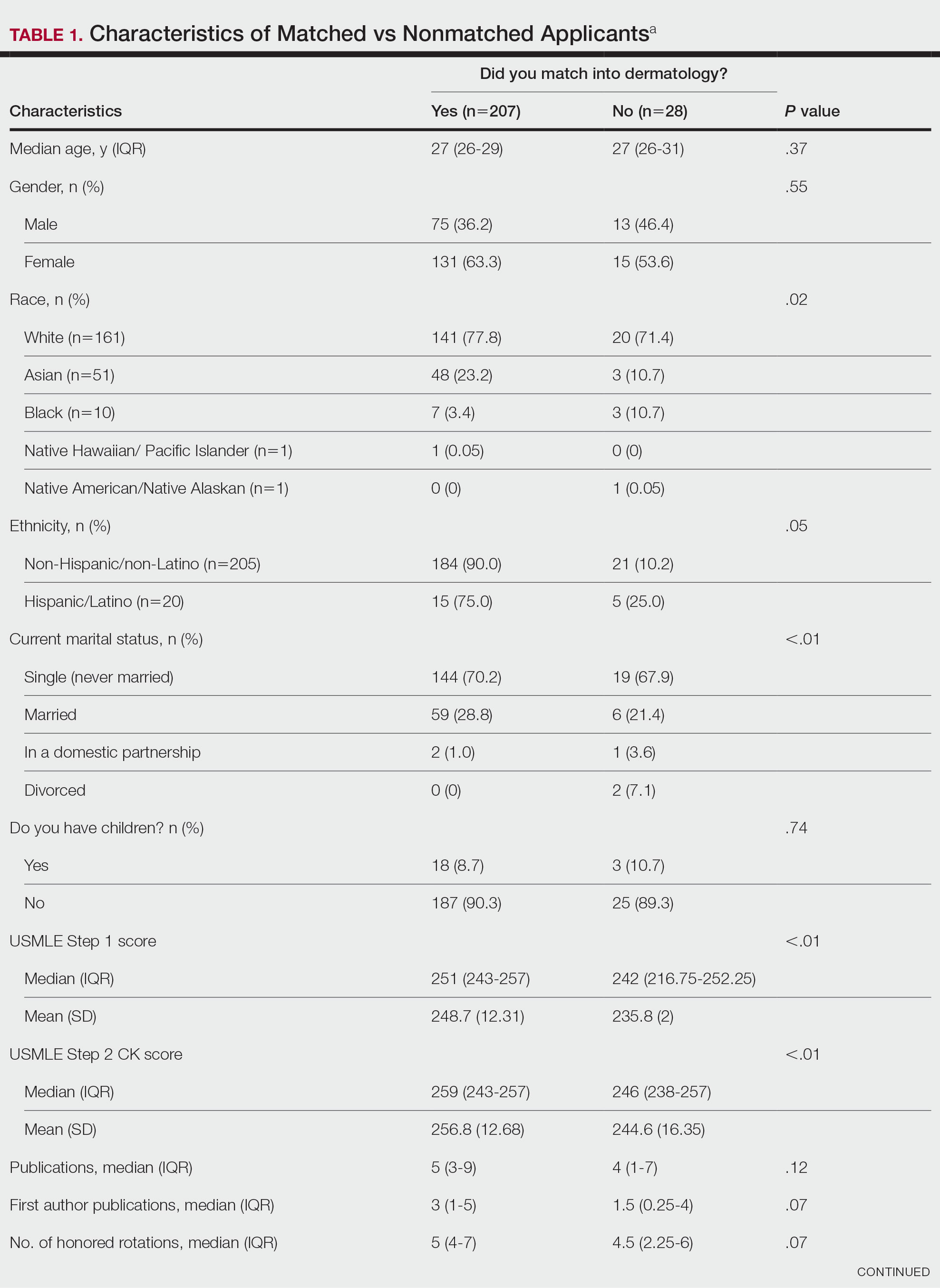

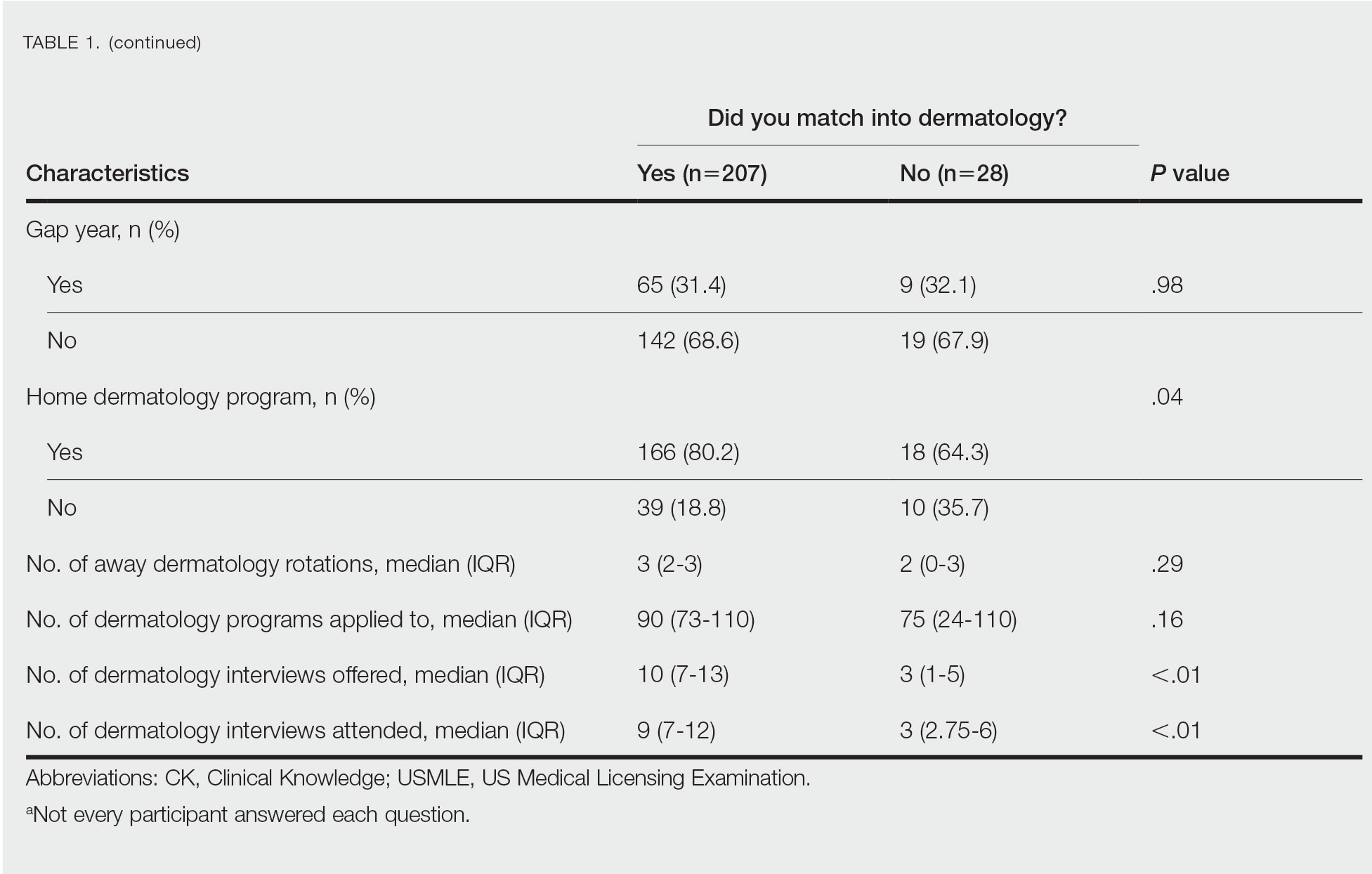

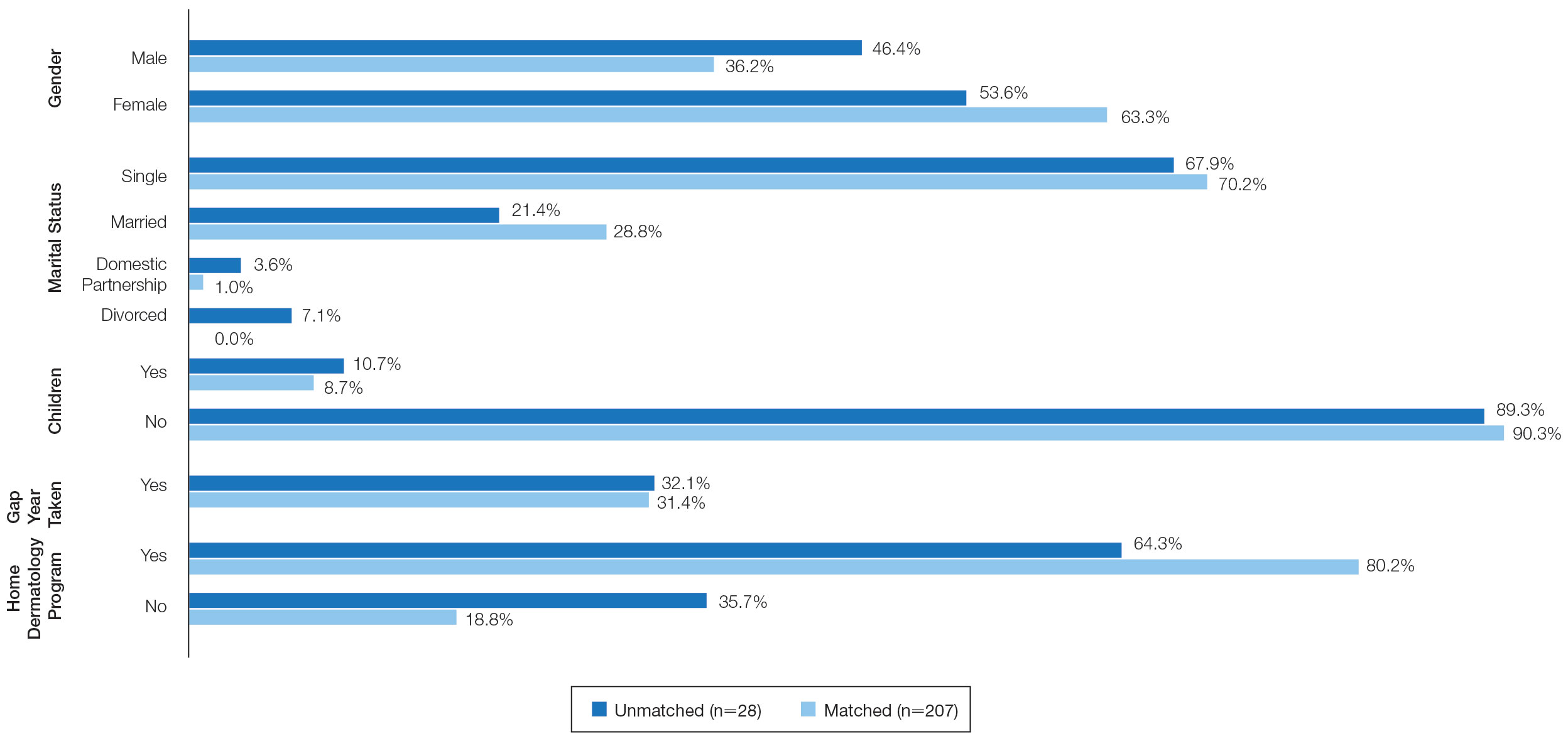

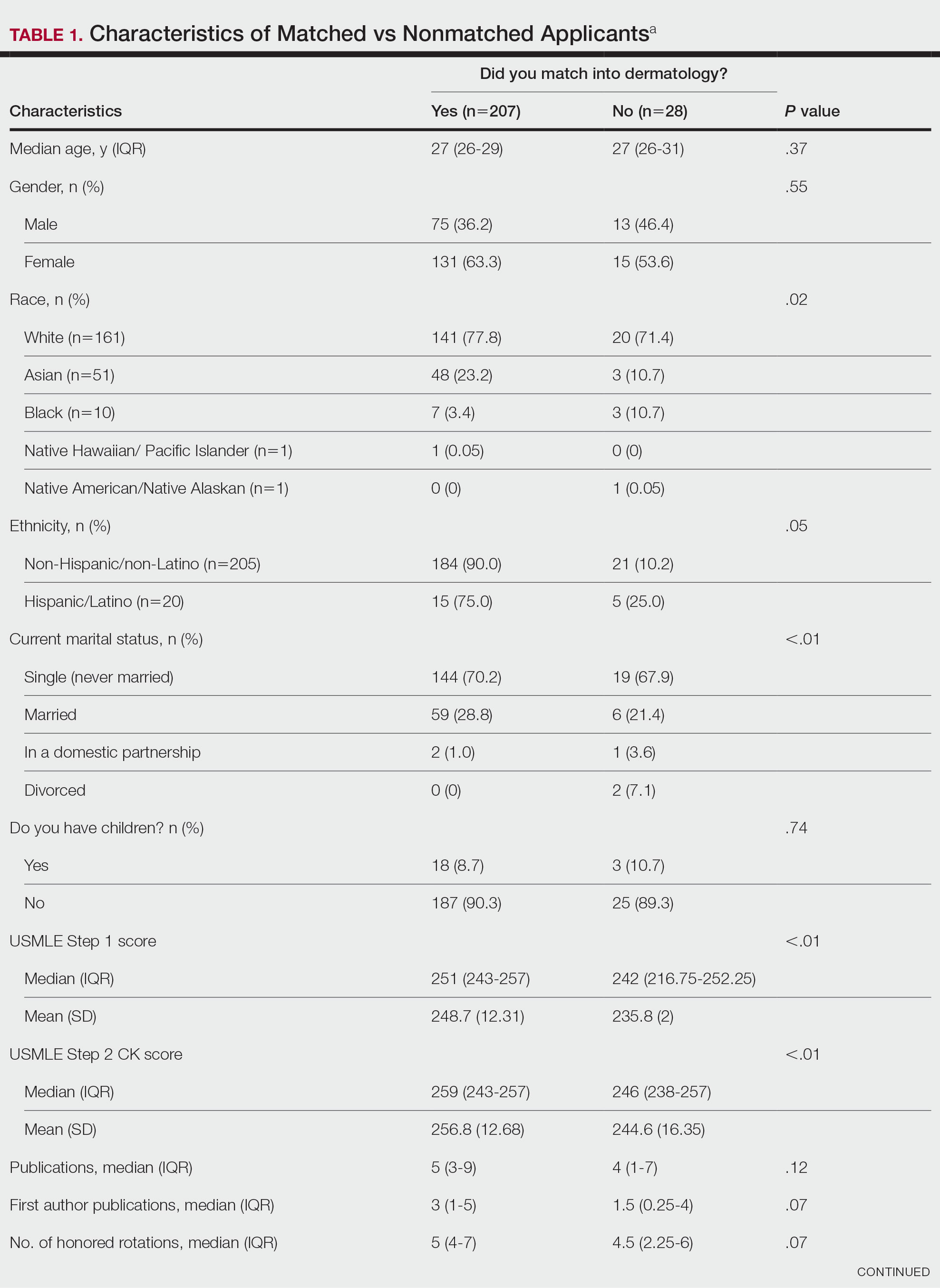

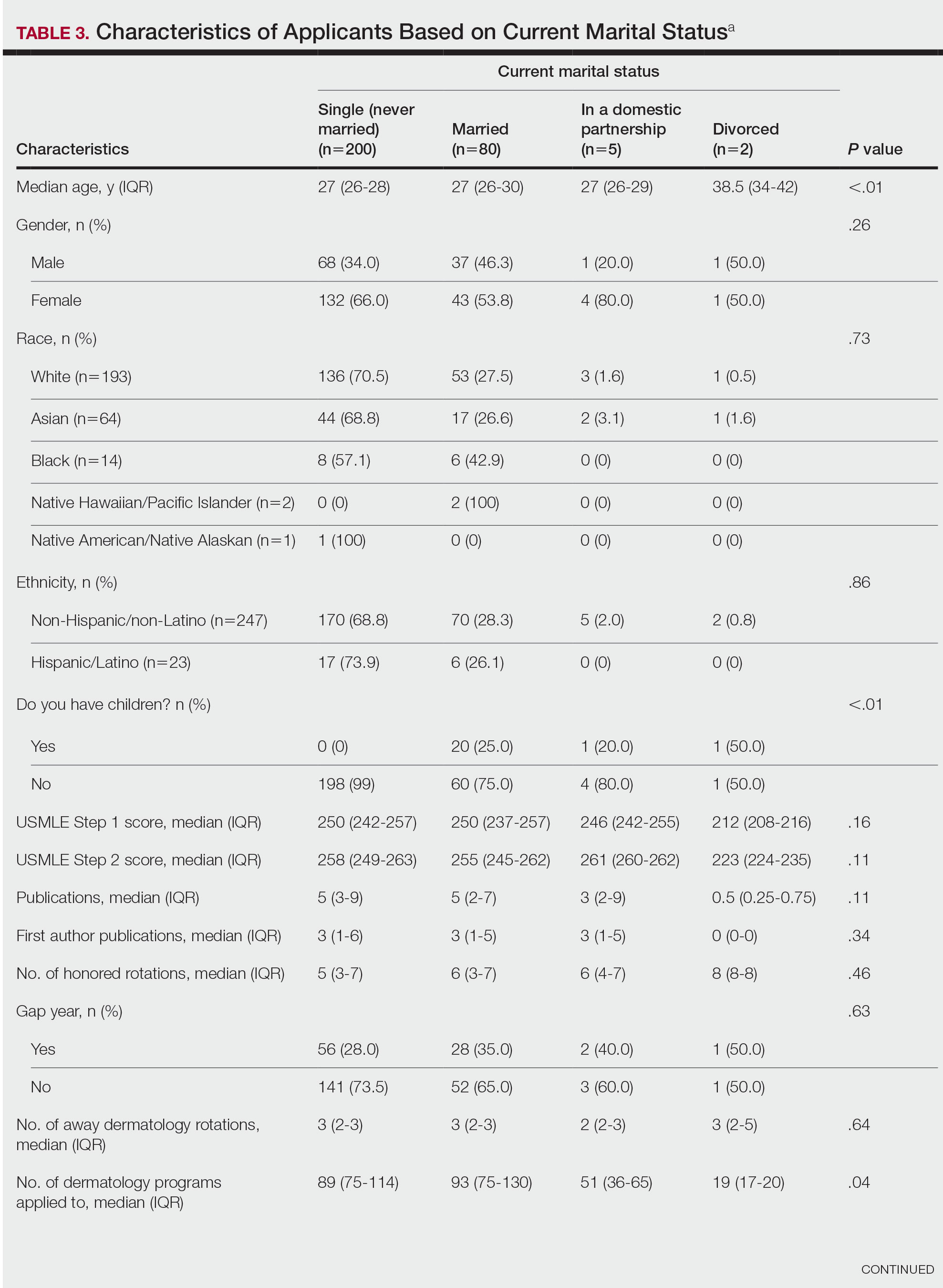

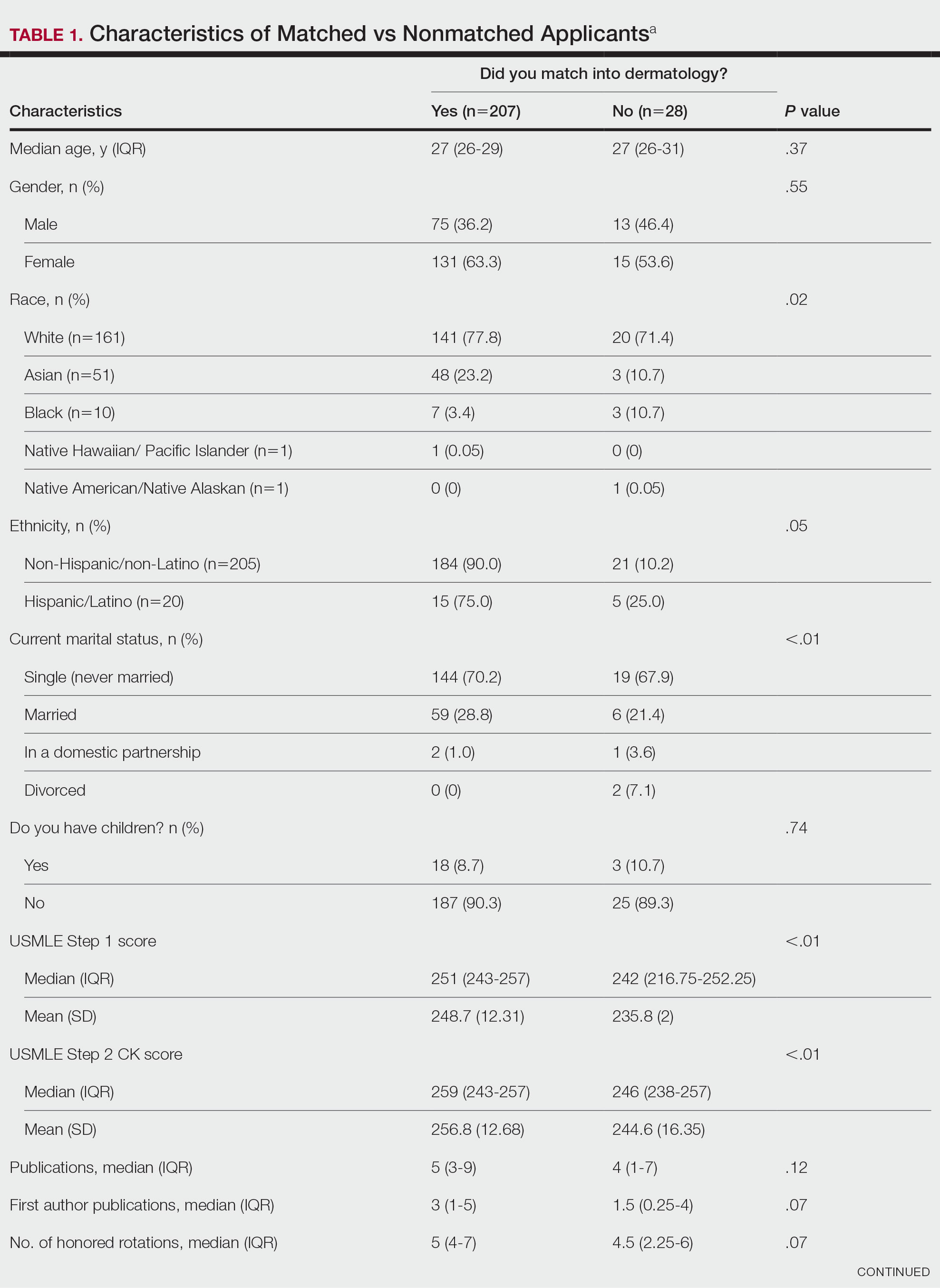

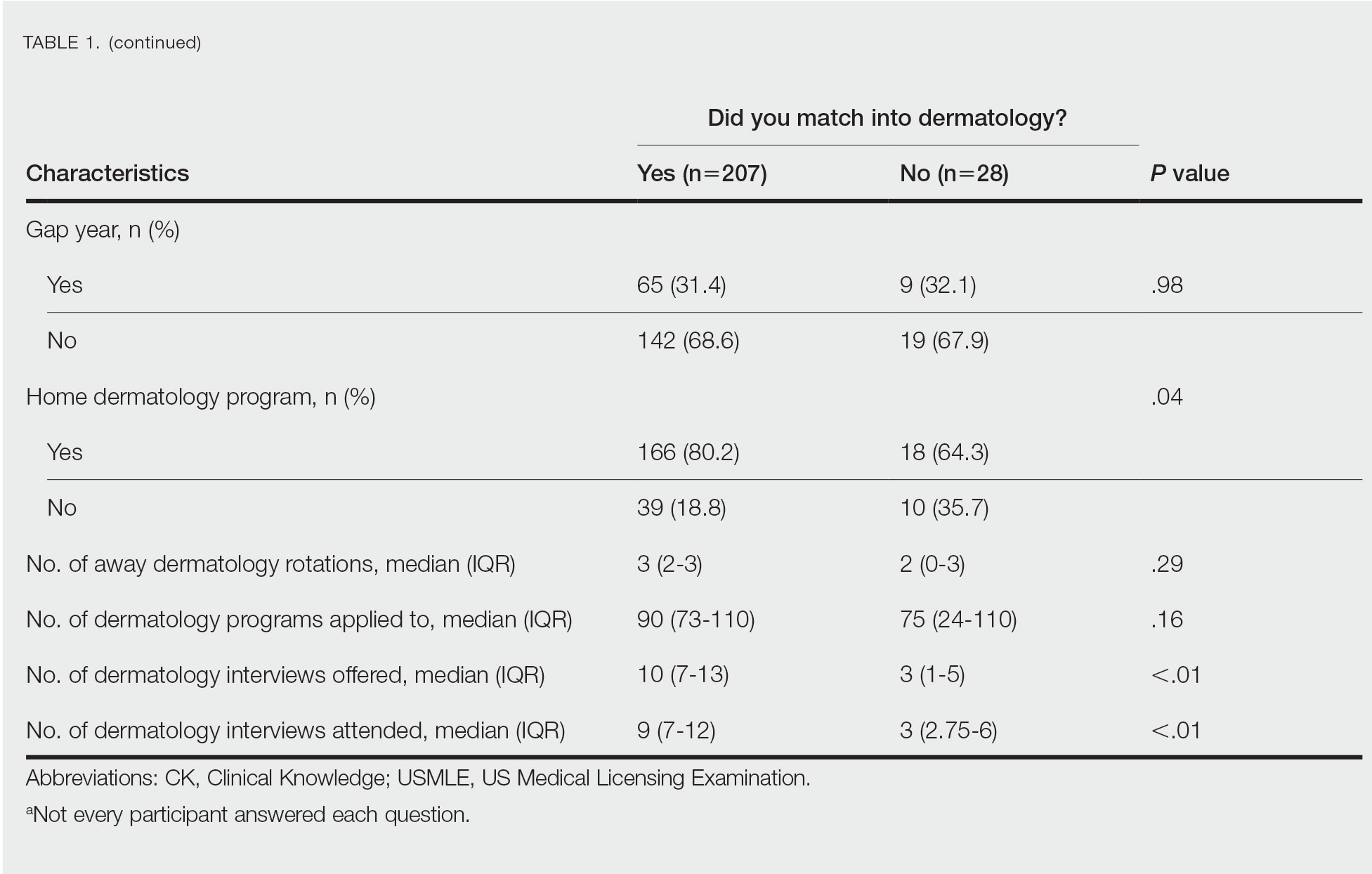

USMLE Scores—The median USMLE Step 1 score was 250, and scores ranged from 196 to 271. The median USMLE Step 2 CK score was 257, and scores ranged from 213 to 281. Higher USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores and more interviews were associated with higher match rates (Table 1). In addition, students with a dermatology program at their medical school were more likely to match than those without a home dermatology program.

