User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Comorbidities larger factor than race in COVID ICU deaths?

Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates may be related more to comorbidities than to demographics, suggest authors of a new study.

Researchers compared the length of stay in intensive care units in two suburban hospitals for patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Their study shows that although the incidence of comorbidities and rates of use of mechanical ventilation and death were higher among Black patients than among patients of other races, length of stay in the ICU was generally similar for patients of all races. The study was conducted by Tripti Kumar, DO, from Lankenau Medical Center, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, and colleagues.

“Racial disparities are observed in the United States concerning COVID-19, and studies have discovered that minority populations are at ongoing risk for health inequity,” Dr. Kumar said in a narrated e-poster presented during the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Primary prevention initiatives should take precedence in mitigating the effect that comorbidities have on these vulnerable populations to help reduce necessity for mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and overall mortality,” she said.

Higher death rates for Black patients

At the time the study was conducted, the COVID-19 death rate in the United States had topped 500,000 (as of this writing, it stands at 726,000). Of those who died, 22.4% were Black, 18.1% were Hispanic, and 3.6% were of Asian descent. The numbers of COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths were significantly higher in U.S. counties where the proportions of Black residents were higher, the authors note.

To see whether differences in COVID-19 outcomes were reflected in ICU length of stay, the researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of data on 162 patients admitted to ICUs at Paoli Hospital and Lankenau Medical Center, both in the suburban Philadelphia town of Wynnewood.

All patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 from March through June 2020.

In all, 60% of the study population were Black, 35% were White, 3% were Asian, and 2% were Hispanic. Women composed 46% of the sample.

The average length of ICU stay, which was the primary endpoint, was similar among Black patients (15.4 days), White patients (15.5 days), and Asians (16 days). The shortest average hospital stay was among Hispanic patients, at 11.3 days.

The investigators determined that among all races, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and smoking was highest among Black patients.

Overall, nearly 85% of patients required mechanical ventilation. Among the patients who required it, 86% were Black, 84% were White, 66% were Hispanic, and 75% were Asian.

Overall mortality was 62%. It was higher among Black patients, at 60%, than among White patients, at 33%. The investigators did not report mortality rates for Hispanic or Asian patients.

Missing data

Demondes Haynes, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and associate dean for admissions at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and School of Medicine, Jackson, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that there are some gaps in the study that make it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the findings.

“For sure, comorbidities contribute a great deal to mortality, but is there something else going on? I think this poster is incomplete in that it cannot answer that question,” he said in an interview.

He noted that the use of retrospective rather than prospective data makes it hard to account for potential confounders.

“I agree that these findings show the potential contribution of comorbidities, but to me, this is a little incomplete to make that a definitive statement,” he said.

“I can’t argue with their recommendation for primary prevention – we definitely want to do primary prevention to decrease comorbidities. Would it decrease overall mortality? It might, it sure might, for just COVID-19 I’d say no, we need more information.”

No funding source for the study was reported. Dr. Kumar and colleagues and Dr. Haynes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates may be related more to comorbidities than to demographics, suggest authors of a new study.

Researchers compared the length of stay in intensive care units in two suburban hospitals for patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Their study shows that although the incidence of comorbidities and rates of use of mechanical ventilation and death were higher among Black patients than among patients of other races, length of stay in the ICU was generally similar for patients of all races. The study was conducted by Tripti Kumar, DO, from Lankenau Medical Center, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, and colleagues.

“Racial disparities are observed in the United States concerning COVID-19, and studies have discovered that minority populations are at ongoing risk for health inequity,” Dr. Kumar said in a narrated e-poster presented during the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Primary prevention initiatives should take precedence in mitigating the effect that comorbidities have on these vulnerable populations to help reduce necessity for mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and overall mortality,” she said.

Higher death rates for Black patients

At the time the study was conducted, the COVID-19 death rate in the United States had topped 500,000 (as of this writing, it stands at 726,000). Of those who died, 22.4% were Black, 18.1% were Hispanic, and 3.6% were of Asian descent. The numbers of COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths were significantly higher in U.S. counties where the proportions of Black residents were higher, the authors note.

To see whether differences in COVID-19 outcomes were reflected in ICU length of stay, the researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of data on 162 patients admitted to ICUs at Paoli Hospital and Lankenau Medical Center, both in the suburban Philadelphia town of Wynnewood.

All patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 from March through June 2020.

In all, 60% of the study population were Black, 35% were White, 3% were Asian, and 2% were Hispanic. Women composed 46% of the sample.

The average length of ICU stay, which was the primary endpoint, was similar among Black patients (15.4 days), White patients (15.5 days), and Asians (16 days). The shortest average hospital stay was among Hispanic patients, at 11.3 days.

The investigators determined that among all races, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and smoking was highest among Black patients.

Overall, nearly 85% of patients required mechanical ventilation. Among the patients who required it, 86% were Black, 84% were White, 66% were Hispanic, and 75% were Asian.

Overall mortality was 62%. It was higher among Black patients, at 60%, than among White patients, at 33%. The investigators did not report mortality rates for Hispanic or Asian patients.

Missing data

Demondes Haynes, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and associate dean for admissions at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and School of Medicine, Jackson, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that there are some gaps in the study that make it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the findings.

“For sure, comorbidities contribute a great deal to mortality, but is there something else going on? I think this poster is incomplete in that it cannot answer that question,” he said in an interview.

He noted that the use of retrospective rather than prospective data makes it hard to account for potential confounders.

“I agree that these findings show the potential contribution of comorbidities, but to me, this is a little incomplete to make that a definitive statement,” he said.

“I can’t argue with their recommendation for primary prevention – we definitely want to do primary prevention to decrease comorbidities. Would it decrease overall mortality? It might, it sure might, for just COVID-19 I’d say no, we need more information.”

No funding source for the study was reported. Dr. Kumar and colleagues and Dr. Haynes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates may be related more to comorbidities than to demographics, suggest authors of a new study.

Researchers compared the length of stay in intensive care units in two suburban hospitals for patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Their study shows that although the incidence of comorbidities and rates of use of mechanical ventilation and death were higher among Black patients than among patients of other races, length of stay in the ICU was generally similar for patients of all races. The study was conducted by Tripti Kumar, DO, from Lankenau Medical Center, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, and colleagues.

“Racial disparities are observed in the United States concerning COVID-19, and studies have discovered that minority populations are at ongoing risk for health inequity,” Dr. Kumar said in a narrated e-poster presented during the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Primary prevention initiatives should take precedence in mitigating the effect that comorbidities have on these vulnerable populations to help reduce necessity for mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and overall mortality,” she said.

Higher death rates for Black patients

At the time the study was conducted, the COVID-19 death rate in the United States had topped 500,000 (as of this writing, it stands at 726,000). Of those who died, 22.4% were Black, 18.1% were Hispanic, and 3.6% were of Asian descent. The numbers of COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths were significantly higher in U.S. counties where the proportions of Black residents were higher, the authors note.

To see whether differences in COVID-19 outcomes were reflected in ICU length of stay, the researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of data on 162 patients admitted to ICUs at Paoli Hospital and Lankenau Medical Center, both in the suburban Philadelphia town of Wynnewood.

All patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 from March through June 2020.

In all, 60% of the study population were Black, 35% were White, 3% were Asian, and 2% were Hispanic. Women composed 46% of the sample.

The average length of ICU stay, which was the primary endpoint, was similar among Black patients (15.4 days), White patients (15.5 days), and Asians (16 days). The shortest average hospital stay was among Hispanic patients, at 11.3 days.

