User login

Labial growth

White-to-pink friable plaques occurring acutely in the vulva is concerning for one form of secondary syphilis that affects mucous membranes: condyloma lata.

Known as the great imitator for its variety of clinical presentations, syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Three to 10 days following contact with the spirochete, a painless ulcer or chancre forms and subsequently resolves—sometimes without notice.

Secondary syphilis develops from hematogenous spread of bacteria taking many forms—most commonly a widespread rash over the whole body of many (although sometimes faint) macules or papules up to about 1 cm in size and haphazardly spread out about every 1 cm. Palms and soles may be affected, even if faintly. Another, less common form of secondary syphilis includes the friable plaques (often in the anogenital area, as pictured) that are highly concentrated with bacteria. These occur 3 to 12 weeks after the appearance of a primary chancre and are variably symptomatic.

The differential diagnosis includes genital warts, vulvar carcinoma, and pemphigus vegetans. The relatively rapid, multifocal presentation helps to separate this disorder from vulvar carcinoma. A biopsy can distinguish the 2. However, diagnosis is better made with serology using nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Treponemal tests (assaying immunoglobulin [Ig]M and IgG to Treponema pallidum) are also an option and are very specific. Following this, an RPR titer can help guide treatment. Darkfield microscopy, which can reveal spirochetes directly, isn’t readily available but could be used to diagnose condyloma lata.

Patients who have been given a diagnosis of syphilis should be offered screening for other STIs, including HIV. Anyone who has had sexual contact with the patient within the previous 90 days should be notified, tested, and treated. Patients with primary or secondary syphilis should be treated with 2.4 million units of intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G in a single dose—regardless of whether they test positive for HIV. To exclude tertiary syphilis, a careful neurologic exam should take place at the time of diagnosis and again 6 and 12 months after treatment (sooner if follow-up may be uncertain). Consider treatment failure if RPR titers haven’t fallen fourfold in 12 months. In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a notice that COVID-19-vaccinated patients may have false-positive RPR titers performed from Bio-Rad Laboratories (BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR kit).1

In this case, the patient tested positive for treponemal antibodies and had an RPR titer of 1:128. She was treated with IM benzathine penicillin with lasting clearance.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infection Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Reviewed December 22, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm

White-to-pink friable plaques occurring acutely in the vulva is concerning for one form of secondary syphilis that affects mucous membranes: condyloma lata.

Known as the great imitator for its variety of clinical presentations, syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Three to 10 days following contact with the spirochete, a painless ulcer or chancre forms and subsequently resolves—sometimes without notice.

Secondary syphilis develops from hematogenous spread of bacteria taking many forms—most commonly a widespread rash over the whole body of many (although sometimes faint) macules or papules up to about 1 cm in size and haphazardly spread out about every 1 cm. Palms and soles may be affected, even if faintly. Another, less common form of secondary syphilis includes the friable plaques (often in the anogenital area, as pictured) that are highly concentrated with bacteria. These occur 3 to 12 weeks after the appearance of a primary chancre and are variably symptomatic.

The differential diagnosis includes genital warts, vulvar carcinoma, and pemphigus vegetans. The relatively rapid, multifocal presentation helps to separate this disorder from vulvar carcinoma. A biopsy can distinguish the 2. However, diagnosis is better made with serology using nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Treponemal tests (assaying immunoglobulin [Ig]M and IgG to Treponema pallidum) are also an option and are very specific. Following this, an RPR titer can help guide treatment. Darkfield microscopy, which can reveal spirochetes directly, isn’t readily available but could be used to diagnose condyloma lata.

Patients who have been given a diagnosis of syphilis should be offered screening for other STIs, including HIV. Anyone who has had sexual contact with the patient within the previous 90 days should be notified, tested, and treated. Patients with primary or secondary syphilis should be treated with 2.4 million units of intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G in a single dose—regardless of whether they test positive for HIV. To exclude tertiary syphilis, a careful neurologic exam should take place at the time of diagnosis and again 6 and 12 months after treatment (sooner if follow-up may be uncertain). Consider treatment failure if RPR titers haven’t fallen fourfold in 12 months. In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a notice that COVID-19-vaccinated patients may have false-positive RPR titers performed from Bio-Rad Laboratories (BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR kit).1

In this case, the patient tested positive for treponemal antibodies and had an RPR titer of 1:128. She was treated with IM benzathine penicillin with lasting clearance.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

White-to-pink friable plaques occurring acutely in the vulva is concerning for one form of secondary syphilis that affects mucous membranes: condyloma lata.

Known as the great imitator for its variety of clinical presentations, syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Three to 10 days following contact with the spirochete, a painless ulcer or chancre forms and subsequently resolves—sometimes without notice.

Secondary syphilis develops from hematogenous spread of bacteria taking many forms—most commonly a widespread rash over the whole body of many (although sometimes faint) macules or papules up to about 1 cm in size and haphazardly spread out about every 1 cm. Palms and soles may be affected, even if faintly. Another, less common form of secondary syphilis includes the friable plaques (often in the anogenital area, as pictured) that are highly concentrated with bacteria. These occur 3 to 12 weeks after the appearance of a primary chancre and are variably symptomatic.

The differential diagnosis includes genital warts, vulvar carcinoma, and pemphigus vegetans. The relatively rapid, multifocal presentation helps to separate this disorder from vulvar carcinoma. A biopsy can distinguish the 2. However, diagnosis is better made with serology using nontreponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Treponemal tests (assaying immunoglobulin [Ig]M and IgG to Treponema pallidum) are also an option and are very specific. Following this, an RPR titer can help guide treatment. Darkfield microscopy, which can reveal spirochetes directly, isn’t readily available but could be used to diagnose condyloma lata.

Patients who have been given a diagnosis of syphilis should be offered screening for other STIs, including HIV. Anyone who has had sexual contact with the patient within the previous 90 days should be notified, tested, and treated. Patients with primary or secondary syphilis should be treated with 2.4 million units of intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G in a single dose—regardless of whether they test positive for HIV. To exclude tertiary syphilis, a careful neurologic exam should take place at the time of diagnosis and again 6 and 12 months after treatment (sooner if follow-up may be uncertain). Consider treatment failure if RPR titers haven’t fallen fourfold in 12 months. In 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a notice that COVID-19-vaccinated patients may have false-positive RPR titers performed from Bio-Rad Laboratories (BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR kit).1

In this case, the patient tested positive for treponemal antibodies and had an RPR titer of 1:128. She was treated with IM benzathine penicillin with lasting clearance.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infection Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Reviewed December 22, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infection Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Reviewed December 22, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm

Extensive scarring alopecia and widespread rash

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

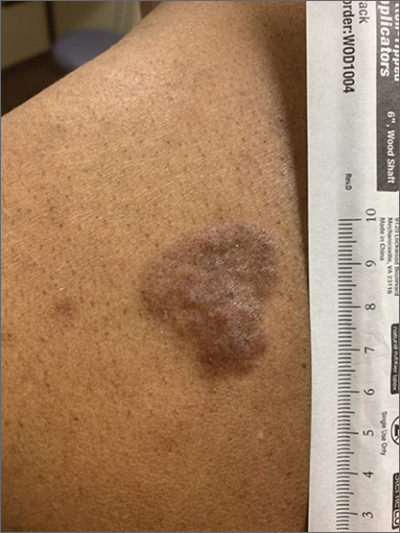

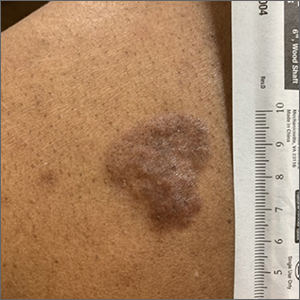

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

1. Petty AJ, Floyd L, Henderson C, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: progress and challenges. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00906-8

2. Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.021

3. Durosaro O, Davis MDP, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249-253. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.21

4. Merola JF. Overview of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. UpToDate. Updated September 19, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus

5. Biazar C, Sigges J, Patsinakidis N, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: first multicenter database analysis of 1002 patients from the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (EUSCLE). Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:444-454. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.08.019

6. O’Brien JC, Chong BF. not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

7. Kuhn A, Ruland V, Bonsmann G. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: update of therapeutic options part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e179-e193. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.018

8. Kindle SA, Wetter DA, Davis MDP, et al. Lenalidomide treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e431-e439. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13226

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

A 23-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and a history of poor adherence to recommended treatment presented with a widespread pruritic rash and diffuse hair loss. The rash had rapidly progressed following sun exposure during the summer. The patient cited her mental health status (anxiety, depression), socioeconomic factors, and challenges with prescription insurance coverage as reasons for nonadherence to treatment.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse scarring alopecia and abnormal pigmentation of the scalp (FIGURE 1A), as well as large, red-brown, scaly, atrophic plaques on the face, ears, extremities, back, and buttocks (FIGURES 1B and 1C).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Generalized chronic cutaneouslupus erythematosus

The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with generalized chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), which is 1 of 3 subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The other 2 are acute and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE and SCLE, respectively). CCLE is further divided into 3 distinct entities: discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), chilblain lupus erythematosus, and lupus erythematosus panniculitis.

Distinguishing between the different forms of cutaneous lupus can be challenging; diagnosis is based on differences in clinical features and duration of skin changes, as well as biopsy and lab results.1 The clinical features of our patient were most consistent with DLE, based on the scarring alopecia with scaly atrophic plaques, dyspigmentation, and exacerbation following sun exposure.

DLE is the most common form of CCLE and frequently manifests in a localized, photosensitive distribution involving the scalp, ears, and/or face.2 Less commonly, it can demonstrate a more generalized distribution involving the trunk and/or extremities (reported incidence of 1.04 per 100,000 people).3 Longstanding DLE lesions commonly exhibit scarring and dyspigmentation. DLE occurs in approximately 15% to 30% of SLE patients,4 whereas about 10% of patients with DLE will progress to SLE.3

Positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are found in 54% of patients with CCLE, compared to 74% and 81% of patients with SCLE and ACLE, respectively.5 Thus, a negative ANA should not rule out the possibility of CLE.

Comprehensive lab work and biopsy could expose a systemic origin

While our patient already had a diagnosis of SLE, many patients will present with no prior history of autoimmune connective tissue disease, and, in that case, the objective should be to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for systemic involvement. This includes a thorough review of systems; skin biopsy; complete blood count; liver function tests; urinalysis; and measurement of creatinine, inflammatory markers, ANA, extractable nuclear antigens, double-stranded DNA, complement levels (C3, C4, total), and antiphospholipid antibodies.6

Continue to: Biopsy

Biopsy features of DLE include vacuolar interface dermatitis, basement membrane zone thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasma cells, and increased mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence biopsy may show a continuous granular immunoglobulin (Ig) G/IgA/IgM and C3 band at the basement membrane zone.

Abnormal serologic tests may support the diagnosis of SLE based on American College of Rheumatology criteria and could suggest additional organ involvement or associated conditions, such as lupus nephritis or antiphospholipid syndrome (respectively). Currently, no clear consensus exists on monitoring patients with cutaneous lupus for systemic disease.

A gamut of skin-changing conditions should be considered

The differential diagnosis in this case includes SCLE, dermatitis, tinea corporis, cutaneous drug eruptions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

SCLE classically manifests with annular or psoriasiform lesions on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk (eg, the chest, neck, and upper extremities), while the central face and scalp are typically spared. Differentiating between generalized DLE and SCLE may be the most difficult, given similarities in the associated skin changes.

Dermatitis (atopic or contact) manifests as pruritic erythematous eczematous plaques, most commonly involving the flexural areas in atopic dermatitis and an exposure-dependent distribution pattern in contact dermatitis. The patient may have a history of atopy.

Continue to: Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis will manifest with annular scaly patches or plaques and may demonstrate erythematous papules around hair follicles in Majocchi granuloma. A positive potassium hydroxide exam demonstrating fungal hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Cutaneous drug eruptions can have various morphologies and timing of onset. Certain photosensitive drug reactions can be triggered or exacerbated with sun exposure. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain a thorough medication history, including any new medications that were started within the past 4 to 6 weeks, although onset can be delayed beyond this timeframe.

GVHD is a complication that more commonly follows allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, although it may be seen following solid-organ transplantation or transfusion of nonirradiated blood. Chronic GVHD has an onset ≥ 100 days after transplant and is divided into nonsclerotic (lichenoid, atopic dermatitis-like, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous) and sclerotic morphologies.

Successful Tx requires adherence but may not prevent flare-ups

First-line treatment options for severe and widespread skin manifestations of CLE include photoprotection, smoking cessation, topical corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and systemic corticosteroids. Second-line treatments include chloroquine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil; thalidomide or lenalidomide may be considered for patients with refractory disease.7,8

With successful treatment and photoprotection, patients may achieve significant skin clearing. Occasional flares, especially during warmer months, may occur if they are not diligent about photoprotection. Systemic treatments will also improve the patient’s systemic symptoms if the patient has concomitant SLE.

Our patient was advised to use topical steroids and to restart hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg/d (a regimen with which she had previously been nonadherent). The patient followed up with her family physician for assessment of her other medical issues. No new interventions for her mental health were initiated during this visit, as the severity of her depression was considered mild. She was referred to a case manager to navigate multiple medical appointments and prescription insurance coverage issues. The patient’s dose of mycophenolate mofetil was increased gradually to 3 g/d, and the patient experienced improvement in both her cutaneous lesions and systemic symptoms.

