User login

Unilateral eye irritation

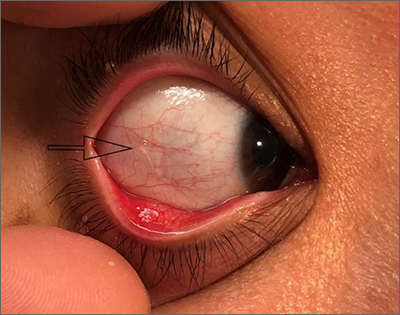

Physical examination revealed an irregularly shaped conjunctival cyst on the lateral (temporal) field of the right eye. (This diagnosis is usually made based on the clinical examination alone.)

Primary care physicians encounter patients with a variety of eye conditions; pruritis and foreign body sensation are among the most common complaints.1 While viral or allergic conjunctivitis is often to blame for “itchy eyes,” the cause can also be a conjunctival mass.

Conjunctival masses can be divided into 2 groups: solid tumors or cysts.2 Conjunctival cysts form due to trauma, infection, or inflammation that disrupts the conjunctival epithelium. They can be congenital or acquired (more common) and are rarely caused by over-the-counter eye drops.2,3 The differential diagnosis for a conjunctival cyst includes conjunctival bleb, pinguecula, pterygium, pyogenic granuloma, and tumors of the conjunctiva. An external eye exam plus a slit-lamp examination can help confirm the diagnosis.

Small, asymptomatic conjunctival cysts will mostly resolve on their own and can be managed conservatively with lubricating eye drops.3 When inflammation surrounds the cyst, short-term use of a mild topical corticosteroid is reasonable.2 Simple needle aspiration can be performed but may lead to recurrence of the cyst. Lesions larger than 15 mm, or those that have grown or changed, should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist for biopsy and further management.2,3

After a discussion of the benefits and risks of different approaches, this patient decided on conservative management. Supportive care with lubricating eye drops was started. At her 1-month follow-up, all symptoms had resolved.

Photos courtesy of Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH. Text courtesy of Amy S. Li, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Jennifer Cogburn, MD, and Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver

1. Pflipsen M, Massaquoi M, Wolf S. Evaluation of the painful eye. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Jun 15;93:991-998.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:1930-1948. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2040_19

3. Olivier JF. Common conjunctival lesions. S Afr J CPD. 2013;31:134-137.

Physical examination revealed an irregularly shaped conjunctival cyst on the lateral (temporal) field of the right eye. (This diagnosis is usually made based on the clinical examination alone.)

Primary care physicians encounter patients with a variety of eye conditions; pruritis and foreign body sensation are among the most common complaints.1 While viral or allergic conjunctivitis is often to blame for “itchy eyes,” the cause can also be a conjunctival mass.

Conjunctival masses can be divided into 2 groups: solid tumors or cysts.2 Conjunctival cysts form due to trauma, infection, or inflammation that disrupts the conjunctival epithelium. They can be congenital or acquired (more common) and are rarely caused by over-the-counter eye drops.2,3 The differential diagnosis for a conjunctival cyst includes conjunctival bleb, pinguecula, pterygium, pyogenic granuloma, and tumors of the conjunctiva. An external eye exam plus a slit-lamp examination can help confirm the diagnosis.

Small, asymptomatic conjunctival cysts will mostly resolve on their own and can be managed conservatively with lubricating eye drops.3 When inflammation surrounds the cyst, short-term use of a mild topical corticosteroid is reasonable.2 Simple needle aspiration can be performed but may lead to recurrence of the cyst. Lesions larger than 15 mm, or those that have grown or changed, should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist for biopsy and further management.2,3

After a discussion of the benefits and risks of different approaches, this patient decided on conservative management. Supportive care with lubricating eye drops was started. At her 1-month follow-up, all symptoms had resolved.

Photos courtesy of Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH. Text courtesy of Amy S. Li, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Jennifer Cogburn, MD, and Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver

Physical examination revealed an irregularly shaped conjunctival cyst on the lateral (temporal) field of the right eye. (This diagnosis is usually made based on the clinical examination alone.)

Primary care physicians encounter patients with a variety of eye conditions; pruritis and foreign body sensation are among the most common complaints.1 While viral or allergic conjunctivitis is often to blame for “itchy eyes,” the cause can also be a conjunctival mass.

Conjunctival masses can be divided into 2 groups: solid tumors or cysts.2 Conjunctival cysts form due to trauma, infection, or inflammation that disrupts the conjunctival epithelium. They can be congenital or acquired (more common) and are rarely caused by over-the-counter eye drops.2,3 The differential diagnosis for a conjunctival cyst includes conjunctival bleb, pinguecula, pterygium, pyogenic granuloma, and tumors of the conjunctiva. An external eye exam plus a slit-lamp examination can help confirm the diagnosis.

Small, asymptomatic conjunctival cysts will mostly resolve on their own and can be managed conservatively with lubricating eye drops.3 When inflammation surrounds the cyst, short-term use of a mild topical corticosteroid is reasonable.2 Simple needle aspiration can be performed but may lead to recurrence of the cyst. Lesions larger than 15 mm, or those that have grown or changed, should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist for biopsy and further management.2,3

After a discussion of the benefits and risks of different approaches, this patient decided on conservative management. Supportive care with lubricating eye drops was started. At her 1-month follow-up, all symptoms had resolved.

Photos courtesy of Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH. Text courtesy of Amy S. Li, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Jennifer Cogburn, MD, and Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver

1. Pflipsen M, Massaquoi M, Wolf S. Evaluation of the painful eye. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Jun 15;93:991-998.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:1930-1948. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2040_19

3. Olivier JF. Common conjunctival lesions. S Afr J CPD. 2013;31:134-137.

1. Pflipsen M, Massaquoi M, Wolf S. Evaluation of the painful eye. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Jun 15;93:991-998.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:1930-1948. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2040_19

3. Olivier JF. Common conjunctival lesions. S Afr J CPD. 2013;31:134-137.

Scaly rash

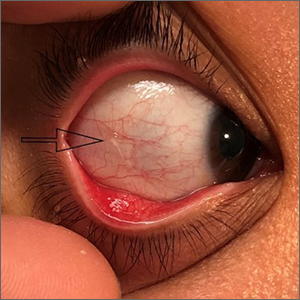

Scaly plaques on sun-exposed skin with hyperpigmentation and dyspigmentation are classic signs of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). (The dyspigmentation seen in this case signaled that she likely had chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus [CCLE]—a subtype of CLE.) At the patient’s follow-up primary care visit, her antinuclear antibodies titer was 1:1280 (≥ 1:160 is considered a positive test) and her 24-hour urine protein was 1188 mg (normal levels in adults, < 150 mg/d). In light of the patient’s joint pain, lab findings, and skin manifestations, she was also given a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Lupus erythematosus has an increased prevalence in women and typically occurs between the ages of 20 to 50 years.1 The incidence and prevalence of this condition is also greater in Black patients. CLE can either occur with SLE or independently. Patients with CLE should be monitored for the development of SLE. A diagnosis of CLE is based mainly on clinical features; biopsy is only indicated if there is a high degree of uncertainty.

