User login

Child of The New Gastroenterologist

When Your First Job Isn’t Forever: Lessons from My Journey and What Early-Career GIs Need to Know

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Top 5 Tips for Becoming an Effective Gastroenterology Consultant

Gastroenterology (GI) subspecialty training is carefully designed to develop expertise in digestive diseases and gastrointestinal endoscopy, while facilitating the transition from generalist to subspecialty consultant. The concept of effective consultation extends far beyond clinical expertise and has been explored repeatedly, beginning with Goldman’s “Ten Commandments” in 1983.1,2 How should these best practices be specifically applied to GI? More importantly, what kind of experience would you want if you were the referring provider or the patient themselves?

Below are

1. Be Kind

Survey studies of medical/surgical residents and attending hospitalists have demonstrated that willingness to accept consultation requests was the single factor consistently rated as most important in determining the quality of the consultation interaction.3,4 Unfortunately, nearly 65% of respondents reported encountering pushback when requesting subspecialty consultation. It is critical to recognize that when you receive a GI consult request, the requester has already decided that it is needed. Whether that request comports with our individual notion of “necessary” or “important,” this is a colleague’s request for help. There are myriad reasons why a request may be made, but they are unified in this principle.

Effective teamwork in healthcare settings enhances clinical performance and patient safety. Positive relationships with colleagues and healthcare team members also mitigate the emotional basis for physician burnout.5 Be kind and courteous to those who seek your assistance. Move beyond the notion of the “bad” or “soft” consult and seek instead to understand how you can help.

A requesting physician may phrase the consult question vaguely or may know that the patient is having a GI-related issue, but simply lack the specific knowledge to know what is needed. In these instances, it is our role to listen and help guide them to the correct thought process to ensure the best care of the patient. These important interactions establish our reputation, create our referral bases, and directly affect our sense of personal satisfaction.

2. Be Timely

GI presents an appealing breadth of pathology, but this also corresponds to a wide variety of indications for consultation and, therefore, urgency of need. In a busy clinical practice, not all requests can be urgently prioritized. However, it is the consultant’s responsibility to identify patients that require urgent evaluation and intervention to avert a potential adverse outcome.

We are well-trained in the medical triage of consultations. There are explicit guidelines for assessing urgency for GI bleeding, foreign body ingestion, choledocholithiasis, and many other indications. However, there are often special contextual circumstances that will elevate the urgency of a seemingly non-urgent consult request. Does the patient have an upcoming surgery or treatment that will depend on your input? Are they facing an imminent loss of insurance coverage? Is their non-severe GI disease leading to more severe impact on non-GI organ systems? The referring provider knows the patient better than you – seek to understand the context of the consult request.

Timeliness also applies to our communication. Communicate recommendations directly to the consulting service as soon as the patient is seen. When a colleague reaches out with a concern about a patient, make sure to take that request seriously. If you are unable to address the concern immediately, at least provide acknowledgment and an estimated timeline for response. As the maxim states, the effectiveness of a consultant is just as dependent on availability as it is on ability.

3. Be Specific

The same survey studies indicate that the second most critical aspect of successful subspecialty consultation is delivering clear recommendations. Accordingly, I always urge my trainees to challenge me when we leave a consult interaction if they feel that our plan is vague or imprecise.

Specificity in consult recommendations is an essential way to demonstrate your expertise and provide value. Clear and definitive recommendations enhance others’ perception of your skill, reduce the need for additional clarifying communication, and lead to more efficient, higher quality care. Avoid vague language, such as asking the requester to “consider” a test or intervention. When recommending medication, specify the dose, frequency, duration, and expected timeline of effect. Rather than recommending “cross-sectional imaging,” specify what modality and protocol. Instead of recommending “adequate resuscitation,” specify your target endpoints. If you engage in multidisciplinary discussion, ensure you strive for a specific group consensus plan and communicate this to all members of the team.

Specificity also applies to the quality of your documentation. Ensure that your clinical notes outline your rationale for your recommended plan, specific contingencies based on results of recommended testing, and a plan for follow-up care. When referring for open-access endoscopy, specifically outline what to look for and which specimens or endoscopic interventions are needed. Be precise in your procedure documentation – avoid vague terms such as small/medium/large and instead quantify in terms of millimeter/centimeter measurement. If you do not adopt specific classification schemes (e.g. Prague classification, Paris classification, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, etc.), ensure you provide enough descriptive language to convey an adequate understanding of the findings.

4. Be Helpful

A consultant’s primary directive is to be of service to the consulting provider and the patient. As an educational leader, I am often asked what attributes separate a high-performing trainee from an average one. My feeling is that the most critical attribute is a sense of ownership over patient care.

As a consultant, when others feel we are exhibiting engagement and ownership in a patient’s care, they perceive that we are working together as an effective healthcare team. Interestingly, survey studies of inpatient care show that primary services do not necessarily value assistance with orders or care coordination – they consider these as core aspects of their daily work. What they did value was ongoing daily progress notes/communication, regardless of patient acuity or consulting specialty. This is a potent signal that our continued engagement (both inpatient and outpatient) is perceived as helpful.

