User login

Canned diabetes prevention and a haunted COVID castle

Lower blood sugar with sardines

If you’ve ever turned your nose up at someone eating sardines straight from the can, you could be the one missing out on a good way to boost your own health.

New research from Open University of Catalonia (Spain) has found that eating two cans of whole sardines a week can help prevent people from developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). Now you might be thinking: That’s a lot of fish, can’t I just take a supplement pill? Actually, no.

“Nutrients can play an essential role in the prevention and treatment of many different pathologies, but their effect is usually caused by the synergy that exists between them and the food that they are contained in,” study coauthor Diana Rizzolo, PhD, said in a written statement. See, we told you.

In a study of 152 patients with prediabetes, each participant was put on a specific diet to reduce their chances of developing T2D. Among the patients who were not given sardines each week, the proportion considered to be at the highest risk fell from 27% to 22% after 1 year, but for those who did get the sardines, the size of the high-risk group shrank from 37% to just 8%.

Suggesting sardines during checkups could make eating them more widely accepted, Dr. Rizzolo and associates said. Sardines are cheap, easy to find, and also have the benefits of other oily fish, like boosting insulin resistance and increasing good cholesterol.

So why not have a can with a couple of saltine crackers for lunch? Your blood sugar will thank you. Just please avoid indulging on a plane or in your office, where workers are slowly returning – no need to give them another excuse to avoid their cubicle.

Come for the torture, stay for the vaccine

Bran Castle. Home of Dracula and Vlad the Impaler (at least in pop culture’s eyes). A moody Gothic structure atop a hill. You can practically hear the ancient screams of thousands of tortured souls as you wander the grounds and its cursed halls. Naturally, it’s a major tourist destination.

Unfortunately for Romania, the pandemic has rather put a damper on tourism. The restrictions have done their damage, but here’s a quick LOTME theory: Perhaps people don’t want to be reminded of medieval tortures when we’ve got plenty of modern-day ones right now.

The management of Bran Castle has developed a new gimmick to drum up attendance – come to Bran Castle and get your COVID vaccine. Anyone can come and get jabbed with the Pfizer vaccine on all weekends in May, and when they do, they gain free admittance to the castle and the exhibit within, home to 52 medieval torture instruments. “The idea … was to show how people got jabbed 500-600 years ago in Europe,” the castle’s marketing director said.

While it may not be kind of the jabbing ole Vladdy got his name for – fully impaling people on hundreds of wooden stakes while you eat a nice dinner isn’t exactly smiled upon in today’s world – we’re sure he’d approve of this more limited but ultimately beneficial version. Jabbing people while helping them really is the dream.

Fuzzy little COVID detectors

Before we get started, we need a moment to get our deep, movie trailer announcer-type voice ready. Okay, here goes.

“In a world where an organism too tiny to see brings entire economies to a standstill and pits scientists against doofuses, who can humanity turn to for help?”

How about bees? That’s right, we said bees. But not just any bees. Specially trained bees. Specially trained Dutch bees. Bees trained to sniff out our greatest nemesis. No, we’re not talking about Ted Cruz anymore. Let it go, that was just a joke. We’re talking COVID.

We’ll let Wim van der Poel, professor of virology at Wageningen (the Netherlands) University, explain the process: “We collect normal honeybees from a beekeeper, and we put the bees in harnesses.” And you thought their tulips were pretty great – the Dutch are putting harnesses on bees! (Which is much better than our previous story of bees involving a Taiwanese patient.)

The researchers presented the bees with two types of samples: COVID infected and non–COVID infected. The infected samples came with a sugary water reward and the noninfected samples did not, so the bees quickly learned to tell the difference.

The bees, then, could cut the waiting time for test results down to seconds, and at a fraction of the cost, making them an option in countries without a lot of testing infrastructure, the research team suggested.

The plan is not without its flaws, of course, but we’re convinced. More than that, we are true bee-lievers.

A little slice of … well, not heaven

If you’ve been around for the last 2 decades, you’ve seen your share of Internet trends: Remember the ice bucket challenge? Tide pod eating? We know what you’re thinking: Sigh, what could they be doing now?

Well, people are eating old meat, and before you think about the expired ground beef you got on special from the grocery store yesterday, that’s not quite what we mean. We all know expiration dates are “suggestions,” like yield signs and yellow lights. People are eating rotten, decomposing, borderline moldy meat.

They claim that the meat tastes better. We’re not so sure, but don’t worry, because it gets weirder. Some folks, apparently, are getting high from eating this meat, experiencing a feeling of euphoria. Personally, we think that rotten fumes probably knocked these people out and made them hallucinate.

Singaporean dietitian Naras Lapsys says that eating rotten meat can possibly cause a person to go into another state of consciousness, but it’s not a good thing. We don’t think you have to be a dietitian to know that.

It has not been definitively proven that eating rotting meat makes you high, but it’s definitely proven that this is disgusting … and very dangerous.

Lower blood sugar with sardines

If you’ve ever turned your nose up at someone eating sardines straight from the can, you could be the one missing out on a good way to boost your own health.

