User login

Central Surgical Association (CSA): Annual Meeting

Commercial board-review courses offer no bang for the buck

CHICAGO – A national survey of 1,246 residents found no evidence that taking a commercial board-review course provides any benefit in passing the American Board of Surgery certifying exam.

And none of the courses was significantly better than another, reported Dr. Mark Malangoni, an ACS Fellow and ABS associate executive director.

“Exam-review courses are now a multibillion-dollar industry … but there is little evidence to suggest they actually improve exam performance,” he said.

Dr. Malangoni and his ABS colleagues electronically surveyed 1,396 candidates who took the ABS certifying exam (CE) during the 2012-2013 academic year. Of the 1,246 who responded, 974 (78%) had taken a review course. Another 140 candidates declined to respond to the two-question survey, but their CE test results were available for comparison.

Among first-time examinees, the CE pass rate was 83.7% with any review course, 80.7% with no course, and 75.6% for the nonresponders, Dr. Malangoni said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Among those who had taken the CE before, pass rates were 77%, 69%, and 58%, respectively, with the intergroup difference statistically significant only for the nonresponders (P value = .01).

Despite the lack of benefit, however, most examinees (64%) believed that the review course improved their preparation for the CE, he said.

Those repeating the CE were significantly more likely than first-time examinees to take a review course (84.6% vs. 76.1%; P = .002).

Several candidates decided that multiple review courses might be better: 16% of the first-time examinees and 32% of the repeat examinees. Again, pass rates were not significantly different with multiple courses, Dr. Malangoni said.

The survey identified nine commercially available courses, but five were not analyzed because there were no enrollees or a low number (≤ 40) of enrollees. The remaining four courses were assigned a letter for anonymity. Enrollment in all courses ranged from 21 to 706 students.

In multivariate analysis, the only significant predictor for passing the initial CE was the qualifying examination scale score (Odds ratio, 1.09; P < .001). Course D trended toward a benefit, but the 99% confidence intervals overlapped and the P value did not meet the predetermined threshold of ≤ .01 (OR, 3.25; P = .02; 99% CI 0.86-12.22), he said.

For repeat examinees, no variables including the four review courses, gender, program size, or international medical graduation significantly predicted success on the CE exam.

“Given the time and effort, and expense, we feel that CE candidates should consider these results when assessing how best to prepare for this examination,” Dr. Malangoni concluded.

The study is not the first to question the benefit of review courses for already cash-strapped medical students and residents (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011:365:104-5), he noted.

Dr. Malangoni balked, however, at suggesting review courses may not be worth the investment for any candidate.

“Our results are applicable to a large group; however, it is not possible to determine when taking a review course would be beneficial for a specific candidate,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Malangoni reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @pwendl

CHICAGO – A national survey of 1,246 residents found no evidence that taking a commercial board-review course provides any benefit in passing the American Board of Surgery certifying exam.

And none of the courses was significantly better than another, reported Dr. Mark Malangoni, an ACS Fellow and ABS associate executive director.

“Exam-review courses are now a multibillion-dollar industry … but there is little evidence to suggest they actually improve exam performance,” he said.

Dr. Malangoni and his ABS colleagues electronically surveyed 1,396 candidates who took the ABS certifying exam (CE) during the 2012-2013 academic year. Of the 1,246 who responded, 974 (78%) had taken a review course. Another 140 candidates declined to respond to the two-question survey, but their CE test results were available for comparison.

Among first-time examinees, the CE pass rate was 83.7% with any review course, 80.7% with no course, and 75.6% for the nonresponders, Dr. Malangoni said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Among those who had taken the CE before, pass rates were 77%, 69%, and 58%, respectively, with the intergroup difference statistically significant only for the nonresponders (P value = .01).

Despite the lack of benefit, however, most examinees (64%) believed that the review course improved their preparation for the CE, he said.

Those repeating the CE were significantly more likely than first-time examinees to take a review course (84.6% vs. 76.1%; P = .002).

Several candidates decided that multiple review courses might be better: 16% of the first-time examinees and 32% of the repeat examinees. Again, pass rates were not significantly different with multiple courses, Dr. Malangoni said.

The survey identified nine commercially available courses, but five were not analyzed because there were no enrollees or a low number (≤ 40) of enrollees. The remaining four courses were assigned a letter for anonymity. Enrollment in all courses ranged from 21 to 706 students.

In multivariate analysis, the only significant predictor for passing the initial CE was the qualifying examination scale score (Odds ratio, 1.09; P < .001). Course D trended toward a benefit, but the 99% confidence intervals overlapped and the P value did not meet the predetermined threshold of ≤ .01 (OR, 3.25; P = .02; 99% CI 0.86-12.22), he said.

For repeat examinees, no variables including the four review courses, gender, program size, or international medical graduation significantly predicted success on the CE exam.

“Given the time and effort, and expense, we feel that CE candidates should consider these results when assessing how best to prepare for this examination,” Dr. Malangoni concluded.

The study is not the first to question the benefit of review courses for already cash-strapped medical students and residents (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011:365:104-5), he noted.

Dr. Malangoni balked, however, at suggesting review courses may not be worth the investment for any candidate.

“Our results are applicable to a large group; however, it is not possible to determine when taking a review course would be beneficial for a specific candidate,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Malangoni reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @pwendl

CHICAGO – A national survey of 1,246 residents found no evidence that taking a commercial board-review course provides any benefit in passing the American Board of Surgery certifying exam.

And none of the courses was significantly better than another, reported Dr. Mark Malangoni, an ACS Fellow and ABS associate executive director.

“Exam-review courses are now a multibillion-dollar industry … but there is little evidence to suggest they actually improve exam performance,” he said.

Dr. Malangoni and his ABS colleagues electronically surveyed 1,396 candidates who took the ABS certifying exam (CE) during the 2012-2013 academic year. Of the 1,246 who responded, 974 (78%) had taken a review course. Another 140 candidates declined to respond to the two-question survey, but their CE test results were available for comparison.

Among first-time examinees, the CE pass rate was 83.7% with any review course, 80.7% with no course, and 75.6% for the nonresponders, Dr. Malangoni said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Among those who had taken the CE before, pass rates were 77%, 69%, and 58%, respectively, with the intergroup difference statistically significant only for the nonresponders (P value = .01).

Despite the lack of benefit, however, most examinees (64%) believed that the review course improved their preparation for the CE, he said.

Those repeating the CE were significantly more likely than first-time examinees to take a review course (84.6% vs. 76.1%; P = .002).

Several candidates decided that multiple review courses might be better: 16% of the first-time examinees and 32% of the repeat examinees. Again, pass rates were not significantly different with multiple courses, Dr. Malangoni said.

The survey identified nine commercially available courses, but five were not analyzed because there were no enrollees or a low number (≤ 40) of enrollees. The remaining four courses were assigned a letter for anonymity. Enrollment in all courses ranged from 21 to 706 students.

In multivariate analysis, the only significant predictor for passing the initial CE was the qualifying examination scale score (Odds ratio, 1.09; P < .001). Course D trended toward a benefit, but the 99% confidence intervals overlapped and the P value did not meet the predetermined threshold of ≤ .01 (OR, 3.25; P = .02; 99% CI 0.86-12.22), he said.

For repeat examinees, no variables including the four review courses, gender, program size, or international medical graduation significantly predicted success on the CE exam.

“Given the time and effort, and expense, we feel that CE candidates should consider these results when assessing how best to prepare for this examination,” Dr. Malangoni concluded.

The study is not the first to question the benefit of review courses for already cash-strapped medical students and residents (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011:365:104-5), he noted.

Dr. Malangoni balked, however, at suggesting review courses may not be worth the investment for any candidate.

“Our results are applicable to a large group; however, it is not possible to determine when taking a review course would be beneficial for a specific candidate,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Malangoni reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @pwendl

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Commercial board-review courses do not improve the likelihood of passing the American Board of Surgery certifying exam.

Major finding: For first-time examinees, the pass rate was 83.7% with a review course, 80.7% with no course, and 75.6% for nonresponders.

Data source: Survey of 1,246 candidates taking the ABS certifying exam.

Disclosures: Dr. Malangoni reported having no financial disclosures.

