User login

The Hospitalist only

Inpatient telemedicine can help address hospitalist pain points

COVID-19 has increased confidence in the technology

Since the advent of COVID-19, health care has seen an unprecedented rise in virtual health. Telemedicine has come to the forefront of our conversations, and there are many speculations around its future state. One such discussion is around the sustainability and expansion of inpatient telemedicine programs post COVID, and if – and how – it is going to be helpful for health care.

Consider the following scenarios:

Scenario 1

A patient presents to an emergency department of a small community hospital. He needs to be seen by a specialist, but (s)he is not available, so patient gets transferred out to the ED of a different hospital several miles away from his hometown.

He is evaluated in the second ED by the specialist, has repeat testing done – some of those tests were already completed at the first hospital. After evaluating him, the specialist recommends that he does not need to be admitted to the hospital and can be safely followed up as an outpatient. The patient does not require any further intervention and is discharged from the ED.

Scenario 2

Dr. N is a hospitalist in a rural hospital that does not have intensivist support at night. She works 7 on/7 off and is on call 24/7 during her “on” week. Dr. N cannot be physically present in the hospital 24/7. She receives messages from the hospital around the clock and feels that this call schedule is no longer sustainable. She doesn’t feel comfortable admitting patients in the ICU who come to the hospital at night without physically seeing them and without ICU backup. Therefore, some of the patients who are sick enough to be admitted in ICU for closer monitoring but can be potentially handled in this rural hospital get transferred out to a different hospital.

Dr. N has been asking the hospital to provide her intensivist back up at night and to give her some flexibility in the call schedule. However, from hospital’s perspective, the volume isn’t high enough to hire a dedicated nocturnist, and because the hospital is in the small rural area, it is having a hard time attracting more intensivists. After multiple conversations between both parties, Dr. N finally resigns.

Scenario 3

Dr. A is a specialist who is on call covering different hospitals and seeing patients in clinic. His call is getting busier. He has received many new consults and also has to follow up on his other patients in hospital who he saw a day prior.

Dr. A started receiving many pages from the hospitals – some of his patients and their families are anxiously waiting on him so that he can let them go home once he sees them, while some are waiting to know what the next steps and plan of action are. He ends up canceling some of his clinic patients who had scheduled an appointment with him 3, 4, or even 5 months ago. It’s already afternoon.

Dr. A now drives to one hospital, sees his new consults, orders tests which may or may not get results the same day, follows up on other patients, reviews their test results, modifies treatment plans for some while clearing other patients for discharge. He then drives to the other hospital and follows the same process. Some of the patients aren’t happy because of the long wait, a few couldn’t arrange for the ride to go home and ended up staying in hospital 1 extra night, while the ER is getting backlogged waiting on discharges.

These scenarios highlight some of the important and prevalent pain points in health care as shown in Figure 1.

Scenario 1 and part of scenario 2 describe what is called potentially avoidable interfacility transfers. One study showed that around 8% of transferred patients (transferred from one ED to another) were discharged after ED evaluation in the second hospital, meaning they could have been retained locally without necessarily getting transferred if they could have been evaluated by the specialist.1

Transferring a patient from one hospital to another isn’t as simple as picking up a person from point A and dropping him off at point B. Rather it’s a very complicated, high-risk, capital-intensive, and time-consuming process that leads not only to excessive cost involved around transfer but also adds additional stress and burden on the patient and family. In these scenarios, having a specialist available via teleconsult could have eliminated much of this hassle and cost, allowing the patient to stay locally close to family and get access to necessary medical expertise from any part of the country in a timely manner.

Scenario 2 talks about the recruitment and retention challenges in low-volume, low-resourced locations because of call schedule and the lack of specialty support. It is reported in one study that 19% of common hospitalist admissions happen between 7:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m. Eighty percent of admissions occurred prior to midnight. Nonrural facilities averaged 6.69 hospitalist admissions per night in that study, whereas rural facilities averaged 1.35 admissions.2 It’s like a double-edged sword for such facilities. While having a dedicated nocturnist is not a sustainable model for these hospitals, not having adequate support at night impacts physician wellness, which is already costing hospitals billions of dollars as well as leading to physician turnover: It could cost a hospital somewhere between $500,000 and $1 million to replace just one physician.3 Hence, the potential exists for a telehospitalist program in these settings to address this dilemma.

Scenario 3 sheds light on the operational issues resulting in reduced patient satisfaction and lost revenues, both on the outpatient and inpatient sides by cancellation of office visits and ED backlog. Telemedicine use in these situations can improve the turnaround time of physicians who can see some of those patients while staying at one location as they wait on other patients to show up in the clinic or wait on the operation room crew, or the procedure kit etcetera, hence improving the length of stay, ED throughput, patient satisfaction, and quality of care. This also can improve overall workflow and the wellness of physicians.

One common outcome in all these scenarios is emergency department overcrowding. There have been multiple studies that suggest that ED overcrowding can result in increased costs, lost revenues, and poor clinical outcomes, including delayed administration of antibiotics, delayed administration of analgesics to suffering patients, increased hospital length of stay, and even increased mortality.4-6 A crowded ED limits the ability of an institution to accept referrals and increases medicolegal risks. (See Figure 2.)

Another study showed that a 1-hour reduction in ED boarding time would result in over $9,000 of additional revenue by reducing ambulance diversion and the number of patients who left without being seen.7 Another found that using tele-emergency services can potentially result in net savings of $3,823 per avoided transfer, while accounting for the costs related to tele-emergency technology, hospital revenues, and patient-associated savings.8

There are other instances where gaps in staffing and cracks in workflow can have a negative impact on hospital operations. For example, the busier hospitals that do have a dedicated nocturnist also struggle with physician retention, since such hospitals have higher volumes and higher cross-coverage needs, and are therefore hard to manage by just one single physician at night. Since these are temporary surges, hiring another full-time nocturnist is not a viable option for the hospitals and is considered an expense in many places.

Similarly, during day shift, if a physician goes on vacation or there are surges in patient volumes, hiring a locum tenens hospitalist can be an expensive option, since the cost also includes travel and lodging. In many instances, hiring locum tenens in a given time frame is also not possible, and it leaves the physicians short staffed, fueling both physicians’ and patients’ dissatisfaction and leading to other operational and safety challenges, which I highlighted above.

Telemedicine services in these situations can provide cross-coverage while nocturnists can focus on admissions and other acute issues. Also, when physicians are on vacation or there is surge capacity (that can be forecast by using various predictive analytics models), hospitals can make plans accordingly and make use of telemedicine services. For example, Providence St. Joseph Health reported improvement in timeliness and efficiency of care after implementation of a telehospitalist program. Their 2-year study at a partner site showed a 59% improvement in patients admitted prior to midnight, about $547,000 improvement in first-day revenue capture, an increase in total revenue days and comparable patient experience scores, and a substantial increase in inpatient census and case mix index.9

Other institutions have successfully implemented some inpatient telemedicine programs – such as telepsych, telestroke, and tele-ICU – and some have also reported positive outcomes in terms of patient satisfaction, improved access, reduced length of stay in the ED, and improved quality metrics. Emory Healthcare in Atlanta reported $4.6 million savings in Medicare costs over a 15-month period from adopting a telemedicine model in the ICU, and a reduction in 60-day readmissions by 2.1%.10 Similarly, another study showed that one large health care center improved its direct contribution margins by 376% (from $7.9 million to $37.7 million) because of increased case volume, shorter lengths of stay, and higher case revenue relative to direct costs. When combined with a logistics center, they reported improved contribution margins by 665% (from $7.9 million to $60.6 million).11

There are barriers to the integration and implementation of inpatient telemedicine, including regulations, reimbursement, physician licensing, adoption of technology, and trust among staff and patients. However, I am cautiously optimistic that increased use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic has allowed patients, physicians, nurses, and health care workers and leaders to gain experience with this technology, which will help them gain confidence and reduce hesitation in adapting to this new digital platform. Ultimately, the extent to which telemedicine is able to positively impact patient care will revolve around overcoming these barriers, likely through an evolution of both the technology itself and the attitudes and regulations surrounding it.

I do not suggest that telemedicine should replace the in-person encounter, but it can be implemented and used successfully in addressing the pain points in U.S. health care. (See Figure 3.)

To that end, the purpose of this article is to spark discussion around different ways of implementing telemedicine in inpatient settings to solve many of the challenges that health care faces today.

Dr. Zia is an internal medicine board-certified physician, serving as a hospitalist and physician adviser in a medically underserved area. She has also served as interim medical director of the department of hospital medicine, and medical staff president, at SIH Herrin Hospital, in Herrin, Ill., part of Southern Illinois Healthcare. She has a special interest in improving access to health care in physician shortage areas.

References

1. Kindermann DR et al. Emergency department transfers and transfer relationships in United States hospitals. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Feb;22(2):157-65.

2. Sanders RB et al. New hospital telemedicine services: Potential market for a nighttime hospitalist service. Telemed J E Health. 2014 Oct 1;20(10):902-8.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Pines JM et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Nov;50(5):510-6.

5. Pines JM and Hollander JE. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Jan;51(1):1-5.

6. Chalfin DB et al. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007 Jun;35(6):1477-83.

7. Pines JM et al. The financial consequences of lost demand and reducing boarding in hospital emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Oct;58(4):331-40.

8. Natafgi N et al. Using tele-emergency to avoid patient transfers in rural emergency. J Telemed Telecare. 2018 Apri;24(3):193-201.

9. Providence.org/telehealthhospitalistcasestudy.

10. Woodruff Health Sciences Center. CMS report: eICU program reduced hospital stays, saved millions, eased provider shortage. 2017 Apr 5.

