User login

When a patient with chronic alcohol use abruptly stops drinking

CASE A difficult withdrawal

Three days after he stops drinking alcohol, Mr. G, age 49, presents to a detoxification center with his wife, who drove him there because she was concerned about his condition. She says her husband had been drinking alcohol every night for as long as she can remember. Despite numerous admissions to rehabilitation centers, Mr. G usually would resume drinking soon after he was discharged. Three days ago, Mr. G’s wife had told him she “could not take it anymore,” so he got rid of all his alcohol and stopped drinking. Mr. G’s wife felt he was doing fine the first day, but his condition increasingly worsened the second and third days. The triage nurse who attempts to interview Mr. G finds him tremulous, vomiting, and sweating. She notices that he seems preoccupied with pulling at his shirt, appearing to pick at things that are not there.

HISTORY Untreated depression, other comorbidities

Mr. G’s wife says he has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or exhibited suicidal behavior. Mr. G previously received care from a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with major depressive disorder (MDD) and prescribed an antidepressant, though his wife cannot recall which specific medication. She shares it has been “a long time” since Mr. G has taken the antidepressant and the last time he received treatment for his MDD was 5 years ago. Mr. G’s wife says her husband had once abstained from alcohol use for >6 months following one of his stints at a rehabilitation center. She is not able to share many other details about Mr. G’s previous stays at rehabilitation centers, but says he always had “a rough time.”

She says Mr. G had been drinking an average of 10 drinks each night, usually within 4 hours. He has no history of nicotine or illicit substance use and has held a corporate job for the last 18 years. Several years ago, a physician had diagnosed Mr. G with hypertension and high cholesterol, but he did not follow up for treatment. Mr. G’s wife also recalls a physician told her husband he had a fatty liver. His family history includes heart disease and cancer.

[polldaddy:12041618]

