User login

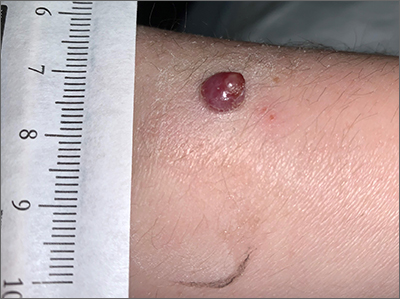

Toe growth

Shave biopsy was consistent with a solitary periungual angiofibroma, often termed a Koenen tumor. These can manifest as a soft pink papule (as with this patient), sometimes with a distal keratinaceous tip. At times, the nail bed and nail plate may be deformed because of the angiofibroma.

Periungual angiofibromas can occur sporadically in children and adults, it was a solitary finding in this case. Importantly, periungual angiofibromas may also occur as a visible sign of a multisystem genetic disorder known as tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). TSC causes benign tumors to develop throughout the body (eg, skin, brain, heart, lungs). The condition can be mild or lead to serious disabilities, including seizures and developmental delays.

In isolation, periungual angiofibromas are benign but occasionally hurt or bleed from light trauma. In such cases, or for cosmetic reasons, patients may seek treatments. Complete excision of the lesion may include the affected portion of the nail bed or matrix. This is more easily repaired when the lesion is on the lateral nail fold, facilitating an en bloc fusiform excision and matrixectomy.1 Surgical excision of a lesion in the mid-proximal nail fold is much more likely to result in long-term nail deformity. Electrosurgery and various laser modalities have been successful as less invasive removal options.2 While expensive, topical sirolimus 1% has been used successfully in sporadic angiofibromas and those associated with TSC.

The patient in this case underwent lateral nail fold excision with complete removal of the tumor and repair with a side-to-side closure.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Tisa LM, Iurcotta A. Solitary periungual angiofibroma. An unusual case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1993;83:679-80. doi: 10.7547/87507315-83-12-679

2. Boixeda P, Sánchez-Miralles E, Azaña JM, et al. CO2, argon, and pulsed dye laser treatment of angiofibromas. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:808-812. doi: 10.1111/j.1524- 4725.1994.tb03709.x

Shave biopsy was consistent with a solitary periungual angiofibroma, often termed a Koenen tumor. These can manifest as a soft pink papule (as with this patient), sometimes with a distal keratinaceous tip. At times, the nail bed and nail plate may be deformed because of the angiofibroma.

Periungual angiofibromas can occur sporadically in children and adults, it was a solitary finding in this case. Importantly, periungual angiofibromas may also occur as a visible sign of a multisystem genetic disorder known as tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). TSC causes benign tumors to develop throughout the body (eg, skin, brain, heart, lungs). The condition can be mild or lead to serious disabilities, including seizures and developmental delays.

In isolation, periungual angiofibromas are benign but occasionally hurt or bleed from light trauma. In such cases, or for cosmetic reasons, patients may seek treatments. Complete excision of the lesion may include the affected portion of the nail bed or matrix. This is more easily repaired when the lesion is on the lateral nail fold, facilitating an en bloc fusiform excision and matrixectomy.1 Surgical excision of a lesion in the mid-proximal nail fold is much more likely to result in long-term nail deformity. Electrosurgery and various laser modalities have been successful as less invasive removal options.2 While expensive, topical sirolimus 1% has been used successfully in sporadic angiofibromas and those associated with TSC.

The patient in this case underwent lateral nail fold excision with complete removal of the tumor and repair with a side-to-side closure.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Shave biopsy was consistent with a solitary periungual angiofibroma, often termed a Koenen tumor. These can manifest as a soft pink papule (as with this patient), sometimes with a distal keratinaceous tip. At times, the nail bed and nail plate may be deformed because of the angiofibroma.

Periungual angiofibromas can occur sporadically in children and adults, it was a solitary finding in this case. Importantly, periungual angiofibromas may also occur as a visible sign of a multisystem genetic disorder known as tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). TSC causes benign tumors to develop throughout the body (eg, skin, brain, heart, lungs). The condition can be mild or lead to serious disabilities, including seizures and developmental delays.

In isolation, periungual angiofibromas are benign but occasionally hurt or bleed from light trauma. In such cases, or for cosmetic reasons, patients may seek treatments. Complete excision of the lesion may include the affected portion of the nail bed or matrix. This is more easily repaired when the lesion is on the lateral nail fold, facilitating an en bloc fusiform excision and matrixectomy.1 Surgical excision of a lesion in the mid-proximal nail fold is much more likely to result in long-term nail deformity. Electrosurgery and various laser modalities have been successful as less invasive removal options.2 While expensive, topical sirolimus 1% has been used successfully in sporadic angiofibromas and those associated with TSC.

The patient in this case underwent lateral nail fold excision with complete removal of the tumor and repair with a side-to-side closure.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Tisa LM, Iurcotta A. Solitary periungual angiofibroma. An unusual case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1993;83:679-80. doi: 10.7547/87507315-83-12-679

2. Boixeda P, Sánchez-Miralles E, Azaña JM, et al. CO2, argon, and pulsed dye laser treatment of angiofibromas. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:808-812. doi: 10.1111/j.1524- 4725.1994.tb03709.x

1. Tisa LM, Iurcotta A. Solitary periungual angiofibroma. An unusual case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1993;83:679-80. doi: 10.7547/87507315-83-12-679

2. Boixeda P, Sánchez-Miralles E, Azaña JM, et al. CO2, argon, and pulsed dye laser treatment of angiofibromas. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:808-812. doi: 10.1111/j.1524- 4725.1994.tb03709.x

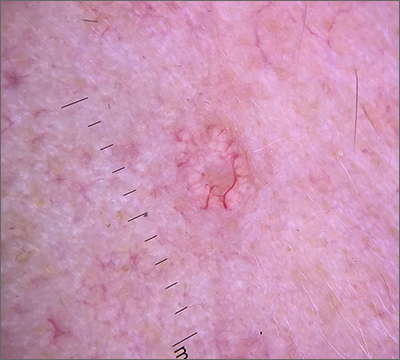

Leg lesions

A 4-mm punch biopsy performed on the central portion of a lesion revealed thickening of the epidermis and altered collagen in the dermis consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC).

ARPC is strongly associated with diabetes, renal disease, and malignancy. ARPC manifests as an eruption of intensely pruritic papules to small plaques (with a central plug or firm dry depression) on the trunk, or more commonly, on the extremities. The etiology is unclear but altered collagen from systemic disease, trauma, or cold exposure may trigger collagen elimination.1 Secondary infection may occur due to the intensity of itching. ARPC develops in adulthood; epidemiologic data are lacking and prevalence has not been systematically assessed.2

Treatment approaches are based on small case reports and case series. Common antipruritic therapies, such as topical and intralesional steroids, oral antihistamines, and vitamin-D analogues, have had mixed success. UV therapy is effective for nephrogenic pruritus; case reports suggest it has also been helpful for ARPC. Similarly, keratolytics and topical and systemic retinoids have shown promise. Allopurinol, which reduces free radicals, has also demonstrated its utility.3

This patient was started on topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid and narrowband UV-B phototherapy 3 times weekly with marked improvement in her itching. Lesions decreased in number over 3 months of follow-up but did not completely resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Zhang X, Yang Y, Shao S. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20391. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020391

2. Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00918.x

3. Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating dermatosis - a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:825-842. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13561

A 4-mm punch biopsy performed on the central portion of a lesion revealed thickening of the epidermis and altered collagen in the dermis consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC).