11. Lilly CM et al. ICU telemedicine program financial outcomes. Chest. 2017 Feb;151(2):286-97.

COVID-19 has increased confidence in the technology

COVID-19 has increased confidence in the technology

Since the advent of COVID-19, health care has seen an unprecedented rise in virtual health. Telemedicine has come to the forefront of our conversations, and there are many speculations around its future state. One such discussion is around the sustainability and expansion of inpatient telemedicine programs post COVID, and if – and how – it is going to be helpful for health care.

Consider the following scenarios:

Scenario 1

A patient presents to an emergency department of a small community hospital. He needs to be seen by a specialist, but (s)he is not available, so patient gets transferred out to the ED of a different hospital several miles away from his hometown.

He is evaluated in the second ED by the specialist, has repeat testing done – some of those tests were already completed at the first hospital. After evaluating him, the specialist recommends that he does not need to be admitted to the hospital and can be safely followed up as an outpatient. The patient does not require any further intervention and is discharged from the ED.

Scenario 2

Dr. N is a hospitalist in a rural hospital that does not have intensivist support at night. She works 7 on/7 off and is on call 24/7 during her “on” week. Dr. N cannot be physically present in the hospital 24/7. She receives messages from the hospital around the clock and feels that this call schedule is no longer sustainable. She doesn’t feel comfortable admitting patients in the ICU who come to the hospital at night without physically seeing them and without ICU backup. Therefore, some of the patients who are sick enough to be admitted in ICU for closer monitoring but can be potentially handled in this rural hospital get transferred out to a different hospital.

Dr. N has been asking the hospital to provide her intensivist back up at night and to give her some flexibility in the call schedule. However, from hospital’s perspective, the volume isn’t high enough to hire a dedicated nocturnist, and because the hospital is in the small rural area, it is having a hard time attracting more intensivists. After multiple conversations between both parties, Dr. N finally resigns.

Scenario 3

Dr. A is a specialist who is on call covering different hospitals and seeing patients in clinic. His call is getting busier. He has received many new consults and also has to follow up on his other patients in hospital who he saw a day prior.

Dr. A started receiving many pages from the hospitals – some of his patients and their families are anxiously waiting on him so that he can let them go home once he sees them, while some are waiting to know what the next steps and plan of action are. He ends up canceling some of his clinic patients who had scheduled an appointment with him 3, 4, or even 5 months ago. It’s already afternoon.

Dr. A now drives to one hospital, sees his new consults, orders tests which may or may not get results the same day, follows up on other patients, reviews their test results, modifies treatment plans for some while clearing other patients for discharge. He then drives to the other hospital and follows the same process. Some of the patients aren’t happy because of the long wait, a few couldn’t arrange for the ride to go home and ended up staying in hospital 1 extra night, while the ER is getting backlogged waiting on discharges.

These scenarios highlight some of the important and prevalent pain points in health care as shown in Figure 1.

Scenario 1 and part of scenario 2 describe what is called potentially avoidable interfacility transfers. One study showed that around 8% of transferred patients (transferred from one ED to another) were discharged after ED evaluation in the second hospital, meaning they could have been retained locally without necessarily getting transferred if they could have been evaluated by the specialist.1

Transferring a patient from one hospital to another isn’t as simple as picking up a person from point A and dropping him off at point B. Rather it’s a very complicated, high-risk, capital-intensive, and time-consuming process that leads not only to excessive cost involved around transfer but also adds additional stress and burden on the patient and family. In these scenarios, having a specialist available via teleconsult could have eliminated much of this hassle and cost, allowing the patient to stay locally close to family and get access to necessary medical expertise from any part of the country in a timely manner.

Scenario 2 talks about the recruitment and retention challenges in low-volume, low-resourced locations because of call schedule and the lack of specialty support. It is reported in one study that 19% of common hospitalist admissions happen between 7:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m. Eighty percent of admissions occurred prior to midnight. Nonrural facilities averaged 6.69 hospitalist admissions per night in that study, whereas rural facilities averaged 1.35 admissions.2 It’s like a double-edged sword for such facilities. While having a dedicated nocturnist is not a sustainable model for these hospitals, not having adequate support at night impacts physician wellness, which is already costing hospitals billions of dollars as well as leading to physician turnover: It could cost a hospital somewhere between $500,000 and $1 million to replace just one physician.3 Hence, the potential exists for a telehospitalist program in these settings to address this dilemma.

Scenario 3 sheds light on the operational issues resulting in reduced patient satisfaction and lost revenues, both on the outpatient and inpatient sides by cancellation of office visits and ED backlog. Telemedicine use in these situations can improve the turnaround time of physicians who can see some of those patients while staying at one location as they wait on other patients to show up in the clinic or wait on the operation room crew, or the procedure kit etcetera, hence improving the length of stay, ED throughput, patient satisfaction, and quality of care. This also can improve overall workflow and the wellness of physicians.

One common outcome in all these scenarios is emergency department overcrowding. There have been multiple studies that suggest that ED overcrowding can result in increased costs, lost revenues, and poor clinical outcomes, including delayed administration of antibiotics, delayed administration of analgesics to suffering patients, increased hospital length of stay, and even increased mortality.4-6 A crowded ED limits the ability of an institution to accept referrals and increases medicolegal risks. (See Figure 2.)

Another study showed that a 1-hour reduction in ED boarding time would result in over $9,000 of additional revenue by reducing ambulance diversion and the number of patients who left without being seen.7 Another found that using tele-emergency services can potentially result in net savings of $3,823 per avoided transfer, while accounting for the costs related to tele-emergency technology, hospital revenues, and patient-associated savings.8

There are other instances where gaps in staffing and cracks in workflow can have a negative impact on hospital operations. For example, the busier hospitals that do have a dedicated nocturnist also struggle with physician retention, since such hospitals have higher volumes and higher cross-coverage needs, and are therefore hard to manage by just one single physician at night. Since these are temporary surges, hiring another full-time nocturnist is not a viable option for the hospitals and is considered an expense in many places.

Similarly, during day shift, if a physician goes on vacation or there are surges in patient volumes, hiring a locum tenens hospitalist can be an expensive option, since the cost also includes travel and lodging. In many instances, hiring locum tenens in a given time frame is also not possible, and it leaves the physicians short staffed, fueling both physicians’ and patients’ dissatisfaction and leading to other operational and safety challenges, which I highlighted above.

Telemedicine services in these situations can provide cross-coverage while nocturnists can focus on admissions and other acute issues. Also, when physicians are on vacation or there is surge capacity (that can be forecast by using various predictive analytics models), hospitals can make plans accordingly and make use of telemedicine services. For example, Providence St. Joseph Health reported improvement in timeliness and efficiency of care after implementation of a telehospitalist program. Their 2-year study at a partner site showed a 59% improvement in patients admitted prior to midnight, about $547,000 improvement in first-day revenue capture, an increase in total revenue days and comparable patient experience scores, and a substantial increase in inpatient census and case mix index.9

Other institutions have successfully implemented some inpatient telemedicine programs – such as telepsych, telestroke, and tele-ICU – and some have also reported positive outcomes in terms of patient satisfaction, improved access, reduced length of stay in the ED, and improved quality metrics. Emory Healthcare in Atlanta reported $4.6 million savings in Medicare costs over a 15-month period from adopting a telemedicine model in the ICU, and a reduction in 60-day readmissions by 2.1%.10 Similarly, another study showed that one large health care center improved its direct contribution margins by 376% (from $7.9 million to $37.7 million) because of increased case volume, shorter lengths of stay, and higher case revenue relative to direct costs. When combined with a logistics center, they reported improved contribution margins by 665% (from $7.9 million to $60.6 million).11

There are barriers to the integration and implementation of inpatient telemedicine, including regulations, reimbursement, physician licensing, adoption of technology, and trust among staff and patients. However, I am cautiously optimistic that increased use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic has allowed patients, physicians, nurses, and health care workers and leaders to gain experience with this technology, which will help them gain confidence and reduce hesitation in adapting to this new digital platform. Ultimately, the extent to which telemedicine is able to positively impact patient care will revolve around overcoming these barriers, likely through an evolution of both the technology itself and the attitudes and regulations surrounding it.

I do not suggest that telemedicine should replace the in-person encounter, but it can be implemented and used successfully in addressing the pain points in U.S. health care. (See Figure 3.)

To that end, the purpose of this article is to spark discussion around different ways of implementing telemedicine in inpatient settings to solve many of the challenges that health care faces today.

Dr. Zia is an internal medicine board-certified physician, serving as a hospitalist and physician adviser in a medically underserved area. She has also served as interim medical director of the department of hospital medicine, and medical staff president, at SIH Herrin Hospital, in Herrin, Ill., part of Southern Illinois Healthcare. She has a special interest in improving access to health care in physician shortage areas.

References

1. Kindermann DR et al. Emergency department transfers and transfer relationships in United States hospitals. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Feb;22(2):157-65.

2. Sanders RB et al. New hospital telemedicine services: Potential market for a nighttime hospitalist service. Telemed J E Health. 2014 Oct 1;20(10):902-8.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Pines JM et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Nov;50(5):510-6.

5. Pines JM and Hollander JE. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Jan;51(1):1-5.

6. Chalfin DB et al. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007 Jun;35(6):1477-83.

7. Pines JM et al. The financial consequences of lost demand and reducing boarding in hospital emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Oct;58(4):331-40.

8. Natafgi N et al. Using tele-emergency to avoid patient transfers in rural emergency. J Telemed Telecare. 2018 Apri;24(3):193-201.

9. Providence.org/telehealthhospitalistcasestudy.

10. Woodruff Health Sciences Center. CMS report: eICU program reduced hospital stays, saved millions, eased provider shortage. 2017 Apr 5.

11. Lilly CM et al. ICU telemedicine program financial outcomes. Chest. 2017 Feb;151(2):286-97.

Since the advent of COVID-19, health care has seen an unprecedented rise in virtual health. Telemedicine has come to the forefront of our conversations, and there are many speculations around its future state. One such discussion is around the sustainability and expansion of inpatient telemedicine programs post COVID, and if – and how – it is going to be helpful for health care.