U-tube drainage adds option for necrotizing pancreatitis

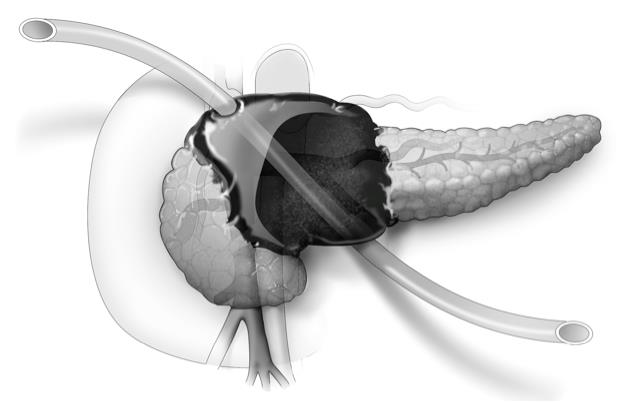

CHICAGO – Placement of a U-tube drain provides enhanced percutaneous drainage and minimizes catheter-related complications in patients with complicated or infected necrotizing pancreatitis, new research suggests.

The U-tube method uses a large, 20-French Silastic tube with numerous large holes in the middle. One exit must be anterior through the peritoneal cavity and the other can be posterior in the retroperitoneum, Dr. Daniel E. Abbott said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The novel drainage system allows bidirectional flushing, greater interface with large fluid collections leading to more rapid resolution of retroperitoneal necrosis, and less risk of dislodgement resulting in fewer catheter exchanges or replacements. The system also creates a large-bore fistula tract to fall back on should subsequent fistulojejunostomy be needed, said Dr. Abbott of the University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

He reported on the largest clinical experience with primary U-tube drainage to date, involving 22 patients with necrotizing pancreatitis (NP) treated from 2011 to 2014. In 7 patients, (32%) no surgical procedure was ultimately required.

Of the others, 13 required further surgical intervention for a disrupted duct, and (59%) 2 patients died (9.1% ), Dr. Abbott said. Among eight patients who underwent fistulojejunostomy and five who underwent distal pancreatectomy and/or splenectomy, NP resolved in all but one patient with a recurrent amylase-rich fluid leak.

This compares favorably with a 20% mortality rate and 80% NP resolution among five institutional controls treated with open necrosectomy, he said.

Dr. Abbott acknowledged that the study was limited by small numbers and an insufficient control group for direct comparison.

Other studies have shown mortality rates in NP ranging from 39% with open necrosectomy to 4.5% with focused open necrosectomy, but their median length of stays were 54.5 days and 57 days, respectively. LOS was trimmed to just 19 days in one open necrosectomy study (Ann. Surg. 2008;247:294-9), but mortality was 11.4%, Dr. Abbott observed.

Dr. Abbott’s center is currently placing one to two U-tubes per month in patients with symptomatic NP (nausea, vomiting, weight loss, or infection on radiographic imaging) amenable to drainage and plans to update the analysis with prospectively collected data, including costs, in 2-3 years, he said.

“The U-tube obviously seems to work very well, but ... our radiologists sometimes have a hard time placing just one single tube. That [U-]tube, in particular, has to come anterior and out posterior and other organs can potentially get in the way,” said Dr. Michael Ujiki, director of minimally invasive surgery at NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Ill.

The morbidity and mortality rates are certainly better, but the improvements could be the result of improved ICU care or getting away from antibiotics, said Dr. Ujiki, a discussant at the meeting.

Dr. Abbott noted that “we are operating on people when they’re generally well instead of operating when they’re generally sick. When you’re doing an open necrosectomy, not only might there be multisystem organ failure, but [patients’] nutritional status is undoubtedly poor as well.”

Radiologists have yet to be unable to place a U-tube, but have delayed placement in stable, normotensive patients until fluid collections get larger to provide a better target, he said. The U-tube also can be placed at separate interventions. The two things patients complain most about are the size of the large tubes and when enzymatic fluid leaks onto their skin if the tube become clogged.

CHICAGO – Placement of a U-tube drain provides enhanced percutaneous drainage and minimizes catheter-related complications in patients with complicated or infected necrotizing pancreatitis, new research suggests.

The U-tube method uses a large, 20-French Silastic tube with numerous large holes in the middle. One exit must be anterior through the peritoneal cavity and the other can be posterior in the retroperitoneum, Dr. Daniel E. Abbott said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The novel drainage system allows bidirectional flushing, greater interface with large fluid collections leading to more rapid resolution of retroperitoneal necrosis, and less risk of dislodgement resulting in fewer catheter exchanges or replacements. The system also creates a large-bore fistula tract to fall back on should subsequent fistulojejunostomy be needed, said Dr. Abbott of the University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

He reported on the largest clinical experience with primary U-tube drainage to date, involving 22 patients with necrotizing pancreatitis (NP) treated from 2011 to 2014. In 7 patients, (32%) no surgical procedure was ultimately required.

Of the others, 13 required further surgical intervention for a disrupted duct, and (59%) 2 patients died (9.1% ), Dr. Abbott said. Among eight patients who underwent fistulojejunostomy and five who underwent distal pancreatectomy and/or splenectomy, NP resolved in all but one patient with a recurrent amylase-rich fluid leak.

This compares favorably with a 20% mortality rate and 80% NP resolution among five institutional controls treated with open necrosectomy, he said.

Dr. Abbott acknowledged that the study was limited by small numbers and an insufficient control group for direct comparison.

Other studies have shown mortality rates in NP ranging from 39% with open necrosectomy to 4.5% with focused open necrosectomy, but their median length of stays were 54.5 days and 57 days, respectively. LOS was trimmed to just 19 days in one open necrosectomy study (Ann. Surg. 2008;247:294-9), but mortality was 11.4%, Dr. Abbott observed.

Dr. Abbott’s center is currently placing one to two U-tubes per month in patients with symptomatic NP (nausea, vomiting, weight loss, or infection on radiographic imaging) amenable to drainage and plans to update the analysis with prospectively collected data, including costs, in 2-3 years, he said.

“The U-tube obviously seems to work very well, but ... our radiologists sometimes have a hard time placing just one single tube. That [U-]tube, in particular, has to come anterior and out posterior and other organs can potentially get in the way,” said Dr. Michael Ujiki, director of minimally invasive surgery at NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Ill.

The morbidity and mortality rates are certainly better, but the improvements could be the result of improved ICU care or getting away from antibiotics, said Dr. Ujiki, a discussant at the meeting.

Dr. Abbott noted that “we are operating on people when they’re generally well instead of operating when they’re generally sick. When you’re doing an open necrosectomy, not only might there be multisystem organ failure, but [patients’] nutritional status is undoubtedly poor as well.”

Radiologists have yet to be unable to place a U-tube, but have delayed placement in stable, normotensive patients until fluid collections get larger to provide a better target, he said. The U-tube also can be placed at separate interventions. The two things patients complain most about are the size of the large tubes and when enzymatic fluid leaks onto their skin if the tube become clogged.

CHICAGO – Placement of a U-tube drain provides enhanced percutaneous drainage and minimizes catheter-related complications in patients with complicated or infected necrotizing pancreatitis, new research suggests.

The U-tube method uses a large, 20-French Silastic tube with numerous large holes in the middle. One exit must be anterior through the peritoneal cavity and the other can be posterior in the retroperitoneum, Dr. Daniel E. Abbott said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The novel drainage system allows bidirectional flushing, greater interface with large fluid collections leading to more rapid resolution of retroperitoneal necrosis, and less risk of dislodgement resulting in fewer catheter exchanges or replacements. The system also creates a large-bore fistula tract to fall back on should subsequent fistulojejunostomy be needed, said Dr. Abbott of the University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

He reported on the largest clinical experience with primary U-tube drainage to date, involving 22 patients with necrotizing pancreatitis (NP) treated from 2011 to 2014. In 7 patients, (32%) no surgical procedure was ultimately required.

Of the others, 13 required further surgical intervention for a disrupted duct, and (59%) 2 patients died (9.1% ), Dr. Abbott said. Among eight patients who underwent fistulojejunostomy and five who underwent distal pancreatectomy and/or splenectomy, NP resolved in all but one patient with a recurrent amylase-rich fluid leak.

This compares favorably with a 20% mortality rate and 80% NP resolution among five institutional controls treated with open necrosectomy, he said.