New research from Open University of Catalonia (Spain) has found that eating two cans of whole sardines a week can help prevent people from developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). Now you might be thinking: That’s a lot of fish, can’t I just take a supplement pill? Actually, no.

“Nutrients can play an essential role in the prevention and treatment of many different pathologies, but their effect is usually caused by the synergy that exists between them and the food that they are contained in,” study coauthor Diana Rizzolo, PhD, said in a written statement. See, we told you.

In a study of 152 patients with prediabetes, each participant was put on a specific diet to reduce their chances of developing T2D. Among the patients who were not given sardines each week, the proportion considered to be at the highest risk fell from 27% to 22% after 1 year, but for those who did get the sardines, the size of the high-risk group shrank from 37% to just 8%.

Suggesting sardines during checkups could make eating them more widely accepted, Dr. Rizzolo and associates said. Sardines are cheap, easy to find, and also have the benefits of other oily fish, like boosting insulin resistance and increasing good cholesterol.

So why not have a can with a couple of saltine crackers for lunch? Your blood sugar will thank you. Just please avoid indulging on a plane or in your office, where workers are slowly returning – no need to give them another excuse to avoid their cubicle.

Come for the torture, stay for the vaccine

Bran Castle. Home of Dracula and Vlad the Impaler (at least in pop culture’s eyes). A moody Gothic structure atop a hill. You can practically hear the ancient screams of thousands of tortured souls as you wander the grounds and its cursed halls. Naturally, it’s a major tourist destination.

Unfortunately for Romania, the pandemic has rather put a damper on tourism. The restrictions have done their damage, but here’s a quick LOTME theory: Perhaps people don’t want to be reminded of medieval tortures when we’ve got plenty of modern-day ones right now.

The management of Bran Castle has developed a new gimmick to drum up attendance – come to Bran Castle and get your COVID vaccine. Anyone can come and get jabbed with the Pfizer vaccine on all weekends in May, and when they do, they gain free admittance to the castle and the exhibit within, home to 52 medieval torture instruments. “The idea … was to show how people got jabbed 500-600 years ago in Europe,” the castle’s marketing director said.

While it may not be kind of the jabbing ole Vladdy got his name for – fully impaling people on hundreds of wooden stakes while you eat a nice dinner isn’t exactly smiled upon in today’s world – we’re sure he’d approve of this more limited but ultimately beneficial version. Jabbing people while helping them really is the dream.

Fuzzy little COVID detectors

Before we get started, we need a moment to get our deep, movie trailer announcer-type voice ready. Okay, here goes.

“In a world where an organism too tiny to see brings entire economies to a standstill and pits scientists against doofuses, who can humanity turn to for help?”

How about bees? That’s right, we said bees. But not just any bees. Specially trained bees. Specially trained Dutch bees. Bees trained to sniff out our greatest nemesis. No, we’re not talking about Ted Cruz anymore. Let it go, that was just a joke. We’re talking COVID.

We’ll let Wim van der Poel, professor of virology at Wageningen (the Netherlands) University, explain the process: “We collect normal honeybees from a beekeeper, and we put the bees in harnesses.” And you thought their tulips were pretty great – the Dutch are putting harnesses on bees! (Which is much better than our previous story of bees involving a Taiwanese patient.)

The researchers presented the bees with two types of samples: COVID infected and non–COVID infected. The infected samples came with a sugary water reward and the noninfected samples did not, so the bees quickly learned to tell the difference.

The bees, then, could cut the waiting time for test results down to seconds, and at a fraction of the cost, making them an option in countries without a lot of testing infrastructure, the research team suggested.

The plan is not without its flaws, of course, but we’re convinced. More than that, we are true bee-lievers.

A little slice of … well, not heaven

If you’ve been around for the last 2 decades, you’ve seen your share of Internet trends: Remember the ice bucket challenge? Tide pod eating? We know what you’re thinking: Sigh, what could they be doing now?

Well, people are eating old meat, and before you think about the expired ground beef you got on special from the grocery store yesterday, that’s not quite what we mean. We all know expiration dates are “suggestions,” like yield signs and yellow lights. People are eating rotten, decomposing, borderline moldy meat.

They claim that the meat tastes better. We’re not so sure, but don’t worry, because it gets weirder. Some folks, apparently, are getting high from eating this meat, experiencing a feeling of euphoria. Personally, we think that rotten fumes probably knocked these people out and made them hallucinate.

Singaporean dietitian Naras Lapsys says that eating rotten meat can possibly cause a person to go into another state of consciousness, but it’s not a good thing. We don’t think you have to be a dietitian to know that.

It has not been definitively proven that eating rotting meat makes you high, but it’s definitely proven that this is disgusting … and very dangerous.

Lower blood sugar with sardines

If you’ve ever turned your nose up at someone eating sardines straight from the can, you could be the one missing out on a good way to boost your own health.

New research from Open University of Catalonia (Spain) has found that eating two cans of whole sardines a week can help prevent people from developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). Now you might be thinking: That’s a lot of fish, can’t I just take a supplement pill? Actually, no.

