User login

Resective epilepsy surgery found OK in septuagenarians

HOUSTON – With careful selection, patients in their 70s with refractory epilepsy may be offered resective epilepsy surgery, results from a small single-center study demonstrated.

The findings “were a surprise to us,” lead study author Ahmed Abdelkader, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We expected that complications would be higher because this is a vulnerable age group with multiple comorbidities.”

Dr. Abdelkader and his associates searched the database of the Cleveland Clinic Epilepsy Center to identify patients aged 70 years and older who underwent respective epilepsy surgery between Jan. 1, 2000, and Sept. 30, 2015. They limited the analysis to seven patients who had at least one year of post-surgical follow-up. The mean age of the patients at surgery was 73 and the age of epilepsy onset ranged from 24-71 years, with a monthly frequency of 4.2 seizures. Their mean Charlson Combined Comorbidity Index score was 4, which translated into a 10-year mean survival probability of 53%. Four of the patients (57%) had a history of significant injuries due to seizures, while all but one had a positive MRI. Three of the patients had hippocampal sclerosis, “which is unique because most cases of hippocampal sclerosis are in younger age groups,” said Dr. Abdelkader, who is currently a research fellow at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland.

All patients underwent anterior temporal lobectomy, four on the left side. None had a surgical complication. Six of the seven patients had a good surgical outcome, defined as a Class I or II on the Engel Epilepsy Surgery Outcome Scale, with four being completed free of seizures at one year of follow-up. One of the patients underwent two respective epilepsy surgeries: the first at age 72 and the second at age 75. He died of natural causes, 11 years after his first surgery, and was the only patient to pass away during the follow-up period.

In their abstract, the researchers called for future multi-center collaborative studies “to prospectively study factors influencing respective epilepsy surgery recommendation and its outcome in this rapidly growing population.”

Dr. Abdelkader reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – With careful selection, patients in their 70s with refractory epilepsy may be offered resective epilepsy surgery, results from a small single-center study demonstrated.

The findings “were a surprise to us,” lead study author Ahmed Abdelkader, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We expected that complications would be higher because this is a vulnerable age group with multiple comorbidities.”

Dr. Abdelkader and his associates searched the database of the Cleveland Clinic Epilepsy Center to identify patients aged 70 years and older who underwent respective epilepsy surgery between Jan. 1, 2000, and Sept. 30, 2015. They limited the analysis to seven patients who had at least one year of post-surgical follow-up. The mean age of the patients at surgery was 73 and the age of epilepsy onset ranged from 24-71 years, with a monthly frequency of 4.2 seizures. Their mean Charlson Combined Comorbidity Index score was 4, which translated into a 10-year mean survival probability of 53%. Four of the patients (57%) had a history of significant injuries due to seizures, while all but one had a positive MRI. Three of the patients had hippocampal sclerosis, “which is unique because most cases of hippocampal sclerosis are in younger age groups,” said Dr. Abdelkader, who is currently a research fellow at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland.

All patients underwent anterior temporal lobectomy, four on the left side. None had a surgical complication. Six of the seven patients had a good surgical outcome, defined as a Class I or II on the Engel Epilepsy Surgery Outcome Scale, with four being completed free of seizures at one year of follow-up. One of the patients underwent two respective epilepsy surgeries: the first at age 72 and the second at age 75. He died of natural causes, 11 years after his first surgery, and was the only patient to pass away during the follow-up period.

In their abstract, the researchers called for future multi-center collaborative studies “to prospectively study factors influencing respective epilepsy surgery recommendation and its outcome in this rapidly growing population.”

Dr. Abdelkader reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – With careful selection, patients in their 70s with refractory epilepsy may be offered resective epilepsy surgery, results from a small single-center study demonstrated.

The findings “were a surprise to us,” lead study author Ahmed Abdelkader, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We expected that complications would be higher because this is a vulnerable age group with multiple comorbidities.”

Dr. Abdelkader and his associates searched the database of the Cleveland Clinic Epilepsy Center to identify patients aged 70 years and older who underwent respective epilepsy surgery between Jan. 1, 2000, and Sept. 30, 2015. They limited the analysis to seven patients who had at least one year of post-surgical follow-up. The mean age of the patients at surgery was 73 and the age of epilepsy onset ranged from 24-71 years, with a monthly frequency of 4.2 seizures. Their mean Charlson Combined Comorbidity Index score was 4, which translated into a 10-year mean survival probability of 53%. Four of the patients (57%) had a history of significant injuries due to seizures, while all but one had a positive MRI. Three of the patients had hippocampal sclerosis, “which is unique because most cases of hippocampal sclerosis are in younger age groups,” said Dr. Abdelkader, who is currently a research fellow at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland.

All patients underwent anterior temporal lobectomy, four on the left side. None had a surgical complication. Six of the seven patients had a good surgical outcome, defined as a Class I or II on the Engel Epilepsy Surgery Outcome Scale, with four being completed free of seizures at one year of follow-up. One of the patients underwent two respective epilepsy surgeries: the first at age 72 and the second at age 75. He died of natural causes, 11 years after his first surgery, and was the only patient to pass away during the follow-up period.

In their abstract, the researchers called for future multi-center collaborative studies “to prospectively study factors influencing respective epilepsy surgery recommendation and its outcome in this rapidly growing population.”

Dr. Abdelkader reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Six of the seven patients achieved good surgical outcome, with four being completed free of seizures at one year of follow-up.

Data source: A retrospective review of seven patients who underwent resective epilepsy surgery in their 70s.

Disclosures: Dr. Abdelkader reported having no financial disclosures.

Radiosurgery found not superior to open surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy

HOUSTON – Despite enrollment difficulties that limited the study, a recently completed randomized trial comparing radiosurgery with open lobectomy to treat temporal lobe epilepsy offers some guidance for patients and their physicians.

Radiosurgery’s noninferiority to open lobectomy couldn’t be shown from the ROSE (Radiosurgery or Open Surgery for Epilepsy) trial, but language deficits were similar – and quite small – by 3 years after either procedure. Expected visual field deficits were similar in each procedure as well. However, since the trial didn’t reach its target enrollment, several primary outcome measures could not be fully assessed.

