User login

HOUSTON – Infants and children who had epilepsy that was not identified as being part of a syndrome fared slightly worse in developmental outcomes and pharmacoresistance than did those with West syndrome/infantile spasms, Dravet syndrome, or another type of syndromic epilepsy, according to a prospective multisite study.

But in the study of 775 patients from 17 American pediatric epilepsy centers, early age at diagnosis was associated with greater mortality, greater risk of developmental decline, and greater pharmacoresistance, regardless of seizure type.

Lead study author Anne Berg, PhD, and her colleagues wrote that they were surprised to see that children in their study population with nonsyndromic epilepsy (NSE) were slightly more likely to have pharmacoresistant seizures (PR).

Further, although logistic regression analysis showed that seizure etiology, younger age at onset, and PR all had independent contributions to developmental decline, “West/IS was not convincingly associated with developmental decline,” they said.

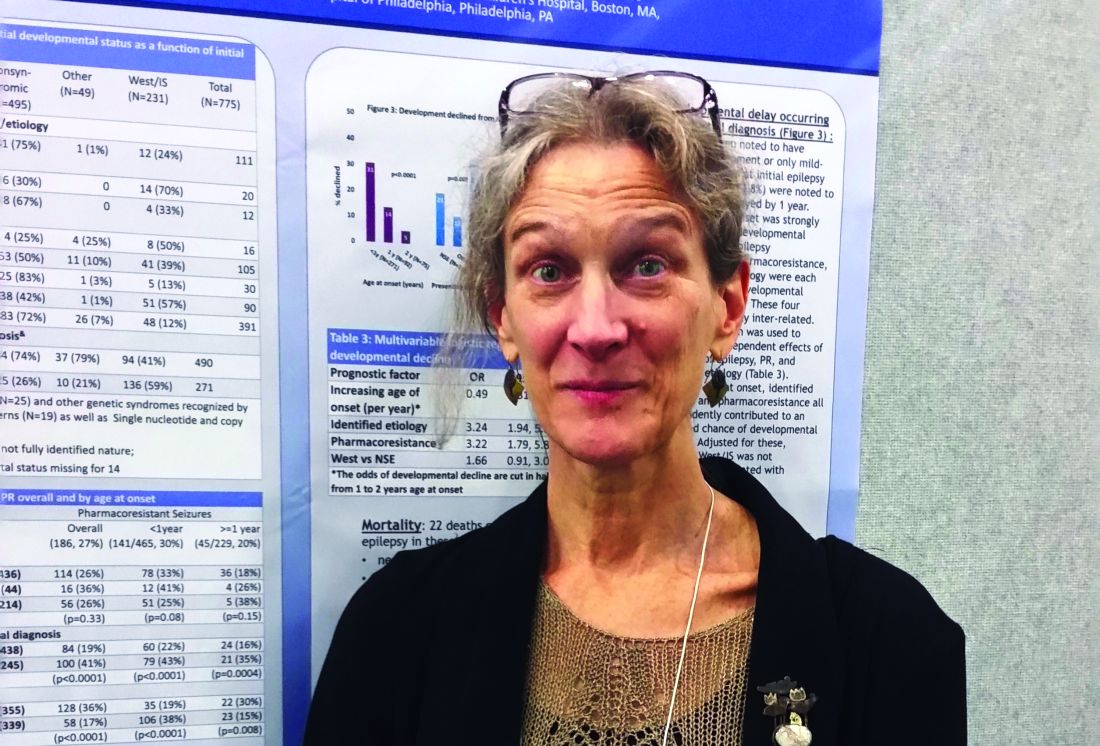

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, Dr. Berg, an epidemiologist and research professor of pediatric neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presented the findings of a study that examined outcomes for infants and children diagnosed with epilepsy.

Patients were prospectively identified during a 3-year period from 2012 to 2015. Patients were eligible if their epilepsy began before their third birthday, and if the epilepsy was initially diagnosed at one of the participating centers. Patient data were evaluated for seizure and developmental outcomes if the patient was followed for at least 6 months after diagnosis.

Of the 775 patients initially recruited, 367 (47.3%) were girls. The mean age of epilepsy onset (which usually meant age at first unprovoked seizure) was 11.1 months (standard deviation, 9.4). Most patients (n = 509; 65.7%) were diagnosed with epilepsy before the age of 1 year. Just 115 patients (14.8%) received their epilepsy diagnosis when they were older than 2 years.

