User login

New and transitioning gastroenterologists face burnout too

The field of gastroenterology can be challenging, both professionally and personally, leading to burnout, especially for new and transitioning gastroenterologists. Burnout is a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by prolonged or excessive stress.1 It is characterized by emotional fatigue, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.2,3 This condition can have severe consequences for physicians and their patients.

More than 50% of physicians report meeting the criteria for burnout, which is pervasive in all medical professions.3 Survey results of 7,288 U.S. physicians showed that burnout and dissatisfaction with work-life balance are significantly higher than among other working U.S. adults.3

The long and often irregular work hours expected of gastroenterologists significantly contribute to burnout within our field. The physically, intellectually, and technically demanding reality of managing complex patients and making high stakes decisions at all hours has far-reaching consequences.3 Most gastroenterologists work between 55 and 60 hours per week.4 This sharply contrasts the average 43-hour work week for full-time employees in the United States.5 Gastroenterologists may experience inaccurate perceptions of their commitment to patients, education, and their families based solely on time observed on each activity.4 Higher education and professional degrees usually protect against burnout.3 However, a degree in medicine (MD or DO) increases the burnout risk.3

New gastroenterologists are learning a wide range of intricate procedures and becoming proficient in diagnosing and managing gastrointestinal disorders. Extensive career demands often coincide with intense family-forming years, creating tension for a physician’s finite time and energy. The culture of medicine demanding “patients come first” while attempting to be fully human can sometimes feel irreconcilable, leading to feelings of inadequacy and anxiety.3 Gastroenterology training takes 3 years because of the complexity, danger, and need for thousands of procedures to gain proficiency and competence to recognize when complications occur. Oversight is ubiquitous during training, making this the ideal time to learn from mistakes and formulate lifelong habits of constant improvement. However, perfectionist tendencies and the Hippocratic Oath can create unrealistic self expectations.6 The risk of potential litigation, simply missing a diagnosis, or causing actual patient harm is never far from a proceduralist’s mind.

The diversity of gastroenterology requires high clinical knowledge, expertise, and emotional intelligence. Leading potentially intense end-of-life, cancer, fertility, and risk-factor discussions can be all-consuming. Keeping up with the latest research, treatments, and techniques in the field can be daunting. Furthermore, gastroenterologists spend many hours each day on electronic medical records. Constant re-documentation of interactions, seemingly endless prior authorizations, disability forms, referrals, and simply re-addressing patient and family concerns can feel low value. This uncompensated work also creates moral injury as it takes away from direct patient care.

Striking a work-life balance

New gastroenterologists are advised to find work-life balance. However, they are also plagued by the massive professional demands being constantly placed on them. The desire to find the mythical “balance” may create a mindset of significant sacrifices in their private lives as the only way to achieve professional successes.7 When gastroenterologists do not prioritize time for personal activities, including exercise, health checks, hobbies, rest, relaxation, family, and friends, they can get caught in a vicious cycle of continuing to feel poorly, resulting in overcompensating by working more in order to feel “accomplished.” The perfectionist pressure to maintain high productivity and patient satisfaction can also further contribute to burnout.

Gastroenterology burnout can severely affect physicians’ health status, job performance, and patient satisfaction.9 It may erode professionalism, negatively influence the quality of care, increase the risk of medical errors, and promote early retirement.3 Burnout may also correlate with adverse personal consequences for physicians, such as broken relationships, problematic alcohol use, and suicidal ideation.3 Physician burnout and professional satisfaction have strategic importance to health care organizations.10 Less burned-out physicians have patient panels with higher adherence and satisfaction with medical care.10 With more physicians becoming employees, there are opportunities for accountability of organizational leadership.10 Interestingly, healthy well-being or burnout is contagious from leaders to their teams.10 A 2015 study by Shanafelt et al. found that at the work unit level, 11% and 47% of the variation in burnout and satisfaction, correlated with the leader’s relative scores.10

