User login

Cannabis use in pregnancy and lactation: A changing landscape

National survey data from 2007-2012 of more than 93,000 pregnant women suggest that around 7% of pregnant respondents reported any cannabis use in the last 2-12 months; of those, 16% reported daily or almost daily use. Among pregnant past-year users in the same survey, 70% perceived slight or no risk of harm from cannabis use 1-2 times a week in pregnancy.1

Data from the Kaiser Northern California health plan involving more than 279,000 pregnancies followed during 2009-2016 suggest that there has been a significant upward trend in use of cannabis during pregnancy, from 4% to 7%, as reported by the mother and/or identified by routine urine screening. The highest prevalence in that study was seen among 18- to 24-year-old pregnant women, increasing from 13% to 22% over the 7-year study period. Importantly, more than 50% of cannabis users in the sample were identified by toxicology screening alone.2,3 Common reasons given for use of cannabis in pregnancy include anxiety, pain, and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.4

With respect to adverse perinatal outcomes, several case-control studies have examined risks for major birth defects with maternal self-report of cannabis use. Some have noted very modest increased risks for selected major birth defects (odds ratios less than 2); however, data still are very limited.5,6

A number of prospective studies have addressed risks of preterm birth and growth restriction, accounting for mother’s concomitant tobacco use.7-11 Some of these studies have suggested about a twofold to threefold increased risk for preterm delivery and an increased risk for reduced birth weight – particularly with heavier or regular cannabis use – but study findings have not been entirely consistent.

Given its psychoactive properties, there has been high interest in understanding whether there are any short- or long-term neurodevelopmental effects on children prenatally exposed to cannabis. These outcomes have been studied in two small older cohorts in the United States and Canada and one more recent cohort in the Netherlands.12-15 Deficits in several measures of cognition and behavior were noted in follow-up of those children from birth to adulthood. However, it is unclear to what extent these findings may have been influenced by heredity, environment, or other factors.

There have been limitations in almost all studies published to date, including small sample sizes, no biomarker validation of maternal report of dose and gestational timing of cannabis use, and lack of detailed data on common coexposures, such as alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. In addition, newer studies of pregnancy outcomes in women who use currently available cannabis products are needed, given the substantial increase in the potency of cannabis used today, compared with that of 20 years ago. For example, the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in commonly cultivated marijuana plants has increased threefold from 4% to 12% between 1995 and 2014.16

There are very limited data on the presence of cannabis in breast milk and the potential effects of exposure to THC and other metabolites for breastfed infants. However, two recent studies have demonstrated there are low but measurable levels of some cannabis metabolites in breast milk.17-18 Further work is needed to determine if these metabolites accumulate in milk and if at a given dose and age of the breastfed infant, there are any growth, neurodevelopmental, or other clinically important adverse effects.

Related questions, such as potential differences in the effects of exposure during pregnancy or lactation based on the route of administration (edible vs. inhaled) and the use of cannabidiol (CBD) products, have not been studied.

At the present time, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women who are pregnant or contemplating pregnancy be encouraged to discontinue marijuana use. With respect to lactation and breastfeeding, ACOG concludes there are insufficient data to evaluate the effects on infants, and in the absence of such data, marijuana use is discouraged. Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends women of childbearing age abstain from marijuana use while pregnant or breastfeeding because of potential adverse consequences to the fetus, infant, or child.

In August 2019, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory regarding potential harm to developing brains from the use of marijuana during pregnancy and lactation. The Food and Drug Administration issued a similar statement in October 2019 strongly advising against the use of CBD, THC, and marijuana in any form during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Aug;213(2):201.e1-10.

2. JAMA. 2017 Dec 26;318(24):2490-1.

3. JAMA. 2017 Jan 10;317(2):207-9.

4. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009 Nov;15(4)242-6.

5. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014 Sep; 28(5): 424-33.

6. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007 Jan;70(1):7-18.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Aug 15;146(8):992-4.

8. Clin Perinatol. 1991 Mar;18(1):77-91.

9. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Dec;124(6):986-93.

10. Pediatr Res. 2012 Feb;71(2):215-9.

11. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;62:77-86.

12. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1987 Jan-Feb;9(1):1-7.

13. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994 Mar-Apr;16(2):169-75.

14. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 15;79(12):971-9.

15. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb;182:133-51.

16. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 1;79(7):613-9.

17. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):783-8.

18. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep;142(3):e20181076.

National survey data from 2007-2012 of more than 93,000 pregnant women suggest that around 7% of pregnant respondents reported any cannabis use in the last 2-12 months; of those, 16% reported daily or almost daily use. Among pregnant past-year users in the same survey, 70% perceived slight or no risk of harm from cannabis use 1-2 times a week in pregnancy.1

Data from the Kaiser Northern California health plan involving more than 279,000 pregnancies followed during 2009-2016 suggest that there has been a significant upward trend in use of cannabis during pregnancy, from 4% to 7%, as reported by the mother and/or identified by routine urine screening. The highest prevalence in that study was seen among 18- to 24-year-old pregnant women, increasing from 13% to 22% over the 7-year study period. Importantly, more than 50% of cannabis users in the sample were identified by toxicology screening alone.2,3 Common reasons given for use of cannabis in pregnancy include anxiety, pain, and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.4

With respect to adverse perinatal outcomes, several case-control studies have examined risks for major birth defects with maternal self-report of cannabis use. Some have noted very modest increased risks for selected major birth defects (odds ratios less than 2); however, data still are very limited.5,6

A number of prospective studies have addressed risks of preterm birth and growth restriction, accounting for mother’s concomitant tobacco use.7-11 Some of these studies have suggested about a twofold to threefold increased risk for preterm delivery and an increased risk for reduced birth weight – particularly with heavier or regular cannabis use – but study findings have not been entirely consistent.

