User login

A teen presents with a severe, tender rash on the extremities

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

She started taking lithium for depression and anxiety 3 weeks prior to her developing the rash. She denies taking any other medications, supplements, or recreational drugs.

She denied any prior history of photosensitivity, no history of mouth ulcers, joint pain, muscle weakness, hair loss, or any other symptoms.

Besides her brother, there are no other affected family members, and no history of immune bullous disorders or other skin conditions.

On physical exam, the girl appears in a lot of pain and is uncomfortable. The skin is red and hot, and there are tense bullae on the neck, arms, and legs. There are no ocular or mucosal lesions.

Congenital Defect of the Toenail

The Diagnosis: Onychodystrophy Secondary to Polydactyly

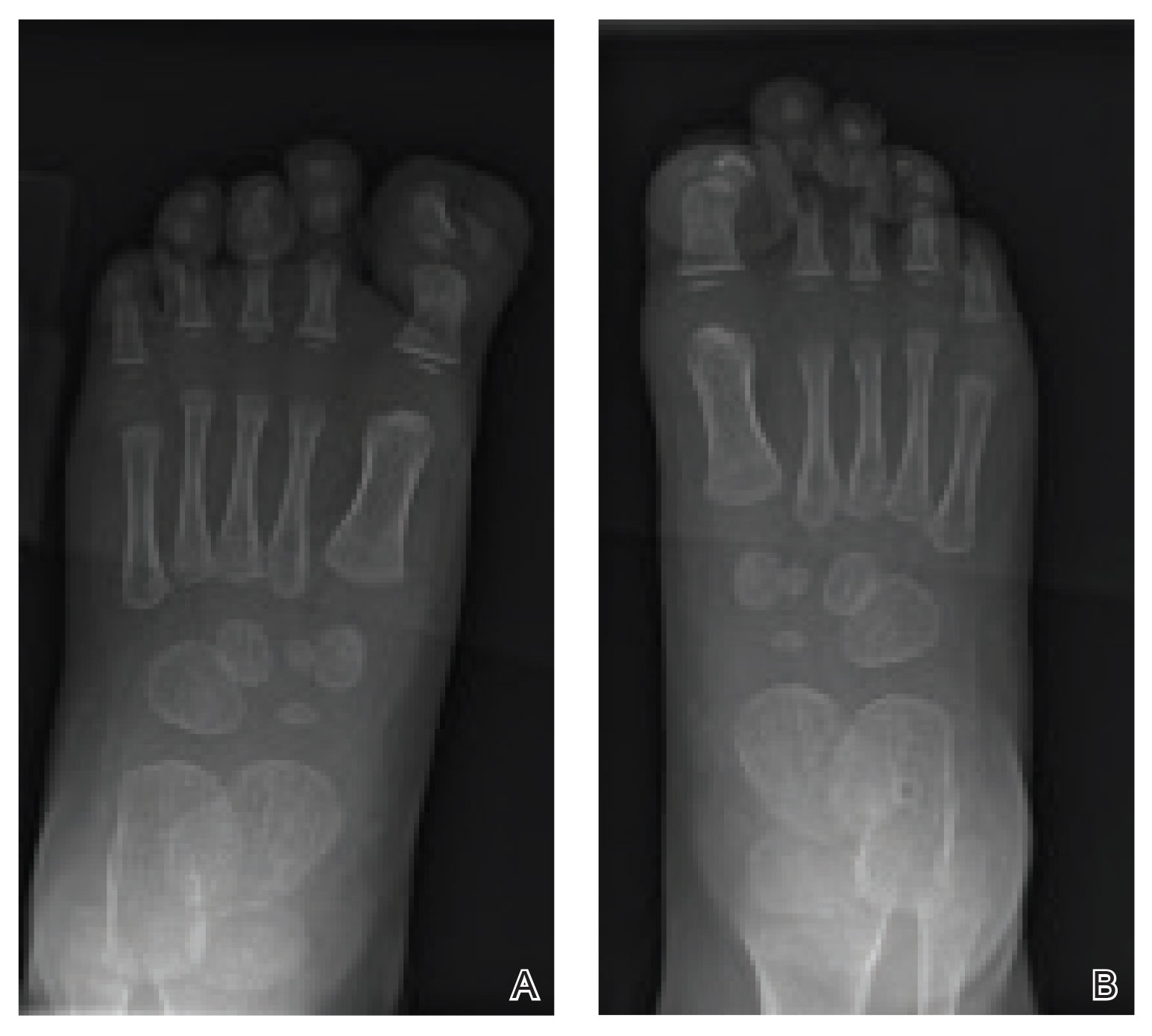

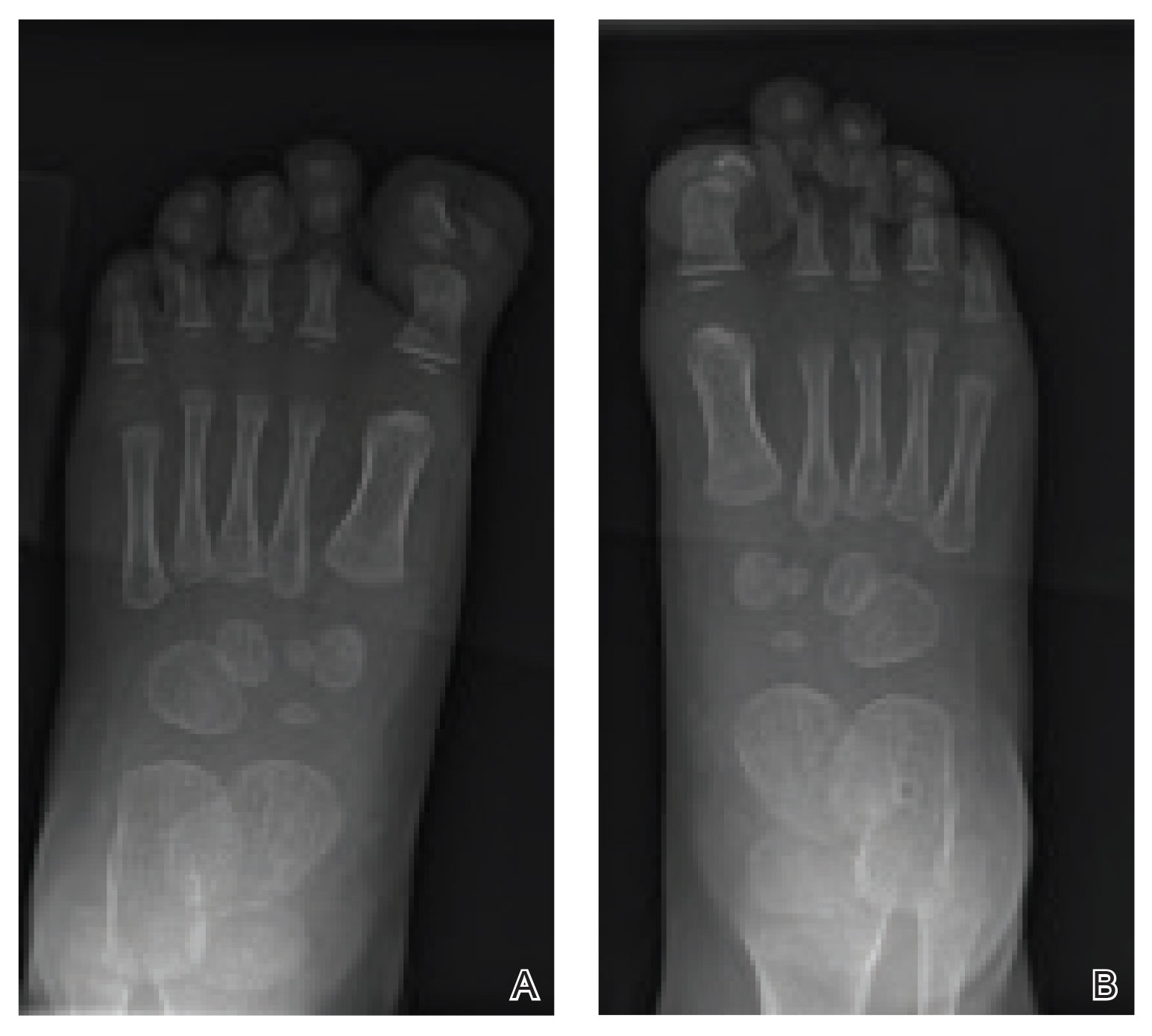

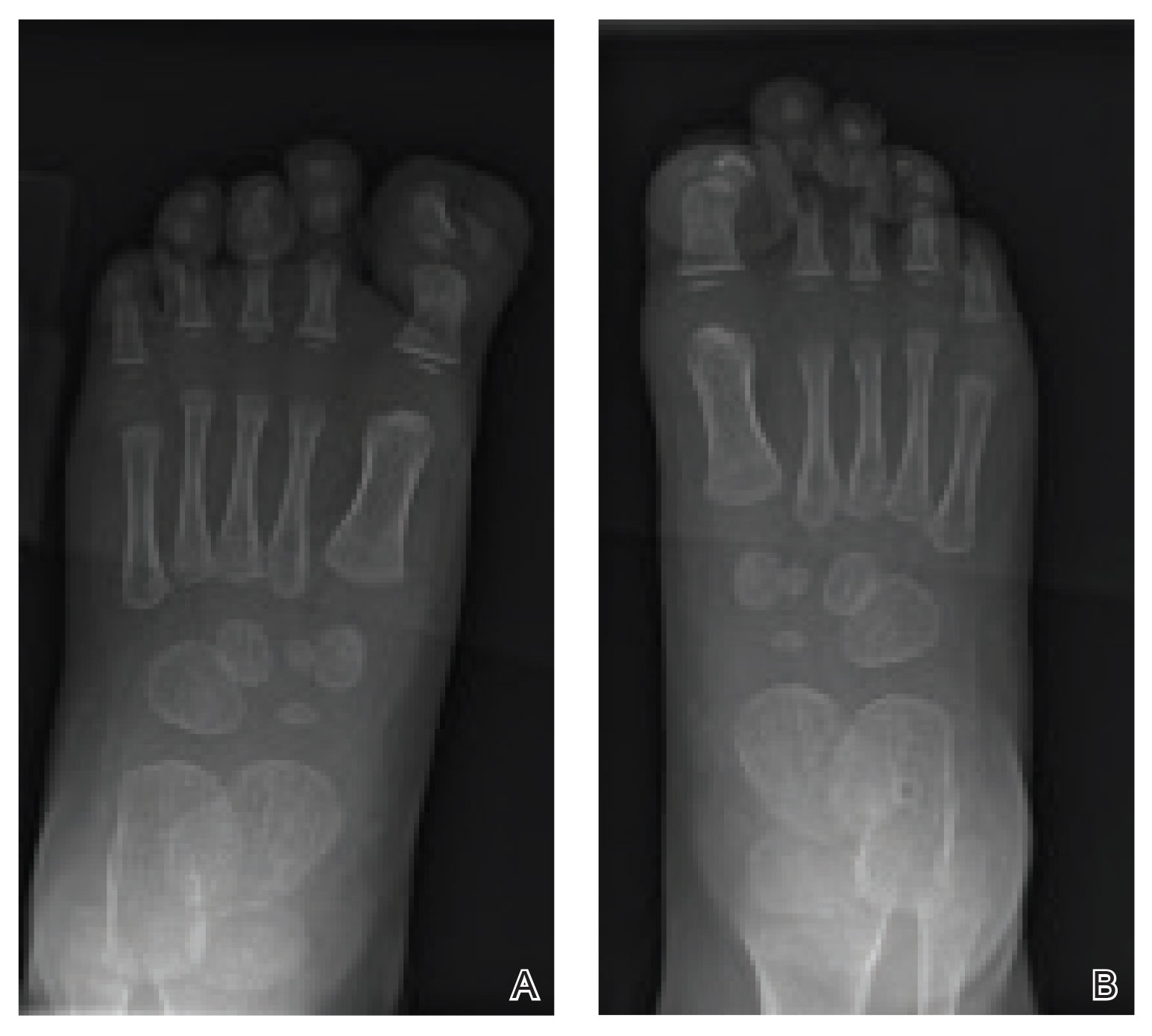

Radiographs of the feet demonstrated an accessory distal phalanx of the left great toe with a similar smaller accessory distal phalanx on the right great toe (Figure). The patient was referred to orthopedic surgery, and surgical intervention was recommended for only the left great toe given recurrent skin inflammation and nail complications. An excision of the left great toe polydactyly was performed. The patient healed well without complications.

Many clinically heterogeneous phenotypes exist for polydactyly and syndactyly, which both are common entities with incidences of 1 in 700 to 1000 births and 1 in 2000 to 3000 births, respectively.1 Both polydactyly and syndactyly can be an isolated variant in newborns or present with multiple concurrent malformations as part of a genetic