User login

An overlooked cause of catatonia

CASE Agitation and bizarre behavior

Ms. L, age 40, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status and bizarre behavior. Before arriving at the ED, she had experienced a severe headache and an episode of vomiting. At home she had been irritable and agitated, repetitively dressing and undressing, urinating outside the toilet, and opening and closing water faucets in the house. She also had stopped eating and drinking. Ms. L’s home medications consist of levothyroxine 100 mcg/d for hypothyroidism.

In the ED, Ms. L has severe psychomotor agitation. She is restless and displays purposeless repetitive movements with her hands. She is mostly mute, but does groan at times.

HISTORY Multiple trips to the ED

In addition to hypothyroidism, Ms. L has a history of migraines and asthma. Four days before presenting to the ED, she complained of a severe headache and generalized fatigue, with vomiting and nausea. Two days later, she presented to the ED at a different hospital and underwent a brain CT scan; the results were unremarkable. At that facility, a laboratory work-up—including complete blood count, urea, creatinine, C-reactive protein, electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, full liver function tests, amylase, lipase, bilirubin, thyroid function test, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin—was normal except for low thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (0.016 mIU/L). Ms. L was diagnosed with a severe migraine attack and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her endocrinologist.

Ms. L has no previous psychiatric history. Her family’s psychiatric history includes depression with psychotic features (mother), depression (maternal aunt), and generalized anxiety disorder (mother’s maternal aunt).

[polldaddy:11252938]

The authors’ observations

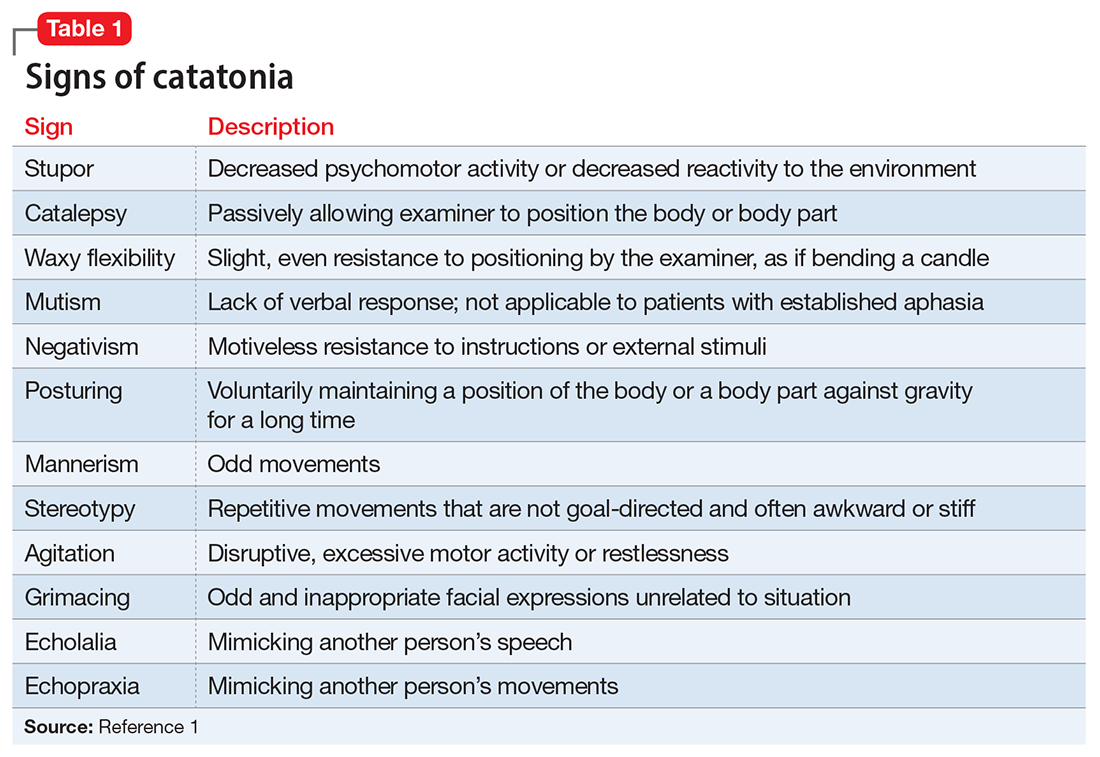

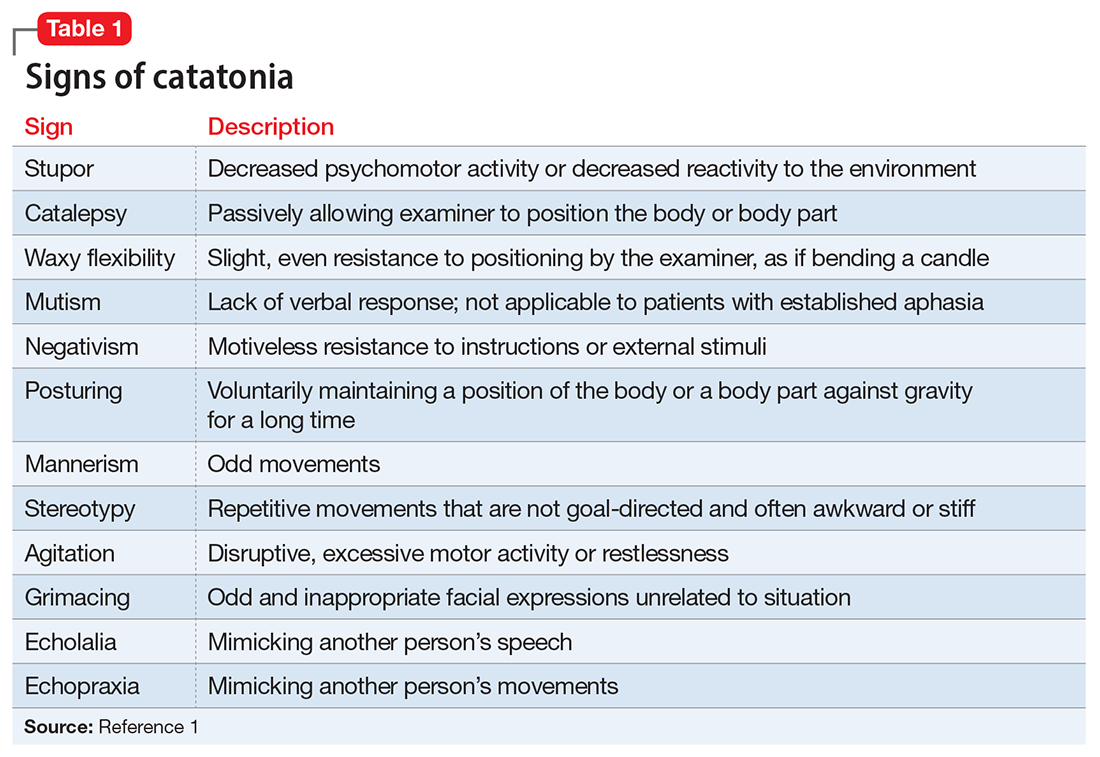

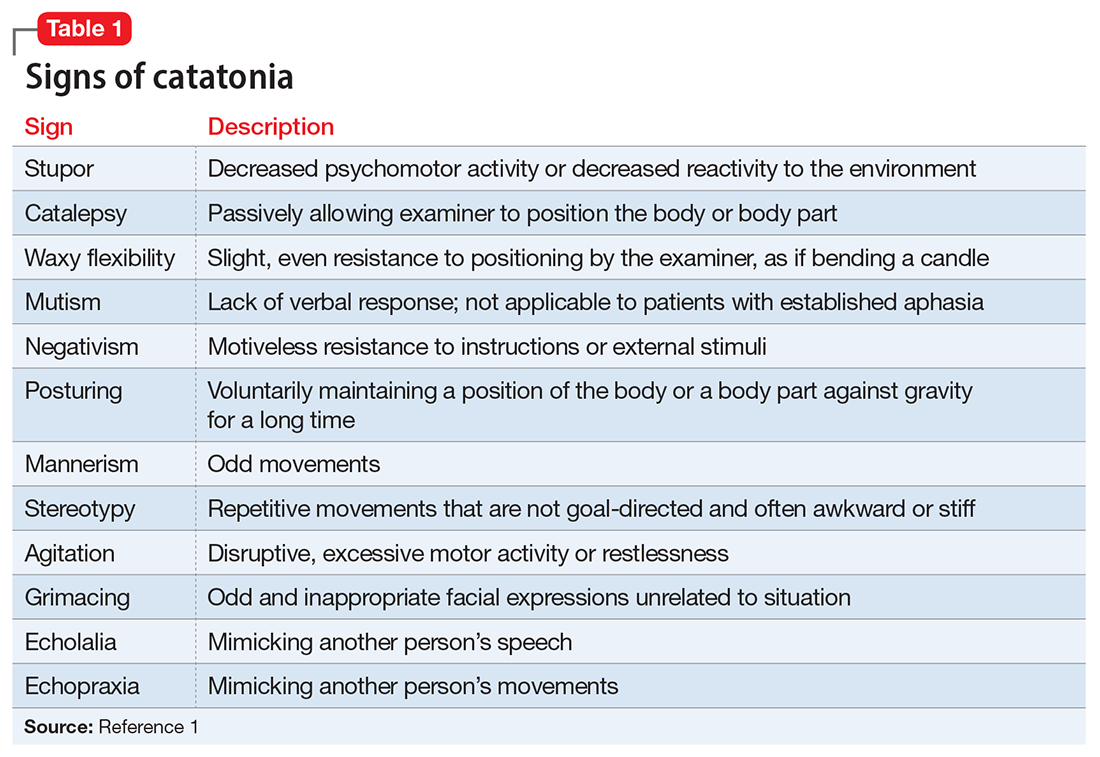

Catatonia is a behavioral syndrome with heterogeneous signs and symptoms. According to DSM-5, the diagnosis is considered when a patient presents with ≥3 of the 12 signs outlined in Table 1.1 It usually occurs in the context of an underlying psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or depression, or a medical disorder such as CNS infection or encephalopathy due to metabolic causes.1 Ms. L exhibited mutism, negativism, mannerism, stereotypy, and agitation and thus met the criteria for a catatonia diagnosis.

EVALUATION Unexpected finding on physical exam

In the ED, Ms. L is hemodynamically stable. Her blood pressure is 140/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; oxygen saturation is 98%; respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute; and temperature is 37.5° C. Results from a brain MRI and total body scan performed prior to admission are unremarkable.

Ms. L is admitted to the psychiatric ward under the care of neurology for a psychiatry consultation. For approximately 24 hours, she receives IV diazepam 5 mg every 8 hours (due to the unavailability of lorazepam) for management of her catatonic symptoms, and olanzapine 10 mg every 8 hours orally as needed for agitation. Collateral history rules out a current mood episode or onset of psychosis in the weeks before she came to the ED. Diazepam improves Ms. L’s psychomotor agitation, which allows the primary team an opportunity to examine her.

Continue to: A physical exam reveals...

A physical exam reveals small vesicular lesions (1 to 2 cm in diameter) on an erythematous base on the left breast associated with an erythematous plaque with no evident vesicles on the left inner arm. The vesicular lesions display in a segmented pattern of dermatomal distribution.

[polldaddy:11252941]

The authors’ observations

Catatonic symptoms, coupled with psychomotor agitation in an immunocompetent middle-aged adult with a history of migraine headaches, strong family history of severe mental illness, and noncontributory findings on brain imaging, prompted a Psychiatry consultation and administration of psychotropic medications. A thorough physical exam revealing the small area of shingles and acute altered mental status prompted more aggressive investigations to explore the possibility of encephalitis.

Physicians should have a low index of suspicion for encephalitis (viral, bacterial, autoimmune, etc) and perform a lumbar puncture (LP) when necessary, despite the invasiveness of this test. A direct physical examination is often underutilized, notably in psychiatric patients, which can lead to the omission of important clinical information.2 Normal vital signs, blood workup, and MRI before admission are not sufficient to correctly guide diagnosis.

