User login

The Official Newspaper of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery

Transplantation palliative care: The time is ripe

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients

What does palliative care mean for the person (and family) awaiting transplantation? For the cirrhotic patient with cachexia, ascites, and encephalopathy, it means access to the services of a team trained in the management of these symptoms. Palliative care teams can also provide psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families who are intimidated by the complex navigation of the health care system and the existential threat that end-stage organ failure presents to them. Skilled palliative care and services can be the difference between failing and extended life with a higher quality of life for these very sick patients

Resuscitation of a patient, whether through restoration of organ function or interdicting the progression of disease, begins with resuscitation of hope. Nothing achieves this more quickly than amelioration of burdensome symptoms for the patient and family.

The barriers for transplant surgeons and teams referring and incorporating palliative care services in their practices are multiple and profound. The unique dilemma facing the transplant team is to balance the treatment of the failing organ, the treatment of the patient (and family and friends), and the best use of the graft, a precious gift of society.

Palliative surgery has been defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with noncurable disease without causing premature death. The very success of transplantation over the past 3 decades has obscured our memory of transplantation as a type of palliative surgery. It is a well-known axiom of reconstructive surgery that the reconstructed site should be compared to what was there, not to “normal.” Even in the current era of improved immunosuppression and posttransplant support services, one could hardly describe even a successful transplant patient’s experience as “normal.” These patients’ lives may be extended and/or enhanced but they need palliative care before, during, and after transplantation. The growing availability of trained palliative care clinicians and teams, the increased familiarity of palliative and end-of-life care to surgical residents and fellows, and quality metrics measuring palliative care outcomes will provide reassurance and guidance to address reservations about the convergence of the two seemingly opposite realities.

A modest proposal

We propose that palliative care be presented to the entire spectrum of transplantation care: on the ward, in the ICU, and after transplantation. More specific “triggers” for palliative care for referral of transplant patients should be identified. Wentlandt et al.4 have described a promising model for an ambulatory clinic, which provides early, integrated palliative care to patients awaiting and receiving organ transplantation. In addition, we propose an application for grant funding for a conference and eventual formation of a work group of transplant surgeons and team members, palliative care clinicians, and patient/families who have experienced one of the aspects of the transplant spectrum. We await the subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine of a transplant surgeon. Outside of transplantation, every other surgical specialty in the United States has diplomates certified in hospice and palliative medicine. We await the benefits that will accrue from research about the merging of these fields.

1. Molmenti EP, Dunn GP: Transplantation and palliative care: The convergence of two seemingly opposite realities. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:373-82.

2. Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

3. Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Smith JH, and Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant patients: structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44(4):508-19.

4. Wentlandt, K., Dall’Osto, A., Freeman, N., Le, L. W., Kaya, E., Ross, H., Singer, L. G., Abbey, S., Clarke, H. and Zimmermann, C. (2016), The Transplant Palliative Care Clinic: An early palliative care model for patients in a transplant program. Clin Transplant. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12838.

Dr. Azoulay is a transplantation specialist of Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, and the University of Paris. Dr. Dunn is medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot, and vice-chair of the ACS Committee on Surgical Palliative Care.

Durvalumab combos beat monotherapy for unresectable stage 3 NSCLC

Both combinations – durvalumab plus either the anti-CD73 monoclonal antibody oleclumab or the anti-NKG2A mAb monalizumab – also numerically improved objective response rate. “Safety profiles were consistent across arms and no new safety signals were identified,” said Alexandre Martinez-Marti, MD, the lead investigator on the phase 2 trial, dubbed COAST, which he presented (abstract LBA42) at the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress on Sept. 17.

“These data support further evaluations of these combinations,” said Dr. Martinez-Marti, also a thoracic medical oncologist at the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona.

Durvalumab is already established as a standard of care option for patients with unresectable stage 3 NSCLC who don’t progress after concurrent chemoradiation. There’s been preliminary data suggesting the benefits might be greater with oleclumab or monalizumab, so the study team looked into the issue.

They randomized 66 patients with unresectable stage 3 NSCLC and no progression after chemoradiotherapy to durvalumab 1,500 mg IV every 4 weeks; 59 others to durvalumab at the same dosage plus oleclumab 3,000 mg IV every 2 weeks for the first two cycles then every 4 weeks, and 61 were randomized to durvalumab plus monalizumab 750 mg IV every 2 weeks.

Patients were treated for up to 12 months, and they started treatment no later than 42 days after completing chemoradiation.

Over a median follow-up of 11.5 months, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.3 months in the durvalumab arm, but 15.1 months with the monalizumab combination (PFS hazard ratio versus durvalumab alone, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85), and not reached in the oleclumab arm (PFS HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.26-0.75).

There were only a few complete responders across the study groups. Partial responses rates were 22.4% of the durvalumab alone arm, 36.7% in the oleclumab group, and 32.3% in the monalizumab arm.

The investigator assessed objective response rate was 25.4% with durvalumab alone, 38.3% in the oleclumab group, and 37.1% with the monalizumab combination. Curves started to separate from durvalumab monotherapy at around 2-4 months.

“Overall, the safety profiles of the two combinations were generally similar to the safety profile of durvalumab alone,” Dr. Martinez-Marti said. The rate of grade 3 or higher treatment-emergent events incidence was 39.4% with durvalumab, 40.7% the oleclumab combination, and 27.9% with monalizumab.

The most common grade 3/4 events were pneumonia (5.9%) and decreased lymphocyte count (3.2%); both were less common with the monalizumab combination.

Combined rates of pneumonitis and radiation pneumonitis of any grade were 21.2% with durvalumab, 28.8% in the oleclumab group, and 21.3% with monalizumab.

The groups were generally well balanced at baseline. The majority of subjects were men, White, and former smokers. Most subjects had stage 3A or 3B disease.

The work was funded by AstraZeneca. The investigators disclosed numerous ties to the company, including Dr. Martinez-Marti, who reported personal fees, travel expenses, and other connections.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

Both combinations – durvalumab plus either the anti-CD73 monoclonal antibody oleclumab or the anti-NKG2A mAb monalizumab – also numerically improved objective response rate. “Safety profiles were consistent across arms and no new safety signals were identified,” said Alexandre Martinez-Marti, MD, the lead investigator on the phase 2 trial, dubbed COAST, which he presented (abstract LBA42) at the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress on Sept. 17.

“These data support further evaluations of these combinations,” said Dr. Martinez-Marti, also a thoracic medical oncologist at the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona.