1. Petty AJ, Floyd L, Henderson C, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: progress and challenges. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00906-8

2. Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.021

3. Durosaro O, Davis MDP, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249-253. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.21

4. Merola JF. Overview of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. UpToDate. Updated September 19, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus

5. Biazar C, Sigges J, Patsinakidis N, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: first multicenter database analysis of 1002 patients from the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (EUSCLE). Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:444-454. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.08.019

6. O’Brien JC, Chong BF. not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

7. Kuhn A, Ruland V, Bonsmann G. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: update of therapeutic options part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e179-e193. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.018

8. Kindle SA, Wetter DA, Davis MDP, et al. Lenalidomide treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e431-e439. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13226

1. Petty AJ, Floyd L, Henderson C, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: progress and challenges. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00906-8

2. Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.021

3. Durosaro O, Davis MDP, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249-253. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.21

4. Merola JF. Overview of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. UpToDate. Updated September 19, 2021. Accessed February 17, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus

5. Biazar C, Sigges J, Patsinakidis N, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: first multicenter database analysis of 1002 patients from the European Society of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (EUSCLE). Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:444-454. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.08.019

6. O’Brien JC, Chong BF. not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

7. Kuhn A, Ruland V, Bonsmann G. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: update of therapeutic options part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e179-e193. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.018

8. Kindle SA, Wetter DA, Davis MDP, et al. Lenalidomide treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e431-e439. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13226

Innumerable pulmonary nodules

A 56-year-old woman with a history of a thyroid goiter following a partial thyroidectomy presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath, progressive weakness, and fatigue. She also reported a poor appetite and unintentional weight loss of approximately 40 lbs over the past 2 months but had not sought medical care. She denied having a cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, hematemesis, fevers, chills, or night sweats.

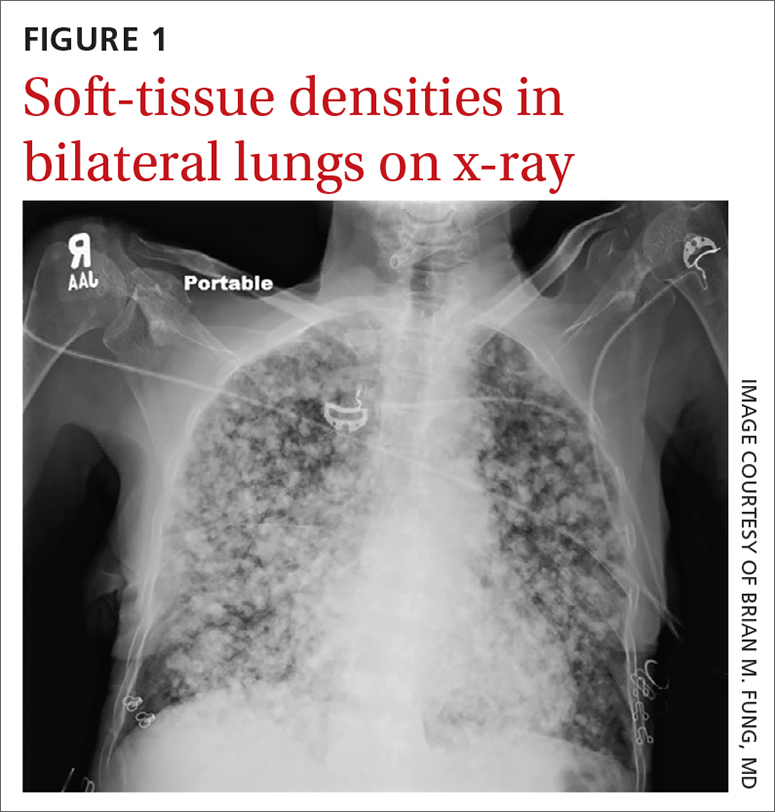

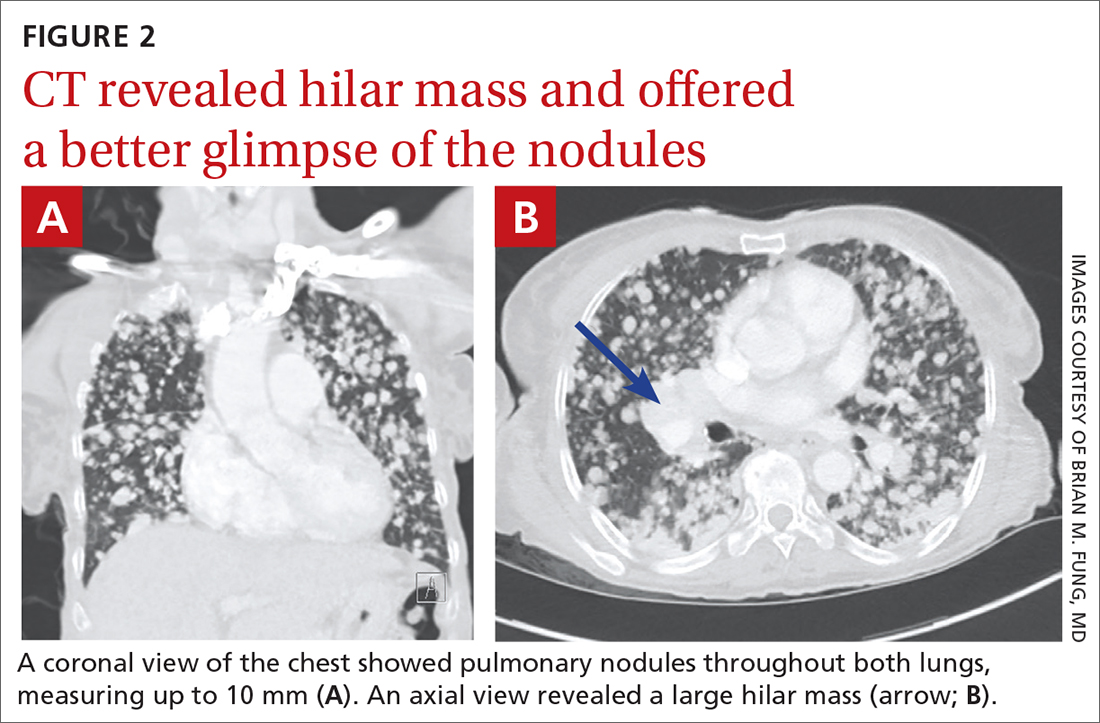

Physical examination revealed a cachectic woman with tachycardia and tachypnea, along with diffuse coarse rales throughout both lungs. The patient’s initial heart rate was 101 beats/min; respiratory rate, 25 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 74% on room air. The results of a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal limits. A chest radiograph was performed, showing innumerable subcentimeter- and pericentimeter-sized soft-tissue densities in both lungs (FIGURE 1). Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was subsequently obtained to better characterize the nodules (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The CT revealed innumerable noncalcified pulmonary nodules as well as multiple hilar masses suggestive of malignancy; however, infectious etiologies could not be ruled out.