On the face of it, radiosurgery has significant appeal. Although open resective surgery is effective, there’s still some risk of infection and blood loss, and neuropsychological changes as well as other focal neurologic deficits are seen. Still, the study saw many challenges, but the largest, according to the investigators, was in recruitment. “Patients like to choose,” said Nicholas M. Barbaro, MD, chair of the department of neurosurgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Dr. Barbaro, one of several ROSE coinvestigators who presented the study findings at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that if patients felt that lobectomy was the best choice, then there would be no incentive to enter a trial where they might be randomized to radiosurgery. Also, he said, some patients might be reluctant to be irradiated, fearing short-term or long-term toxicity.

Trial hypotheses and protocols

The ROSE trial aimed to show that stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) would not be inferior to anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) in achieving a seizure-free state by months 25-36 post procedure. The lag to response after radiosurgery is about 1 year; seizure freedom, defined as 12 consecutive months with no seizures, was assessed from months 25 to 36 of the study for the primary outcome of seizure freedom.

Investigators also hypothesized that fewer SRS patients would have significant reductions in measures of language function; further, they predicted that patients in both treatment arms would experience improvements in quality of life (QOL), and that QOL would improve as seizure freedom increased. Finally, the trial sought to show that SRS was cost effective, compared with ATL, with the marginal cost-utility ratio dropping below $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Patients in the ATL arm received a standard “Spencer” ATL, with adequacy of resection assessed by MRI performed 3 months after surgery. An inadequate resection would have been classified as an adverse event, but all ATL patients had an adequate resection by study criteria, and all those whose histopathology was available (n = 20) had some hippocampal sclerosis.

Patients in the SRS arm had the amygdala and anterior 2 cm of the hippocampus, as well as the adjacent parahippocampal gyrus, irradiated. This resulted in a total treatment volume ranging from 5.5 to 7.5 cc. Patients received 4 Gy to the 50% isodose line, and treatment could involve an unlimited number of isocenters. The brain stem could receive no more than 10 Gy and the optic nerve and chiasm no more than 8 Gy. All treatment plans were cleared by the ROSE steering committee. The SRS patients had some variation in dose and volumes treated, but all were within the approved limits of the study.

Trial outcomes

As expected, the surgery arm achieved rapid seizure remission, while the SRS arm saw a steady increase in seizure-free numbers beginning at about 12 months after surgery. During study months 25-36, 78% of the ATL arm and 52% of the SRS arm were seizure free. “The null hypothesis of inferiority of SRS was not rejected,” said Mark Quigg, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Most patients in both groups had no or minimal changes in verbal memory, with no significant differences between the groups at 36 months after treatment.

QOL measures improved rapidly for those who received open surgery, and more slowly for those in the radiosurgery arm, a pattern “consistent with the known association between improved seizure control and quality of life,” said John Langfitt, PhD, a neuropsychologist and professor of neurology and psychiatry at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). However, the study was underpowered to show noninferiority of SRS for QOL measures at 36 months.

“There was a preliminary trend toward reduced health care use over time in the open surgery arm,” said Dr. Langfitt, again noting that the earlier seizure control achieved in surgery reduced health care utilization for that group sooner than for the SRS group. “The power may be limited by sample size and the tendency of utilization to be highly skewed,” he said.

Also as expected, the ATL arm saw early surgery-related adverse events such as scalp wound infections, subdural hematomas, and deep vein thromboses. These were infrequent overall. In contrast, the SRS group saw more cerebral edema–related adverse events during months 9-18, with headaches, new neurologic deficits, and transient seizure exacerbation.

All but three patients received postoperative visual field testing. Of the patients receiving SRS, 34% (10 of 29) had an upper superior quadrant visual field defect, as did 42% (11 of 26) of patients in the ATL arm.

Since the primary treating surgeon and neurologist could not be blinded as to study arm, another neurologist who was blinded was responsible for assessing the outcome measures, and also could identify adverse events. The trial’s steering committee was also blinded to ongoing outcomes.

Pilot study results

A pilot study had previously found that SRS was comparable to the efficacy that had been seen in larger, prospective trials of open surgery, with about two-thirds of patients seizure free at 36 months. Although most patients experienced brief exacerbation of auras or complex partial seizures after radiosurgery, visual field defects were similar to those experienced by patients undergoing standard ATL. Overall, neuropsychological outcomes for those undergoing SRS in the pilot were good, with a low incidence of declines in language and verbal memory function of the dominant hemisphere, and no short-term affective changes were seen. SRS patients who were seizure free after the procedure experienced a significant improvement in QOL.

The promising pilot results contrasted with the limited findings of the ROSE study. In regard to seizure freedom in ROSE, said Dr. Quigg, “The data appear to show that radiosurgery is inferior to ATL, but the low power of the study means that we cannot conclude this with sufficient confidence. Nor can we conclude that the two treatments are noninferior.”

The study was partially funded by Elekta, the manufacturer of the Gamma Knife radiosurgery device used in the study. Dr. Barbaro reported no other disclosures. Dr. Langfitt reported being a consultant for Monteris. Dr. Quigg reported being an investigator for several antiepileptic drug trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Despite enrollment difficulties that limited the study, a recently completed randomized trial comparing radiosurgery with open lobectomy to treat temporal lobe epilepsy offers some guidance for patients and their physicians.

Radiosurgery’s noninferiority to open lobectomy couldn’t be shown from the ROSE (Radiosurgery or Open Surgery for Epilepsy) trial, but language deficits were similar – and quite small – by 3 years after either procedure. Expected visual field deficits were similar in each procedure as well. However, since the trial didn’t reach its target enrollment, several primary outcome measures could not be fully assessed.

On the face of it, radiosurgery has significant appeal. Although open resective surgery is effective, there’s still some risk of infection and blood loss, and neuropsychological changes as well as other focal neurologic deficits are seen. Still, the study saw many challenges, but the largest, according to the investigators, was in recruitment. “Patients like to choose,” said Nicholas M. Barbaro, MD, chair of the department of neurosurgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Dr. Barbaro, one of several ROSE coinvestigators who presented the study findings at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that if patients felt that lobectomy was the best choice, then there would be no incentive to enter a trial where they might be randomized to radiosurgery. Also, he said, some patients might be reluctant to be irradiated, fearing short-term or long-term toxicity.