ARPC is strongly associated with diabetes, renal disease, and malignancy. ARPC manifests as an eruption of intensely pruritic papules to small plaques (with a central plug or firm dry depression) on the trunk, or more commonly, on the extremities. The etiology is unclear but altered collagen from systemic disease, trauma, or cold exposure may trigger collagen elimination.1 Secondary infection may occur due to the intensity of itching. ARPC develops in adulthood; epidemiologic data are lacking and prevalence has not been systematically assessed.2

Treatment approaches are based on small case reports and case series. Common antipruritic therapies, such as topical and intralesional steroids, oral antihistamines, and vitamin-D analogues, have had mixed success. UV therapy is effective for nephrogenic pruritus; case reports suggest it has also been helpful for ARPC. Similarly, keratolytics and topical and systemic retinoids have shown promise. Allopurinol, which reduces free radicals, has also demonstrated its utility.3

This patient was started on topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid and narrowband UV-B phototherapy 3 times weekly with marked improvement in her itching. Lesions decreased in number over 3 months of follow-up but did not completely resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A 4-mm punch biopsy performed on the central portion of a lesion revealed thickening of the epidermis and altered collagen in the dermis consistent with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC).

ARPC is strongly associated with diabetes, renal disease, and malignancy. ARPC manifests as an eruption of intensely pruritic papules to small plaques (with a central plug or firm dry depression) on the trunk, or more commonly, on the extremities. The etiology is unclear but altered collagen from systemic disease, trauma, or cold exposure may trigger collagen elimination.1 Secondary infection may occur due to the intensity of itching. ARPC develops in adulthood; epidemiologic data are lacking and prevalence has not been systematically assessed.2

Treatment approaches are based on small case reports and case series. Common antipruritic therapies, such as topical and intralesional steroids, oral antihistamines, and vitamin-D analogues, have had mixed success. UV therapy is effective for nephrogenic pruritus; case reports suggest it has also been helpful for ARPC. Similarly, keratolytics and topical and systemic retinoids have shown promise. Allopurinol, which reduces free radicals, has also demonstrated its utility.3

This patient was started on topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid and narrowband UV-B phototherapy 3 times weekly with marked improvement in her itching. Lesions decreased in number over 3 months of follow-up but did not completely resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Zhang X, Yang Y, Shao S. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20391. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020391

2. Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00918.x

3. Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating dermatosis - a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:825-842. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13561

1. Zhang X, Yang Y, Shao S. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20391. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020391

2. Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00918.x

3. Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating dermatosis - a systematic review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:825-842. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13561

Milium cysts on hands; hypertrichosis on face

A 55-YEAR-OLD MAN with hypertension and untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) was referred to the Dermatology Clinic after reporting a 2-year history of photosensitivity and intermittent episodes of blistering and scars on the dorsal side of his hands and feet. No alcohol consumption or drug use was reported.

Physical examination revealed small and shallow erosions on the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet (but no visible blisters) and milium cysts (FIGURE 1A). Additionally, hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation were observed in the zygomatic areas (FIGURE 1B). Complete blood count and kidney function test results were within normal ranges. Liver function tests showed slightly elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase (79 U/L; normal range, 0-41 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (62 U/L; normal range, 0-40 U/L), and ferritin (121 ng/mL; normal range, 30-100 ng/mL). Serologies for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B virus were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

The porphyrias are a group of metabolic diseases that affect the heme biosynthesis. They can be classified into 1 of 3 groups, according to clinical features:

- acute hepatic porphyrias, with neurovisceral symptoms (eg, acute intermittent porphyria),

- nonblistering cutaneous porphyrias, with severe photosensitivity but without bullae formation (eg, erythropoietic protoporphyria), or

- blistering cutaneous porphyrias (eg, PCT, hepatoerythropoietic porphyria, and variegate porphyria).

PCT is the most common type of porphyria, with a global prevalence of 1 per 10,000 people.1,2 It affects adults after the third or fourth decade of life.

PCT involves dysfunction of the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase enzyme (UROD), the fifth enzyme in heme biosynthesis, which catalyzes the conversion of uroporphyrinogen to coproporphyrinogen. This dysfunction causes the accumulation of porphyrinogens that are auto-oxidized to photosensitizing porphyrins.1-4 PCT can be classified as “sporadic” or “familial” based on the absence or presence of UROD mutation. Approximately 80% of cases of PCT are sporadic.2

In sporadic PCT, triggers for UROD dysfunction include alcohol use, use of estrogens, hemochromatosis or iron overload, chronic HCV infection, and HIV infection.1-4 HCV (which this patient had) is the most common infection associated with sporadic PCT, with a prevalence of about 50% among these patients.5

Continue to: Dermatologic manifestations of PCT

Dermatologic manifestations of PCT include photosensitivity, skin fragility, vesicles, bullae, erosions, and crusts observed in sun-exposed areas. A nonvirilizing type of hypertrichosis may appear prominently on the temples and the cheeks.2-4 After blisters rupture, atrophy and scarring occur. Milia cysts can form on the dorsal side of the hands and fingers. Less common manifestations include pruritus, scarring alopecia, sclerodermatous changes, and periorbital purple-red suffusion.

Hepatic involvement is demonstrated with elevated serum transaminases and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Hepatomegaly is common, and cirrhosis manifests in 30% to 40% of patients.2-5 On liver biopsy, some degree of siderosis is found in 80% of patients with PCT, and most of them have increased levels of serum iron. The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with PCT is greater than in patients with other liver diseases.2