Dr. Abbott acknowledged that the study was limited by small numbers and an insufficient control group for direct comparison.

Other studies have shown mortality rates in NP ranging from 39% with open necrosectomy to 4.5% with focused open necrosectomy, but their median length of stays were 54.5 days and 57 days, respectively. LOS was trimmed to just 19 days in one open necrosectomy study (Ann. Surg. 2008;247:294-9), but mortality was 11.4%, Dr. Abbott observed.

Dr. Abbott’s center is currently placing one to two U-tubes per month in patients with symptomatic NP (nausea, vomiting, weight loss, or infection on radiographic imaging) amenable to drainage and plans to update the analysis with prospectively collected data, including costs, in 2-3 years, he said.

“The U-tube obviously seems to work very well, but ... our radiologists sometimes have a hard time placing just one single tube. That [U-]tube, in particular, has to come anterior and out posterior and other organs can potentially get in the way,” said Dr. Michael Ujiki, director of minimally invasive surgery at NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Ill.

The morbidity and mortality rates are certainly better, but the improvements could be the result of improved ICU care or getting away from antibiotics, said Dr. Ujiki, a discussant at the meeting.

Dr. Abbott noted that “we are operating on people when they’re generally well instead of operating when they’re generally sick. When you’re doing an open necrosectomy, not only might there be multisystem organ failure, but [patients’] nutritional status is undoubtedly poor as well.”

Radiologists have yet to be unable to place a U-tube, but have delayed placement in stable, normotensive patients until fluid collections get larger to provide a better target, he said. The U-tube also can be placed at separate interventions. The two things patients complain most about are the size of the large tubes and when enzymatic fluid leaks onto their skin if the tube become clogged.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: U-tube drainage may eliminate the need for surgery in severe necrotizing pancreatitis.

Major finding: Disease-specific mortality occurred in 2 of 22 patients.

Data source: Retrospective study of 22 patients with symptomatic and/or infected necrotizing pancreatitis.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial conflicts.

Smaller tubes take bite out of blood draws in critically ill

CHICAGO – Switching from conventional to small-volume phlebotomy tubes is an easy step toward reducing iatrogenic blood loss in critically ill adults, a new study suggests.

“We were looking at the amount of blood we were drawing off these patients and when we asked the nurses, the numbers were crazy. It could be as high as 20 mL per time that they drew off the patient and we felt we had to do better. The common sense dictum is the more blood you draw off, the more harm you are causing the patient,” principal investigator Dr. Heather Dolman from Detroit Receiving Hospital, Wayne State University, said in an interview.

For patients staying only a day or 2 at the hospital, the type of blood tube used may not make a difference. But for the critically ill, who studies suggest can have an average of 5 to more than 24 samples drawn a day, the cumulative blood loss over an extended stay can be sizable.

Clinicians are also inclined to order more diagnostic tests as the severity of illness increases, thus putting their sickest patients at the greatest risk of iatrogenic anemia and transfusion. Anemia secondary to phlebotomy accounts for up to 40% of packed red blood cells transfused, Dr. Dolman noted at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The process of blood sampling itself also involves a fair amount of waste. Conventional arterial line systems require that an initial blood sample be removed to “clear the line.” This typically results in 2-10 mL of blood being discarded before a second sample of undiluted blood can be obtained.

Some hospitals have turned to closed blood sampling devices that avoid the need for a second sample. The impact of blood-conserving devices on transfusion rates has been underwhelming, with only one study showing a positive impact leading to reduced blood product use.

As part of their blood-conserving strategy, Dr. Dolman and her colleagues asked the hospital to invest in small-volume phlebotomy tubes (SVTs), which are sized somewhere between a conventional-volume tube (CVT) and a pediatric blood tube.

SVTs reduce the amount of blood needed from 8.5 mL with a conventional tube to 5.0 mL for a basic metabolic panel, from 6.0 mL to 2.0 mL for a complete blood count (CBC) or cross-matching, and from 2.7 mL to 1.8 mL for a prothrombin time /internationalized ratio/partial thromboplastin time, Dr. Dolman said. The cost of an SVT is the same as a CVT, as is the cost of the machinery needed to analyze the samples.

“Everyone is worried about missing out on data, but if you look at the research on the amount of blood the machine really needs, it is only 0.1 mL, that’s less than a cc,” she said. “The technology has been there for a while, I just think the common sense aspect of all this, no one has ever thought of.”

The investigators then retrospectively compared 248 critically ill patients in the ICU, of whom 116 had blood drawn with an SVT and 132 with a CVT. The two groups were well matched with respect to age (55 years vs. 57 years), admission to the emergency surgery/trauma service (63% vs. 64%), and mean APACHE II scores (14.1 vs. 12.7).

Transfusion was at the discretion of the primary team using a restrictive hemoglobin threshold of < 7.0 gm/dL, unless hemodynamic instability or active bleeding were present.

Utilizing an SVT significantly reduced daily blood loss from phlebotomy from 31.7 mL with a CVT to 22.5 mL (P < .0001) and overall phlebotomy blood loss from 299 mL to 174 mL (P < .001), Dr. Dolman reported.

This translated into a nonsignificant trend for fewer units of packed red blood cells transfused in the SVT group (mean 4.4 vs. 6.0; P = .16).

The same pattern was observed in the 158 patients admitted to the emergency surgery/trauma service, with SVT also leading to significantly fewer episodes of severe anemia (6 vs. 20; P = .01) and a trend toward shorter ICU stays (9.2 days vs. 10.6 days; P = .46), she said.

Patients with an APACHE score of at least 20, a group one would anticipate to derive greater advantage from a blood-conserving strategy, did not benefit from use of an SVT vs. a CVT, but the number of patients was very low at just 27 and 19, respectively, Dr. Dolman noted.

Anemia, however, had a profound impact on the critically ill cohort. Patients with severe anemia were significantly more likely than those with a hemoglobin level of at least 7 gm/dL to have longer ICU stays (16 days vs. 7.7 days; P < .001), longer hospital stays (23.3 days vs. 13.6 days; P < .001), and to die in the hospital (29% vs. 13%; P = .01).

Using a small-volume tube cut the number of patients with more than one episode of severe anemia from 22 to 11 (P = .01) and those with more than two episodes from 6 to 4 (P = .53).

“Anemia in the critically ill is a significant problem,” Dr. Dolman said. “Phlebotomy waste contributes to anemia and should be recorded to decrease this hidden loss.”

The impact of transfusion vs. no transfusion was less pronounced with respect to ICU stay (12 days vs. 6 days; P < .001), hospital stay (19 days vs. 11 days; P = .44), and in-hospital mortality (17% vs. 15%; P = .60), but can lead to other negative sequelae such as increased risk of infection, circulatory overload transfusion reactions, and immune modulation, she added.

Detroit Receiving Hospital continues to use conventional tubes in its ICU and other units, although a switch to small-volume tubes is expected to be considered following peer review of the full results, Dr. Dolman said.

Dr. Dolman reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @pwendl

“This is something that should be replicated at institutions across the country,” discussant William C. Cirocco said in an interview. “Why not? It may not have clinical implications for the patient who is only in the hospital for 2 or 3 days, but for the ICU patient, it will have big impact. It’s a no-brainer.”

Dr. William C. Cirocco is a professor of surgery at Ohio State University in Columbus. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

“This is something that should be replicated at institutions across the country,” discussant William C. Cirocco said in an interview. “Why not? It may not have clinical implications for the patient who is only in the hospital for 2 or 3 days, but for the ICU patient, it will have big impact. It’s a no-brainer.”

Dr. William C. Cirocco is a professor of surgery at Ohio State University in Columbus. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

“This is something that should be replicated at institutions across the country,” discussant William C. Cirocco said in an interview. “Why not? It may not have clinical implications for the patient who is only in the hospital for 2 or 3 days, but for the ICU patient, it will have big impact. It’s a no-brainer.”

Dr. William C. Cirocco is a professor of surgery at Ohio State University in Columbus. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Switching from conventional to small-volume phlebotomy tubes is an easy step toward reducing iatrogenic blood loss in critically ill adults, a new study suggests.

