User login

PCPC: Get Patients to Unlearn Cognitive Distortions That Sustain Pain

ORLANDO – Patients often create an internal narrative that serves to delay or prevent recovery from chronic pain, which is why cognitive-behavioral therapy should be routinely considered among chronic pain control strategies, an experienced pain clinician said.

“CBT is designed to teach patients to identify maladaptive assumptions, thoughts, ideas, expectations, and attitudes. By teaching patients to shift from self-defeating thought processes to strategies for coping, they can be given the motivation and tools for change,” said Daniel M. Doleys, Ph.D., a psychologist and director of a pain management practice in Birmingham, Ala.

Pain can be a conditioning process that patients reinforce with statements they tell themselves, such as: “I am disabled,” “I cannot function with pain,” and “There is nothing I can do for my pain,” according to Dr. Doleys, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice. These beliefs become self-established truths that might not change without an intervention that involves some form of retraining.

“CBT is an overarching term for a cluster of therapies,” Dr. Doleys said. Of these, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which combines acceptance, mindfulness, and behavior-change strategies to increase psychological flexibility, is one example that is potentially useful in chronic pain patients, he said. Core principles, besides acceptance and heightened consciousness of one’s self within the current set of circumstances, include an emphasis on defining values and setting goals.

On the basis of these goals, patients can define a new narrative that they can use to replace thought processes that hold them back from change.

For some patients, the assertion that conditioned thoughts might be playing a role in sustained pain may come as “a bit of a shock,” Dr. Doleys said. Indeed, he suggested, patients need to understand these concepts and recognize their own motivation for change. In some cases, an unrecognized reward for enduring chronic pain, such as attention from others, can be a subtle but formidable obstacle to change.

“You cannot always know what is reinforcing to a patient,” Dr. Doleys noted. He indicated that even patients might not be aware of factors that contribute to a reluctance to take meaningful steps toward recovery. However, he cautioned that clinicians who never encourage their patients to address the psychological component could have the effect of “absolving patients from responsibility” for taking this step.

Characterizing chronic pain “as an experience, not an event,” Dr. Doleys suggested that one of the principles of CBT overall and mindfulness CBT strategies in particular is to change the orientation to adverse sensory signals. He cited work with animals in which fear conditioning can be unlearned. The data from these studies suggest new learning does not erase fear memories but changes the conditioned response.

There is a lengthening list of strategies, such as biofeedback, mindfulness training, and autogenic therapy, which have been used to help patients adapt to and eventually modify the impact of pain signaling. Dr. Doleys said individual studies of CBT for chronic pain have not been consistently supportive, but a 2013 Cochrane Reviews of CBT consolidating data from multiple studies does support a modest benefit overall. He suggested that CBT might not be a cure for chronic pain but part of a comprehensive strategy aimed at encouraging patients to focus on function and recovery rather than the narrower goal of pain control.

“Treat the patient, not the pain,” Dr. Doleys advised. In helping patients to work toward functional improvements, he suggested that patients must be given realistic expectations and enlisted to participate in their own recovery. CBT might be an important tool in this process.

Dr. Doleys reported financial relationships with Medtronic and Evzio. The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

ORLANDO – Patients often create an internal narrative that serves to delay or prevent recovery from chronic pain, which is why cognitive-behavioral therapy should be routinely considered among chronic pain control strategies, an experienced pain clinician said.

“CBT is designed to teach patients to identify maladaptive assumptions, thoughts, ideas, expectations, and attitudes. By teaching patients to shift from self-defeating thought processes to strategies for coping, they can be given the motivation and tools for change,” said Daniel M. Doleys, Ph.D., a psychologist and director of a pain management practice in Birmingham, Ala.

Pain can be a conditioning process that patients reinforce with statements they tell themselves, such as: “I am disabled,” “I cannot function with pain,” and “There is nothing I can do for my pain,” according to Dr. Doleys, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice. These beliefs become self-established truths that might not change without an intervention that involves some form of retraining.

“CBT is an overarching term for a cluster of therapies,” Dr. Doleys said. Of these, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which combines acceptance, mindfulness, and behavior-change strategies to increase psychological flexibility, is one example that is potentially useful in chronic pain patients, he said. Core principles, besides acceptance and heightened consciousness of one’s self within the current set of circumstances, include an emphasis on defining values and setting goals.

On the basis of these goals, patients can define a new narrative that they can use to replace thought processes that hold them back from change.

For some patients, the assertion that conditioned thoughts might be playing a role in sustained pain may come as “a bit of a shock,” Dr. Doleys said. Indeed, he suggested, patients need to understand these concepts and recognize their own motivation for change. In some cases, an unrecognized reward for enduring chronic pain, such as attention from others, can be a subtle but formidable obstacle to change.

