User login

Moving toward health equity in practice

Of all the medical professions, obstetrics and gynecology should be the strongest champion for equity in women’s health in this country and globally. The question is, what does this mean in the reality of 2017 and moving forward in the 21st century? What does it mean in the context of our own practices and in the landscape of current policy and politics?

Finding answers to these questions requires both a deep understanding of the meaning of health equity and a willingness to rethink the architecture and engineering of how we currently provide care.

The terms equity and equality are sometimes used interchangeably, but they actually have quite different meanings. Imagine three women of different heights standing underneath the lowest branch of a tall apple tree. None of the three women are tall enough to pick an apple from the branch.

If we think about equality, we would assist each woman by giving her a box to stand on, and all three boxes would be the same size. This means that while the tallest woman will now be able to pick an apple, the medium-height woman may be able to touch but not pick the apple, and the shortest woman still may not be able to reach the apple at all.

However, if we think about equity, we’d acknowledge that each woman needs her own personalized box to be able to pick the apple. For instance, the shortest woman may need a box that is three times the height of the box used by the tallest woman.

Achieving true population health for all women requires that we similarly eliminate inequities by providing each patient with her own personalized care plan to help her reach and maintain her health.

Women from minority groups have higher rates of low birth weight, preterm birth, stillbirth, gestational diabetes and its complications, HIV, breast cancer mortality and cervical cancer incidence and mortality, infertility and response to fertility treatment, and maternal mortality.

Yet inequity runs deeper than racial/ethnic labels; disparities also are created by a host of other factors, from cognitive or physical disabilities to gender or sexual identity or orientation, one’s ZIP code, working environment, language, and health literacy.

More than ever, the art of medicine involves understanding how to meet every patient where she is – given her own context and beliefs and levels of support – so that every woman has the opportunity to stand on the right-sized box and pick the apple and thrive.

Our practices

Provider bias and stereotyping can impact health care and health outcomes, and it is important that we work to prevent this in ourselves and in our staff. This means not making assumptions. It means really listening to our patients in ways that we may not have before.

Women who have experienced health inequity may have unique barriers to success. Therefore, we must listen for cues and inquire about our patients’ environment and circumstances, as well as their partnerships and support – or lack thereof. We should then acknowledge and communicate that certain social and environmental factors may impact our ability to achieve a desired outcome.

How can we impact the diet of a patient with gestational diabetes, for instance, if we have not adequately communicated what medical nutritional therapy means in the context of her own culture and ability to access food? If she lives in a food desert or has food insecurity or lives in a violence-ridden neighborhood that keeps her from going to a grocery store regularly, we must think outside the box. Ob.gyns. and their clinical care teams can work with women who have less access to nutritious foods, or who have certain cultural food staples, to suggest recipes and grocery lists that make sense with respect to the types of stores they shop in or their cultural preferences.

When it comes to cancer prevention and treatment, how can we expect a woman to be compliant with screening if we cannot help her understand that she can get screening services for free with her health insurance? How can we help a woman who has coverage for, or access to, free screening but then no funding or coverage for a diagnostic test or cancer treatment? How can we support a patient with abnormal cancer screening results who hasn’t followed up for months because she is afraid to leave home without her partner’s permission?

Such questions and circumstances often involve what we call “social determinants of health,” and they force us to rethink how we can better deliver and optimize care. Re-engineering our practices for health equity may involve employing a more diverse practice staff, linking patients with community resources, modifying our practice hours to align better with working women’s schedules, or finding creative ways to discern patients’ motivating factors and then piggyback on these factors.

We may also need to modify how we approach the number of return visits that we request of women so that follow-up care aligns better with their ability to leave work or find childcare. Simply put, we should strive to set up our patients for success, not failure.

We can pointedly ask patients about the kinds of information and support they want and need. We might ask, for instance: What do you need, and how can I work with you, so that you can effectively monitor and control your glucose levels? How can I work with you to help you get onto a trajectory to stop smoking? How can I help you better understand what tests and procedures are covered under your insurance plan, or whether you qualify for free services?

Patients with lower health literacy may need teach-back methods to validate understanding, or messaging that is more focused and limited at any one time. Self-efficacy through patient-centered education and support should be our goal.

Practices and clinics may also be able to adapt elements of the National Cancer Institute’s multicenter Patient Navigation Research Program, in which community health workers or other “patient navigators” address women’s personal barriers to the timely follow-up of abnormal breast and cervical cancer screening results. Patient navigation through this program and similar projects, including programs that we’ve adapted for different racial and ethnic communities in and around Chicago, has reduced or eliminated delays in diagnostic resolution of gynecologic cancer (Cancer. 2015 Nov 15;121[22]:4025-34, Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016 Aug;158[3]:523-34, Am J Public Health. 2015 May;105[5]:e87-94).

The patient navigation model is increasingly being adapted and used in a variety of contexts outside of cancer care as well. In a postpartum patient navigation program that we tested at Northwestern University’s Medicaid-based outpatient clinic, a navigator was hired to communicate with patients and support them between delivery and completion of their postpartum care. Patients were reminded through calls and/or texts of their postpartum visits and of the benefits of breastfeeding, effective contraception, and other postpartum practices.

The demonstration project was impactful: Women who were enrolled in the program were more likely to return for postpartum care, to receive World Health Organization Tier 1 or 2 contraception, and to have postpartum screening and vaccinations, compared with women who received care before the program began (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 May;129[5]:925-33).

Connections to our patients will help us to achieve health equity. This includes connections between the primary care we provide and the specialty care our patients sometimes require, both inside and outside of our field. We may refer a patient to an oncology team, for instance, and in the process, unwittingly transfer her care such that other conditions that we’ve been managing – hypertension, depression, or diabetes – fall by the wayside.

Instead, we have to re-engineer our processes so that we maintain personalized connections back to these patients. For example, the referring ob.gyn. could develop and send to the oncologist or gynecologic-oncologist a care plan that includes the patient’s comorbid conditions and how they could be managed. This would allow for clearer communication.

Our communities

As ob.gyns., we have a common goal of championing health equity and true population health for every woman, regardless of whether she lives in rural, urban, or suburban America and regardless of whether she has conservative or liberal values. To do so, we must extend ourselves beyond our own practices.

In a committee opinion on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advises that ob.gyns. take a number of actions to increase health equity. These include raising awareness about inequity and its effects on health outcomes, promoting quality improvement projects that target disparities, working with public health leadership, and helping recruit ob.gyns. and other health care providers from racial and ethnic minority groups (Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e130-4).

In Chicago, where 1 out of 5 people lives in poverty and 1 out of 10 lives in deep poverty, we are still in our infancy in combating health inequities. However, with partnerships between academic institutions, departments of health, and other organizations across various sectors, we are beginning to move the needle on these entrenched health inequities.

For example, in 2007, there was a 60% difference in breast cancer mortality between black and white women in Chicago. This disparity sparked the development of the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force and a series of on-the-ground patient navigator programs, along with several key policy changes and new state laws.

State actions included requiring quality reporting on mammography and increasing the Medicaid reimbursement rate for mammography to the Medicare rate. Nationally, beneficial changes were made to Medicare’s quality metrics and to the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. All told, through a combination of studies and initiatives focused on improving knowledge, trust, access to care, and quality of care, we have been able to decrease the breast cancer mortality gap by 20%.

We also have a role to play in nurturing and developing a workforce that better aligns with our evolving demographics. This involves redesigning how we plant seeds of opportunity among high school students, undergraduates, and young medical students, and how we seek job applicants. Moreover, when we help people get to the next step in their careers, we need to make sure there is continuous support to retain them and help propel them to the next level.

We should think creatively to establish programs or launch initiatives that can help level the playing field for all women. For example, I created a Massive Open Online Course called “Career 911: Your Future Job in Medicine and Healthcare” as a free workforce development pipeline program. It is accessible on a global platform (https://www.coursera.org/learn/healthcarejobs) and is one example of how we as ob.gyns. can leverage our skills and resources.