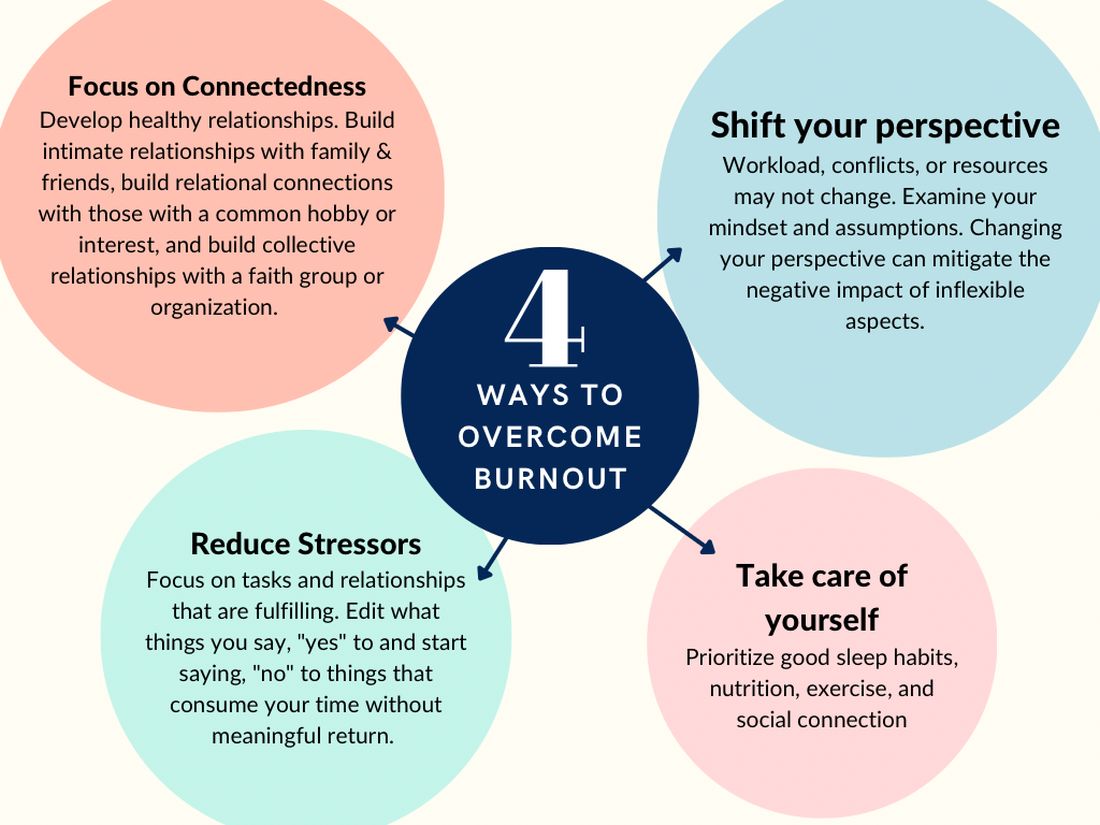

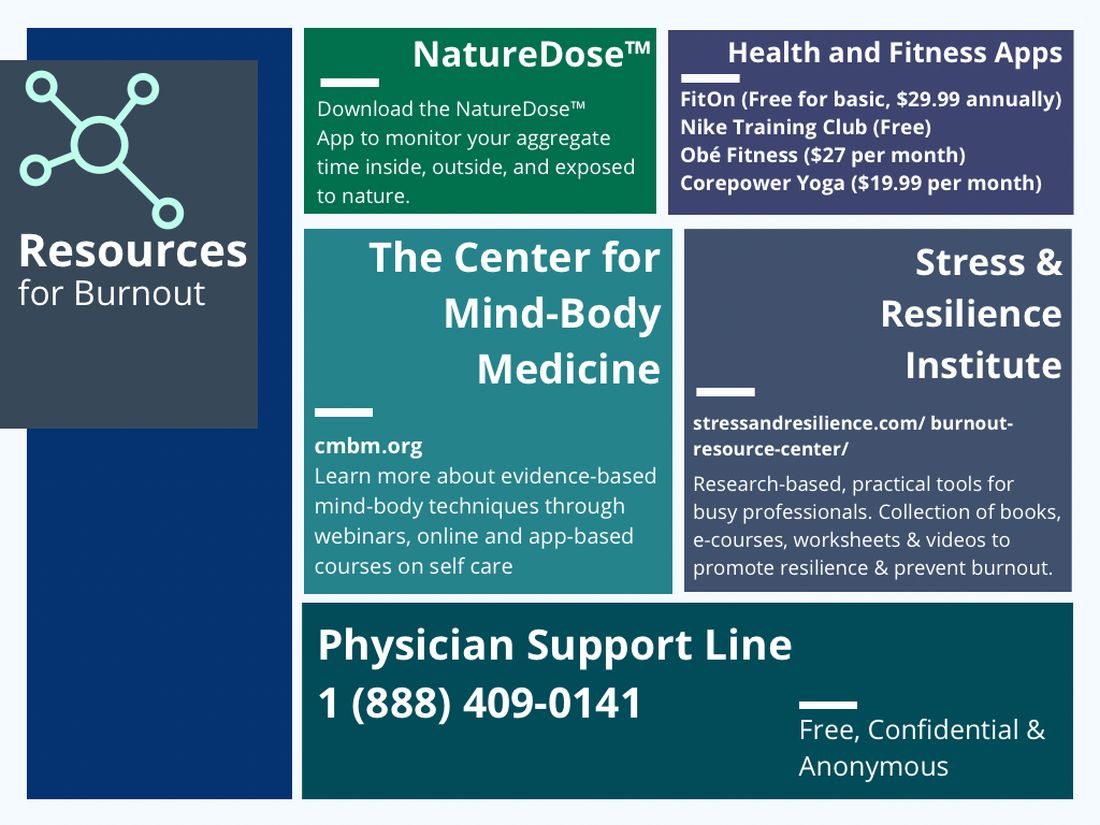

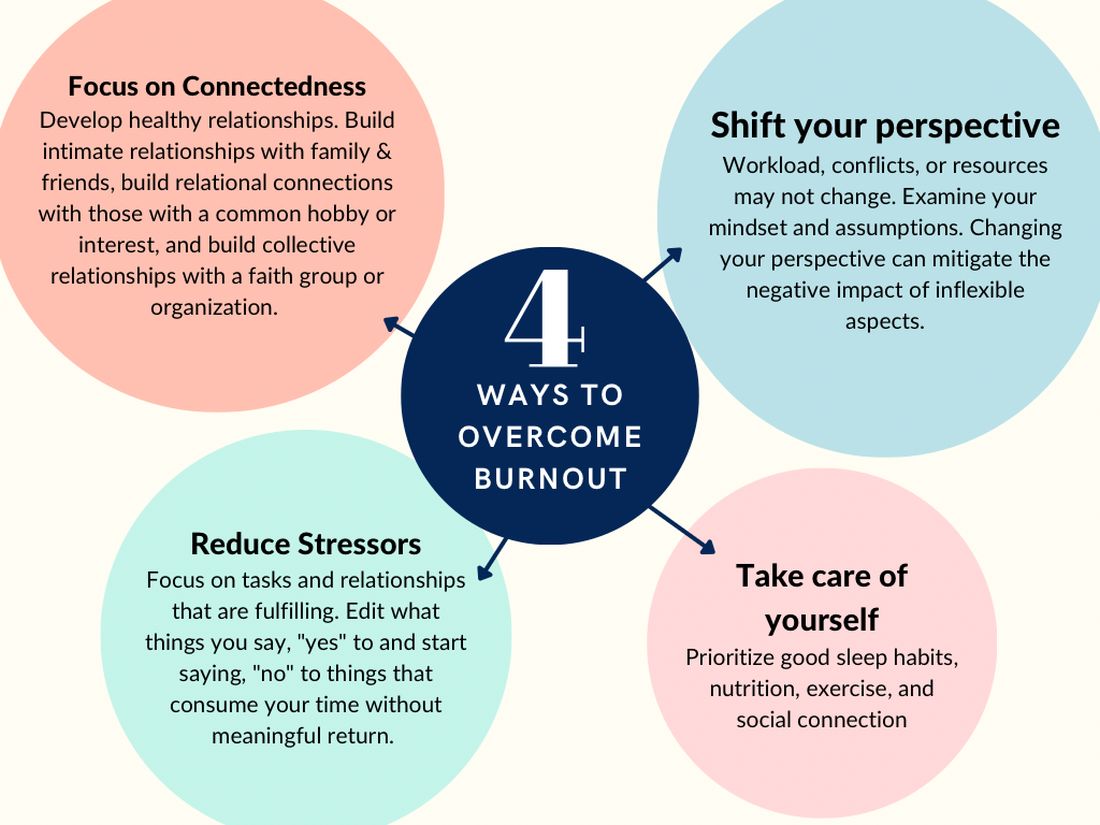

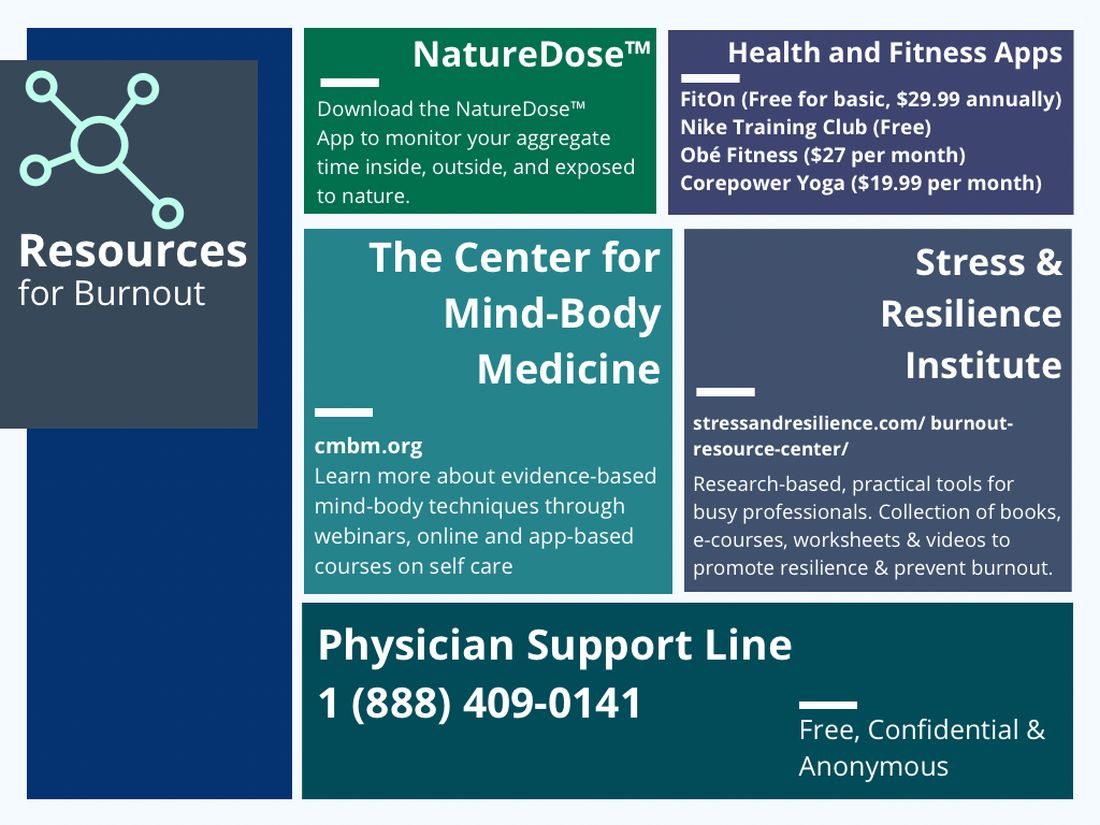

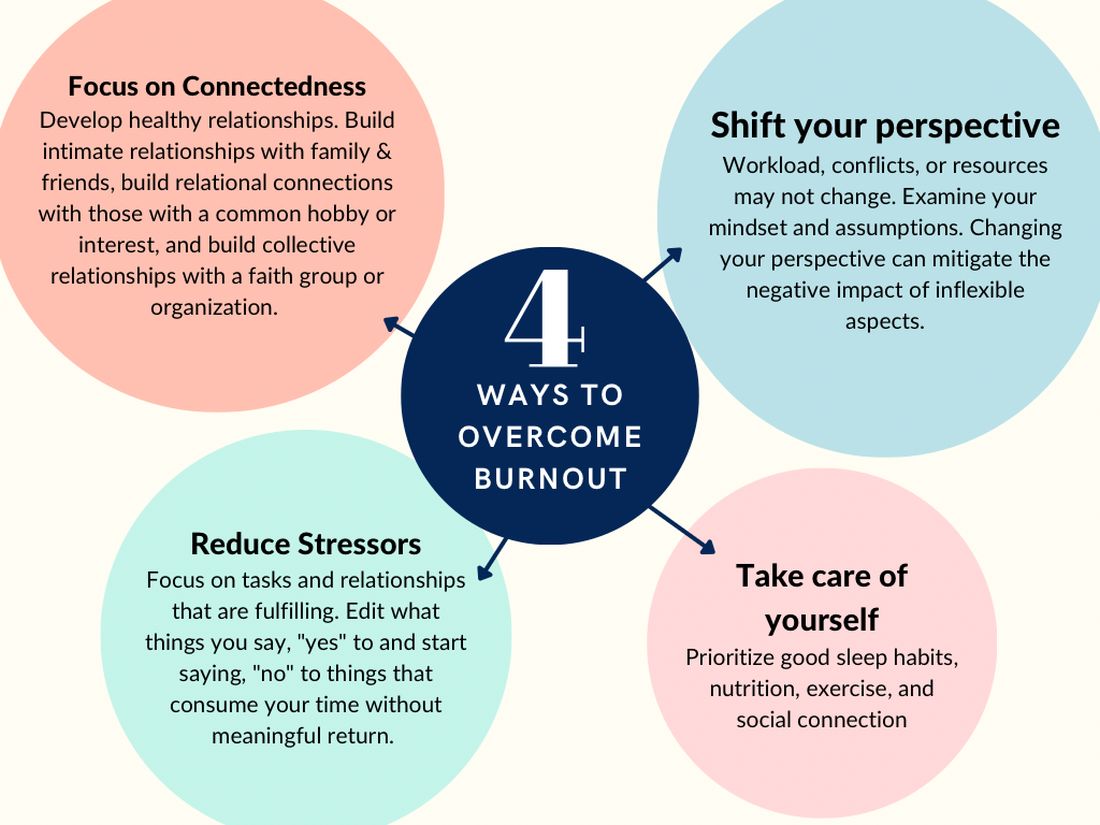