As the patient was visiting from a tuberculosis-endemic area, she was empirically started on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RIPE) therapy for treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Subsequently, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and acid-fast bacillus sputum smear came back negative for M tuberculosis and RIPE therapy was stopped. Bacterial culture and fungal screens for Pneumocystis jirovecii, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, and Histoplasma capsulatum were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma

A biopsy of one of the lung nodules was performed and showed strong positive staining for thyroglobulin and thyroid transcription factor-1, establishing a diagnosis of metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma. Further imaging revealed additional metastases to the brain, liver, adrenal glands, and spine.

Follicular thyroid carcinoma is the second most common histologic type of thyroid cancer, comprising 10% to 15% of thyroid cancer cases.1 Distant metastases are not uncommon in this histologic type; about 11% of patients have distant metastases at presentation.2 Compared with papillary thyroid cancer, which spreads via the lymphatics, the follicular type can metastasize via vascular invasion, thus leading to its “aggressiveness” and frequent occurrence of metastasis outside the neck (most commonly to the lung).1 For this reason, an early diagnosis is important.3 In this case, the patient revealed that she hadn’t sought medical care at the onset of her symptoms due to financial limitations and limited access to medical providers; this likely contributed to the patient’s diagnosis at a late stage of disease.

Infectious and septic diseases are part of the differential Dx

The differential diagnosis for diffuse pulmonary nodules includes various infections, silicosis, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, septic pulmonary emboli, and pulmonary sarcoidosis. All of these diagnoses can cause constitutional, as well as pulmonary, symptoms.

Infections, such as pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, or other cavitating infections, can be ruled out with specific testing for the organism of concern and/or culture.

Silicosis and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis generally cause lesions in the upper lobes and require a significant occupational exposure to silica or coal, respectively.

Continue to: Septic pulmonary emboli

Septic pulmonary emboli are usually seen in the context of sepsis, and there are positive blood cultures at the time of imaging.

Pulmonary sarcoidosis typically manifests with hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and is often accompanied by other organ involvement.

There are options for treatment if diagnosis is made early

Thyroidectomy, radioiodine treatment, and thyroid-stimulating hormone suppressive therapy are the most commonly used therapies for treatment of follicular thyroid carcinoma.4 If follicular thyroid carcinoma is caught early (with only local involvement), 5-year relative survival rates are near 100%.5 However, outcomes are generally poor in patients who are of older age and those who have macronodular lung metastases or multiple bone metastases.6

Our patient was started on levothyroxine. Radioiodine and targeted drug therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor were attempted, but the patient was unable to tolerate them due to her poor functional status. She was thus transitioned to hospice care.

1. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Grogan RH, Ward MH, et al. Follicular thyroid cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1980-2009. Thyroid. 2013;23:1015-1021. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0356

2. Shaha AR, Shah JP, Loree TR. Differentiated thyroid cancer presenting initially with distant metastasis. Am J Surg. 1997;174:474-476. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00158-x

3. Lim IIP, Hochman T, Blumberg SN, et al. Disparities in the initial presentation of differentiated thyroid cancer in a large public hospital and adjoining university teaching hospital. Thyroid. 2012;22:269-274. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0385

4. Grani G, Lamartina L, Durante C, et al. Follicular thyroid cancer and Hürthle cell carcinoma: challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:500-514. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30325-X

5. Thyroid cancer survival rates, by type and stage. American Cancer Society. Updated January 25, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2022. www.cancer.org/cancer/thyroid-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

6. Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, et al. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2892-2899. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2838

A 56-year-old woman with a history of a thyroid goiter following a partial thyroidectomy presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath, progressive weakness, and fatigue. She also reported a poor appetite and unintentional weight loss of approximately 40 lbs over the past 2 months but had not sought medical care. She denied having a cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, hematemesis, fevers, chills, or night sweats.

Physical examination revealed a cachectic woman with tachycardia and tachypnea, along with diffuse coarse rales throughout both lungs. The patient’s initial heart rate was 101 beats/min; respiratory rate, 25 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 74% on room air. The results of a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal limits. A chest radiograph was performed, showing innumerable subcentimeter- and pericentimeter-sized soft-tissue densities in both lungs (FIGURE 1). Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was subsequently obtained to better characterize the nodules (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The CT revealed innumerable noncalcified pulmonary nodules as well as multiple hilar masses suggestive of malignancy; however, infectious etiologies could not be ruled out.

As the patient was visiting from a tuberculosis-endemic area, she was empirically started on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RIPE) therapy for treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Subsequently, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and acid-fast bacillus sputum smear came back negative for M tuberculosis and RIPE therapy was stopped. Bacterial culture and fungal screens for Pneumocystis jirovecii, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, and Histoplasma capsulatum were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma

A biopsy of one of the lung nodules was performed and showed strong positive staining for thyroglobulin and thyroid transcription factor-1, establishing a diagnosis of metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma. Further imaging revealed additional metastases to the brain, liver, adrenal glands, and spine.

Follicular thyroid carcinoma is the second most common histologic type of thyroid cancer, comprising 10% to 15% of thyroid cancer cases.1 Distant metastases are not uncommon in this histologic type; about 11% of patients have distant metastases at presentation.2 Compared with papillary thyroid cancer, which spreads via the lymphatics, the follicular type can metastasize via vascular invasion, thus leading to its “aggressiveness” and frequent occurrence of metastasis outside the neck (most commonly to the lung).1 For this reason, an early diagnosis is important.3 In this case, the patient revealed that she hadn’t sought medical care at the onset of her symptoms due to financial limitations and limited access to medical providers; this likely contributed to the patient’s diagnosis at a late stage of disease.

Infectious and septic diseases are part of the differential Dx

The differential diagnosis for diffuse pulmonary nodules includes various infections, silicosis, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, septic pulmonary emboli, and pulmonary sarcoidosis. All of these diagnoses can cause constitutional, as well as pulmonary, symptoms.

Infections, such as pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, or other cavitating infections, can be ruled out with specific testing for the organism of concern and/or culture.

Silicosis and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis generally cause lesions in the upper lobes and require a significant occupational exposure to silica or coal, respectively.

Continue to: Septic pulmonary emboli

Septic pulmonary emboli are usually seen in the context of sepsis, and there are positive blood cultures at the time of imaging.

Pulmonary sarcoidosis typically manifests with hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and is often accompanied by other organ involvement.

