User login

New fellowship, no problem

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Embedding diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice in hospital medicine

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

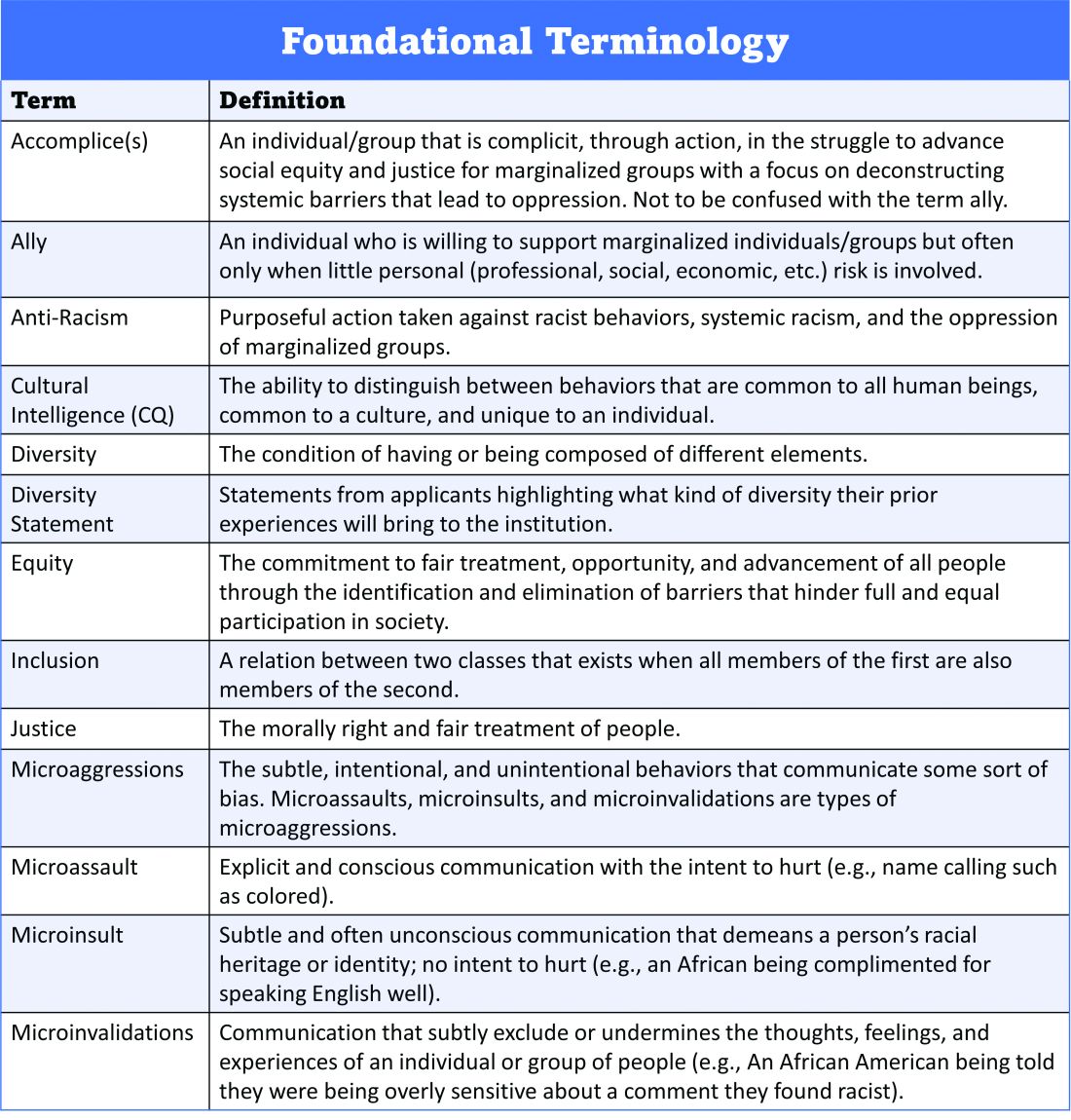

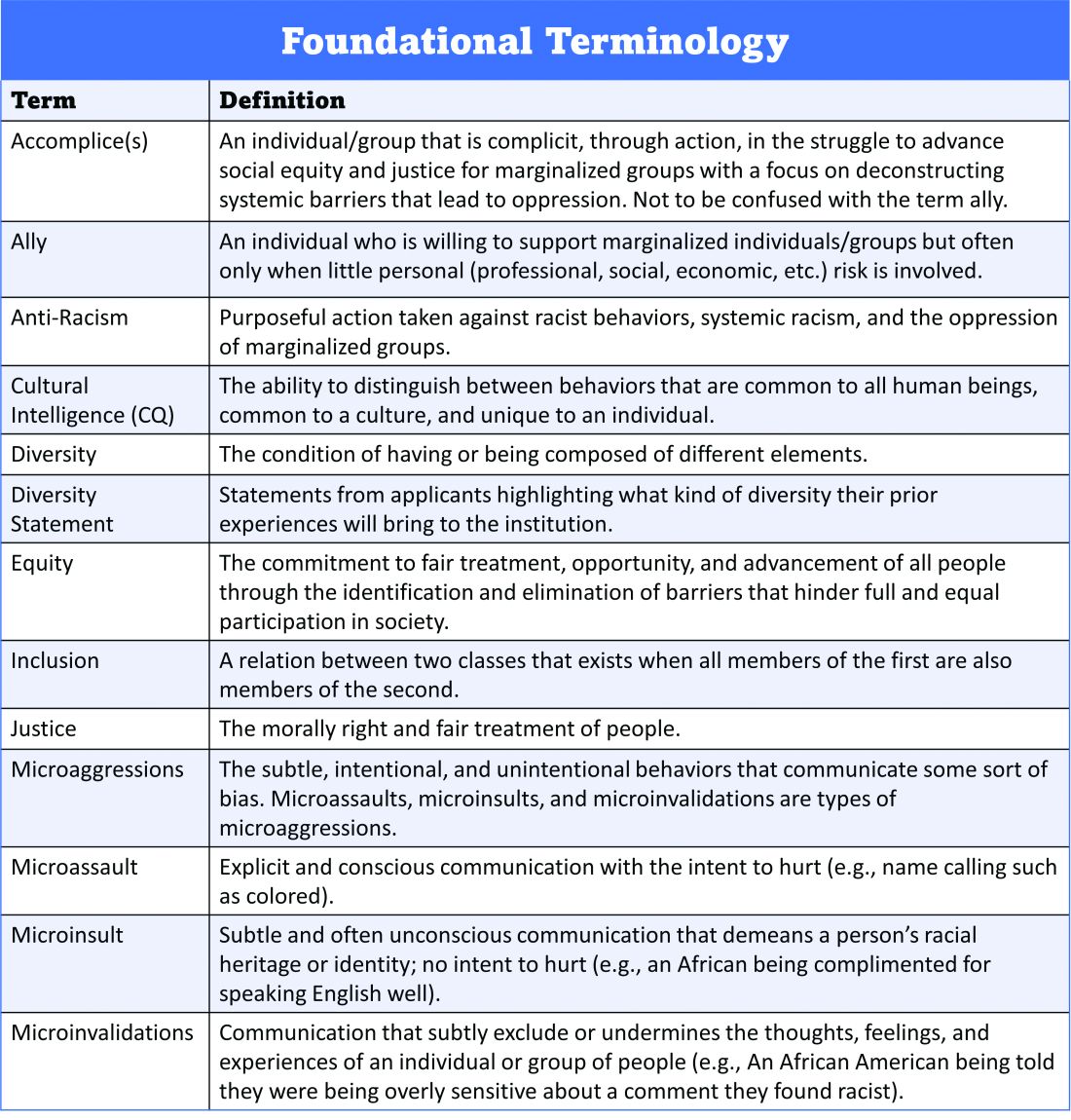

