User login

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Caused by Pantoprazole

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

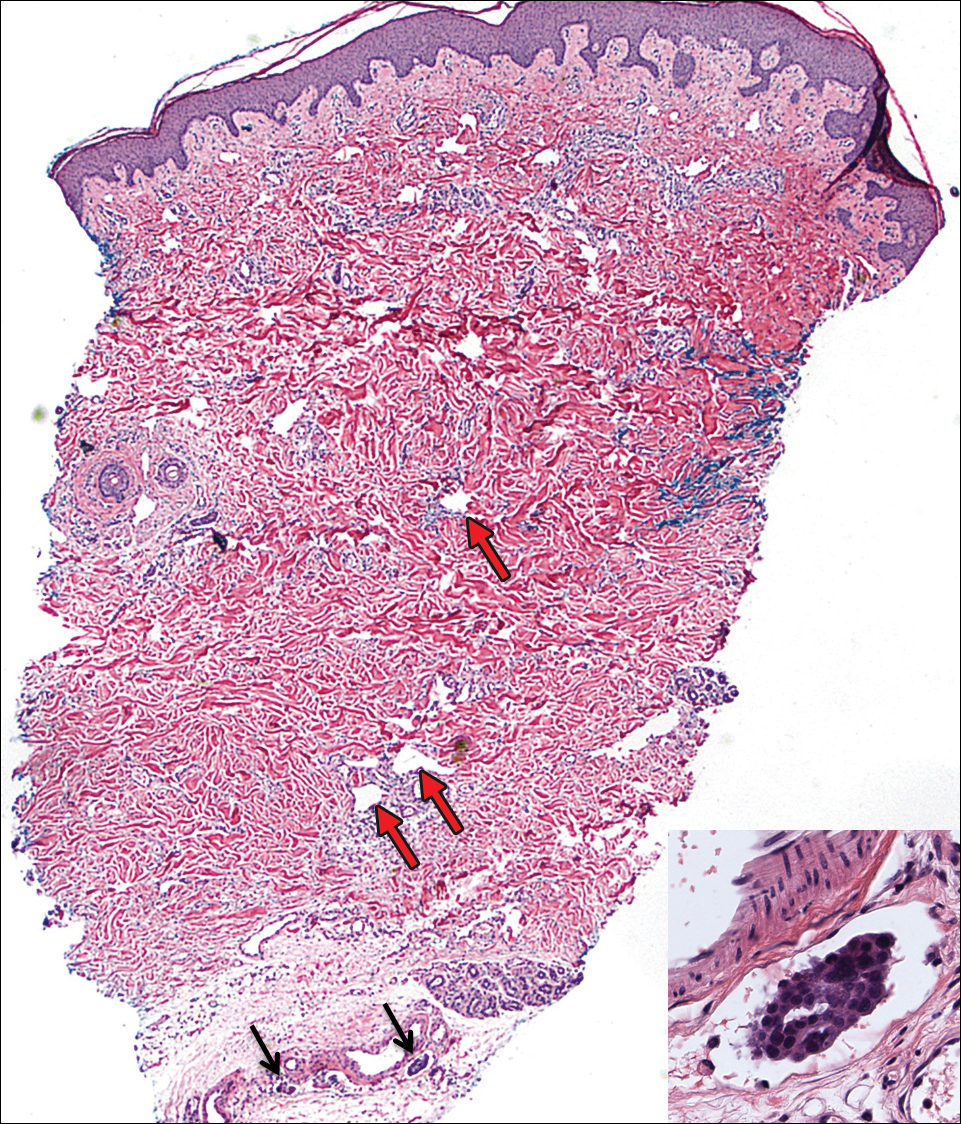

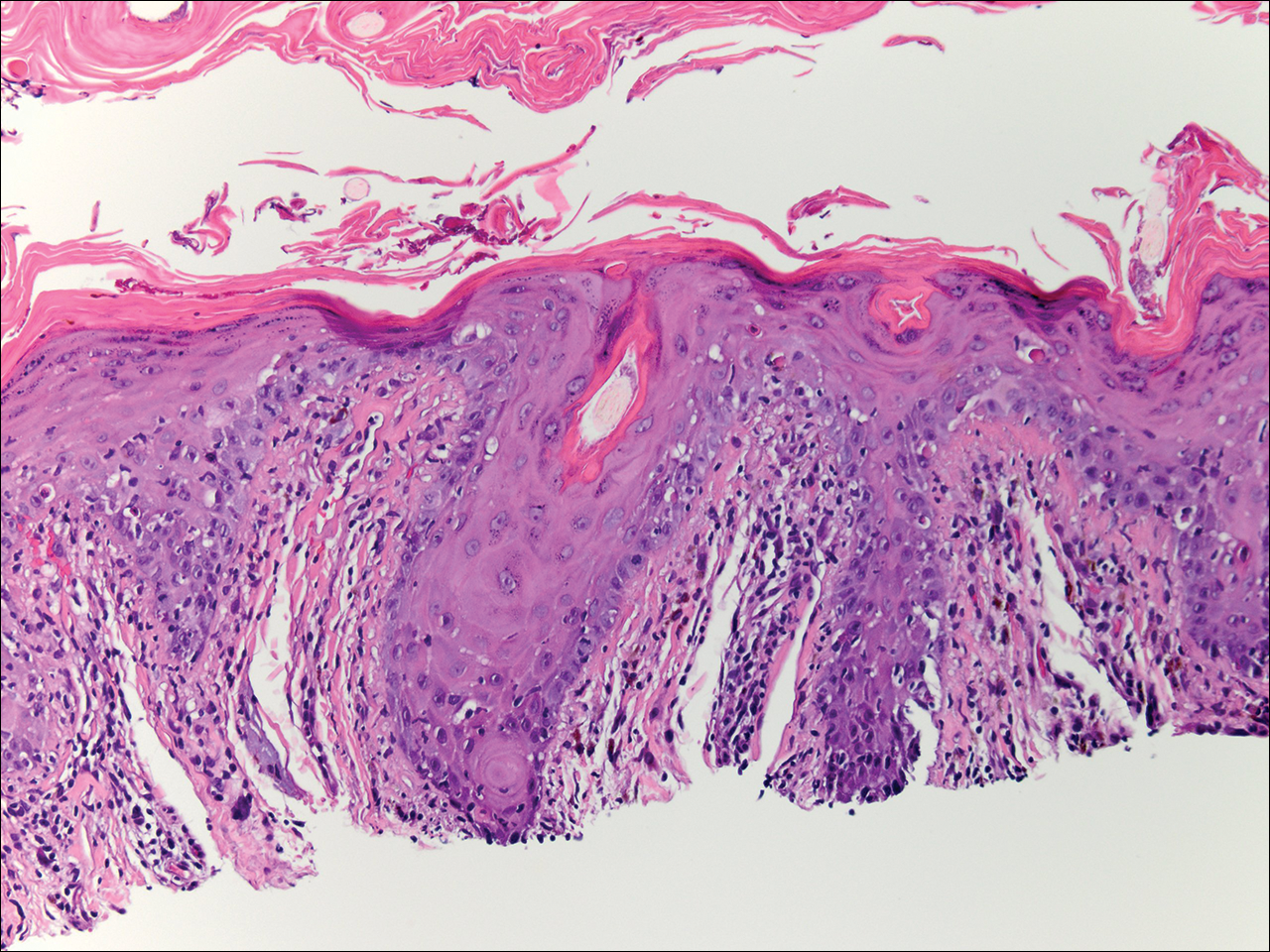

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis and Palisaded Neutrophilic Granulomatous Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