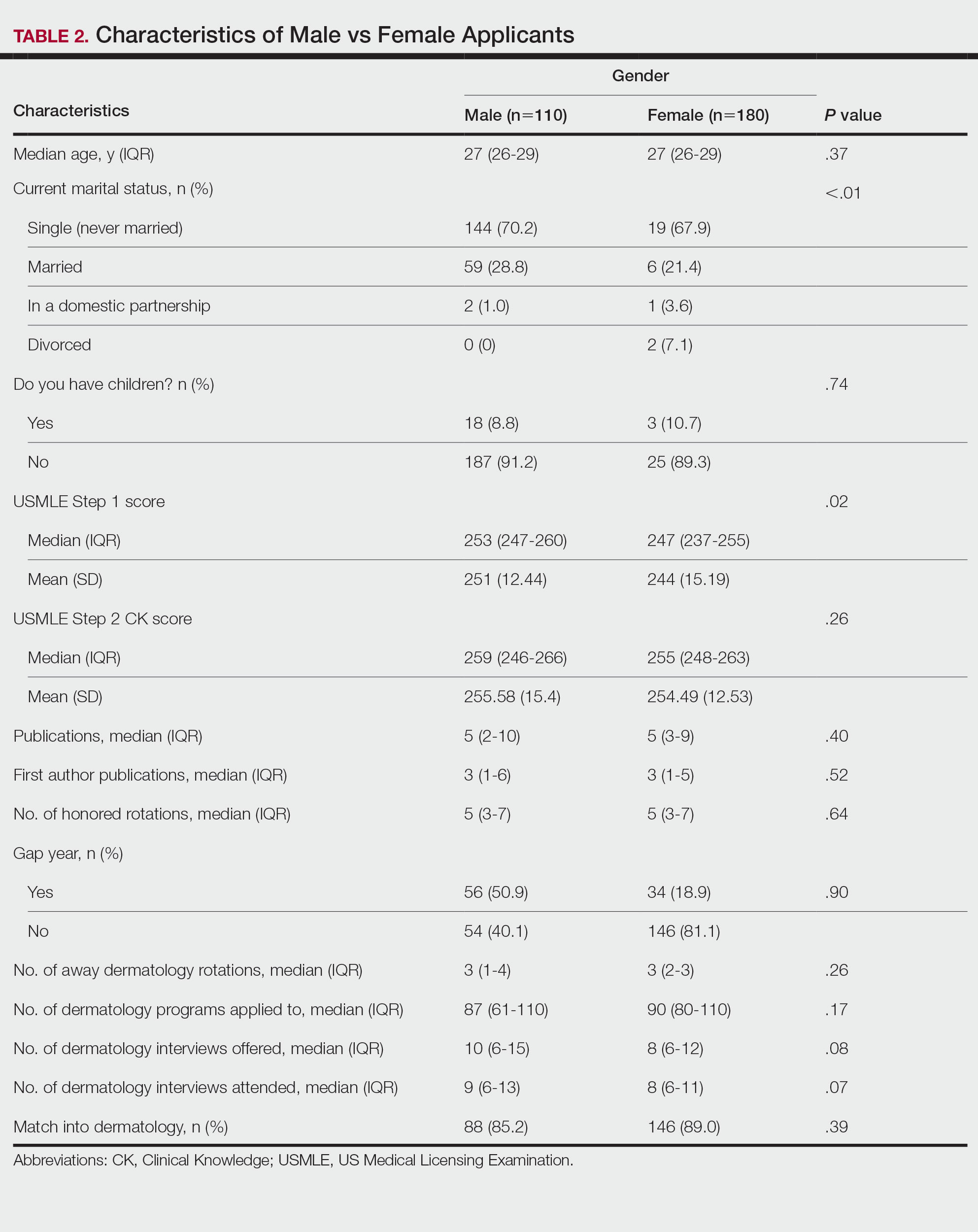

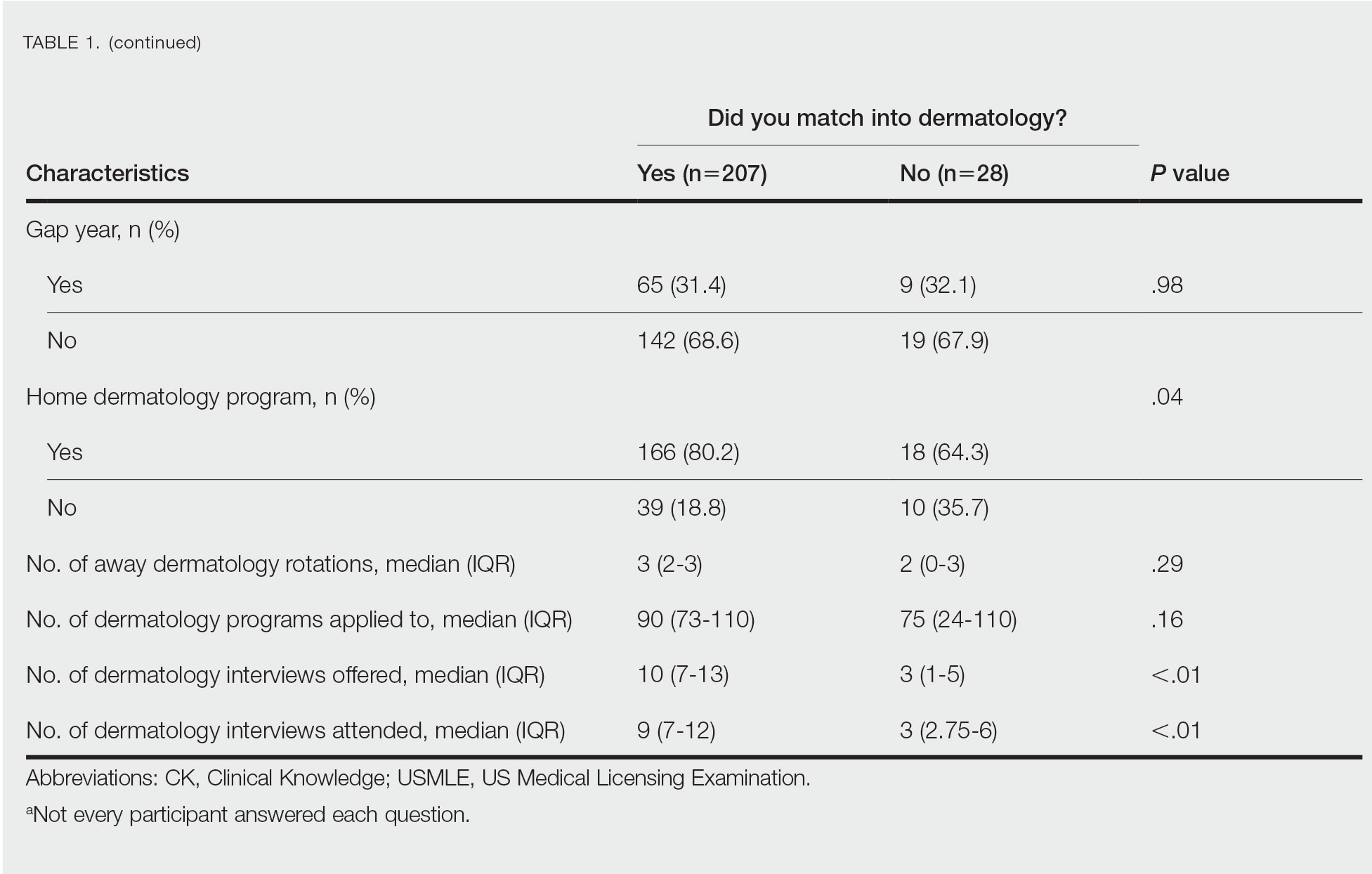

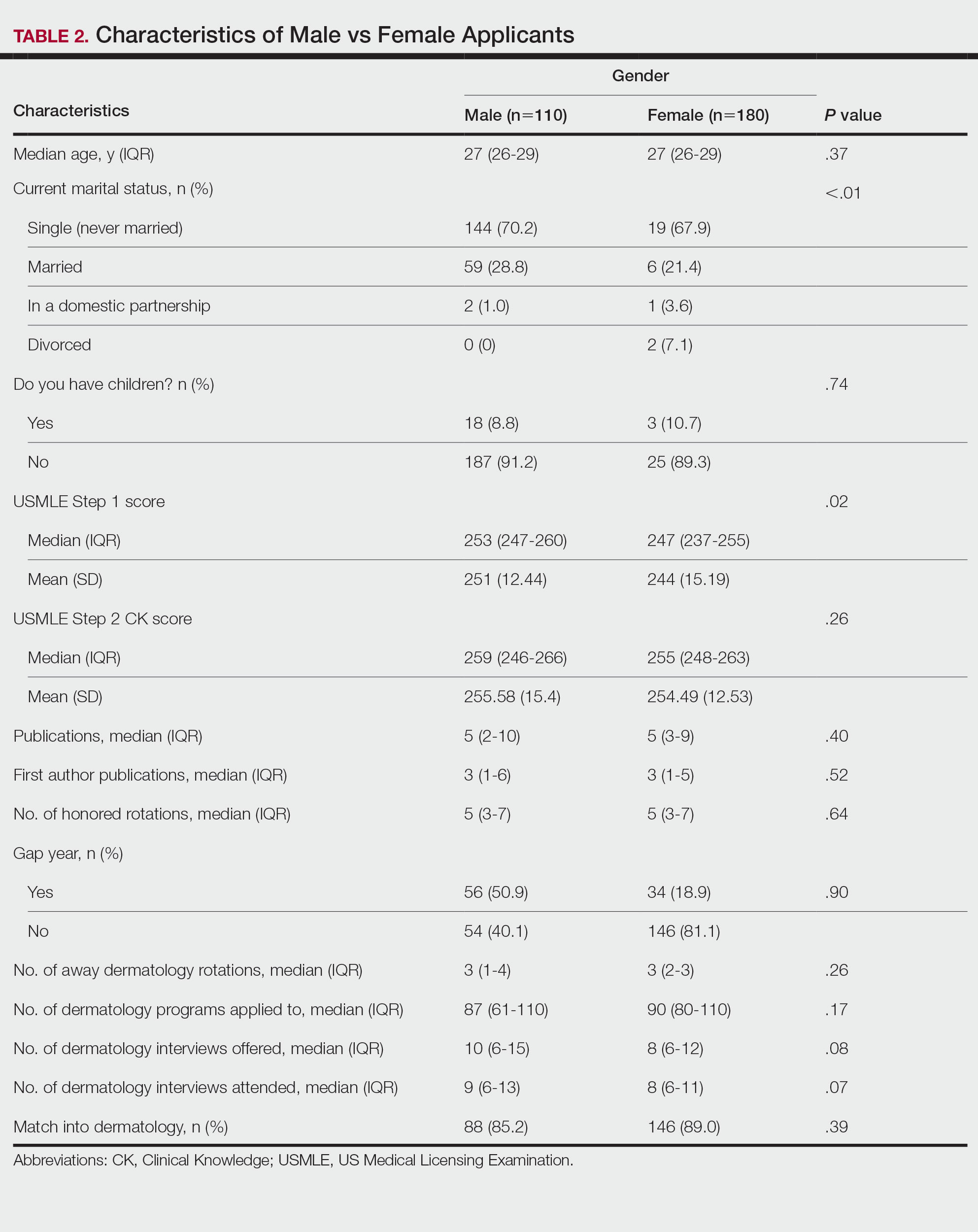

Gender Differences—There were 180 females and 110 males who completed the surveys. Males and females had similar match rates (85.2% vs 89.0%; P=.39)(Table 2).