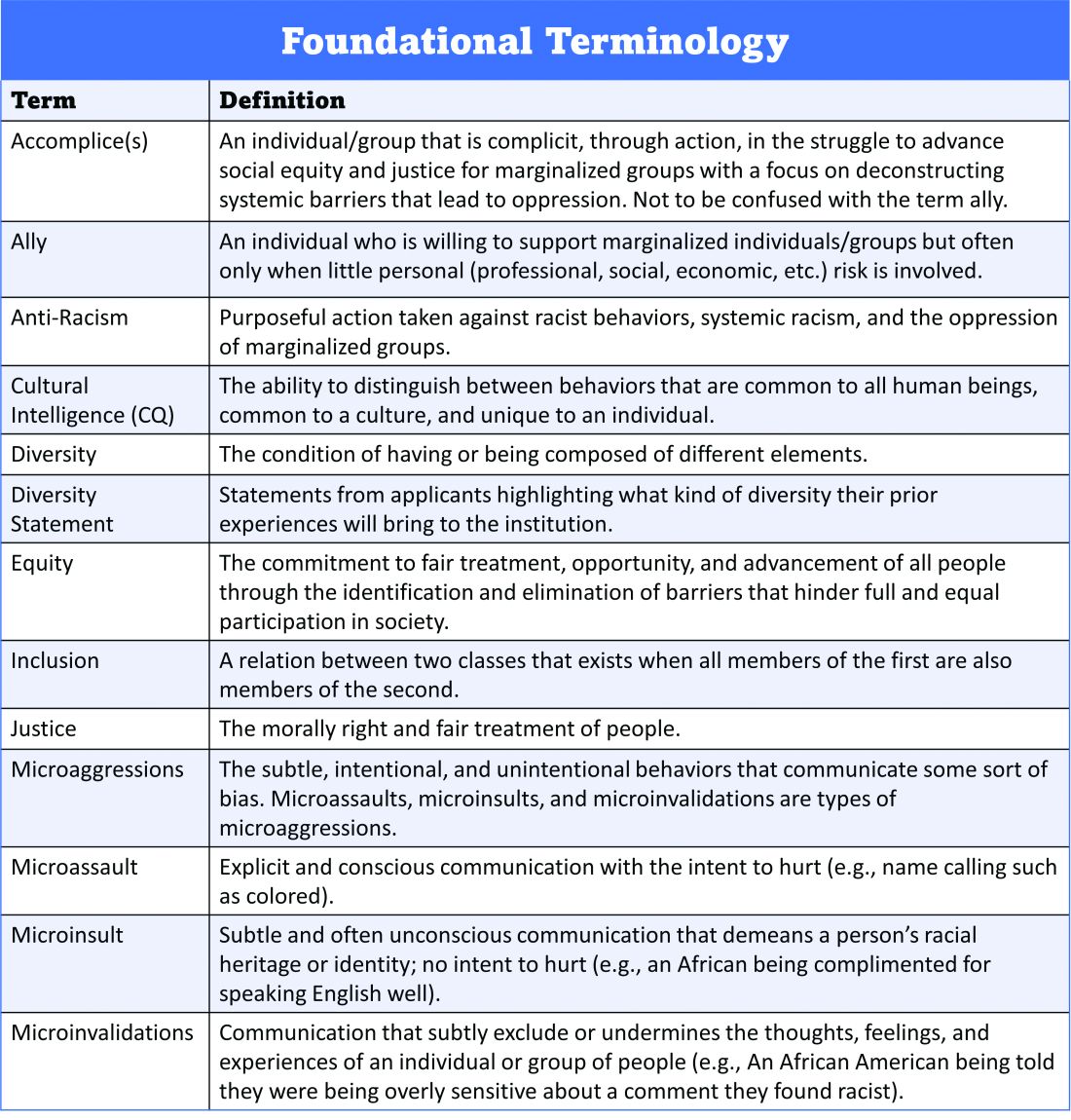

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

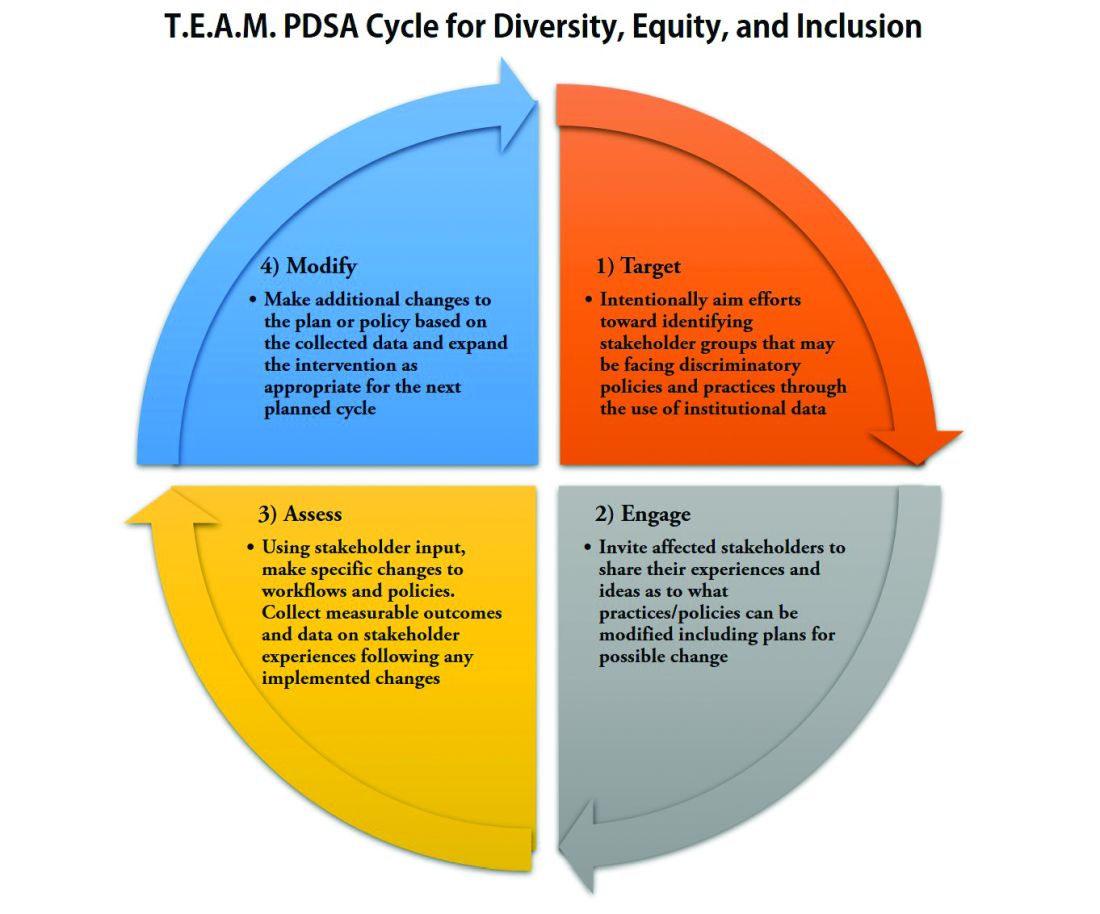

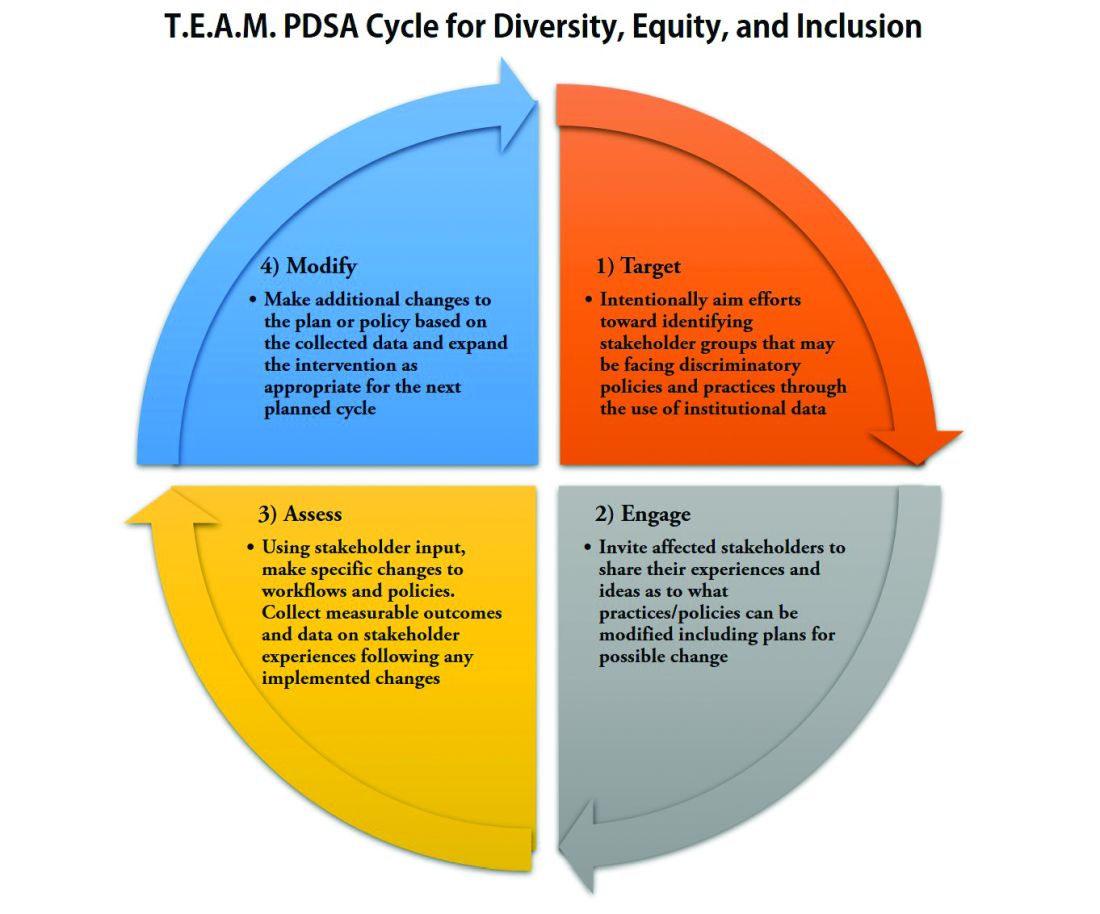

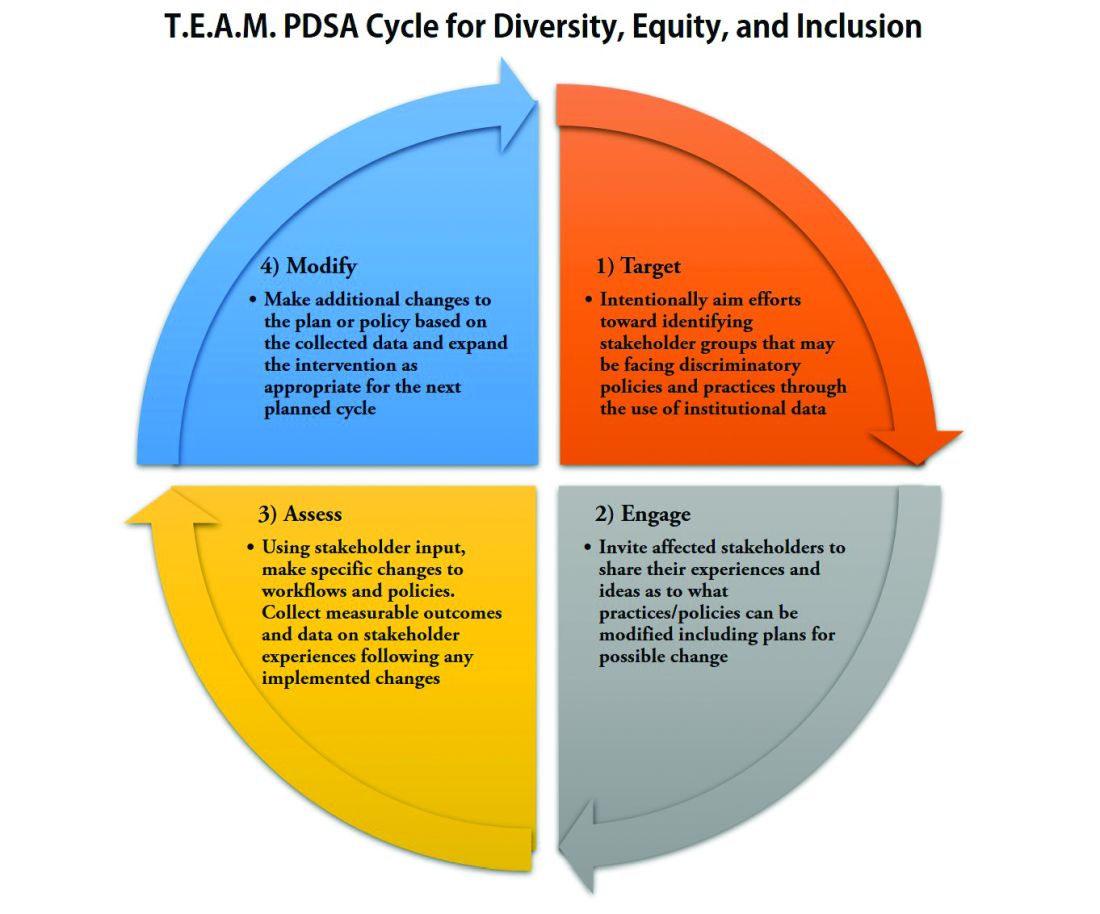

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

A road map for success

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

Navigating parenthood as pediatricians

PHM 2021 session

The Baby at Work or the Baby at Home: Navigating Parenthood as Pediatricians

Presenters

Jessica Gold, MD; Dana Foradori, MD, MEd; Nivedita Srinivas, MD; Honora Burnett, MD; Julie Pantaleoni, MD; and Barrett Fromme, MD, MHPE

Session summary

A group of physician-mothers from multiple academic children’s hospitals came together in a storytelling format to discuss topics relating to being a parent and pediatric hospitalist. Through short and poignant stories, the presenters shared their experiences and reviewed recent literature and policy changes relating to the topic. This mini-plenary focused on three themes:

1. Easing the transition back to work after the birth of a child.

2. Coping with the tension between being a parent and pediatrician.

3. The role that divisions, departments, and institutions can play in supporting parents and promoting workplace engagement.