“You cannot always know what is reinforcing to a patient,” Dr. Doleys noted. He indicated that even patients might not be aware of factors that contribute to a reluctance to take meaningful steps toward recovery. However, he cautioned that clinicians who never encourage their patients to address the psychological component could have the effect of “absolving patients from responsibility” for taking this step.

Characterizing chronic pain “as an experience, not an event,” Dr. Doleys suggested that one of the principles of CBT overall and mindfulness CBT strategies in particular is to change the orientation to adverse sensory signals. He cited work with animals in which fear conditioning can be unlearned. The data from these studies suggest new learning does not erase fear memories but changes the conditioned response.

There is a lengthening list of strategies, such as biofeedback, mindfulness training, and autogenic therapy, which have been used to help patients adapt to and eventually modify the impact of pain signaling. Dr. Doleys said individual studies of CBT for chronic pain have not been consistently supportive, but a 2013 Cochrane Reviews of CBT consolidating data from multiple studies does support a modest benefit overall. He suggested that CBT might not be a cure for chronic pain but part of a comprehensive strategy aimed at encouraging patients to focus on function and recovery rather than the narrower goal of pain control.

“Treat the patient, not the pain,” Dr. Doleys advised. In helping patients to work toward functional improvements, he suggested that patients must be given realistic expectations and enlisted to participate in their own recovery. CBT might be an important tool in this process.

Dr. Doleys reported financial relationships with Medtronic and Evzio. The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

ORLANDO – Patients often create an internal narrative that serves to delay or prevent recovery from chronic pain, which is why cognitive-behavioral therapy should be routinely considered among chronic pain control strategies, an experienced pain clinician said.

“CBT is designed to teach patients to identify maladaptive assumptions, thoughts, ideas, expectations, and attitudes. By teaching patients to shift from self-defeating thought processes to strategies for coping, they can be given the motivation and tools for change,” said Daniel M. Doleys, Ph.D., a psychologist and director of a pain management practice in Birmingham, Ala.

Pain can be a conditioning process that patients reinforce with statements they tell themselves, such as: “I am disabled,” “I cannot function with pain,” and “There is nothing I can do for my pain,” according to Dr. Doleys, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice. These beliefs become self-established truths that might not change without an intervention that involves some form of retraining.

“CBT is an overarching term for a cluster of therapies,” Dr. Doleys said. Of these, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which combines acceptance, mindfulness, and behavior-change strategies to increase psychological flexibility, is one example that is potentially useful in chronic pain patients, he said. Core principles, besides acceptance and heightened consciousness of one’s self within the current set of circumstances, include an emphasis on defining values and setting goals.

On the basis of these goals, patients can define a new narrative that they can use to replace thought processes that hold them back from change.

For some patients, the assertion that conditioned thoughts might be playing a role in sustained pain may come as “a bit of a shock,” Dr. Doleys said. Indeed, he suggested, patients need to understand these concepts and recognize their own motivation for change. In some cases, an unrecognized reward for enduring chronic pain, such as attention from others, can be a subtle but formidable obstacle to change.

“You cannot always know what is reinforcing to a patient,” Dr. Doleys noted. He indicated that even patients might not be aware of factors that contribute to a reluctance to take meaningful steps toward recovery. However, he cautioned that clinicians who never encourage their patients to address the psychological component could have the effect of “absolving patients from responsibility” for taking this step.

Characterizing chronic pain “as an experience, not an event,” Dr. Doleys suggested that one of the principles of CBT overall and mindfulness CBT strategies in particular is to change the orientation to adverse sensory signals. He cited work with animals in which fear conditioning can be unlearned. The data from these studies suggest new learning does not erase fear memories but changes the conditioned response.

There is a lengthening list of strategies, such as biofeedback, mindfulness training, and autogenic therapy, which have been used to help patients adapt to and eventually modify the impact of pain signaling. Dr. Doleys said individual studies of CBT for chronic pain have not been consistently supportive, but a 2013 Cochrane Reviews of CBT consolidating data from multiple studies does support a modest benefit overall. He suggested that CBT might not be a cure for chronic pain but part of a comprehensive strategy aimed at encouraging patients to focus on function and recovery rather than the narrower goal of pain control.

“Treat the patient, not the pain,” Dr. Doleys advised. In helping patients to work toward functional improvements, he suggested that patients must be given realistic expectations and enlisted to participate in their own recovery. CBT might be an important tool in this process.

Dr. Doleys reported financial relationships with Medtronic and Evzio. The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

AT THE PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE MEETING

PCPC: Get patients to unlearn cognitive distortions that sustain pain

ORLANDO – Patients often create an internal narrative that serves to delay or prevent recovery from chronic pain, which is why cognitive-behavioral therapy should be routinely considered among chronic pain control strategies, an experienced pain clinician said.