Trial hypotheses and protocols

The ROSE trial aimed to show that stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) would not be inferior to anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) in achieving a seizure-free state by months 25-36 post procedure. The lag to response after radiosurgery is about 1 year; seizure freedom, defined as 12 consecutive months with no seizures, was assessed from months 25 to 36 of the study for the primary outcome of seizure freedom.

Investigators also hypothesized that fewer SRS patients would have significant reductions in measures of language function; further, they predicted that patients in both treatment arms would experience improvements in quality of life (QOL), and that QOL would improve as seizure freedom increased. Finally, the trial sought to show that SRS was cost effective, compared with ATL, with the marginal cost-utility ratio dropping below $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Patients in the ATL arm received a standard “Spencer” ATL, with adequacy of resection assessed by MRI performed 3 months after surgery. An inadequate resection would have been classified as an adverse event, but all ATL patients had an adequate resection by study criteria, and all those whose histopathology was available (n = 20) had some hippocampal sclerosis.

Patients in the SRS arm had the amygdala and anterior 2 cm of the hippocampus, as well as the adjacent parahippocampal gyrus, irradiated. This resulted in a total treatment volume ranging from 5.5 to 7.5 cc. Patients received 4 Gy to the 50% isodose line, and treatment could involve an unlimited number of isocenters. The brain stem could receive no more than 10 Gy and the optic nerve and chiasm no more than 8 Gy. All treatment plans were cleared by the ROSE steering committee. The SRS patients had some variation in dose and volumes treated, but all were within the approved limits of the study.

Trial outcomes

As expected, the surgery arm achieved rapid seizure remission, while the SRS arm saw a steady increase in seizure-free numbers beginning at about 12 months after surgery. During study months 25-36, 78% of the ATL arm and 52% of the SRS arm were seizure free. “The null hypothesis of inferiority of SRS was not rejected,” said Mark Quigg, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Most patients in both groups had no or minimal changes in verbal memory, with no significant differences between the groups at 36 months after treatment.

QOL measures improved rapidly for those who received open surgery, and more slowly for those in the radiosurgery arm, a pattern “consistent with the known association between improved seizure control and quality of life,” said John Langfitt, PhD, a neuropsychologist and professor of neurology and psychiatry at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). However, the study was underpowered to show noninferiority of SRS for QOL measures at 36 months.

“There was a preliminary trend toward reduced health care use over time in the open surgery arm,” said Dr. Langfitt, again noting that the earlier seizure control achieved in surgery reduced health care utilization for that group sooner than for the SRS group. “The power may be limited by sample size and the tendency of utilization to be highly skewed,” he said.

Also as expected, the ATL arm saw early surgery-related adverse events such as scalp wound infections, subdural hematomas, and deep vein thromboses. These were infrequent overall. In contrast, the SRS group saw more cerebral edema–related adverse events during months 9-18, with headaches, new neurologic deficits, and transient seizure exacerbation.

All but three patients received postoperative visual field testing. Of the patients receiving SRS, 34% (10 of 29) had an upper superior quadrant visual field defect, as did 42% (11 of 26) of patients in the ATL arm.

Since the primary treating surgeon and neurologist could not be blinded as to study arm, another neurologist who was blinded was responsible for assessing the outcome measures, and also could identify adverse events. The trial’s steering committee was also blinded to ongoing outcomes.

Pilot study results

A pilot study had previously found that SRS was comparable to the efficacy that had been seen in larger, prospective trials of open surgery, with about two-thirds of patients seizure free at 36 months. Although most patients experienced brief exacerbation of auras or complex partial seizures after radiosurgery, visual field defects were similar to those experienced by patients undergoing standard ATL. Overall, neuropsychological outcomes for those undergoing SRS in the pilot were good, with a low incidence of declines in language and verbal memory function of the dominant hemisphere, and no short-term affective changes were seen. SRS patients who were seizure free after the procedure experienced a significant improvement in QOL.

The promising pilot results contrasted with the limited findings of the ROSE study. In regard to seizure freedom in ROSE, said Dr. Quigg, “The data appear to show that radiosurgery is inferior to ATL, but the low power of the study means that we cannot conclude this with sufficient confidence. Nor can we conclude that the two treatments are noninferior.”

The study was partially funded by Elekta, the manufacturer of the Gamma Knife radiosurgery device used in the study. Dr. Barbaro reported no other disclosures. Dr. Langfitt reported being a consultant for Monteris. Dr. Quigg reported being an investigator for several antiepileptic drug trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Despite enrollment difficulties that limited the study, a recently completed randomized trial comparing radiosurgery with open lobectomy to treat temporal lobe epilepsy offers some guidance for patients and their physicians.

Radiosurgery’s noninferiority to open lobectomy couldn’t be shown from the ROSE (Radiosurgery or Open Surgery for Epilepsy) trial, but language deficits were similar – and quite small – by 3 years after either procedure. Expected visual field deficits were similar in each procedure as well. However, since the trial didn’t reach its target enrollment, several primary outcome measures could not be fully assessed.

On the face of it, radiosurgery has significant appeal. Although open resective surgery is effective, there’s still some risk of infection and blood loss, and neuropsychological changes as well as other focal neurologic deficits are seen. Still, the study saw many challenges, but the largest, according to the investigators, was in recruitment. “Patients like to choose,” said Nicholas M. Barbaro, MD, chair of the department of neurosurgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Dr. Barbaro, one of several ROSE coinvestigators who presented the study findings at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, noted that if patients felt that lobectomy was the best choice, then there would be no incentive to enter a trial where they might be randomized to radiosurgery. Also, he said, some patients might be reluctant to be irradiated, fearing short-term or long-term toxicity.

Trial hypotheses and protocols

The ROSE trial aimed to show that stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) would not be inferior to anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) in achieving a seizure-free state by months 25-36 post procedure. The lag to response after radiosurgery is about 1 year; seizure freedom, defined as 12 consecutive months with no seizures, was assessed from months 25 to 36 of the study for the primary outcome of seizure freedom.