Durvalumab is already established as a standard of care option for patients with unresectable stage 3 NSCLC who don’t progress after concurrent chemoradiation. There’s been preliminary data suggesting the benefits might be greater with oleclumab or monalizumab, so the study team looked into the issue.

They randomized 66 patients with unresectable stage 3 NSCLC and no progression after chemoradiotherapy to durvalumab 1,500 mg IV every 4 weeks; 59 others to durvalumab at the same dosage plus oleclumab 3,000 mg IV every 2 weeks for the first two cycles then every 4 weeks, and 61 were randomized to durvalumab plus monalizumab 750 mg IV every 2 weeks.

Patients were treated for up to 12 months, and they started treatment no later than 42 days after completing chemoradiation.

Over a median follow-up of 11.5 months, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.3 months in the durvalumab arm, but 15.1 months with the monalizumab combination (PFS hazard ratio versus durvalumab alone, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85), and not reached in the oleclumab arm (PFS HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.26-0.75).

There were only a few complete responders across the study groups. Partial responses rates were 22.4% of the durvalumab alone arm, 36.7% in the oleclumab group, and 32.3% in the monalizumab arm.

The investigator assessed objective response rate was 25.4% with durvalumab alone, 38.3% in the oleclumab group, and 37.1% with the monalizumab combination. Curves started to separate from durvalumab monotherapy at around 2-4 months.

“Overall, the safety profiles of the two combinations were generally similar to the safety profile of durvalumab alone,” Dr. Martinez-Marti said. The rate of grade 3 or higher treatment-emergent events incidence was 39.4% with durvalumab, 40.7% the oleclumab combination, and 27.9% with monalizumab.

The most common grade 3/4 events were pneumonia (5.9%) and decreased lymphocyte count (3.2%); both were less common with the monalizumab combination.

Combined rates of pneumonitis and radiation pneumonitis of any grade were 21.2% with durvalumab, 28.8% in the oleclumab group, and 21.3% with monalizumab.

The groups were generally well balanced at baseline. The majority of subjects were men, White, and former smokers. Most subjects had stage 3A or 3B disease.

The work was funded by AstraZeneca. The investigators disclosed numerous ties to the company, including Dr. Martinez-Marti, who reported personal fees, travel expenses, and other connections.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

Both combinations – durvalumab plus either the anti-CD73 monoclonal antibody oleclumab or the anti-NKG2A mAb monalizumab – also numerically improved objective response rate. “Safety profiles were consistent across arms and no new safety signals were identified,” said Alexandre Martinez-Marti, MD, the lead investigator on the phase 2 trial, dubbed COAST, which he presented (abstract LBA42) at the 2021 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress on Sept. 17.

“These data support further evaluations of these combinations,” said Dr. Martinez-Marti, also a thoracic medical oncologist at the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona.

Durvalumab is already established as a standard of care option for patients with unresectable stage 3 NSCLC who don’t progress after concurrent chemoradiation. There’s been preliminary data suggesting the benefits might be greater with oleclumab or monalizumab, so the study team looked into the issue.

They randomized 66 patients with unresectable stage 3 NSCLC and no progression after chemoradiotherapy to durvalumab 1,500 mg IV every 4 weeks; 59 others to durvalumab at the same dosage plus oleclumab 3,000 mg IV every 2 weeks for the first two cycles then every 4 weeks, and 61 were randomized to durvalumab plus monalizumab 750 mg IV every 2 weeks.

Patients were treated for up to 12 months, and they started treatment no later than 42 days after completing chemoradiation.

Over a median follow-up of 11.5 months, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.3 months in the durvalumab arm, but 15.1 months with the monalizumab combination (PFS hazard ratio versus durvalumab alone, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85), and not reached in the oleclumab arm (PFS HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.26-0.75).

There were only a few complete responders across the study groups. Partial responses rates were 22.4% of the durvalumab alone arm, 36.7% in the oleclumab group, and 32.3% in the monalizumab arm.

The investigator assessed objective response rate was 25.4% with durvalumab alone, 38.3% in the oleclumab group, and 37.1% with the monalizumab combination. Curves started to separate from durvalumab monotherapy at around 2-4 months.

“Overall, the safety profiles of the two combinations were generally similar to the safety profile of durvalumab alone,” Dr. Martinez-Marti said. The rate of grade 3 or higher treatment-emergent events incidence was 39.4% with durvalumab, 40.7% the oleclumab combination, and 27.9% with monalizumab.

The most common grade 3/4 events were pneumonia (5.9%) and decreased lymphocyte count (3.2%); both were less common with the monalizumab combination.

Combined rates of pneumonitis and radiation pneumonitis of any grade were 21.2% with durvalumab, 28.8% in the oleclumab group, and 21.3% with monalizumab.

The groups were generally well balanced at baseline. The majority of subjects were men, White, and former smokers. Most subjects had stage 3A or 3B disease.

The work was funded by AstraZeneca. The investigators disclosed numerous ties to the company, including Dr. Martinez-Marti, who reported personal fees, travel expenses, and other connections.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

FROM ESMO CONGRESS 2021

Mediastinal relapse risk lower with PORT, but no survival benefit

The report was an update on the LungART international clinical trial, which, at the 2020 ESMO meeting, was shown not to improve disease-free survival over the course of 3 years. The update showed that, in addition to the lack of disease-free survival benefit, there was also no difference in metastases, and patients randomized to PORT had higher rates of death and grade 3/4 cardiopulmonary toxicity. The investigators returned this year to expand on another finding from the trial, a 51% reduction in the risk of mediastinal relapse with postoperative radiotherapy. The new analysis suggests there might still be a role for PORT in select patients, perhaps those with heavy nodal involvement, said lead investigator and presenter Cecile Le Pechoux, MD, radiation oncologist at the Gustave Roussy cancer treatment center in Villejuif, France.

For now, “personalized prescription of PORT should be based on prognostic factors of relapse and joint assessment of toxicity and efficacy,” she said.

Study discussant Pilar Garrido, MD, PhD, head of thoracic tumors Ramon y Cajal University Hospital, Madrid, agreed that there might still be a benefit for people with multiple N2 nodal station involvement, but at present, she said, “for me PORT cannot be the standard of care ... given the toxicity and mortality among PORT patients in LungART.”

The trial randomized 501 patients with non–small cell lung cancer with mediastinal involvement to either PORT at 54 Gy over 5.5 weeks or no further treatment following complete resection. Neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy were allowed.

