User login

Genital Wart Treatment

What does your patient need to know?

When a patient presents with a history of genital warts (GWs), find out when and where the lesions started; where the lesions are currently located; what new lesions have developed; what treatments have been administered (eg, physician applied, prescription) and which one(s) worked; what side effects to treatments have been experienced and at what dose; does a partner(s) have similar lesions; is there a history of other sexually transmitted diseases or genital cancer; is he/she immunocompromised (eg, human immunodeficiency virus, transplant, medications); and what is his/her sexual orientation.

Once all of the information has been gathered and the entire anogenital region has been examined, a treatment plan can be formulated. If the patient is immunocompromised or is a man who has sex with men, the risk for anogenital malignancy due to human papillomavirus (HPV) is higher, and GWs, which can be coinfected with oncogenic HPV types, should be treated more aggressively. If the patient is still getting new lesions, use of only a destructive method such as cryotherapy will likely lead to suboptimal results.

Any patients with GWs in the anal region but particularly those in high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients should have an anoscopy to evaluate for lesions on the anal mucosa and in the rectum.

What are your go-to treatments?

Prior treatments need to be taken into account; make sure to understand any side effects and how he/she applied the prior treatment before eliminating it as a viable option. Treatment usually depends on the number of lesions, surface area, anatomic locations involved, and size of the lesions. I start with a 2-pronged approach—a debulking therapy and a patient-applied topical therapy—which allows me to physically remove some of the lesions, typically the larger ones, and then have the patient apply a topical medication at home that will treat the smaller lesions as well as help to clear or decrease the burden of HPV virus on the skin. I use cryotherapy as a debulking agent, but curettage or podophyllin 25% also can be used in the office. I use imiquimod cream 5% as a first-line topical agent at the recommended dose of 3 times weekly; however, if after the first 2 weeks the patient has little response or too much irritation, I titrate the dose so that the patient has mild inflammation on the skin. The dose ultimately can range from daily to once weekly. Some patients who can only tolerate imiquimod once or twice weekly may require zinc oxide paste for the inguinal folds and scrotum to protect from irritation. Alternate topical medications for GWs include sinecatechins ointment 15% or cidofovir ointment 2%.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Start the visit with open communication about the disease, where it came from, what the risks are if it is not treated, and how we can best treat it to make sure we minimize those risks. I explain all of the treatment options as well as our role in treating these lesions and minimizing the risk for disease progression.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Most patients with GWs are motivated to be treated. If pain is a concern, such as with cryotherapy, I recommend topical treatments.

What patient resources do you recommend?

The American Academy of Dermatology (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/contagious-skin-diseases/genital-warts), Harvard Medical School patient education center (Boston, Massachusetts)(http://www.patienteducationcenter.org/articles/genital-warts/), and American Family Physician (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/1215/p2345.html) provide patient materials that I recommend.

What does your patient need to know?

When a patient presents with a history of genital warts (GWs), find out when and where the lesions started; where the lesions are currently located; what new lesions have developed; what treatments have been administered (eg, physician applied, prescription) and which one(s) worked; what side effects to treatments have been experienced and at what dose; does a partner(s) have similar lesions; is there a history of other sexually transmitted diseases or genital cancer; is he/she immunocompromised (eg, human immunodeficiency virus, transplant, medications); and what is his/her sexual orientation.

Once all of the information has been gathered and the entire anogenital region has been examined, a treatment plan can be formulated. If the patient is immunocompromised or is a man who has sex with men, the risk for anogenital malignancy due to human papillomavirus (HPV) is higher, and GWs, which can be coinfected with oncogenic HPV types, should be treated more aggressively. If the patient is still getting new lesions, use of only a destructive method such as cryotherapy will likely lead to suboptimal results.

Any patients with GWs in the anal region but particularly those in high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients should have an anoscopy to evaluate for lesions on the anal mucosa and in the rectum.

What are your go-to treatments?

Prior treatments need to be taken into account; make sure to understand any side effects and how he/she applied the prior treatment before eliminating it as a viable option. Treatment usually depends on the number of lesions, surface area, anatomic locations involved, and size of the lesions. I start with a 2-pronged approach—a debulking therapy and a patient-applied topical therapy—which allows me to physically remove some of the lesions, typically the larger ones, and then have the patient apply a topical medication at home that will treat the smaller lesions as well as help to clear or decrease the burden of HPV virus on the skin. I use cryotherapy as a debulking agent, but curettage or podophyllin 25% also can be used in the office. I use imiquimod cream 5% as a first-line topical agent at the recommended dose of 3 times weekly; however, if after the first 2 weeks the patient has little response or too much irritation, I titrate the dose so that the patient has mild inflammation on the skin. The dose ultimately can range from daily to once weekly. Some patients who can only tolerate imiquimod once or twice weekly may require zinc oxide paste for the inguinal folds and scrotum to protect from irritation. Alternate topical medications for GWs include sinecatechins ointment 15% or cidofovir ointment 2%.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Start the visit with open communication about the disease, where it came from, what the risks are if it is not treated, and how we can best treat it to make sure we minimize those risks. I explain all of the treatment options as well as our role in treating these lesions and minimizing the risk for disease progression.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Most patients with GWs are motivated to be treated. If pain is a concern, such as with cryotherapy, I recommend topical treatments.

What patient resources do you recommend?

The American Academy of Dermatology (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/contagious-skin-diseases/genital-warts), Harvard Medical School patient education center (Boston, Massachusetts)(http://www.patienteducationcenter.org/articles/genital-warts/), and American Family Physician (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/1215/p2345.html) provide patient materials that I recommend.

What does your patient need to know?

