User login

SC Insulin Order Sets and Protocols

Inpatient glycemic control and hypoglycemia are issues with well deserved increased attention in recent years. Prominent guidelines and technical reviews have been published,13 and a recent, randomized controlled trial demonstrated the superiority of basal bolus insulin regimens compared to sliding‐scale regimens.4 Effective glycemic control for inpatients has remained elusive in most medical centers. Recent reports57 detail clinical inertia and the continued widespread use of sliding‐scale subcutaneous insulin regimens, as opposed to the anticipatory, physiologic basal‐nutrition‐correction dose insulin regimens endorsed by these reviews.

Inpatient glycemic control faces a number of barriers, including fears of inducing hypoglycemia, uneven knowledge and training among staff, and competing institutional and patient priorities. These barriers occur in the background of an inherently complex inpatient environment that poses unique challenges in maintaining safe glycemic control. Patients frequently move across a variety of care teams and geographic locations during a single inpatient stay, giving rise to multiple opportunities for failed communication, incomplete handoffs, and inconsistent treatment. In addition, insulin requirements may change dramatically due to variations in the stress of illness, exposure to medications that effect glucose levels, and varied forms of nutritional intake with frequent interruption. Although insulin is recognized as one of the medications most likely to be associated with adverse events in the hospital, many hospitals do not have protocols or order sets in place to standardize its use.

A Call to Action consensus conference,8, 9 hosted by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA), brought together many thought leaders and organizations, including representation from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), to address these barriers and to outline components necessary for successful implementation of a program to improve inpatient glycemic control in the face of these difficulties. Institutional insulin management protocols and standardized insulin order sets (supported by appropriate educational efforts) were identified as key interventions. It may be tempting to quickly deploy a generic insulin order set in an effort to improve care. This often results in mediocre results, due to inadequate incorporation of standardization and guidance into the order set and other documentation tools, and uneven use of the order set.

The SHM Glycemic Control Task Force (GCTF) recommends the following steps for developing and implementing successful protocols and order sets addressing the needs of the noncritical care inpatient with diabetes/hyperglycemia.

-

Form a steering committee for this work, and assess the current processes of care.

-

Identify best practices and preferred regimens to manage diabetes and hyperglycemia in the hospital.

-

Integrate best practices and preferred institutional choices into an inpatient glycemic control protocol. Crystallize your protocol into a one page summary.

-

Place guidance from your protocol into the flow of work, by integrating it into standardized subcutaneous insulin order sets and other documentation and treatment tools.

-

Monitor the use of your order sets and protocol. Intervene actively on nonadherents to your protocol and those with poor glycemic control, and revise your protocol/order sets as needed.

IDENTIFYING AND INCORPORATING KEY CONCEPTS AND BEST PRACTICES

A protocol is a document that endorses specific monitoring and treatment strategies in a given institution. This potentially extensive document should provide guidance for transitions, special situations (like steroids and total parenteral nutrition [TPN]) and should outline preferred insulin regimens for all of the most common nutritional situations. One of the most difficult parts of creating a protocol is the assimilation of all of the important information on which to base decisions. Your protocol and order set will be promoting a set of clinical practices. Fortunately, the current best practice for noncritical care hyperglycemic patients has been summarized by several authoritative sources,13, 811 including references from the SHM Glycemic Task Force published in this supplement.4, 12

Table 1 summarizes the key concepts that should be emphasized in a protocol for subcutaneous insulin management in the hospital. We recommend embedding guidance from your protocol into order sets, the medication administration record, and educational materials. Although the details contained in a protocol and order set might vary from one institution to another, the key concepts should not. The remainder of this article provides practical information about how these concepts and guidance for how preferred insulin regimens should be included in these tools. Appendices 1 and 2 give examples of an institutional one‐page summary protocol and subcutaneous insulin order set, respectively.

| 1. Establish a target range for blood glucose levels. |

| 2. Standardize monitoring of glucose levels and assessment of long‐term control (HbA1c). |

| 3. Incorporate nutritional management. |

| 4. Prompt clinicians to consider discontinuing oral antihyperglycemic medications. |

| 5. Prescribe physiologic (basal‐nutrition‐correction) insulin regimens. |

| a. Choose a total daily dose (TDD). |

| b. Divide the TDD into physiologic components of insulin therapy and provide basal and nutritional/correction separately. |

| c. Choose and dose a basal insulin. |

| d. Choose and dose a nutritional (prandial) insulin |

|

i. Match exactly to nutritional intake (see Table 2). |

| ii. Include standing orders to allow nurses to hold nutritional insulin for nutritional interruptions and to modify nutritional insulin depending on the actual nutritional intake. |

| e. Add correction insulin |

| i. Match to an estimate of the patients insulin sensitivity using prefabricated scales. |

| ii. Use the same insulin as nutritional insulin. |

| 6. Miscellaneous |

| a. Manage hypoglycemia in a standardized fashion and adjust regimen to prevent recurrences. |

| b. Provide diabetes education and appropriate consultation. |

| c. Coordinate glucose testing, nutrition delivery, and insulin administration. |

| d. Tailor discharge treatment regimens to the patient's individual circumstances and arrange for proper follow‐up. |

Standardize the Monitoring of Blood Glucose Values and Glucosylated Hemoglobin

Guidance for the coordination of glucose testing, nutrition delivery, and insulin administration, should be integrated into your protocols, and order sets. For noncritical care areas, the minimal frequency for blood glucose monitoring for patients who are eating is before meals and at bedtime. For the patient designated nothing by mouth (NPO) or the patient on continuous tube feeding, the type of nutritional/correction insulin used should drive the minimum frequency (every 4‐6 hours if rapid acting analog insulins [RAA‐I] are used, and every 6 hours if regular insulin is used). Directions for administering scheduled RAA‐I immediately before or immediately after nutrition delivery should be incorporated into protocols, order sets, and medication administration records. Unfortunately, having this guidance in the order sets and protocols does not automatically translate into its being carried out in the real world. Wide variability in the coordination of glucose monitoring, nutritional delivery, and insulin administration is common, so monitoring the process to make sure the protocol is followed is important.

Obtaining a glucosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level is important in gauging how well the patient's outpatient regimen is maintaining glycemic control, distinguishing stress hyperglycemia from established diabetes, and guiding the inpatient approach to glycemic control. ADA guidelines2, 3 endorse obtaining HbA1c levels of inpatients if these levels are not already available from the month prior to admission.

Establish a Target Range for Blood Glucose in NonCritical Care Areas

It is important to adopt a glycemic target that is institution‐wide, for critical care areas and noncritical care areas alike. Your glycemic target need not be identical to the ADA/AACE glycemic targets, but should be similar to them.

Examples of institutional glycemic targets for noncritical care areas:

-

Preprandial target 90‐130 mg/dL, maximum random glucose 180 mg/dL (ADA/AACE consensus target)

-

90‐150 mg/dL (a target used in some hospitals)

-

Preprandial target 90‐130 mg/dL for most patients, 100‐150 mg/dL if there are hypoglycemia risk factors, and 180 mg/dL if comfort‐care or end‐of‐life care (a more refined target, allowing for customization based on patient characteristics).

Your multidisciplinary glycemic control steering committee should pick the glycemic target it can most successfully implement and disseminate. It is fine to start with a conservative target and then ratchet down the goals as the environment becomes more accepting of the concept of tighter control of blood glucose in the hospital.

Although the choice of glycemic target is somewhat arbitrary, establishing an institutional glycemic target is critical to motivate clinical action. Your committee should design interventions, for instances when a patient's glycemic target is consistently not being met, including an assignment of responsibility.

Prompt Clinicians to Consider Discontinuing Oral Agents

Oral antihyperglycemic agents, in general, are difficult to quickly titrate to effect, and have side effects that limit their use in the hospital. In contrast, insulin acts rapidly and can be used in virtually all patients and clinical situations, making it the treatment of choice for treatment of hyperglycemia in the hospital.3, 11, 12 In certain circumstances, it may be entirely appropriate to continue a well‐controlled patient on his or her prior outpatient oral regimen. It is often also reasonable to resume oral agents in some patients when preparing for hospital discharge.

Incorporate Nutritional Management

Because diet is so integral to the management of diabetes and hyperglycemia, diet orders should be embedded in all diabetes or insulin‐related order sets. Diets with the same amount of carbohydrate with each meal should be the default rule for patients with diabetes. Nutritionist consultation should be considered and easy to access for patients with malnutrition, obesity, and other common conditions of the inpatient with diabetes.

Access Diabetes Education and Appropriate Consultation

Diabetes education should be offered to all hyperglycemic patients with normal mental status, complete with written materials, a listing of community resources, and survival skills. Consultation with physicians in internal medicine or endocrinology for difficult‐to‐control cases, or for cases in which the primary physician of record is not familiar with (or not adherent to) principles of inpatient glycemic management, should be very easy to obtain, or perhaps mandated, depending on your institution‐specific environment.