EVALUATION Additional lab results establish the diagnosis

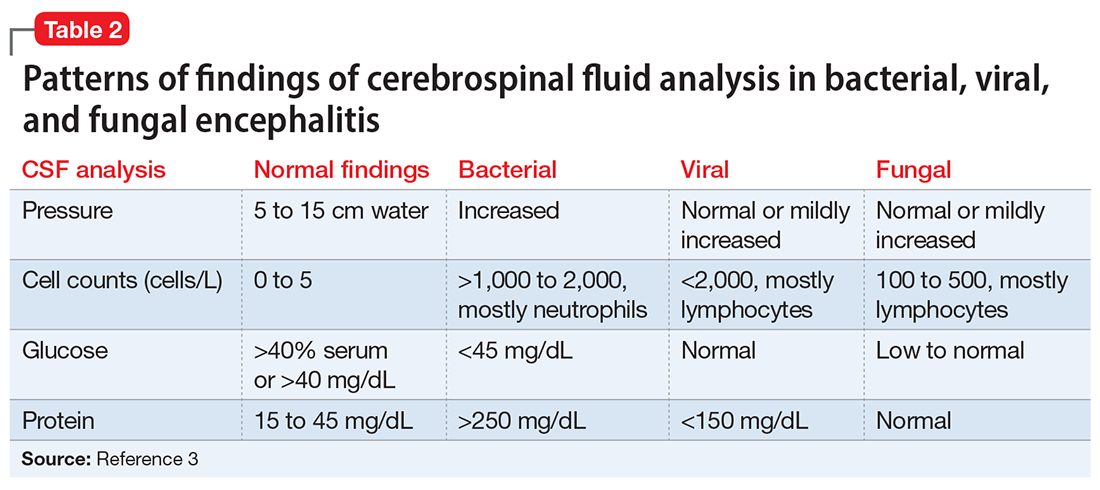

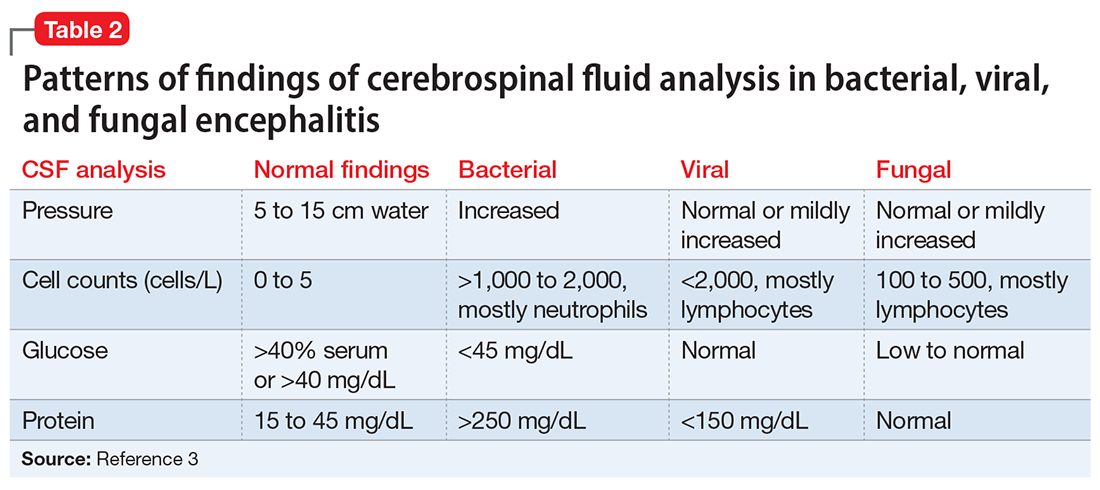

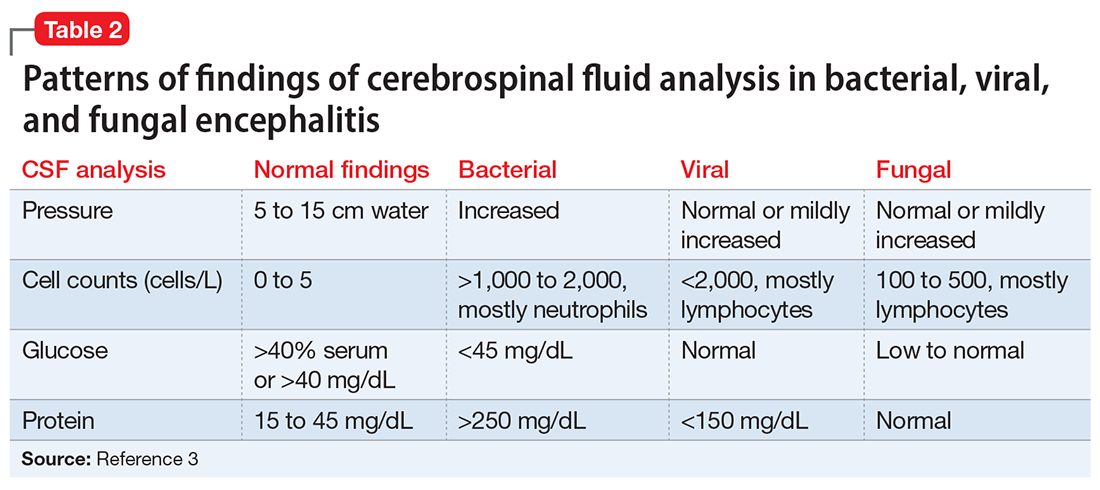

An LP reveals Ms. L’s protein levels are 44 mg/dL, her glucose levels are 85 mg/dL, red blood cell count is 4/µL, and white blood cell count is 200/µL with 92% lymphocytes and 1% neutrophils. Ms. L’s CSF analysis profile indicates a viral CNS infection (Table 23).

[polldaddy:11252943]

The authors’ observations

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) are human neurotropic alphaherpesviruses that cause lifelong infections in ganglia, and their reactivation can come in the form of encephalitis.4

Continue to: Ms. L's clinical presentation...

Ms. L’s clinical presentation most likely implicated VZV. Skin lesions of VZV may look exactly like HSV, with clustered vesicles on an erythematous base (Figure5). However, VZV rash tends to follow a dermatomal distribution (as in Ms. L’s case), which can help distinguish it from herpetic lesions.

Cases of VZV infection have been increasing worldwide. It is usually seen in older adults or those with compromised immunity.6 Significantly higher rates of VZV complications have been reported in such patients. A serious complication is VZV encephalitis, which is rare but possible, even in healthy individuals.6 VZV encephalitis can present with atypical psychiatric features. Ms. L exhibited several symptoms of VZV encephalitis, which include headache, fever, vomiting, altered level of consciousness, and seizures. An EEG also showed intermittent generalized slow waves in the range of theta commonly seen in encephalitis.

Ms. L’s case shows the importance of early recognition of VZV infection. The diagnosis is confirmed through CSF analysis. There is an urgency to promptly conduct the LP to confirm the diagnosis and quickly initiate antiviral treatment to stop the progression of the infection and its life-threatening sequelae.

In the absence of underlying medical cause, typical treatment of catatonia involves the sublingual or IM administration of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam that can be repeated twice at 3-hour intervals if the patient’s symptoms do not resolve. ECT is indicated if the patient experiences minimal or no response to lorazepam.

The use of antipsychotics for catatonia is controversial. High-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol and risperidone are not recommended due to increased risk of the progression of catatonia into neuroleptic malignant syndrome.7

Continue to: OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

Ms. L receives IV acyclovir 1,200 mg every 8 hours for 14 days. Just 48 hours after starting this antiviral medication, her bizarre behavior and catatonic features cease, and she returns to her baseline mental functioning. Olanzapine is discontinued, and lorazepam is progressively decreased. The CSF polymerase chain reaction assay indicates Ms. L is positive for VZV, which confirms the diagnosis of VZV encephalitis. A spine MRI is also performed and rules out myelitis as a sequela of the infection.

The authors’ observations

Chickenpox is caused by a primary encounter with VZV. Inside the ganglions of neurons, a dormant form of VZV resides. Its reactivation leads to the spread of the infection to the skin innervated by these neurons, causing shingles. Reactivation occurs in approximately 1 million people in the United States each year. The annual incidence is 5 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 people at age 60, and 8 to 11 cases per 1,000 people at age 70.8

In 2006, the FDA approved the first zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for use in nonimmunocompromised, VZV-seropositive adults age >60 (later lowered to age 50). This vaccine reduces the incidence of shingles by 51%, the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia by 66%, and the burden of illness by 61%. In 2017, the FDA approved a second VZV vaccine (Shingrix, recombinant nonlive vaccine). In 2021, Shingrix was approved for use in immunosuppressed patients.9

Reactivation of VZV starts with a prodromal phase, characterized by pain, itching, numbness, and dysesthesias in 1 to 3 dermatomes. A maculopapular rash appears on the affected area a few days later, evolving into vesicles that scab over in 10 days.10

Dissemination of the virus leading specifically to VZV encephalitis typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals and older patients. According to the World Health Organization, encephalitis is a life-threatening complication of VZV and occurs in 1 of 33,000 to 50,000 cases.11

Continue to: Delay in the diagnosis...

Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of VZV encephalitis can be detrimental or even fatal. Kodadhala et al12 found that the mortality rate for VZV encephalitis is 5% to 10% and ≤80% in immunosuppressed individuals.