There are options for treatment if diagnosis is made early

Thyroidectomy, radioiodine treatment, and thyroid-stimulating hormone suppressive therapy are the most commonly used therapies for treatment of follicular thyroid carcinoma.4 If follicular thyroid carcinoma is caught early (with only local involvement), 5-year relative survival rates are near 100%.5 However, outcomes are generally poor in patients who are of older age and those who have macronodular lung metastases or multiple bone metastases.6

Our patient was started on levothyroxine. Radioiodine and targeted drug therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor were attempted, but the patient was unable to tolerate them due to her poor functional status. She was thus transitioned to hospice care.

A 56-year-old woman with a history of a thyroid goiter following a partial thyroidectomy presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath, progressive weakness, and fatigue. She also reported a poor appetite and unintentional weight loss of approximately 40 lbs over the past 2 months but had not sought medical care. She denied having a cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, hematemesis, fevers, chills, or night sweats.

Physical examination revealed a cachectic woman with tachycardia and tachypnea, along with diffuse coarse rales throughout both lungs. The patient’s initial heart rate was 101 beats/min; respiratory rate, 25 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 74% on room air. The results of a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal limits. A chest radiograph was performed, showing innumerable subcentimeter- and pericentimeter-sized soft-tissue densities in both lungs (FIGURE 1). Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was subsequently obtained to better characterize the nodules (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The CT revealed innumerable noncalcified pulmonary nodules as well as multiple hilar masses suggestive of malignancy; however, infectious etiologies could not be ruled out.

As the patient was visiting from a tuberculosis-endemic area, she was empirically started on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RIPE) therapy for treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Subsequently, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and acid-fast bacillus sputum smear came back negative for M tuberculosis and RIPE therapy was stopped. Bacterial culture and fungal screens for Pneumocystis jirovecii, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, and Histoplasma capsulatum were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma

A biopsy of one of the lung nodules was performed and showed strong positive staining for thyroglobulin and thyroid transcription factor-1, establishing a diagnosis of metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma. Further imaging revealed additional metastases to the brain, liver, adrenal glands, and spine.

Follicular thyroid carcinoma is the second most common histologic type of thyroid cancer, comprising 10% to 15% of thyroid cancer cases.1 Distant metastases are not uncommon in this histologic type; about 11% of patients have distant metastases at presentation.2 Compared with papillary thyroid cancer, which spreads via the lymphatics, the follicular type can metastasize via vascular invasion, thus leading to its “aggressiveness” and frequent occurrence of metastasis outside the neck (most commonly to the lung).1 For this reason, an early diagnosis is important.3 In this case, the patient revealed that she hadn’t sought medical care at the onset of her symptoms due to financial limitations and limited access to medical providers; this likely contributed to the patient’s diagnosis at a late stage of disease.

Infectious and septic diseases are part of the differential Dx

The differential diagnosis for diffuse pulmonary nodules includes various infections, silicosis, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, septic pulmonary emboli, and pulmonary sarcoidosis. All of these diagnoses can cause constitutional, as well as pulmonary, symptoms.

Infections, such as pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, or other cavitating infections, can be ruled out with specific testing for the organism of concern and/or culture.

Silicosis and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis generally cause lesions in the upper lobes and require a significant occupational exposure to silica or coal, respectively.

Continue to: Septic pulmonary emboli

Septic pulmonary emboli are usually seen in the context of sepsis, and there are positive blood cultures at the time of imaging.

Pulmonary sarcoidosis typically manifests with hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and is often accompanied by other organ involvement.

There are options for treatment if diagnosis is made early

Thyroidectomy, radioiodine treatment, and thyroid-stimulating hormone suppressive therapy are the most commonly used therapies for treatment of follicular thyroid carcinoma.4 If follicular thyroid carcinoma is caught early (with only local involvement), 5-year relative survival rates are near 100%.5 However, outcomes are generally poor in patients who are of older age and those who have macronodular lung metastases or multiple bone metastases.6

Our patient was started on levothyroxine. Radioiodine and targeted drug therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor were attempted, but the patient was unable to tolerate them due to her poor functional status. She was thus transitioned to hospice care.

1. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Grogan RH, Ward MH, et al. Follicular thyroid cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1980-2009. Thyroid. 2013;23:1015-1021. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0356

2. Shaha AR, Shah JP, Loree TR. Differentiated thyroid cancer presenting initially with distant metastasis. Am J Surg. 1997;174:474-476. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00158-x

3. Lim IIP, Hochman T, Blumberg SN, et al. Disparities in the initial presentation of differentiated thyroid cancer in a large public hospital and adjoining university teaching hospital. Thyroid. 2012;22:269-274. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0385

4. Grani G, Lamartina L, Durante C, et al. Follicular thyroid cancer and Hürthle cell carcinoma: challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:500-514. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30325-X

5. Thyroid cancer survival rates, by type and stage. American Cancer Society. Updated January 25, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2022. www.cancer.org/cancer/thyroid-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

6. Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, et al. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2892-2899. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2838

1. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Grogan RH, Ward MH, et al. Follicular thyroid cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1980-2009. Thyroid. 2013;23:1015-1021. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0356

2. Shaha AR, Shah JP, Loree TR. Differentiated thyroid cancer presenting initially with distant metastasis. Am J Surg. 1997;174:474-476. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00158-x

3. Lim IIP, Hochman T, Blumberg SN, et al. Disparities in the initial presentation of differentiated thyroid cancer in a large public hospital and adjoining university teaching hospital. Thyroid. 2012;22:269-274. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0385

4. Grani G, Lamartina L, Durante C, et al. Follicular thyroid cancer and Hürthle cell carcinoma: challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:500-514. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30325-X

5. Thyroid cancer survival rates, by type and stage. American Cancer Society. Updated January 25, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2022. www.cancer.org/cancer/thyroid-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

6. Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, et al. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2892-2899. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2838

Unusual tongue markings

Well-demarcated, map-like tongue markings are consistent with migratory glossitis, also called geographic tongue, and can be recognized by its distinct clinical appearance. If performed, a biopsy would show psoriasiform mucositis.

Migratory glossitis is an uncommon condition found mostly in adults and occasionally in children. The prevalence may be as high as 2.5% globally and it may occur in conjunction with psoriasis, sharing some histologic features.1 (On close inspection, this patient was noted to have plaques on his elbows that were consistent with psoriasis.) While an immunogenic cause is suspected, the exact etiology is unknown.

Patients may develop these clinical findings quickly and just as quickly they may resolve. Discomfort and taste disturbances rarely occur. Hot, spicy, or acidic foods may be a contributing trigger. Tobacco-use appears to be protective. The presence of ulceration should prompt evaluation for a different diagnosis, such as erosive lichen planus, leukoplakia, candidiasis, or Behçet syndrome.

With minimal symptoms, treatment is rarely needed. Patients with any discomfort can be treated with topical lidocaine 2% swish and spit mouthwash, topical tacrolimus, or topical steroids.