The 3-year mediastinal relapse-free survival was 72.26% in the control arm but 86.06% with PORT (hazard ratio, 0.45; 95% confidence interval, 0.3-0.69).

“There is a significant difference” when it comes to mediastinal relapse, and “patients who have PORT do better. If we look at the location of mediastinal relapse, most [patients] relapse within the initially involved node. This is important information,” Dr. Le Pechoux said.

For left-sided tumors, the most frequent sites of mediastinal relapse were thoracic lymph node stations 7, 4L, and 4R. For right sided tumors, the most frequent stations were 4R, 2R and 7.

Prognostic factors for disease-free survival included quality of resection, extent of mediastinal involvement, and lymph node ratio (involved/explored). Nodal involvement was a significant prognostic factor for overall survival, but PORT was not (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.7-1.4).

Mediastinal involvement with more than two node stations and less than an RO, or microscopically margin-negative resection, increased the risk of relapse.

The work was funded by the French National Cancer Institute, French Health Ministry, Institute Gustave Roussy, and Cancer Research UK. Dr. Pechoux and Dr. Garido disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Roche, Amgen, and other companies.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

The report was an update on the LungART international clinical trial, which, at the 2020 ESMO meeting, was shown not to improve disease-free survival over the course of 3 years. The update showed that, in addition to the lack of disease-free survival benefit, there was also no difference in metastases, and patients randomized to PORT had higher rates of death and grade 3/4 cardiopulmonary toxicity. The investigators returned this year to expand on another finding from the trial, a 51% reduction in the risk of mediastinal relapse with postoperative radiotherapy. The new analysis suggests there might still be a role for PORT in select patients, perhaps those with heavy nodal involvement, said lead investigator and presenter Cecile Le Pechoux, MD, radiation oncologist at the Gustave Roussy cancer treatment center in Villejuif, France.

For now, “personalized prescription of PORT should be based on prognostic factors of relapse and joint assessment of toxicity and efficacy,” she said.

Study discussant Pilar Garrido, MD, PhD, head of thoracic tumors Ramon y Cajal University Hospital, Madrid, agreed that there might still be a benefit for people with multiple N2 nodal station involvement, but at present, she said, “for me PORT cannot be the standard of care ... given the toxicity and mortality among PORT patients in LungART.”

The trial randomized 501 patients with non–small cell lung cancer with mediastinal involvement to either PORT at 54 Gy over 5.5 weeks or no further treatment following complete resection. Neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy were allowed.

The 3-year mediastinal relapse-free survival was 72.26% in the control arm but 86.06% with PORT (hazard ratio, 0.45; 95% confidence interval, 0.3-0.69).

“There is a significant difference” when it comes to mediastinal relapse, and “patients who have PORT do better. If we look at the location of mediastinal relapse, most [patients] relapse within the initially involved node. This is important information,” Dr. Le Pechoux said.

For left-sided tumors, the most frequent sites of mediastinal relapse were thoracic lymph node stations 7, 4L, and 4R. For right sided tumors, the most frequent stations were 4R, 2R and 7.

Prognostic factors for disease-free survival included quality of resection, extent of mediastinal involvement, and lymph node ratio (involved/explored). Nodal involvement was a significant prognostic factor for overall survival, but PORT was not (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.7-1.4).

Mediastinal involvement with more than two node stations and less than an RO, or microscopically margin-negative resection, increased the risk of relapse.

The work was funded by the French National Cancer Institute, French Health Ministry, Institute Gustave Roussy, and Cancer Research UK. Dr. Pechoux and Dr. Garido disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Roche, Amgen, and other companies.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

The report was an update on the LungART international clinical trial, which, at the 2020 ESMO meeting, was shown not to improve disease-free survival over the course of 3 years. The update showed that, in addition to the lack of disease-free survival benefit, there was also no difference in metastases, and patients randomized to PORT had higher rates of death and grade 3/4 cardiopulmonary toxicity. The investigators returned this year to expand on another finding from the trial, a 51% reduction in the risk of mediastinal relapse with postoperative radiotherapy. The new analysis suggests there might still be a role for PORT in select patients, perhaps those with heavy nodal involvement, said lead investigator and presenter Cecile Le Pechoux, MD, radiation oncologist at the Gustave Roussy cancer treatment center in Villejuif, France.

For now, “personalized prescription of PORT should be based on prognostic factors of relapse and joint assessment of toxicity and efficacy,” she said.

Study discussant Pilar Garrido, MD, PhD, head of thoracic tumors Ramon y Cajal University Hospital, Madrid, agreed that there might still be a benefit for people with multiple N2 nodal station involvement, but at present, she said, “for me PORT cannot be the standard of care ... given the toxicity and mortality among PORT patients in LungART.”

The trial randomized 501 patients with non–small cell lung cancer with mediastinal involvement to either PORT at 54 Gy over 5.5 weeks or no further treatment following complete resection. Neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy were allowed.

The 3-year mediastinal relapse-free survival was 72.26% in the control arm but 86.06% with PORT (hazard ratio, 0.45; 95% confidence interval, 0.3-0.69).

“There is a significant difference” when it comes to mediastinal relapse, and “patients who have PORT do better. If we look at the location of mediastinal relapse, most [patients] relapse within the initially involved node. This is important information,” Dr. Le Pechoux said.

For left-sided tumors, the most frequent sites of mediastinal relapse were thoracic lymph node stations 7, 4L, and 4R. For right sided tumors, the most frequent stations were 4R, 2R and 7.

Prognostic factors for disease-free survival included quality of resection, extent of mediastinal involvement, and lymph node ratio (involved/explored). Nodal involvement was a significant prognostic factor for overall survival, but PORT was not (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.7-1.4).

Mediastinal involvement with more than two node stations and less than an RO, or microscopically margin-negative resection, increased the risk of relapse.

The work was funded by the French National Cancer Institute, French Health Ministry, Institute Gustave Roussy, and Cancer Research UK. Dr. Pechoux and Dr. Garido disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Roche, Amgen, and other companies.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

FROM ESMO CONGRESS 2021

Trump scheme for Part B drugs raises red flags

A proposed Trump administration plan for paying for drugs under Medicare Part B has raised red flags for doctors.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced Oct. 25 that it will test paying for Part B drugs by more closely aligning those payments with international rates.

The so-called International Price Index (IPI) model “would test whether increasing competition for private-sector vendors to negotiate drug prices, and aligning Medicare payments for drugs with prices that are paid in foreign countries, improves beneficiary access and quality of care while reducing expenditures,” according to a government fact sheet.