Given its psychoactive properties, there has been high interest in understanding whether there are any short- or long-term neurodevelopmental effects on children prenatally exposed to cannabis. These outcomes have been studied in two small older cohorts in the United States and Canada and one more recent cohort in the Netherlands.12-15 Deficits in several measures of cognition and behavior were noted in follow-up of those children from birth to adulthood. However, it is unclear to what extent these findings may have been influenced by heredity, environment, or other factors.

There have been limitations in almost all studies published to date, including small sample sizes, no biomarker validation of maternal report of dose and gestational timing of cannabis use, and lack of detailed data on common coexposures, such as alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. In addition, newer studies of pregnancy outcomes in women who use currently available cannabis products are needed, given the substantial increase in the potency of cannabis used today, compared with that of 20 years ago. For example, the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in commonly cultivated marijuana plants has increased threefold from 4% to 12% between 1995 and 2014.16

There are very limited data on the presence of cannabis in breast milk and the potential effects of exposure to THC and other metabolites for breastfed infants. However, two recent studies have demonstrated there are low but measurable levels of some cannabis metabolites in breast milk.17-18 Further work is needed to determine if these metabolites accumulate in milk and if at a given dose and age of the breastfed infant, there are any growth, neurodevelopmental, or other clinically important adverse effects.

Related questions, such as potential differences in the effects of exposure during pregnancy or lactation based on the route of administration (edible vs. inhaled) and the use of cannabidiol (CBD) products, have not been studied.

At the present time, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women who are pregnant or contemplating pregnancy be encouraged to discontinue marijuana use. With respect to lactation and breastfeeding, ACOG concludes there are insufficient data to evaluate the effects on infants, and in the absence of such data, marijuana use is discouraged. Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends women of childbearing age abstain from marijuana use while pregnant or breastfeeding because of potential adverse consequences to the fetus, infant, or child.

In August 2019, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory regarding potential harm to developing brains from the use of marijuana during pregnancy and lactation. The Food and Drug Administration issued a similar statement in October 2019 strongly advising against the use of CBD, THC, and marijuana in any form during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Aug;213(2):201.e1-10.

2. JAMA. 2017 Dec 26;318(24):2490-1.

3. JAMA. 2017 Jan 10;317(2):207-9.

4. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009 Nov;15(4)242-6.

5. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014 Sep; 28(5): 424-33.

6. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007 Jan;70(1):7-18.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Aug 15;146(8):992-4.

8. Clin Perinatol. 1991 Mar;18(1):77-91.

9. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Dec;124(6):986-93.

10. Pediatr Res. 2012 Feb;71(2):215-9.

11. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;62:77-86.

12. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1987 Jan-Feb;9(1):1-7.

13. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994 Mar-Apr;16(2):169-75.

14. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 15;79(12):971-9.

15. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb;182:133-51.

16. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 1;79(7):613-9.

17. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):783-8.

18. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep;142(3):e20181076.

National survey data from 2007-2012 of more than 93,000 pregnant women suggest that around 7% of pregnant respondents reported any cannabis use in the last 2-12 months; of those, 16% reported daily or almost daily use. Among pregnant past-year users in the same survey, 70% perceived slight or no risk of harm from cannabis use 1-2 times a week in pregnancy.1

Data from the Kaiser Northern California health plan involving more than 279,000 pregnancies followed during 2009-2016 suggest that there has been a significant upward trend in use of cannabis during pregnancy, from 4% to 7%, as reported by the mother and/or identified by routine urine screening. The highest prevalence in that study was seen among 18- to 24-year-old pregnant women, increasing from 13% to 22% over the 7-year study period. Importantly, more than 50% of cannabis users in the sample were identified by toxicology screening alone.2,3 Common reasons given for use of cannabis in pregnancy include anxiety, pain, and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.4

With respect to adverse perinatal outcomes, several case-control studies have examined risks for major birth defects with maternal self-report of cannabis use. Some have noted very modest increased risks for selected major birth defects (odds ratios less than 2); however, data still are very limited.5,6

A number of prospective studies have addressed risks of preterm birth and growth restriction, accounting for mother’s concomitant tobacco use.7-11 Some of these studies have suggested about a twofold to threefold increased risk for preterm delivery and an increased risk for reduced birth weight – particularly with heavier or regular cannabis use – but study findings have not been entirely consistent.

Given its psychoactive properties, there has been high interest in understanding whether there are any short- or long-term neurodevelopmental effects on children prenatally exposed to cannabis. These outcomes have been studied in two small older cohorts in the United States and Canada and one more recent cohort in the Netherlands.12-15 Deficits in several measures of cognition and behavior were noted in follow-up of those children from birth to adulthood. However, it is unclear to what extent these findings may have been influenced by heredity, environment, or other factors.