Along the way, we also need to train our students and residents – and ourselves – to be more familiar with, and articulate about, health care policy. We need to understand how policy is made and modified and how we can be good communicators and thought leaders.

Right now, our ability to articulate our patients’ stories to policy makers and to the public seems underdeveloped and undertapped. The onus is on us to write and speak about how all women must have the opportunity to not only access care but to access high-quality care and preventive services that are important for full health. Providing health equity isn’t about giving someone a handout, but about giving her a helping hand to take control of her health.

Achieving health equity will involve changing our approach to research. If medical research on women’s health continues to be dominated by studies in which participants are homogeneous and from mainly white or well-resourced populations, we will never have output that is generalizable. As practicing ob.gyns., we can look for opportunities to advocate for diversity in research. We can also acknowledge that, for some women, there is historically-rooted distrust of the health care system that serves as a barrier both to obtaining care and enrolling in trials.

By meeting women where they are, and by tailoring their individual boxes as best we can – in research, in workforce development, and in clinical care delivery – we can work toward solutions.

Strategies for achieving women’s health equity

• Modify office hours/dates to allow flexibility for women who have challenges scheduling childcare and time off from work.

• Ensure handouts, educational materials, and all communications are at appropriate health literacy levels.

• Acknowledge and understand an individual woman’s barriers to care, including social determinants of health, and create a care plan that is achievable for her.

• Learn about and refer women to local community resources needed to overcome barriers to care, such as childcare, social services support, support services for intimate partner violence, and substance abuse counseling.

• Examine office processes to optimize the number of visits women have to attend for a particular health issue. Are there ways to explain results and next steps in a care plan without having to make her come back for an office visit?

Dr. Simon is the George H. Gardner Professor of Clinical Gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and director of the Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative. She is a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, but the views expressed in this piece are her own.

Of all the medical professions, obstetrics and gynecology should be the strongest champion for equity in women’s health in this country and globally. The question is, what does this mean in the reality of 2017 and moving forward in the 21st century? What does it mean in the context of our own practices and in the landscape of current policy and politics?

Finding answers to these questions requires both a deep understanding of the meaning of health equity and a willingness to rethink the architecture and engineering of how we currently provide care.

The terms equity and equality are sometimes used interchangeably, but they actually have quite different meanings. Imagine three women of different heights standing underneath the lowest branch of a tall apple tree. None of the three women are tall enough to pick an apple from the branch.

If we think about equality, we would assist each woman by giving her a box to stand on, and all three boxes would be the same size. This means that while the tallest woman will now be able to pick an apple, the medium-height woman may be able to touch but not pick the apple, and the shortest woman still may not be able to reach the apple at all.

However, if we think about equity, we’d acknowledge that each woman needs her own personalized box to be able to pick the apple. For instance, the shortest woman may need a box that is three times the height of the box used by the tallest woman.

Achieving true population health for all women requires that we similarly eliminate inequities by providing each patient with her own personalized care plan to help her reach and maintain her health.

Women from minority groups have higher rates of low birth weight, preterm birth, stillbirth, gestational diabetes and its complications, HIV, breast cancer mortality and cervical cancer incidence and mortality, infertility and response to fertility treatment, and maternal mortality.

Yet inequity runs deeper than racial/ethnic labels; disparities also are created by a host of other factors, from cognitive or physical disabilities to gender or sexual identity or orientation, one’s ZIP code, working environment, language, and health literacy.

More than ever, the art of medicine involves understanding how to meet every patient where she is – given her own context and beliefs and levels of support – so that every woman has the opportunity to stand on the right-sized box and pick the apple and thrive.

Our practices

Provider bias and stereotyping can impact health care and health outcomes, and it is important that we work to prevent this in ourselves and in our staff. This means not making assumptions. It means really listening to our patients in ways that we may not have before.

Women who have experienced health inequity may have unique barriers to success. Therefore, we must listen for cues and inquire about our patients’ environment and circumstances, as well as their partnerships and support – or lack thereof. We should then acknowledge and communicate that certain social and environmental factors may impact our ability to achieve a desired outcome.

How can we impact the diet of a patient with gestational diabetes, for instance, if we have not adequately communicated what medical nutritional therapy means in the context of her own culture and ability to access food? If she lives in a food desert or has food insecurity or lives in a violence-ridden neighborhood that keeps her from going to a grocery store regularly, we must think outside the box. Ob.gyns. and their clinical care teams can work with women who have less access to nutritious foods, or who have certain cultural food staples, to suggest recipes and grocery lists that make sense with respect to the types of stores they shop in or their cultural preferences.

When it comes to cancer prevention and treatment, how can we expect a woman to be compliant with screening if we cannot help her understand that she can get screening services for free with her health insurance? How can we help a woman who has coverage for, or access to, free screening but then no funding or coverage for a diagnostic test or cancer treatment? How can we support a patient with abnormal cancer screening results who hasn’t followed up for months because she is afraid to leave home without her partner’s permission?

Such questions and circumstances often involve what we call “social determinants of health,” and they force us to rethink how we can better deliver and optimize care. Re-engineering our practices for health equity may involve employing a more diverse practice staff, linking patients with community resources, modifying our practice hours to align better with working women’s schedules, or finding creative ways to discern patients’ motivating factors and then piggyback on these factors.

We may also need to modify how we approach the number of return visits that we request of women so that follow-up care aligns better with their ability to leave work or find childcare. Simply put, we should strive to set up our patients for success, not failure.

We can pointedly ask patients about the kinds of information and support they want and need. We might ask, for instance: What do you need, and how can I work with you, so that you can effectively monitor and control your glucose levels? How can I work with you to help you get onto a trajectory to stop smoking? How can I help you better understand what tests and procedures are covered under your insurance plan, or whether you qualify for free services?

Patients with lower health literacy may need teach-back methods to validate understanding, or messaging that is more focused and limited at any one time. Self-efficacy through patient-centered education and support should be our goal.

Practices and clinics may also be able to adapt elements of the National Cancer Institute’s multicenter Patient Navigation Research Program, in which community health workers or other “patient navigators” address women’s personal barriers to the timely follow-up of abnormal breast and cervical cancer screening results. Patient navigation through this program and similar projects, including programs that we’ve adapted for different racial and ethnic communities in and around Chicago, has reduced or eliminated delays in diagnostic resolution of gynecologic cancer (Cancer. 2015 Nov 15;121[22]:4025-34, Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016 Aug;158[3]:523-34, Am J Public Health. 2015 May;105[5]:e87-94).

The patient navigation model is increasingly being adapted and used in a variety of contexts outside of cancer care as well. In a postpartum patient navigation program that we tested at Northwestern University’s Medicaid-based outpatient clinic, a navigator was hired to communicate with patients and support them between delivery and completion of their postpartum care. Patients were reminded through calls and/or texts of their postpartum visits and of the benefits of breastfeeding, effective contraception, and other postpartum practices.

The demonstration project was impactful: Women who were enrolled in the program were more likely to return for postpartum care, to receive World Health Organization Tier 1 or 2 contraception, and to have postpartum screening and vaccinations, compared with women who received care before the program began (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 May;129[5]:925-33).

Connections to our patients will help us to achieve health equity. This includes connections between the primary care we provide and the specialty care our patients sometimes require, both inside and outside of our field. We may refer a patient to an oncology team, for instance, and in the process, unwittingly transfer her care such that other conditions that we’ve been managing – hypertension, depression, or diabetes – fall by the wayside.

Instead, we have to re-engineer our processes so that we maintain personalized connections back to these patients. For example, the referring ob.gyn. could develop and send to the oncologist or gynecologic-oncologist a care plan that includes the patient’s comorbid conditions and how they could be managed. This would allow for clearer communication.

Our communities

As ob.gyns., we have a common goal of championing health equity and true population health for every woman, regardless of whether she lives in rural, urban, or suburban America and regardless of whether she has conservative or liberal values. To do so, we must extend ourselves beyond our own practices.