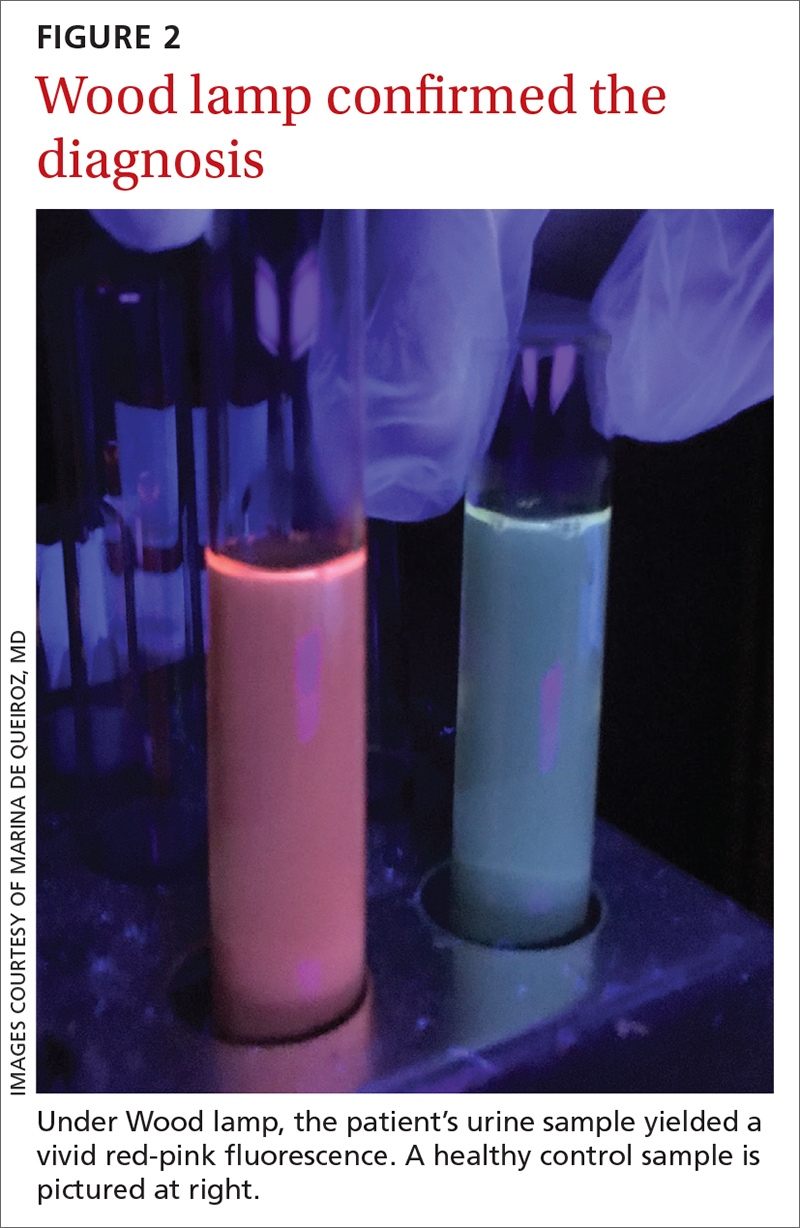

A Wood lamp can be a useful diagnostic first step

Plasma or urine porphyrin lab tests are the gold standard for PCT diagnosis. These tests can be followed by more specific tests (eg, porphyrin fractionation) to exclude other forms of porphyria. However, if plasma or urine porphyrin testing is not readily available, a good first step is a Wood lamp exam, which can be performed on urine or stool. (Plasma or urine porphyrin testing may ultimately be necessary if there is doubt about the diagnosis following the Wood lamp screening.) Histopathologic examination does not confirm the diagnosis of PCT4; however, it can be helpful in differential diagnosis.

Wood lamp is a source of long-wave UV light (320 to 400 nm), visualized as a purple or violet light. When porphyrins are present in a urine sample, a red-pink fluorescence may be seen.3,4,6 The Wood lamp examination should be performed in a completely dark room after the lamp has been warmed up for about 1 minute; time should be allowed for the clinician’s vision to adapt to the dark.6 There are no data regarding the sensitivity or specificity of the Wood lamp test in the diagnosis of PCT.

These conditions also cause skin fragility and photosensitivity

The differential diagnosis for PCT includes diseases that also cause skin fragility, blistering, or photosensitivity, such as pseudoporphyria, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA).3

Continue to: In pseudoporphyria

In pseudoporphyria, the clinical findings may be indistinguishable from PCT. Thus, the patient’s history will be especially important; suspect pseudoporphyria if the patient has a history of chronic renal failure or use of a photosensitizing drug.1,3

Bullous SLE usually manifests with systemic involvement and widespread, tense bullae. Serologic investigation will demonstrate the presence of antinuclear antibodies in high titers (> 1:80), as well as other circulating autoantibodies.

Skin lesions of EBA usually manifest with skin fragility and noninflammatory tense bullae in traumatized skin, such as the extensor surfaces of the hands, feet, and fingers.

None of the above-mentioned diagnoses manifest with hypertrichosis or red-pink fluorescent urine on Wood lamp, and results of porphyrin studies would be normal.3

Address triggers, provide treatment

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, steps must be taken to avoid triggering factors, such as any alcohol consumption, use of estrogen, sun exposure (until plasma porphyrin levels are normal), and potential sources of excessive iron intake.

Two therapeutic options are available for treating PCT—whether it’s sporadic or familial. Phlebotomy sessions reduce iron overload and iron depletion and may prevent the formation of a porphomethene inhibitor of UROD. The other treatment option is antimalarial agents—usually hydroxychloroquine— and is indicated for patients with lower serum ferritin levels.1-4 In patients with HCV-associated PCT, effective treatment of the infection has resulted in resolution of the PCT, in some cases.3

Treatment involving phlebotomy or an antimalarial agent can be stopped when plasma porphyrins reach normal levels.

Our patient was initially managed with 2 sessions of phlebotomy. He subsequently received treatment for the HCV infection at another hospital.

1. Handler NS, Handler MZ, Stephany MP, et. Porphyria cutanea tarda: an intriguing genetic disease and marker. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e106-e117.doi: 10.1111/ijd.13580

2. Lambrecht RW, Thapar M, Bonkovsky HL. Genetic aspects of porphyria cutanea tarda. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:99-108.doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960173

3. Callen JP. Hepatitis C viral infection and porphyria cutanea tarda. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:5-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.06.009

4. Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Porphyria cutanea tarda—when skin meets liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:735-745. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.07.002

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Pajares JM, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in porphyria cutanea tarda: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2003;39:620-627.doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00346-5

6. Asawanonda P, Taylor CR. Wood’s light in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:801-807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00794.x

A 55-YEAR-OLD MAN with hypertension and untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) was referred to the Dermatology Clinic after reporting a 2-year history of photosensitivity and intermittent episodes of blistering and scars on the dorsal side of his hands and feet. No alcohol consumption or drug use was reported.

Physical examination revealed small and shallow erosions on the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet (but no visible blisters) and milium cysts (FIGURE 1A). Additionally, hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation were observed in the zygomatic areas (FIGURE 1B). Complete blood count and kidney function test results were within normal ranges. Liver function tests showed slightly elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase (79 U/L; normal range, 0-41 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (62 U/L; normal range, 0-40 U/L), and ferritin (121 ng/mL; normal range, 30-100 ng/mL). Serologies for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B virus were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

The porphyrias are a group of metabolic diseases that affect the heme biosynthesis. They can be classified into 1 of 3 groups, according to clinical features:

- acute hepatic porphyrias, with neurovisceral symptoms (eg, acute intermittent porphyria),

- nonblistering cutaneous porphyrias, with severe photosensitivity but without bullae formation (eg, erythropoietic protoporphyria), or

- blistering cutaneous porphyrias (eg, PCT, hepatoerythropoietic porphyria, and variegate porphyria).

PCT is the most common type of porphyria, with a global prevalence of 1 per 10,000 people.1,2 It affects adults after the third or fourth decade of life.