“We were looking at the amount of blood we were drawing off these patients and when we asked the nurses, the numbers were crazy. It could be as high as 20 mL per time that they drew off the patient and we felt we had to do better. The common sense dictum is the more blood you draw off, the more harm you are causing the patient,” principal investigator Dr. Heather Dolman from Detroit Receiving Hospital, Wayne State University, said in an interview.

For patients staying only a day or 2 at the hospital, the type of blood tube used may not make a difference. But for the critically ill, who studies suggest can have an average of 5 to more than 24 samples drawn a day, the cumulative blood loss over an extended stay can be sizable.

Clinicians are also inclined to order more diagnostic tests as the severity of illness increases, thus putting their sickest patients at the greatest risk of iatrogenic anemia and transfusion. Anemia secondary to phlebotomy accounts for up to 40% of packed red blood cells transfused, Dr. Dolman noted at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The process of blood sampling itself also involves a fair amount of waste. Conventional arterial line systems require that an initial blood sample be removed to “clear the line.” This typically results in 2-10 mL of blood being discarded before a second sample of undiluted blood can be obtained.

Some hospitals have turned to closed blood sampling devices that avoid the need for a second sample. The impact of blood-conserving devices on transfusion rates has been underwhelming, with only one study showing a positive impact leading to reduced blood product use.

As part of their blood-conserving strategy, Dr. Dolman and her colleagues asked the hospital to invest in small-volume phlebotomy tubes (SVTs), which are sized somewhere between a conventional-volume tube (CVT) and a pediatric blood tube.

SVTs reduce the amount of blood needed from 8.5 mL with a conventional tube to 5.0 mL for a basic metabolic panel, from 6.0 mL to 2.0 mL for a complete blood count (CBC) or cross-matching, and from 2.7 mL to 1.8 mL for a prothrombin time /internationalized ratio/partial thromboplastin time, Dr. Dolman said. The cost of an SVT is the same as a CVT, as is the cost of the machinery needed to analyze the samples.

“Everyone is worried about missing out on data, but if you look at the research on the amount of blood the machine really needs, it is only 0.1 mL, that’s less than a cc,” she said. “The technology has been there for a while, I just think the common sense aspect of all this, no one has ever thought of.”

The investigators then retrospectively compared 248 critically ill patients in the ICU, of whom 116 had blood drawn with an SVT and 132 with a CVT. The two groups were well matched with respect to age (55 years vs. 57 years), admission to the emergency surgery/trauma service (63% vs. 64%), and mean APACHE II scores (14.1 vs. 12.7).

Transfusion was at the discretion of the primary team using a restrictive hemoglobin threshold of < 7.0 gm/dL, unless hemodynamic instability or active bleeding were present.

Utilizing an SVT significantly reduced daily blood loss from phlebotomy from 31.7 mL with a CVT to 22.5 mL (P < .0001) and overall phlebotomy blood loss from 299 mL to 174 mL (P < .001), Dr. Dolman reported.

This translated into a nonsignificant trend for fewer units of packed red blood cells transfused in the SVT group (mean 4.4 vs. 6.0; P = .16).

The same pattern was observed in the 158 patients admitted to the emergency surgery/trauma service, with SVT also leading to significantly fewer episodes of severe anemia (6 vs. 20; P = .01) and a trend toward shorter ICU stays (9.2 days vs. 10.6 days; P = .46), she said.

Patients with an APACHE score of at least 20, a group one would anticipate to derive greater advantage from a blood-conserving strategy, did not benefit from use of an SVT vs. a CVT, but the number of patients was very low at just 27 and 19, respectively, Dr. Dolman noted.

Anemia, however, had a profound impact on the critically ill cohort. Patients with severe anemia were significantly more likely than those with a hemoglobin level of at least 7 gm/dL to have longer ICU stays (16 days vs. 7.7 days; P < .001), longer hospital stays (23.3 days vs. 13.6 days; P < .001), and to die in the hospital (29% vs. 13%; P = .01).

Using a small-volume tube cut the number of patients with more than one episode of severe anemia from 22 to 11 (P = .01) and those with more than two episodes from 6 to 4 (P = .53).

“Anemia in the critically ill is a significant problem,” Dr. Dolman said. “Phlebotomy waste contributes to anemia and should be recorded to decrease this hidden loss.”

The impact of transfusion vs. no transfusion was less pronounced with respect to ICU stay (12 days vs. 6 days; P < .001), hospital stay (19 days vs. 11 days; P = .44), and in-hospital mortality (17% vs. 15%; P = .60), but can lead to other negative sequelae such as increased risk of infection, circulatory overload transfusion reactions, and immune modulation, she added.

Detroit Receiving Hospital continues to use conventional tubes in its ICU and other units, although a switch to small-volume tubes is expected to be considered following peer review of the full results, Dr. Dolman said.

Dr. Dolman reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @pwendl

CHICAGO – Switching from conventional to small-volume phlebotomy tubes is an easy step toward reducing iatrogenic blood loss in critically ill adults, a new study suggests.

“We were looking at the amount of blood we were drawing off these patients and when we asked the nurses, the numbers were crazy. It could be as high as 20 mL per time that they drew off the patient and we felt we had to do better. The common sense dictum is the more blood you draw off, the more harm you are causing the patient,” principal investigator Dr. Heather Dolman from Detroit Receiving Hospital, Wayne State University, said in an interview.

For patients staying only a day or 2 at the hospital, the type of blood tube used may not make a difference. But for the critically ill, who studies suggest can have an average of 5 to more than 24 samples drawn a day, the cumulative blood loss over an extended stay can be sizable.

Clinicians are also inclined to order more diagnostic tests as the severity of illness increases, thus putting their sickest patients at the greatest risk of iatrogenic anemia and transfusion. Anemia secondary to phlebotomy accounts for up to 40% of packed red blood cells transfused, Dr. Dolman noted at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The process of blood sampling itself also involves a fair amount of waste. Conventional arterial line systems require that an initial blood sample be removed to “clear the line.” This typically results in 2-10 mL of blood being discarded before a second sample of undiluted blood can be obtained.

Some hospitals have turned to closed blood sampling devices that avoid the need for a second sample. The impact of blood-conserving devices on transfusion rates has been underwhelming, with only one study showing a positive impact leading to reduced blood product use.

As part of their blood-conserving strategy, Dr. Dolman and her colleagues asked the hospital to invest in small-volume phlebotomy tubes (SVTs), which are sized somewhere between a conventional-volume tube (CVT) and a pediatric blood tube.

SVTs reduce the amount of blood needed from 8.5 mL with a conventional tube to 5.0 mL for a basic metabolic panel, from 6.0 mL to 2.0 mL for a complete blood count (CBC) or cross-matching, and from 2.7 mL to 1.8 mL for a prothrombin time /internationalized ratio/partial thromboplastin time, Dr. Dolman said. The cost of an SVT is the same as a CVT, as is the cost of the machinery needed to analyze the samples.

“Everyone is worried about missing out on data, but if you look at the research on the amount of blood the machine really needs, it is only 0.1 mL, that’s less than a cc,” she said. “The technology has been there for a while, I just think the common sense aspect of all this, no one has ever thought of.”

The investigators then retrospectively compared 248 critically ill patients in the ICU, of whom 116 had blood drawn with an SVT and 132 with a CVT. The two groups were well matched with respect to age (55 years vs. 57 years), admission to the emergency surgery/trauma service (63% vs. 64%), and mean APACHE II scores (14.1 vs. 12.7).

Transfusion was at the discretion of the primary team using a restrictive hemoglobin threshold of < 7.0 gm/dL, unless hemodynamic instability or active bleeding were present.

Utilizing an SVT significantly reduced daily blood loss from phlebotomy from 31.7 mL with a CVT to 22.5 mL (P < .0001) and overall phlebotomy blood loss from 299 mL to 174 mL (P < .001), Dr. Dolman reported.

This translated into a nonsignificant trend for fewer units of packed red blood cells transfused in the SVT group (mean 4.4 vs. 6.0; P = .16).

The same pattern was observed in the 158 patients admitted to the emergency surgery/trauma service, with SVT also leading to significantly fewer episodes of severe anemia (6 vs. 20; P = .01) and a trend toward shorter ICU stays (9.2 days vs. 10.6 days; P = .46), she said.