Prescribe Physiologic (Basal‐Nutritional‐Correction Dose) Insulin Regimens

Physiologic insulin use is the backbone of the recommended best practice for diabetes and hyperglycemia management in the hospital. The principles of such regimens are summarized elsewhere in this supplement.12 These principles will not be reiterated in detail here, but the major concepts that should be integrated into the protocols and order sets will be highlighted.

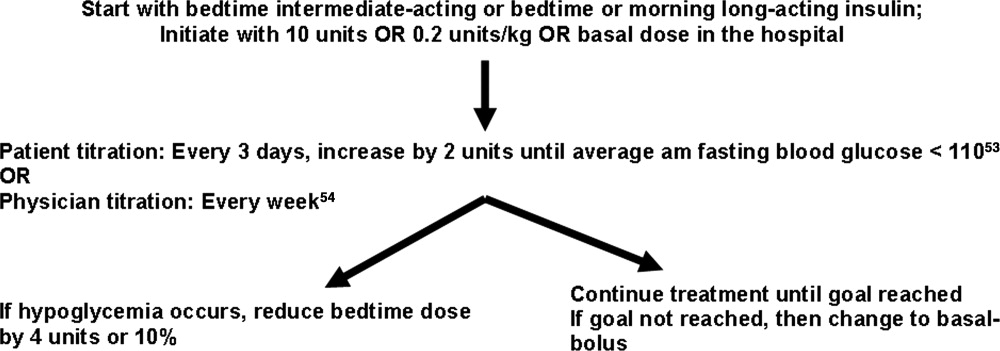

Choose a Total Daily Dose

Clinicians need guidance on how much subcutaneous insulin they should give a patient. These doses are well known from clinical experience and the published literature. The fear of hypoglycemia usually results in substantial underdosing of insulin, or total avoidance of scheduled insulin on admission. Your team should provide guidance for how much insulin to start a patient on when it is unclear from past experience how much insulin the patient needs. Waiting a few days to see how much insulin is required via sliding‐scale‐only regimens is a bad practice that should be discouraged for patients whose glucose values are substantially above the glycemic target. The total daily dose (TDD) can be estimated in several different ways (as demonstrated in Appendix 1 and 2), and protocols should make this step very clear for clinicians. Providing a specific location on the order set to declare the TDD may help ensure this step gets done more reliably. Some institutions with computer physician order entry (CPOE) provide assistance with calculating the TDD and the allocation of basal and nutritional components, based on data the ordering physician inputs into the system.

Select and Dose a Basal Insulin

Your protocol should describe how the TDD should be divided between basal and nutritional insulin. We generally recommend 50% of the TDD be given as basal insulin, with the other 50% administered on a scheduled basis to cover glycemic excursions from nutritional intake. The 50/50 rule is simple and generally works well, and should be widely promoted. However, there are exceptions to this rule that should be incorporated into your full protocol and educational programs. The order set should have separate steps for ordering basal insulin, nutritional insulin, and correction insulin. The advantage to providing these insulin components separately is that it allows them to be independently manipulated (eg, if a patient is unable to tolerate a meal, nutritional insulin is held, but basal insulin and correction insulin are continued).

The SHM GCTF specifically endorses long acting insulin (glargine and detemir) as the preferred basal insulin in the hospital setting, thus discouraging the use of neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin and fixed combination insulin formulations (Table 2). In the absence of randomized controlled trials demonstrating superiority of the glargine or detemir to NPH insulin in the hospital, this endorsement deserves some further explanation. Although we believe that correctly dosed NPH containing insulin regimens can attain effective and safe glycemic control in the hospital setting, it is more difficult to standardize their use and adjust for fluctuations in nutritional intake. Glargine and detemir have much less pronounced spikes in their effect than NPH, rendering them relatively peakless in comparison. This pharmacokinetic profile allows for continued dosing with minimal or no correction when nutrition intake is variable, and allow for consistent reinforcement of the basal‐nutritional‐correction insulin concept.

| Nutritional situation | Necessary insulin components | Preferred regimen* |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| NPO (or clear liquids) | Basal insulin: 50% of TDD. Nutritional insulin: None. | Basal insulin: glargine given once daily or detemir given twice daily. Nutritional insulin: None. Correctional insulin: Regular insulin q 6 hours or RAA insulin q 4 hours. Other comments: Dextrose infusion (e.g., D5 containing solution at 75‐150 cc/hour) recommended when nutrition is held. An IV insulin infusion is preferred for management of prolonged fasts or fasting type 1 diabetes patients. |

| Eating meals | Basal insulin: 50% of TDD. Nutritional insulin: 50% of TDD, divided equally before each meal. | Basal insulin: glargine given once daily or detemir given twice daily. Nutritional insulin: RAA insulin with meals. Correctional insulin: RAA insulin q AC and HS (reduced dose at HS). |

| Bolus tube feeds | Basal insulin: 40% of TDD. Nutritional insulin: 60% of the TDD, divided equally before each bolus feed. | Basal insulin: glargine given once daily or detemir given twice daily. Nutritional insulin: RAA insulin with each bolus. Correctional insulin: RAA insulin with each bolus. |

| Continuous tube feeds | Basal insulin: 40% (conservative) of TDD. Nutritional insulin: 60% of the TDD in divided doses. | Basal insulin: glargine given once daily or detemir given twice daily. Nutritional insulin: RAA insulin q 4 hours or regular insulin q 6 hours. Correctional insulin: Should match nutritional insulin choice. |

| Parenteral nutrition | Insulin is usually given parenterally, with the nutrition | Initially, a separate insulin drip allows for accurate dose‐finding. Then, 80% of amount determined as TDD using drip is added to subsequent TPN bags as regular insulin. Use correctional subcutaneous insulin doses cautiously, in addition. |

There are some caveats to this general recommendation. First, patients who are well controlled on home regimens with NPH basal insulin can (and sometimes should) stay on the regimen that has worked well for them. However, extra vigilance in reducing the dose for reductions in nutrition is required, because NPH is generally used to cover both nutritional and basal requirements. Second, extensive experience with glargine and detemir are not available in obstetric populations. They are not U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for use in pregnant patients and formally carry a Class C rating, whereas NPH insulin has been used safely in obstetric populations for decades. Third, the insulin regimen used as an inpatient is not necessarily the preferred regimen to prescribe at discharge: cost, patient preferences, HbA1c level, and other factors should be considered in making this choice.

Select and Dose a Nutritional (Prandial) Insulin

The step for ordering nutritional insulin should assist the clinician in matching the insulin to the type of nutrition that the patient is receiving. For example, rapid‐acting insulin analogs are preferred over regular insulin in the eating patient, in view of their more physiologic profile, which averts the insulin stacking that can occur with regular insulin. If regular insulin is used as the preferred institutional choice for eating patients, the lunchtime dose should be reduced or eliminated altogether, to eliminate insulin stacking.

Table 2 outlines the SHM GCTF preferred regimens for different nutritional situations.

There should be a standing order for nutritional insulin to be held when nutrition is interrupted, whether intentional or unintentional. Patients with interrupted tube feedings could have standing orders for a dextrose infusion to replace the tube feeding carbohydrate load and prevent hypoglycemia. Ideally, there should also be a standing order allowing for real‐time management of the patient with uncertain nutritional intake. For example, when a patient's premeal assessment reveals that she may not tolerate the meal, the patient should be allowed to attempt to eat, and then the nutritional insulin should be given after the meal, in proportion to the amount of food that was eaten. This type of order will require significant nursing education and process redesign in many hospitals, but is essential for matching nutritional insulin to actual intake.

Add Correction Insulin

There is no convincing evidence for the benefit of correction (sliding‐scale) insulin in the inpatient setting, although a randomized trial demonstrating the superiority of basal/nutritional insulin regimens to sliding‐scale only regimens did incorporate a correction insulin scale as an adjunct to the superior basal/nutritional regimen.4 The SHM GCTF again emphasizes that control of hyperglycemia should be proactive and anticipatory of insulin needs, rather than reactive to hyperglycemia. Nonetheless, unexpected hyperglycemic excursions are common, and the use of correction insulin remains a pervasive and arguably logical practice. If correction insulin is used, it should be ordered as a separate step after considering basal and nutrition insulin needs. The doses of scheduled insulin should be adjusted regularly if correction insulin is consistently being required. Ideally, the prescriber should choose a preformatted corrective insulin scale, based on the patient's insulin sensitivity (Appendix 2). There should be a prompt to use the same type of insulin that is being used for nutritional insulin, and there should be instructions that this insulin is given in addition to the basal and nutritional insulin to correct for hyperglycemia. Nocturnal correction‐dose scales should be reduced in the eating patient.

Even after limiting insulin regimens to those in Table 2, multidisciplinary glycemic control teams are still left with several options within these SHM‐preferred regimens. We recommend that your team choose a single, institutionally‐preferred basal‐nutritional‐correction insulin combination for each situation.

Choosing one preferred option for these situations is advantageous because:

-

You can communicate preferred regimens more simply and succinctly to all staff.

-

You eliminate all inappropriate choices for insulin regimens for that situation, as well as some other less preferred, but acceptable choices.

