User login

Coalescing skin-colored papules

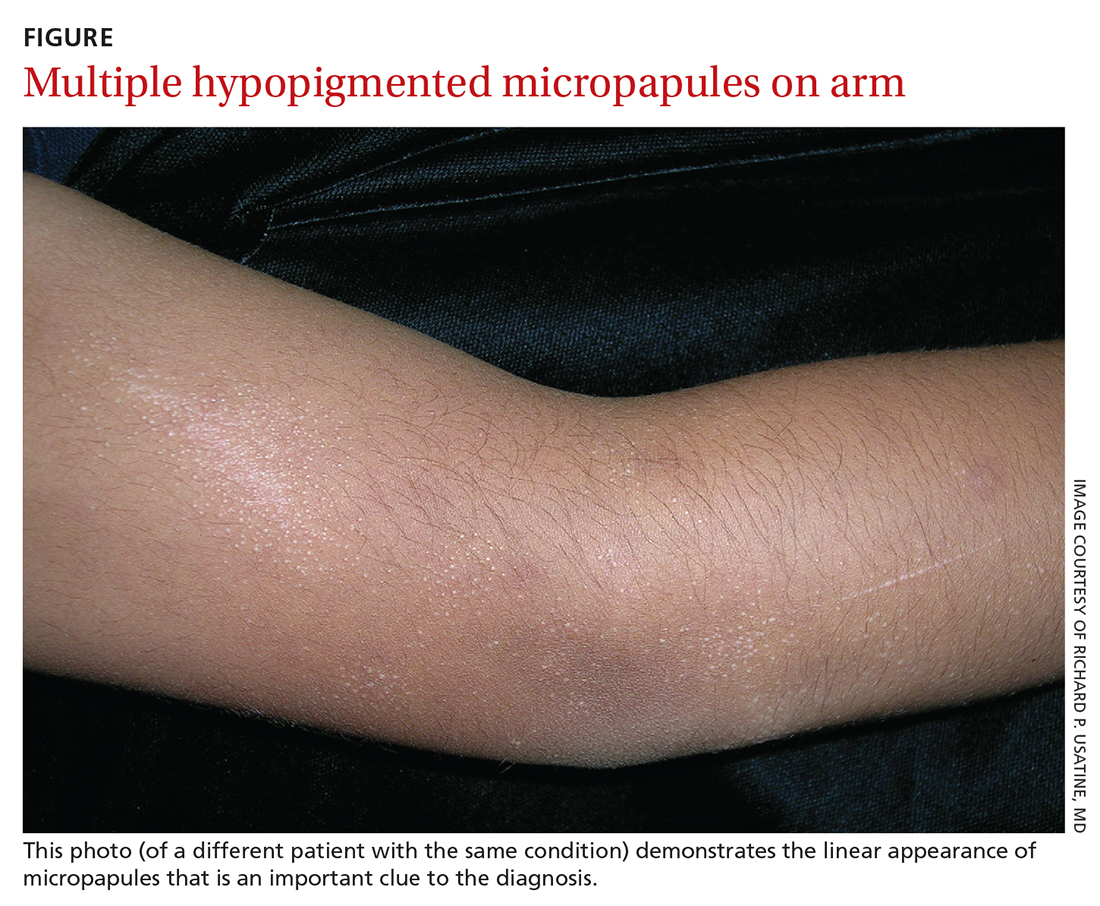

AN 8-YEAR-OLD BOY was evaluated by his family physician for a widespread rash that had first appeared on his arms 4 months earlier. Physical examination revealed 1- to 2-mm hypopigmented, smooth, and dome-shaped papules in clusters and linear arrays on the child’s back, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of both arms (FIGURE). There was no tenderness to palpation of the affected areas, but the patient complained of pruritus. Otherwise, he was in good health.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen nitidus

This clinical manifestation of multiple, hypopigmented, pinhead-sized papules is most consistent with the diagnosis of lichen nitidus.

A rare and chronic inflammatory skin condition, lichen nitidus is characterized by numerous small, skin-colored papules that are often arranged in clusters on the upper extremities, the genitalia, and the anterior trunk.1 The papules are less likely to occur on the face, lower extremities, palms, and soles. Oral mucosal and nail involvement are rare. The condition is usually asymptomatic but can sometimes be associated with pruritus.

Lichen nitidus occurs more frequently in children or young adults and has a female predominance.1 It does not exhibit a predilection of any race.2 The etiology and pathogenesis of lichen nitidus remain unclear. Genetic factors have been proposed as a potential cause; it has also been reported to be associated with Down syndrome.3

Making the Dx with dermoscopy, skin biopsy

Dermoscopy is a useful technique for diagnosing lichen nitidus. Dermoscopic features of lichen nitidus include white, well-demarcated circular areas with a brown shadow.4 Skin biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis. Lichen nitidus has a distinct histopathologic “ball and claw” appearance of rete ridges clutching a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.1

Consider these common conditions in the differential

The differential diagnosis includes lichen spinulosus, papular eczema, lichen planus, keratosis pilaris, and verruca plana (flat warts).

Continue to: Lichen spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus lesions are similar in appearance to lichen nitidus but are grouped in patches on the neck, arms, abdomen, and buttocks.1 The Koebner phenomenon is not typically present. Lichen spinulosus lesions consist of follicular papules that may exhibit a central keratotic plug.

Papular eczema lesions lack the uniform and discrete appearance observed in lichen nitidus. Pruritus is also more likely to be present in papular eczema.

Lichen planus lesions are typically violaceous, flat, and larger in size than lichen nitidus (measuring 1 mm to 1 cm), and have characteristic Wickham striae. Oral involvement is also more suggestive of lichen planus.

Keratosis pilaris is distinguished by its much more common occurrence and perifollicular erythema.

Verruca plana, in contrast to lichen nitidus, are typically pink, flat-topped lesions. They are also larger in size (2 mm to 5 mm).

Continue to: Topical treatment can help manage the condition

Topical treatment can help manage the condition

Most patients experience spontaneous resolution of lesions within several years; treatment is primarily for symptomatic or cosmetic purposes. When pruritus is present, topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines may help (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oral hydroxyzine). Topical calcineurin inhibitors, such as pimecrolimus cream, have also been reported as an effective therapy in children with lichen nitidus.1 In patients with generalized lichen nitidus who have not responded to topical corticosteroids, phototherapy can be used.5 There are no randomized controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of different types of treatments.

In this case, the patient was advised to start using an over-the-counter topical steroid, such as 1% hydrocortisone cream, to help control pruritus. He was scheduled for a follow-up appointment in 3 months.

1. Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Inc;2008:167-170.

2. Lapins NA, Willoughby C, Helwig EB. Lichen nitidus. A study of forty-three cases. Cutis. 1978;21:634-637.

3. Botelho LFF, de Magalhães JPJ, Ogawa MM, et al. Generalized Lichen nitidus associated with Down’s syndrome: case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:466-468. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000300018

4. Malakar S, Save S, Mehta P. Brown shadow in lichen nitidus: a dermoscopic marker! Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:479-480. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_338_17

5. Synakiewicz J, Polańska A, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:488-490. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.63890

AN 8-YEAR-OLD BOY was evaluated by his family physician for a widespread rash that had first appeared on his arms 4 months earlier. Physical examination revealed 1- to 2-mm hypopigmented, smooth, and dome-shaped papules in clusters and linear arrays on the child’s back, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of both arms (FIGURE). There was no tenderness to palpation of the affected areas, but the patient complained of pruritus. Otherwise, he was in good health.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen nitidus

This clinical manifestation of multiple, hypopigmented, pinhead-sized papules is most consistent with the diagnosis of lichen nitidus.

A rare and chronic inflammatory skin condition, lichen nitidus is characterized by numerous small, skin-colored papules that are often arranged in clusters on the upper extremities, the genitalia, and the anterior trunk.1 The papules are less likely to occur on the face, lower extremities, palms, and soles. Oral mucosal and nail involvement are rare. The condition is usually asymptomatic but can sometimes be associated with pruritus.

Lichen nitidus occurs more frequently in children or young adults and has a female predominance.1 It does not exhibit a predilection of any race.2 The etiology and pathogenesis of lichen nitidus remain unclear. Genetic factors have been proposed as a potential cause; it has also been reported to be associated with Down syndrome.3

Making the Dx with dermoscopy, skin biopsy

Dermoscopy is a useful technique for diagnosing lichen nitidus. Dermoscopic features of lichen nitidus include white, well-demarcated circular areas with a brown shadow.4 Skin biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis. Lichen nitidus has a distinct histopathologic “ball and claw” appearance of rete ridges clutching a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.1

Consider these common conditions in the differential

The differential diagnosis includes lichen spinulosus, papular eczema, lichen planus, keratosis pilaris, and verruca plana (flat warts).

Continue to: Lichen spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus lesions are similar in appearance to lichen nitidus but are grouped in patches on the neck, arms, abdomen, and buttocks.1 The Koebner phenomenon is not typically present. Lichen spinulosus lesions consist of follicular papules that may exhibit a central keratotic plug.

Papular eczema lesions lack the uniform and discrete appearance observed in lichen nitidus. Pruritus is also more likely to be present in papular eczema.

Lichen planus lesions are typically violaceous, flat, and larger in size than lichen nitidus (measuring 1 mm to 1 cm), and have characteristic Wickham striae. Oral involvement is also more suggestive of lichen planus.

Keratosis pilaris is distinguished by its much more common occurrence and perifollicular erythema.

Verruca plana, in contrast to lichen nitidus, are typically pink, flat-topped lesions. They are also larger in size (2 mm to 5 mm).

Continue to: Topical treatment can help manage the condition

Topical treatment can help manage the condition

Most patients experience spontaneous resolution of lesions within several years; treatment is primarily for symptomatic or cosmetic purposes. When pruritus is present, topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines may help (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oral hydroxyzine). Topical calcineurin inhibitors, such as pimecrolimus cream, have also been reported as an effective therapy in children with lichen nitidus.1 In patients with generalized lichen nitidus who have not responded to topical corticosteroids, phototherapy can be used.5 There are no randomized controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of different types of treatments.

In this case, the patient was advised to start using an over-the-counter topical steroid, such as 1% hydrocortisone cream, to help control pruritus. He was scheduled for a follow-up appointment in 3 months.