The author’s observations

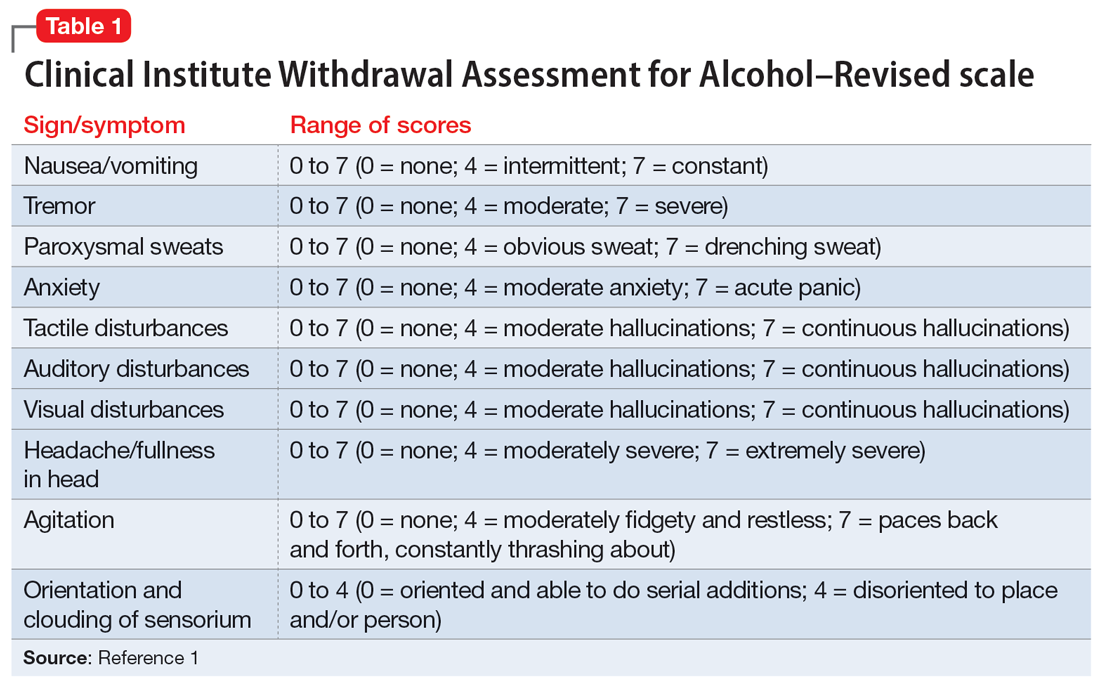

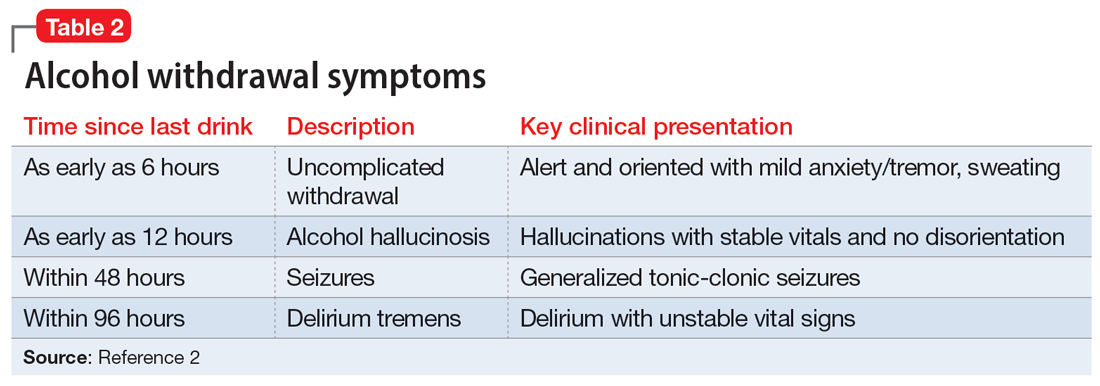

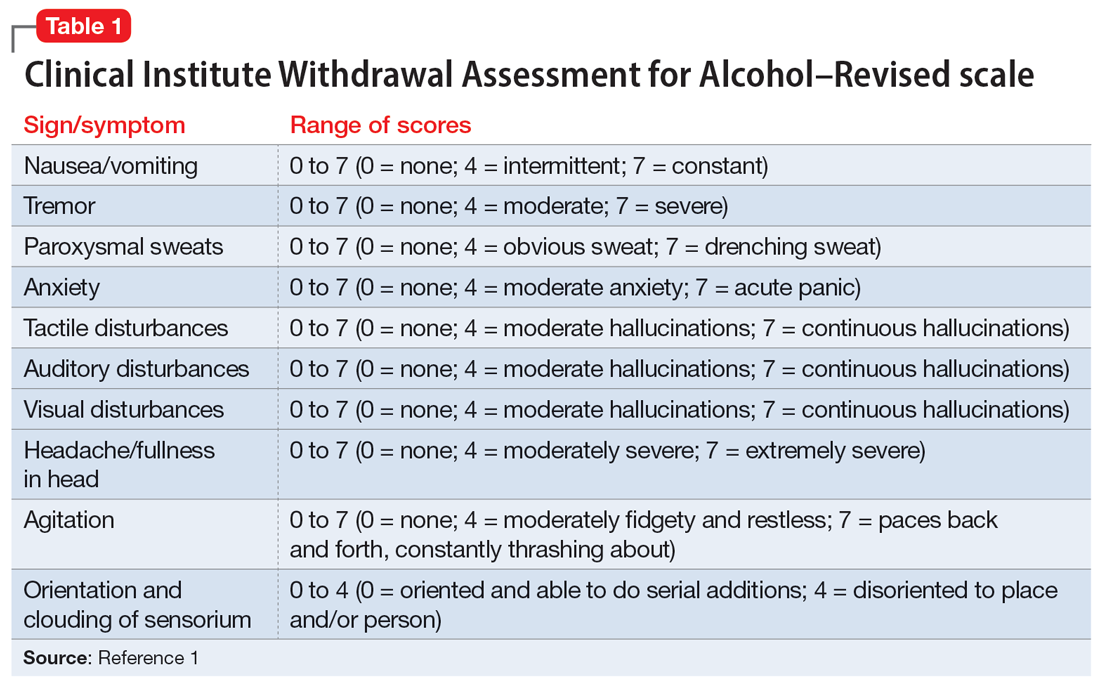

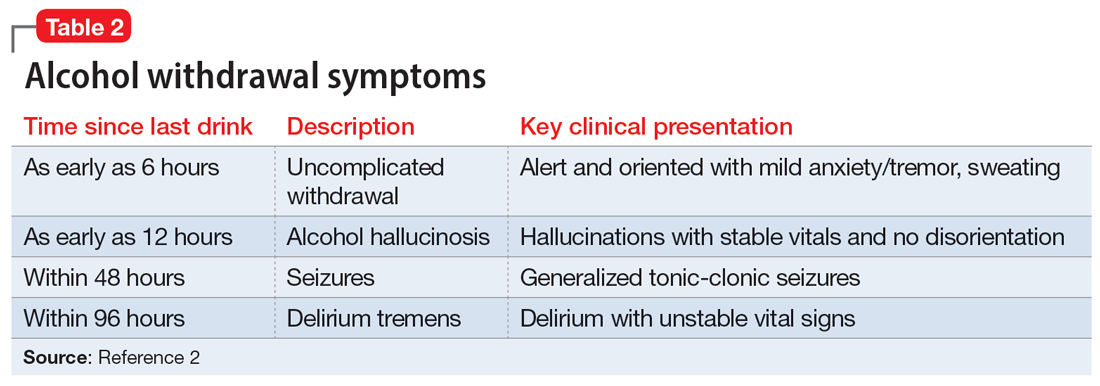

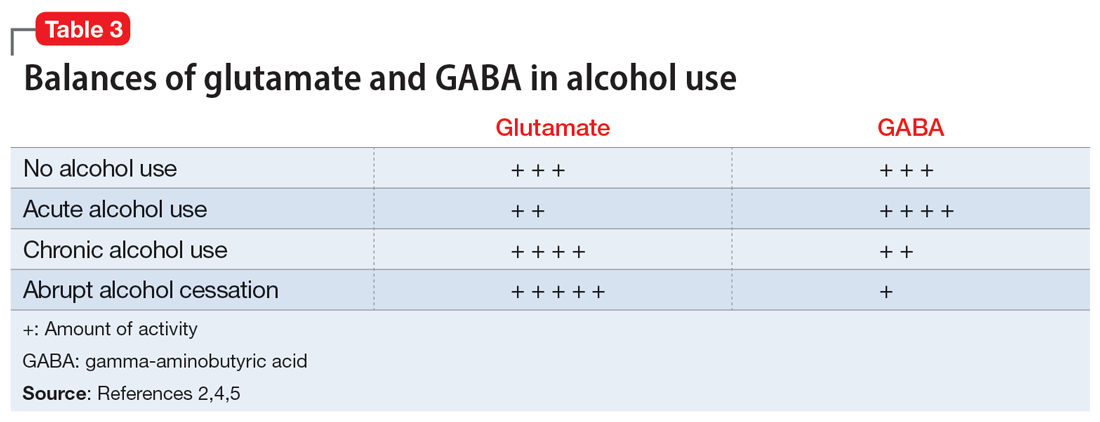

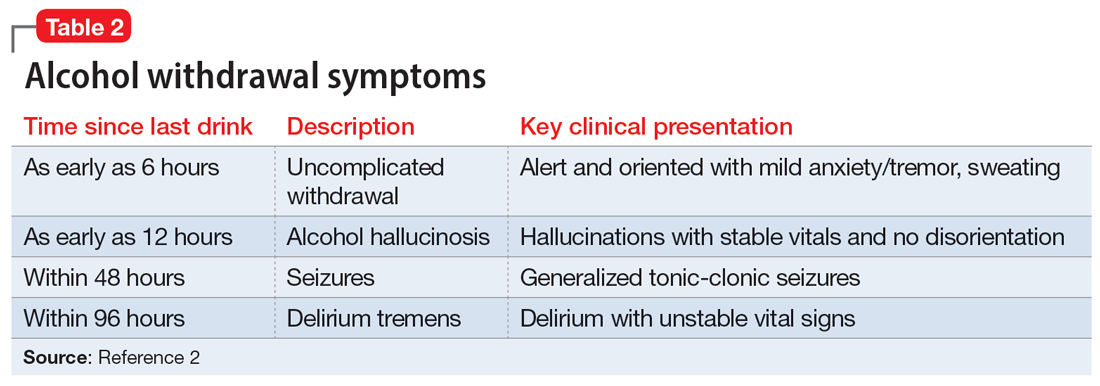

The treatment team observed several elements of alcohol withdrawal and classified Mr. G as a priority patient. If the team had completed the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised scale (CIWA-Ar) (Table 11), Mr. G would score ≥10. While the protocol for initiating treatment for patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal varies by institution, patients with moderate to severe scores on the CIWA-Ar when experiencing withdrawal typically are managed with pharmacotherapy to address their symptoms.1 Given the timeline of his last drink as reported by his wife, Mr. G is on the brink of experiencing a cascade of symptoms concerning for delirium tremens (DTs).2 Table 22 provides a timeline and symptoms related to alcohol withdrawal. To prevent further exacerbation of symptoms, which could lead to DTs, Mr. G’s treatment team will likely initiate a benzodiazepine, using either scheduled or symptom-driven dosing.3