When a patient presents with a history of genital warts (GWs), find out when and where the lesions started; where the lesions are currently located; what new lesions have developed; what treatments have been administered (eg, physician applied, prescription) and which one(s) worked; what side effects to treatments have been experienced and at what dose; does a partner(s) have similar lesions; is there a history of other sexually transmitted diseases or genital cancer; is he/she immunocompromised (eg, human immunodeficiency virus, transplant, medications); and what is his/her sexual orientation.

Once all of the information has been gathered and the entire anogenital region has been examined, a treatment plan can be formulated. If the patient is immunocompromised or is a man who has sex with men, the risk for anogenital malignancy due to human papillomavirus (HPV) is higher, and GWs, which can be coinfected with oncogenic HPV types, should be treated more aggressively. If the patient is still getting new lesions, use of only a destructive method such as cryotherapy will likely lead to suboptimal results.

Any patients with GWs in the anal region but particularly those in high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients should have an anoscopy to evaluate for lesions on the anal mucosa and in the rectum.

What are your go-to treatments?

Prior treatments need to be taken into account; make sure to understand any side effects and how he/she applied the prior treatment before eliminating it as a viable option. Treatment usually depends on the number of lesions, surface area, anatomic locations involved, and size of the lesions. I start with a 2-pronged approach—a debulking therapy and a patient-applied topical therapy—which allows me to physically remove some of the lesions, typically the larger ones, and then have the patient apply a topical medication at home that will treat the smaller lesions as well as help to clear or decrease the burden of HPV virus on the skin. I use cryotherapy as a debulking agent, but curettage or podophyllin 25% also can be used in the office. I use imiquimod cream 5% as a first-line topical agent at the recommended dose of 3 times weekly; however, if after the first 2 weeks the patient has little response or too much irritation, I titrate the dose so that the patient has mild inflammation on the skin. The dose ultimately can range from daily to once weekly. Some patients who can only tolerate imiquimod once or twice weekly may require zinc oxide paste for the inguinal folds and scrotum to protect from irritation. Alternate topical medications for GWs include sinecatechins ointment 15% or cidofovir ointment 2%.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Start the visit with open communication about the disease, where it came from, what the risks are if it is not treated, and how we can best treat it to make sure we minimize those risks. I explain all of the treatment options as well as our role in treating these lesions and minimizing the risk for disease progression.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Most patients with GWs are motivated to be treated. If pain is a concern, such as with cryotherapy, I recommend topical treatments.

What patient resources do you recommend?

The American Academy of Dermatology (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/contagious-skin-diseases/genital-warts), Harvard Medical School patient education center (Boston, Massachusetts)(http://www.patienteducationcenter.org/articles/genital-warts/), and American Family Physician (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/1215/p2345.html) provide patient materials that I recommend.

Clinical Pearl: Early Diagnosis of Nail Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis

Practice Gap

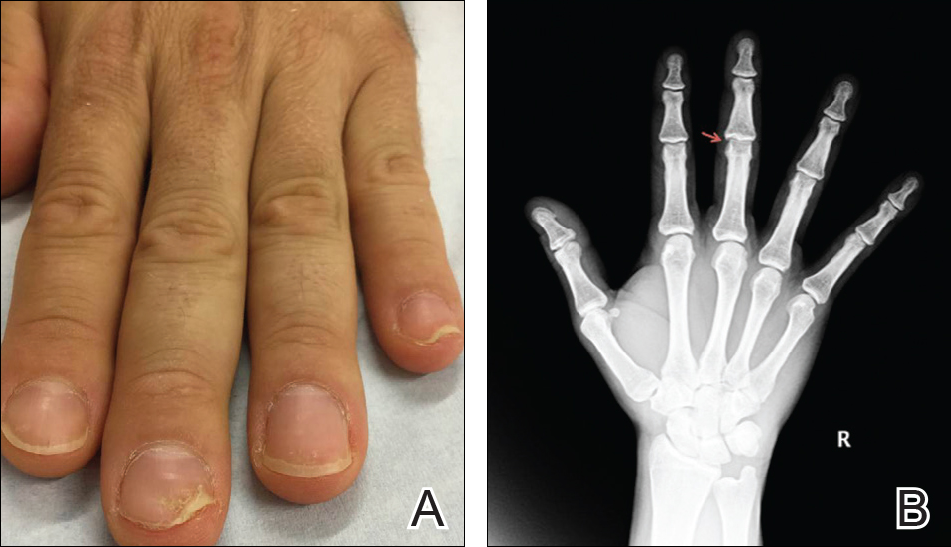

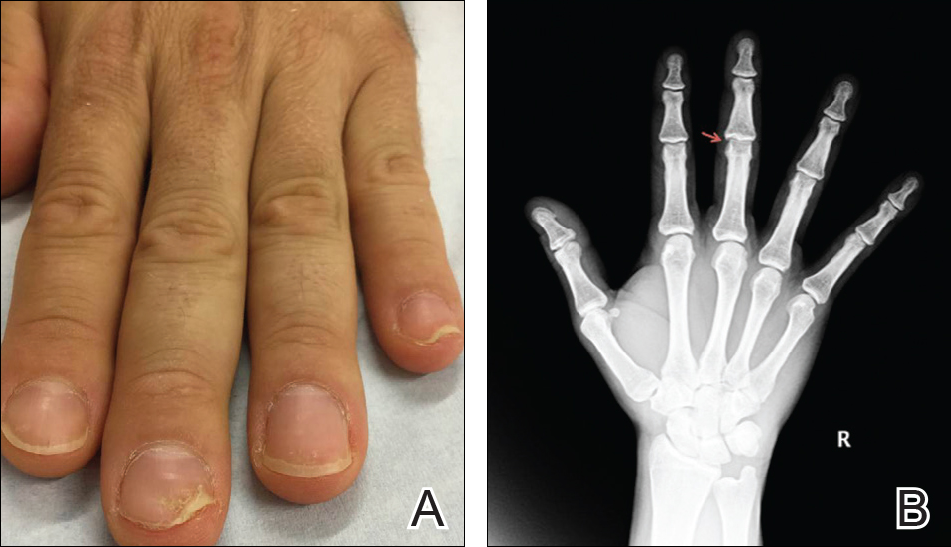

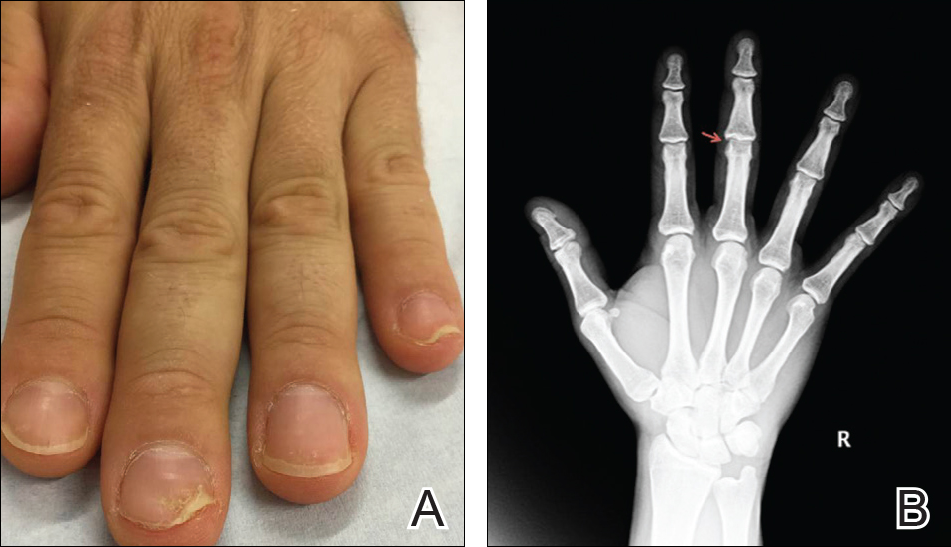

Early diagnosis of nail psoriasis is challenging because nail changes, including pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, crumbling, oil spots, salmon patches, onycholysis, and splinter hemorrhages, may be subtle and nonspecific. Furthermore, 5% to 10% of psoriasis patients do not have skin findings, making the diagnosis of nail psoriasis even more difficult. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is more common in patients with nail psoriasis than in those with cutaneous psoriasis, and early joint damage may be asymptomatic.1 Both nail psoriasis and PsA may progress rapidly, leading to functional impairment with poor quality of life.2

Diagnostic Tool

A 36-year-old man presented with a 4-year history of abnormal fingernails. He denied nail pain but stated that the nails felt sensitive at times and it was difficult to pick up small objects. His medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and attention deficit disorder. He denied joint pain or skin rash.

Physical examination revealed pitting and onycholysis of the fingernails (Figure, A) without involvement of the toenails. A nail clipping was negative for fungus but revealed an incompletely keratinized nail plate with subungual parakeratotic scale, consistent with nail psoriasis. A radiograph showed erosive changes of the third finger of the right hand that were compatible with PsA (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

A nail clipping may be performed to diagnose nail psoriasis. Imaging and/or referral to a rheumatologist should be performed in all patients with isolated nail psoriasis to evaluate for early arthritic changes. If present, appropriate therapy is initiated to prevent further joint damage. In patients with nail psoriasis with or without associated joint pain, dermatologists should consider using radiograph imaging to screen patients for PsA.

- 1. Balestri R, Rech G, Rossi E, et al. Natural history of isolated nail psoriasis and its role as a risk factor for the development of psoriatic arthritis: a single center cross sectional study [published online September 2, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15026.

- Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis, the unknown burden of disease [published online January 15, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1690-1695.

Practice Gap

Early diagnosis of nail psoriasis is challenging because nail changes, including pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, crumbling, oil spots, salmon patches, onycholysis, and splinter hemorrhages, may be subtle and nonspecific. Furthermore, 5% to 10% of psoriasis patients do not have skin findings, making the diagnosis of nail psoriasis even more difficult. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is more common in patients with nail psoriasis than in those with cutaneous psoriasis, and early joint damage may be asymptomatic.1 Both nail psoriasis and PsA may progress rapidly, leading to functional impairment with poor quality of life.2

Diagnostic Tool

A 36-year-old man presented with a 4-year history of abnormal fingernails. He denied nail pain but stated that the nails felt sensitive at times and it was difficult to pick up small objects. His medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and attention deficit disorder. He denied joint pain or skin rash.

Physical examination revealed pitting and onycholysis of the fingernails (Figure, A) without involvement of the toenails. A nail clipping was negative for fungus but revealed an incompletely keratinized nail plate with subungual parakeratotic scale, consistent with nail psoriasis. A radiograph showed erosive changes of the third finger of the right hand that were compatible with PsA (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

A nail clipping may be performed to diagnose nail psoriasis. Imaging and/or referral to a rheumatologist should be performed in all patients with isolated nail psoriasis to evaluate for early arthritic changes. If present, appropriate therapy is initiated to prevent further joint damage. In patients with nail psoriasis with or without associated joint pain, dermatologists should consider using radiograph imaging to screen patients for PsA.