AN 8-YEAR-OLD BOY was evaluated by his family physician for a widespread rash that had first appeared on his arms 4 months earlier. Physical examination revealed 1- to 2-mm hypopigmented, smooth, and dome-shaped papules in clusters and linear arrays on the child’s back, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of both arms (FIGURE). There was no tenderness to palpation of the affected areas, but the patient complained of pruritus. Otherwise, he was in good health.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen nitidus

This clinical manifestation of multiple, hypopigmented, pinhead-sized papules is most consistent with the diagnosis of lichen nitidus.

A rare and chronic inflammatory skin condition, lichen nitidus is characterized by numerous small, skin-colored papules that are often arranged in clusters on the upper extremities, the genitalia, and the anterior trunk.1 The papules are less likely to occur on the face, lower extremities, palms, and soles. Oral mucosal and nail involvement are rare. The condition is usually asymptomatic but can sometimes be associated with pruritus.

Lichen nitidus occurs more frequently in children or young adults and has a female predominance.1 It does not exhibit a predilection of any race.2 The etiology and pathogenesis of lichen nitidus remain unclear. Genetic factors have been proposed as a potential cause; it has also been reported to be associated with Down syndrome.3

Making the Dx with dermoscopy, skin biopsy

Dermoscopy is a useful technique for diagnosing lichen nitidus. Dermoscopic features of lichen nitidus include white, well-demarcated circular areas with a brown shadow.4 Skin biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis. Lichen nitidus has a distinct histopathologic “ball and claw” appearance of rete ridges clutching a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.1

Consider these common conditions in the differential

The differential diagnosis includes lichen spinulosus, papular eczema, lichen planus, keratosis pilaris, and verruca plana (flat warts).

Continue to: Lichen spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus lesions are similar in appearance to lichen nitidus but are grouped in patches on the neck, arms, abdomen, and buttocks.1 The Koebner phenomenon is not typically present. Lichen spinulosus lesions consist of follicular papules that may exhibit a central keratotic plug.

Papular eczema lesions lack the uniform and discrete appearance observed in lichen nitidus. Pruritus is also more likely to be present in papular eczema.

Lichen planus lesions are typically violaceous, flat, and larger in size than lichen nitidus (measuring 1 mm to 1 cm), and have characteristic Wickham striae. Oral involvement is also more suggestive of lichen planus.

Keratosis pilaris is distinguished by its much more common occurrence and perifollicular erythema.

Verruca plana, in contrast to lichen nitidus, are typically pink, flat-topped lesions. They are also larger in size (2 mm to 5 mm).

Continue to: Topical treatment can help manage the condition

Topical treatment can help manage the condition

Most patients experience spontaneous resolution of lesions within several years; treatment is primarily for symptomatic or cosmetic purposes. When pruritus is present, topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines may help (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oral hydroxyzine). Topical calcineurin inhibitors, such as pimecrolimus cream, have also been reported as an effective therapy in children with lichen nitidus.1 In patients with generalized lichen nitidus who have not responded to topical corticosteroids, phototherapy can be used.5 There are no randomized controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of different types of treatments.

In this case, the patient was advised to start using an over-the-counter topical steroid, such as 1% hydrocortisone cream, to help control pruritus. He was scheduled for a follow-up appointment in 3 months.

1. Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Inc;2008:167-170.

2. Lapins NA, Willoughby C, Helwig EB. Lichen nitidus. A study of forty-three cases. Cutis. 1978;21:634-637.

3. Botelho LFF, de Magalhães JPJ, Ogawa MM, et al. Generalized Lichen nitidus associated with Down’s syndrome: case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:466-468. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000300018

4. Malakar S, Save S, Mehta P. Brown shadow in lichen nitidus: a dermoscopic marker! Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:479-480. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_338_17

5. Synakiewicz J, Polańska A, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:488-490. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.63890

1. Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Inc;2008:167-170.

2. Lapins NA, Willoughby C, Helwig EB. Lichen nitidus. A study of forty-three cases. Cutis. 1978;21:634-637.

3. Botelho LFF, de Magalhães JPJ, Ogawa MM, et al. Generalized Lichen nitidus associated with Down’s syndrome: case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:466-468. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000300018

4. Malakar S, Save S, Mehta P. Brown shadow in lichen nitidus: a dermoscopic marker! Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:479-480. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_338_17

5. Synakiewicz J, Polańska A, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:488-490. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.63890

Infant with mottled skin

The net-like, violaceous pattern on the infant’s skin was characteristic of livedo reticularis.

Livedo reticularis is thought to arise from a change in underlying cutaneous blood flow.1 The appearance of this condition reflects the configuration of underlying cutaneous vasculature. Arterioles oriented perpendicularly to the skin can surface from a network where blood flows from arteriole to capillary to venule. The reticular appearance is a result of increased visibility of the venous plexus.1

Common culprits of this manifestation are impaired arteriolar perfusion and venous congestion, which may be caused by vasospasm, arterial thrombosis, or hyperviscosity.1 If diagnostic biopsies are needed, they should be taken from the pale central areas.

Livedo reticularis can be categorized into groups to help delineate the patient-specific pathogenesis: idiopathic, primary, secondary (due to underlying disease; see below), and physiologic.1 Physiologic livedo reticularis, which this patient had, is known as cutis marmorata (CM); it occurs in response to cold temperatures. It may be more common, or visible, in individuals with lighter skin types and in preterm infants. The condition typically affects the lower extremities but may also occur on the trunk and upper extremities.1

Physiologic livedo reticularis usually resolves with warming of the extremities. Secondary livedo reticularis usually manifests in older patients and is due to serious conditions such as malignancies, antiphospholipid syndrome, and Sneddon syndrome. For these patients, coagulopathy and malignancy evaluation targeting the underlying cause of the livedo reticularis is warranted. Interestingly, livedo reticularis may also be associated with COVID-19, but this association has not been reported frequently in children.2

The infant in this case experienced rapid resolution with warming. The family was educated about the CM form of livedo reticularis and instructed to keep her warm. No other treatment or evaluation was indicated.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP. Text courtesy of Christy Nwankwo, BA, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Gibbs MB, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1009-1019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.11.051

2. Lavery MJ, Bouvier CA, Thompson B. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in children (and adults): a virus that does not discriminate. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:323-328. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.10.020

The net-like, violaceous pattern on the infant’s skin was characteristic of livedo reticularis.

Livedo reticularis is thought to arise from a change in underlying cutaneous blood flow.1 The appearance of this condition reflects the configuration of underlying cutaneous vasculature. Arterioles oriented perpendicularly to the skin can surface from a network where blood flows from arteriole to capillary to venule. The reticular appearance is a result of increased visibility of the venous plexus.1

Common culprits of this manifestation are impaired arteriolar perfusion and venous congestion, which may be caused by vasospasm, arterial thrombosis, or hyperviscosity.1 If diagnostic biopsies are needed, they should be taken from the pale central areas.

Livedo reticularis can be categorized into groups to help delineate the patient-specific pathogenesis: idiopathic, primary, secondary (due to underlying disease; see below), and physiologic.1 Physiologic livedo reticularis, which this patient had, is known as cutis marmorata (CM); it occurs in response to cold temperatures. It may be more common, or visible, in individuals with lighter skin types and in preterm infants. The condition typically affects the lower extremities but may also occur on the trunk and upper extremities.1

Physiologic livedo reticularis usually resolves with warming of the extremities. Secondary livedo reticularis usually manifests in older patients and is due to serious conditions such as malignancies, antiphospholipid syndrome, and Sneddon syndrome. For these patients, coagulopathy and malignancy evaluation targeting the underlying cause of the livedo reticularis is warranted. Interestingly, livedo reticularis may also be associated with COVID-19, but this association has not been reported frequently in children.2

The infant in this case experienced rapid resolution with warming. The family was educated about the CM form of livedo reticularis and instructed to keep her warm. No other treatment or evaluation was indicated.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP. Text courtesy of Christy Nwankwo, BA, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The net-like, violaceous pattern on the infant’s skin was characteristic of livedo reticularis.

Livedo reticularis is thought to arise from a change in underlying cutaneous blood flow.1 The appearance of this condition reflects the configuration of underlying cutaneous vasculature. Arterioles oriented perpendicularly to the skin can surface from a network where blood flows from arteriole to capillary to venule. The reticular appearance is a result of increased visibility of the venous plexus.1

Common culprits of this manifestation are impaired arteriolar perfusion and venous congestion, which may be caused by vasospasm, arterial thrombosis, or hyperviscosity.1 If diagnostic biopsies are needed, they should be taken from the pale central areas.

Livedo reticularis can be categorized into groups to help delineate the patient-specific pathogenesis: idiopathic, primary, secondary (due to underlying disease; see below), and physiologic.1 Physiologic livedo reticularis, which this patient had, is known as cutis marmorata (CM); it occurs in response to cold temperatures. It may be more common, or visible, in individuals with lighter skin types and in preterm infants. The condition typically affects the lower extremities but may also occur on the trunk and upper extremities.1

Physiologic livedo reticularis usually resolves with warming of the extremities. Secondary livedo reticularis usually manifests in older patients and is due to serious conditions such as malignancies, antiphospholipid syndrome, and Sneddon syndrome. For these patients, coagulopathy and malignancy evaluation targeting the underlying cause of the livedo reticularis is warranted. Interestingly, livedo reticularis may also be associated with COVID-19, but this association has not been reported frequently in children.2

The infant in this case experienced rapid resolution with warming. The family was educated about the CM form of livedo reticularis and instructed to keep her warm. No other treatment or evaluation was indicated.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP. Text courtesy of Christy Nwankwo, BA, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Gibbs MB, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1009-1019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.11.051

2. Lavery MJ, Bouvier CA, Thompson B. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in children (and adults): a virus that does not discriminate. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:323-328. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.10.020

1. Gibbs MB, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1009-1019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.11.051

2. Lavery MJ, Bouvier CA, Thompson B. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in children (and adults): a virus that does not discriminate. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:323-328. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.10.020

Ulcerated lower leg lesion

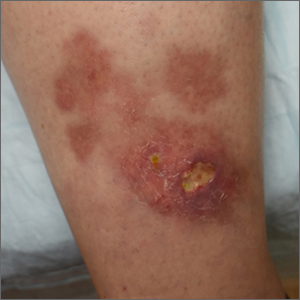

The patient’s atrophic plaques with a violaceous rim, indurated borders, and ulceration on the anterior pretibial surface were consistent with ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL typically manifests on the bilateral pretibial region as small papules or nodules that expand into yellow-brown atrophic, telangiectatic plaques with an elevated violaceous rim.1,2 Most lesions are asymptomatic due to nerve damage, but up to 35% of patients may experience pruritus and tenderness.2 Close monitoring of lesions is recommended due to risk of ulceration and potential for malignancy.2 Rare reports show development of squamous cell carcinoma within NL lesions.1

Women are 3 times more likely than men to have NL, with an average age of onset between 30 and 40 years.1 The exact pathogenesis of NL is unknown.2 Theories include vascular abnormalities (immunoglobulin deposition or microangiopathic changes leading to collagen degradation), abnormalities of collagen synthesis, neutrophil migration, and elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels.1,3

While NL can be diagnosed clinically, a skin biopsy may be necessary in atypical lesions. The biopsy will reveal palisading granulomatous inflammation in the dermis, with multinucleated histiocytes palisading around degenerated collagen bundles.2

No treatment has proven to be effective for NL. Glucose control in patients with diabetes does not have a significant effect on the NL lesions.1-3 Corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, and systemic—depending on the severity) are considered first-line therapy.1-3 Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and trauma avoidance, are recommended to promote healing; proper wound care is important when there is ulceration.1,3 Other treatment options include oral pentoxifylline, topical retinoids or calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic immune system modulators (eg, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine).