Investigators also hypothesized that fewer SRS patients would have significant reductions in measures of language function; further, they predicted that patients in both treatment arms would experience improvements in quality of life (QOL), and that QOL would improve as seizure freedom increased. Finally, the trial sought to show that SRS was cost effective, compared with ATL, with the marginal cost-utility ratio dropping below $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Patients in the ATL arm received a standard “Spencer” ATL, with adequacy of resection assessed by MRI performed 3 months after surgery. An inadequate resection would have been classified as an adverse event, but all ATL patients had an adequate resection by study criteria, and all those whose histopathology was available (n = 20) had some hippocampal sclerosis.

Patients in the SRS arm had the amygdala and anterior 2 cm of the hippocampus, as well as the adjacent parahippocampal gyrus, irradiated. This resulted in a total treatment volume ranging from 5.5 to 7.5 cc. Patients received 4 Gy to the 50% isodose line, and treatment could involve an unlimited number of isocenters. The brain stem could receive no more than 10 Gy and the optic nerve and chiasm no more than 8 Gy. All treatment plans were cleared by the ROSE steering committee. The SRS patients had some variation in dose and volumes treated, but all were within the approved limits of the study.

Trial outcomes

As expected, the surgery arm achieved rapid seizure remission, while the SRS arm saw a steady increase in seizure-free numbers beginning at about 12 months after surgery. During study months 25-36, 78% of the ATL arm and 52% of the SRS arm were seizure free. “The null hypothesis of inferiority of SRS was not rejected,” said Mark Quigg, MD, professor of neurology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Most patients in both groups had no or minimal changes in verbal memory, with no significant differences between the groups at 36 months after treatment.

QOL measures improved rapidly for those who received open surgery, and more slowly for those in the radiosurgery arm, a pattern “consistent with the known association between improved seizure control and quality of life,” said John Langfitt, PhD, a neuropsychologist and professor of neurology and psychiatry at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). However, the study was underpowered to show noninferiority of SRS for QOL measures at 36 months.

“There was a preliminary trend toward reduced health care use over time in the open surgery arm,” said Dr. Langfitt, again noting that the earlier seizure control achieved in surgery reduced health care utilization for that group sooner than for the SRS group. “The power may be limited by sample size and the tendency of utilization to be highly skewed,” he said.

Also as expected, the ATL arm saw early surgery-related adverse events such as scalp wound infections, subdural hematomas, and deep vein thromboses. These were infrequent overall. In contrast, the SRS group saw more cerebral edema–related adverse events during months 9-18, with headaches, new neurologic deficits, and transient seizure exacerbation.

All but three patients received postoperative visual field testing. Of the patients receiving SRS, 34% (10 of 29) had an upper superior quadrant visual field defect, as did 42% (11 of 26) of patients in the ATL arm.

Since the primary treating surgeon and neurologist could not be blinded as to study arm, another neurologist who was blinded was responsible for assessing the outcome measures, and also could identify adverse events. The trial’s steering committee was also blinded to ongoing outcomes.

Pilot study results

A pilot study had previously found that SRS was comparable to the efficacy that had been seen in larger, prospective trials of open surgery, with about two-thirds of patients seizure free at 36 months. Although most patients experienced brief exacerbation of auras or complex partial seizures after radiosurgery, visual field defects were similar to those experienced by patients undergoing standard ATL. Overall, neuropsychological outcomes for those undergoing SRS in the pilot were good, with a low incidence of declines in language and verbal memory function of the dominant hemisphere, and no short-term affective changes were seen. SRS patients who were seizure free after the procedure experienced a significant improvement in QOL.

The promising pilot results contrasted with the limited findings of the ROSE study. In regard to seizure freedom in ROSE, said Dr. Quigg, “The data appear to show that radiosurgery is inferior to ATL, but the low power of the study means that we cannot conclude this with sufficient confidence. Nor can we conclude that the two treatments are noninferior.”

The study was partially funded by Elekta, the manufacturer of the Gamma Knife radiosurgery device used in the study. Dr. Barbaro reported no other disclosures. Dr. Langfitt reported being a consultant for Monteris. Dr. Quigg reported being an investigator for several antiepileptic drug trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: During study months 25-36, 78% of the ATL arm and 52% of the SRS arm were seizure free.

Data source: Trial of 58 patients with temporal lobe epilepsy randomized to receive ATL or SRS.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by Elekta, the manufacturer of the Gamma Knife radiosurgery device used in the study. Several of the presenting ROSE steering committee members reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Children with infantile spasms or nonsyndromic epilepsy achieve similar outcomes

HOUSTON – Infants and children who had epilepsy that was not identified as being part of a syndrome fared slightly worse in developmental outcomes and pharmacoresistance than did those with West syndrome/infantile spasms, Dravet syndrome, or another type of syndromic epilepsy, according to a prospective multisite study.

But in the study of 775 patients from 17 American pediatric epilepsy centers, early age at diagnosis was associated with greater mortality, greater risk of developmental decline, and greater pharmacoresistance, regardless of seizure type.

Lead study author Anne Berg, PhD, and her colleagues wrote that they were surprised to see that children in their study population with nonsyndromic epilepsy (NSE) were slightly more likely to have pharmacoresistant seizures (PR).

Further, although logistic regression analysis showed that seizure etiology, younger age at onset, and PR all had independent contributions to developmental decline, “West/IS was not convincingly associated with developmental decline,” they said.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, Dr. Berg, an epidemiologist and research professor of pediatric neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presented the findings of a study that examined outcomes for infants and children diagnosed with epilepsy.

Patients were prospectively identified during a 3-year period from 2012 to 2015. Patients were eligible if their epilepsy began before their third birthday, and if the epilepsy was initially diagnosed at one of the participating centers. Patient data were evaluated for seizure and developmental outcomes if the patient was followed for at least 6 months after diagnosis.

Of the 775 patients initially recruited, 367 (47.3%) were girls. The mean age of epilepsy onset (which usually meant age at first unprovoked seizure) was 11.1 months (standard deviation, 9.4). Most patients (n = 509; 65.7%) were diagnosed with epilepsy before the age of 1 year. Just 115 patients (14.8%) received their epilepsy diagnosis when they were older than 2 years.