“CBT is designed to teach patients to identify maladaptive assumptions, thoughts, ideas, expectations, and attitudes. By teaching patients to shift from self-defeating thought processes to strategies for coping, they can be given the motivation and tools for change,” said Daniel M. Doleys, Ph.D., a psychologist and director of a pain management practice in Birmingham, Ala.

Pain can be a conditioning process that patients reinforce with statements they tell themselves, such as: “I am disabled,” “I cannot function with pain,” and “There is nothing I can do for my pain,” according to Dr. Doleys, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice. These beliefs become self-established truths that might not change without an intervention that involves some form of retraining.

“CBT is an overarching term for a cluster of therapies,” Dr. Doleys said. Of these, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which combines acceptance, mindfulness, and behavior-change strategies to increase psychological flexibility, is one example that is potentially useful in chronic pain patients, he said. Core principles, besides acceptance and heightened consciousness of one’s self within the current set of circumstances, include an emphasis on defining values and setting goals.

On the basis of these goals, patients can define a new narrative that they can use to replace thought processes that hold them back from change.

For some patients, the assertion that conditioned thoughts might be playing a role in sustained pain may come as “a bit of a shock,” Dr. Doleys said. Indeed, he suggested, patients need to understand these concepts and recognize their own motivation for change. In some cases, an unrecognized reward for enduring chronic pain, such as attention from others, can be a subtle but formidable obstacle to change.

“You cannot always know what is reinforcing to a patient,” Dr. Doleys noted. He indicated that even patients might not be aware of factors that contribute to a reluctance to take meaningful steps toward recovery. However, he cautioned that clinicians who never encourage their patients to address the psychological component could have the effect of “absolving patients from responsibility” for taking this step.

Characterizing chronic pain “as an experience, not an event,” Dr. Doleys suggested that one of the principles of CBT overall and mindfulness CBT strategies in particular is to change the orientation to adverse sensory signals. He cited work with animals in which fear conditioning can be unlearned. The data from these studies suggest new learning does not erase fear memories but changes the conditioned response.

There is a lengthening list of strategies, such as biofeedback, mindfulness training, and autogenic therapy, which have been used to help patients adapt to and eventually modify the impact of pain signaling. Dr. Doleys said individual studies of CBT for chronic pain have not been consistently supportive, but a 2013 Cochrane Reviews of CBT consolidating data from multiple studies does support a modest benefit overall. He suggested that CBT might not be a cure for chronic pain but part of a comprehensive strategy aimed at encouraging patients to focus on function and recovery rather than the narrower goal of pain control.

“Treat the patient, not the pain,” Dr. Doleys advised. In helping patients to work toward functional improvements, he suggested that patients must be given realistic expectations and enlisted to participate in their own recovery. CBT might be an important tool in this process.

Dr. Doleys reported financial relationships with Medtronic and Evzio. The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

ORLANDO – Patients often create an internal narrative that serves to delay or prevent recovery from chronic pain, which is why cognitive-behavioral therapy should be routinely considered among chronic pain control strategies, an experienced pain clinician said.

“CBT is designed to teach patients to identify maladaptive assumptions, thoughts, ideas, expectations, and attitudes. By teaching patients to shift from self-defeating thought processes to strategies for coping, they can be given the motivation and tools for change,” said Daniel M. Doleys, Ph.D., a psychologist and director of a pain management practice in Birmingham, Ala.

Pain can be a conditioning process that patients reinforce with statements they tell themselves, such as: “I am disabled,” “I cannot function with pain,” and “There is nothing I can do for my pain,” according to Dr. Doleys, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice. These beliefs become self-established truths that might not change without an intervention that involves some form of retraining.

“CBT is an overarching term for a cluster of therapies,” Dr. Doleys said. Of these, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which combines acceptance, mindfulness, and behavior-change strategies to increase psychological flexibility, is one example that is potentially useful in chronic pain patients, he said. Core principles, besides acceptance and heightened consciousness of one’s self within the current set of circumstances, include an emphasis on defining values and setting goals.

On the basis of these goals, patients can define a new narrative that they can use to replace thought processes that hold them back from change.

For some patients, the assertion that conditioned thoughts might be playing a role in sustained pain may come as “a bit of a shock,” Dr. Doleys said. Indeed, he suggested, patients need to understand these concepts and recognize their own motivation for change. In some cases, an unrecognized reward for enduring chronic pain, such as attention from others, can be a subtle but formidable obstacle to change.

“You cannot always know what is reinforcing to a patient,” Dr. Doleys noted. He indicated that even patients might not be aware of factors that contribute to a reluctance to take meaningful steps toward recovery. However, he cautioned that clinicians who never encourage their patients to address the psychological component could have the effect of “absolving patients from responsibility” for taking this step.