PCT involves dysfunction of the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase enzyme (UROD), the fifth enzyme in heme biosynthesis, which catalyzes the conversion of uroporphyrinogen to coproporphyrinogen. This dysfunction causes the accumulation of porphyrinogens that are auto-oxidized to photosensitizing porphyrins.1-4 PCT can be classified as “sporadic” or “familial” based on the absence or presence of UROD mutation. Approximately 80% of cases of PCT are sporadic.2

In sporadic PCT, triggers for UROD dysfunction include alcohol use, use of estrogens, hemochromatosis or iron overload, chronic HCV infection, and HIV infection.1-4 HCV (which this patient had) is the most common infection associated with sporadic PCT, with a prevalence of about 50% among these patients.5

Continue to: Dermatologic manifestations of PCT

Dermatologic manifestations of PCT include photosensitivity, skin fragility, vesicles, bullae, erosions, and crusts observed in sun-exposed areas. A nonvirilizing type of hypertrichosis may appear prominently on the temples and the cheeks.2-4 After blisters rupture, atrophy and scarring occur. Milia cysts can form on the dorsal side of the hands and fingers. Less common manifestations include pruritus, scarring alopecia, sclerodermatous changes, and periorbital purple-red suffusion.

Hepatic involvement is demonstrated with elevated serum transaminases and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Hepatomegaly is common, and cirrhosis manifests in 30% to 40% of patients.2-5 On liver biopsy, some degree of siderosis is found in 80% of patients with PCT, and most of them have increased levels of serum iron. The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with PCT is greater than in patients with other liver diseases.2

A Wood lamp can be a useful diagnostic first step

Plasma or urine porphyrin lab tests are the gold standard for PCT diagnosis. These tests can be followed by more specific tests (eg, porphyrin fractionation) to exclude other forms of porphyria. However, if plasma or urine porphyrin testing is not readily available, a good first step is a Wood lamp exam, which can be performed on urine or stool. (Plasma or urine porphyrin testing may ultimately be necessary if there is doubt about the diagnosis following the Wood lamp screening.) Histopathologic examination does not confirm the diagnosis of PCT4; however, it can be helpful in differential diagnosis.

Wood lamp is a source of long-wave UV light (320 to 400 nm), visualized as a purple or violet light. When porphyrins are present in a urine sample, a red-pink fluorescence may be seen.3,4,6 The Wood lamp examination should be performed in a completely dark room after the lamp has been warmed up for about 1 minute; time should be allowed for the clinician’s vision to adapt to the dark.6 There are no data regarding the sensitivity or specificity of the Wood lamp test in the diagnosis of PCT.

These conditions also cause skin fragility and photosensitivity

The differential diagnosis for PCT includes diseases that also cause skin fragility, blistering, or photosensitivity, such as pseudoporphyria, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA).3

Continue to: In pseudoporphyria

In pseudoporphyria, the clinical findings may be indistinguishable from PCT. Thus, the patient’s history will be especially important; suspect pseudoporphyria if the patient has a history of chronic renal failure or use of a photosensitizing drug.1,3

Bullous SLE usually manifests with systemic involvement and widespread, tense bullae. Serologic investigation will demonstrate the presence of antinuclear antibodies in high titers (> 1:80), as well as other circulating autoantibodies.

Skin lesions of EBA usually manifest with skin fragility and noninflammatory tense bullae in traumatized skin, such as the extensor surfaces of the hands, feet, and fingers.

None of the above-mentioned diagnoses manifest with hypertrichosis or red-pink fluorescent urine on Wood lamp, and results of porphyrin studies would be normal.3

Address triggers, provide treatment

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, steps must be taken to avoid triggering factors, such as any alcohol consumption, use of estrogen, sun exposure (until plasma porphyrin levels are normal), and potential sources of excessive iron intake.

Two therapeutic options are available for treating PCT—whether it’s sporadic or familial. Phlebotomy sessions reduce iron overload and iron depletion and may prevent the formation of a porphomethene inhibitor of UROD. The other treatment option is antimalarial agents—usually hydroxychloroquine— and is indicated for patients with lower serum ferritin levels.1-4 In patients with HCV-associated PCT, effective treatment of the infection has resulted in resolution of the PCT, in some cases.3

Treatment involving phlebotomy or an antimalarial agent can be stopped when plasma porphyrins reach normal levels.

Our patient was initially managed with 2 sessions of phlebotomy. He subsequently received treatment for the HCV infection at another hospital.

A 55-YEAR-OLD MAN with hypertension and untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) was referred to the Dermatology Clinic after reporting a 2-year history of photosensitivity and intermittent episodes of blistering and scars on the dorsal side of his hands and feet. No alcohol consumption or drug use was reported.

Physical examination revealed small and shallow erosions on the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet (but no visible blisters) and milium cysts (FIGURE 1A). Additionally, hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation were observed in the zygomatic areas (FIGURE 1B). Complete blood count and kidney function test results were within normal ranges. Liver function tests showed slightly elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase (79 U/L; normal range, 0-41 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (62 U/L; normal range, 0-40 U/L), and ferritin (121 ng/mL; normal range, 30-100 ng/mL). Serologies for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B virus were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

The porphyrias are a group of metabolic diseases that affect the heme biosynthesis. They can be classified into 1 of 3 groups, according to clinical features:

- acute hepatic porphyrias, with neurovisceral symptoms (eg, acute intermittent porphyria),

- nonblistering cutaneous porphyrias, with severe photosensitivity but without bullae formation (eg, erythropoietic protoporphyria), or

- blistering cutaneous porphyrias (eg, PCT, hepatoerythropoietic porphyria, and variegate porphyria).

PCT is the most common type of porphyria, with a global prevalence of 1 per 10,000 people.1,2 It affects adults after the third or fourth decade of life.

PCT involves dysfunction of the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase enzyme (UROD), the fifth enzyme in heme biosynthesis, which catalyzes the conversion of uroporphyrinogen to coproporphyrinogen. This dysfunction causes the accumulation of porphyrinogens that are auto-oxidized to photosensitizing porphyrins.1-4 PCT can be classified as “sporadic” or “familial” based on the absence or presence of UROD mutation. Approximately 80% of cases of PCT are sporadic.2

In sporadic PCT, triggers for UROD dysfunction include alcohol use, use of estrogens, hemochromatosis or iron overload, chronic HCV infection, and HIV infection.1-4 HCV (which this patient had) is the most common infection associated with sporadic PCT, with a prevalence of about 50% among these patients.5

Continue to: Dermatologic manifestations of PCT

Dermatologic manifestations of PCT include photosensitivity, skin fragility, vesicles, bullae, erosions, and crusts observed in sun-exposed areas. A nonvirilizing type of hypertrichosis may appear prominently on the temples and the cheeks.2-4 After blisters rupture, atrophy and scarring occur. Milia cysts can form on the dorsal side of the hands and fingers. Less common manifestations include pruritus, scarring alopecia, sclerodermatous changes, and periorbital purple-red suffusion.