“Nutrients can play an essential role in the prevention and treatment of many different pathologies, but their effect is usually caused by the synergy that exists between them and the food that they are contained in,” study coauthor Diana Rizzolo, PhD, said in a written statement. See, we told you.

In a study of 152 patients with prediabetes, each participant was put on a specific diet to reduce their chances of developing T2D. Among the patients who were not given sardines each week, the proportion considered to be at the highest risk fell from 27% to 22% after 1 year, but for those who did get the sardines, the size of the high-risk group shrank from 37% to just 8%.

Suggesting sardines during checkups could make eating them more widely accepted, Dr. Rizzolo and associates said. Sardines are cheap, easy to find, and also have the benefits of other oily fish, like boosting insulin resistance and increasing good cholesterol.

So why not have a can with a couple of saltine crackers for lunch? Your blood sugar will thank you. Just please avoid indulging on a plane or in your office, where workers are slowly returning – no need to give them another excuse to avoid their cubicle.

Come for the torture, stay for the vaccine

Bran Castle. Home of Dracula and Vlad the Impaler (at least in pop culture’s eyes). A moody Gothic structure atop a hill. You can practically hear the ancient screams of thousands of tortured souls as you wander the grounds and its cursed halls. Naturally, it’s a major tourist destination.

Unfortunately for Romania, the pandemic has rather put a damper on tourism. The restrictions have done their damage, but here’s a quick LOTME theory: Perhaps people don’t want to be reminded of medieval tortures when we’ve got plenty of modern-day ones right now.

The management of Bran Castle has developed a new gimmick to drum up attendance – come to Bran Castle and get your COVID vaccine. Anyone can come and get jabbed with the Pfizer vaccine on all weekends in May, and when they do, they gain free admittance to the castle and the exhibit within, home to 52 medieval torture instruments. “The idea … was to show how people got jabbed 500-600 years ago in Europe,” the castle’s marketing director said.

While it may not be kind of the jabbing ole Vladdy got his name for – fully impaling people on hundreds of wooden stakes while you eat a nice dinner isn’t exactly smiled upon in today’s world – we’re sure he’d approve of this more limited but ultimately beneficial version. Jabbing people while helping them really is the dream.

Fuzzy little COVID detectors

Before we get started, we need a moment to get our deep, movie trailer announcer-type voice ready. Okay, here goes.

“In a world where an organism too tiny to see brings entire economies to a standstill and pits scientists against doofuses, who can humanity turn to for help?”

How about bees? That’s right, we said bees. But not just any bees. Specially trained bees. Specially trained Dutch bees. Bees trained to sniff out our greatest nemesis. No, we’re not talking about Ted Cruz anymore. Let it go, that was just a joke. We’re talking COVID.

We’ll let Wim van der Poel, professor of virology at Wageningen (the Netherlands) University, explain the process: “We collect normal honeybees from a beekeeper, and we put the bees in harnesses.” And you thought their tulips were pretty great – the Dutch are putting harnesses on bees! (Which is much better than our previous story of bees involving a Taiwanese patient.)

The researchers presented the bees with two types of samples: COVID infected and non–COVID infected. The infected samples came with a sugary water reward and the noninfected samples did not, so the bees quickly learned to tell the difference.

The bees, then, could cut the waiting time for test results down to seconds, and at a fraction of the cost, making them an option in countries without a lot of testing infrastructure, the research team suggested.

The plan is not without its flaws, of course, but we’re convinced. More than that, we are true bee-lievers.

A little slice of … well, not heaven

If you’ve been around for the last 2 decades, you’ve seen your share of Internet trends: Remember the ice bucket challenge? Tide pod eating? We know what you’re thinking: Sigh, what could they be doing now?

Well, people are eating old meat, and before you think about the expired ground beef you got on special from the grocery store yesterday, that’s not quite what we mean. We all know expiration dates are “suggestions,” like yield signs and yellow lights. People are eating rotten, decomposing, borderline moldy meat.

They claim that the meat tastes better. We’re not so sure, but don’t worry, because it gets weirder. Some folks, apparently, are getting high from eating this meat, experiencing a feeling of euphoria. Personally, we think that rotten fumes probably knocked these people out and made them hallucinate.

Singaporean dietitian Naras Lapsys says that eating rotten meat can possibly cause a person to go into another state of consciousness, but it’s not a good thing. We don’t think you have to be a dietitian to know that.

It has not been definitively proven that eating rotting meat makes you high, but it’s definitely proven that this is disgusting … and very dangerous.

How to write a manuscript for publication

Writing should be fun! While some may view writing as painful (i.e., something you rather put off until all your household work, taxes, and even changing the litter boxes are done), writing can and will become more enjoyable the more you do it. Over the years that I have been writing with students, residents, and faculty, I have found that writing the discussion section of a manuscript remains the most daunting aspect of writing a paper and the No. 1 reason people put off writing. Thus, I have developed a strategy that distills this process into a very simple task. When followed, manuscript writing won’t seem so intimidating.

I like to consider the writing process in three phases: preparing to write, writing, and then revising. Let’s address each one of these.