The investigators determined that among all races, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and smoking was highest among Black patients.

Overall, nearly 85% of patients required mechanical ventilation. Among the patients who required it, 86% were Black, 84% were White, 66% were Hispanic, and 75% were Asian.

Overall mortality was 62%. It was higher among Black patients, at 60%, than among White patients, at 33%. The investigators did not report mortality rates for Hispanic or Asian patients.

Missing data

Demondes Haynes, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and associate dean for admissions at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and School of Medicine, Jackson, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that there are some gaps in the study that make it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the findings.

“For sure, comorbidities contribute a great deal to mortality, but is there something else going on? I think this poster is incomplete in that it cannot answer that question,” he said in an interview.

He noted that the use of retrospective rather than prospective data makes it hard to account for potential confounders.

“I agree that these findings show the potential contribution of comorbidities, but to me, this is a little incomplete to make that a definitive statement,” he said.

“I can’t argue with their recommendation for primary prevention – we definitely want to do primary prevention to decrease comorbidities. Would it decrease overall mortality? It might, it sure might, for just COVID-19 I’d say no, we need more information.”

No funding source for the study was reported. Dr. Kumar and colleagues and Dr. Haynes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA authorizes boosters for Moderna, J&J, allows mix-and-match

in people who are eligible to get them.

The move to amend the Emergency Use Authorization for these vaccines gives the vaccine experts on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices latitude to recommend a mix-and-match strategy if they feel the science supports it.

The committee convenes Oct. 21 for a day-long meeting to make its recommendations for additional doses.

People who’ve previously received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine, which is now called Spikevax, are eligible for a third dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are 6 months past their second dose and are:

- 65 years of age or older

- 18 to 64 years of age, but at high risk for severe COVID-19 because of an underlying health condition

- 18 to 64 years of age and at high risk for exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus because they live in a group setting, such as a prison or care home, or work in a risky occupation, such as healthcare

People who’ve previously received a dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are eligible for a second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are over the age of 18 and at least 2 months past their vaccination.

“Today’s actions demonstrate our commitment to public health in proactively fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, in a news release. “As the pandemic continues to impact the country, science has shown that vaccination continues to be the safest and most effective way to prevent COVID-19, including the most serious consequences of the disease, such as hospitalization and death.

“The available data suggest waning immunity in some populations who are fully vaccinated. The availability of these authorized boosters is important for continued protection against COVID-19 disease.”

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

in people who are eligible to get them.

The move to amend the Emergency Use Authorization for these vaccines gives the vaccine experts on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices latitude to recommend a mix-and-match strategy if they feel the science supports it.

The committee convenes Oct. 21 for a day-long meeting to make its recommendations for additional doses.

People who’ve previously received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine, which is now called Spikevax, are eligible for a third dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are 6 months past their second dose and are:

- 65 years of age or older

- 18 to 64 years of age, but at high risk for severe COVID-19 because of an underlying health condition

- 18 to 64 years of age and at high risk for exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus because they live in a group setting, such as a prison or care home, or work in a risky occupation, such as healthcare

People who’ve previously received a dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are eligible for a second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are over the age of 18 and at least 2 months past their vaccination.

“Today’s actions demonstrate our commitment to public health in proactively fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, in a news release. “As the pandemic continues to impact the country, science has shown that vaccination continues to be the safest and most effective way to prevent COVID-19, including the most serious consequences of the disease, such as hospitalization and death.

“The available data suggest waning immunity in some populations who are fully vaccinated. The availability of these authorized boosters is important for continued protection against COVID-19 disease.”

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

in people who are eligible to get them.

The move to amend the Emergency Use Authorization for these vaccines gives the vaccine experts on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices latitude to recommend a mix-and-match strategy if they feel the science supports it.

The committee convenes Oct. 21 for a day-long meeting to make its recommendations for additional doses.

People who’ve previously received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine, which is now called Spikevax, are eligible for a third dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are 6 months past their second dose and are:

- 65 years of age or older

- 18 to 64 years of age, but at high risk for severe COVID-19 because of an underlying health condition

- 18 to 64 years of age and at high risk for exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus because they live in a group setting, such as a prison or care home, or work in a risky occupation, such as healthcare

People who’ve previously received a dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are eligible for a second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are over the age of 18 and at least 2 months past their vaccination.

“Today’s actions demonstrate our commitment to public health in proactively fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, in a news release. “As the pandemic continues to impact the country, science has shown that vaccination continues to be the safest and most effective way to prevent COVID-19, including the most serious consequences of the disease, such as hospitalization and death.

“The available data suggest waning immunity in some populations who are fully vaccinated. The availability of these authorized boosters is important for continued protection against COVID-19 disease.”

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

Geographic cohorting increased direct care time and interruptions

Background: Geographic cohorting localizes hospitalist teams to a single unit. It has previously been shown to improve outcomes.

Design: Prospective time and motion study.

Setting: 11 geographically cohorted services and 4 noncohorted teams at Indiana University Health, a large academic medical center.

Synopsis: Geotracking was used to monitor time spent inside and outside of patient rooms for 17 hospitalists over at least 6 weeks. Eight hospitalists were also directly observed. Both groups spent roughly three times more time outside patient rooms than inside. Geographic cohorting was associated with longer patient visits (ranging from 69.6 to 101.7 minutes per day depending on team structure) and a higher percentage of time in patient rooms. Interruptions were more common with geographic cohorting. These hospitalists were interrupted every 14 minutes in the morning and every 8 minutes in the afternoon. Of these interruptions, 62% were face-to-face, 25% were electronic, and 13% were both simultaneously.

An important limitation of this study is that the investigators did not evaluate clinical outcomes or provider satisfaction. This may give some pause to the widespread push toward geographic cohorting.

Bottom line: More frequent interruptions may partially offset potential increases in patient-hospitalist interactions achieved through geographic cohorting.

Citation: Kara A et al. A time motion study evaluating the impact of geographic cohorting of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:338-44.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Geographic cohorting localizes hospitalist teams to a single unit. It has previously been shown to improve outcomes.

Design: Prospective time and motion study.

Setting: 11 geographically cohorted services and 4 noncohorted teams at Indiana University Health, a large academic medical center.

Synopsis: Geotracking was used to monitor time spent inside and outside of patient rooms for 17 hospitalists over at least 6 weeks. Eight hospitalists were also directly observed. Both groups spent roughly three times more time outside patient rooms than inside. Geographic cohorting was associated with longer patient visits (ranging from 69.6 to 101.7 minutes per day depending on team structure) and a higher percentage of time in patient rooms. Interruptions were more common with geographic cohorting. These hospitalists were interrupted every 14 minutes in the morning and every 8 minutes in the afternoon. Of these interruptions, 62% were face-to-face, 25% were electronic, and 13% were both simultaneously.

An important limitation of this study is that the investigators did not evaluate clinical outcomes or provider satisfaction. This may give some pause to the widespread push toward geographic cohorting.

Bottom line: More frequent interruptions may partially offset potential increases in patient-hospitalist interactions achieved through geographic cohorting.

Citation: Kara A et al. A time motion study evaluating the impact of geographic cohorting of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:338-44.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Geographic cohorting localizes hospitalist teams to a single unit. It has previously been shown to improve outcomes.

Design: Prospective time and motion study.

Setting: 11 geographically cohorted services and 4 noncohorted teams at Indiana University Health, a large academic medical center.

