User login

Should breast cancer screening start at a younger age?

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently issued draft recommendations on breast cancer screening that lower the starting age for routine mammography screening for those at average risk.1 The proposed recommendations are an update to USPSTF’s 2016 guidance on this topic.

What’s different. There are 2 major differences in the new recommendations:

- Recommendation for routine mammography starting at age 40 for women at average risk for breast cancer (eg, no personal or family history or genetic risk factors). This is a “B” recommendation (offer or provide the service). Previously, the recommended age to start routine mammography was 50 years, with a “C” recommendation (individual decision-making) for those ages 40 to 49 years.

- No mention of digital tomosynthesis. Previously, this screening modality was rated as an “I” (insufficient evidence to assess). While the new draft recommendation does not mention tomosynthesis, the related evidence report concludes that there is still insufficient evidence to assess it.2

What’s the same. Several important recommendations have not changed. The USPSTF continues to state that the evidence is insufficient to assess the value of (1) supplemental screening with breast ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in women with dense breasts and negative mammograms and (2) mammography in women ages 75 years and older.

And, most importantly, the USPSTF continues to recommend biennial, rather than annual, mammography screening. This recommendation is based on studies that show very little difference in outcomes between these strategies but higher rates of false-positive tests and subsequent biopsies with annual testing.2

What others say. USPSTF’s draft recommendations continue to differ from those of the American Cancer Society, which for average-risk women recommend individual decision-making from ages 40 to 45 years; routine annual mammography for those ages 45 to 54 years; annual or biennial mammography for those ages 55 years and older; and continued screening for women older than 75 years who are in good health and have a life expectancy ≥ 10 years.3

The USPSTF’s rationale for lowering the age at which to start routine mammography is a little puzzling. Several conclusions in the draft evidence report seem to contradict this recommendation:

In the summary of screening effectiveness, the report states “For women ages 39 to 49 years, the combined [relative risk] for breast cancer mortality was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.75 to 1.02; 9 trials); absolute breast cancer mortality reduction was 2.9 (95% CI, –0.6 to 8.9) deaths prevented per 10,000 women over 10 years. None of the trials indicated statistically significantly reduced breast cancer mortality with screening….”2

And in a summary of screening harms, it states that for “every case of invasive breast cancer detected by mammography screening in women age[s] 40 to 49 years, 464 women had screening mammography, 58 were recommended for additional diagnostic imaging, and 10 were recommended for biopsies.”2

The USPSTF apparently based its decision on a modeling study conducted by the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) at USPSTF’s request. This analysis found that screening biennially from ages 50 to 74 years resulted in about 7 breast cancer deaths averted over the lifetimes of 1000 females and that 1 additional death was averted if the starting age for screening was 40 years.4

Financial implications. The USPSTF’s change from a “C” to a “B” recommendation for women ages 40 to 49 years has financial implications. The Affordable Care Act mandates that all “A” and “B” recommendations by the USPSTF have to be provided by commercial health plans with no out-of-pocket costs. (This is currently being challenged in the courts.) However, any follow-up testing for abnormal results is not subject to this provision—so false-positive work-ups and biopsies may result in out-of-pocket costs.

What to discuss with your patients. For women ages 40 to 50 years, discuss the differences in mammography recommendations and the potential risks and benefits of the procedure, as well as financial implications; respect the patient’s decision.

For those ages 50 to 74 years, recommend biennial mammography.

For those older than 74 years, assess life expectancy and other health problems. Discuss the potential risks and benefits of the procedure and respect the patient’s decision.

For all patients, document all discussions and decisions.

1. USPSTF. Breast cancer: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/breast-cancer-screening-adults

2. Henderson JT, Webber, EM, Weyrich M, et al. Screening for breast cancer: a comparative effectiveness review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 231. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2023. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/breast-cancer-screening-adults

3. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society recommendations for the early detection of breast cancer. Revised January 14, 2022. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/american-cancer-society-recommendations-for-the-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html

4. Trentham Dietz A, Chapman CH, Jayasekera J, et al. Breast cancer screening with mammography: an updated decision analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Technical report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2023. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-modeling-report/breast-cancer-screening-adults

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently issued draft recommendations on breast cancer screening that lower the starting age for routine mammography screening for those at average risk.1 The proposed recommendations are an update to USPSTF’s 2016 guidance on this topic.

What’s different. There are 2 major differences in the new recommendations:

- Recommendation for routine mammography starting at age 40 for women at average risk for breast cancer (eg, no personal or family history or genetic risk factors). This is a “B” recommendation (offer or provide the service). Previously, the recommended age to start routine mammography was 50 years, with a “C” recommendation (individual decision-making) for those ages 40 to 49 years.

- No mention of digital tomosynthesis. Previously, this screening modality was rated as an “I” (insufficient evidence to assess). While the new draft recommendation does not mention tomosynthesis, the related evidence report concludes that there is still insufficient evidence to assess it.2

What’s the same. Several important recommendations have not changed. The USPSTF continues to state that the evidence is insufficient to assess the value of (1) supplemental screening with breast ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in women with dense breasts and negative mammograms and (2) mammography in women ages 75 years and older.

And, most importantly, the USPSTF continues to recommend biennial, rather than annual, mammography screening. This recommendation is based on studies that show very little difference in outcomes between these strategies but higher rates of false-positive tests and subsequent biopsies with annual testing.2

What others say. USPSTF’s draft recommendations continue to differ from those of the American Cancer Society, which for average-risk women recommend individual decision-making from ages 40 to 45 years; routine annual mammography for those ages 45 to 54 years; annual or biennial mammography for those ages 55 years and older; and continued screening for women older than 75 years who are in good health and have a life expectancy ≥ 10 years.3

The USPSTF’s rationale for lowering the age at which to start routine mammography is a little puzzling. Several conclusions in the draft evidence report seem to contradict this recommendation:

In the summary of screening effectiveness, the report states “For women ages 39 to 49 years, the combined [relative risk] for breast cancer mortality was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.75 to 1.02; 9 trials); absolute breast cancer mortality reduction was 2.9 (95% CI, –0.6 to 8.9) deaths prevented per 10,000 women over 10 years. None of the trials indicated statistically significantly reduced breast cancer mortality with screening….”2

And in a summary of screening harms, it states that for “every case of invasive breast cancer detected by mammography screening in women age[s] 40 to 49 years, 464 women had screening mammography, 58 were recommended for additional diagnostic imaging, and 10 were recommended for biopsies.”2

The USPSTF apparently based its decision on a modeling study conducted by the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) at USPSTF’s request. This analysis found that screening biennially from ages 50 to 74 years resulted in about 7 breast cancer deaths averted over the lifetimes of 1000 females and that 1 additional death was averted if the starting age for screening was 40 years.4

Financial implications. The USPSTF’s change from a “C” to a “B” recommendation for women ages 40 to 49 years has financial implications. The Affordable Care Act mandates that all “A” and “B” recommendations by the USPSTF have to be provided by commercial health plans with no out-of-pocket costs. (This is currently being challenged in the courts.) However, any follow-up testing for abnormal results is not subject to this provision—so false-positive work-ups and biopsies may result in out-of-pocket costs.

What to discuss with your patients. For women ages 40 to 50 years, discuss the differences in mammography recommendations and the potential risks and benefits of the procedure, as well as financial implications; respect the patient’s decision.

For those ages 50 to 74 years, recommend biennial mammography.

For those older than 74 years, assess life expectancy and other health problems. Discuss the potential risks and benefits of the procedure and respect the patient’s decision.

For all patients, document all discussions and decisions.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently issued draft recommendations on breast cancer screening that lower the starting age for routine mammography screening for those at average risk.1 The proposed recommendations are an update to USPSTF’s 2016 guidance on this topic.

What’s different. There are 2 major differences in the new recommendations:

- Recommendation for routine mammography starting at age 40 for women at average risk for breast cancer (eg, no personal or family history or genetic risk factors). This is a “B” recommendation (offer or provide the service). Previously, the recommended age to start routine mammography was 50 years, with a “C” recommendation (individual decision-making) for those ages 40 to 49 years.

- No mention of digital tomosynthesis. Previously, this screening modality was rated as an “I” (insufficient evidence to assess). While the new draft recommendation does not mention tomosynthesis, the related evidence report concludes that there is still insufficient evidence to assess it.2

What’s the same. Several important recommendations have not changed. The USPSTF continues to state that the evidence is insufficient to assess the value of (1) supplemental screening with breast ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in women with dense breasts and negative mammograms and (2) mammography in women ages 75 years and older.