Since this patient did not respond to the topical betamethasone, she was started on oral pentoxifylline 400 mg tid. Unfortunately, she had to discontinue the medication because of gastrointestinal upset and was then started on doxycycline 100 mg orally bid. She was lost to follow-up.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Harika Echuri, MD, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 26, 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459318/

2. Tong LX, Penn L, Meehan SA, Kim RH. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt0qg3b3zw. doi: 10.5070/D32412042442

3. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

The patient’s atrophic plaques with a violaceous rim, indurated borders, and ulceration on the anterior pretibial surface were consistent with ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL typically manifests on the bilateral pretibial region as small papules or nodules that expand into yellow-brown atrophic, telangiectatic plaques with an elevated violaceous rim.1,2 Most lesions are asymptomatic due to nerve damage, but up to 35% of patients may experience pruritus and tenderness.2 Close monitoring of lesions is recommended due to risk of ulceration and potential for malignancy.2 Rare reports show development of squamous cell carcinoma within NL lesions.1

Women are 3 times more likely than men to have NL, with an average age of onset between 30 and 40 years.1 The exact pathogenesis of NL is unknown.2 Theories include vascular abnormalities (immunoglobulin deposition or microangiopathic changes leading to collagen degradation), abnormalities of collagen synthesis, neutrophil migration, and elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels.1,3

While NL can be diagnosed clinically, a skin biopsy may be necessary in atypical lesions. The biopsy will reveal palisading granulomatous inflammation in the dermis, with multinucleated histiocytes palisading around degenerated collagen bundles.2

No treatment has proven to be effective for NL. Glucose control in patients with diabetes does not have a significant effect on the NL lesions.1-3 Corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, and systemic—depending on the severity) are considered first-line therapy.1-3 Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and trauma avoidance, are recommended to promote healing; proper wound care is important when there is ulceration.1,3 Other treatment options include oral pentoxifylline, topical retinoids or calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic immune system modulators (eg, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine).

Since this patient did not respond to the topical betamethasone, she was started on oral pentoxifylline 400 mg tid. Unfortunately, she had to discontinue the medication because of gastrointestinal upset and was then started on doxycycline 100 mg orally bid. She was lost to follow-up.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Harika Echuri, MD, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The patient’s atrophic plaques with a violaceous rim, indurated borders, and ulceration on the anterior pretibial surface were consistent with ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL typically manifests on the bilateral pretibial region as small papules or nodules that expand into yellow-brown atrophic, telangiectatic plaques with an elevated violaceous rim.1,2 Most lesions are asymptomatic due to nerve damage, but up to 35% of patients may experience pruritus and tenderness.2 Close monitoring of lesions is recommended due to risk of ulceration and potential for malignancy.2 Rare reports show development of squamous cell carcinoma within NL lesions.1

Women are 3 times more likely than men to have NL, with an average age of onset between 30 and 40 years.1 The exact pathogenesis of NL is unknown.2 Theories include vascular abnormalities (immunoglobulin deposition or microangiopathic changes leading to collagen degradation), abnormalities of collagen synthesis, neutrophil migration, and elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels.1,3

While NL can be diagnosed clinically, a skin biopsy may be necessary in atypical lesions. The biopsy will reveal palisading granulomatous inflammation in the dermis, with multinucleated histiocytes palisading around degenerated collagen bundles.2

No treatment has proven to be effective for NL. Glucose control in patients with diabetes does not have a significant effect on the NL lesions.1-3 Corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, and systemic—depending on the severity) are considered first-line therapy.1-3 Lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and trauma avoidance, are recommended to promote healing; proper wound care is important when there is ulceration.1,3 Other treatment options include oral pentoxifylline, topical retinoids or calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic immune system modulators (eg, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine).

Since this patient did not respond to the topical betamethasone, she was started on oral pentoxifylline 400 mg tid. Unfortunately, she had to discontinue the medication because of gastrointestinal upset and was then started on doxycycline 100 mg orally bid. She was lost to follow-up.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Harika Echuri, MD, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 26, 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459318/

2. Tong LX, Penn L, Meehan SA, Kim RH. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt0qg3b3zw. doi: 10.5070/D32412042442

3. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

1. Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 26, 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459318/

2. Tong LX, Penn L, Meehan SA, Kim RH. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt0qg3b3zw. doi: 10.5070/D32412042442

3. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

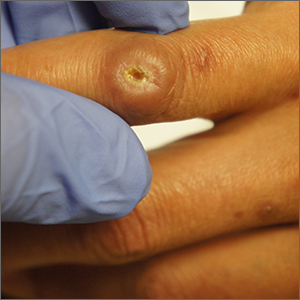

Ulcer on knuckle

Since the papules were worrisome for vasculitis, 2 punch biopsies were performed on smaller, younger lesions on the hand and 1 was submitted for direct immunofluorescence. Findings revealed a leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) with prominent immunoglobulin A (IgA) deposits around the vessel wall. The clinical and pathologic findings were consistent with a rare fibrosing LCV called erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). The practice of sampling nonblanching purpura or papules for both standard pathology (hematoxylin and eosin) and direct immunofluorescence can facilitate the diagnosis of unusual conditions that may occur only a few times in one’s career.

EED is rare, chronic, and may be associated with IgA gammopathy, IgA antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, recent streptococcal or HIV infections, or myelodysplastic syndrome. A robust work-up to identify whether any of these factors are at work is critical.1 Distinct from other vasculitides, EED forms granulation tissue that becomes reinjured.

This patient was found to have an IgA monoclonal gammopathy that was monitored by Hematology. After checking her glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, she was treated with oral dapsone 25 mg/d. Dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg/d, which improved her symptoms considerably and the ulcerated papule was surgically revised and closed. EED can last for years and ultimately clear or can persist indefinitely.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Sandhu JK, Albrecht J, Agnihotri G, et al. Erythema elevatum et diutinum as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:679-683. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.07.028

Since the papules were worrisome for vasculitis, 2 punch biopsies were performed on smaller, younger lesions on the hand and 1 was submitted for direct immunofluorescence. Findings revealed a leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) with prominent immunoglobulin A (IgA) deposits around the vessel wall. The clinical and pathologic findings were consistent with a rare fibrosing LCV called erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). The practice of sampling nonblanching purpura or papules for both standard pathology (hematoxylin and eosin) and direct immunofluorescence can facilitate the diagnosis of unusual conditions that may occur only a few times in one’s career.

EED is rare, chronic, and may be associated with IgA gammopathy, IgA antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, recent streptococcal or HIV infections, or myelodysplastic syndrome. A robust work-up to identify whether any of these factors are at work is critical.1 Distinct from other vasculitides, EED forms granulation tissue that becomes reinjured.

This patient was found to have an IgA monoclonal gammopathy that was monitored by Hematology. After checking her glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, she was treated with oral dapsone 25 mg/d. Dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg/d, which improved her symptoms considerably and the ulcerated papule was surgically revised and closed. EED can last for years and ultimately clear or can persist indefinitely.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Since the papules were worrisome for vasculitis, 2 punch biopsies were performed on smaller, younger lesions on the hand and 1 was submitted for direct immunofluorescence. Findings revealed a leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) with prominent immunoglobulin A (IgA) deposits around the vessel wall. The clinical and pathologic findings were consistent with a rare fibrosing LCV called erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). The practice of sampling nonblanching purpura or papules for both standard pathology (hematoxylin and eosin) and direct immunofluorescence can facilitate the diagnosis of unusual conditions that may occur only a few times in one’s career.

EED is rare, chronic, and may be associated with IgA gammopathy, IgA antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, recent streptococcal or HIV infections, or myelodysplastic syndrome. A robust work-up to identify whether any of these factors are at work is critical.1 Distinct from other vasculitides, EED forms granulation tissue that becomes reinjured.

This patient was found to have an IgA monoclonal gammopathy that was monitored by Hematology. After checking her glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, she was treated with oral dapsone 25 mg/d. Dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg/d, which improved her symptoms considerably and the ulcerated papule was surgically revised and closed. EED can last for years and ultimately clear or can persist indefinitely.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Sandhu JK, Albrecht J, Agnihotri G, et al. Erythema elevatum et diutinum as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:679-683. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.07.028

1. Sandhu JK, Albrecht J, Agnihotri G, et al. Erythema elevatum et diutinum as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:679-683. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.07.028

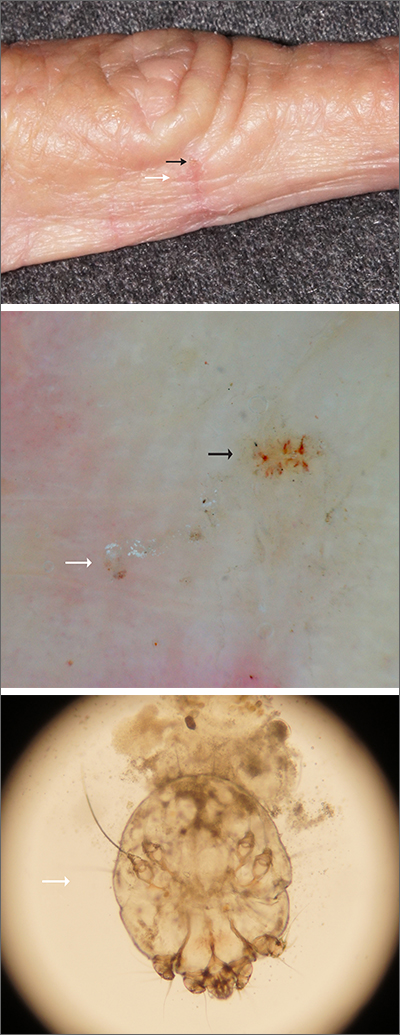

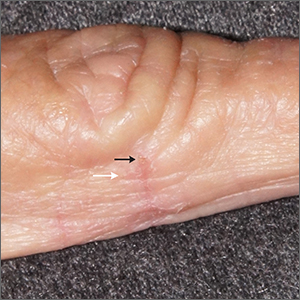

Itching at night

Microscopic evaluation of a dermoscopy-guided skin scraping revealed that this was a case of scabies.