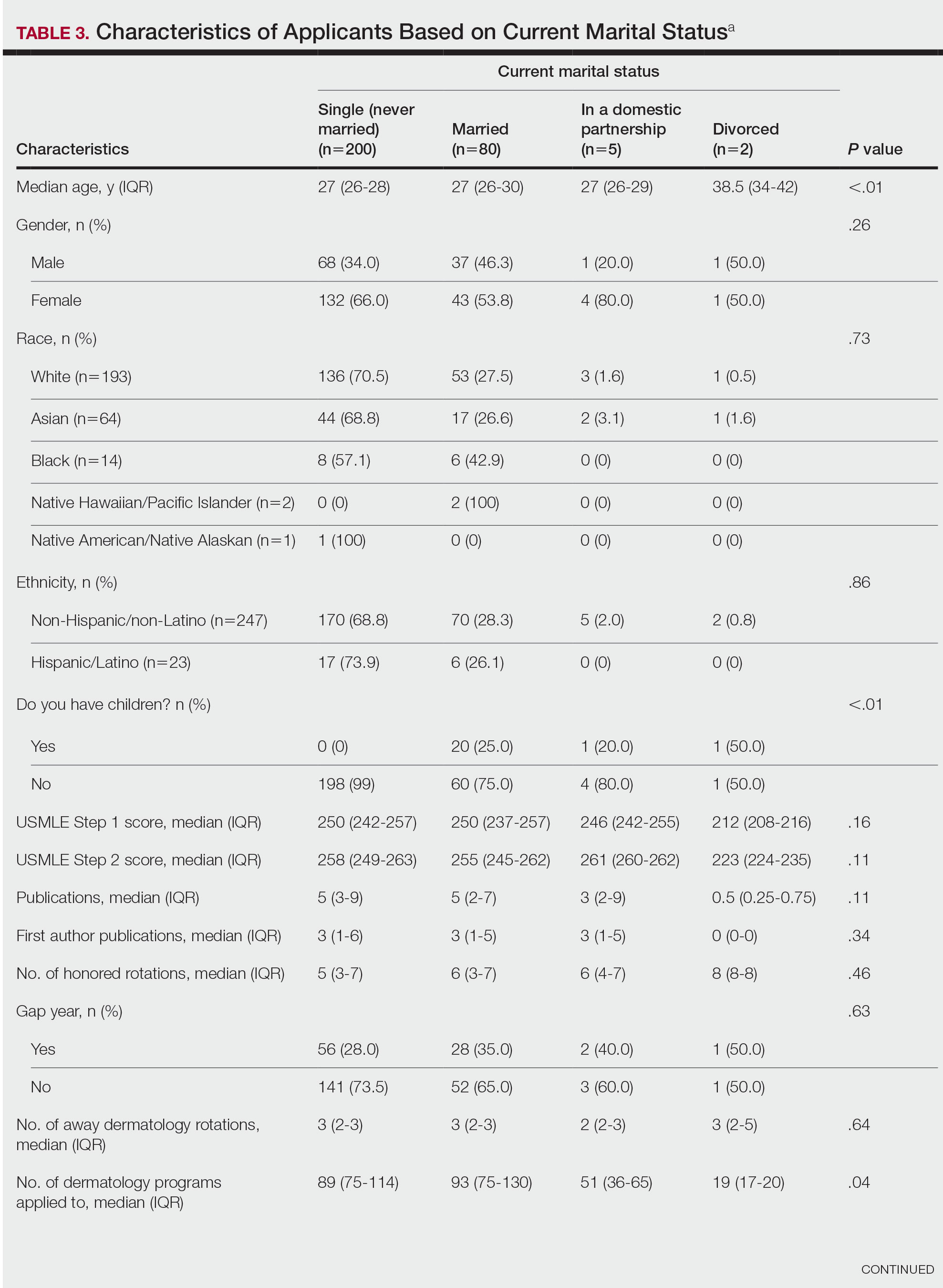

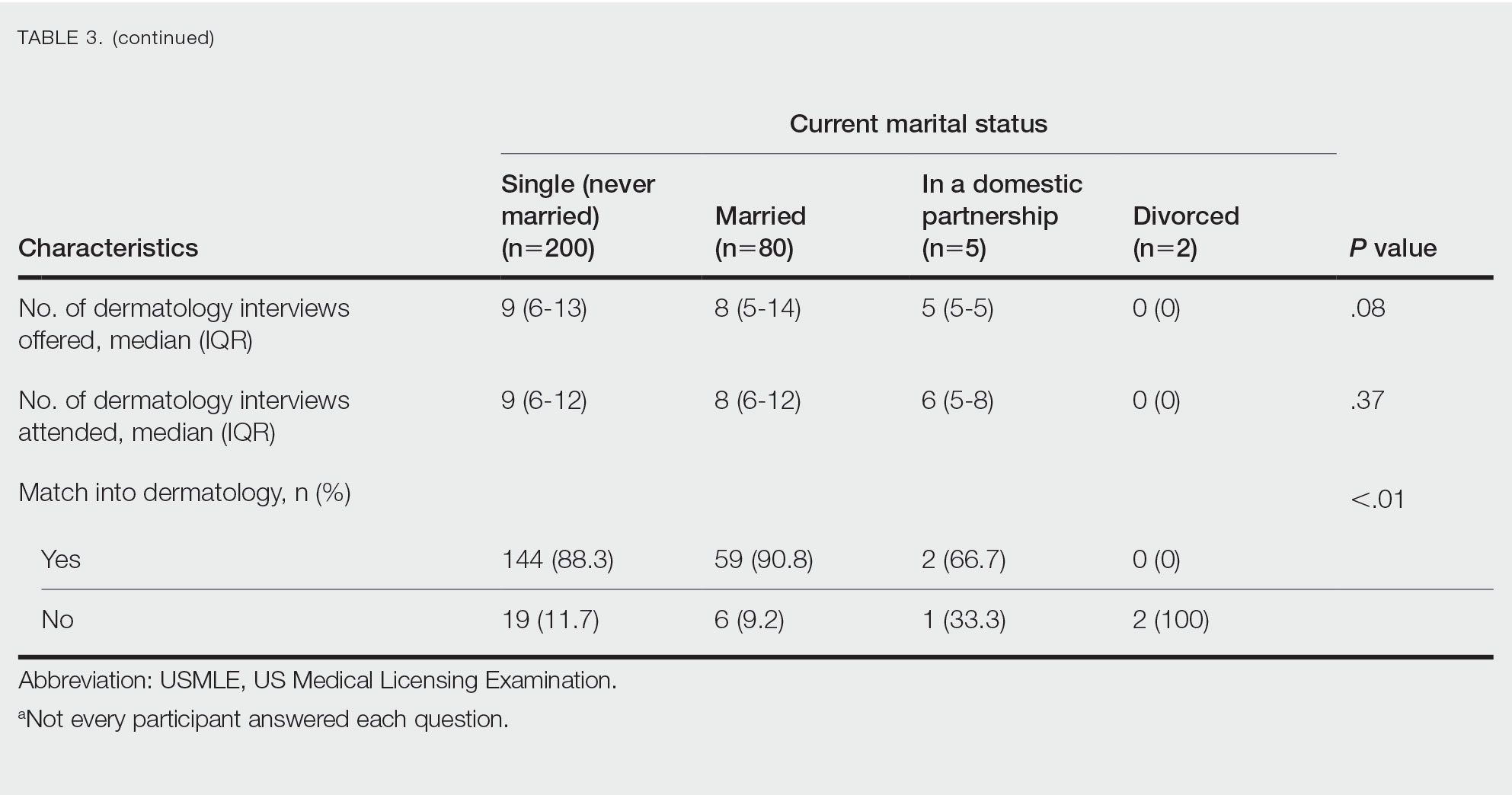

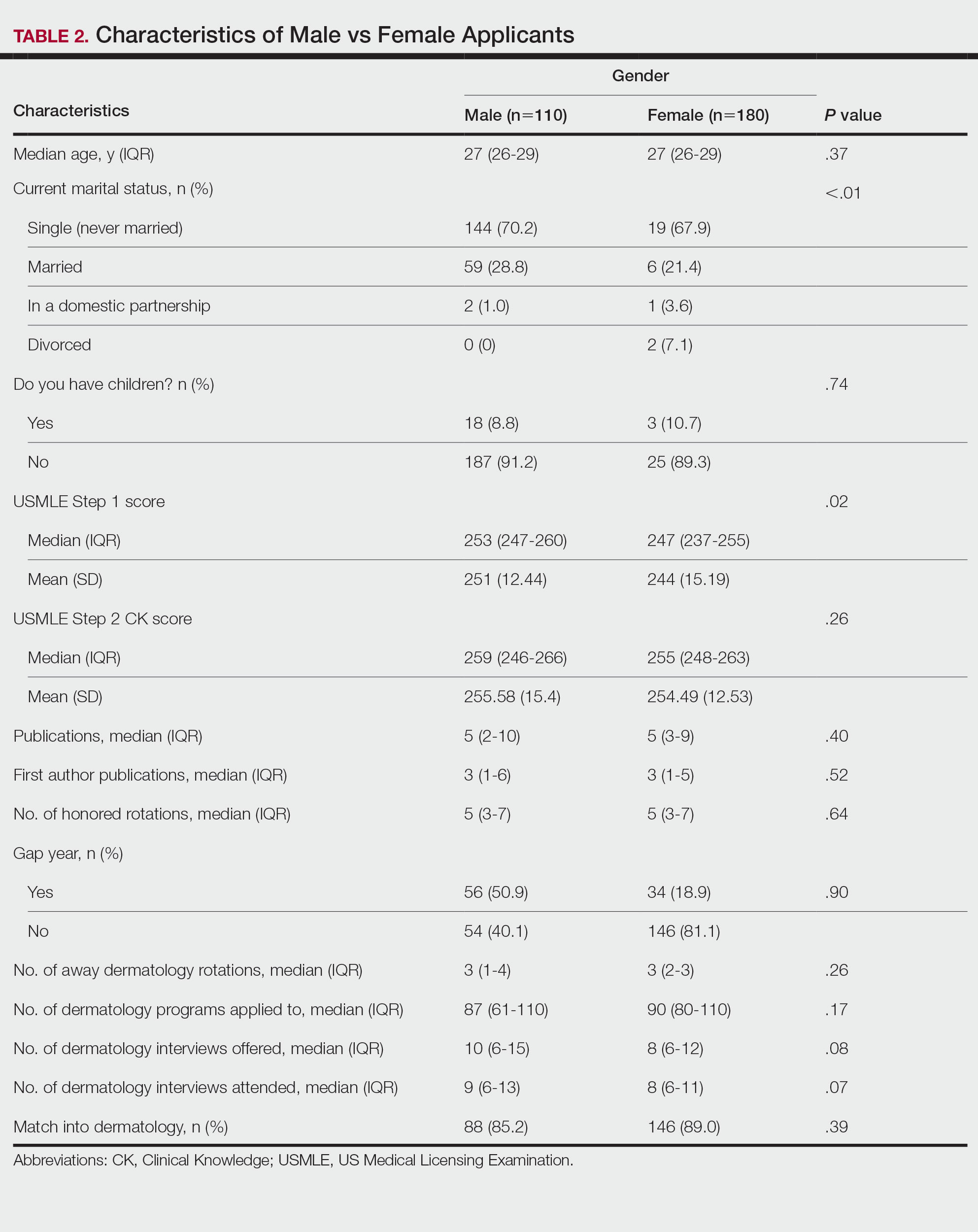

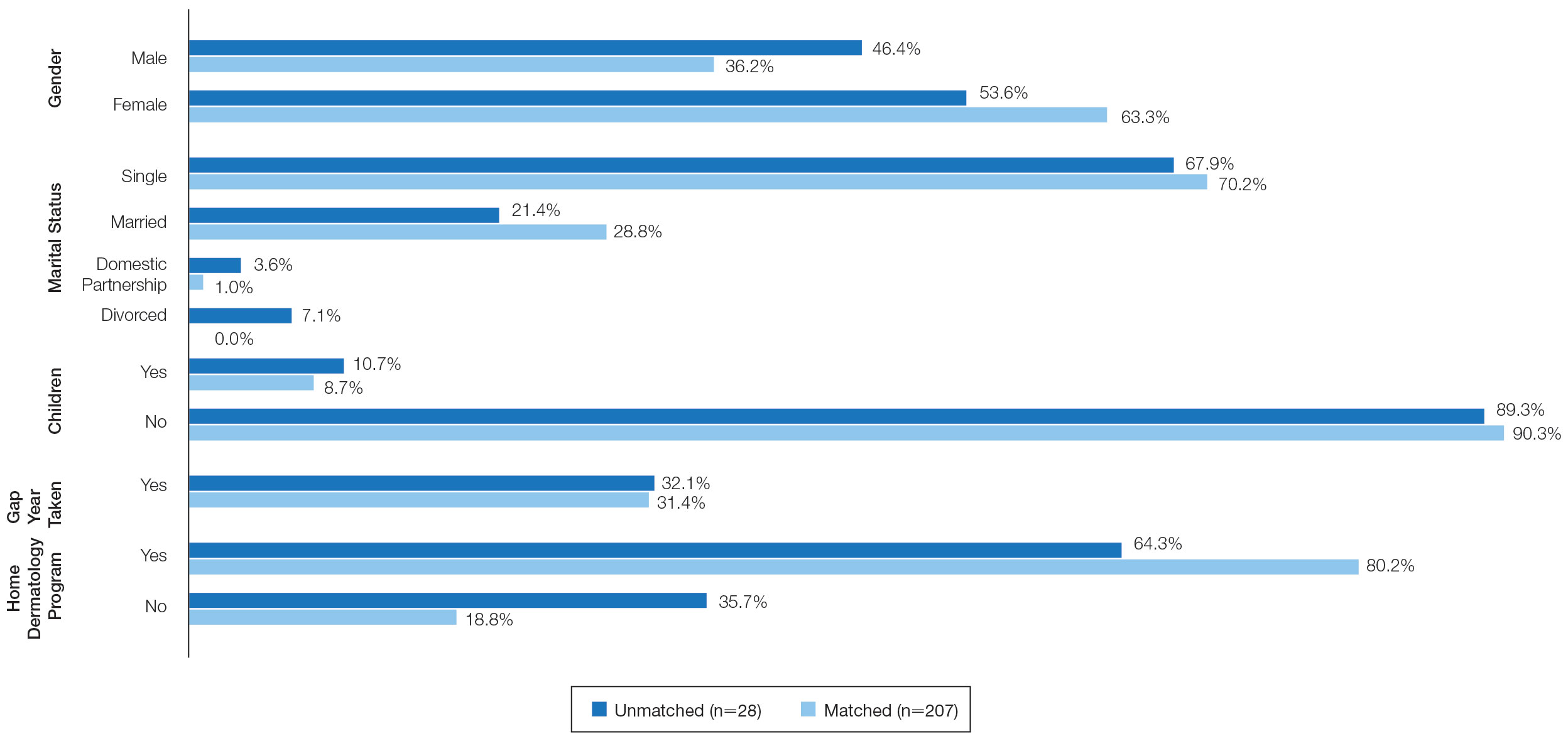

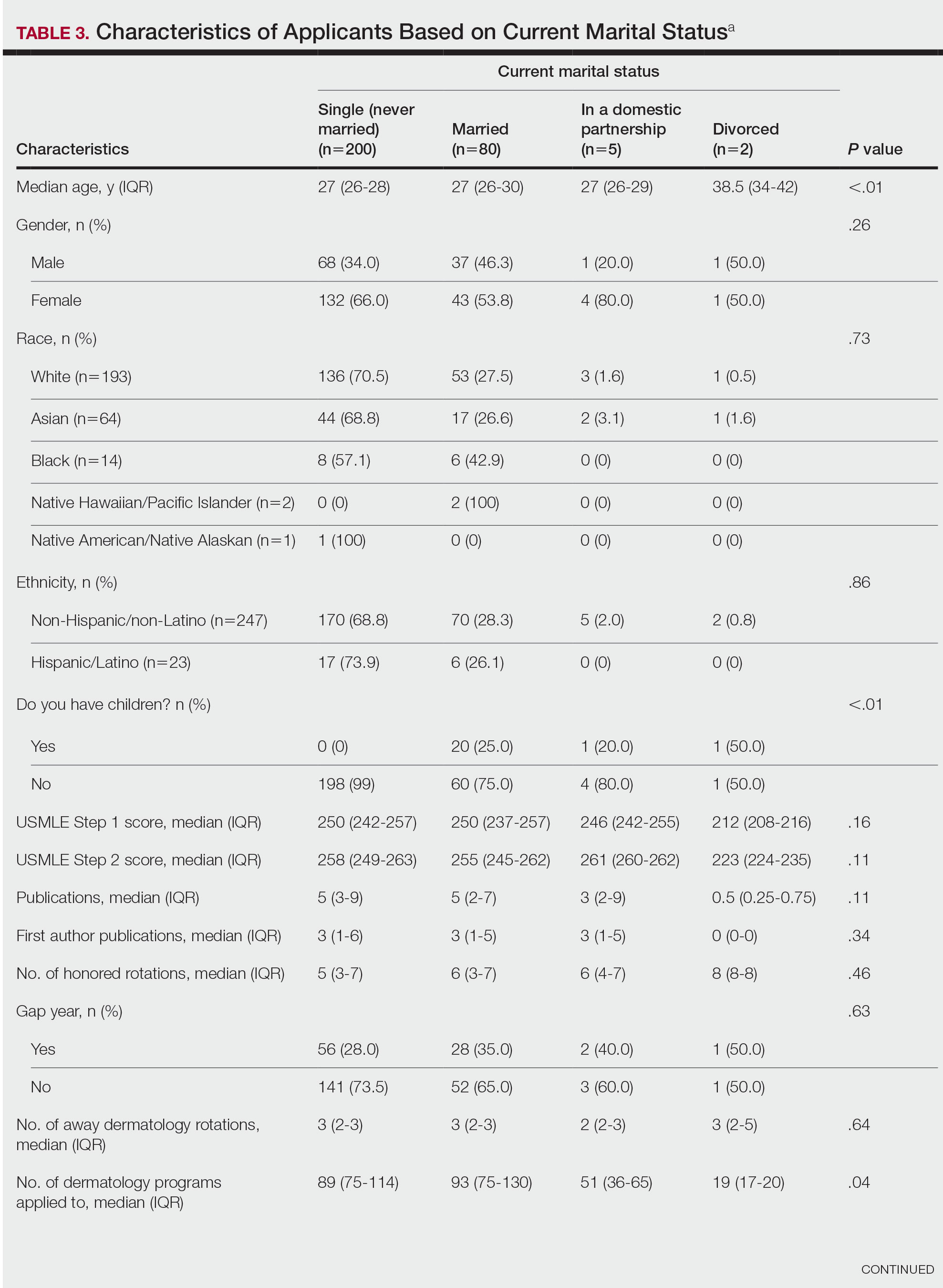

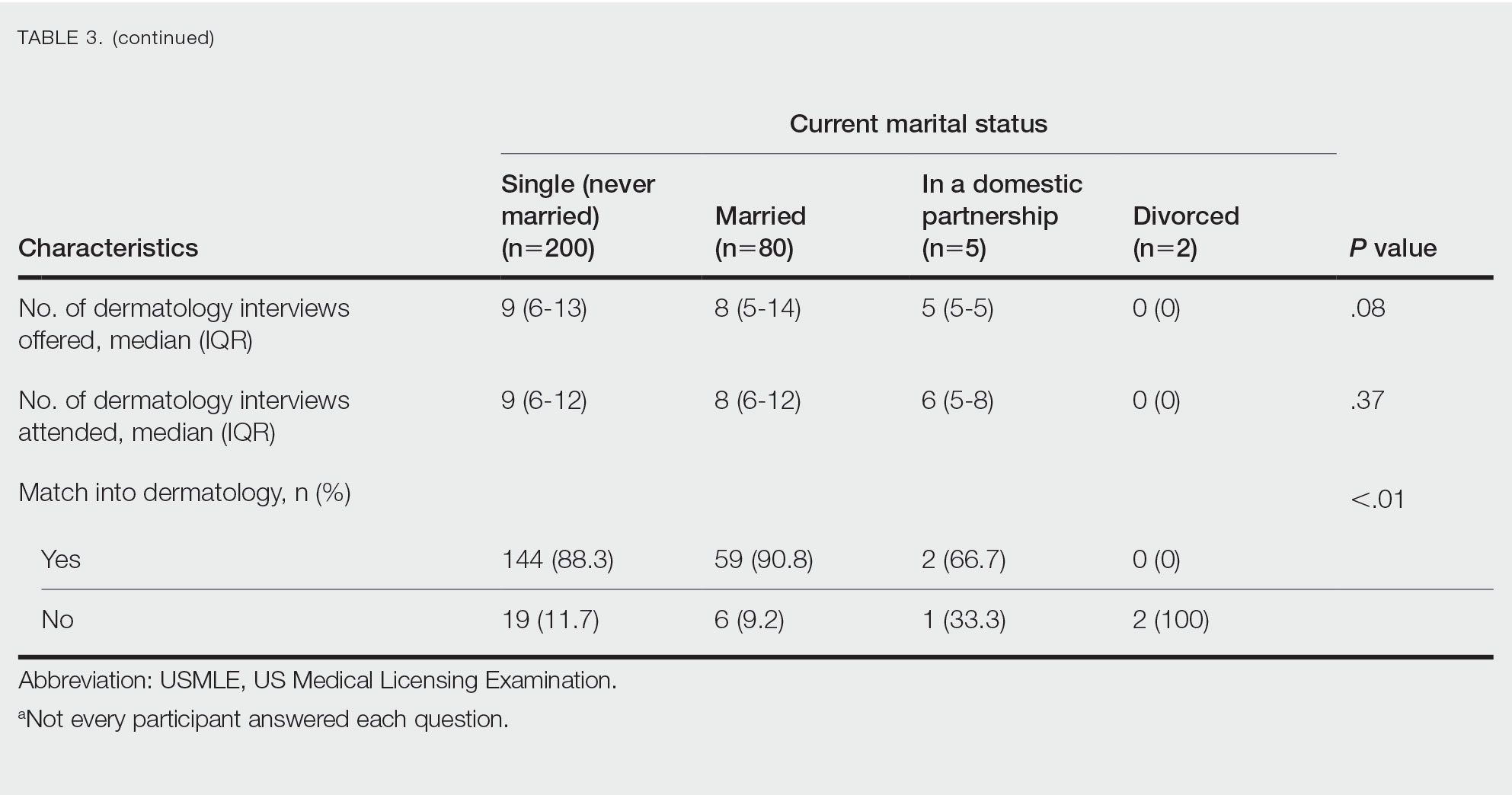

Family Life—In comparing marital status, applicants who were divorced had a higher median age (38.5 years) compared with applicants who were single, married, or in a domestic partnership (all 27 years; P<.01). Differences are outlined in Table 3.

On average, applicants with children (n=27 [15 male, 12 female]; P=.13) were 3 years older than those without (30.5 vs 27; P<.01) and were more likely to be married (88.9% vs 21.5%; P<.01). Applicants with children had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 241 compared to 251 for those without children (P=.02) and a mean USMLE Step 2 CK score of 246 compared to 258 for those without children (P<.01). Applicants with children had similar debt, number of publications, number of honored rotations, and match rates compared to applicants without children (Figure).

Couples Match—Seventeen individuals in our survey participated in the couples match (7.8%), and all 17 (100%) matched into dermatology. The mean age was 26.7 years, 12 applicants were female, 2 applicants were married, and 1 applicant had children. The mean number of interviews offered was 13.6, and the mean number of interviews attended was 11.3. This was higher than participants who were not couples matching (13.6 vs 9.8 [P=.02] and 11.3 vs 8.9 [P=.04], respectively). Applicants and their partners applied to programs and received interviews in a mean of 10 cities. Sixteen applicants reported that they contacted programs where their partner had interview offers. All participants’ rank lists included programs located in different cities than their partners’ ranked programs, and all but 1 participant ranked programs located in a different state than their partners’ ranked programs. Fifteen participants had options in their rank list for the applicant not to match, even if the partner would match. Similarly, 12 had the option for the applicant to match, even if the partner would not match. Fourteen (82.4%) matched at the same institution as their significant other. Three (17.6%) applicants matched to a program in a different state than the partner’s matched program. Two (11.8%) participants felt their relationship with their partner suffered because of the match, and 1 (5.9%) applicant was undetermined. One applicant described their relationship suffering from “unnecessary tension and anxiety” and noted “difficult conversations” about potentially matching into dermatology in a different location from their partner that could have been “devastating and not something [he or she] should have to choose.”

Comment

Factors for Matching in Dermatology—In our survey, we found the statistically significant factors of matching into dermatology included high USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores (P<.01), having a home dermatology program (P=.04), and attending a higher number of dermatology interviews (P<.01). These data are similar to NRMP results1; however, the higher likelihood of matching if the medical school has a home dermatology program has not been reported. This finding could be due to multiple factors such as students have less access to academic dermatologists for research projects, letters of recommendations, mentorship, and clinical rotations.

Gender and having children were factors that had no correlation with the match rate. There was a statistical difference of matching based on marital status (P<.01), but this is likely due to the low number of applicants in the divorced category. There were differences among demographics with USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores, which is a known factor in matching.1,2 Applicants with children had lower USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores compared to applicants without children. Females also had lower median USMLE Step 1 scores compared to males. This finding may serve as a reminder to programs when comparing USMLE Step examination scores that demographic factors may play a role. The race and ethnicity of applicants likely play a role. It has been reported that underrepresented minorities had lower match rates than White and Asian applicants in dermatology.6 There have been several published articles discussing the lack of diversity in dermatology, with a call to action.7-9