And, most importantly, the USPSTF continues to recommend biennial, rather than annual, mammography screening. This recommendation is based on studies that show very little difference in outcomes between these strategies but higher rates of false-positive tests and subsequent biopsies with annual testing.2

What others say. USPSTF’s draft recommendations continue to differ from those of the American Cancer Society, which for average-risk women recommend individual decision-making from ages 40 to 45 years; routine annual mammography for those ages 45 to 54 years; annual or biennial mammography for those ages 55 years and older; and continued screening for women older than 75 years who are in good health and have a life expectancy ≥ 10 years.3

The USPSTF’s rationale for lowering the age at which to start routine mammography is a little puzzling. Several conclusions in the draft evidence report seem to contradict this recommendation:

In the summary of screening effectiveness, the report states “For women ages 39 to 49 years, the combined [relative risk] for breast cancer mortality was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.75 to 1.02; 9 trials); absolute breast cancer mortality reduction was 2.9 (95% CI, –0.6 to 8.9) deaths prevented per 10,000 women over 10 years. None of the trials indicated statistically significantly reduced breast cancer mortality with screening….”2

And in a summary of screening harms, it states that for “every case of invasive breast cancer detected by mammography screening in women age[s] 40 to 49 years, 464 women had screening mammography, 58 were recommended for additional diagnostic imaging, and 10 were recommended for biopsies.”2

The USPSTF apparently based its decision on a modeling study conducted by the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) at USPSTF’s request. This analysis found that screening biennially from ages 50 to 74 years resulted in about 7 breast cancer deaths averted over the lifetimes of 1000 females and that 1 additional death was averted if the starting age for screening was 40 years.4

Financial implications. The USPSTF’s change from a “C” to a “B” recommendation for women ages 40 to 49 years has financial implications. The Affordable Care Act mandates that all “A” and “B” recommendations by the USPSTF have to be provided by commercial health plans with no out-of-pocket costs. (This is currently being challenged in the courts.) However, any follow-up testing for abnormal results is not subject to this provision—so false-positive work-ups and biopsies may result in out-of-pocket costs.

What to discuss with your patients. For women ages 40 to 50 years, discuss the differences in mammography recommendations and the potential risks and benefits of the procedure, as well as financial implications; respect the patient’s decision.

For those ages 50 to 74 years, recommend biennial mammography.

For those older than 74 years, assess life expectancy and other health problems. Discuss the potential risks and benefits of the procedure and respect the patient’s decision.

For all patients, document all discussions and decisions.

1. USPSTF. Breast cancer: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/breast-cancer-screening-adults

2. Henderson JT, Webber, EM, Weyrich M, et al. Screening for breast cancer: a comparative effectiveness review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 231. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2023. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/breast-cancer-screening-adults

3. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society recommendations for the early detection of breast cancer. Revised January 14, 2022. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/american-cancer-society-recommendations-for-the-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html

4. Trentham Dietz A, Chapman CH, Jayasekera J, et al. Breast cancer screening with mammography: an updated decision analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Technical report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2023. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-modeling-report/breast-cancer-screening-adults

1. USPSTF. Breast cancer: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/breast-cancer-screening-adults

2. Henderson JT, Webber, EM, Weyrich M, et al. Screening for breast cancer: a comparative effectiveness review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 231. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2023. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/breast-cancer-screening-adults

3. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society recommendations for the early detection of breast cancer. Revised January 14, 2022. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/american-cancer-society-recommendations-for-the-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html

4. Trentham Dietz A, Chapman CH, Jayasekera J, et al. Breast cancer screening with mammography: an updated decision analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Technical report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2023. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-modeling-report/breast-cancer-screening-adults

Talking tobacco with youth? Ask the right questions

There is good news and bad news regarding the use of tobacco products by young people in the United States, according to the recently released findings from the 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).1 The use of cigarettes among high school students declined from 36.4% in 1997 to 6.0% in 2019.2 However, young people have replaced cigarettes with other tobacco products, including electronic vapor products (EVPs). So we need to ask specifically about these products.

Known by many names. EVPs are referred to as e-cigarettes, vapes, hookah pens, and mods. They usually contain nicotine, which is highly addictive, can affect brain development, and may lead to smoking of cigarettes.3 The most common reasons young people say they use EVPs are feelings of anxiety, stress, and depression, as well as the “high” associated with nicotine use.4

Use of EVPs among youth. The YRBS, which includes a representative sample of public and private school students in grades 9 to 12 in the 50 states, categorizes the use of EVPs as

- ever use

- current use (≥ 1 use during the 30 days before the survey), and

- daily use (during the 30 days before the survey).

In 2021, 36.2% of young people reported ever use of EVPs (40.9% of females; 32.1% of males), 18% reported current use (21.4% of females; 14.9% of males), and 5% reported daily use (5.6% of females; 4.5% of males). Differences between racial and ethnic groups were minor, except for markedly lower rates in Asian youth (19.5% ever use, 5.5% current use, and 1.2% daily use).5

Current recommendations. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends education and brief counseling for school-age children and adolescents to prevent them from starting to use tobacco (including use of EVPs).6 The USPSTF also recommends tobacco cessation using behavioral interventions and/or pharmacotherapy for those ages 18 years and older.7

The USPSTF makes no recommendation on cessation for those younger than 18 years, citing weak evidence. However, it would be reasonable to offer behavioral interventions to younger current users. (Pharmacotherapy is not approved for use in children and adolescents.)

The take-home message. When we ask children and adolescents about use of tobacco products, we need to specifically mention EVPs and advise against their use.

1. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(suppl 1):1-93. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/su/pdfs/su7201-h.pdf

2. Creamer MR, Everett Jones S, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(suppl 1):56-63. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a7

3. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/24952/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes

4. Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2022;71(no. SS-5):1-29. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7105a1

5. Oliver BE, Jones SE, Hops ED, et al. Electronic vapor product use among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(suppl 1):93-99. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7201a11

6. USPSTF. Tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Final recommendation statement. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

7. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Final recommendation statement. Published January 19, 2021. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

There is good news and bad news regarding the use of tobacco products by young people in the United States, according to the recently released findings from the 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).1 The use of cigarettes among high school students declined from 36.4% in 1997 to 6.0% in 2019.2 However, young people have replaced cigarettes with other tobacco products, including electronic vapor products (EVPs). So we need to ask specifically about these products.

Known by many names. EVPs are referred to as e-cigarettes, vapes, hookah pens, and mods. They usually contain nicotine, which is highly addictive, can affect brain development, and may lead to smoking of cigarettes.3 The most common reasons young people say they use EVPs are feelings of anxiety, stress, and depression, as well as the “high” associated with nicotine use.4

Use of EVPs among youth. The YRBS, which includes a representative sample of public and private school students in grades 9 to 12 in the 50 states, categorizes the use of EVPs as

- ever use

- current use (≥ 1 use during the 30 days before the survey), and

- daily use (during the 30 days before the survey).

In 2021, 36.2% of young people reported ever use of EVPs (40.9% of females; 32.1% of males), 18% reported current use (21.4% of females; 14.9% of males), and 5% reported daily use (5.6% of females; 4.5% of males). Differences between racial and ethnic groups were minor, except for markedly lower rates in Asian youth (19.5% ever use, 5.5% current use, and 1.2% daily use).5

Current recommendations. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends education and brief counseling for school-age children and adolescents to prevent them from starting to use tobacco (including use of EVPs).6 The USPSTF also recommends tobacco cessation using behavioral interventions and/or pharmacotherapy for those ages 18 years and older.7

The USPSTF makes no recommendation on cessation for those younger than 18 years, citing weak evidence. However, it would be reasonable to offer behavioral interventions to younger current users. (Pharmacotherapy is not approved for use in children and adolescents.)

The take-home message. When we ask children and adolescents about use of tobacco products, we need to specifically mention EVPs and advise against their use.

There is good news and bad news regarding the use of tobacco products by young people in the United States, according to the recently released findings from the 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).1 The use of cigarettes among high school students declined from 36.4% in 1997 to 6.0% in 2019.2 However, young people have replaced cigarettes with other tobacco products, including electronic vapor products (EVPs). So we need to ask specifically about these products.

Known by many names. EVPs are referred to as e-cigarettes, vapes, hookah pens, and mods. They usually contain nicotine, which is highly addictive, can affect brain development, and may lead to smoking of cigarettes.3 The most common reasons young people say they use EVPs are feelings of anxiety, stress, and depression, as well as the “high” associated with nicotine use.4

Use of EVPs among youth. The YRBS, which includes a representative sample of public and private school students in grades 9 to 12 in the 50 states, categorizes the use of EVPs as

- ever use

- current use (≥ 1 use during the 30 days before the survey), and

- daily use (during the 30 days before the survey).

In 2021, 36.2% of young people reported ever use of EVPs (40.9% of females; 32.1% of males), 18% reported current use (21.4% of females; 14.9% of males), and 5% reported daily use (5.6% of females; 4.5% of males). Differences between racial and ethnic groups were minor, except for markedly lower rates in Asian youth (19.5% ever use, 5.5% current use, and 1.2% daily use).5

Current recommendations. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends education and brief counseling for school-age children and adolescents to prevent them from starting to use tobacco (including use of EVPs).6 The USPSTF also recommends tobacco cessation using behavioral interventions and/or pharmacotherapy for those ages 18 years and older.7

The USPSTF makes no recommendation on cessation for those younger than 18 years, citing weak evidence. However, it would be reasonable to offer behavioral interventions to younger current users. (Pharmacotherapy is not approved for use in children and adolescents.)

