User login

Prenatal exposure to pollutants consumed through diet found to be associated with decreased fetal growth

Ideally, chemicals that are toxic to human health are identified and removed from use. Many such chemicals, known as persistent organic pollutants (POPs), have been studied individually for their ill effects in humans. DDT, for instance, once a widely used insecticide, is now classified as a probable human carcinogen and has not been used in the United States since the early 1970s.1 Other insecticides have similarly been banned but have long half-lives and can persist in the environment for decades. Humans are exposed to POPs mainly through diet, say Ouidir and colleagues, with exposure “nearly ubiquitous.”2

The association between POP exposure during pregnancy and birth weight has not been established, as results from previous studies have been inconsistent, according to researchers.2 In addition, birth weight does not distinguish growth-restricted fetuses from those that are constitutionally small. Therefore, Ouidir and colleagues analyzed maternal plasma levels of POPs and measures of fetal growth. Their research was published in JAMA Pediatrics.2

The investigators examined chemical class mixtures of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs), dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), among other groups of POPs, as well as individual chemicals, in 2,284 nonobese low-risk pregnant women before 14 weeks of gestation. They measured 14 fetal growth biometrics using ultrasonography throughout the women’s pregnancies, with researchers focusing their main findings on head and abdominal circumference and femur length measurements.

The researchers found that the OCP mixture was negatively associated with most fetal growth measures, with a reduction of 4.7 mm (95% confidence interval [CI], -6.7 to -2.8 mm) in head circumference, 3.5 mm (95% CI, -4.7 to -2.2) in abdominal circumference, and 0.6 mm (95% CI, -1.1 to -0.2 mm) in femur length. In addition, exposure to the PCB and PBDE mixtures were associated with reduced abdominal circumference.

OCPs have been associated with adverse effects on the endocrine system, lipid metabolism, and embryonic development. They also can result in hematologic and hepatic alterations.3

The JAMA Pediatrics study authors point out that their findings may not take into account the risk pregnant women with occupational exposure to POPs, or other higher exposure situations, may have, as the POP concentrations in their sample were low compared with levels in a nationally representative sample of pregnant women. They say that their findings provide insight into the “implications of POPs for fetal growth when exposures are low and suggest that, even if exposures could be successfully minimized, these associations may persist.”2

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. DDT: A brief history and status. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/ddt-brief-history-and-status. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Ouidir M, Buck Louis GM, Kanner J, et al. Association of maternal exposure to persistent organic pollutants in early pregnancy with fetal growth. JAMA Pediatr. December 30, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5104.

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati P, Maipas S, Kotampasi C, et al. Chemical pesticides and human health: the urgent need for a new concept in agriculture. Front Public Health. 2016;4:148.

Ideally, chemicals that are toxic to human health are identified and removed from use. Many such chemicals, known as persistent organic pollutants (POPs), have been studied individually for their ill effects in humans. DDT, for instance, once a widely used insecticide, is now classified as a probable human carcinogen and has not been used in the United States since the early 1970s.1 Other insecticides have similarly been banned but have long half-lives and can persist in the environment for decades. Humans are exposed to POPs mainly through diet, say Ouidir and colleagues, with exposure “nearly ubiquitous.”2

The association between POP exposure during pregnancy and birth weight has not been established, as results from previous studies have been inconsistent, according to researchers.2 In addition, birth weight does not distinguish growth-restricted fetuses from those that are constitutionally small. Therefore, Ouidir and colleagues analyzed maternal plasma levels of POPs and measures of fetal growth. Their research was published in JAMA Pediatrics.2

The investigators examined chemical class mixtures of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs), dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), among other groups of POPs, as well as individual chemicals, in 2,284 nonobese low-risk pregnant women before 14 weeks of gestation. They measured 14 fetal growth biometrics using ultrasonography throughout the women’s pregnancies, with researchers focusing their main findings on head and abdominal circumference and femur length measurements.

The researchers found that the OCP mixture was negatively associated with most fetal growth measures, with a reduction of 4.7 mm (95% confidence interval [CI], -6.7 to -2.8 mm) in head circumference, 3.5 mm (95% CI, -4.7 to -2.2) in abdominal circumference, and 0.6 mm (95% CI, -1.1 to -0.2 mm) in femur length. In addition, exposure to the PCB and PBDE mixtures were associated with reduced abdominal circumference.

OCPs have been associated with adverse effects on the endocrine system, lipid metabolism, and embryonic development. They also can result in hematologic and hepatic alterations.3

The JAMA Pediatrics study authors point out that their findings may not take into account the risk pregnant women with occupational exposure to POPs, or other higher exposure situations, may have, as the POP concentrations in their sample were low compared with levels in a nationally representative sample of pregnant women. They say that their findings provide insight into the “implications of POPs for fetal growth when exposures are low and suggest that, even if exposures could be successfully minimized, these associations may persist.”2

Ideally, chemicals that are toxic to human health are identified and removed from use. Many such chemicals, known as persistent organic pollutants (POPs), have been studied individually for their ill effects in humans. DDT, for instance, once a widely used insecticide, is now classified as a probable human carcinogen and has not been used in the United States since the early 1970s.1 Other insecticides have similarly been banned but have long half-lives and can persist in the environment for decades. Humans are exposed to POPs mainly through diet, say Ouidir and colleagues, with exposure “nearly ubiquitous.”2