Characterizing chronic pain “as an experience, not an event,” Dr. Doleys suggested that one of the principles of CBT overall and mindfulness CBT strategies in particular is to change the orientation to adverse sensory signals. He cited work with animals in which fear conditioning can be unlearned. The data from these studies suggest new learning does not erase fear memories but changes the conditioned response.

There is a lengthening list of strategies, such as biofeedback, mindfulness training, and autogenic therapy, which have been used to help patients adapt to and eventually modify the impact of pain signaling. Dr. Doleys said individual studies of CBT for chronic pain have not been consistently supportive, but a 2013 Cochrane Reviews of CBT consolidating data from multiple studies does support a modest benefit overall. He suggested that CBT might not be a cure for chronic pain but part of a comprehensive strategy aimed at encouraging patients to focus on function and recovery rather than the narrower goal of pain control.

“Treat the patient, not the pain,” Dr. Doleys advised. In helping patients to work toward functional improvements, he suggested that patients must be given realistic expectations and enlisted to participate in their own recovery. CBT might be an important tool in this process.

Dr. Doleys reported financial relationships with Medtronic and Evzio. The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

ORLANDO – Patients often create an internal narrative that serves to delay or prevent recovery from chronic pain, which is why cognitive-behavioral therapy should be routinely considered among chronic pain control strategies, an experienced pain clinician said.

“CBT is designed to teach patients to identify maladaptive assumptions, thoughts, ideas, expectations, and attitudes. By teaching patients to shift from self-defeating thought processes to strategies for coping, they can be given the motivation and tools for change,” said Daniel M. Doleys, Ph.D., a psychologist and director of a pain management practice in Birmingham, Ala.

Pain can be a conditioning process that patients reinforce with statements they tell themselves, such as: “I am disabled,” “I cannot function with pain,” and “There is nothing I can do for my pain,” according to Dr. Doleys, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice. These beliefs become self-established truths that might not change without an intervention that involves some form of retraining.

“CBT is an overarching term for a cluster of therapies,” Dr. Doleys said. Of these, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which combines acceptance, mindfulness, and behavior-change strategies to increase psychological flexibility, is one example that is potentially useful in chronic pain patients, he said. Core principles, besides acceptance and heightened consciousness of one’s self within the current set of circumstances, include an emphasis on defining values and setting goals.

On the basis of these goals, patients can define a new narrative that they can use to replace thought processes that hold them back from change.

For some patients, the assertion that conditioned thoughts might be playing a role in sustained pain may come as “a bit of a shock,” Dr. Doleys said. Indeed, he suggested, patients need to understand these concepts and recognize their own motivation for change. In some cases, an unrecognized reward for enduring chronic pain, such as attention from others, can be a subtle but formidable obstacle to change.

“You cannot always know what is reinforcing to a patient,” Dr. Doleys noted. He indicated that even patients might not be aware of factors that contribute to a reluctance to take meaningful steps toward recovery. However, he cautioned that clinicians who never encourage their patients to address the psychological component could have the effect of “absolving patients from responsibility” for taking this step.

Characterizing chronic pain “as an experience, not an event,” Dr. Doleys suggested that one of the principles of CBT overall and mindfulness CBT strategies in particular is to change the orientation to adverse sensory signals. He cited work with animals in which fear conditioning can be unlearned. The data from these studies suggest new learning does not erase fear memories but changes the conditioned response.

There is a lengthening list of strategies, such as biofeedback, mindfulness training, and autogenic therapy, which have been used to help patients adapt to and eventually modify the impact of pain signaling. Dr. Doleys said individual studies of CBT for chronic pain have not been consistently supportive, but a 2013 Cochrane Reviews of CBT consolidating data from multiple studies does support a modest benefit overall. He suggested that CBT might not be a cure for chronic pain but part of a comprehensive strategy aimed at encouraging patients to focus on function and recovery rather than the narrower goal of pain control.

“Treat the patient, not the pain,” Dr. Doleys advised. In helping patients to work toward functional improvements, he suggested that patients must be given realistic expectations and enlisted to participate in their own recovery. CBT might be an important tool in this process.

Dr. Doleys reported financial relationships with Medtronic and Evzio. The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

AT THE PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE MEETING

Key clinical point: Cognitive distortions often develop to sustain chronic pain, creating a hurdle to therapy independent of pain level.

Major finding: Cognitive-behavioral therapy should be considered in helping patients exit a circle of maladaptive reasoning.

Data source: An overview of clinical experience with support from published studies.

Disclosures: Dr. Doleys reported financial relationships with Medtronic and Evzio.