A key outcome investigated by Dr. Berg and her colleagues was pharmacoresistance, identified as lack of seizure control (i.e., at least a 3-month seizure-free period) after trying two appropriate medications. Other outcome measures included tracking whether patients developed West/IS, and whether West/IS evolved into other seizure types. The investigators also tracked developmental delay after epilepsy diagnosis and collected data about deaths among participating patients.

About a quarter (27%) of patients had persistent PR; these were more likely to occur in children who were younger at the onset of epilepsy. PR were more common when seizures began before the age of 1 year, occurring in 30% of this patient population, whereas 20% of patients with seizure onset happening after 1 year of age had PR (P = .0008).

Other findings from the study revealed that infants whose NSE had an etiology of focal cortical dysplasia or of an acquired insult such as trauma were more than twice as likely to have their seizures evolve into WS/IS.

Of 214 children whose initial presentation was WS/IS, 49 (23%) developed new seizure types. Most of these (47 of 49) were infants. Patients with WS/IS due to tuberous sclerosis complex, infectious causes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and cephalic brain disorders were more likely to develop new seizure types.

“At initial presentation of epilepsy, children with West/IS were more likely already to have developmental delay than children with other syndromes or NSE,” they said.

Of the 22 patient deaths that occurred during the study, all but 1 occurred in infants younger than 1 year. None of the deaths occurred in typically-developing children with unknown epilepsy etiology.

“West/IS is the only early life epilepsy with consensus guidelines for treatment,” noted Dr. Berg and her coauthors, speculating that the guidelines might contribute to the slightly better outcomes observed for this population in their study.

However, although some groups of infants and children in the study fared slightly better than others, “[F]or the most part, there are no clearly ‘low’ risk groups,” Dr. Berg and her colleagues said. “Our findings highlight that most, if not all, early life epilepsies pose serious risk for poor outcomes and are equally deserving of concerted efforts.”

Dr. Berg reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and conducted through the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Infants and children who had epilepsy that was not identified as being part of a syndrome fared slightly worse in developmental outcomes and pharmacoresistance than did those with West syndrome/infantile spasms, Dravet syndrome, or another type of syndromic epilepsy, according to a prospective multisite study.

But in the study of 775 patients from 17 American pediatric epilepsy centers, early age at diagnosis was associated with greater mortality, greater risk of developmental decline, and greater pharmacoresistance, regardless of seizure type.

Lead study author Anne Berg, PhD, and her colleagues wrote that they were surprised to see that children in their study population with nonsyndromic epilepsy (NSE) were slightly more likely to have pharmacoresistant seizures (PR).

Further, although logistic regression analysis showed that seizure etiology, younger age at onset, and PR all had independent contributions to developmental decline, “West/IS was not convincingly associated with developmental decline,” they said.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, Dr. Berg, an epidemiologist and research professor of pediatric neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presented the findings of a study that examined outcomes for infants and children diagnosed with epilepsy.

Patients were prospectively identified during a 3-year period from 2012 to 2015. Patients were eligible if their epilepsy began before their third birthday, and if the epilepsy was initially diagnosed at one of the participating centers. Patient data were evaluated for seizure and developmental outcomes if the patient was followed for at least 6 months after diagnosis.

Of the 775 patients initially recruited, 367 (47.3%) were girls. The mean age of epilepsy onset (which usually meant age at first unprovoked seizure) was 11.1 months (standard deviation, 9.4). Most patients (n = 509; 65.7%) were diagnosed with epilepsy before the age of 1 year. Just 115 patients (14.8%) received their epilepsy diagnosis when they were older than 2 years.

A key outcome investigated by Dr. Berg and her colleagues was pharmacoresistance, identified as lack of seizure control (i.e., at least a 3-month seizure-free period) after trying two appropriate medications. Other outcome measures included tracking whether patients developed West/IS, and whether West/IS evolved into other seizure types. The investigators also tracked developmental delay after epilepsy diagnosis and collected data about deaths among participating patients.

About a quarter (27%) of patients had persistent PR; these were more likely to occur in children who were younger at the onset of epilepsy. PR were more common when seizures began before the age of 1 year, occurring in 30% of this patient population, whereas 20% of patients with seizure onset happening after 1 year of age had PR (P = .0008).

Other findings from the study revealed that infants whose NSE had an etiology of focal cortical dysplasia or of an acquired insult such as trauma were more than twice as likely to have their seizures evolve into WS/IS.

Of 214 children whose initial presentation was WS/IS, 49 (23%) developed new seizure types. Most of these (47 of 49) were infants. Patients with WS/IS due to tuberous sclerosis complex, infectious causes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and cephalic brain disorders were more likely to develop new seizure types.

“At initial presentation of epilepsy, children with West/IS were more likely already to have developmental delay than children with other syndromes or NSE,” they said.

Of the 22 patient deaths that occurred during the study, all but 1 occurred in infants younger than 1 year. None of the deaths occurred in typically-developing children with unknown epilepsy etiology.

“West/IS is the only early life epilepsy with consensus guidelines for treatment,” noted Dr. Berg and her coauthors, speculating that the guidelines might contribute to the slightly better outcomes observed for this population in their study.

However, although some groups of infants and children in the study fared slightly better than others, “[F]or the most part, there are no clearly ‘low’ risk groups,” Dr. Berg and her colleagues said. “Our findings highlight that most, if not all, early life epilepsies pose serious risk for poor outcomes and are equally deserving of concerted efforts.”

Dr. Berg reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and conducted through the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Infants and children who had epilepsy that was not identified as being part of a syndrome fared slightly worse in developmental outcomes and pharmacoresistance than did those with West syndrome/infantile spasms, Dravet syndrome, or another type of syndromic epilepsy, according to a prospective multisite study.

But in the study of 775 patients from 17 American pediatric epilepsy centers, early age at diagnosis was associated with greater mortality, greater risk of developmental decline, and greater pharmacoresistance, regardless of seizure type.

Lead study author Anne Berg, PhD, and her colleagues wrote that they were surprised to see that children in their study population with nonsyndromic epilepsy (NSE) were slightly more likely to have pharmacoresistant seizures (PR).