In a committee opinion on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advises that ob.gyns. take a number of actions to increase health equity. These include raising awareness about inequity and its effects on health outcomes, promoting quality improvement projects that target disparities, working with public health leadership, and helping recruit ob.gyns. and other health care providers from racial and ethnic minority groups (Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e130-4).

In Chicago, where 1 out of 5 people lives in poverty and 1 out of 10 lives in deep poverty, we are still in our infancy in combating health inequities. However, with partnerships between academic institutions, departments of health, and other organizations across various sectors, we are beginning to move the needle on these entrenched health inequities.

For example, in 2007, there was a 60% difference in breast cancer mortality between black and white women in Chicago. This disparity sparked the development of the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force and a series of on-the-ground patient navigator programs, along with several key policy changes and new state laws.

State actions included requiring quality reporting on mammography and increasing the Medicaid reimbursement rate for mammography to the Medicare rate. Nationally, beneficial changes were made to Medicare’s quality metrics and to the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. All told, through a combination of studies and initiatives focused on improving knowledge, trust, access to care, and quality of care, we have been able to decrease the breast cancer mortality gap by 20%.

We also have a role to play in nurturing and developing a workforce that better aligns with our evolving demographics. This involves redesigning how we plant seeds of opportunity among high school students, undergraduates, and young medical students, and how we seek job applicants. Moreover, when we help people get to the next step in their careers, we need to make sure there is continuous support to retain them and help propel them to the next level.

We should think creatively to establish programs or launch initiatives that can help level the playing field for all women. For example, I created a Massive Open Online Course called “Career 911: Your Future Job in Medicine and Healthcare” as a free workforce development pipeline program. It is accessible on a global platform (https://www.coursera.org/learn/healthcarejobs) and is one example of how we as ob.gyns. can leverage our skills and resources.

Along the way, we also need to train our students and residents – and ourselves – to be more familiar with, and articulate about, health care policy. We need to understand how policy is made and modified and how we can be good communicators and thought leaders.

Right now, our ability to articulate our patients’ stories to policy makers and to the public seems underdeveloped and undertapped. The onus is on us to write and speak about how all women must have the opportunity to not only access care but to access high-quality care and preventive services that are important for full health. Providing health equity isn’t about giving someone a handout, but about giving her a helping hand to take control of her health.

Achieving health equity will involve changing our approach to research. If medical research on women’s health continues to be dominated by studies in which participants are homogeneous and from mainly white or well-resourced populations, we will never have output that is generalizable. As practicing ob.gyns., we can look for opportunities to advocate for diversity in research. We can also acknowledge that, for some women, there is historically-rooted distrust of the health care system that serves as a barrier both to obtaining care and enrolling in trials.

By meeting women where they are, and by tailoring their individual boxes as best we can – in research, in workforce development, and in clinical care delivery – we can work toward solutions.

Strategies for achieving women’s health equity

• Modify office hours/dates to allow flexibility for women who have challenges scheduling childcare and time off from work.

• Ensure handouts, educational materials, and all communications are at appropriate health literacy levels.

• Acknowledge and understand an individual woman’s barriers to care, including social determinants of health, and create a care plan that is achievable for her.

• Learn about and refer women to local community resources needed to overcome barriers to care, such as childcare, social services support, support services for intimate partner violence, and substance abuse counseling.

• Examine office processes to optimize the number of visits women have to attend for a particular health issue. Are there ways to explain results and next steps in a care plan without having to make her come back for an office visit?

Dr. Simon is the George H. Gardner Professor of Clinical Gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and director of the Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative. She is a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, but the views expressed in this piece are her own.

Of all the medical professions, obstetrics and gynecology should be the strongest champion for equity in women’s health in this country and globally. The question is, what does this mean in the reality of 2017 and moving forward in the 21st century? What does it mean in the context of our own practices and in the landscape of current policy and politics?

Finding answers to these questions requires both a deep understanding of the meaning of health equity and a willingness to rethink the architecture and engineering of how we currently provide care.

The terms equity and equality are sometimes used interchangeably, but they actually have quite different meanings. Imagine three women of different heights standing underneath the lowest branch of a tall apple tree. None of the three women are tall enough to pick an apple from the branch.

If we think about equality, we would assist each woman by giving her a box to stand on, and all three boxes would be the same size. This means that while the tallest woman will now be able to pick an apple, the medium-height woman may be able to touch but not pick the apple, and the shortest woman still may not be able to reach the apple at all.

However, if we think about equity, we’d acknowledge that each woman needs her own personalized box to be able to pick the apple. For instance, the shortest woman may need a box that is three times the height of the box used by the tallest woman.

Achieving true population health for all women requires that we similarly eliminate inequities by providing each patient with her own personalized care plan to help her reach and maintain her health.

Women from minority groups have higher rates of low birth weight, preterm birth, stillbirth, gestational diabetes and its complications, HIV, breast cancer mortality and cervical cancer incidence and mortality, infertility and response to fertility treatment, and maternal mortality.

Yet inequity runs deeper than racial/ethnic labels; disparities also are created by a host of other factors, from cognitive or physical disabilities to gender or sexual identity or orientation, one’s ZIP code, working environment, language, and health literacy.

More than ever, the art of medicine involves understanding how to meet every patient where she is – given her own context and beliefs and levels of support – so that every woman has the opportunity to stand on the right-sized box and pick the apple and thrive.

Our practices

Provider bias and stereotyping can impact health care and health outcomes, and it is important that we work to prevent this in ourselves and in our staff. This means not making assumptions. It means really listening to our patients in ways that we may not have before.

Women who have experienced health inequity may have unique barriers to success. Therefore, we must listen for cues and inquire about our patients’ environment and circumstances, as well as their partnerships and support – or lack thereof. We should then acknowledge and communicate that certain social and environmental factors may impact our ability to achieve a desired outcome.

How can we impact the diet of a patient with gestational diabetes, for instance, if we have not adequately communicated what medical nutritional therapy means in the context of her own culture and ability to access food? If she lives in a food desert or has food insecurity or lives in a violence-ridden neighborhood that keeps her from going to a grocery store regularly, we must think outside the box. Ob.gyns. and their clinical care teams can work with women who have less access to nutritious foods, or who have certain cultural food staples, to suggest recipes and grocery lists that make sense with respect to the types of stores they shop in or their cultural preferences.

When it comes to cancer prevention and treatment, how can we expect a woman to be compliant with screening if we cannot help her understand that she can get screening services for free with her health insurance? How can we help a woman who has coverage for, or access to, free screening but then no funding or coverage for a diagnostic test or cancer treatment? How can we support a patient with abnormal cancer screening results who hasn’t followed up for months because she is afraid to leave home without her partner’s permission?

Such questions and circumstances often involve what we call “social determinants of health,” and they force us to rethink how we can better deliver and optimize care. Re-engineering our practices for health equity may involve employing a more diverse practice staff, linking patients with community resources, modifying our practice hours to align better with working women’s schedules, or finding creative ways to discern patients’ motivating factors and then piggyback on these factors.

We may also need to modify how we approach the number of return visits that we request of women so that follow-up care aligns better with their ability to leave work or find childcare. Simply put, we should strive to set up our patients for success, not failure.

We can pointedly ask patients about the kinds of information and support they want and need. We might ask, for instance: What do you need, and how can I work with you, so that you can effectively monitor and control your glucose levels? How can I work with you to help you get onto a trajectory to stop smoking? How can I help you better understand what tests and procedures are covered under your insurance plan, or whether you qualify for free services?

Patients with lower health literacy may need teach-back methods to validate understanding, or messaging that is more focused and limited at any one time. Self-efficacy through patient-centered education and support should be our goal.