Helpfulness is further aided by ensuring mutual understanding. While survey data indicate that sharing specific literature citations may not always be perceived positively, explaining the consultant’s rationale for their recommendations is highly valued. Take the time to tactfully explain your assessment of the patient and why you arrived at your specific recommendations. If your recommendations differ from what the requester expected (e.g. a procedure was expected but is not offered), ensure you explain why and answer questions they may have. This fosters mutual respect and proactively averts conflict or discontent from misunderstanding.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is another important avenue for aiding our patients and colleagues. Studies across a wide range of disease processes (including GI bleeding, IBD, etc.) and medical settings have demonstrated that multidisciplinary collaboration unequivocally improves patient outcomes.6 The success of these collaborations relies on our willingness to fully engage in these conversations, despite the fact that they may often be logistically challenging.

We all know how difficult it can be to locate and organize multiple medical specialists with complex varying clinical schedules and busy personal lives. Choosing to do so demonstrates a dedication to providing the highest level of care and elevates both patient and physician satisfaction. Having chosen to cultivate several ongoing multidisciplinary conferences/collaborations, I can attest to the notion that the outcome is well worth the effort.

5. Be Honest

While we always strive to provide the answers for our patients and colleagues, we must also acknowledge our limitations. Be honest with yourself when you encounter a scenario that pushes beyond the boundaries of your knowledge and comfort. Be willing to admit when you yourself need to consult others or seek an outside referral to provide the care a patient needs. Aspiring physicians often espouse that a devotion to lifelong learning is a key driver of their desire to pursue a career in medicine. These scenarios provide a key opportunity to expand our knowledge while doing what is right for our patients.

Be equally honest about your comfort with “curbside” consultations. Studies show that subspecialists receive on average of 3-4 such requests per week.7 The perception of these interactions is starkly discrepant between the requester and recipient. While over 80% of surveyed primary nonsurgical services felt that curbside consultations were helpful in patient care, a similar proportion of subspecialists expressed concern that insufficient clinical information was provided, even leading to a fear of litigation. While straightforward, informal conversations on narrow, well-defined questions can be helpful and efficient, the consultant should always feel comfortable seeking an opportunity for formal consultation when the details are unclear or the case/question is complex.

Closing Thoughts

Being an effective GI consultant isn’t just about what you know—it’s about how you apply it, how you communicate it, and how you make others feel in the process.

The attributes outlined above are not ancillary traits—they are essential components of high-quality consultation. When consistently applied, they enhance collaboration, improve patient outcomes, and reinforce trust within the healthcare system. By committing to them, you establish your reputation of excellence and play a role in elevating the field of gastroenterology more broadly.

Dr. Kahn is based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona. He reports no conflicts of interest in regard to this article.

References

1. Goldman L, et al. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Sep.

2. Salerno SM, et al. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.271.

3. Adams TN, et al. Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882.

4. Matsuo T, et al. Essential consultants’ skills and attitudes (Willing CONSULT): a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02810-9.

5. Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety - development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y.

6. Webster CS, et al. Interprofessional Learning in Multidisciplinary Healthcare Teams Is Associated With Reduced Patient Mortality: A Quantitative Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Patient Saf. 2024 Jan. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001170.

7. Lin M, et al. Curbside Consultations: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.026.

Gastroenterology (GI) subspecialty training is carefully designed to develop expertise in digestive diseases and gastrointestinal endoscopy, while facilitating the transition from generalist to subspecialty consultant. The concept of effective consultation extends far beyond clinical expertise and has been explored repeatedly, beginning with Goldman’s “Ten Commandments” in 1983.1,2 How should these best practices be specifically applied to GI? More importantly, what kind of experience would you want if you were the referring provider or the patient themselves?

Below are

1. Be Kind

Survey studies of medical/surgical residents and attending hospitalists have demonstrated that willingness to accept consultation requests was the single factor consistently rated as most important in determining the quality of the consultation interaction.3,4 Unfortunately, nearly 65% of respondents reported encountering pushback when requesting subspecialty consultation. It is critical to recognize that when you receive a GI consult request, the requester has already decided that it is needed. Whether that request comports with our individual notion of “necessary” or “important,” this is a colleague’s request for help. There are myriad reasons why a request may be made, but they are unified in this principle.

Effective teamwork in healthcare settings enhances clinical performance and patient safety. Positive relationships with colleagues and healthcare team members also mitigate the emotional basis for physician burnout.5 Be kind and courteous to those who seek your assistance. Move beyond the notion of the “bad” or “soft” consult and seek instead to understand how you can help.

A requesting physician may phrase the consult question vaguely or may know that the patient is having a GI-related issue, but simply lack the specific knowledge to know what is needed. In these instances, it is our role to listen and help guide them to the correct thought process to ensure the best care of the patient. These important interactions establish our reputation, create our referral bases, and directly affect our sense of personal satisfaction.

2. Be Timely

GI presents an appealing breadth of pathology, but this also corresponds to a wide variety of indications for consultation and, therefore, urgency of need. In a busy clinical practice, not all requests can be urgently prioritized. However, it is the consultant’s responsibility to identify patients that require urgent evaluation and intervention to avert a potential adverse outcome.