Under the test, private vendors would “procure drugs, distribute them to physicians and hospitals, and take on the responsibility of billing Medicare. Vendors would aggregate purchasing, seek volume-based discounts, and compete for providers’ business, thereby creating competition where none exists today.”

Health care professionals and hospitals in certain geographic areas would receive their Part B drugs under this program, while the rest of the country would continue under the current buy-and-bill system. Eventually, over the 5-year phase-in period, half of the geographic regions would fall under this IPI model.

CMS officials note that the IPI model “would maintain beneficiaries’ choice of provider and treatments and would have meaningful beneficiary protections such as enhanced monitoring and Medicare Beneficiary Ombudsman supports.”

Initially, only single-source drugs and biologics with available international pricing data would be provided under the IPI model, which could be expanded over time to include drugs available via multiple sources.

Currently, Medicare typically pays average sales price (ASP) plus a 6% add-on for drugs under Part B. Under IPI, if the international price is determined to be lower than the ASP, the CMS would reimburse based on a target price derived from an international price index, with the hope that manufacturers would match the international price. The target price would be phased in over a 5-year period.

The plan also calls for an add-on price similar to the current buy-and-bill system; however, the CMS aims to bring the add-on back to 6% rather than the actual 4.3% under the budget sequestration.

Other add-ons are also under consideration, such as paying a fixed amount per encounter or per month as well as a unique payment based on drug class, physician specialty, or physician practice.

Early takes on the proposal were met with skepticism.

The Community Oncology Alliance (COA) said in a statement that it is “concerned that the IPI will either repeat past reform mistakes [such as the Competitive Acquisition Program] or introduce the same cancer treatment access challenges experienced by cancer patients today with pharmacy benefit managers and other middlemen under Medicare Part D.”

“What the administration is proposing is incredibly complex and extremely difficult to comprehend how it would be implemented in the real-world of medical practice,” said Ted Okon, executive director of the COA. “It is also disturbing that the administration is trying to end-run the Congress by forcing a mandatory CMS Innovation Center demonstration that will effectively change Medicare reimbursement, as the sequester cut to Part B drug reimbursement has already done.”

The American College of Rheumatology was more measured in its reaction, noting that any change in policy needs to be thoughtful in its process to ensure that patient care is not adversely affected.

“Efforts to address high costs can sometimes create significant access issues for patients while penalizing doctors for providing quality care,” ACR officials said in a statement. “These proposals include those restructuring reimbursement for Medicare Part B drugs through either flat fee payments or a competitive acquisition program, or allowing utilization management such as step therapy or ‘fail first’ protocols in the Medicare Part B program. It is imperative that policy makers stay focused on the players who control drug prices and not penalize Medicare patients who depend on timely access to needed therapies.”

The American Medical Association raised some concerns as well.

“The administration’s proposal for an International Pricing Index Model for Part B drugs raises a number of questions, and we need to have a greater understanding of the potential impact of the proposal on patients, physicians, and the health care system,” AMA President Barbara McAneny, MD, said in a statement. “We look forward to working constructively with the Administration as it seeks feedback.”

The advanced notice of proposed rulemaking was posted to the Federal Register website on Oct. 25 and is scheduled to be formally published in the publication on Oct. 30. Comments are due Dec. 24. The CMS plans to issue the proposed rule related to this model in the spring of 2019.

A proposed Trump administration plan for paying for drugs under Medicare Part B has raised red flags for doctors.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced Oct. 25 that it will test paying for Part B drugs by more closely aligning those payments with international rates.

The so-called International Price Index (IPI) model “would test whether increasing competition for private-sector vendors to negotiate drug prices, and aligning Medicare payments for drugs with prices that are paid in foreign countries, improves beneficiary access and quality of care while reducing expenditures,” according to a government fact sheet.

Under the test, private vendors would “procure drugs, distribute them to physicians and hospitals, and take on the responsibility of billing Medicare. Vendors would aggregate purchasing, seek volume-based discounts, and compete for providers’ business, thereby creating competition where none exists today.”

Health care professionals and hospitals in certain geographic areas would receive their Part B drugs under this program, while the rest of the country would continue under the current buy-and-bill system. Eventually, over the 5-year phase-in period, half of the geographic regions would fall under this IPI model.

CMS officials note that the IPI model “would maintain beneficiaries’ choice of provider and treatments and would have meaningful beneficiary protections such as enhanced monitoring and Medicare Beneficiary Ombudsman supports.”

Initially, only single-source drugs and biologics with available international pricing data would be provided under the IPI model, which could be expanded over time to include drugs available via multiple sources.

Currently, Medicare typically pays average sales price (ASP) plus a 6% add-on for drugs under Part B. Under IPI, if the international price is determined to be lower than the ASP, the CMS would reimburse based on a target price derived from an international price index, with the hope that manufacturers would match the international price. The target price would be phased in over a 5-year period.

The plan also calls for an add-on price similar to the current buy-and-bill system; however, the CMS aims to bring the add-on back to 6% rather than the actual 4.3% under the budget sequestration.

Other add-ons are also under consideration, such as paying a fixed amount per encounter or per month as well as a unique payment based on drug class, physician specialty, or physician practice.

Early takes on the proposal were met with skepticism.

The Community Oncology Alliance (COA) said in a statement that it is “concerned that the IPI will either repeat past reform mistakes [such as the Competitive Acquisition Program] or introduce the same cancer treatment access challenges experienced by cancer patients today with pharmacy benefit managers and other middlemen under Medicare Part D.”

“What the administration is proposing is incredibly complex and extremely difficult to comprehend how it would be implemented in the real-world of medical practice,” said Ted Okon, executive director of the COA. “It is also disturbing that the administration is trying to end-run the Congress by forcing a mandatory CMS Innovation Center demonstration that will effectively change Medicare reimbursement, as the sequester cut to Part B drug reimbursement has already done.”

The American College of Rheumatology was more measured in its reaction, noting that any change in policy needs to be thoughtful in its process to ensure that patient care is not adversely affected.

“Efforts to address high costs can sometimes create significant access issues for patients while penalizing doctors for providing quality care,” ACR officials said in a statement. “These proposals include those restructuring reimbursement for Medicare Part B drugs through either flat fee payments or a competitive acquisition program, or allowing utilization management such as step therapy or ‘fail first’ protocols in the Medicare Part B program. It is imperative that policy makers stay focused on the players who control drug prices and not penalize Medicare patients who depend on timely access to needed therapies.”

The American Medical Association raised some concerns as well.