Further, although logistic regression analysis showed that seizure etiology, younger age at onset, and PR all had independent contributions to developmental decline, “West/IS was not convincingly associated with developmental decline,” they said.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, Dr. Berg, an epidemiologist and research professor of pediatric neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presented the findings of a study that examined outcomes for infants and children diagnosed with epilepsy.

Patients were prospectively identified during a 3-year period from 2012 to 2015. Patients were eligible if their epilepsy began before their third birthday, and if the epilepsy was initially diagnosed at one of the participating centers. Patient data were evaluated for seizure and developmental outcomes if the patient was followed for at least 6 months after diagnosis.

Of the 775 patients initially recruited, 367 (47.3%) were girls. The mean age of epilepsy onset (which usually meant age at first unprovoked seizure) was 11.1 months (standard deviation, 9.4). Most patients (n = 509; 65.7%) were diagnosed with epilepsy before the age of 1 year. Just 115 patients (14.8%) received their epilepsy diagnosis when they were older than 2 years.

A key outcome investigated by Dr. Berg and her colleagues was pharmacoresistance, identified as lack of seizure control (i.e., at least a 3-month seizure-free period) after trying two appropriate medications. Other outcome measures included tracking whether patients developed West/IS, and whether West/IS evolved into other seizure types. The investigators also tracked developmental delay after epilepsy diagnosis and collected data about deaths among participating patients.

About a quarter (27%) of patients had persistent PR; these were more likely to occur in children who were younger at the onset of epilepsy. PR were more common when seizures began before the age of 1 year, occurring in 30% of this patient population, whereas 20% of patients with seizure onset happening after 1 year of age had PR (P = .0008).

Other findings from the study revealed that infants whose NSE had an etiology of focal cortical dysplasia or of an acquired insult such as trauma were more than twice as likely to have their seizures evolve into WS/IS.

Of 214 children whose initial presentation was WS/IS, 49 (23%) developed new seizure types. Most of these (47 of 49) were infants. Patients with WS/IS due to tuberous sclerosis complex, infectious causes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and cephalic brain disorders were more likely to develop new seizure types.

“At initial presentation of epilepsy, children with West/IS were more likely already to have developmental delay than children with other syndromes or NSE,” they said.

Of the 22 patient deaths that occurred during the study, all but 1 occurred in infants younger than 1 year. None of the deaths occurred in typically-developing children with unknown epilepsy etiology.

“West/IS is the only early life epilepsy with consensus guidelines for treatment,” noted Dr. Berg and her coauthors, speculating that the guidelines might contribute to the slightly better outcomes observed for this population in their study.

However, although some groups of infants and children in the study fared slightly better than others, “[F]or the most part, there are no clearly ‘low’ risk groups,” Dr. Berg and her colleagues said. “Our findings highlight that most, if not all, early life epilepsies pose serious risk for poor outcomes and are equally deserving of concerted efforts.”

Dr. Berg reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and conducted through the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infantile spasms was not independently associated with worse developmental decline compared with nonsyndromic epilepsy.

Data source: Prospective study of 775 infants and children with epilepsy.

Disclosures: Dr. Berg reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and conducted through the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.

Chest-worn seizure detection device shows promise

HOUSTON – An investigative, chest-worn device shows promise for detecting a wide range of seizure types in children with epilepsy, results from a small single-center study showed.

“Our goal is for parents to have more peace of mind, not feeling like they have to watch their kids all night long,” one of the study authors, Kristin H. Gilchrist, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “There are currently many wearable devices marketed for fitness [purposes], but if we can leverage some of these heart rate monitors and use them to detect seizures with specialized algorithms, that would be ideal.”

Approximately 60% of patients had a seizure during the monitoring period. Seizures without any clinical response or those lasting less than 10 seconds (such as single myoclonic jerks or clusters) were excluded from analysis, as were subjects with multiple seizures per hour because the autonomic signals often did not return to baseline, and this seizure frequency is outside of the intended use of the monitor. After exclusions, the algorithm was evaluated on 10 children with a mean age of 12 years. For additional validation, the algorithm was also evaluated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, PhysioNet database with ECG from five adults with partial seizures (Neurology. 1999;53:1590-2).The algorithm without motion parameters detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3) or atonic/clonic/tonic (4/4), and 3/9 and 7/10 of focal seizures from the CNMC and MIT subjects, respectively. In the CNMC dataset, the motion algorithm detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3), half of those categorized as atonic/clonic/tonic (2/4), and one of nine classified as focal seizures.

In the CNMC dataset, false positives averaged one per 14 hours, however, the majority of false positives occurred in a few patients with poor sensor data quality. More than half of the subjects (70%) had no false positives. One false positive occurred in the 16.8 hours of MIT data.

“In addition to an alert application, we have a technology that can be beneficial to clinic-based studies to quantify how many seizures people are having,” Dr. Gilchrist said. “Hopefully someday it will reach the commercial market.” She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – An investigative, chest-worn device shows promise for detecting a wide range of seizure types in children with epilepsy, results from a small single-center study showed.

“Our goal is for parents to have more peace of mind, not feeling like they have to watch their kids all night long,” one of the study authors, Kristin H. Gilchrist, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “There are currently many wearable devices marketed for fitness [purposes], but if we can leverage some of these heart rate monitors and use them to detect seizures with specialized algorithms, that would be ideal.”

Approximately 60% of patients had a seizure during the monitoring period. Seizures without any clinical response or those lasting less than 10 seconds (such as single myoclonic jerks or clusters) were excluded from analysis, as were subjects with multiple seizures per hour because the autonomic signals often did not return to baseline, and this seizure frequency is outside of the intended use of the monitor. After exclusions, the algorithm was evaluated on 10 children with a mean age of 12 years. For additional validation, the algorithm was also evaluated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, PhysioNet database with ECG from five adults with partial seizures (Neurology. 1999;53:1590-2).The algorithm without motion parameters detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3) or atonic/clonic/tonic (4/4), and 3/9 and 7/10 of focal seizures from the CNMC and MIT subjects, respectively. In the CNMC dataset, the motion algorithm detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3), half of those categorized as atonic/clonic/tonic (2/4), and one of nine classified as focal seizures.