A key outcome investigated by Dr. Berg and her colleagues was pharmacoresistance, identified as lack of seizure control (i.e., at least a 3-month seizure-free period) after trying two appropriate medications. Other outcome measures included tracking whether patients developed West/IS, and whether West/IS evolved into other seizure types. The investigators also tracked developmental delay after epilepsy diagnosis and collected data about deaths among participating patients.

About a quarter (27%) of patients had persistent PR; these were more likely to occur in children who were younger at the onset of epilepsy. PR were more common when seizures began before the age of 1 year, occurring in 30% of this patient population, whereas 20% of patients with seizure onset happening after 1 year of age had PR (P = .0008).

Other findings from the study revealed that infants whose NSE had an etiology of focal cortical dysplasia or of an acquired insult such as trauma were more than twice as likely to have their seizures evolve into WS/IS.

Of 214 children whose initial presentation was WS/IS, 49 (23%) developed new seizure types. Most of these (47 of 49) were infants. Patients with WS/IS due to tuberous sclerosis complex, infectious causes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and cephalic brain disorders were more likely to develop new seizure types.

“At initial presentation of epilepsy, children with West/IS were more likely already to have developmental delay than children with other syndromes or NSE,” they said.

Of the 22 patient deaths that occurred during the study, all but 1 occurred in infants younger than 1 year. None of the deaths occurred in typically-developing children with unknown epilepsy etiology.

“West/IS is the only early life epilepsy with consensus guidelines for treatment,” noted Dr. Berg and her coauthors, speculating that the guidelines might contribute to the slightly better outcomes observed for this population in their study.

However, although some groups of infants and children in the study fared slightly better than others, “[F]or the most part, there are no clearly ‘low’ risk groups,” Dr. Berg and her colleagues said. “Our findings highlight that most, if not all, early life epilepsies pose serious risk for poor outcomes and are equally deserving of concerted efforts.”

Dr. Berg reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and conducted through the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Infants and children who had epilepsy that was not identified as being part of a syndrome fared slightly worse in developmental outcomes and pharmacoresistance than did those with West syndrome/infantile spasms, Dravet syndrome, or another type of syndromic epilepsy, according to a prospective multisite study.

But in the study of 775 patients from 17 American pediatric epilepsy centers, early age at diagnosis was associated with greater mortality, greater risk of developmental decline, and greater pharmacoresistance, regardless of seizure type.

Lead study author Anne Berg, PhD, and her colleagues wrote that they were surprised to see that children in their study population with nonsyndromic epilepsy (NSE) were slightly more likely to have pharmacoresistant seizures (PR).

Further, although logistic regression analysis showed that seizure etiology, younger age at onset, and PR all had independent contributions to developmental decline, “West/IS was not convincingly associated with developmental decline,” they said.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, Dr. Berg, an epidemiologist and research professor of pediatric neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presented the findings of a study that examined outcomes for infants and children diagnosed with epilepsy.

Patients were prospectively identified during a 3-year period from 2012 to 2015. Patients were eligible if their epilepsy began before their third birthday, and if the epilepsy was initially diagnosed at one of the participating centers. Patient data were evaluated for seizure and developmental outcomes if the patient was followed for at least 6 months after diagnosis.

Of the 775 patients initially recruited, 367 (47.3%) were girls. The mean age of epilepsy onset (which usually meant age at first unprovoked seizure) was 11.1 months (standard deviation, 9.4). Most patients (n = 509; 65.7%) were diagnosed with epilepsy before the age of 1 year. Just 115 patients (14.8%) received their epilepsy diagnosis when they were older than 2 years.

A key outcome investigated by Dr. Berg and her colleagues was pharmacoresistance, identified as lack of seizure control (i.e., at least a 3-month seizure-free period) after trying two appropriate medications. Other outcome measures included tracking whether patients developed West/IS, and whether West/IS evolved into other seizure types. The investigators also tracked developmental delay after epilepsy diagnosis and collected data about deaths among participating patients.

About a quarter (27%) of patients had persistent PR; these were more likely to occur in children who were younger at the onset of epilepsy. PR were more common when seizures began before the age of 1 year, occurring in 30% of this patient population, whereas 20% of patients with seizure onset happening after 1 year of age had PR (P = .0008).

Other findings from the study revealed that infants whose NSE had an etiology of focal cortical dysplasia or of an acquired insult such as trauma were more than twice as likely to have their seizures evolve into WS/IS.

Of 214 children whose initial presentation was WS/IS, 49 (23%) developed new seizure types. Most of these (47 of 49) were infants. Patients with WS/IS due to tuberous sclerosis complex, infectious causes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and cephalic brain disorders were more likely to develop new seizure types.

“At initial presentation of epilepsy, children with West/IS were more likely already to have developmental delay than children with other syndromes or NSE,” they said.