“The administration’s proposal for an International Pricing Index Model for Part B drugs raises a number of questions, and we need to have a greater understanding of the potential impact of the proposal on patients, physicians, and the health care system,” AMA President Barbara McAneny, MD, said in a statement. “We look forward to working constructively with the Administration as it seeks feedback.”

The advanced notice of proposed rulemaking was posted to the Federal Register website on Oct. 25 and is scheduled to be formally published in the publication on Oct. 30. Comments are due Dec. 24. The CMS plans to issue the proposed rule related to this model in the spring of 2019.

A proposed Trump administration plan for paying for drugs under Medicare Part B has raised red flags for doctors.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced Oct. 25 that it will test paying for Part B drugs by more closely aligning those payments with international rates.

The so-called International Price Index (IPI) model “would test whether increasing competition for private-sector vendors to negotiate drug prices, and aligning Medicare payments for drugs with prices that are paid in foreign countries, improves beneficiary access and quality of care while reducing expenditures,” according to a government fact sheet.

Under the test, private vendors would “procure drugs, distribute them to physicians and hospitals, and take on the responsibility of billing Medicare. Vendors would aggregate purchasing, seek volume-based discounts, and compete for providers’ business, thereby creating competition where none exists today.”

Health care professionals and hospitals in certain geographic areas would receive their Part B drugs under this program, while the rest of the country would continue under the current buy-and-bill system. Eventually, over the 5-year phase-in period, half of the geographic regions would fall under this IPI model.

CMS officials note that the IPI model “would maintain beneficiaries’ choice of provider and treatments and would have meaningful beneficiary protections such as enhanced monitoring and Medicare Beneficiary Ombudsman supports.”

Initially, only single-source drugs and biologics with available international pricing data would be provided under the IPI model, which could be expanded over time to include drugs available via multiple sources.

Currently, Medicare typically pays average sales price (ASP) plus a 6% add-on for drugs under Part B. Under IPI, if the international price is determined to be lower than the ASP, the CMS would reimburse based on a target price derived from an international price index, with the hope that manufacturers would match the international price. The target price would be phased in over a 5-year period.

The plan also calls for an add-on price similar to the current buy-and-bill system; however, the CMS aims to bring the add-on back to 6% rather than the actual 4.3% under the budget sequestration.

Other add-ons are also under consideration, such as paying a fixed amount per encounter or per month as well as a unique payment based on drug class, physician specialty, or physician practice.

Early takes on the proposal were met with skepticism.

The Community Oncology Alliance (COA) said in a statement that it is “concerned that the IPI will either repeat past reform mistakes [such as the Competitive Acquisition Program] or introduce the same cancer treatment access challenges experienced by cancer patients today with pharmacy benefit managers and other middlemen under Medicare Part D.”

“What the administration is proposing is incredibly complex and extremely difficult to comprehend how it would be implemented in the real-world of medical practice,” said Ted Okon, executive director of the COA. “It is also disturbing that the administration is trying to end-run the Congress by forcing a mandatory CMS Innovation Center demonstration that will effectively change Medicare reimbursement, as the sequester cut to Part B drug reimbursement has already done.”

The American College of Rheumatology was more measured in its reaction, noting that any change in policy needs to be thoughtful in its process to ensure that patient care is not adversely affected.

“Efforts to address high costs can sometimes create significant access issues for patients while penalizing doctors for providing quality care,” ACR officials said in a statement. “These proposals include those restructuring reimbursement for Medicare Part B drugs through either flat fee payments or a competitive acquisition program, or allowing utilization management such as step therapy or ‘fail first’ protocols in the Medicare Part B program. It is imperative that policy makers stay focused on the players who control drug prices and not penalize Medicare patients who depend on timely access to needed therapies.”

The American Medical Association raised some concerns as well.

“The administration’s proposal for an International Pricing Index Model for Part B drugs raises a number of questions, and we need to have a greater understanding of the potential impact of the proposal on patients, physicians, and the health care system,” AMA President Barbara McAneny, MD, said in a statement. “We look forward to working constructively with the Administration as it seeks feedback.”

The advanced notice of proposed rulemaking was posted to the Federal Register website on Oct. 25 and is scheduled to be formally published in the publication on Oct. 30. Comments are due Dec. 24. The CMS plans to issue the proposed rule related to this model in the spring of 2019.