Consider the following scenarios:

Scenario 1

A patient presents to an emergency department of a small community hospital. He needs to be seen by a specialist, but (s)he is not available, so patient gets transferred out to the ED of a different hospital several miles away from his hometown.

He is evaluated in the second ED by the specialist, has repeat testing done – some of those tests were already completed at the first hospital. After evaluating him, the specialist recommends that he does not need to be admitted to the hospital and can be safely followed up as an outpatient. The patient does not require any further intervention and is discharged from the ED.

Scenario 2

Dr. N is a hospitalist in a rural hospital that does not have intensivist support at night. She works 7 on/7 off and is on call 24/7 during her “on” week. Dr. N cannot be physically present in the hospital 24/7. She receives messages from the hospital around the clock and feels that this call schedule is no longer sustainable. She doesn’t feel comfortable admitting patients in the ICU who come to the hospital at night without physically seeing them and without ICU backup. Therefore, some of the patients who are sick enough to be admitted in ICU for closer monitoring but can be potentially handled in this rural hospital get transferred out to a different hospital.

Dr. N has been asking the hospital to provide her intensivist back up at night and to give her some flexibility in the call schedule. However, from hospital’s perspective, the volume isn’t high enough to hire a dedicated nocturnist, and because the hospital is in the small rural area, it is having a hard time attracting more intensivists. After multiple conversations between both parties, Dr. N finally resigns.

Scenario 3

Dr. A is a specialist who is on call covering different hospitals and seeing patients in clinic. His call is getting busier. He has received many new consults and also has to follow up on his other patients in hospital who he saw a day prior.

Dr. A started receiving many pages from the hospitals – some of his patients and their families are anxiously waiting on him so that he can let them go home once he sees them, while some are waiting to know what the next steps and plan of action are. He ends up canceling some of his clinic patients who had scheduled an appointment with him 3, 4, or even 5 months ago. It’s already afternoon.

Dr. A now drives to one hospital, sees his new consults, orders tests which may or may not get results the same day, follows up on other patients, reviews their test results, modifies treatment plans for some while clearing other patients for discharge. He then drives to the other hospital and follows the same process. Some of the patients aren’t happy because of the long wait, a few couldn’t arrange for the ride to go home and ended up staying in hospital 1 extra night, while the ER is getting backlogged waiting on discharges.

These scenarios highlight some of the important and prevalent pain points in health care as shown in Figure 1.

Scenario 1 and part of scenario 2 describe what is called potentially avoidable interfacility transfers. One study showed that around 8% of transferred patients (transferred from one ED to another) were discharged after ED evaluation in the second hospital, meaning they could have been retained locally without necessarily getting transferred if they could have been evaluated by the specialist.1

Transferring a patient from one hospital to another isn’t as simple as picking up a person from point A and dropping him off at point B. Rather it’s a very complicated, high-risk, capital-intensive, and time-consuming process that leads not only to excessive cost involved around transfer but also adds additional stress and burden on the patient and family. In these scenarios, having a specialist available via teleconsult could have eliminated much of this hassle and cost, allowing the patient to stay locally close to family and get access to necessary medical expertise from any part of the country in a timely manner.

Scenario 2 talks about the recruitment and retention challenges in low-volume, low-resourced locations because of call schedule and the lack of specialty support. It is reported in one study that 19% of common hospitalist admissions happen between 7:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m. Eighty percent of admissions occurred prior to midnight. Nonrural facilities averaged 6.69 hospitalist admissions per night in that study, whereas rural facilities averaged 1.35 admissions.2 It’s like a double-edged sword for such facilities. While having a dedicated nocturnist is not a sustainable model for these hospitals, not having adequate support at night impacts physician wellness, which is already costing hospitals billions of dollars as well as leading to physician turnover: It could cost a hospital somewhere between $500,000 and $1 million to replace just one physician.3 Hence, the potential exists for a telehospitalist program in these settings to address this dilemma.

Scenario 3 sheds light on the operational issues resulting in reduced patient satisfaction and lost revenues, both on the outpatient and inpatient sides by cancellation of office visits and ED backlog. Telemedicine use in these situations can improve the turnaround time of physicians who can see some of those patients while staying at one location as they wait on other patients to show up in the clinic or wait on the operation room crew, or the procedure kit etcetera, hence improving the length of stay, ED throughput, patient satisfaction, and quality of care. This also can improve overall workflow and the wellness of physicians.

One common outcome in all these scenarios is emergency department overcrowding. There have been multiple studies that suggest that ED overcrowding can result in increased costs, lost revenues, and poor clinical outcomes, including delayed administration of antibiotics, delayed administration of analgesics to suffering patients, increased hospital length of stay, and even increased mortality.4-6 A crowded ED limits the ability of an institution to accept referrals and increases medicolegal risks. (See Figure 2.)

Another study showed that a 1-hour reduction in ED boarding time would result in over $9,000 of additional revenue by reducing ambulance diversion and the number of patients who left without being seen.7 Another found that using tele-emergency services can potentially result in net savings of $3,823 per avoided transfer, while accounting for the costs related to tele-emergency technology, hospital revenues, and patient-associated savings.8

There are other instances where gaps in staffing and cracks in workflow can have a negative impact on hospital operations. For example, the busier hospitals that do have a dedicated nocturnist also struggle with physician retention, since such hospitals have higher volumes and higher cross-coverage needs, and are therefore hard to manage by just one single physician at night. Since these are temporary surges, hiring another full-time nocturnist is not a viable option for the hospitals and is considered an expense in many places.

Similarly, during day shift, if a physician goes on vacation or there are surges in patient volumes, hiring a locum tenens hospitalist can be an expensive option, since the cost also includes travel and lodging. In many instances, hiring locum tenens in a given time frame is also not possible, and it leaves the physicians short staffed, fueling both physicians’ and patients’ dissatisfaction and leading to other operational and safety challenges, which I highlighted above.

Telemedicine services in these situations can provide cross-coverage while nocturnists can focus on admissions and other acute issues. Also, when physicians are on vacation or there is surge capacity (that can be forecast by using various predictive analytics models), hospitals can make plans accordingly and make use of telemedicine services. For example, Providence St. Joseph Health reported improvement in timeliness and efficiency of care after implementation of a telehospitalist program. Their 2-year study at a partner site showed a 59% improvement in patients admitted prior to midnight, about $547,000 improvement in first-day revenue capture, an increase in total revenue days and comparable patient experience scores, and a substantial increase in inpatient census and case mix index.9

Other institutions have successfully implemented some inpatient telemedicine programs – such as telepsych, telestroke, and tele-ICU – and some have also reported positive outcomes in terms of patient satisfaction, improved access, reduced length of stay in the ED, and improved quality metrics. Emory Healthcare in Atlanta reported $4.6 million savings in Medicare costs over a 15-month period from adopting a telemedicine model in the ICU, and a reduction in 60-day readmissions by 2.1%.10 Similarly, another study showed that one large health care center improved its direct contribution margins by 376% (from $7.9 million to $37.7 million) because of increased case volume, shorter lengths of stay, and higher case revenue relative to direct costs. When combined with a logistics center, they reported improved contribution margins by 665% (from $7.9 million to $60.6 million).11

There are barriers to the integration and implementation of inpatient telemedicine, including regulations, reimbursement, physician licensing, adoption of technology, and trust among staff and patients. However, I am cautiously optimistic that increased use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic has allowed patients, physicians, nurses, and health care workers and leaders to gain experience with this technology, which will help them gain confidence and reduce hesitation in adapting to this new digital platform. Ultimately, the extent to which telemedicine is able to positively impact patient care will revolve around overcoming these barriers, likely through an evolution of both the technology itself and the attitudes and regulations surrounding it.

I do not suggest that telemedicine should replace the in-person encounter, but it can be implemented and used successfully in addressing the pain points in U.S. health care. (See Figure 3.)

To that end, the purpose of this article is to spark discussion around different ways of implementing telemedicine in inpatient settings to solve many of the challenges that health care faces today.

Dr. Zia is an internal medicine board-certified physician, serving as a hospitalist and physician adviser in a medically underserved area. She has also served as interim medical director of the department of hospital medicine, and medical staff president, at SIH Herrin Hospital, in Herrin, Ill., part of Southern Illinois Healthcare. She has a special interest in improving access to health care in physician shortage areas.

References

1. Kindermann DR et al. Emergency department transfers and transfer relationships in United States hospitals. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Feb;22(2):157-65.

2. Sanders RB et al. New hospital telemedicine services: Potential market for a nighttime hospitalist service. Telemed J E Health. 2014 Oct 1;20(10):902-8.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Pines JM et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Nov;50(5):510-6.

5. Pines JM and Hollander JE. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Jan;51(1):1-5.

6. Chalfin DB et al. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007 Jun;35(6):1477-83.

7. Pines JM et al. The financial consequences of lost demand and reducing boarding in hospital emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Oct;58(4):331-40.

8. Natafgi N et al. Using tele-emergency to avoid patient transfers in rural emergency. J Telemed Telecare. 2018 Apri;24(3):193-201.

9. Providence.org/telehealthhospitalistcasestudy.

10. Woodruff Health Sciences Center. CMS report: eICU program reduced hospital stays, saved millions, eased provider shortage. 2017 Apr 5.

11. Lilly CM et al. ICU telemedicine program financial outcomes. Chest. 2017 Feb;151(2):286-97.

Accessing data during EHR downtime

Reducing loss of efficiency

Electronic health record (EHR) implementations involve long downtimes, which are an under-recognized patient safety risk, as clinicians are forced to switch to completely manual, paper-based, and important unfamiliar workflows to care for their acutely ill patients, said Subha Airan-Javia, MD, FAMIA, a hospitalist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In this setting, we discovered an unanticipated benefit of our tool [Carelign, initially built to digitize the handoff process] as a clinical resource during EHR downtime, giving clinicians access to critical data as well as an electronic platform to collaborate as a team around the care of their patients,” she said.