The association between POP exposure during pregnancy and birth weight has not been established, as results from previous studies have been inconsistent, according to researchers.2 In addition, birth weight does not distinguish growth-restricted fetuses from those that are constitutionally small. Therefore, Ouidir and colleagues analyzed maternal plasma levels of POPs and measures of fetal growth. Their research was published in JAMA Pediatrics.2

The investigators examined chemical class mixtures of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs), dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), among other groups of POPs, as well as individual chemicals, in 2,284 nonobese low-risk pregnant women before 14 weeks of gestation. They measured 14 fetal growth biometrics using ultrasonography throughout the women’s pregnancies, with researchers focusing their main findings on head and abdominal circumference and femur length measurements.

The researchers found that the OCP mixture was negatively associated with most fetal growth measures, with a reduction of 4.7 mm (95% confidence interval [CI], -6.7 to -2.8 mm) in head circumference, 3.5 mm (95% CI, -4.7 to -2.2) in abdominal circumference, and 0.6 mm (95% CI, -1.1 to -0.2 mm) in femur length. In addition, exposure to the PCB and PBDE mixtures were associated with reduced abdominal circumference.

OCPs have been associated with adverse effects on the endocrine system, lipid metabolism, and embryonic development. They also can result in hematologic and hepatic alterations.3

The JAMA Pediatrics study authors point out that their findings may not take into account the risk pregnant women with occupational exposure to POPs, or other higher exposure situations, may have, as the POP concentrations in their sample were low compared with levels in a nationally representative sample of pregnant women. They say that their findings provide insight into the “implications of POPs for fetal growth when exposures are low and suggest that, even if exposures could be successfully minimized, these associations may persist.”2

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. DDT: A brief history and status. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/ddt-brief-history-and-status. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Ouidir M, Buck Louis GM, Kanner J, et al. Association of maternal exposure to persistent organic pollutants in early pregnancy with fetal growth. JAMA Pediatr. December 30, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5104.

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati P, Maipas S, Kotampasi C, et al. Chemical pesticides and human health: the urgent need for a new concept in agriculture. Front Public Health. 2016;4:148.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. DDT: A brief history and status. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/ddt-brief-history-and-status. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- Ouidir M, Buck Louis GM, Kanner J, et al. Association of maternal exposure to persistent organic pollutants in early pregnancy with fetal growth. JAMA Pediatr. December 30, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5104.

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati P, Maipas S, Kotampasi C, et al. Chemical pesticides and human health: the urgent need for a new concept in agriculture. Front Public Health. 2016;4:148.

Is elagolix effective at reducing HMB for women with varying fibroid sizes and types?

Whether or not women experience symptoms from uterine fibroid(s) can be dependent on a fibroid’s size and location. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is the most common symptom resulting from fibroids, and it occurs in up to one-third of women with fibroids. For fibroids that are large (>10 cm), “bulk” symptoms may occur, including pelvic pressure, urinary urgency or frequency, incontinence, constipation, abdominal protrusion, etc.1

Elagolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonist, was US Food and Drug Administration–approved in 2018 to treat moderate to severe pain caused by endometriosis. 2 Elagolix is being evaluated in 2 phase 3 randomized, double-blind trials for the additional treatment of HMB associated with uterine fibroids. The results of these studies were presented at the 2019 AAGL meeting on November 12, in Vancouver, Canada.

Phase 3 study details

Premenopausal women aged 18 to 51 years were included in the Elaris UF-1 and UF-2 studies if they had HMB (defined using the alkaline hematin methodology as menstrual blood loss [MBL] >80 mL/cycle) and uterine fibroids as confirmed through ultrasound. Because elagolix suppresses estrogen and progesterone, treatment results in dose- and duration-dependent decreases in bone mineral density (BMD),2 and add-back therapy can lessen these adverse effects. Subsequently, participants were randomly assigned 1:1:2 to placebo, elagolix 300 mg twice daily, or elagolix 300 mg twice daily with add-back therapy (1 mg estradiol/0.5 mg norethidrone acetate [E2/NETA]) once daily. Uterine volume and size and location of uterine fibroid(s) were assessed by ultrasound. Subgroups were defined by baseline FIGO categories, grouped FIGO 0-3, FIGO 4, or FIGO 5-8.3

Over the 6-month studies, 72.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 67.65–76.73) of the 395 women who received elagolix plus E2/NETA achieved < 80 mL MBL during the final month and ≥ 50% MBL reduction from baseline to the final month. When stratified by FIGO classification, the results were similar for all subgroups: FIGO 0-3, 77.7% (95% CI, 67.21–80.85). Similar results were seen in women with a primary fibroid volume of either greater or less than 36.2 cm3 (median).3

The most frequently reported adverse events among women taking elagolix plus E2/NETA were hot flushes, night sweats, nausea, and headache. Changes in BMD among these women were not significant compared with women taking placebo.3

The Elaris UF-1 and UF-2 studies are funded by AbbVie Inc.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480.