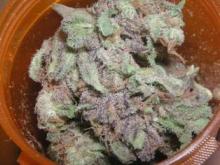

PCPC: Avoid these traps when prescribing medical marijuana

ORLANDO – Good data suggest that marijuana has legitimate medical indications, but smoking the drug is not the appropriate method of delivery, and clinicians without experience with marijuana should consider its many liabilities before issuing a prescription, according to an expert who said he is not antimarijuana and has prescribed this therapy himself.

“Dried cannabis is not a medication in any traditional sense of the word. That does not mean cannabinoids have no legitimate indication as therapeutic agents, but smoking anything for your health is something of an oxymoron,” Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto said at the Pain Care for Primary Care meeting.

Cannabis, distinct from cannabinoids, is defined as the dried leaves of the marijuana plant. According to Dr. Gourlay, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice, the plant has more than 400 compounds, including more than 60 cannabinoids, which are chemicals that act on cannabinoid receptors, primarily in the central nervous system. For physicians wishing to deliver cannabinoids for a medical indication, the problem posed by cannabis is quality control.

“You are being asked to prescribe something for which you have no practical means of titrating the dose,” Dr. Gourlay said. Even ignoring the potential risks of exposing the lungs to a variety of oxidized chemicals with no known therapeutic benefit, the absence of quality control will be problematic if the patient or family members subsequently claim iatrogenic harm.

For recreational use of cannabis, the focus has been on the concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is the cannabinoid most closely associated with euphoric effects. However, the potential medical benefits of marijuana, such as relief of glaucoma symptoms, reduction of chemotherapy-induced nausea, or control of neuropathic pain, are not necessarily related to THC. Well-designed clinical studies aimed at determining which other cannabinoids and at which doses are most relevant for medical use have yet to be performed, Dr. Gourlay said.

For the clinician, legalization of medical marijuana in the absence of reliable data on best practice creates some potential risks. According to Dr. Gourlay, patients who harm themselves or others in an accident attributed to impaired judgment from medical marijuana might pursue legal action against the prescribing physician. The relative absence of standards regarding marijuana use would complicate the defense.

“Unless you can competently discuss the pros and cons of herbal cannabis, including indications and contraindications that are relevant to informed consent, you would be wise to consider carefully any decision to prescribe,” Dr. Gourlay suggested.

The problem for many clinicians, according to Dr. Gourlay, is that patients often are already using marijuana and employ a variety of strategies to induce the physician to provide a prescription to legitimize this activity. He outlined several familiar traps that he urged physicians to avoid. These include claims by patients that a prescription would protect them from legal problems for a drug they will be using in any event or that clinicians can provide a dosing regimen that can be the basis for a plan to eventually taper use.

“Once you start down this road, it will be very difficult to change course,” said Dr. Gourlay, noting that even a discussion of marijuana should be well documented so that there are no misinterpretations regarding instructions about use or avoiding use. In situations in which patients are insistent about their need for marijuana, “consider having a third party in the room,” he suggested.

In areas where cannabinoids are available in well-defined concentrations for oral delivery, a stronger case can be made for medicinal applications, but clinical studies still remain limited, Dr. Gourlay said. He said he hopes trials will eventually be conducted to gauge the benefit-to-risk ratio for specific indications.

“I am not anticannabinoids, but I have never prescribed cannabis to smoke,” Dr. Gourlay reported. Even though recent legislation now permits recreational use of marijuana in several states, Dr. Gourlay urged clinicians to employ a conservative approach to clinical use until more data clarify both the drug’s benefits and safety.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

ORLANDO – Good data suggest that marijuana has legitimate medical indications, but smoking the drug is not the appropriate method of delivery, and clinicians without experience with marijuana should consider its many liabilities before issuing a prescription, according to an expert who said he is not antimarijuana and has prescribed this therapy himself.

“Dried cannabis is not a medication in any traditional sense of the word. That does not mean cannabinoids have no legitimate indication as therapeutic agents, but smoking anything for your health is something of an oxymoron,” Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto said at the Pain Care for Primary Care meeting.

Cannabis, distinct from cannabinoids, is defined as the dried leaves of the marijuana plant. According to Dr. Gourlay, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice, the plant has more than 400 compounds, including more than 60 cannabinoids, which are chemicals that act on cannabinoid receptors, primarily in the central nervous system. For physicians wishing to deliver cannabinoids for a medical indication, the problem posed by cannabis is quality control.

“You are being asked to prescribe something for which you have no practical means of titrating the dose,” Dr. Gourlay said. Even ignoring the potential risks of exposing the lungs to a variety of oxidized chemicals with no known therapeutic benefit, the absence of quality control will be problematic if the patient or family members subsequently claim iatrogenic harm.