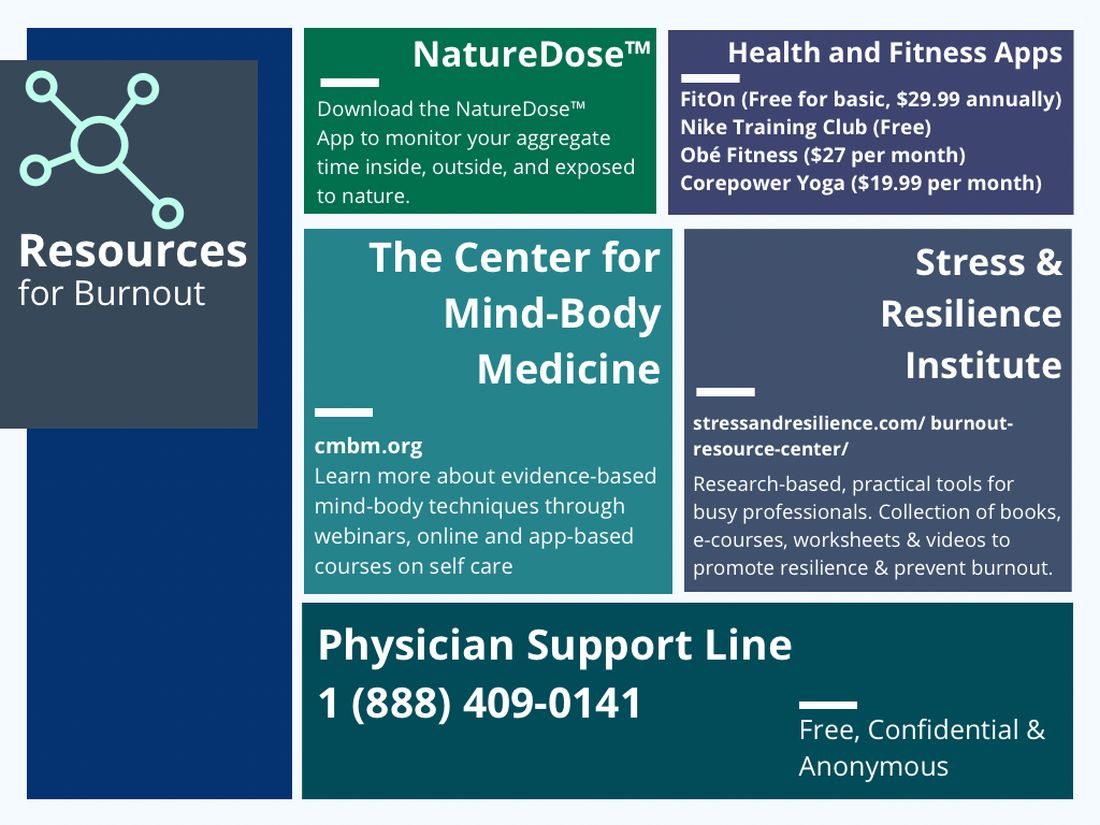

So, what can be done to prevent and treat burnout in new and transitioning gastroenterologists? The gastroenterologist may implement several strategies. It is essential for individuals to take responsibility for their well-being and to prioritize self-care by setting boundaries, practicing stress management techniques, and seeking support from colleagues and mental health professionals when needed.