Classically, patients with scabies have many excoriated papules or plaques on their hands, genitals, and trunk with itching so intense that their sleep is interrupted. However, scabies can also be diagnosed in patients who complain of itching but also have very subtle skin findings, such as a small dry patch or fissure (as in this case). Such subtle findings can be easily mistaken for mild hand dermatitis.

In the elderly, itching without a significant rash can arise from many causes. A short list includes dry skin, medications, kidney disease, liver disease, and of course, various dermatologic conditions. Dermoscopy is a sensitive and specific tool for investigating itching and areas of suspected infestation with mites.1 A mite appears as an oval on dermoscopy, but the most recognizable part is the head and front legs, which appear as a single gray triangle. The photo shows that the most erythematous area around a burrow (black arrows) is an excellent place to start when looking through the dermatoscope. In this case, an area of broken skin was connected to a haphazard tunnel that ultimately led to the mite (white arrows).

Scabies may be effectively treated with topical permethrin 5% applied over every inch of the body from the top of the neck to the tips of the toes.

This topical treatment is left on for at least 8 hours and reapplied a week later. Also, remember to take a careful history of close contacts so that others who are affected may receive treatment.

This patient was treated with permethrin, as was her adult son who lived at home with her and had similar itching. Permethrin comes in 60 g tubes, which is enough to treat 1 adult twice. After 6 weeks, all itching symptoms in the patient had cleared.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.025

Microscopic evaluation of a dermoscopy-guided skin scraping revealed that this was a case of scabies.

Classically, patients with scabies have many excoriated papules or plaques on their hands, genitals, and trunk with itching so intense that their sleep is interrupted. However, scabies can also be diagnosed in patients who complain of itching but also have very subtle skin findings, such as a small dry patch or fissure (as in this case). Such subtle findings can be easily mistaken for mild hand dermatitis.

In the elderly, itching without a significant rash can arise from many causes. A short list includes dry skin, medications, kidney disease, liver disease, and of course, various dermatologic conditions. Dermoscopy is a sensitive and specific tool for investigating itching and areas of suspected infestation with mites.1 A mite appears as an oval on dermoscopy, but the most recognizable part is the head and front legs, which appear as a single gray triangle. The photo shows that the most erythematous area around a burrow (black arrows) is an excellent place to start when looking through the dermatoscope. In this case, an area of broken skin was connected to a haphazard tunnel that ultimately led to the mite (white arrows).

Scabies may be effectively treated with topical permethrin 5% applied over every inch of the body from the top of the neck to the tips of the toes.

This topical treatment is left on for at least 8 hours and reapplied a week later. Also, remember to take a careful history of close contacts so that others who are affected may receive treatment.

This patient was treated with permethrin, as was her adult son who lived at home with her and had similar itching. Permethrin comes in 60 g tubes, which is enough to treat 1 adult twice. After 6 weeks, all itching symptoms in the patient had cleared.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Microscopic evaluation of a dermoscopy-guided skin scraping revealed that this was a case of scabies.

Classically, patients with scabies have many excoriated papules or plaques on their hands, genitals, and trunk with itching so intense that their sleep is interrupted. However, scabies can also be diagnosed in patients who complain of itching but also have very subtle skin findings, such as a small dry patch or fissure (as in this case). Such subtle findings can be easily mistaken for mild hand dermatitis.

In the elderly, itching without a significant rash can arise from many causes. A short list includes dry skin, medications, kidney disease, liver disease, and of course, various dermatologic conditions. Dermoscopy is a sensitive and specific tool for investigating itching and areas of suspected infestation with mites.1 A mite appears as an oval on dermoscopy, but the most recognizable part is the head and front legs, which appear as a single gray triangle. The photo shows that the most erythematous area around a burrow (black arrows) is an excellent place to start when looking through the dermatoscope. In this case, an area of broken skin was connected to a haphazard tunnel that ultimately led to the mite (white arrows).

Scabies may be effectively treated with topical permethrin 5% applied over every inch of the body from the top of the neck to the tips of the toes.

This topical treatment is left on for at least 8 hours and reapplied a week later. Also, remember to take a careful history of close contacts so that others who are affected may receive treatment.

This patient was treated with permethrin, as was her adult son who lived at home with her and had similar itching. Permethrin comes in 60 g tubes, which is enough to treat 1 adult twice. After 6 weeks, all itching symptoms in the patient had cleared.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.025

1. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.025

Smooth plaque on ankle

A 4-mm punch biopsy of the annular border confirmed a diagnosis of localized granuloma annulare (GA).

There is a long list of differential diagnoses for annular patches and plaques; it includes tinea corporis and important systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis and Lyme disease. Clinical features of GA include annular, minimally scaly patches to plaques with central clearing on extensor surfaces in children and adults. Sometimes GA is much more widespread. Often, the diagnosis can be made clinically, but a punch biopsy of the deep dermis will confirm the diagnosis by showing palisading or interstitial granulomatous inflammation, necrobiotic collagen, and often mucin.

GA is a common inflammatory disorder with an uncertain etiology. Localized GA affects children and adults and is often self limiting. It may, however, last for months or years before resolving. Disseminated disease is much more recalcitrant with few good treatment options if topical steroids or phototherapy fails. Treatment for localized disease is much more successful with topical or intralesional steroids.

Trauma can cause a localized plaque to resolve; a lesion may resolve soon after a biopsy is performed. Possible related conditions include diabetes, thyroid disease, hepatitis C, and hyperlipidemia; but there is no consensus on focused screening. Similarly, associations or nonassociations with malignancy in adults have been cited, but evidence is lacking.1

In this case, the patient and his family were reassured that the diagnosis wasn’t serious. In a single visit, he received a series of 6 to 7 injections of 10 mg/mL triamcinolone which led to resolution of the lesion in 4 weeks.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.055

A 4-mm punch biopsy of the annular border confirmed a diagnosis of localized granuloma annulare (GA).

There is a long list of differential diagnoses for annular patches and plaques; it includes tinea corporis and important systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis and Lyme disease. Clinical features of GA include annular, minimally scaly patches to plaques with central clearing on extensor surfaces in children and adults. Sometimes GA is much more widespread. Often, the diagnosis can be made clinically, but a punch biopsy of the deep dermis will confirm the diagnosis by showing palisading or interstitial granulomatous inflammation, necrobiotic collagen, and often mucin.

GA is a common inflammatory disorder with an uncertain etiology. Localized GA affects children and adults and is often self limiting. It may, however, last for months or years before resolving. Disseminated disease is much more recalcitrant with few good treatment options if topical steroids or phototherapy fails. Treatment for localized disease is much more successful with topical or intralesional steroids.

Trauma can cause a localized plaque to resolve; a lesion may resolve soon after a biopsy is performed. Possible related conditions include diabetes, thyroid disease, hepatitis C, and hyperlipidemia; but there is no consensus on focused screening. Similarly, associations or nonassociations with malignancy in adults have been cited, but evidence is lacking.1

In this case, the patient and his family were reassured that the diagnosis wasn’t serious. In a single visit, he received a series of 6 to 7 injections of 10 mg/mL triamcinolone which led to resolution of the lesion in 4 weeks.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A 4-mm punch biopsy of the annular border confirmed a diagnosis of localized granuloma annulare (GA).

There is a long list of differential diagnoses for annular patches and plaques; it includes tinea corporis and important systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis and Lyme disease. Clinical features of GA include annular, minimally scaly patches to plaques with central clearing on extensor surfaces in children and adults. Sometimes GA is much more widespread. Often, the diagnosis can be made clinically, but a punch biopsy of the deep dermis will confirm the diagnosis by showing palisading or interstitial granulomatous inflammation, necrobiotic collagen, and often mucin.

GA is a common inflammatory disorder with an uncertain etiology. Localized GA affects children and adults and is often self limiting. It may, however, last for months or years before resolving. Disseminated disease is much more recalcitrant with few good treatment options if topical steroids or phototherapy fails. Treatment for localized disease is much more successful with topical or intralesional steroids.

Trauma can cause a localized plaque to resolve; a lesion may resolve soon after a biopsy is performed. Possible related conditions include diabetes, thyroid disease, hepatitis C, and hyperlipidemia; but there is no consensus on focused screening. Similarly, associations or nonassociations with malignancy in adults have been cited, but evidence is lacking.1

In this case, the patient and his family were reassured that the diagnosis wasn’t serious. In a single visit, he received a series of 6 to 7 injections of 10 mg/mL triamcinolone which led to resolution of the lesion in 4 weeks.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.055

1. Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.055

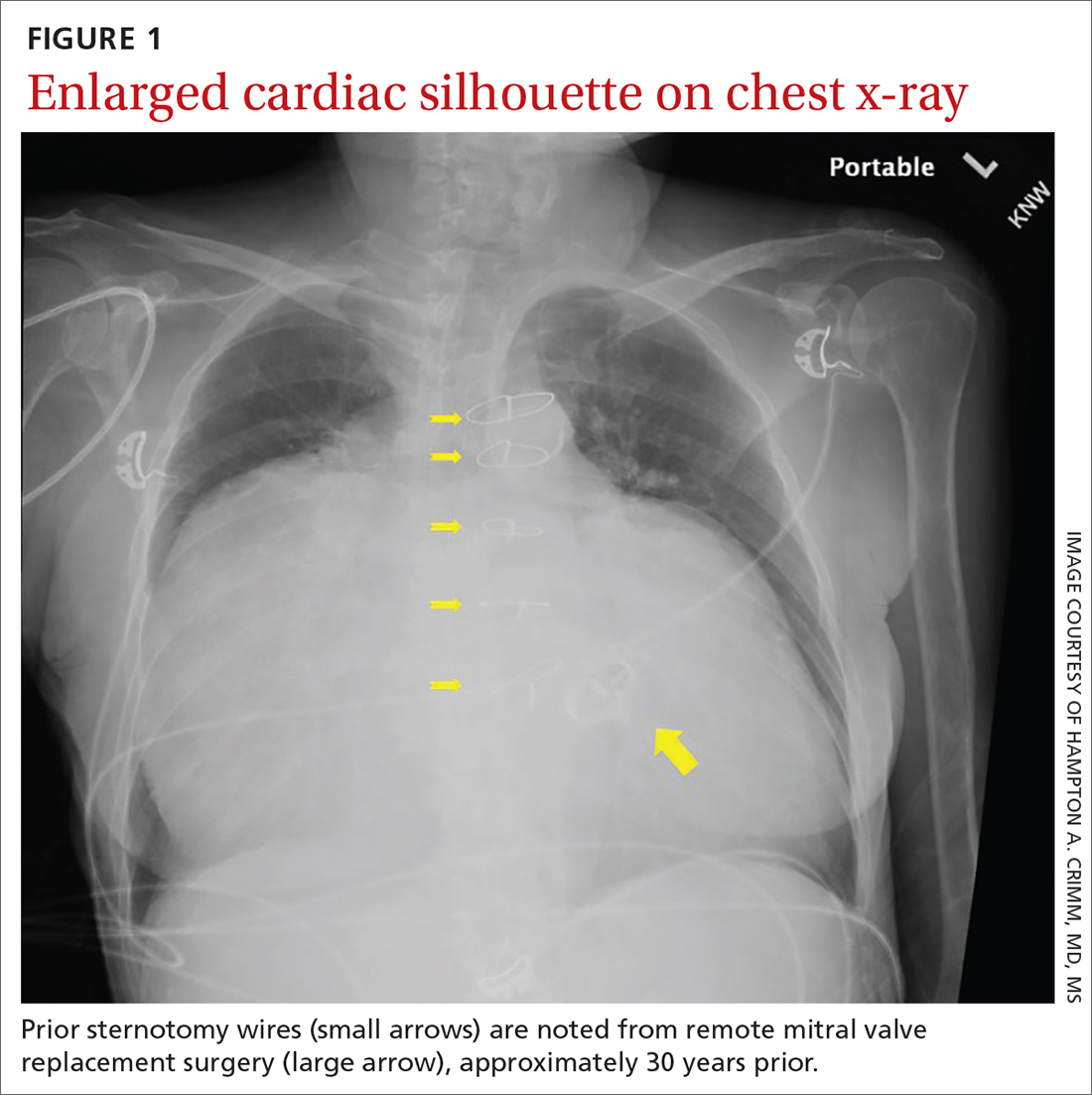

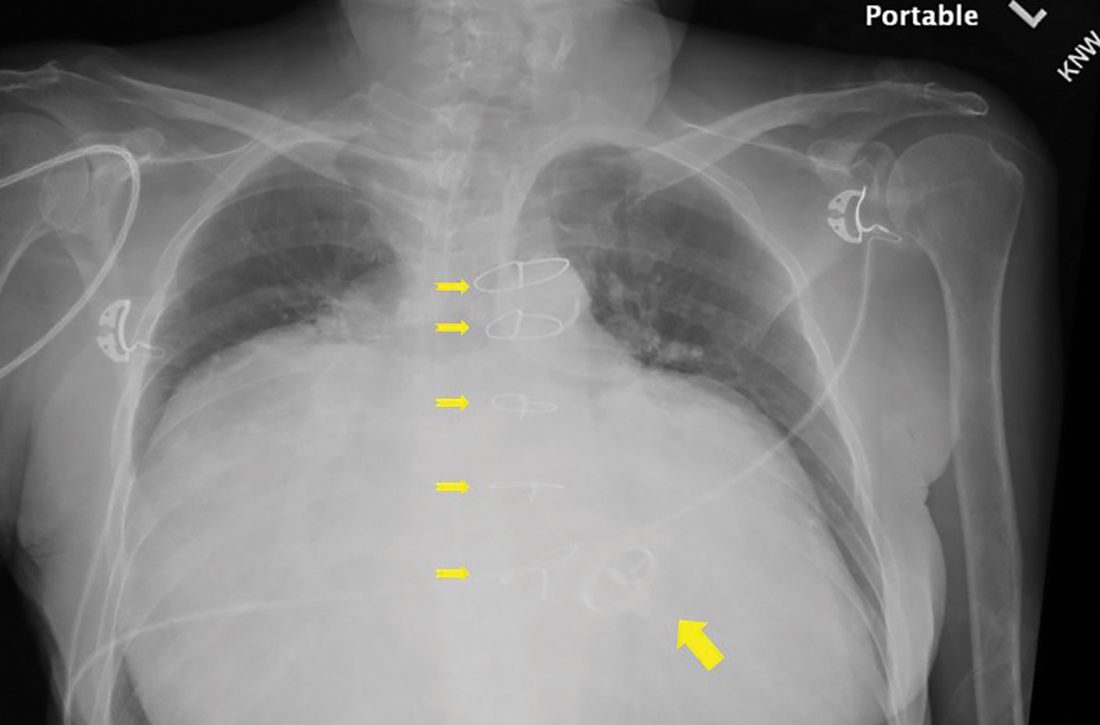

Substantially enlarged cardiac silhouette

A 63-YEAR-OLD SOUTHEAST ASIAN WOMAN presented with early satiety, mild swelling of her lower extremities, and several months of progressive shortness of breath that had become severe (provoked by activities of daily living). She had a history of longstanding, rate-controlled atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation. She also had a history of mitral valve stenosis that was treated 30 years earlier with mechanical valve replacement. The patient had previously been treated out of state and prior records were not available.

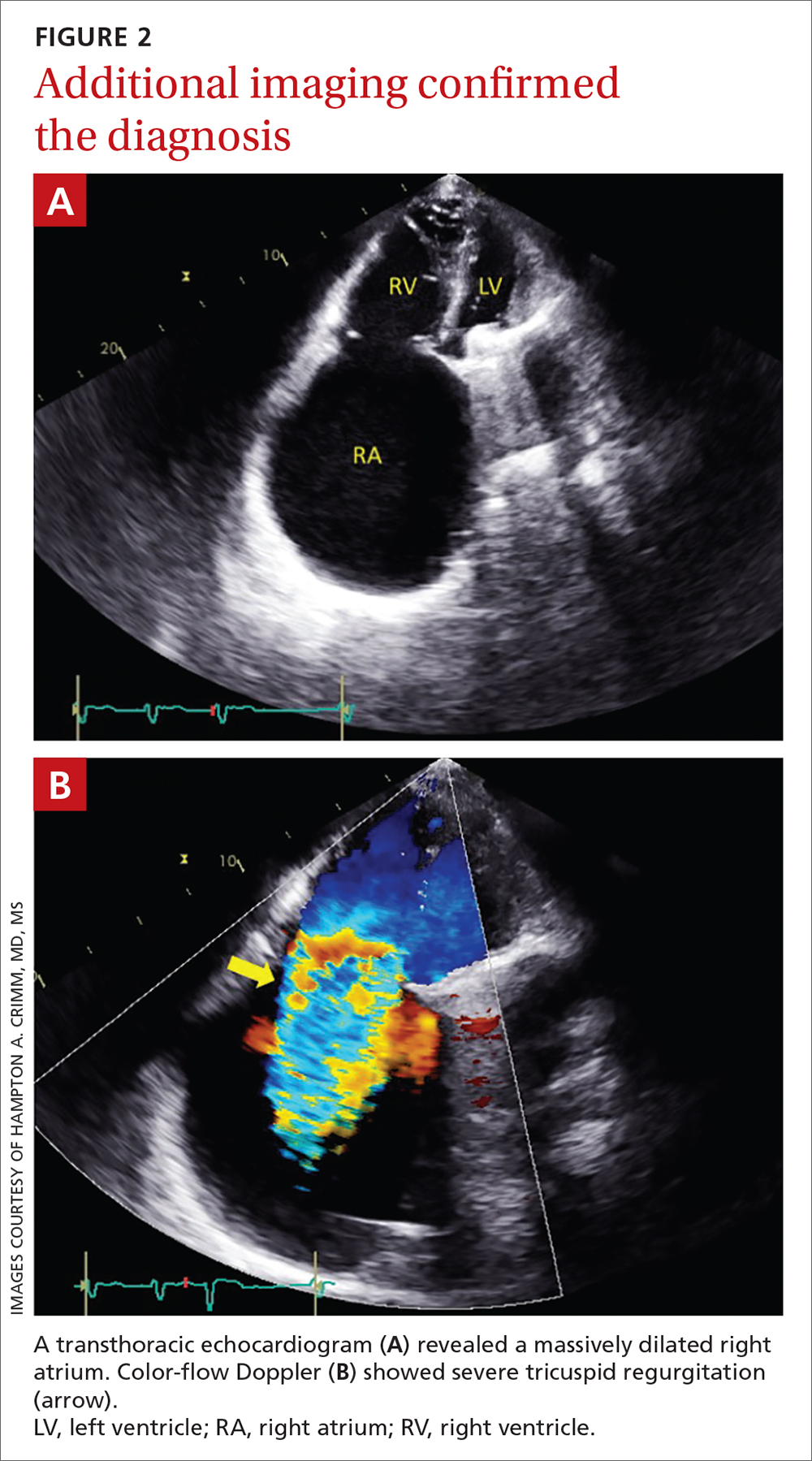

Chest radiography (CXR) was performed as part of the initial work-up (FIGURE 1) and demonstrated a substantially enlarged cardiac silhouette spanning the entire width of the chest without significant pleural effusion or evidence of airspace disease. Suspecting a primary cardiac pathology in this patient, we explored clinical findings of heart failure with transthoracic echocardiography.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Severe tricuspid valve regurgitation secondary to rheumatic heart disease

A transthoracic echocardiogram (FIGURE 2A) revealed cardiomegaly with massive right atrial enlargement; a color-flow Doppler (FIGURE 2B) revealed severe tricuspid regurgitation, reduced right ventricular systolic function, and preserved left ventricular systolic function. All of these findings pointed to the diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease (RHD), especially in the context of prior mitral valve stenosis.

RHD affects more than 33 million people annually and remains a significant problem globally.1 It’s associated with a relatively poor prognosis, especially if heart failure is present (as it was in this case).2,3 Although the mitral and aortic valves are most commonly affected, approximately 34% of patients will develop tricuspid regurgitation.4 Right-side cardiac manifestations of RHD may lead to clinical heart failure with chronic venous congestion and, ultimately, cirrhosis.

Suspect RHD when encountering a new murmur in a patient with prior history of acute rheumatic fever, especially if they are living in or are from a country where rheumatic disease is endemic (most of the developing world).