We are well-trained in the medical triage of consultations. There are explicit guidelines for assessing urgency for GI bleeding, foreign body ingestion, choledocholithiasis, and many other indications. However, there are often special contextual circumstances that will elevate the urgency of a seemingly non-urgent consult request. Does the patient have an upcoming surgery or treatment that will depend on your input? Are they facing an imminent loss of insurance coverage? Is their non-severe GI disease leading to more severe impact on non-GI organ systems? The referring provider knows the patient better than you – seek to understand the context of the consult request.

Timeliness also applies to our communication. Communicate recommendations directly to the consulting service as soon as the patient is seen. When a colleague reaches out with a concern about a patient, make sure to take that request seriously. If you are unable to address the concern immediately, at least provide acknowledgment and an estimated timeline for response. As the maxim states, the effectiveness of a consultant is just as dependent on availability as it is on ability.

3. Be Specific

The same survey studies indicate that the second most critical aspect of successful subspecialty consultation is delivering clear recommendations. Accordingly, I always urge my trainees to challenge me when we leave a consult interaction if they feel that our plan is vague or imprecise.

Specificity in consult recommendations is an essential way to demonstrate your expertise and provide value. Clear and definitive recommendations enhance others’ perception of your skill, reduce the need for additional clarifying communication, and lead to more efficient, higher quality care. Avoid vague language, such as asking the requester to “consider” a test or intervention. When recommending medication, specify the dose, frequency, duration, and expected timeline of effect. Rather than recommending “cross-sectional imaging,” specify what modality and protocol. Instead of recommending “adequate resuscitation,” specify your target endpoints. If you engage in multidisciplinary discussion, ensure you strive for a specific group consensus plan and communicate this to all members of the team.

Specificity also applies to the quality of your documentation. Ensure that your clinical notes outline your rationale for your recommended plan, specific contingencies based on results of recommended testing, and a plan for follow-up care. When referring for open-access endoscopy, specifically outline what to look for and which specimens or endoscopic interventions are needed. Be precise in your procedure documentation – avoid vague terms such as small/medium/large and instead quantify in terms of millimeter/centimeter measurement. If you do not adopt specific classification schemes (e.g. Prague classification, Paris classification, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, etc.), ensure you provide enough descriptive language to convey an adequate understanding of the findings.

4. Be Helpful

A consultant’s primary directive is to be of service to the consulting provider and the patient. As an educational leader, I am often asked what attributes separate a high-performing trainee from an average one. My feeling is that the most critical attribute is a sense of ownership over patient care.

As a consultant, when others feel we are exhibiting engagement and ownership in a patient’s care, they perceive that we are working together as an effective healthcare team. Interestingly, survey studies of inpatient care show that primary services do not necessarily value assistance with orders or care coordination – they consider these as core aspects of their daily work. What they did value was ongoing daily progress notes/communication, regardless of patient acuity or consulting specialty. This is a potent signal that our continued engagement (both inpatient and outpatient) is perceived as helpful.

Helpfulness is further aided by ensuring mutual understanding. While survey data indicate that sharing specific literature citations may not always be perceived positively, explaining the consultant’s rationale for their recommendations is highly valued. Take the time to tactfully explain your assessment of the patient and why you arrived at your specific recommendations. If your recommendations differ from what the requester expected (e.g. a procedure was expected but is not offered), ensure you explain why and answer questions they may have. This fosters mutual respect and proactively averts conflict or discontent from misunderstanding.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is another important avenue for aiding our patients and colleagues. Studies across a wide range of disease processes (including GI bleeding, IBD, etc.) and medical settings have demonstrated that multidisciplinary collaboration unequivocally improves patient outcomes.6 The success of these collaborations relies on our willingness to fully engage in these conversations, despite the fact that they may often be logistically challenging.

We all know how difficult it can be to locate and organize multiple medical specialists with complex varying clinical schedules and busy personal lives. Choosing to do so demonstrates a dedication to providing the highest level of care and elevates both patient and physician satisfaction. Having chosen to cultivate several ongoing multidisciplinary conferences/collaborations, I can attest to the notion that the outcome is well worth the effort.

5. Be Honest

While we always strive to provide the answers for our patients and colleagues, we must also acknowledge our limitations. Be honest with yourself when you encounter a scenario that pushes beyond the boundaries of your knowledge and comfort. Be willing to admit when you yourself need to consult others or seek an outside referral to provide the care a patient needs. Aspiring physicians often espouse that a devotion to lifelong learning is a key driver of their desire to pursue a career in medicine. These scenarios provide a key opportunity to expand our knowledge while doing what is right for our patients.

Be equally honest about your comfort with “curbside” consultations. Studies show that subspecialists receive on average of 3-4 such requests per week.7 The perception of these interactions is starkly discrepant between the requester and recipient. While over 80% of surveyed primary nonsurgical services felt that curbside consultations were helpful in patient care, a similar proportion of subspecialists expressed concern that insufficient clinical information was provided, even leading to a fear of litigation. While straightforward, informal conversations on narrow, well-defined questions can be helpful and efficient, the consultant should always feel comfortable seeking an opportunity for formal consultation when the details are unclear or the case/question is complex.