Factors for Couples Matching—The number of applicants participating in the couples match continues to increase yearly. The NMRP does publish data regarding “successful” couples matching but does not specify how many couples match together. There also is little published regarding advice for participation in the couples match. Although we had a limited number of couples that participated in the match, it is interesting to note they had similar strategies, including contacting programs at institutions that had offered interviews to their partners. This strategy may be effective, as dermatology programs offer interviews relatively late compared with other specialties.5 Additionally, this strategy may increase the number of interviews offered and received, as evidenced by the higher number of interviews offered compared with those who were not couples matching. Additionally, this survey highlights the sacrifice often needed by couples in the couples match as revealed by the inclusion of rank-list options in which the couples reside long distance or in which 1 partner does not match. This information may be helpful to applicants who are planning a strategy for the couples match in dermatology. Although this study does not encompass all dermatology applicants in the 2019-2020 cycle, we do believe it may be representative. The USMLE Step 1 scores in this study were similar to the published NRMP data.1,10 According to NRMP data from the 2019-2020 cycle, the mean USMLE Step 1 score was 248 for matched applicants and 239 for unmatched.1 The NRMP reported the mean USMLE Step 2 CK score for matched was 256 and 248 for unmatched, which also is similar to our data. The NRMP reported the mean number of programs ranked was 9.9 for matched and 4.5 for unmatched applicants.1 Again, our data were similar for number of dermatology interviews attended.

Limitations—There are limitations to this study. The main limitation is that the survey is from a single institution and had a limited number of respondents. Given the nature of the study, the accuracy of the data is dependent on the applicants’ honesty in self-reporting academic performance and other variables. There also may be a selection bias given the low response rate. The subanalyses—children and couples matching—were underpowered with the limited number of participants. Further studies that include multiple residency programs and multiple years could be helpful to provide more power and less risk of bias. We did not gather information such as the Medical Student Performance Evaluation letter, letters of recommendation, or personal statements, which do play an important role in the assessment of an applicant. However, because the applicants completed these surveys, and given these are largely blinded to applicants, we did not feel the applicants could accurately respond to those aspects of the application.

Conclusion

Our survey finds that factors associated with matching included a higher USMLE Step 1 score, having a home dermatology program, and a higher number of interviews offered and attended. Some demographics had varying USMLE Step 1 scores but similar match rates.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2020. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MM_Results_and-Data_2020-1.pdf

- Gauer JL, Jackson JB. The association of USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores with residency match specialty and location. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1358579.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Wang RF, Zhang M, Kaffenberger JA. Does the dermatology standardized letter of recommendation alter applicants’ chances of matching into residency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:e139-e140.

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants-turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. Characteristics of U.S. allopathic seniors who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2018 main residency match. 2nd ed. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018_Seniors-1.pdf

Dermatology residency continues to be one of the most competitive specialties, with a match rate of 84.7% for US allopathic seniors in the 2019-2020 academic year.1 In the 2019-2020 cycle, dermatology applicants were tied with plastic surgery for the highest median US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score compared with other specialties, which suggests that the top medical students are applying, yet only approximately 5 of 6 students are matching.