For recreational use of cannabis, the focus has been on the concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is the cannabinoid most closely associated with euphoric effects. However, the potential medical benefits of marijuana, such as relief of glaucoma symptoms, reduction of chemotherapy-induced nausea, or control of neuropathic pain, are not necessarily related to THC. Well-designed clinical studies aimed at determining which other cannabinoids and at which doses are most relevant for medical use have yet to be performed, Dr. Gourlay said.

For the clinician, legalization of medical marijuana in the absence of reliable data on best practice creates some potential risks. According to Dr. Gourlay, patients who harm themselves or others in an accident attributed to impaired judgment from medical marijuana might pursue legal action against the prescribing physician. The relative absence of standards regarding marijuana use would complicate the defense.

“Unless you can competently discuss the pros and cons of herbal cannabis, including indications and contraindications that are relevant to informed consent, you would be wise to consider carefully any decision to prescribe,” Dr. Gourlay suggested.

The problem for many clinicians, according to Dr. Gourlay, is that patients often are already using marijuana and employ a variety of strategies to induce the physician to provide a prescription to legitimize this activity. He outlined several familiar traps that he urged physicians to avoid. These include claims by patients that a prescription would protect them from legal problems for a drug they will be using in any event or that clinicians can provide a dosing regimen that can be the basis for a plan to eventually taper use.

“Once you start down this road, it will be very difficult to change course,” said Dr. Gourlay, noting that even a discussion of marijuana should be well documented so that there are no misinterpretations regarding instructions about use or avoiding use. In situations in which patients are insistent about their need for marijuana, “consider having a third party in the room,” he suggested.

In areas where cannabinoids are available in well-defined concentrations for oral delivery, a stronger case can be made for medicinal applications, but clinical studies still remain limited, Dr. Gourlay said. He said he hopes trials will eventually be conducted to gauge the benefit-to-risk ratio for specific indications.

“I am not anticannabinoids, but I have never prescribed cannabis to smoke,” Dr. Gourlay reported. Even though recent legislation now permits recreational use of marijuana in several states, Dr. Gourlay urged clinicians to employ a conservative approach to clinical use until more data clarify both the drug’s benefits and safety.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

ORLANDO – Good data suggest that marijuana has legitimate medical indications, but smoking the drug is not the appropriate method of delivery, and clinicians without experience with marijuana should consider its many liabilities before issuing a prescription, according to an expert who said he is not antimarijuana and has prescribed this therapy himself.

“Dried cannabis is not a medication in any traditional sense of the word. That does not mean cannabinoids have no legitimate indication as therapeutic agents, but smoking anything for your health is something of an oxymoron,” Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto said at the Pain Care for Primary Care meeting.

Cannabis, distinct from cannabinoids, is defined as the dried leaves of the marijuana plant. According to Dr. Gourlay, who spoke at the meeting, which was cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice, the plant has more than 400 compounds, including more than 60 cannabinoids, which are chemicals that act on cannabinoid receptors, primarily in the central nervous system. For physicians wishing to deliver cannabinoids for a medical indication, the problem posed by cannabis is quality control.

“You are being asked to prescribe something for which you have no practical means of titrating the dose,” Dr. Gourlay said. Even ignoring the potential risks of exposing the lungs to a variety of oxidized chemicals with no known therapeutic benefit, the absence of quality control will be problematic if the patient or family members subsequently claim iatrogenic harm.

For recreational use of cannabis, the focus has been on the concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is the cannabinoid most closely associated with euphoric effects. However, the potential medical benefits of marijuana, such as relief of glaucoma symptoms, reduction of chemotherapy-induced nausea, or control of neuropathic pain, are not necessarily related to THC. Well-designed clinical studies aimed at determining which other cannabinoids and at which doses are most relevant for medical use have yet to be performed, Dr. Gourlay said.

For the clinician, legalization of medical marijuana in the absence of reliable data on best practice creates some potential risks. According to Dr. Gourlay, patients who harm themselves or others in an accident attributed to impaired judgment from medical marijuana might pursue legal action against the prescribing physician. The relative absence of standards regarding marijuana use would complicate the defense.

“Unless you can competently discuss the pros and cons of herbal cannabis, including indications and contraindications that are relevant to informed consent, you would be wise to consider carefully any decision to prescribe,” Dr. Gourlay suggested.

The problem for many clinicians, according to Dr. Gourlay, is that patients often are already using marijuana and employ a variety of strategies to induce the physician to provide a prescription to legitimize this activity. He outlined several familiar traps that he urged physicians to avoid. These include claims by patients that a prescription would protect them from legal problems for a drug they will be using in any event or that clinicians can provide a dosing regimen that can be the basis for a plan to eventually taper use.

“Once you start down this road, it will be very difficult to change course,” said Dr. Gourlay, noting that even a discussion of marijuana should be well documented so that there are no misinterpretations regarding instructions about use or avoiding use. In situations in which patients are insistent about their need for marijuana, “consider having a third party in the room,” he suggested.