The take-home message. When we ask children and adolescents about use of tobacco products, we need to specifically mention EVPs and advise against their use.

1. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(suppl 1):1-93. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/su/pdfs/su7201-h.pdf

2. Creamer MR, Everett Jones S, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(suppl 1):56-63. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a7

3. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/24952/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes

4. Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2022;71(no. SS-5):1-29. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7105a1

5. Oliver BE, Jones SE, Hops ED, et al. Electronic vapor product use among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(suppl 1):93-99. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7201a11

6. USPSTF. Tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Final recommendation statement. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

7. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Final recommendation statement. Published January 19, 2021. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

1. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(suppl 1):1-93. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/su/pdfs/su7201-h.pdf

2. Creamer MR, Everett Jones S, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(suppl 1):56-63. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a7

3. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/24952/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes

4. Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2022;71(no. SS-5):1-29. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7105a1

5. Oliver BE, Jones SE, Hops ED, et al. Electronic vapor product use among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(suppl 1):93-99. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7201a11

6. USPSTF. Tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Final recommendation statement. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

7. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Final recommendation statement. Published January 19, 2021. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

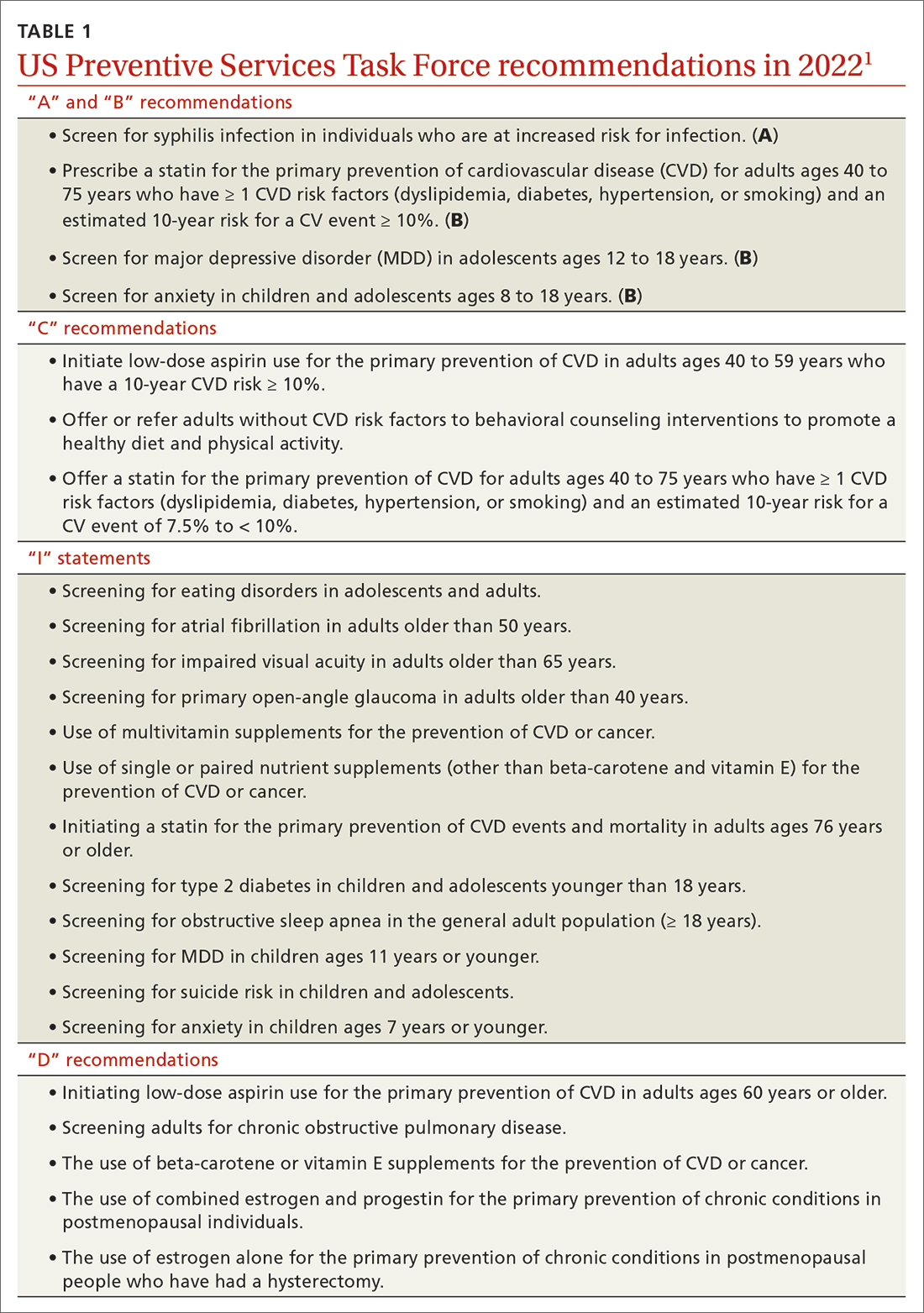

These USPSTF recommendations should be on your radar

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) had a productive year in 2022. In total, the USPSTF