Preparing to write

In preparing to write, it is important to know what audience you want to reach when selecting a journal. I recommend that you peruse the table of contents of the journals you have in mind to determine if that journal is publishing papers similar to yours. You also may want to consider the impact factor of the journal, as the journals you publish in can have an effect on your promotion and tenure process. Once you have decided upon a journal, retrieve the Instructions for Authors (IFA). This section will contain very important information about how the journal would like for you to format the manuscript. Follow these instructions!

If you do not follow these instructions, the journal may reject your manuscript without ever sending it out for review (that is, the managing editor will reject it). Think of it this way, if an editor takes the time to develop the IFA, you’d better believe that the requirements are important to that editor.

Once you have decided upon the journal and read the IFA, it is time to make an OUTLINE. Yes – I said it – an outline. So often we skip this simple task that we were taught in grade school. For a manuscript, the outline I start with includes the figures and/or tables. Your figures and/or tables should tell the story. If they don’t tell a cohesive story, something is wrong. I like to draw out story board on 8.5” x 11” plain paper. Each sheet of paper represents one figure (or table), and I literally draw out each panel. Then I spread the pieces of paper out on a desk to see if they tell the story I want. Once the story is determined, the writing begins.

Writing

The main structure of a manuscript is simple: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. The introduction section should tell the reader why you did the study. The methods section should tell the reader how you did the study. The results section should tell the reader what you found when you did the study. The discussion section should tell the reader what it all means. The introduction should spark the readers interest and provide them with enough information to understand why you conducted the study. It should consist of two to three paragraphs. The first paragraph should state the problem. The second paragraph should state what is known and unknown about the problem. The third paragraph should logically follow with your aim and hypothesis. All manuscripts can and should have a hypothesis.

The methods section should be presented in a straightforward and logical manner and include enough information for others to reproduce the experiments. The information should be presented with subheadings for each different section. For example, a clinical manuscript may have the follow subheadings: study design, study population, primary outcome, secondary outcomes, and statistical analysis.

The results section should also be presented in a logical manner, with subheadings that make sense. Be sure to refer to the IFA on the type of subheadings to use (descriptive versus simple, etc.) and remember to tell a story. The story can be told with data of most to least important, in chronological order, in vitro to in vivo, etc. The main point is to tell a good story that the reader will want to read! Be sure to cite your figures and table, but don’t duplicate the information in the figures and tables.

A nice trick is to present the data in each paragraph, and end with a sentence summarizing the results. Remember, data are the facts obtained from the experiments while results are statements that interpret the data.

The discussion section should be seen as a straightforward section to write instead of an intimidating discourse. The discussion section is where you tell the reader what the data might mean, how else the data could be interpreted, if other studies had similar or dissimilar results, the limitations of the study, and what should be done next. I propose that all discussion sections can be written in five paragraphs.

Paragraph 1 should summarize the findings with respect to the hypothesis. Paragraphs 2 and 3 should compare and contrast your data with published literature. Paragraph 4 should address limitations of the study. Paragraph 5 should conclude what it all means and what should happen next. If you start by outlining these five paragraphs, the discussion section becomes simple to write.

Revising

The most important aspect of writing a manuscript is revising. The importance of this is often overlooked. We all make mistakes in writing. The more you reread and revise your own work, the better it gets. Aim for writing simple sentences that are easy for your reader to read. Choose words carefully and precisely. Write well-designed sentences and structured paragraphs. The Internet has many short online tutorials to remind one how to do this. Use abbreviations sparingly and avoid wordiness. Avoid writing flaws, especially with the subject and verb. For example, “Controls were performed” should read “Control experiments were performed.”

In summary, writing should be an enjoyable process in which one can communicate exciting ideas to others. In this short article, I have presented a few tips and tricks on how to write and revise a manuscript. For a more in-depth resource, I refer the reader to “How to write a paper,” published in 2013 (ANZ J Surg. Jan;83[1-2]:90-2).

Dr. Kibbe is the Zack D. Owens Professor and Chair, department of surgery, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Writing should be fun! While some may view writing as painful (i.e., something you rather put off until all your household work, taxes, and even changing the litter boxes are done), writing can and will become more enjoyable the more you do it. Over the years that I have been writing with students, residents, and faculty, I have found that writing the discussion section of a manuscript remains the most daunting aspect of writing a paper and the No. 1 reason people put off writing. Thus, I have developed a strategy that distills this process into a very simple task. When followed, manuscript writing won’t seem so intimidating.

I like to consider the writing process in three phases: preparing to write, writing, and then revising. Let’s address each one of these.

Preparing to write

In preparing to write, it is important to know what audience you want to reach when selecting a journal. I recommend that you peruse the table of contents of the journals you have in mind to determine if that journal is publishing papers similar to yours. You also may want to consider the impact factor of the journal, as the journals you publish in can have an effect on your promotion and tenure process. Once you have decided upon a journal, retrieve the Instructions for Authors (IFA). This section will contain very important information about how the journal would like for you to format the manuscript. Follow these instructions!

If you do not follow these instructions, the journal may reject your manuscript without ever sending it out for review (that is, the managing editor will reject it). Think of it this way, if an editor takes the time to develop the IFA, you’d better believe that the requirements are important to that editor.