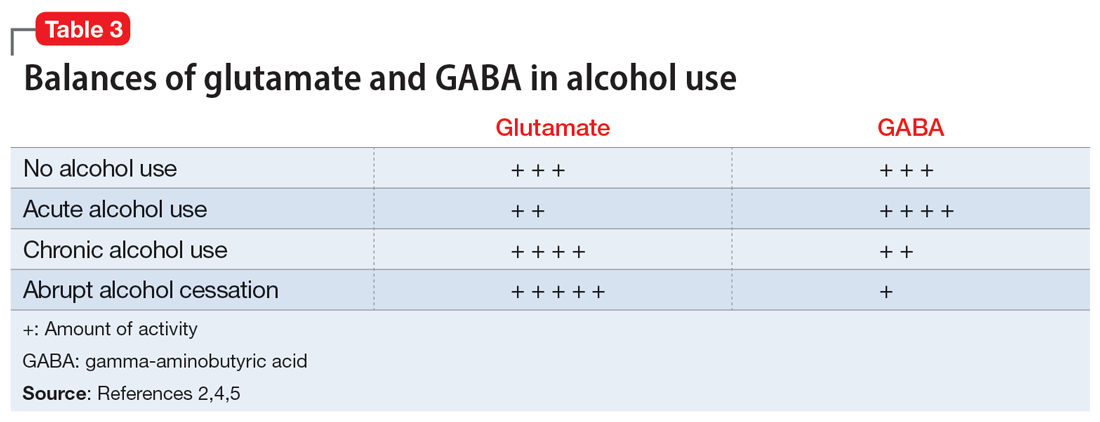

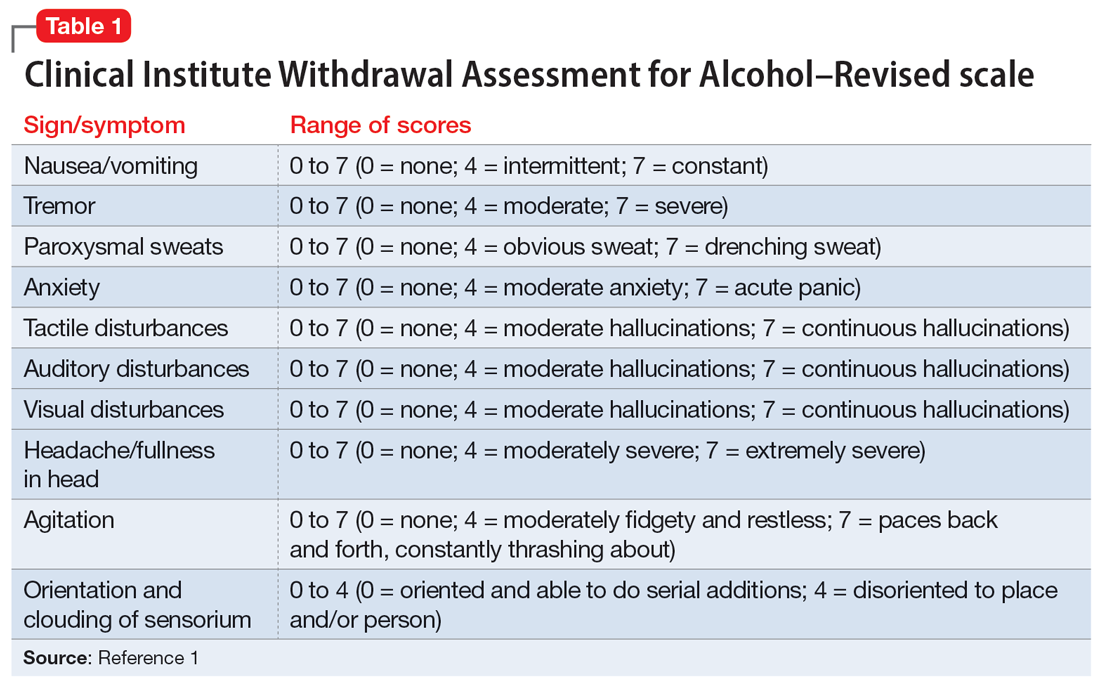

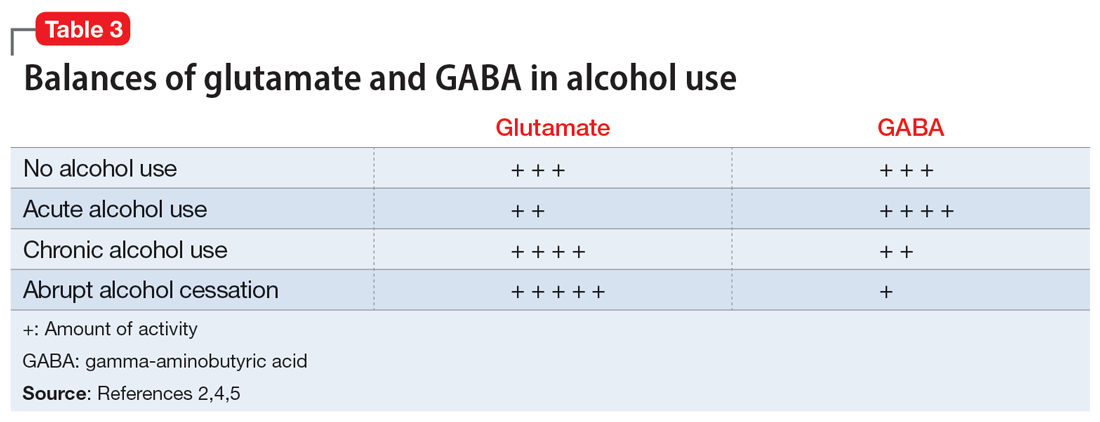

Two neurotransmitters that play a role in DTs are glutamate (excitatory) and GABA (inhibitory). In a normal state, the competing actions of these neurotransmitters balance each other. Acute alcohol intake causes a shift in the excitatory and inhibitory levels, with more inhibition taking place, thus causing disequilibrium. If chronic alcohol use continues, the amount of GABA inhibition reduction is related to downregulation of receptors.2,4 Excitation increases by way of upregulation of the N-methyl-

If alcohol is suddenly removed following chronic use, there is unchecked glutamate excitation related to a blunted GABA state. This added increase in the excitation of glutamate leads to withdrawal symptoms.2,4 Table 32,4,5 depicts the neurotransmitter equilibrium of GABA and glutamate relative to alcohol use.

EVALUATION Bleeding gums and bruising

The treatment team admits Mr. G to the triage bay and contacts the addiction psychiatrist. The physician orders laboratory tests to assess nutritional deficits and electrolyte abnormalities. Mr. G is also placed on routine assessments with symptom-triggered therapy. An assessment reveals bleeding gums and bruises, which are believed to be a result of thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count).

[polldaddy:12041627]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Though regular clinical assessment of PEth varies, it is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity to detect alcohol use.6 When ethanol is present, the phospholipase D enzyme acts upon phosphatidylcholine, forming a direct biomarker, PEth, on the surface of the red blood cell.6,7 PEth’s half-life ranges from 4.5 to 12 days,6 and it can be detected in blood for 3 to 4 weeks after alcohol ingestion.6,7 A PEth value <20 ng/mL indicates light or no alcohol consumption; 20 to 199 ng/mL indicates significant consumption; and >200 ng/mL indicates heavy consumption.7 Since Mr. G has a history of chronic alcohol use, his PEth level is expected to be >200 ng/mL.

AST/ALT and MCV are indirect biomarkers, meaning the tests are not alcohol-specific and the role of alcohol is instead observed by the damage to the body with excessive use over time.7 The expected AST:ALT ratio is 2:1. This is related to 3 mechanisms. The first is a decrease in ALT usually relative to B6 deficiency in individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Another mechanism is related to alcohol’s propensity to affect mitochondria, which is a source for AST. Additionally, AST is also found in higher proportions in the kidneys, heart, and muscles.8

An MCV <100 fL would be within the normal range (80 to 100 fL) for red blood cells. While the reasons for an enlarged red blood cell (or macrocyte) are extensive, alcohol can be a factor once other causes are excluded. Additional laboratory tests and a peripheral blood smear test can help in this investigation. Alcohol disrupts the complete maturation of red blood cells.9,10 If the cause of the macrocyte is alcohol-related and alcohol use is terminated, those enlarged cells can resolve in an average of 3 months.9

Vitamin B1 levels >200 nmol/L would be within normal range (74 to 222 nmol/L). Mr. G’s chronic alcohol use would likely cause him to be vitamin B1–deficient. The deficiency is usually related to diet, malabsorption, and the cells’ impaired ability to utilize vitamin B1. A consequence of vitamin B1 deficiency is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.11

Due to his chronic alcohol use, Mr. G’s magnesium stores most likely would be below normal range (1.7 to 2.2 mg/dL). Acting as a diuretic, alcohol depletes magnesium and other electrolytes. The intracellular shift that occurs to balance the deficit causes the body to use its normal stores of magnesium, which leads to further magnesium depletion. Other common causes include nutritional deficiency and decreased gastrointestinal absorption.12 The bleeding the physician suspected was a result of drinking likely occurred through direct and indirect mechanisms that affect platelets.9,13 Platelets can show improvement 1 week after drinking cessation. Some evidence suggests the risk of seizure or DTs increases significantly with a platelet count <119,000 µL per unit of blood.13

Continue to: TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

As Mr. G’s condition starts to stabilize, he discusses treatment options for AUD with his physician. At the end of the discussion, Mr. G expresses an interest in starting a medication. The doctor reviews his laboratory results and available treatment options.

[polldaddy:12041630]

The author’s observations

Of the 3 FDA-approved medications for treating AUD (disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone), naltrexone has been shown to decrease heavy drinking days5,14 and comes in oral and injectable forms. Reducing drinking is achieved by reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol5,14 and alcohol cravings.5 Disulfiram often has poor adherence, and like acamprosate it may be more helpful for maintenance of abstinence. Neither topiramate nor gabapentin are FDA-approved for AUD but may be used for their affects on GABA.5 Gabapentin may also help patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal syndrome.5,15 Mr. G did not have any concomitant medications or comorbid medical conditions, but these factors as well as any renal or hepatic dysfunction must be considered before initiating any medications.

OUTCOME Improved well-being

Mr. G’s treatment team initiates oral naltrexone 50 mg/d, which he tolerates well without complications. He stops drinking entirely and expresses an interest in transitioning to an injectable form of naltrexone in the future. In addition to taking medication, Mr. G wants to participate in psychotherapy. Mr. G thanks his team for the care he received in the hospital, telling them, “You all saved my life.” As he discusses his past issues with alcohol, Mr. G asks his physician how he could get involved to make changes to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community (Box5,15-21).