- reviewed and made recommendations on 4 new topics

- re-assessed 19 previous recommendations on 11 topics

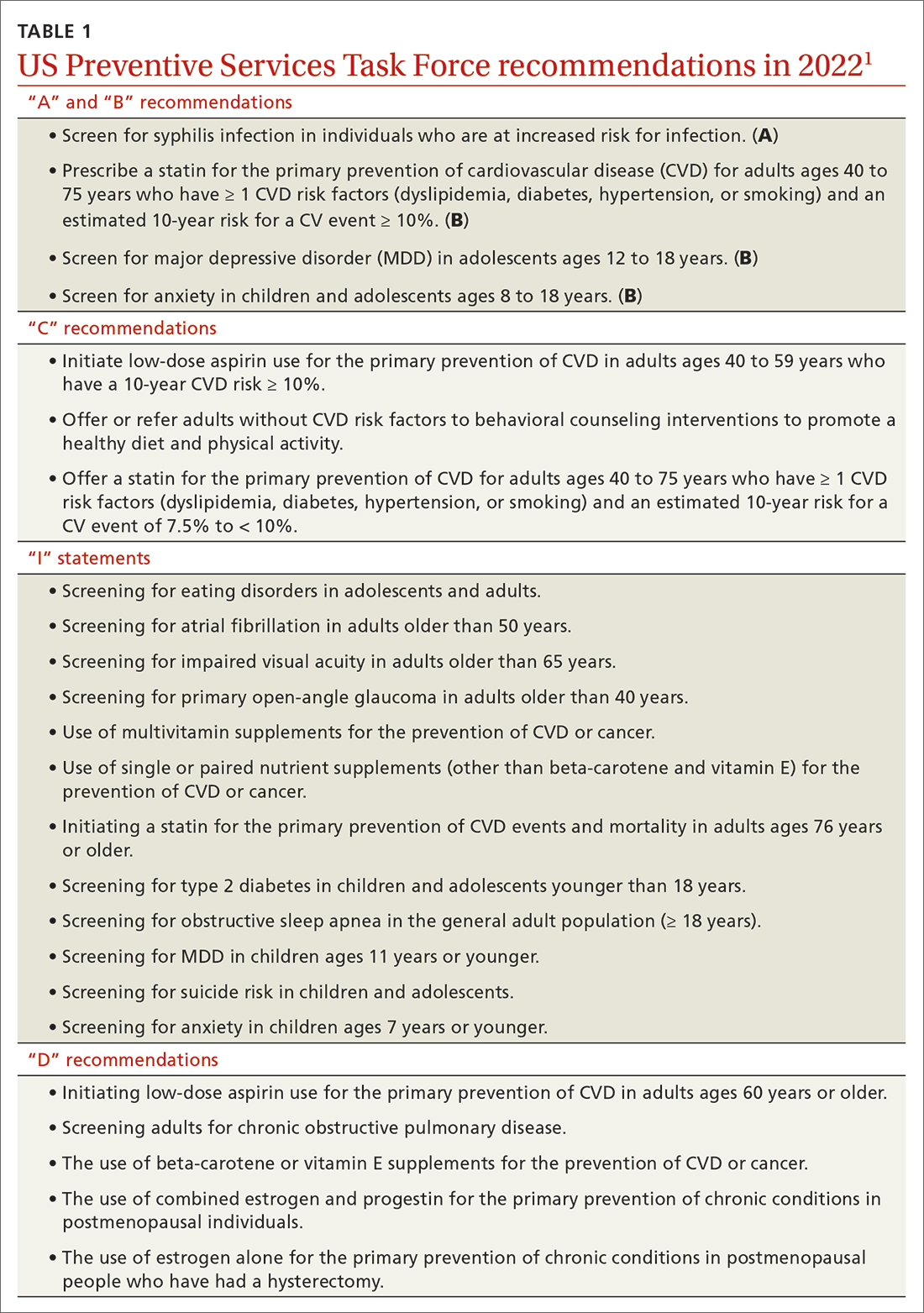

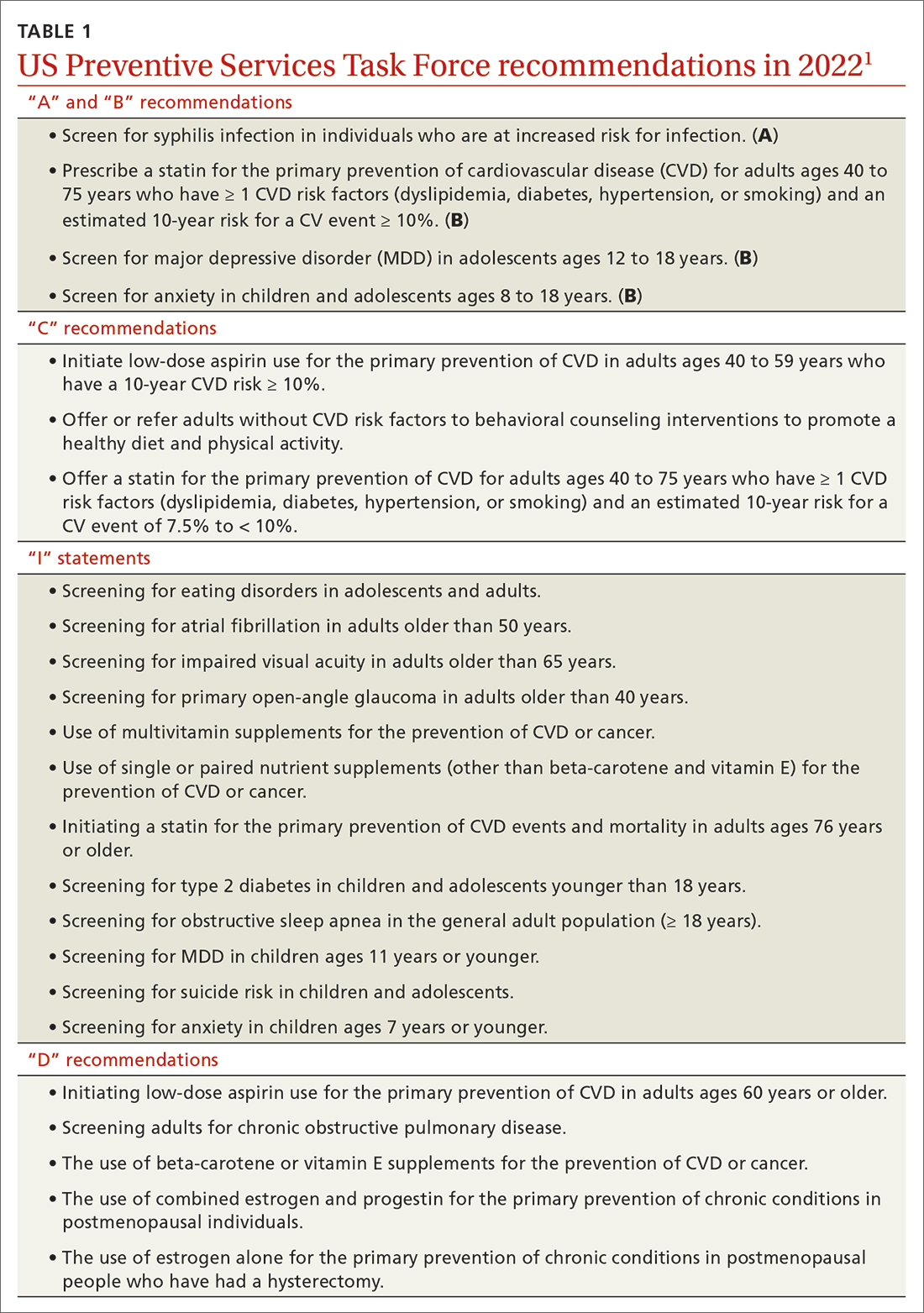

- made 24 separate recommendations, including 1 “A,” 3 “B,” 3 “C,” and 5 “D” recommendations and 12 “I” statements (see TABLE 11).