-

You can encourage regimens that are most economical (by promoting the insulin regimens that reflect your hospital formulary choices).

-

Staff members can become very familiar with a few regimens, instead of being confused by a multitude of them. They can identify variations from your preferred choices and target these patients for extra scrutiny and actions should they fail to meet glycemic targets.

Although virtually every institution can provide specific guidance on insulin management in a protocol, there are tradeoffs inherent in how restrictive you can be in pushing these preferred choices in your order sets. Should you eliminate alternate basal or nutritional insulin choices from your order sets? As you integrate more and more of your preferred algorithm and regimens into your order set, you will gain incremental improvement in the standardization of inpatient insulin management. However, you reduce not only variability in ordering, but also the choices available to your prescribers and patients, and in effect you are pushing the providers to use an insulin regimen that often differs from the patient's outpatient regimen. If your institution is not yet ready to go with a single preferred insulin, simply listing your preferred insulin first with the annotation preferred can be enough to increase the use of the preferred insulin.

We endorse building the most protocol‐driven, proscriptive, insulin order set that the Glycemic Control Steering Committee believes their medical staff will accept. There are some caveats to this endorsement. First, there must be extra efforts on the backend of the admission, to ensure that the antihyperglycemic regimen is tailored to the unique needs of the patient (this is discussed further below). Second, a protocol‐driven approach is not a substitute for a good educational program for health care providers or well‐informed clinical judgment. Education should reinforce major concepts driving the protocol and should also highlight exceptions to the rule. Variance from the protocol endorsed choices should be allowed (and even encouraged) when the variance is driven by patient factors (as opposed to provider whim). Learning from this variance is a key concept in refining protocols. Education ideally should not be limited to only protocol‐endorsed choices, as staff should be familiar with the full range of antihyperglycemia regimens seen in inpatient and outpatient settings.

Special Situations

Most of the preferred regimens for different situations are outlined in Table 2 in a straightforward manner, and can be depicted in your protocols and order sets in the same way. Some conditions have enough complexity, however, that you will have difficulty placing all of the details into your one‐page protocol and order set. Details should be placed on your more detailed protocol, and educational programs should include the topics outlined below. Although insulin infusion is often the option that would provide the most reliable and expedient control of hyperglycemia in these special situations, it is an option not available in many noncritical care settings. Therefore, the discussion is limited to subcutaneous insulin control regimens.

Patient on Continuous Tube Feeding

The SHM GCTF endorses glargine or detemir as the basal insulin of choice for this setting. The nutritional and correction insulin of choice is either an RAA‐I every 4 hours (q4h), or regular insulin every 6 hours (q6h). We endorse this choice because it retains the basal‐nutritional‐correction dose concept, generally allows for continued basal insulin use if the tube feedings become interrupted, and is amenable to building a consistent institutional protocol.

There are some important caveats to this recommendation. First, realize that almost any regimen that provides a stable insulin supply would be acceptable, and many institutions will use glargine or detemir to cover both basal and nutritional needs. The downside to using large boluses of long‐acting insulin in this clinical situation is that any unexpected interruption of the feedings will necessitate prolonged infusions of dextrate 10% solution (D10) to avoid hypoglycemia

Second, because of the glycemic load inherent in tube feedings, maintenance of glycemic control in the setting of enteral feeding may be best managed by providing a higher percentage of the TDD as nutritional insulin. In these cases, ratios of basal to nutritional insulin of 40:60, or even less basal insulin, may be appropriate.

Glucocorticoid Therapy

High‐dose glucocorticoids are strongly associated with increased insulin requirements. The degree of hyperglycemia induced by steroids varies significantly from patient to patient, and the pattern of hyperglycemia will vary depending on the pattern of steroid administration. The general principle to keep in mind is that the hyperglycemia induced by a steroid dose will peak 8‐12 hours after it is given, so insulin regimens to address this should take this effect into account. For example, giving a long‐acting basal insulin like glargine to accommodate the hyperglycemic effect of a steroid bolus given in the morning would be inappropriate because the steroid effect would wane and then disappear overnight, leading to insulin‐induced hypoglycemia. NPH insulin can be ideal in this setting, either by itself, or by layering it on top of an existing regimen.

Another caveat: glucocorticoids exert their predominate effect on insulin sensitivity in muscle (as opposed to the liver), and as a result, have their most notable effect on postprandial glucose. For this reason, the best insulin regimens for this situation may use proportionally less basal insulin and more nutritional insulin. One common regimen calls for keeping the basal insulin dose the same as the preglucocorticoid dose, while escalating the RAA insulin dose at lunch and dinner.

Given the complexities of covering steroid‐induced hyperglycemia and its high prevalence in certain populations (such as transplantation patients and patients undergoing chemotherapy), this would be an excellent area on which to focus expertise. Examples include routine endocrinology consultation, intervention by a special glycemic control team, or incorporating routine glucose monitoring and triggers for initiating insulin infusion into the protocols for chemotherapy and transplantation patients.

Regiment the Management of Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia is defined by the ADA as a blood glucose of 70 mg/dL or less, based on the physiologic changes that can occur at this glucose level, even in subjectively asymptomatic patients.3 Protocols for management of hypoglycemia should be linked to your diabetes/hyperglycemia protocols. There are many hypoglycemia protocols available for review in the SHM Glycemic Control Resource Room and Glycemic Control Implementation Guide.10 Some common themes for effective implementation stand out. First, the protocols need to walk the balance between simplicity of use, and the need to provide instructions that will provide guidance in a variety of patient situations. Second, the protocols need to be nurse driven, so that nurses can initiate treatment without waiting for a physician order. Third, education and instruction regarding recognition of risk factors, and avoidance of hypoglycemia are needed to support a successful protocol. Importantly, any hypoglycemic event should lead to a reconsideration of the current anti‐hyperglycemic regimen so that future events can be prevented.

Plan for Discharge and Provide Guidance for the Transition

Your institution should have policies and procedures outlining all the steps needed to complete the important transition out of the hospital. At a minimum, this planning should include adequate education (including a learner assessment), appropriate follow‐up, referral to community resources, and a discharge glycemic control regimen that is tailored to the educational, financial, and motivational profile of a patient. The more your inpatient insulin management is driven by protocol, the more likely it is the patient will be on an inpatient treatment plan that differs from their outpatient regimen; therefore, it is even more important to plan this transition carefully and reliably.

Communicating the accurate hyperglycemia related diagnosis and related problems to the primary care provider is important for good care, perhaps even more so for patients who had hyperglycemia while hospitalized without a prior diagnosis of diabetes. Some centers place a prompt for hyperglycemia related diagnosis in the order set and/or discharge paperwork, to remind the clinician to convey the diagnosis to the primary provider, and to encourage more complete documentation. Improved documentation can also improve the business case for glycemic control, along with other strategies outlined elsewhere in this supplement.13