There have been limitations in almost all studies published to date, including small sample sizes, no biomarker validation of maternal report of dose and gestational timing of cannabis use, and lack of detailed data on common coexposures, such as alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. In addition, newer studies of pregnancy outcomes in women who use currently available cannabis products are needed, given the substantial increase in the potency of cannabis used today, compared with that of 20 years ago. For example, the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in commonly cultivated marijuana plants has increased threefold from 4% to 12% between 1995 and 2014.16

There are very limited data on the presence of cannabis in breast milk and the potential effects of exposure to THC and other metabolites for breastfed infants. However, two recent studies have demonstrated there are low but measurable levels of some cannabis metabolites in breast milk.17-18 Further work is needed to determine if these metabolites accumulate in milk and if at a given dose and age of the breastfed infant, there are any growth, neurodevelopmental, or other clinically important adverse effects.

Related questions, such as potential differences in the effects of exposure during pregnancy or lactation based on the route of administration (edible vs. inhaled) and the use of cannabidiol (CBD) products, have not been studied.

At the present time, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women who are pregnant or contemplating pregnancy be encouraged to discontinue marijuana use. With respect to lactation and breastfeeding, ACOG concludes there are insufficient data to evaluate the effects on infants, and in the absence of such data, marijuana use is discouraged. Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends women of childbearing age abstain from marijuana use while pregnant or breastfeeding because of potential adverse consequences to the fetus, infant, or child.

In August 2019, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory regarding potential harm to developing brains from the use of marijuana during pregnancy and lactation. The Food and Drug Administration issued a similar statement in October 2019 strongly advising against the use of CBD, THC, and marijuana in any form during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Aug;213(2):201.e1-10.

2. JAMA. 2017 Dec 26;318(24):2490-1.

3. JAMA. 2017 Jan 10;317(2):207-9.

4. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009 Nov;15(4)242-6.

5. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014 Sep; 28(5): 424-33.

6. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007 Jan;70(1):7-18.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Aug 15;146(8):992-4.

8. Clin Perinatol. 1991 Mar;18(1):77-91.

9. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Dec;124(6):986-93.

10. Pediatr Res. 2012 Feb;71(2):215-9.

11. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;62:77-86.

12. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1987 Jan-Feb;9(1):1-7.

13. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994 Mar-Apr;16(2):169-75.

14. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 15;79(12):971-9.

15. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb;182:133-51.

16. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 1;79(7):613-9.

17. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):783-8.

18. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep;142(3):e20181076.

AED exposure from breastfeeding appears to be low

, according to a study published online ahead of print Dec. 30, 2019, in JAMA Neurology. The results may explain why previous research failed to find adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding in infants whose mothers are undergoing AED treatment, said the authors.

“The results of this study add support to the general safety of breastfeeding by mothers with epilepsy who take AEDs,” wrote Angela K. Birnbaum, PhD, professor of experimental and clinical pharmacology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Investigators measured infants’ blood AED concentrations

To date, medical consensus about the safety of breastfeeding while the mother is taking AEDs has been elusive. Researchers have investigated breast milk concentrations of AEDs as surrogate markers of AED concentrations in children. Breast milk concentrations, however, do not account for differences in infant pharmacokinetic processes and thus could misrepresent AED exposure in children through breastfeeding.

Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues sought to measure blood concentrations of AEDs in mothers with epilepsy and the infants that they breastfed to achieve an objective measure of AED exposure through breastfeeding. They examined data collected from December 2012 to October 2016 in the prospective Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study. Eligible participants were pregnant women with epilepsy between the ages of 14 and 45 years whose pregnancies had progressed to fewer than 20 weeks’ gestational age and who had IQ scores greater than 70 points. Participants were followed up throughout pregnancy and for 9 months post partum. Children were enrolled at birth.

The investigators collected blood samples from mothers and infants who were breastfed at the same visit, which occurred at between 5 and 20 weeks after birth. The volume of ingested breast milk delivered through graduated feeding bottles each day and the total duration of all daily breastfeeding sessions were recorded. For infants, blood samples were collected from the plantar surface of the heel and stored as dried blood spots on filter paper. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of infant-to-mother concentration of AEDs. Concentrations of AEDs in infants at less than the lower limit of quantification were assessed as half of the lower limit.

Exposure in utero may be greater than exposure through breast milk

In all, the researchers enrolled 351 pregnant women with epilepsy into the study and collected data on 345 infants. Two hundred twenty-two (64.3%) of the infants were breastfed, and 146 (42.3%) had AED concentrations available. After excluding outliers and mothers with missing concentration data, Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues included 164 matching infant-mother concentration pairs in their analysis (i.e., of 135 mothers and 138 infants). Approximately 52% of the infants were female, and their median age at blood collection was 13 weeks. The mothers’ median age was 32 years. About 82% of mothers were receiving monotherapy. The investigators found no demographic differences between groups of mothers taking various AEDs.

Sixty-eight infants (49.3%) had AED concentrations that were less than the lower limit of quantification. AED concentration was not greater than the lower limit of quantification for any infants breastfed by mothers taking carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, or topiramate. Most levetiracetam (71.4%) and zonisamide (60.0%) concentrations in infants were less than the lower limit of quantification. Most lamotrigine concentrations in infants (88.6%) were greater than the lower limit of quantification.