Patients with an APACHE score of at least 20, a group one would anticipate to derive greater advantage from a blood-conserving strategy, did not benefit from use of an SVT vs. a CVT, but the number of patients was very low at just 27 and 19, respectively, Dr. Dolman noted.

Anemia, however, had a profound impact on the critically ill cohort. Patients with severe anemia were significantly more likely than those with a hemoglobin level of at least 7 gm/dL to have longer ICU stays (16 days vs. 7.7 days; P < .001), longer hospital stays (23.3 days vs. 13.6 days; P < .001), and to die in the hospital (29% vs. 13%; P = .01).

Using a small-volume tube cut the number of patients with more than one episode of severe anemia from 22 to 11 (P = .01) and those with more than two episodes from 6 to 4 (P = .53).

“Anemia in the critically ill is a significant problem,” Dr. Dolman said. “Phlebotomy waste contributes to anemia and should be recorded to decrease this hidden loss.”

The impact of transfusion vs. no transfusion was less pronounced with respect to ICU stay (12 days vs. 6 days; P < .001), hospital stay (19 days vs. 11 days; P = .44), and in-hospital mortality (17% vs. 15%; P = .60), but can lead to other negative sequelae such as increased risk of infection, circulatory overload transfusion reactions, and immune modulation, she added.

Detroit Receiving Hospital continues to use conventional tubes in its ICU and other units, although a switch to small-volume tubes is expected to be considered following peer review of the full results, Dr. Dolman said.

Dr. Dolman reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @pwendl

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Utilizing small-volume phlebotomy tubes minimizes diagnostic blood loss in the critically ill.

Major finding: Small tubes vs. conventional tubes reduced overall phlebotomy blood loss (174 mL vs. 299 mL; P < .001) and transfused packed RBCs (mean 4.4 units vs. 6.0 units; P = .16).

Data source: Retrospective case cohort in 248 critically ill patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Dolman reported having no financial disclosures.

Lateral neck dissection morbidity high, but transient

CHICAGO – Lateral neck dissection for thyroid cancer is associated with significant early postoperative morbidity of 20%, even in the hands of experienced endocrine surgeons at a high-volume medical center.

Among 99 procedures, 20 patients had 26 complications, including surgical site infection in 10, chyle leak in 7, spinal accessory nerve dysfunction in 7, and seroma in 2.

Long-term complications were rare, however, occurring in just one patient with a spinal accessory nerve injury, Dr. Jason A. Glenn said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Using a prospectively collected thyroid database, the investigators reviewed 96 patients who underwent lateral neck dissection (LND) for suspicion of initial or recurrent lateral neck metastases by one of four experienced endocrine surgeons at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Three patients had reoperations during the study period of February 2009 and June 2014, resulting in 99 procedures and 198 lateral necks evaluated preoperatively. Most patients were women (73%) and their median age was 45 years.

LND was performed on 127 necks and metastatic disease was confirmed in 111 (87%). This included all 82 patients who had positive preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA), 25 of 37 patients operated on without FNA, and 4 of 8 patients with a negative or nondiagnostic FNA, Dr. Glenn said.

The median number of lymph nodes excised was 22 (range 1-122), with a median of 3 (range 0-39) malignant nodes per lateral neck.

“FNA is an important adjunct in the preoperative evaluation, especially when it returns a positive result,” he said. “However, when FNA is negative, not available, or not performed, you really must consider the entire clinical picture, as 64% of these patients were found to have lymph node metastases in our study.”

Surgical drains were placed in 94% of the 127 lateral neck dissections and remained in place for a median of 6 days. The median length of stay was 1 day.

There was no association between drain duration and surgical site infection, although chyle leak was associated with a significantly longer median drain duration (12 days vs. 6 days; P value < .01), Dr. Glenn said.

Two of the seven patients with chyle leak, defined by drain output that was milky white and/or exceeded 1,000 cc in 24 hours, underwent reoperation with ligation of the cervical thoracic duct and fibrin sealant application. Both leaks resolved and patients were discharge on postoperative day 2.

“Surgical drains allow for early leak recognition and monitoring of leak resolution,” he said. “Most of these complications were diagnosed and managed on an outpatient basis, highlighting the importance of continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient setting for the treatment of thyroid cancer.”

Discussant Janice L. Pasieka, head of general surgery and a clinical professor of surgery and oncology at the University of Calgary (Alberta), said the retrospective review is a very valuable contribution to the literature because of its comprehensive follow-up.

“Today, most patients with this type of procedure are discharged within the 23 hours, and as such, complications such as nerve palsies, chyle leaks, and surgical site infections are not apparent for the majority of patients during their hospital stay,” Dr. Pasieka said. “Many times, the true incidences are lost unless the patient re-presents to the health care system, thus introducing your bias of only those significant enough to require intervention.”

Dr. Glenn and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Lateral neck dissection for thyroid cancer is associated with significant early postoperative morbidity of 20%, even in the hands of experienced endocrine surgeons at a high-volume medical center.

Among 99 procedures, 20 patients had 26 complications, including surgical site infection in 10, chyle leak in 7, spinal accessory nerve dysfunction in 7, and seroma in 2.

Long-term complications were rare, however, occurring in just one patient with a spinal accessory nerve injury, Dr. Jason A. Glenn said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Using a prospectively collected thyroid database, the investigators reviewed 96 patients who underwent lateral neck dissection (LND) for suspicion of initial or recurrent lateral neck metastases by one of four experienced endocrine surgeons at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Three patients had reoperations during the study period of February 2009 and June 2014, resulting in 99 procedures and 198 lateral necks evaluated preoperatively. Most patients were women (73%) and their median age was 45 years.

LND was performed on 127 necks and metastatic disease was confirmed in 111 (87%). This included all 82 patients who had positive preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA), 25 of 37 patients operated on without FNA, and 4 of 8 patients with a negative or nondiagnostic FNA, Dr. Glenn said.

The median number of lymph nodes excised was 22 (range 1-122), with a median of 3 (range 0-39) malignant nodes per lateral neck.

“FNA is an important adjunct in the preoperative evaluation, especially when it returns a positive result,” he said. “However, when FNA is negative, not available, or not performed, you really must consider the entire clinical picture, as 64% of these patients were found to have lymph node metastases in our study.”

Surgical drains were placed in 94% of the 127 lateral neck dissections and remained in place for a median of 6 days. The median length of stay was 1 day.

There was no association between drain duration and surgical site infection, although chyle leak was associated with a significantly longer median drain duration (12 days vs. 6 days; P value < .01), Dr. Glenn said.

Two of the seven patients with chyle leak, defined by drain output that was milky white and/or exceeded 1,000 cc in 24 hours, underwent reoperation with ligation of the cervical thoracic duct and fibrin sealant application. Both leaks resolved and patients were discharge on postoperative day 2.

“Surgical drains allow for early leak recognition and monitoring of leak resolution,” he said. “Most of these complications were diagnosed and managed on an outpatient basis, highlighting the importance of continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient setting for the treatment of thyroid cancer.”

Discussant Janice L. Pasieka, head of general surgery and a clinical professor of surgery and oncology at the University of Calgary (Alberta), said the retrospective review is a very valuable contribution to the literature because of its comprehensive follow-up.

“Today, most patients with this type of procedure are discharged within the 23 hours, and as such, complications such as nerve palsies, chyle leaks, and surgical site infections are not apparent for the majority of patients during their hospital stay,” Dr. Pasieka said. “Many times, the true incidences are lost unless the patient re-presents to the health care system, thus introducing your bias of only those significant enough to require intervention.”

Dr. Glenn and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Lateral neck dissection for thyroid cancer is associated with significant early postoperative morbidity of 20%, even in the hands of experienced endocrine surgeons at a high-volume medical center.

Among 99 procedures, 20 patients had 26 complications, including surgical site infection in 10, chyle leak in 7, spinal accessory nerve dysfunction in 7, and seroma in 2.

Long-term complications were rare, however, occurring in just one patient with a spinal accessory nerve injury, Dr. Jason A. Glenn said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Using a prospectively collected thyroid database, the investigators reviewed 96 patients who underwent lateral neck dissection (LND) for suspicion of initial or recurrent lateral neck metastases by one of four experienced endocrine surgeons at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Three patients had reoperations during the study period of February 2009 and June 2014, resulting in 99 procedures and 198 lateral necks evaluated preoperatively. Most patients were women (73%) and their median age was 45 years.