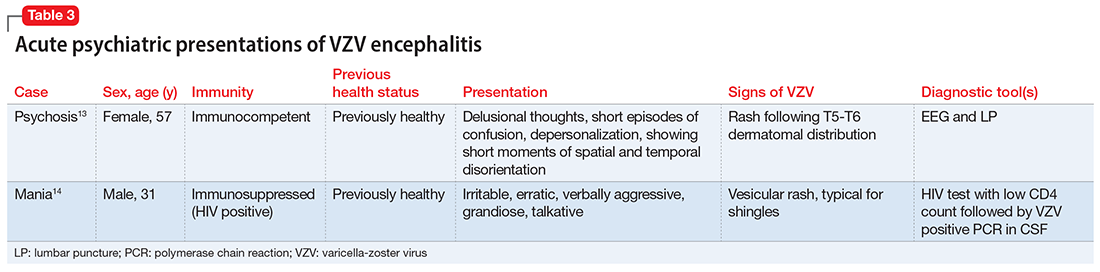

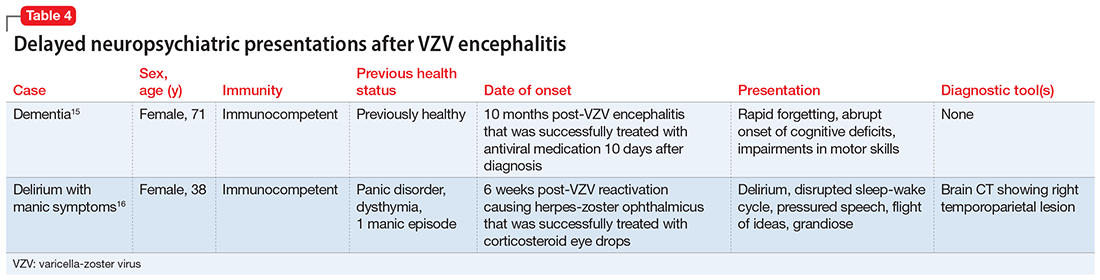

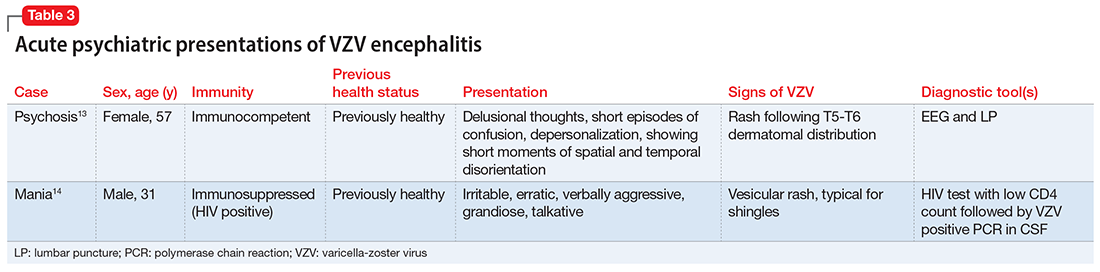

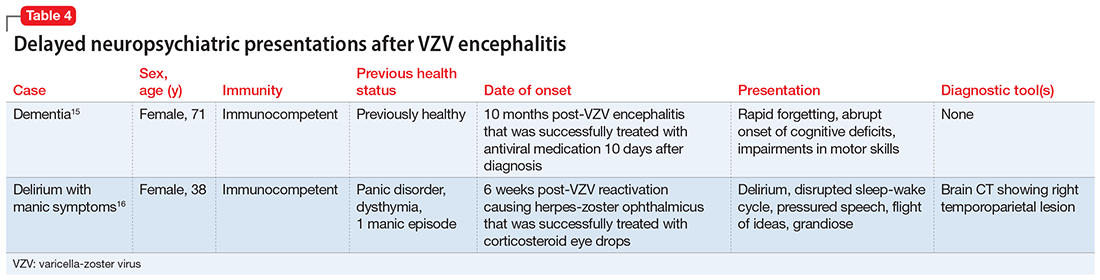

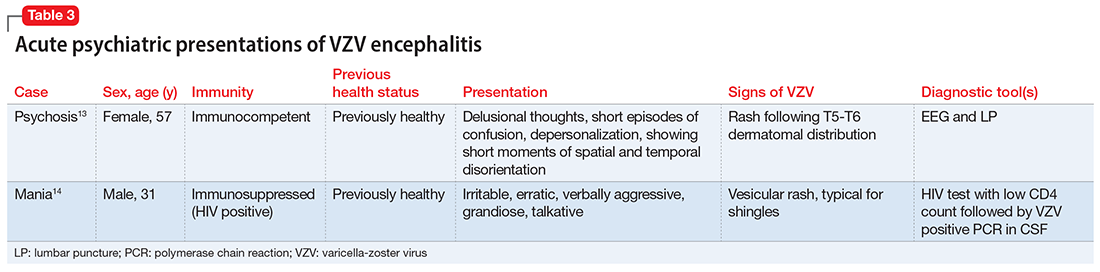

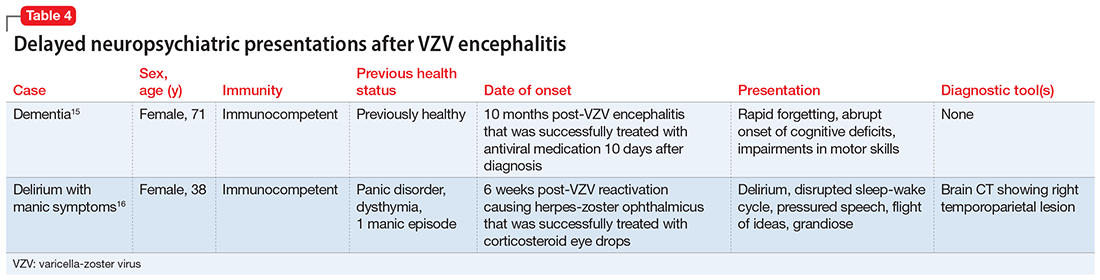

Sometimes, VZV encephalitis can masquerade as a psychiatric presentation. Few cases presenting with acute or delayed neuropsychiatric symptoms related to VZV encephalitis have been previously reported in the literature. Some are summarized in Table 313,14 and Table 4.15,16

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of catatonia as a presentation of VZV encephalitis. The catatonic presentation has been previously described in autoimmune encephalitis such as N-methyl-

Bottom Line

In the setting of a patient with an abrupt change in mental status/behavior, physicians must be aware of the importance of a thorough physical examination to better ascertain a diagnosis and to rule out an underlying medical disorder. Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can result in encephalitis that might masquerade as a psychiatric presentation, including symptoms of catatonia.

Related Resources

- Baum ML, Johnson MC, Lizano P. Is it psychosis, or an autoimmune encephalitis? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8): 31-38,44. doi:10.12788/cp.0273

- Reinfold S. Are we failing to diagnose and treat the many faces of catatonia? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):e3-e5. doi:10.12788/cp.0208

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Sitavig

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sanders RD, Keshavan MS. Physical and neurologic examinations in neuropsychiatry. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7(1):18-29.

3. Howes DS, Lazoff M. Encephalitis workup. Medscape. Updated August 7, 2018. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/791896-workup#c11

4. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

5. Fisle, CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0). Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Herpes_zoster_chest.png

6. John AR, Canaday DH. Herpes zoster in the older adult. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(4):811-826.

7. Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF. Catatonia and its treatment. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):239-242.

8. Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15016.

9. Raedler LA. Shingrix (zoster vaccine recombinant) a new vaccine approved for herpes zoster prevention in older adults. American Health & Drug Benefits, Ninth Annual Payers’ Guide. March 2018. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2018/april-2018-vol-11-ninth-annual-payers-guide/2567-shingrix-zoster-vaccine-recombinant-a-new-vaccine-approved-for-herpes-zoster-prevention-in-older-adults

10. Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes zoster. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/

11. Lizzi J, Hill T, Jakubowski J. Varicella zoster virus encephalitis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(4):380-382.

12. Kodadhala V, Dessalegn M, Barned S, et al. 578: Varicella encephalitis: a rare complication of herpes zoster in an elderly patient. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):269.

13. Tremolizzo L, Tremolizzo S, Beghi M, et al. Mood disorder with psychotic symptoms and overlooked skin lesions: the strange case of Mrs. O. Riv Psichiatr. 2012;47(5):447-450.

14. George O, Daniel J, Forsyth S, et al. Mania presenting as a VZV encephalitis in the context of HIV. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(9):e230512.

15. Bangen KJ, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga CE, et al. Dementia following herpes zoster encephalitis. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24(7):1193-1203.

16. McKenna KF, Warneke LB. Encephalitis associated with herpes zoster: a case report and review. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37(4):271-273.

17. Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Blackman G, et al. Catatonia and the immune system: a review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):620-630.

CASE Agitation and bizarre behavior

Ms. L, age 40, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status and bizarre behavior. Before arriving at the ED, she had experienced a severe headache and an episode of vomiting. At home she had been irritable and agitated, repetitively dressing and undressing, urinating outside the toilet, and opening and closing water faucets in the house. She also had stopped eating and drinking. Ms. L’s home medications consist of levothyroxine 100 mcg/d for hypothyroidism.

In the ED, Ms. L has severe psychomotor agitation. She is restless and displays purposeless repetitive movements with her hands. She is mostly mute, but does groan at times.

HISTORY Multiple trips to the ED

In addition to hypothyroidism, Ms. L has a history of migraines and asthma. Four days before presenting to the ED, she complained of a severe headache and generalized fatigue, with vomiting and nausea. Two days later, she presented to the ED at a different hospital and underwent a brain CT scan; the results were unremarkable. At that facility, a laboratory work-up—including complete blood count, urea, creatinine, C-reactive protein, electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, full liver function tests, amylase, lipase, bilirubin, thyroid function test, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin—was normal except for low thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (0.016 mIU/L). Ms. L was diagnosed with a severe migraine attack and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her endocrinologist.

Ms. L has no previous psychiatric history. Her family’s psychiatric history includes depression with psychotic features (mother), depression (maternal aunt), and generalized anxiety disorder (mother’s maternal aunt).

[polldaddy:11252938]

The authors’ observations

Catatonia is a behavioral syndrome with heterogeneous signs and symptoms. According to DSM-5, the diagnosis is considered when a patient presents with ≥3 of the 12 signs outlined in Table 1.1 It usually occurs in the context of an underlying psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or depression, or a medical disorder such as CNS infection or encephalopathy due to metabolic causes.1 Ms. L exhibited mutism, negativism, mannerism, stereotypy, and agitation and thus met the criteria for a catatonia diagnosis.

EVALUATION Unexpected finding on physical exam

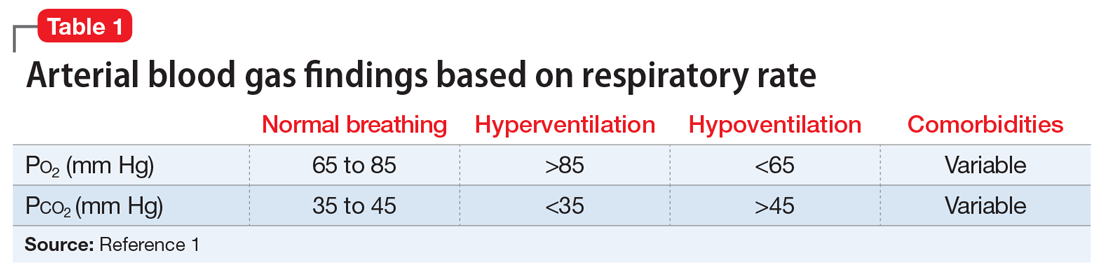

In the ED, Ms. L is hemodynamically stable. Her blood pressure is 140/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; oxygen saturation is 98%; respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute; and temperature is 37.5° C. Results from a brain MRI and total body scan performed prior to admission are unremarkable.

Ms. L is admitted to the psychiatric ward under the care of neurology for a psychiatry consultation. For approximately 24 hours, she receives IV diazepam 5 mg every 8 hours (due to the unavailability of lorazepam) for management of her catatonic symptoms, and olanzapine 10 mg every 8 hours orally as needed for agitation. Collateral history rules out a current mood episode or onset of psychosis in the weeks before she came to the ED. Diazepam improves Ms. L’s psychomotor agitation, which allows the primary team an opportunity to examine her.

Continue to: A physical exam reveals...

A physical exam reveals small vesicular lesions (1 to 2 cm in diameter) on an erythematous base on the left breast associated with an erythematous plaque with no evident vesicles on the left inner arm. The vesicular lesions display in a segmented pattern of dermatomal distribution.

[polldaddy:11252941]

The authors’ observations

Catatonic symptoms, coupled with psychomotor agitation in an immunocompetent middle-aged adult with a history of migraine headaches, strong family history of severe mental illness, and noncontributory findings on brain imaging, prompted a Psychiatry consultation and administration of psychotropic medications. A thorough physical exam revealing the small area of shingles and acute altered mental status prompted more aggressive investigations to explore the possibility of encephalitis.

Physicians should have a low index of suspicion for encephalitis (viral, bacterial, autoimmune, etc) and perform a lumbar puncture (LP) when necessary, despite the invasiveness of this test. A direct physical examination is often underutilized, notably in psychiatric patients, which can lead to the omission of important clinical information.2 Normal vital signs, blood workup, and MRI before admission are not sufficient to correctly guide diagnosis.

EVALUATION Additional lab results establish the diagnosis

An LP reveals Ms. L’s protein levels are 44 mg/dL, her glucose levels are 85 mg/dL, red blood cell count is 4/µL, and white blood cell count is 200/µL with 92% lymphocytes and 1% neutrophils. Ms. L’s CSF analysis profile indicates a viral CNS infection (Table 23).

[polldaddy:11252943]

The authors’ observations

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) are human neurotropic alphaherpesviruses that cause lifelong infections in ganglia, and their reactivation can come in the form of encephalitis.4

Continue to: Ms. L's clinical presentation...

Ms. L’s clinical presentation most likely implicated VZV. Skin lesions of VZV may look exactly like HSV, with clustered vesicles on an erythematous base (Figure5). However, VZV rash tends to follow a dermatomal distribution (as in Ms. L’s case), which can help distinguish it from herpetic lesions.

Cases of VZV infection have been increasing worldwide. It is usually seen in older adults or those with compromised immunity.6 Significantly higher rates of VZV complications have been reported in such patients. A serious complication is VZV encephalitis, which is rare but possible, even in healthy individuals.6 VZV encephalitis can present with atypical psychiatric features. Ms. L exhibited several symptoms of VZV encephalitis, which include headache, fever, vomiting, altered level of consciousness, and seizures. An EEG also showed intermittent generalized slow waves in the range of theta commonly seen in encephalitis.