Once you have decided upon the journal and read the IFA, it is time to make an OUTLINE. Yes – I said it – an outline. So often we skip this simple task that we were taught in grade school. For a manuscript, the outline I start with includes the figures and/or tables. Your figures and/or tables should tell the story. If they don’t tell a cohesive story, something is wrong. I like to draw out story board on 8.5” x 11” plain paper. Each sheet of paper represents one figure (or table), and I literally draw out each panel. Then I spread the pieces of paper out on a desk to see if they tell the story I want. Once the story is determined, the writing begins.

Writing

The main structure of a manuscript is simple: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. The introduction section should tell the reader why you did the study. The methods section should tell the reader how you did the study. The results section should tell the reader what you found when you did the study. The discussion section should tell the reader what it all means. The introduction should spark the readers interest and provide them with enough information to understand why you conducted the study. It should consist of two to three paragraphs. The first paragraph should state the problem. The second paragraph should state what is known and unknown about the problem. The third paragraph should logically follow with your aim and hypothesis. All manuscripts can and should have a hypothesis.

The methods section should be presented in a straightforward and logical manner and include enough information for others to reproduce the experiments. The information should be presented with subheadings for each different section. For example, a clinical manuscript may have the follow subheadings: study design, study population, primary outcome, secondary outcomes, and statistical analysis.

The results section should also be presented in a logical manner, with subheadings that make sense. Be sure to refer to the IFA on the type of subheadings to use (descriptive versus simple, etc.) and remember to tell a story. The story can be told with data of most to least important, in chronological order, in vitro to in vivo, etc. The main point is to tell a good story that the reader will want to read! Be sure to cite your figures and table, but don’t duplicate the information in the figures and tables.

A nice trick is to present the data in each paragraph, and end with a sentence summarizing the results. Remember, data are the facts obtained from the experiments while results are statements that interpret the data.

The discussion section should be seen as a straightforward section to write instead of an intimidating discourse. The discussion section is where you tell the reader what the data might mean, how else the data could be interpreted, if other studies had similar or dissimilar results, the limitations of the study, and what should be done next. I propose that all discussion sections can be written in five paragraphs.

Paragraph 1 should summarize the findings with respect to the hypothesis. Paragraphs 2 and 3 should compare and contrast your data with published literature. Paragraph 4 should address limitations of the study. Paragraph 5 should conclude what it all means and what should happen next. If you start by outlining these five paragraphs, the discussion section becomes simple to write.

Revising

The most important aspect of writing a manuscript is revising. The importance of this is often overlooked. We all make mistakes in writing. The more you reread and revise your own work, the better it gets. Aim for writing simple sentences that are easy for your reader to read. Choose words carefully and precisely. Write well-designed sentences and structured paragraphs. The Internet has many short online tutorials to remind one how to do this. Use abbreviations sparingly and avoid wordiness. Avoid writing flaws, especially with the subject and verb. For example, “Controls were performed” should read “Control experiments were performed.”

In summary, writing should be an enjoyable process in which one can communicate exciting ideas to others. In this short article, I have presented a few tips and tricks on how to write and revise a manuscript. For a more in-depth resource, I refer the reader to “How to write a paper,” published in 2013 (ANZ J Surg. Jan;83[1-2]:90-2).

Dr. Kibbe is the Zack D. Owens Professor and Chair, department of surgery, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Writing should be fun! While some may view writing as painful (i.e., something you rather put off until all your household work, taxes, and even changing the litter boxes are done), writing can and will become more enjoyable the more you do it. Over the years that I have been writing with students, residents, and faculty, I have found that writing the discussion section of a manuscript remains the most daunting aspect of writing a paper and the No. 1 reason people put off writing. Thus, I have developed a strategy that distills this process into a very simple task. When followed, manuscript writing won’t seem so intimidating.

I like to consider the writing process in three phases: preparing to write, writing, and then revising. Let’s address each one of these.

Preparing to write

In preparing to write, it is important to know what audience you want to reach when selecting a journal. I recommend that you peruse the table of contents of the journals you have in mind to determine if that journal is publishing papers similar to yours. You also may want to consider the impact factor of the journal, as the journals you publish in can have an effect on your promotion and tenure process. Once you have decided upon a journal, retrieve the Instructions for Authors (IFA). This section will contain very important information about how the journal would like for you to format the manuscript. Follow these instructions!

If you do not follow these instructions, the journal may reject your manuscript without ever sending it out for review (that is, the managing editor will reject it). Think of it this way, if an editor takes the time to develop the IFA, you’d better believe that the requirements are important to that editor.

Once you have decided upon the journal and read the IFA, it is time to make an OUTLINE. Yes – I said it – an outline. So often we skip this simple task that we were taught in grade school. For a manuscript, the outline I start with includes the figures and/or tables. Your figures and/or tables should tell the story. If they don’t tell a cohesive story, something is wrong. I like to draw out story board on 8.5” x 11” plain paper. Each sheet of paper represents one figure (or table), and I literally draw out each panel. Then I spread the pieces of paper out on a desk to see if they tell the story I want. Once the story is determined, the writing begins.