LND was performed on 127 necks and metastatic disease was confirmed in 111 (87%). This included all 82 patients who had positive preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA), 25 of 37 patients operated on without FNA, and 4 of 8 patients with a negative or nondiagnostic FNA, Dr. Glenn said.

The median number of lymph nodes excised was 22 (range 1-122), with a median of 3 (range 0-39) malignant nodes per lateral neck.

“FNA is an important adjunct in the preoperative evaluation, especially when it returns a positive result,” he said. “However, when FNA is negative, not available, or not performed, you really must consider the entire clinical picture, as 64% of these patients were found to have lymph node metastases in our study.”

Surgical drains were placed in 94% of the 127 lateral neck dissections and remained in place for a median of 6 days. The median length of stay was 1 day.

There was no association between drain duration and surgical site infection, although chyle leak was associated with a significantly longer median drain duration (12 days vs. 6 days; P value < .01), Dr. Glenn said.

Two of the seven patients with chyle leak, defined by drain output that was milky white and/or exceeded 1,000 cc in 24 hours, underwent reoperation with ligation of the cervical thoracic duct and fibrin sealant application. Both leaks resolved and patients were discharge on postoperative day 2.

“Surgical drains allow for early leak recognition and monitoring of leak resolution,” he said. “Most of these complications were diagnosed and managed on an outpatient basis, highlighting the importance of continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient setting for the treatment of thyroid cancer.”

Discussant Janice L. Pasieka, head of general surgery and a clinical professor of surgery and oncology at the University of Calgary (Alberta), said the retrospective review is a very valuable contribution to the literature because of its comprehensive follow-up.

“Today, most patients with this type of procedure are discharged within the 23 hours, and as such, complications such as nerve palsies, chyle leaks, and surgical site infections are not apparent for the majority of patients during their hospital stay,” Dr. Pasieka said. “Many times, the true incidences are lost unless the patient re-presents to the health care system, thus introducing your bias of only those significant enough to require intervention.”

Dr. Glenn and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer are associated with high early morbidity but few long-term complications.

Major finding: The overall complication rate was 20%, however, most were transient.

Data source: Retrospective observational series of 96 patients undergoing lateral neck dissection.

Disclosures: Dr. Glenn and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

HALS and LAP colectomy each offer unique benefits

CHICAGO – A nationwide analysis comparing straight versus hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy appears to have resulted in a draw.

Despite being used more commonly in patients with higher body mass index and comorbidities, hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) resulted in a significantly shorter operative time than did straight laparoscopic surgery (LAP) (171 minutes vs. 178.8 minutes; P < .001).

On the other hand, LAP was associated with a significantly shorter length of stay (5.9 days vs. 6.0 days; P < .001), fewer complications (15.9% vs. 18.2%; P = .006), fewer specifically superficial skin infections (4.1% vs. 5.4%; P = .007), and less prolonged postoperative ileus (7.5% vs. 9.1%; P = .01).

The differences were statistically significant likely because of the high volume of patients in each group, but are unlikely to be clinically significant in terms of patient care, senior study author Dr. I. Emre Gorgun said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

CSA incoming president Dr. Scott A. Gruber, chief of staff at the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, agreed. “There were very, very small differences. I think they were trying to show that the two [approaches] are virtually equivalent,” he said in an interview. “Each has its advantages and disadvantages, but the HALS technique was used in more complex, more high-risk patients,” Dr. Gruber said.

HALS bridges the learning gap between open and straight laparoscopic surgery, which has been slow to gain adoption in colorectal surgery because it is technically demanding and has a steep learning curve, said Dr. Gorgun, a colorectal surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. HALS allows surgeons to regain tactile sensation and manual retraction, enabling them to perform even more complex operations more effectively.

Studies also suggest that HALS reduces conversion rates and preserves the short-term benefits of LAP, though a nationwide comparison of short-term outcomes using the two techniques has been absent.

To fill this knowledge gap, the investigators used the 2012 colectomy-targeted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP

At baseline, the HALS group was significantly older than the LAP group (61.5 years vs. 60 years), had a higher body mass index (28.6 kg/m2 vs. 28 kg/m2), was more likely to be hypertensive (49.8% vs. 45.1%), and to be American Society of Anesthesiologists class III (42% vs. 37.4%) and class IV (2.8% vs. 2.7%). Steroid use for inflammatory bowel disease was significantly higher in the LAP group (6.5% vs. 5.4%).

Mortality rates were similar in the LAP and HALS groups (0.52% vs. 0.50%; P = .94), Dr. Gorgun reported.

Multivariate logistic regression adjusted for comorbid conditions lessened the degree of differences between the two groups, but continued to favor HALS for shorter operative time (odds ratio, 0.94) and favor LAP for shorter hospital stays (OR, 1.05) and less superficial surgical site infections (OR, 1.31), less prolonged post-operative ileus (OR, 1.25), and overall morbidity (OR, 1.16).

“Both LAP and HALS approaches are used in minimally invasive colorectal surgery based on their respective contributions and complement each other,” Dr. Gorgun concluded. “Implementing the best approach to decrease postoperative complication rates and increase use of MIS [minimally invasive surgery] will play a role in improving patient care and overall quality of health care.”

Dr. Gorgun, his coauthors, and Dr. Gruber reported having no financial conflicts

CHICAGO – A nationwide analysis comparing straight versus hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy appears to have resulted in a draw.

Despite being used more commonly in patients with higher body mass index and comorbidities, hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) resulted in a significantly shorter operative time than did straight laparoscopic surgery (LAP) (171 minutes vs. 178.8 minutes; P < .001).

On the other hand, LAP was associated with a significantly shorter length of stay (5.9 days vs. 6.0 days; P < .001), fewer complications (15.9% vs. 18.2%; P = .006), fewer specifically superficial skin infections (4.1% vs. 5.4%; P = .007), and less prolonged postoperative ileus (7.5% vs. 9.1%; P = .01).

The differences were statistically significant likely because of the high volume of patients in each group, but are unlikely to be clinically significant in terms of patient care, senior study author Dr. I. Emre Gorgun said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

CSA incoming president Dr. Scott A. Gruber, chief of staff at the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, agreed. “There were very, very small differences. I think they were trying to show that the two [approaches] are virtually equivalent,” he said in an interview. “Each has its advantages and disadvantages, but the HALS technique was used in more complex, more high-risk patients,” Dr. Gruber said.

HALS bridges the learning gap between open and straight laparoscopic surgery, which has been slow to gain adoption in colorectal surgery because it is technically demanding and has a steep learning curve, said Dr. Gorgun, a colorectal surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. HALS allows surgeons to regain tactile sensation and manual retraction, enabling them to perform even more complex operations more effectively.

Studies also suggest that HALS reduces conversion rates and preserves the short-term benefits of LAP, though a nationwide comparison of short-term outcomes using the two techniques has been absent.

To fill this knowledge gap, the investigators used the 2012 colectomy-targeted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP

At baseline, the HALS group was significantly older than the LAP group (61.5 years vs. 60 years), had a higher body mass index (28.6 kg/m2 vs. 28 kg/m2), was more likely to be hypertensive (49.8% vs. 45.1%), and to be American Society of Anesthesiologists class III (42% vs. 37.4%) and class IV (2.8% vs. 2.7%). Steroid use for inflammatory bowel disease was significantly higher in the LAP group (6.5% vs. 5.4%).

Mortality rates were similar in the LAP and HALS groups (0.52% vs. 0.50%; P = .94), Dr. Gorgun reported.

Multivariate logistic regression adjusted for comorbid conditions lessened the degree of differences between the two groups, but continued to favor HALS for shorter operative time (odds ratio, 0.94) and favor LAP for shorter hospital stays (OR, 1.05) and less superficial surgical site infections (OR, 1.31), less prolonged post-operative ileus (OR, 1.25), and overall morbidity (OR, 1.16).

“Both LAP and HALS approaches are used in minimally invasive colorectal surgery based on their respective contributions and complement each other,” Dr. Gorgun concluded. “Implementing the best approach to decrease postoperative complication rates and increase use of MIS [minimally invasive surgery] will play a role in improving patient care and overall quality of health care.”