Closing Thoughts

Being an effective GI consultant isn’t just about what you know—it’s about how you apply it, how you communicate it, and how you make others feel in the process.

The attributes outlined above are not ancillary traits—they are essential components of high-quality consultation. When consistently applied, they enhance collaboration, improve patient outcomes, and reinforce trust within the healthcare system. By committing to them, you establish your reputation of excellence and play a role in elevating the field of gastroenterology more broadly.

Dr. Kahn is based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona. He reports no conflicts of interest in regard to this article.

References

1. Goldman L, et al. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Sep.

2. Salerno SM, et al. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.271.

3. Adams TN, et al. Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882.

4. Matsuo T, et al. Essential consultants’ skills and attitudes (Willing CONSULT): a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02810-9.

5. Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety - development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y.

6. Webster CS, et al. Interprofessional Learning in Multidisciplinary Healthcare Teams Is Associated With Reduced Patient Mortality: A Quantitative Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Patient Saf. 2024 Jan. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001170.

7. Lin M, et al. Curbside Consultations: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.026.

Gastroenterology (GI) subspecialty training is carefully designed to develop expertise in digestive diseases and gastrointestinal endoscopy, while facilitating the transition from generalist to subspecialty consultant. The concept of effective consultation extends far beyond clinical expertise and has been explored repeatedly, beginning with Goldman’s “Ten Commandments” in 1983.1,2 How should these best practices be specifically applied to GI? More importantly, what kind of experience would you want if you were the referring provider or the patient themselves?

Below are

1. Be Kind

Survey studies of medical/surgical residents and attending hospitalists have demonstrated that willingness to accept consultation requests was the single factor consistently rated as most important in determining the quality of the consultation interaction.3,4 Unfortunately, nearly 65% of respondents reported encountering pushback when requesting subspecialty consultation. It is critical to recognize that when you receive a GI consult request, the requester has already decided that it is needed. Whether that request comports with our individual notion of “necessary” or “important,” this is a colleague’s request for help. There are myriad reasons why a request may be made, but they are unified in this principle.

Effective teamwork in healthcare settings enhances clinical performance and patient safety. Positive relationships with colleagues and healthcare team members also mitigate the emotional basis for physician burnout.5 Be kind and courteous to those who seek your assistance. Move beyond the notion of the “bad” or “soft” consult and seek instead to understand how you can help.

A requesting physician may phrase the consult question vaguely or may know that the patient is having a GI-related issue, but simply lack the specific knowledge to know what is needed. In these instances, it is our role to listen and help guide them to the correct thought process to ensure the best care of the patient. These important interactions establish our reputation, create our referral bases, and directly affect our sense of personal satisfaction.

2. Be Timely

GI presents an appealing breadth of pathology, but this also corresponds to a wide variety of indications for consultation and, therefore, urgency of need. In a busy clinical practice, not all requests can be urgently prioritized. However, it is the consultant’s responsibility to identify patients that require urgent evaluation and intervention to avert a potential adverse outcome.

We are well-trained in the medical triage of consultations. There are explicit guidelines for assessing urgency for GI bleeding, foreign body ingestion, choledocholithiasis, and many other indications. However, there are often special contextual circumstances that will elevate the urgency of a seemingly non-urgent consult request. Does the patient have an upcoming surgery or treatment that will depend on your input? Are they facing an imminent loss of insurance coverage? Is their non-severe GI disease leading to more severe impact on non-GI organ systems? The referring provider knows the patient better than you – seek to understand the context of the consult request.

Timeliness also applies to our communication. Communicate recommendations directly to the consulting service as soon as the patient is seen. When a colleague reaches out with a concern about a patient, make sure to take that request seriously. If you are unable to address the concern immediately, at least provide acknowledgment and an estimated timeline for response. As the maxim states, the effectiveness of a consultant is just as dependent on availability as it is on ability.

3. Be Specific

The same survey studies indicate that the second most critical aspect of successful subspecialty consultation is delivering clear recommendations. Accordingly, I always urge my trainees to challenge me when we leave a consult interaction if they feel that our plan is vague or imprecise.

Specificity in consult recommendations is an essential way to demonstrate your expertise and provide value. Clear and definitive recommendations enhance others’ perception of your skill, reduce the need for additional clarifying communication, and lead to more efficient, higher quality care. Avoid vague language, such as asking the requester to “consider” a test or intervention. When recommending medication, specify the dose, frequency, duration, and expected timeline of effect. Rather than recommending “cross-sectional imaging,” specify what modality and protocol. Instead of recommending “adequate resuscitation,” specify your target endpoints. If you engage in multidisciplinary discussion, ensure you strive for a specific group consensus plan and communicate this to all members of the team.

Specificity also applies to the quality of your documentation. Ensure that your clinical notes outline your rationale for your recommended plan, specific contingencies based on results of recommended testing, and a plan for follow-up care. When referring for open-access endoscopy, specifically outline what to look for and which specimens or endoscopic interventions are needed. Be precise in your procedure documentation – avoid vague terms such as small/medium/large and instead quantify in terms of millimeter/centimeter measurement. If you do not adopt specific classification schemes (e.g. Prague classification, Paris classification, Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, etc.), ensure you provide enough descriptive language to convey an adequate understanding of the findings.