Patients with CLE may suffer from a lower quality of life compared to patients with other dermatologic conditions due to the often disfiguring and disabling nature of the condition.1,2 Additionally, Black patients have an even higher chance of developing depressive symptoms associated with CCLE.2

Therapeutic management for CLE involves photoprotection by wearing sun-protective clothing, sunscreen, and limiting sun exposure.1 Initial treatment includes topical or intralesional corticosteroids, or topical calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic therapy is similar to that used for SLE. Oral glucocorticoids, and antimalarial agents are considered first-line systemic therapy.1 Second-line treatment includes methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, systemic retinoids, and azathioprine. Other immunosuppressive agents that are less commonly used include clofazimine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab.1

The patient was treated sequentially with trials of oral azathioprine 50 mg bid, then prednisone 10 mg once daily, and then hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily, without significant change in her condition. Additionally, topical steroids did not improve the patient’s symptoms. She was subsequently started on rituximab 1000 mg intravenously with a second dose repeated 2 weeks later, and another treatment 6 months after that. One year after her visit to the ED, the patient was experiencing marked improvement in her lesions.

Photo courtesy of Christy Nwankwo BA. Text courtesy of Christy Nwankwo, BA, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

1. Hejazi EZ, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: an update on pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:135-146. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0173-9

2. Hong J, Aspey L, Bao G, et al. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus: depression burden and associated factors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:465-475. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00429-7

Scaly plaques on sun-exposed skin with hyperpigmentation and dyspigmentation are classic signs of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). (The dyspigmentation seen in this case signaled that she likely had chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus [CCLE]—a subtype of CLE.) At the patient’s follow-up primary care visit, her antinuclear antibodies titer was 1:1280 (≥ 1:160 is considered a positive test) and her 24-hour urine protein was 1188 mg (normal levels in adults, < 150 mg/d). In light of the patient’s joint pain, lab findings, and skin manifestations, she was also given a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Lupus erythematosus has an increased prevalence in women and typically occurs between the ages of 20 to 50 years.1 The incidence and prevalence of this condition is also greater in Black patients. CLE can either occur with SLE or independently. Patients with CLE should be monitored for the development of SLE. A diagnosis of CLE is based mainly on clinical features; biopsy is only indicated if there is a high degree of uncertainty.

Patients with CLE may suffer from a lower quality of life compared to patients with other dermatologic conditions due to the often disfiguring and disabling nature of the condition.1,2 Additionally, Black patients have an even higher chance of developing depressive symptoms associated with CCLE.2

Therapeutic management for CLE involves photoprotection by wearing sun-protective clothing, sunscreen, and limiting sun exposure.1 Initial treatment includes topical or intralesional corticosteroids, or topical calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic therapy is similar to that used for SLE. Oral glucocorticoids, and antimalarial agents are considered first-line systemic therapy.1 Second-line treatment includes methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, systemic retinoids, and azathioprine. Other immunosuppressive agents that are less commonly used include clofazimine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab.1

The patient was treated sequentially with trials of oral azathioprine 50 mg bid, then prednisone 10 mg once daily, and then hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily, without significant change in her condition. Additionally, topical steroids did not improve the patient’s symptoms. She was subsequently started on rituximab 1000 mg intravenously with a second dose repeated 2 weeks later, and another treatment 6 months after that. One year after her visit to the ED, the patient was experiencing marked improvement in her lesions.

Photo courtesy of Christy Nwankwo BA. Text courtesy of Christy Nwankwo, BA, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Scaly plaques on sun-exposed skin with hyperpigmentation and dyspigmentation are classic signs of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). (The dyspigmentation seen in this case signaled that she likely had chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus [CCLE]—a subtype of CLE.) At the patient’s follow-up primary care visit, her antinuclear antibodies titer was 1:1280 (≥ 1:160 is considered a positive test) and her 24-hour urine protein was 1188 mg (normal levels in adults, < 150 mg/d). In light of the patient’s joint pain, lab findings, and skin manifestations, she was also given a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Lupus erythematosus has an increased prevalence in women and typically occurs between the ages of 20 to 50 years.1 The incidence and prevalence of this condition is also greater in Black patients. CLE can either occur with SLE or independently. Patients with CLE should be monitored for the development of SLE. A diagnosis of CLE is based mainly on clinical features; biopsy is only indicated if there is a high degree of uncertainty.

Patients with CLE may suffer from a lower quality of life compared to patients with other dermatologic conditions due to the often disfiguring and disabling nature of the condition.1,2 Additionally, Black patients have an even higher chance of developing depressive symptoms associated with CCLE.2

Therapeutic management for CLE involves photoprotection by wearing sun-protective clothing, sunscreen, and limiting sun exposure.1 Initial treatment includes topical or intralesional corticosteroids, or topical calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic therapy is similar to that used for SLE. Oral glucocorticoids, and antimalarial agents are considered first-line systemic therapy.1 Second-line treatment includes methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, systemic retinoids, and azathioprine. Other immunosuppressive agents that are less commonly used include clofazimine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab.1

The patient was treated sequentially with trials of oral azathioprine 50 mg bid, then prednisone 10 mg once daily, and then hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily, without significant change in her condition. Additionally, topical steroids did not improve the patient’s symptoms. She was subsequently started on rituximab 1000 mg intravenously with a second dose repeated 2 weeks later, and another treatment 6 months after that. One year after her visit to the ED, the patient was experiencing marked improvement in her lesions.

Photo courtesy of Christy Nwankwo BA. Text courtesy of Christy Nwankwo, BA, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

1. Hejazi EZ, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: an update on pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:135-146. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0173-9

2. Hong J, Aspey L, Bao G, et al. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus: depression burden and associated factors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:465-475. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00429-7

1. Hejazi EZ, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: an update on pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:135-146. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0173-9

2. Hong J, Aspey L, Bao G, et al. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus: depression burden and associated factors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:465-475. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00429-7

A case of cold, purple toes

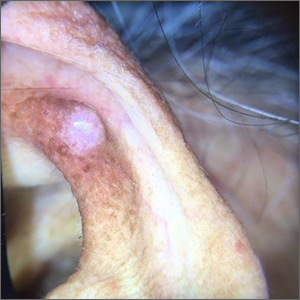

A punch-biopsy was performed on the left second toe where the erythema was the most intense. It demonstrated classic findings for pernio: superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and papillary dermal edema on the acral surface.