There are two important takeaways from their study on this issue. “The first is that Carelign was able to give clinicians access to clinical data that would otherwise have been unavailable, including vitals, labs, medications, care plans and care team assignments,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “This undoubtedly mitigated patient safety risks during the EHR downtime.”

The second: “As many clinicians know, any change in workflow, even for a few hours, can make providing a high level of patient care very difficult,” she added. “During a downtime without a tool like Carelign, clinicians have to rely on paper and bedside charts, writing notes on paper and then re-typing them into the EHR when it is back up. This adds to the already excessive amount of administrative work that is burning clinicians out.” Using a tool like Carelign means no such loss in efficiency.

“A tool like Carelign, particularly because it is something that can be used without having to integrate it with the EHR, can put some control back into a hospitalist’s hands, to have a say in their workflow,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “In a world where EHRs are designed to optimize billing, it can be game-changer to have a tool like Carelign that was created by a practicing clinician, for clinicians. Anyone interested in this area is welcome to reach out to me at subhaairan@gmail.com for collaboration or more information.”

Reference

1. Airan-Javia SL, et al. Mind the gap: Revolutionizing the EHR downtime experience with an interoperable workflow tool. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2019, March 24-27, National Harbor, Md. Abstract 380. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/mind-the-gap-revolutionizing-the-ehr-downtime-experience-with-an-interoperable-workflow-tool/. Accessed Dec 11, 2019.

Reducing loss of efficiency

Reducing loss of efficiency

Electronic health record (EHR) implementations involve long downtimes, which are an under-recognized patient safety risk, as clinicians are forced to switch to completely manual, paper-based, and important unfamiliar workflows to care for their acutely ill patients, said Subha Airan-Javia, MD, FAMIA, a hospitalist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In this setting, we discovered an unanticipated benefit of our tool [Carelign, initially built to digitize the handoff process] as a clinical resource during EHR downtime, giving clinicians access to critical data as well as an electronic platform to collaborate as a team around the care of their patients,” she said.

There are two important takeaways from their study on this issue. “The first is that Carelign was able to give clinicians access to clinical data that would otherwise have been unavailable, including vitals, labs, medications, care plans and care team assignments,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “This undoubtedly mitigated patient safety risks during the EHR downtime.”

The second: “As many clinicians know, any change in workflow, even for a few hours, can make providing a high level of patient care very difficult,” she added. “During a downtime without a tool like Carelign, clinicians have to rely on paper and bedside charts, writing notes on paper and then re-typing them into the EHR when it is back up. This adds to the already excessive amount of administrative work that is burning clinicians out.” Using a tool like Carelign means no such loss in efficiency.

“A tool like Carelign, particularly because it is something that can be used without having to integrate it with the EHR, can put some control back into a hospitalist’s hands, to have a say in their workflow,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “In a world where EHRs are designed to optimize billing, it can be game-changer to have a tool like Carelign that was created by a practicing clinician, for clinicians. Anyone interested in this area is welcome to reach out to me at subhaairan@gmail.com for collaboration or more information.”

Reference

1. Airan-Javia SL, et al. Mind the gap: Revolutionizing the EHR downtime experience with an interoperable workflow tool. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2019, March 24-27, National Harbor, Md. Abstract 380. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/mind-the-gap-revolutionizing-the-ehr-downtime-experience-with-an-interoperable-workflow-tool/. Accessed Dec 11, 2019.

Electronic health record (EHR) implementations involve long downtimes, which are an under-recognized patient safety risk, as clinicians are forced to switch to completely manual, paper-based, and important unfamiliar workflows to care for their acutely ill patients, said Subha Airan-Javia, MD, FAMIA, a hospitalist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In this setting, we discovered an unanticipated benefit of our tool [Carelign, initially built to digitize the handoff process] as a clinical resource during EHR downtime, giving clinicians access to critical data as well as an electronic platform to collaborate as a team around the care of their patients,” she said.

There are two important takeaways from their study on this issue. “The first is that Carelign was able to give clinicians access to clinical data that would otherwise have been unavailable, including vitals, labs, medications, care plans and care team assignments,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “This undoubtedly mitigated patient safety risks during the EHR downtime.”

The second: “As many clinicians know, any change in workflow, even for a few hours, can make providing a high level of patient care very difficult,” she added. “During a downtime without a tool like Carelign, clinicians have to rely on paper and bedside charts, writing notes on paper and then re-typing them into the EHR when it is back up. This adds to the already excessive amount of administrative work that is burning clinicians out.” Using a tool like Carelign means no such loss in efficiency.

“A tool like Carelign, particularly because it is something that can be used without having to integrate it with the EHR, can put some control back into a hospitalist’s hands, to have a say in their workflow,” Dr. Airan-Javia said. “In a world where EHRs are designed to optimize billing, it can be game-changer to have a tool like Carelign that was created by a practicing clinician, for clinicians. Anyone interested in this area is welcome to reach out to me at subhaairan@gmail.com for collaboration or more information.”

Reference

1. Airan-Javia SL, et al. Mind the gap: Revolutionizing the EHR downtime experience with an interoperable workflow tool. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2019, March 24-27, National Harbor, Md. Abstract 380. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/mind-the-gap-revolutionizing-the-ehr-downtime-experience-with-an-interoperable-workflow-tool/. Accessed Dec 11, 2019.

Roots of physician burnout: It’s the work load

Work load, not personal vulnerability, may be at the root of the current physician burnout crisis, a recent study has concluded.

The cutting-edge research utilized cognitive theory and work load analysis to get at the source of burnout among practitioners. The findings indicate that, although some institutions continue to emphasize personal responsibility of physicians to address the issue, it may be the amount and structure of the work itself that triggers burnout in doctors.

“We evaluated the cognitive load of a clinical workday in a national sample of U.S. physicians and its relationship with burnout and professional satisfaction,” wrote Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora and coauthors. The results were reported in the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

The researchers investigated whether task load correlated with burnout scores in a large national study of U.S. physicians from October 2017 to March 2018.

As the delivery of health care becomes more complex, physicians are charged with ever-increasing amount of administrative and cognitive tasks. Recent evidence indicates that this growing complexity of work is tied to a greater risk of burnout in physicians, compared with workers in other fields. Cognitive load theory, pioneered by psychologist Jonathan Sweller, identified limitations in working memory that humans depend on to carry out cognitive tasks. Cognitive load refers to the amount of working memory used, which can be reduced in the presence of external emotional or physiological stressors. While a potential link between cognitive load and burnout may seem self-evident, the correlation between the cognitive load of physicians and burnout has not been evaluated in a large-scale study until recently.

Physician task load (PTL) was measured using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), a validated questionnaire frequently used to evaluate the cognitive load of work environments, including health care environments. Four domains (perception of effort and mental, physical, and temporal demands) were used to calculate the total PTL score.

Burnout was evaluated using the Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization scales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a validated tool considered the gold standard for measurement.

The survey sample consisted of physicians of all specialties and was assembled using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, an almost complete record of all U.S. physicians independent of AMA membership. All responses were anonymous and participation was voluntary.

Results

Among 30,456 physicians who received the survey, 5,197 (17.1%) responded. In total, 5,276 physicians were included in the analysis.

The median age of respondents was 53 years, and 61.8% self-identified as male. Twenty-four specialties were identified: 23.8% were from a primary care discipline and internal medicine represented the largest respondent group (12.1%).

Almost half of respondents (49.7%) worked in private practice, and 44.8% had been in practice for 21 years or longer.

Overall, 44.0% had at least one symptom of burnout, 38.8% of participants scored in the high range for emotional exhaustion, and 27.4% scored in the high range for depersonalization. The mean score in task load dimension varied by specialty.

The mean PTL score was 260.9 (standard deviation, 71.4). The specialties with the highest PTL score were emergency medicine (369.8), urology (353.7), general surgery subspecialties (343.9), internal medicine subspecialties (342.2), and radiology (341.6).

Aside from specialty, PTL scores also varied by practice setting, gender, age, number of hours worked per week, number of nights on call per week, and years in practice.

The researchers observed a dose response relationship between PTL and risk of burnout. For every 40-point (10%) reduction in PTL, there was 33% lower odds of experiencing burnout (odds ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.70; P < .0001). Multivariable analyses also indicated that PTL was a significant predictor of burnout, independent of practice setting, specialty, age, gender, and hours worked.

Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout

Coauthors of the study, Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University and Colin P. West, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., are both experts on physician well-being and are passionate about finding new ways to reduce physician distress and improving health care delivery.

“Authentic efforts to address this problem must move beyond personal resilience,” Dr. Shanafelt said in an interview. “Organizations that fail to get serious about this issue are going to be left behind and struggle in the war for talent.

“Much like our efforts to improve quality, advancing clinician well-being requires organizations to make it a priority and establish the structure, process, and leadership to promote the desired outcomes,” said Dr. Shanafelt.

One potential strategy for improvement is appointing a chief wellness officer, a dedicated individual within the health care system that leads the organizational effort, explained Dr. Shanafelt. “Over 30 vanguard institutions across the United States have already taken this step.”

Dr. West, a coauthor of the study, explained that conducting an analysis of PTL is fairly straightforward for hospitals and individual institutions. “The NASA-TLX tool is widely available, free to use, and not overly complex, and it could be used to provide insight into physician effort and mental, physical, and temporal demand levels,” he said in an interview.

“Deeper evaluations could follow to identify specific potential solutions, particularly system-level approaches to alleviate PTL,” Dr. West explained. “In the short term, such analyses and solutions would have costs, but helping physicians work more optimally and with less chronic strain from excessive task load would save far more than these costs overall.”

Dr. West also noted that physician burnout is very expensive to a health care system, and strategies to promote physician well-being would be a prudent financial decision long term for health care organizations.