- Orilissa [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie; August 2019.

- Al-Hendy A, Simon J, Hurtado S, et al. Effect of fibroid location and size on efficacy in elagolix: results from phase 3 clinical trials. Paper presented at: 48th Annual Meeting of the AAGL; November 2019; Vancouver, Canada.

Whether or not women experience symptoms from uterine fibroid(s) can be dependent on a fibroid’s size and location. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is the most common symptom resulting from fibroids, and it occurs in up to one-third of women with fibroids. For fibroids that are large (>10 cm), “bulk” symptoms may occur, including pelvic pressure, urinary urgency or frequency, incontinence, constipation, abdominal protrusion, etc.1

Elagolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonist, was US Food and Drug Administration–approved in 2018 to treat moderate to severe pain caused by endometriosis. 2 Elagolix is being evaluated in 2 phase 3 randomized, double-blind trials for the additional treatment of HMB associated with uterine fibroids. The results of these studies were presented at the 2019 AAGL meeting on November 12, in Vancouver, Canada.

Phase 3 study details

Premenopausal women aged 18 to 51 years were included in the Elaris UF-1 and UF-2 studies if they had HMB (defined using the alkaline hematin methodology as menstrual blood loss [MBL] >80 mL/cycle) and uterine fibroids as confirmed through ultrasound. Because elagolix suppresses estrogen and progesterone, treatment results in dose- and duration-dependent decreases in bone mineral density (BMD),2 and add-back therapy can lessen these adverse effects. Subsequently, participants were randomly assigned 1:1:2 to placebo, elagolix 300 mg twice daily, or elagolix 300 mg twice daily with add-back therapy (1 mg estradiol/0.5 mg norethidrone acetate [E2/NETA]) once daily. Uterine volume and size and location of uterine fibroid(s) were assessed by ultrasound. Subgroups were defined by baseline FIGO categories, grouped FIGO 0-3, FIGO 4, or FIGO 5-8.3

Over the 6-month studies, 72.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 67.65–76.73) of the 395 women who received elagolix plus E2/NETA achieved < 80 mL MBL during the final month and ≥ 50% MBL reduction from baseline to the final month. When stratified by FIGO classification, the results were similar for all subgroups: FIGO 0-3, 77.7% (95% CI, 67.21–80.85). Similar results were seen in women with a primary fibroid volume of either greater or less than 36.2 cm3 (median).3

The most frequently reported adverse events among women taking elagolix plus E2/NETA were hot flushes, night sweats, nausea, and headache. Changes in BMD among these women were not significant compared with women taking placebo.3

The Elaris UF-1 and UF-2 studies are funded by AbbVie Inc.

Whether or not women experience symptoms from uterine fibroid(s) can be dependent on a fibroid’s size and location. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is the most common symptom resulting from fibroids, and it occurs in up to one-third of women with fibroids. For fibroids that are large (>10 cm), “bulk” symptoms may occur, including pelvic pressure, urinary urgency or frequency, incontinence, constipation, abdominal protrusion, etc.1

Elagolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonist, was US Food and Drug Administration–approved in 2018 to treat moderate to severe pain caused by endometriosis. 2 Elagolix is being evaluated in 2 phase 3 randomized, double-blind trials for the additional treatment of HMB associated with uterine fibroids. The results of these studies were presented at the 2019 AAGL meeting on November 12, in Vancouver, Canada.

Phase 3 study details

Premenopausal women aged 18 to 51 years were included in the Elaris UF-1 and UF-2 studies if they had HMB (defined using the alkaline hematin methodology as menstrual blood loss [MBL] >80 mL/cycle) and uterine fibroids as confirmed through ultrasound. Because elagolix suppresses estrogen and progesterone, treatment results in dose- and duration-dependent decreases in bone mineral density (BMD),2 and add-back therapy can lessen these adverse effects. Subsequently, participants were randomly assigned 1:1:2 to placebo, elagolix 300 mg twice daily, or elagolix 300 mg twice daily with add-back therapy (1 mg estradiol/0.5 mg norethidrone acetate [E2/NETA]) once daily. Uterine volume and size and location of uterine fibroid(s) were assessed by ultrasound. Subgroups were defined by baseline FIGO categories, grouped FIGO 0-3, FIGO 4, or FIGO 5-8.3

Over the 6-month studies, 72.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 67.65–76.73) of the 395 women who received elagolix plus E2/NETA achieved < 80 mL MBL during the final month and ≥ 50% MBL reduction from baseline to the final month. When stratified by FIGO classification, the results were similar for all subgroups: FIGO 0-3, 77.7% (95% CI, 67.21–80.85). Similar results were seen in women with a primary fibroid volume of either greater or less than 36.2 cm3 (median).3

The most frequently reported adverse events among women taking elagolix plus E2/NETA were hot flushes, night sweats, nausea, and headache. Changes in BMD among these women were not significant compared with women taking placebo.3

The Elaris UF-1 and UF-2 studies are funded by AbbVie Inc.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480.

- Orilissa [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie; August 2019.