Pernio, alternatively known as chilblains, is characterized by erythema, violaceous changes, and swelling at acral sites (especially the toes or fingers). There can also be blistering, pain/tenderness, and itch. Pernio results in an abnormal localized inflammatory response to nonfreezing cold and is more common in damp climates. Pernio may also occur in occupational settings where patients handle frozen food. When a patient presents with the classic findings and consistent history, biopsy is not strictly necessary, but can aid in a definitive diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of pernio is not clearly understood. Inflammation secondary to vasospasm and type I interferon immune response to repeated or chronic cold exposure likely play a significant role. Symptoms can arise within 24 hours of exposure and resolve just as quickly. However, persistent and repeated exposure can also trigger ongoing symptoms that last for weeks.

As with most autoinflammatory conditions, pernio has a proclivity to affect younger women. It also affects children and the elderly. Because it is an inflammatory response to nonfreezing cold temperatures, the disease tends to occur during autumn in patients who live in homes without central heating.

A diagnosis of idiopathic pernio necessitates excluding several other similar, cold-induced entities. These include acrocyanosis (due to erythromelalgia, anorexia, medications), Raynaud phenomenon, cryoglobulinemia, cold urticaria, and chilblain lupus (among others). Pernio tends to lack other clinical findings such as true retiform purpura.

Of note, during the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians identified a spike in the incidence of pernio-like acral eruptions. This phenomenon has been coined “COVID toes.” While the direct temporal and causal relationships between COVID-19 and the observed eruption has not been clearly established, any patient who presents with a new onset pernio-like eruption should receive a COVID-19 test to ensure proper precautions are followed.1

In our patient, the work-up did not show any evidence of other underlying conditions. As her symptoms were minimal, we provided reassurance and counseling on preventive measures such as keeping her hands and feet warm and dry. In cases where treatment is needed, high-potency topical corticosteroids can be utilized judiciously during flares to decrease local inflammation. (There is minimal concern for adverse effects due to the thicker skin on acral surfaces.) Another treatment option is oral nifedipine (20-60 mg/d). One double-blinded trial showed it can improve symptoms in up to 70% of patients.2

Clinical image courtesy of Jiasen Wang, MD; microscopy image courtesy of Shelly Stepenaskie, MD. Text courtesy of Jiasen Wang, MD, Aimee Smidt, MD, Shelly Stepenaskie, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Cappel MA, Cappel JA, Wetter DA. Pernio (Chilblains), SARS-CoV-2, and covid toes unified through cutaneous and systemic mechanisms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:989-1005. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.01.009

2. Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e472-e475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2681

A punch-biopsy was performed on the left second toe where the erythema was the most intense. It demonstrated classic findings for pernio: superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and papillary dermal edema on the acral surface.

Pernio, alternatively known as chilblains, is characterized by erythema, violaceous changes, and swelling at acral sites (especially the toes or fingers). There can also be blistering, pain/tenderness, and itch. Pernio results in an abnormal localized inflammatory response to nonfreezing cold and is more common in damp climates. Pernio may also occur in occupational settings where patients handle frozen food. When a patient presents with the classic findings and consistent history, biopsy is not strictly necessary, but can aid in a definitive diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of pernio is not clearly understood. Inflammation secondary to vasospasm and type I interferon immune response to repeated or chronic cold exposure likely play a significant role. Symptoms can arise within 24 hours of exposure and resolve just as quickly. However, persistent and repeated exposure can also trigger ongoing symptoms that last for weeks.

As with most autoinflammatory conditions, pernio has a proclivity to affect younger women. It also affects children and the elderly. Because it is an inflammatory response to nonfreezing cold temperatures, the disease tends to occur during autumn in patients who live in homes without central heating.

A diagnosis of idiopathic pernio necessitates excluding several other similar, cold-induced entities. These include acrocyanosis (due to erythromelalgia, anorexia, medications), Raynaud phenomenon, cryoglobulinemia, cold urticaria, and chilblain lupus (among others). Pernio tends to lack other clinical findings such as true retiform purpura.

Of note, during the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians identified a spike in the incidence of pernio-like acral eruptions. This phenomenon has been coined “COVID toes.” While the direct temporal and causal relationships between COVID-19 and the observed eruption has not been clearly established, any patient who presents with a new onset pernio-like eruption should receive a COVID-19 test to ensure proper precautions are followed.1

In our patient, the work-up did not show any evidence of other underlying conditions. As her symptoms were minimal, we provided reassurance and counseling on preventive measures such as keeping her hands and feet warm and dry. In cases where treatment is needed, high-potency topical corticosteroids can be utilized judiciously during flares to decrease local inflammation. (There is minimal concern for adverse effects due to the thicker skin on acral surfaces.) Another treatment option is oral nifedipine (20-60 mg/d). One double-blinded trial showed it can improve symptoms in up to 70% of patients.2

Clinical image courtesy of Jiasen Wang, MD; microscopy image courtesy of Shelly Stepenaskie, MD. Text courtesy of Jiasen Wang, MD, Aimee Smidt, MD, Shelly Stepenaskie, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

A punch-biopsy was performed on the left second toe where the erythema was the most intense. It demonstrated classic findings for pernio: superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and papillary dermal edema on the acral surface.

Pernio, alternatively known as chilblains, is characterized by erythema, violaceous changes, and swelling at acral sites (especially the toes or fingers). There can also be blistering, pain/tenderness, and itch. Pernio results in an abnormal localized inflammatory response to nonfreezing cold and is more common in damp climates. Pernio may also occur in occupational settings where patients handle frozen food. When a patient presents with the classic findings and consistent history, biopsy is not strictly necessary, but can aid in a definitive diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of pernio is not clearly understood. Inflammation secondary to vasospasm and type I interferon immune response to repeated or chronic cold exposure likely play a significant role. Symptoms can arise within 24 hours of exposure and resolve just as quickly. However, persistent and repeated exposure can also trigger ongoing symptoms that last for weeks.

As with most autoinflammatory conditions, pernio has a proclivity to affect younger women. It also affects children and the elderly. Because it is an inflammatory response to nonfreezing cold temperatures, the disease tends to occur during autumn in patients who live in homes without central heating.

A diagnosis of idiopathic pernio necessitates excluding several other similar, cold-induced entities. These include acrocyanosis (due to erythromelalgia, anorexia, medications), Raynaud phenomenon, cryoglobulinemia, cold urticaria, and chilblain lupus (among others). Pernio tends to lack other clinical findings such as true retiform purpura.