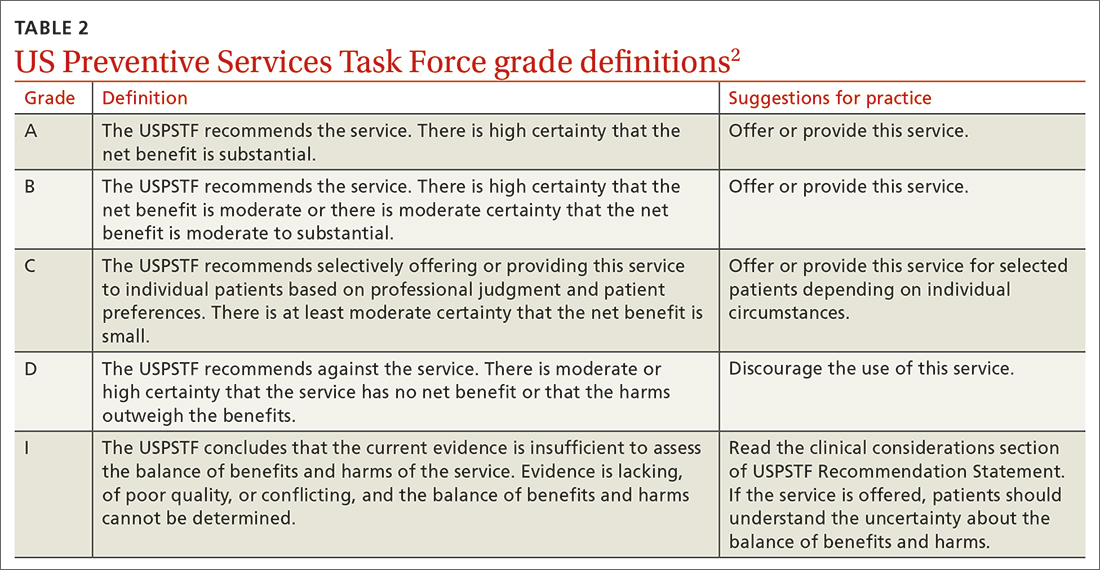

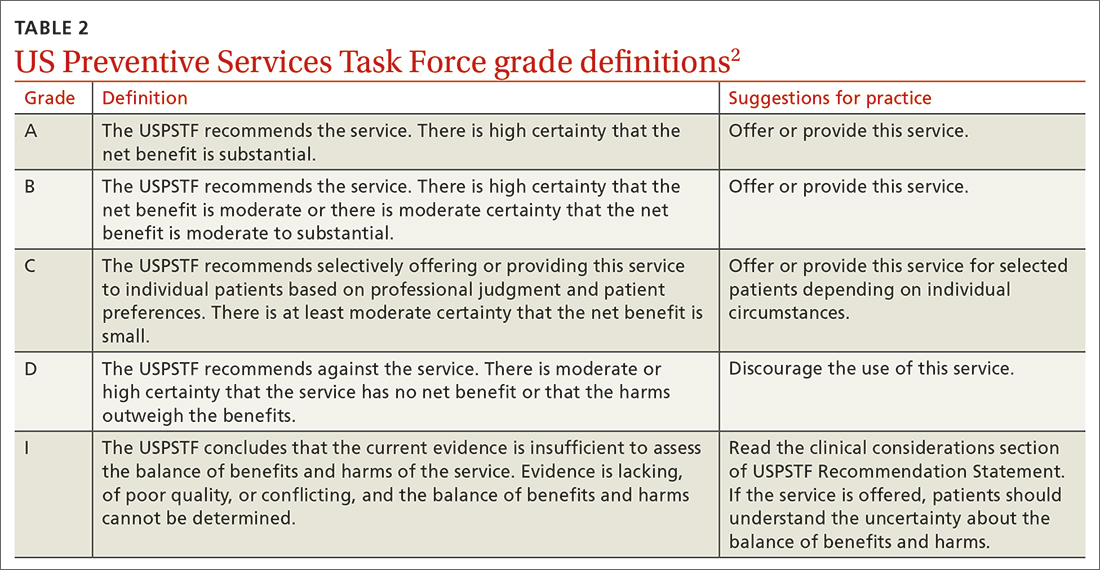

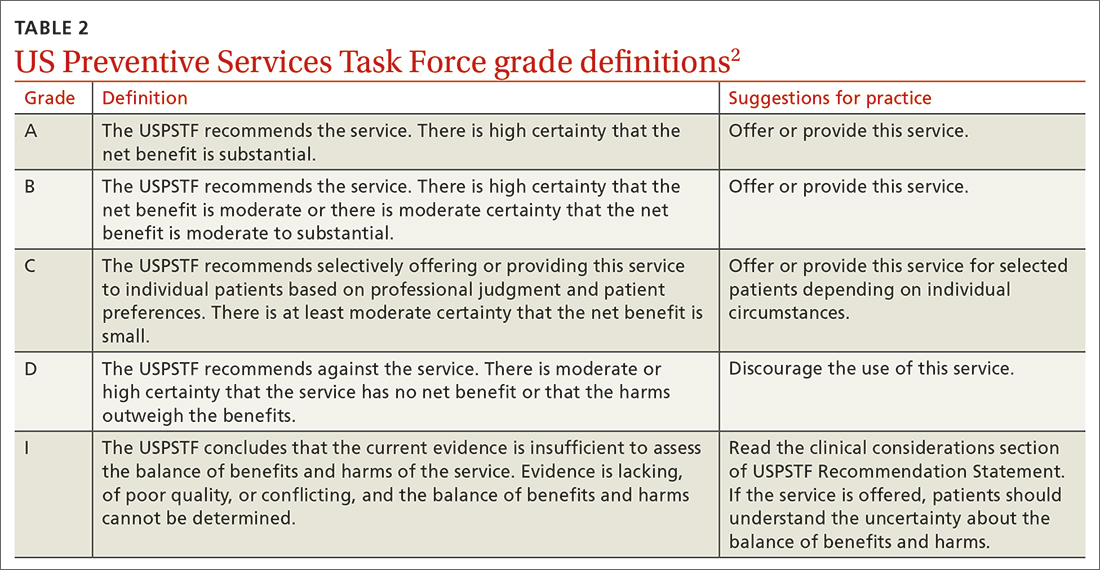

A note about grading. TABLE 22 outlines the USPSTF’s grade definitions and suggestions for practice. The importance of an “A” or “B” recommendation rests historically with the requirement in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that all USPSTF-recommended services with either of these grades have to be provided by commercial health insurance plans with no co-pay or deductible applied. (The legal challenge in Texas to the ACA’s preventive care provision may change that.)

What’s new?

The USPSTF’s review of 4 new topics exceeds the entity’s output in each of the prior 4 years, when the Task Force was able to add only 1 or 2 topics annually. However, 3 of the 4 new topics in 2022 resulted in an insufficient evidence or “I” statement, which means there was not enough evidence to judge the relative benefits and harms of the intervention.

These 3 included screening for type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents younger than 18 years; screening for obstructive sleep apnea in the general adult population (ages ≥ 18 years); and screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults. The fourth new topic, screening for anxiety in children and adolescents, resulted in a “B” recommendation and was described in a recent Practice Alert.3

Major revision to 1 prior recommendation

Only 1 of the 19 revisited recommendations resulted in a major revision: the use of daily aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Note that it does not apply to those who have established CVD, in whom the use of aspirin would be considered tertiary prevention or harm reduction.

In 2016, the USPSTF recommended (with a “B” grade) the use of daily low-dose aspirin for those ages 50 to 59 years who had a 10-year risk for a CVD event > 10%; no increased risk for bleeding; at least a 10-year life expectancy; and a willingness to take aspirin for 10 years. For those ages 60 to 69 years with a 10-year risk for a CVD event > 10%, the recommendation was a “C.” For those younger than 50 and older than 70, an “I” statement was issued.

In 2022, the USPSTF was much less enthusiastic about daily aspirin as a primary preventative.4 The recommendation is now a “C” for those ages 40 to 59 years who have a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 10%. Those most likely to benefit have a 10-year CVD risk > 15%.

Continue to: The recommendation pertains...

The recommendation pertains to the initiation of aspirin, not the continuation or discontinuation for those who have been using aspirin without complications. The USPSTF suggests that the dose of aspirin, if used, should be 81 mg and that it should not be continued past age 75 years. A more detailed discussion of this recommendation and some of its clinical considerations is contained in a recent Practice Alert.5

“D” is for “don’t”(with a few caveats)

Avoiding unnecessary or harmful testing and treatments is just as important as offering preventive services of proven benefit. Those practices listed in TABLE 11 with a “D” recommendation should be avoided in practice.

However, it is worth mentioning that, while postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy should not be prescribed for the prevention of chronic conditions, this does not mean it should not be used to alleviate postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms—albeit for a limited period of time.

Also, it is important to appreciate the difference between screening and diagnostic tests. When the USPSTF recommends for or against screening, they are referring to the practice in asymptomatic people. The recommendation does not pertain to diagnostic testing to confirm or rule out a condition in a person with symptoms suggestive of a condition. Thus, the recommendation against screening adults for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease applies only to those without symptoms.

Be selective with services graded “C” or “I”

The USPSTF recommendations that require the most clinical judgment and are the most difficult to implement are those with a “C.” Few individuals will benefit from these interventions, and those most likely to benefit usually are described in the clinical considerations that accompany the recommendation. These interventions are time consuming and may be subject to insurance co-pays and deductibles. All 3 “C” recommendations made in 2022 (see TABLE 11) pertained to the prevention of CVD, still the leading cause of death in the United States.

Continue it: As "I" statement is not the same...

An “I” statement is not the same as a recommendation against the service—but if the service is offered, both the physician and the patient should understand the uncertainty involved. The services the USPSTF has determined lack sufficient evidence of benefits and/or harms are often recommended by other organizations—and in fact, the use of the “I” statement distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline groups.

If good evidence does not exist, the USPSTF will not make a recommendation. This is the main reason that, when the USPSTF reevaluates a topic (about every 6 to 7 years), they seldom make significant changes to their previous recommendations. Good evidence tends to survive the test of time.

However, adherence to this standard can cause the USPSTF to lag behind other guideline producers for some commonly used interventions. This delay can be considered a detriment if the intervention eventually proves to be effective, but it is a benefit if the intervention proves to be nonbeneficial or even harmful.

Putting recommendations into best practice

Given the time constraints in primary care practice, the most efficient way of providing high-quality, clinical preventive services is by implementing USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations, being very selective about who receives an intervention with a “C” recommendation or “I” statement, and avoiding interventions with a “D” recommendation.

BREAKING NEWS

At press time, the USPSTF issued a draft recommendation statement that women begin receiving biennial mammograms starting at age 40 years (through age 74 years). For more, see: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/breast-cancer-screening-adults#fullrecommendation start

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Grade definitions. Updated October 2018. Accessed April 18, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/about-uspstf/methods-and-processes/grade-definitions

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Whom to screen for anxiety and depression: updated USPSTF recommendations. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:423-425. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0519

4. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: USPSTF recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:1577-1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4983

5. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF updates recommendations on aspirin and CVD. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:262-264. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0452

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) had a productive year in 2022. In total, the USPSTF

- reviewed and made recommendations on 4 new topics

- re-assessed 19 previous recommendations on 11 topics

- made 24 separate recommendations, including 1 “A,” 3 “B,” 3 “C,” and 5 “D” recommendations and 12 “I” statements (see TABLE 11).

A note about grading. TABLE 22 outlines the USPSTF’s grade definitions and suggestions for practice. The importance of an “A” or “B” recommendation rests historically with the requirement in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that all USPSTF-recommended services with either of these grades have to be provided by commercial health insurance plans with no co-pay or deductible applied. (The legal challenge in Texas to the ACA’s preventive care provision may change that.)

What’s new?

The USPSTF’s review of 4 new topics exceeds the entity’s output in each of the prior 4 years, when the Task Force was able to add only 1 or 2 topics annually. However, 3 of the 4 new topics in 2022 resulted in an insufficient evidence or “I” statement, which means there was not enough evidence to judge the relative benefits and harms of the intervention.

These 3 included screening for type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents younger than 18 years; screening for obstructive sleep apnea in the general adult population (ages ≥ 18 years); and screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults. The fourth new topic, screening for anxiety in children and adolescents, resulted in a “B” recommendation and was described in a recent Practice Alert.3

Major revision to 1 prior recommendation

Only 1 of the 19 revisited recommendations resulted in a major revision: the use of daily aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Note that it does not apply to those who have established CVD, in whom the use of aspirin would be considered tertiary prevention or harm reduction.

In 2016, the USPSTF recommended (with a “B” grade) the use of daily low-dose aspirin for those ages 50 to 59 years who had a 10-year risk for a CVD event > 10%; no increased risk for bleeding; at least a 10-year life expectancy; and a willingness to take aspirin for 10 years. For those ages 60 to 69 years with a 10-year risk for a CVD event > 10%, the recommendation was a “C.” For those younger than 50 and older than 70, an “I” statement was issued.

In 2022, the USPSTF was much less enthusiastic about daily aspirin as a primary preventative.4 The recommendation is now a “C” for those ages 40 to 59 years who have a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 10%. Those most likely to benefit have a 10-year CVD risk > 15%.

Continue to: The recommendation pertains...

The recommendation pertains to the initiation of aspirin, not the continuation or discontinuation for those who have been using aspirin without complications. The USPSTF suggests that the dose of aspirin, if used, should be 81 mg and that it should not be continued past age 75 years. A more detailed discussion of this recommendation and some of its clinical considerations is contained in a recent Practice Alert.5

“D” is for “don’t”(with a few caveats)

Avoiding unnecessary or harmful testing and treatments is just as important as offering preventive services of proven benefit. Those practices listed in TABLE 11 with a “D” recommendation should be avoided in practice.

However, it is worth mentioning that, while postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy should not be prescribed for the prevention of chronic conditions, this does not mean it should not be used to alleviate postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms—albeit for a limited period of time.