Synopsis: Geotracking was used to monitor time spent inside and outside of patient rooms for 17 hospitalists over at least 6 weeks. Eight hospitalists were also directly observed. Both groups spent roughly three times more time outside patient rooms than inside. Geographic cohorting was associated with longer patient visits (ranging from 69.6 to 101.7 minutes per day depending on team structure) and a higher percentage of time in patient rooms. Interruptions were more common with geographic cohorting. These hospitalists were interrupted every 14 minutes in the morning and every 8 minutes in the afternoon. Of these interruptions, 62% were face-to-face, 25% were electronic, and 13% were both simultaneously.

An important limitation of this study is that the investigators did not evaluate clinical outcomes or provider satisfaction. This may give some pause to the widespread push toward geographic cohorting.

Bottom line: More frequent interruptions may partially offset potential increases in patient-hospitalist interactions achieved through geographic cohorting.

Citation: Kara A et al. A time motion study evaluating the impact of geographic cohorting of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:338-44.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

No benefit from lower temps for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

The results “do not support the use of moderate therapeutic hypothermia to improve neurologic outcomes in comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” write the investigators led by Michel Le May, MD, from the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ontario, Canada.

The CAPITAL CHILL results were first presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2021 Scientific Sessions in May.

They have now been published online, October 19, in JAMA.

High rates of brain injury and death

Comatose survivors of OHCA have high rates of severe brain injury and death. Current guidelines recommend targeted temperature management at 32°C to 36°C for 24 hours. However, small studies have suggested a potential benefit of targeting lower body temperatures.

In the CAPITAL CHILL study of 367 OHCA patients who were comatose on admission, there were no statistically significant differences in the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality or poor neurologic outcome at 180 days with mild-versus-moderate hypothermia.

The primary composite outcome occurred in 89 of 184 (48.4%) patients in the moderate hypothermia group and 83 of 183 (45.4%) patients in the mild hypothermia group — a risk difference of 3.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.2% - 13.2%) and relative risk of 1.07 (95% CI, 0.86 - 1.33; P = .56).

There was also no significant difference when looking at the individual components of mortality (43.5% vs 41.0%) and poor neurologic outcome (Disability Rating Scale score >5: 4.9% vs 4.4%).

The baseline characteristics of patients were similar in the moderate and mild hypothermia groups. The lack of a significant difference in the primary outcome was consistent after adjusting for baseline covariates as well as across all subgroups.

The rates of secondary outcomes were also similar between the two groups, except for a longer length of stay in the intensive care unit in the moderate hypothermia group compared with the mild hypothermia group, which would likely add to overall costs.

The researchers note that the Targeted Hypothermia vs Targeted Normothermia After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (TTM2) trial recently reported that targeted hypothermia at 33°C did not improve survival at 180 days compared with targeted normothermia at 37.5°C or less.

The CAPITAL CHILL study “adds to the spectrum of target temperature management, as it did not find any benefit of even further lowering temperatures to 31°C,” the study team says.

They caution that most patients in the trial had cardiac arrest secondary to a primary cardiac etiology and therefore the findings may not be applicable to cardiac arrest of all etiologies.

It’s also possible that the trial was underpowered to detect clinically important differences between moderate and mild hypothermia. Also, the number of patients presenting with a nonshockable rhythm was relatively small, and further study may be worthwhile in this subgroup, they say.

For now, however, the CAPITAL CHILL results provide no support for a lower target temperature of 31°C to improve outcomes in OHCA patients, Dr. Le May and colleagues conclude.

CAPITAL CHILL was an investigator-initiated study and funding was provided by the University of Ottawa Heart Institute Cardiac Arrest Program. Dr. Le May has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results “do not support the use of moderate therapeutic hypothermia to improve neurologic outcomes in comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” write the investigators led by Michel Le May, MD, from the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ontario, Canada.

The CAPITAL CHILL results were first presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2021 Scientific Sessions in May.

They have now been published online, October 19, in JAMA.

High rates of brain injury and death

Comatose survivors of OHCA have high rates of severe brain injury and death. Current guidelines recommend targeted temperature management at 32°C to 36°C for 24 hours. However, small studies have suggested a potential benefit of targeting lower body temperatures.

In the CAPITAL CHILL study of 367 OHCA patients who were comatose on admission, there were no statistically significant differences in the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality or poor neurologic outcome at 180 days with mild-versus-moderate hypothermia.

The primary composite outcome occurred in 89 of 184 (48.4%) patients in the moderate hypothermia group and 83 of 183 (45.4%) patients in the mild hypothermia group — a risk difference of 3.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.2% - 13.2%) and relative risk of 1.07 (95% CI, 0.86 - 1.33; P = .56).

There was also no significant difference when looking at the individual components of mortality (43.5% vs 41.0%) and poor neurologic outcome (Disability Rating Scale score >5: 4.9% vs 4.4%).

The baseline characteristics of patients were similar in the moderate and mild hypothermia groups. The lack of a significant difference in the primary outcome was consistent after adjusting for baseline covariates as well as across all subgroups.

The rates of secondary outcomes were also similar between the two groups, except for a longer length of stay in the intensive care unit in the moderate hypothermia group compared with the mild hypothermia group, which would likely add to overall costs.

The researchers note that the Targeted Hypothermia vs Targeted Normothermia After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (TTM2) trial recently reported that targeted hypothermia at 33°C did not improve survival at 180 days compared with targeted normothermia at 37.5°C or less.

The CAPITAL CHILL study “adds to the spectrum of target temperature management, as it did not find any benefit of even further lowering temperatures to 31°C,” the study team says.

They caution that most patients in the trial had cardiac arrest secondary to a primary cardiac etiology and therefore the findings may not be applicable to cardiac arrest of all etiologies.

It’s also possible that the trial was underpowered to detect clinically important differences between moderate and mild hypothermia. Also, the number of patients presenting with a nonshockable rhythm was relatively small, and further study may be worthwhile in this subgroup, they say.

For now, however, the CAPITAL CHILL results provide no support for a lower target temperature of 31°C to improve outcomes in OHCA patients, Dr. Le May and colleagues conclude.

CAPITAL CHILL was an investigator-initiated study and funding was provided by the University of Ottawa Heart Institute Cardiac Arrest Program. Dr. Le May has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results “do not support the use of moderate therapeutic hypothermia to improve neurologic outcomes in comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” write the investigators led by Michel Le May, MD, from the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ontario, Canada.

The CAPITAL CHILL results were first presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2021 Scientific Sessions in May.

They have now been published online, October 19, in JAMA.

High rates of brain injury and death

Comatose survivors of OHCA have high rates of severe brain injury and death. Current guidelines recommend targeted temperature management at 32°C to 36°C for 24 hours. However, small studies have suggested a potential benefit of targeting lower body temperatures.

In the CAPITAL CHILL study of 367 OHCA patients who were comatose on admission, there were no statistically significant differences in the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality or poor neurologic outcome at 180 days with mild-versus-moderate hypothermia.

The primary composite outcome occurred in 89 of 184 (48.4%) patients in the moderate hypothermia group and 83 of 183 (45.4%) patients in the mild hypothermia group — a risk difference of 3.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.2% - 13.2%) and relative risk of 1.07 (95% CI, 0.86 - 1.33; P = .56).

There was also no significant difference when looking at the individual components of mortality (43.5% vs 41.0%) and poor neurologic outcome (Disability Rating Scale score >5: 4.9% vs 4.4%).