The session concluded with a robust question-and-answer portion where participants built upon the themes above and shared their own experiences as pediatric hospitalist parents.

Key takeaways

- “Use your voice.” Physicians who are parents must continue having conversations about the challenging aspects of being a parent and hospitalist and advocate for the changes they would like to see.

- There will always be tension as a physician parent, but we can learn to embrace it while also learning how to ask for help, set boundaries, and share when we are struggling.

- There are numerous challenges for hospitalists who are parents because of poor parental leave policies in the United States, but this is slowly changing. For example, starting in July 2021, the ACGME mandated 6 weeks of parental leave during training without having to extend training.

- “You are not alone.” The presenters emphasized that their reason for hosting this session was to shed light on this topic and let all pediatric hospitalist parents know that they are not alone in this experience.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

PHM 2021 session

The Baby at Work or the Baby at Home: Navigating Parenthood as Pediatricians

Presenters

Jessica Gold, MD; Dana Foradori, MD, MEd; Nivedita Srinivas, MD; Honora Burnett, MD; Julie Pantaleoni, MD; and Barrett Fromme, MD, MHPE

Session summary

A group of physician-mothers from multiple academic children’s hospitals came together in a storytelling format to discuss topics relating to being a parent and pediatric hospitalist. Through short and poignant stories, the presenters shared their experiences and reviewed recent literature and policy changes relating to the topic. This mini-plenary focused on three themes:

1. Easing the transition back to work after the birth of a child.

2. Coping with the tension between being a parent and pediatrician.

3. The role that divisions, departments, and institutions can play in supporting parents and promoting workplace engagement.

The session concluded with a robust question-and-answer portion where participants built upon the themes above and shared their own experiences as pediatric hospitalist parents.

Key takeaways

- “Use your voice.” Physicians who are parents must continue having conversations about the challenging aspects of being a parent and hospitalist and advocate for the changes they would like to see.

- There will always be tension as a physician parent, but we can learn to embrace it while also learning how to ask for help, set boundaries, and share when we are struggling.

- There are numerous challenges for hospitalists who are parents because of poor parental leave policies in the United States, but this is slowly changing. For example, starting in July 2021, the ACGME mandated 6 weeks of parental leave during training without having to extend training.

- “You are not alone.” The presenters emphasized that their reason for hosting this session was to shed light on this topic and let all pediatric hospitalist parents know that they are not alone in this experience.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

PHM 2021 session

The Baby at Work or the Baby at Home: Navigating Parenthood as Pediatricians

Presenters

Jessica Gold, MD; Dana Foradori, MD, MEd; Nivedita Srinivas, MD; Honora Burnett, MD; Julie Pantaleoni, MD; and Barrett Fromme, MD, MHPE

Session summary

A group of physician-mothers from multiple academic children’s hospitals came together in a storytelling format to discuss topics relating to being a parent and pediatric hospitalist. Through short and poignant stories, the presenters shared their experiences and reviewed recent literature and policy changes relating to the topic. This mini-plenary focused on three themes:

1. Easing the transition back to work after the birth of a child.

2. Coping with the tension between being a parent and pediatrician.

3. The role that divisions, departments, and institutions can play in supporting parents and promoting workplace engagement.

The session concluded with a robust question-and-answer portion where participants built upon the themes above and shared their own experiences as pediatric hospitalist parents.

Key takeaways

- “Use your voice.” Physicians who are parents must continue having conversations about the challenging aspects of being a parent and hospitalist and advocate for the changes they would like to see.

- There will always be tension as a physician parent, but we can learn to embrace it while also learning how to ask for help, set boundaries, and share when we are struggling.

- There are numerous challenges for hospitalists who are parents because of poor parental leave policies in the United States, but this is slowly changing. For example, starting in July 2021, the ACGME mandated 6 weeks of parental leave during training without having to extend training.