Practices and clinics may also be able to adapt elements of the National Cancer Institute’s multicenter Patient Navigation Research Program, in which community health workers or other “patient navigators” address women’s personal barriers to the timely follow-up of abnormal breast and cervical cancer screening results. Patient navigation through this program and similar projects, including programs that we’ve adapted for different racial and ethnic communities in and around Chicago, has reduced or eliminated delays in diagnostic resolution of gynecologic cancer (Cancer. 2015 Nov 15;121[22]:4025-34, Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016 Aug;158[3]:523-34, Am J Public Health. 2015 May;105[5]:e87-94).

The patient navigation model is increasingly being adapted and used in a variety of contexts outside of cancer care as well. In a postpartum patient navigation program that we tested at Northwestern University’s Medicaid-based outpatient clinic, a navigator was hired to communicate with patients and support them between delivery and completion of their postpartum care. Patients were reminded through calls and/or texts of their postpartum visits and of the benefits of breastfeeding, effective contraception, and other postpartum practices.

The demonstration project was impactful: Women who were enrolled in the program were more likely to return for postpartum care, to receive World Health Organization Tier 1 or 2 contraception, and to have postpartum screening and vaccinations, compared with women who received care before the program began (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 May;129[5]:925-33).

Connections to our patients will help us to achieve health equity. This includes connections between the primary care we provide and the specialty care our patients sometimes require, both inside and outside of our field. We may refer a patient to an oncology team, for instance, and in the process, unwittingly transfer her care such that other conditions that we’ve been managing – hypertension, depression, or diabetes – fall by the wayside.

Instead, we have to re-engineer our processes so that we maintain personalized connections back to these patients. For example, the referring ob.gyn. could develop and send to the oncologist or gynecologic-oncologist a care plan that includes the patient’s comorbid conditions and how they could be managed. This would allow for clearer communication.

Our communities

As ob.gyns., we have a common goal of championing health equity and true population health for every woman, regardless of whether she lives in rural, urban, or suburban America and regardless of whether she has conservative or liberal values. To do so, we must extend ourselves beyond our own practices.

In a committee opinion on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advises that ob.gyns. take a number of actions to increase health equity. These include raising awareness about inequity and its effects on health outcomes, promoting quality improvement projects that target disparities, working with public health leadership, and helping recruit ob.gyns. and other health care providers from racial and ethnic minority groups (Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e130-4).

In Chicago, where 1 out of 5 people lives in poverty and 1 out of 10 lives in deep poverty, we are still in our infancy in combating health inequities. However, with partnerships between academic institutions, departments of health, and other organizations across various sectors, we are beginning to move the needle on these entrenched health inequities.

For example, in 2007, there was a 60% difference in breast cancer mortality between black and white women in Chicago. This disparity sparked the development of the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force and a series of on-the-ground patient navigator programs, along with several key policy changes and new state laws.

State actions included requiring quality reporting on mammography and increasing the Medicaid reimbursement rate for mammography to the Medicare rate. Nationally, beneficial changes were made to Medicare’s quality metrics and to the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. All told, through a combination of studies and initiatives focused on improving knowledge, trust, access to care, and quality of care, we have been able to decrease the breast cancer mortality gap by 20%.

We also have a role to play in nurturing and developing a workforce that better aligns with our evolving demographics. This involves redesigning how we plant seeds of opportunity among high school students, undergraduates, and young medical students, and how we seek job applicants. Moreover, when we help people get to the next step in their careers, we need to make sure there is continuous support to retain them and help propel them to the next level.

We should think creatively to establish programs or launch initiatives that can help level the playing field for all women. For example, I created a Massive Open Online Course called “Career 911: Your Future Job in Medicine and Healthcare” as a free workforce development pipeline program. It is accessible on a global platform (https://www.coursera.org/learn/healthcarejobs) and is one example of how we as ob.gyns. can leverage our skills and resources.

Along the way, we also need to train our students and residents – and ourselves – to be more familiar with, and articulate about, health care policy. We need to understand how policy is made and modified and how we can be good communicators and thought leaders.

Right now, our ability to articulate our patients’ stories to policy makers and to the public seems underdeveloped and undertapped. The onus is on us to write and speak about how all women must have the opportunity to not only access care but to access high-quality care and preventive services that are important for full health. Providing health equity isn’t about giving someone a handout, but about giving her a helping hand to take control of her health.

Achieving health equity will involve changing our approach to research. If medical research on women’s health continues to be dominated by studies in which participants are homogeneous and from mainly white or well-resourced populations, we will never have output that is generalizable. As practicing ob.gyns., we can look for opportunities to advocate for diversity in research. We can also acknowledge that, for some women, there is historically-rooted distrust of the health care system that serves as a barrier both to obtaining care and enrolling in trials.

By meeting women where they are, and by tailoring their individual boxes as best we can – in research, in workforce development, and in clinical care delivery – we can work toward solutions.

Strategies for achieving women’s health equity

• Modify office hours/dates to allow flexibility for women who have challenges scheduling childcare and time off from work.

• Ensure handouts, educational materials, and all communications are at appropriate health literacy levels.

• Acknowledge and understand an individual woman’s barriers to care, including social determinants of health, and create a care plan that is achievable for her.

• Learn about and refer women to local community resources needed to overcome barriers to care, such as childcare, social services support, support services for intimate partner violence, and substance abuse counseling.

• Examine office processes to optimize the number of visits women have to attend for a particular health issue. Are there ways to explain results and next steps in a care plan without having to make her come back for an office visit?

Dr. Simon is the George H. Gardner Professor of Clinical Gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and director of the Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative. She is a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, but the views expressed in this piece are her own.

Demystifying interstitial cystitis

Chronic pelvic pain continues not only to burden the individual, but society as well.

One in seven women between the ages of 18 and 50 endure chronic pelvic pain; with a lifetime incidence of as high as 33%, according to one Gallup poll. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) has been estimated to have a prevalence of 850 in 100,000 women and 60 in 100,000 men in self-report studies. The RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) study, a symptoms survey, showed that between 2.7% and 6.5% of women (3.3 to 7.9 million women) in the United States have symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of IC/BPS.

Unfortunately, there is little known about the etiology and pathogenesis of IC/PBS. Moreover, oftentimes, the diagnosis is one of exclusion.

To demystify interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Kenneth Peters, a urologist on staff at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Mich. Dr. Peters is the professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University, William Beaumont School of Medicine, and the chairman of urology at Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Mich.

In his discussion, Dr. Peters will point out that interstitial cystitis actually consists of two different entities: a classic presentation featuring the pathognomonic Hunner’s lesion on cystoscopy and interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome.

It must be acknowledged that Dr. Peters is a practicing urologist. Therefore, some of his recommendations, such as cauterizing Hunner’s lesions via a resectoscope, are beyond the scope of practicing gynecologists. However, it is important for us to realize what our potential referrals possess in their armamentarium. Moreover, it is obvious there is much that can be learned from this excellent diagnostician who professes the importance of physical examination.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He is an investigator on an interstitial cystitis study sponsored by Allergan.

Chronic pelvic pain continues not only to burden the individual, but society as well.

One in seven women between the ages of 18 and 50 endure chronic pelvic pain; with a lifetime incidence of as high as 33%, according to one Gallup poll. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) has been estimated to have a prevalence of 850 in 100,000 women and 60 in 100,000 men in self-report studies. The RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) study, a symptoms survey, showed that between 2.7% and 6.5% of women (3.3 to 7.9 million women) in the United States have symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of IC/BPS.

Unfortunately, there is little known about the etiology and pathogenesis of IC/PBS. Moreover, oftentimes, the diagnosis is one of exclusion.

To demystify interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Kenneth Peters, a urologist on staff at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Mich. Dr. Peters is the professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University, William Beaumont School of Medicine, and the chairman of urology at Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Mich.

In his discussion, Dr. Peters will point out that interstitial cystitis actually consists of two different entities: a classic presentation featuring the pathognomonic Hunner’s lesion on cystoscopy and interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome.