Also, it is important to appreciate the difference between screening and diagnostic tests. When the USPSTF recommends for or against screening, they are referring to the practice in asymptomatic people. The recommendation does not pertain to diagnostic testing to confirm or rule out a condition in a person with symptoms suggestive of a condition. Thus, the recommendation against screening adults for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease applies only to those without symptoms.

Be selective with services graded “C” or “I”

The USPSTF recommendations that require the most clinical judgment and are the most difficult to implement are those with a “C.” Few individuals will benefit from these interventions, and those most likely to benefit usually are described in the clinical considerations that accompany the recommendation. These interventions are time consuming and may be subject to insurance co-pays and deductibles. All 3 “C” recommendations made in 2022 (see TABLE 11) pertained to the prevention of CVD, still the leading cause of death in the United States.

Continue it: As "I" statement is not the same...

An “I” statement is not the same as a recommendation against the service—but if the service is offered, both the physician and the patient should understand the uncertainty involved. The services the USPSTF has determined lack sufficient evidence of benefits and/or harms are often recommended by other organizations—and in fact, the use of the “I” statement distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline groups.

If good evidence does not exist, the USPSTF will not make a recommendation. This is the main reason that, when the USPSTF reevaluates a topic (about every 6 to 7 years), they seldom make significant changes to their previous recommendations. Good evidence tends to survive the test of time.

However, adherence to this standard can cause the USPSTF to lag behind other guideline producers for some commonly used interventions. This delay can be considered a detriment if the intervention eventually proves to be effective, but it is a benefit if the intervention proves to be nonbeneficial or even harmful.

Putting recommendations into best practice

Given the time constraints in primary care practice, the most efficient way of providing high-quality, clinical preventive services is by implementing USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations, being very selective about who receives an intervention with a “C” recommendation or “I” statement, and avoiding interventions with a “D” recommendation.

BREAKING NEWS

At press time, the USPSTF issued a draft recommendation statement that women begin receiving biennial mammograms starting at age 40 years (through age 74 years). For more, see: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/breast-cancer-screening-adults#fullrecommendation start

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) had a productive year in 2022. In total, the USPSTF

- reviewed and made recommendations on 4 new topics

- re-assessed 19 previous recommendations on 11 topics

- made 24 separate recommendations, including 1 “A,” 3 “B,” 3 “C,” and 5 “D” recommendations and 12 “I” statements (see TABLE 11).

A note about grading. TABLE 22 outlines the USPSTF’s grade definitions and suggestions for practice. The importance of an “A” or “B” recommendation rests historically with the requirement in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that all USPSTF-recommended services with either of these grades have to be provided by commercial health insurance plans with no co-pay or deductible applied. (The legal challenge in Texas to the ACA’s preventive care provision may change that.)

What’s new?

The USPSTF’s review of 4 new topics exceeds the entity’s output in each of the prior 4 years, when the Task Force was able to add only 1 or 2 topics annually. However, 3 of the 4 new topics in 2022 resulted in an insufficient evidence or “I” statement, which means there was not enough evidence to judge the relative benefits and harms of the intervention.

These 3 included screening for type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents younger than 18 years; screening for obstructive sleep apnea in the general adult population (ages ≥ 18 years); and screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults. The fourth new topic, screening for anxiety in children and adolescents, resulted in a “B” recommendation and was described in a recent Practice Alert.3

Major revision to 1 prior recommendation

Only 1 of the 19 revisited recommendations resulted in a major revision: the use of daily aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Note that it does not apply to those who have established CVD, in whom the use of aspirin would be considered tertiary prevention or harm reduction.

In 2016, the USPSTF recommended (with a “B” grade) the use of daily low-dose aspirin for those ages 50 to 59 years who had a 10-year risk for a CVD event > 10%; no increased risk for bleeding; at least a 10-year life expectancy; and a willingness to take aspirin for 10 years. For those ages 60 to 69 years with a 10-year risk for a CVD event > 10%, the recommendation was a “C.” For those younger than 50 and older than 70, an “I” statement was issued.

In 2022, the USPSTF was much less enthusiastic about daily aspirin as a primary preventative.4 The recommendation is now a “C” for those ages 40 to 59 years who have a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 10%. Those most likely to benefit have a 10-year CVD risk > 15%.

Continue to: The recommendation pertains...

The recommendation pertains to the initiation of aspirin, not the continuation or discontinuation for those who have been using aspirin without complications. The USPSTF suggests that the dose of aspirin, if used, should be 81 mg and that it should not be continued past age 75 years. A more detailed discussion of this recommendation and some of its clinical considerations is contained in a recent Practice Alert.5

“D” is for “don’t”(with a few caveats)

Avoiding unnecessary or harmful testing and treatments is just as important as offering preventive services of proven benefit. Those practices listed in TABLE 11 with a “D” recommendation should be avoided in practice.

However, it is worth mentioning that, while postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy should not be prescribed for the prevention of chronic conditions, this does not mean it should not be used to alleviate postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms—albeit for a limited period of time.

Also, it is important to appreciate the difference between screening and diagnostic tests. When the USPSTF recommends for or against screening, they are referring to the practice in asymptomatic people. The recommendation does not pertain to diagnostic testing to confirm or rule out a condition in a person with symptoms suggestive of a condition. Thus, the recommendation against screening adults for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease applies only to those without symptoms.

Be selective with services graded “C” or “I”

The USPSTF recommendations that require the most clinical judgment and are the most difficult to implement are those with a “C.” Few individuals will benefit from these interventions, and those most likely to benefit usually are described in the clinical considerations that accompany the recommendation. These interventions are time consuming and may be subject to insurance co-pays and deductibles. All 3 “C” recommendations made in 2022 (see TABLE 11) pertained to the prevention of CVD, still the leading cause of death in the United States.

Continue it: As "I" statement is not the same...

An “I” statement is not the same as a recommendation against the service—but if the service is offered, both the physician and the patient should understand the uncertainty involved. The services the USPSTF has determined lack sufficient evidence of benefits and/or harms are often recommended by other organizations—and in fact, the use of the “I” statement distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline groups.

If good evidence does not exist, the USPSTF will not make a recommendation. This is the main reason that, when the USPSTF reevaluates a topic (about every 6 to 7 years), they seldom make significant changes to their previous recommendations. Good evidence tends to survive the test of time.

However, adherence to this standard can cause the USPSTF to lag behind other guideline producers for some commonly used interventions. This delay can be considered a detriment if the intervention eventually proves to be effective, but it is a benefit if the intervention proves to be nonbeneficial or even harmful.

Putting recommendations into best practice

Given the time constraints in primary care practice, the most efficient way of providing high-quality, clinical preventive services is by implementing USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations, being very selective about who receives an intervention with a “C” recommendation or “I” statement, and avoiding interventions with a “D” recommendation.

BREAKING NEWS

At press time, the USPSTF issued a draft recommendation statement that women begin receiving biennial mammograms starting at age 40 years (through age 74 years). For more, see: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/breast-cancer-screening-adults#fullrecommendation start

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Grade definitions. Updated October 2018. Accessed April 18, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/about-uspstf/methods-and-processes/grade-definitions

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Whom to screen for anxiety and depression: updated USPSTF recommendations. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:423-425. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0519

4. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: USPSTF recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:1577-1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4983

5. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF updates recommendations on aspirin and CVD. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:262-264. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0452

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 24, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Grade definitions. Updated October 2018. Accessed April 18, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/about-uspstf/methods-and-processes/grade-definitions

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Whom to screen for anxiety and depression: updated USPSTF recommendations. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:423-425. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0519

4. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: USPSTF recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:1577-1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4983

5. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF updates recommendations on aspirin and CVD. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:262-264. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0452

Hepatitis A is on the rise: What FPs can do

In September 2021, a community in Virginia experienced an outbreak of hepatitis A virus (HAV) that was ultimately linked to an infected food handler.1 A total of 149 cases were reported over the next 12 months; 51 were directly related to the food handler and the remainder were the result of sustained community transmission. Of the 51 people who were directly infected by the food handler, 31 were hospitalized and 3 died. This incident offers important reminders about public health surveillance and the role that family physicians can play.

Hepatitis A virus is transmitted through food and drinks that have been contaminated by small amounts of stool that contains the virus or through close contact (including sexual contact) with a person who is infected. The incubation period can range from 15 to 59 days.

HAV generally resolves in a few days to weeks, with no long-term effects. However, recent outbreaks have been associated with high hospitalization and mortality rates because of the underlying comorbidities of those infected.

An increase in incidence. The national rate of HAV infection reached a low of less than 1/100,000 in 2015 but has since increased to almost 6/100,000 in 2019. This increase is mostly due to outbreaks linked to spread among people without a fixed residence, those who use illicit drugs, and men who have sex with men.2

In the Virginia outbreak, the food handler had a risk factor for HAV and was unvaccinated. He worked at 3 different locations of a restaurant chain for a total of 16 days while infectious, preparing ready-to-eat food without using gloves. Furthermore, he delayed seeking medical care for more than 2 weeks—at which time, the nature of his employment was not disclosed.