- Al-Hendy A, Simon J, Hurtado S, et al. Effect of fibroid location and size on efficacy in elagolix: results from phase 3 clinical trials. Paper presented at: 48th Annual Meeting of the AAGL; November 2019; Vancouver, Canada.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480.

- Orilissa [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie; August 2019.

- Al-Hendy A, Simon J, Hurtado S, et al. Effect of fibroid location and size on efficacy in elagolix: results from phase 3 clinical trials. Paper presented at: 48th Annual Meeting of the AAGL; November 2019; Vancouver, Canada.

What does the REPLENISH trial reveal about E2/P4’s ability to affect VMS and sleep and appropriate dosing for smokers?

The REPLENISH trial evaluated the oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone (E2/P4) softgel capsule (TX-001HR; 1 mg E2/100 mg P4) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in October 2018 as Bijuva (TherapeuticsMD) for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS) due to menopause. In separate subanalyses presented at the annual Scientific Meeting of the North American Menopause Society in Chicago, Illinois (September 25-28, 2019), researchers examined E2/P4’s ability to address VMS according to age and body mass index (BMI), ability to address sleep, and appropriate dosing in smokers versus nonsmokers.

REPLENISH

The REPLENISH trial was a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of E2/P4 for the treatment of VMS in 1,835 postmenopausal women aged 40 to 65 years with a uterus. Women with moderate to severe VMS (≥7/day or ≥50/week) were randomly assigned to E2/P4 (mg/mg) 1/100, 0.5/100, 0.5/50, 0.25/50, or placebo.1

E2/P4 and VMS according to age and BMI

Percent changes in the weekly frequency and severity of moderate to severe VMS from baseline to weeks 4 and 12 versus placebo were analyzed by age (<55 and ≥55 years) and BMI in the study participants.1 The BMI subgroups had similar baseline VMS, but women in the younger age group had higher baseline frequency of moderate to severe VMS than women in the older age group.

Age. The percent changes in VMS frequency from baseline for women treated with E2/P4 were similar at weeks 4 and 12 between age groups. While subgroup analyses were not powered for statistical significance, significant differences were observed between E2/P4 dosages and placebo at week 12. For VMS severity, the percent changes from baseline for women treated with E2/P4 ranged from 16% to 22% at week 4 and 24% to 51% for either age group at week 12.

BMI. When analyzed by BMI, larger percent reductions from baseline in VMS frequency and severity were observed with E2/P4 dosaging versus placebo, with some groups meeting statistical significance at both weeks 4 and 12.

The authors concluded that their subgroup analyses show a consistency of efficacy for VMS frequency and severity among the different age group and BMI populations of women treated with E2/P4.

E2/P4 and sleep outcomes

Participants in the REPLENISH trial took 2 surveys related to sleep—the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS)-Sleep, a 12-item questionnaire measuring 6 sleep dimensions, and the Menopause-specific Quality of Life (MENQOL), which included a “difficulty sleeping” item.2 Except for women treated with E2/P4 0.25/50 at week 12, women receiving E2/P4 reported significantly better change in the MOS-Sleep total, as well as better ratings on sleep problems and disturbance subscales, than women treated with placebo at week 12 and months 6 and 12. The incidence of somnolence was low with E2/P4 treatment. In addition, sleep mediation models showed that E2/P4 improved MOS-sleep disturbances indirectly through improvements in VMS. The study authors concluded that women taking E2/P4 for moderate to severe VMS may experience improved sleep.

Smoking and E2/P4 dosage

Among postmenopausal women, smoking has been shown to reduce the efficacy of hormone therapy.3 Researchers found that nonsmokers (never or past smokers) may benefit more from a lower E2/P4 dosage than current smokers (<15 cigarettes per day).4 (Women smoking ≥15 cigarettes per day or any e-cigarettes were excluded from REPLENISH). Compared with nonsmokers taking placebo, nonsmokers taking any dosage of E2/P4 had a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in VMS frequency and severity beginning at week 4 and maintained through week 12 (except for the E2/P4 dosage of 0.5/50 at week 4 for severity). By contrast, current smokers in any E2/P4 group had no significant VMS improvements from baseline to weeks 4 and 12 compared with placebo, and proportions of smokers who did measure some response to treatment (at both ≥50% and ≥75% levels) were not different from placebo at weeks 4 and 12. In addition, current smokers had significantly lower median levels of systemic estradiol and estrone concentrations with all E2/P4 treatment groups than did nonsmokers, despite both groups having similar estradiol and estrone concentrations at baseline.

- Bitner D, Brightman R, Graham S, et al. E2/P4 capsules effectively treat vasomotor symptoms irrespective of age and BMI. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Kaunitz AM, Kagan R, Graham S, et al. Oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone (E2/P4) improved sleep outcomes in the REPLENISH trial. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Jensen J, Christiansen C, Rodbro P. Cigarette smoking, serum estrogens, and bone loss during hormone-replacement therapy after menopause. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:973-975.