4. Be Helpful

A consultant’s primary directive is to be of service to the consulting provider and the patient. As an educational leader, I am often asked what attributes separate a high-performing trainee from an average one. My feeling is that the most critical attribute is a sense of ownership over patient care.

As a consultant, when others feel we are exhibiting engagement and ownership in a patient’s care, they perceive that we are working together as an effective healthcare team. Interestingly, survey studies of inpatient care show that primary services do not necessarily value assistance with orders or care coordination – they consider these as core aspects of their daily work. What they did value was ongoing daily progress notes/communication, regardless of patient acuity or consulting specialty. This is a potent signal that our continued engagement (both inpatient and outpatient) is perceived as helpful.

Helpfulness is further aided by ensuring mutual understanding. While survey data indicate that sharing specific literature citations may not always be perceived positively, explaining the consultant’s rationale for their recommendations is highly valued. Take the time to tactfully explain your assessment of the patient and why you arrived at your specific recommendations. If your recommendations differ from what the requester expected (e.g. a procedure was expected but is not offered), ensure you explain why and answer questions they may have. This fosters mutual respect and proactively averts conflict or discontent from misunderstanding.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is another important avenue for aiding our patients and colleagues. Studies across a wide range of disease processes (including GI bleeding, IBD, etc.) and medical settings have demonstrated that multidisciplinary collaboration unequivocally improves patient outcomes.6 The success of these collaborations relies on our willingness to fully engage in these conversations, despite the fact that they may often be logistically challenging.

We all know how difficult it can be to locate and organize multiple medical specialists with complex varying clinical schedules and busy personal lives. Choosing to do so demonstrates a dedication to providing the highest level of care and elevates both patient and physician satisfaction. Having chosen to cultivate several ongoing multidisciplinary conferences/collaborations, I can attest to the notion that the outcome is well worth the effort.

5. Be Honest

While we always strive to provide the answers for our patients and colleagues, we must also acknowledge our limitations. Be honest with yourself when you encounter a scenario that pushes beyond the boundaries of your knowledge and comfort. Be willing to admit when you yourself need to consult others or seek an outside referral to provide the care a patient needs. Aspiring physicians often espouse that a devotion to lifelong learning is a key driver of their desire to pursue a career in medicine. These scenarios provide a key opportunity to expand our knowledge while doing what is right for our patients.

Be equally honest about your comfort with “curbside” consultations. Studies show that subspecialists receive on average of 3-4 such requests per week.7 The perception of these interactions is starkly discrepant between the requester and recipient. While over 80% of surveyed primary nonsurgical services felt that curbside consultations were helpful in patient care, a similar proportion of subspecialists expressed concern that insufficient clinical information was provided, even leading to a fear of litigation. While straightforward, informal conversations on narrow, well-defined questions can be helpful and efficient, the consultant should always feel comfortable seeking an opportunity for formal consultation when the details are unclear or the case/question is complex.

Closing Thoughts

Being an effective GI consultant isn’t just about what you know—it’s about how you apply it, how you communicate it, and how you make others feel in the process.

The attributes outlined above are not ancillary traits—they are essential components of high-quality consultation. When consistently applied, they enhance collaboration, improve patient outcomes, and reinforce trust within the healthcare system. By committing to them, you establish your reputation of excellence and play a role in elevating the field of gastroenterology more broadly.

Dr. Kahn is based in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona. He reports no conflicts of interest in regard to this article.

References

1. Goldman L, et al. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Sep.

2. Salerno SM, et al. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.271.

3. Adams TN, et al. Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882.

4. Matsuo T, et al. Essential consultants’ skills and attitudes (Willing CONSULT): a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02810-9.

5. Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety - development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y.

6. Webster CS, et al. Interprofessional Learning in Multidisciplinary Healthcare Teams Is Associated With Reduced Patient Mortality: A Quantitative Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Patient Saf. 2024 Jan. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001170.

7. Lin M, et al. Curbside Consultations: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.026.

Practical Tips on Delivering Feedback to Trainees and Colleagues

Feedback is the purposeful practice of offering constructive, goal-directed input rooted in the power of observation and behavioral assessment. Healthcare inherently fosters a broad range of interactions among people with unique insights, and feedback can naturally emerge from this milieu. In medical training, feedback is an indispensable element that personalizes the learning process and drives the professional development of physicians through all career stages.

If delivered effectively, feedback can strengthen the relationship between the evaluator and recipient, promote self-reflection, and enhance motivation. As such, it has the potential to impact us and those we serve for a lifetime. Feedback has been invaluable to our growth as clinicians and has been embedded into our roles as educators. However, Here, we provide some “tried and true” practical tips on delivering feedback to trainees and co-workers and on navigating potential barriers based on lessons learned.

Barriers to Effective Feedback

- Time: Feedback is predicated on observation over time and consideration of repetitive processes rather than isolated events. Perhaps the most challenging factor faced by both parties is that of time constraints, leading to limited ability to engage and build rapport.

- Fear: Hesitancy by evaluators to provide feedback in fear of negative impacts on the recipient’s morale or rapport can lead them to shy away from personalized corrective feedback strategies and choose to rely on written evaluations or generic advice.