syndrome, with more than 300 syndromic anomalies described. The genetic basis of these conditions is equally diverse, with homeobox genes, hedgehog pathways, fibroblast growth factors, and boneand cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins implicated in their development.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient included congenital malalignment of the great toenails, nail-patella syndrome, onychodystrophy secondary to polydactyly, and congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold. Given the strong family history, polydactyly was suspected.

Congenital malalignment of the great toenails results in lateral deviation of the nail plates.2 It is an underdiagnosed condition with different etiologies hypothesized, such as genetic factors with possible autosomal-dominant transmission and extrinsic factors.3 One proposed mechanism of pathogenesis is desynchronization during growth of the nail and distal phalanx of the hallux, leading to larger nail plates that grow laterally.4 Typical features associated with this disease are nail discoloration, nail plate thickening, and transversal grooves or ridges, none of which were seen in our patient.2

Children with nail-patella syndrome have dysplastic nails and associated bony abnormalities, such as absent patellae.5 This syndrome results from an autosomaldominant mutation in the LIM homeobox transcription factor 1-beta gene, LMX1B, which is responsible for dorsal-ventral patterning of the limb, as well as patterning of the nails, patellae and long bones, and even the kidney tubule.6 As such, patients with nail-patella syndrome have associated renal abnormalities. The findings in our patient were limited to the feet, making an underlying syndrome unlikely to be the cause.