The baseline characteristics of patients were similar in the moderate and mild hypothermia groups. The lack of a significant difference in the primary outcome was consistent after adjusting for baseline covariates as well as across all subgroups.

The rates of secondary outcomes were also similar between the two groups, except for a longer length of stay in the intensive care unit in the moderate hypothermia group compared with the mild hypothermia group, which would likely add to overall costs.

The researchers note that the Targeted Hypothermia vs Targeted Normothermia After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (TTM2) trial recently reported that targeted hypothermia at 33°C did not improve survival at 180 days compared with targeted normothermia at 37.5°C or less.

The CAPITAL CHILL study “adds to the spectrum of target temperature management, as it did not find any benefit of even further lowering temperatures to 31°C,” the study team says.

They caution that most patients in the trial had cardiac arrest secondary to a primary cardiac etiology and therefore the findings may not be applicable to cardiac arrest of all etiologies.

It’s also possible that the trial was underpowered to detect clinically important differences between moderate and mild hypothermia. Also, the number of patients presenting with a nonshockable rhythm was relatively small, and further study may be worthwhile in this subgroup, they say.

For now, however, the CAPITAL CHILL results provide no support for a lower target temperature of 31°C to improve outcomes in OHCA patients, Dr. Le May and colleagues conclude.

CAPITAL CHILL was an investigator-initiated study and funding was provided by the University of Ottawa Heart Institute Cardiac Arrest Program. Dr. Le May has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves combo pill for severe, acute pain

enough to require an opioid analgesic and for which alternative treatments fail to provide adequate pain relief.

Celecoxib is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and tramadol is an opioid agonist. Seglentis contains 56 mg of celecoxib and 44 mg of tramadol.

“The unique co-crystal formulation of Seglentis provides effective pain relief via a multimodal approach,” Craig A. Sponseller, MD, chief medical officer of Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, said in a news release.

Esteve Pharmaceuticals has entered into an agreement with Kowa Pharmaceuticals America to commercialize the pain medicine in the United States, with a launch planned for early 2022.

“Seglentis uses four different and complementary mechanisms of analgesia and offers healthcare providers an important option to treat acute pain in adults that is severe enough to require opioid treatment and for which alternative treatments are inadequate,” Dr. Sponseller said.

Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, even at recommended doses, the FDA will require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for Seglentis.

The label states that the drug should be initiated as two tablets every 12 hours as needed and should be prescribed for the shortest duration consistent with individual patient treatment goals.

Patients should be monitored for respiratory depression, especially within the first 24 to 72 hours of initiating therapy with Seglentis.

Prescribers should discuss naloxone (Narcan) with patients and consider prescribing the opioid antagonist naloxone based on the patient’s risk factors for overdose.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

enough to require an opioid analgesic and for which alternative treatments fail to provide adequate pain relief.

Celecoxib is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and tramadol is an opioid agonist. Seglentis contains 56 mg of celecoxib and 44 mg of tramadol.

“The unique co-crystal formulation of Seglentis provides effective pain relief via a multimodal approach,” Craig A. Sponseller, MD, chief medical officer of Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, said in a news release.

Esteve Pharmaceuticals has entered into an agreement with Kowa Pharmaceuticals America to commercialize the pain medicine in the United States, with a launch planned for early 2022.

“Seglentis uses four different and complementary mechanisms of analgesia and offers healthcare providers an important option to treat acute pain in adults that is severe enough to require opioid treatment and for which alternative treatments are inadequate,” Dr. Sponseller said.

Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, even at recommended doses, the FDA will require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for Seglentis.

The label states that the drug should be initiated as two tablets every 12 hours as needed and should be prescribed for the shortest duration consistent with individual patient treatment goals.

Patients should be monitored for respiratory depression, especially within the first 24 to 72 hours of initiating therapy with Seglentis.

Prescribers should discuss naloxone (Narcan) with patients and consider prescribing the opioid antagonist naloxone based on the patient’s risk factors for overdose.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

enough to require an opioid analgesic and for which alternative treatments fail to provide adequate pain relief.

Celecoxib is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and tramadol is an opioid agonist. Seglentis contains 56 mg of celecoxib and 44 mg of tramadol.

“The unique co-crystal formulation of Seglentis provides effective pain relief via a multimodal approach,” Craig A. Sponseller, MD, chief medical officer of Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, said in a news release.

Esteve Pharmaceuticals has entered into an agreement with Kowa Pharmaceuticals America to commercialize the pain medicine in the United States, with a launch planned for early 2022.

“Seglentis uses four different and complementary mechanisms of analgesia and offers healthcare providers an important option to treat acute pain in adults that is severe enough to require opioid treatment and for which alternative treatments are inadequate,” Dr. Sponseller said.

Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, even at recommended doses, the FDA will require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for Seglentis.

The label states that the drug should be initiated as two tablets every 12 hours as needed and should be prescribed for the shortest duration consistent with individual patient treatment goals.

Patients should be monitored for respiratory depression, especially within the first 24 to 72 hours of initiating therapy with Seglentis.

Prescribers should discuss naloxone (Narcan) with patients and consider prescribing the opioid antagonist naloxone based on the patient’s risk factors for overdose.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

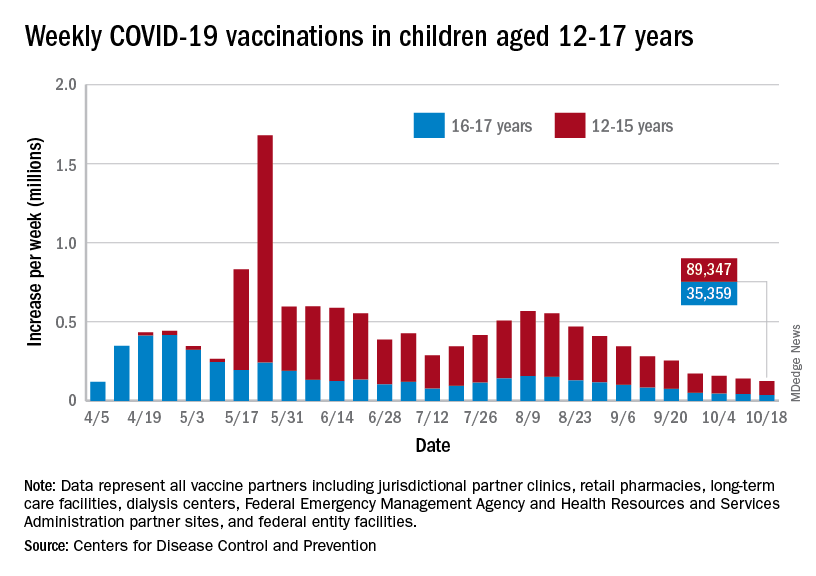

Children and COVID: Vaccinations lower than ever as cases continue to drop

As the COVID-19 vaccine heads toward approval for children under age 12 years, the number of older children receiving it dropped for the 10th consecutive week, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Over 47% of all children aged 12-17 years – that’s close to 12 million eligible individuals – have not received even one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and less than 44% (about 11.1 million) were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 18, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

, when eligibility expanded to include 12- to 15-year-olds, according to the CDC data, which also show that weekly vaccinations have never been lower.

Fortunately, the decline in new cases also continued, as the national total fell for a 6th straight week. There were more than 130,000 child cases reported during the week of Oct. 8-14, compared with 148,000 the previous week and the high of almost 252,000 in late August/early September, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

That brings the cumulative count to 6.18 million, with children accounting for 16.4% of all cases reported since the start of the pandemic. For the week of Oct. 8-14, children represented 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases in the 46 states with up-to-date online dashboards, the AAP and CHA said, noting that New York has never reported age ranges for cases and that Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer.