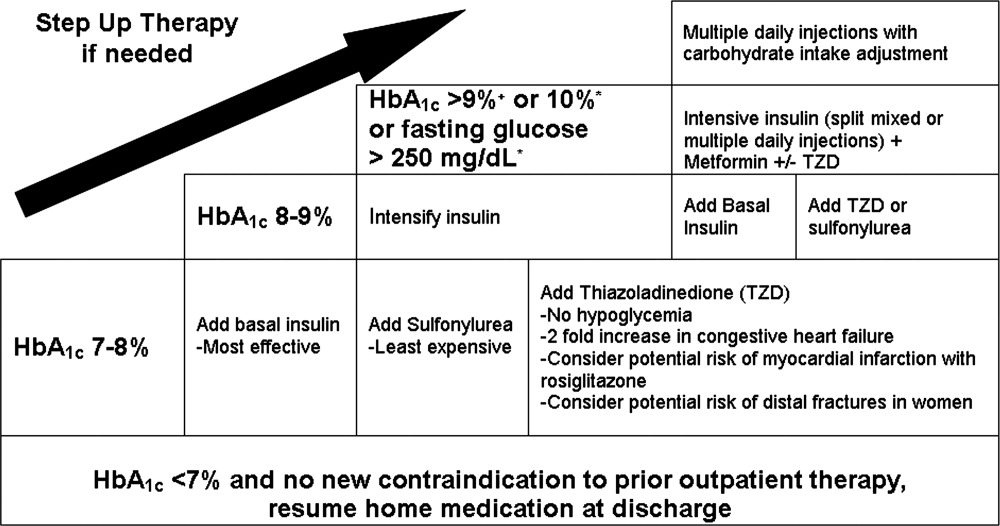

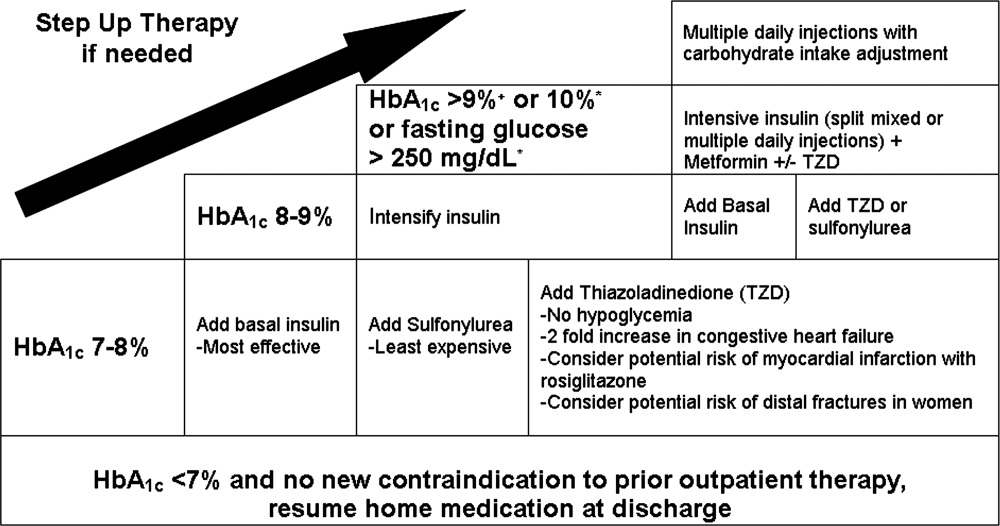

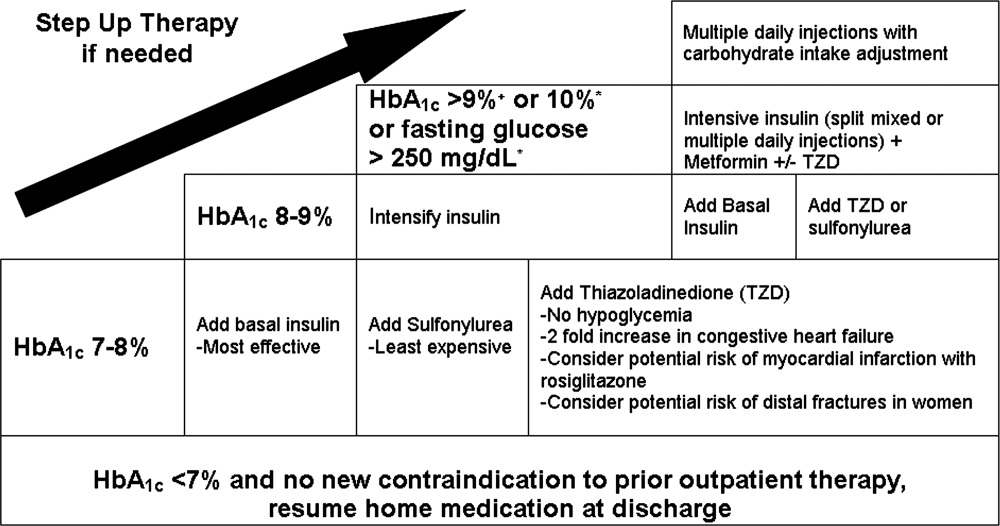

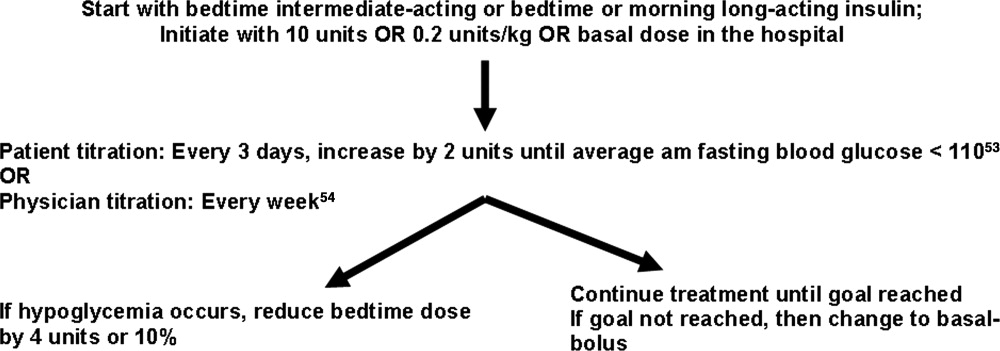

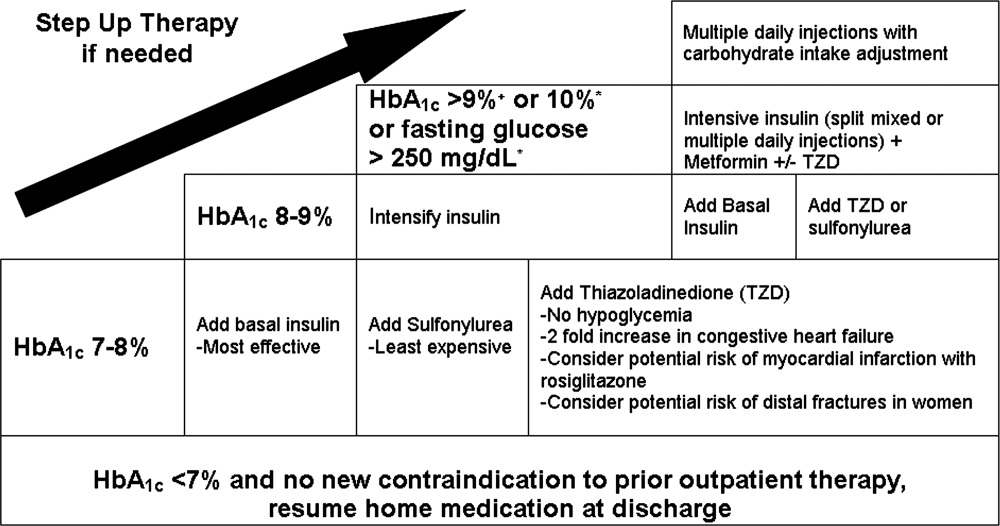

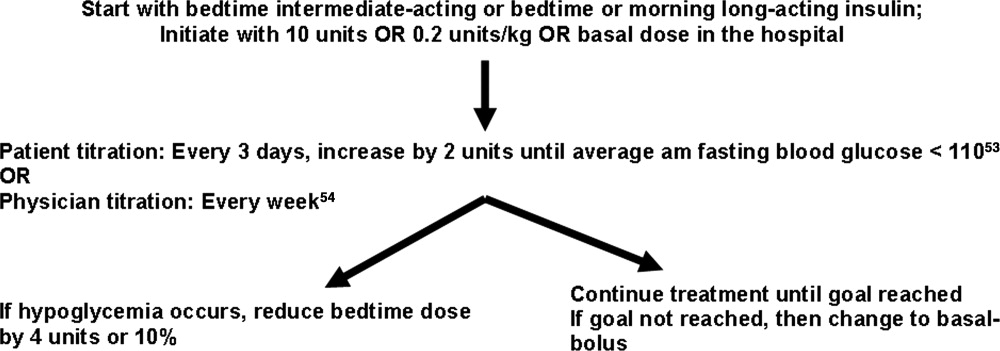

Transitions in care (including transitions out of the hospital and off of infusion insulin) are discussed in more detail14, 15 elsewhere in this supplement. The principles outlined in these references should be incorporated into your institutional protocol. Briefly, not all patients require or are capable of intensive basal‐bolus regimens upon discharge. The HbA1c can be very valuable in arriving at the optimal outpatient regimen.14 The capacities and preferences of the patient and the context of his or her outpatient care environment (including the preferences of the primary care provider) must be taken into consideration as an outpatient management program is planned.

PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER: MAKE SURE YOUR PROTOCOL/ORDER SET IS EASY TO USE AND WIDELY UTILIZED

When standardizing hospital management of diabetes and hyperglycemia, we recommend building the full protocol first, then crystallizing the protocol into a one‐page summary that can be widely disseminated. The protocol guidance is then incorporated into the order set and nursing medical administration record (MAR). Again, we recommend the most proscriptive and protocol‐driven order set feasible within the constraints of medical staff support. The example order set in Appendix 2 illustrates this approach along with other desirable features:

-

Check‐box simplicity on when to order appropriate glucose monitoring.

-

Prompt for the proper hyperglycemia‐related diagnosis.

-

Prompts to document diagnosis and to order HbA1c level.

-

Use of encouraged insulin terminology: basal, prandial (or nutritional), and correction. Language is a powerful thing, and just getting staff to use these terms goes a long way toward the more physiologic prescribing of insulin.

-

Statement/reminder of a glycemic goal.

-

Prompts and contact information for appropriate consultation.

-

Elimination of unapproved abbreviations (such as U for units).

-

Stating both generic and brand names of insulin preparations.

-

Important timing cues for administration of insulin.

-

Several correction‐dose scales suitable for different insulin sensitivities. One size does NOT fit all.

-

Incorporation of a simple hypoglycemia protocol into the order set.

-

Insulin dosing guidelines available at the point of care (in this case, on the back of the order set).

Additional nursing‐specific cues (such as an admonition to never mix glargine insulin with other types of insulin) can also be included in the MAR whenever glargine is ordered.