Hepatic involvement is demonstrated with elevated serum transaminases and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Hepatomegaly is common, and cirrhosis manifests in 30% to 40% of patients.2-5 On liver biopsy, some degree of siderosis is found in 80% of patients with PCT, and most of them have increased levels of serum iron. The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with PCT is greater than in patients with other liver diseases.2

A Wood lamp can be a useful diagnostic first step

Plasma or urine porphyrin lab tests are the gold standard for PCT diagnosis. These tests can be followed by more specific tests (eg, porphyrin fractionation) to exclude other forms of porphyria. However, if plasma or urine porphyrin testing is not readily available, a good first step is a Wood lamp exam, which can be performed on urine or stool. (Plasma or urine porphyrin testing may ultimately be necessary if there is doubt about the diagnosis following the Wood lamp screening.) Histopathologic examination does not confirm the diagnosis of PCT4; however, it can be helpful in differential diagnosis.

Wood lamp is a source of long-wave UV light (320 to 400 nm), visualized as a purple or violet light. When porphyrins are present in a urine sample, a red-pink fluorescence may be seen.3,4,6 The Wood lamp examination should be performed in a completely dark room after the lamp has been warmed up for about 1 minute; time should be allowed for the clinician’s vision to adapt to the dark.6 There are no data regarding the sensitivity or specificity of the Wood lamp test in the diagnosis of PCT.

These conditions also cause skin fragility and photosensitivity

The differential diagnosis for PCT includes diseases that also cause skin fragility, blistering, or photosensitivity, such as pseudoporphyria, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA).3

Continue to: In pseudoporphyria

In pseudoporphyria, the clinical findings may be indistinguishable from PCT. Thus, the patient’s history will be especially important; suspect pseudoporphyria if the patient has a history of chronic renal failure or use of a photosensitizing drug.1,3

Bullous SLE usually manifests with systemic involvement and widespread, tense bullae. Serologic investigation will demonstrate the presence of antinuclear antibodies in high titers (> 1:80), as well as other circulating autoantibodies.

Skin lesions of EBA usually manifest with skin fragility and noninflammatory tense bullae in traumatized skin, such as the extensor surfaces of the hands, feet, and fingers.

None of the above-mentioned diagnoses manifest with hypertrichosis or red-pink fluorescent urine on Wood lamp, and results of porphyrin studies would be normal.3

Address triggers, provide treatment

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, steps must be taken to avoid triggering factors, such as any alcohol consumption, use of estrogen, sun exposure (until plasma porphyrin levels are normal), and potential sources of excessive iron intake.

Two therapeutic options are available for treating PCT—whether it’s sporadic or familial. Phlebotomy sessions reduce iron overload and iron depletion and may prevent the formation of a porphomethene inhibitor of UROD. The other treatment option is antimalarial agents—usually hydroxychloroquine— and is indicated for patients with lower serum ferritin levels.1-4 In patients with HCV-associated PCT, effective treatment of the infection has resulted in resolution of the PCT, in some cases.3

Treatment involving phlebotomy or an antimalarial agent can be stopped when plasma porphyrins reach normal levels.

Our patient was initially managed with 2 sessions of phlebotomy. He subsequently received treatment for the HCV infection at another hospital.

1. Handler NS, Handler MZ, Stephany MP, et. Porphyria cutanea tarda: an intriguing genetic disease and marker. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e106-e117.doi: 10.1111/ijd.13580

2. Lambrecht RW, Thapar M, Bonkovsky HL. Genetic aspects of porphyria cutanea tarda. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:99-108.doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960173

3. Callen JP. Hepatitis C viral infection and porphyria cutanea tarda. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:5-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.06.009

4. Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Porphyria cutanea tarda—when skin meets liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:735-745. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.07.002

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Pajares JM, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in porphyria cutanea tarda: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2003;39:620-627.doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00346-5

6. Asawanonda P, Taylor CR. Wood’s light in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:801-807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00794.x

1. Handler NS, Handler MZ, Stephany MP, et. Porphyria cutanea tarda: an intriguing genetic disease and marker. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e106-e117.doi: 10.1111/ijd.13580

2. Lambrecht RW, Thapar M, Bonkovsky HL. Genetic aspects of porphyria cutanea tarda. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:99-108.doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960173

3. Callen JP. Hepatitis C viral infection and porphyria cutanea tarda. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:5-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.06.009

4. Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Porphyria cutanea tarda—when skin meets liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:735-745. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.07.002

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Pajares JM, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in porphyria cutanea tarda: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2003;39:620-627.doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00346-5

6. Asawanonda P, Taylor CR. Wood’s light in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:801-807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00794.x