In the CNMC dataset, false positives averaged one per 14 hours, however, the majority of false positives occurred in a few patients with poor sensor data quality. More than half of the subjects (70%) had no false positives. One false positive occurred in the 16.8 hours of MIT data.

“In addition to an alert application, we have a technology that can be beneficial to clinic-based studies to quantify how many seizures people are having,” Dr. Gilchrist said. “Hopefully someday it will reach the commercial market.” She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – An investigative, chest-worn device shows promise for detecting a wide range of seizure types in children with epilepsy, results from a small single-center study showed.

“Our goal is for parents to have more peace of mind, not feeling like they have to watch their kids all night long,” one of the study authors, Kristin H. Gilchrist, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “There are currently many wearable devices marketed for fitness [purposes], but if we can leverage some of these heart rate monitors and use them to detect seizures with specialized algorithms, that would be ideal.”

Approximately 60% of patients had a seizure during the monitoring period. Seizures without any clinical response or those lasting less than 10 seconds (such as single myoclonic jerks or clusters) were excluded from analysis, as were subjects with multiple seizures per hour because the autonomic signals often did not return to baseline, and this seizure frequency is outside of the intended use of the monitor. After exclusions, the algorithm was evaluated on 10 children with a mean age of 12 years. For additional validation, the algorithm was also evaluated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, PhysioNet database with ECG from five adults with partial seizures (Neurology. 1999;53:1590-2).The algorithm without motion parameters detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3) or atonic/clonic/tonic (4/4), and 3/9 and 7/10 of focal seizures from the CNMC and MIT subjects, respectively. In the CNMC dataset, the motion algorithm detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3), half of those categorized as atonic/clonic/tonic (2/4), and one of nine classified as focal seizures.

In the CNMC dataset, false positives averaged one per 14 hours, however, the majority of false positives occurred in a few patients with poor sensor data quality. More than half of the subjects (70%) had no false positives. One false positive occurred in the 16.8 hours of MIT data.

“In addition to an alert application, we have a technology that can be beneficial to clinic-based studies to quantify how many seizures people are having,” Dr. Gilchrist said. “Hopefully someday it will reach the commercial market.” She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The algorithm without motion parameters detected all seizures classified as tonic-clonic (3/3) or atonic/clonic/tonic (4/4), and 3 of 9 classified as focal seizures.

Data source: A clinic-based study of 10 epilepsy patients with a mean age of 12 years who wore an investigative device to detect seizures.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gilchrist reported having no financial disclosures.

Study highlights need to address vitamin D deficiency in epilepsy patients

HOUSTON – Neurologists and other clinicians ordered vitamin D levels, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans, and vitamin D supplementation for epilepsy patients in order to diagnose and prevent vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia, results from a single-center study showed.

Vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia are well described in the literature for patients on enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (EIADs), but no guidelines currently exist for when to order tests or supplementation for patients on EIADs or non–enzyme inducing antiepileptic drugs (NEIADs). “Further studies with larger sample sizes will be helpful in order to establish guidelines for neurologists and other physicians,” Sher Afgan, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Afgan, a research assistant at Drexel, went on to report that neurologists ordered vitamin D levels in 22% of patients; another 12% had already been ordered by another physician. Neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (32% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001), and vitamin D levels were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (41% vs. 26%; P = .02). Neurologists ordered DXA scans in 22% of patients, and more often for those on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (33% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001). Similarly, DXA scans were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (35.3% vs. 18.2%; P = .006). Supplementation was ordered in 23% of patients and was more likely to be ordered by neurologists for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (36% vs. 8%; P less than .001).

The researchers also found that neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels, DXA scans, and supplements for men on EIADs, compared with women on EIADs (odds ratio, 2.178, P = .03; OR, 2.31, P = .02; OR, 1.87, P = .09, respectively). Generalized epilepsy did not significantly account for increases in ordering vitamin D for EIADs. Median total vitamin D levels were lower in patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (29 vs. 18 ng/mL; P = .03), but age and body mass index were not different among patients for whom neurologists ordered Vitamin D levels, DXA scans, or supplementation.

Dr. Afgan acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and small sample size. “Also, type and duration of epilepsy, type and duration of antiepileptic drugs, and comorbidities should be considered in further studies with larger sample sizes,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Neurologists and other clinicians ordered vitamin D levels, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans, and vitamin D supplementation for epilepsy patients in order to diagnose and prevent vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia, results from a single-center study showed.

Vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia are well described in the literature for patients on enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (EIADs), but no guidelines currently exist for when to order tests or supplementation for patients on EIADs or non–enzyme inducing antiepileptic drugs (NEIADs). “Further studies with larger sample sizes will be helpful in order to establish guidelines for neurologists and other physicians,” Sher Afgan, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Afgan, a research assistant at Drexel, went on to report that neurologists ordered vitamin D levels in 22% of patients; another 12% had already been ordered by another physician. Neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (32% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001), and vitamin D levels were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (41% vs. 26%; P = .02). Neurologists ordered DXA scans in 22% of patients, and more often for those on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (33% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001). Similarly, DXA scans were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (35.3% vs. 18.2%; P = .006). Supplementation was ordered in 23% of patients and was more likely to be ordered by neurologists for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (36% vs. 8%; P less than .001).

The researchers also found that neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels, DXA scans, and supplements for men on EIADs, compared with women on EIADs (odds ratio, 2.178, P = .03; OR, 2.31, P = .02; OR, 1.87, P = .09, respectively). Generalized epilepsy did not significantly account for increases in ordering vitamin D for EIADs. Median total vitamin D levels were lower in patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (29 vs. 18 ng/mL; P = .03), but age and body mass index were not different among patients for whom neurologists ordered Vitamin D levels, DXA scans, or supplementation.

Dr. Afgan acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and small sample size. “Also, type and duration of epilepsy, type and duration of antiepileptic drugs, and comorbidities should be considered in further studies with larger sample sizes,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – Neurologists and other clinicians ordered vitamin D levels, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans, and vitamin D supplementation for epilepsy patients in order to diagnose and prevent vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia, results from a single-center study showed.