According to Dave et al. (2020), engagement in self-care practices such as mindfulness may offer advantages to gastroenterologists’ well-being and improved patient care.11

Burnout is not due to an individuals’ need for more resiliency. Instead, it developed from a systemic overwhelming of a health system near its breaking point. Recognizing that by 2033, there is a projected shortage of nearly 140,000 physicians in the United States, the U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek H. Murthy, issued a crisis advisory.12 This advisory highlights the urgent need to address the health worker burnout crisis nationwide that outlined “whole of society” efforts.12 Key components of the advisory on building a thriving health workforce included empowering health care workers, changing policies, reducing administrative burdens, prioritizing connections, and investing in our workforce.12

Provide access to mental health services

Institutions and practices would greatly benefit from providing access to mental health services, counseling, educational opportunities, potential mental health days, and mentorship programs. While the literature indicates that both individual-focused and structural or organizational strategies can result in clinically meaningful reductions in burnout among physicians, a meta-analysis revealed that corporate-led initiatives resulted in larger successes.12,13 Physicians who received support and resources from their institutions report lower levels of burnout and higher job satisfaction.2,3

New strategies to select and develop physician leaders who motivate, inspire, and effectively manage physicians may result in positive job satisfaction while decreasing employee burnout. Therefore, increased awareness of the importance of frontline leadership well-being and professional fulfillment of physicians working for a large health care organization is necessary.13 Robust and continual leadership training can ensure the entire team’s well-being, longevity, and success.13

Addressing the root causes of systemic burnout is imperative. Leadership could streamline administrative processes, optimize electronic medical records, delegate prior authorizations, and ensure staffing levels are appropriate to meet patient care demands. In a survey by Rao et al. (2017), the authors found that physicians who reported high levels of administrative burden and work overload were more likely to experience burnout.14

Institutions and practices should promote a culture of work-life balance by implementing flexible scheduling, promoting time off and vacation time, and encouraging regular exercise and healthy habits. The current compensation structure disincentivizes physicians from taking time away from patient care – this can be re-designed. Community and support mitigate burnout. Therefore, institutions and practices will benefit by intentionally providing opportunities for social connection and team building.

In reflection of the U.S. Surgeon General’s call for all of society to be part of the solution, we are pleased to see the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) create mandatory 6 weeks of parental or caregiver leave for trainees.15 Continued positive pressure on overseeing agencies to minimize paperwork, preauthorizations, and non–value-added tasks to allow physicians to continue to provide medical services instead of documentation and auditing services would greatly positively impact all of health care. Therefore, communicating with legislators, policy makers, system leadership, and all health care societies to continue these improvements would be a wise use of time of resources.

In conclusion, burnout among new and transitioning gastroenterologists is a prevalent and concerning issue that can have severe consequences for both the individual and the health care system. Similar to the ergonomic considerations of being an endoscopist, A multifaceted approach to the well-being of all medical staff can help ensure the delivery of the highest quality patient care. By taking a proactive approach to preventing burnout, we can have a strong future for ourselves, our patients, and our profession.

Dr. Eboh is a gastroenterologist with Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C.; Dr. Jaeger is with Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Dallas. She is a gastroenterology fellow with Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia. Dr. Sears is clinical professor at Texas A&M University School of Medicine, and chief of gastroenterology at VA Central Texas Healthcare System. Dr. Sears owns GutGirlMD Consulting LLC, where she offers institutional and leadership coaching for physicians. Dr. Eboh on Instagram @Polyp.picker_EbohMD and on Twitter @PolypPicker_MD. Dr. Jaeger on Instagram @Doc.Tori.Fit and Twitter @DrToriJaeger. Dr. Sears is on Twitter @GutGirlMD.

References

1. Maslach C and Jackson S E. Maslach burnout inventory manual. Palo Alto, Calif: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1986.

2. Shanafelt TD et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Dec 12;90:1600-13.

3. Shanafelt TD et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Oct 8;172(18):1377-85.

4. Elta G. The challenges of being a female gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):441-7.

5. Gallup. Work and Workplace. 2023.

6. Gawande A. When doctors make mistakes. The New Yorker. 1999 Feb 1.

7. Buscarini E et al. Burnout among gastroenterologists: How to manage and prevent it. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020 Aug;8(7):832-4.

8. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 Nov 5;388(10057):2272-81.

9. Adarkwah CC et al. Burnout and work satisfaction are differentially associated in gastroenterologists in Germany. F1000Res. 2022 Mar 30;11:368. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.110296.3. eCollection 2022.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Apr;90(4):432-40.

11. Umakant D et al. Mindfulness in gastroenterology training and practice: A personal perspective. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020 Nov 4;13:497-502.

12. Murthy VH. Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 2022.

13. Panagioti M et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Feb 1;177(2):195-205.

14. Rao SK et al. The impact of administrative burden on academic physicians: Results of a hospital-wide physician survey. Acad Med. 2017 Feb;92(2):237-43.

15. ACGME. ACME Institutional Requirements 2021.

The field of gastroenterology can be challenging, both professionally and personally, leading to burnout, especially for new and transitioning gastroenterologists. Burnout is a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by prolonged or excessive stress.1 It is characterized by emotional fatigue, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.2,3 This condition can have severe consequences for physicians and their patients.

More than 50% of physicians report meeting the criteria for burnout, which is pervasive in all medical professions.3 Survey results of 7,288 U.S. physicians showed that burnout and dissatisfaction with work-life balance are significantly higher than among other working U.S. adults.3

The long and often irregular work hours expected of gastroenterologists significantly contribute to burnout within our field. The physically, intellectually, and technically demanding reality of managing complex patients and making high stakes decisions at all hours has far-reaching consequences.3 Most gastroenterologists work between 55 and 60 hours per week.4 This sharply contrasts the average 43-hour work week for full-time employees in the United States.5 Gastroenterologists may experience inaccurate perceptions of their commitment to patients, education, and their families based solely on time observed on each activity.4 Higher education and professional degrees usually protect against burnout.3 However, a degree in medicine (MD or DO) increases the burnout risk.3

New gastroenterologists are learning a wide range of intricate procedures and becoming proficient in diagnosing and managing gastrointestinal disorders. Extensive career demands often coincide with intense family-forming years, creating tension for a physician’s finite time and energy. The culture of medicine demanding “patients come first” while attempting to be fully human can sometimes feel irreconcilable, leading to feelings of inadequacy and anxiety.3 Gastroenterology training takes 3 years because of the complexity, danger, and need for thousands of procedures to gain proficiency and competence to recognize when complications occur. Oversight is ubiquitous during training, making this the ideal time to learn from mistakes and formulate lifelong habits of constant improvement. However, perfectionist tendencies and the Hippocratic Oath can create unrealistic self expectations.6 The risk of potential litigation, simply missing a diagnosis, or causing actual patient harm is never far from a proceduralist’s mind.