Of note, during the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians identified a spike in the incidence of pernio-like acral eruptions. This phenomenon has been coined “COVID toes.” While the direct temporal and causal relationships between COVID-19 and the observed eruption has not been clearly established, any patient who presents with a new onset pernio-like eruption should receive a COVID-19 test to ensure proper precautions are followed.1

In our patient, the work-up did not show any evidence of other underlying conditions. As her symptoms were minimal, we provided reassurance and counseling on preventive measures such as keeping her hands and feet warm and dry. In cases where treatment is needed, high-potency topical corticosteroids can be utilized judiciously during flares to decrease local inflammation. (There is minimal concern for adverse effects due to the thicker skin on acral surfaces.) Another treatment option is oral nifedipine (20-60 mg/d). One double-blinded trial showed it can improve symptoms in up to 70% of patients.2

Clinical image courtesy of Jiasen Wang, MD; microscopy image courtesy of Shelly Stepenaskie, MD. Text courtesy of Jiasen Wang, MD, Aimee Smidt, MD, Shelly Stepenaskie, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Cappel MA, Cappel JA, Wetter DA. Pernio (Chilblains), SARS-CoV-2, and covid toes unified through cutaneous and systemic mechanisms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:989-1005. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.01.009

2. Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e472-e475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2681

1. Cappel MA, Cappel JA, Wetter DA. Pernio (Chilblains), SARS-CoV-2, and covid toes unified through cutaneous and systemic mechanisms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:989-1005. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.01.009

2. Simon TD, Soep JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e472-e475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2681

Nonhealing boils

A healthy woman in her 60s presented to the clinic with a 1-month history of red, itchy, and slightly painful nodules on the scalp and back. The patient had travelled to Belize for a vacation in the weeks prior to the onset of the lesions. She was initially given a course of cephalexin for presumed furunculosis at another clinic, without improvement.

Examination revealed inflamed nodules with a central open pore on the left upper back (FIGURE 1) and the occipital scalp. Notably, when the lesions were observed with a dermatoscope, intermittent air bubbles were seen through the skin opening.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Furuncular myiasis

Given the patient’s clinical presentation and travel history, furuncular myiasis infestation was suspected and confirmed by punch biopsy. Pathologic exam revealed botfly larvae in both wounds, consistent with the human botfly, Dermatobia hominis (FIGURE 2). Myiasis is not common in the United States but should be suspected in patients who have recently traveled to tropical or subtropical areas. Furuncular myiasis describes the condition in which fly larvae penetrate healthy skin in a localized fashion, leading to the development of a furuncle-like nodule with 1 or more larvae within it.

Dermatobia hominis is the most common causative organism for furuncular myiasis in the regions of the Americas. Patients typically present with 1 lesion on an exposed part of the body (eg, scalp, face, extremities). The lesions typically contain a central pore with purulent or serosanguinous exudate.1 Upon dermatoscopic inspection, one can often see the posterior part of the larva or the respiratory spiracles, which look like tiny black dots on the surface of the wound. The organism may also be indirectly viewed through respiratory bubble formation within the exudate.1,2 Diagnosis is confirmed by extracting the larvae from the wound and having the species identified by an experienced pathologist or parasitologist.

Mode of transmission

Phoresis is the name of the process by which Dermatobia hominis invades the skin.3 The female fly lays her eggs onto captured mosquitos using a quick-drying adhesive. The eggs are then transferred to the host by a mosquito bite. The host’s body heat induces egg hatching, and the larvae burrow into follicular openings or skin perforations. This leads to the development of a small erythematous papule, which can further lead to a furuncle-like nodule with a central pore that allows the organism to respirate. When ready to pupate, the larvae work their way to the skin surface and drop to the soil, where they can further develop. After pupation, the fly hatches and develops into an adult, and the cycle repeats.

Common infectious and inflammatory lesions are in the differential Dx

The differential diagnosis includes bacterial abscess, exaggerated arthropod reaction, and ruptured epidermal cyst. With our patient, the travel history and unique exam findings led to the suspicion of myiasis.

Bacterial abscess is likely to have more notable purulence with response to appropriate oral antibiotics and no bubbling phenomenon on exam. It is also unlikely to be present for 1 month without progressive worsening.

Continue to: Exaggerated arthropod reaction

Exaggerated arthropod reaction usually manifests as a smooth, red, papular lesion without bubble formation from a central pore.

Ruptured epidermal cyst would be considered if there was a known preexisting cyst that recently changed. No bubble formation would be observed from the central pore.

Extraction is the treatment of choice

Treatment of furuncular myiasis involves removing the larvae or forcing them out of the lesion. Wounds can be covered with a substance, such as petrolatum, nail polish, beeswax, paraffin, or mineral oil, to block respiration.3 Occlusion may be needed for 24 hours to create adequate localized hypoxia to force the larvae to migrate from the wound and allow for easier manual extraction. Surgical removal of the larvae is also effective. A cruciate incision can be made adjacent to the central pore to avoid damaging the organisms.3 A topical, broad-based antiparasitic, such as a 10% ivermectin solution, has also been successfully used to treat furuncular myiasis. This approach works by either inducing larval migration outward or simply killing the larvae.3

Our patient recovered well after we performed a punch biopsy to make a larger wound opening and remove the intact larvae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Richard Pollack, PhD, at IdentifyUS, LLC, for providing the botfly larvae photo.

1. Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:79-105. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00010-11

2. Diaz JH. The epidemiology, diagnosis, management, and prevention of ectoparasitic diseases in travelers. J Travel Med. 2006;13:100-111. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00021.x

3. McGraw TA, Turiansky GW. Cutaneous myiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:907-926. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.03.014

A healthy woman in her 60s presented to the clinic with a 1-month history of red, itchy, and slightly painful nodules on the scalp and back. The patient had travelled to Belize for a vacation in the weeks prior to the onset of the lesions. She was initially given a course of cephalexin for presumed furunculosis at another clinic, without improvement.

Examination revealed inflamed nodules with a central open pore on the left upper back (FIGURE 1) and the occipital scalp. Notably, when the lesions were observed with a dermatoscope, intermittent air bubbles were seen through the skin opening.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Furuncular myiasis

Given the patient’s clinical presentation and travel history, furuncular myiasis infestation was suspected and confirmed by punch biopsy. Pathologic exam revealed botfly larvae in both wounds, consistent with the human botfly, Dermatobia hominis (FIGURE 2). Myiasis is not common in the United States but should be suspected in patients who have recently traveled to tropical or subtropical areas. Furuncular myiasis describes the condition in which fly larvae penetrate healthy skin in a localized fashion, leading to the development of a furuncle-like nodule with 1 or more larvae within it.

Dermatobia hominis is the most common causative organism for furuncular myiasis in the regions of the Americas. Patients typically present with 1 lesion on an exposed part of the body (eg, scalp, face, extremities). The lesions typically contain a central pore with purulent or serosanguinous exudate.1 Upon dermatoscopic inspection, one can often see the posterior part of the larva or the respiratory spiracles, which look like tiny black dots on the surface of the wound. The organism may also be indirectly viewed through respiratory bubble formation within the exudate.1,2 Diagnosis is confirmed by extracting the larvae from the wound and having the species identified by an experienced pathologist or parasitologist.