Practice Gap

Early diagnosis of nail psoriasis is challenging because nail changes, including pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, crumbling, oil spots, salmon patches, onycholysis, and splinter hemorrhages, may be subtle and nonspecific. Furthermore, 5% to 10% of psoriasis patients do not have skin findings, making the diagnosis of nail psoriasis even more difficult. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is more common in patients with nail psoriasis than in those with cutaneous psoriasis, and early joint damage may be asymptomatic.1 Both nail psoriasis and PsA may progress rapidly, leading to functional impairment with poor quality of life.2

Diagnostic Tool

A 36-year-old man presented with a 4-year history of abnormal fingernails. He denied nail pain but stated that the nails felt sensitive at times and it was difficult to pick up small objects. His medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and attention deficit disorder. He denied joint pain or skin rash.

Physical examination revealed pitting and onycholysis of the fingernails (Figure, A) without involvement of the toenails. A nail clipping was negative for fungus but revealed an incompletely keratinized nail plate with subungual parakeratotic scale, consistent with nail psoriasis. A radiograph showed erosive changes of the third finger of the right hand that were compatible with PsA (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

A nail clipping may be performed to diagnose nail psoriasis. Imaging and/or referral to a rheumatologist should be performed in all patients with isolated nail psoriasis to evaluate for early arthritic changes. If present, appropriate therapy is initiated to prevent further joint damage. In patients with nail psoriasis with or without associated joint pain, dermatologists should consider using radiograph imaging to screen patients for PsA.

- 1. Balestri R, Rech G, Rossi E, et al. Natural history of isolated nail psoriasis and its role as a risk factor for the development of psoriatic arthritis: a single center cross sectional study [published online September 2, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15026.

- Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis, the unknown burden of disease [published online January 15, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1690-1695.

- 1. Balestri R, Rech G, Rossi E, et al. Natural history of isolated nail psoriasis and its role as a risk factor for the development of psoriatic arthritis: a single center cross sectional study [published online September 2, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15026.

- Klaassen KM, van de Kerkhof PC, Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis, the unknown burden of disease [published online January 15, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1690-1695.

Spot Psoriatic Arthritis Early in Psoriasis Patients

How does psoriatic arthritis present?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) can present in psoriasis patients with an average latency of approximately 10 years. In patients with a strong genetic predisposition, another more severe form of PsA can present earlier in life (<20 years of age). Although PsA generally is classified as a seronegative spondyloarthropathy, more than 10% of patients may in fact be rheumatoid factor-positive. Nail pitting is a feature that can suggest the possibility of PsA, present in almost 90% of patients with PsA.

Who should treat PsA?

Although involving our colleagues in rheumatology is usually beneficial for our patients, in most cases dermatologists can and should effectively manage the care of PsA. The immunology of PsA is the same as psoriasis, which contrasts with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Although active human immunodeficiency virus infection can trigger widespread psoriasis and PsA, RA conversely improves with the depletion of CD4+ cells. Methotrexate, which is used cavalierly by rheumatologists for RA, has a different effect in psoriasis; liver damage is 3 times as likely in psoriasis versus RA at the same doses, while cirrhosis without transaminitis is much more likely with psoriasis patients. Thus, a dermatologist's experience with using systemic medications to treat psoriasis is paramount in successful treatment of PsA.

What medications can we use to treat PsA?

Because halting the progression of PsA is the key to limiting long-term sequelae, systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Treatment options range from methotrexate to most of the newer biologics. Acitretin tends to be ineffective. Apremilast is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors also have demonstrated efficacy in PsA trials. There are some biologics that are used for PsA but do not have an approval for psoriasis, such as certolizumab pegol.

What's new in PsA?

The literature is well established in the classic progression and presentation of PsA, but there is new evidence that the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms, such as joint pain, arthralgia, fatigue, heel pain, and stiffness (Eder et al). The presence of these symptoms may help guide focused questioning and examination.

Another recent study has shown that the incidence of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are more likely in patients with PsA (Zohar et al). It is another important consideration for our patients, especially with recent concerns regarding onset of inflammatory bowel disease with some of the newer biologics we may use to treat psoriasis.

As newer classes of biologic treatments emerge, it will be interesting to see how effective they are in treating PsA in addition to plaque psoriasis. We should be aggressive about treating our patients with psoriasis using systemic therapy if they develop joint pain.

Suggested Readings

Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study [published online October 28, 2016]. Arthritis Rheumatol. doi:10.1002/art.39973.

Zohar A, Cohen AD, Bitterman H, et al. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis [published online August 17, 2016]. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2679-2684.

How does psoriatic arthritis present?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) can present in psoriasis patients with an average latency of approximately 10 years. In patients with a strong genetic predisposition, another more severe form of PsA can present earlier in life (<20 years of age). Although PsA generally is classified as a seronegative spondyloarthropathy, more than 10% of patients may in fact be rheumatoid factor-positive. Nail pitting is a feature that can suggest the possibility of PsA, present in almost 90% of patients with PsA.

Who should treat PsA?

Although involving our colleagues in rheumatology is usually beneficial for our patients, in most cases dermatologists can and should effectively manage the care of PsA. The immunology of PsA is the same as psoriasis, which contrasts with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Although active human immunodeficiency virus infection can trigger widespread psoriasis and PsA, RA conversely improves with the depletion of CD4+ cells. Methotrexate, which is used cavalierly by rheumatologists for RA, has a different effect in psoriasis; liver damage is 3 times as likely in psoriasis versus RA at the same doses, while cirrhosis without transaminitis is much more likely with psoriasis patients. Thus, a dermatologist's experience with using systemic medications to treat psoriasis is paramount in successful treatment of PsA.

What medications can we use to treat PsA?