Dr. Gorgun, his coauthors, and Dr. Gruber reported having no financial conflicts

CHICAGO – A nationwide analysis comparing straight versus hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy appears to have resulted in a draw.

Despite being used more commonly in patients with higher body mass index and comorbidities, hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) resulted in a significantly shorter operative time than did straight laparoscopic surgery (LAP) (171 minutes vs. 178.8 minutes; P < .001).

On the other hand, LAP was associated with a significantly shorter length of stay (5.9 days vs. 6.0 days; P < .001), fewer complications (15.9% vs. 18.2%; P = .006), fewer specifically superficial skin infections (4.1% vs. 5.4%; P = .007), and less prolonged postoperative ileus (7.5% vs. 9.1%; P = .01).

The differences were statistically significant likely because of the high volume of patients in each group, but are unlikely to be clinically significant in terms of patient care, senior study author Dr. I. Emre Gorgun said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

CSA incoming president Dr. Scott A. Gruber, chief of staff at the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, agreed. “There were very, very small differences. I think they were trying to show that the two [approaches] are virtually equivalent,” he said in an interview. “Each has its advantages and disadvantages, but the HALS technique was used in more complex, more high-risk patients,” Dr. Gruber said.

HALS bridges the learning gap between open and straight laparoscopic surgery, which has been slow to gain adoption in colorectal surgery because it is technically demanding and has a steep learning curve, said Dr. Gorgun, a colorectal surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic. HALS allows surgeons to regain tactile sensation and manual retraction, enabling them to perform even more complex operations more effectively.

Studies also suggest that HALS reduces conversion rates and preserves the short-term benefits of LAP, though a nationwide comparison of short-term outcomes using the two techniques has been absent.

To fill this knowledge gap, the investigators used the 2012 colectomy-targeted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP

At baseline, the HALS group was significantly older than the LAP group (61.5 years vs. 60 years), had a higher body mass index (28.6 kg/m2 vs. 28 kg/m2), was more likely to be hypertensive (49.8% vs. 45.1%), and to be American Society of Anesthesiologists class III (42% vs. 37.4%) and class IV (2.8% vs. 2.7%). Steroid use for inflammatory bowel disease was significantly higher in the LAP group (6.5% vs. 5.4%).

Mortality rates were similar in the LAP and HALS groups (0.52% vs. 0.50%; P = .94), Dr. Gorgun reported.

Multivariate logistic regression adjusted for comorbid conditions lessened the degree of differences between the two groups, but continued to favor HALS for shorter operative time (odds ratio, 0.94) and favor LAP for shorter hospital stays (OR, 1.05) and less superficial surgical site infections (OR, 1.31), less prolonged post-operative ileus (OR, 1.25), and overall morbidity (OR, 1.16).

“Both LAP and HALS approaches are used in minimally invasive colorectal surgery based on their respective contributions and complement each other,” Dr. Gorgun concluded. “Implementing the best approach to decrease postoperative complication rates and increase use of MIS [minimally invasive surgery] will play a role in improving patient care and overall quality of health care.”

Dr. Gorgun, his coauthors, and Dr. Gruber reported having no financial conflicts

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Straight and hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy offer unique benefits, and HALS is a good option in more complex patients.

Major finding: Surgery was 7 minutes shorter with HALS, while complications were down 2.3% with LAP.

Data source: Retrospective study of 7,843 patients undergoing colectomy in the ACS NSQIP database.

Disclosures: Dr. Gorgun, his coauthors, and Dr. Gruber reported having no financial conflicts.

Double bubble: Concomitant hernia repair and bariatric surgery

CHICAGO – Combining hiatal hernia repair with bariatric surgery is feasible and safe, with no intraoperative complications or deaths reported in a series of 83 patients.

“Concomitant repair of hiatal hernia during these operations can be technically challenging but is a more efficient way of handling this pathology than undergoing separate procedures,” study author Dr. John Rodriguez, from the Cleveland Clinic, said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The presence of a hiatal hernia can play an important role when sizing a pouch or performing a dissection and can make it difficult to have consistent outcomes or gastric sleeves if the complete stomach can’t be visualized, he explained. Hernias can prevent weight gain but also prevent resolution of reflux symptoms.

Prospectively collected data from 83 patients who underwent concomitant hernia repair and bariatric surgery were retrospectively, compared with 83 historic controls who underwent bariatric surgery alone. The two groups were well-matched with regard to age (57.2 years vs. 56.2 years), weight (118.4 kg vs. 119.9 kg), and body mass index (BMI) (44.5 kg/m2vs. 44.6 kg/m2), although diabetes was significantly more common in controls (13.2% vs. 38.5%).

In the study group, hernias were classified as Type I in 47 patients, Type II in 5, Type III in 28, and Type IV in 3. Primary hernia repair was performed in all patients, using anterior reconstruction in 45, posterior reconstruction in 21, posterior reconstruction plus mesh in 7, and an unspecified approach in 10.

Operative time was slightly longer with the addition of hernia repair, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (164.4 minutes vs. 147.5 minutes; P = .07), Dr. Rodriguez said. Average hospital length of stay was nearly identical at 3.5 vs. 3.4 days (P = .09).

In all, 24 patients undergoing concomitant surgery described having early postoperative symptoms such as nausea, dysphagia, abdominal pain, reflux, and dehydration, compared with 15 controls. But, again the difference was not significant (33.7% vs. 18%; P = .09), he said.

Three study patients had late postoperative complications after 1 year requiring esophagogastroduodenoscopy caused by one each of stenosis, hernia recurrence, and marginal ulcer. Among controls, there were four late marginal ulcers and two stenoses (P = .3).

Notably, hiatal hernia was diagnosed intraoperatively in a full 61.4% of the study group. Obesity is an established risk factor for hiatal hernia, although many patients who present for bariatric surgery are asymptomatic, Dr. Rodriguez observed.

At 12 months, patients undergoing bariatric surgery with and without concomitant hernia repair had similar weight loss (80.7 kg vs. 87.4 kg; P = .1) and final BMI (30 kg/m2 vs. 32.5 kg/m2; P = .06).

Use of antireflux medication, however, was significantly higher in those without concomitant surgery (38.5% vs. 43.7%; P = .01), he said. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms were present in 84.3% of study patients and 77% of controls at baseline.

Antireflux medication use declined in 66% of patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux en-Y gastric bypass vs. 50% undergoing only laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surgical approach did not affect weight loss (59.7 kg vs. 51.8 kg) or final BMI (30.3 kg/m2 vs. 32.4 kg/m2).

“The true incidence of hiatal hernia in the obese is likely underestimated,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “Concomitant repair is safe and may prevent further symptoms.”

Limitations of the study were the small, retrospective cohort, a lack of standardized GERD symptom scoring and objective GERD testing, and no uniform hiatal hernia repair. Standardized approaches may improve outcomes during combined procedures, he said.

During a discussion of the results, Dr. Peter T. Hallowell, an audience member from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, rose to say this is “information we urgently need in bariatric surgery.”

Dr. Rodriguez and his coauthors reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Combining hiatal hernia repair with bariatric surgery is feasible and safe, with no intraoperative complications or deaths reported in a series of 83 patients.

“Concomitant repair of hiatal hernia during these operations can be technically challenging but is a more efficient way of handling this pathology than undergoing separate procedures,” study author Dr. John Rodriguez, from the Cleveland Clinic, said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The presence of a hiatal hernia can play an important role when sizing a pouch or performing a dissection and can make it difficult to have consistent outcomes or gastric sleeves if the complete stomach can’t be visualized, he explained. Hernias can prevent weight gain but also prevent resolution of reflux symptoms.

Prospectively collected data from 83 patients who underwent concomitant hernia repair and bariatric surgery were retrospectively, compared with 83 historic controls who underwent bariatric surgery alone. The two groups were well-matched with regard to age (57.2 years vs. 56.2 years), weight (118.4 kg vs. 119.9 kg), and body mass index (BMI) (44.5 kg/m2vs. 44.6 kg/m2), although diabetes was significantly more common in controls (13.2% vs. 38.5%).