Box

Alcohol use disorder is undertreated5,15-17 and excessive alcohol use accounts for 1 in 5 deaths in individuals within Mr. G’s age range.18 An April 2011 report from the Community Preventive Services Task Force19 did not recommend privatization of retail alcohol sales as an intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption, because it would instead lead to an increase in alcohol consumption per capita, a known gateway to excessive alcohol consumption.20

The Task Force was established in 1996 by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Its objective is to identify scientifically proven interventions to save lives, increase lifespans, and improve quality of life. Recommendations are based on systematic reviews to inform lawmakers, health departments, and other organizations and agencies.21 The Task Force’s recommendations were divided into interventions that have strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence. If Mr. G wanted to have the greatest impact in his efforts to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community, the strongest evidence supporting change focuses on electronic screening and brief intervention, maintaining limits on days of alcohol sale, increasing taxes on alcohol, and establishing dram shop liability (laws that hold retail establishments that sell alcohol liable for the injuries or harms caused by their intoxicated or underage customers).19

Bottom Line

Patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal can present with several layers of complexity. Failure to achieve acute stabilization may be life-threatening. After providing critical care, promptly start alcohol use disorder treatment for patients who expresses a desire to change.

Related Resources

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone (injection) • Vivitrol

Naltrexone (oral) • ReVia

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakis IL, et al. Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22(1):61-66.

3. Holleck JL, Merchant N, Gunderson CG. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):1018-1024.

4. Clapp P, Bhave SV, Hoffman PL. How adaptation of the brain to alcohol leads to dependence: a pharmacological perspective. Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(4):310-339.

5. Burnette EM, Nieto SJ, Grodin EN, et al. Novel agents for the pharmacological treatment of alcohol use disorder. Drugs. 2022;82(3):251-274.

6. Selim R, Zhou Y, Rupp LB, et al. Availability of PEth testing is associated with reduced eligibility for liver transplant among patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(5):e14595.

7. Ulwelling W, Smith K. The PEth blood test in the security environment: what it is; why it is important; and interpretative guidelines. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63(6):1634-1640.

8. Botros M, Sikaris KA. The de ritis ratio: the test of time. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34(3):117-130.

9. Ballard HS. The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21(1):42-52.

10. Kaferle J, Strzoda CE. Evaluation of macrocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(3):203-208.

11. Martin PR, Singleton CK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(2):134-142.

12. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Electrolyte disturbances in patients with chronic alcohol-use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1368-1377.

13. Silczuk A, Habrat B. Alcohol-induced thrombocytopenia: current review. Alcohol. 2020;86:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.02.166

14. Pettinati HM, Rabinowitz AR. New pharmacotherapies for treating the neurobiology of alcohol and drug addiction. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(5):14-16.

15. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736.

16. Chockalingam L, Burnham EL, Jolley SE. Medication prescribing for alcohol use disorders during alcohol-related encounters in a Colorado regional healthcare system. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(6):1094-1102.

17. Mintz CM, Hartz SM, Fisher SL, et al. A cascade of care for alcohol use disorder: using 2015-2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data to identify gaps in past 12-month care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45(6):1276-1286.

18. Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among US adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2239485. doi:10.1001/jamanet workopen.2022.39485

19. The Community Guide. CPSTF Findings for Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/task-force-findings-excessive-alcohol-consumption.html

20. The Community Guide. Alcohol Excessive Consumption: Privatization of Retail Alcohol Sales. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-privatization-retail-alcohol-sales.html

21. The Community Guide. What is the CPSTF? Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/what-is-the-cpstf.html

CASE A difficult withdrawal

Three days after he stops drinking alcohol, Mr. G, age 49, presents to a detoxification center with his wife, who drove him there because she was concerned about his condition. She says her husband had been drinking alcohol every night for as long as she can remember. Despite numerous admissions to rehabilitation centers, Mr. G usually would resume drinking soon after he was discharged. Three days ago, Mr. G’s wife had told him she “could not take it anymore,” so he got rid of all his alcohol and stopped drinking. Mr. G’s wife felt he was doing fine the first day, but his condition increasingly worsened the second and third days. The triage nurse who attempts to interview Mr. G finds him tremulous, vomiting, and sweating. She notices that he seems preoccupied with pulling at his shirt, appearing to pick at things that are not there.

HISTORY Untreated depression, other comorbidities

Mr. G’s wife says he has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or exhibited suicidal behavior. Mr. G previously received care from a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with major depressive disorder (MDD) and prescribed an antidepressant, though his wife cannot recall which specific medication. She shares it has been “a long time” since Mr. G has taken the antidepressant and the last time he received treatment for his MDD was 5 years ago. Mr. G’s wife says her husband had once abstained from alcohol use for >6 months following one of his stints at a rehabilitation center. She is not able to share many other details about Mr. G’s previous stays at rehabilitation centers, but says he always had “a rough time.”

She says Mr. G had been drinking an average of 10 drinks each night, usually within 4 hours. He has no history of nicotine or illicit substance use and has held a corporate job for the last 18 years. Several years ago, a physician had diagnosed Mr. G with hypertension and high cholesterol, but he did not follow up for treatment. Mr. G’s wife also recalls a physician told her husband he had a fatty liver. His family history includes heart disease and cancer.

[polldaddy:12041618]

The author’s observations

The treatment team observed several elements of alcohol withdrawal and classified Mr. G as a priority patient. If the team had completed the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised scale (CIWA-Ar) (Table 11), Mr. G would score ≥10. While the protocol for initiating treatment for patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal varies by institution, patients with moderate to severe scores on the CIWA-Ar when experiencing withdrawal typically are managed with pharmacotherapy to address their symptoms.1 Given the timeline of his last drink as reported by his wife, Mr. G is on the brink of experiencing a cascade of symptoms concerning for delirium tremens (DTs).2 Table 22 provides a timeline and symptoms related to alcohol withdrawal. To prevent further exacerbation of symptoms, which could lead to DTs, Mr. G’s treatment team will likely initiate a benzodiazepine, using either scheduled or symptom-driven dosing.3

Two neurotransmitters that play a role in DTs are glutamate (excitatory) and GABA (inhibitory). In a normal state, the competing actions of these neurotransmitters balance each other. Acute alcohol intake causes a shift in the excitatory and inhibitory levels, with more inhibition taking place, thus causing disequilibrium. If chronic alcohol use continues, the amount of GABA inhibition reduction is related to downregulation of receptors.2,4 Excitation increases by way of upregulation of the N-methyl-

If alcohol is suddenly removed following chronic use, there is unchecked glutamate excitation related to a blunted GABA state. This added increase in the excitation of glutamate leads to withdrawal symptoms.2,4 Table 32,4,5 depicts the neurotransmitter equilibrium of GABA and glutamate relative to alcohol use.

EVALUATION Bleeding gums and bruising

The treatment team admits Mr. G to the triage bay and contacts the addiction psychiatrist. The physician orders laboratory tests to assess nutritional deficits and electrolyte abnormalities. Mr. G is also placed on routine assessments with symptom-triggered therapy. An assessment reveals bleeding gums and bruises, which are believed to be a result of thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count).

[polldaddy:12041627]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Though regular clinical assessment of PEth varies, it is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity to detect alcohol use.6 When ethanol is present, the phospholipase D enzyme acts upon phosphatidylcholine, forming a direct biomarker, PEth, on the surface of the red blood cell.6,7 PEth’s half-life ranges from 4.5 to 12 days,6 and it can be detected in blood for 3 to 4 weeks after alcohol ingestion.6,7 A PEth value <20 ng/mL indicates light or no alcohol consumption; 20 to 199 ng/mL indicates significant consumption; and >200 ng/mL indicates heavy consumption.7 Since Mr. G has a history of chronic alcohol use, his PEth level is expected to be >200 ng/mL.