The diagnosis is confirmed when echocardiographic findings demonstrate characteristic pathologic valve changes (eg, thickening of the anterior mitral valve leaflet, especially the leaflet tips and subvalvular apparatus).

The differential for an enlarged cardiac silhouette

The differential diagnosis for an enlarged cardiac silhouette on CXR includes cardiomegaly (as in this case), pericardial effusion, or a thoracic mass (either mediastinal or pericardial). Imaging artifact from patient orientation may also yield the appearance of an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Distinguishing between these entities may be accomplished by incorporating the history with selection of more definitive imaging (eg, echocardiogram or computed tomography).

Continue to: Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Percutaneous or surgical intervention may be required with RHD, depending on the clinical scenario. If the patient also has atrial fibrillation, medical management includes oral anticoagulation (with a vitamin K antagonist). Additionally, secondary prophylaxis with long-term antibiotics (directed against recurrent group A Streptococcus infection) is recommended for RHD patients with mitral stenosis.5 If the patient in this case had engaged in more regular cardiology follow-up, the progression of her tricuspid regurgitation may have been mitigated by surgical intervention and aggressive medical management (although the progression of RHD can eclipse standard treatments).5

In this case, a liver biopsy was pursued for prognostication. Unfortunately, the biopsy demonstrated cirrhosis with perisinusoidal fibrosis suggesting an advanced, end-stage clinical state. This diagnosis precluded the patient’s eligibility for advanced therapies such as right ventricular assist device implantation or cardiac transplantation. Surgical intervention (repair or replacement) was also deemed likely to be futile due to right ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction in the context of antecedent left-side valve intervention.

The patient elected to pursue palliative care and died at home several months later. In the years since this case occurred, less invasive tricuspid valve interventions have been explored, offering promise of amelioration of such cases in the future.6

1. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et. al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:713-722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693

2. Zühlke L, Karthikeyan G, Engel ME, et al. Clinical outcomes in 3343 children and adults with rheumatic heart disease from 14 low- and middle-income countries: 2-year follow-up of the global rheumatic heart disease registry (the REMEDY study). Circulation. 2016;134:1456-1466. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

3. Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease—an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:297-309. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7

4. Sriharibabu M, Himabindu Y, Kabir, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in rural south India: a clinico-observational study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:25-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.02.011

5. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:4:e25-e197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

6. Fam NP, von Bardeleben RS, Hensey M, et al. Transfemoral transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement with the EVOQUE System: a multicenter, observational, first-in-human experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:501-511. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.11.045

A 63-YEAR-OLD SOUTHEAST ASIAN WOMAN presented with early satiety, mild swelling of her lower extremities, and several months of progressive shortness of breath that had become severe (provoked by activities of daily living). She had a history of longstanding, rate-controlled atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation. She also had a history of mitral valve stenosis that was treated 30 years earlier with mechanical valve replacement. The patient had previously been treated out of state and prior records were not available.

Chest radiography (CXR) was performed as part of the initial work-up (FIGURE 1) and demonstrated a substantially enlarged cardiac silhouette spanning the entire width of the chest without significant pleural effusion or evidence of airspace disease. Suspecting a primary cardiac pathology in this patient, we explored clinical findings of heart failure with transthoracic echocardiography.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Severe tricuspid valve regurgitation secondary to rheumatic heart disease

A transthoracic echocardiogram (FIGURE 2A) revealed cardiomegaly with massive right atrial enlargement; a color-flow Doppler (FIGURE 2B) revealed severe tricuspid regurgitation, reduced right ventricular systolic function, and preserved left ventricular systolic function. All of these findings pointed to the diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease (RHD), especially in the context of prior mitral valve stenosis.

RHD affects more than 33 million people annually and remains a significant problem globally.1 It’s associated with a relatively poor prognosis, especially if heart failure is present (as it was in this case).2,3 Although the mitral and aortic valves are most commonly affected, approximately 34% of patients will develop tricuspid regurgitation.4 Right-side cardiac manifestations of RHD may lead to clinical heart failure with chronic venous congestion and, ultimately, cirrhosis.

Suspect RHD when encountering a new murmur in a patient with prior history of acute rheumatic fever, especially if they are living in or are from a country where rheumatic disease is endemic (most of the developing world).

The diagnosis is confirmed when echocardiographic findings demonstrate characteristic pathologic valve changes (eg, thickening of the anterior mitral valve leaflet, especially the leaflet tips and subvalvular apparatus).

The differential for an enlarged cardiac silhouette

The differential diagnosis for an enlarged cardiac silhouette on CXR includes cardiomegaly (as in this case), pericardial effusion, or a thoracic mass (either mediastinal or pericardial). Imaging artifact from patient orientation may also yield the appearance of an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Distinguishing between these entities may be accomplished by incorporating the history with selection of more definitive imaging (eg, echocardiogram or computed tomography).

Continue to: Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Percutaneous or surgical intervention may be required with RHD, depending on the clinical scenario. If the patient also has atrial fibrillation, medical management includes oral anticoagulation (with a vitamin K antagonist). Additionally, secondary prophylaxis with long-term antibiotics (directed against recurrent group A Streptococcus infection) is recommended for RHD patients with mitral stenosis.5 If the patient in this case had engaged in more regular cardiology follow-up, the progression of her tricuspid regurgitation may have been mitigated by surgical intervention and aggressive medical management (although the progression of RHD can eclipse standard treatments).5

In this case, a liver biopsy was pursued for prognostication. Unfortunately, the biopsy demonstrated cirrhosis with perisinusoidal fibrosis suggesting an advanced, end-stage clinical state. This diagnosis precluded the patient’s eligibility for advanced therapies such as right ventricular assist device implantation or cardiac transplantation. Surgical intervention (repair or replacement) was also deemed likely to be futile due to right ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction in the context of antecedent left-side valve intervention.

The patient elected to pursue palliative care and died at home several months later. In the years since this case occurred, less invasive tricuspid valve interventions have been explored, offering promise of amelioration of such cases in the future.6

A 63-YEAR-OLD SOUTHEAST ASIAN WOMAN presented with early satiety, mild swelling of her lower extremities, and several months of progressive shortness of breath that had become severe (provoked by activities of daily living). She had a history of longstanding, rate-controlled atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation. She also had a history of mitral valve stenosis that was treated 30 years earlier with mechanical valve replacement. The patient had previously been treated out of state and prior records were not available.

Chest radiography (CXR) was performed as part of the initial work-up (FIGURE 1) and demonstrated a substantially enlarged cardiac silhouette spanning the entire width of the chest without significant pleural effusion or evidence of airspace disease. Suspecting a primary cardiac pathology in this patient, we explored clinical findings of heart failure with transthoracic echocardiography.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Severe tricuspid valve regurgitation secondary to rheumatic heart disease

A transthoracic echocardiogram (FIGURE 2A) revealed cardiomegaly with massive right atrial enlargement; a color-flow Doppler (FIGURE 2B) revealed severe tricuspid regurgitation, reduced right ventricular systolic function, and preserved left ventricular systolic function. All of these findings pointed to the diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease (RHD), especially in the context of prior mitral valve stenosis.

RHD affects more than 33 million people annually and remains a significant problem globally.1 It’s associated with a relatively poor prognosis, especially if heart failure is present (as it was in this case).2,3 Although the mitral and aortic valves are most commonly affected, approximately 34% of patients will develop tricuspid regurgitation.4 Right-side cardiac manifestations of RHD may lead to clinical heart failure with chronic venous congestion and, ultimately, cirrhosis.

Suspect RHD when encountering a new murmur in a patient with prior history of acute rheumatic fever, especially if they are living in or are from a country where rheumatic disease is endemic (most of the developing world).

The diagnosis is confirmed when echocardiographic findings demonstrate characteristic pathologic valve changes (eg, thickening of the anterior mitral valve leaflet, especially the leaflet tips and subvalvular apparatus).

The differential for an enlarged cardiac silhouette

The differential diagnosis for an enlarged cardiac silhouette on CXR includes cardiomegaly (as in this case), pericardial effusion, or a thoracic mass (either mediastinal or pericardial). Imaging artifact from patient orientation may also yield the appearance of an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Distinguishing between these entities may be accomplished by incorporating the history with selection of more definitive imaging (eg, echocardiogram or computed tomography).

Continue to: Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Percutaneous or surgical intervention may be required with RHD, depending on the clinical scenario. If the patient also has atrial fibrillation, medical management includes oral anticoagulation (with a vitamin K antagonist). Additionally, secondary prophylaxis with long-term antibiotics (directed against recurrent group A Streptococcus infection) is recommended for RHD patients with mitral stenosis.5 If the patient in this case had engaged in more regular cardiology follow-up, the progression of her tricuspid regurgitation may have been mitigated by surgical intervention and aggressive medical management (although the progression of RHD can eclipse standard treatments).5

In this case, a liver biopsy was pursued for prognostication. Unfortunately, the biopsy demonstrated cirrhosis with perisinusoidal fibrosis suggesting an advanced, end-stage clinical state. This diagnosis precluded the patient’s eligibility for advanced therapies such as right ventricular assist device implantation or cardiac transplantation. Surgical intervention (repair or replacement) was also deemed likely to be futile due to right ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction in the context of antecedent left-side valve intervention.

The patient elected to pursue palliative care and died at home several months later. In the years since this case occurred, less invasive tricuspid valve interventions have been explored, offering promise of amelioration of such cases in the future.6

1. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et. al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:713-722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693

2. Zühlke L, Karthikeyan G, Engel ME, et al. Clinical outcomes in 3343 children and adults with rheumatic heart disease from 14 low- and middle-income countries: 2-year follow-up of the global rheumatic heart disease registry (the REMEDY study). Circulation. 2016;134:1456-1466. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

3. Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease—an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:297-309. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7

4. Sriharibabu M, Himabindu Y, Kabir, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in rural south India: a clinico-observational study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:25-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.02.011

5. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:4:e25-e197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

6. Fam NP, von Bardeleben RS, Hensey M, et al. Transfemoral transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement with the EVOQUE System: a multicenter, observational, first-in-human experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:501-511. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.11.045

1. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et. al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:713-722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693

2. Zühlke L, Karthikeyan G, Engel ME, et al. Clinical outcomes in 3343 children and adults with rheumatic heart disease from 14 low- and middle-income countries: 2-year follow-up of the global rheumatic heart disease registry (the REMEDY study). Circulation. 2016;134:1456-1466. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

3. Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease—an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:297-309. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7

4. Sriharibabu M, Himabindu Y, Kabir, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in rural south India: a clinico-observational study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:25-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.02.011

5. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:4:e25-e197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

6. Fam NP, von Bardeleben RS, Hensey M, et al. Transfemoral transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement with the EVOQUE System: a multicenter, observational, first-in-human experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:501-511. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.11.045

Atypical knee pain

An 83-year-old woman, with an otherwise noncontributory past medical history, presented with chronic right knee pain. Over the prior 4 years, she had undergone evaluation by an outside physician and received several corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections, without symptom resolution. She described the pain as a 4/10 at rest and as “severe” when climbing stairs and exercising. The pain was localized to her lower back and right groin and extended to her right knee. She also said that she found it difficult to put on her socks. An outside orthopedic surgeon recommended right total knee arthroplasty, prompting her to seek a second opinion.