The median percentage of infant-to-mother concentration was 28.9% for lamotrigine, 5.3% for levetiracetam, 44.2% for zonisamide, 5.7% for carbamazepine, 5.4% for carbamazepine epoxide, 0.3% for oxcarbazepine, 17.2% for topiramate, and 21.4% for valproic acid. Multiple linear regression models indicated that maternal concentration was significantly associated with lamotrigine concentration in infants, but not levetiracetam concentration in infants.

“Prior studies at delivery demonstrated that umbilical-cord concentrations were nearly equal to maternal concentrations, suggesting extensive placental passage to the fetus,” wrote Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues. “Therefore, the amount of AED exposure via breast milk is likely substantially lower than fetal exposure during pregnancy and appears unlikely to confer any additional risks beyond those that might be associated with exposure in pregnancy, especially given prior studies showing no adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding while taking AEDs.”

The investigators acknowledged several limitations of their research, including the observational design of the MONEAD study. The amount of AED in participants’ breast milk is unknown, and the investigators could not calculate relative infant dosages. Only one blood sample was taken per infant, thus the results may not reflect infants’ total exposure over time.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Child Health and Development funded the research. The authors reported receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Birnbaum AK et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4443.

, according to a study published online ahead of print Dec. 30, 2019, in JAMA Neurology. The results may explain why previous research failed to find adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding in infants whose mothers are undergoing AED treatment, said the authors.

“The results of this study add support to the general safety of breastfeeding by mothers with epilepsy who take AEDs,” wrote Angela K. Birnbaum, PhD, professor of experimental and clinical pharmacology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Investigators measured infants’ blood AED concentrations

To date, medical consensus about the safety of breastfeeding while the mother is taking AEDs has been elusive. Researchers have investigated breast milk concentrations of AEDs as surrogate markers of AED concentrations in children. Breast milk concentrations, however, do not account for differences in infant pharmacokinetic processes and thus could misrepresent AED exposure in children through breastfeeding.

Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues sought to measure blood concentrations of AEDs in mothers with epilepsy and the infants that they breastfed to achieve an objective measure of AED exposure through breastfeeding. They examined data collected from December 2012 to October 2016 in the prospective Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study. Eligible participants were pregnant women with epilepsy between the ages of 14 and 45 years whose pregnancies had progressed to fewer than 20 weeks’ gestational age and who had IQ scores greater than 70 points. Participants were followed up throughout pregnancy and for 9 months post partum. Children were enrolled at birth.

The investigators collected blood samples from mothers and infants who were breastfed at the same visit, which occurred at between 5 and 20 weeks after birth. The volume of ingested breast milk delivered through graduated feeding bottles each day and the total duration of all daily breastfeeding sessions were recorded. For infants, blood samples were collected from the plantar surface of the heel and stored as dried blood spots on filter paper. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of infant-to-mother concentration of AEDs. Concentrations of AEDs in infants at less than the lower limit of quantification were assessed as half of the lower limit.

Exposure in utero may be greater than exposure through breast milk

In all, the researchers enrolled 351 pregnant women with epilepsy into the study and collected data on 345 infants. Two hundred twenty-two (64.3%) of the infants were breastfed, and 146 (42.3%) had AED concentrations available. After excluding outliers and mothers with missing concentration data, Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues included 164 matching infant-mother concentration pairs in their analysis (i.e., of 135 mothers and 138 infants). Approximately 52% of the infants were female, and their median age at blood collection was 13 weeks. The mothers’ median age was 32 years. About 82% of mothers were receiving monotherapy. The investigators found no demographic differences between groups of mothers taking various AEDs.

Sixty-eight infants (49.3%) had AED concentrations that were less than the lower limit of quantification. AED concentration was not greater than the lower limit of quantification for any infants breastfed by mothers taking carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, or topiramate. Most levetiracetam (71.4%) and zonisamide (60.0%) concentrations in infants were less than the lower limit of quantification. Most lamotrigine concentrations in infants (88.6%) were greater than the lower limit of quantification.

The median percentage of infant-to-mother concentration was 28.9% for lamotrigine, 5.3% for levetiracetam, 44.2% for zonisamide, 5.7% for carbamazepine, 5.4% for carbamazepine epoxide, 0.3% for oxcarbazepine, 17.2% for topiramate, and 21.4% for valproic acid. Multiple linear regression models indicated that maternal concentration was significantly associated with lamotrigine concentration in infants, but not levetiracetam concentration in infants.

“Prior studies at delivery demonstrated that umbilical-cord concentrations were nearly equal to maternal concentrations, suggesting extensive placental passage to the fetus,” wrote Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues. “Therefore, the amount of AED exposure via breast milk is likely substantially lower than fetal exposure during pregnancy and appears unlikely to confer any additional risks beyond those that might be associated with exposure in pregnancy, especially given prior studies showing no adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding while taking AEDs.”

The investigators acknowledged several limitations of their research, including the observational design of the MONEAD study. The amount of AED in participants’ breast milk is unknown, and the investigators could not calculate relative infant dosages. Only one blood sample was taken per infant, thus the results may not reflect infants’ total exposure over time.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Child Health and Development funded the research. The authors reported receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Birnbaum AK et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4443.