AST/ALT and MCV are indirect biomarkers, meaning the tests are not alcohol-specific and the role of alcohol is instead observed by the damage to the body with excessive use over time.7 The expected AST:ALT ratio is 2:1. This is related to 3 mechanisms. The first is a decrease in ALT usually relative to B6 deficiency in individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Another mechanism is related to alcohol’s propensity to affect mitochondria, which is a source for AST. Additionally, AST is also found in higher proportions in the kidneys, heart, and muscles.8

An MCV <100 fL would be within the normal range (80 to 100 fL) for red blood cells. While the reasons for an enlarged red blood cell (or macrocyte) are extensive, alcohol can be a factor once other causes are excluded. Additional laboratory tests and a peripheral blood smear test can help in this investigation. Alcohol disrupts the complete maturation of red blood cells.9,10 If the cause of the macrocyte is alcohol-related and alcohol use is terminated, those enlarged cells can resolve in an average of 3 months.9

Vitamin B1 levels >200 nmol/L would be within normal range (74 to 222 nmol/L). Mr. G’s chronic alcohol use would likely cause him to be vitamin B1–deficient. The deficiency is usually related to diet, malabsorption, and the cells’ impaired ability to utilize vitamin B1. A consequence of vitamin B1 deficiency is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.11

Due to his chronic alcohol use, Mr. G’s magnesium stores most likely would be below normal range (1.7 to 2.2 mg/dL). Acting as a diuretic, alcohol depletes magnesium and other electrolytes. The intracellular shift that occurs to balance the deficit causes the body to use its normal stores of magnesium, which leads to further magnesium depletion. Other common causes include nutritional deficiency and decreased gastrointestinal absorption.12 The bleeding the physician suspected was a result of drinking likely occurred through direct and indirect mechanisms that affect platelets.9,13 Platelets can show improvement 1 week after drinking cessation. Some evidence suggests the risk of seizure or DTs increases significantly with a platelet count <119,000 µL per unit of blood.13

Continue to: TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

As Mr. G’s condition starts to stabilize, he discusses treatment options for AUD with his physician. At the end of the discussion, Mr. G expresses an interest in starting a medication. The doctor reviews his laboratory results and available treatment options.

[polldaddy:12041630]

The author’s observations

Of the 3 FDA-approved medications for treating AUD (disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone), naltrexone has been shown to decrease heavy drinking days5,14 and comes in oral and injectable forms. Reducing drinking is achieved by reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol5,14 and alcohol cravings.5 Disulfiram often has poor adherence, and like acamprosate it may be more helpful for maintenance of abstinence. Neither topiramate nor gabapentin are FDA-approved for AUD but may be used for their affects on GABA.5 Gabapentin may also help patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal syndrome.5,15 Mr. G did not have any concomitant medications or comorbid medical conditions, but these factors as well as any renal or hepatic dysfunction must be considered before initiating any medications.

OUTCOME Improved well-being

Mr. G’s treatment team initiates oral naltrexone 50 mg/d, which he tolerates well without complications. He stops drinking entirely and expresses an interest in transitioning to an injectable form of naltrexone in the future. In addition to taking medication, Mr. G wants to participate in psychotherapy. Mr. G thanks his team for the care he received in the hospital, telling them, “You all saved my life.” As he discusses his past issues with alcohol, Mr. G asks his physician how he could get involved to make changes to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community (Box5,15-21).

Box

Alcohol use disorder is undertreated5,15-17 and excessive alcohol use accounts for 1 in 5 deaths in individuals within Mr. G’s age range.18 An April 2011 report from the Community Preventive Services Task Force19 did not recommend privatization of retail alcohol sales as an intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption, because it would instead lead to an increase in alcohol consumption per capita, a known gateway to excessive alcohol consumption.20

The Task Force was established in 1996 by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Its objective is to identify scientifically proven interventions to save lives, increase lifespans, and improve quality of life. Recommendations are based on systematic reviews to inform lawmakers, health departments, and other organizations and agencies.21 The Task Force’s recommendations were divided into interventions that have strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence. If Mr. G wanted to have the greatest impact in his efforts to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community, the strongest evidence supporting change focuses on electronic screening and brief intervention, maintaining limits on days of alcohol sale, increasing taxes on alcohol, and establishing dram shop liability (laws that hold retail establishments that sell alcohol liable for the injuries or harms caused by their intoxicated or underage customers).19

Bottom Line

Patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal can present with several layers of complexity. Failure to achieve acute stabilization may be life-threatening. After providing critical care, promptly start alcohol use disorder treatment for patients who expresses a desire to change.

Related Resources

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone (injection) • Vivitrol

Naltrexone (oral) • ReVia

Topiramate • Topamax

CASE A difficult withdrawal

Three days after he stops drinking alcohol, Mr. G, age 49, presents to a detoxification center with his wife, who drove him there because she was concerned about his condition. She says her husband had been drinking alcohol every night for as long as she can remember. Despite numerous admissions to rehabilitation centers, Mr. G usually would resume drinking soon after he was discharged. Three days ago, Mr. G’s wife had told him she “could not take it anymore,” so he got rid of all his alcohol and stopped drinking. Mr. G’s wife felt he was doing fine the first day, but his condition increasingly worsened the second and third days. The triage nurse who attempts to interview Mr. G finds him tremulous, vomiting, and sweating. She notices that he seems preoccupied with pulling at his shirt, appearing to pick at things that are not there.

HISTORY Untreated depression, other comorbidities

Mr. G’s wife says he has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or exhibited suicidal behavior. Mr. G previously received care from a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with major depressive disorder (MDD) and prescribed an antidepressant, though his wife cannot recall which specific medication. She shares it has been “a long time” since Mr. G has taken the antidepressant and the last time he received treatment for his MDD was 5 years ago. Mr. G’s wife says her husband had once abstained from alcohol use for >6 months following one of his stints at a rehabilitation center. She is not able to share many other details about Mr. G’s previous stays at rehabilitation centers, but says he always had “a rough time.”

She says Mr. G had been drinking an average of 10 drinks each night, usually within 4 hours. He has no history of nicotine or illicit substance use and has held a corporate job for the last 18 years. Several years ago, a physician had diagnosed Mr. G with hypertension and high cholesterol, but he did not follow up for treatment. Mr. G’s wife also recalls a physician told her husband he had a fatty liver. His family history includes heart disease and cancer.

[polldaddy:12041618]

The author’s observations

The treatment team observed several elements of alcohol withdrawal and classified Mr. G as a priority patient. If the team had completed the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised scale (CIWA-Ar) (Table 11), Mr. G would score ≥10. While the protocol for initiating treatment for patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal varies by institution, patients with moderate to severe scores on the CIWA-Ar when experiencing withdrawal typically are managed with pharmacotherapy to address their symptoms.1 Given the timeline of his last drink as reported by his wife, Mr. G is on the brink of experiencing a cascade of symptoms concerning for delirium tremens (DTs).2 Table 22 provides a timeline and symptoms related to alcohol withdrawal. To prevent further exacerbation of symptoms, which could lead to DTs, Mr. G’s treatment team will likely initiate a benzodiazepine, using either scheduled or symptom-driven dosing.3

Two neurotransmitters that play a role in DTs are glutamate (excitatory) and GABA (inhibitory). In a normal state, the competing actions of these neurotransmitters balance each other. Acute alcohol intake causes a shift in the excitatory and inhibitory levels, with more inhibition taking place, thus causing disequilibrium. If chronic alcohol use continues, the amount of GABA inhibition reduction is related to downregulation of receptors.2,4 Excitation increases by way of upregulation of the N-methyl-

If alcohol is suddenly removed following chronic use, there is unchecked glutamate excitation related to a blunted GABA state. This added increase in the excitation of glutamate leads to withdrawal symptoms.2,4 Table 32,4,5 depicts the neurotransmitter equilibrium of GABA and glutamate relative to alcohol use.

EVALUATION Bleeding gums and bruising

The treatment team admits Mr. G to the triage bay and contacts the addiction psychiatrist. The physician orders laboratory tests to assess nutritional deficits and electrolyte abnormalities. Mr. G is also placed on routine assessments with symptom-triggered therapy. An assessment reveals bleeding gums and bruises, which are believed to be a result of thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count).