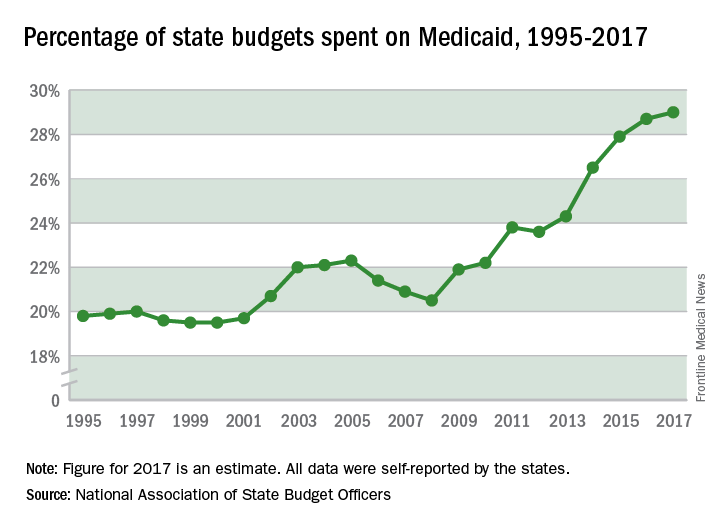

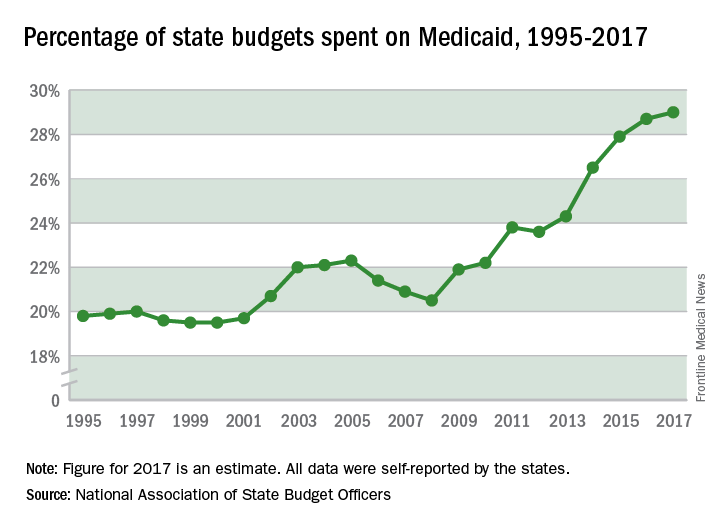

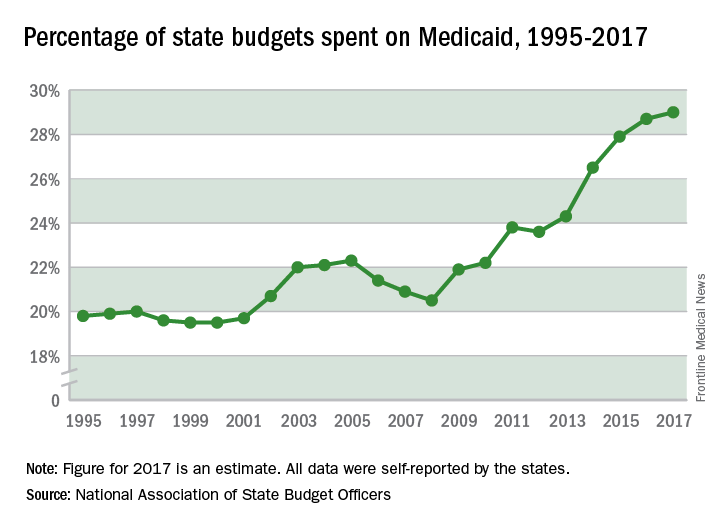

Booming economy helps flatten Medicaid enrollment and limit costs, states report

Medicaid enrollment fell by 0.6% in 2018 – its first drop since 2007 – because of the strong economy and increased efforts in some states to verify eligibility, a new report finds.

But costs continue to go up. Total Medicaid spending rose 4.2% in 2018, same as a year ago, as a result of rising costs for drugs, long-term care, and mental health services, according to the study released Oct. 25 by the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

States expect total Medicaid spending growth to accelerate modestly to 5.3% in 2019 as enrollment increases by about 1%, according to the annual survey of state Medicaid directors.

About 73 million people were enrolled in Medicaid in August, according to a federal report released Wednesday.

Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income Americans, has seen its rolls soar in the past decade – initially as a result of massive job losses during the Great Recession and in recent years when dozens of states expanded eligibility using federal financing provided by the Affordable Care Act. Thirty-three states expanded their programs to cover people with incomes under 138% of the federal poverty level, or an income of about $16,750 for an individual in 2018.

Medicaid spending and enrollment typically rise during economic downturns as more people lose jobs and health benefits. When the economy is humming, Medicaid enrollment flattens as more people get back to work and can get coverage at work or can afford to buy it on their own. The national unemployment rate was 3.7% in September, the lowest since 1969.

The falling unemployment rate is the main reason for the drop in Medicaid enrollment, but some states have reduced their rolls by requiring adults and families to verify their eligibility. Arkansas, for example, has cut thousands of people after instituting new steps to confirm eligibility.

The brightening economic outlook for states has led many to increase benefits to enrollees and payment rates for health providers.

“A total of 19 states expanded or enhanced covered benefits in fiscal 2018 and 24 states plan to add or enhance benefits for the current fiscal year, which for most states started in July,” the Kaiser report said. “The most common benefit enhancements reported were for mental health and substance abuse services. A handful of states reported expansions related to dental services, telehealth, physical or occupational therapies and home visiting services for pregnant women.”

A dozen states increased pay to dentists and 18 states added to primary care doctors’ reimbursements for fiscal year 2019.

Medicaid covers about 20% of U.S. residents and accounts for nearly one-sixth of health care expenditures. Nearly half of enrollees are children.

Overall, the federal government pays about 62% of Medicaid costs with state’s picking up the rest. Poorer states get a higher federal match rate.

Seventeen Republican-controlled states have not expanded Medicaid. For individuals accepted into the program as part of the ACA expansion, the federal government paid the full cost of coverage from 2014 through 2016. It will pay no less than 90% thereafter.

In 2018, the states’ share of spending rose 4.9%. This was the first full year that states were responsible for part of the cost of the expansion. States expect their spending will grow about 3.5% in 2019.

Robin Rudowitz, one of the authors of the study and associate director of the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said the survey found many states were using Medicaid to address the opioid crisis by expanding benefits for substance disorders and also by implementing tougher restrictions on prescriptions.

“Almost every governor wants to do something, and Medicaid is generally a large part of it,” she said.

While the Trump administration’s approval of work requirements for some adults on Medicaid has generated controversy over the past year, the report shows that states are making many other changes to the program, such as increasing benefits and changing how it pays providers to get better value.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Medicaid enrollment fell by 0.6% in 2018 – its first drop since 2007 – because of the strong economy and increased efforts in some states to verify eligibility, a new report finds.

But costs continue to go up. Total Medicaid spending rose 4.2% in 2018, same as a year ago, as a result of rising costs for drugs, long-term care, and mental health services, according to the study released Oct. 25 by the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

States expect total Medicaid spending growth to accelerate modestly to 5.3% in 2019 as enrollment increases by about 1%, according to the annual survey of state Medicaid directors.

About 73 million people were enrolled in Medicaid in August, according to a federal report released Wednesday.

Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income Americans, has seen its rolls soar in the past decade – initially as a result of massive job losses during the Great Recession and in recent years when dozens of states expanded eligibility using federal financing provided by the Affordable Care Act. Thirty-three states expanded their programs to cover people with incomes under 138% of the federal poverty level, or an income of about $16,750 for an individual in 2018.

Medicaid spending and enrollment typically rise during economic downturns as more people lose jobs and health benefits. When the economy is humming, Medicaid enrollment flattens as more people get back to work and can get coverage at work or can afford to buy it on their own. The national unemployment rate was 3.7% in September, the lowest since 1969.

The falling unemployment rate is the main reason for the drop in Medicaid enrollment, but some states have reduced their rolls by requiring adults and families to verify their eligibility. Arkansas, for example, has cut thousands of people after instituting new steps to confirm eligibility.

The brightening economic outlook for states has led many to increase benefits to enrollees and payment rates for health providers.

“A total of 19 states expanded or enhanced covered benefits in fiscal 2018 and 24 states plan to add or enhance benefits for the current fiscal year, which for most states started in July,” the Kaiser report said. “The most common benefit enhancements reported were for mental health and substance abuse services. A handful of states reported expansions related to dental services, telehealth, physical or occupational therapies and home visiting services for pregnant women.”