, according to a study published online ahead of print Dec. 30, 2019, in JAMA Neurology. The results may explain why previous research failed to find adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding in infants whose mothers are undergoing AED treatment, said the authors.

“The results of this study add support to the general safety of breastfeeding by mothers with epilepsy who take AEDs,” wrote Angela K. Birnbaum, PhD, professor of experimental and clinical pharmacology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Investigators measured infants’ blood AED concentrations

To date, medical consensus about the safety of breastfeeding while the mother is taking AEDs has been elusive. Researchers have investigated breast milk concentrations of AEDs as surrogate markers of AED concentrations in children. Breast milk concentrations, however, do not account for differences in infant pharmacokinetic processes and thus could misrepresent AED exposure in children through breastfeeding.

Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues sought to measure blood concentrations of AEDs in mothers with epilepsy and the infants that they breastfed to achieve an objective measure of AED exposure through breastfeeding. They examined data collected from December 2012 to October 2016 in the prospective Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study. Eligible participants were pregnant women with epilepsy between the ages of 14 and 45 years whose pregnancies had progressed to fewer than 20 weeks’ gestational age and who had IQ scores greater than 70 points. Participants were followed up throughout pregnancy and for 9 months post partum. Children were enrolled at birth.

The investigators collected blood samples from mothers and infants who were breastfed at the same visit, which occurred at between 5 and 20 weeks after birth. The volume of ingested breast milk delivered through graduated feeding bottles each day and the total duration of all daily breastfeeding sessions were recorded. For infants, blood samples were collected from the plantar surface of the heel and stored as dried blood spots on filter paper. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of infant-to-mother concentration of AEDs. Concentrations of AEDs in infants at less than the lower limit of quantification were assessed as half of the lower limit.

Exposure in utero may be greater than exposure through breast milk

In all, the researchers enrolled 351 pregnant women with epilepsy into the study and collected data on 345 infants. Two hundred twenty-two (64.3%) of the infants were breastfed, and 146 (42.3%) had AED concentrations available. After excluding outliers and mothers with missing concentration data, Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues included 164 matching infant-mother concentration pairs in their analysis (i.e., of 135 mothers and 138 infants). Approximately 52% of the infants were female, and their median age at blood collection was 13 weeks. The mothers’ median age was 32 years. About 82% of mothers were receiving monotherapy. The investigators found no demographic differences between groups of mothers taking various AEDs.

Sixty-eight infants (49.3%) had AED concentrations that were less than the lower limit of quantification. AED concentration was not greater than the lower limit of quantification for any infants breastfed by mothers taking carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, or topiramate. Most levetiracetam (71.4%) and zonisamide (60.0%) concentrations in infants were less than the lower limit of quantification. Most lamotrigine concentrations in infants (88.6%) were greater than the lower limit of quantification.

The median percentage of infant-to-mother concentration was 28.9% for lamotrigine, 5.3% for levetiracetam, 44.2% for zonisamide, 5.7% for carbamazepine, 5.4% for carbamazepine epoxide, 0.3% for oxcarbazepine, 17.2% for topiramate, and 21.4% for valproic acid. Multiple linear regression models indicated that maternal concentration was significantly associated with lamotrigine concentration in infants, but not levetiracetam concentration in infants.

“Prior studies at delivery demonstrated that umbilical-cord concentrations were nearly equal to maternal concentrations, suggesting extensive placental passage to the fetus,” wrote Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues. “Therefore, the amount of AED exposure via breast milk is likely substantially lower than fetal exposure during pregnancy and appears unlikely to confer any additional risks beyond those that might be associated with exposure in pregnancy, especially given prior studies showing no adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding while taking AEDs.”

The investigators acknowledged several limitations of their research, including the observational design of the MONEAD study. The amount of AED in participants’ breast milk is unknown, and the investigators could not calculate relative infant dosages. Only one blood sample was taken per infant, thus the results may not reflect infants’ total exposure over time.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Child Health and Development funded the research. The authors reported receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Birnbaum AK et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4443.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

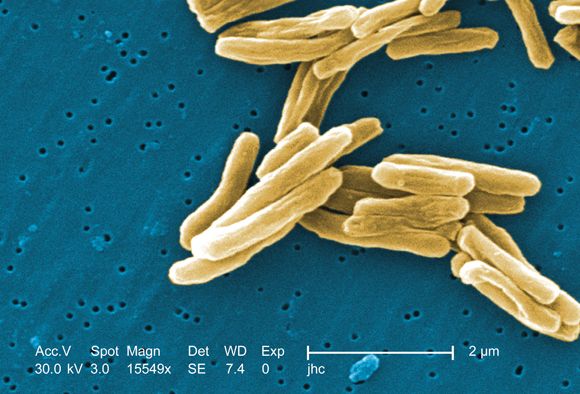

Antituberculosis drugs in pregnancy and lactation

Tuberculosis is one of the top ten causes of death worldwide and the leading cause from a single infectious agent. In the 2012-2017 period, there were more than 9,000 cases of TB each year in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that untreated TB is a greater hazard to a pregnant woman and her fetus than its treatment.