Diffuse annular lesions

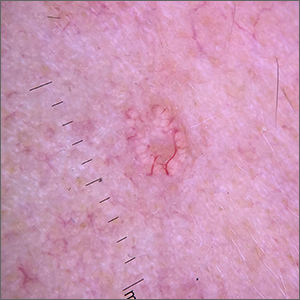

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

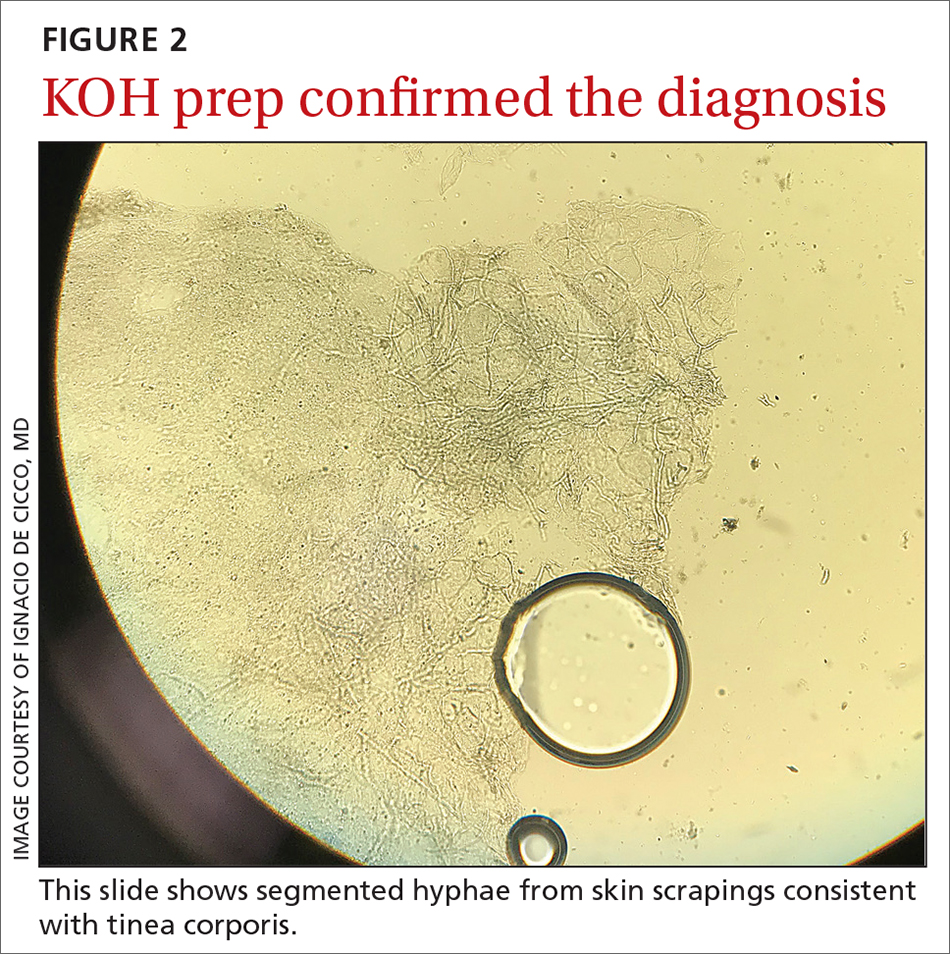

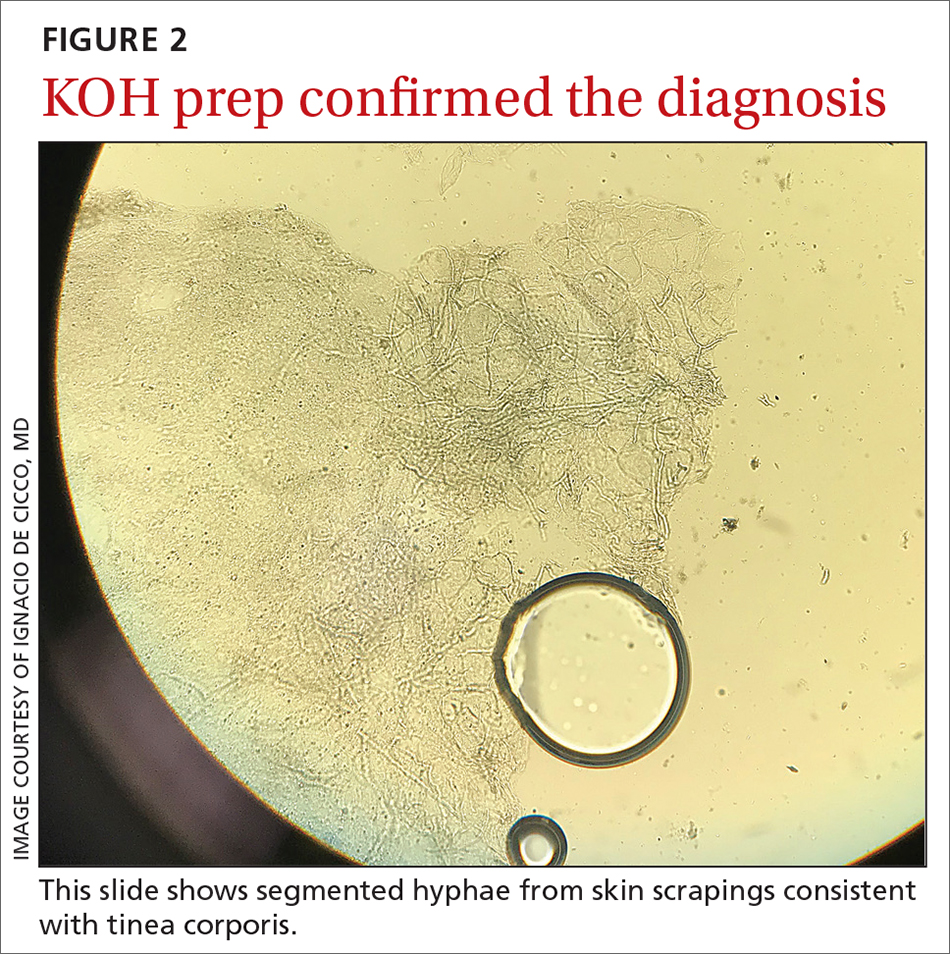

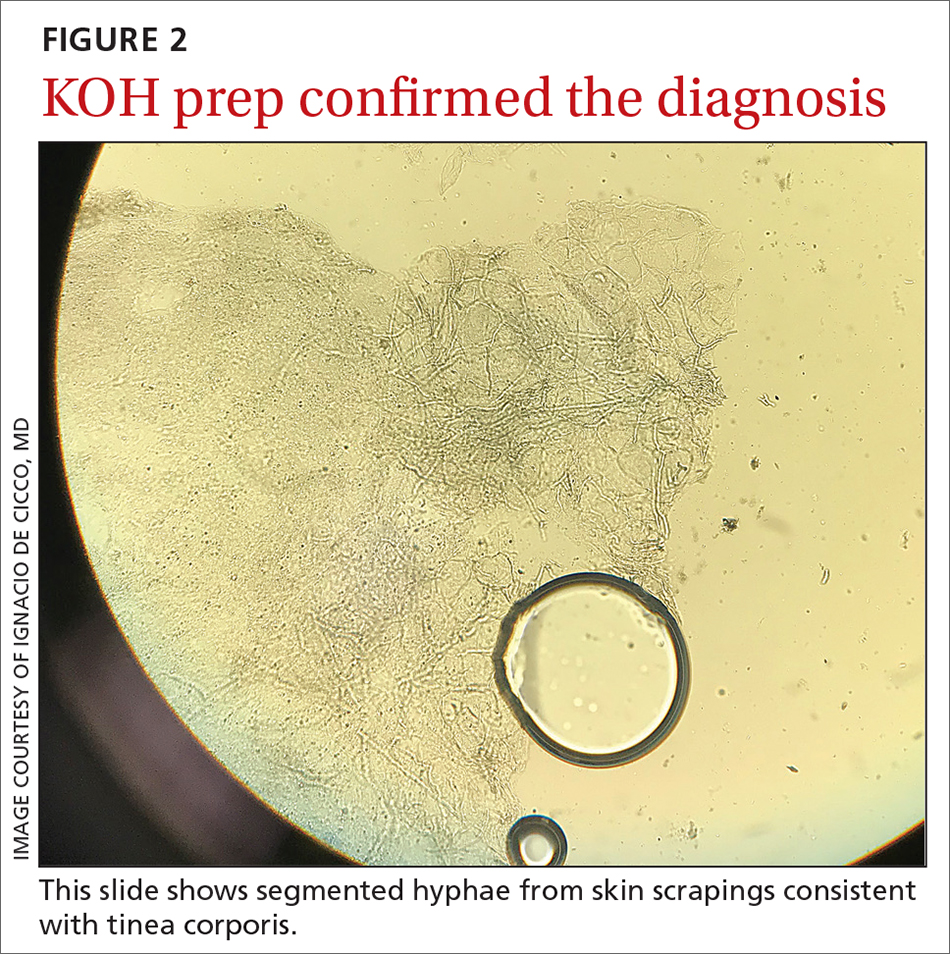

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

A 24-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of guttate psoriasis, for which she was taking adalimumab, presented with a 2-week history of diffuse papules and plaques on her neck, back, torso, and upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). She said that the lesions were pruritic and seemed similar to those that erupted during past outbreaks of psoriasis—although they were more numerous and progressive. So, the patient (a nurse) decided to take her biweekly dose (40 mg) of adalimumab 1 week early. After administration, the rash significantly worsened, spreading to the rest of her trunk and extremities.