Ms. L’s case shows the importance of early recognition of VZV infection. The diagnosis is confirmed through CSF analysis. There is an urgency to promptly conduct the LP to confirm the diagnosis and quickly initiate antiviral treatment to stop the progression of the infection and its life-threatening sequelae.

In the absence of underlying medical cause, typical treatment of catatonia involves the sublingual or IM administration of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam that can be repeated twice at 3-hour intervals if the patient’s symptoms do not resolve. ECT is indicated if the patient experiences minimal or no response to lorazepam.

The use of antipsychotics for catatonia is controversial. High-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol and risperidone are not recommended due to increased risk of the progression of catatonia into neuroleptic malignant syndrome.7

Continue to: OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

Ms. L receives IV acyclovir 1,200 mg every 8 hours for 14 days. Just 48 hours after starting this antiviral medication, her bizarre behavior and catatonic features cease, and she returns to her baseline mental functioning. Olanzapine is discontinued, and lorazepam is progressively decreased. The CSF polymerase chain reaction assay indicates Ms. L is positive for VZV, which confirms the diagnosis of VZV encephalitis. A spine MRI is also performed and rules out myelitis as a sequela of the infection.

The authors’ observations

Chickenpox is caused by a primary encounter with VZV. Inside the ganglions of neurons, a dormant form of VZV resides. Its reactivation leads to the spread of the infection to the skin innervated by these neurons, causing shingles. Reactivation occurs in approximately 1 million people in the United States each year. The annual incidence is 5 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 people at age 60, and 8 to 11 cases per 1,000 people at age 70.8

In 2006, the FDA approved the first zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for use in nonimmunocompromised, VZV-seropositive adults age >60 (later lowered to age 50). This vaccine reduces the incidence of shingles by 51%, the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia by 66%, and the burden of illness by 61%. In 2017, the FDA approved a second VZV vaccine (Shingrix, recombinant nonlive vaccine). In 2021, Shingrix was approved for use in immunosuppressed patients.9

Reactivation of VZV starts with a prodromal phase, characterized by pain, itching, numbness, and dysesthesias in 1 to 3 dermatomes. A maculopapular rash appears on the affected area a few days later, evolving into vesicles that scab over in 10 days.10

Dissemination of the virus leading specifically to VZV encephalitis typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals and older patients. According to the World Health Organization, encephalitis is a life-threatening complication of VZV and occurs in 1 of 33,000 to 50,000 cases.11

Continue to: Delay in the diagnosis...

Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of VZV encephalitis can be detrimental or even fatal. Kodadhala et al12 found that the mortality rate for VZV encephalitis is 5% to 10% and ≤80% in immunosuppressed individuals.

Sometimes, VZV encephalitis can masquerade as a psychiatric presentation. Few cases presenting with acute or delayed neuropsychiatric symptoms related to VZV encephalitis have been previously reported in the literature. Some are summarized in Table 313,14 and Table 4.15,16

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of catatonia as a presentation of VZV encephalitis. The catatonic presentation has been previously described in autoimmune encephalitis such as N-methyl-

Bottom Line

In the setting of a patient with an abrupt change in mental status/behavior, physicians must be aware of the importance of a thorough physical examination to better ascertain a diagnosis and to rule out an underlying medical disorder. Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can result in encephalitis that might masquerade as a psychiatric presentation, including symptoms of catatonia.

Related Resources

- Baum ML, Johnson MC, Lizano P. Is it psychosis, or an autoimmune encephalitis? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8): 31-38,44. doi:10.12788/cp.0273

- Reinfold S. Are we failing to diagnose and treat the many faces of catatonia? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):e3-e5. doi:10.12788/cp.0208

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Sitavig

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

CASE Agitation and bizarre behavior

Ms. L, age 40, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status and bizarre behavior. Before arriving at the ED, she had experienced a severe headache and an episode of vomiting. At home she had been irritable and agitated, repetitively dressing and undressing, urinating outside the toilet, and opening and closing water faucets in the house. She also had stopped eating and drinking. Ms. L’s home medications consist of levothyroxine 100 mcg/d for hypothyroidism.

In the ED, Ms. L has severe psychomotor agitation. She is restless and displays purposeless repetitive movements with her hands. She is mostly mute, but does groan at times.

HISTORY Multiple trips to the ED

In addition to hypothyroidism, Ms. L has a history of migraines and asthma. Four days before presenting to the ED, she complained of a severe headache and generalized fatigue, with vomiting and nausea. Two days later, she presented to the ED at a different hospital and underwent a brain CT scan; the results were unremarkable. At that facility, a laboratory work-up—including complete blood count, urea, creatinine, C-reactive protein, electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, full liver function tests, amylase, lipase, bilirubin, thyroid function test, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin—was normal except for low thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (0.016 mIU/L). Ms. L was diagnosed with a severe migraine attack and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her endocrinologist.

Ms. L has no previous psychiatric history. Her family’s psychiatric history includes depression with psychotic features (mother), depression (maternal aunt), and generalized anxiety disorder (mother’s maternal aunt).

[polldaddy:11252938]

The authors’ observations

Catatonia is a behavioral syndrome with heterogeneous signs and symptoms. According to DSM-5, the diagnosis is considered when a patient presents with ≥3 of the 12 signs outlined in Table 1.1 It usually occurs in the context of an underlying psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or depression, or a medical disorder such as CNS infection or encephalopathy due to metabolic causes.1 Ms. L exhibited mutism, negativism, mannerism, stereotypy, and agitation and thus met the criteria for a catatonia diagnosis.

EVALUATION Unexpected finding on physical exam

In the ED, Ms. L is hemodynamically stable. Her blood pressure is 140/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; oxygen saturation is 98%; respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute; and temperature is 37.5° C. Results from a brain MRI and total body scan performed prior to admission are unremarkable.

Ms. L is admitted to the psychiatric ward under the care of neurology for a psychiatry consultation. For approximately 24 hours, she receives IV diazepam 5 mg every 8 hours (due to the unavailability of lorazepam) for management of her catatonic symptoms, and olanzapine 10 mg every 8 hours orally as needed for agitation. Collateral history rules out a current mood episode or onset of psychosis in the weeks before she came to the ED. Diazepam improves Ms. L’s psychomotor agitation, which allows the primary team an opportunity to examine her.

Continue to: A physical exam reveals...

A physical exam reveals small vesicular lesions (1 to 2 cm in diameter) on an erythematous base on the left breast associated with an erythematous plaque with no evident vesicles on the left inner arm. The vesicular lesions display in a segmented pattern of dermatomal distribution.

[polldaddy:11252941]

The authors’ observations

Catatonic symptoms, coupled with psychomotor agitation in an immunocompetent middle-aged adult with a history of migraine headaches, strong family history of severe mental illness, and noncontributory findings on brain imaging, prompted a Psychiatry consultation and administration of psychotropic medications. A thorough physical exam revealing the small area of shingles and acute altered mental status prompted more aggressive investigations to explore the possibility of encephalitis.

Physicians should have a low index of suspicion for encephalitis (viral, bacterial, autoimmune, etc) and perform a lumbar puncture (LP) when necessary, despite the invasiveness of this test. A direct physical examination is often underutilized, notably in psychiatric patients, which can lead to the omission of important clinical information.2 Normal vital signs, blood workup, and MRI before admission are not sufficient to correctly guide diagnosis.

EVALUATION Additional lab results establish the diagnosis

An LP reveals Ms. L’s protein levels are 44 mg/dL, her glucose levels are 85 mg/dL, red blood cell count is 4/µL, and white blood cell count is 200/µL with 92% lymphocytes and 1% neutrophils. Ms. L’s CSF analysis profile indicates a viral CNS infection (Table 23).

[polldaddy:11252943]

The authors’ observations

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) are human neurotropic alphaherpesviruses that cause lifelong infections in ganglia, and their reactivation can come in the form of encephalitis.4

Continue to: Ms. L's clinical presentation...

Ms. L’s clinical presentation most likely implicated VZV. Skin lesions of VZV may look exactly like HSV, with clustered vesicles on an erythematous base (Figure5). However, VZV rash tends to follow a dermatomal distribution (as in Ms. L’s case), which can help distinguish it from herpetic lesions.

Cases of VZV infection have been increasing worldwide. It is usually seen in older adults or those with compromised immunity.6 Significantly higher rates of VZV complications have been reported in such patients. A serious complication is VZV encephalitis, which is rare but possible, even in healthy individuals.6 VZV encephalitis can present with atypical psychiatric features. Ms. L exhibited several symptoms of VZV encephalitis, which include headache, fever, vomiting, altered level of consciousness, and seizures. An EEG also showed intermittent generalized slow waves in the range of theta commonly seen in encephalitis.

Ms. L’s case shows the importance of early recognition of VZV infection. The diagnosis is confirmed through CSF analysis. There is an urgency to promptly conduct the LP to confirm the diagnosis and quickly initiate antiviral treatment to stop the progression of the infection and its life-threatening sequelae.

In the absence of underlying medical cause, typical treatment of catatonia involves the sublingual or IM administration of 1 to 2 mg lorazepam that can be repeated twice at 3-hour intervals if the patient’s symptoms do not resolve. ECT is indicated if the patient experiences minimal or no response to lorazepam.

The use of antipsychotics for catatonia is controversial. High-potency antipsychotics such as haloperidol and risperidone are not recommended due to increased risk of the progression of catatonia into neuroleptic malignant syndrome.7

Continue to: OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

OUTCOME Prompt recovery with an antiviral

Ms. L receives IV acyclovir 1,200 mg every 8 hours for 14 days. Just 48 hours after starting this antiviral medication, her bizarre behavior and catatonic features cease, and she returns to her baseline mental functioning. Olanzapine is discontinued, and lorazepam is progressively decreased. The CSF polymerase chain reaction assay indicates Ms. L is positive for VZV, which confirms the diagnosis of VZV encephalitis. A spine MRI is also performed and rules out myelitis as a sequela of the infection.

The authors’ observations

Chickenpox is caused by a primary encounter with VZV. Inside the ganglions of neurons, a dormant form of VZV resides. Its reactivation leads to the spread of the infection to the skin innervated by these neurons, causing shingles. Reactivation occurs in approximately 1 million people in the United States each year. The annual incidence is 5 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 people at age 60, and 8 to 11 cases per 1,000 people at age 70.8

In 2006, the FDA approved the first zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for use in nonimmunocompromised, VZV-seropositive adults age >60 (later lowered to age 50). This vaccine reduces the incidence of shingles by 51%, the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia by 66%, and the burden of illness by 61%. In 2017, the FDA approved a second VZV vaccine (Shingrix, recombinant nonlive vaccine). In 2021, Shingrix was approved for use in immunosuppressed patients.9

Reactivation of VZV starts with a prodromal phase, characterized by pain, itching, numbness, and dysesthesias in 1 to 3 dermatomes. A maculopapular rash appears on the affected area a few days later, evolving into vesicles that scab over in 10 days.10

Dissemination of the virus leading specifically to VZV encephalitis typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals and older patients. According to the World Health Organization, encephalitis is a life-threatening complication of VZV and occurs in 1 of 33,000 to 50,000 cases.11

Continue to: Delay in the diagnosis...

Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of VZV encephalitis can be detrimental or even fatal. Kodadhala et al12 found that the mortality rate for VZV encephalitis is 5% to 10% and ≤80% in immunosuppressed individuals.

Sometimes, VZV encephalitis can masquerade as a psychiatric presentation. Few cases presenting with acute or delayed neuropsychiatric symptoms related to VZV encephalitis have been previously reported in the literature. Some are summarized in Table 313,14 and Table 4.15,16

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of catatonia as a presentation of VZV encephalitis. The catatonic presentation has been previously described in autoimmune encephalitis such as N-methyl-

Bottom Line

In the setting of a patient with an abrupt change in mental status/behavior, physicians must be aware of the importance of a thorough physical examination to better ascertain a diagnosis and to rule out an underlying medical disorder. Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can result in encephalitis that might masquerade as a psychiatric presentation, including symptoms of catatonia.