Current data indicate that child cases in California now exceed 671,000, more than any other state, followed by Florida with 439,000 (the state defines a child as someone aged 0-14 years) and Illinois with 301,000. Vermont has the highest proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children (24.3%), with Alaska (24.1%) and South Carolina (23.2%) just behind. The highest rate of cases – 15,569 per 100,000 children – can be found in South Carolina, while the lowest is in Hawaii (4,838 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA reported.

The total number of COVID-related deaths in children is 681 as of Oct. 18, according to the CDC, with the AAP/CHA reporting 558 as of Oct. 14, based on data from 45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The CDC reports 65,655 admissions since Aug. 1, 2020, in children aged 0-17 years, and the AAP/CHA tally 23,582 since May 5, 2020, among children in 24 states and New York City.

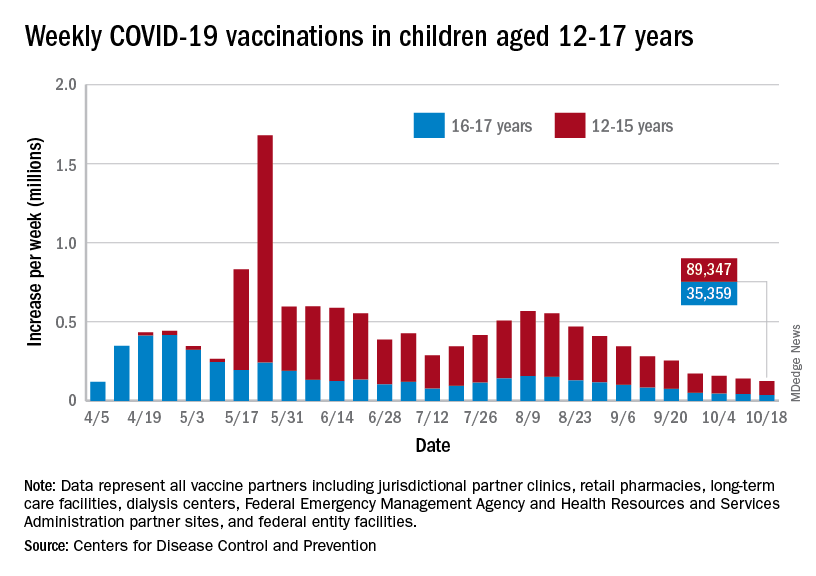

As the COVID-19 vaccine heads toward approval for children under age 12 years, the number of older children receiving it dropped for the 10th consecutive week, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Over 47% of all children aged 12-17 years – that’s close to 12 million eligible individuals – have not received even one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and less than 44% (about 11.1 million) were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 18, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

, when eligibility expanded to include 12- to 15-year-olds, according to the CDC data, which also show that weekly vaccinations have never been lower.

Fortunately, the decline in new cases also continued, as the national total fell for a 6th straight week. There were more than 130,000 child cases reported during the week of Oct. 8-14, compared with 148,000 the previous week and the high of almost 252,000 in late August/early September, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

That brings the cumulative count to 6.18 million, with children accounting for 16.4% of all cases reported since the start of the pandemic. For the week of Oct. 8-14, children represented 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases in the 46 states with up-to-date online dashboards, the AAP and CHA said, noting that New York has never reported age ranges for cases and that Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer.

Current data indicate that child cases in California now exceed 671,000, more than any other state, followed by Florida with 439,000 (the state defines a child as someone aged 0-14 years) and Illinois with 301,000. Vermont has the highest proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children (24.3%), with Alaska (24.1%) and South Carolina (23.2%) just behind. The highest rate of cases – 15,569 per 100,000 children – can be found in South Carolina, while the lowest is in Hawaii (4,838 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA reported.

The total number of COVID-related deaths in children is 681 as of Oct. 18, according to the CDC, with the AAP/CHA reporting 558 as of Oct. 14, based on data from 45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The CDC reports 65,655 admissions since Aug. 1, 2020, in children aged 0-17 years, and the AAP/CHA tally 23,582 since May 5, 2020, among children in 24 states and New York City.

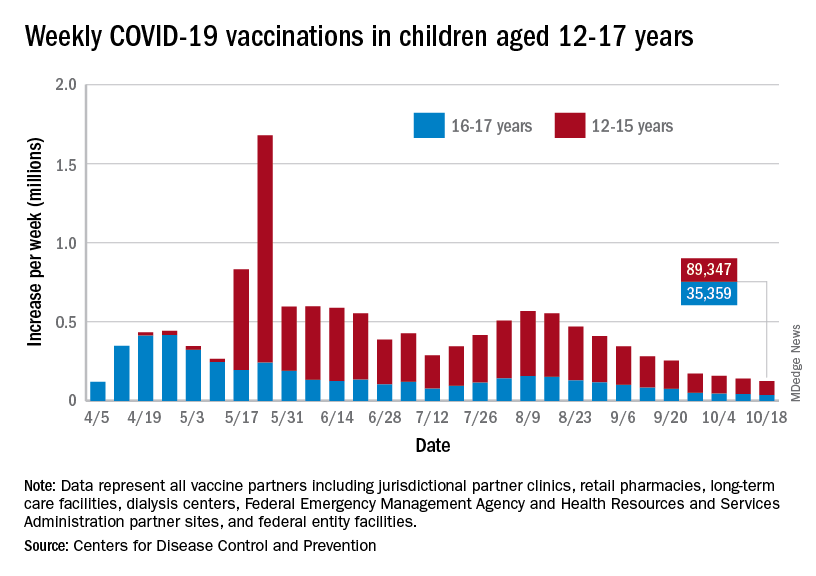

As the COVID-19 vaccine heads toward approval for children under age 12 years, the number of older children receiving it dropped for the 10th consecutive week, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Over 47% of all children aged 12-17 years – that’s close to 12 million eligible individuals – have not received even one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and less than 44% (about 11.1 million) were fully vaccinated as of Oct. 18, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

, when eligibility expanded to include 12- to 15-year-olds, according to the CDC data, which also show that weekly vaccinations have never been lower.

Fortunately, the decline in new cases also continued, as the national total fell for a 6th straight week. There were more than 130,000 child cases reported during the week of Oct. 8-14, compared with 148,000 the previous week and the high of almost 252,000 in late August/early September, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

That brings the cumulative count to 6.18 million, with children accounting for 16.4% of all cases reported since the start of the pandemic. For the week of Oct. 8-14, children represented 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases in the 46 states with up-to-date online dashboards, the AAP and CHA said, noting that New York has never reported age ranges for cases and that Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer.

Current data indicate that child cases in California now exceed 671,000, more than any other state, followed by Florida with 439,000 (the state defines a child as someone aged 0-14 years) and Illinois with 301,000. Vermont has the highest proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children (24.3%), with Alaska (24.1%) and South Carolina (23.2%) just behind. The highest rate of cases – 15,569 per 100,000 children – can be found in South Carolina, while the lowest is in Hawaii (4,838 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA reported.

The total number of COVID-related deaths in children is 681 as of Oct. 18, according to the CDC, with the AAP/CHA reporting 558 as of Oct. 14, based on data from 45 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The CDC reports 65,655 admissions since Aug. 1, 2020, in children aged 0-17 years, and the AAP/CHA tally 23,582 since May 5, 2020, among children in 24 states and New York City.