- Constantine GD, Santoro N, Graham S, et al. Nonsmokers may benefit from lower doses of an oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone capsule—data from the REPLENISH trial. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

The REPLENISH trial evaluated the oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone (E2/P4) softgel capsule (TX-001HR; 1 mg E2/100 mg P4) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in October 2018 as Bijuva (TherapeuticsMD) for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS) due to menopause. In separate subanalyses presented at the annual Scientific Meeting of the North American Menopause Society in Chicago, Illinois (September 25-28, 2019), researchers examined E2/P4’s ability to address VMS according to age and body mass index (BMI), ability to address sleep, and appropriate dosing in smokers versus nonsmokers.

REPLENISH

The REPLENISH trial was a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of E2/P4 for the treatment of VMS in 1,835 postmenopausal women aged 40 to 65 years with a uterus. Women with moderate to severe VMS (≥7/day or ≥50/week) were randomly assigned to E2/P4 (mg/mg) 1/100, 0.5/100, 0.5/50, 0.25/50, or placebo.1

E2/P4 and VMS according to age and BMI

Percent changes in the weekly frequency and severity of moderate to severe VMS from baseline to weeks 4 and 12 versus placebo were analyzed by age (<55 and ≥55 years) and BMI in the study participants.1 The BMI subgroups had similar baseline VMS, but women in the younger age group had higher baseline frequency of moderate to severe VMS than women in the older age group.

Age. The percent changes in VMS frequency from baseline for women treated with E2/P4 were similar at weeks 4 and 12 between age groups. While subgroup analyses were not powered for statistical significance, significant differences were observed between E2/P4 dosages and placebo at week 12. For VMS severity, the percent changes from baseline for women treated with E2/P4 ranged from 16% to 22% at week 4 and 24% to 51% for either age group at week 12.

BMI. When analyzed by BMI, larger percent reductions from baseline in VMS frequency and severity were observed with E2/P4 dosaging versus placebo, with some groups meeting statistical significance at both weeks 4 and 12.

The authors concluded that their subgroup analyses show a consistency of efficacy for VMS frequency and severity among the different age group and BMI populations of women treated with E2/P4.

E2/P4 and sleep outcomes

Participants in the REPLENISH trial took 2 surveys related to sleep—the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS)-Sleep, a 12-item questionnaire measuring 6 sleep dimensions, and the Menopause-specific Quality of Life (MENQOL), which included a “difficulty sleeping” item.2 Except for women treated with E2/P4 0.25/50 at week 12, women receiving E2/P4 reported significantly better change in the MOS-Sleep total, as well as better ratings on sleep problems and disturbance subscales, than women treated with placebo at week 12 and months 6 and 12. The incidence of somnolence was low with E2/P4 treatment. In addition, sleep mediation models showed that E2/P4 improved MOS-sleep disturbances indirectly through improvements in VMS. The study authors concluded that women taking E2/P4 for moderate to severe VMS may experience improved sleep.

Smoking and E2/P4 dosage

Among postmenopausal women, smoking has been shown to reduce the efficacy of hormone therapy.3 Researchers found that nonsmokers (never or past smokers) may benefit more from a lower E2/P4 dosage than current smokers (<15 cigarettes per day).4 (Women smoking ≥15 cigarettes per day or any e-cigarettes were excluded from REPLENISH). Compared with nonsmokers taking placebo, nonsmokers taking any dosage of E2/P4 had a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in VMS frequency and severity beginning at week 4 and maintained through week 12 (except for the E2/P4 dosage of 0.5/50 at week 4 for severity). By contrast, current smokers in any E2/P4 group had no significant VMS improvements from baseline to weeks 4 and 12 compared with placebo, and proportions of smokers who did measure some response to treatment (at both ≥50% and ≥75% levels) were not different from placebo at weeks 4 and 12. In addition, current smokers had significantly lower median levels of systemic estradiol and estrone concentrations with all E2/P4 treatment groups than did nonsmokers, despite both groups having similar estradiol and estrone concentrations at baseline.

The REPLENISH trial evaluated the oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone (E2/P4) softgel capsule (TX-001HR; 1 mg E2/100 mg P4) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in October 2018 as Bijuva (TherapeuticsMD) for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS) due to menopause. In separate subanalyses presented at the annual Scientific Meeting of the North American Menopause Society in Chicago, Illinois (September 25-28, 2019), researchers examined E2/P4’s ability to address VMS according to age and body mass index (BMI), ability to address sleep, and appropriate dosing in smokers versus nonsmokers.

REPLENISH

The REPLENISH trial was a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of E2/P4 for the treatment of VMS in 1,835 postmenopausal women aged 40 to 65 years with a uterus. Women with moderate to severe VMS (≥7/day or ≥50/week) were randomly assigned to E2/P4 (mg/mg) 1/100, 0.5/100, 0.5/50, 0.25/50, or placebo.1

E2/P4 and VMS according to age and BMI

Percent changes in the weekly frequency and severity of moderate to severe VMS from baseline to weeks 4 and 12 versus placebo were analyzed by age (<55 and ≥55 years) and BMI in the study participants.1 The BMI subgroups had similar baseline VMS, but women in the younger age group had higher baseline frequency of moderate to severe VMS than women in the older age group.

Age. The percent changes in VMS frequency from baseline for women treated with E2/P4 were similar at weeks 4 and 12 between age groups. While subgroup analyses were not powered for statistical significance, significant differences were observed between E2/P4 dosages and placebo at week 12. For VMS severity, the percent changes from baseline for women treated with E2/P4 ranged from 16% to 22% at week 4 and 24% to 51% for either age group at week 12.