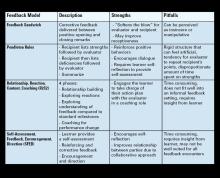

- Varying approaches: Feedback strategies have evolved from unidirectional, critique-based, hierarchical practices that emphasize the evaluator’s skills to models that prioritize the recipient’s goals and participation (see Table 1). Traditionally employed feedback models such as the “Feedback Sandwich” or the “Pendleton Rules” are criticized because of a lack of proven benefit on performance, recipient goal prioritization, and open communication.1,2 Studies showing incongruent perceptions of feedback adequacy between trainees and faculty further support the need for recipient-focused strategies.3 Recognition of the foundational role of the reciprocal learner-teacher alliance in feedback integration inspired newer feedback models, such as the “R2C2” and the “Self-Assessment, Feedback, Encouragement, Direction.”4,5

But which way is best? With increasing abundance and complexity of feedback frameworks, selecting an approach can feel overwhelming and impractical. A generic “one-size-fits-all” strategy or avoidance of feedback altogether can be detrimental. Structured feedback models can also lead to rigid, inauthentic interactions. Below, we suggest a more practical approach through our tips that unifies the common themes of various feedback models and embeds them into daily practice habits while leaving room for personalization.

Our Practical Feedback Tips

Tip 1: Set the scene: Create a positive feedback culture

Proactively creating a culture in which feedback is embedded and encouraged is perhaps the most important step. Priming both parties for feedback clarifies intent, increases receptiveness, and paves the way for growth and open communication. It also prevents the misinterpretation of unexpected feedback as an expression of disapproval. To do this, start by regularly stating your intentions at the start of every experience. Explicitly expressing your vision for mutual learning, bidirectional feedback, and growth in your respective roles attaches a positive intention to feedback. Providing a reminder that we are all works in progress and acknowledging this on a regular basis sets the stage for structured growth opportunities.

Scheduling future feedback encounters from the start maintains accountability and prevents feedback from being perceived as the consequence of a particular behavior. The number and timing of feedback sessions can be customized to the duration of the working relationship, generally allowing enough time for a second interaction (at the end of each week, halfway point, etc.).

Tip 2: Build rapport

Increasing clinical workloads and pressure to teach in time-constrained settings often results in insufficient time to engage in conversation and trust building. However, a foundational relationship is an essential precursor to meaningful feedback. Ramani et al. state that “relationships, not recipes, are more likely to promote feedback that has an impact on learner performance and ultimately patient care.”6 Building this rapport can begin by dedicating a few minutes (before/during rounds, between cases) to exchange information about career interests, hobbies, favorite restaurants, etc. This “small talk” is the beginning of a two-way exchange that ultimately develops into more meaningful exchanges.

In our experience, this simple step is impactful and fulfilling to both parties. This is also a good time for shared vulnerability by talking about what you are currently working on or have worked on at their stage to affirm that feedback is a continuous part of professional development and not a reflection of how far they are from competence at a given point in time.

Tip 3: Consider Timing, assess readiness, and preschedule sessions

Lack of attention to timing can hinder feedback acceptance. We suggest adhering to delivering positive feedback publicly and corrective feedback privately (“Praise in public, perfect in private”). This reinforces positive behaviors, increases motivation, and minimizes demoralization. Prolonged delays between the observed behavior and feedback can decrease its relevance. Conversely, delivering feedback too soon after an emotionally charged experience can be perceived as blame. Pre-designated times for feedback can minimize the guesswork and maintain your accountability for giving feedback without inadvertently linking it to one particular behavior. If the recipient does not appear to be in a state to receive feedback at the predesignated time, you can pivot to a “check-in” session to show support and strengthen rapport.

Tip 4: Customize to the learner and set shared goals

Diversity in backgrounds, perspectives, and personalities can impact how people perceive their own performances and experience feedback. Given the profound impact of sociocultural factors on feedback assimilation, maintaining the recipient and their goals at the core of performance evaluations is key to feedback acceptance.

A. Trainees

We suggest starting by introducing the idea of feedback as a partnership and something you feel privileged to do to help them achieve mutual goals. It helps to ask them to use the first day to get oriented with the experience, general expectations, challenges they expect to encounter, and their feedback goals. Tailoring your feedback to their goals creates a sense of shared purpose which increases motivation. Encouraging them to develop their own strategies allows them to play an active role in their growth. Giving them the opportunity to share their perceived strengths and deficiencies provides you with valuable information regarding their insight and ability to self-evaluate. This can help you predict their readiness for your feedback and to tailor your approach when there is a mismatch.

Examples:

- Medical student: Start with “What do you think you are doing well?” and “What do you think you need to work on?” Build on their response with encouragement and empathy. This helps make them more deliberate with what they work on because being a medical student can be overwhelming and can feel as though they have everything to work on.

- Resident/Fellow: By this point, trainees usually have an increased awareness of their strengths and deficiencies. Your questions can then be more specific, giving them autonomy over their learning, such as “What are some of the things you are working on that you want me to give you feedback on this week?” This makes them more aware, intentional, and receptive to your feedback because it is framed as something that they sought out.