A dozen states increased pay to dentists and 18 states added to primary care doctors’ reimbursements for fiscal year 2019.

Medicaid covers about 20% of U.S. residents and accounts for nearly one-sixth of health care expenditures. Nearly half of enrollees are children.

Overall, the federal government pays about 62% of Medicaid costs with state’s picking up the rest. Poorer states get a higher federal match rate.

Seventeen Republican-controlled states have not expanded Medicaid. For individuals accepted into the program as part of the ACA expansion, the federal government paid the full cost of coverage from 2014 through 2016. It will pay no less than 90% thereafter.

In 2018, the states’ share of spending rose 4.9%. This was the first full year that states were responsible for part of the cost of the expansion. States expect their spending will grow about 3.5% in 2019.

Robin Rudowitz, one of the authors of the study and associate director of the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said the survey found many states were using Medicaid to address the opioid crisis by expanding benefits for substance disorders and also by implementing tougher restrictions on prescriptions.

“Almost every governor wants to do something, and Medicaid is generally a large part of it,” she said.

While the Trump administration’s approval of work requirements for some adults on Medicaid has generated controversy over the past year, the report shows that states are making many other changes to the program, such as increasing benefits and changing how it pays providers to get better value.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Medicaid enrollment fell by 0.6% in 2018 – its first drop since 2007 – because of the strong economy and increased efforts in some states to verify eligibility, a new report finds.

But costs continue to go up. Total Medicaid spending rose 4.2% in 2018, same as a year ago, as a result of rising costs for drugs, long-term care, and mental health services, according to the study released Oct. 25 by the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

States expect total Medicaid spending growth to accelerate modestly to 5.3% in 2019 as enrollment increases by about 1%, according to the annual survey of state Medicaid directors.

About 73 million people were enrolled in Medicaid in August, according to a federal report released Wednesday.

Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income Americans, has seen its rolls soar in the past decade – initially as a result of massive job losses during the Great Recession and in recent years when dozens of states expanded eligibility using federal financing provided by the Affordable Care Act. Thirty-three states expanded their programs to cover people with incomes under 138% of the federal poverty level, or an income of about $16,750 for an individual in 2018.

Medicaid spending and enrollment typically rise during economic downturns as more people lose jobs and health benefits. When the economy is humming, Medicaid enrollment flattens as more people get back to work and can get coverage at work or can afford to buy it on their own. The national unemployment rate was 3.7% in September, the lowest since 1969.

The falling unemployment rate is the main reason for the drop in Medicaid enrollment, but some states have reduced their rolls by requiring adults and families to verify their eligibility. Arkansas, for example, has cut thousands of people after instituting new steps to confirm eligibility.

The brightening economic outlook for states has led many to increase benefits to enrollees and payment rates for health providers.

“A total of 19 states expanded or enhanced covered benefits in fiscal 2018 and 24 states plan to add or enhance benefits for the current fiscal year, which for most states started in July,” the Kaiser report said. “The most common benefit enhancements reported were for mental health and substance abuse services. A handful of states reported expansions related to dental services, telehealth, physical or occupational therapies and home visiting services for pregnant women.”

A dozen states increased pay to dentists and 18 states added to primary care doctors’ reimbursements for fiscal year 2019.

Medicaid covers about 20% of U.S. residents and accounts for nearly one-sixth of health care expenditures. Nearly half of enrollees are children.

Overall, the federal government pays about 62% of Medicaid costs with state’s picking up the rest. Poorer states get a higher federal match rate.

Seventeen Republican-controlled states have not expanded Medicaid. For individuals accepted into the program as part of the ACA expansion, the federal government paid the full cost of coverage from 2014 through 2016. It will pay no less than 90% thereafter.

In 2018, the states’ share of spending rose 4.9%. This was the first full year that states were responsible for part of the cost of the expansion. States expect their spending will grow about 3.5% in 2019.

Robin Rudowitz, one of the authors of the study and associate director of the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said the survey found many states were using Medicaid to address the opioid crisis by expanding benefits for substance disorders and also by implementing tougher restrictions on prescriptions.

“Almost every governor wants to do something, and Medicaid is generally a large part of it,” she said.

While the Trump administration’s approval of work requirements for some adults on Medicaid has generated controversy over the past year, the report shows that states are making many other changes to the program, such as increasing benefits and changing how it pays providers to get better value.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Restrictive transfusions do not increase long-term CV surgery risk

MUNICH – in a large, randomized trial presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators previously reported that 28 day outcomes were non-inferior with the restrictive approach, but they wanted to look into 6 month results to rule out latent problems, such as sequelae from perioperative organ hypoxia.

The new outcomes from the study, dubbed the Transfusion Requirements in Cardiac Surgery (TRICS) III trial, offer some reassurance at a time when cardiac surgeons are shifting towards more restrictive transfusion policies (N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26.doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808561).

The trial randomized 2,317 patients to red cell transfusions if their hemoglobin concentrations fell below 7.5 g/dL intraoperatively or postoperatively. Another 2,347 were randomized to the liberal approach, with transfusions below 9.5 g/dL in the operating room and ICU, and below 8.5 g/dL outside of the ICU. The arms were well matched, with a mean score of 8 in both groups on the 47-point European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation I score.

At 6 months, 17.4% of patients in the restrictive arm, versus 17.1% in the liberal-threshold group, met the primary composite outcome of death from any cause, myocardial infarction, stroke, or new onset renal failure with dialysis (P = .006 for noninferiority with the restrictive threshold); 6.2% of patients in the restrictive-threshold group, versus 6.4% in the liberal-arm, had died at that point, a statistically insignificant difference.

Also at 6 months, 43.8% of patients in the restrictive-threshold group, versus 42.8% in the liberal arm, met the study’s secondary composite outcome, which included the components of the primary outcome plus hospital readmissions, ED visits, and coronary revascularization. The difference was again statistically insignificant.

The restrictive strategy saved a lot of blood. Just over half of the patients, versus almost three-quarters in the liberal arm, were transfused during their index admissions. When transfused, patients in the restrictive arm received a median of 2 units of red cells; liberal-arm patients received a median of 3 units.

Unexpectedly, patients 75 years and older had a lower risk of poor outcomes with the restrictive strategy, while the liberal strategy was associated with lower risk in younger subjects. The findings “appear to contradict” current practice, “in which a liberal transfusion strategy is used in older patients undergoing cardiac or noncardiac surgery,” said investigators led by C. David Mazer, MD, a professor in the department of anesthesia at the University of Toronto.