BMI. When analyzed by BMI, larger percent reductions from baseline in VMS frequency and severity were observed with E2/P4 dosaging versus placebo, with some groups meeting statistical significance at both weeks 4 and 12.

The authors concluded that their subgroup analyses show a consistency of efficacy for VMS frequency and severity among the different age group and BMI populations of women treated with E2/P4.

E2/P4 and sleep outcomes

Participants in the REPLENISH trial took 2 surveys related to sleep—the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS)-Sleep, a 12-item questionnaire measuring 6 sleep dimensions, and the Menopause-specific Quality of Life (MENQOL), which included a “difficulty sleeping” item.2 Except for women treated with E2/P4 0.25/50 at week 12, women receiving E2/P4 reported significantly better change in the MOS-Sleep total, as well as better ratings on sleep problems and disturbance subscales, than women treated with placebo at week 12 and months 6 and 12. The incidence of somnolence was low with E2/P4 treatment. In addition, sleep mediation models showed that E2/P4 improved MOS-sleep disturbances indirectly through improvements in VMS. The study authors concluded that women taking E2/P4 for moderate to severe VMS may experience improved sleep.

Smoking and E2/P4 dosage

Among postmenopausal women, smoking has been shown to reduce the efficacy of hormone therapy.3 Researchers found that nonsmokers (never or past smokers) may benefit more from a lower E2/P4 dosage than current smokers (<15 cigarettes per day).4 (Women smoking ≥15 cigarettes per day or any e-cigarettes were excluded from REPLENISH). Compared with nonsmokers taking placebo, nonsmokers taking any dosage of E2/P4 had a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in VMS frequency and severity beginning at week 4 and maintained through week 12 (except for the E2/P4 dosage of 0.5/50 at week 4 for severity). By contrast, current smokers in any E2/P4 group had no significant VMS improvements from baseline to weeks 4 and 12 compared with placebo, and proportions of smokers who did measure some response to treatment (at both ≥50% and ≥75% levels) were not different from placebo at weeks 4 and 12. In addition, current smokers had significantly lower median levels of systemic estradiol and estrone concentrations with all E2/P4 treatment groups than did nonsmokers, despite both groups having similar estradiol and estrone concentrations at baseline.

- Bitner D, Brightman R, Graham S, et al. E2/P4 capsules effectively treat vasomotor symptoms irrespective of age and BMI. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Kaunitz AM, Kagan R, Graham S, et al. Oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone (E2/P4) improved sleep outcomes in the REPLENISH trial. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Jensen J, Christiansen C, Rodbro P. Cigarette smoking, serum estrogens, and bone loss during hormone-replacement therapy after menopause. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:973-975.

- Constantine GD, Santoro N, Graham S, et al. Nonsmokers may benefit from lower doses of an oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone capsule—data from the REPLENISH trial. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Bitner D, Brightman R, Graham S, et al. E2/P4 capsules effectively treat vasomotor symptoms irrespective of age and BMI. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Kaunitz AM, Kagan R, Graham S, et al. Oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone (E2/P4) improved sleep outcomes in the REPLENISH trial. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Jensen J, Christiansen C, Rodbro P. Cigarette smoking, serum estrogens, and bone loss during hormone-replacement therapy after menopause. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:973-975.

- Constantine GD, Santoro N, Graham S, et al. Nonsmokers may benefit from lower doses of an oral 17β-estradiol/progesterone capsule—data from the REPLENISH trial. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

Postmenopausal women would benefit from clinician-initiated discussion of GSM symptoms

Researchers from Kaiser Permanente Northwest and Oregon Health & Science University, both in Portland, performed a secondary analysis of a survey of postmenopausal women conducted to assess the impact of a health system intervention on genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). They presented their results at the recent annual Scientific Meeting of the North American Menopause Society in Chicago, Illinois (September 25-28, 2019). The intervention included clinician education and computer support tools and was assessed in a clinic-based, cluster-randomized trial in which primary care and gynecology clinics either received the intervention or did not. Women received follow-up 2 weeks after a well-woman visit with a survey that elicited vulvovaginal, sexual, and urinary symptoms with bother.

About 45% of those responding to the survey (N = 1,533) reported 1 or more vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) symptoms—on average described as somewhat or moderately bothersome—but less than half of those women (39%) discussed their symptom(s) at their well-woman visit. Typically it was the woman, rather than the clinician, who initiated the discussion of the VVA symptom(s) (59% vs 22%, respectively). About 16% of women reported that both parties brought up the symptom(s). Most women (83%) were satisfied with the VVA symptom discussion. Of the women not having such a discussion, 18% wished that one had occurred. A VVA symptom discussion was positively associated with clinicians providing written materials, suggesting lubricants or vaginal estrogen, and providing a referral. Therefore, there is a greater role for clinician-initiated screening for GSM, the study authors concluded.