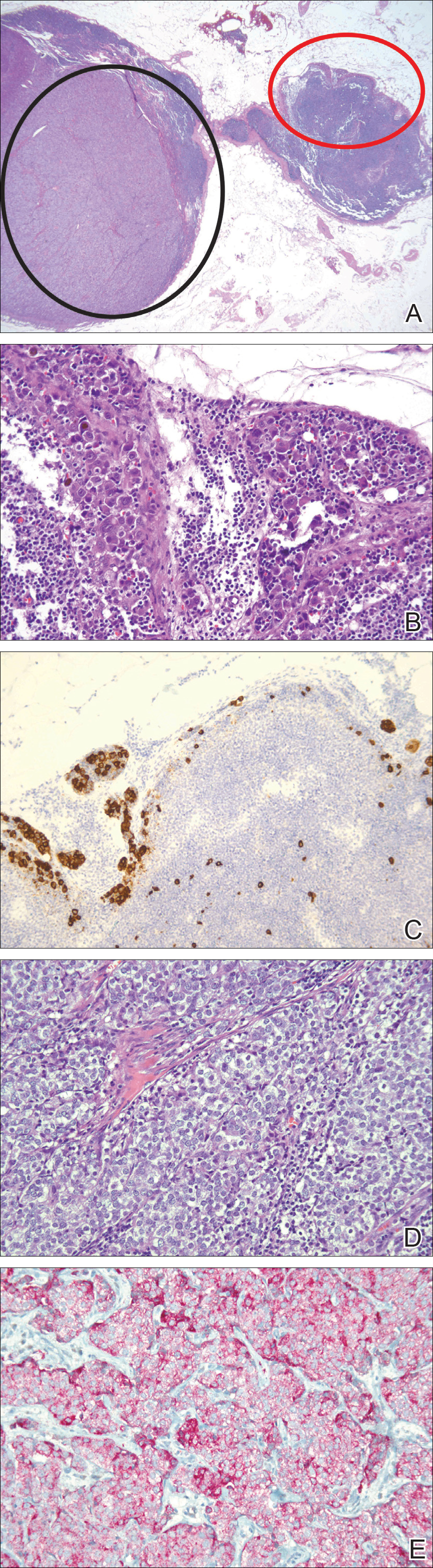

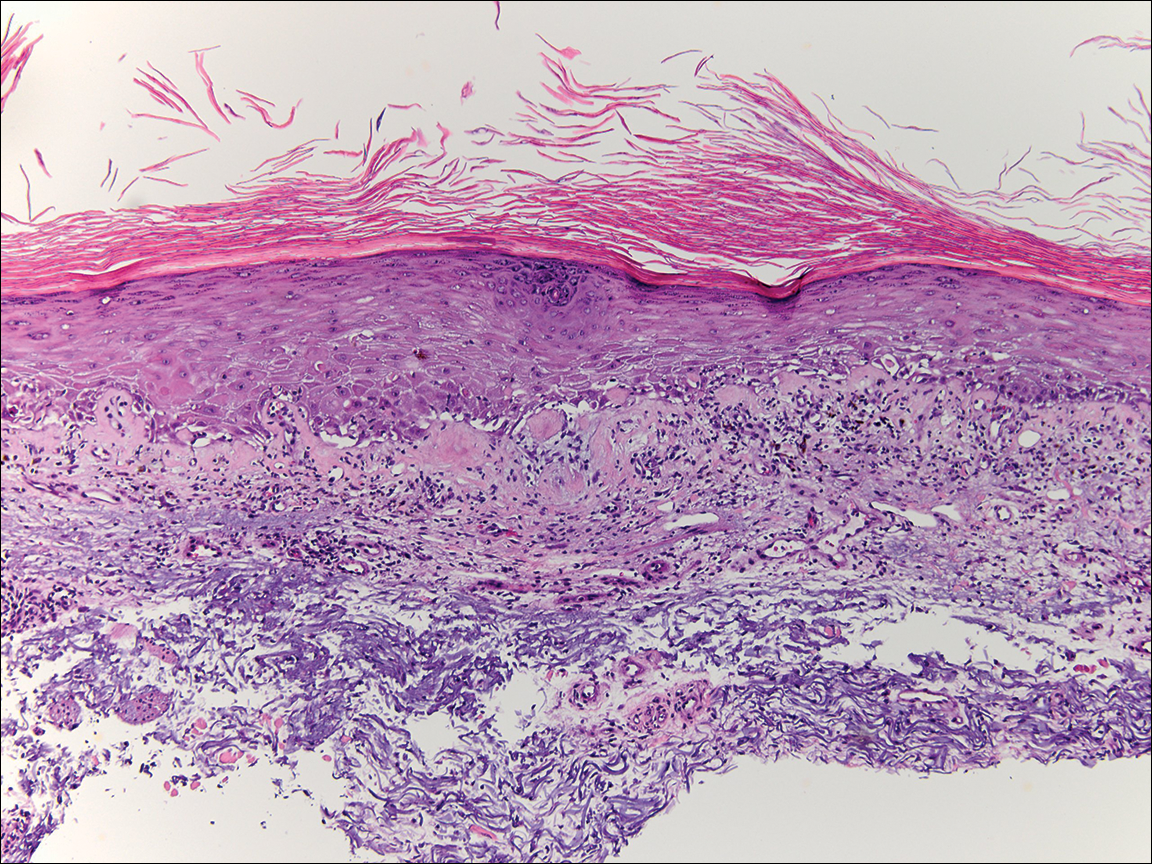

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

- Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to diagnosis in dermatopathology. Am Society Clin Pathol. 1993;3:309-312.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Hantash BM, Chiang D, Kohler S, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis associated with limited systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:661-664.

- Garcia-Rabasco A, Esteve-Martinez A, Zaragoza-Ninet V, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in a patient with lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:871-872.

- Gulati A, Paige D, Yaqoob M, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with the burning rope sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:711-714.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Fett N, Kovarik C, Bennett D. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis without a definable underlying disorder treated with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E92-E93.

- Verneuil L, Dompmartin A, Comoz F, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with cutaneous cords and arthritis: a disorder associated with autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:286-291.

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

- Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to diagnosis in dermatopathology. Am Society Clin Pathol. 1993;3:309-312.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Hantash BM, Chiang D, Kohler S, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis associated with limited systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:661-664.

- Garcia-Rabasco A, Esteve-Martinez A, Zaragoza-Ninet V, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in a patient with lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:871-872.

- Gulati A, Paige D, Yaqoob M, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with the burning rope sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:711-714.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Fett N, Kovarik C, Bennett D. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis without a definable underlying disorder treated with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E92-E93.

- Verneuil L, Dompmartin A, Comoz F, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with cutaneous cords and arthritis: a disorder associated with autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:286-291.

- Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to diagnosis in dermatopathology. Am Society Clin Pathol. 1993;3:309-312.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Hantash BM, Chiang D, Kohler S, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis associated with limited systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:661-664.

- Garcia-Rabasco A, Esteve-Martinez A, Zaragoza-Ninet V, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in a patient with lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:871-872.

- Gulati A, Paige D, Yaqoob M, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with the burning rope sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:711-714.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Fett N, Kovarik C, Bennett D. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis without a definable underlying disorder treated with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E92-E93.

- Verneuil L, Dompmartin A, Comoz F, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with cutaneous cords and arthritis: a disorder associated with autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:286-291.

Practice Points

- The clinical features of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis exist on a spectrum, and these is considerable overlap between the features of these 2 clinicopathologic entities.

- Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis may respond to systemic steroids or treatment of the underlying systemic disease. Some cases spontaneously resolve.

Tinea Incognito in a Tattoo

To the Editor:

Tinea incognito occurs when superficial fungal infections fail to demonstrate typical clinical features in the setting of immune suppression caused by topical or systemic steroids.1,2 A case of tinea corporis obscured by an allergic tattoo reaction is presented.

A 52-year-old man presented for evaluation of a rash overlying a tattoo on the right calf of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure, A). The tattoo was placed 4 years prior to presentation. Within 6 months of the tattoo’s placement, pruritus, scaling, and edema developed in a 2-mm rim around the outer border and in the eyes of the elephant tattoo but not in the lettering portion of the tattoo, which was added by a different tattoo artist with a different red dye. A diagnosis of red dye tattoo allergic reaction was made. Daily treatment with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% and halobetasol propionate cream 0.05% under occlusion for 18 months provided only partial relief of incessant pruritus. Three months prior to presentation the tattoo reaction appeared to become worse with more pruritus and extension outside the bounds of the original tattoo.

Physical examination revealed the red rim of the tattoo was erythematous, edematous, and crusted. In addition, a 5×4-cm well-demarcated, erythematous, scaling patch was present overlying the elephant tattoo on the right calf and extending superiorly and laterally away from the tattoo. Scaling and maceration also were present in the web spaces between the fourth and fifth toes, and the toenails were yellowed, thickened, and dystrophic with signs of distal onycholysis. A potassium hydroxide preparation performed from the plaque on the right calf demonstrated septate fungal hyphae.

The diagnosis of tinea corporis secondary to tinea pedis overlying a red dye tattoo allergic reaction was made. Tacrolimus and halobetasol propionate were discontinued and treatment with ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily and oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily was started. The erythematous patch beyond the borders of the tattoo cleared within weeks, but the patient reported worsening of cracking, itching, and swelling overlying the red dye in the rim of the tattoo following discontinuation of topical anti-inflammatory drugs (Figure, B).

A potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrated that the expansible rash was tinea corporis disguised in its character by the coloration of the tattoo; the erythematous, edematous, pruritic tattoo allergic reaction at its rim; and suppression of the normal inflammatory response by daily use of a topical steroid and a calcineurin inhibitor. The latter effect (an immunocompromised district) impacts the classic exaggerated scaling, inflamed rim, and central clearing of tinea corporis present in individuals with a normal inflammatory response.2 Although tinea incognito is classically described on the ankles and lower legs of patients with stasis dermatitis chronically treated with topical steroids, it could occur anywhere in the setting of immunosuppression.3

An analysis of this case using Occam’s razor suggests that the association of this tattoo and tinea was not a coincidence. This guiding principle (heuristic) suggests that economy and succinctness in the logic of science is most likely to produce a correct medical diagnosis (eg, associated findings can be explained by identifying one underlying cause).4 The topical anti-inflammatory drugs increase the likelihood that the patient’s interdigital tinea would spread to this precise location symmetrically expanding in the outline of the tattoo.2

- Gathings RM, Abide JM, Brodell RT. An unusual inflammatory rash. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:185-186.

- Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV, et al. The immunocompromised district: a unifying concept for lymphoedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1364-1373.

- Romano C, Maritati E, Gianni C. Tinea incognito in Italy: a 15-year survey. Mycoses. 2006;49:383-387.

- Jefferys WH, Berger JO. Ockham’s razor and Bayesian analysis. American Scientist. 1992;80:64-72.

To the Editor:

Tinea incognito occurs when superficial fungal infections fail to demonstrate typical clinical features in the setting of immune suppression caused by topical or systemic steroids.1,2 A case of tinea corporis obscured by an allergic tattoo reaction is presented.

A 52-year-old man presented for evaluation of a rash overlying a tattoo on the right calf of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure, A). The tattoo was placed 4 years prior to presentation. Within 6 months of the tattoo’s placement, pruritus, scaling, and edema developed in a 2-mm rim around the outer border and in the eyes of the elephant tattoo but not in the lettering portion of the tattoo, which was added by a different tattoo artist with a different red dye. A diagnosis of red dye tattoo allergic reaction was made. Daily treatment with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% and halobetasol propionate cream 0.05% under occlusion for 18 months provided only partial relief of incessant pruritus. Three months prior to presentation the tattoo reaction appeared to become worse with more pruritus and extension outside the bounds of the original tattoo.

Physical examination revealed the red rim of the tattoo was erythematous, edematous, and crusted. In addition, a 5×4-cm well-demarcated, erythematous, scaling patch was present overlying the elephant tattoo on the right calf and extending superiorly and laterally away from the tattoo. Scaling and maceration also were present in the web spaces between the fourth and fifth toes, and the toenails were yellowed, thickened, and dystrophic with signs of distal onycholysis. A potassium hydroxide preparation performed from the plaque on the right calf demonstrated septate fungal hyphae.

The diagnosis of tinea corporis secondary to tinea pedis overlying a red dye tattoo allergic reaction was made. Tacrolimus and halobetasol propionate were discontinued and treatment with ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily and oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily was started. The erythematous patch beyond the borders of the tattoo cleared within weeks, but the patient reported worsening of cracking, itching, and swelling overlying the red dye in the rim of the tattoo following discontinuation of topical anti-inflammatory drugs (Figure, B).

A potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrated that the expansible rash was tinea corporis disguised in its character by the coloration of the tattoo; the erythematous, edematous, pruritic tattoo allergic reaction at its rim; and suppression of the normal inflammatory response by daily use of a topical steroid and a calcineurin inhibitor. The latter effect (an immunocompromised district) impacts the classic exaggerated scaling, inflamed rim, and central clearing of tinea corporis present in individuals with a normal inflammatory response.2 Although tinea incognito is classically described on the ankles and lower legs of patients with stasis dermatitis chronically treated with topical steroids, it could occur anywhere in the setting of immunosuppression.3

An analysis of this case using Occam’s razor suggests that the association of this tattoo and tinea was not a coincidence. This guiding principle (heuristic) suggests that economy and succinctness in the logic of science is most likely to produce a correct medical diagnosis (eg, associated findings can be explained by identifying one underlying cause).4 The topical anti-inflammatory drugs increase the likelihood that the patient’s interdigital tinea would spread to this precise location symmetrically expanding in the outline of the tattoo.2

To the Editor:

Tinea incognito occurs when superficial fungal infections fail to demonstrate typical clinical features in the setting of immune suppression caused by topical or systemic steroids.1,2 A case of tinea corporis obscured by an allergic tattoo reaction is presented.

A 52-year-old man presented for evaluation of a rash overlying a tattoo on the right calf of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure, A). The tattoo was placed 4 years prior to presentation. Within 6 months of the tattoo’s placement, pruritus, scaling, and edema developed in a 2-mm rim around the outer border and in the eyes of the elephant tattoo but not in the lettering portion of the tattoo, which was added by a different tattoo artist with a different red dye. A diagnosis of red dye tattoo allergic reaction was made. Daily treatment with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% and halobetasol propionate cream 0.05% under occlusion for 18 months provided only partial relief of incessant pruritus. Three months prior to presentation the tattoo reaction appeared to become worse with more pruritus and extension outside the bounds of the original tattoo.

Physical examination revealed the red rim of the tattoo was erythematous, edematous, and crusted. In addition, a 5×4-cm well-demarcated, erythematous, scaling patch was present overlying the elephant tattoo on the right calf and extending superiorly and laterally away from the tattoo. Scaling and maceration also were present in the web spaces between the fourth and fifth toes, and the toenails were yellowed, thickened, and dystrophic with signs of distal onycholysis. A potassium hydroxide preparation performed from the plaque on the right calf demonstrated septate fungal hyphae.

The diagnosis of tinea corporis secondary to tinea pedis overlying a red dye tattoo allergic reaction was made. Tacrolimus and halobetasol propionate were discontinued and treatment with ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily and oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily was started. The erythematous patch beyond the borders of the tattoo cleared within weeks, but the patient reported worsening of cracking, itching, and swelling overlying the red dye in the rim of the tattoo following discontinuation of topical anti-inflammatory drugs (Figure, B).

A potassium hydroxide preparation demonstrated that the expansible rash was tinea corporis disguised in its character by the coloration of the tattoo; the erythematous, edematous, pruritic tattoo allergic reaction at its rim; and suppression of the normal inflammatory response by daily use of a topical steroid and a calcineurin inhibitor. The latter effect (an immunocompromised district) impacts the classic exaggerated scaling, inflamed rim, and central clearing of tinea corporis present in individuals with a normal inflammatory response.2 Although tinea incognito is classically described on the ankles and lower legs of patients with stasis dermatitis chronically treated with topical steroids, it could occur anywhere in the setting of immunosuppression.3

An analysis of this case using Occam’s razor suggests that the association of this tattoo and tinea was not a coincidence. This guiding principle (heuristic) suggests that economy and succinctness in the logic of science is most likely to produce a correct medical diagnosis (eg, associated findings can be explained by identifying one underlying cause).4 The topical anti-inflammatory drugs increase the likelihood that the patient’s interdigital tinea would spread to this precise location symmetrically expanding in the outline of the tattoo.2

- Gathings RM, Abide JM, Brodell RT. An unusual inflammatory rash. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:185-186.

- Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV, et al. The immunocompromised district: a unifying concept for lymphoedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1364-1373.

- Romano C, Maritati E, Gianni C. Tinea incognito in Italy: a 15-year survey. Mycoses. 2006;49:383-387.

- Jefferys WH, Berger JO. Ockham’s razor and Bayesian analysis. American Scientist. 1992;80:64-72.

- Gathings RM, Abide JM, Brodell RT. An unusual inflammatory rash. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:185-186.

- Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV, et al. The immunocompromised district: a unifying concept for lymphoedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1364-1373.

- Romano C, Maritati E, Gianni C. Tinea incognito in Italy: a 15-year survey. Mycoses. 2006;49:383-387.

- Jefferys WH, Berger JO. Ockham’s razor and Bayesian analysis. American Scientist. 1992;80:64-72.

Practice Points

- Health care providers should have a low threshold to perform a potassium hydroxide preparation when the possibility of a superficial fungal infection is considered.

- Tinea incognito occurs when a superficial fungal infection has unusual clinical features in the setting of local immune suppression.

Secondary Syphilis: An Atypical Presentation Complicated by a False Negative Rapid Plasma Reagin Test

To the Editor:

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of syphilis cases in the United States decreased 95% from 1945 to 2000.1 Since 2000, the number of cases of syphilis in the United States has increased from 2.1 cases per 100,000 to 8.7 cases per 100,000.1 We report the case of an atypical presentation of secondary syphilis with a false negative rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, which resulted in delayed diagnosis and treatment. The goal of this report is to raise awareness of the increasing prevalence of syphilis in the United States, draw attention to atypical presentations of syphilis, and inform physicians of some of the pitfalls in current syphilis screening and testing modalities.

A 37-year-old man presented with cutaneous ulcers on the forehead, thighs, and forearms of 3 months’ duration. The lesions started as a scarlet fever–like rash consisting of diffuse boils that would burst and become ulcerated. He reported arthralgias and drenching night sweats and had unintentionally lost 20 pounds over the last 3 months. He also had pharyngitis 8 months prior to presentation and sinusitis 4 months prior to presentation. These symptoms were present during his initial evaluation. One month prior to the current presentation, a nurse practitioner from an outside clinic had prescribed sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and ordered an RPR test, which was nonreactive. The lesions did not resolve, and the patient was referred to our dermatology department.

On physical examination, multiple 1- to 3-cm erythematous, well-defined papules were noted on the thighs and forearms. Some of the papules were covered with crusts, some were ulcerated with yellow discharge, and all were nontender. The differential diagnoses included dermatomyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, deep fungal infection, mycobacterial infection, leishmaniasis, and cutaneous anthrax. Secondary syphilis was a possible differential but was discounted due to the nonreactive RPR 1 month prior to presentation.

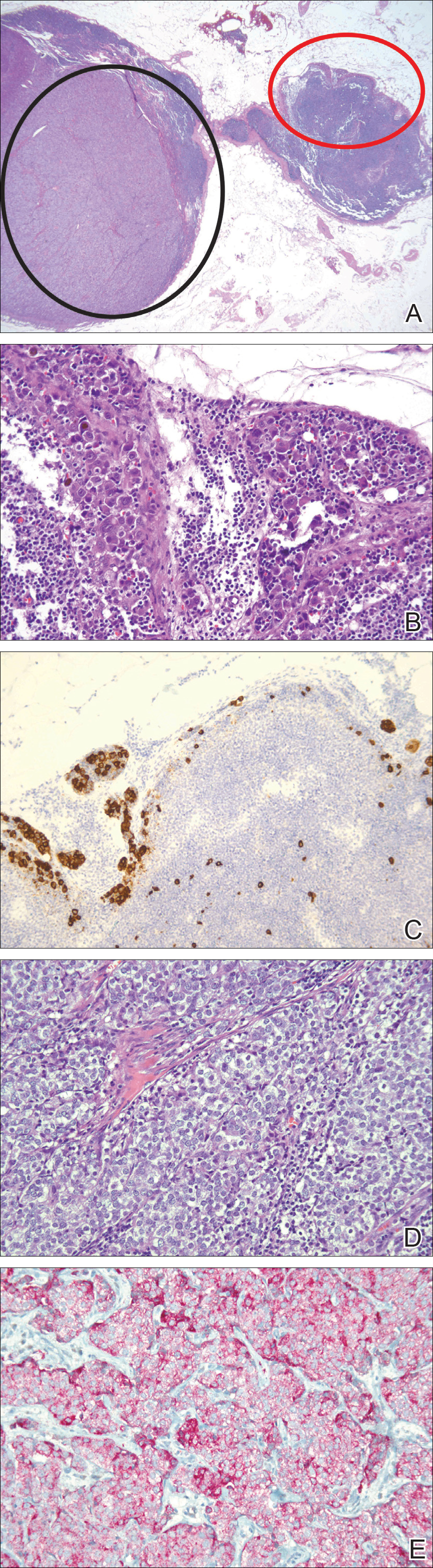

Punch biopsies were collected from lesions on the forehead, forearms, and thighs and sent to multiple institutions for pathology evaluation, which revealed dermal and pannicular necrosis and acute suppurative and granulomatous inflammation focally involving vessels (Figure 1). The biopsies were negative for acid-fast and fungal organisms, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Leishmania, and anthrax. A work-up for Wegener granulomatosis was recommended by the pathology department.