First described in 1968 by Meadow,7 fetal hydantoin syndrome is a well-documented sequela in women taking phenytoin throughout pregnancy. Multiple malformations are possible, including cardiac defects, cleft lip/palate, digit and nail hypoplasia, abnormal facial features, mental disability, and growth abnormalities.8 The teratogenicity behind phenytoin results from reactive oxygen species that alter embryonic DNA, proteins, and lipids.9 The mother of this child was not on any seizure prophylaxis, eliminating it from the differential.

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold is a defect of the soft tissue of the hallux leading to hypertrophy of the nail fold, commonly presenting with inflammation and pain10 possibly due to dyssynchronous growth between the soft tissue and nail plate.11 With this defect, a lip covering the nail plate is common, which was not seen in our patient.

As demonstrated in our patient, family history can help guide the diagnosis. Seven of 9 nonsyndromic forms of syndactyly are inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and range from mild presentations, as in our patient, to more severe deformations with underlying bone fusion and functional impairment.12 Polydactyly also often is expressed in an autosomal-dominant pattern, with up to 30% of patients having a positive family history. Polydactyly traditionally is classified by the location of the supernumerary digit as preaxial (radial), central, or postaxial (ulnar), and many further morphologic variations exist within these groups. Overall, preaxial polydactyly is relatively rare and represents 15% of polydactylies, with central and postaxial comprising the other 6% and 79%, respectively.13 Delineation of the underlying anatomy may reveal ray duplications (digit and corresponding metacarpal or metatarsal bone), metatarsal variants, and duplicated phalanges that may be hypoplastic or deformed. Patients may report difficulty finding comfortable footwear, cosmetic concerns, and nail-related complications. Although not always required, surgical intervention may provide definitive treatment but can leave residual deformities in the surrounding altered anatomy; thus, orthopedic or plastic surgery consultations are critical in appropriately counseling patients.

- Ahmed H, Akbari H, Emanmi A, et al. Genetic overview of syndactyly and polydactyly. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1549.

- Catalfo P, Musumeci ML, Lacarrubba F, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails: a review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:230-235.

- Kus S, Tahmaz E, Gurunluoglu R, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails in dizygotic twins. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:434-435.

- Chaniotakis I, Bonitsis N, Stergiopoulou C, et al. Dizygotic twins with congenital malalignment of the great toenails: reappraisal of the pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:711-715.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, et al, Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:47-50.

- Meadow SR. Anticonvulsant drugs and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1968;2:1296.

- Scheinfeld N. Phenytoin in cutaneous medicine: its uses, mechanisms and side effects. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:6.

- Winn LM, Wells PG. Phenytoin-initiated DNA oxidation in murine embryo culture, and embryo protection by the antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase: evidence for reactive oxygen species-mediated DNA oxidation in the molecular mechanism of phenytoin teratogenicity. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:112-120.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Martinet C, Pascal M, Civatte J, et al. Lateral nail-pad of the big toe in infants. apropos of 2 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:731-732.

- Malik S. Syndactyly: phenotypes, genetics and current classification. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:817-824.

- Belthur MV, Linton JL, Barnes DA. The spectrum of preaxial polydactyly of the foot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:435-447.

The Diagnosis: Onychodystrophy Secondary to Polydactyly

Radiographs of the feet demonstrated an accessory distal phalanx of the left great toe with a similar smaller accessory distal phalanx on the right great toe (Figure). The patient was referred to orthopedic surgery, and surgical intervention was recommended for only the left great toe given recurrent skin inflammation and nail complications. An excision of the left great toe polydactyly was performed. The patient healed well without complications.

Many clinically heterogeneous phenotypes exist for polydactyly and syndactyly, which both are common entities with incidences of 1 in 700 to 1000 births and 1 in 2000 to 3000 births, respectively.1 Both polydactyly and syndactyly can be an isolated variant in newborns or present with multiple concurrent malformations as part of a genetic syndrome, with more than 300 syndromic anomalies described. The genetic basis of these conditions is equally diverse, with homeobox genes, hedgehog pathways, fibroblast growth factors, and boneand cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins implicated in their development.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient included congenital malalignment of the great toenails, nail-patella syndrome, onychodystrophy secondary to polydactyly, and congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold. Given the strong family history, polydactyly was suspected.

Congenital malalignment of the great toenails results in lateral deviation of the nail plates.2 It is an underdiagnosed condition with different etiologies hypothesized, such as genetic factors with possible autosomal-dominant transmission and extrinsic factors.3 One proposed mechanism of pathogenesis is desynchronization during growth of the nail and distal phalanx of the hallux, leading to larger nail plates that grow laterally.4 Typical features associated with this disease are nail discoloration, nail plate thickening, and transversal grooves or ridges, none of which were seen in our patient.2

Children with nail-patella syndrome have dysplastic nails and associated bony abnormalities, such as absent patellae.5 This syndrome results from an autosomaldominant mutation in the LIM homeobox transcription factor 1-beta gene, LMX1B, which is responsible for dorsal-ventral patterning of the limb, as well as patterning of the nails, patellae and long bones, and even the kidney tubule.6 As such, patients with nail-patella syndrome have associated renal abnormalities. The findings in our patient were limited to the feet, making an underlying syndrome unlikely to be the cause.

First described in 1968 by Meadow,7 fetal hydantoin syndrome is a well-documented sequela in women taking phenytoin throughout pregnancy. Multiple malformations are possible, including cardiac defects, cleft lip/palate, digit and nail hypoplasia, abnormal facial features, mental disability, and growth abnormalities.8 The teratogenicity behind phenytoin results from reactive oxygen species that alter embryonic DNA, proteins, and lipids.9 The mother of this child was not on any seizure prophylaxis, eliminating it from the differential.

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold is a defect of the soft tissue of the hallux leading to hypertrophy of the nail fold, commonly presenting with inflammation and pain10 possibly due to dyssynchronous growth between the soft tissue and nail plate.11 With this defect, a lip covering the nail plate is common, which was not seen in our patient.

As demonstrated in our patient, family history can help guide the diagnosis. Seven of 9 nonsyndromic forms of syndactyly are inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and range from mild presentations, as in our patient, to more severe deformations with underlying bone fusion and functional impairment.12 Polydactyly also often is expressed in an autosomal-dominant pattern, with up to 30% of patients having a positive family history. Polydactyly traditionally is classified by the location of the supernumerary digit as preaxial (radial), central, or postaxial (ulnar), and many further morphologic variations exist within these groups. Overall, preaxial polydactyly is relatively rare and represents 15% of polydactylies, with central and postaxial comprising the other 6% and 79%, respectively.13 Delineation of the underlying anatomy may reveal ray duplications (digit and corresponding metacarpal or metatarsal bone), metatarsal variants, and duplicated phalanges that may be hypoplastic or deformed. Patients may report difficulty finding comfortable footwear, cosmetic concerns, and nail-related complications. Although not always required, surgical intervention may provide definitive treatment but can leave residual deformities in the surrounding altered anatomy; thus, orthopedic or plastic surgery consultations are critical in appropriately counseling patients.