Mode of transmission

Phoresis is the name of the process by which Dermatobia hominis invades the skin.3 The female fly lays her eggs onto captured mosquitos using a quick-drying adhesive. The eggs are then transferred to the host by a mosquito bite. The host’s body heat induces egg hatching, and the larvae burrow into follicular openings or skin perforations. This leads to the development of a small erythematous papule, which can further lead to a furuncle-like nodule with a central pore that allows the organism to respirate. When ready to pupate, the larvae work their way to the skin surface and drop to the soil, where they can further develop. After pupation, the fly hatches and develops into an adult, and the cycle repeats.

Common infectious and inflammatory lesions are in the differential Dx

The differential diagnosis includes bacterial abscess, exaggerated arthropod reaction, and ruptured epidermal cyst. With our patient, the travel history and unique exam findings led to the suspicion of myiasis.

Bacterial abscess is likely to have more notable purulence with response to appropriate oral antibiotics and no bubbling phenomenon on exam. It is also unlikely to be present for 1 month without progressive worsening.

Continue to: Exaggerated arthropod reaction

Exaggerated arthropod reaction usually manifests as a smooth, red, papular lesion without bubble formation from a central pore.

Ruptured epidermal cyst would be considered if there was a known preexisting cyst that recently changed. No bubble formation would be observed from the central pore.

Extraction is the treatment of choice

Treatment of furuncular myiasis involves removing the larvae or forcing them out of the lesion. Wounds can be covered with a substance, such as petrolatum, nail polish, beeswax, paraffin, or mineral oil, to block respiration.3 Occlusion may be needed for 24 hours to create adequate localized hypoxia to force the larvae to migrate from the wound and allow for easier manual extraction. Surgical removal of the larvae is also effective. A cruciate incision can be made adjacent to the central pore to avoid damaging the organisms.3 A topical, broad-based antiparasitic, such as a 10% ivermectin solution, has also been successfully used to treat furuncular myiasis. This approach works by either inducing larval migration outward or simply killing the larvae.3

Our patient recovered well after we performed a punch biopsy to make a larger wound opening and remove the intact larvae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Richard Pollack, PhD, at IdentifyUS, LLC, for providing the botfly larvae photo.

A healthy woman in her 60s presented to the clinic with a 1-month history of red, itchy, and slightly painful nodules on the scalp and back. The patient had travelled to Belize for a vacation in the weeks prior to the onset of the lesions. She was initially given a course of cephalexin for presumed furunculosis at another clinic, without improvement.

Examination revealed inflamed nodules with a central open pore on the left upper back (FIGURE 1) and the occipital scalp. Notably, when the lesions were observed with a dermatoscope, intermittent air bubbles were seen through the skin opening.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Furuncular myiasis

Given the patient’s clinical presentation and travel history, furuncular myiasis infestation was suspected and confirmed by punch biopsy. Pathologic exam revealed botfly larvae in both wounds, consistent with the human botfly, Dermatobia hominis (FIGURE 2). Myiasis is not common in the United States but should be suspected in patients who have recently traveled to tropical or subtropical areas. Furuncular myiasis describes the condition in which fly larvae penetrate healthy skin in a localized fashion, leading to the development of a furuncle-like nodule with 1 or more larvae within it.

Dermatobia hominis is the most common causative organism for furuncular myiasis in the regions of the Americas. Patients typically present with 1 lesion on an exposed part of the body (eg, scalp, face, extremities). The lesions typically contain a central pore with purulent or serosanguinous exudate.1 Upon dermatoscopic inspection, one can often see the posterior part of the larva or the respiratory spiracles, which look like tiny black dots on the surface of the wound. The organism may also be indirectly viewed through respiratory bubble formation within the exudate.1,2 Diagnosis is confirmed by extracting the larvae from the wound and having the species identified by an experienced pathologist or parasitologist.

Mode of transmission

Phoresis is the name of the process by which Dermatobia hominis invades the skin.3 The female fly lays her eggs onto captured mosquitos using a quick-drying adhesive. The eggs are then transferred to the host by a mosquito bite. The host’s body heat induces egg hatching, and the larvae burrow into follicular openings or skin perforations. This leads to the development of a small erythematous papule, which can further lead to a furuncle-like nodule with a central pore that allows the organism to respirate. When ready to pupate, the larvae work their way to the skin surface and drop to the soil, where they can further develop. After pupation, the fly hatches and develops into an adult, and the cycle repeats.

Common infectious and inflammatory lesions are in the differential Dx

The differential diagnosis includes bacterial abscess, exaggerated arthropod reaction, and ruptured epidermal cyst. With our patient, the travel history and unique exam findings led to the suspicion of myiasis.

Bacterial abscess is likely to have more notable purulence with response to appropriate oral antibiotics and no bubbling phenomenon on exam. It is also unlikely to be present for 1 month without progressive worsening.

Continue to: Exaggerated arthropod reaction

Exaggerated arthropod reaction usually manifests as a smooth, red, papular lesion without bubble formation from a central pore.

Ruptured epidermal cyst would be considered if there was a known preexisting cyst that recently changed. No bubble formation would be observed from the central pore.

Extraction is the treatment of choice

Treatment of furuncular myiasis involves removing the larvae or forcing them out of the lesion. Wounds can be covered with a substance, such as petrolatum, nail polish, beeswax, paraffin, or mineral oil, to block respiration.3 Occlusion may be needed for 24 hours to create adequate localized hypoxia to force the larvae to migrate from the wound and allow for easier manual extraction. Surgical removal of the larvae is also effective. A cruciate incision can be made adjacent to the central pore to avoid damaging the organisms.3 A topical, broad-based antiparasitic, such as a 10% ivermectin solution, has also been successfully used to treat furuncular myiasis. This approach works by either inducing larval migration outward or simply killing the larvae.3

Our patient recovered well after we performed a punch biopsy to make a larger wound opening and remove the intact larvae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Richard Pollack, PhD, at IdentifyUS, LLC, for providing the botfly larvae photo.

1. Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:79-105. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00010-11

2. Diaz JH. The epidemiology, diagnosis, management, and prevention of ectoparasitic diseases in travelers. J Travel Med. 2006;13:100-111. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00021.x

3. McGraw TA, Turiansky GW. Cutaneous myiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:907-926. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.03.014

1. Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:79-105. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00010-11

2. Diaz JH. The epidemiology, diagnosis, management, and prevention of ectoparasitic diseases in travelers. J Travel Med. 2006;13:100-111. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00021.x

3. McGraw TA, Turiansky GW. Cutaneous myiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:907-926. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.03.014

Bilateral palmar rash

A biopsy was performed and the pathology report showed ectatic, thin-walled vessels consistent with telangiectasias. There were no other inflammatory, infectious, or malignant changes.