The patient in this case was reassured that the diagnosis was not concerning and he was observed without active treatment. His psoriasis was treated with topical clobetasol ointment 0.05%. He has continued to have intermittent flares that he has yet to associate with any specific dietary causes.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Shareef S, Ettefagh L. Geographic tongue. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 3, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554466/

Well-demarcated, map-like tongue markings are consistent with migratory glossitis, also called geographic tongue, and can be recognized by its distinct clinical appearance. If performed, a biopsy would show psoriasiform mucositis.

Migratory glossitis is an uncommon condition found mostly in adults and occasionally in children. The prevalence may be as high as 2.5% globally and it may occur in conjunction with psoriasis, sharing some histologic features.1 (On close inspection, this patient was noted to have plaques on his elbows that were consistent with psoriasis.) While an immunogenic cause is suspected, the exact etiology is unknown.

Patients may develop these clinical findings quickly and just as quickly they may resolve. Discomfort and taste disturbances rarely occur. Hot, spicy, or acidic foods may be a contributing trigger. Tobacco-use appears to be protective. The presence of ulceration should prompt evaluation for a different diagnosis, such as erosive lichen planus, leukoplakia, candidiasis, or Behçet syndrome.

With minimal symptoms, treatment is rarely needed. Patients with any discomfort can be treated with topical lidocaine 2% swish and spit mouthwash, topical tacrolimus, or topical steroids.

The patient in this case was reassured that the diagnosis was not concerning and he was observed without active treatment. His psoriasis was treated with topical clobetasol ointment 0.05%. He has continued to have intermittent flares that he has yet to associate with any specific dietary causes.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Well-demarcated, map-like tongue markings are consistent with migratory glossitis, also called geographic tongue, and can be recognized by its distinct clinical appearance. If performed, a biopsy would show psoriasiform mucositis.

Migratory glossitis is an uncommon condition found mostly in adults and occasionally in children. The prevalence may be as high as 2.5% globally and it may occur in conjunction with psoriasis, sharing some histologic features.1 (On close inspection, this patient was noted to have plaques on his elbows that were consistent with psoriasis.) While an immunogenic cause is suspected, the exact etiology is unknown.

Patients may develop these clinical findings quickly and just as quickly they may resolve. Discomfort and taste disturbances rarely occur. Hot, spicy, or acidic foods may be a contributing trigger. Tobacco-use appears to be protective. The presence of ulceration should prompt evaluation for a different diagnosis, such as erosive lichen planus, leukoplakia, candidiasis, or Behçet syndrome.

With minimal symptoms, treatment is rarely needed. Patients with any discomfort can be treated with topical lidocaine 2% swish and spit mouthwash, topical tacrolimus, or topical steroids.

The patient in this case was reassured that the diagnosis was not concerning and he was observed without active treatment. His psoriasis was treated with topical clobetasol ointment 0.05%. He has continued to have intermittent flares that he has yet to associate with any specific dietary causes.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Shareef S, Ettefagh L. Geographic tongue. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 3, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554466/

1. Shareef S, Ettefagh L. Geographic tongue. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 3, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554466/

Toenail ridges

Transverse ridges that grow out with the nails are called Beau lines, also known as Beau’s ridges. This contrasts with Mees lines which are transverse white bands that grow out with the toenails, are nonpalpable, and are attributed to arsenic poisoning.

Beau lines are caused by a disruption in nail growth that can result from trauma, hypotension, or systemic or severe illness; they have also been reported in cases of COVID-19.1 Beau lines can occur on a single nail if the trauma or injury is isolated to 1 digit. If there was a systemic illness or stress, the lines can affect all 20 nails. The time of the inciting event can be approximated by how far the lines are from the cuticle. While there is some variability, it usually takes 12 to 18 months to grow an entirely new toenail. If the Beau lines have grown halfway out, then the stressor likely occurred 6 to 9 months earlier.

In this image, some asymmetry is visible between the right and left great toenails and there are some subtle distal changes, raising the possibility that there was more than 1 injury to this patient’s system (or prolonged difficulty). The patient said that to his knowledge, he had not been infected with COVID-19. However, hair and nail changes may be the only finding in some individuals who have been infected with COVID-19.1

This patient was counseled regarding the nature of this disorder and that without knowing what illness or injury caused the change, it was a benign finding. He was advised that it did not appear to be onychomycosis and did not require any medications or antifungal therapy. The patient was told to follow up if any changes developed.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

- Deng J, Ngo T, Zhu TH, Halverstam C. Telogen effluvium, Beau lines, and acral peeling associated with COVID-19 infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:138-140. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.05.026

Transverse ridges that grow out with the nails are called Beau lines, also known as Beau’s ridges. This contrasts with Mees lines which are transverse white bands that grow out with the toenails, are nonpalpable, and are attributed to arsenic poisoning.

Beau lines are caused by a disruption in nail growth that can result from trauma, hypotension, or systemic or severe illness; they have also been reported in cases of COVID-19.1 Beau lines can occur on a single nail if the trauma or injury is isolated to 1 digit. If there was a systemic illness or stress, the lines can affect all 20 nails. The time of the inciting event can be approximated by how far the lines are from the cuticle. While there is some variability, it usually takes 12 to 18 months to grow an entirely new toenail. If the Beau lines have grown halfway out, then the stressor likely occurred 6 to 9 months earlier.

In this image, some asymmetry is visible between the right and left great toenails and there are some subtle distal changes, raising the possibility that there was more than 1 injury to this patient’s system (or prolonged difficulty). The patient said that to his knowledge, he had not been infected with COVID-19. However, hair and nail changes may be the only finding in some individuals who have been infected with COVID-19.1

This patient was counseled regarding the nature of this disorder and that without knowing what illness or injury caused the change, it was a benign finding. He was advised that it did not appear to be onychomycosis and did not require any medications or antifungal therapy. The patient was told to follow up if any changes developed.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Transverse ridges that grow out with the nails are called Beau lines, also known as Beau’s ridges. This contrasts with Mees lines which are transverse white bands that grow out with the toenails, are nonpalpable, and are attributed to arsenic poisoning.

Beau lines are caused by a disruption in nail growth that can result from trauma, hypotension, or systemic or severe illness; they have also been reported in cases of COVID-19.1 Beau lines can occur on a single nail if the trauma or injury is isolated to 1 digit. If there was a systemic illness or stress, the lines can affect all 20 nails. The time of the inciting event can be approximated by how far the lines are from the cuticle. While there is some variability, it usually takes 12 to 18 months to grow an entirely new toenail. If the Beau lines have grown halfway out, then the stressor likely occurred 6 to 9 months earlier.