In areas where cannabinoids are available in well-defined concentrations for oral delivery, a stronger case can be made for medicinal applications, but clinical studies still remain limited, Dr. Gourlay said. He said he hopes trials will eventually be conducted to gauge the benefit-to-risk ratio for specific indications.

“I am not anticannabinoids, but I have never prescribed cannabis to smoke,” Dr. Gourlay reported. Even though recent legislation now permits recreational use of marijuana in several states, Dr. Gourlay urged clinicians to employ a conservative approach to clinical use until more data clarify both the drug’s benefits and safety.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE MEETING

PCPC: Document illicit drug use in patients prescribed opioids

ORLANDO – Evidence of illicit drug use in patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain is a red flag that requires clinical action, but immediately discontinuing opioids is not essential, three experts who participated in a panel discussion agreed.

“Never ignore a positive urine, but document fully what course of action you plan to take,” Dr. Howard A. Heit of Georgetown University in Washington said at the meeting, cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice.

Often, evidence of cocaine, marijuana, or other illicit drugs in the urine is a direct violation of the patient-prescriber agreement signed when opioids are initiated. Such a violation should be considered in the decision to continue opioid treatment, but sudden discontinuation of opioids carries its own set of risks. According to the assembled experts, the next clinical steps should be evaluated in the context of benefits and risks.

Specifically, withdrawal symptoms induced by sudden discontinuation of opioids impose their own health risks and should be minimized, according to the experts. Although recreational use of cocaine, marijuana, and other illicit drugs should be considered a red flag in a patient taking opioids for pain, illicit drug use is common in the general population and might not necessarily confirm a serious pattern of aberrant behavior.

Each situation is different, but a positive cocaine test “would probably make me want to impose more restrictions [on the prescription of opioids] and see the patient more frequently,” said Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto. He, like the others, said he would discontinue opioids in patients who repeatedly tested positive for illicit drugs, but he noted that the control of chronic pain should not be abandoned as a therapeutic goal even if patients have addiction.

“You have to look at the whole clinical picture,” agreed Dr. Edwin A. Salsitz. “Like it or not, a lot of people think that smoking marijuana occasionally is not a big deal, so I think it is important to consider the whole case. Are they otherwise moving ahead in terms of job, family, etcetera,” asked Dr. Salsitz of the department of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

The answer to this question could be no, in which case illicit drug use should be considered an indicator of risk for opioid abuse. In these patients, opioids should be weaned rapidly, according to Dr. Heit, but he said that in these situations, “I am going to fire the molecule and not the patient.” He acknowledged that some patients may, in turn, “fire me because I will no longer give them the opioid,” but he suggested that physicians should be sensitive to both chronic pain and the disease of addiction when they are comorbidities. Efforts should be made to continue to address pain while helping the patient avoid the risks of drug abuse.

All three experts agreed that continued use of opioids is not illegal in a patient whose urinalysis tests positive for illicit drug use. They also agreed that this information cannot be ignored. Each repeatedly emphasized that the clinician’s medical record must acknowledge this positive result and outline the course of action that it has engendered, such as more rigorous monitoring.

“Use this as an opportunity to invoke change,” Dr. Gourlay said. He cautioned that overlooking a positive urine test poses medicolegal risks to the physician, but he also emphasized the need for physicians to consider how to manage chronic pain in the context of this new information.

Dr. Heit and Dr. Salsitz reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Gourlay reported having a financial relationship with Millennium Health. The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

ORLANDO – Evidence of illicit drug use in patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain is a red flag that requires clinical action, but immediately discontinuing opioids is not essential, three experts who participated in a panel discussion agreed.

“Never ignore a positive urine, but document fully what course of action you plan to take,” Dr. Howard A. Heit of Georgetown University in Washington said at the meeting, cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice.

Often, evidence of cocaine, marijuana, or other illicit drugs in the urine is a direct violation of the patient-prescriber agreement signed when opioids are initiated. Such a violation should be considered in the decision to continue opioid treatment, but sudden discontinuation of opioids carries its own set of risks. According to the assembled experts, the next clinical steps should be evaluated in the context of benefits and risks.

Specifically, withdrawal symptoms induced by sudden discontinuation of opioids impose their own health risks and should be minimized, according to the experts. Although recreational use of cocaine, marijuana, and other illicit drugs should be considered a red flag in a patient taking opioids for pain, illicit drug use is common in the general population and might not necessarily confirm a serious pattern of aberrant behavior.