The diversity of gastroenterology requires high clinical knowledge, expertise, and emotional intelligence. Leading potentially intense end-of-life, cancer, fertility, and risk-factor discussions can be all-consuming. Keeping up with the latest research, treatments, and techniques in the field can be daunting. Furthermore, gastroenterologists spend many hours each day on electronic medical records. Constant re-documentation of interactions, seemingly endless prior authorizations, disability forms, referrals, and simply re-addressing patient and family concerns can feel low value. This uncompensated work also creates moral injury as it takes away from direct patient care.

Striking a work-life balance

New gastroenterologists are advised to find work-life balance. However, they are also plagued by the massive professional demands being constantly placed on them. The desire to find the mythical “balance” may create a mindset of significant sacrifices in their private lives as the only way to achieve professional successes.7 When gastroenterologists do not prioritize time for personal activities, including exercise, health checks, hobbies, rest, relaxation, family, and friends, they can get caught in a vicious cycle of continuing to feel poorly, resulting in overcompensating by working more in order to feel “accomplished.” The perfectionist pressure to maintain high productivity and patient satisfaction can also further contribute to burnout.

Gastroenterology burnout can severely affect physicians’ health status, job performance, and patient satisfaction.9 It may erode professionalism, negatively influence the quality of care, increase the risk of medical errors, and promote early retirement.3 Burnout may also correlate with adverse personal consequences for physicians, such as broken relationships, problematic alcohol use, and suicidal ideation.3 Physician burnout and professional satisfaction have strategic importance to health care organizations.10 Less burned-out physicians have patient panels with higher adherence and satisfaction with medical care.10 With more physicians becoming employees, there are opportunities for accountability of organizational leadership.10 Interestingly, healthy well-being or burnout is contagious from leaders to their teams.10 A 2015 study by Shanafelt et al. found that at the work unit level, 11% and 47% of the variation in burnout and satisfaction, correlated with the leader’s relative scores.10

So, what can be done to prevent and treat burnout in new and transitioning gastroenterologists? The gastroenterologist may implement several strategies. It is essential for individuals to take responsibility for their well-being and to prioritize self-care by setting boundaries, practicing stress management techniques, and seeking support from colleagues and mental health professionals when needed.

According to Dave et al. (2020), engagement in self-care practices such as mindfulness may offer advantages to gastroenterologists’ well-being and improved patient care.11

Burnout is not due to an individuals’ need for more resiliency. Instead, it developed from a systemic overwhelming of a health system near its breaking point. Recognizing that by 2033, there is a projected shortage of nearly 140,000 physicians in the United States, the U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek H. Murthy, issued a crisis advisory.12 This advisory highlights the urgent need to address the health worker burnout crisis nationwide that outlined “whole of society” efforts.12 Key components of the advisory on building a thriving health workforce included empowering health care workers, changing policies, reducing administrative burdens, prioritizing connections, and investing in our workforce.12

Provide access to mental health services

Institutions and practices would greatly benefit from providing access to mental health services, counseling, educational opportunities, potential mental health days, and mentorship programs. While the literature indicates that both individual-focused and structural or organizational strategies can result in clinically meaningful reductions in burnout among physicians, a meta-analysis revealed that corporate-led initiatives resulted in larger successes.12,13 Physicians who received support and resources from their institutions report lower levels of burnout and higher job satisfaction.2,3

New strategies to select and develop physician leaders who motivate, inspire, and effectively manage physicians may result in positive job satisfaction while decreasing employee burnout. Therefore, increased awareness of the importance of frontline leadership well-being and professional fulfillment of physicians working for a large health care organization is necessary.13 Robust and continual leadership training can ensure the entire team’s well-being, longevity, and success.13

Addressing the root causes of systemic burnout is imperative. Leadership could streamline administrative processes, optimize electronic medical records, delegate prior authorizations, and ensure staffing levels are appropriate to meet patient care demands. In a survey by Rao et al. (2017), the authors found that physicians who reported high levels of administrative burden and work overload were more likely to experience burnout.14

Institutions and practices should promote a culture of work-life balance by implementing flexible scheduling, promoting time off and vacation time, and encouraging regular exercise and healthy habits. The current compensation structure disincentivizes physicians from taking time away from patient care – this can be re-designed. Community and support mitigate burnout. Therefore, institutions and practices will benefit by intentionally providing opportunities for social connection and team building.

In reflection of the U.S. Surgeon General’s call for all of society to be part of the solution, we are pleased to see the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) create mandatory 6 weeks of parental or caregiver leave for trainees.15 Continued positive pressure on overseeing agencies to minimize paperwork, preauthorizations, and non–value-added tasks to allow physicians to continue to provide medical services instead of documentation and auditing services would greatly positively impact all of health care. Therefore, communicating with legislators, policy makers, system leadership, and all health care societies to continue these improvements would be a wise use of time of resources.