Three days later, the patient was admitted to the hospital for syncope. The hospitalist noted the cutaneous lesions and reordered the RPR test, which was now reactive. The ulcers had worsened since the original presentation (Figure 2). A fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test confirmed the reactive RPR, and a diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. He was allergic to penicillin G, so the patient was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 28 days. His cutaneous ulcers have since healed with no recurrence of symptoms.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by a prodrome of fever, malaise, sore throat, adenopathy, unintentional weight loss, myalgias, and headaches. It usually presents as a nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption with painless mucosal ulcers but rarely presents as cutaneous ulcers.2-4 Cutaneous ulcers are typical of lues maligna, which usually occurs in immunosuppressed patients.5,6 Our patient was human immunodeficiency virus–negative and was not otherwise immunocompromised.

Rapid plasma reagin is a common screening test for syphilis. In this case, it was initially negative, which may be attributed to the prozone phenomenon, a false negative result due to a high antibody titer that prevents the flocculation reaction from occurring. The prozone phenomenon can occur with a titer as low as 1:8.7 A 50% dilution of the negative sample should overcome the prozone phenomenon and yield a positive result7; unfortunately, this is not standard practice in all hospital laboratories.

The standard method of diagnosing syphilis in the United States is to screen with nontreponemal tests (eg, RPR) followed by treponemal tests (eg, FTA-ABS) to confirm a positive screen. According to the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the sensitivity of the RPR test is approximately 78% to 86%, while FTA-ABS has a sensitivity of 84% for detecting primary syphilis and 100% for secondary and tertiary syphilis.8 Seña et al4 suggest that FTA-ABS should be used as the screening test for syphilis. Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing more accurately detects syphilis, while RPR testing is more useful in monitoring serum response once treatment has been initiated.

In conclusion, our patient could have benefited from earlier diagnosis and treatment if a treponemal test had been performed earlier or if the initial nonreactive RPR test was diluted and retested.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Timothy Weiland (Pathology Department, Altru Health System, Grand Forks, North Dakota), and Dr. Mark Koponen (University of North Dakota, Grand Forks).

- Syphilis—CDC fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Stary A, Stary G. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1368-1426.

- Habif TP. Sexually transmitted bacterial infections. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. China: Elsevier; 2016:377-417.

- Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

- Bayramgürler D, Bilen N, Yıldız K, et al. Lues maligna in a chronic alcoholic patient. J Dermatol. 2005;32:217-219.

- Bhate C, Tajirian AL, Kapila R, et al. Secondary syphilis resembling erythema multiforme. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1321-1324.

- Liu LL, Lin LR, Tong ML, et al. Incidence and risk factors for the prozone phenomenon in serologic testing for syphilis in a large cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:384-389.

- Archived final recommendation statement. syphilis infection: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force website. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/syphilis-infection-screening. Published December 30, 2013. Accessed May 22, 2018.

To the Editor:

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of syphilis cases in the United States decreased 95% from 1945 to 2000.1 Since 2000, the number of cases of syphilis in the United States has increased from 2.1 cases per 100,000 to 8.7 cases per 100,000.1 We report the case of an atypical presentation of secondary syphilis with a false negative rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, which resulted in delayed diagnosis and treatment. The goal of this report is to raise awareness of the increasing prevalence of syphilis in the United States, draw attention to atypical presentations of syphilis, and inform physicians of some of the pitfalls in current syphilis screening and testing modalities.

A 37-year-old man presented with cutaneous ulcers on the forehead, thighs, and forearms of 3 months’ duration. The lesions started as a scarlet fever–like rash consisting of diffuse boils that would burst and become ulcerated. He reported arthralgias and drenching night sweats and had unintentionally lost 20 pounds over the last 3 months. He also had pharyngitis 8 months prior to presentation and sinusitis 4 months prior to presentation. These symptoms were present during his initial evaluation. One month prior to the current presentation, a nurse practitioner from an outside clinic had prescribed sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and ordered an RPR test, which was nonreactive. The lesions did not resolve, and the patient was referred to our dermatology department.

On physical examination, multiple 1- to 3-cm erythematous, well-defined papules were noted on the thighs and forearms. Some of the papules were covered with crusts, some were ulcerated with yellow discharge, and all were nontender. The differential diagnoses included dermatomyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, deep fungal infection, mycobacterial infection, leishmaniasis, and cutaneous anthrax. Secondary syphilis was a possible differential but was discounted due to the nonreactive RPR 1 month prior to presentation.

Punch biopsies were collected from lesions on the forehead, forearms, and thighs and sent to multiple institutions for pathology evaluation, which revealed dermal and pannicular necrosis and acute suppurative and granulomatous inflammation focally involving vessels (Figure 1). The biopsies were negative for acid-fast and fungal organisms, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Leishmania, and anthrax. A work-up for Wegener granulomatosis was recommended by the pathology department.

Three days later, the patient was admitted to the hospital for syncope. The hospitalist noted the cutaneous lesions and reordered the RPR test, which was now reactive. The ulcers had worsened since the original presentation (Figure 2). A fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test confirmed the reactive RPR, and a diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. He was allergic to penicillin G, so the patient was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 28 days. His cutaneous ulcers have since healed with no recurrence of symptoms.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by a prodrome of fever, malaise, sore throat, adenopathy, unintentional weight loss, myalgias, and headaches. It usually presents as a nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption with painless mucosal ulcers but rarely presents as cutaneous ulcers.2-4 Cutaneous ulcers are typical of lues maligna, which usually occurs in immunosuppressed patients.5,6 Our patient was human immunodeficiency virus–negative and was not otherwise immunocompromised.

Rapid plasma reagin is a common screening test for syphilis. In this case, it was initially negative, which may be attributed to the prozone phenomenon, a false negative result due to a high antibody titer that prevents the flocculation reaction from occurring. The prozone phenomenon can occur with a titer as low as 1:8.7 A 50% dilution of the negative sample should overcome the prozone phenomenon and yield a positive result7; unfortunately, this is not standard practice in all hospital laboratories.