“One could hypothesize that older patients may have unacceptable adverse effects related to transfusion (e.g., volume overload and inflammatory and infectious complications) or that there may be age-related differences in the adverse-effect profile of transfusion or anemia. ... Whether transfusion thresholds should differ according to age” needs to be determined, they said.

The participants were a mean of 72 years old, and 35% were women. The majority in both arms underwent coronary artery bypass surgery, valve surgery, or both. Heart transplants were excluded. The trial was conducted in 19 countries, including China and India; results were consistent across study sites.

The work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, among others. Dr. Mazer had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Mazer CD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808561

MUNICH – in a large, randomized trial presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators previously reported that 28 day outcomes were non-inferior with the restrictive approach, but they wanted to look into 6 month results to rule out latent problems, such as sequelae from perioperative organ hypoxia.

The new outcomes from the study, dubbed the Transfusion Requirements in Cardiac Surgery (TRICS) III trial, offer some reassurance at a time when cardiac surgeons are shifting towards more restrictive transfusion policies (N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26.doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808561).

The trial randomized 2,317 patients to red cell transfusions if their hemoglobin concentrations fell below 7.5 g/dL intraoperatively or postoperatively. Another 2,347 were randomized to the liberal approach, with transfusions below 9.5 g/dL in the operating room and ICU, and below 8.5 g/dL outside of the ICU. The arms were well matched, with a mean score of 8 in both groups on the 47-point European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation I score.

At 6 months, 17.4% of patients in the restrictive arm, versus 17.1% in the liberal-threshold group, met the primary composite outcome of death from any cause, myocardial infarction, stroke, or new onset renal failure with dialysis (P = .006 for noninferiority with the restrictive threshold); 6.2% of patients in the restrictive-threshold group, versus 6.4% in the liberal-arm, had died at that point, a statistically insignificant difference.

Also at 6 months, 43.8% of patients in the restrictive-threshold group, versus 42.8% in the liberal arm, met the study’s secondary composite outcome, which included the components of the primary outcome plus hospital readmissions, ED visits, and coronary revascularization. The difference was again statistically insignificant.

The restrictive strategy saved a lot of blood. Just over half of the patients, versus almost three-quarters in the liberal arm, were transfused during their index admissions. When transfused, patients in the restrictive arm received a median of 2 units of red cells; liberal-arm patients received a median of 3 units.

Unexpectedly, patients 75 years and older had a lower risk of poor outcomes with the restrictive strategy, while the liberal strategy was associated with lower risk in younger subjects. The findings “appear to contradict” current practice, “in which a liberal transfusion strategy is used in older patients undergoing cardiac or noncardiac surgery,” said investigators led by C. David Mazer, MD, a professor in the department of anesthesia at the University of Toronto.

“One could hypothesize that older patients may have unacceptable adverse effects related to transfusion (e.g., volume overload and inflammatory and infectious complications) or that there may be age-related differences in the adverse-effect profile of transfusion or anemia. ... Whether transfusion thresholds should differ according to age” needs to be determined, they said.

The participants were a mean of 72 years old, and 35% were women. The majority in both arms underwent coronary artery bypass surgery, valve surgery, or both. Heart transplants were excluded. The trial was conducted in 19 countries, including China and India; results were consistent across study sites.

The work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, among others. Dr. Mazer had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Mazer CD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808561

MUNICH – in a large, randomized trial presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators previously reported that 28 day outcomes were non-inferior with the restrictive approach, but they wanted to look into 6 month results to rule out latent problems, such as sequelae from perioperative organ hypoxia.

The new outcomes from the study, dubbed the Transfusion Requirements in Cardiac Surgery (TRICS) III trial, offer some reassurance at a time when cardiac surgeons are shifting towards more restrictive transfusion policies (N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26.doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808561).

The trial randomized 2,317 patients to red cell transfusions if their hemoglobin concentrations fell below 7.5 g/dL intraoperatively or postoperatively. Another 2,347 were randomized to the liberal approach, with transfusions below 9.5 g/dL in the operating room and ICU, and below 8.5 g/dL outside of the ICU. The arms were well matched, with a mean score of 8 in both groups on the 47-point European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation I score.

At 6 months, 17.4% of patients in the restrictive arm, versus 17.1% in the liberal-threshold group, met the primary composite outcome of death from any cause, myocardial infarction, stroke, or new onset renal failure with dialysis (P = .006 for noninferiority with the restrictive threshold); 6.2% of patients in the restrictive-threshold group, versus 6.4% in the liberal-arm, had died at that point, a statistically insignificant difference.

Also at 6 months, 43.8% of patients in the restrictive-threshold group, versus 42.8% in the liberal arm, met the study’s secondary composite outcome, which included the components of the primary outcome plus hospital readmissions, ED visits, and coronary revascularization. The difference was again statistically insignificant.

The restrictive strategy saved a lot of blood. Just over half of the patients, versus almost three-quarters in the liberal arm, were transfused during their index admissions. When transfused, patients in the restrictive arm received a median of 2 units of red cells; liberal-arm patients received a median of 3 units.

Unexpectedly, patients 75 years and older had a lower risk of poor outcomes with the restrictive strategy, while the liberal strategy was associated with lower risk in younger subjects. The findings “appear to contradict” current practice, “in which a liberal transfusion strategy is used in older patients undergoing cardiac or noncardiac surgery,” said investigators led by C. David Mazer, MD, a professor in the department of anesthesia at the University of Toronto.

“One could hypothesize that older patients may have unacceptable adverse effects related to transfusion (e.g., volume overload and inflammatory and infectious complications) or that there may be age-related differences in the adverse-effect profile of transfusion or anemia. ... Whether transfusion thresholds should differ according to age” needs to be determined, they said.

The participants were a mean of 72 years old, and 35% were women. The majority in both arms underwent coronary artery bypass surgery, valve surgery, or both. Heart transplants were excluded. The trial was conducted in 19 countries, including China and India; results were consistent across study sites.

The work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, among others. Dr. Mazer had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Mazer CD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808561

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: A restrictive transfusion strategy during cardiovascular surgery, versus a more traditional liberal approach, did not increase the risk of poor outcomes at 6 months.

Major finding: At 6 months, 17.4% of patients in the restrictive arm, versus 17.1% in the liberal-threshold group, met the primary composite outcome of death from any cause, myocardial infarction, stroke, or new onset renal failure with dialysis (P = .006 for noninferiority with the restrictive approach).

Study details: Randomized, multicenter trial with over 5,000 surgery patients