The Diagnosis: Onychodystrophy Secondary to Polydactyly

Radiographs of the feet demonstrated an accessory distal phalanx of the left great toe with a similar smaller accessory distal phalanx on the right great toe (Figure). The patient was referred to orthopedic surgery, and surgical intervention was recommended for only the left great toe given recurrent skin inflammation and nail complications. An excision of the left great toe polydactyly was performed. The patient healed well without complications.

Many clinically heterogeneous phenotypes exist for polydactyly and syndactyly, which both are common entities with incidences of 1 in 700 to 1000 births and 1 in 2000 to 3000 births, respectively.1 Both polydactyly and syndactyly can be an isolated variant in newborns or present with multiple concurrent malformations as part of a genetic syndrome, with more than 300 syndromic anomalies described. The genetic basis of these conditions is equally diverse, with homeobox genes, hedgehog pathways, fibroblast growth factors, and boneand cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins implicated in their development.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient included congenital malalignment of the great toenails, nail-patella syndrome, onychodystrophy secondary to polydactyly, and congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold. Given the strong family history, polydactyly was suspected.

Congenital malalignment of the great toenails results in lateral deviation of the nail plates.2 It is an underdiagnosed condition with different etiologies hypothesized, such as genetic factors with possible autosomal-dominant transmission and extrinsic factors.3 One proposed mechanism of pathogenesis is desynchronization during growth of the nail and distal phalanx of the hallux, leading to larger nail plates that grow laterally.4 Typical features associated with this disease are nail discoloration, nail plate thickening, and transversal grooves or ridges, none of which were seen in our patient.2

Children with nail-patella syndrome have dysplastic nails and associated bony abnormalities, such as absent patellae.5 This syndrome results from an autosomaldominant mutation in the LIM homeobox transcription factor 1-beta gene, LMX1B, which is responsible for dorsal-ventral patterning of the limb, as well as patterning of the nails, patellae and long bones, and even the kidney tubule.6 As such, patients with nail-patella syndrome have associated renal abnormalities. The findings in our patient were limited to the feet, making an underlying syndrome unlikely to be the cause.

First described in 1968 by Meadow,7 fetal hydantoin syndrome is a well-documented sequela in women taking phenytoin throughout pregnancy. Multiple malformations are possible, including cardiac defects, cleft lip/palate, digit and nail hypoplasia, abnormal facial features, mental disability, and growth abnormalities.8 The teratogenicity behind phenytoin results from reactive oxygen species that alter embryonic DNA, proteins, and lipids.9 The mother of this child was not on any seizure prophylaxis, eliminating it from the differential.

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold is a defect of the soft tissue of the hallux leading to hypertrophy of the nail fold, commonly presenting with inflammation and pain10 possibly due to dyssynchronous growth between the soft tissue and nail plate.11 With this defect, a lip covering the nail plate is common, which was not seen in our patient.

As demonstrated in our patient, family history can help guide the diagnosis. Seven of 9 nonsyndromic forms of syndactyly are inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and range from mild presentations, as in our patient, to more severe deformations with underlying bone fusion and functional impairment.12 Polydactyly also often is expressed in an autosomal-dominant pattern, with up to 30% of patients having a positive family history. Polydactyly traditionally is classified by the location of the supernumerary digit as preaxial (radial), central, or postaxial (ulnar), and many further morphologic variations exist within these groups. Overall, preaxial polydactyly is relatively rare and represents 15% of polydactylies, with central and postaxial comprising the other 6% and 79%, respectively.13 Delineation of the underlying anatomy may reveal ray duplications (digit and corresponding metacarpal or metatarsal bone), metatarsal variants, and duplicated phalanges that may be hypoplastic or deformed. Patients may report difficulty finding comfortable footwear, cosmetic concerns, and nail-related complications. Although not always required, surgical intervention may provide definitive treatment but can leave residual deformities in the surrounding altered anatomy; thus, orthopedic or plastic surgery consultations are critical in appropriately counseling patients.

- Ahmed H, Akbari H, Emanmi A, et al. Genetic overview of syndactyly and polydactyly. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1549.

- Catalfo P, Musumeci ML, Lacarrubba F, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails: a review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:230-235.

- Kus S, Tahmaz E, Gurunluoglu R, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails in dizygotic twins. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:434-435.

- Chaniotakis I, Bonitsis N, Stergiopoulou C, et al. Dizygotic twins with congenital malalignment of the great toenails: reappraisal of the pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:711-715.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, et al, Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:47-50.

- Meadow SR. Anticonvulsant drugs and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1968;2:1296.

- Scheinfeld N. Phenytoin in cutaneous medicine: its uses, mechanisms and side effects. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:6.

- Winn LM, Wells PG. Phenytoin-initiated DNA oxidation in murine embryo culture, and embryo protection by the antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase: evidence for reactive oxygen species-mediated DNA oxidation in the molecular mechanism of phenytoin teratogenicity. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:112-120.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Martinet C, Pascal M, Civatte J, et al. Lateral nail-pad of the big toe in infants. apropos of 2 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:731-732.

- Malik S. Syndactyly: phenotypes, genetics and current classification. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:817-824.

- Belthur MV, Linton JL, Barnes DA. The spectrum of preaxial polydactyly of the foot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:435-447.

- Ahmed H, Akbari H, Emanmi A, et al. Genetic overview of syndactyly and polydactyly. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1549.

- Catalfo P, Musumeci ML, Lacarrubba F, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails: a review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:230-235.

- Kus S, Tahmaz E, Gurunluoglu R, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails in dizygotic twins. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:434-435.

- Chaniotakis I, Bonitsis N, Stergiopoulou C, et al. Dizygotic twins with congenital malalignment of the great toenails: reappraisal of the pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:711-715.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, et al, Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:47-50.

- Meadow SR. Anticonvulsant drugs and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1968;2:1296.

- Scheinfeld N. Phenytoin in cutaneous medicine: its uses, mechanisms and side effects. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:6.

- Winn LM, Wells PG. Phenytoin-initiated DNA oxidation in murine embryo culture, and embryo protection by the antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase: evidence for reactive oxygen species-mediated DNA oxidation in the molecular mechanism of phenytoin teratogenicity. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:112-120.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Martinet C, Pascal M, Civatte J, et al. Lateral nail-pad of the big toe in infants. apropos of 2 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:731-732.

- Malik S. Syndactyly: phenotypes, genetics and current classification. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:817-824.

- Belthur MV, Linton JL, Barnes DA. The spectrum of preaxial polydactyly of the foot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:435-447.