- Clark AL, Bulkley JE, Bennett AT, et al. Discussion of vulvovaginal health at postmenopausal well woman visit—patient characteristics and visit experiences. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

Researchers from Kaiser Permanente Northwest and Oregon Health & Science University, both in Portland, performed a secondary analysis of a survey of postmenopausal women conducted to assess the impact of a health system intervention on genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). They presented their results at the recent annual Scientific Meeting of the North American Menopause Society in Chicago, Illinois (September 25-28, 2019). The intervention included clinician education and computer support tools and was assessed in a clinic-based, cluster-randomized trial in which primary care and gynecology clinics either received the intervention or did not. Women received follow-up 2 weeks after a well-woman visit with a survey that elicited vulvovaginal, sexual, and urinary symptoms with bother.

About 45% of those responding to the survey (N = 1,533) reported 1 or more vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) symptoms—on average described as somewhat or moderately bothersome—but less than half of those women (39%) discussed their symptom(s) at their well-woman visit. Typically it was the woman, rather than the clinician, who initiated the discussion of the VVA symptom(s) (59% vs 22%, respectively). About 16% of women reported that both parties brought up the symptom(s). Most women (83%) were satisfied with the VVA symptom discussion. Of the women not having such a discussion, 18% wished that one had occurred. A VVA symptom discussion was positively associated with clinicians providing written materials, suggesting lubricants or vaginal estrogen, and providing a referral. Therefore, there is a greater role for clinician-initiated screening for GSM, the study authors concluded.

Researchers from Kaiser Permanente Northwest and Oregon Health & Science University, both in Portland, performed a secondary analysis of a survey of postmenopausal women conducted to assess the impact of a health system intervention on genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). They presented their results at the recent annual Scientific Meeting of the North American Menopause Society in Chicago, Illinois (September 25-28, 2019). The intervention included clinician education and computer support tools and was assessed in a clinic-based, cluster-randomized trial in which primary care and gynecology clinics either received the intervention or did not. Women received follow-up 2 weeks after a well-woman visit with a survey that elicited vulvovaginal, sexual, and urinary symptoms with bother.

About 45% of those responding to the survey (N = 1,533) reported 1 or more vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) symptoms—on average described as somewhat or moderately bothersome—but less than half of those women (39%) discussed their symptom(s) at their well-woman visit. Typically it was the woman, rather than the clinician, who initiated the discussion of the VVA symptom(s) (59% vs 22%, respectively). About 16% of women reported that both parties brought up the symptom(s). Most women (83%) were satisfied with the VVA symptom discussion. Of the women not having such a discussion, 18% wished that one had occurred. A VVA symptom discussion was positively associated with clinicians providing written materials, suggesting lubricants or vaginal estrogen, and providing a referral. Therefore, there is a greater role for clinician-initiated screening for GSM, the study authors concluded.

- Clark AL, Bulkley JE, Bennett AT, et al. Discussion of vulvovaginal health at postmenopausal well woman visit—patient characteristics and visit experiences. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

- Clark AL, Bulkley JE, Bennett AT, et al. Discussion of vulvovaginal health at postmenopausal well woman visit—patient characteristics and visit experiences. Poster presented at: North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting; September 25-28, 2019; Chicago, IL.