In conclusion, burnout among new and transitioning gastroenterologists is a prevalent and concerning issue that can have severe consequences for both the individual and the health care system. Similar to the ergonomic considerations of being an endoscopist, A multifaceted approach to the well-being of all medical staff can help ensure the delivery of the highest quality patient care. By taking a proactive approach to preventing burnout, we can have a strong future for ourselves, our patients, and our profession.

Dr. Eboh is a gastroenterologist with Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C.; Dr. Jaeger is with Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Dallas. She is a gastroenterology fellow with Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia. Dr. Sears is clinical professor at Texas A&M University School of Medicine, and chief of gastroenterology at VA Central Texas Healthcare System. Dr. Sears owns GutGirlMD Consulting LLC, where she offers institutional and leadership coaching for physicians. Dr. Eboh on Instagram @Polyp.picker_EbohMD and on Twitter @PolypPicker_MD. Dr. Jaeger on Instagram @Doc.Tori.Fit and Twitter @DrToriJaeger. Dr. Sears is on Twitter @GutGirlMD.

References

1. Maslach C and Jackson S E. Maslach burnout inventory manual. Palo Alto, Calif: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1986.

2. Shanafelt TD et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Dec 12;90:1600-13.

3. Shanafelt TD et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Oct 8;172(18):1377-85.

4. Elta G. The challenges of being a female gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):441-7.

5. Gallup. Work and Workplace. 2023.

6. Gawande A. When doctors make mistakes. The New Yorker. 1999 Feb 1.

7. Buscarini E et al. Burnout among gastroenterologists: How to manage and prevent it. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020 Aug;8(7):832-4.

8. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 Nov 5;388(10057):2272-81.

9. Adarkwah CC et al. Burnout and work satisfaction are differentially associated in gastroenterologists in Germany. F1000Res. 2022 Mar 30;11:368. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.110296.3. eCollection 2022.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Apr;90(4):432-40.

11. Umakant D et al. Mindfulness in gastroenterology training and practice: A personal perspective. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020 Nov 4;13:497-502.

12. Murthy VH. Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 2022.

13. Panagioti M et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Feb 1;177(2):195-205.

14. Rao SK et al. The impact of administrative burden on academic physicians: Results of a hospital-wide physician survey. Acad Med. 2017 Feb;92(2):237-43.

15. ACGME. ACME Institutional Requirements 2021.

The field of gastroenterology can be challenging, both professionally and personally, leading to burnout, especially for new and transitioning gastroenterologists. Burnout is a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by prolonged or excessive stress.1 It is characterized by emotional fatigue, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.2,3 This condition can have severe consequences for physicians and their patients.

More than 50% of physicians report meeting the criteria for burnout, which is pervasive in all medical professions.3 Survey results of 7,288 U.S. physicians showed that burnout and dissatisfaction with work-life balance are significantly higher than among other working U.S. adults.3

The long and often irregular work hours expected of gastroenterologists significantly contribute to burnout within our field. The physically, intellectually, and technically demanding reality of managing complex patients and making high stakes decisions at all hours has far-reaching consequences.3 Most gastroenterologists work between 55 and 60 hours per week.4 This sharply contrasts the average 43-hour work week for full-time employees in the United States.5 Gastroenterologists may experience inaccurate perceptions of their commitment to patients, education, and their families based solely on time observed on each activity.4 Higher education and professional degrees usually protect against burnout.3 However, a degree in medicine (MD or DO) increases the burnout risk.3

New gastroenterologists are learning a wide range of intricate procedures and becoming proficient in diagnosing and managing gastrointestinal disorders. Extensive career demands often coincide with intense family-forming years, creating tension for a physician’s finite time and energy. The culture of medicine demanding “patients come first” while attempting to be fully human can sometimes feel irreconcilable, leading to feelings of inadequacy and anxiety.3 Gastroenterology training takes 3 years because of the complexity, danger, and need for thousands of procedures to gain proficiency and competence to recognize when complications occur. Oversight is ubiquitous during training, making this the ideal time to learn from mistakes and formulate lifelong habits of constant improvement. However, perfectionist tendencies and the Hippocratic Oath can create unrealistic self expectations.6 The risk of potential litigation, simply missing a diagnosis, or causing actual patient harm is never far from a proceduralist’s mind.

The diversity of gastroenterology requires high clinical knowledge, expertise, and emotional intelligence. Leading potentially intense end-of-life, cancer, fertility, and risk-factor discussions can be all-consuming. Keeping up with the latest research, treatments, and techniques in the field can be daunting. Furthermore, gastroenterologists spend many hours each day on electronic medical records. Constant re-documentation of interactions, seemingly endless prior authorizations, disability forms, referrals, and simply re-addressing patient and family concerns can feel low value. This uncompensated work also creates moral injury as it takes away from direct patient care.

Striking a work-life balance

New gastroenterologists are advised to find work-life balance. However, they are also plagued by the massive professional demands being constantly placed on them. The desire to find the mythical “balance” may create a mindset of significant sacrifices in their private lives as the only way to achieve professional successes.7 When gastroenterologists do not prioritize time for personal activities, including exercise, health checks, hobbies, rest, relaxation, family, and friends, they can get caught in a vicious cycle of continuing to feel poorly, resulting in overcompensating by working more in order to feel “accomplished.” The perfectionist pressure to maintain high productivity and patient satisfaction can also further contribute to burnout.