Open ICUs giveth and taketh away

Background: Some academic medical centers and many community centers use “open” ICU models in which primary services longitudinally follow patients into the ICU with intensivist comanagement.

Design: Semistructured interviews with 12 hospitalists and 8 intensivists.

Setting: Open 16-bed ICUs at the University of California, San Francisco. Teams round separately at the bedside and are informally encouraged to check in daily.

Synopsis: The authors iteratively developed the interview questions. Participants were selected using purposive sampling. The main themes were communication, education, and structure. Communication was challenging among teams as well as with patients and families. The open ICU was felt to affect handoffs and care continuity positively. Hospitalists focused more on longitudinal relationships, smoother transitions, and opportunities to observe disease evolution. Intensivists focused more on fragmentation during the ICU stay and noted cognitive disengagement among some team members with certain aspects of patient care. Intensivists did not identify any educational or structural benefits of the open ICU model.

This is the first qualitative study of hospitalist and intensivist perceptions of the open ICU model. The most significant limitation is the risk of bias from the single-center design and purposive sampling. These findings have implications for other models of medical comanagement.

Bottom line: Open ICU models offer a mix of communication, educational, and structural barriers as well as opportunities. Role clarity may help optimize the open ICU model.

Citation: Santhosh L and Sewell J. Hospital and intensivist experiences of the “open” intensive care unit environment: A qualitative exploration. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2338-46.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Some academic medical centers and many community centers use “open” ICU models in which primary services longitudinally follow patients into the ICU with intensivist comanagement.

Design: Semistructured interviews with 12 hospitalists and 8 intensivists.

Setting: Open 16-bed ICUs at the University of California, San Francisco. Teams round separately at the bedside and are informally encouraged to check in daily.

Synopsis: The authors iteratively developed the interview questions. Participants were selected using purposive sampling. The main themes were communication, education, and structure. Communication was challenging among teams as well as with patients and families. The open ICU was felt to affect handoffs and care continuity positively. Hospitalists focused more on longitudinal relationships, smoother transitions, and opportunities to observe disease evolution. Intensivists focused more on fragmentation during the ICU stay and noted cognitive disengagement among some team members with certain aspects of patient care. Intensivists did not identify any educational or structural benefits of the open ICU model.

This is the first qualitative study of hospitalist and intensivist perceptions of the open ICU model. The most significant limitation is the risk of bias from the single-center design and purposive sampling. These findings have implications for other models of medical comanagement.

Bottom line: Open ICU models offer a mix of communication, educational, and structural barriers as well as opportunities. Role clarity may help optimize the open ICU model.

Citation: Santhosh L and Sewell J. Hospital and intensivist experiences of the “open” intensive care unit environment: A qualitative exploration. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2338-46.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Some academic medical centers and many community centers use “open” ICU models in which primary services longitudinally follow patients into the ICU with intensivist comanagement.

Design: Semistructured interviews with 12 hospitalists and 8 intensivists.

Setting: Open 16-bed ICUs at the University of California, San Francisco. Teams round separately at the bedside and are informally encouraged to check in daily.

Synopsis: The authors iteratively developed the interview questions. Participants were selected using purposive sampling. The main themes were communication, education, and structure. Communication was challenging among teams as well as with patients and families. The open ICU was felt to affect handoffs and care continuity positively. Hospitalists focused more on longitudinal relationships, smoother transitions, and opportunities to observe disease evolution. Intensivists focused more on fragmentation during the ICU stay and noted cognitive disengagement among some team members with certain aspects of patient care. Intensivists did not identify any educational or structural benefits of the open ICU model.

This is the first qualitative study of hospitalist and intensivist perceptions of the open ICU model. The most significant limitation is the risk of bias from the single-center design and purposive sampling. These findings have implications for other models of medical comanagement.

Bottom line: Open ICU models offer a mix of communication, educational, and structural barriers as well as opportunities. Role clarity may help optimize the open ICU model.

Citation: Santhosh L and Sewell J. Hospital and intensivist experiences of the “open” intensive care unit environment: A qualitative exploration. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2338-46.

Dr. Sweigart is a hospitalist at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Mortality in 2nd wave higher with ECMO for COVID-ARDS

For patients with refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by COVID-19 infections, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be the treatment of last resort.

But for reasons that aren’t clear, in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic at a major teaching hospital, the mortality rate of patients on ECMO for COVID-induced ARDS was significantly higher than it was during the first wave, despite changes in drug therapy and clinical management, reported Rohit Reddy, BS, a second-year medical student, and colleagues at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

During the first wave, from April to September 2020, the survival rate of patients while on ECMO in their ICUs was 67%. In contrast, for patients treated during the second wave, from November 2020 to March 2021, the ECMO survival rate was 31% (P = .003).

The 30-day survival rates were also higher in the first wave compared with the second, at 54% versus 31%, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“More research is required to develop stricter inclusion/exclusion criteria and to improve pre-ECMO management in order to improve outcomes,” Mr. Reddy said in a narrated poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

ARDS severity higher

ARDS is a major complication of COVID-19 infections, and there is evidence to suggest that COVID-associated ARDS is more severe than ARDS caused by other causes, the investigators noted.

“ECMO, which has been used as a rescue therapy in prior viral outbreaks, has been used to support certain patients with refractory ARDS due to COVID-19, but evidence for its efficacy is limited. Respiratory failure remained a highly concerning complication in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is unclear how the evolution of the disease and pharmacologic utility has affected the clinical utility of ECMO,” Mr. Reddy said.

To see whether changes in disease course or in treatment could explain changes in outcomes for patients with COVID-related ARDS, the investigators compared characteristics and outcomes for patients treated in the first versus second waves of the pandemic. Their study did not include data from patients infected with the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which became the predominant viral strain later in 2021.

The study included data on 28 patients treated during the first wave, and 13 during the second. The sample included 28 men and 13 women with a mean age of 51 years.

All patients had venovenous ECMO, with cannulation in the femoral or internal jugular veins; some patients received ECMO via a single double-lumen cannula.

There were no significant differences between the two time periods in patient comorbidities prior to initiation of ECMO.

Patients in the second wave were significantly more likely to receive steroids (54% vs. 100%; P = .003) and remdesivir (39% vs. 85%; P = .007). Prone positioning before ECMO was also significantly more frequent in the second wave (11% vs. 85%; P < .001).

Patients in the second wave stayed on ECMO longer – median 20 days versus 14 days for first-wave patients – but as noted before, ECMO mortality rates were significantly higher during the second wave. During the first wave, 33% of patients died while on ECMO, compared with 69% in the second wave (P = .03). Respective 30-day mortality rates were 46% versus 69% (ns).

Rates of complications during ECMO were generally comparable between the groups, including acute renal failure (39% in the first wave vs 38% in the second), sepsis (32% vs. 23%), bacterial pneumonia (11% vs. 8%), and gastrointestinal bleeding (21% vs. 15%). However, significantly more patients in the second wave had cerebral vascular accidents (4% vs. 23%; P = .050).

Senior author Hitoshi Hirose, MD, PhD, professor of surgery at Thomas Jefferson University, said in an interview that the difference in outcomes was likely caused by changes in pre-ECMO therapy between the first and second waves.

“Our study showed the incidence of sepsis had a large impact on the patient outcomes,” he wrote. “We speculate that sepsis was attributed to use of immune modulation therapy. The prevention of the sepsis would be key to improve survival of ECMO for COVID 19.”