ObGyn compensation: Strides in the gender wage gap indicate closure possible

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

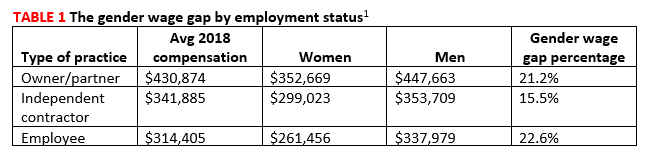

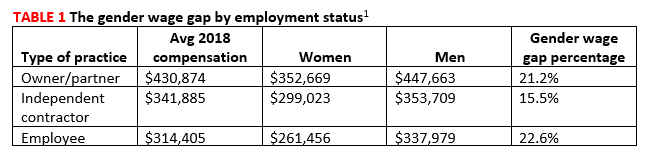

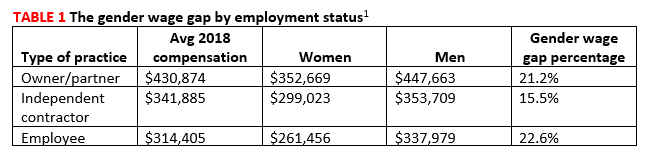

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

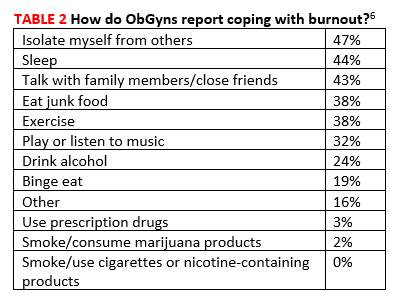

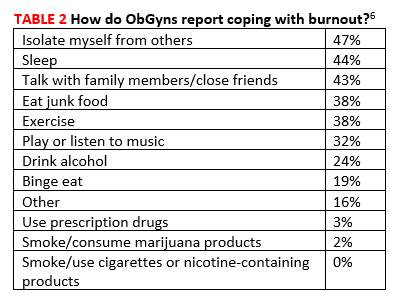

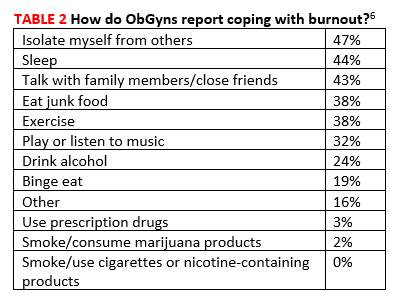

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

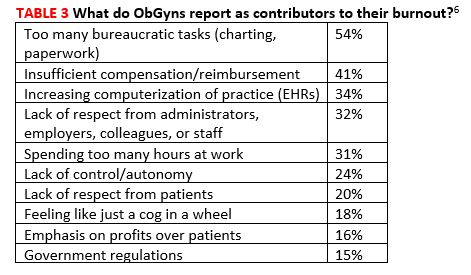

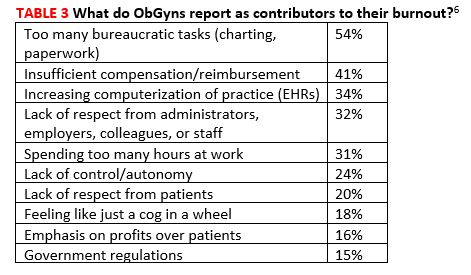

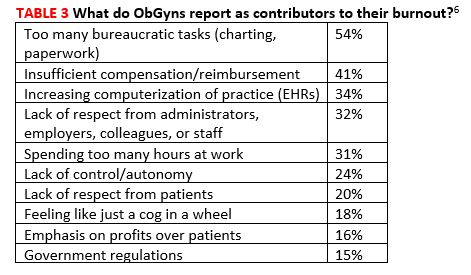

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.

In addition to utilizing an NP workforce, Skinner and colleagues suggest that further strategies will be needed to address the rural physician shortfall and greater patient workload. Although certain actions instituted in the past have been helpful, including physician loan repayment, expansion of the national health service corps, medical school grants, and funding of rural teaching clinics, they have not done enough to address the growing needs of rural patient populations. The authors additionally suggest2:

- expansion of graduate medical education programs in rural hospitals

- higher payments for physicians in rural areas

- expanding use of mobile health vans equipped with diagnostic and treatment technology

- overcoming barriers that have slowed adoption of telehealth services.

References

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Morr M. Nurse practitioners may alleviate dwindling physician workforce in rural populations. Clinical Advisor.

- Doximity. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Third annual study. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round4.pdf Color/Word_R0_G0_B255 March 2019. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Women were majority of US medical school applicants in 2018. Press release, December 4, 2018. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-data-2018/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, et al. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout, depression and suicide report 2019. January 16, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape obstetrician and gynecologist lifestyle, happiness and burnout report 2019. February 20, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-obgyn-6011131Color/Word_R0_G0_B255. Accessed August 20, 2019.

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.

In addition to utilizing an NP workforce, Skinner and colleagues suggest that further strategies will be needed to address the rural physician shortfall and greater patient workload. Although certain actions instituted in the past have been helpful, including physician loan repayment, expansion of the national health service corps, medical school grants, and funding of rural teaching clinics, they have not done enough to address the growing needs of rural patient populations. The authors additionally suggest2:

- expansion of graduate medical education programs in rural hospitals

- higher payments for physicians in rural areas

- expanding use of mobile health vans equipped with diagnostic and treatment technology

- overcoming barriers that have slowed adoption of telehealth services.

References

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Morr M. Nurse practitioners may alleviate dwindling physician workforce in rural populations. Clinical Advisor.

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.

In addition to utilizing an NP workforce, Skinner and colleagues suggest that further strategies will be needed to address the rural physician shortfall and greater patient workload. Although certain actions instituted in the past have been helpful, including physician loan repayment, expansion of the national health service corps, medical school grants, and funding of rural teaching clinics, they have not done enough to address the growing needs of rural patient populations. The authors additionally suggest2:

- expansion of graduate medical education programs in rural hospitals

- higher payments for physicians in rural areas

- expanding use of mobile health vans equipped with diagnostic and treatment technology

- overcoming barriers that have slowed adoption of telehealth services.

References

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Morr M. Nurse practitioners may alleviate dwindling physician workforce in rural populations. Clinical Advisor.

- Doximity. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Third annual study. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round4.pdf Color/Word_R0_G0_B255 March 2019. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Women were majority of US medical school applicants in 2018. Press release, December 4, 2018. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-data-2018/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, et al. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout, depression and suicide report 2019. January 16, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape obstetrician and gynecologist lifestyle, happiness and burnout report 2019. February 20, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-obgyn-6011131Color/Word_R0_G0_B255. Accessed August 20, 2019.

- Doximity. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Third annual study. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round4.pdf Color/Word_R0_G0_B255 March 2019. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Women were majority of US medical school applicants in 2018. Press release, December 4, 2018. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-data-2018/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, et al. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout, depression and suicide report 2019. January 16, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape obstetrician and gynecologist lifestyle, happiness and burnout report 2019. February 20, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-obgyn-6011131Color/Word_R0_G0_B255. Accessed August 20, 2019.