Dr. Harry, lead author of the study, agreed with Dr. West, noting that “quality improvement literature has demonstrated that improvements in inefficiencies that lead to increased demand in the workplace often has the benefit of reduced cost.

“Many studies have demonstrated the risk of turnover due to burnout and the significant cost of physician turn over,” she said in an interview. “This cost avoidance is well worth the investment in improved operations to minimize unnecessary task load.”

Dr. Harry also recommended the NASA-TLX tool as a free resource for health systems and organizations. She noted that future studies will further validate the reliability of the tool.

“At the core, we need to focus on system redesign at both the micro and the macro level,” Dr. Harry said. “Each health system will need to assess inefficiencies in their work flow, while regulatory bodies need to consider the downstream task load of mandates and reporting requirements, all of which contribute to more cognitive load.”

The study was supported by funding from the Stanford Medicine WellMD Center, the American Medical Association, and the Mayo Clinic department of medicine program on physician well-being. Coauthors Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, and Dr. Shanafelt are coinventors of the Physician Well-being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being, and Well-Being Index. Mayo Clinic holds the copyright to these instruments and has licensed them for external use. Dr. Dyrbye and Dr. Shanafelt receive a portion of any royalties paid to Mayo Clinic. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Work load, not personal vulnerability, may be at the root of the current physician burnout crisis, a recent study has concluded.

The cutting-edge research utilized cognitive theory and work load analysis to get at the source of burnout among practitioners. The findings indicate that, although some institutions continue to emphasize personal responsibility of physicians to address the issue, it may be the amount and structure of the work itself that triggers burnout in doctors.

“We evaluated the cognitive load of a clinical workday in a national sample of U.S. physicians and its relationship with burnout and professional satisfaction,” wrote Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora and coauthors. The results were reported in the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

The researchers investigated whether task load correlated with burnout scores in a large national study of U.S. physicians from October 2017 to March 2018.

As the delivery of health care becomes more complex, physicians are charged with ever-increasing amount of administrative and cognitive tasks. Recent evidence indicates that this growing complexity of work is tied to a greater risk of burnout in physicians, compared with workers in other fields. Cognitive load theory, pioneered by psychologist Jonathan Sweller, identified limitations in working memory that humans depend on to carry out cognitive tasks. Cognitive load refers to the amount of working memory used, which can be reduced in the presence of external emotional or physiological stressors. While a potential link between cognitive load and burnout may seem self-evident, the correlation between the cognitive load of physicians and burnout has not been evaluated in a large-scale study until recently.

Physician task load (PTL) was measured using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), a validated questionnaire frequently used to evaluate the cognitive load of work environments, including health care environments. Four domains (perception of effort and mental, physical, and temporal demands) were used to calculate the total PTL score.

Burnout was evaluated using the Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization scales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a validated tool considered the gold standard for measurement.

The survey sample consisted of physicians of all specialties and was assembled using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, an almost complete record of all U.S. physicians independent of AMA membership. All responses were anonymous and participation was voluntary.

Results

Among 30,456 physicians who received the survey, 5,197 (17.1%) responded. In total, 5,276 physicians were included in the analysis.

The median age of respondents was 53 years, and 61.8% self-identified as male. Twenty-four specialties were identified: 23.8% were from a primary care discipline and internal medicine represented the largest respondent group (12.1%).

Almost half of respondents (49.7%) worked in private practice, and 44.8% had been in practice for 21 years or longer.

Overall, 44.0% had at least one symptom of burnout, 38.8% of participants scored in the high range for emotional exhaustion, and 27.4% scored in the high range for depersonalization. The mean score in task load dimension varied by specialty.

The mean PTL score was 260.9 (standard deviation, 71.4). The specialties with the highest PTL score were emergency medicine (369.8), urology (353.7), general surgery subspecialties (343.9), internal medicine subspecialties (342.2), and radiology (341.6).

Aside from specialty, PTL scores also varied by practice setting, gender, age, number of hours worked per week, number of nights on call per week, and years in practice.

The researchers observed a dose response relationship between PTL and risk of burnout. For every 40-point (10%) reduction in PTL, there was 33% lower odds of experiencing burnout (odds ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.70; P < .0001). Multivariable analyses also indicated that PTL was a significant predictor of burnout, independent of practice setting, specialty, age, gender, and hours worked.

Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout

Coauthors of the study, Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University and Colin P. West, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., are both experts on physician well-being and are passionate about finding new ways to reduce physician distress and improving health care delivery.

“Authentic efforts to address this problem must move beyond personal resilience,” Dr. Shanafelt said in an interview. “Organizations that fail to get serious about this issue are going to be left behind and struggle in the war for talent.

“Much like our efforts to improve quality, advancing clinician well-being requires organizations to make it a priority and establish the structure, process, and leadership to promote the desired outcomes,” said Dr. Shanafelt.

One potential strategy for improvement is appointing a chief wellness officer, a dedicated individual within the health care system that leads the organizational effort, explained Dr. Shanafelt. “Over 30 vanguard institutions across the United States have already taken this step.”

Dr. West, a coauthor of the study, explained that conducting an analysis of PTL is fairly straightforward for hospitals and individual institutions. “The NASA-TLX tool is widely available, free to use, and not overly complex, and it could be used to provide insight into physician effort and mental, physical, and temporal demand levels,” he said in an interview.

“Deeper evaluations could follow to identify specific potential solutions, particularly system-level approaches to alleviate PTL,” Dr. West explained. “In the short term, such analyses and solutions would have costs, but helping physicians work more optimally and with less chronic strain from excessive task load would save far more than these costs overall.”

Dr. West also noted that physician burnout is very expensive to a health care system, and strategies to promote physician well-being would be a prudent financial decision long term for health care organizations.

Dr. Harry, lead author of the study, agreed with Dr. West, noting that “quality improvement literature has demonstrated that improvements in inefficiencies that lead to increased demand in the workplace often has the benefit of reduced cost.

“Many studies have demonstrated the risk of turnover due to burnout and the significant cost of physician turn over,” she said in an interview. “This cost avoidance is well worth the investment in improved operations to minimize unnecessary task load.”

Dr. Harry also recommended the NASA-TLX tool as a free resource for health systems and organizations. She noted that future studies will further validate the reliability of the tool.

“At the core, we need to focus on system redesign at both the micro and the macro level,” Dr. Harry said. “Each health system will need to assess inefficiencies in their work flow, while regulatory bodies need to consider the downstream task load of mandates and reporting requirements, all of which contribute to more cognitive load.”

The study was supported by funding from the Stanford Medicine WellMD Center, the American Medical Association, and the Mayo Clinic department of medicine program on physician well-being. Coauthors Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, and Dr. Shanafelt are coinventors of the Physician Well-being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being, and Well-Being Index. Mayo Clinic holds the copyright to these instruments and has licensed them for external use. Dr. Dyrbye and Dr. Shanafelt receive a portion of any royalties paid to Mayo Clinic. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Work load, not personal vulnerability, may be at the root of the current physician burnout crisis, a recent study has concluded.

The cutting-edge research utilized cognitive theory and work load analysis to get at the source of burnout among practitioners. The findings indicate that, although some institutions continue to emphasize personal responsibility of physicians to address the issue, it may be the amount and structure of the work itself that triggers burnout in doctors.

“We evaluated the cognitive load of a clinical workday in a national sample of U.S. physicians and its relationship with burnout and professional satisfaction,” wrote Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora and coauthors. The results were reported in the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

The researchers investigated whether task load correlated with burnout scores in a large national study of U.S. physicians from October 2017 to March 2018.

As the delivery of health care becomes more complex, physicians are charged with ever-increasing amount of administrative and cognitive tasks. Recent evidence indicates that this growing complexity of work is tied to a greater risk of burnout in physicians, compared with workers in other fields. Cognitive load theory, pioneered by psychologist Jonathan Sweller, identified limitations in working memory that humans depend on to carry out cognitive tasks. Cognitive load refers to the amount of working memory used, which can be reduced in the presence of external emotional or physiological stressors. While a potential link between cognitive load and burnout may seem self-evident, the correlation between the cognitive load of physicians and burnout has not been evaluated in a large-scale study until recently.

Physician task load (PTL) was measured using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), a validated questionnaire frequently used to evaluate the cognitive load of work environments, including health care environments. Four domains (perception of effort and mental, physical, and temporal demands) were used to calculate the total PTL score.

Burnout was evaluated using the Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization scales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a validated tool considered the gold standard for measurement.

The survey sample consisted of physicians of all specialties and was assembled using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, an almost complete record of all U.S. physicians independent of AMA membership. All responses were anonymous and participation was voluntary.

Results

Among 30,456 physicians who received the survey, 5,197 (17.1%) responded. In total, 5,276 physicians were included in the analysis.

The median age of respondents was 53 years, and 61.8% self-identified as male. Twenty-four specialties were identified: 23.8% were from a primary care discipline and internal medicine represented the largest respondent group (12.1%).

Almost half of respondents (49.7%) worked in private practice, and 44.8% had been in practice for 21 years or longer.

Overall, 44.0% had at least one symptom of burnout, 38.8% of participants scored in the high range for emotional exhaustion, and 27.4% scored in the high range for depersonalization. The mean score in task load dimension varied by specialty.

The mean PTL score was 260.9 (standard deviation, 71.4). The specialties with the highest PTL score were emergency medicine (369.8), urology (353.7), general surgery subspecialties (343.9), internal medicine subspecialties (342.2), and radiology (341.6).

Aside from specialty, PTL scores also varied by practice setting, gender, age, number of hours worked per week, number of nights on call per week, and years in practice.

The researchers observed a dose response relationship between PTL and risk of burnout. For every 40-point (10%) reduction in PTL, there was 33% lower odds of experiencing burnout (odds ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.70; P < .0001). Multivariable analyses also indicated that PTL was a significant predictor of burnout, independent of practice setting, specialty, age, gender, and hours worked.

Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout

Coauthors of the study, Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University and Colin P. West, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., are both experts on physician well-being and are passionate about finding new ways to reduce physician distress and improving health care delivery.