It must be acknowledged that Dr. Peters is a practicing urologist. Therefore, some of his recommendations, such as cauterizing Hunner’s lesions via a resectoscope, are beyond the scope of practicing gynecologists. However, it is important for us to realize what our potential referrals possess in their armamentarium. Moreover, it is obvious there is much that can be learned from this excellent diagnostician who professes the importance of physical examination.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He is an investigator on an interstitial cystitis study sponsored by Allergan.

Chronic pelvic pain continues not only to burden the individual, but society as well.

One in seven women between the ages of 18 and 50 endure chronic pelvic pain; with a lifetime incidence of as high as 33%, according to one Gallup poll. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) has been estimated to have a prevalence of 850 in 100,000 women and 60 in 100,000 men in self-report studies. The RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) study, a symptoms survey, showed that between 2.7% and 6.5% of women (3.3 to 7.9 million women) in the United States have symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of IC/BPS.

Unfortunately, there is little known about the etiology and pathogenesis of IC/PBS. Moreover, oftentimes, the diagnosis is one of exclusion.

To demystify interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome, I have elicited the assistance of Dr. Kenneth Peters, a urologist on staff at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Mich. Dr. Peters is the professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University, William Beaumont School of Medicine, and the chairman of urology at Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Mich.

In his discussion, Dr. Peters will point out that interstitial cystitis actually consists of two different entities: a classic presentation featuring the pathognomonic Hunner’s lesion on cystoscopy and interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome.

It must be acknowledged that Dr. Peters is a practicing urologist. Therefore, some of his recommendations, such as cauterizing Hunner’s lesions via a resectoscope, are beyond the scope of practicing gynecologists. However, it is important for us to realize what our potential referrals possess in their armamentarium. Moreover, it is obvious there is much that can be learned from this excellent diagnostician who professes the importance of physical examination.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. He is an investigator on an interstitial cystitis study sponsored by Allergan.

The broad picture of interstitial cystitis

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a controversial diagnosis that has become muddied and oversimplified. It was originally described as a distinct ulcer (Hunner’s lesion) seen in the bladder on cystoscopy, the treatment of which often led to symptomatic relief. Hunner’s lesion IC is the “classic” form of IC and should be considered a separate disease; it is not a progression of nonulcerative interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/BPS).

Only a fraction of patients with the key symptoms of IC/BPS – urinary frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – have ulcers within the bladder. And many of the patients who are diagnosed with IC/BPS are found not to have bladder pathology as the name implies, but rather pelvic floor dysfunction. That the bladder is often an innocent bystander to a larger process means that, as clinicians, we must be thoughtful and astute about our diagnostic process.

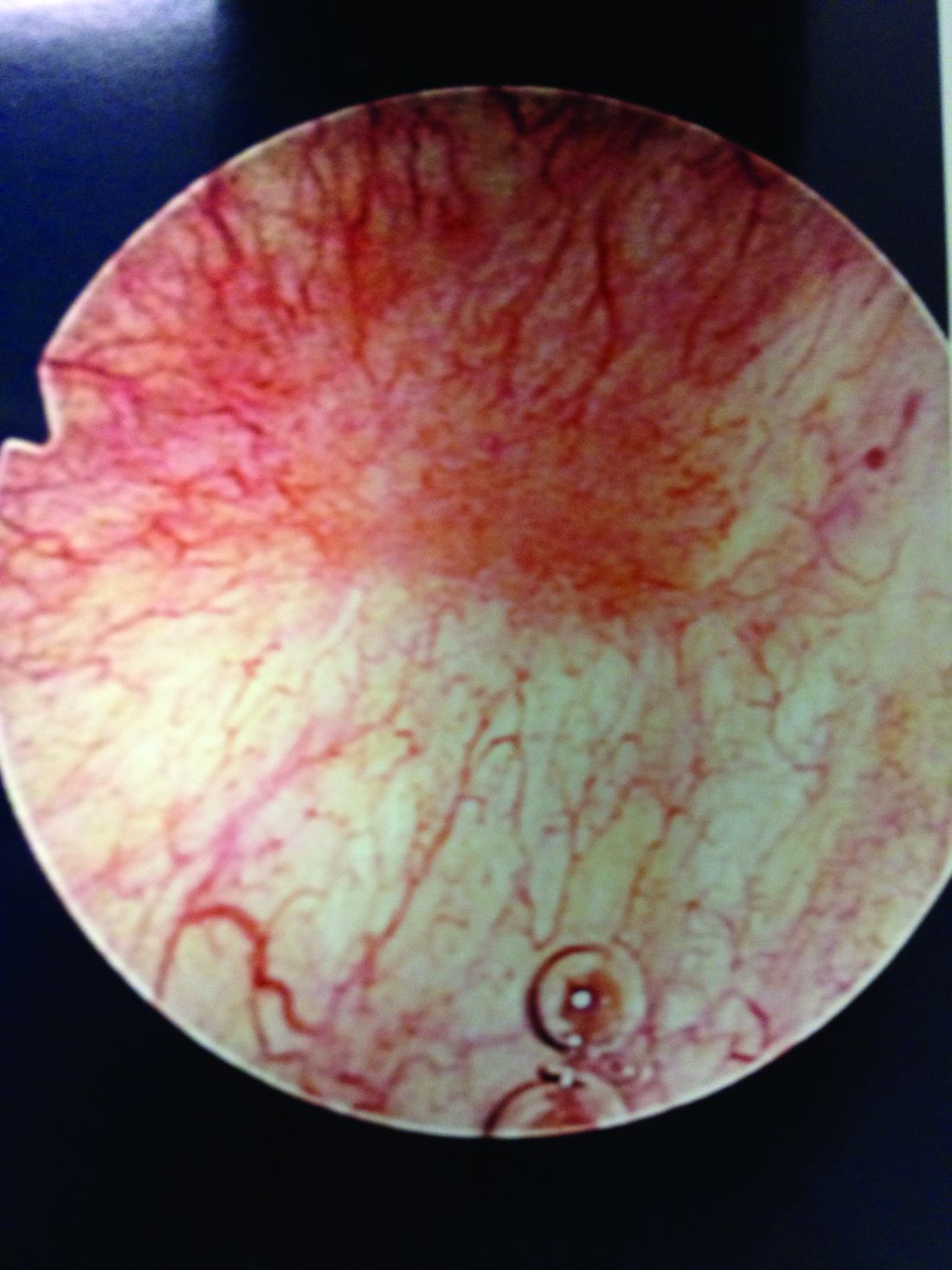

Hunner’s lesions

Patients with Hunner’s lesions have a rapid onset of symptoms, typically are older, and have a visible lesion in their bladder that almost always is on the dome or lateral walls. The lesion is often erythematous with central vascularity and mucosal sloughing.

The bladder is a storage organ and urine is toxic. The exposed ulcer results in severe pain with bladder filling and also pain at the end of voiding as the bladder collapses, causing ulcerated tissue to come into contact with other sections of the bladder wall and sending a “jolt” of pain through the pelvis.

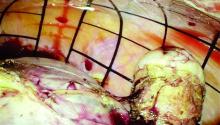

If the initial cystoscopy demonstrates inflammatory-appearing lesions or ulcerations suggestive of Hunner’s lesions, I will still do a hydrodistension. By stretching the bladder, the lesions typically expand, crack, and bleed. This helps define the entire diseased area and shows what areas of the bladder need to be cauterized to seal the ulcers and destroy the exposed nerve endings. If this is a new diagnosis, the lesion should be biopsied after the hydrodistension to rule out carcinoma.

Hunner’s lesions can lead to rapid disease progression due to chronic inflammation and subsequent collagen deposition and scarring. Even on initial diagnosis of Hunner’s lesions, a capacity of 350 cc or less (compared with 1,100 cc in a normal bladder) on hydrodistension under anesthesia is not uncommon. This markedly reduced bladder capacity may lead to end-stage bladder impacting the kidneys and requiring a urinary diversion.