Once you have protocols and order sets to guide providers, you need to assure that they are used for the majority of hyperglycemic patients. Educational programs should introduce your interventions and the rationale for them. In order to make your method the default method of care, your team should survey all preprinted or CPOE insulin order sets of your institution. A review of postoperative, transfer, and admission order sets that all services use may reveal a half‐dozen or more embedded sliding‐scale insulin order sets that should be removed, with prompts to use the standardized insulin order set being placed in their stead.

Computerized order sets present both challenges and opportunities. Wording limitations and the scrolling nature can make concepts less clear, yet there is a capability for incorporating a hierarchical structure that allows for guiding the user through a more algorithmic approach. There is also a capacity to provide assistance with dosing calculations that do not exist in the paper world. Education remains of key importance for both methods.

MONITOR THE USE AND EFFECTIVENESS OF YOUR PROTOCOLS AND ORDER SETS

Creating and implementing protocols, order sets, and other tools is not the end of the journey to improve care. It is important to monitor order set utilization, insulin use patterns, and parameters measuring glycemic control and hypoglycemia, as outlined in more detail in another article in this supplement.16 In addition to summary data every month or so, we recommend daily reports that spur action in near real time. Triggers such as uncontrolled hyperglycemia, markedly elevated HbA1c levels, and nonphysiologic insulin regimens should initiate consultation, extra diabetes education, or referral to a glucose control team. If appropriate consultation is not readily available, the glycemic control steering group should lobby the administration to bolster this capability. Qualitative feedback from the frontline caregivers, as well as this quantitative data, can assist the local glycemic control champions in designing even more effective protocols, order sets, focused educational efforts, and concurrent mitigation of suboptimal care.

CONCLUSION

Diabetes, hyperglycemia, and iatrogenic hypoglycemia are common and important conditions affecting the noncritically ill inpatient. Interventional trials to validate the recommended noncritical care unit glycemic targets are needed. Although there is a growing consensus on best practices to care for these patients, numerous barriers and the complexity of caring for inpatients hamper the reliability of best practice delivery. Institutional protocols and protocol driven subcutaneous insulin orders, when implemented with the strategies outlined here, can be the key to delivering these best practices more reliably.

Appendix

- American College of Endocrinology Task Force on Inpatient Diabetes and Metabolic Control.American College of Endocrinology Position Statement on Inpatient Diabetes and Metabolic Control.Endocr Pract.2004;10:77–82.

- ,,,,,,.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.Diabetes Care.2004;27:553–591.

- American Diabetes Association.Standards of Medical Carein Diabetes‐2006.Diabetes Care.2006;29(suppl 1):s4–s42.

- ,,, et al.Randomized study of basal‐bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 Trial).Diabetes Care.2007;30:2181–2186.

- ,,,,.Inpatient management of diabetes and hyperglycemia among general medicine patients at a large teaching hospital.J Hosp Med.2006;1:145–150.

- ,,, et al.Diabetes care in the hospital: is there clinical inertia?J Hosp Med.2006;1:151–160.

- ,,, et al.Diabetes care in hospitalized non‐critically ill patients: more evidence for clinical inertia and negative therapeutic momentum.JHosp Med.2007;2:203–211.

- Inpatient Diabetes and Glycemic Control: A Call to Action Conference. Position Statement. AACE, February2006. Available at: http://www.aace.com/meetings/consensus/IIDC/IDGC0207.pdf. Accessed October, 2006.

- Proceedings of the American College of Endocrinology and American Diabetes Association Consensus Conference, Washington, DC, January 30–31, 2006. Endocr Pract.2006; 12(suppl 3):3–13.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Glycemic Control Task Force. Implementation Guide: Improving Glycemic Control, Preventing Hypoglycemia, and Optimizing Care of the Inpatient with Hyperglycemia and Diabetes. Published January 2007 on the Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed August,2007.

- .Management of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting.N Engl J Med.2006;355:1903–1911.

- ,,,,.Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in the hospital: a practical guide to subcutaneous insulin use in the non‐critically ill adult patient.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):S17–S28.

- ,.Practical strategies for developing the business case for hospital glycemic control teams.J Hosp Med2008;3(5):S76–S83.

- ,,,.Bridge over troubled waters: safe and effective transitions of the inpatient with hyperglycemia.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):S55–S65.

- ,,,.Designing and implementing insulin infusion protocols and order sets.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):S42–S54.

- ,,,,,.SHM Glycemic Control Task Force summary: practical recommendations for assessing the impact of glycemic control efforts.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):S66–S75.

Inpatient glycemic control and hypoglycemia are issues with well deserved increased attention in recent years. Prominent guidelines and technical reviews have been published,13 and a recent, randomized controlled trial demonstrated the superiority of basal bolus insulin regimens compared to sliding‐scale regimens.4 Effective glycemic control for inpatients has remained elusive in most medical centers. Recent reports57 detail clinical inertia and the continued widespread use of sliding‐scale subcutaneous insulin regimens, as opposed to the anticipatory, physiologic basal‐nutrition‐correction dose insulin regimens endorsed by these reviews.

Inpatient glycemic control faces a number of barriers, including fears of inducing hypoglycemia, uneven knowledge and training among staff, and competing institutional and patient priorities. These barriers occur in the background of an inherently complex inpatient environment that poses unique challenges in maintaining safe glycemic control. Patients frequently move across a variety of care teams and geographic locations during a single inpatient stay, giving rise to multiple opportunities for failed communication, incomplete handoffs, and inconsistent treatment. In addition, insulin requirements may change dramatically due to variations in the stress of illness, exposure to medications that effect glucose levels, and varied forms of nutritional intake with frequent interruption. Although insulin is recognized as one of the medications most likely to be associated with adverse events in the hospital, many hospitals do not have protocols or order sets in place to standardize its use.

A Call to Action consensus conference,8, 9 hosted by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA), brought together many thought leaders and organizations, including representation from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), to address these barriers and to outline components necessary for successful implementation of a program to improve inpatient glycemic control in the face of these difficulties. Institutional insulin management protocols and standardized insulin order sets (supported by appropriate educational efforts) were identified as key interventions. It may be tempting to quickly deploy a generic insulin order set in an effort to improve care. This often results in mediocre results, due to inadequate incorporation of standardization and guidance into the order set and other documentation tools, and uneven use of the order set.

The SHM Glycemic Control Task Force (GCTF) recommends the following steps for developing and implementing successful protocols and order sets addressing the needs of the noncritical care inpatient with diabetes/hyperglycemia.

-

Form a steering committee for this work, and assess the current processes of care.

-

Identify best practices and preferred regimens to manage diabetes and hyperglycemia in the hospital.

-

Integrate best practices and preferred institutional choices into an inpatient glycemic control protocol. Crystallize your protocol into a one page summary.

-

Place guidance from your protocol into the flow of work, by integrating it into standardized subcutaneous insulin order sets and other documentation and treatment tools.

-

Monitor the use of your order sets and protocol. Intervene actively on nonadherents to your protocol and those with poor glycemic control, and revise your protocol/order sets as needed.

IDENTIFYING AND INCORPORATING KEY CONCEPTS AND BEST PRACTICES

A protocol is a document that endorses specific monitoring and treatment strategies in a given institution. This potentially extensive document should provide guidance for transitions, special situations (like steroids and total parenteral nutrition [TPN]) and should outline preferred insulin regimens for all of the most common nutritional situations. One of the most difficult parts of creating a protocol is the assimilation of all of the important information on which to base decisions. Your protocol and order set will be promoting a set of clinical practices. Fortunately, the current best practice for noncritical care hyperglycemic patients has been summarized by several authoritative sources,13, 811 including references from the SHM Glycemic Task Force published in this supplement.4, 12

Table 1 summarizes the key concepts that should be emphasized in a protocol for subcutaneous insulin management in the hospital. We recommend embedding guidance from your protocol into order sets, the medication administration record, and educational materials. Although the details contained in a protocol and order set might vary from one institution to another, the key concepts should not. The remainder of this article provides practical information about how these concepts and guidance for how preferred insulin regimens should be included in these tools. Appendices 1 and 2 give examples of an institutional one‐page summary protocol and subcutaneous insulin order set, respectively.

| 1. Establish a target range for blood glucose levels. |

| 2. Standardize monitoring of glucose levels and assessment of long‐term control (HbA1c). |

| 3. Incorporate nutritional management. |

| 4. Prompt clinicians to consider discontinuing oral antihyperglycemic medications. |

| 5. Prescribe physiologic (basal‐nutrition‐correction) insulin regimens. |

| a. Choose a total daily dose (TDD). |

| b. Divide the TDD into physiologic components of insulin therapy and provide basal and nutritional/correction separately. |

| c. Choose and dose a basal insulin. |

| d. Choose and dose a nutritional (prandial) insulin |

|

i. Match exactly to nutritional intake (see Table 2). |

| ii. Include standing orders to allow nurses to hold nutritional insulin for nutritional interruptions and to modify nutritional insulin depending on the actual nutritional intake. |

| e. Add correction insulin |

| i. Match to an estimate of the patients insulin sensitivity using prefabricated scales. |

| ii. Use the same insulin as nutritional insulin. |

| 6. Miscellaneous |

| a. Manage hypoglycemia in a standardized fashion and adjust regimen to prevent recurrences. |

| b. Provide diabetes education and appropriate consultation. |

| c. Coordinate glucose testing, nutrition delivery, and insulin administration. |

| d. Tailor discharge treatment regimens to the patient's individual circumstances and arrange for proper follow‐up. |