Because halting the progression of PsA is the key to limiting long-term sequelae, systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Treatment options range from methotrexate to most of the newer biologics. Acitretin tends to be ineffective. Apremilast is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors also have demonstrated efficacy in PsA trials. There are some biologics that are used for PsA but do not have an approval for psoriasis, such as certolizumab pegol.

What's new in PsA?

The literature is well established in the classic progression and presentation of PsA, but there is new evidence that the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms, such as joint pain, arthralgia, fatigue, heel pain, and stiffness (Eder et al). The presence of these symptoms may help guide focused questioning and examination.

Another recent study has shown that the incidence of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are more likely in patients with PsA (Zohar et al). It is another important consideration for our patients, especially with recent concerns regarding onset of inflammatory bowel disease with some of the newer biologics we may use to treat psoriasis.

As newer classes of biologic treatments emerge, it will be interesting to see how effective they are in treating PsA in addition to plaque psoriasis. We should be aggressive about treating our patients with psoriasis using systemic therapy if they develop joint pain.

Suggested Readings

Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study [published online October 28, 2016]. Arthritis Rheumatol. doi:10.1002/art.39973.

Zohar A, Cohen AD, Bitterman H, et al. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis [published online August 17, 2016]. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2679-2684.

How does psoriatic arthritis present?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) can present in psoriasis patients with an average latency of approximately 10 years. In patients with a strong genetic predisposition, another more severe form of PsA can present earlier in life (<20 years of age). Although PsA generally is classified as a seronegative spondyloarthropathy, more than 10% of patients may in fact be rheumatoid factor-positive. Nail pitting is a feature that can suggest the possibility of PsA, present in almost 90% of patients with PsA.

Who should treat PsA?

Although involving our colleagues in rheumatology is usually beneficial for our patients, in most cases dermatologists can and should effectively manage the care of PsA. The immunology of PsA is the same as psoriasis, which contrasts with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Although active human immunodeficiency virus infection can trigger widespread psoriasis and PsA, RA conversely improves with the depletion of CD4+ cells. Methotrexate, which is used cavalierly by rheumatologists for RA, has a different effect in psoriasis; liver damage is 3 times as likely in psoriasis versus RA at the same doses, while cirrhosis without transaminitis is much more likely with psoriasis patients. Thus, a dermatologist's experience with using systemic medications to treat psoriasis is paramount in successful treatment of PsA.

What medications can we use to treat PsA?

Because halting the progression of PsA is the key to limiting long-term sequelae, systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Treatment options range from methotrexate to most of the newer biologics. Acitretin tends to be ineffective. Apremilast is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors also have demonstrated efficacy in PsA trials. There are some biologics that are used for PsA but do not have an approval for psoriasis, such as certolizumab pegol.

What's new in PsA?

The literature is well established in the classic progression and presentation of PsA, but there is new evidence that the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms, such as joint pain, arthralgia, fatigue, heel pain, and stiffness (Eder et al). The presence of these symptoms may help guide focused questioning and examination.

Another recent study has shown that the incidence of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are more likely in patients with PsA (Zohar et al). It is another important consideration for our patients, especially with recent concerns regarding onset of inflammatory bowel disease with some of the newer biologics we may use to treat psoriasis.

As newer classes of biologic treatments emerge, it will be interesting to see how effective they are in treating PsA in addition to plaque psoriasis. We should be aggressive about treating our patients with psoriasis using systemic therapy if they develop joint pain.

Suggested Readings

Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of PsA in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study [published online October 28, 2016]. Arthritis Rheumatol. doi:10.1002/art.39973.

Zohar A, Cohen AD, Bitterman H, et al. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis [published online August 17, 2016]. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2679-2684.

Proper Wound Management: How to Work With Patients

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum (Source: Wound Care Centers)(http://www.woundcarecenters.org/article/wound-types/pyoderma-gangrenosum)

- Take the Pressure Off: A Patient Guide for Preventing and Treating Pressure Ulcers (Source: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care)(http://aawconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Take-the-Pressure-Off.pdf)

- Wound Healing Society (http://woundheal.org/home.aspx)

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum (Source: Wound Care Centers)(http://www.woundcarecenters.org/article/wound-types/pyoderma-gangrenosum)

- Take the Pressure Off: A Patient Guide for Preventing and Treating Pressure Ulcers (Source: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care)(http://aawconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Take-the-Pressure-Off.pdf)

- Wound Healing Society (http://woundheal.org/home.aspx)

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum (Source: Wound Care Centers)(http://www.woundcarecenters.org/article/wound-types/pyoderma-gangrenosum)

- Take the Pressure Off: A Patient Guide for Preventing and Treating Pressure Ulcers (Source: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care)(http://aawconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Take-the-Pressure-Off.pdf)

- Wound Healing Society (http://woundheal.org/home.aspx)

Using a Combination of Therapies to Manage Rosacea

What do your patients need to know at the first visit?

Patients need to understand that rosacea has no gender, age, or race predilection. It is caused by a personal and genetic proinflammatory predisposition. Rosacea patients seem to have a genetic predisposition to overproduce cathelicidins, a small antimicrobial peptide that is produced by the action of stratum corneum tryptic enzyme. They have more production and abnormal forms of cathelicidins produced by high levels of stratum corneum tryptic enzyme. This upregulation of inflammatory cathelicidins on the dermis is associated with vascular instability and exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather.