Factors that have been cited with successful dermatology matching include USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) scores,2 research accomplishments,3 letters of recommendation,4 medical school performance, personal statement, grades in required clerkships, and volunteer/extracurricular experiences, among others.5

The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) publishes data each year regarding different academic factors—USMLE scores; number of abstracts, presentations, and papers; work, volunteer, and research experiences—and compares the mean between matched and nonmatched applicants.1 However, the USMLE does not report any demographic information of the applicants and the implication it has for matching. Additionally, the number of couples participating in the couples match continues to increase each year. In the 2019-2020 cycle, 1224 couples participated in the couples match.1 However, NRMP reports only limited data regarding the couples match, and it is not specialty specific.

We aimed to determine the characteristics of matched vs nonmatched dermatology applicants. Secondarily, we aimed to determine any differences among demographics regarding matching rates, academic performance, and research publications. We also aimed to characterize the strategy and outcomes of applicants that couples matched.

Materials and Methods

The Mayo Clinic institutional review board deemed this study exempt. All applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residency in Scottsdale, Arizona, during the 2018-2019 cycle were emailed an initial survey (N=475) before Match Day that obtained demographic information, geographic information, gap-year information, USMLE Step 1 score, publications, medical school grades, number of away rotations, and number of interviews. A follow-up survey gathering match data and couples matching data was sent to the applicants who completed the first survey on Match Day. The survey was repeated for the 2019-2020 cycle. In the second survey, Step 2 CK data were obtained. The survey was sent to 629 applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residencies in Arizona, Minnesota, and Florida to include a broader group of applicants. For publications, applicants were asked to count only published or accepted manuscripts, not abstracts, posters, conference presentations, or submitted manuscripts. Applicants who did not respond to the second survey (match data) were not included in that part of the analysis. One survey was excluded because of implausible answers (eg, scores outside of range for USMLE Step scores).

Statistical Analysis—For statistical analyses, the applicants from both applications cycles were combined. Descriptive statistics were reported in the form of mean, median, or counts (percentages), as applicable. Means were compared using 2-sided t tests. Group comparisons were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using the BlueSky Statistics version 6.30. P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

In 2019, a total of 149 applicants completed the initial survey (31.4% response rate), and 112 completed the follow-up survey (75.2% response rate). In 2020, a total of 142 applicants completed the initial survey (22.6% response rate), and 124 completed the follow-up survey (87.3% response rate). Combining the 2 years, after removing 1 survey with implausible answers, there were 290 respondents from the initial survey and 235 from the follow-up survey. The median (SD) age for the total applicants over both years was 27 (3.0) years, and 180 applicants were female (61.9%).

USMLE Scores—The median USMLE Step 1 score was 250, and scores ranged from 196 to 271. The median USMLE Step 2 CK score was 257, and scores ranged from 213 to 281. Higher USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores and more interviews were associated with higher match rates (Table 1). In addition, students with a dermatology program at their medical school were more likely to match than those without a home dermatology program.

Gender Differences—There were 180 females and 110 males who completed the surveys. Males and females had similar match rates (85.2% vs 89.0%; P=.39)(Table 2).

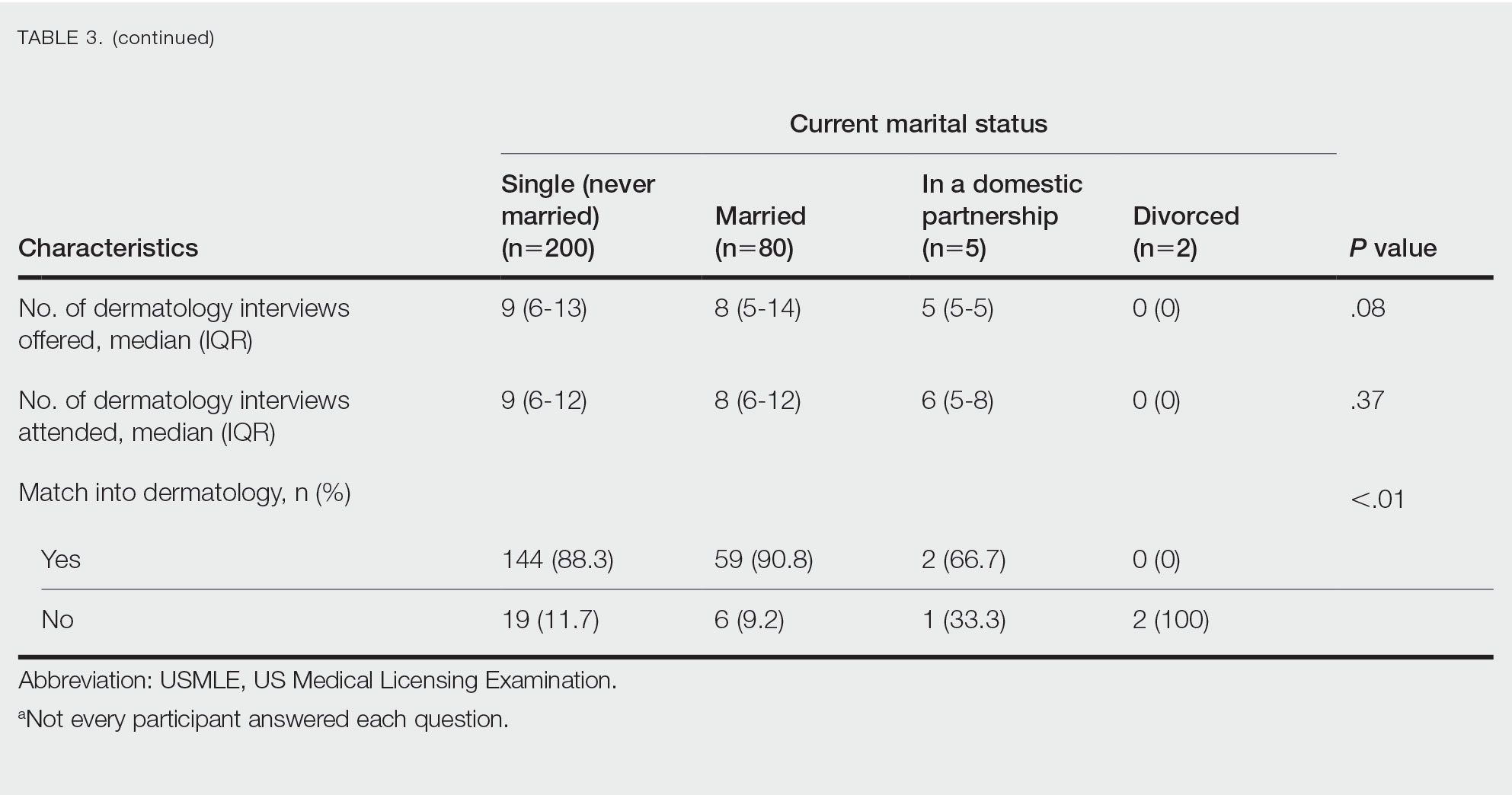

Family Life—In comparing marital status, applicants who were divorced had a higher median age (38.5 years) compared with applicants who were single, married, or in a domestic partnership (all 27 years; P<.01). Differences are outlined in Table 3.

On average, applicants with children (n=27 [15 male, 12 female]; P=.13) were 3 years older than those without (30.5 vs 27; P<.01) and were more likely to be married (88.9% vs 21.5%; P<.01). Applicants with children had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 241 compared to 251 for those without children (P=.02) and a mean USMLE Step 2 CK score of 246 compared to 258 for those without children (P<.01). Applicants with children had similar debt, number of publications, number of honored rotations, and match rates compared to applicants without children (Figure).

Couples Match—Seventeen individuals in our survey participated in the couples match (7.8%), and all 17 (100%) matched into dermatology. The mean age was 26.7 years, 12 applicants were female, 2 applicants were married, and 1 applicant had children. The mean number of interviews offered was 13.6, and the mean number of interviews attended was 11.3. This was higher than participants who were not couples matching (13.6 vs 9.8 [P=.02] and 11.3 vs 8.9 [P=.04], respectively). Applicants and their partners applied to programs and received interviews in a mean of 10 cities. Sixteen applicants reported that they contacted programs where their partner had interview offers. All participants’ rank lists included programs located in different cities than their partners’ ranked programs, and all but 1 participant ranked programs located in a different state than their partners’ ranked programs. Fifteen participants had options in their rank list for the applicant not to match, even if the partner would match. Similarly, 12 had the option for the applicant to match, even if the partner would not match. Fourteen (82.4%) matched at the same institution as their significant other. Three (17.6%) applicants matched to a program in a different state than the partner’s matched program. Two (11.8%) participants felt their relationship with their partner suffered because of the match, and 1 (5.9%) applicant was undetermined. One applicant described their relationship suffering from “unnecessary tension and anxiety” and noted “difficult conversations” about potentially matching into dermatology in a different location from their partner that could have been “devastating and not something [he or she] should have to choose.”

Comment

Factors for Matching in Dermatology—In our survey, we found the statistically significant factors of matching into dermatology included high USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores (P<.01), having a home dermatology program (P=.04), and attending a higher number of dermatology interviews (P<.01). These data are similar to NRMP results1; however, the higher likelihood of matching if the medical school has a home dermatology program has not been reported. This finding could be due to multiple factors such as students have less access to academic dermatologists for research projects, letters of recommendations, mentorship, and clinical rotations.

Gender and having children were factors that had no correlation with the match rate. There was a statistical difference of matching based on marital status (P<.01), but this is likely due to the low number of applicants in the divorced category. There were differences among demographics with USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores, which is a known factor in matching.1,2 Applicants with children had lower USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores compared to applicants without children. Females also had lower median USMLE Step 1 scores compared to males. This finding may serve as a reminder to programs when comparing USMLE Step examination scores that demographic factors may play a role. The race and ethnicity of applicants likely play a role. It has been reported that underrepresented minorities had lower match rates than White and Asian applicants in dermatology.6 There have been several published articles discussing the lack of diversity in dermatology, with a call to action.7-9

Factors for Couples Matching—The number of applicants participating in the couples match continues to increase yearly. The NMRP does publish data regarding “successful” couples matching but does not specify how many couples match together. There also is little published regarding advice for participation in the couples match. Although we had a limited number of couples that participated in the match, it is interesting to note they had similar strategies, including contacting programs at institutions that had offered interviews to their partners. This strategy may be effective, as dermatology programs offer interviews relatively late compared with other specialties.5 Additionally, this strategy may increase the number of interviews offered and received, as evidenced by the higher number of interviews offered compared with those who were not couples matching. Additionally, this survey highlights the sacrifice often needed by couples in the couples match as revealed by the inclusion of rank-list options in which the couples reside long distance or in which 1 partner does not match. This information may be helpful to applicants who are planning a strategy for the couples match in dermatology. Although this study does not encompass all dermatology applicants in the 2019-2020 cycle, we do believe it may be representative. The USMLE Step 1 scores in this study were similar to the published NRMP data.1,10 According to NRMP data from the 2019-2020 cycle, the mean USMLE Step 1 score was 248 for matched applicants and 239 for unmatched.1 The NRMP reported the mean USMLE Step 2 CK score for matched was 256 and 248 for unmatched, which also is similar to our data. The NRMP reported the mean number of programs ranked was 9.9 for matched and 4.5 for unmatched applicants.1 Again, our data were similar for number of dermatology interviews attended.

Limitations—There are limitations to this study. The main limitation is that the survey is from a single institution and had a limited number of respondents. Given the nature of the study, the accuracy of the data is dependent on the applicants’ honesty in self-reporting academic performance and other variables. There also may be a selection bias given the low response rate. The subanalyses—children and couples matching—were underpowered with the limited number of participants. Further studies that include multiple residency programs and multiple years could be helpful to provide more power and less risk of bias. We did not gather information such as the Medical Student Performance Evaluation letter, letters of recommendation, or personal statements, which do play an important role in the assessment of an applicant. However, because the applicants completed these surveys, and given these are largely blinded to applicants, we did not feel the applicants could accurately respond to those aspects of the application.

Conclusion

Our survey finds that factors associated with matching included a higher USMLE Step 1 score, having a home dermatology program, and a higher number of interviews offered and attended. Some demographics had varying USMLE Step 1 scores but similar match rates.

Dermatology residency continues to be one of the most competitive specialties, with a match rate of 84.7% for US allopathic seniors in the 2019-2020 academic year.1 In the 2019-2020 cycle, dermatology applicants were tied with plastic surgery for the highest median US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score compared with other specialties, which suggests that the top medical students are applying, yet only approximately 5 of 6 students are matching.

Factors that have been cited with successful dermatology matching include USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) scores,2 research accomplishments,3 letters of recommendation,4 medical school performance, personal statement, grades in required clerkships, and volunteer/extracurricular experiences, among others.5

The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) publishes data each year regarding different academic factors—USMLE scores; number of abstracts, presentations, and papers; work, volunteer, and research experiences—and compares the mean between matched and nonmatched applicants.1 However, the USMLE does not report any demographic information of the applicants and the implication it has for matching. Additionally, the number of couples participating in the couples match continues to increase each year. In the 2019-2020 cycle, 1224 couples participated in the couples match.1 However, NRMP reports only limited data regarding the couples match, and it is not specialty specific.

We aimed to determine the characteristics of matched vs nonmatched dermatology applicants. Secondarily, we aimed to determine any differences among demographics regarding matching rates, academic performance, and research publications. We also aimed to characterize the strategy and outcomes of applicants that couples matched.