“Authentic efforts to address this problem must move beyond personal resilience,” Dr. Shanafelt said in an interview. “Organizations that fail to get serious about this issue are going to be left behind and struggle in the war for talent.

“Much like our efforts to improve quality, advancing clinician well-being requires organizations to make it a priority and establish the structure, process, and leadership to promote the desired outcomes,” said Dr. Shanafelt.

One potential strategy for improvement is appointing a chief wellness officer, a dedicated individual within the health care system that leads the organizational effort, explained Dr. Shanafelt. “Over 30 vanguard institutions across the United States have already taken this step.”

Dr. West, a coauthor of the study, explained that conducting an analysis of PTL is fairly straightforward for hospitals and individual institutions. “The NASA-TLX tool is widely available, free to use, and not overly complex, and it could be used to provide insight into physician effort and mental, physical, and temporal demand levels,” he said in an interview.

“Deeper evaluations could follow to identify specific potential solutions, particularly system-level approaches to alleviate PTL,” Dr. West explained. “In the short term, such analyses and solutions would have costs, but helping physicians work more optimally and with less chronic strain from excessive task load would save far more than these costs overall.”

Dr. West also noted that physician burnout is very expensive to a health care system, and strategies to promote physician well-being would be a prudent financial decision long term for health care organizations.

Dr. Harry, lead author of the study, agreed with Dr. West, noting that “quality improvement literature has demonstrated that improvements in inefficiencies that lead to increased demand in the workplace often has the benefit of reduced cost.

“Many studies have demonstrated the risk of turnover due to burnout and the significant cost of physician turn over,” she said in an interview. “This cost avoidance is well worth the investment in improved operations to minimize unnecessary task load.”

Dr. Harry also recommended the NASA-TLX tool as a free resource for health systems and organizations. She noted that future studies will further validate the reliability of the tool.

“At the core, we need to focus on system redesign at both the micro and the macro level,” Dr. Harry said. “Each health system will need to assess inefficiencies in their work flow, while regulatory bodies need to consider the downstream task load of mandates and reporting requirements, all of which contribute to more cognitive load.”

The study was supported by funding from the Stanford Medicine WellMD Center, the American Medical Association, and the Mayo Clinic department of medicine program on physician well-being. Coauthors Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, and Dr. Shanafelt are coinventors of the Physician Well-being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being, and Well-Being Index. Mayo Clinic holds the copyright to these instruments and has licensed them for external use. Dr. Dyrbye and Dr. Shanafelt receive a portion of any royalties paid to Mayo Clinic. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOINT COMMISSION JOURNAL ON QUALITY AND PATIENT SAFETY

Key trends in hospitalist compensation from the 2020 SoHM Report

In a time of tremendous uncertainty, there is one trend that seems consistent year over year – the undisputed value of hospitalists. In the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report, the Society of Hospital Medicine partnered with the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) to provide data on hospitalist compensation and productivity. The Report provides resounding evidence that hospitalists continue to be compensated at rising rates. This may be driven by both the continued demand-supply mismatch and a recognition of the overall value they generate rather than strictly the volume of their productivity.

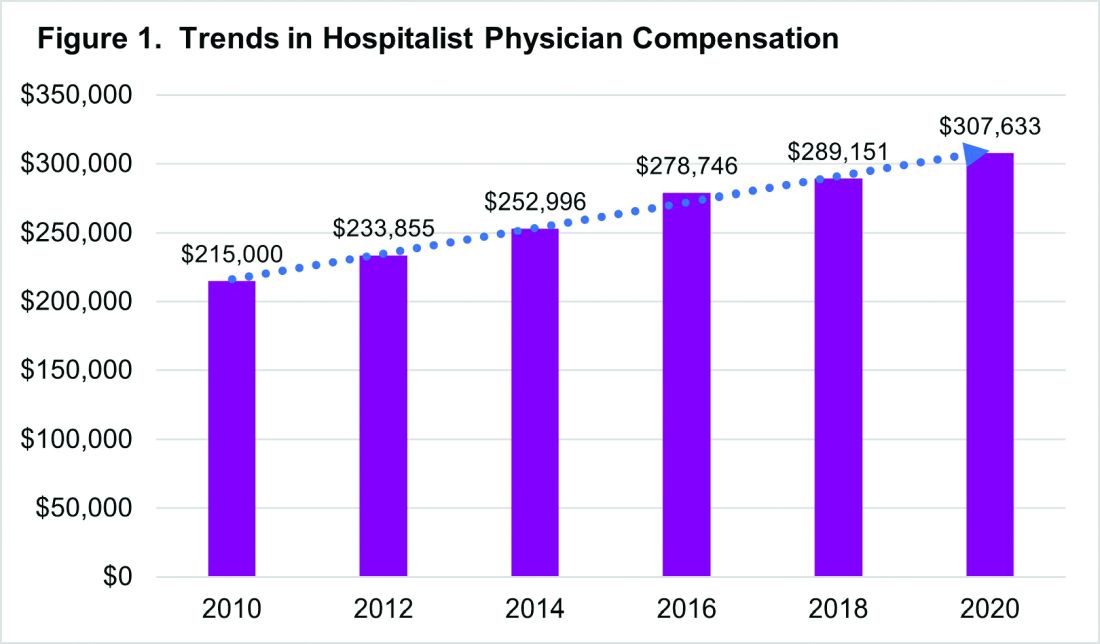

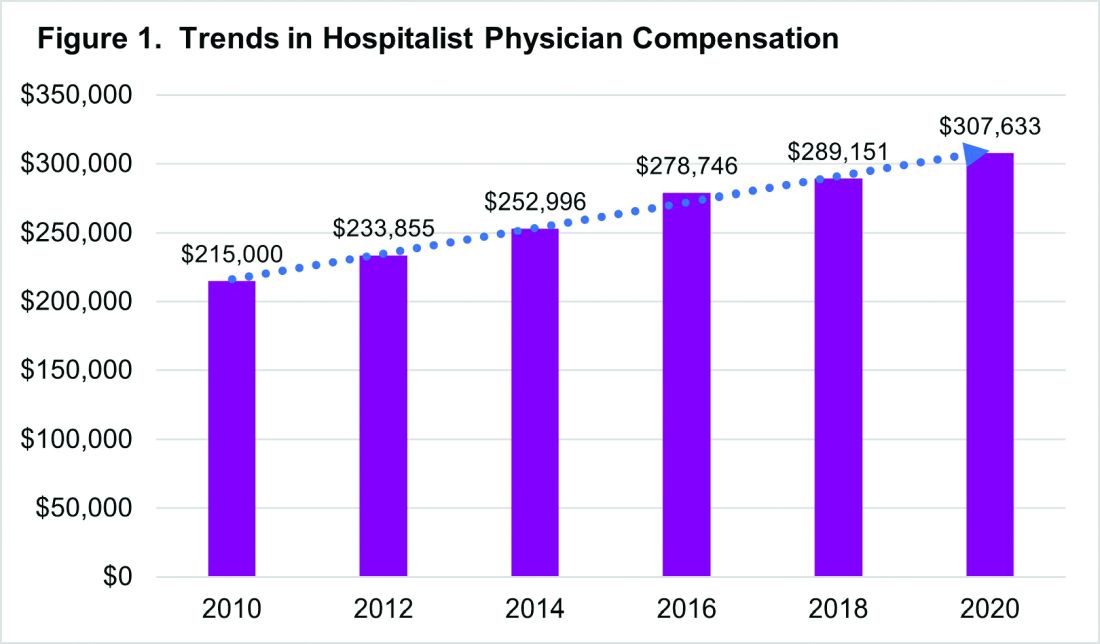

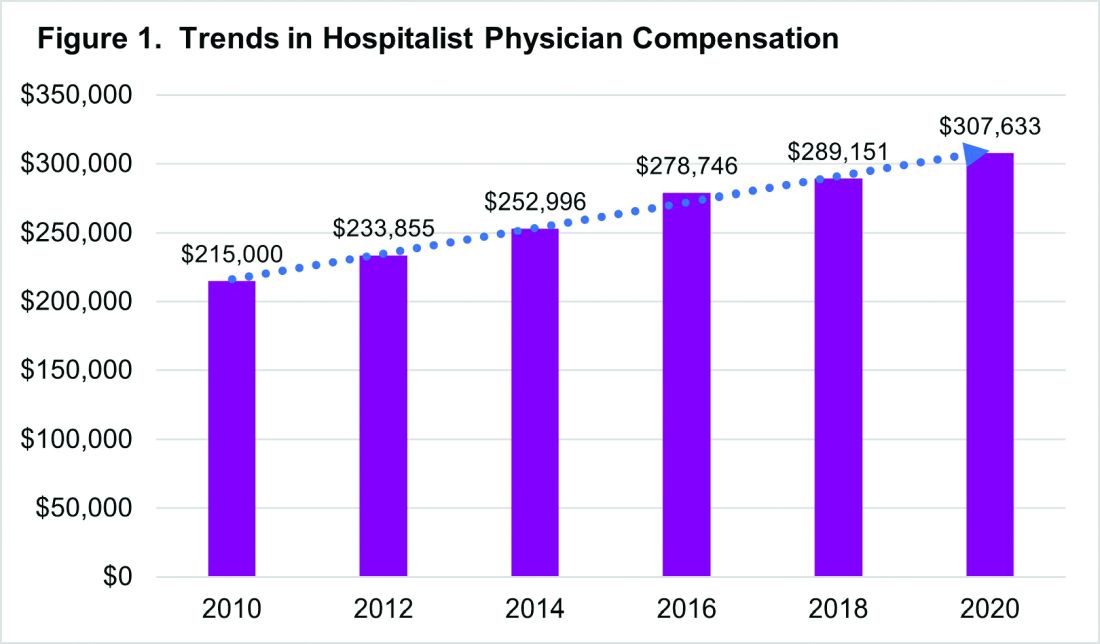

In 2020, the median total compensation nationally for adult hospitalists (internal medicine and family medicine) was $307,633, representing an increase of over 6% from the 2018 Survey (see Figure 1).