Standardize the Monitoring of Blood Glucose Values and Glucosylated Hemoglobin

Guidance for the coordination of glucose testing, nutrition delivery, and insulin administration, should be integrated into your protocols, and order sets. For noncritical care areas, the minimal frequency for blood glucose monitoring for patients who are eating is before meals and at bedtime. For the patient designated nothing by mouth (NPO) or the patient on continuous tube feeding, the type of nutritional/correction insulin used should drive the minimum frequency (every 4‐6 hours if rapid acting analog insulins [RAA‐I] are used, and every 6 hours if regular insulin is used). Directions for administering scheduled RAA‐I immediately before or immediately after nutrition delivery should be incorporated into protocols, order sets, and medication administration records. Unfortunately, having this guidance in the order sets and protocols does not automatically translate into its being carried out in the real world. Wide variability in the coordination of glucose monitoring, nutritional delivery, and insulin administration is common, so monitoring the process to make sure the protocol is followed is important.

Obtaining a glucosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level is important in gauging how well the patient's outpatient regimen is maintaining glycemic control, distinguishing stress hyperglycemia from established diabetes, and guiding the inpatient approach to glycemic control. ADA guidelines2, 3 endorse obtaining HbA1c levels of inpatients if these levels are not already available from the month prior to admission.

Establish a Target Range for Blood Glucose in NonCritical Care Areas

It is important to adopt a glycemic target that is institution‐wide, for critical care areas and noncritical care areas alike. Your glycemic target need not be identical to the ADA/AACE glycemic targets, but should be similar to them.

Examples of institutional glycemic targets for noncritical care areas:

-

Preprandial target 90‐130 mg/dL, maximum random glucose 180 mg/dL (ADA/AACE consensus target)

-

90‐150 mg/dL (a target used in some hospitals)

-

Preprandial target 90‐130 mg/dL for most patients, 100‐150 mg/dL if there are hypoglycemia risk factors, and 180 mg/dL if comfort‐care or end‐of‐life care (a more refined target, allowing for customization based on patient characteristics).

Your multidisciplinary glycemic control steering committee should pick the glycemic target it can most successfully implement and disseminate. It is fine to start with a conservative target and then ratchet down the goals as the environment becomes more accepting of the concept of tighter control of blood glucose in the hospital.

Although the choice of glycemic target is somewhat arbitrary, establishing an institutional glycemic target is critical to motivate clinical action. Your committee should design interventions, for instances when a patient's glycemic target is consistently not being met, including an assignment of responsibility.

Prompt Clinicians to Consider Discontinuing Oral Agents

Oral antihyperglycemic agents, in general, are difficult to quickly titrate to effect, and have side effects that limit their use in the hospital. In contrast, insulin acts rapidly and can be used in virtually all patients and clinical situations, making it the treatment of choice for treatment of hyperglycemia in the hospital.3, 11, 12 In certain circumstances, it may be entirely appropriate to continue a well‐controlled patient on his or her prior outpatient oral regimen. It is often also reasonable to resume oral agents in some patients when preparing for hospital discharge.

Incorporate Nutritional Management

Because diet is so integral to the management of diabetes and hyperglycemia, diet orders should be embedded in all diabetes or insulin‐related order sets. Diets with the same amount of carbohydrate with each meal should be the default rule for patients with diabetes. Nutritionist consultation should be considered and easy to access for patients with malnutrition, obesity, and other common conditions of the inpatient with diabetes.

Access Diabetes Education and Appropriate Consultation

Diabetes education should be offered to all hyperglycemic patients with normal mental status, complete with written materials, a listing of community resources, and survival skills. Consultation with physicians in internal medicine or endocrinology for difficult‐to‐control cases, or for cases in which the primary physician of record is not familiar with (or not adherent to) principles of inpatient glycemic management, should be very easy to obtain, or perhaps mandated, depending on your institution‐specific environment.

Prescribe Physiologic (Basal‐Nutritional‐Correction Dose) Insulin Regimens

Physiologic insulin use is the backbone of the recommended best practice for diabetes and hyperglycemia management in the hospital. The principles of such regimens are summarized elsewhere in this supplement.12 These principles will not be reiterated in detail here, but the major concepts that should be integrated into the protocols and order sets will be highlighted.

Choose a Total Daily Dose

Clinicians need guidance on how much subcutaneous insulin they should give a patient. These doses are well known from clinical experience and the published literature. The fear of hypoglycemia usually results in substantial underdosing of insulin, or total avoidance of scheduled insulin on admission. Your team should provide guidance for how much insulin to start a patient on when it is unclear from past experience how much insulin the patient needs. Waiting a few days to see how much insulin is required via sliding‐scale‐only regimens is a bad practice that should be discouraged for patients whose glucose values are substantially above the glycemic target. The total daily dose (TDD) can be estimated in several different ways (as demonstrated in Appendix 1 and 2), and protocols should make this step very clear for clinicians. Providing a specific location on the order set to declare the TDD may help ensure this step gets done more reliably. Some institutions with computer physician order entry (CPOE) provide assistance with calculating the TDD and the allocation of basal and nutritional components, based on data the ordering physician inputs into the system.

Select and Dose a Basal Insulin

Your protocol should describe how the TDD should be divided between basal and nutritional insulin. We generally recommend 50% of the TDD be given as basal insulin, with the other 50% administered on a scheduled basis to cover glycemic excursions from nutritional intake. The 50/50 rule is simple and generally works well, and should be widely promoted. However, there are exceptions to this rule that should be incorporated into your full protocol and educational programs. The order set should have separate steps for ordering basal insulin, nutritional insulin, and correction insulin. The advantage to providing these insulin components separately is that it allows them to be independently manipulated (eg, if a patient is unable to tolerate a meal, nutritional insulin is held, but basal insulin and correction insulin are continued).

The SHM GCTF specifically endorses long acting insulin (glargine and detemir) as the preferred basal insulin in the hospital setting, thus discouraging the use of neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin and fixed combination insulin formulations (Table 2). In the absence of randomized controlled trials demonstrating superiority of the glargine or detemir to NPH insulin in the hospital, this endorsement deserves some further explanation. Although we believe that correctly dosed NPH containing insulin regimens can attain effective and safe glycemic control in the hospital setting, it is more difficult to standardize their use and adjust for fluctuations in nutritional intake. Glargine and detemir have much less pronounced spikes in their effect than NPH, rendering them relatively peakless in comparison. This pharmacokinetic profile allows for continued dosing with minimal or no correction when nutrition intake is variable, and allow for consistent reinforcement of the basal‐nutritional‐correction insulin concept.

| Nutritional situation | Necessary insulin components | Preferred regimen* |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| NPO (or clear liquids) | Basal insulin: 50% of TDD. Nutritional insulin: None. | Basal insulin: glargine given once daily or detemir given twice daily. Nutritional insulin: None. Correctional insulin: Regular insulin q 6 hours or RAA insulin q 4 hours. Other comments: Dextrose infusion (e.g., D5 containing solution at 75‐150 cc/hour) recommended when nutrition is held. An IV insulin infusion is preferred for management of prolonged fasts or fasting type 1 diabetes patients. |

| Eating meals | Basal insulin: 50% of TDD. Nutritional insulin: 50% of TDD, divided equally before each meal. | Basal insulin: glargine given once daily or detemir given twice daily. Nutritional insulin: RAA insulin with meals. Correctional insulin: RAA insulin q AC and HS (reduced dose at HS). |

| Bolus tube feeds | Basal insulin: 40% of TDD. Nutritional insulin: 60% of the TDD, divided equally before each bolus feed. | Basal insulin: glargine given once daily or detemir given twice daily. Nutritional insulin: RAA insulin with each bolus. Correctional insulin: RAA insulin with each bolus. |

| Continuous tube feeds | Basal insulin: 40% (conservative) of TDD. Nutritional insulin: 60% of the TDD in divided doses. | Basal insulin: glargine given once daily or detemir given twice daily. Nutritional insulin: RAA insulin q 4 hours or regular insulin q 6 hours. Correctional insulin: Should match nutritional insulin choice. |

| Parenteral nutrition | Insulin is usually given parenterally, with the nutrition | Initially, a separate insulin drip allows for accurate dose‐finding. Then, 80% of amount determined as TDD using drip is added to subsequent TPN bags as regular insulin. Use correctional subcutaneous insulin doses cautiously, in addition. |

There are some caveats to this general recommendation. First, patients who are well controlled on home regimens with NPH basal insulin can (and sometimes should) stay on the regimen that has worked well for them. However, extra vigilance in reducing the dose for reductions in nutrition is required, because NPH is generally used to cover both nutritional and basal requirements. Second, extensive experience with glargine and detemir are not available in obstetric populations. They are not U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for use in pregnant patients and formally carry a Class C rating, whereas NPH insulin has been used safely in obstetric populations for decades. Third, the insulin regimen used as an inpatient is not necessarily the preferred regimen to prescribe at discharge: cost, patient preferences, HbA1c level, and other factors should be considered in making this choice.