Prevention is straightforward. HAV infection can be prevented by administration of either HAV vaccine or immune globulin within 2 weeks of exposure.3 During an HAV outbreak, vaccination is recommended for people considered to be at risk, including those without a fixed residence, those who use illicit drugs, those who travel internationally, and men who have sex with men.3

There are 3 HAV vaccines available in the United States: 2 single-antigen vaccines, Havrix and Vaqta, both approved for children and adults, and a combination vaccine (containing both HAV and hepatitis B antigens), Twinrix, which is approved for those ages 18 years and older. All are inactivated vaccines.

What you can do. The Virginia outbreak illustrates the important role that family physicians can and do play in public health. We should:

- Encourage adults with risk factors for HAV to be vaccinated.

- Ask those with an HAV diagnosis about the people they may have exposed through personal contact or occupational exposure.

- Promptly report infectious diseases that are designated “reportable” to the public health department.

- Immediately report (by telephone) when HAV and other enteric infections involve a food handler.

1. Helmick MJ, Morrow CB, White JH, et al. Widespread community transmission of Hepatitis A Virus following an outbreak at a local restaurant—Virginia, September 2021-September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72;362-365. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7214a2

2. CDC. Hepatitis A questions and answers for health professionals. Updated July 28, 2020. Accessed April 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/havfaq.htm

3. Nelson NP, Weng MK, Hofmeister MG, et al. Prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1-38. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6905a1

In September 2021, a community in Virginia experienced an outbreak of hepatitis A virus (HAV) that was ultimately linked to an infected food handler.1 A total of 149 cases were reported over the next 12 months; 51 were directly related to the food handler and the remainder were the result of sustained community transmission. Of the 51 people who were directly infected by the food handler, 31 were hospitalized and 3 died. This incident offers important reminders about public health surveillance and the role that family physicians can play.

Hepatitis A virus is transmitted through food and drinks that have been contaminated by small amounts of stool that contains the virus or through close contact (including sexual contact) with a person who is infected. The incubation period can range from 15 to 59 days.

HAV generally resolves in a few days to weeks, with no long-term effects. However, recent outbreaks have been associated with high hospitalization and mortality rates because of the underlying comorbidities of those infected.

An increase in incidence. The national rate of HAV infection reached a low of less than 1/100,000 in 2015 but has since increased to almost 6/100,000 in 2019. This increase is mostly due to outbreaks linked to spread among people without a fixed residence, those who use illicit drugs, and men who have sex with men.2

In the Virginia outbreak, the food handler had a risk factor for HAV and was unvaccinated. He worked at 3 different locations of a restaurant chain for a total of 16 days while infectious, preparing ready-to-eat food without using gloves. Furthermore, he delayed seeking medical care for more than 2 weeks—at which time, the nature of his employment was not disclosed.

Prevention is straightforward. HAV infection can be prevented by administration of either HAV vaccine or immune globulin within 2 weeks of exposure.3 During an HAV outbreak, vaccination is recommended for people considered to be at risk, including those without a fixed residence, those who use illicit drugs, those who travel internationally, and men who have sex with men.3

There are 3 HAV vaccines available in the United States: 2 single-antigen vaccines, Havrix and Vaqta, both approved for children and adults, and a combination vaccine (containing both HAV and hepatitis B antigens), Twinrix, which is approved for those ages 18 years and older. All are inactivated vaccines.

What you can do. The Virginia outbreak illustrates the important role that family physicians can and do play in public health. We should:

- Encourage adults with risk factors for HAV to be vaccinated.

- Ask those with an HAV diagnosis about the people they may have exposed through personal contact or occupational exposure.

- Promptly report infectious diseases that are designated “reportable” to the public health department.

- Immediately report (by telephone) when HAV and other enteric infections involve a food handler.

In September 2021, a community in Virginia experienced an outbreak of hepatitis A virus (HAV) that was ultimately linked to an infected food handler.1 A total of 149 cases were reported over the next 12 months; 51 were directly related to the food handler and the remainder were the result of sustained community transmission. Of the 51 people who were directly infected by the food handler, 31 were hospitalized and 3 died. This incident offers important reminders about public health surveillance and the role that family physicians can play.

Hepatitis A virus is transmitted through food and drinks that have been contaminated by small amounts of stool that contains the virus or through close contact (including sexual contact) with a person who is infected. The incubation period can range from 15 to 59 days.

HAV generally resolves in a few days to weeks, with no long-term effects. However, recent outbreaks have been associated with high hospitalization and mortality rates because of the underlying comorbidities of those infected.

An increase in incidence. The national rate of HAV infection reached a low of less than 1/100,000 in 2015 but has since increased to almost 6/100,000 in 2019. This increase is mostly due to outbreaks linked to spread among people without a fixed residence, those who use illicit drugs, and men who have sex with men.2

In the Virginia outbreak, the food handler had a risk factor for HAV and was unvaccinated. He worked at 3 different locations of a restaurant chain for a total of 16 days while infectious, preparing ready-to-eat food without using gloves. Furthermore, he delayed seeking medical care for more than 2 weeks—at which time, the nature of his employment was not disclosed.

Prevention is straightforward. HAV infection can be prevented by administration of either HAV vaccine or immune globulin within 2 weeks of exposure.3 During an HAV outbreak, vaccination is recommended for people considered to be at risk, including those without a fixed residence, those who use illicit drugs, those who travel internationally, and men who have sex with men.3

There are 3 HAV vaccines available in the United States: 2 single-antigen vaccines, Havrix and Vaqta, both approved for children and adults, and a combination vaccine (containing both HAV and hepatitis B antigens), Twinrix, which is approved for those ages 18 years and older. All are inactivated vaccines.

What you can do. The Virginia outbreak illustrates the important role that family physicians can and do play in public health. We should:

- Encourage adults with risk factors for HAV to be vaccinated.

- Ask those with an HAV diagnosis about the people they may have exposed through personal contact or occupational exposure.

- Promptly report infectious diseases that are designated “reportable” to the public health department.

- Immediately report (by telephone) when HAV and other enteric infections involve a food handler.

1. Helmick MJ, Morrow CB, White JH, et al. Widespread community transmission of Hepatitis A Virus following an outbreak at a local restaurant—Virginia, September 2021-September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72;362-365. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7214a2

2. CDC. Hepatitis A questions and answers for health professionals. Updated July 28, 2020. Accessed April 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/havfaq.htm

3. Nelson NP, Weng MK, Hofmeister MG, et al. Prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1-38. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6905a1

1. Helmick MJ, Morrow CB, White JH, et al. Widespread community transmission of Hepatitis A Virus following an outbreak at a local restaurant—Virginia, September 2021-September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72;362-365. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7214a2

2. CDC. Hepatitis A questions and answers for health professionals. Updated July 28, 2020. Accessed April 25, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/havfaq.htm

3. Nelson NP, Weng MK, Hofmeister MG, et al. Prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1-38. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6905a1

Folic acid: A recommendation worth making

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently published a draft recommendation on the use of folic acid before and during pregnancy to prevent fetal neural tube defects.1 This reaffirmation of the 2017 recommendation states that all persons planning to or who could become pregnant should take a daily supplement of folic acid.1,2 This is an “A” recommendation.

Neural tube defects are caused by a failure of the embryonic neural tube to close completely, which should occur in the first 28 days following fertilization. This is why folic acid is most effective if started at least 1 month before conception and continued for the first 2 to 3 months of pregnancy.

An estimated 3000 neural tube defects occur each year in the United States. Spina bifida, anencephaly, and encephalocele occur at respective rates of 3.9, 2.5, and 1.0 in 10,000 live births in the United States, which totals 7.4/10,000.3

Folic acid, if taken before and during pregnancy, can prevent about half of neural tube defects; if taken only during pregnancy, it prevents about one-third. If 50% of neural tube defects could be prevented with folic acid supplements, the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent 1 case is about 3000.4

The case for supplementation. The recommended daily dose of folic acid is between 0.4 mg (400 μg) and 0.8 mg (800 μg), which is contained in many multivitamin products. Certain enriched cereal grain products in the United States have been fortified with folic acid for more than 2 decades, but it is unknown whether women in the United States are ingesting enough of these fortified foods to provide maximum prevention of neural tube defects. There are no known harms to mother or fetus from folic acid supplementation at recommended levels.

Room for improvement. Only 20% to 40% of people who are pregnant or trying to get pregnant, and 5% to 10% of people with an unplanned pregnancy, take folic acid supplements. Half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned.4 This leaves a lot of room for improvement in the prevention of neural tube defects.

An important recommendation, even if you don’t see the results. The NNT to prevent a case of neural tube defect is high; most family physicians providing perinatal care will not prevent a case during their career. And, as with most preventive interventions, we do not see the cases prevented. However, on a population-wide basis, if all women took folic acid as recommended, the number of severe birth defects prevented would be significant—making this simple recommendation worth mentioning to those of reproductive age.