Each situation is different, but a positive cocaine test “would probably make me want to impose more restrictions [on the prescription of opioids] and see the patient more frequently,” said Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto. He, like the others, said he would discontinue opioids in patients who repeatedly tested positive for illicit drugs, but he noted that the control of chronic pain should not be abandoned as a therapeutic goal even if patients have addiction.

“You have to look at the whole clinical picture,” agreed Dr. Edwin A. Salsitz. “Like it or not, a lot of people think that smoking marijuana occasionally is not a big deal, so I think it is important to consider the whole case. Are they otherwise moving ahead in terms of job, family, etcetera,” asked Dr. Salsitz of the department of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

The answer to this question could be no, in which case illicit drug use should be considered an indicator of risk for opioid abuse. In these patients, opioids should be weaned rapidly, according to Dr. Heit, but he said that in these situations, “I am going to fire the molecule and not the patient.” He acknowledged that some patients may, in turn, “fire me because I will no longer give them the opioid,” but he suggested that physicians should be sensitive to both chronic pain and the disease of addiction when they are comorbidities. Efforts should be made to continue to address pain while helping the patient avoid the risks of drug abuse.

All three experts agreed that continued use of opioids is not illegal in a patient whose urinalysis tests positive for illicit drug use. They also agreed that this information cannot be ignored. Each repeatedly emphasized that the clinician’s medical record must acknowledge this positive result and outline the course of action that it has engendered, such as more rigorous monitoring.

“Use this as an opportunity to invoke change,” Dr. Gourlay said. He cautioned that overlooking a positive urine test poses medicolegal risks to the physician, but he also emphasized the need for physicians to consider how to manage chronic pain in the context of this new information.

Dr. Heit and Dr. Salsitz reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Gourlay reported having a financial relationship with Millennium Health. The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

ORLANDO – Evidence of illicit drug use in patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain is a red flag that requires clinical action, but immediately discontinuing opioids is not essential, three experts who participated in a panel discussion agreed.

“Never ignore a positive urine, but document fully what course of action you plan to take,” Dr. Howard A. Heit of Georgetown University in Washington said at the meeting, cosponsored by the Journal of Family Practice.

Often, evidence of cocaine, marijuana, or other illicit drugs in the urine is a direct violation of the patient-prescriber agreement signed when opioids are initiated. Such a violation should be considered in the decision to continue opioid treatment, but sudden discontinuation of opioids carries its own set of risks. According to the assembled experts, the next clinical steps should be evaluated in the context of benefits and risks.

Specifically, withdrawal symptoms induced by sudden discontinuation of opioids impose their own health risks and should be minimized, according to the experts. Although recreational use of cocaine, marijuana, and other illicit drugs should be considered a red flag in a patient taking opioids for pain, illicit drug use is common in the general population and might not necessarily confirm a serious pattern of aberrant behavior.

Each situation is different, but a positive cocaine test “would probably make me want to impose more restrictions [on the prescription of opioids] and see the patient more frequently,” said Dr. Douglas L. Gourlay of the departments of anesthesiology and psychiatry at the University of Toronto. He, like the others, said he would discontinue opioids in patients who repeatedly tested positive for illicit drugs, but he noted that the control of chronic pain should not be abandoned as a therapeutic goal even if patients have addiction.

“You have to look at the whole clinical picture,” agreed Dr. Edwin A. Salsitz. “Like it or not, a lot of people think that smoking marijuana occasionally is not a big deal, so I think it is important to consider the whole case. Are they otherwise moving ahead in terms of job, family, etcetera,” asked Dr. Salsitz of the department of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

The answer to this question could be no, in which case illicit drug use should be considered an indicator of risk for opioid abuse. In these patients, opioids should be weaned rapidly, according to Dr. Heit, but he said that in these situations, “I am going to fire the molecule and not the patient.” He acknowledged that some patients may, in turn, “fire me because I will no longer give them the opioid,” but he suggested that physicians should be sensitive to both chronic pain and the disease of addiction when they are comorbidities. Efforts should be made to continue to address pain while helping the patient avoid the risks of drug abuse.

All three experts agreed that continued use of opioids is not illegal in a patient whose urinalysis tests positive for illicit drug use. They also agreed that this information cannot be ignored. Each repeatedly emphasized that the clinician’s medical record must acknowledge this positive result and outline the course of action that it has engendered, such as more rigorous monitoring.

“Use this as an opportunity to invoke change,” Dr. Gourlay said. He cautioned that overlooking a positive urine test poses medicolegal risks to the physician, but he also emphasized the need for physicians to consider how to manage chronic pain in the context of this new information.

Dr. Heit and Dr. Salsitz reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Gourlay reported having a financial relationship with Millennium Health. The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The Journal of Family Practice and this news organization are owned by the same company.

The meeting was held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. Global Academy and this news organization are owned the same company.

This post has been updated 8/5/2015.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE MEETING