An 18-month-old girl presented for evaluation of nail dystrophy. The patient’s parents stated that the left great toenail had been dystrophic since birth, leading to skin irritation and “snagging” of the toenail on socks and footwear. Additional history revealed that the patient also had webbed toes, and there was a paternal family history of polydactyly and syndactyly. Physical examination revealed webbing of the second and third toes to the distal interphalangeal joints on both feet, marked nail plate dystrophy on the left big toe, and an irregularly shaped nail plate on the right big toe. The patient had no similar findings on the hands.

A teen girl presents with a pinkish-red bump on her right leg

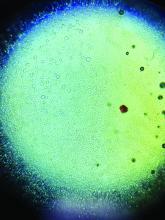

This atypical lesion might warrant a biopsy. However, upon closer examination, you can appreciate a small papule with a whitish center, at the inferior margin of the tumor (6 o’clock), and another flat-topped papule with a white center several centimeters inferior-lateral to the lesion, both consistent with molluscum lesions. Therefore, the tumor is consistent with a giant molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a cutaneous viral infection caused by the poxvirus, which commonly affects children. It can spread easily by direct physical contact, fomites, and autoinoculation.1 It usually presents with skin-colored or pink pearly dome-shaped papules with central umbilication that can occur anywhere on the face or body. The skin lesions can be asymptomatic or pruritic. When the size of the molluscum is 0.5 cm or more in diameter, it is considered a giant molluscum. Atypical size and appearance may be seen in patients with altered or impaired immunity such as those with HIV.2,3 Giant molluscum has been reported in immunocompetent patients as well.4,5

The diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum usually is made clinically. Our patient had typically appearing molluscum lesions approximate to the larger lesion of concern. She was overall healthy without any history of impaired immunity so no further work-up was pursued. However, a biopsy of the skin lesion may be considered if the diagnosis is unclear.

What’s the treatment plan?

Treatment may not be necessary for molluscum contagiosum because it is often self-limited in immunocompetent children, although it can take many months to years to resolve. Treatment may be considered to reduce autoinoculation or risk of transmission because of close contact to others, to alleviate discomfort, including itching, to reduce cosmetic concerns and to prevent secondary infection.6

The most common treatments for molluscum contagiosum are cantharidin or cryotherapy. Other treatment available include topical retinoids, immunomodulators such as cimetidine, or antivirals such as cidofovir.1 Lesions with or without treatment may exhibit the BOTE (beginning of the end) sign, which is an apparent worsening associated with the body’s immune response to the molluscum virus and generally indicates imminent resolution.

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for giant molluscum contagiosum includes epidermal inclusion cyst, skin tag, pilomatrixoma, and amelanotic melanoma.

Epidermal inclusion cyst typically presents as a firm, mobile nodule under the skin with central punctum, which can enlarge and become inflamed. It can be painful, especially when infected. Definitive treatment is surgical excision because it rarely resolves spontaneously.

Skin tags, also known as acrochordons, are benign skin-colored papules most often found in the skin folds. People with obesity and type 2 diabetes are at higher risk for skin tags. Skin tags may be treated with cryotherapy, surgical excision, or ligation.

Pilomatrixoma is a benign skin tumor derived from hair matrix cells. It is usually a nontender, firm, skin-colored or red-purple subcutaneous nodule that may have calcifications. Treatment is surgical excision.

Amelanotic melanoma is a melanoma with little or no pigment and can present as a skin- or red-colored nodule. While these are quite uncommon, recognition that many pediatric melanomas present as amelanotic lesions makes it important to consider this in the differential diagnosis of growing papules and nodules.7 Treatment and prognosis is similar to that of pigmented melanoma, but as it is often clinically challenging to diagnose because of atypical features, it may be detected in more advanced stages.

Our patient underwent cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen to the nodule given the large size of the lesion, with resolution without recurrence.

Dr. Lee is a pediatric dermatology research fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Lee nor Dr. Eichenfield had any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2017. doi: 10.2174/1872213X11666170518114456.

2. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2013 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2013.06.002.

3. Trop Doct. 2015 Apr. doi: 10.1177/0049475514568133.

4. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013 Jun;63(6):778-9.

5. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0603a15.

6 Molluscum Contagiosum, in “Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases,” 31st ed. (Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018, pp. 565-66).

7. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.953.

This atypical lesion might warrant a biopsy. However, upon closer examination, you can appreciate a small papule with a whitish center, at the inferior margin of the tumor (6 o’clock), and another flat-topped papule with a white center several centimeters inferior-lateral to the lesion, both consistent with molluscum lesions. Therefore, the tumor is consistent with a giant molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a cutaneous viral infection caused by the poxvirus, which commonly affects children. It can spread easily by direct physical contact, fomites, and autoinoculation.1 It usually presents with skin-colored or pink pearly dome-shaped papules with central umbilication that can occur anywhere on the face or body. The skin lesions can be asymptomatic or pruritic. When the size of the molluscum is 0.5 cm or more in diameter, it is considered a giant molluscum. Atypical size and appearance may be seen in patients with altered or impaired immunity such as those with HIV.2,3 Giant molluscum has been reported in immunocompetent patients as well.4,5

The diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum usually is made clinically. Our patient had typically appearing molluscum lesions approximate to the larger lesion of concern. She was overall healthy without any history of impaired immunity so no further work-up was pursued. However, a biopsy of the skin lesion may be considered if the diagnosis is unclear.

What’s the treatment plan?

Treatment may not be necessary for molluscum contagiosum because it is often self-limited in immunocompetent children, although it can take many months to years to resolve. Treatment may be considered to reduce autoinoculation or risk of transmission because of close contact to others, to alleviate discomfort, including itching, to reduce cosmetic concerns and to prevent secondary infection.6

The most common treatments for molluscum contagiosum are cantharidin or cryotherapy. Other treatment available include topical retinoids, immunomodulators such as cimetidine, or antivirals such as cidofovir.1 Lesions with or without treatment may exhibit the BOTE (beginning of the end) sign, which is an apparent worsening associated with the body’s immune response to the molluscum virus and generally indicates imminent resolution.

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for giant molluscum contagiosum includes epidermal inclusion cyst, skin tag, pilomatrixoma, and amelanotic melanoma.

Epidermal inclusion cyst typically presents as a firm, mobile nodule under the skin with central punctum, which can enlarge and become inflamed. It can be painful, especially when infected. Definitive treatment is surgical excision because it rarely resolves spontaneously.

Skin tags, also known as acrochordons, are benign skin-colored papules most often found in the skin folds. People with obesity and type 2 diabetes are at higher risk for skin tags. Skin tags may be treated with cryotherapy, surgical excision, or ligation.

Pilomatrixoma is a benign skin tumor derived from hair matrix cells. It is usually a nontender, firm, skin-colored or red-purple subcutaneous nodule that may have calcifications. Treatment is surgical excision.

Amelanotic melanoma is a melanoma with little or no pigment and can present as a skin- or red-colored nodule. While these are quite uncommon, recognition that many pediatric melanomas present as amelanotic lesions makes it important to consider this in the differential diagnosis of growing papules and nodules.7 Treatment and prognosis is similar to that of pigmented melanoma, but as it is often clinically challenging to diagnose because of atypical features, it may be detected in more advanced stages.