I divide the condition into proinflammatory predisposition, vascular instability with redness, Demodex infection of the hair follicle, and sebaceous gland overgrowth. More recently, the bacterium Bacillus oleronius was isolated from inside a Demodex mite and was found to produce molecules provoking an immune reaction in rosacea patients (Erbaguci and Ozgöztaşi). Other studies have shown that patients with varying types of rosacea react to the molecules produced by this bacterium, exposing it as a likely trigger for the condition (Li et al). What’s more, this bacterium is sensitive to the antibiotics used to treat rosacea.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

For inflammation I prescribe anti-inflammatory (low dose) or antibacterial (high dose) doses of doxycycline and/or anti-inflammatory azelaic acid gel 15% twice daily after application of barrier repair topical hyaluronic acid. For the vascular component I use the temporary relief from the application of brimonidine gel 0.33% in the morning in addition to the topical given for inflammatory rosacea, and the more durable excel V (532 and 1064 nm) laser. Ultimately, topical ivermectin is prescribed for those patients who do not respond to previously mentioned treatments for coverage of Demodex infestation. For rhinophyma I offer a surgical approach and laser treatments; surgical removal of the excess glandular growth is followed by fractional ablative and nonablative treatments for scar reduction after surgery.

All patients should apply an inorganic sun protection factor 50+ sunblock with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide to prevent sunlight from being a trigger. All patients are encouraged to avoid triggers.

I try to prevent the potential side effects associated with rosacea treatments. For example, applying barrier repair hyaluronic acid before azelaic acid to prevent irritation and telling patients they might have vascular rebound phenomena with more redness after brimonidine application wears off. I also explain to patients that laser treatments induce temporary erythema and swelling that may last 3 days.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

In general, my patients are compliant with their treatments, which I ascribe to the simplicity of a twice-daily regimen that is written for them. They understand that I design a treatment regimen for each individual patient based on his/her presentation.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend web-based resources that can provide further assistance and information, such as the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/rosacea), National Rosacea Society (www.rosacea.org), and specific disease foundations (eg, International Rosacea Foundation [www.internationalrosaceafoundation.org]).Suggested Readings

- Erbaguci Z, Ozgöztaşi O. The significance of Demodex folliculorum density in rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:421-425.

- Li J, O’Reilly N, Sheha H, et al. Correlation between ocular Demodex infestation and serum immunoreactivity to Bacillus proteins in patients with facial rosacea. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:870-877.

What do your patients need to know at the first visit?

Patients need to understand that rosacea has no gender, age, or race predilection. It is caused by a personal and genetic proinflammatory predisposition. Rosacea patients seem to have a genetic predisposition to overproduce cathelicidins, a small antimicrobial peptide that is produced by the action of stratum corneum tryptic enzyme. They have more production and abnormal forms of cathelicidins produced by high levels of stratum corneum tryptic enzyme. This upregulation of inflammatory cathelicidins on the dermis is associated with vascular instability and exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather.

I divide the condition into proinflammatory predisposition, vascular instability with redness, Demodex infection of the hair follicle, and sebaceous gland overgrowth. More recently, the bacterium Bacillus oleronius was isolated from inside a Demodex mite and was found to produce molecules provoking an immune reaction in rosacea patients (Erbaguci and Ozgöztaşi). Other studies have shown that patients with varying types of rosacea react to the molecules produced by this bacterium, exposing it as a likely trigger for the condition (Li et al). What’s more, this bacterium is sensitive to the antibiotics used to treat rosacea.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

For inflammation I prescribe anti-inflammatory (low dose) or antibacterial (high dose) doses of doxycycline and/or anti-inflammatory azelaic acid gel 15% twice daily after application of barrier repair topical hyaluronic acid. For the vascular component I use the temporary relief from the application of brimonidine gel 0.33% in the morning in addition to the topical given for inflammatory rosacea, and the more durable excel V (532 and 1064 nm) laser. Ultimately, topical ivermectin is prescribed for those patients who do not respond to previously mentioned treatments for coverage of Demodex infestation. For rhinophyma I offer a surgical approach and laser treatments; surgical removal of the excess glandular growth is followed by fractional ablative and nonablative treatments for scar reduction after surgery.

All patients should apply an inorganic sun protection factor 50+ sunblock with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide to prevent sunlight from being a trigger. All patients are encouraged to avoid triggers.

I try to prevent the potential side effects associated with rosacea treatments. For example, applying barrier repair hyaluronic acid before azelaic acid to prevent irritation and telling patients they might have vascular rebound phenomena with more redness after brimonidine application wears off. I also explain to patients that laser treatments induce temporary erythema and swelling that may last 3 days.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

In general, my patients are compliant with their treatments, which I ascribe to the simplicity of a twice-daily regimen that is written for them. They understand that I design a treatment regimen for each individual patient based on his/her presentation.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend web-based resources that can provide further assistance and information, such as the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/rosacea), National Rosacea Society (www.rosacea.org), and specific disease foundations (eg, International Rosacea Foundation [www.internationalrosaceafoundation.org]).Suggested Readings

- Erbaguci Z, Ozgöztaşi O. The significance of Demodex folliculorum density in rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:421-425.

- Li J, O’Reilly N, Sheha H, et al. Correlation between ocular Demodex infestation and serum immunoreactivity to Bacillus proteins in patients with facial rosacea. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:870-877.

What do your patients need to know at the first visit?

Patients need to understand that rosacea has no gender, age, or race predilection. It is caused by a personal and genetic proinflammatory predisposition. Rosacea patients seem to have a genetic predisposition to overproduce cathelicidins, a small antimicrobial peptide that is produced by the action of stratum corneum tryptic enzyme. They have more production and abnormal forms of cathelicidins produced by high levels of stratum corneum tryptic enzyme. This upregulation of inflammatory cathelicidins on the dermis is associated with vascular instability and exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather.