[polldaddy:12041627]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Though regular clinical assessment of PEth varies, it is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity to detect alcohol use.6 When ethanol is present, the phospholipase D enzyme acts upon phosphatidylcholine, forming a direct biomarker, PEth, on the surface of the red blood cell.6,7 PEth’s half-life ranges from 4.5 to 12 days,6 and it can be detected in blood for 3 to 4 weeks after alcohol ingestion.6,7 A PEth value <20 ng/mL indicates light or no alcohol consumption; 20 to 199 ng/mL indicates significant consumption; and >200 ng/mL indicates heavy consumption.7 Since Mr. G has a history of chronic alcohol use, his PEth level is expected to be >200 ng/mL.

AST/ALT and MCV are indirect biomarkers, meaning the tests are not alcohol-specific and the role of alcohol is instead observed by the damage to the body with excessive use over time.7 The expected AST:ALT ratio is 2:1. This is related to 3 mechanisms. The first is a decrease in ALT usually relative to B6 deficiency in individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Another mechanism is related to alcohol’s propensity to affect mitochondria, which is a source for AST. Additionally, AST is also found in higher proportions in the kidneys, heart, and muscles.8

An MCV <100 fL would be within the normal range (80 to 100 fL) for red blood cells. While the reasons for an enlarged red blood cell (or macrocyte) are extensive, alcohol can be a factor once other causes are excluded. Additional laboratory tests and a peripheral blood smear test can help in this investigation. Alcohol disrupts the complete maturation of red blood cells.9,10 If the cause of the macrocyte is alcohol-related and alcohol use is terminated, those enlarged cells can resolve in an average of 3 months.9

Vitamin B1 levels >200 nmol/L would be within normal range (74 to 222 nmol/L). Mr. G’s chronic alcohol use would likely cause him to be vitamin B1–deficient. The deficiency is usually related to diet, malabsorption, and the cells’ impaired ability to utilize vitamin B1. A consequence of vitamin B1 deficiency is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.11

Due to his chronic alcohol use, Mr. G’s magnesium stores most likely would be below normal range (1.7 to 2.2 mg/dL). Acting as a diuretic, alcohol depletes magnesium and other electrolytes. The intracellular shift that occurs to balance the deficit causes the body to use its normal stores of magnesium, which leads to further magnesium depletion. Other common causes include nutritional deficiency and decreased gastrointestinal absorption.12 The bleeding the physician suspected was a result of drinking likely occurred through direct and indirect mechanisms that affect platelets.9,13 Platelets can show improvement 1 week after drinking cessation. Some evidence suggests the risk of seizure or DTs increases significantly with a platelet count <119,000 µL per unit of blood.13

Continue to: TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

As Mr. G’s condition starts to stabilize, he discusses treatment options for AUD with his physician. At the end of the discussion, Mr. G expresses an interest in starting a medication. The doctor reviews his laboratory results and available treatment options.

[polldaddy:12041630]

The author’s observations

Of the 3 FDA-approved medications for treating AUD (disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone), naltrexone has been shown to decrease heavy drinking days5,14 and comes in oral and injectable forms. Reducing drinking is achieved by reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol5,14 and alcohol cravings.5 Disulfiram often has poor adherence, and like acamprosate it may be more helpful for maintenance of abstinence. Neither topiramate nor gabapentin are FDA-approved for AUD but may be used for their affects on GABA.5 Gabapentin may also help patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal syndrome.5,15 Mr. G did not have any concomitant medications or comorbid medical conditions, but these factors as well as any renal or hepatic dysfunction must be considered before initiating any medications.

OUTCOME Improved well-being

Mr. G’s treatment team initiates oral naltrexone 50 mg/d, which he tolerates well without complications. He stops drinking entirely and expresses an interest in transitioning to an injectable form of naltrexone in the future. In addition to taking medication, Mr. G wants to participate in psychotherapy. Mr. G thanks his team for the care he received in the hospital, telling them, “You all saved my life.” As he discusses his past issues with alcohol, Mr. G asks his physician how he could get involved to make changes to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community (Box5,15-21).

Box

Alcohol use disorder is undertreated5,15-17 and excessive alcohol use accounts for 1 in 5 deaths in individuals within Mr. G’s age range.18 An April 2011 report from the Community Preventive Services Task Force19 did not recommend privatization of retail alcohol sales as an intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption, because it would instead lead to an increase in alcohol consumption per capita, a known gateway to excessive alcohol consumption.20

The Task Force was established in 1996 by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Its objective is to identify scientifically proven interventions to save lives, increase lifespans, and improve quality of life. Recommendations are based on systematic reviews to inform lawmakers, health departments, and other organizations and agencies.21 The Task Force’s recommendations were divided into interventions that have strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence. If Mr. G wanted to have the greatest impact in his efforts to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community, the strongest evidence supporting change focuses on electronic screening and brief intervention, maintaining limits on days of alcohol sale, increasing taxes on alcohol, and establishing dram shop liability (laws that hold retail establishments that sell alcohol liable for the injuries or harms caused by their intoxicated or underage customers).19

Bottom Line

Patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal can present with several layers of complexity. Failure to achieve acute stabilization may be life-threatening. After providing critical care, promptly start alcohol use disorder treatment for patients who expresses a desire to change.

Related Resources

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone (injection) • Vivitrol

Naltrexone (oral) • ReVia

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakis IL, et al. Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22(1):61-66.

3. Holleck JL, Merchant N, Gunderson CG. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):1018-1024.

4. Clapp P, Bhave SV, Hoffman PL. How adaptation of the brain to alcohol leads to dependence: a pharmacological perspective. Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(4):310-339.

5. Burnette EM, Nieto SJ, Grodin EN, et al. Novel agents for the pharmacological treatment of alcohol use disorder. Drugs. 2022;82(3):251-274.

6. Selim R, Zhou Y, Rupp LB, et al. Availability of PEth testing is associated with reduced eligibility for liver transplant among patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(5):e14595.

7. Ulwelling W, Smith K. The PEth blood test in the security environment: what it is; why it is important; and interpretative guidelines. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63(6):1634-1640.

8. Botros M, Sikaris KA. The de ritis ratio: the test of time. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34(3):117-130.

9. Ballard HS. The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21(1):42-52.

10. Kaferle J, Strzoda CE. Evaluation of macrocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(3):203-208.

11. Martin PR, Singleton CK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(2):134-142.

12. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Electrolyte disturbances in patients with chronic alcohol-use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1368-1377.

13. Silczuk A, Habrat B. Alcohol-induced thrombocytopenia: current review. Alcohol. 2020;86:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.02.166

14. Pettinati HM, Rabinowitz AR. New pharmacotherapies for treating the neurobiology of alcohol and drug addiction. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(5):14-16.

15. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736.

16. Chockalingam L, Burnham EL, Jolley SE. Medication prescribing for alcohol use disorders during alcohol-related encounters in a Colorado regional healthcare system. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(6):1094-1102.

17. Mintz CM, Hartz SM, Fisher SL, et al. A cascade of care for alcohol use disorder: using 2015-2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data to identify gaps in past 12-month care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45(6):1276-1286.

18. Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among US adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2239485. doi:10.1001/jamanet workopen.2022.39485

19. The Community Guide. CPSTF Findings for Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/task-force-findings-excessive-alcohol-consumption.html

20. The Community Guide. Alcohol Excessive Consumption: Privatization of Retail Alcohol Sales. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-privatization-retail-alcohol-sales.html

21. The Community Guide. What is the CPSTF? Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/what-is-the-cpstf.html

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakis IL, et al. Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22(1):61-66.

3. Holleck JL, Merchant N, Gunderson CG. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):1018-1024.

4. Clapp P, Bhave SV, Hoffman PL. How adaptation of the brain to alcohol leads to dependence: a pharmacological perspective. Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(4):310-339.

5. Burnette EM, Nieto SJ, Grodin EN, et al. Novel agents for the pharmacological treatment of alcohol use disorder. Drugs. 2022;82(3):251-274.

6. Selim R, Zhou Y, Rupp LB, et al. Availability of PEth testing is associated with reduced eligibility for liver transplant among patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(5):e14595.

7. Ulwelling W, Smith K. The PEth blood test in the security environment: what it is; why it is important; and interpretative guidelines. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63(6):1634-1640.

8. Botros M, Sikaris KA. The de ritis ratio: the test of time. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34(3):117-130.