Our patient underwent cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen to the nodule given the large size of the lesion, with resolution without recurrence.

Dr. Lee is a pediatric dermatology research fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Lee nor Dr. Eichenfield had any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2017. doi: 10.2174/1872213X11666170518114456.

2. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2013 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2013.06.002.

3. Trop Doct. 2015 Apr. doi: 10.1177/0049475514568133.

4. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013 Jun;63(6):778-9.

5. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0603a15.

6 Molluscum Contagiosum, in “Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases,” 31st ed. (Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018, pp. 565-66).

7. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.953.

This atypical lesion might warrant a biopsy. However, upon closer examination, you can appreciate a small papule with a whitish center, at the inferior margin of the tumor (6 o’clock), and another flat-topped papule with a white center several centimeters inferior-lateral to the lesion, both consistent with molluscum lesions. Therefore, the tumor is consistent with a giant molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a cutaneous viral infection caused by the poxvirus, which commonly affects children. It can spread easily by direct physical contact, fomites, and autoinoculation.1 It usually presents with skin-colored or pink pearly dome-shaped papules with central umbilication that can occur anywhere on the face or body. The skin lesions can be asymptomatic or pruritic. When the size of the molluscum is 0.5 cm or more in diameter, it is considered a giant molluscum. Atypical size and appearance may be seen in patients with altered or impaired immunity such as those with HIV.2,3 Giant molluscum has been reported in immunocompetent patients as well.4,5

The diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum usually is made clinically. Our patient had typically appearing molluscum lesions approximate to the larger lesion of concern. She was overall healthy without any history of impaired immunity so no further work-up was pursued. However, a biopsy of the skin lesion may be considered if the diagnosis is unclear.

What’s the treatment plan?

Treatment may not be necessary for molluscum contagiosum because it is often self-limited in immunocompetent children, although it can take many months to years to resolve. Treatment may be considered to reduce autoinoculation or risk of transmission because of close contact to others, to alleviate discomfort, including itching, to reduce cosmetic concerns and to prevent secondary infection.6

The most common treatments for molluscum contagiosum are cantharidin or cryotherapy. Other treatment available include topical retinoids, immunomodulators such as cimetidine, or antivirals such as cidofovir.1 Lesions with or without treatment may exhibit the BOTE (beginning of the end) sign, which is an apparent worsening associated with the body’s immune response to the molluscum virus and generally indicates imminent resolution.

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for giant molluscum contagiosum includes epidermal inclusion cyst, skin tag, pilomatrixoma, and amelanotic melanoma.

Epidermal inclusion cyst typically presents as a firm, mobile nodule under the skin with central punctum, which can enlarge and become inflamed. It can be painful, especially when infected. Definitive treatment is surgical excision because it rarely resolves spontaneously.

Skin tags, also known as acrochordons, are benign skin-colored papules most often found in the skin folds. People with obesity and type 2 diabetes are at higher risk for skin tags. Skin tags may be treated with cryotherapy, surgical excision, or ligation.

Pilomatrixoma is a benign skin tumor derived from hair matrix cells. It is usually a nontender, firm, skin-colored or red-purple subcutaneous nodule that may have calcifications. Treatment is surgical excision.

Amelanotic melanoma is a melanoma with little or no pigment and can present as a skin- or red-colored nodule. While these are quite uncommon, recognition that many pediatric melanomas present as amelanotic lesions makes it important to consider this in the differential diagnosis of growing papules and nodules.7 Treatment and prognosis is similar to that of pigmented melanoma, but as it is often clinically challenging to diagnose because of atypical features, it may be detected in more advanced stages.

Our patient underwent cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen to the nodule given the large size of the lesion, with resolution without recurrence.

Dr. Lee is a pediatric dermatology research fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Lee nor Dr. Eichenfield had any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2017. doi: 10.2174/1872213X11666170518114456.

2. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2013 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2013.06.002.

3. Trop Doct. 2015 Apr. doi: 10.1177/0049475514568133.

4. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013 Jun;63(6):778-9.

5. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0603a15.

6 Molluscum Contagiosum, in “Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases,” 31st ed. (Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018, pp. 565-66).

7. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.953.

A 4-year-old with a lesion on her cheek, which grew and became firmer over two months

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

A 4-year-old female is brought to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a persistent lesion on the cheek.

The mother of the child reports that the lesion started as a small "bug bite" and then started growing and getting firmer for the past 2 months. The girl has developed other smaller red, pimple-like lesions on the cheeks and one of them is starting to increase in size.

She denies any tenderness on the area or any purulent discharge. She has had no fevers, chills, weight loss, nose bleeds, fatigue, or any other symptoms. The mother has not noted any changes on the child's body odor, any rapid growth, or hair on her axillary or pubic area. She was treated with three different courses of oral antibiotics including cephalexin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and clindamycin, as well as topical mupirocin, with no improvement.

Her past medical history is significant for several episodes of eyelid cysts that were treated with warm compresses and topical erythromycin ointment. The family history is significant for the father having severe acne as a teenager. She has two cats, she has not traveled, and she has an older sister who has no lesions.

On physical examination she is a lovely 4-year-old female in no acute distress. Her height is on the 70th percentile and weight on the 40th percentile for her age. Her blood pressure is 95/84 with a heart rate of 96. On skin examination she has several pink macules and papules on her bilateral cheeks. On the left cheek there are two pink nodules: One is 1 cm, and the other is 7 mm. The nodules are not tender. There is no warmth, fluctuance, or discharge from the lesions.

She has no cervical lymphadenopathy. She has no axillary or pubic hair. She is Tanner stage I.

Four-year-old boy presents with itchy rash on face, extremities

Contact dermatitis is an eczematous, pruritic eruption caused by direct contact with a substance and an irritant or allergic reaction. While it may not be contagious or life-threatening, contact dermatitis may be tremendously uncomfortable and impactful. Contact dermatitis may occur from exposure to chemicals in soaps, shampoos, cosmetics, metals, plants and topical products, and medications. The hallmark of contact dermatitis is localized eczematous reactions on the portion of the body that has been directly exposed to the reaction-causing substance. – often with oozing and crusting.

Irritant contact dermatitis is the most common type, which occurs when a substance damages the skin’s outer protective layer and does not require prior exposure or sensitization. Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) can develop after exposure and sensitization, with an external allergen triggering an acute inflammatory response.1 Common causes of ACD include nickel, cobalt, gold, chromium, poison ivy/oak/sumac, cosmetics/personal care products that contain formaldehyde, fragrances, topical medications (anesthetics, antibiotics, corticosteroids), baby wipes, sunscreens, latex materials, protective equipment, soap/cleansers, resins, and acrylics. Among children, nickel sulfate, ammonium persulfate, gold sodium thiosulfate, thimerosal, and toluene-2,5-diamine are the most common sensitizers. Rarely, ACD can be triggered by something that enters the body through foods, flavorings, medicine, or medical or dental procedures (systemic contact dermatitis).