Eradicating the ulcers with resection or cautery often results in marked and immediate improvement in bladder pain, albeit not long-lasting. I will typically place a resectoscope and use a roller ball at 25 watts of current. The entire ulcerated areas are cauterized by rapidly rolling the ball over the area of inflammation and avoiding a deep thermal burn. The goal is to seal the ulcer and destroy the exposed nerve endings so that urine can no longer act as an irritant. Recurrence in 6 months to 1 year is common and retreatment is almost always necessary. We have demonstrated, however, that recurrent cautery of ulcers does not lead to smaller anesthetic bladder capacities (Urology. 2015 Jan;85[1]:74-8).

Low-dose cyclosporine can be very effective at reducing Hunner’s lesion recurrence and improving storage symptoms (Exp Ther Med. 2016 Jul;12[1]:445-50). I use 100 mg twice a day for a month and then 1 pill a day thereafter. This is a relatively low dose, but hypertension can be a side effect and blood pressure should be monitored along with routine labs.

The broader picture

Hunner’s lesion IC is pretty straightforward and clearly a bladder disease. However, in recent years the term IC/BPS has been broadly used to describe women who have symptoms of pelvic pain, urinary urgency, and frequency, but no true bladder pathology to explain their symptoms. One problem: There is no definitive diagnostic test or evidence-based diagnostic process for IC/BPS. In fact, the diagnosis section of the American Urological Association guideline on diagnosis and treatment of IC/BPS, last updated in 2015, is almost entirely consensus-based (J Urol. 2015 May;193[5]:1545-53). It largely remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

As the AUA guidelines state, a careful history, physical examination, and laboratory assessment are all important for documenting symptoms and signs and ruling out significant causes of the symptoms. I frequently see patients who have been diagnosed with IC who have frequency and urgency but no pain (in which case overactive bladder should be considered) or who have pelvic pain but no bladder symptoms, again likely not IC. Pain that worsens with bladder filling and improves after bladder emptying is typical of IC/BPS. This finding in the absence of other confusing symptoms supports the diagnosis of IC/BPS.

It has become too easy for the average clinician to apply a label of IC/BPS to a patient complaining of pelvic pain; this often results in the patient undergoing invasive and nonhelpful therapies such as cystoscopy, hydrodistension, urodynamics, bladder instillations, and other bladder-directed therapies.

More than 20 years of research supported by the National Institutes of Health and industry have failed to show that bladder-directed therapy is superior to placebo. This fact suggests that the bladder may be an innocent bystander in a larger pelvic process. As clinicians, we must be willing to look beyond the bladder and examine for pelvic floor issues and other causes of patient’s symptoms and not be too quick to begin bladder-focused treatments.

A number of disease processes – such as recurrent urinary tract infection, urethral diverticulum, endometriosis, and pudendal neuropathy – can mimic the symptoms of IC/BPS. The most common missed diagnosis in the IC patient is pelvic floor dysfunction that results in a hypertonic contracted state of the levator muscles – a chronic spasm, in essence – that in turn leads to decreased muscle function, increased myofascial pain, and myofascial trigger points (Curr Urol Rep. 2006 Nov;7[6]:450-5).

We and others have reported that up to 85% of patients labeled with IC/BPS have been found on examination to have pelvic floor dysfunction or a diffuse pelvic floor hypersensitivity. The pelvic floor is important in maintaining healthy bladder, bowel, and sexual function. If the pelvic floor is in spasm, this can result in urinary frequency, hesitancy, and pelvic pain.

Many of these patients with contracted pelvic floor muscles report pain with sexual intercourse – often so severe as to cause abstention. In fact, when patients answer no to the question of whether they have pain with intercourse, I know it is unlikely that they have significant pelvic floor dysfunction. This is a key question for history taking.

Other key questions concern the impact of stress on symptoms and a history of any type of abuse. In a study we conducted about 10 years ago, we found that among 76 women who were diagnosed with IC and subsequently evaluated in our clinic, almost half (49%) reported abuse (emotional, physical, and/or sexual). The vast majority (85%) had levator pain (J Urol. 2007 Sep;178[3 Pt 1]:891-5).

Other types of stress – from past surgeries to traumatic life events – may similarly serve as triggers or precursors to pelvic floor dysfunction in some women. I often tell patients that people put stress in different areas of their bodies. While some get tension headaches or low-back aches, others get pelvic pain from contracting and guarding the levator muscles.

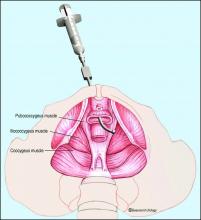

Pelvic floor dysfunction

The most important component of the physical exam in patients with the symptoms of frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – and the most overlooked – is assessment of the levator muscles for tightness and tenderness. Levator pain and trigger points may be identified during the pelvic exam by pressing laterally on the levator complex in each quadrant of the vagina and at the ischial spines. The tension of the muscles and severity of pain should be assessed, and it is helpful to ask the patient if the pain reproduces her normal pelvic pain symptoms.

We’ve found that identifying and treating pelvic floor dysfunction with modalities such as pelvic floor physical therapy with intravaginal myofascial release, intravaginal valium, trigger point injections into the levator complex, pudendal nerve blocks, and neuromodulation can frequently resolve or significantly lessen the patient’s pain and bladder symptoms, suggesting that the diagnosis of IC/BPS was wrong.

Pelvic floor physical therapy works to stretch the contracted anterior pelvic muscles by releasing trigger points and connective tissue restrictions, and by decreasing periurethral tension; it also may decrease neurogenic triggers and central nervous system sensitivity. Kegel exercises will worsen pain in these patients and should be avoided.

When pelvic floor dysfunction is identified, such treatment by a therapist knowledgeable in intravaginal myofascial release is a next reasonable step before any medications or invasive testing, such as bladder hydrodistension, are used.

One of the only National Institutes of Health–funded studies to show benefit of a treatment in an IC population, in fact, was a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing 10 sessions of myofascial pelvic floor physical therapy with “global therapeutic massage.” Myofascial physical therapy led to significant improvement, compared with the generalized spa-like massage (J Urol. 2012 Jun;187[6]:2113-8).

Our patients with IC/BPS symptoms and pelvic floor dysfunction require 1-2 visits weekly for an average of 12 weeks for tightness and tenderness to be significantly minimized or eliminated. Patients are also prescribed home stretching exercises and advised to use internal vaginal dilators. Most patients will report resolution of their pelvic pain, sexual pain, and bladder symptoms – especially with the combination of physical therapy and trigger point injections. In more severe cases, we may use sacral or pudendal neuromodulation to improve the frequency, urgency and pelvic pain.

Turning to the bladder

When urinary symptoms persist after the completion of pelvic floor therapy, or when pelvic floor dysfunction is not identified in the first place, we proceed with bladder-specific therapies. I will often suggest trials of amitriptyline or hydroxyzine, for instance, and/or changes in hydration and caffeine consumption. I am not a fan of pentosan polysulfate sodium (Elmiron) as it is a very expensive medication that has minimal benefit for the majority of patients.

When conservative therapies do not work, I move to cystoscopy with hydrodistension. The procedure can serve several purposes. It can be diagnostic, enabling us to rule out other potential symptom-causing pathologies, and it can be prognostic, helping us to understand when bladder capacity is severely reduced and to plan treatment. In some patients, it can even be therapeutic. Some of my patients have significant relief of symptoms from a hydrodistension of the bladder once or twice a year.

There is no standard method for performing a hydrodistension. I perform a complete cystoscopy to look for tumors, stones, diverticulum or Hunner’s lesions and, if the bladder is normal in appearance, I proceed with a 2-minute hydrodistension at 80-100 cm of water pressure under anesthesia. The bag is raised above the bladder, allowing the bladder to fill with the force of gravity and the pressures to equalize. The urethra must be compressed so that water doesn’t leak around the cystoscope. After 2 minutes of hydrodistension, the bladder is drained, volume is measured, and the procedure is repeated.