Gastroenterology burnout can severely affect physicians’ health status, job performance, and patient satisfaction.9 It may erode professionalism, negatively influence the quality of care, increase the risk of medical errors, and promote early retirement.3 Burnout may also correlate with adverse personal consequences for physicians, such as broken relationships, problematic alcohol use, and suicidal ideation.3 Physician burnout and professional satisfaction have strategic importance to health care organizations.10 Less burned-out physicians have patient panels with higher adherence and satisfaction with medical care.10 With more physicians becoming employees, there are opportunities for accountability of organizational leadership.10 Interestingly, healthy well-being or burnout is contagious from leaders to their teams.10 A 2015 study by Shanafelt et al. found that at the work unit level, 11% and 47% of the variation in burnout and satisfaction, correlated with the leader’s relative scores.10

So, what can be done to prevent and treat burnout in new and transitioning gastroenterologists? The gastroenterologist may implement several strategies. It is essential for individuals to take responsibility for their well-being and to prioritize self-care by setting boundaries, practicing stress management techniques, and seeking support from colleagues and mental health professionals when needed.

According to Dave et al. (2020), engagement in self-care practices such as mindfulness may offer advantages to gastroenterologists’ well-being and improved patient care.11

Burnout is not due to an individuals’ need for more resiliency. Instead, it developed from a systemic overwhelming of a health system near its breaking point. Recognizing that by 2033, there is a projected shortage of nearly 140,000 physicians in the United States, the U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek H. Murthy, issued a crisis advisory.12 This advisory highlights the urgent need to address the health worker burnout crisis nationwide that outlined “whole of society” efforts.12 Key components of the advisory on building a thriving health workforce included empowering health care workers, changing policies, reducing administrative burdens, prioritizing connections, and investing in our workforce.12

Provide access to mental health services

Institutions and practices would greatly benefit from providing access to mental health services, counseling, educational opportunities, potential mental health days, and mentorship programs. While the literature indicates that both individual-focused and structural or organizational strategies can result in clinically meaningful reductions in burnout among physicians, a meta-analysis revealed that corporate-led initiatives resulted in larger successes.12,13 Physicians who received support and resources from their institutions report lower levels of burnout and higher job satisfaction.2,3

New strategies to select and develop physician leaders who motivate, inspire, and effectively manage physicians may result in positive job satisfaction while decreasing employee burnout. Therefore, increased awareness of the importance of frontline leadership well-being and professional fulfillment of physicians working for a large health care organization is necessary.13 Robust and continual leadership training can ensure the entire team’s well-being, longevity, and success.13

Addressing the root causes of systemic burnout is imperative. Leadership could streamline administrative processes, optimize electronic medical records, delegate prior authorizations, and ensure staffing levels are appropriate to meet patient care demands. In a survey by Rao et al. (2017), the authors found that physicians who reported high levels of administrative burden and work overload were more likely to experience burnout.14

Institutions and practices should promote a culture of work-life balance by implementing flexible scheduling, promoting time off and vacation time, and encouraging regular exercise and healthy habits. The current compensation structure disincentivizes physicians from taking time away from patient care – this can be re-designed. Community and support mitigate burnout. Therefore, institutions and practices will benefit by intentionally providing opportunities for social connection and team building.

In reflection of the U.S. Surgeon General’s call for all of society to be part of the solution, we are pleased to see the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) create mandatory 6 weeks of parental or caregiver leave for trainees.15 Continued positive pressure on overseeing agencies to minimize paperwork, preauthorizations, and non–value-added tasks to allow physicians to continue to provide medical services instead of documentation and auditing services would greatly positively impact all of health care. Therefore, communicating with legislators, policy makers, system leadership, and all health care societies to continue these improvements would be a wise use of time of resources.

In conclusion, burnout among new and transitioning gastroenterologists is a prevalent and concerning issue that can have severe consequences for both the individual and the health care system. Similar to the ergonomic considerations of being an endoscopist, A multifaceted approach to the well-being of all medical staff can help ensure the delivery of the highest quality patient care. By taking a proactive approach to preventing burnout, we can have a strong future for ourselves, our patients, and our profession.

Dr. Eboh is a gastroenterologist with Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C.; Dr. Jaeger is with Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Dallas. She is a gastroenterology fellow with Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia. Dr. Sears is clinical professor at Texas A&M University School of Medicine, and chief of gastroenterology at VA Central Texas Healthcare System. Dr. Sears owns GutGirlMD Consulting LLC, where she offers institutional and leadership coaching for physicians. Dr. Eboh on Instagram @Polyp.picker_EbohMD and on Twitter @PolypPicker_MD. Dr. Jaeger on Instagram @Doc.Tori.Fit and Twitter @DrToriJaeger. Dr. Sears is on Twitter @GutGirlMD.

References

1. Maslach C and Jackson S E. Maslach burnout inventory manual. Palo Alto, Calif: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1986.

2. Shanafelt TD et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Dec 12;90:1600-13.

3. Shanafelt TD et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Oct 8;172(18):1377-85.

4. Elta G. The challenges of being a female gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):441-7.

5. Gallup. Work and Workplace. 2023.

6. Gawande A. When doctors make mistakes. The New Yorker. 1999 Feb 1.

7. Buscarini E et al. Burnout among gastroenterologists: How to manage and prevent it. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020 Aug;8(7):832-4.

8. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 Nov 5;388(10057):2272-81.

9. Adarkwah CC et al. Burnout and work satisfaction are differentially associated in gastroenterologists in Germany. F1000Res. 2022 Mar 30;11:368. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.110296.3. eCollection 2022.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Apr;90(4):432-40.

11. Umakant D et al. Mindfulness in gastroenterology training and practice: A personal perspective. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020 Nov 4;13:497-502.

12. Murthy VH. Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 2022.

13. Panagioti M et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Feb 1;177(2):195-205.

14. Rao SK et al. The impact of administrative burden on academic physicians: Results of a hospital-wide physician survey. Acad Med. 2017 Feb;92(2):237-43.

15. ACGME. ACME Institutional Requirements 2021.