An Id reaction, or autoeczematization, is a generalized acute cutaneous reaction to a variety of stimuli, including infectious and inflammatory skin conditions such as contact dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, or other eczematous dermatitis.3 Id reactions usually are preceded by a preexisting dermatitis. Lesions are, by definition, at a site distant from the primary infection or dermatitis. They often are distributed symmetrically. Papular or papular-vesicular lesions of the extremities and or trunk are common in children.

Our patient had evidence of a localized periocular contact dermatitis reaction that preceded the symmetric papular, eczematous eruption consistent with an id reaction. Our patient was prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5 % ointment for the eyes and triamcinolone 0.1% ointment for the rash on the body, which resulted in significant improvement.

Rosacea is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory skin disorder that primarily involves the central face. Common clinical features include facial erythema, telangiectasias, and inflammatory papules or pustules. Ocular involvement may occur in the presence or absence of cutaneous manifestations. Patients may report the presence of ocular foreign body sensation, burning, photophobia, blurred vision, redness, and tearing. Ocular disease is usually bilateral and is not proportional to the severity of the skin disease.4 Common skin findings are blepharitis, lid margin telangiectasia, tear abnormalities, meibomian gland inflammation, frequent chalazion, bilateral hordeolum, conjunctivitis, and, rarely, corneal ulcers and vascularization. Our patient initially did have bilateral hordeolum in what may seem to be ocular rosacea. However, given the use of a recent topical antibiotic with subsequent eczematous rash of the eyelids and then resulting distant rash on the body 1week later made the rash likely allergic contact dermatitis with id reaction.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic, relapsing, and usually mild form of dermatitis that occurs in infants and in adults. The severity may vary from minimal, asymptomatic scaliness of the scalp (dandruff) to more widespread involvement. It is usually characterized by well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with greasy-looking, yellowish scales distributed on areas rich in sebaceous glands, such as the scalp, the external ear, the center of the face, the upper part of the trunk, and the intertriginous areas.

Psoriasis typically affects the outside of the elbows, knees, or scalp, although it can appear on any location. It tends to go through cycles, flaring for a few weeks or months, then subsiding for a while or going into remission. Ocular involvement is a well known manifestation of psoriasis.5 Psoriatic lesions of the eyelid are rare, even in the erythrodermic variant of the disease. Occasionally, pustular psoriasis may involve the eyelids, with typical psoriatic lesions visible on the skin and lid margin. The reason for the relative sparing of the eyelid skin in patients with psoriasis is unknown. Other manifestations include meibomian gland dysfunction, decreased tear film break-up time, a nonspecific conjunctivitis, and corneal disease secondary to lid disease such as trichiasis.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS), also known as papular acrodermatitis, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and infantile papular acrodermatitis, is a self-limited skin disorder that most often occurs in young children. Viral infections are common GCS precipitating factors . GCS typically manifests as a symmetric, papular eruption, often with larger (3- to 10-mm) flat topped papulovesicles. Classic sites of involvement include the cheeks, buttocks, and extensor surfaces of the forearms and legs. GCS may be pruritic or asymptomatic, and papules typically resolve spontaneously within 2 months. Occasionally, GCS persists for longer periods. The eyelid lesions and localized pattern, with the absence of larger symmetric papules of the buttocks and legs, was not consistent with papular acrodermatitis of childhood.

Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. They had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016 Jun; 74(6):1043-54.

2. Pediatr Dermatol 2016 Jul; 33(4):399-404.

3. Evans M & Bronson D. (2019) Id Reaction (Autoeczematization). Retrieved from emedicine.medscape.com/article/1049760-overview.

4. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004 Dec;15(6):499-502.

5. Clin Dermatol. Mar-Apr 2016;34(2):146-50.

Contact dermatitis is an eczematous, pruritic eruption caused by direct contact with a substance and an irritant or allergic reaction. While it may not be contagious or life-threatening, contact dermatitis may be tremendously uncomfortable and impactful. Contact dermatitis may occur from exposure to chemicals in soaps, shampoos, cosmetics, metals, plants and topical products, and medications. The hallmark of contact dermatitis is localized eczematous reactions on the portion of the body that has been directly exposed to the reaction-causing substance. – often with oozing and crusting.

Irritant contact dermatitis is the most common type, which occurs when a substance damages the skin’s outer protective layer and does not require prior exposure or sensitization. Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) can develop after exposure and sensitization, with an external allergen triggering an acute inflammatory response.1 Common causes of ACD include nickel, cobalt, gold, chromium, poison ivy/oak/sumac, cosmetics/personal care products that contain formaldehyde, fragrances, topical medications (anesthetics, antibiotics, corticosteroids), baby wipes, sunscreens, latex materials, protective equipment, soap/cleansers, resins, and acrylics. Among children, nickel sulfate, ammonium persulfate, gold sodium thiosulfate, thimerosal, and toluene-2,5-diamine are the most common sensitizers. Rarely, ACD can be triggered by something that enters the body through foods, flavorings, medicine, or medical or dental procedures (systemic contact dermatitis).

An Id reaction, or autoeczematization, is a generalized acute cutaneous reaction to a variety of stimuli, including infectious and inflammatory skin conditions such as contact dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, or other eczematous dermatitis.3 Id reactions usually are preceded by a preexisting dermatitis. Lesions are, by definition, at a site distant from the primary infection or dermatitis. They often are distributed symmetrically. Papular or papular-vesicular lesions of the extremities and or trunk are common in children.

Our patient had evidence of a localized periocular contact dermatitis reaction that preceded the symmetric papular, eczematous eruption consistent with an id reaction. Our patient was prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5 % ointment for the eyes and triamcinolone 0.1% ointment for the rash on the body, which resulted in significant improvement.

Rosacea is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory skin disorder that primarily involves the central face. Common clinical features include facial erythema, telangiectasias, and inflammatory papules or pustules. Ocular involvement may occur in the presence or absence of cutaneous manifestations. Patients may report the presence of ocular foreign body sensation, burning, photophobia, blurred vision, redness, and tearing. Ocular disease is usually bilateral and is not proportional to the severity of the skin disease.4 Common skin findings are blepharitis, lid margin telangiectasia, tear abnormalities, meibomian gland inflammation, frequent chalazion, bilateral hordeolum, conjunctivitis, and, rarely, corneal ulcers and vascularization. Our patient initially did have bilateral hordeolum in what may seem to be ocular rosacea. However, given the use of a recent topical antibiotic with subsequent eczematous rash of the eyelids and then resulting distant rash on the body 1week later made the rash likely allergic contact dermatitis with id reaction.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic, relapsing, and usually mild form of dermatitis that occurs in infants and in adults. The severity may vary from minimal, asymptomatic scaliness of the scalp (dandruff) to more widespread involvement. It is usually characterized by well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with greasy-looking, yellowish scales distributed on areas rich in sebaceous glands, such as the scalp, the external ear, the center of the face, the upper part of the trunk, and the intertriginous areas.