“It’s possible that the explanation for this is that patients in the second wave were sicker in a way that wasn’t adequately measured in the first wave,” CHEST 2021 program cochair Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, from Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, said in an interview.

The differences may also have been attributable to changes in virulence, or to clinical decisions to put sicker patients on ECMO, he said.

Casey Cable, MD, MSc, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist at Virginia Commonwealth Medical Center in Richmond, also speculated in an interview that second-wave patients may have been sicker.

“One interesting piece of this story is that we now know a lot more – we know about the use of steroids plus or minus remdesivir and proning, and patients received a large majority of those treatments but still got put on ECMO,” she said. “I wonder if there is a subset of really sick patients, and no matter what we treat with – steroids, proning – whatever we do they’re just not going to do well.”

Both Dr. Carroll and Dr. Cable emphasized the importance of ECMO as a rescue therapy for patients with severe, refractory ARDS associated with COVID-19 or other diseases.

Neither Dr. Carroll nor Dr. Cable were involved in the study.

No study funding was reported. Mr. Reddy, Dr. Hirose, Dr. Carroll, and Dr. Cable disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by COVID-19 infections, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be the treatment of last resort.

But for reasons that aren’t clear, in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic at a major teaching hospital, the mortality rate of patients on ECMO for COVID-induced ARDS was significantly higher than it was during the first wave, despite changes in drug therapy and clinical management, reported Rohit Reddy, BS, a second-year medical student, and colleagues at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

During the first wave, from April to September 2020, the survival rate of patients while on ECMO in their ICUs was 67%. In contrast, for patients treated during the second wave, from November 2020 to March 2021, the ECMO survival rate was 31% (P = .003).

The 30-day survival rates were also higher in the first wave compared with the second, at 54% versus 31%, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“More research is required to develop stricter inclusion/exclusion criteria and to improve pre-ECMO management in order to improve outcomes,” Mr. Reddy said in a narrated poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

ARDS severity higher

ARDS is a major complication of COVID-19 infections, and there is evidence to suggest that COVID-associated ARDS is more severe than ARDS caused by other causes, the investigators noted.

“ECMO, which has been used as a rescue therapy in prior viral outbreaks, has been used to support certain patients with refractory ARDS due to COVID-19, but evidence for its efficacy is limited. Respiratory failure remained a highly concerning complication in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is unclear how the evolution of the disease and pharmacologic utility has affected the clinical utility of ECMO,” Mr. Reddy said.

To see whether changes in disease course or in treatment could explain changes in outcomes for patients with COVID-related ARDS, the investigators compared characteristics and outcomes for patients treated in the first versus second waves of the pandemic. Their study did not include data from patients infected with the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which became the predominant viral strain later in 2021.

The study included data on 28 patients treated during the first wave, and 13 during the second. The sample included 28 men and 13 women with a mean age of 51 years.

All patients had venovenous ECMO, with cannulation in the femoral or internal jugular veins; some patients received ECMO via a single double-lumen cannula.

There were no significant differences between the two time periods in patient comorbidities prior to initiation of ECMO.

Patients in the second wave were significantly more likely to receive steroids (54% vs. 100%; P = .003) and remdesivir (39% vs. 85%; P = .007). Prone positioning before ECMO was also significantly more frequent in the second wave (11% vs. 85%; P < .001).

Patients in the second wave stayed on ECMO longer – median 20 days versus 14 days for first-wave patients – but as noted before, ECMO mortality rates were significantly higher during the second wave. During the first wave, 33% of patients died while on ECMO, compared with 69% in the second wave (P = .03). Respective 30-day mortality rates were 46% versus 69% (ns).

Rates of complications during ECMO were generally comparable between the groups, including acute renal failure (39% in the first wave vs 38% in the second), sepsis (32% vs. 23%), bacterial pneumonia (11% vs. 8%), and gastrointestinal bleeding (21% vs. 15%). However, significantly more patients in the second wave had cerebral vascular accidents (4% vs. 23%; P = .050).

Senior author Hitoshi Hirose, MD, PhD, professor of surgery at Thomas Jefferson University, said in an interview that the difference in outcomes was likely caused by changes in pre-ECMO therapy between the first and second waves.

“Our study showed the incidence of sepsis had a large impact on the patient outcomes,” he wrote. “We speculate that sepsis was attributed to use of immune modulation therapy. The prevention of the sepsis would be key to improve survival of ECMO for COVID 19.”

“It’s possible that the explanation for this is that patients in the second wave were sicker in a way that wasn’t adequately measured in the first wave,” CHEST 2021 program cochair Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, from Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, said in an interview.

The differences may also have been attributable to changes in virulence, or to clinical decisions to put sicker patients on ECMO, he said.

Casey Cable, MD, MSc, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist at Virginia Commonwealth Medical Center in Richmond, also speculated in an interview that second-wave patients may have been sicker.

“One interesting piece of this story is that we now know a lot more – we know about the use of steroids plus or minus remdesivir and proning, and patients received a large majority of those treatments but still got put on ECMO,” she said. “I wonder if there is a subset of really sick patients, and no matter what we treat with – steroids, proning – whatever we do they’re just not going to do well.”

Both Dr. Carroll and Dr. Cable emphasized the importance of ECMO as a rescue therapy for patients with severe, refractory ARDS associated with COVID-19 or other diseases.

Neither Dr. Carroll nor Dr. Cable were involved in the study.

No study funding was reported. Mr. Reddy, Dr. Hirose, Dr. Carroll, and Dr. Cable disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by COVID-19 infections, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be the treatment of last resort.

But for reasons that aren’t clear, in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic at a major teaching hospital, the mortality rate of patients on ECMO for COVID-induced ARDS was significantly higher than it was during the first wave, despite changes in drug therapy and clinical management, reported Rohit Reddy, BS, a second-year medical student, and colleagues at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

During the first wave, from April to September 2020, the survival rate of patients while on ECMO in their ICUs was 67%. In contrast, for patients treated during the second wave, from November 2020 to March 2021, the ECMO survival rate was 31% (P = .003).

The 30-day survival rates were also higher in the first wave compared with the second, at 54% versus 31%, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“More research is required to develop stricter inclusion/exclusion criteria and to improve pre-ECMO management in order to improve outcomes,” Mr. Reddy said in a narrated poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held virtually this year.

ARDS severity higher

ARDS is a major complication of COVID-19 infections, and there is evidence to suggest that COVID-associated ARDS is more severe than ARDS caused by other causes, the investigators noted.

“ECMO, which has been used as a rescue therapy in prior viral outbreaks, has been used to support certain patients with refractory ARDS due to COVID-19, but evidence for its efficacy is limited. Respiratory failure remained a highly concerning complication in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is unclear how the evolution of the disease and pharmacologic utility has affected the clinical utility of ECMO,” Mr. Reddy said.

To see whether changes in disease course or in treatment could explain changes in outcomes for patients with COVID-related ARDS, the investigators compared characteristics and outcomes for patients treated in the first versus second waves of the pandemic. Their study did not include data from patients infected with the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which became the predominant viral strain later in 2021.

The study included data on 28 patients treated during the first wave, and 13 during the second. The sample included 28 men and 13 women with a mean age of 51 years.

All patients had venovenous ECMO, with cannulation in the femoral or internal jugular veins; some patients received ECMO via a single double-lumen cannula.

There were no significant differences between the two time periods in patient comorbidities prior to initiation of ECMO.