Physical exam was notable for multiple erythematous papules and plaques with central clearing and light peripheral scaling on both arms and legs, as well as her chest and back. The patient also indicated she’d adopted a stray cat 2 weeks prior. Given the patient’s pet exposure and the annular nature of the lesions, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was done.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea corporis

The KOH preparation was positive for hyphae in 4 separate sites (trunk, left arm, left leg, and left neck), confirming the diagnosis of severe extensive tinea corporis (FIGURE 2).

Dermatophyte (tinea) infections are caused by fungi that invade and reproduce in the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytes, which include the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton, are the most common cause of superficial mycotic infections. As of 2016, the worldwide prevalence of superficial mycotic infections was 20% to 25%.1 Tinea corporis can result from contact with people, animals, or soil. Infections resulting from animal-to-human contact are often transmitted by domestic animals. In this case, the patient’s exposure was from her new cat.

Tinea corporis classically manifests as pruritic, erythematous patches or plaques with central clearing, giving it an annular appearance. The response to a tinea infection depends on the immune system of the host and can range in severity from superficial to severe.2 There are 2 forms of severe dermatophytosis: invasive, which involves localized perifollicular sites or deep dermatophytosis, and extensive, which is confined to the stratum corneum but results in numerous lesions.3

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is commonly confirmed using direct microscopic examination with 10% to 20% KOH preparation, which will show branching and septate hyphal filaments.4

Several conditions with annular lesions comprise the differential

The findings of pruritic annular erythematous lesions on the patient’s neck, chest, trunk, and bilateral extremities led the patient to suspect this was a worsening case of her guttate psoriasis. Other possible diagnoses included pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and secondary syphilis.

Continue to: Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis would not typically progress during treatment with adalimumab, although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have been associated with worsening psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis manifests with small, pink to red, scaly raindrop-shaped patches over the trunk and extremities.

Pityriasis rosea, a rash that resembles branches of a Christmas tree, was strongly considered given the appearance of the lesions on the patient’s back. It commonly manifests as round to oval lesions with a subtle advancing border and central fine scaling, similar in shape and color to the lesions seen in tinea corporis.

SCLE has been associated with use of TNF inhibitors, but our patient had no other lupus-like symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headaches, or joint pain. SCLE lesions are often annular with raised pink to red borders similar in appearance to tinea corporis.

Secondary syphilis was ruled out in this patient because she had a negative rapid plasma reagin test. Secondary syphilis most commonly manifests with diffuse, nonpruritic pink to red-brown lesions on the palms and soles of patients. Patients often have prodromal symptoms that include fever, weight loss, myalgias, headache, and sore throat.

Terbinafine, Yes, but for how long?

Historically, terbinafine has been prescribed at 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks for extensive tinea corporis. However, recent studies in India suggest that terbinafine should be dosed at 250 mg twice daily, with longer durations of treatment, due to resistance.5 In the United States, it is reasonable to prescribe oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks and then re-evaluate the patient in a case of extensive tinea corporis.

Other oral antifungals that can effectively treat extensive tinea corporis include itraconazole, fluconazole, and griseofulvin.1 Itraconazole and terbinafine are equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea corporis, although itraconazole is significantly more expensive.6 Furthermore, a recent study found that combination therapy with oral terbinafine and itraconazole is as safe as monotherapy and is an option when terbinafine resistance is suspected.7

Our patient was initially started on oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. After the first dose, the patient requested a change in medication because there was no improvement in the rash. The patient was then prescribed oral fluconazole 300 mg daily and the tinea cleared after 2 months of daily therapy. (We surmise the treatment course may have been prolonged due to the possible immunosuppressant effects of adalimumab.) At the completion of treatment for the tinea corporis, the patient was restarted on adalimumab 40 mg biweekly for her psoriasis.

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835

1. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77-86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178099

2. Weitzman I, Summerbell RC. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbial Rev. 1995:8:240-259. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.240

3. Rouzaud C, Hay R, Chosidow O, et al. Severe dermatophytosis and acquired or innate immunodeficiency: a review. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;2:4. doi: 10.3390/jof2010004

4. Kurade SM, Amladi SA, Miskeen AK. Skin scraping and a potassium hydroxide mount. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:238-41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25794

5. Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;132:103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255

6. Bhatia A, Kanish B, Badyal DK, et al. Efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in treatment of dermatophytic infection of skin - a prospective, randomized comparative study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51:116-119.

7. Sharma P, Bhalla M, Thami GP, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of oral terbinafine and itraconazole combination therapy in the management of dermatophytosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:749-753. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1612835

Chest pain and difficulty swallowing

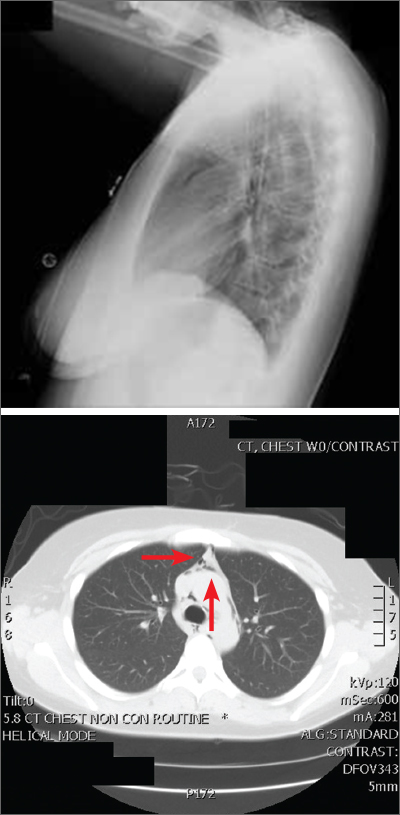

The posteroanterior (PA) and lateral view CXRs, as well as the CT scan, revealed the presence of retrosternal air and confirmed the patient’s diagnosis of pneumomediastinum.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by the Hamman sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

Pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition. Thus, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home. If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation.3 If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3

The patient underwent both swallow studies, and they were negative. This patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in the pneumomediastinum. Once the patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged (after a 3-day hospitalization) with close follow-up. One week later, her pain had almost entirely resolved.

This case was adapted from: Gawrys B, Shaha D. Pleuritic chest pain and globus pharyngeus. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:305-307.

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039-2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl13104

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.023

The posteroanterior (PA) and lateral view CXRs, as well as the CT scan, revealed the presence of retrosternal air and confirmed the patient’s diagnosis of pneumomediastinum.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by the Hamman sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

Pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition. Thus, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home. If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation.3 If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3

The patient underwent both swallow studies, and they were negative. This patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in the pneumomediastinum. Once the patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged (after a 3-day hospitalization) with close follow-up. One week later, her pain had almost entirely resolved.

This case was adapted from: Gawrys B, Shaha D. Pleuritic chest pain and globus pharyngeus. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:305-307.

The posteroanterior (PA) and lateral view CXRs, as well as the CT scan, revealed the presence of retrosternal air and confirmed the patient’s diagnosis of pneumomediastinum.