After the hydrodistension, the bladder is reinspected to be certain there is no bladder perforation and to evaluate for diffuse glomerulations (petechial hemorrhages) that are suggestive, but not diagnostic, of IC/BPS.

A holistic approach

Managing patients with voiding dysfunction and chronic pelvic pain can be a challenge, and a multidisciplinary approach is most effective. At Beaumont, we have a Women’s Urology Center that includes urologists, gynecologists, nurse practitioners, pelvic floor physical therapists, pain psychologists, colorectal specialists, sex therapists, and naturopathic and integrative medicine specialists who perform acupuncture, Reiki therapy, medical massage, and guided imagery.

The goal is to break out of our box of specialties and look at the whole patient – mind, body, and soul – while identifying pain triggers and directing therapy toward these triggers using a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach. For us, this approach has been very effective for managing complex pelvic pain issues (Transl Androl Urol. 2015 Dec;4[6]:611-9).

Ongoing studies

A number of research studies are ongoing to help treat the symptoms of IC/BPS. We currently have a Department of Defense grant to prospectively assess bladder-directed therapy (instillations) compared to pelvic floor physical therapy. Patients diagnosed with IC/BPS are being randomized into these two treatment arms and we hope to get a better understanding of the role of these modalities in managing IC/BPS.

Allergan is completing a phase II placebo-controlled trial using a lidocaine delivery device that is placed in the bladder and continuously releases lidocaine over 14 days. The LiNKA trial is designed to assess the impact of lidocaine on not only improving bladder symptoms, but also eradicating Hunner’s lesions through the anti-inflammatory effect of lidocaine. Early open-label data were very promising. In addition, a new medication for IC/BPS that modulates the SHIP1 pathway is being studied by Aquinox Pharmaceuticals. The agent, AQX-1125, is an activator of SHIP1, which controls the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) cellular signaling pathway. If the PI3K pathway is overactive, immune cells can produce an abundance of proinflammatory signaling molecules and migrate to and concentrate in tissues, resulting in excessive or chronic inflammation. Early data in IC/BPS patients were supportive of the compound’s potential for reducing the pain associated with this condition.

A note from Charles E. Miller, MD, Master Class Medical Editor:

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study by J.C. Nickel, et al., pentosan polysulfate sodium was shown to improve pain, urgency, and frequency over the control group (Urology. 2005 Apr;65[4]:654-8). Also, longer duration of treatment with pentosan polysulfate sodium was associated with greater response rates – 50% improved by 26 weeks (J Urol. 2005 Dec;174[6]:2235-8).

Dr. Peters is professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Royal Oak, Mich. He reported serving as a consultant for Taris, Medtronic, StimGuard, and Amphora Medical.

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a controversial diagnosis that has become muddied and oversimplified. It was originally described as a distinct ulcer (Hunner’s lesion) seen in the bladder on cystoscopy, the treatment of which often led to symptomatic relief. Hunner’s lesion IC is the “classic” form of IC and should be considered a separate disease; it is not a progression of nonulcerative interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/BPS).

Only a fraction of patients with the key symptoms of IC/BPS – urinary frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – have ulcers within the bladder. And many of the patients who are diagnosed with IC/BPS are found not to have bladder pathology as the name implies, but rather pelvic floor dysfunction. That the bladder is often an innocent bystander to a larger process means that, as clinicians, we must be thoughtful and astute about our diagnostic process.

Hunner’s lesions

Patients with Hunner’s lesions have a rapid onset of symptoms, typically are older, and have a visible lesion in their bladder that almost always is on the dome or lateral walls. The lesion is often erythematous with central vascularity and mucosal sloughing.

The bladder is a storage organ and urine is toxic. The exposed ulcer results in severe pain with bladder filling and also pain at the end of voiding as the bladder collapses, causing ulcerated tissue to come into contact with other sections of the bladder wall and sending a “jolt” of pain through the pelvis.

If the initial cystoscopy demonstrates inflammatory-appearing lesions or ulcerations suggestive of Hunner’s lesions, I will still do a hydrodistension. By stretching the bladder, the lesions typically expand, crack, and bleed. This helps define the entire diseased area and shows what areas of the bladder need to be cauterized to seal the ulcers and destroy the exposed nerve endings. If this is a new diagnosis, the lesion should be biopsied after the hydrodistension to rule out carcinoma.

Hunner’s lesions can lead to rapid disease progression due to chronic inflammation and subsequent collagen deposition and scarring. Even on initial diagnosis of Hunner’s lesions, a capacity of 350 cc or less (compared with 1,100 cc in a normal bladder) on hydrodistension under anesthesia is not uncommon. This markedly reduced bladder capacity may lead to end-stage bladder impacting the kidneys and requiring a urinary diversion.

Eradicating the ulcers with resection or cautery often results in marked and immediate improvement in bladder pain, albeit not long-lasting. I will typically place a resectoscope and use a roller ball at 25 watts of current. The entire ulcerated areas are cauterized by rapidly rolling the ball over the area of inflammation and avoiding a deep thermal burn. The goal is to seal the ulcer and destroy the exposed nerve endings so that urine can no longer act as an irritant. Recurrence in 6 months to 1 year is common and retreatment is almost always necessary. We have demonstrated, however, that recurrent cautery of ulcers does not lead to smaller anesthetic bladder capacities (Urology. 2015 Jan;85[1]:74-8).

Low-dose cyclosporine can be very effective at reducing Hunner’s lesion recurrence and improving storage symptoms (Exp Ther Med. 2016 Jul;12[1]:445-50). I use 100 mg twice a day for a month and then 1 pill a day thereafter. This is a relatively low dose, but hypertension can be a side effect and blood pressure should be monitored along with routine labs.

The broader picture

Hunner’s lesion IC is pretty straightforward and clearly a bladder disease. However, in recent years the term IC/BPS has been broadly used to describe women who have symptoms of pelvic pain, urinary urgency, and frequency, but no true bladder pathology to explain their symptoms. One problem: There is no definitive diagnostic test or evidence-based diagnostic process for IC/BPS. In fact, the diagnosis section of the American Urological Association guideline on diagnosis and treatment of IC/BPS, last updated in 2015, is almost entirely consensus-based (J Urol. 2015 May;193[5]:1545-53). It largely remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

As the AUA guidelines state, a careful history, physical examination, and laboratory assessment are all important for documenting symptoms and signs and ruling out significant causes of the symptoms. I frequently see patients who have been diagnosed with IC who have frequency and urgency but no pain (in which case overactive bladder should be considered) or who have pelvic pain but no bladder symptoms, again likely not IC. Pain that worsens with bladder filling and improves after bladder emptying is typical of IC/BPS. This finding in the absence of other confusing symptoms supports the diagnosis of IC/BPS.

It has become too easy for the average clinician to apply a label of IC/BPS to a patient complaining of pelvic pain; this often results in the patient undergoing invasive and nonhelpful therapies such as cystoscopy, hydrodistension, urodynamics, bladder instillations, and other bladder-directed therapies.

More than 20 years of research supported by the National Institutes of Health and industry have failed to show that bladder-directed therapy is superior to placebo. This fact suggests that the bladder may be an innocent bystander in a larger pelvic process. As clinicians, we must be willing to look beyond the bladder and examine for pelvic floor issues and other causes of patient’s symptoms and not be too quick to begin bladder-focused treatments.

A number of disease processes – such as recurrent urinary tract infection, urethral diverticulum, endometriosis, and pudendal neuropathy – can mimic the symptoms of IC/BPS. The most common missed diagnosis in the IC patient is pelvic floor dysfunction that results in a hypertonic contracted state of the levator muscles – a chronic spasm, in essence – that in turn leads to decreased muscle function, increased myofascial pain, and myofascial trigger points (Curr Urol Rep. 2006 Nov;7[6]:450-5).