Related Resources

- Baum ML, Johnson MC, Lizano P. Is it psychosis, or an autoimmune encephalitis? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8): 31-38,44. doi:10.12788/cp.0273

- Reinfold S. Are we failing to diagnose and treat the many faces of catatonia? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):e3-e5. doi:10.12788/cp.0208

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Sitavig

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sanders RD, Keshavan MS. Physical and neurologic examinations in neuropsychiatry. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7(1):18-29.

3. Howes DS, Lazoff M. Encephalitis workup. Medscape. Updated August 7, 2018. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/791896-workup#c11

4. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

5. Fisle, CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0). Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Herpes_zoster_chest.png

6. John AR, Canaday DH. Herpes zoster in the older adult. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(4):811-826.

7. Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF. Catatonia and its treatment. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):239-242.

8. Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15016.

9. Raedler LA. Shingrix (zoster vaccine recombinant) a new vaccine approved for herpes zoster prevention in older adults. American Health & Drug Benefits, Ninth Annual Payers’ Guide. March 2018. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2018/april-2018-vol-11-ninth-annual-payers-guide/2567-shingrix-zoster-vaccine-recombinant-a-new-vaccine-approved-for-herpes-zoster-prevention-in-older-adults

10. Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes zoster. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/

11. Lizzi J, Hill T, Jakubowski J. Varicella zoster virus encephalitis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(4):380-382.

12. Kodadhala V, Dessalegn M, Barned S, et al. 578: Varicella encephalitis: a rare complication of herpes zoster in an elderly patient. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):269.

13. Tremolizzo L, Tremolizzo S, Beghi M, et al. Mood disorder with psychotic symptoms and overlooked skin lesions: the strange case of Mrs. O. Riv Psichiatr. 2012;47(5):447-450.

14. George O, Daniel J, Forsyth S, et al. Mania presenting as a VZV encephalitis in the context of HIV. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(9):e230512.

15. Bangen KJ, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga CE, et al. Dementia following herpes zoster encephalitis. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24(7):1193-1203.

16. McKenna KF, Warneke LB. Encephalitis associated with herpes zoster: a case report and review. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37(4):271-273.

17. Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Blackman G, et al. Catatonia and the immune system: a review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):620-630.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sanders RD, Keshavan MS. Physical and neurologic examinations in neuropsychiatry. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7(1):18-29.

3. Howes DS, Lazoff M. Encephalitis workup. Medscape. Updated August 7, 2018. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/791896-workup#c11

4. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

5. Fisle, CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0). Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Herpes_zoster_chest.png

6. John AR, Canaday DH. Herpes zoster in the older adult. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31(4):811-826.

7. Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF. Catatonia and its treatment. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):239-242.

8. Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15016.

9. Raedler LA. Shingrix (zoster vaccine recombinant) a new vaccine approved for herpes zoster prevention in older adults. American Health & Drug Benefits, Ninth Annual Payers’ Guide. March 2018. Updated August 30, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2018/april-2018-vol-11-ninth-annual-payers-guide/2567-shingrix-zoster-vaccine-recombinant-a-new-vaccine-approved-for-herpes-zoster-prevention-in-older-adults

10. Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes zoster. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/

11. Lizzi J, Hill T, Jakubowski J. Varicella zoster virus encephalitis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3(4):380-382.

12. Kodadhala V, Dessalegn M, Barned S, et al. 578: Varicella encephalitis: a rare complication of herpes zoster in an elderly patient. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(1):269.

13. Tremolizzo L, Tremolizzo S, Beghi M, et al. Mood disorder with psychotic symptoms and overlooked skin lesions: the strange case of Mrs. O. Riv Psichiatr. 2012;47(5):447-450.

14. George O, Daniel J, Forsyth S, et al. Mania presenting as a VZV encephalitis in the context of HIV. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(9):e230512.

15. Bangen KJ, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga CE, et al. Dementia following herpes zoster encephalitis. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24(7):1193-1203.

16. McKenna KF, Warneke LB. Encephalitis associated with herpes zoster: a case report and review. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37(4):271-273.

17. Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Blackman G, et al. Catatonia and the immune system: a review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):620-630.