Psoriasis typically affects the outside of the elbows, knees, or scalp, although it can appear on any location. It tends to go through cycles, flaring for a few weeks or months, then subsiding for a while or going into remission. Ocular involvement is a well known manifestation of psoriasis.5 Psoriatic lesions of the eyelid are rare, even in the erythrodermic variant of the disease. Occasionally, pustular psoriasis may involve the eyelids, with typical psoriatic lesions visible on the skin and lid margin. The reason for the relative sparing of the eyelid skin in patients with psoriasis is unknown. Other manifestations include meibomian gland dysfunction, decreased tear film break-up time, a nonspecific conjunctivitis, and corneal disease secondary to lid disease such as trichiasis.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS), also known as papular acrodermatitis, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and infantile papular acrodermatitis, is a self-limited skin disorder that most often occurs in young children. Viral infections are common GCS precipitating factors . GCS typically manifests as a symmetric, papular eruption, often with larger (3- to 10-mm) flat topped papulovesicles. Classic sites of involvement include the cheeks, buttocks, and extensor surfaces of the forearms and legs. GCS may be pruritic or asymptomatic, and papules typically resolve spontaneously within 2 months. Occasionally, GCS persists for longer periods. The eyelid lesions and localized pattern, with the absence of larger symmetric papules of the buttocks and legs, was not consistent with papular acrodermatitis of childhood.

Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. They had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016 Jun; 74(6):1043-54.

2. Pediatr Dermatol 2016 Jul; 33(4):399-404.

3. Evans M & Bronson D. (2019) Id Reaction (Autoeczematization). Retrieved from emedicine.medscape.com/article/1049760-overview.

4. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004 Dec;15(6):499-502.

5. Clin Dermatol. Mar-Apr 2016;34(2):146-50.

Contact dermatitis is an eczematous, pruritic eruption caused by direct contact with a substance and an irritant or allergic reaction. While it may not be contagious or life-threatening, contact dermatitis may be tremendously uncomfortable and impactful. Contact dermatitis may occur from exposure to chemicals in soaps, shampoos, cosmetics, metals, plants and topical products, and medications. The hallmark of contact dermatitis is localized eczematous reactions on the portion of the body that has been directly exposed to the reaction-causing substance. – often with oozing and crusting.

Irritant contact dermatitis is the most common type, which occurs when a substance damages the skin’s outer protective layer and does not require prior exposure or sensitization. Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) can develop after exposure and sensitization, with an external allergen triggering an acute inflammatory response.1 Common causes of ACD include nickel, cobalt, gold, chromium, poison ivy/oak/sumac, cosmetics/personal care products that contain formaldehyde, fragrances, topical medications (anesthetics, antibiotics, corticosteroids), baby wipes, sunscreens, latex materials, protective equipment, soap/cleansers, resins, and acrylics. Among children, nickel sulfate, ammonium persulfate, gold sodium thiosulfate, thimerosal, and toluene-2,5-diamine are the most common sensitizers. Rarely, ACD can be triggered by something that enters the body through foods, flavorings, medicine, or medical or dental procedures (systemic contact dermatitis).

An Id reaction, or autoeczematization, is a generalized acute cutaneous reaction to a variety of stimuli, including infectious and inflammatory skin conditions such as contact dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, or other eczematous dermatitis.3 Id reactions usually are preceded by a preexisting dermatitis. Lesions are, by definition, at a site distant from the primary infection or dermatitis. They often are distributed symmetrically. Papular or papular-vesicular lesions of the extremities and or trunk are common in children.

Our patient had evidence of a localized periocular contact dermatitis reaction that preceded the symmetric papular, eczematous eruption consistent with an id reaction. Our patient was prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5 % ointment for the eyes and triamcinolone 0.1% ointment for the rash on the body, which resulted in significant improvement.

Rosacea is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory skin disorder that primarily involves the central face. Common clinical features include facial erythema, telangiectasias, and inflammatory papules or pustules. Ocular involvement may occur in the presence or absence of cutaneous manifestations. Patients may report the presence of ocular foreign body sensation, burning, photophobia, blurred vision, redness, and tearing. Ocular disease is usually bilateral and is not proportional to the severity of the skin disease.4 Common skin findings are blepharitis, lid margin telangiectasia, tear abnormalities, meibomian gland inflammation, frequent chalazion, bilateral hordeolum, conjunctivitis, and, rarely, corneal ulcers and vascularization. Our patient initially did have bilateral hordeolum in what may seem to be ocular rosacea. However, given the use of a recent topical antibiotic with subsequent eczematous rash of the eyelids and then resulting distant rash on the body 1week later made the rash likely allergic contact dermatitis with id reaction.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic, relapsing, and usually mild form of dermatitis that occurs in infants and in adults. The severity may vary from minimal, asymptomatic scaliness of the scalp (dandruff) to more widespread involvement. It is usually characterized by well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with greasy-looking, yellowish scales distributed on areas rich in sebaceous glands, such as the scalp, the external ear, the center of the face, the upper part of the trunk, and the intertriginous areas.

Psoriasis typically affects the outside of the elbows, knees, or scalp, although it can appear on any location. It tends to go through cycles, flaring for a few weeks or months, then subsiding for a while or going into remission. Ocular involvement is a well known manifestation of psoriasis.5 Psoriatic lesions of the eyelid are rare, even in the erythrodermic variant of the disease. Occasionally, pustular psoriasis may involve the eyelids, with typical psoriatic lesions visible on the skin and lid margin. The reason for the relative sparing of the eyelid skin in patients with psoriasis is unknown. Other manifestations include meibomian gland dysfunction, decreased tear film break-up time, a nonspecific conjunctivitis, and corneal disease secondary to lid disease such as trichiasis.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS), also known as papular acrodermatitis, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and infantile papular acrodermatitis, is a self-limited skin disorder that most often occurs in young children. Viral infections are common GCS precipitating factors . GCS typically manifests as a symmetric, papular eruption, often with larger (3- to 10-mm) flat topped papulovesicles. Classic sites of involvement include the cheeks, buttocks, and extensor surfaces of the forearms and legs. GCS may be pruritic or asymptomatic, and papules typically resolve spontaneously within 2 months. Occasionally, GCS persists for longer periods. The eyelid lesions and localized pattern, with the absence of larger symmetric papules of the buttocks and legs, was not consistent with papular acrodermatitis of childhood.

Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. They had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016 Jun; 74(6):1043-54.

2. Pediatr Dermatol 2016 Jul; 33(4):399-404.

3. Evans M & Bronson D. (2019) Id Reaction (Autoeczematization). Retrieved from emedicine.medscape.com/article/1049760-overview.

4. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004 Dec;15(6):499-502.

5. Clin Dermatol. Mar-Apr 2016;34(2):146-50.

A 4-year-old healthy male with no significant prior medical history presents for evaluation of "itchy bumps" on the face and extremities of 2 weeks' duration.

The child was well until around 2 and a half weeks ago when he presented for evaluation of two lesions on the lower eyelids, diagnosed as hordeolum (a stye). He was prescribed ofloxacin ophthalmic solution.