1. USPSTF. Folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/sX6CTKHncTJT2nzmu7yLHh

2. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Published January 10, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication

3. Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, et al. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111:1420-1435. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1589

4. Viswanathan M, Urrutia RP, Hudson KN, et al. Folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects: a limited systematic review update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 230. Published February 2023. Accessed March 22, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/AjUYoBvpfUBDAFjHeCcfPz

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently published a draft recommendation on the use of folic acid before and during pregnancy to prevent fetal neural tube defects.1 This reaffirmation of the 2017 recommendation states that all persons planning to or who could become pregnant should take a daily supplement of folic acid.1,2 This is an “A” recommendation.

Neural tube defects are caused by a failure of the embryonic neural tube to close completely, which should occur in the first 28 days following fertilization. This is why folic acid is most effective if started at least 1 month before conception and continued for the first 2 to 3 months of pregnancy.

An estimated 3000 neural tube defects occur each year in the United States. Spina bifida, anencephaly, and encephalocele occur at respective rates of 3.9, 2.5, and 1.0 in 10,000 live births in the United States, which totals 7.4/10,000.3

Folic acid, if taken before and during pregnancy, can prevent about half of neural tube defects; if taken only during pregnancy, it prevents about one-third. If 50% of neural tube defects could be prevented with folic acid supplements, the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent 1 case is about 3000.4

The case for supplementation. The recommended daily dose of folic acid is between 0.4 mg (400 μg) and 0.8 mg (800 μg), which is contained in many multivitamin products. Certain enriched cereal grain products in the United States have been fortified with folic acid for more than 2 decades, but it is unknown whether women in the United States are ingesting enough of these fortified foods to provide maximum prevention of neural tube defects. There are no known harms to mother or fetus from folic acid supplementation at recommended levels.

Room for improvement. Only 20% to 40% of people who are pregnant or trying to get pregnant, and 5% to 10% of people with an unplanned pregnancy, take folic acid supplements. Half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned.4 This leaves a lot of room for improvement in the prevention of neural tube defects.

An important recommendation, even if you don’t see the results. The NNT to prevent a case of neural tube defect is high; most family physicians providing perinatal care will not prevent a case during their career. And, as with most preventive interventions, we do not see the cases prevented. However, on a population-wide basis, if all women took folic acid as recommended, the number of severe birth defects prevented would be significant—making this simple recommendation worth mentioning to those of reproductive age.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently published a draft recommendation on the use of folic acid before and during pregnancy to prevent fetal neural tube defects.1 This reaffirmation of the 2017 recommendation states that all persons planning to or who could become pregnant should take a daily supplement of folic acid.1,2 This is an “A” recommendation.

Neural tube defects are caused by a failure of the embryonic neural tube to close completely, which should occur in the first 28 days following fertilization. This is why folic acid is most effective if started at least 1 month before conception and continued for the first 2 to 3 months of pregnancy.

An estimated 3000 neural tube defects occur each year in the United States. Spina bifida, anencephaly, and encephalocele occur at respective rates of 3.9, 2.5, and 1.0 in 10,000 live births in the United States, which totals 7.4/10,000.3

Folic acid, if taken before and during pregnancy, can prevent about half of neural tube defects; if taken only during pregnancy, it prevents about one-third. If 50% of neural tube defects could be prevented with folic acid supplements, the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent 1 case is about 3000.4

The case for supplementation. The recommended daily dose of folic acid is between 0.4 mg (400 μg) and 0.8 mg (800 μg), which is contained in many multivitamin products. Certain enriched cereal grain products in the United States have been fortified with folic acid for more than 2 decades, but it is unknown whether women in the United States are ingesting enough of these fortified foods to provide maximum prevention of neural tube defects. There are no known harms to mother or fetus from folic acid supplementation at recommended levels.

Room for improvement. Only 20% to 40% of people who are pregnant or trying to get pregnant, and 5% to 10% of people with an unplanned pregnancy, take folic acid supplements. Half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned.4 This leaves a lot of room for improvement in the prevention of neural tube defects.

An important recommendation, even if you don’t see the results. The NNT to prevent a case of neural tube defect is high; most family physicians providing perinatal care will not prevent a case during their career. And, as with most preventive interventions, we do not see the cases prevented. However, on a population-wide basis, if all women took folic acid as recommended, the number of severe birth defects prevented would be significant—making this simple recommendation worth mentioning to those of reproductive age.

1. USPSTF. Folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/sX6CTKHncTJT2nzmu7yLHh

2. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Published January 10, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication

3. Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, et al. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111:1420-1435. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1589

4. Viswanathan M, Urrutia RP, Hudson KN, et al. Folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects: a limited systematic review update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 230. Published February 2023. Accessed March 22, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/AjUYoBvpfUBDAFjHeCcfPz

1. USPSTF. Folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/sX6CTKHncTJT2nzmu7yLHh

2. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Published January 10, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication

3. Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, et al. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111:1420-1435. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1589

4. Viswanathan M, Urrutia RP, Hudson KN, et al. Folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects: a limited systematic review update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 230. Published February 2023. Accessed March 22, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/AjUYoBvpfUBDAFjHeCcfPz

5 non-COVID vaccine recommendations from ACIP

Much of the work of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in 2022 was devoted to vaccines to protect against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); details about the 4 available products can be found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID vaccine website (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/index.html).1,2 However, ACIP also issued recommendations about 5 other (non-COVID) vaccines last year, and those are the focus of this Practice Alert.

A second MMR vaccine option

The United States has had only 1 measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine approved for use since 1978: M-M-R II (Merck). In June 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a second MMR vaccine, PRIORIX (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals), which ACIP now recommends as an option when MMR vaccine is indicated.3

ACIP considers the 2 MMR options fully interchangeable.3 Both vaccines produce similar levels of immunogenicity and the safety profiles are also equivalent—including the rate of febrile seizures 6 to 11 days after vaccination, estimated at 3.3 to 8.7 per 10,000 doses.4 Since PRIORIX has been used in other countries since 1997, the MMR workgroup was able to include 13 studies on immunogenicity and 4 on safety in its evidence assessment; these are summarized on the CDC website.4

It is desirable to have multiple manufacturers of recommended vaccines to prevent shortages if there a disruption in the supply chain of 1 manufacturer, as well as to provide competition for cost control. A second MMR vaccine is therefore a welcome addition to the US vaccine supply. However, there remains only 1 combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine approved for use in the United States: ProQuad (Merck).

Pneumococcal vaccine recommendations are revised and simplified

Adults. Last year, ACIP made recommendations regarding 2 new vaccine options for use against pneumococcal infections in adults: PCV15 (Vaxneuvance, Merck) and PCV20 (Prevnar20, Pfizer). These have been described in detail in a CDC publication and summarized in a recent Practice Alert.5,6

ACIP revised and simplified its recommendations on vaccination to prevent pneumococcal disease in adults as follows5:

1. Maintained the cutoff of age 65 years for universal pneumococcal vaccination

2. Recommended pneumococcal vaccination (with either PCV15 or PCV20) for all adults ages 65 years and older and for those younger than 65 years with chronic medical conditions or immunocompromise

3. Recommended that if PCV15 is used, it should be followed by 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23, Merck).

These revisions created a number of uncertain clinical situations, since patients could have already started and/or completed their pneumococcal vaccination with previously available products, including PCV7, PCV13, and PPSV23. At the October 2022 ACIP meeting, the pneumococcal workgroup addressed a number of “what if” clinical questions. These clinical considerations will soon be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) but also can be reviewed by looking at the October ACIP meeting materials.7 The main considerations are summarized below7:

- For those who have previously received PCV7, either PCV15 or PCV20 should be given.

- If PPSV23 was inadvertently administered first, it should be followed by PCV15 or PCV20 at least 1 year later.

- Adults who have only received PPSV23 should receive a dose of either PCV20 or PCV15 at least 1 year after their last PPSV23 dose. When PCV15 is used in those with a history of PPSV23 receipt, it need not be followed by another dose of PPSV23.

- Adults who have received PCV13 only are recommended to complete their pneumococcal vaccine series by receiving either a dose of PCV20 at least 1 year after the PCV13 dose or PPSV23 as previously recommended.

- Shared clinical decision-making is recommended regarding administration of PCV20 for adults ages ≥ 65 years who have completed their recommended vaccine series with both PCV13 and PPSV23 but have not received PCV15 or PCV20. If a decision to administer PCV20 is made, a dose of PCV20 is recommended at least 5 years after the last pneumococcal vaccine dose.

Continue to: Children

Children. In 2022, PCV15 was licensed for use in children and adolescents ages 6 weeks to 17 years. PCV15 contains all the serotypes in the PCV13 vaccine, plus 22F and 33F. In June 2022, ACIP adopted recommendations regarding the use of PCV15 in children. The main recommendation is that PCV13 and PCV15 can be used interchangeably. The recommended schedule for PCV use in children and the catch-up schedule have not changed, nor has the use of PPSV23 in children with underlying medical conditions.8,9