In the study group, hernias were classified as Type I in 47 patients, Type II in 5, Type III in 28, and Type IV in 3. Primary hernia repair was performed in all patients, using anterior reconstruction in 45, posterior reconstruction in 21, posterior reconstruction plus mesh in 7, and an unspecified approach in 10.

Operative time was slightly longer with the addition of hernia repair, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (164.4 minutes vs. 147.5 minutes; P = .07), Dr. Rodriguez said. Average hospital length of stay was nearly identical at 3.5 vs. 3.4 days (P = .09).

In all, 24 patients undergoing concomitant surgery described having early postoperative symptoms such as nausea, dysphagia, abdominal pain, reflux, and dehydration, compared with 15 controls. But, again the difference was not significant (33.7% vs. 18%; P = .09), he said.

Three study patients had late postoperative complications after 1 year requiring esophagogastroduodenoscopy caused by one each of stenosis, hernia recurrence, and marginal ulcer. Among controls, there were four late marginal ulcers and two stenoses (P = .3).

Notably, hiatal hernia was diagnosed intraoperatively in a full 61.4% of the study group. Obesity is an established risk factor for hiatal hernia, although many patients who present for bariatric surgery are asymptomatic, Dr. Rodriguez observed.

At 12 months, patients undergoing bariatric surgery with and without concomitant hernia repair had similar weight loss (80.7 kg vs. 87.4 kg; P = .1) and final BMI (30 kg/m2 vs. 32.5 kg/m2; P = .06).

Use of antireflux medication, however, was significantly higher in those without concomitant surgery (38.5% vs. 43.7%; P = .01), he said. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms were present in 84.3% of study patients and 77% of controls at baseline.

Antireflux medication use declined in 66% of patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux en-Y gastric bypass vs. 50% undergoing only laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surgical approach did not affect weight loss (59.7 kg vs. 51.8 kg) or final BMI (30.3 kg/m2 vs. 32.4 kg/m2).

“The true incidence of hiatal hernia in the obese is likely underestimated,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “Concomitant repair is safe and may prevent further symptoms.”

Limitations of the study were the small, retrospective cohort, a lack of standardized GERD symptom scoring and objective GERD testing, and no uniform hiatal hernia repair. Standardized approaches may improve outcomes during combined procedures, he said.

During a discussion of the results, Dr. Peter T. Hallowell, an audience member from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, rose to say this is “information we urgently need in bariatric surgery.”

Dr. Rodriguez and his coauthors reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Combining hiatal hernia repair with bariatric surgery is feasible and safe, with no intraoperative complications or deaths reported in a series of 83 patients.

“Concomitant repair of hiatal hernia during these operations can be technically challenging but is a more efficient way of handling this pathology than undergoing separate procedures,” study author Dr. John Rodriguez, from the Cleveland Clinic, said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The presence of a hiatal hernia can play an important role when sizing a pouch or performing a dissection and can make it difficult to have consistent outcomes or gastric sleeves if the complete stomach can’t be visualized, he explained. Hernias can prevent weight gain but also prevent resolution of reflux symptoms.

Prospectively collected data from 83 patients who underwent concomitant hernia repair and bariatric surgery were retrospectively, compared with 83 historic controls who underwent bariatric surgery alone. The two groups were well-matched with regard to age (57.2 years vs. 56.2 years), weight (118.4 kg vs. 119.9 kg), and body mass index (BMI) (44.5 kg/m2vs. 44.6 kg/m2), although diabetes was significantly more common in controls (13.2% vs. 38.5%).

In the study group, hernias were classified as Type I in 47 patients, Type II in 5, Type III in 28, and Type IV in 3. Primary hernia repair was performed in all patients, using anterior reconstruction in 45, posterior reconstruction in 21, posterior reconstruction plus mesh in 7, and an unspecified approach in 10.

Operative time was slightly longer with the addition of hernia repair, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (164.4 minutes vs. 147.5 minutes; P = .07), Dr. Rodriguez said. Average hospital length of stay was nearly identical at 3.5 vs. 3.4 days (P = .09).

In all, 24 patients undergoing concomitant surgery described having early postoperative symptoms such as nausea, dysphagia, abdominal pain, reflux, and dehydration, compared with 15 controls. But, again the difference was not significant (33.7% vs. 18%; P = .09), he said.

Three study patients had late postoperative complications after 1 year requiring esophagogastroduodenoscopy caused by one each of stenosis, hernia recurrence, and marginal ulcer. Among controls, there were four late marginal ulcers and two stenoses (P = .3).

Notably, hiatal hernia was diagnosed intraoperatively in a full 61.4% of the study group. Obesity is an established risk factor for hiatal hernia, although many patients who present for bariatric surgery are asymptomatic, Dr. Rodriguez observed.

At 12 months, patients undergoing bariatric surgery with and without concomitant hernia repair had similar weight loss (80.7 kg vs. 87.4 kg; P = .1) and final BMI (30 kg/m2 vs. 32.5 kg/m2; P = .06).

Use of antireflux medication, however, was significantly higher in those without concomitant surgery (38.5% vs. 43.7%; P = .01), he said. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms were present in 84.3% of study patients and 77% of controls at baseline.

Antireflux medication use declined in 66% of patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux en-Y gastric bypass vs. 50% undergoing only laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surgical approach did not affect weight loss (59.7 kg vs. 51.8 kg) or final BMI (30.3 kg/m2 vs. 32.4 kg/m2).

“The true incidence of hiatal hernia in the obese is likely underestimated,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “Concomitant repair is safe and may prevent further symptoms.”

Limitations of the study were the small, retrospective cohort, a lack of standardized GERD symptom scoring and objective GERD testing, and no uniform hiatal hernia repair. Standardized approaches may improve outcomes during combined procedures, he said.

During a discussion of the results, Dr. Peter T. Hallowell, an audience member from the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, rose to say this is “information we urgently need in bariatric surgery.”

Dr. Rodriguez and his coauthors reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Hiatal hernia repair during bariatric surgery is feasible and safe.

Major finding: Concomitant hernia repair added 16.9 minutes to surgery, but did not significantly increase short- or long-term complications.

Data source: Retrospective study of 83 patients undergoing hiatal hernia repair during bariatric surgery and 83 historic controls.

Disclosures: Dr. Rodriguez and his coauthors reported having no financial conflicts.

Acute diverticulitis: Call in the surgical specialist, or maybe not?

CHICAGO – Surgical outcomes of acute, complicated diverticulitis are equivalent regardless of whether a colorectal or general surgeon wields the scalpel, a multicenter study showed.

There was no difference between the colorectal surgery (CRS) and general surgery groups for the primary outcomes of 90-day morbidity (26% vs 28%; P = .76), readmission (32% vs. 25%; P = .48), and length of stay (both median 9 days; P = .82).

Surgeon specialization was not associated with any of the outcomes in multivariate regression that accounted for patient demographics, surgeon type, and disease characteristics, study author Capt. G. Paul Wright, U.S. Army Reserve Medical Corps, reported at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

The authors tackled the controversial issue in light of recent data suggesting improved acute, complicated diverticulitis surgery outcomes in the hands of specialized surgeons. A 2014 study reported that colorectal surgeons were less likely than general surgeons to use a Hartmann’s procedure and had reduced LOS and time to stoma reversal (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:1156-61).

The current analysis involved 115 consecutive patients with acute, complicated diverticulitis who underwent emergent surgery with either a colorectal surgeon (n = 62) or general surgeon (n = 53) at two university-affiliated hospitals from 2006 to 2013. Age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and American Society of Anesthesiologists class were similar between groups.

The colorectal surgeon group (CRS), however, was significantly more likely to have had previous episodes of diverticulitis (58% vs. 25%; P < .001), likely representing a referral bias or preexisting relationship with their surgeon, Dr. Wright said.

The general surgeon (GS) group had a significantly higher number of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria (P = .009 for all groups), higher rates of Hinchey class 3 disease (59% vs. 32%: P = .02), and ICU admissions (25% vs. 7%; P = .006).

The most common procedure among general surgeons was a Hartmann’s procedure (64% vs. 34%; P < .001), whereas colorectal surgeons favored primary anastomosis with diverting ileostomy (45% vs. 0%; P < .001), Dr. Wright, from Grand Rapids Medical Education Partners and Michigan State University, both in Grand Rapids, reported.