In the material below, the molecular weights, rounded to the nearest whole number, are shown in parentheses after the drug name. Those less than 1,000 or so suggest that the drug will cross the placenta throughout pregnancy. In the second half of pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, nearly all drugs will cross regardless of their molecular weight.

Para-aminosalicylic acid (Paser) (153) is most frequently used in combination with other agents for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) is defined as being caused by TB bacteria that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, the two most potent TB drugs. The drug has been associated with a marked increased risk of birth defects in some, but not all, studies. Because of this potential risk, the drug is best avoided in the first trimester. The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Bedaquiline (Sirturo) (556) is used in combination therapy for patents with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. One report describing the use of this drug during human pregnancy has been located. Treatment was started in the last 3 weeks of pregnancy and no abnormalities were noted in the child at birth and for 2 years after birth (Emerg Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.3201/eid2310.161398). The CDC states that the drug should be used only in a minimum four-drug treatment regimen and administered by direct observation (MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013 Oct 25;62[RR-09]:1-12). The drug probably is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Capreomycin (Capastat) (653-669) is a polypeptide antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces capreolus that is given intramuscularly. The human pregnancy data are limited to three reports. The toxicity of capreomycin is similar to aminoglycosides (e.g., cranial nerve VIII and renal) and it should not be used with these agents. The CDC has classified the drug as contraindicated in pregnancy. The drug probably is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Cycloserine (Seromycin) (102) is a broad spectrum antibiotic. The human pregnancy data are limited but have not shown embryo-fetal harm. Although the best course is to avoid the drug during gestation, it should not be withheld because of pregnancy if the maternal condition requires the antibiotic. The American Academy of Pediatrics classified cycloserine as compatible with breastfeeding.

Ethambutol (Myambutol) (205) should be used in conjunction with other antituberculosis drugs. The human pregnancy data do not suggest an embryo-fetal risk. A frequently used regimen is ethambutol + isoniazid + rifampin. The American Academy of Pediatrics classified ethambutol as compatible with breastfeeding.

Ethionamide (Trecator) (166) is indicated when Mycobacterium tuberculosis is resistant to isoniazid or rifampin, or when the patient is intolerant to other drugs. Although the animal reproductive data suggest risk, the limited human data suggest that the risk is probably low. If indicated, the drug should not be withheld because of pregnancy. Although the molecular weight suggests that the drug will be excreted into breast milk, no reports describing the amount in milk have been located.

Isoniazid (137) is compatible in pregnancy, even though the molecular weight suggests that it will cross the placenta, because the maternal benefit is much greater than the potential embryo-fetal risk. Although the human data are limited, the molecular weight also suggests that the drug will be excreted into breast milk, but it can be considered probably compatible during breastfeeding. No reports of isoniazid-induced effects in the nursing infant have been located, but the potential for interference with nucleic acid function and for hepatotoxicity may exist.

Pyrazinamide (123) is metabolized to an active metabolite. The molecular weight, low plasma protein binding (10%), and prolonged elimination half-life (9-10 hours) suggest that the drug will cross the placenta throughout pregnancy. The drug has been used in human pregnancy without causing embryo-fetal harm. Similar results, although limited, were reported when the drug was used during breastfeeding.

Rifabutin (Mycobutin) (847) has no reported human pregnancy data, but the animal data suggest low risk. The drug probably crosses the placenta throughout pregnancy. The maternal benefit appears to outweigh the unknown risk to the embryo-fetus, so therapy should not be withheld because of pregnancy. The drug probably is excreted into breast milk.

Rifampin (Rifadin) (823) appears to be compatible in pregnancy. Several reviews and reports have concluded that the drug was not a teratogen and recommended use of the drug with isoniazid and ethambutol. However, prophylactic vitamin K1 has been recommended to prevent drug-induced hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. There are no data regarding its use during breastfeeding, but it is probably compatible.

Rifapentine (Priftin) (877) was toxic and teratogenic in two animal species at doses close to those used in humans. In a 2018 study, however, the rates of fetal loss in pregnancies of less than 20 weeks (8/54, 15%) and congenital anomalies in live births (1/37, 3%) were within the expected background rates (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018 May;15[4]:570-80). There are no data regarding its use during breastfeeding, but it is probably compatible.

The CDC classifies four antituberculosis and one class of drugs as contraindicated in pregnancy. In addition to capreomycin mentioned above, they are amikacin, fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, lomefloxacin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin), kanamycin, and streptomycin. These ten agents are discussed in the 11th edition of my book “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation,” (Wolters Kluwer Health: Riverwood, Il., 2017). If they have to be used, checking this source will provide information that has to be discussed with the patient.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs had no disclosures, except for his book. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Tuberculosis is one of the top ten causes of death worldwide and the leading cause from a single infectious agent. In the 2012-2017 period, there were more than 9,000 cases of TB each year in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that untreated TB is a greater hazard to a pregnant woman and her fetus than its treatment.

In the material below, the molecular weights, rounded to the nearest whole number, are shown in parentheses after the drug name. Those less than 1,000 or so suggest that the drug will cross the placenta throughout pregnancy. In the second half of pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, nearly all drugs will cross regardless of their molecular weight.