In this image, some asymmetry is visible between the right and left great toenails and there are some subtle distal changes, raising the possibility that there was more than 1 injury to this patient’s system (or prolonged difficulty). The patient said that to his knowledge, he had not been infected with COVID-19. However, hair and nail changes may be the only finding in some individuals who have been infected with COVID-19.1

This patient was counseled regarding the nature of this disorder and that without knowing what illness or injury caused the change, it was a benign finding. He was advised that it did not appear to be onychomycosis and did not require any medications or antifungal therapy. The patient was told to follow up if any changes developed.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

- Deng J, Ngo T, Zhu TH, Halverstam C. Telogen effluvium, Beau lines, and acral peeling associated with COVID-19 infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:138-140. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.05.026

- Deng J, Ngo T, Zhu TH, Halverstam C. Telogen effluvium, Beau lines, and acral peeling associated with COVID-19 infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:138-140. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.05.026

Right arm rash

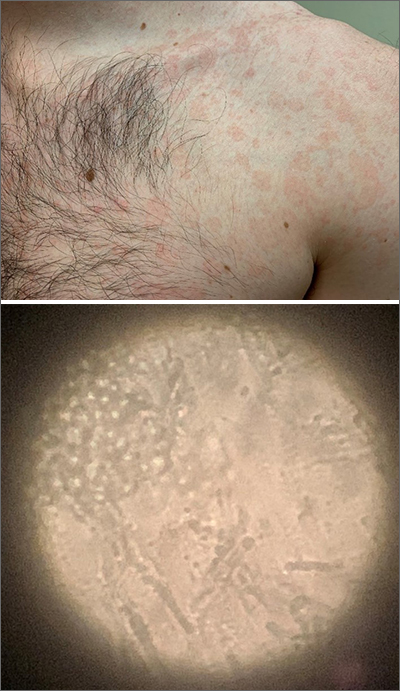

Common skin reactions to treatment with topical 5-FU for actinic keratosis include erythema, ulceration, and burning. In this case, however, the skin disruption opened the door to secondary impetigo.

Secondary skin infections are a known risk of treatment with topical 5-FU. The agent inhibits thymidylate synthetase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis and repair of DNA. The inhibition of this enzyme can lead to skin disruption with erosion, desquamation, and the risk of superimposed skin infections, as was seen with this patient.1

Impetigo is a common skin infection affecting the superficial layers of the epidermis and is most commonly caused by gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.2 Secondary impetigo, also known as impetiginization, is an infection of previously disrupted skin due to eczema, trauma, insect bites, and other conditions. This contrasts with primary impetigo, which results from a direct bacterial invasion of intact healthy skin. While impetigo predominantly affects children between the ages of 2 and 5 years, people of any age can be affected.2 Impetigo characteristically manifests with painful erosions, classically covered by honey-colored crusts. Thin-walled vesicles often appear and subsequently rupture.

Treatment options for impetigo include both topical and systemic antibiotics. Topical therapy is preferred for patients with limited skin involvement, while systemic therapy is indicated for patients with numerous lesions. Mupirocin and retapamulin are first-line topical treatments. Systemic antibiotic therapy should provide coverage for both S. aureus and streptococcal infections; cephalexin and dicloxacillin are preferred. Doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin can be used if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected.3

This patient was advised to try warm soaks (to reduce the crusting) and to follow that with the application of white petrolatum bid. The patient was also prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally bid for 10 days. At the 1-month follow-up, there was some residual erythema, but the impetigo and crusting had resolved. The actinic keratoses had resolved, as well.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Tess Pei Lemon, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

1. Chughtai K, Gupta R, Upadhaya S, et al. Topical 5-Fluorouracil associated skin reaction. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2017;2017(8):omx043. doi:10.1093/omcr/omx043

2. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:229-235.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296

Common skin reactions to treatment with topical 5-FU for actinic keratosis include erythema, ulceration, and burning. In this case, however, the skin disruption opened the door to secondary impetigo.

Secondary skin infections are a known risk of treatment with topical 5-FU. The agent inhibits thymidylate synthetase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis and repair of DNA. The inhibition of this enzyme can lead to skin disruption with erosion, desquamation, and the risk of superimposed skin infections, as was seen with this patient.1

Impetigo is a common skin infection affecting the superficial layers of the epidermis and is most commonly caused by gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.2 Secondary impetigo, also known as impetiginization, is an infection of previously disrupted skin due to eczema, trauma, insect bites, and other conditions. This contrasts with primary impetigo, which results from a direct bacterial invasion of intact healthy skin. While impetigo predominantly affects children between the ages of 2 and 5 years, people of any age can be affected.2 Impetigo characteristically manifests with painful erosions, classically covered by honey-colored crusts. Thin-walled vesicles often appear and subsequently rupture.

Treatment options for impetigo include both topical and systemic antibiotics. Topical therapy is preferred for patients with limited skin involvement, while systemic therapy is indicated for patients with numerous lesions. Mupirocin and retapamulin are first-line topical treatments. Systemic antibiotic therapy should provide coverage for both S. aureus and streptococcal infections; cephalexin and dicloxacillin are preferred. Doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin can be used if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected.3

This patient was advised to try warm soaks (to reduce the crusting) and to follow that with the application of white petrolatum bid. The patient was also prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally bid for 10 days. At the 1-month follow-up, there was some residual erythema, but the impetigo and crusting had resolved. The actinic keratoses had resolved, as well.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Tess Pei Lemon, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Common skin reactions to treatment with topical 5-FU for actinic keratosis include erythema, ulceration, and burning. In this case, however, the skin disruption opened the door to secondary impetigo.

Secondary skin infections are a known risk of treatment with topical 5-FU. The agent inhibits thymidylate synthetase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis and repair of DNA. The inhibition of this enzyme can lead to skin disruption with erosion, desquamation, and the risk of superimposed skin infections, as was seen with this patient.1

Impetigo is a common skin infection affecting the superficial layers of the epidermis and is most commonly caused by gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.2 Secondary impetigo, also known as impetiginization, is an infection of previously disrupted skin due to eczema, trauma, insect bites, and other conditions. This contrasts with primary impetigo, which results from a direct bacterial invasion of intact healthy skin. While impetigo predominantly affects children between the ages of 2 and 5 years, people of any age can be affected.2 Impetigo characteristically manifests with painful erosions, classically covered by honey-colored crusts. Thin-walled vesicles often appear and subsequently rupture.