Hold or not to hold: Navigating involuntary commitment

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

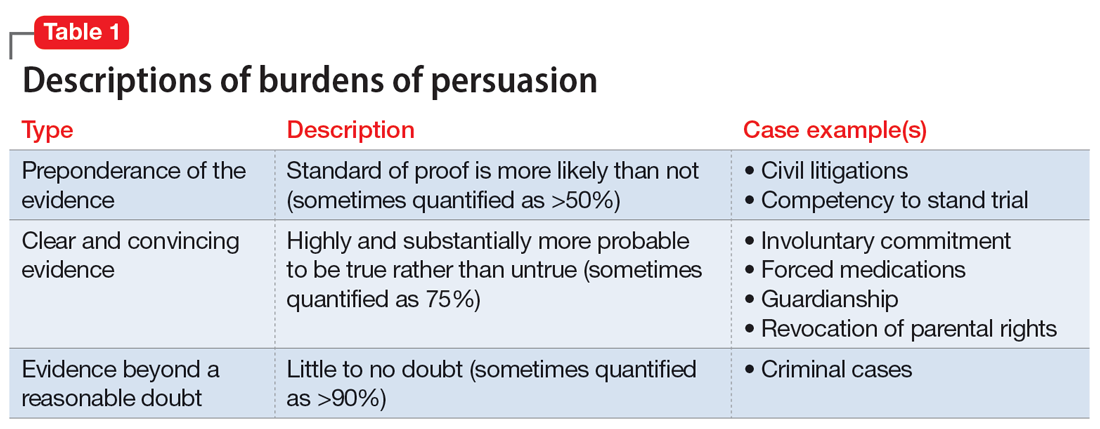

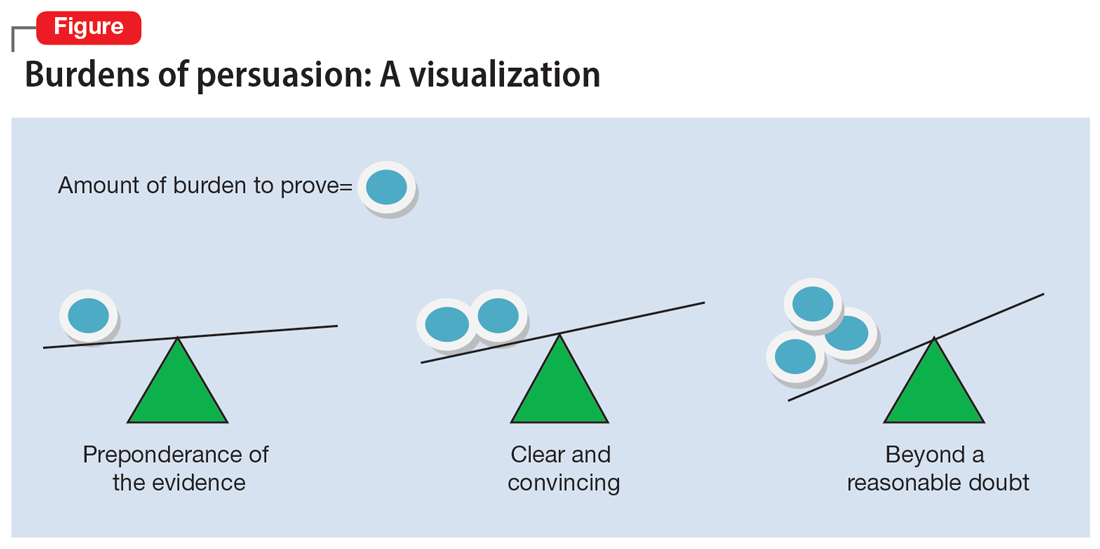

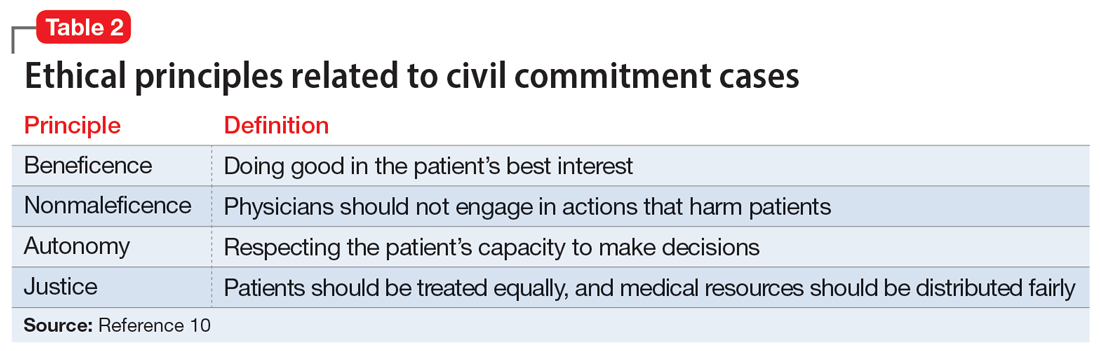

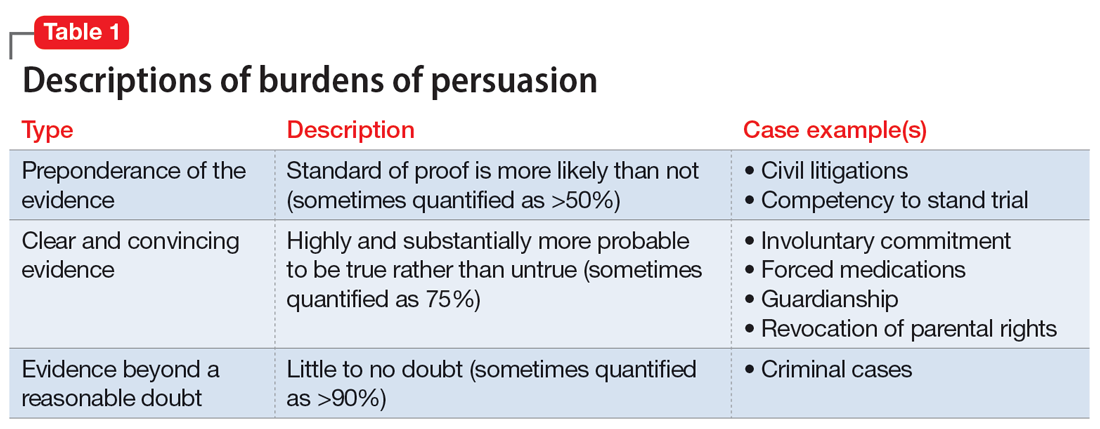

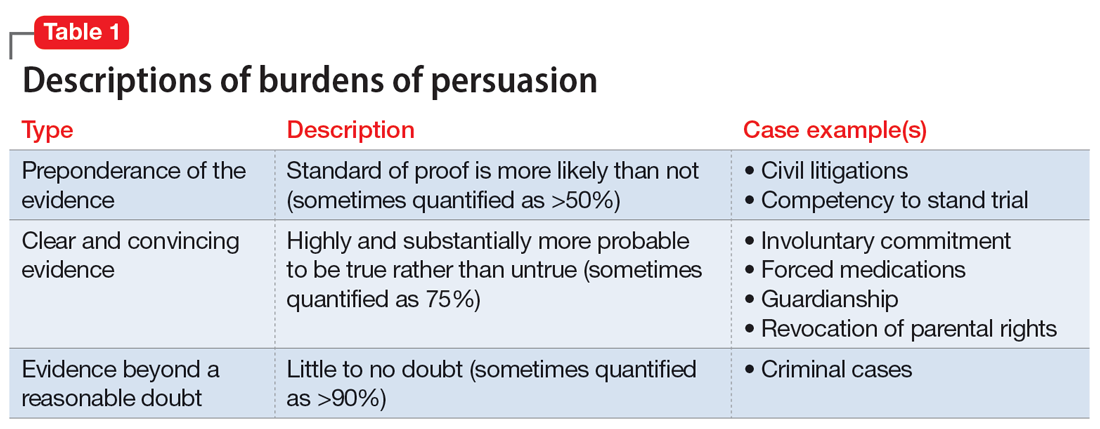

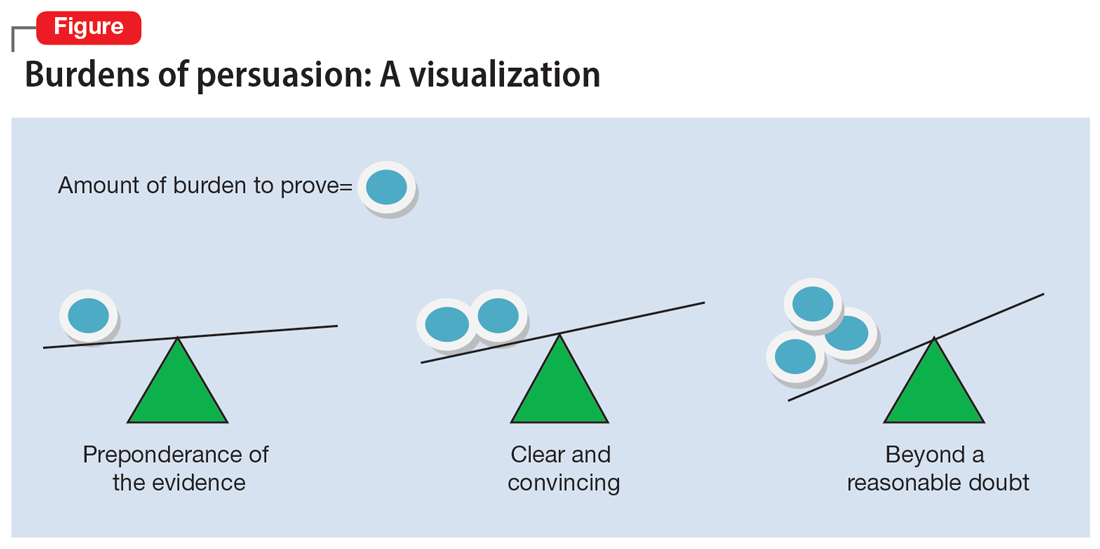

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

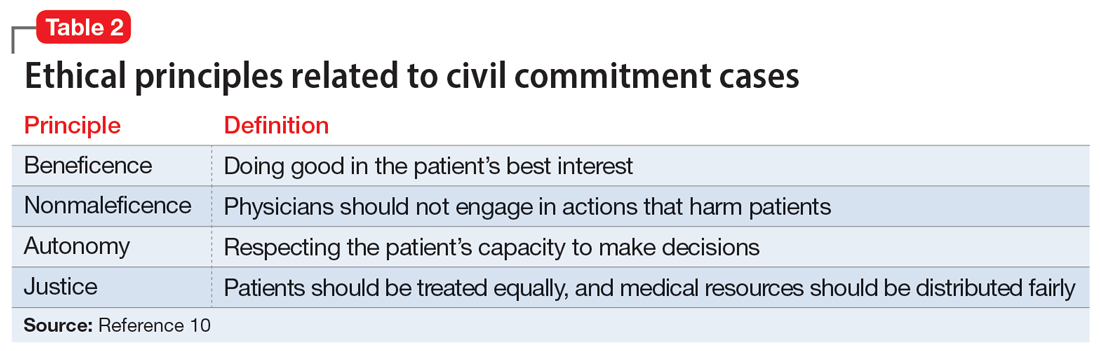

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

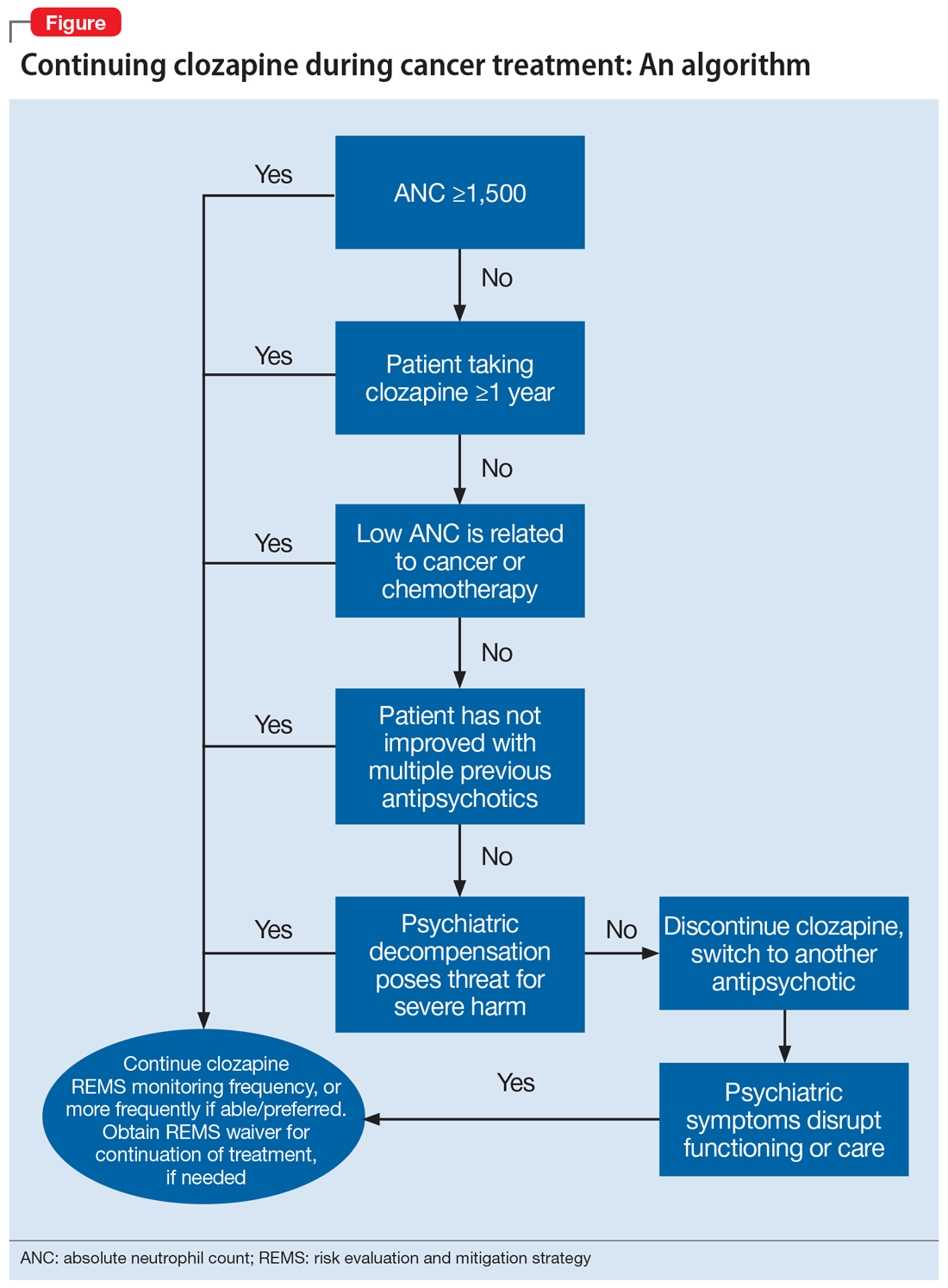

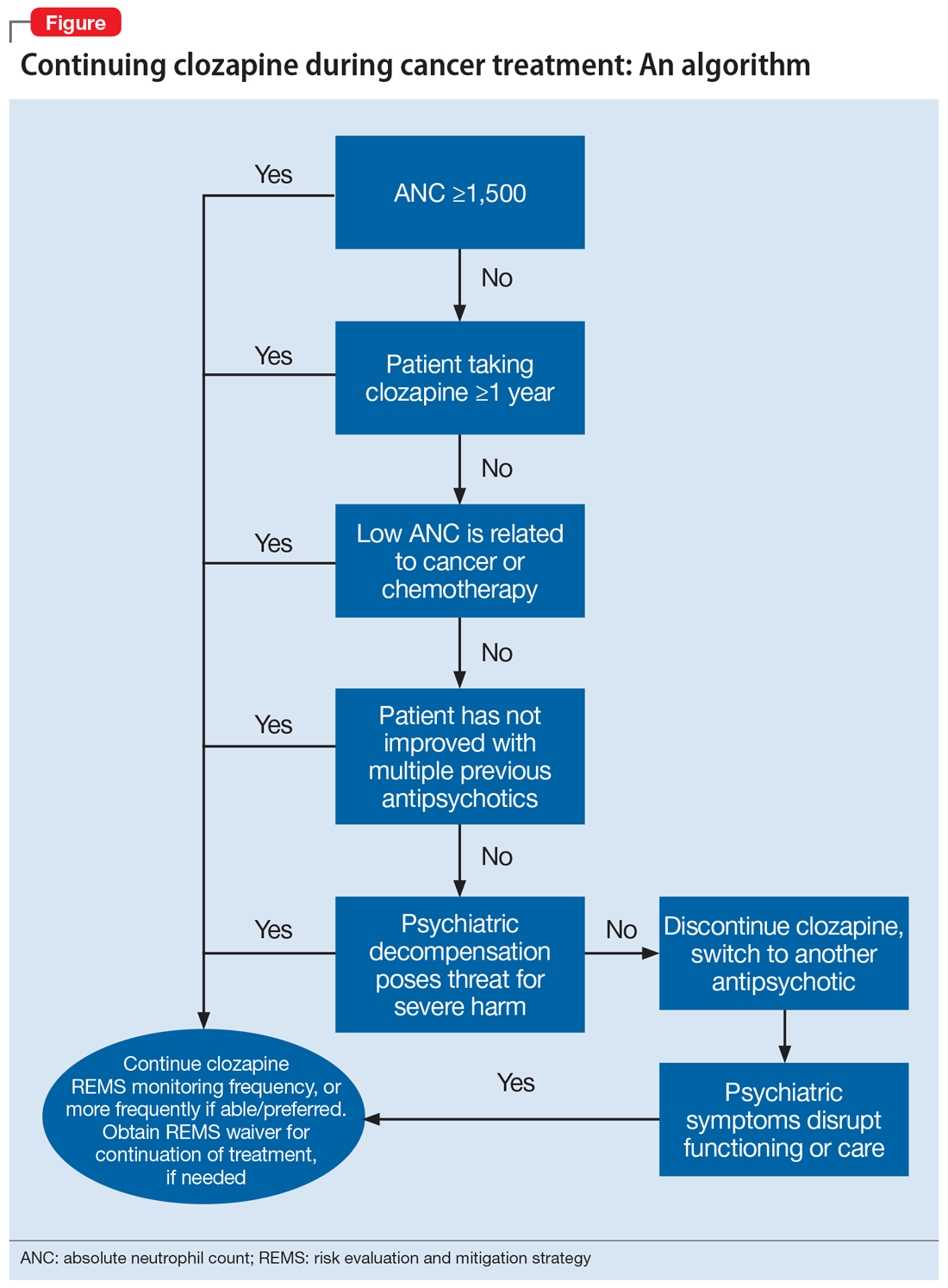

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

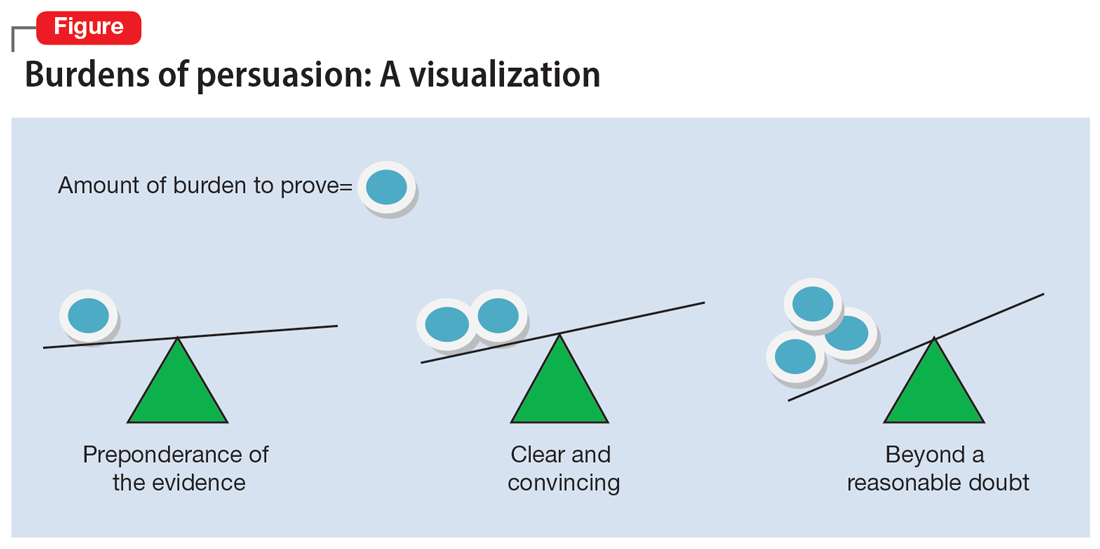

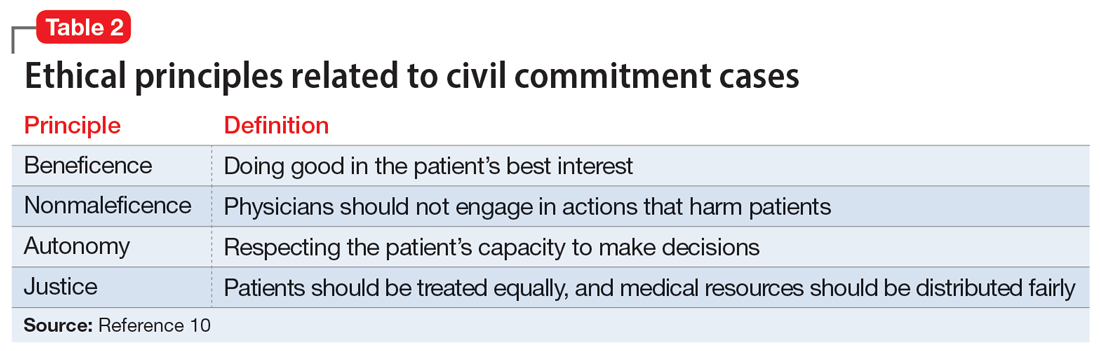

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

Impaired cognition in a patient with schizophrenia and HIV

CASE Psychotic episode in a patient with HIV

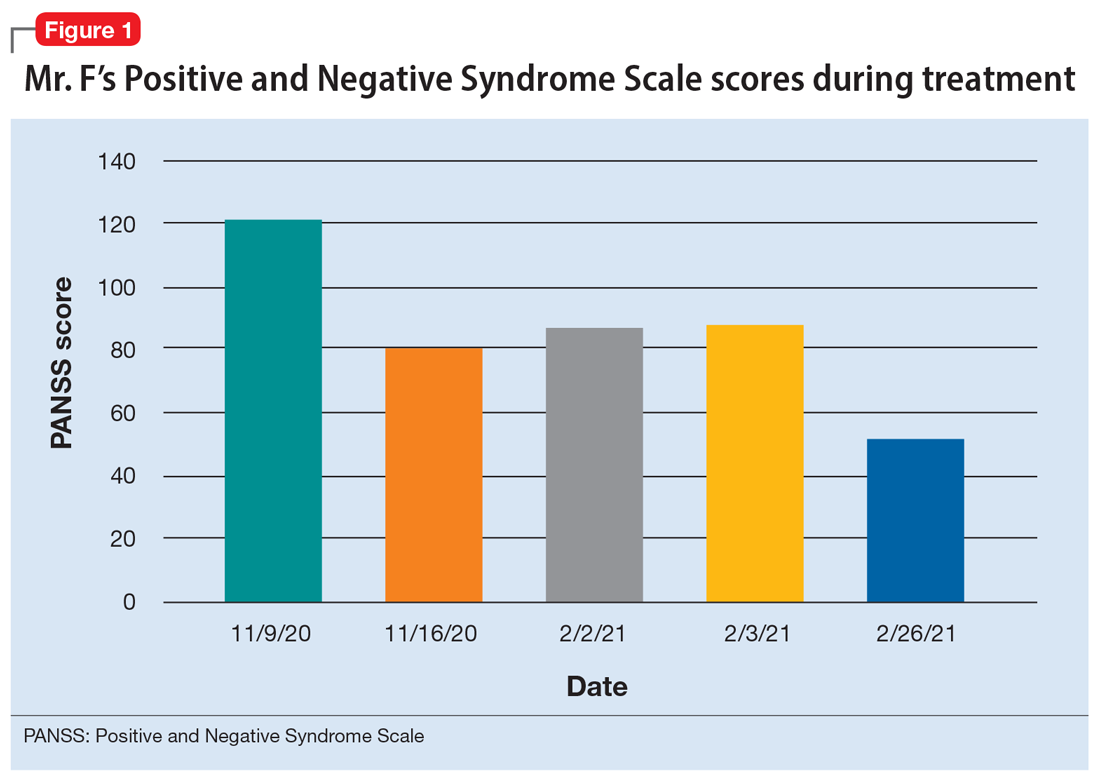

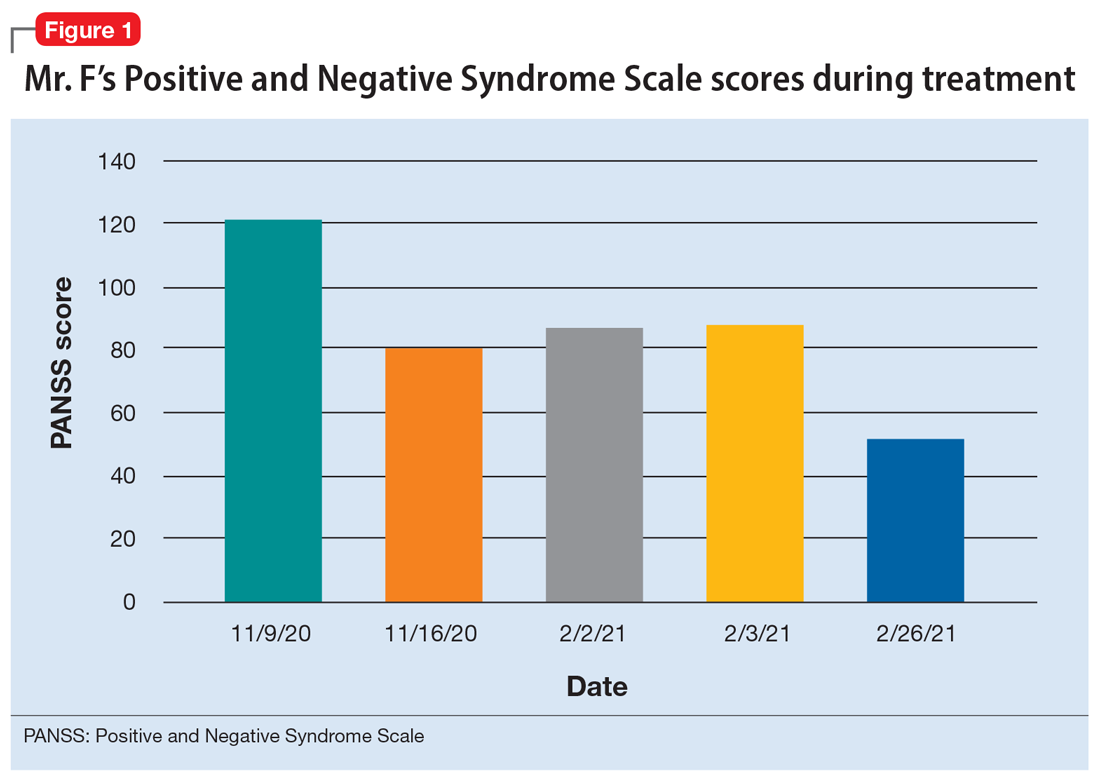

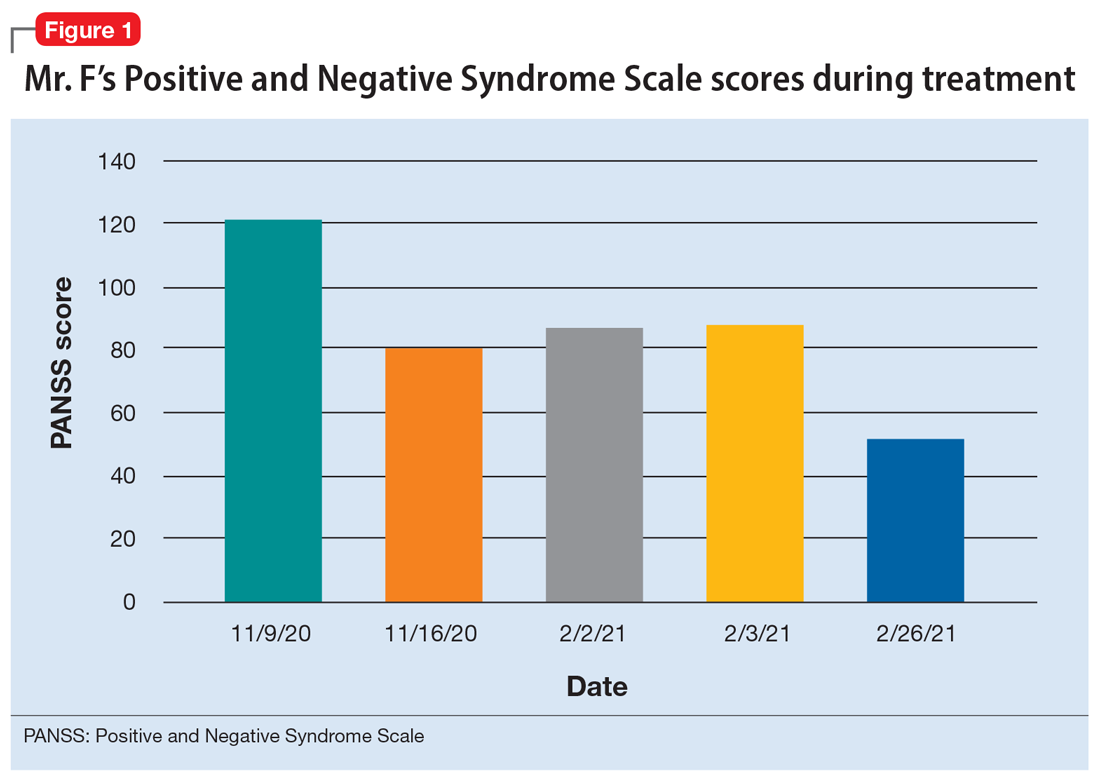

Mr. F, age 32, has schizophrenia and HIV. He presents to the emergency department with auditory and visual hallucinations in addition to paranoia. The treatment team refers him to the state psychiatric facility on an involuntary hold. Mr. F has had multiple previous hospitalizations, none of which had resulted in successful treatment. According to his most recent records, Mr. F failed to improve while taking olanzapine. Upon examination, Mr. F reports he hears command auditory hallucinations to hurt others and endorses paranoia. He is agitated, with a constricted affect, and his thought content is paranoid, disorganized, and circumstantial. Mr. F provides vague and evasive answers upon admission. His physical examination is unremarkable. He has an eighth-grade education level and limited insight into his illnesses. His Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) score is 122, indicating severe symptoms. The PANSS score is formulated based on 30 items, each scored between 1 and 7. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

[polldaddy:11167946]

The authors’ observations

Compared to other medically ill patients, those with AIDS are 7 times more likely to experience EPS associated with antipsychotics. This may be a result of HIV infiltration of the basal ganglia causing regional changes that predispose these patients to EPS.