9. Ballard HS. The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21(1):42-52.

10. Kaferle J, Strzoda CE. Evaluation of macrocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(3):203-208.

11. Martin PR, Singleton CK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(2):134-142.

12. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Electrolyte disturbances in patients with chronic alcohol-use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1368-1377.

13. Silczuk A, Habrat B. Alcohol-induced thrombocytopenia: current review. Alcohol. 2020;86:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.02.166

14. Pettinati HM, Rabinowitz AR. New pharmacotherapies for treating the neurobiology of alcohol and drug addiction. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(5):14-16.

15. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736.

16. Chockalingam L, Burnham EL, Jolley SE. Medication prescribing for alcohol use disorders during alcohol-related encounters in a Colorado regional healthcare system. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(6):1094-1102.

17. Mintz CM, Hartz SM, Fisher SL, et al. A cascade of care for alcohol use disorder: using 2015-2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data to identify gaps in past 12-month care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45(6):1276-1286.

18. Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among US adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2239485. doi:10.1001/jamanet workopen.2022.39485

19. The Community Guide. CPSTF Findings for Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/task-force-findings-excessive-alcohol-consumption.html

20. The Community Guide. Alcohol Excessive Consumption: Privatization of Retail Alcohol Sales. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-privatization-retail-alcohol-sales.html