Telangiectasias are caused by permanent dilatation of subpapillary plexus end vessels. Unlike petechiae and angiomata, telangiectasias blanch with pressure. They usually manifest as small, bright red, nonpulsatile vascular lesions with a fine, netlike pattern on the surface of the skin. Telangiectasis can affect many organs (eg, intestines, bladder, brain, eyes) and may occur in patients with certain genetic disorders and environmental exposures (eg, radiation).1

Palmar telangiectasias are specifically associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, dermatomyositis, Grave disease, CREST syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and smoking.2 Sun exposure and smoking are the main risk factors for the development of telangiectasias.1

This patient had no history of autoimmune disease or hyperthyroidism, and no one in her family had telangiectasis. Thus, the likely cause of her lesions was smoking. While the pathophysiology is not fully understood, it is likely related to the vasoconstrictive quality of nicotine, causing ischemia in the dermis. This chronic, low-grade ischemia may trigger the compensatory development of telangiectasias.2

This patient was informed that her telangiectasias were most likely caused by her smoking and that the lesions themselves did not require treatment. She was encouraged to continue her smoking cessation efforts with her primary care provider.

Photos courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Mia MJ Coleman, BA, BS, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Schieving JH, Shoenaker MHD, Weemaes CM, et al. Telangiectasias: Small lesions referring to serious disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017;21:807-815. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.07.016

2. Levi A, Shechter R, Lapidoth M, et al. Palmar telangiectasias: a cutaneous sign for smoking. Dermatology. 2017;233:390-395. doi: 10.1159/000481855

A biopsy was performed and the pathology report showed ectatic, thin-walled vessels consistent with telangiectasias. There were no other inflammatory, infectious, or malignant changes.

Telangiectasias are caused by permanent dilatation of subpapillary plexus end vessels. Unlike petechiae and angiomata, telangiectasias blanch with pressure. They usually manifest as small, bright red, nonpulsatile vascular lesions with a fine, netlike pattern on the surface of the skin. Telangiectasis can affect many organs (eg, intestines, bladder, brain, eyes) and may occur in patients with certain genetic disorders and environmental exposures (eg, radiation).1

Palmar telangiectasias are specifically associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, dermatomyositis, Grave disease, CREST syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and smoking.2 Sun exposure and smoking are the main risk factors for the development of telangiectasias.1

This patient had no history of autoimmune disease or hyperthyroidism, and no one in her family had telangiectasis. Thus, the likely cause of her lesions was smoking. While the pathophysiology is not fully understood, it is likely related to the vasoconstrictive quality of nicotine, causing ischemia in the dermis. This chronic, low-grade ischemia may trigger the compensatory development of telangiectasias.2

This patient was informed that her telangiectasias were most likely caused by her smoking and that the lesions themselves did not require treatment. She was encouraged to continue her smoking cessation efforts with her primary care provider.

Photos courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Mia MJ Coleman, BA, BS, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

A biopsy was performed and the pathology report showed ectatic, thin-walled vessels consistent with telangiectasias. There were no other inflammatory, infectious, or malignant changes.

Telangiectasias are caused by permanent dilatation of subpapillary plexus end vessels. Unlike petechiae and angiomata, telangiectasias blanch with pressure. They usually manifest as small, bright red, nonpulsatile vascular lesions with a fine, netlike pattern on the surface of the skin. Telangiectasis can affect many organs (eg, intestines, bladder, brain, eyes) and may occur in patients with certain genetic disorders and environmental exposures (eg, radiation).1

Palmar telangiectasias are specifically associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, dermatomyositis, Grave disease, CREST syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and smoking.2 Sun exposure and smoking are the main risk factors for the development of telangiectasias.1

This patient had no history of autoimmune disease or hyperthyroidism, and no one in her family had telangiectasis. Thus, the likely cause of her lesions was smoking. While the pathophysiology is not fully understood, it is likely related to the vasoconstrictive quality of nicotine, causing ischemia in the dermis. This chronic, low-grade ischemia may trigger the compensatory development of telangiectasias.2

This patient was informed that her telangiectasias were most likely caused by her smoking and that the lesions themselves did not require treatment. She was encouraged to continue her smoking cessation efforts with her primary care provider.

Photos courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Mia MJ Coleman, BA, BS, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Schieving JH, Shoenaker MHD, Weemaes CM, et al. Telangiectasias: Small lesions referring to serious disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017;21:807-815. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.07.016

2. Levi A, Shechter R, Lapidoth M, et al. Palmar telangiectasias: a cutaneous sign for smoking. Dermatology. 2017;233:390-395. doi: 10.1159/000481855

1. Schieving JH, Shoenaker MHD, Weemaes CM, et al. Telangiectasias: Small lesions referring to serious disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017;21:807-815. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.07.016

2. Levi A, Shechter R, Lapidoth M, et al. Palmar telangiectasias: a cutaneous sign for smoking. Dermatology. 2017;233:390-395. doi: 10.1159/000481855

Ear growth

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed and it confirmed the diagnosis of chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis (CNH).

CNH is an inflammatory process that most commonly occurs on the helix of the ear but can also occur on the antihelix and, rarely, on other areas of the ear. It generally manifests as a firm nodule with surrounding erythema that may be painful only when pressure is applied. Patients may describe bleeding, ulceration, and exudate. They will usually report discomfort from sleeping on the affected side.

The pathogenesis of CNH is poorly understood but is thought to be related to vasculitis and inflammation from prolonged pressure to the affected ear during sleep or from devices that are worn in or around the ear (eg, hearing aids, headphones). Other factors such as actinic damage or ear trauma have also been described. Histopathologic studies have identified arteriolar narrowing with ischemic changes and necrosis of cartilage causing localized inflammation.1

The differential diagnosis for this lesion includes nonmelanoma skin cancer, as well as tophaceous gout and seborrheic keratosis.

There are multiple conservative treatment options. One option is to relieve pressure by sleeping on the unaffected side or using commercially available pillows with a cutout or window where the affected ear can rest. Pharmacologic treatments include topical nitroglycerin1 and intralesional collagen or corticosteroid injections. If previous treatments are unsuccessful, consider surgical excision of the affected tissue and curettage of the underlying abnormal cartilage. Recurrence is possible with both conservative and surgical treatment.

This patient was counseled on the benign nature of her biopsy findings and treatment options were discussed. She elected to proceed with pressure-relieving measures when sleeping and planned to follow up if there was no improvement.

Image courtesy of Marion Cook, MD, First Choice Community Healthcare, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Text courtesy of Spenser Squire, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Nielsen LJ, Olsen CH, Lock-Anderson J. Therapeutic options of chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. Plast Surg Int. 2016;2016:4340168. doi: 10.1155/2016/4340168

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed and it confirmed the diagnosis of chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis (CNH).

CNH is an inflammatory process that most commonly occurs on the helix of the ear but can also occur on the antihelix and, rarely, on other areas of the ear. It generally manifests as a firm nodule with surrounding erythema that may be painful only when pressure is applied. Patients may describe bleeding, ulceration, and exudate. They will usually report discomfort from sleeping on the affected side.