With significant regional variability in compensation across the country, hospitalists in the South continue to earn more than their colleagues in the East – a median compensation difference of about $33,000. However, absolute wage comparisons can be misleading without also considering regional variations in productivity as well.

Reviewing compensation per work relative value unit (wRVU) and per encounter offer additional insight for a more comprehensive assessment. When comparing regional compensation per wRVU, the 2020 Survey continues to show a trend toward hospitalists in the Midwest and West earning more per wRVU than their colleagues in other parts of the country ($78.13 per RVU in the Midwest, $78.95 per RVU in the West). More striking is how hospital medicine groups (HMGs) in the South garner lower compensation per RVU ($57.77) than those in the East ($67.54), even though their total compensation was much higher. This could reflect the gradual decline in compensation per wRVU that’s observed at higher productivity levels. While it’s typical for compensation to increase as productivity does, the rate of increase is generally to a lesser degree.

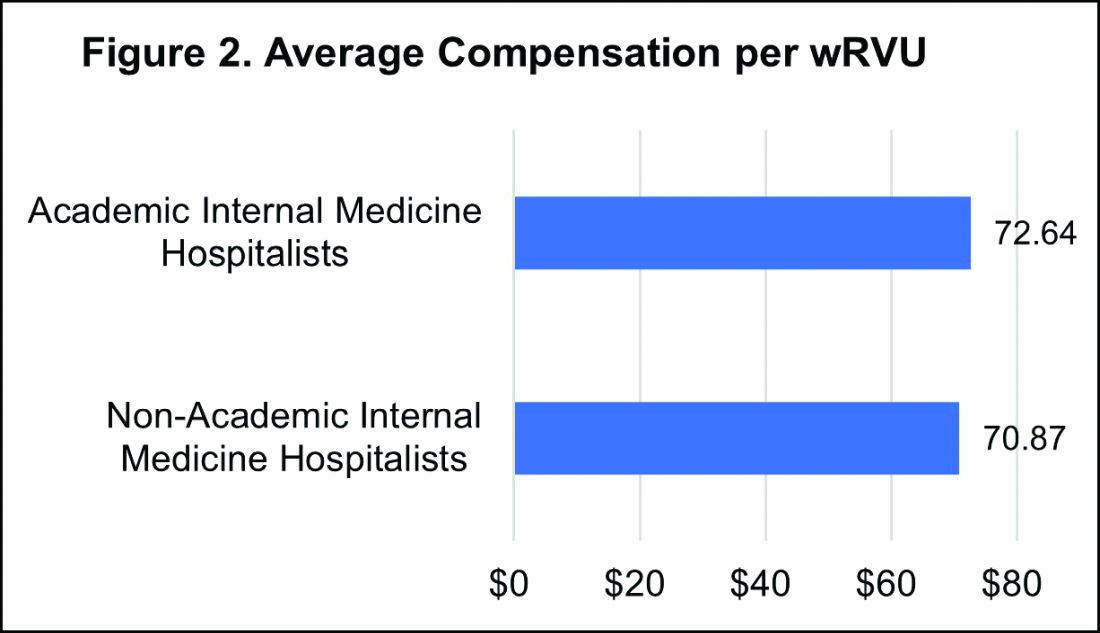

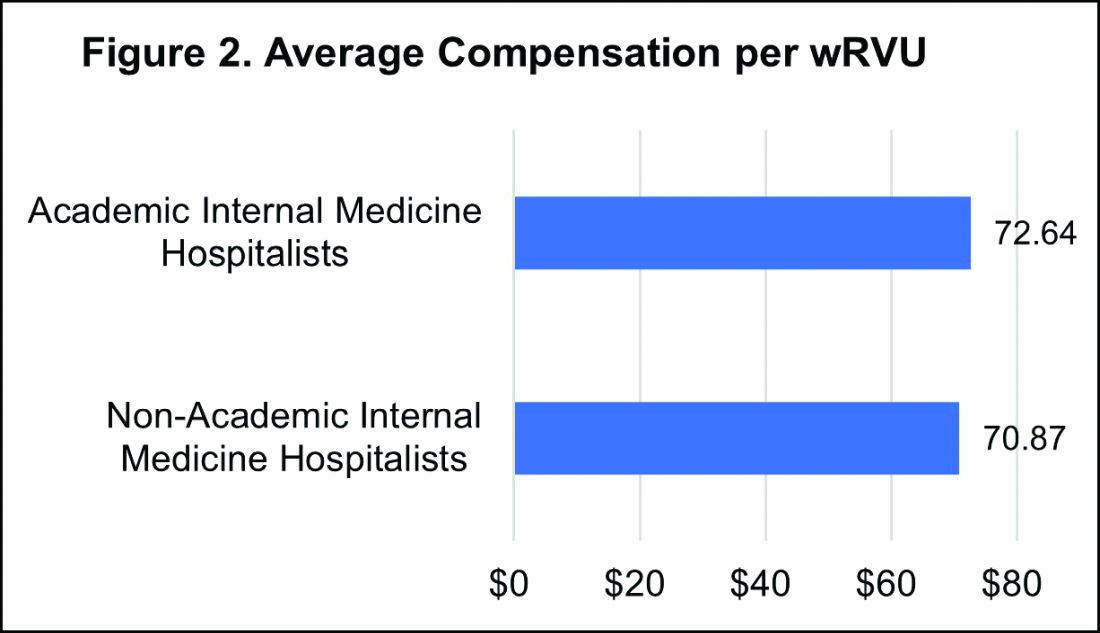

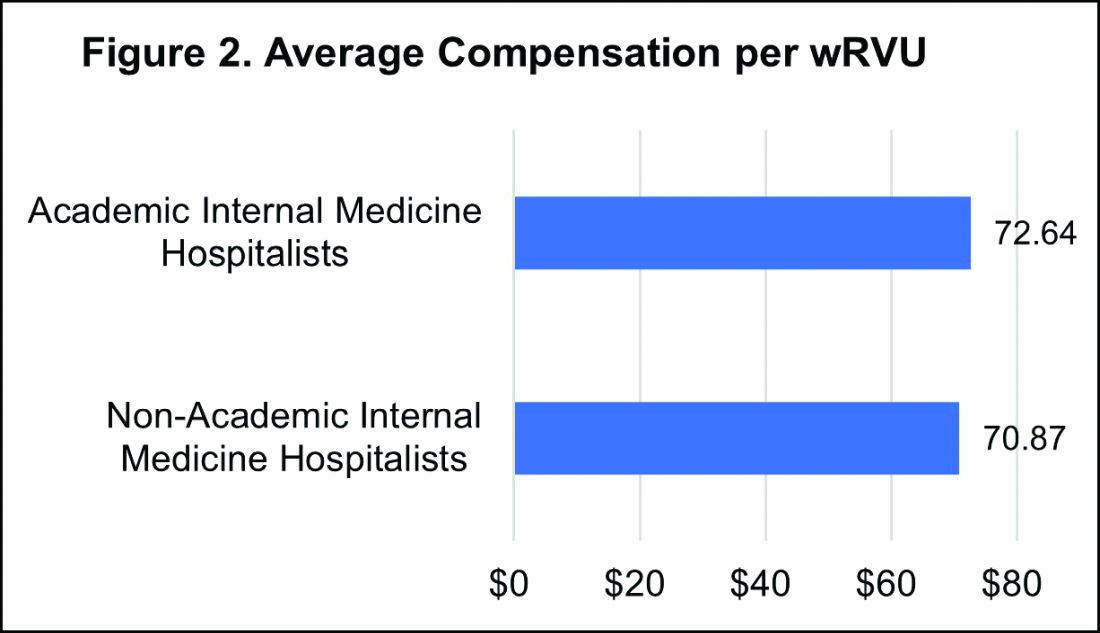

Like past SoHM Surveys, the 2020 Report revealed that academic and non-academic hospitalists are compensated similarly per wRVU (see Figure 2).

However, the total compensation continues to be lower for academic hospitalists, with a median compensation difference of approximately $70,000 compared to their non-academic colleagues. Some of this sizable variance is offset by the fact that academic HMGs receive more in employee benefits packages than non-academic groups – a difference in median value of $10,500. Ideally, academic hospitalist compensation models should appropriately reflect and value their work efforts toward the tripartite academic mission of clinical care, education, and research. It would be valuable for future surveys to define and measure academic production in order to develop national standards for compensation models that recognize these non-billable forms of productivity.

While it’s important to review compensation benchmarks to remain competitive, it’s difficult to put a price on some factors that many may consider more valuable – group culture, opportunities for professional growth, and schedules that afford better work-life integration. Indirect measures of such benefits include paid time off, paid sick days, CME allowances and time, and retirement benefits programs. In 2020, the median employer contribution to retirement plans was reported to be $13,955, with respondents in the Midwest receiving the highest retirement benefit of $33,771.