21. The Community Guide. What is the CPSTF? Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/what-is-the-cpstf.html

Hold or not to hold: Navigating involuntary commitment

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

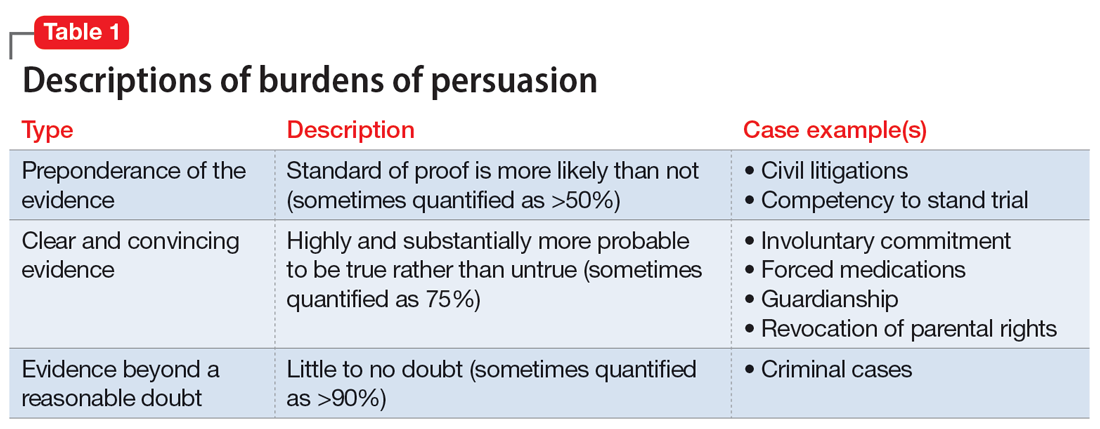

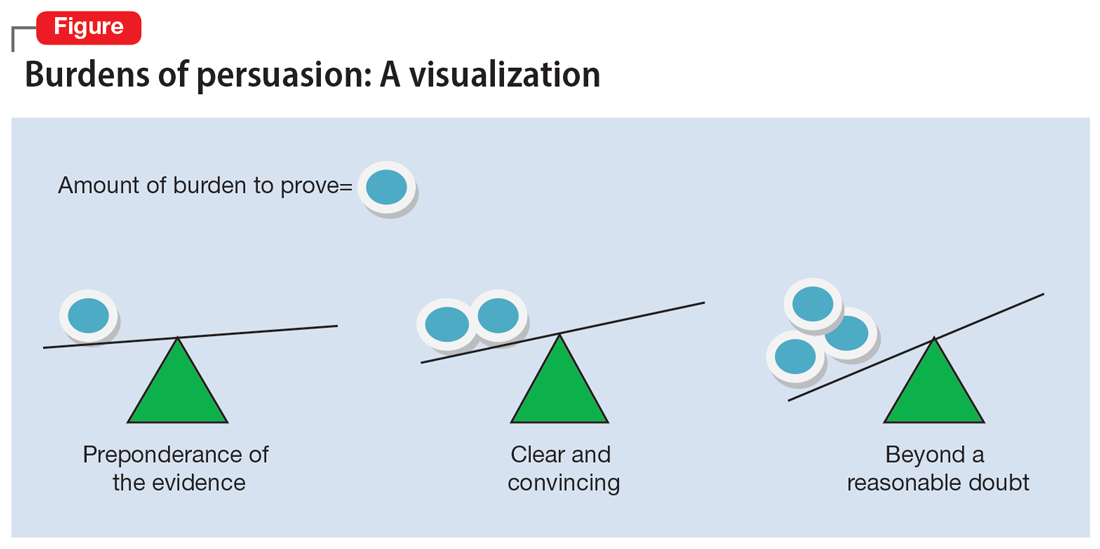

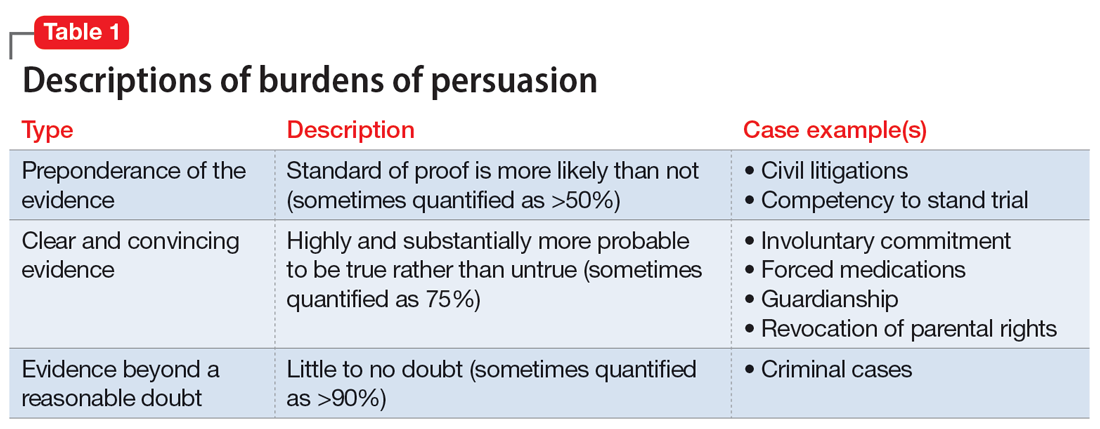

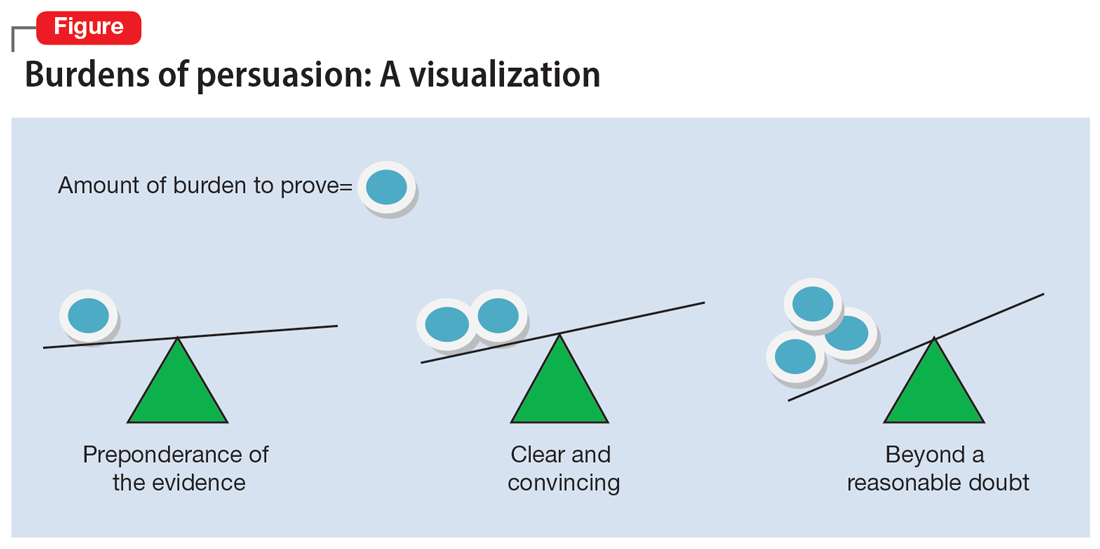

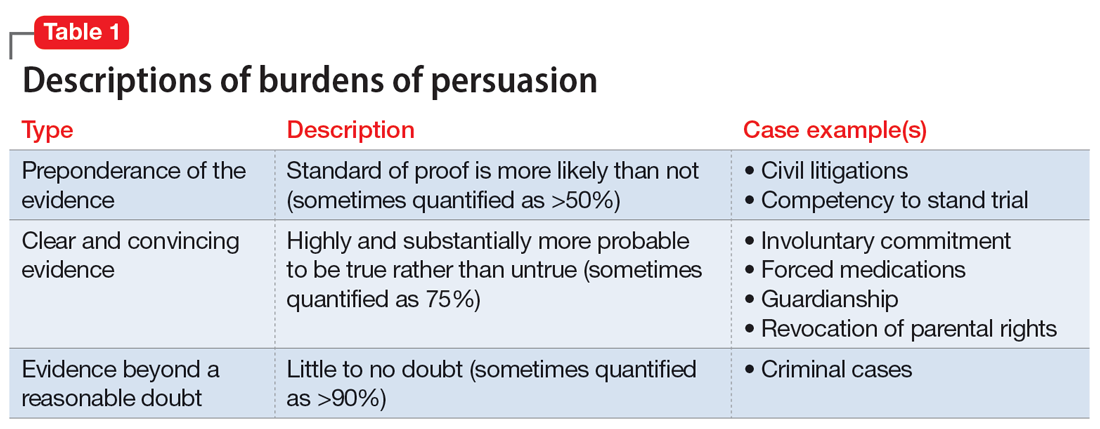

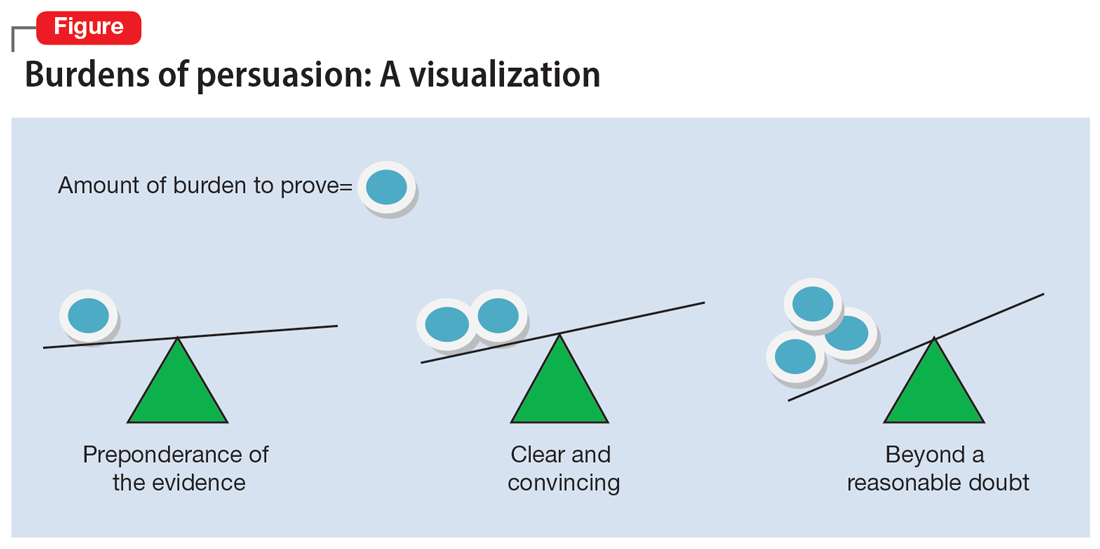

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

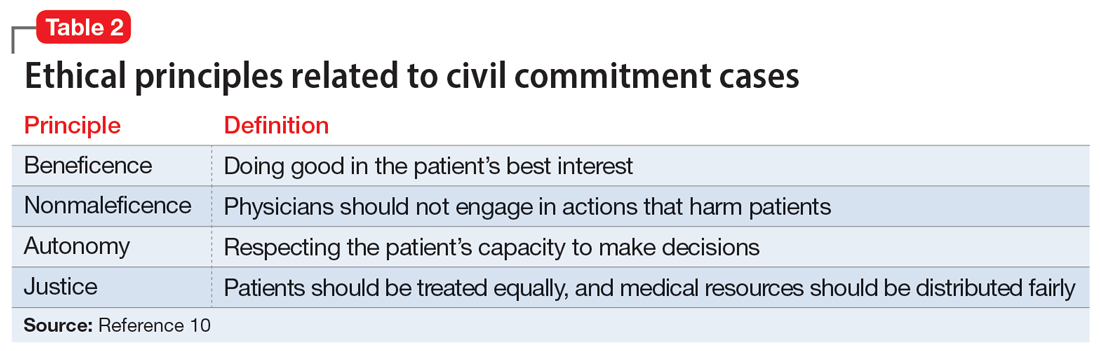

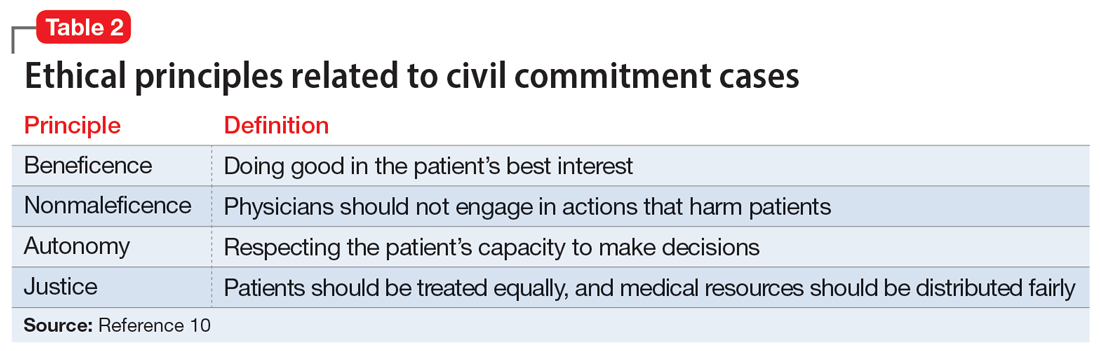

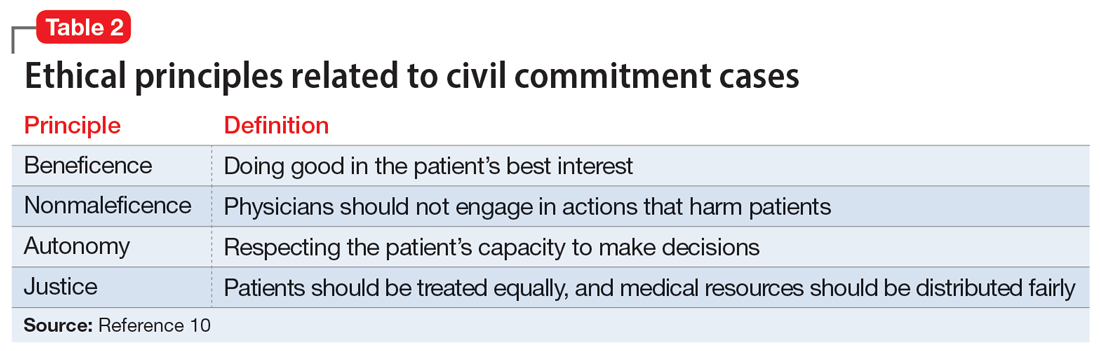

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

COVID-19’s religious strain: Differentiating spirituality from pathology