The pathogenesis of CNH is poorly understood but is thought to be related to vasculitis and inflammation from prolonged pressure to the affected ear during sleep or from devices that are worn in or around the ear (eg, hearing aids, headphones). Other factors such as actinic damage or ear trauma have also been described. Histopathologic studies have identified arteriolar narrowing with ischemic changes and necrosis of cartilage causing localized inflammation.1

The differential diagnosis for this lesion includes nonmelanoma skin cancer, as well as tophaceous gout and seborrheic keratosis.

There are multiple conservative treatment options. One option is to relieve pressure by sleeping on the unaffected side or using commercially available pillows with a cutout or window where the affected ear can rest. Pharmacologic treatments include topical nitroglycerin1 and intralesional collagen or corticosteroid injections. If previous treatments are unsuccessful, consider surgical excision of the affected tissue and curettage of the underlying abnormal cartilage. Recurrence is possible with both conservative and surgical treatment.

This patient was counseled on the benign nature of her biopsy findings and treatment options were discussed. She elected to proceed with pressure-relieving measures when sleeping and planned to follow up if there was no improvement.

Image courtesy of Marion Cook, MD, First Choice Community Healthcare, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Text courtesy of Spenser Squire, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed and it confirmed the diagnosis of chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis (CNH).

CNH is an inflammatory process that most commonly occurs on the helix of the ear but can also occur on the antihelix and, rarely, on other areas of the ear. It generally manifests as a firm nodule with surrounding erythema that may be painful only when pressure is applied. Patients may describe bleeding, ulceration, and exudate. They will usually report discomfort from sleeping on the affected side.

The pathogenesis of CNH is poorly understood but is thought to be related to vasculitis and inflammation from prolonged pressure to the affected ear during sleep or from devices that are worn in or around the ear (eg, hearing aids, headphones). Other factors such as actinic damage or ear trauma have also been described. Histopathologic studies have identified arteriolar narrowing with ischemic changes and necrosis of cartilage causing localized inflammation.1

The differential diagnosis for this lesion includes nonmelanoma skin cancer, as well as tophaceous gout and seborrheic keratosis.

There are multiple conservative treatment options. One option is to relieve pressure by sleeping on the unaffected side or using commercially available pillows with a cutout or window where the affected ear can rest. Pharmacologic treatments include topical nitroglycerin1 and intralesional collagen or corticosteroid injections. If previous treatments are unsuccessful, consider surgical excision of the affected tissue and curettage of the underlying abnormal cartilage. Recurrence is possible with both conservative and surgical treatment.

This patient was counseled on the benign nature of her biopsy findings and treatment options were discussed. She elected to proceed with pressure-relieving measures when sleeping and planned to follow up if there was no improvement.

Image courtesy of Marion Cook, MD, First Choice Community Healthcare, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Text courtesy of Spenser Squire, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Nielsen LJ, Olsen CH, Lock-Anderson J. Therapeutic options of chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. Plast Surg Int. 2016;2016:4340168. doi: 10.1155/2016/4340168

1. Nielsen LJ, Olsen CH, Lock-Anderson J. Therapeutic options of chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. Plast Surg Int. 2016;2016:4340168. doi: 10.1155/2016/4340168

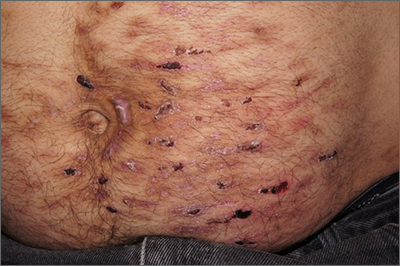

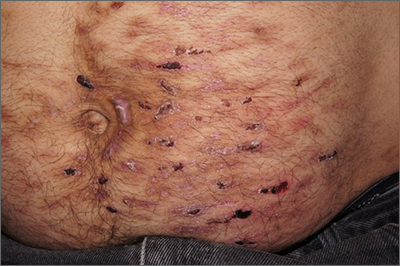

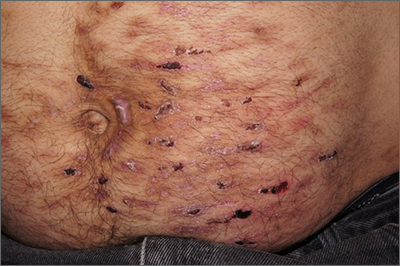

Abdominal rash

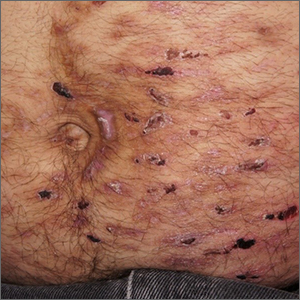

Despite his insistence that he was not scratching his abdomen, the lack of primary lesions and the appearance of horizontally oriented excoriations over the abdomen in multiple stages of healing were consistent with neurotic excoriations.

Neurotic excoriation is frequently associated with psychiatric disease, especially obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression.1 Stimulant-use, either by prescription or illicit, can lead to increased self-grooming behaviors, motor tics, and scratching. High doses of stimulants can trigger paranoia and tactile hallucinations.

In this case, the preponderance of skin lesions occurring on the left side of the patient’s abdomen fit with a right-handed individual, which the patient was. On his anterior lower legs, there were linear excoriations oriented vertically. Close observation of the patient during history taking revealed unconscious skin-picking behavior, and dead skin and debris could be noted under his fingernails. Two punch biopsies of active lesions were consistent with excoriations and excluded inflammatory causes of itching. (Careful evaluation for scabies, eczema, urticaria, and contact dermatitis was also performed.)

In this case, the patient’s psychiatrist reduced his dosage of lisdexamfetamine to a starting dose of 30 mg daily, which led to decreased skin scratching behavior. While the patient continued to have limited insight into the nature of his skin changes, progress was measured by a reduction in the number of active lesions.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

Despite his insistence that he was not scratching his abdomen, the lack of primary lesions and the appearance of horizontally oriented excoriations over the abdomen in multiple stages of healing were consistent with neurotic excoriations.

Neurotic excoriation is frequently associated with psychiatric disease, especially obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression.1 Stimulant-use, either by prescription or illicit, can lead to increased self-grooming behaviors, motor tics, and scratching. High doses of stimulants can trigger paranoia and tactile hallucinations.

In this case, the preponderance of skin lesions occurring on the left side of the patient’s abdomen fit with a right-handed individual, which the patient was. On his anterior lower legs, there were linear excoriations oriented vertically. Close observation of the patient during history taking revealed unconscious skin-picking behavior, and dead skin and debris could be noted under his fingernails. Two punch biopsies of active lesions were consistent with excoriations and excluded inflammatory causes of itching. (Careful evaluation for scabies, eczema, urticaria, and contact dermatitis was also performed.)

In this case, the patient’s psychiatrist reduced his dosage of lisdexamfetamine to a starting dose of 30 mg daily, which led to decreased skin scratching behavior. While the patient continued to have limited insight into the nature of his skin changes, progress was measured by a reduction in the number of active lesions.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Despite his insistence that he was not scratching his abdomen, the lack of primary lesions and the appearance of horizontally oriented excoriations over the abdomen in multiple stages of healing were consistent with neurotic excoriations.