Materials and Methods

The Mayo Clinic institutional review board deemed this study exempt. All applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residency in Scottsdale, Arizona, during the 2018-2019 cycle were emailed an initial survey (N=475) before Match Day that obtained demographic information, geographic information, gap-year information, USMLE Step 1 score, publications, medical school grades, number of away rotations, and number of interviews. A follow-up survey gathering match data and couples matching data was sent to the applicants who completed the first survey on Match Day. The survey was repeated for the 2019-2020 cycle. In the second survey, Step 2 CK data were obtained. The survey was sent to 629 applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residencies in Arizona, Minnesota, and Florida to include a broader group of applicants. For publications, applicants were asked to count only published or accepted manuscripts, not abstracts, posters, conference presentations, or submitted manuscripts. Applicants who did not respond to the second survey (match data) were not included in that part of the analysis. One survey was excluded because of implausible answers (eg, scores outside of range for USMLE Step scores).

Statistical Analysis—For statistical analyses, the applicants from both applications cycles were combined. Descriptive statistics were reported in the form of mean, median, or counts (percentages), as applicable. Means were compared using 2-sided t tests. Group comparisons were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using the BlueSky Statistics version 6.30. P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

In 2019, a total of 149 applicants completed the initial survey (31.4% response rate), and 112 completed the follow-up survey (75.2% response rate). In 2020, a total of 142 applicants completed the initial survey (22.6% response rate), and 124 completed the follow-up survey (87.3% response rate). Combining the 2 years, after removing 1 survey with implausible answers, there were 290 respondents from the initial survey and 235 from the follow-up survey. The median (SD) age for the total applicants over both years was 27 (3.0) years, and 180 applicants were female (61.9%).

USMLE Scores—The median USMLE Step 1 score was 250, and scores ranged from 196 to 271. The median USMLE Step 2 CK score was 257, and scores ranged from 213 to 281. Higher USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores and more interviews were associated with higher match rates (Table 1). In addition, students with a dermatology program at their medical school were more likely to match than those without a home dermatology program.

Gender Differences—There were 180 females and 110 males who completed the surveys. Males and females had similar match rates (85.2% vs 89.0%; P=.39)(Table 2).

Family Life—In comparing marital status, applicants who were divorced had a higher median age (38.5 years) compared with applicants who were single, married, or in a domestic partnership (all 27 years; P<.01). Differences are outlined in Table 3.

On average, applicants with children (n=27 [15 male, 12 female]; P=.13) were 3 years older than those without (30.5 vs 27; P<.01) and were more likely to be married (88.9% vs 21.5%; P<.01). Applicants with children had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 241 compared to 251 for those without children (P=.02) and a mean USMLE Step 2 CK score of 246 compared to 258 for those without children (P<.01). Applicants with children had similar debt, number of publications, number of honored rotations, and match rates compared to applicants without children (Figure).

Couples Match—Seventeen individuals in our survey participated in the couples match (7.8%), and all 17 (100%) matched into dermatology. The mean age was 26.7 years, 12 applicants were female, 2 applicants were married, and 1 applicant had children. The mean number of interviews offered was 13.6, and the mean number of interviews attended was 11.3. This was higher than participants who were not couples matching (13.6 vs 9.8 [P=.02] and 11.3 vs 8.9 [P=.04], respectively). Applicants and their partners applied to programs and received interviews in a mean of 10 cities. Sixteen applicants reported that they contacted programs where their partner had interview offers. All participants’ rank lists included programs located in different cities than their partners’ ranked programs, and all but 1 participant ranked programs located in a different state than their partners’ ranked programs. Fifteen participants had options in their rank list for the applicant not to match, even if the partner would match. Similarly, 12 had the option for the applicant to match, even if the partner would not match. Fourteen (82.4%) matched at the same institution as their significant other. Three (17.6%) applicants matched to a program in a different state than the partner’s matched program. Two (11.8%) participants felt their relationship with their partner suffered because of the match, and 1 (5.9%) applicant was undetermined. One applicant described their relationship suffering from “unnecessary tension and anxiety” and noted “difficult conversations” about potentially matching into dermatology in a different location from their partner that could have been “devastating and not something [he or she] should have to choose.”

Comment

Factors for Matching in Dermatology—In our survey, we found the statistically significant factors of matching into dermatology included high USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores (P<.01), having a home dermatology program (P=.04), and attending a higher number of dermatology interviews (P<.01). These data are similar to NRMP results1; however, the higher likelihood of matching if the medical school has a home dermatology program has not been reported. This finding could be due to multiple factors such as students have less access to academic dermatologists for research projects, letters of recommendations, mentorship, and clinical rotations.

Gender and having children were factors that had no correlation with the match rate. There was a statistical difference of matching based on marital status (P<.01), but this is likely due to the low number of applicants in the divorced category. There were differences among demographics with USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores, which is a known factor in matching.1,2 Applicants with children had lower USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores compared to applicants without children. Females also had lower median USMLE Step 1 scores compared to males. This finding may serve as a reminder to programs when comparing USMLE Step examination scores that demographic factors may play a role. The race and ethnicity of applicants likely play a role. It has been reported that underrepresented minorities had lower match rates than White and Asian applicants in dermatology.6 There have been several published articles discussing the lack of diversity in dermatology, with a call to action.7-9

Factors for Couples Matching—The number of applicants participating in the couples match continues to increase yearly. The NMRP does publish data regarding “successful” couples matching but does not specify how many couples match together. There also is little published regarding advice for participation in the couples match. Although we had a limited number of couples that participated in the match, it is interesting to note they had similar strategies, including contacting programs at institutions that had offered interviews to their partners. This strategy may be effective, as dermatology programs offer interviews relatively late compared with other specialties.5 Additionally, this strategy may increase the number of interviews offered and received, as evidenced by the higher number of interviews offered compared with those who were not couples matching. Additionally, this survey highlights the sacrifice often needed by couples in the couples match as revealed by the inclusion of rank-list options in which the couples reside long distance or in which 1 partner does not match. This information may be helpful to applicants who are planning a strategy for the couples match in dermatology. Although this study does not encompass all dermatology applicants in the 2019-2020 cycle, we do believe it may be representative. The USMLE Step 1 scores in this study were similar to the published NRMP data.1,10 According to NRMP data from the 2019-2020 cycle, the mean USMLE Step 1 score was 248 for matched applicants and 239 for unmatched.1 The NRMP reported the mean USMLE Step 2 CK score for matched was 256 and 248 for unmatched, which also is similar to our data. The NRMP reported the mean number of programs ranked was 9.9 for matched and 4.5 for unmatched applicants.1 Again, our data were similar for number of dermatology interviews attended.

Limitations—There are limitations to this study. The main limitation is that the survey is from a single institution and had a limited number of respondents. Given the nature of the study, the accuracy of the data is dependent on the applicants’ honesty in self-reporting academic performance and other variables. There also may be a selection bias given the low response rate. The subanalyses—children and couples matching—were underpowered with the limited number of participants. Further studies that include multiple residency programs and multiple years could be helpful to provide more power and less risk of bias. We did not gather information such as the Medical Student Performance Evaluation letter, letters of recommendation, or personal statements, which do play an important role in the assessment of an applicant. However, because the applicants completed these surveys, and given these are largely blinded to applicants, we did not feel the applicants could accurately respond to those aspects of the application.

Conclusion

Our survey finds that factors associated with matching included a higher USMLE Step 1 score, having a home dermatology program, and a higher number of interviews offered and attended. Some demographics had varying USMLE Step 1 scores but similar match rates.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2020. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MM_Results_and-Data_2020-1.pdf

- Gauer JL, Jackson JB. The association of USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores with residency match specialty and location. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1358579.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Wang RF, Zhang M, Kaffenberger JA. Does the dermatology standardized letter of recommendation alter applicants’ chances of matching into residency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:e139-e140.

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants-turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. Characteristics of U.S. allopathic seniors who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2018 main residency match. 2nd ed. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018_Seniors-1.pdf

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2020. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MM_Results_and-Data_2020-1.pdf

- Gauer JL, Jackson JB. The association of USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores with residency match specialty and location. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1358579.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Wang RF, Zhang M, Kaffenberger JA. Does the dermatology standardized letter of recommendation alter applicants’ chances of matching into residency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:e139-e140.

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants-turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. Characteristics of U.S. allopathic seniors who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2018 main residency match. 2nd ed. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018_Seniors-1.pdf

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatology residency continues to be one of the most competitive specialties, with a match rate of 84.7% in 2019.

- A high US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score and having a home dermatology program and a greater number of interviews may lead to higher likeliness of matching in dermatology.

- Most applicants (82.4%) applied to programs their partner had interviews at, suggesting this may be a helpful strategy.

Insights From the 2020-2021 Dermatology Residency Match

To the Editor:

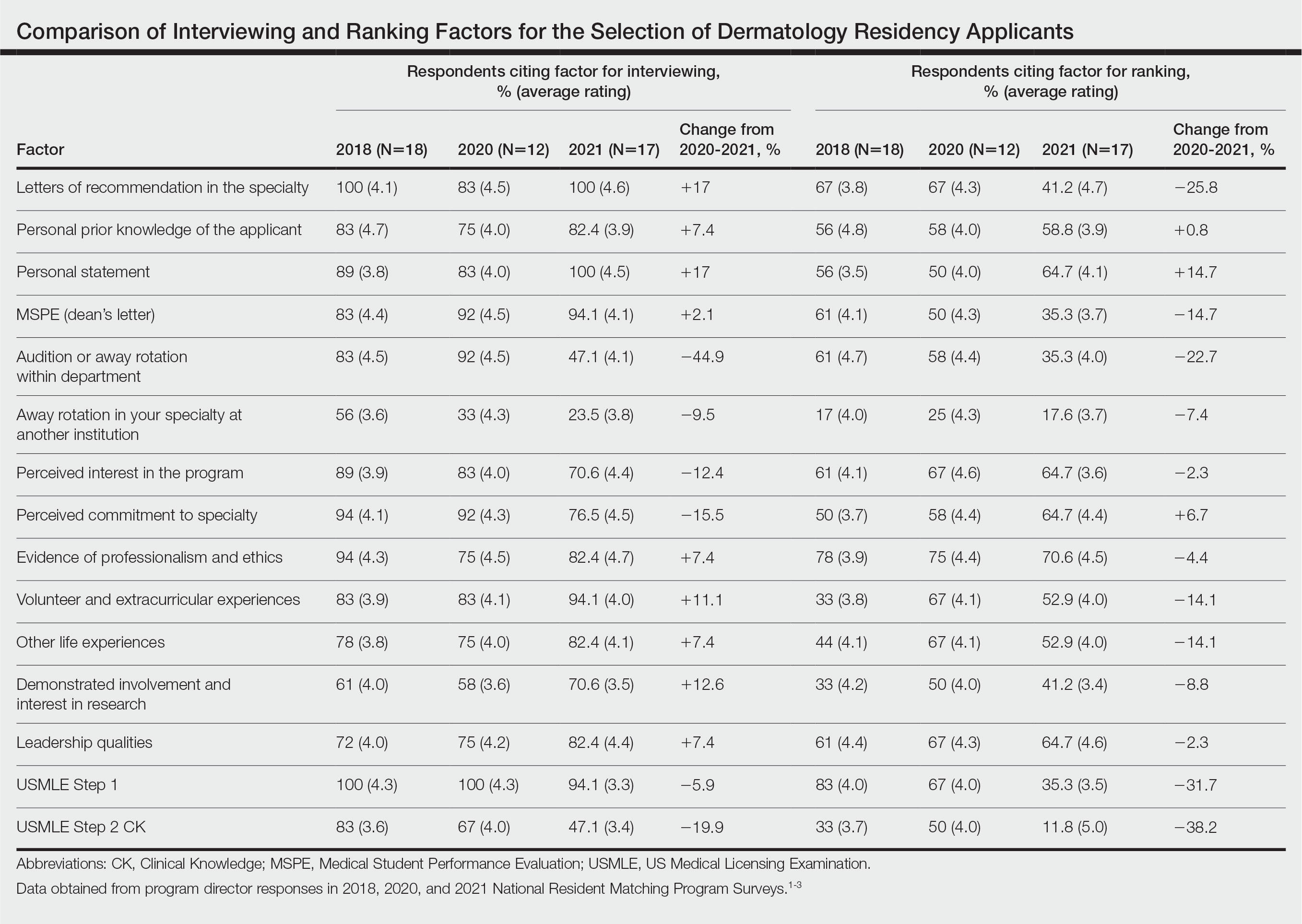

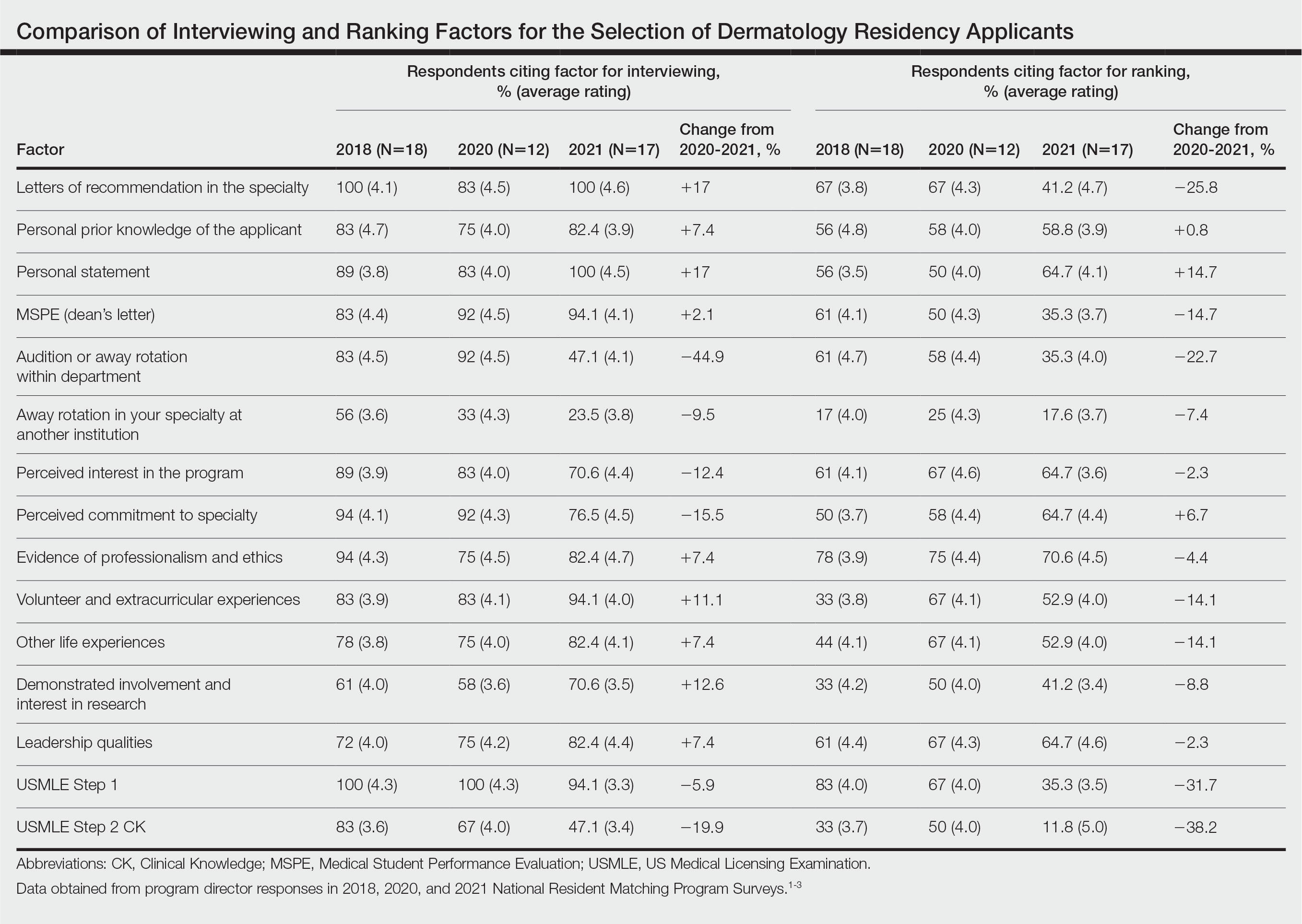

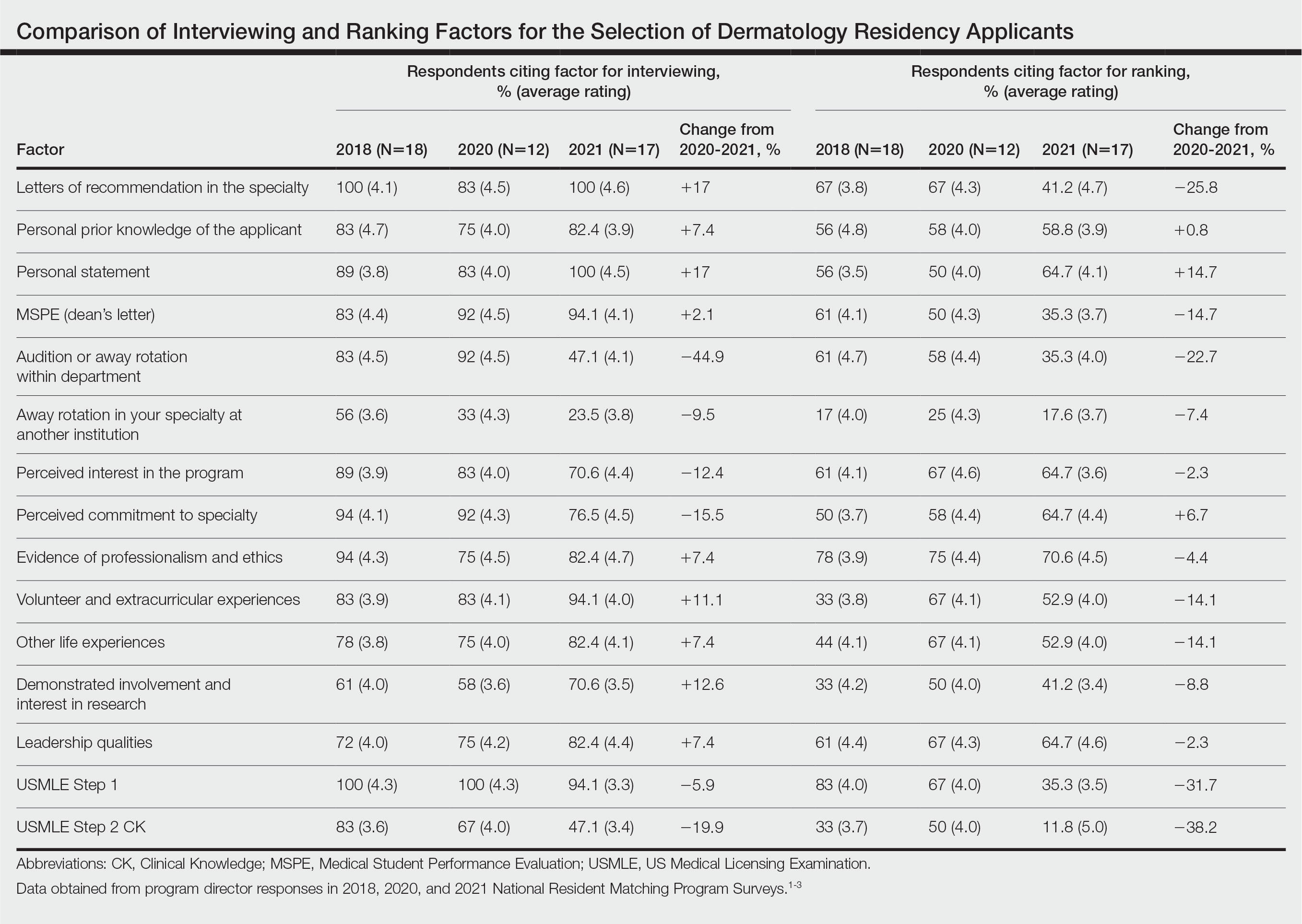

Data from the program director survey of the National Resident Matching Program offer key insights into the 2021 dermatology application process.1,2 Examination of data from the 2020 (N=12) and 2021 (N=17) program director survey regarding interviewing applicants revealed that specialty-specific letters of recommendation (LORs), personal prior knowledge of an applicant, and personal statement increased in importance by 17%, 7.4%, and 17%, respectively, whereas away rotations within the department decreased in importance by 44.9% (Table).1,2 Interestingly, for ranking applicants, programs decreased their emphasis on specialty-specific LORs by 25.8% and away rotations within the department by 22.7% and increased emphasis on personal statements by 14.7% and personal prior knowledge of an applicant by 0.8% from 2020 to 2021 (Table).1,2 These findings align with the prior recommendation to limit away rotations; data are contradictory—when comparing factors for interviewing as compared to ranking applicants—for specialty-specific LORs.

We further compared data from the otolaryngology cycle, which implemented preference signaling by which an applicant can signal their interest in a particular residency program in the 2021 Match, to data from dermatology with no preference signaling. A 90% probability of matching is estimated to require approximately 8 or 9 interviews for dermatology or 12 interviews for otolaryngology for MD senior students in 2020.4 In prior dermatology application cycles, the most highly qualified candidates constituted 7% to 21% of all applicants but were estimated to receive half of all interviews, causing a maldistribution of interviews.5,6

For the 2021 otolaryngology match, the Society of University Otolaryngologists implemented a novel preference signaling system that allowed candidates to show interest in programs by sending 5 preferences, or tokens.7 Recent data reports from the otolaryngology cycle demonstrated at least a 2-fold increase in the rate of receiving an interview invitation for signaled programs compared to the closest nonsignaled program if applicants were provided an additional token.7 Regarding overall applicant competitiveness (ie, dividing participants into quartiles based on their competitiveness), the highest increase in the overall rate of interview invitations (3.5 [total invitations/total applications]) was demonstrated for fourth-quartile (ie, “lowest quartile”) applicants compared with the increase in the overall rate of interview invitations seen in other quartiles (first quartile, an increase of 2.3; second quartile, an increase of 2.6; and third quartile, an increase of 2.4).7 We look forward to seeing the impact of preference signaling on the results of the 2022 dermatology cycle.

Despite changes in the interviewing process to accommodate COVID-19 pandemic safety recommendations, the overall dermatology postgraduate year (PGY) 2 fill rate remained unchanged from 2018 (98.6%) to 2021 (98.7%). Zero PGY-1 positions and 5 PGY-2 positions were unfilled in the 2021 Main Residency Match compared to 1 unfilled PGY-1 position and 4 unfilled PGY-2 positions in 2018.8 The coordinated interview invitation release, holistic review of applications, increased number of rankings, and virtual interviews might have helped offset potential obstacles imparted by inability to complete away rotations, inability to obtain LORs, and conducting interviews virtually.5

A limitation of our analysis is the low response rate of program directors to National Resident Matching Program surveys.

These strategies—holistic application review and coordinated interview release—may be considered in future cycles given their convenience and negligible impact on the dermatology match rate. For example, virtual interviews relieve the financial and time burdens of in-person interviews—approximately $10,000 for each US senior applicant—thus potentially allowing for a more equitable matching process.3 Inversely, in-person interviews allow participants to effectively network and form more meaningful connections while obtaining a better understanding of facilities and surrounding locales. As such, the medical community should continue to come to a consensus on the optimal format to host interviews.

- Results of the 2021 NRMP Program Director Survey. National Resident Matching Program. August 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Results of the 2020 NRMP Program Director Survey. National Resident Matching Program. August 2020. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2020-PD-Survey.pdf

- Rojek NW, Shinkai K, Fett N. Dermatology faculty and residents’ perspectives on the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:157-159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.00

- Charting Outcomes in the Match: Senior Students of U.S. MD Medical Schools. National Resident Matching Program. July 2020. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

- Thatiparthi A, Martin A, Liu J, et al. Preliminary outcomes of 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle and adverse effects of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:e263-e264. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.034

- Hammoud MM, Standiford T, Carmody JB. Potential implications of COVID-19 for the 2020-2021 residency application cycle. JAMA. 2020;324:29-30. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8911

- Interview offer rate with/without ENTSignaling. Society of University Otolaryngologists. Updated July 19, 2022. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://opdo-hns.org/mpage/signaling-updates

- Results and Data: 2021 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program. May 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/MRM-Results_and-Data_2021.pdf

To the Editor:

Data from the program director survey of the National Resident Matching Program offer key insights into the 2021 dermatology application process.1,2 Examination of data from the 2020 (N=12) and 2021 (N=17) program director survey regarding interviewing applicants revealed that specialty-specific letters of recommendation (LORs), personal prior knowledge of an applicant, and personal statement increased in importance by 17%, 7.4%, and 17%, respectively, whereas away rotations within the department decreased in importance by 44.9% (Table).1,2 Interestingly, for ranking applicants, programs decreased their emphasis on specialty-specific LORs by 25.8% and away rotations within the department by 22.7% and increased emphasis on personal statements by 14.7% and personal prior knowledge of an applicant by 0.8% from 2020 to 2021 (Table).1,2 These findings align with the prior recommendation to limit away rotations; data are contradictory—when comparing factors for interviewing as compared to ranking applicants—for specialty-specific LORs.

We further compared data from the otolaryngology cycle, which implemented preference signaling by which an applicant can signal their interest in a particular residency program in the 2021 Match, to data from dermatology with no preference signaling. A 90% probability of matching is estimated to require approximately 8 or 9 interviews for dermatology or 12 interviews for otolaryngology for MD senior students in 2020.4 In prior dermatology application cycles, the most highly qualified candidates constituted 7% to 21% of all applicants but were estimated to receive half of all interviews, causing a maldistribution of interviews.5,6

For the 2021 otolaryngology match, the Society of University Otolaryngologists implemented a novel preference signaling system that allowed candidates to show interest in programs by sending 5 preferences, or tokens.7 Recent data reports from the otolaryngology cycle demonstrated at least a 2-fold increase in the rate of receiving an interview invitation for signaled programs compared to the closest nonsignaled program if applicants were provided an additional token.7 Regarding overall applicant competitiveness (ie, dividing participants into quartiles based on their competitiveness), the highest increase in the overall rate of interview invitations (3.5 [total invitations/total applications]) was demonstrated for fourth-quartile (ie, “lowest quartile”) applicants compared with the increase in the overall rate of interview invitations seen in other quartiles (first quartile, an increase of 2.3; second quartile, an increase of 2.6; and third quartile, an increase of 2.4).7 We look forward to seeing the impact of preference signaling on the results of the 2022 dermatology cycle.

Despite changes in the interviewing process to accommodate COVID-19 pandemic safety recommendations, the overall dermatology postgraduate year (PGY) 2 fill rate remained unchanged from 2018 (98.6%) to 2021 (98.7%). Zero PGY-1 positions and 5 PGY-2 positions were unfilled in the 2021 Main Residency Match compared to 1 unfilled PGY-1 position and 4 unfilled PGY-2 positions in 2018.8 The coordinated interview invitation release, holistic review of applications, increased number of rankings, and virtual interviews might have helped offset potential obstacles imparted by inability to complete away rotations, inability to obtain LORs, and conducting interviews virtually.5

A limitation of our analysis is the low response rate of program directors to National Resident Matching Program surveys.