Para-aminosalicylic acid (Paser) (153) is most frequently used in combination with other agents for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) is defined as being caused by TB bacteria that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, the two most potent TB drugs. The drug has been associated with a marked increased risk of birth defects in some, but not all, studies. Because of this potential risk, the drug is best avoided in the first trimester. The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Bedaquiline (Sirturo) (556) is used in combination therapy for patents with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. One report describing the use of this drug during human pregnancy has been located. Treatment was started in the last 3 weeks of pregnancy and no abnormalities were noted in the child at birth and for 2 years after birth (Emerg Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.3201/eid2310.161398). The CDC states that the drug should be used only in a minimum four-drug treatment regimen and administered by direct observation (MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013 Oct 25;62[RR-09]:1-12). The drug probably is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Capreomycin (Capastat) (653-669) is a polypeptide antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces capreolus that is given intramuscularly. The human pregnancy data are limited to three reports. The toxicity of capreomycin is similar to aminoglycosides (e.g., cranial nerve VIII and renal) and it should not be used with these agents. The CDC has classified the drug as contraindicated in pregnancy. The drug probably is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Cycloserine (Seromycin) (102) is a broad spectrum antibiotic. The human pregnancy data are limited but have not shown embryo-fetal harm. Although the best course is to avoid the drug during gestation, it should not be withheld because of pregnancy if the maternal condition requires the antibiotic. The American Academy of Pediatrics classified cycloserine as compatible with breastfeeding.

Ethambutol (Myambutol) (205) should be used in conjunction with other antituberculosis drugs. The human pregnancy data do not suggest an embryo-fetal risk. A frequently used regimen is ethambutol + isoniazid + rifampin. The American Academy of Pediatrics classified ethambutol as compatible with breastfeeding.

Ethionamide (Trecator) (166) is indicated when Mycobacterium tuberculosis is resistant to isoniazid or rifampin, or when the patient is intolerant to other drugs. Although the animal reproductive data suggest risk, the limited human data suggest that the risk is probably low. If indicated, the drug should not be withheld because of pregnancy. Although the molecular weight suggests that the drug will be excreted into breast milk, no reports describing the amount in milk have been located.

Isoniazid (137) is compatible in pregnancy, even though the molecular weight suggests that it will cross the placenta, because the maternal benefit is much greater than the potential embryo-fetal risk. Although the human data are limited, the molecular weight also suggests that the drug will be excreted into breast milk, but it can be considered probably compatible during breastfeeding. No reports of isoniazid-induced effects in the nursing infant have been located, but the potential for interference with nucleic acid function and for hepatotoxicity may exist.

Pyrazinamide (123) is metabolized to an active metabolite. The molecular weight, low plasma protein binding (10%), and prolonged elimination half-life (9-10 hours) suggest that the drug will cross the placenta throughout pregnancy. The drug has been used in human pregnancy without causing embryo-fetal harm. Similar results, although limited, were reported when the drug was used during breastfeeding.

Rifabutin (Mycobutin) (847) has no reported human pregnancy data, but the animal data suggest low risk. The drug probably crosses the placenta throughout pregnancy. The maternal benefit appears to outweigh the unknown risk to the embryo-fetus, so therapy should not be withheld because of pregnancy. The drug probably is excreted into breast milk.

Rifampin (Rifadin) (823) appears to be compatible in pregnancy. Several reviews and reports have concluded that the drug was not a teratogen and recommended use of the drug with isoniazid and ethambutol. However, prophylactic vitamin K1 has been recommended to prevent drug-induced hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. There are no data regarding its use during breastfeeding, but it is probably compatible.

Rifapentine (Priftin) (877) was toxic and teratogenic in two animal species at doses close to those used in humans. In a 2018 study, however, the rates of fetal loss in pregnancies of less than 20 weeks (8/54, 15%) and congenital anomalies in live births (1/37, 3%) were within the expected background rates (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018 May;15[4]:570-80). There are no data regarding its use during breastfeeding, but it is probably compatible.

The CDC classifies four antituberculosis and one class of drugs as contraindicated in pregnancy. In addition to capreomycin mentioned above, they are amikacin, fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, lomefloxacin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin), kanamycin, and streptomycin. These ten agents are discussed in the 11th edition of my book “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation,” (Wolters Kluwer Health: Riverwood, Il., 2017). If they have to be used, checking this source will provide information that has to be discussed with the patient.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs had no disclosures, except for his book. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Tuberculosis is one of the top ten causes of death worldwide and the leading cause from a single infectious agent. In the 2012-2017 period, there were more than 9,000 cases of TB each year in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that untreated TB is a greater hazard to a pregnant woman and her fetus than its treatment.

In the material below, the molecular weights, rounded to the nearest whole number, are shown in parentheses after the drug name. Those less than 1,000 or so suggest that the drug will cross the placenta throughout pregnancy. In the second half of pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, nearly all drugs will cross regardless of their molecular weight.