Neurotic excoriation is frequently associated with psychiatric disease, especially obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression.1 Stimulant-use, either by prescription or illicit, can lead to increased self-grooming behaviors, motor tics, and scratching. High doses of stimulants can trigger paranoia and tactile hallucinations.

In this case, the preponderance of skin lesions occurring on the left side of the patient’s abdomen fit with a right-handed individual, which the patient was. On his anterior lower legs, there were linear excoriations oriented vertically. Close observation of the patient during history taking revealed unconscious skin-picking behavior, and dead skin and debris could be noted under his fingernails. Two punch biopsies of active lesions were consistent with excoriations and excluded inflammatory causes of itching. (Careful evaluation for scabies, eczema, urticaria, and contact dermatitis was also performed.)

In this case, the patient’s psychiatrist reduced his dosage of lisdexamfetamine to a starting dose of 30 mg daily, which led to decreased skin scratching behavior. While the patient continued to have limited insight into the nature of his skin changes, progress was measured by a reduction in the number of active lesions.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

1. Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

“Fishy” papule

A biopsy was performed to exclude squamous cell carcinoma and an additional biopsy was sent for tissue culture for aerobic and acid-fast bacteria. The culture revealed a surprising diagnosis: cutaneous mycobacterium marinum.

Mycobacterium marinum is one of many nontuberculosis mycobacteria that may rarely cause infections in immunocompetent patients. M marinum is found worldwide in saltwater and freshwater. Infections may occur in individuals working in fisheries or fish markets, natural marine environments, or with aquariums. The infection may gain access through small, even unnoticed breaks in the skin. Papules, pustules, or abscesses caused by M marinum develop a few weeks after exposure and share many features with other common skin infections, including Staphylococcus aureus. Lymphatic involvement and sporotrichoid spread may occur. Immunocompromised patients can experience deeper involvement into tendons. Patients with significant soft tissue pain should undergo computed tomography, or preferably magnetic resonance imaging, to determine the extent of disease.

For immunocompetent patients and those with limited disease, as in this case, spontaneous resolution can occur after a year or more. However, because of the potential risk of more severe disease, treatment is recommended. M marinum is resistant to multiple antibiotics and there are no standardized treatment guidelines. Minocycline 100 mg bid for 3 weeks to 3 months is 1 accepted regimen for limited disease; treatment should be continued for 3 to 4 weeks following clinical resolution.1 Patients with more widespread disease benefit from evaluation by Infectious Diseases. Patients exposed to atypical mycobacteria may have false positive QuantiFERON-TB Gold tests that are commonly performed prior to biologic therapies.2

This patient achieved complete resolution of his signs and symptoms after receiving minocycline 100 mg bid for 6 weeks. He continues to fish recreationally.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Rallis E, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E. Treatment of Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2965-2978. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.17.2965

2. Gajurel K, Subramanian AK. False-positive QuantiFERON TB-Gold test due to Mycobacterium gordonae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;84:315-317. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.10.020

A biopsy was performed to exclude squamous cell carcinoma and an additional biopsy was sent for tissue culture for aerobic and acid-fast bacteria. The culture revealed a surprising diagnosis: cutaneous mycobacterium marinum.

Mycobacterium marinum is one of many nontuberculosis mycobacteria that may rarely cause infections in immunocompetent patients. M marinum is found worldwide in saltwater and freshwater. Infections may occur in individuals working in fisheries or fish markets, natural marine environments, or with aquariums. The infection may gain access through small, even unnoticed breaks in the skin. Papules, pustules, or abscesses caused by M marinum develop a few weeks after exposure and share many features with other common skin infections, including Staphylococcus aureus. Lymphatic involvement and sporotrichoid spread may occur. Immunocompromised patients can experience deeper involvement into tendons. Patients with significant soft tissue pain should undergo computed tomography, or preferably magnetic resonance imaging, to determine the extent of disease.

For immunocompetent patients and those with limited disease, as in this case, spontaneous resolution can occur after a year or more. However, because of the potential risk of more severe disease, treatment is recommended. M marinum is resistant to multiple antibiotics and there are no standardized treatment guidelines. Minocycline 100 mg bid for 3 weeks to 3 months is 1 accepted regimen for limited disease; treatment should be continued for 3 to 4 weeks following clinical resolution.1 Patients with more widespread disease benefit from evaluation by Infectious Diseases. Patients exposed to atypical mycobacteria may have false positive QuantiFERON-TB Gold tests that are commonly performed prior to biologic therapies.2

This patient achieved complete resolution of his signs and symptoms after receiving minocycline 100 mg bid for 6 weeks. He continues to fish recreationally.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A biopsy was performed to exclude squamous cell carcinoma and an additional biopsy was sent for tissue culture for aerobic and acid-fast bacteria. The culture revealed a surprising diagnosis: cutaneous mycobacterium marinum.

Mycobacterium marinum is one of many nontuberculosis mycobacteria that may rarely cause infections in immunocompetent patients. M marinum is found worldwide in saltwater and freshwater. Infections may occur in individuals working in fisheries or fish markets, natural marine environments, or with aquariums. The infection may gain access through small, even unnoticed breaks in the skin. Papules, pustules, or abscesses caused by M marinum develop a few weeks after exposure and share many features with other common skin infections, including Staphylococcus aureus. Lymphatic involvement and sporotrichoid spread may occur. Immunocompromised patients can experience deeper involvement into tendons. Patients with significant soft tissue pain should undergo computed tomography, or preferably magnetic resonance imaging, to determine the extent of disease.

For immunocompetent patients and those with limited disease, as in this case, spontaneous resolution can occur after a year or more. However, because of the potential risk of more severe disease, treatment is recommended. M marinum is resistant to multiple antibiotics and there are no standardized treatment guidelines. Minocycline 100 mg bid for 3 weeks to 3 months is 1 accepted regimen for limited disease; treatment should be continued for 3 to 4 weeks following clinical resolution.1 Patients with more widespread disease benefit from evaluation by Infectious Diseases. Patients exposed to atypical mycobacteria may have false positive QuantiFERON-TB Gold tests that are commonly performed prior to biologic therapies.2

This patient achieved complete resolution of his signs and symptoms after receiving minocycline 100 mg bid for 6 weeks. He continues to fish recreationally.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Rallis E, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E. Treatment of Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2965-2978. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.17.2965

2. Gajurel K, Subramanian AK. False-positive QuantiFERON TB-Gold test due to Mycobacterium gordonae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;84:315-317. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.10.020

1. Rallis E, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E. Treatment of Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2965-2978. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.17.2965

2. Gajurel K, Subramanian AK. False-positive QuantiFERON TB-Gold test due to Mycobacterium gordonae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;84:315-317. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.10.020