I divide the condition into proinflammatory predisposition, vascular instability with redness, Demodex infection of the hair follicle, and sebaceous gland overgrowth. More recently, the bacterium Bacillus oleronius was isolated from inside a Demodex mite and was found to produce molecules provoking an immune reaction in rosacea patients (Erbaguci and Ozgöztaşi). Other studies have shown that patients with varying types of rosacea react to the molecules produced by this bacterium, exposing it as a likely trigger for the condition (Li et al). What’s more, this bacterium is sensitive to the antibiotics used to treat rosacea.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

For inflammation I prescribe anti-inflammatory (low dose) or antibacterial (high dose) doses of doxycycline and/or anti-inflammatory azelaic acid gel 15% twice daily after application of barrier repair topical hyaluronic acid. For the vascular component I use the temporary relief from the application of brimonidine gel 0.33% in the morning in addition to the topical given for inflammatory rosacea, and the more durable excel V (532 and 1064 nm) laser. Ultimately, topical ivermectin is prescribed for those patients who do not respond to previously mentioned treatments for coverage of Demodex infestation. For rhinophyma I offer a surgical approach and laser treatments; surgical removal of the excess glandular growth is followed by fractional ablative and nonablative treatments for scar reduction after surgery.

All patients should apply an inorganic sun protection factor 50+ sunblock with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide to prevent sunlight from being a trigger. All patients are encouraged to avoid triggers.

I try to prevent the potential side effects associated with rosacea treatments. For example, applying barrier repair hyaluronic acid before azelaic acid to prevent irritation and telling patients they might have vascular rebound phenomena with more redness after brimonidine application wears off. I also explain to patients that laser treatments induce temporary erythema and swelling that may last 3 days.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

In general, my patients are compliant with their treatments, which I ascribe to the simplicity of a twice-daily regimen that is written for them. They understand that I design a treatment regimen for each individual patient based on his/her presentation.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend web-based resources that can provide further assistance and information, such as the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/rosacea), National Rosacea Society (www.rosacea.org), and specific disease foundations (eg, International Rosacea Foundation [www.internationalrosaceafoundation.org]).Suggested Readings

- Erbaguci Z, Ozgöztaşi O. The significance of Demodex folliculorum density in rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:421-425.

- Li J, O’Reilly N, Sheha H, et al. Correlation between ocular Demodex infestation and serum immunoreactivity to Bacillus proteins in patients with facial rosacea. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:870-877.

Tips and Tools for Melanoma Diagnosis

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to all patients?

All patients should have a total-body skin examination at least once per year; however, the frequency may change based on a prior history of melanoma or skin cancer, number of nevi or dysplastic nevi, and a family history of melanoma.

Patients should be completely undressed, and all nail polish or artificial nails should be removed prior to the examination. A complete cutaneous examination involves inspecting all skin surfaces, scalp, ocular and oral mucosa, fingernails/toenails, and genitalia if the patient agrees. Melanoma can occur in non–UV-exposed areas and the patient should be educated. Explain the ABCDEs of melanoma diagnosis to all patients and discuss concerns of any new or changing lesions, pigmented or not.

The patient should be made aware that a series of digital images will be taken for any suspicious lesions for possible short-term monitoring. The patient also may be offered full-body photography or 3D body imaging if the number of nevi warrants it.

Different patient populations have different risks for melanoma. Although melanoma predominately afflicts patients with a light skin type, there are certain types of melanoma, such as acral melanoma, that can be more common in darker skin types.

If a patient has a history of cutaneous melanoma, then the site should be checked for any local recurrence as well as palpation of the draining lymph nodes and regional lymph nodes.

I also let patients know that I will be using tools such as dermoscopy and/or reflectance confocal microscopy to better diagnose equivocal lesions before pursuing a biopsy. A biopsy may be done if there is a level of suspicion for atypia.

The use of dermoscopy, digital imaging, and reflectance confocal microscopy has changed the way we can detect, monitor, and evaluate atypical nevi. These tools can augment practice and possibly cut down on the rate of biopsies. They also are great for equivocal lesions or lesions that are in cosmetically sensitive areas. I use these tools in my everyday practice.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Empowering patients to perform self-examinations as well as examinations with his/her partner may help to reinforce monitoring by a dermatologist.

Provide patients with reading materials on self-examination while they wait in the office for your examination.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients defer a full-body skin examination, then I try to educate them about risks for UV exposure and the risk factors for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. I also provide information on self-examinations so they can check at home for any irregularly shaped or changing moles.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is important for patients to understand the risk factors for melanoma and the long-term prognosis of melanoma. I direct them to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website (http://www.AAD.org) for education and background about melanoma. Also, the Skin Cancer Foundation has inspiring patient stories (http://www.SkinCancer.org).

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to all patients?

All patients should have a total-body skin examination at least once per year; however, the frequency may change based on a prior history of melanoma or skin cancer, number of nevi or dysplastic nevi, and a family history of melanoma.

Patients should be completely undressed, and all nail polish or artificial nails should be removed prior to the examination. A complete cutaneous examination involves inspecting all skin surfaces, scalp, ocular and oral mucosa, fingernails/toenails, and genitalia if the patient agrees. Melanoma can occur in non–UV-exposed areas and the patient should be educated. Explain the ABCDEs of melanoma diagnosis to all patients and discuss concerns of any new or changing lesions, pigmented or not.

The patient should be made aware that a series of digital images will be taken for any suspicious lesions for possible short-term monitoring. The patient also may be offered full-body photography or 3D body imaging if the number of nevi warrants it.

Different patient populations have different risks for melanoma. Although melanoma predominately afflicts patients with a light skin type, there are certain types of melanoma, such as acral melanoma, that can be more common in darker skin types.

If a patient has a history of cutaneous melanoma, then the site should be checked for any local recurrence as well as palpation of the draining lymph nodes and regional lymph nodes.