Para-aminosalicylic acid (Paser) (153) is most frequently used in combination with other agents for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) is defined as being caused by TB bacteria that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, the two most potent TB drugs. The drug has been associated with a marked increased risk of birth defects in some, but not all, studies. Because of this potential risk, the drug is best avoided in the first trimester. The drug is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Bedaquiline (Sirturo) (556) is used in combination therapy for patents with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. One report describing the use of this drug during human pregnancy has been located. Treatment was started in the last 3 weeks of pregnancy and no abnormalities were noted in the child at birth and for 2 years after birth (Emerg Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.3201/eid2310.161398). The CDC states that the drug should be used only in a minimum four-drug treatment regimen and administered by direct observation (MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013 Oct 25;62[RR-09]:1-12). The drug probably is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Capreomycin (Capastat) (653-669) is a polypeptide antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces capreolus that is given intramuscularly. The human pregnancy data are limited to three reports. The toxicity of capreomycin is similar to aminoglycosides (e.g., cranial nerve VIII and renal) and it should not be used with these agents. The CDC has classified the drug as contraindicated in pregnancy. The drug probably is excreted into breast milk, but there are no reports of its use during breastfeeding.

Cycloserine (Seromycin) (102) is a broad spectrum antibiotic. The human pregnancy data are limited but have not shown embryo-fetal harm. Although the best course is to avoid the drug during gestation, it should not be withheld because of pregnancy if the maternal condition requires the antibiotic. The American Academy of Pediatrics classified cycloserine as compatible with breastfeeding.

Ethambutol (Myambutol) (205) should be used in conjunction with other antituberculosis drugs. The human pregnancy data do not suggest an embryo-fetal risk. A frequently used regimen is ethambutol + isoniazid + rifampin. The American Academy of Pediatrics classified ethambutol as compatible with breastfeeding.

Ethionamide (Trecator) (166) is indicated when Mycobacterium tuberculosis is resistant to isoniazid or rifampin, or when the patient is intolerant to other drugs. Although the animal reproductive data suggest risk, the limited human data suggest that the risk is probably low. If indicated, the drug should not be withheld because of pregnancy. Although the molecular weight suggests that the drug will be excreted into breast milk, no reports describing the amount in milk have been located.

Isoniazid (137) is compatible in pregnancy, even though the molecular weight suggests that it will cross the placenta, because the maternal benefit is much greater than the potential embryo-fetal risk. Although the human data are limited, the molecular weight also suggests that the drug will be excreted into breast milk, but it can be considered probably compatible during breastfeeding. No reports of isoniazid-induced effects in the nursing infant have been located, but the potential for interference with nucleic acid function and for hepatotoxicity may exist.

Pyrazinamide (123) is metabolized to an active metabolite. The molecular weight, low plasma protein binding (10%), and prolonged elimination half-life (9-10 hours) suggest that the drug will cross the placenta throughout pregnancy. The drug has been used in human pregnancy without causing embryo-fetal harm. Similar results, although limited, were reported when the drug was used during breastfeeding.

Rifabutin (Mycobutin) (847) has no reported human pregnancy data, but the animal data suggest low risk. The drug probably crosses the placenta throughout pregnancy. The maternal benefit appears to outweigh the unknown risk to the embryo-fetus, so therapy should not be withheld because of pregnancy. The drug probably is excreted into breast milk.

Rifampin (Rifadin) (823) appears to be compatible in pregnancy. Several reviews and reports have concluded that the drug was not a teratogen and recommended use of the drug with isoniazid and ethambutol. However, prophylactic vitamin K1 has been recommended to prevent drug-induced hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. There are no data regarding its use during breastfeeding, but it is probably compatible.

Rifapentine (Priftin) (877) was toxic and teratogenic in two animal species at doses close to those used in humans. In a 2018 study, however, the rates of fetal loss in pregnancies of less than 20 weeks (8/54, 15%) and congenital anomalies in live births (1/37, 3%) were within the expected background rates (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018 May;15[4]:570-80). There are no data regarding its use during breastfeeding, but it is probably compatible.

The CDC classifies four antituberculosis and one class of drugs as contraindicated in pregnancy. In addition to capreomycin mentioned above, they are amikacin, fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, lomefloxacin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin), kanamycin, and streptomycin. These ten agents are discussed in the 11th edition of my book “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation,” (Wolters Kluwer Health: Riverwood, Il., 2017). If they have to be used, checking this source will provide information that has to be discussed with the patient.

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, as well as at Washington State University, Spokane. Mr. Briggs had no disclosures, except for his book. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Zulresso: Hope and lingering questions

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at admin@womensmentalhealth.org.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at admin@womensmentalhealth.org.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at admin@womensmentalhealth.org.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

Safety of ondansetron for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) affects up to 80% of pregnant women, most commonly between 5 and 18 weeks of gestation. In addition, its extreme form, hyperemesis gravidarum, affects less than 3% of pregnancies.1 Certainly with hyperemesis gravidarum, and oftentimes with less severe NVP, pharmacologic treatment is desired or required. One of the choices for such treatment has been ondansetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, which has been used off label for NVP and is now available in generic form. However, there have been concerns raised regarding the fetal safety of this medication, last reviewed in Ob.Gyn. News by Gideon Koren, MD, in a commentary published in 2013.

Since then, the escalating use of ondansetron in the United States has been described using a large dataset covering 2.3 million, predominantly commercially insured, pregnancies that resulted in live births from 2001 to 2015.1 Over that period of time, any outpatient pharmacy dispensing of an antiemetic in pregnancy increased from 17.0% in 2001 to 27.2% in 2014. That increase was entirely accounted for by a dramatic rise in oral ondansetron use beginning in 2006. By 2014, 22.4% of pregnancies in the database had received a prescription for ondansetron.