We and others have reported that up to 85% of patients labeled with IC/BPS have been found on examination to have pelvic floor dysfunction or a diffuse pelvic floor hypersensitivity. The pelvic floor is important in maintaining healthy bladder, bowel, and sexual function. If the pelvic floor is in spasm, this can result in urinary frequency, hesitancy, and pelvic pain.

Many of these patients with contracted pelvic floor muscles report pain with sexual intercourse – often so severe as to cause abstention. In fact, when patients answer no to the question of whether they have pain with intercourse, I know it is unlikely that they have significant pelvic floor dysfunction. This is a key question for history taking.

Other key questions concern the impact of stress on symptoms and a history of any type of abuse. In a study we conducted about 10 years ago, we found that among 76 women who were diagnosed with IC and subsequently evaluated in our clinic, almost half (49%) reported abuse (emotional, physical, and/or sexual). The vast majority (85%) had levator pain (J Urol. 2007 Sep;178[3 Pt 1]:891-5).

Other types of stress – from past surgeries to traumatic life events – may similarly serve as triggers or precursors to pelvic floor dysfunction in some women. I often tell patients that people put stress in different areas of their bodies. While some get tension headaches or low-back aches, others get pelvic pain from contracting and guarding the levator muscles.

Pelvic floor dysfunction

The most important component of the physical exam in patients with the symptoms of frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – and the most overlooked – is assessment of the levator muscles for tightness and tenderness. Levator pain and trigger points may be identified during the pelvic exam by pressing laterally on the levator complex in each quadrant of the vagina and at the ischial spines. The tension of the muscles and severity of pain should be assessed, and it is helpful to ask the patient if the pain reproduces her normal pelvic pain symptoms.

We’ve found that identifying and treating pelvic floor dysfunction with modalities such as pelvic floor physical therapy with intravaginal myofascial release, intravaginal valium, trigger point injections into the levator complex, pudendal nerve blocks, and neuromodulation can frequently resolve or significantly lessen the patient’s pain and bladder symptoms, suggesting that the diagnosis of IC/BPS was wrong.

Pelvic floor physical therapy works to stretch the contracted anterior pelvic muscles by releasing trigger points and connective tissue restrictions, and by decreasing periurethral tension; it also may decrease neurogenic triggers and central nervous system sensitivity. Kegel exercises will worsen pain in these patients and should be avoided.

When pelvic floor dysfunction is identified, such treatment by a therapist knowledgeable in intravaginal myofascial release is a next reasonable step before any medications or invasive testing, such as bladder hydrodistension, are used.

One of the only National Institutes of Health–funded studies to show benefit of a treatment in an IC population, in fact, was a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing 10 sessions of myofascial pelvic floor physical therapy with “global therapeutic massage.” Myofascial physical therapy led to significant improvement, compared with the generalized spa-like massage (J Urol. 2012 Jun;187[6]:2113-8).

Our patients with IC/BPS symptoms and pelvic floor dysfunction require 1-2 visits weekly for an average of 12 weeks for tightness and tenderness to be significantly minimized or eliminated. Patients are also prescribed home stretching exercises and advised to use internal vaginal dilators. Most patients will report resolution of their pelvic pain, sexual pain, and bladder symptoms – especially with the combination of physical therapy and trigger point injections. In more severe cases, we may use sacral or pudendal neuromodulation to improve the frequency, urgency and pelvic pain.

Turning to the bladder

When urinary symptoms persist after the completion of pelvic floor therapy, or when pelvic floor dysfunction is not identified in the first place, we proceed with bladder-specific therapies. I will often suggest trials of amitriptyline or hydroxyzine, for instance, and/or changes in hydration and caffeine consumption. I am not a fan of pentosan polysulfate sodium (Elmiron) as it is a very expensive medication that has minimal benefit for the majority of patients.

When conservative therapies do not work, I move to cystoscopy with hydrodistension. The procedure can serve several purposes. It can be diagnostic, enabling us to rule out other potential symptom-causing pathologies, and it can be prognostic, helping us to understand when bladder capacity is severely reduced and to plan treatment. In some patients, it can even be therapeutic. Some of my patients have significant relief of symptoms from a hydrodistension of the bladder once or twice a year.

There is no standard method for performing a hydrodistension. I perform a complete cystoscopy to look for tumors, stones, diverticulum or Hunner’s lesions and, if the bladder is normal in appearance, I proceed with a 2-minute hydrodistension at 80-100 cm of water pressure under anesthesia. The bag is raised above the bladder, allowing the bladder to fill with the force of gravity and the pressures to equalize. The urethra must be compressed so that water doesn’t leak around the cystoscope. After 2 minutes of hydrodistension, the bladder is drained, volume is measured, and the procedure is repeated.

After the hydrodistension, the bladder is reinspected to be certain there is no bladder perforation and to evaluate for diffuse glomerulations (petechial hemorrhages) that are suggestive, but not diagnostic, of IC/BPS.

A holistic approach

Managing patients with voiding dysfunction and chronic pelvic pain can be a challenge, and a multidisciplinary approach is most effective. At Beaumont, we have a Women’s Urology Center that includes urologists, gynecologists, nurse practitioners, pelvic floor physical therapists, pain psychologists, colorectal specialists, sex therapists, and naturopathic and integrative medicine specialists who perform acupuncture, Reiki therapy, medical massage, and guided imagery.

The goal is to break out of our box of specialties and look at the whole patient – mind, body, and soul – while identifying pain triggers and directing therapy toward these triggers using a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach. For us, this approach has been very effective for managing complex pelvic pain issues (Transl Androl Urol. 2015 Dec;4[6]:611-9).

Ongoing studies

A number of research studies are ongoing to help treat the symptoms of IC/BPS. We currently have a Department of Defense grant to prospectively assess bladder-directed therapy (instillations) compared to pelvic floor physical therapy. Patients diagnosed with IC/BPS are being randomized into these two treatment arms and we hope to get a better understanding of the role of these modalities in managing IC/BPS.

Allergan is completing a phase II placebo-controlled trial using a lidocaine delivery device that is placed in the bladder and continuously releases lidocaine over 14 days. The LiNKA trial is designed to assess the impact of lidocaine on not only improving bladder symptoms, but also eradicating Hunner’s lesions through the anti-inflammatory effect of lidocaine. Early open-label data were very promising. In addition, a new medication for IC/BPS that modulates the SHIP1 pathway is being studied by Aquinox Pharmaceuticals. The agent, AQX-1125, is an activator of SHIP1, which controls the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) cellular signaling pathway. If the PI3K pathway is overactive, immune cells can produce an abundance of proinflammatory signaling molecules and migrate to and concentrate in tissues, resulting in excessive or chronic inflammation. Early data in IC/BPS patients were supportive of the compound’s potential for reducing the pain associated with this condition.

A note from Charles E. Miller, MD, Master Class Medical Editor:

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study by J.C. Nickel, et al., pentosan polysulfate sodium was shown to improve pain, urgency, and frequency over the control group (Urology. 2005 Apr;65[4]:654-8). Also, longer duration of treatment with pentosan polysulfate sodium was associated with greater response rates – 50% improved by 26 weeks (J Urol. 2005 Dec;174[6]:2235-8).

Dr. Peters is professor and chairman of urology at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Royal Oak, Mich. He reported serving as a consultant for Taris, Medtronic, StimGuard, and Amphora Medical.

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a controversial diagnosis that has become muddied and oversimplified. It was originally described as a distinct ulcer (Hunner’s lesion) seen in the bladder on cystoscopy, the treatment of which often led to symptomatic relief. Hunner’s lesion IC is the “classic” form of IC and should be considered a separate disease; it is not a progression of nonulcerative interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/BPS).

Only a fraction of patients with the key symptoms of IC/BPS – urinary frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain – have ulcers within the bladder. And many of the patients who are diagnosed with IC/BPS are found not to have bladder pathology as the name implies, but rather pelvic floor dysfunction. That the bladder is often an innocent bystander to a larger process means that, as clinicians, we must be thoughtful and astute about our diagnostic process.