Of the 22 patient deaths that occurred during the study, all but 1 occurred in infants younger than 1 year. None of the deaths occurred in typically-developing children with unknown epilepsy etiology.

“West/IS is the only early life epilepsy with consensus guidelines for treatment,” noted Dr. Berg and her coauthors, speculating that the guidelines might contribute to the slightly better outcomes observed for this population in their study.

However, although some groups of infants and children in the study fared slightly better than others, “[F]or the most part, there are no clearly ‘low’ risk groups,” Dr. Berg and her colleagues said. “Our findings highlight that most, if not all, early life epilepsies pose serious risk for poor outcomes and are equally deserving of concerted efforts.”

Dr. Berg reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and conducted through the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Infants and children who had epilepsy that was not identified as being part of a syndrome fared slightly worse in developmental outcomes and pharmacoresistance than did those with West syndrome/infantile spasms, Dravet syndrome, or another type of syndromic epilepsy, according to a prospective multisite study.

But in the study of 775 patients from 17 American pediatric epilepsy centers, early age at diagnosis was associated with greater mortality, greater risk of developmental decline, and greater pharmacoresistance, regardless of seizure type.

Lead study author Anne Berg, PhD, and her colleagues wrote that they were surprised to see that children in their study population with nonsyndromic epilepsy (NSE) were slightly more likely to have pharmacoresistant seizures (PR).

Further, although logistic regression analysis showed that seizure etiology, younger age at onset, and PR all had independent contributions to developmental decline, “West/IS was not convincingly associated with developmental decline,” they said.

In a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, Dr. Berg, an epidemiologist and research professor of pediatric neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presented the findings of a study that examined outcomes for infants and children diagnosed with epilepsy.

Patients were prospectively identified during a 3-year period from 2012 to 2015. Patients were eligible if their epilepsy began before their third birthday, and if the epilepsy was initially diagnosed at one of the participating centers. Patient data were evaluated for seizure and developmental outcomes if the patient was followed for at least 6 months after diagnosis.

Of the 775 patients initially recruited, 367 (47.3%) were girls. The mean age of epilepsy onset (which usually meant age at first unprovoked seizure) was 11.1 months (standard deviation, 9.4). Most patients (n = 509; 65.7%) were diagnosed with epilepsy before the age of 1 year. Just 115 patients (14.8%) received their epilepsy diagnosis when they were older than 2 years.

A key outcome investigated by Dr. Berg and her colleagues was pharmacoresistance, identified as lack of seizure control (i.e., at least a 3-month seizure-free period) after trying two appropriate medications. Other outcome measures included tracking whether patients developed West/IS, and whether West/IS evolved into other seizure types. The investigators also tracked developmental delay after epilepsy diagnosis and collected data about deaths among participating patients.

About a quarter (27%) of patients had persistent PR; these were more likely to occur in children who were younger at the onset of epilepsy. PR were more common when seizures began before the age of 1 year, occurring in 30% of this patient population, whereas 20% of patients with seizure onset happening after 1 year of age had PR (P = .0008).

Other findings from the study revealed that infants whose NSE had an etiology of focal cortical dysplasia or of an acquired insult such as trauma were more than twice as likely to have their seizures evolve into WS/IS.

Of 214 children whose initial presentation was WS/IS, 49 (23%) developed new seizure types. Most of these (47 of 49) were infants. Patients with WS/IS due to tuberous sclerosis complex, infectious causes, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and cephalic brain disorders were more likely to develop new seizure types.

“At initial presentation of epilepsy, children with West/IS were more likely already to have developmental delay than children with other syndromes or NSE,” they said.

Of the 22 patient deaths that occurred during the study, all but 1 occurred in infants younger than 1 year. None of the deaths occurred in typically-developing children with unknown epilepsy etiology.

“West/IS is the only early life epilepsy with consensus guidelines for treatment,” noted Dr. Berg and her coauthors, speculating that the guidelines might contribute to the slightly better outcomes observed for this population in their study.

However, although some groups of infants and children in the study fared slightly better than others, “[F]or the most part, there are no clearly ‘low’ risk groups,” Dr. Berg and her colleagues said. “Our findings highlight that most, if not all, early life epilepsies pose serious risk for poor outcomes and are equally deserving of concerted efforts.”

Dr. Berg reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and conducted through the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infantile spasms was not independently associated with worse developmental decline compared with nonsyndromic epilepsy.

Data source: Prospective study of 775 infants and children with epilepsy.

Disclosures: Dr. Berg reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation, and conducted through the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.