B. Colleagues/Staff

Unlike the training environment in which feedback is built-in, giving feedback to co-workers requires you to establish a feedback-conducive environment and to develop a more in-depth understanding of coworkers’ personalities. Similar strategies can be applied, such as proactively setting the scene for open communication, scheduling check-ins, demonstrating receptiveness to feedback, and investing in trust-building.

Longer working relationships allow for strong foundational connections that make feedback less threatening. Personality assessment testing like Myers-Briggs Type Indicator or DiSC Assessment can aid in tailoring feedback to different individuals.7,8 An analytical thinker may appreciate direct, data-driven feedback. Relationship-oriented individuals might respond better to softer, encouragement-based approaches. Always maintain shared goals at the center of your interactions and consider collaborative opportunities such as quality improvement projects. This can improve your working relationship in a constructive way without casting blame.

Tip 5: Work on delivery: Bidirectional communication and body language

Non-verbal cues can have a profound impact on how your feedback is interpreted and on the recipient’s comfort to engage in conversation. Sitting down, making eye contact, nodding, and avoiding closed-off body posture can project support and feel less judgmental. Creating a safe and non-distracted environment with privacy can make them feel valued. Use motivating, respectful language focused on directly observed behaviors rather than personal attributes or second-hand reports.

Remember that focusing on repetitive patterns is likely more helpful than isolated incidents. Validate their hard work and give them a global idea of where they stand before diving into individual behaviors. Encourage their participation and empower them to suggest changes they plan to implement. Conclude by having them summarize their action plan to give them ownership and to verify that your feedback was interpreted as you intended. Thank them for being a part of the process, as it does take a partnership for feedback to be effective.

Tip 6: Be open to feedback

Demonstrating your willingness to accept and act on feedback reinforces a positive culture where feedback is normalized and valued. After an unintended outcome, initiate a two-way conversation and ask their input on anything they wish you would have done differently. This reaffirms your commitment to maintaining culture that does not revolve around one-sided critiques. Frequently soliciting feedback about your feedback skills can also guide you to adapt your approach and to recognize any ineffective feedback practices.

Tip 7: When things don’t go as planned

Receiving feedback, no matter how thoughtfully it is delivered, can be an emotionally-charged experience ending in hurt feelings. This happens because of misinterpretation of feedback as an indicator of inadequacy, heightened awareness of underlying insecurities, sociocultural or personal circumstances, frustration with oneself, needing additional guidance, or being caught off-guard by the assessment.

The evaluator should always acknowledge the recipient’s feelings, show compassion, and allow time for processing. When they are ready to talk, it is important to help reframe the recipients’ mindsets to recognize that feedback is not personal or defining and is not a “one and done” reflection of whether they have “made it.” Instead, it is a continual process that we benefit from through all career stages. Again, shared vulnerability can help to normalize feedback and maintain open dialogue. Setting an opportunity for a future check-in can reinforce support and lead to a more productive conversation after they have had time to process.

Conclusion

Effective feedback delivery is an invaluable skill that can result in meaningful goal-directed changes while strengthening professional relationships. Given the complexity of feedback interactions and the many factors that influence its acceptance, no single approach is suitable for all recipients and frequent adaptation of the approach is essential.

In our experience, adhering to these general overarching feedback principles (see Figure 1) has allowed us to have more successful interactions with trainees and colleagues.

Dr. Baliss is based in the Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. Dr. Hachem is director of the Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Health at Intermountain Medical, Sandy, Utah. Both authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Parkes J, et al. Feedback sandwiches affect perceptions but not performance. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013 Aug. doi:10.1007/s10459-012-9377-9.

2. van de Ridder JMM and Wijnen-Meijer M. Pendleton’s Rules: A Mini Review of a Feedback Method. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2023 May. doi: 10.34297/AJBSR.2023.19.002542.

3. Sender Liberman A, et al. Surgery residents and attending surgeons have different perceptions of feedback. Med Teach. 2005 Aug. doi: 10.1080/0142590500129183.

4. Sargeant J, et al. R2C2 in Action: Testing an Evidence-Based Model to Facilitate Feedback and Coaching in Residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00398.1.

5. Liakos W, et al. Frameworks for Effective Feedback in Health Professions Education. Acad Med. 2023 May. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004884.

6. Ramani S, et al. Feedback Redefined: Principles and Practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 May. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04874-2.

7. Woods RA and Hill PB. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. 2022 Sept. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554596/

8. Slowikowski MK. Using the DISC behavioral instrument to guide leadership and communication. AORN J. 2005 Nov. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)60276-7.

Feedback is the purposeful practice of offering constructive, goal-directed input rooted in the power of observation and behavioral assessment. Healthcare inherently fosters a broad range of interactions among people with unique insights, and feedback can naturally emerge from this milieu. In medical training, feedback is an indispensable element that personalizes the learning process and drives the professional development of physicians through all career stages.

If delivered effectively, feedback can strengthen the relationship between the evaluator and recipient, promote self-reflection, and enhance motivation. As such, it has the potential to impact us and those we serve for a lifetime. Feedback has been invaluable to our growth as clinicians and has been embedded into our roles as educators. However, Here, we provide some “tried and true” practical tips on delivering feedback to trainees and co-workers and on navigating potential barriers based on lessons learned.