Select and Dose a Nutritional (Prandial) Insulin

The step for ordering nutritional insulin should assist the clinician in matching the insulin to the type of nutrition that the patient is receiving. For example, rapid‐acting insulin analogs are preferred over regular insulin in the eating patient, in view of their more physiologic profile, which averts the insulin stacking that can occur with regular insulin. If regular insulin is used as the preferred institutional choice for eating patients, the lunchtime dose should be reduced or eliminated altogether, to eliminate insulin stacking.

Table 2 outlines the SHM GCTF preferred regimens for different nutritional situations.

There should be a standing order for nutritional insulin to be held when nutrition is interrupted, whether intentional or unintentional. Patients with interrupted tube feedings could have standing orders for a dextrose infusion to replace the tube feeding carbohydrate load and prevent hypoglycemia. Ideally, there should also be a standing order allowing for real‐time management of the patient with uncertain nutritional intake. For example, when a patient's premeal assessment reveals that she may not tolerate the meal, the patient should be allowed to attempt to eat, and then the nutritional insulin should be given after the meal, in proportion to the amount of food that was eaten. This type of order will require significant nursing education and process redesign in many hospitals, but is essential for matching nutritional insulin to actual intake.

Add Correction Insulin

There is no convincing evidence for the benefit of correction (sliding‐scale) insulin in the inpatient setting, although a randomized trial demonstrating the superiority of basal/nutritional insulin regimens to sliding‐scale only regimens did incorporate a correction insulin scale as an adjunct to the superior basal/nutritional regimen.4 The SHM GCTF again emphasizes that control of hyperglycemia should be proactive and anticipatory of insulin needs, rather than reactive to hyperglycemia. Nonetheless, unexpected hyperglycemic excursions are common, and the use of correction insulin remains a pervasive and arguably logical practice. If correction insulin is used, it should be ordered as a separate step after considering basal and nutrition insulin needs. The doses of scheduled insulin should be adjusted regularly if correction insulin is consistently being required. Ideally, the prescriber should choose a preformatted corrective insulin scale, based on the patient's insulin sensitivity (Appendix 2). There should be a prompt to use the same type of insulin that is being used for nutritional insulin, and there should be instructions that this insulin is given in addition to the basal and nutritional insulin to correct for hyperglycemia. Nocturnal correction‐dose scales should be reduced in the eating patient.

Even after limiting insulin regimens to those in Table 2, multidisciplinary glycemic control teams are still left with several options within these SHM‐preferred regimens. We recommend that your team choose a single, institutionally‐preferred basal‐nutritional‐correction insulin combination for each situation.

Choosing one preferred option for these situations is advantageous because:

-

You can communicate preferred regimens more simply and succinctly to all staff.

-

You eliminate all inappropriate choices for insulin regimens for that situation, as well as some other less preferred, but acceptable choices.

-

You can encourage regimens that are most economical (by promoting the insulin regimens that reflect your hospital formulary choices).

-

Staff members can become very familiar with a few regimens, instead of being confused by a multitude of them. They can identify variations from your preferred choices and target these patients for extra scrutiny and actions should they fail to meet glycemic targets.

Although virtually every institution can provide specific guidance on insulin management in a protocol, there are tradeoffs inherent in how restrictive you can be in pushing these preferred choices in your order sets. Should you eliminate alternate basal or nutritional insulin choices from your order sets? As you integrate more and more of your preferred algorithm and regimens into your order set, you will gain incremental improvement in the standardization of inpatient insulin management. However, you reduce not only variability in ordering, but also the choices available to your prescribers and patients, and in effect you are pushing the providers to use an insulin regimen that often differs from the patient's outpatient regimen. If your institution is not yet ready to go with a single preferred insulin, simply listing your preferred insulin first with the annotation preferred can be enough to increase the use of the preferred insulin.

We endorse building the most protocol‐driven, proscriptive, insulin order set that the Glycemic Control Steering Committee believes their medical staff will accept. There are some caveats to this endorsement. First, there must be extra efforts on the backend of the admission, to ensure that the antihyperglycemic regimen is tailored to the unique needs of the patient (this is discussed further below). Second, a protocol‐driven approach is not a substitute for a good educational program for health care providers or well‐informed clinical judgment. Education should reinforce major concepts driving the protocol and should also highlight exceptions to the rule. Variance from the protocol endorsed choices should be allowed (and even encouraged) when the variance is driven by patient factors (as opposed to provider whim). Learning from this variance is a key concept in refining protocols. Education ideally should not be limited to only protocol‐endorsed choices, as staff should be familiar with the full range of antihyperglycemia regimens seen in inpatient and outpatient settings.

Special Situations

Most of the preferred regimens for different situations are outlined in Table 2 in a straightforward manner, and can be depicted in your protocols and order sets in the same way. Some conditions have enough complexity, however, that you will have difficulty placing all of the details into your one‐page protocol and order set. Details should be placed on your more detailed protocol, and educational programs should include the topics outlined below. Although insulin infusion is often the option that would provide the most reliable and expedient control of hyperglycemia in these special situations, it is an option not available in many noncritical care settings. Therefore, the discussion is limited to subcutaneous insulin control regimens.

Patient on Continuous Tube Feeding

The SHM GCTF endorses glargine or detemir as the basal insulin of choice for this setting. The nutritional and correction insulin of choice is either an RAA‐I every 4 hours (q4h), or regular insulin every 6 hours (q6h). We endorse this choice because it retains the basal‐nutritional‐correction dose concept, generally allows for continued basal insulin use if the tube feedings become interrupted, and is amenable to building a consistent institutional protocol.

There are some important caveats to this recommendation. First, realize that almost any regimen that provides a stable insulin supply would be acceptable, and many institutions will use glargine or detemir to cover both basal and nutritional needs. The downside to using large boluses of long‐acting insulin in this clinical situation is that any unexpected interruption of the feedings will necessitate prolonged infusions of dextrate 10% solution (D10) to avoid hypoglycemia

Second, because of the glycemic load inherent in tube feedings, maintenance of glycemic control in the setting of enteral feeding may be best managed by providing a higher percentage of the TDD as nutritional insulin. In these cases, ratios of basal to nutritional insulin of 40:60, or even less basal insulin, may be appropriate.

Glucocorticoid Therapy

High‐dose glucocorticoids are strongly associated with increased insulin requirements. The degree of hyperglycemia induced by steroids varies significantly from patient to patient, and the pattern of hyperglycemia will vary depending on the pattern of steroid administration. The general principle to keep in mind is that the hyperglycemia induced by a steroid dose will peak 8‐12 hours after it is given, so insulin regimens to address this should take this effect into account. For example, giving a long‐acting basal insulin like glargine to accommodate the hyperglycemic effect of a steroid bolus given in the morning would be inappropriate because the steroid effect would wane and then disappear overnight, leading to insulin‐induced hypoglycemia. NPH insulin can be ideal in this setting, either by itself, or by layering it on top of an existing regimen.

Another caveat: glucocorticoids exert their predominate effect on insulin sensitivity in muscle (as opposed to the liver), and as a result, have their most notable effect on postprandial glucose. For this reason, the best insulin regimens for this situation may use proportionally less basal insulin and more nutritional insulin. One common regimen calls for keeping the basal insulin dose the same as the preglucocorticoid dose, while escalating the RAA insulin dose at lunch and dinner.

Given the complexities of covering steroid‐induced hyperglycemia and its high prevalence in certain populations (such as transplantation patients and patients undergoing chemotherapy), this would be an excellent area on which to focus expertise. Examples include routine endocrinology consultation, intervention by a special glycemic control team, or incorporating routine glucose monitoring and triggers for initiating insulin infusion into the protocols for chemotherapy and transplantation patients.

Regiment the Management of Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia is defined by the ADA as a blood glucose of 70 mg/dL or less, based on the physiologic changes that can occur at this glucose level, even in subjectively asymptomatic patients.3 Protocols for management of hypoglycemia should be linked to your diabetes/hyperglycemia protocols. There are many hypoglycemia protocols available for review in the SHM Glycemic Control Resource Room and Glycemic Control Implementation Guide.10 Some common themes for effective implementation stand out. First, the protocols need to walk the balance between simplicity of use, and the need to provide instructions that will provide guidance in a variety of patient situations. Second, the protocols need to be nurse driven, so that nurses can initiate treatment without waiting for a physician order. Third, education and instruction regarding recognition of risk factors, and avoidance of hypoglycemia are needed to support a successful protocol. Importantly, any hypoglycemic event should lead to a reconsideration of the current anti‐hyperglycemic regimen so that future events can be prevented.