Pneumomediastinum—the presence of free air in the mediastinum—can develop spontaneously (as was the case with our patient) or in response to trauma. Common causes include respiratory diseases such as asthma, and trauma to the esophagus secondary to mechanical ventilation, endoscopy, and excessive vomiting.1 Other possible causes include respiratory infections, foreign body aspiration, recent dental extraction, diabetic ketoacidosis, esophageal perforation, barotrauma (due to activities such as flying or scuba diving), and use of illicit drugs.1

Patients with pneumomediastinum often complain of retrosternal, pleuritic pain that radiates to their back, shoulders, and arms. They may also have difficulty swallowing (globus pharyngeus), a nasal voice, and/or dyspnea. Physical findings can include subcutaneous emphysema in the neck and supraclavicular fossa as manifested by the Hamman sign (a precordial “crunching” sound heard during systole), a fever, and distended neck veins.1

Diagnosis is made by CXR and/or chest CT. On a CXR, retrosternal air is best seen in the lateral projection. Small amounts of air can appear as linear lucencies outlining mediastinal contours. This air can be seen under the skin, surrounding the pericardium, around the pulmonary and/or aortic vasculature, and/or between the parietal pleura and diaphragm.2 A pleural effusion—particularly on the patient’s left side—should raise concern for esophageal perforation.

Pneumomediastinum is generally a self-limiting condition. Thus, patients who don’t have severe symptoms, such as respiratory distress or signs of inflammation, should be observed for 2 days, managed with rest and pain control, and discharged home. If severe symptoms or inflammatory signs are present, a Gastrografin swallow study is recommended to rule out esophageal perforation.3 If the result of this test is abnormal, a follow-up study with barium is recommended.3

The patient underwent both swallow studies, and they were negative. This patient received subsequent serial CXRs that showed improvement in the pneumomediastinum. Once the patient’s pain was well controlled with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, she was discharged (after a 3-day hospitalization) with close follow-up. One week later, her pain had almost entirely resolved.

This case was adapted from: Gawrys B, Shaha D. Pleuritic chest pain and globus pharyngeus. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:305-307.

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039-2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl13104

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.023

1. Park DE, Vallieres E. Pneumomediastinum and mediastinitis. In: Mason R, Broaddus V, Murray J, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2039-2068.

2. Zylak CM, Standen JR, Barnes GR, et al. Pneumomediastinum revisited. Radiographics. 2000;20:1043-1057. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl13104

3. Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:1329-1334. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.023

Nail dystrophy and foot pain

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Smith FJD, Hansen CD, Hull PR, et al. Pachyonychia congenita. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2006. Updated November 30, 2017. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1280/

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Smith FJD, Hansen CD, Hull PR, et al. Pachyonychia congenita. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2006. Updated November 30, 2017. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1280/

1. Smith FJD, Hansen CD, Hull PR, et al. Pachyonychia congenita. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2006. Updated November 30, 2017. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1280/

Widespread rash in toddler

This patient was given a diagnosis of Gianotti Crosti syndrome (GCS; also called infantile acrodermatitis of childhood), which is a self-resolving (often dramatic) dermatosis triggered by a viral infection or immunization. Patients with this syndrome develop papules, vesicles, and plaques on their face, hands, feet, and extremities a week (or more) after having a viral illness or receiving an immunization. In patients with darker skin types, lesions may appear purple to brown rather than bright red to red/orange. The syndrome typically occurs in children between the ages of 1 to 4 years, but almost all patients are under the age of 15.1 Scratching and sleep disturbance are common. The condition typically resolves on its own after 3 or 4 weeks.

Globally, the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most common cause of GCS.1 Other reported triggering viruses include hepatitis A and C, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, HIV, parainfluenza viruses, parvoviruses, rubella, and COVID-19.2

Since the cause of this patient’s case of GCS was likely linked to a viral infection that produced the loose stools in a population with low-HBV risk, no further serologic testing was performed. Serologic testing may have been necessary if other infections, disease risks, or symptoms were identified. To relieve itching, topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream was prescribed for use once to twice daily on the extremities and hydrocortisone 1% cream was prescribed once to twice daily for use on the child’s face. At the 6-week follow-up visit, the lesions had resolved; light pink discoloration remained but was expected to further fade. In patients with darker skin, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation may take several months to resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.033

2. Berná-Rico ED, Álvarez-Pinheiro C, Burgos-Blasco P, et al. A Gianotti-Crosti-like eruption in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e15071. Doi:10.1111/dth.15071

This patient was given a diagnosis of Gianotti Crosti syndrome (GCS; also called infantile acrodermatitis of childhood), which is a self-resolving (often dramatic) dermatosis triggered by a viral infection or immunization. Patients with this syndrome develop papules, vesicles, and plaques on their face, hands, feet, and extremities a week (or more) after having a viral illness or receiving an immunization. In patients with darker skin types, lesions may appear purple to brown rather than bright red to red/orange. The syndrome typically occurs in children between the ages of 1 to 4 years, but almost all patients are under the age of 15.1 Scratching and sleep disturbance are common. The condition typically resolves on its own after 3 or 4 weeks.

Globally, the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most common cause of GCS.1 Other reported triggering viruses include hepatitis A and C, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, HIV, parainfluenza viruses, parvoviruses, rubella, and COVID-19.2

Since the cause of this patient’s case of GCS was likely linked to a viral infection that produced the loose stools in a population with low-HBV risk, no further serologic testing was performed. Serologic testing may have been necessary if other infections, disease risks, or symptoms were identified. To relieve itching, topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream was prescribed for use once to twice daily on the extremities and hydrocortisone 1% cream was prescribed once to twice daily for use on the child’s face. At the 6-week follow-up visit, the lesions had resolved; light pink discoloration remained but was expected to further fade. In patients with darker skin, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation may take several months to resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

This patient was given a diagnosis of Gianotti Crosti syndrome (GCS; also called infantile acrodermatitis of childhood), which is a self-resolving (often dramatic) dermatosis triggered by a viral infection or immunization. Patients with this syndrome develop papules, vesicles, and plaques on their face, hands, feet, and extremities a week (or more) after having a viral illness or receiving an immunization. In patients with darker skin types, lesions may appear purple to brown rather than bright red to red/orange. The syndrome typically occurs in children between the ages of 1 to 4 years, but almost all patients are under the age of 15.1 Scratching and sleep disturbance are common. The condition typically resolves on its own after 3 or 4 weeks.

Globally, the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most common cause of GCS.1 Other reported triggering viruses include hepatitis A and C, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, HIV, parainfluenza viruses, parvoviruses, rubella, and COVID-19.2

Since the cause of this patient’s case of GCS was likely linked to a viral infection that produced the loose stools in a population with low-HBV risk, no further serologic testing was performed. Serologic testing may have been necessary if other infections, disease risks, or symptoms were identified. To relieve itching, topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream was prescribed for use once to twice daily on the extremities and hydrocortisone 1% cream was prescribed once to twice daily for use on the child’s face. At the 6-week follow-up visit, the lesions had resolved; light pink discoloration remained but was expected to further fade. In patients with darker skin, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation may take several months to resolve.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.033

2. Berná-Rico ED, Álvarez-Pinheiro C, Burgos-Blasco P, et al. A Gianotti-Crosti-like eruption in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e15071. Doi:10.1111/dth.15071

1. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.033