- “You are not alone.” The presenters emphasized that their reason for hosting this session was to shed light on this topic and let all pediatric hospitalist parents know that they are not alone in this experience.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

Trio of awardees illustrate excellence in SHM chapters

2020 required resiliency, innovation

The Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual Chapter Excellence Exemplary Awards have additional meaning this year, in the wake of the persistent challenges faced by the medical profession as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The Chapter Excellence Award program is an annual rewards program to recognize outstanding work conducted by chapters to carry out the SHM mission locally,” Lisa Kroll, associate director of membership at SHM, said in an interview.

The Chapter Excellence Award program is composed of Status Awards (Platinum, Gold, Silver, and Bronze) and Exemplary Awards. “Chapters that receive these awards have demonstrated growth, sustenance, and innovation within their chapter activities,” Ms. Kroll said.

For 2020, the Houston Chapter received the Outstanding Chapter of the Year Award, the Hampton Roads (Va.) Chapter received the Resiliency Award, and Amith Skandhan, MD, SFHM, of the Wiregrass Chapter in Alabama, received the Most Engaged Chapter Leader Award.

“SHM members are assigned to a chapter based on their geographical location and are provided opportunities for education and networking through in-person and virtual events, volunteering in a chapter leadership position, and connecting with local hospitalists through the chapter’s community in HMX, SHM’s online engagement platform,” Ms. Kroll said.

The Houston Chapter received the Outstanding Chapter of the Year Award because it “exemplified high performance during 2020,” Ms. Kroll said. “During a particularly challenging year for everyone, the chapter was able to rethink how they could make the largest impact for members and expand their audience with the use of virtual meetings, provide incentives for participants, and expand their leadership team.”

“The Houston Chapter has been successful in establishing a Houston-wide Resident Interest Group to better involve and provide SHM resources to the residents within the four local internal medicine residency programs who are interested in hospital medicine,” Ms. Kroll said. “Additionally, the chapter created its first curriculum to assist residents in knowing more about hospital medicine and how to approach the job search. The Houston Chapter has provided sources of support, both emotionally and professionally, and incorporated comedians and musicians into their web meetings to provide a much-needed break from medical content.”

The Resiliency Award is a new SHM award category that goes to one chapter that has gone “above and beyond” to showcase their ability to withstand and rise above hardships, as well as to successfully adapt and position the chapter for long term sustainability and success, according to Ms. Kroll. “The Hampton Roads Chapter received this award for the 2020 year. Some of the chapter’s accomplishments included initiating a provider well-being series.”

Ms. Kroll noted that the Hampton Roads Chapter thrived by trying new approaches and ideas to bring hospitalists together across a wide region, such as by utilizing the virtual format to provide more specialized outreach to providers and recognize hospitalists’ contributions to the broader community.

The Most Engaged Chapter Leader Award was given to Alabama-based hospitalist Dr. Skandhan, who “has demonstrated how he goes above and beyond to grow and sustain the Wiregrass Chapter of SHM and continues to carry out the SHM mission,” Ms. Kroll said.

Dr. Skandhan’s accomplishments in 2020 include inviting four Alabama state representatives and three Alabama state senators to participate in a case discussion with Wiregrass Chapter leaders; creating and moderating a weekly check-in platform for the Alabama state hospital-medicine program directors’ forum through the Wiregrass Chapter – a project that enabled him to encourage the sharing of information between hospital medicine program directors; and working with the other Wiregrass Chapter leaders to launch a poster competition on Twitter with more than 80 posters presented.

Hampton Roads Chapter embraces virtual connections

“I believe chapters are one of the best answers to the question: ‘What’s the value of joining SHM?’” Thomas Miller, MD, FHM, leader of the Hampton Roads Chapter, said in an interview.

“Sharing ideas and experiences with other hospitalist teams in a region, coordinating efforts to improve care, and the personal connection with others in your field are very important for hospitalists,” he emphasized. “Chapters are uniquely positioned to do just that. Recognizing individual chapters is a great way to highlight these benefits and to promote new ideas – which other chapters can incorporate into their future plans.”

The Hampton Roads Chapter demonstrated its resilience in many ways during the challenging year of 2020, Dr. Miller said.

“We love our in-person meetings,” he emphasized. “When 2020 took that away from us, we tried to make the most of the situation by embracing the reduced overhead of the virtual format to offer more specialized outreach programs, such as ‘Cultural Context Matters: How Race and Culture Impact Health Outcomes’ and ‘Critical Care: Impact of Immigration Policy on U.S. Healthcare.’ ” The critical care and immigration program “was a great outreach to our many international physicians who have faced special struggles during COVID; it not only highlighted these issues to other hospitalists, but to the broader community, since it was a joint meeting with our local World Affairs Council,” he added.