I also let patients know that I will be using tools such as dermoscopy and/or reflectance confocal microscopy to better diagnose equivocal lesions before pursuing a biopsy. A biopsy may be done if there is a level of suspicion for atypia.

The use of dermoscopy, digital imaging, and reflectance confocal microscopy has changed the way we can detect, monitor, and evaluate atypical nevi. These tools can augment practice and possibly cut down on the rate of biopsies. They also are great for equivocal lesions or lesions that are in cosmetically sensitive areas. I use these tools in my everyday practice.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Empowering patients to perform self-examinations as well as examinations with his/her partner may help to reinforce monitoring by a dermatologist.

Provide patients with reading materials on self-examination while they wait in the office for your examination.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients defer a full-body skin examination, then I try to educate them about risks for UV exposure and the risk factors for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. I also provide information on self-examinations so they can check at home for any irregularly shaped or changing moles.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is important for patients to understand the risk factors for melanoma and the long-term prognosis of melanoma. I direct them to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website (http://www.AAD.org) for education and background about melanoma. Also, the Skin Cancer Foundation has inspiring patient stories (http://www.SkinCancer.org).

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to all patients?

All patients should have a total-body skin examination at least once per year; however, the frequency may change based on a prior history of melanoma or skin cancer, number of nevi or dysplastic nevi, and a family history of melanoma.

Patients should be completely undressed, and all nail polish or artificial nails should be removed prior to the examination. A complete cutaneous examination involves inspecting all skin surfaces, scalp, ocular and oral mucosa, fingernails/toenails, and genitalia if the patient agrees. Melanoma can occur in non–UV-exposed areas and the patient should be educated. Explain the ABCDEs of melanoma diagnosis to all patients and discuss concerns of any new or changing lesions, pigmented or not.

The patient should be made aware that a series of digital images will be taken for any suspicious lesions for possible short-term monitoring. The patient also may be offered full-body photography or 3D body imaging if the number of nevi warrants it.

Different patient populations have different risks for melanoma. Although melanoma predominately afflicts patients with a light skin type, there are certain types of melanoma, such as acral melanoma, that can be more common in darker skin types.

If a patient has a history of cutaneous melanoma, then the site should be checked for any local recurrence as well as palpation of the draining lymph nodes and regional lymph nodes.

I also let patients know that I will be using tools such as dermoscopy and/or reflectance confocal microscopy to better diagnose equivocal lesions before pursuing a biopsy. A biopsy may be done if there is a level of suspicion for atypia.

The use of dermoscopy, digital imaging, and reflectance confocal microscopy has changed the way we can detect, monitor, and evaluate atypical nevi. These tools can augment practice and possibly cut down on the rate of biopsies. They also are great for equivocal lesions or lesions that are in cosmetically sensitive areas. I use these tools in my everyday practice.

How do you keep patients compliant?

Empowering patients to perform self-examinations as well as examinations with his/her partner may help to reinforce monitoring by a dermatologist.

Provide patients with reading materials on self-examination while they wait in the office for your examination.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients defer a full-body skin examination, then I try to educate them about risks for UV exposure and the risk factors for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. I also provide information on self-examinations so they can check at home for any irregularly shaped or changing moles.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is important for patients to understand the risk factors for melanoma and the long-term prognosis of melanoma. I direct them to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website (http://www.AAD.org) for education and background about melanoma. Also, the Skin Cancer Foundation has inspiring patient stories (http://www.SkinCancer.org).

Laser Best Practices for Darker Skin Types

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

Clinical Pearl: Increasing Utility of Isopropyl Alcohol for Cutaneous Dyschromia

Practice Gap

Conditions with dyschromia including terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD), confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (CARP), and acanthosis nigricans are difficult to distinguish from one another.

Diagnostic Tools

Since its development in 1920, dermatologists have utilized isopropyl alcohol in ways that exceed conventional antimicrobial purposes. If TFFP, CARP, and acanthosis nigricans are suspected, the first step in any algorithmic approach should be to rub the skin with an alcohol pad using firm continuous pressure in an attempt to remove pigmentation. Complete resolution of dyspigmentation strongly supports a diagnosis of TFFD1 and can be curative (Figure). Alcohol can similarly lighten CARP but to a lesser degree than TFFD.2 In contrast, acanthosis nigricans will display minimal to no improvement with isopropyl alcohol.

Practice Implications

Isopropyl alcohol has few side effects and each swab costs less than a dime. It is extremely cost effective compared to biopsy and subsequent pathology and laboratory costs. Patients appreciate a noninvasive initial approach, and it is rewarding to treat a cosmetically disturbing condition with ease.

Swabbing the skin with alcohol pads reflects light and improves visualization of veins that should be avoided during surgery. Alcohol-based gel inhibits bacterial colonization, reduces dermatoscope-related nosocomial infection, and enhances dermoscopic resolution.3 Alcohol swabs quickly remove gentian violet, which aids in porokeratosis diagnosis; the pathognomonic cornoid lamella of porokeratosis retains gentian violet.4 A solution of 70% isopropyl alcohol preserves myiasis larvae better than formalin, which causes larval tissue hardening. Alcohol also can be squeezed into the central punctum in myiasis as a form of treatment.5 In conclusion, alcohol represents a convenient, inexpensive, and helpful tool in the dermatologist’s armamentarium that should not be forgotten.

- Browning J, Rosen T. Terra firma-forme dermatosis revisited. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:15.

- Berk DR. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis response to 70% alcohol swabbing. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:247-248.

- Kelly SC, Purcell SM. Prevention of nosocomial infection during dermoscopy? Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:552-555.