[polldaddy:11167948]

TREATMENT Haloperidol and antiretroviral therapy

The treatment team decides to start Mr. F on haloperidol for his psychotic symptoms as well as bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir for HIV. One week after admission, the team starts Mr. F on haloperidol decanoate 150 mg IM, and continues oral haloperidol and antiretroviral therapy. Mr. F reports some improvement in his hallucinations and appears to have reduced paranoia. He attends psychotherapy treatment groups over the next several days and scores 80 on a retrospective PANSS assessment (Figure 1). Mr. F receives haloperidol decanoate 200 mg IM 28 days after his first dose, and his oral haloperidol dose is reduced.

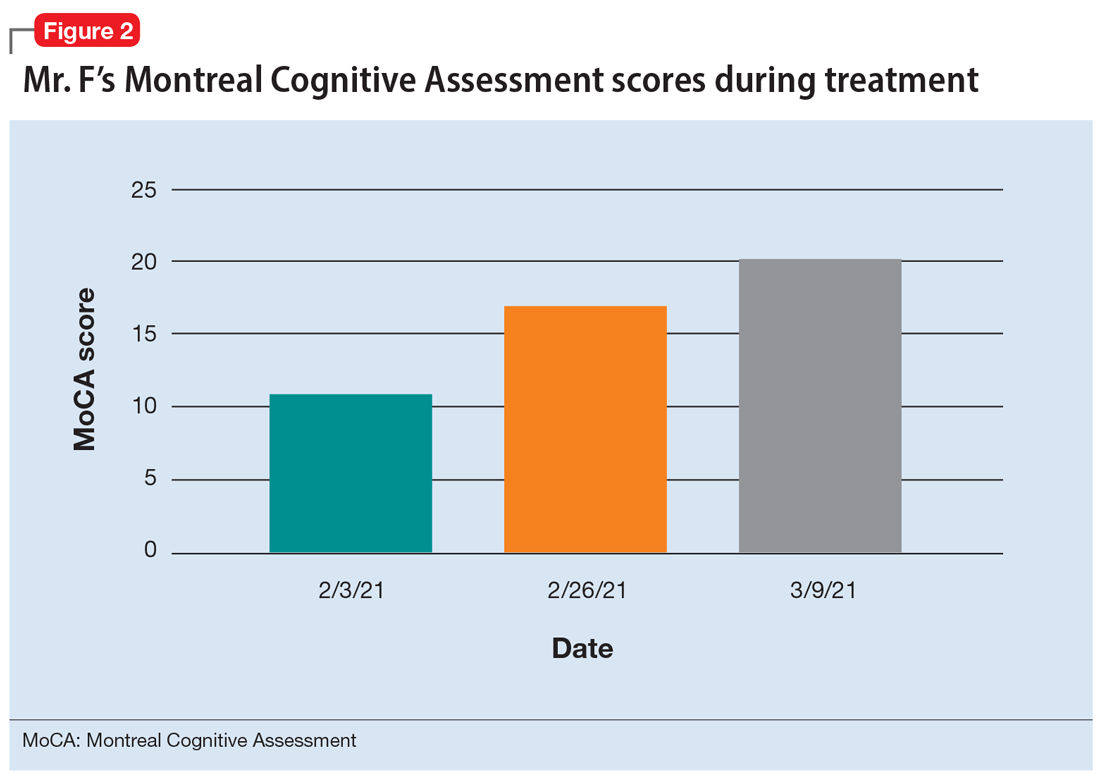

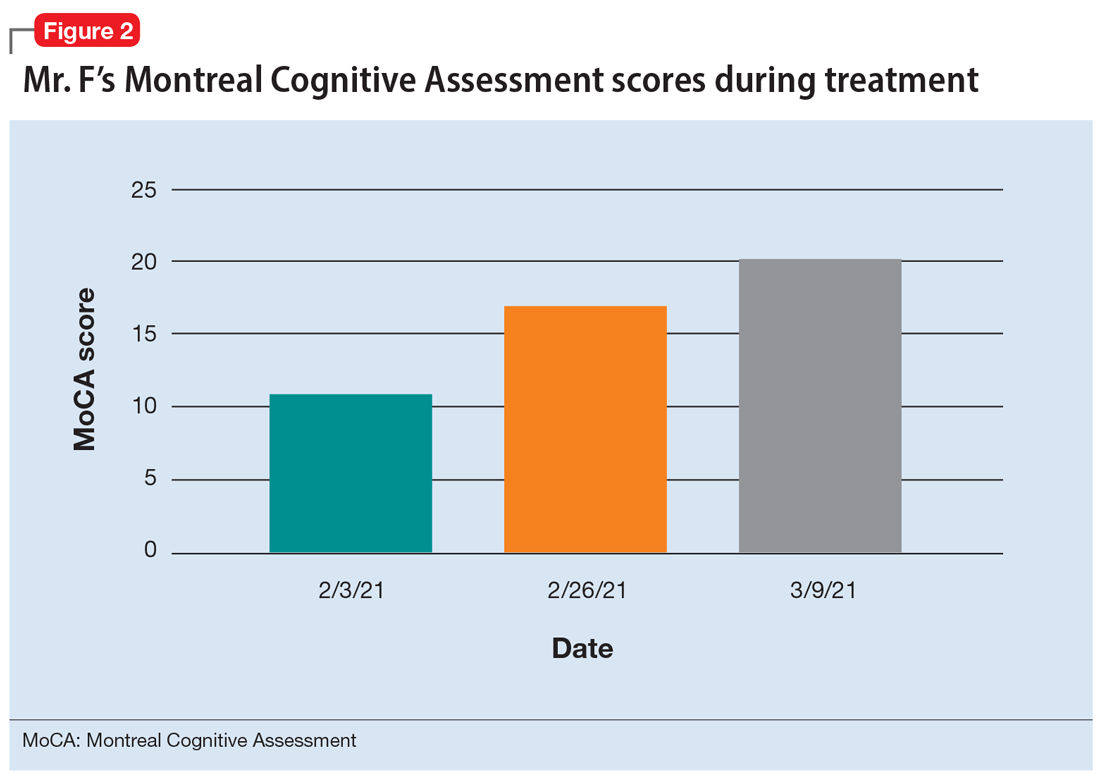

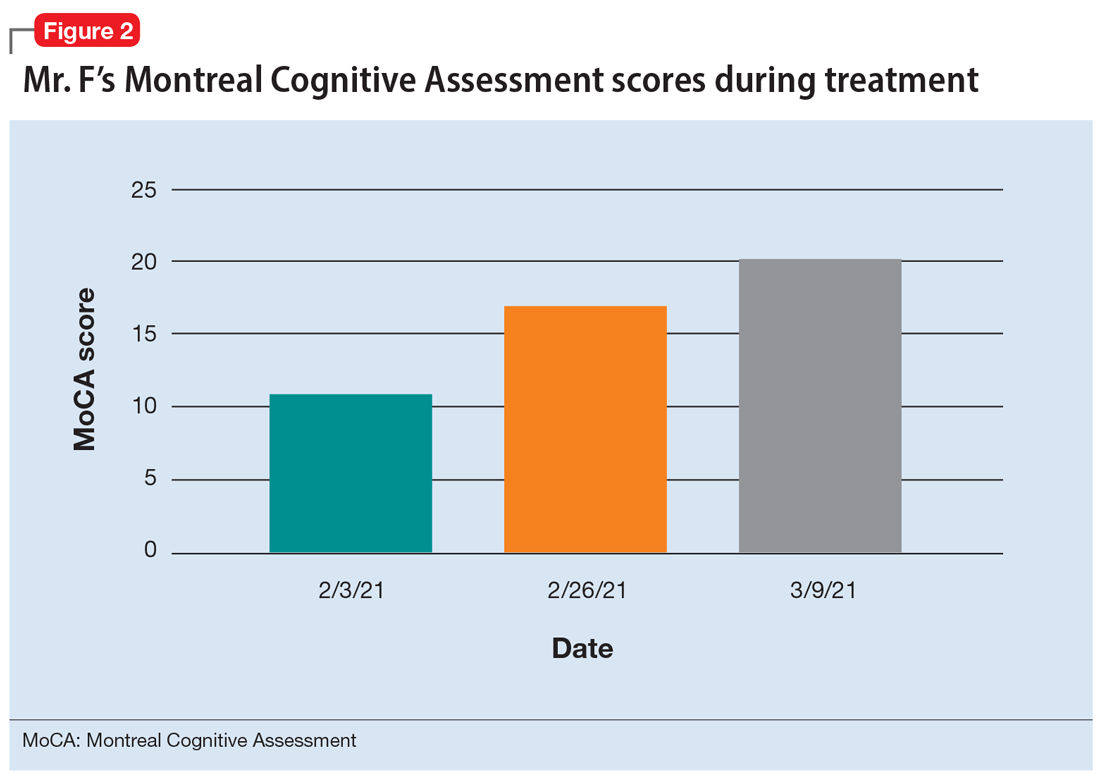

During the following 2 weeks, Mr. F endorses continued improvement of his symptoms and insight and begins discharge planning by calling his sister to discuss living arrangements. However, his mental state begins to decline; he becomes paranoid, withdrawn, and irritable, and endorses increased hallucinations. His PANSS score is 87, and he scores 11 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicating moderate cognitive impairment. MoCA scores range from 0 to 30, with scores <10 indicating severe impairment, 10 to 17 indicating moderate impairment, 18 to 25 indicating mild impairment, and 26 to 30 considered normal. Figure 2 shows a timeline of Mr. F’s MoCA scores during treatment.

The treatment team increases the dose of haloperidol, and Mr. F continues to receive haloperidol deaconate injections monthly. After an adequate trial of haloperidol, the patient exhibits only partial response to treatment—his symptoms wax and wane—and he continues to display limited insight into both his mental illness and HIV diagnosis. Another PANSS assessment yields an essentially unchanged score of 88.

After a discussion of risks and benefits, Mr. F consents to initiating clozapine. The treatment team starts clozapine 25 mg/d and increases the dosage to 400 mg in the evening with a concomitant clozapine level of 487 ng/mL. Mr. F’s absolute neutrophil count was within normal limits (2,500 to 6,000 µL) during this period for weekly complete blood cell count monitoring. Over the next few weeks, his MoCA score increases to 17 and PANSS score decreases to 52. Haloperidol decanoate 200 mg IM is discontinued 3 days after Mr. F received a dose of clozapine 400 mg at bedtime. After an additional 2 weeks of clozapine at the same dosage, Mr. F scores 20 on the MoCA, an increase of 9 points from his baseline score while receiving haloperidol. There is a washout period for haloperidol decanoate and oral haloperidol before he completes a third MoCA. Mr. F participates in a discussion regarding his HIV diagnosis and the importance of consistently continuing treatment for this chronic infection. After some education, he has a better understanding of his condition and is more insightful about wanting to remain compliant with clozapine and bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir for his HIV.

The authors’ observations

Many patients receive treatment for comorbid HIV and schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia and other psychoses are at increased risk of contracting HIV due to numerous psychosocial factors, including an increased frequency of illicit drug use as well as an increased propensity for high-risk sexual behaviors secondary to impaired neurocognitive functioning, delusions, and victimization.1 In addition to deficits in functioning related to psychiatric illness, patients with HIV also experience virus-related neurocognitive insults. After crossing the blood-brain barrier, HIV viral proteins circulate in the blood, inducing brain endothelial cells to release cytokines, causing neuroinflammation.2

Continue to: Recently, inflammation and inflammatory...

Recently, inflammation and inflammatory biomarkers have become an important topic of psychiatric research. A meta-analysis by Fraguas et al3 concluded that greater inflammation and oxidative stress might lead to poorer outcomes in patients with first-episode psychosis. Based on this evidence, inflammation associated with untreated HIV infection may compound the pre-existing neurocognitive decline seen in patients with schizophrenia and other psychoses, thereby contributing to poor outcomes and treatment-resistant pathology.

Clozapine has been the superior treatment for refractory and nonrefractory schizophrenia.4 Factor et al5 report there are limited basal ganglia reserves in patients with HIV, which make clozapine the preferred option due to its low potential for causing EPS.