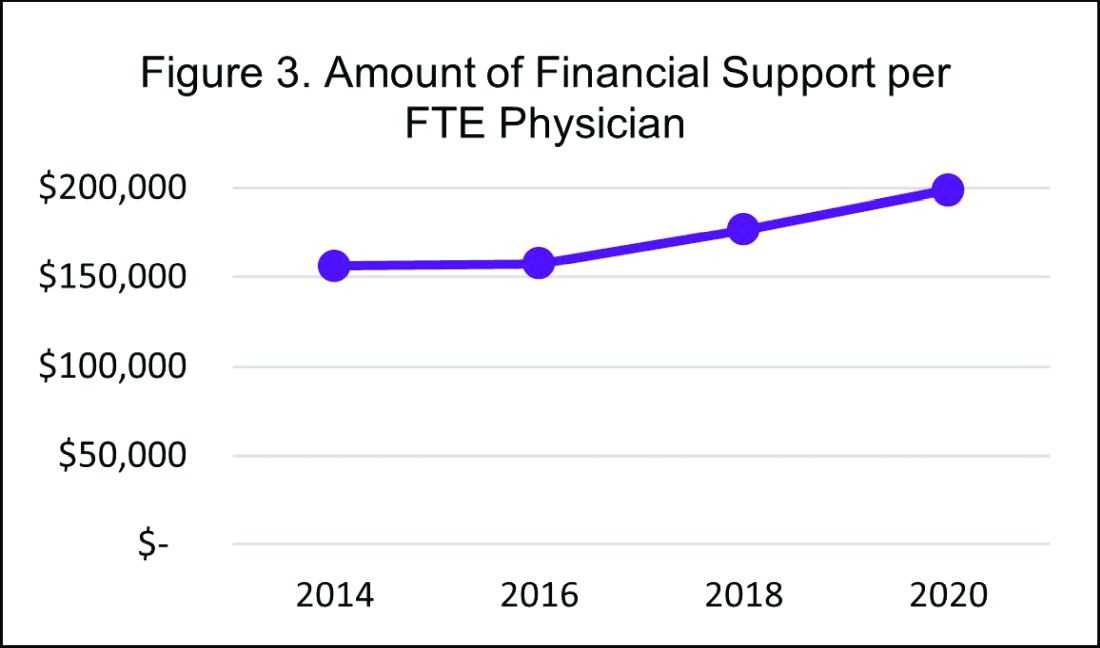

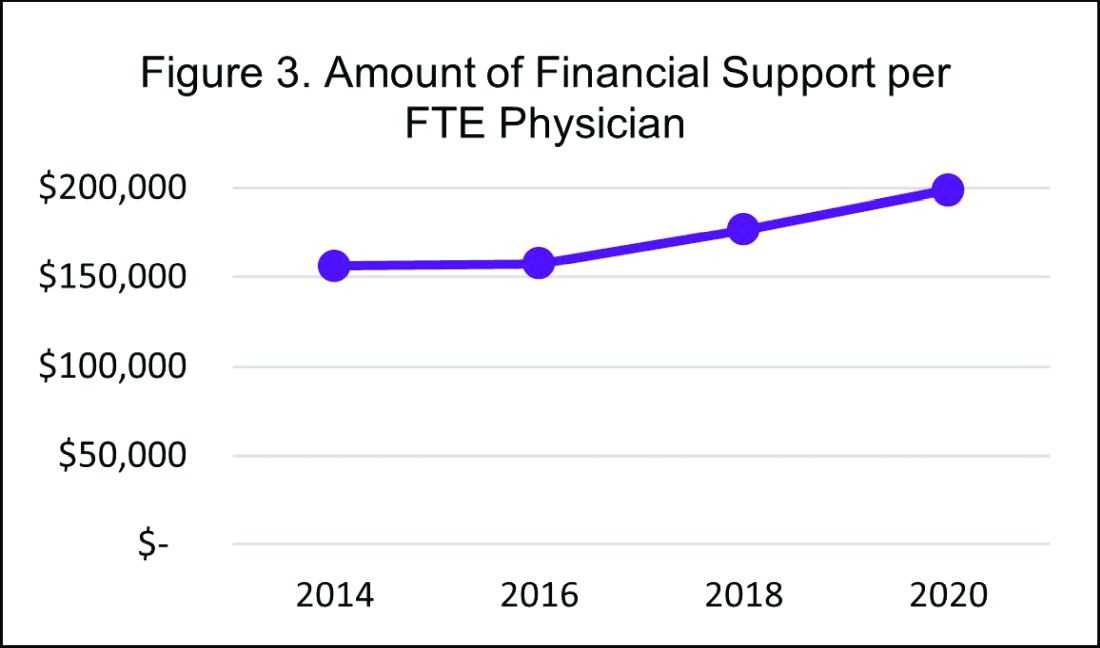

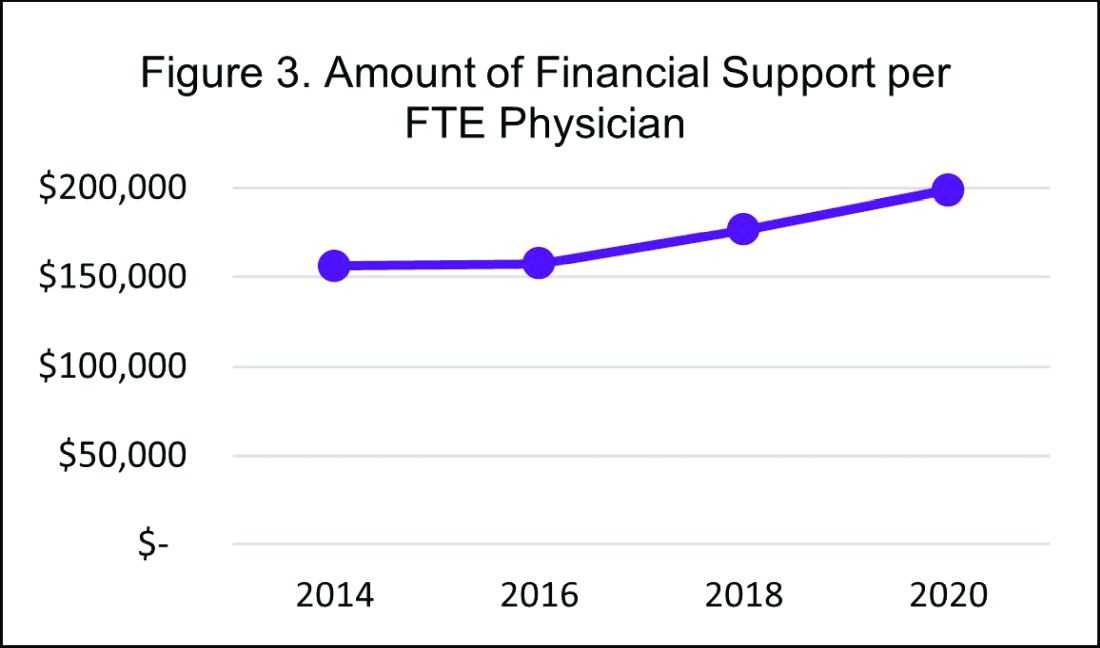

It’s encouraging to see that hospitalist compensation continues to rise compared to previous years, despite relatively flat trends in wRVUs and total patient encounters. Another continued trend over the past years is the rising amount of financial support per physician that hospitals or other organizations provide HMGs (see Figure 3).

In 2020, the median financial support per FTE (full time equivalent) physician serving adult patients increased by 12% over 2018, to $198,750. Collectively these trends indicate hospitals are willing to compensate hospitalists for more than just their clinical volume.

There’s no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic had some financial impact on hospital medicine groups in 2020. To assess this impact, SHM conducted a follow-up survey and compiled a COVID-19 Addendum to the SoHM Report. While 20.5% of HMG group respondents from the East reported providing hazard pay to clinicians caring for COVID-19 patients, nationally only 9.8% of groups said they offered this benefit. Of the 121 HMGs responding from across the country, 42% reported reductions in compensation, which included measures such as reductions in pay level and elimination or delays to bonus payments. The degree of reductions was not quantified, but fortunately the vast majority of these groups reported that these changes were likely to be temporary. To access all data in the 2020 SoHM Report and COVID-19 Addendum, visit hospitalmedicine.org/sohm to purchase your copy.

It’s certainly unclear what the future holds, but despite any transient changes observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, I believe that historical trends in hospitalist compensation will continue. If 2020 has taught us anything, it’s that hospitalists are essential, not only during an acute care crisis but for daily operations of any hospital.

Dr. Kurian is chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Northwell Health in New York. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In a time of tremendous uncertainty, there is one trend that seems consistent year over year – the undisputed value of hospitalists. In the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report, the Society of Hospital Medicine partnered with the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) to provide data on hospitalist compensation and productivity. The Report provides resounding evidence that hospitalists continue to be compensated at rising rates. This may be driven by both the continued demand-supply mismatch and a recognition of the overall value they generate rather than strictly the volume of their productivity.

In 2020, the median total compensation nationally for adult hospitalists (internal medicine and family medicine) was $307,633, representing an increase of over 6% from the 2018 Survey (see Figure 1).

With significant regional variability in compensation across the country, hospitalists in the South continue to earn more than their colleagues in the East – a median compensation difference of about $33,000. However, absolute wage comparisons can be misleading without also considering regional variations in productivity as well.

Reviewing compensation per work relative value unit (wRVU) and per encounter offer additional insight for a more comprehensive assessment. When comparing regional compensation per wRVU, the 2020 Survey continues to show a trend toward hospitalists in the Midwest and West earning more per wRVU than their colleagues in other parts of the country ($78.13 per RVU in the Midwest, $78.95 per RVU in the West). More striking is how hospital medicine groups (HMGs) in the South garner lower compensation per RVU ($57.77) than those in the East ($67.54), even though their total compensation was much higher. This could reflect the gradual decline in compensation per wRVU that’s observed at higher productivity levels. While it’s typical for compensation to increase as productivity does, the rate of increase is generally to a lesser degree.

Like past SoHM Surveys, the 2020 Report revealed that academic and non-academic hospitalists are compensated similarly per wRVU (see Figure 2).

However, the total compensation continues to be lower for academic hospitalists, with a median compensation difference of approximately $70,000 compared to their non-academic colleagues. Some of this sizable variance is offset by the fact that academic HMGs receive more in employee benefits packages than non-academic groups – a difference in median value of $10,500. Ideally, academic hospitalist compensation models should appropriately reflect and value their work efforts toward the tripartite academic mission of clinical care, education, and research. It would be valuable for future surveys to define and measure academic production in order to develop national standards for compensation models that recognize these non-billable forms of productivity.