Writing

The main structure of a manuscript is simple: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. The introduction section should tell the reader why you did the study. The methods section should tell the reader how you did the study. The results section should tell the reader what you found when you did the study. The discussion section should tell the reader what it all means. The introduction should spark the readers interest and provide them with enough information to understand why you conducted the study. It should consist of two to three paragraphs. The first paragraph should state the problem. The second paragraph should state what is known and unknown about the problem. The third paragraph should logically follow with your aim and hypothesis. All manuscripts can and should have a hypothesis.

The methods section should be presented in a straightforward and logical manner and include enough information for others to reproduce the experiments. The information should be presented with subheadings for each different section. For example, a clinical manuscript may have the follow subheadings: study design, study population, primary outcome, secondary outcomes, and statistical analysis.

The results section should also be presented in a logical manner, with subheadings that make sense. Be sure to refer to the IFA on the type of subheadings to use (descriptive versus simple, etc.) and remember to tell a story. The story can be told with data of most to least important, in chronological order, in vitro to in vivo, etc. The main point is to tell a good story that the reader will want to read! Be sure to cite your figures and table, but don’t duplicate the information in the figures and tables.

A nice trick is to present the data in each paragraph, and end with a sentence summarizing the results. Remember, data are the facts obtained from the experiments while results are statements that interpret the data.

The discussion section should be seen as a straightforward section to write instead of an intimidating discourse. The discussion section is where you tell the reader what the data might mean, how else the data could be interpreted, if other studies had similar or dissimilar results, the limitations of the study, and what should be done next. I propose that all discussion sections can be written in five paragraphs.

Paragraph 1 should summarize the findings with respect to the hypothesis. Paragraphs 2 and 3 should compare and contrast your data with published literature. Paragraph 4 should address limitations of the study. Paragraph 5 should conclude what it all means and what should happen next. If you start by outlining these five paragraphs, the discussion section becomes simple to write.

Revising

The most important aspect of writing a manuscript is revising. The importance of this is often overlooked. We all make mistakes in writing. The more you reread and revise your own work, the better it gets. Aim for writing simple sentences that are easy for your reader to read. Choose words carefully and precisely. Write well-designed sentences and structured paragraphs. The Internet has many short online tutorials to remind one how to do this. Use abbreviations sparingly and avoid wordiness. Avoid writing flaws, especially with the subject and verb. For example, “Controls were performed” should read “Control experiments were performed.”

In summary, writing should be an enjoyable process in which one can communicate exciting ideas to others. In this short article, I have presented a few tips and tricks on how to write and revise a manuscript. For a more in-depth resource, I refer the reader to “How to write a paper,” published in 2013 (ANZ J Surg. Jan;83[1-2]:90-2).

Dr. Kibbe is the Zack D. Owens Professor and Chair, department of surgery, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

COMMENTARY: How and why to perform research as a trainee

"Why do I need to do research if I'm going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature.

This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery.

Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies.

Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings.

Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat.

There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor; a topic; a clear, novel question; and the appropriate study design.

Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiovascular surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon. The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time.

The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor that is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals.

Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

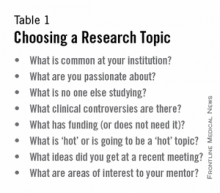

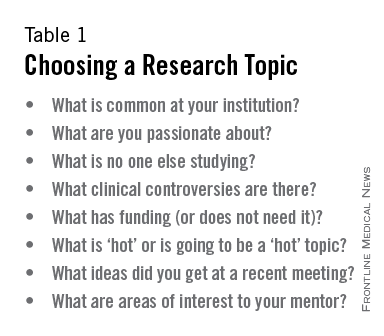

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is: "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?"

Stay away from the lure of "Let's review our experience of operation X…" or "Why don't I see how many of operation Y we've done over the past 10 years…" These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee.

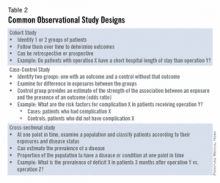

The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2).

Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

In the design of a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori end points.

Every study will have one primary end point that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you do it only once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps, there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results?

Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval. This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed-upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

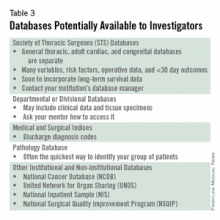

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project. Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity).

Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data exists regardless if the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward. Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct.

Next using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript. Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study.

Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product. Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing.

Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you.

Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don't know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions. Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study.

You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

"Why do I need to do research if I'm going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature.

This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery.

Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies.

Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings.

Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat.

There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor; a topic; a clear, novel question; and the appropriate study design.

Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiovascular surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon. The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time.

The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor that is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals.

Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is: "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?"

Stay away from the lure of "Let's review our experience of operation X…" or "Why don't I see how many of operation Y we've done over the past 10 years…" These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee.

The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2).

Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

In the design of a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori end points.

Every study will have one primary end point that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you do it only once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps, there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results?

Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval. This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed-upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project. Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity).

Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data exists regardless if the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward. Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct.

Next using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript. Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study.

Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product. Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing.

Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you.

Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don't know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions. Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study.

You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

"Why do I need to do research if I'm going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature.

This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery.

Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies.

Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings.

Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat.

There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor; a topic; a clear, novel question; and the appropriate study design.

Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiovascular surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon. The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time.

The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor that is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals.

Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is: "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?"

Stay away from the lure of "Let's review our experience of operation X…" or "Why don't I see how many of operation Y we've done over the past 10 years…" These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee.

The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2).

Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

In the design of a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori end points.

Every study will have one primary end point that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you do it only once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps, there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results?

Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval. This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed-upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project. Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity).

Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data exists regardless if the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward. Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct.

Next using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript. Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study.

Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product. Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing.

Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you.

Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don't know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions. Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study.

You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

Challenges in Training: Open repair in 2020

Since FDA approval of endovascular aneurysm repair in 1999, the management of abdominal aortic aneurysms has transformed. Only 5.2% of AAAs were repaired by EVAR in 2000 compared to 74% in 2010. While the volume of AAA cases has remained constant at about 45,000 cases annually, the increase in EVAR has led to a 34% drop in open AAA cases. This national decline in open AAA cases is paralleled by a 33% decline in open AAA cases completed by vascular trainees since 2001, as reported in national Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education case logs.

In conjunction with this decrease in open AAA repair volume, trainees are reporting low confidence in independently performing open aneurysm cases, with nearly 40% of 2014 graduating vascular trainees having expressed low confidence in their ability on a 3-point Likert scale (1 – not confident, 2 – somewhat confident, 3 – very confident).

Over the past decade, we have also seen a threefold increase in adjudicated cases against vascular surgeons due to complications arising from open AAA cases, along with an increase in litigation against vascular surgeons who have been in practice for fewer than 3 years.

Open AAA surgery volume will continue to decrease as branched and fenestrated technology improves, and as expanded utilization in patients with complex anatomy occurs with the next generation of endografts.

By 2020, based on prediction models, vascular trainees will complete only five open aneurysm cases during their training, This raises serious questions about how we will educate the next generation of vascular surgeons to safely and effectively manage patients who can be treated only by open repair.

Since FDA approval of endovascular aneurysm repair in 1999, the management of abdominal aortic aneurysms has transformed. Only 5.2% of AAAs were repaired by EVAR in 2000 compared to 74% in 2010. While the volume of AAA cases has remained constant at about 45,000 cases annually, the increase in EVAR has led to a 34% drop in open AAA cases. This national decline in open AAA cases is paralleled by a 33% decline in open AAA cases completed by vascular trainees since 2001, as reported in national Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education case logs.

In conjunction with this decrease in open AAA repair volume, trainees are reporting low confidence in independently performing open aneurysm cases, with nearly 40% of 2014 graduating vascular trainees having expressed low confidence in their ability on a 3-point Likert scale (1 – not confident, 2 – somewhat confident, 3 – very confident).

Over the past decade, we have also seen a threefold increase in adjudicated cases against vascular surgeons due to complications arising from open AAA cases, along with an increase in litigation against vascular surgeons who have been in practice for fewer than 3 years.

Open AAA surgery volume will continue to decrease as branched and fenestrated technology improves, and as expanded utilization in patients with complex anatomy occurs with the next generation of endografts.

By 2020, based on prediction models, vascular trainees will complete only five open aneurysm cases during their training, This raises serious questions about how we will educate the next generation of vascular surgeons to safely and effectively manage patients who can be treated only by open repair.

Since FDA approval of endovascular aneurysm repair in 1999, the management of abdominal aortic aneurysms has transformed. Only 5.2% of AAAs were repaired by EVAR in 2000 compared to 74% in 2010. While the volume of AAA cases has remained constant at about 45,000 cases annually, the increase in EVAR has led to a 34% drop in open AAA cases. This national decline in open AAA cases is paralleled by a 33% decline in open AAA cases completed by vascular trainees since 2001, as reported in national Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education case logs.

In conjunction with this decrease in open AAA repair volume, trainees are reporting low confidence in independently performing open aneurysm cases, with nearly 40% of 2014 graduating vascular trainees having expressed low confidence in their ability on a 3-point Likert scale (1 – not confident, 2 – somewhat confident, 3 – very confident).

Over the past decade, we have also seen a threefold increase in adjudicated cases against vascular surgeons due to complications arising from open AAA cases, along with an increase in litigation against vascular surgeons who have been in practice for fewer than 3 years.

Open AAA surgery volume will continue to decrease as branched and fenestrated technology improves, and as expanded utilization in patients with complex anatomy occurs with the next generation of endografts.

By 2020, based on prediction models, vascular trainees will complete only five open aneurysm cases during their training, This raises serious questions about how we will educate the next generation of vascular surgeons to safely and effectively manage patients who can be treated only by open repair.

Fear and Loathing on the Interview Trail

As we strive to provide the most advanced care possible to our patients with vascular disease, there is one area of our practice that stands out as being as archaic as cellophane wrapping of aneurysms: the process of finding a job.