The standard method of diagnosing syphilis in the United States is to screen with nontreponemal tests (eg, RPR) followed by treponemal tests (eg, FTA-ABS) to confirm a positive screen. According to the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the sensitivity of the RPR test is approximately 78% to 86%, while FTA-ABS has a sensitivity of 84% for detecting primary syphilis and 100% for secondary and tertiary syphilis.8 Seña et al4 suggest that FTA-ABS should be used as the screening test for syphilis. Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing more accurately detects syphilis, while RPR testing is more useful in monitoring serum response once treatment has been initiated.

In conclusion, our patient could have benefited from earlier diagnosis and treatment if a treponemal test had been performed earlier or if the initial nonreactive RPR test was diluted and retested.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Timothy Weiland (Pathology Department, Altru Health System, Grand Forks, North Dakota), and Dr. Mark Koponen (University of North Dakota, Grand Forks).

To the Editor:

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of syphilis cases in the United States decreased 95% from 1945 to 2000.1 Since 2000, the number of cases of syphilis in the United States has increased from 2.1 cases per 100,000 to 8.7 cases per 100,000.1 We report the case of an atypical presentation of secondary syphilis with a false negative rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, which resulted in delayed diagnosis and treatment. The goal of this report is to raise awareness of the increasing prevalence of syphilis in the United States, draw attention to atypical presentations of syphilis, and inform physicians of some of the pitfalls in current syphilis screening and testing modalities.

A 37-year-old man presented with cutaneous ulcers on the forehead, thighs, and forearms of 3 months’ duration. The lesions started as a scarlet fever–like rash consisting of diffuse boils that would burst and become ulcerated. He reported arthralgias and drenching night sweats and had unintentionally lost 20 pounds over the last 3 months. He also had pharyngitis 8 months prior to presentation and sinusitis 4 months prior to presentation. These symptoms were present during his initial evaluation. One month prior to the current presentation, a nurse practitioner from an outside clinic had prescribed sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and ordered an RPR test, which was nonreactive. The lesions did not resolve, and the patient was referred to our dermatology department.

On physical examination, multiple 1- to 3-cm erythematous, well-defined papules were noted on the thighs and forearms. Some of the papules were covered with crusts, some were ulcerated with yellow discharge, and all were nontender. The differential diagnoses included dermatomyositis, polyarteritis nodosa, deep fungal infection, mycobacterial infection, leishmaniasis, and cutaneous anthrax. Secondary syphilis was a possible differential but was discounted due to the nonreactive RPR 1 month prior to presentation.

Punch biopsies were collected from lesions on the forehead, forearms, and thighs and sent to multiple institutions for pathology evaluation, which revealed dermal and pannicular necrosis and acute suppurative and granulomatous inflammation focally involving vessels (Figure 1). The biopsies were negative for acid-fast and fungal organisms, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Leishmania, and anthrax. A work-up for Wegener granulomatosis was recommended by the pathology department.

Three days later, the patient was admitted to the hospital for syncope. The hospitalist noted the cutaneous lesions and reordered the RPR test, which was now reactive. The ulcers had worsened since the original presentation (Figure 2). A fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test confirmed the reactive RPR, and a diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. He was allergic to penicillin G, so the patient was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 28 days. His cutaneous ulcers have since healed with no recurrence of symptoms.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by a prodrome of fever, malaise, sore throat, adenopathy, unintentional weight loss, myalgias, and headaches. It usually presents as a nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption with painless mucosal ulcers but rarely presents as cutaneous ulcers.2-4 Cutaneous ulcers are typical of lues maligna, which usually occurs in immunosuppressed patients.5,6 Our patient was human immunodeficiency virus–negative and was not otherwise immunocompromised.

Rapid plasma reagin is a common screening test for syphilis. In this case, it was initially negative, which may be attributed to the prozone phenomenon, a false negative result due to a high antibody titer that prevents the flocculation reaction from occurring. The prozone phenomenon can occur with a titer as low as 1:8.7 A 50% dilution of the negative sample should overcome the prozone phenomenon and yield a positive result7; unfortunately, this is not standard practice in all hospital laboratories.

The standard method of diagnosing syphilis in the United States is to screen with nontreponemal tests (eg, RPR) followed by treponemal tests (eg, FTA-ABS) to confirm a positive screen. According to the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the sensitivity of the RPR test is approximately 78% to 86%, while FTA-ABS has a sensitivity of 84% for detecting primary syphilis and 100% for secondary and tertiary syphilis.8 Seña et al4 suggest that FTA-ABS should be used as the screening test for syphilis. Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing more accurately detects syphilis, while RPR testing is more useful in monitoring serum response once treatment has been initiated.

In conclusion, our patient could have benefited from earlier diagnosis and treatment if a treponemal test had been performed earlier or if the initial nonreactive RPR test was diluted and retested.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Timothy Weiland (Pathology Department, Altru Health System, Grand Forks, North Dakota), and Dr. Mark Koponen (University of North Dakota, Grand Forks).

- Syphilis—CDC fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Stary A, Stary G. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1368-1426.

- Habif TP. Sexually transmitted bacterial infections. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. China: Elsevier; 2016:377-417.

- Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

- Bayramgürler D, Bilen N, Yıldız K, et al. Lues maligna in a chronic alcoholic patient. J Dermatol. 2005;32:217-219.

- Bhate C, Tajirian AL, Kapila R, et al. Secondary syphilis resembling erythema multiforme. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1321-1324.

- Liu LL, Lin LR, Tong ML, et al. Incidence and risk factors for the prozone phenomenon in serologic testing for syphilis in a large cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:384-389.

- Archived final recommendation statement. syphilis infection: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force website. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/syphilis-infection-screening. Published December 30, 2013. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Syphilis—CDC fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Stary A, Stary G. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1368-1426.

- Habif TP. Sexually transmitted bacterial infections. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. China: Elsevier; 2016:377-417.

- Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

- Bayramgürler D, Bilen N, Yıldız K, et al. Lues maligna in a chronic alcoholic patient. J Dermatol. 2005;32:217-219.

- Bhate C, Tajirian AL, Kapila R, et al. Secondary syphilis resembling erythema multiforme. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1321-1324.