Plan for Discharge and Provide Guidance for the Transition

Your institution should have policies and procedures outlining all the steps needed to complete the important transition out of the hospital. At a minimum, this planning should include adequate education (including a learner assessment), appropriate follow‐up, referral to community resources, and a discharge glycemic control regimen that is tailored to the educational, financial, and motivational profile of a patient. The more your inpatient insulin management is driven by protocol, the more likely it is the patient will be on an inpatient treatment plan that differs from their outpatient regimen; therefore, it is even more important to plan this transition carefully and reliably.

Communicating the accurate hyperglycemia related diagnosis and related problems to the primary care provider is important for good care, perhaps even more so for patients who had hyperglycemia while hospitalized without a prior diagnosis of diabetes. Some centers place a prompt for hyperglycemia related diagnosis in the order set and/or discharge paperwork, to remind the clinician to convey the diagnosis to the primary provider, and to encourage more complete documentation. Improved documentation can also improve the business case for glycemic control, along with other strategies outlined elsewhere in this supplement.13

Transitions in care (including transitions out of the hospital and off of infusion insulin) are discussed in more detail14, 15 elsewhere in this supplement. The principles outlined in these references should be incorporated into your institutional protocol. Briefly, not all patients require or are capable of intensive basal‐bolus regimens upon discharge. The HbA1c can be very valuable in arriving at the optimal outpatient regimen.14 The capacities and preferences of the patient and the context of his or her outpatient care environment (including the preferences of the primary care provider) must be taken into consideration as an outpatient management program is planned.

PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER: MAKE SURE YOUR PROTOCOL/ORDER SET IS EASY TO USE AND WIDELY UTILIZED

When standardizing hospital management of diabetes and hyperglycemia, we recommend building the full protocol first, then crystallizing the protocol into a one‐page summary that can be widely disseminated. The protocol guidance is then incorporated into the order set and nursing medical administration record (MAR). Again, we recommend the most proscriptive and protocol‐driven order set feasible within the constraints of medical staff support. The example order set in Appendix 2 illustrates this approach along with other desirable features:

-

Check‐box simplicity on when to order appropriate glucose monitoring.

-

Prompt for the proper hyperglycemia‐related diagnosis.

-

Prompts to document diagnosis and to order HbA1c level.

-

Use of encouraged insulin terminology: basal, prandial (or nutritional), and correction. Language is a powerful thing, and just getting staff to use these terms goes a long way toward the more physiologic prescribing of insulin.

-

Statement/reminder of a glycemic goal.

-

Prompts and contact information for appropriate consultation.

-

Elimination of unapproved abbreviations (such as U for units).

-

Stating both generic and brand names of insulin preparations.

-

Important timing cues for administration of insulin.

-

Several correction‐dose scales suitable for different insulin sensitivities. One size does NOT fit all.

-

Incorporation of a simple hypoglycemia protocol into the order set.

-

Insulin dosing guidelines available at the point of care (in this case, on the back of the order set).

Additional nursing‐specific cues (such as an admonition to never mix glargine insulin with other types of insulin) can also be included in the MAR whenever glargine is ordered.

Once you have protocols and order sets to guide providers, you need to assure that they are used for the majority of hyperglycemic patients. Educational programs should introduce your interventions and the rationale for them. In order to make your method the default method of care, your team should survey all preprinted or CPOE insulin order sets of your institution. A review of postoperative, transfer, and admission order sets that all services use may reveal a half‐dozen or more embedded sliding‐scale insulin order sets that should be removed, with prompts to use the standardized insulin order set being placed in their stead.

Computerized order sets present both challenges and opportunities. Wording limitations and the scrolling nature can make concepts less clear, yet there is a capability for incorporating a hierarchical structure that allows for guiding the user through a more algorithmic approach. There is also a capacity to provide assistance with dosing calculations that do not exist in the paper world. Education remains of key importance for both methods.

MONITOR THE USE AND EFFECTIVENESS OF YOUR PROTOCOLS AND ORDER SETS

Creating and implementing protocols, order sets, and other tools is not the end of the journey to improve care. It is important to monitor order set utilization, insulin use patterns, and parameters measuring glycemic control and hypoglycemia, as outlined in more detail in another article in this supplement.16 In addition to summary data every month or so, we recommend daily reports that spur action in near real time. Triggers such as uncontrolled hyperglycemia, markedly elevated HbA1c levels, and nonphysiologic insulin regimens should initiate consultation, extra diabetes education, or referral to a glucose control team. If appropriate consultation is not readily available, the glycemic control steering group should lobby the administration to bolster this capability. Qualitative feedback from the frontline caregivers, as well as this quantitative data, can assist the local glycemic control champions in designing even more effective protocols, order sets, focused educational efforts, and concurrent mitigation of suboptimal care.

CONCLUSION

Diabetes, hyperglycemia, and iatrogenic hypoglycemia are common and important conditions affecting the noncritically ill inpatient. Interventional trials to validate the recommended noncritical care unit glycemic targets are needed. Although there is a growing consensus on best practices to care for these patients, numerous barriers and the complexity of caring for inpatients hamper the reliability of best practice delivery. Institutional protocols and protocol driven subcutaneous insulin orders, when implemented with the strategies outlined here, can be the key to delivering these best practices more reliably.

Appendix

Inpatient glycemic control and hypoglycemia are issues with well deserved increased attention in recent years. Prominent guidelines and technical reviews have been published,13 and a recent, randomized controlled trial demonstrated the superiority of basal bolus insulin regimens compared to sliding‐scale regimens.4 Effective glycemic control for inpatients has remained elusive in most medical centers. Recent reports57 detail clinical inertia and the continued widespread use of sliding‐scale subcutaneous insulin regimens, as opposed to the anticipatory, physiologic basal‐nutrition‐correction dose insulin regimens endorsed by these reviews.

Inpatient glycemic control faces a number of barriers, including fears of inducing hypoglycemia, uneven knowledge and training among staff, and competing institutional and patient priorities. These barriers occur in the background of an inherently complex inpatient environment that poses unique challenges in maintaining safe glycemic control. Patients frequently move across a variety of care teams and geographic locations during a single inpatient stay, giving rise to multiple opportunities for failed communication, incomplete handoffs, and inconsistent treatment. In addition, insulin requirements may change dramatically due to variations in the stress of illness, exposure to medications that effect glucose levels, and varied forms of nutritional intake with frequent interruption. Although insulin is recognized as one of the medications most likely to be associated with adverse events in the hospital, many hospitals do not have protocols or order sets in place to standardize its use.

A Call to Action consensus conference,8, 9 hosted by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA), brought together many thought leaders and organizations, including representation from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), to address these barriers and to outline components necessary for successful implementation of a program to improve inpatient glycemic control in the face of these difficulties. Institutional insulin management protocols and standardized insulin order sets (supported by appropriate educational efforts) were identified as key interventions. It may be tempting to quickly deploy a generic insulin order set in an effort to improve care. This often results in mediocre results, due to inadequate incorporation of standardization and guidance into the order set and other documentation tools, and uneven use of the order set.

The SHM Glycemic Control Task Force (GCTF) recommends the following steps for developing and implementing successful protocols and order sets addressing the needs of the noncritical care inpatient with diabetes/hyperglycemia.

-

Form a steering committee for this work, and assess the current processes of care.

-

Identify best practices and preferred regimens to manage diabetes and hyperglycemia in the hospital.

-

Integrate best practices and preferred institutional choices into an inpatient glycemic control protocol. Crystallize your protocol into a one page summary.

-

Place guidance from your protocol into the flow of work, by integrating it into standardized subcutaneous insulin order sets and other documentation and treatment tools.

-

Monitor the use of your order sets and protocol. Intervene actively on nonadherents to your protocol and those with poor glycemic control, and revise your protocol/order sets as needed.

IDENTIFYING AND INCORPORATING KEY CONCEPTS AND BEST PRACTICES

A protocol is a document that endorses specific monitoring and treatment strategies in a given institution. This potentially extensive document should provide guidance for transitions, special situations (like steroids and total parenteral nutrition [TPN]) and should outline preferred insulin regimens for all of the most common nutritional situations. One of the most difficult parts of creating a protocol is the assimilation of all of the important information on which to base decisions. Your protocol and order set will be promoting a set of clinical practices. Fortunately, the current best practice for noncritical care hyperglycemic patients has been summarized by several authoritative sources,13, 811 including references from the SHM Glycemic Task Force published in this supplement.4, 12

Table 1 summarizes the key concepts that should be emphasized in a protocol for subcutaneous insulin management in the hospital. We recommend embedding guidance from your protocol into order sets, the medication administration record, and educational materials. Although the details contained in a protocol and order set might vary from one institution to another, the key concepts should not. The remainder of this article provides practical information about how these concepts and guidance for how preferred insulin regimens should be included in these tools. Appendices 1 and 2 give examples of an institutional one‐page summary protocol and subcutaneous insulin order set, respectively.

| 1. Establish a target range for blood glucose levels. |

| 2. Standardize monitoring of glucose levels and assessment of long‐term control (HbA1c). |