Examination of her right knee was unrevealing. However, during the hip examination, there was a pronounced loss of range of motion and concordant pain reproduction with the FABER (combined flexion, abduction, external rotation) and FADIR (combined flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) maneuvers.

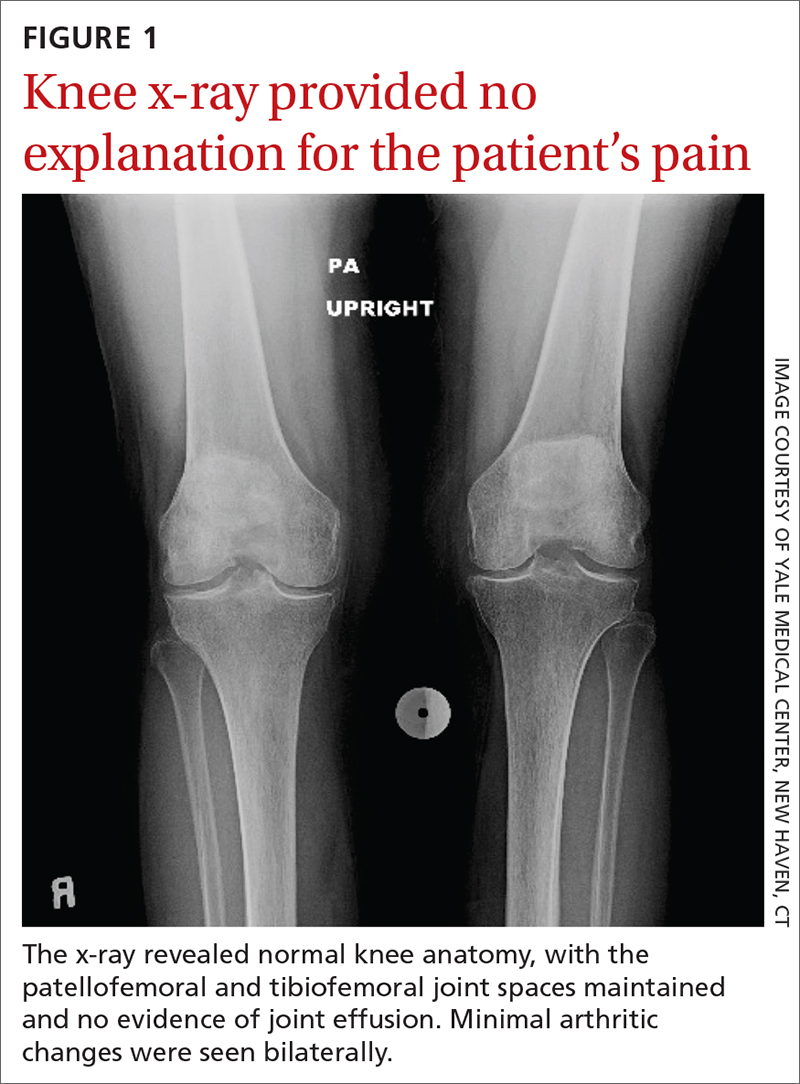

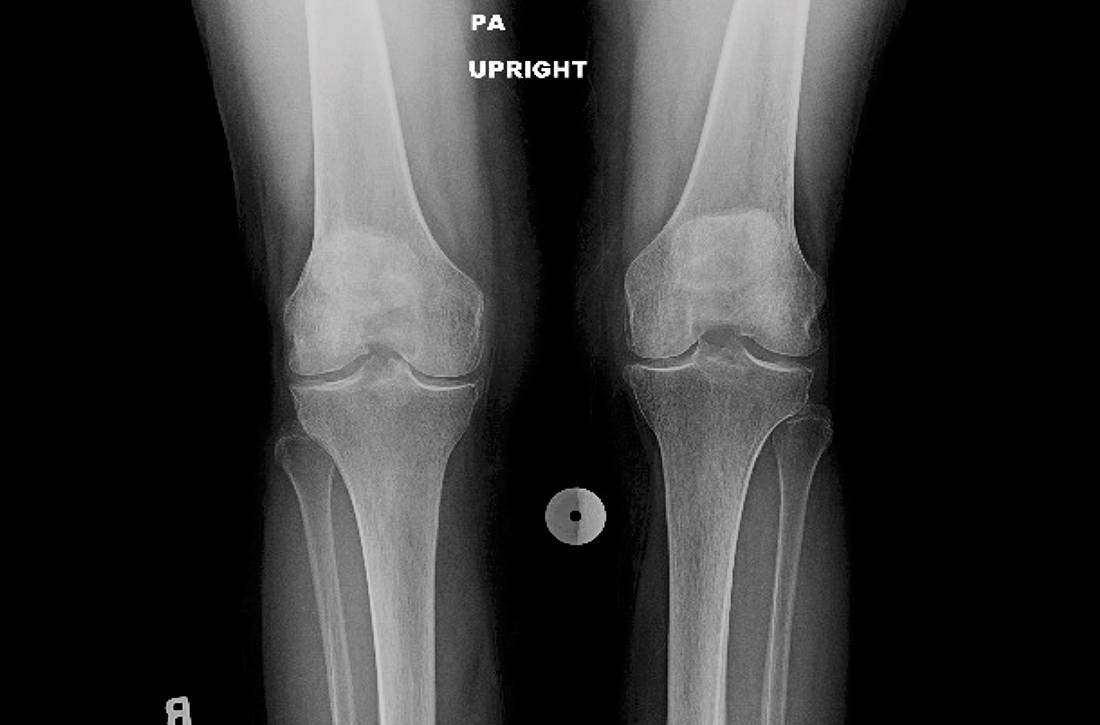

The patient’s extensive clinical and diagnostic history, combined with benign knee examination and imaging (FIGURE 1), ruled out isolated knee pathology.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Right hip OA with referred knee pain

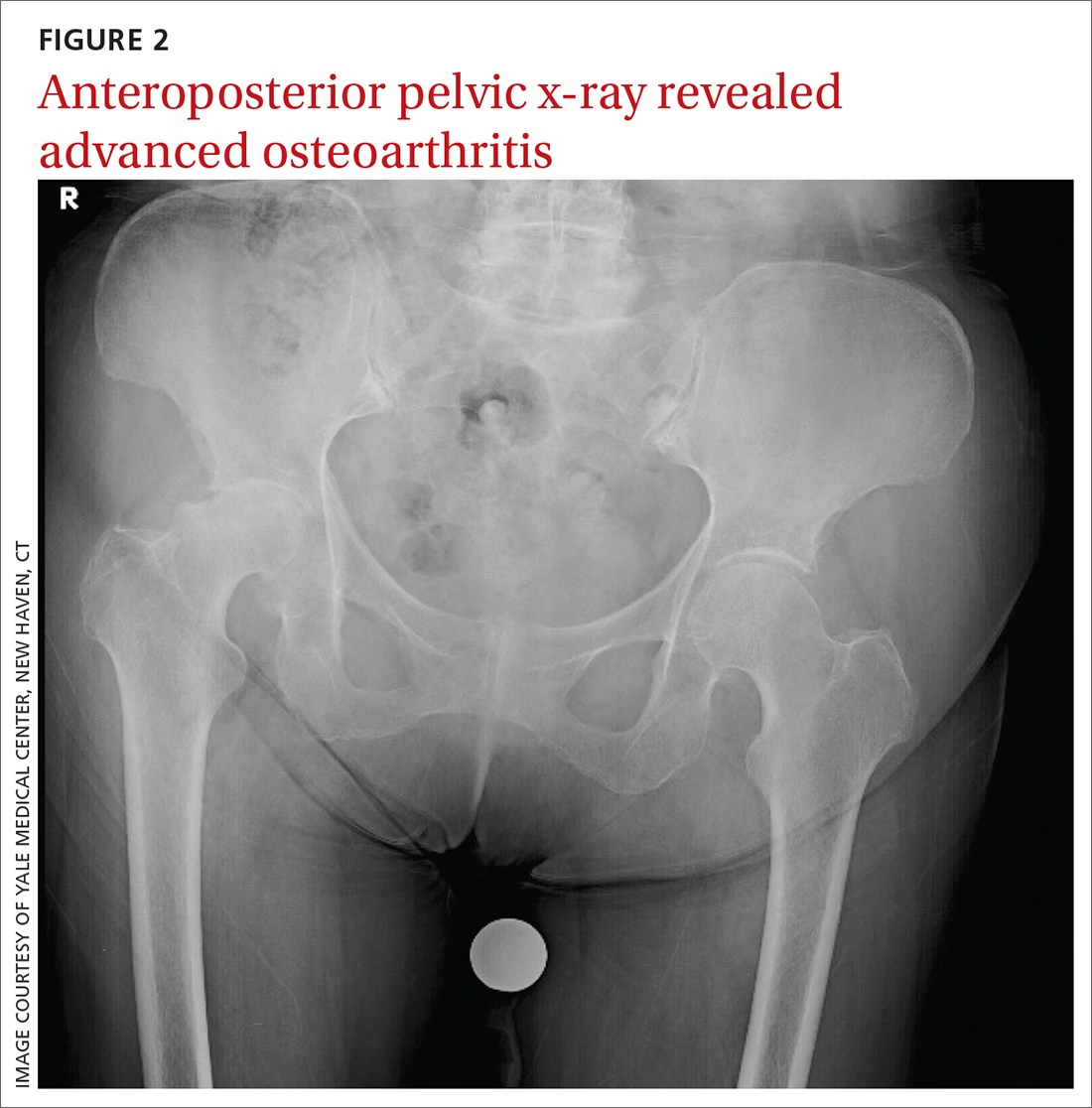

The patient’s history and physical exam prompted us to suspect right hip osteoarthritis (OA) with referred pain to the right knee. This suspicion was confirmed with hip radiographs (FIGURE 2), which revealed significant OA of the right hip, as evidenced by marked joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes. There was also superior migration of the right femoral head relative to the acetabulum. Additionally, there was loss of sphericity of the right femoral head, suggesting avascular necrosis with collapse.