- Liu LL, Lin LR, Tong ML, et al. Incidence and risk factors for the prozone phenomenon in serologic testing for syphilis in a large cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:384-389.

- Archived final recommendation statement. syphilis infection: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force website. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/syphilis-infection-screening. Published December 30, 2013. Accessed May 22, 2018.

Practice Points

- Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing more accurately detects syphilis than rapid plasma reagin (RPR).

- Rapid plasma reagin testing is more useful in monitoring serum response once treatment has been initiated.

- If only RPR is being performed at your institution, ensure the laboratory is performing serial dilutions to negate the prozone phenomenon.

Solitary Angiokeratoma of the Vulva Mimicking Malignant Melanoma

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

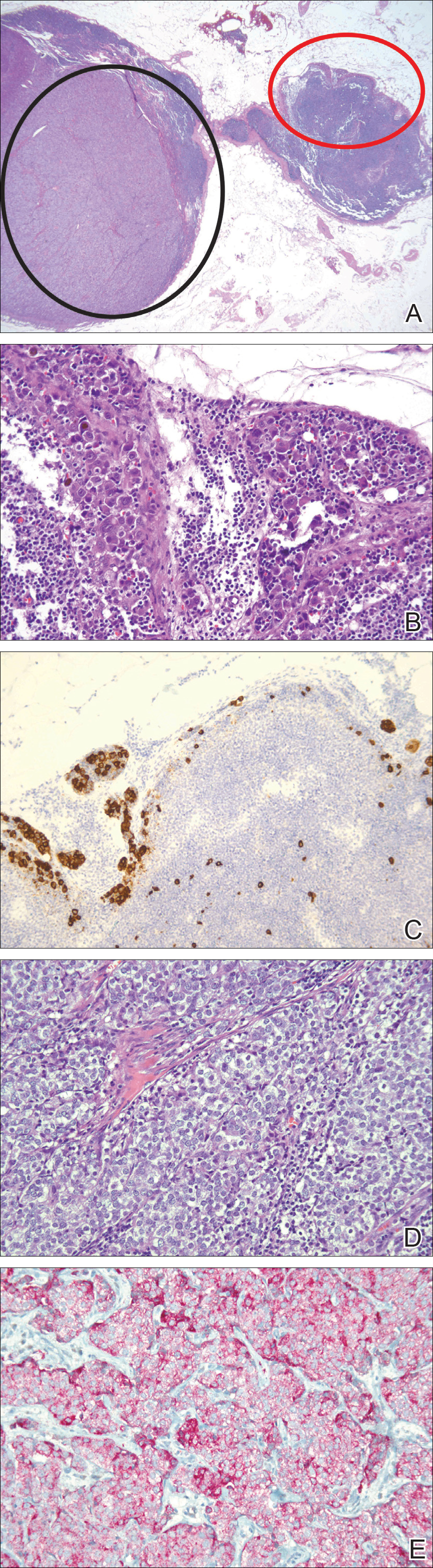

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).

Angiokeratoma, particularly the solitary type, often is misdiagnosed. Clinical differential diagnoses may include a wide range of pathologic conditions, including condyloma acuminata, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangioma, nevi, condyloma lata, nodular prurigo, seborrheic keratosis, granuloma inguinale, and deep fungal infection.2,5 However, due to its quickly growing nature and its dark complexion, malignant melanoma often is initially diagnosed. Because patients affected by angiokeratoma of the vulva usually are aged 20 to 40 years,5 and vulvar melanoma is typical for middle-aged women (median age, 68 years),6 this misdiagnosis is more likely in older patients. It should be noted that a high index of suspicion for melanoma often is present when examining the vulva, considering that this area is difficult to monitor, and there is an especially poor prognosis of vulvar melanoma due to its late detection.6,7

In the past, biopsy was considered mandatory for confirming the diagnosis of vulvar angiokeratoma.5,8,9 However, dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis of angiokeratoma10 and also was helpful as a diagnostic aid in one of our patients (patient 1). Therefore, we believe that dermoscopy should be performed prior to a biopsy of angiokeratomas of the vulva.

- Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. part I. hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

- Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

- Gomi H, Eriyama Y, Horikawa E, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma. J Dermatol. 1988;15:349-350.

- Yamazaki M, Hiruma M, Irie H, et al. Angiokeratoma of the clitoris: a subtype of angiokeratoma vulvae. J Dermatol. 1992;19:553-555.

- Cohen PR, Young AW Jr, Tovell HM. Angiokeratoma of the vulva: diagnosis and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:339-346.

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:296-301.

- De Simone P, Silipo V, Buccini P, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:127-133.

- Novick NL. Angiokeratoma vulvae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:561-563.

- Yigiter M, Arda IS, Tosun E, et al. Angiokeratoma of clitoris: a rare lesion in an adolescent girl. Urology. 2008;71:604-606.

- Zaballos P, Daufi C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).

Angiokeratoma, particularly the solitary type, often is misdiagnosed. Clinical differential diagnoses may include a wide range of pathologic conditions, including condyloma acuminata, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangioma, nevi, condyloma lata, nodular prurigo, seborrheic keratosis, granuloma inguinale, and deep fungal infection.2,5 However, due to its quickly growing nature and its dark complexion, malignant melanoma often is initially diagnosed. Because patients affected by angiokeratoma of the vulva usually are aged 20 to 40 years,5 and vulvar melanoma is typical for middle-aged women (median age, 68 years),6 this misdiagnosis is more likely in older patients. It should be noted that a high index of suspicion for melanoma often is present when examining the vulva, considering that this area is difficult to monitor, and there is an especially poor prognosis of vulvar melanoma due to its late detection.6,7

In the past, biopsy was considered mandatory for confirming the diagnosis of vulvar angiokeratoma.5,8,9 However, dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis of angiokeratoma10 and also was helpful as a diagnostic aid in one of our patients (patient 1). Therefore, we believe that dermoscopy should be performed prior to a biopsy of angiokeratomas of the vulva.

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).