Vitamin D deficiency and osteopenia are well described in the literature for patients on enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (EIADs), but no guidelines currently exist for when to order tests or supplementation for patients on EIADs or non–enzyme inducing antiepileptic drugs (NEIADs). “Further studies with larger sample sizes will be helpful in order to establish guidelines for neurologists and other physicians,” Sher Afgan, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Afgan, a research assistant at Drexel, went on to report that neurologists ordered vitamin D levels in 22% of patients; another 12% had already been ordered by another physician. Neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (32% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001), and vitamin D levels were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (41% vs. 26%; P = .02). Neurologists ordered DXA scans in 22% of patients, and more often for those on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (33% vs. 10.4%; P less than .001). Similarly, DXA scans were more likely to be ordered by either neurologists or other physicians for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (35.3% vs. 18.2%; P = .006). Supplementation was ordered in 23% of patients and was more likely to be ordered by neurologists for patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (36% vs. 8%; P less than .001).

The researchers also found that neurologists were more likely to order vitamin D levels, DXA scans, and supplements for men on EIADs, compared with women on EIADs (odds ratio, 2.178, P = .03; OR, 2.31, P = .02; OR, 1.87, P = .09, respectively). Generalized epilepsy did not significantly account for increases in ordering vitamin D for EIADs. Median total vitamin D levels were lower in patients on EIADs, compared with those on NEIADs (29 vs. 18 ng/mL; P = .03), but age and body mass index were not different among patients for whom neurologists ordered Vitamin D levels, DXA scans, or supplementation.

Dr. Afgan acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and small sample size. “Also, type and duration of epilepsy, type and duration of antiepileptic drugs, and comorbidities should be considered in further studies with larger sample sizes,” he said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Neurologists ordered vitamin D levels in 22% of patients; another 12% were already ordered by another physician.

Data source: A retrospective review of 190 patients who had a diagnosis of epilepsy or seizures, were currently on antiepileptic medications, and whose most recent neurology visit occurred between 2009 and 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Afgan reported having no financial disclosures.

Project aims to improve understanding of AED prescribing trends

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%).

Data source: A pilot study that evaluated medical records from about 2.5 million epilepsy patients from 2013 to 2015.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

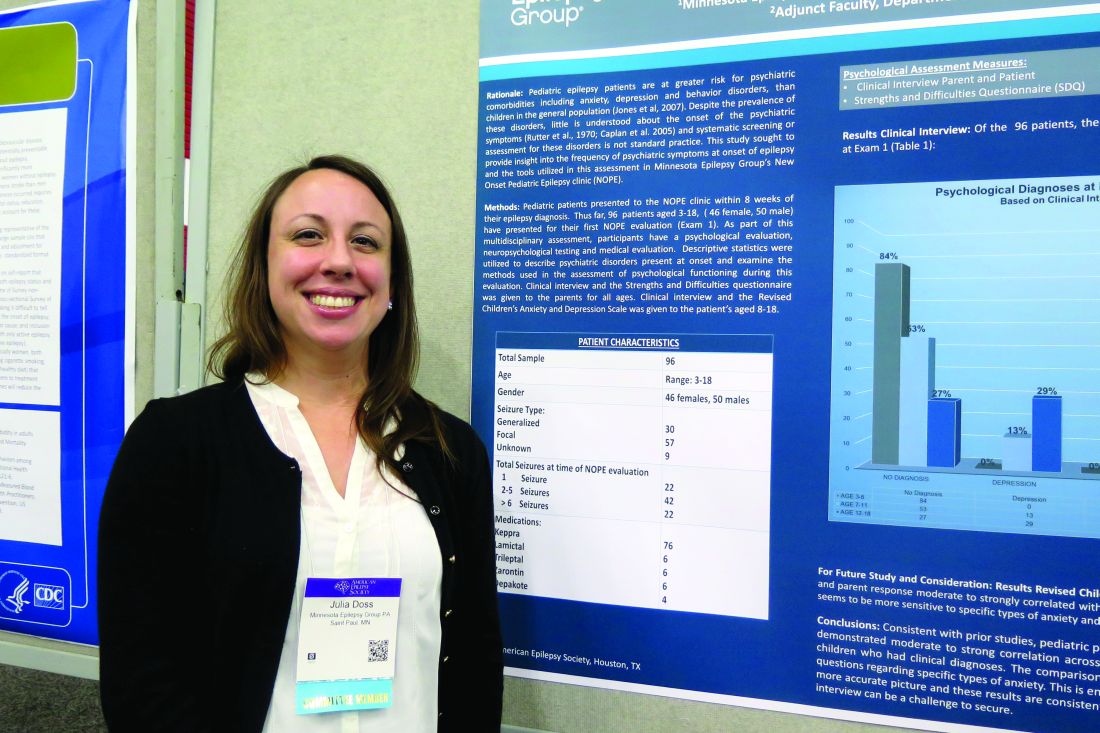

Psychiatric comorbidities common in newly diagnosed pediatric epilepsy cases

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among patients aged 12-18 years, the percentage who met criteria for criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 29%, 38%, and 10%, respectively.

Data source: A study of 96 patients who presented to a New Onset Pediatric Epilepsy (NOPE) clinic within 8 weeks of their epilepsy diagnosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Doss reported having no financial disclosures.

Study eyes fracture risk in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic drugs

HOUSTON – The incidence of fractures in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic medication stands at an estimated 1.1%, according to results from a 4-year period at a children’s hospital.

“Understanding the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an AED [antiepileptic drug] will allow clinicians to weigh the risk versus benefit of therapy,” researchers led by Shannon DiCarlo, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Recognizing a risk of fractures with AEDs will permit clinicians to provide appropriate supportive care and monitoring from the initiation of therapy.”

Dr. DiCarlo of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and her associates went on to note that adults with epilepsy have a twofold to sixfold greater risk of experiencing fractures, compared with the general population, and that fractures secondary to seizures “are a major concern in pediatrics.” In fact, one survey of 404 pediatric neurologists found that only 41% of respondents were aware of the association between AEDs and reduced bone mass (Arch Neurol. 2001;58[9]:1369-74).