Treatment options for impetigo include both topical and systemic antibiotics. Topical therapy is preferred for patients with limited skin involvement, while systemic therapy is indicated for patients with numerous lesions. Mupirocin and retapamulin are first-line topical treatments. Systemic antibiotic therapy should provide coverage for both S. aureus and streptococcal infections; cephalexin and dicloxacillin are preferred. Doxycycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin can be used if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected.3

This patient was advised to try warm soaks (to reduce the crusting) and to follow that with the application of white petrolatum bid. The patient was also prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally bid for 10 days. At the 1-month follow-up, there was some residual erythema, but the impetigo and crusting had resolved. The actinic keratoses had resolved, as well.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Tess Pei Lemon, BA, University of New Mexico School of Medicine and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

1. Chughtai K, Gupta R, Upadhaya S, et al. Topical 5-Fluorouracil associated skin reaction. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2017;2017(8):omx043. doi:10.1093/omcr/omx043

2. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:229-235.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296

1. Chughtai K, Gupta R, Upadhaya S, et al. Topical 5-Fluorouracil associated skin reaction. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2017;2017(8):omx043. doi:10.1093/omcr/omx043

2. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:229-235.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296

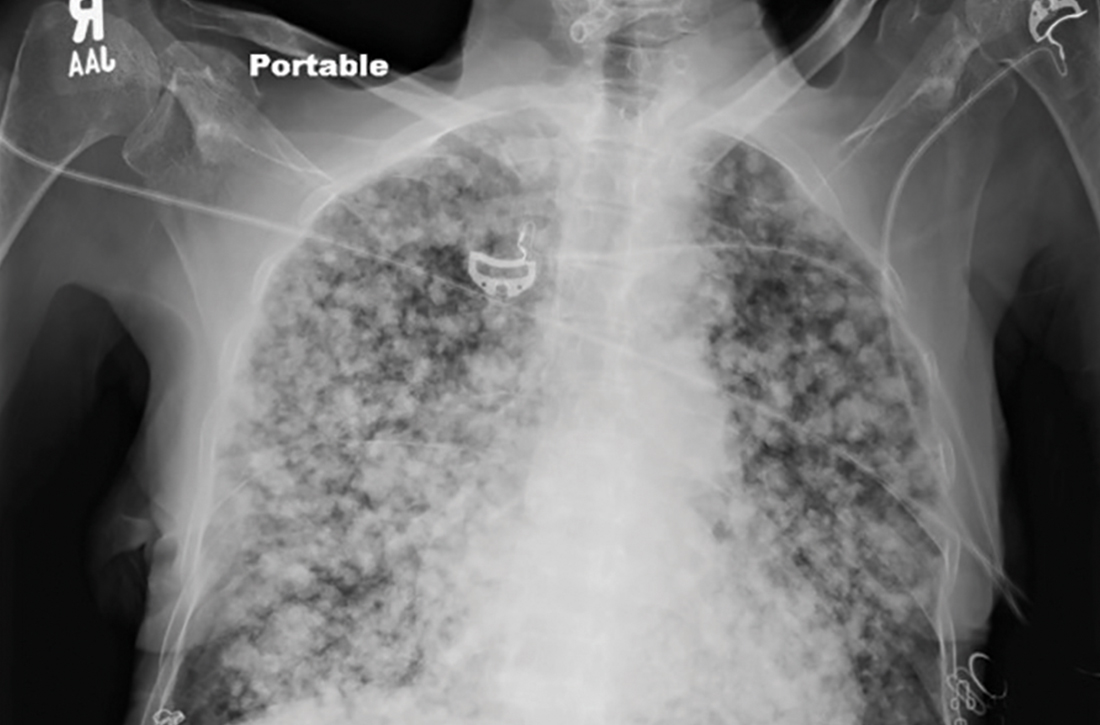

Chronic truncal rash

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea versicolor (TV), also known as pityriasis versicolor, after a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep test on a skin scraping confirmed the spaghetti and meatballs pattern of Malassezia Furfur (see image above). Note that in most cases, a KOH prep is not required for the diagnosis. Experienced clinicians will usually make the diagnosis based on the appearance of hyper- or hypopigmented macules or patches with fine scale on the trunk of adults. KOH prep is useful if the diagnosis is uncertain.

TV is a common fungal infection that’s seen more frequently in tropical climates and occurs equally in men and women.1M. Furfur thrives on the lipids in the skin of sebum-rich areas, which explains its truncal distribution and rare occurrence in children (who have much lower sebum production).

Usually, topical antifungal medications are considered first-line treatment, but since large areas of skin are involved, adequate amounts need to be used. One of the most common and inexpensive treatments is to apply selenium sulfide shampoo (Selsun Blue) undiluted to the entire trunk, then allow to dry and remain in place overnight before showering. A repeat application should be done 1 week later. Topical terbinafine cream applied bid for 2 weeks is another option, as is oral itraconazole in a single 400 mg dose.

This patient declined the selenium sulfide topical treatment and requested systemic therapy, so he was prescribed itraconazole 400 mg orally as a single dose. He was advised that it might take a few weeks to clear up, and to use the selenium sulfide application if the itraconazole was not effective. Follow-up was not planned due to the high success rate of these therapies.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Saunte DML, Gaitanis G, Hay RJ. Malassezia-associated skin diseases, the use of diagnostics and treatment. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:112. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00112

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea versicolor (TV), also known as pityriasis versicolor, after a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep test on a skin scraping confirmed the spaghetti and meatballs pattern of Malassezia Furfur (see image above). Note that in most cases, a KOH prep is not required for the diagnosis. Experienced clinicians will usually make the diagnosis based on the appearance of hyper- or hypopigmented macules or patches with fine scale on the trunk of adults. KOH prep is useful if the diagnosis is uncertain.

TV is a common fungal infection that’s seen more frequently in tropical climates and occurs equally in men and women.1M. Furfur thrives on the lipids in the skin of sebum-rich areas, which explains its truncal distribution and rare occurrence in children (who have much lower sebum production).

Usually, topical antifungal medications are considered first-line treatment, but since large areas of skin are involved, adequate amounts need to be used. One of the most common and inexpensive treatments is to apply selenium sulfide shampoo (Selsun Blue) undiluted to the entire trunk, then allow to dry and remain in place overnight before showering. A repeat application should be done 1 week later. Topical terbinafine cream applied bid for 2 weeks is another option, as is oral itraconazole in a single 400 mg dose.

This patient declined the selenium sulfide topical treatment and requested systemic therapy, so he was prescribed itraconazole 400 mg orally as a single dose. He was advised that it might take a few weeks to clear up, and to use the selenium sulfide application if the itraconazole was not effective. Follow-up was not planned due to the high success rate of these therapies.

Image courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea versicolor (TV), also known as pityriasis versicolor, after a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep test on a skin scraping confirmed the spaghetti and meatballs pattern of Malassezia Furfur (see image above). Note that in most cases, a KOH prep is not required for the diagnosis. Experienced clinicians will usually make the diagnosis based on the appearance of hyper- or hypopigmented macules or patches with fine scale on the trunk of adults. KOH prep is useful if the diagnosis is uncertain.

TV is a common fungal infection that’s seen more frequently in tropical climates and occurs equally in men and women.1M. Furfur thrives on the lipids in the skin of sebum-rich areas, which explains its truncal distribution and rare occurrence in children (who have much lower sebum production).