Barriers to Effective Feedback

- Time: Feedback is predicated on observation over time and consideration of repetitive processes rather than isolated events. Perhaps the most challenging factor faced by both parties is that of time constraints, leading to limited ability to engage and build rapport.

- Fear: Hesitancy by evaluators to provide feedback in fear of negative impacts on the recipient’s morale or rapport can lead them to shy away from personalized corrective feedback strategies and choose to rely on written evaluations or generic advice.

- Varying approaches: Feedback strategies have evolved from unidirectional, critique-based, hierarchical practices that emphasize the evaluator’s skills to models that prioritize the recipient’s goals and participation (see Table 1). Traditionally employed feedback models such as the “Feedback Sandwich” or the “Pendleton Rules” are criticized because of a lack of proven benefit on performance, recipient goal prioritization, and open communication.1,2 Studies showing incongruent perceptions of feedback adequacy between trainees and faculty further support the need for recipient-focused strategies.3 Recognition of the foundational role of the reciprocal learner-teacher alliance in feedback integration inspired newer feedback models, such as the “R2C2” and the “Self-Assessment, Feedback, Encouragement, Direction.”4,5

But which way is best? With increasing abundance and complexity of feedback frameworks, selecting an approach can feel overwhelming and impractical. A generic “one-size-fits-all” strategy or avoidance of feedback altogether can be detrimental. Structured feedback models can also lead to rigid, inauthentic interactions. Below, we suggest a more practical approach through our tips that unifies the common themes of various feedback models and embeds them into daily practice habits while leaving room for personalization.

Our Practical Feedback Tips

Tip 1: Set the scene: Create a positive feedback culture

Proactively creating a culture in which feedback is embedded and encouraged is perhaps the most important step. Priming both parties for feedback clarifies intent, increases receptiveness, and paves the way for growth and open communication. It also prevents the misinterpretation of unexpected feedback as an expression of disapproval. To do this, start by regularly stating your intentions at the start of every experience. Explicitly expressing your vision for mutual learning, bidirectional feedback, and growth in your respective roles attaches a positive intention to feedback. Providing a reminder that we are all works in progress and acknowledging this on a regular basis sets the stage for structured growth opportunities.

Scheduling future feedback encounters from the start maintains accountability and prevents feedback from being perceived as the consequence of a particular behavior. The number and timing of feedback sessions can be customized to the duration of the working relationship, generally allowing enough time for a second interaction (at the end of each week, halfway point, etc.).

Tip 2: Build rapport

Increasing clinical workloads and pressure to teach in time-constrained settings often results in insufficient time to engage in conversation and trust building. However, a foundational relationship is an essential precursor to meaningful feedback. Ramani et al. state that “relationships, not recipes, are more likely to promote feedback that has an impact on learner performance and ultimately patient care.”6 Building this rapport can begin by dedicating a few minutes (before/during rounds, between cases) to exchange information about career interests, hobbies, favorite restaurants, etc. This “small talk” is the beginning of a two-way exchange that ultimately develops into more meaningful exchanges.

In our experience, this simple step is impactful and fulfilling to both parties. This is also a good time for shared vulnerability by talking about what you are currently working on or have worked on at their stage to affirm that feedback is a continuous part of professional development and not a reflection of how far they are from competence at a given point in time.

Tip 3: Consider Timing, assess readiness, and preschedule sessions

Lack of attention to timing can hinder feedback acceptance. We suggest adhering to delivering positive feedback publicly and corrective feedback privately (“Praise in public, perfect in private”). This reinforces positive behaviors, increases motivation, and minimizes demoralization. Prolonged delays between the observed behavior and feedback can decrease its relevance. Conversely, delivering feedback too soon after an emotionally charged experience can be perceived as blame. Pre-designated times for feedback can minimize the guesswork and maintain your accountability for giving feedback without inadvertently linking it to one particular behavior. If the recipient does not appear to be in a state to receive feedback at the predesignated time, you can pivot to a “check-in” session to show support and strengthen rapport.

Tip 4: Customize to the learner and set shared goals

Diversity in backgrounds, perspectives, and personalities can impact how people perceive their own performances and experience feedback. Given the profound impact of sociocultural factors on feedback assimilation, maintaining the recipient and their goals at the core of performance evaluations is key to feedback acceptance.

A. Trainees

We suggest starting by introducing the idea of feedback as a partnership and something you feel privileged to do to help them achieve mutual goals. It helps to ask them to use the first day to get oriented with the experience, general expectations, challenges they expect to encounter, and their feedback goals. Tailoring your feedback to their goals creates a sense of shared purpose which increases motivation. Encouraging them to develop their own strategies allows them to play an active role in their growth. Giving them the opportunity to share their perceived strengths and deficiencies provides you with valuable information regarding their insight and ability to self-evaluate. This can help you predict their readiness for your feedback and to tailor your approach when there is a mismatch.

Examples:

- Medical student: Start with “What do you think you are doing well?” and “What do you think you need to work on?” Build on their response with encouragement and empathy. This helps make them more deliberate with what they work on because being a medical student can be overwhelming and can feel as though they have everything to work on.