Dr. Miller also was impressed with the resilience of other chapter members, “such as our vice president, Dr. Gwen Williams, who put together a provider well-being series, ‘Hospitalist Well Being & Support in Times of Crisis.’ ” He expressed further appreciation for the multiple chapter members who supported the chapter’s virtual resident abstract/poster competition.

“Despite the limitations imposed by 2020, we have used unique approaches that have held together a strong core group while broadening outreach to new providers in our region through programs like those described,” said Dr. Miller. “At the same time, we have promoted hospital medicine to the broader community through a joint program, increased social media presence, and achieved cover articles in Hampton Roads Physician about hospital medicine and a ‘Heroes of COVID’ story featuring chapter members. We also continued our effort to add value by providing ready access to the newly state-mandated CME with ‘Opiate Prescribing in the 21st Century.’

“In a time when even family and close friends struggled to maintain connection, we found ways to offer that to our hospitalist teams, at the same time experimenting with new tools that we can put to use long after COVID is gone,” Dr. Miller added.

Houston Chapter supports residents, provides levity

“As a medical community, we hope that the award recognition brings more attention to the issues for which our chapter advocates,” Jeffrey W. Chen, MD, of the Houston Chapter and a hospitalist at Memorial Hermann Hospital Texas Medical Center, said in an interview.

“We hope that it encourages more residents to pursue hospital medicine, and encourages early career hospitalists to get plugged in to the incredible opportunities our chapter offers,” he said. “We are so incredibly honored that the Society of Hospital Medicine has recognized the decade of work that has gone on to get to where we are now. We started with one officer, and we have worked so hard to grow and expand over the years so we can help support our fellow hospitalists across the city and state.

“We are excited about what our chapter has been able to achieve,” said Dr. Chen. “We united the four internal medicine residencies around Houston and created a Houston-wide Hospitalist Interest Group to support residents, providing them the resources they need to be successful in pursuing a career in hospital medicine. We also are proud of the support we provided this year to our early career hospitalists, helping them navigate the transitions and stay up to date in topics relevant to hospital medicine. We held our biggest abstract competition yet, and held a virtual research showcase to celebrate the incredible clinical advancements still happening during the midst of the pandemic.

“It was certainly a tough and challenging year for all chapters, but despite us not being able to hold the in-person dinners that our members love so much, we were proud that we were able to have such a big year,” said Dr. Chen. “We were thankful for the physicians who led our COVID-19 talks, which provided an opportunity for hospitalists across Houston to collaborate and share ideas on which treatments and therapies were working well for their patients. During such a difficult year, we also hosted our first wellness events, including a comedian and band to bring some light during tough times.”

Strong leader propels team efforts

“The Chapter Exemplary Awards Program is important because it encourages higher performance while increasing membership engagement and retaining talent,” said Dr. Skandhan, of Southeast Health Medical Center in Dothan, Ala., and winner of the Most Engaged Chapter Leader award. “Being recognized as the most engaged chapter leader is an honor, especially given the national and international presence of SHM.

“Success is achieved through the help and support of your peers and mentors, and I am fortunate to have found them through this organization,” said Dr. Skandhan. “This award brings attention to the fantastic work done by the engaged membership and leadership of the Wiregrass Chapter. This recognition makes me proud to be part of a team that prides itself on improving the quality health and wellbeing of the patients, providers, and public through innovation and collaboration; this is a testament to their work.”

Dr. Skandhan’s activities as a chapter leader included visiting health care facilities in the rural Southeastern United States. “I slowly began to learn how small towns and their economies tied into a health system, how invested the health care providers were towards their communities, and how health care disparities existed between the rural and urban populations,” he explained. “When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, I worried about these hospitals and their providers. COVID-19 was a new disease with limited understanding of the virus, treatment options, and prevention protocols.” To help smaller hospitals, the Wiregrass Chapter created a weekly check-in for hospital medicine program directors in the state of Alabama, he said.

“We would start the meeting with each participant reporting the total number of cases, ventilator usage, COVID-19 deaths, and one policy change they did that week to address a pressing issue,” Dr. Skandhan said. “Over time the meetings helped address common challenges and were a source of physician well-being.”