Hip and knee OA are among the most common causes of disability worldwide. Knee and hip pain are estimated to affect up to 27% and 15% of the general population, respectively.1,2 Referred knee pain secondary to hip pathology, also known as atypical knee pain, has been cited at highly variable rates, ranging from 2% to 27%.3

Eighty-six percent of patients with atypical knee pain experience a delay in diagnosis of more than 1 year.4 Half of these patients require the use of a wheelchair or walker for community navigation.4 These findings highlight the impact that a delay in diagnosis can have on the day-to-day quality of life for these patients. Also, delayed or missed diagnoses may have contributed to the doubling in the rate of knee replacement surgery from 2000 to 2010 and the reports that up to one-third of knee replacement surgeries did not meet appropriate criteria to be performed.5,6

Convergence confusion

Referred pain is likely explained by the convergence of nociceptive and non-nociceptive nerve fibers.7 Both of these fiber types conduct action potentials that terminate at second order neurons. Occasionally, nociceptive nerve fibers from different parts of the body (ie, knee and hip) terminate at the same second order fiber. At this point of convergence, higher brain centers lose their ability to discriminate the anatomic location of origin. This results in the perception of pain in a different location, where there is no intrinsic pathology.

Patients with hip OA report that the most common locations of pain are the groin, anterior thigh, buttock, anterior knee, and greater trochanter.3 One small study revealed that 85% of patients with referred pain who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) reported complete resolution of pain symptoms within 4 days of the procedure.3

Continue to: A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

As with any musculoskeletal complaint, history and physical examination should include a focus on the joints proximal and distal to the purported joint of concern. When the hip is in consideration, historical inquiry should focus on degree and timeline of pain, stiffness, and traumatic history. Our patient reported difficulty donning socks, an excellent screening question to evaluate loss of range of motion in the hip. On physical examination, the FABER and FADIR maneuvers are quite specific to hip OA. A comprehensive list of history and physical examination findings can be found in the TABLE.

The differential includes a broad range of musculoskeletal diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for knee pain includes knee OA, spinopelvic pathology, infection, and rheumatologic disease.

Knee OA can be confirmed with knee radiographs, but one must also assess the joint above and below, as with all musculoskeletal complaints.

Spinopelvic pathology may be established with radiographs and a thorough nervous system exam.

Infection, such as septic arthritis or gout, can be diagnosed through radiographs, physical exam, and lab tests to evaluate white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels. High clinical suspicion may warrant a joint aspiration.

Continue to: Rheumatologic disease

Rheumatologic disease can be evaluated with a comprehensive physical exam, as well as lab work.

Management includes both surgical and nonsurgical options

Hip OA can be managed much like OA in other areas of the body. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines provide direction and insight concerning outpatient nonsurgical management.8 Weight loss and land-based, low-impact exercise programs are excellent first-line options. Second-line therapies include symptomatic management with systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients without contraindications. (Topical NSAIDs, while useful in the treatment of knee OA, are not as effective for hip OA due to thickness of soft tissue in this area of the body.)

Patients who do not achieve symptomatic relief with these first- and second-line therapies may benefit from other nonoperative measures, such as intra-articular corticosteroid injections. If pain persists, patients may need a referral to an orthopedic surgeon to discuss surgical candidacy.

Following the x-ray, our patient received a fluoroscopic guided intra-articular hip joint anesthetic and corticosteroid injection. Her pain level went from a reported6/10 prior to the procedure to complete pain relief after it.

However, at her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the patient reported return of functionally limiting pain. The orthopedic surgeon talked to the patient about the potential risks and benefits of THA. She elected to proceed with a right THA.

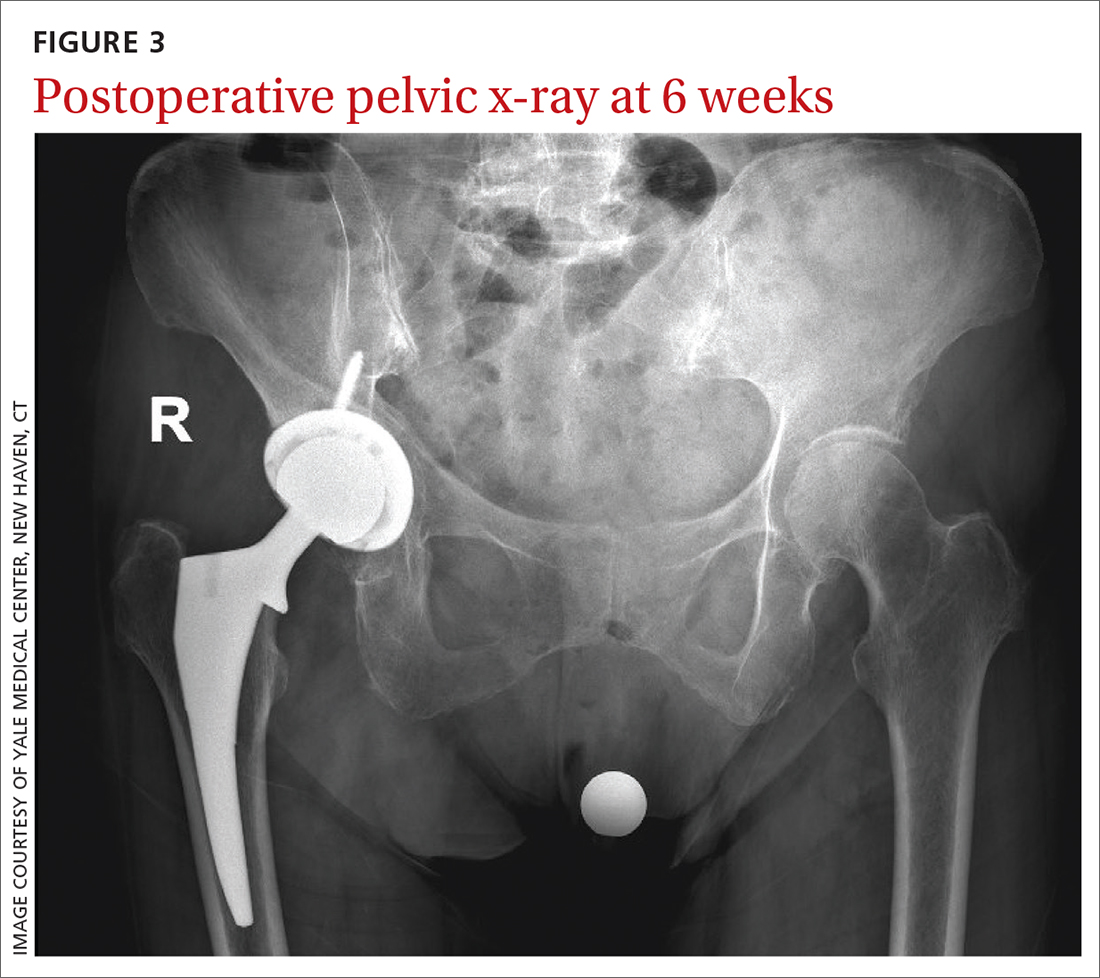

Six weeks after the surgery, the patient presented for follow-up with minimal hip pain and complete resolution of her knee pain (FIGURE 3). Functionally, she found it much easier to stand straight, and she was able to climb the stairs in her house independently.

1. Fernandes GS, Parekh SM, Moses J, et al. Prevalence of knee pain, radiographic osteoarthritis and arthroplasty in retired professional footballers compared with men in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:678-683. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097503

2. Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, et al. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:345-348.

3. Hsieh PH, Chang Y, Chen DW, et al. Pain distribution and response to total hip arthroplasty: a prospective observational study in 113 patients with end-stage hip disease. J Orthop Sci. 2012;17:213-218. doi: 10.1007/s00776-012-0204-1

4. Dibra FF, Prietao HA, Gray CF, et al. Don’t forget the hip! Hip arthritis masquerading as knee pain. Arthroplast Today. 2017;4:118-124. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2017.06.008

5. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1323-1330. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763

6. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1386-1397. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

7. Sessle BJ. Central mechanisms of craniofacial musculoskeletal pain: a review. In: Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Mense S, eds. Fundamentals of musculoskeletal pain. 1st ed. IASP Press; 2008:87-103.

8. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27:1578-1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011

An 83-year-old woman, with an otherwise noncontributory past medical history, presented with chronic right knee pain. Over the prior 4 years, she had undergone evaluation by an outside physician and received several corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections, without symptom resolution. She described the pain as a 4/10 at rest and as “severe” when climbing stairs and exercising. The pain was localized to her lower back and right groin and extended to her right knee. She also said that she found it difficult to put on her socks. An outside orthopedic surgeon recommended right total knee arthroplasty, prompting her to seek a second opinion.

Examination of her right knee was unrevealing. However, during the hip examination, there was a pronounced loss of range of motion and concordant pain reproduction with the FABER (combined flexion, abduction, external rotation) and FADIR (combined flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) maneuvers.

The patient’s extensive clinical and diagnostic history, combined with benign knee examination and imaging (FIGURE 1), ruled out isolated knee pathology.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Right hip OA with referred knee pain

The patient’s history and physical exam prompted us to suspect right hip osteoarthritis (OA) with referred pain to the right knee. This suspicion was confirmed with hip radiographs (FIGURE 2), which revealed significant OA of the right hip, as evidenced by marked joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes. There was also superior migration of the right femoral head relative to the acetabulum. Additionally, there was loss of sphericity of the right femoral head, suggesting avascular necrosis with collapse.

Hip and knee OA are among the most common causes of disability worldwide. Knee and hip pain are estimated to affect up to 27% and 15% of the general population, respectively.1,2 Referred knee pain secondary to hip pathology, also known as atypical knee pain, has been cited at highly variable rates, ranging from 2% to 27%.3

Eighty-six percent of patients with atypical knee pain experience a delay in diagnosis of more than 1 year.4 Half of these patients require the use of a wheelchair or walker for community navigation.4 These findings highlight the impact that a delay in diagnosis can have on the day-to-day quality of life for these patients. Also, delayed or missed diagnoses may have contributed to the doubling in the rate of knee replacement surgery from 2000 to 2010 and the reports that up to one-third of knee replacement surgeries did not meet appropriate criteria to be performed.5,6

Convergence confusion