Instead of an enlightening quest to find the perfect practice, many graduating vascular fellows have found it to be a tiring and laborious process. The excitement around the opportunity to finally do what we have trained so long and hard to do has been eclipsed in frustration by a disorganized and antiquated interview process.

The business side of medicine has very much been on display in the popular media with the institution of new healthcare reform legislation. No financially viable business would fly a client halfway across the country to find out if they're a 'good guy' prior to discussing a potential deal. This should not be the routine in medicine, either.

I implore vascular surgeons to utilize technology to modernize the process of expanding their practice. Replace the 'good old boy' and device rep networks with posts on the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) Job bank. Loose the recruiters and write a concise description of your current practice and what you have to offer. Replace the mandatory meet and greet first interview with a video conference via SKYPE. This will obviate the need to clear your schedule for the day and shelve the awkward interview in the operating theater.

A colleague of mine has equated interviewing for a vascular surgery job with trying to buy a used car without knowing the price. Even if it requires a non-disclosure agreement, opening the books to a prospective partner early in the interview process is vital. In addition to demonstrating integrity and building good will, it validates your case mix and volume. Without this knowledge, an applicant cannot make an informed decision to join a practice.

Most importantly, be professional. If a candidate is not what you're looking for, be straightforward and tactful. Communicate; don't string someone along in case another prospect falls through.

For those of you who are getting ready to or are still looking for your first job- do your homework. Converse with your faculty members, get in touch with the local device reps, and talk to former fellows about your job prospects. On the interview don't hesitate to pull the ancillary staff aside for their opinion of the group. One of my co-fellows did this and learned that the surgeon had not booked a case in the operating room for six months. The hospital administrators confessed that they were interviewing to replace the surgeon, not hire on a partner.

There are a multitude of resources available to arm yourself when it comes to contract negotiations. Read "The Physician's Comprehensive Guide to Negotiating" (SEAK, Inc.) by Steven Babitsky and James J. Mangraviti, Jr. I obtained a copy through interlibrary loan and read it in two days between cases. It is well worth the small time investment.

Call your institution's physician contract liaison to review a sample contract and gain access to the MGMA physician salary survey. Remember these data includes responses from vascular surgeons in both private practice and academics and may not reflect your true market value. Talk to the fellows who graduated before you to get an idea of what range of offers are out there.

Attend regional and national vascular surgery conferences to network and gain leads. The SVS young surgeon's forum at the annual meeting is a good introduction into the job search process. The most comprehensive review to date is the Mote Vascular Symposium put on by Dr. Russell H. Samson's group out of Sarasota, FL. Beg, borrow, or steal the weekend off to attend this meeting.

Our goal as graduating fellows is to not only provide exceptional care to the patients with vascular disease in the communities we join, but to modernize the practice of our partners. Whether this means an aggressive endovascular approach to aneurysmal disease or overseeing the redesign of the practice's website, by virtue of training in the information age we are well prepared.

Every page of this newspaper is geared toward making us better vascular surgeons. So please, let's start by bringing the interview process in to the 21st century.

Christopher Everett, M.D., is a Vascular Surgery Fellow, year two, at the Greenville University Hospital Medical Center, Greenville, SC.

As we strive to provide the most advanced care possible to our patients with vascular disease, there is one area of our practice that stands out as being as archaic as cellophane wrapping of aneurysms: the process of finding a job.

Instead of an enlightening quest to find the perfect practice, many graduating vascular fellows have found it to be a tiring and laborious process. The excitement around the opportunity to finally do what we have trained so long and hard to do has been eclipsed in frustration by a disorganized and antiquated interview process.

The business side of medicine has very much been on display in the popular media with the institution of new healthcare reform legislation. No financially viable business would fly a client halfway across the country to find out if they're a 'good guy' prior to discussing a potential deal. This should not be the routine in medicine, either.

I implore vascular surgeons to utilize technology to modernize the process of expanding their practice. Replace the 'good old boy' and device rep networks with posts on the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) Job bank. Loose the recruiters and write a concise description of your current practice and what you have to offer. Replace the mandatory meet and greet first interview with a video conference via SKYPE. This will obviate the need to clear your schedule for the day and shelve the awkward interview in the operating theater.

A colleague of mine has equated interviewing for a vascular surgery job with trying to buy a used car without knowing the price. Even if it requires a non-disclosure agreement, opening the books to a prospective partner early in the interview process is vital. In addition to demonstrating integrity and building good will, it validates your case mix and volume. Without this knowledge, an applicant cannot make an informed decision to join a practice.

Most importantly, be professional. If a candidate is not what you're looking for, be straightforward and tactful. Communicate; don't string someone along in case another prospect falls through.

For those of you who are getting ready to or are still looking for your first job- do your homework. Converse with your faculty members, get in touch with the local device reps, and talk to former fellows about your job prospects. On the interview don't hesitate to pull the ancillary staff aside for their opinion of the group. One of my co-fellows did this and learned that the surgeon had not booked a case in the operating room for six months. The hospital administrators confessed that they were interviewing to replace the surgeon, not hire on a partner.