Patients in the second wave were significantly more likely to receive steroids (54% vs. 100%; P = .003) and remdesivir (39% vs. 85%; P = .007). Prone positioning before ECMO was also significantly more frequent in the second wave (11% vs. 85%; P < .001).

Patients in the second wave stayed on ECMO longer – median 20 days versus 14 days for first-wave patients – but as noted before, ECMO mortality rates were significantly higher during the second wave. During the first wave, 33% of patients died while on ECMO, compared with 69% in the second wave (P = .03). Respective 30-day mortality rates were 46% versus 69% (ns).

Rates of complications during ECMO were generally comparable between the groups, including acute renal failure (39% in the first wave vs 38% in the second), sepsis (32% vs. 23%), bacterial pneumonia (11% vs. 8%), and gastrointestinal bleeding (21% vs. 15%). However, significantly more patients in the second wave had cerebral vascular accidents (4% vs. 23%; P = .050).

Senior author Hitoshi Hirose, MD, PhD, professor of surgery at Thomas Jefferson University, said in an interview that the difference in outcomes was likely caused by changes in pre-ECMO therapy between the first and second waves.

“Our study showed the incidence of sepsis had a large impact on the patient outcomes,” he wrote. “We speculate that sepsis was attributed to use of immune modulation therapy. The prevention of the sepsis would be key to improve survival of ECMO for COVID 19.”

“It’s possible that the explanation for this is that patients in the second wave were sicker in a way that wasn’t adequately measured in the first wave,” CHEST 2021 program cochair Christopher Carroll, MD, FCCP, from Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford, said in an interview.

The differences may also have been attributable to changes in virulence, or to clinical decisions to put sicker patients on ECMO, he said.

Casey Cable, MD, MSc, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist at Virginia Commonwealth Medical Center in Richmond, also speculated in an interview that second-wave patients may have been sicker.

“One interesting piece of this story is that we now know a lot more – we know about the use of steroids plus or minus remdesivir and proning, and patients received a large majority of those treatments but still got put on ECMO,” she said. “I wonder if there is a subset of really sick patients, and no matter what we treat with – steroids, proning – whatever we do they’re just not going to do well.”

Both Dr. Carroll and Dr. Cable emphasized the importance of ECMO as a rescue therapy for patients with severe, refractory ARDS associated with COVID-19 or other diseases.

Neither Dr. Carroll nor Dr. Cable were involved in the study.

No study funding was reported. Mr. Reddy, Dr. Hirose, Dr. Carroll, and Dr. Cable disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Universal masking of health care workers decreases SARS-CoV-2 positivity

Background: Many health care facilities have instituted universal masking policies for health care workers while also systematically testing any symptomatic health care workers. There is a paucity of data examining the effectiveness of universal masking policies in reducing COVID positivity among health care workers.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A database of 9,850 COVID-tested health care workers in Mass General Brigham health care system from March 1 to April 30, 2020.

Synopsis: The study compared weighted mean changes in daily COVID-positive test rates between the pre-masking and post-masking time frame, allowing for a transition period between the two time frames. During the pre-masking period, the weighted mean increased by 1.16% per day. During the post-masking period, the weighted mean decreased 0.49% per day. The net slope change was 1.65% (95% CI, 1.13%-2.15%; P < .001), indicating universal masking resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the daily positive test rate among health care workers.

This study is limited by the retrospective cohort, nonrandomized design. Potential confounders include other infection-control measures such as limiting elective procedures, social distancing, and increasing masking in the general population. It is also unclear that a symptomatic testing database is generalizable to the asymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers.

Bottom line: Universal masking policy for health care workers appears to decrease the COVID-positive test rates among symptomatic health care workers.

Citation: Wang X et al. Association between universal masking in a health care system and SARS-CoV-2 positivity among health care workers. JAMA. 2020;324(7):703-4.

Dr. Ouyang is a hospitalist and chief of the hospitalist section at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Many health care facilities have instituted universal masking policies for health care workers while also systematically testing any symptomatic health care workers. There is a paucity of data examining the effectiveness of universal masking policies in reducing COVID positivity among health care workers.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A database of 9,850 COVID-tested health care workers in Mass General Brigham health care system from March 1 to April 30, 2020.

Synopsis: The study compared weighted mean changes in daily COVID-positive test rates between the pre-masking and post-masking time frame, allowing for a transition period between the two time frames. During the pre-masking period, the weighted mean increased by 1.16% per day. During the post-masking period, the weighted mean decreased 0.49% per day. The net slope change was 1.65% (95% CI, 1.13%-2.15%; P < .001), indicating universal masking resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the daily positive test rate among health care workers.

This study is limited by the retrospective cohort, nonrandomized design. Potential confounders include other infection-control measures such as limiting elective procedures, social distancing, and increasing masking in the general population. It is also unclear that a symptomatic testing database is generalizable to the asymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers.

Bottom line: Universal masking policy for health care workers appears to decrease the COVID-positive test rates among symptomatic health care workers.

Citation: Wang X et al. Association between universal masking in a health care system and SARS-CoV-2 positivity among health care workers. JAMA. 2020;324(7):703-4.

Dr. Ouyang is a hospitalist and chief of the hospitalist section at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Background: Many health care facilities have instituted universal masking policies for health care workers while also systematically testing any symptomatic health care workers. There is a paucity of data examining the effectiveness of universal masking policies in reducing COVID positivity among health care workers.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A database of 9,850 COVID-tested health care workers in Mass General Brigham health care system from March 1 to April 30, 2020.

Synopsis: The study compared weighted mean changes in daily COVID-positive test rates between the pre-masking and post-masking time frame, allowing for a transition period between the two time frames. During the pre-masking period, the weighted mean increased by 1.16% per day. During the post-masking period, the weighted mean decreased 0.49% per day. The net slope change was 1.65% (95% CI, 1.13%-2.15%; P < .001), indicating universal masking resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the daily positive test rate among health care workers.

This study is limited by the retrospective cohort, nonrandomized design. Potential confounders include other infection-control measures such as limiting elective procedures, social distancing, and increasing masking in the general population. It is also unclear that a symptomatic testing database is generalizable to the asymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers.

Bottom line: Universal masking policy for health care workers appears to decrease the COVID-positive test rates among symptomatic health care workers.

Citation: Wang X et al. Association between universal masking in a health care system and SARS-CoV-2 positivity among health care workers. JAMA. 2020;324(7):703-4.

Dr. Ouyang is a hospitalist and chief of the hospitalist section at the Lexington (Ky.) VA Health Care System.

Biomarkers may indicate severity of COVID in children

Two biomarkers could potentially indicate which children with SARS-CoV-2 infection will develop severe disease, according to research presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“Most children with COVID-19 present with common symptoms, such as fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which are very similar to other common viruses,” said senior researcher Usha Sethuraman, MD, professor of pediatric emergency medicine at Central Michigan University in Detroit.

“It is impossible, in many instances, to predict which child, even after identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection, is going to develop severe consequences, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome [MIS-C] or severe pneumonia,” she said in an interview.

“In fact, many of these kids have been sent home the first time around as they appeared clinically well, only to return a couple of days later in cardiogenic shock and requiring invasive interventions,” she added. “It would be invaluable to have the ability to know which child is likely to develop severe infection so appropriate disposition can be made and treatment initiated.”

In their prospective observational cohort study, Dr. Sethuraman and her colleagues collected saliva samples from children and adolescents when they were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. They assessed the saliva for micro (mi)RNAs, which are small noncoding RNAs that help regulate gene expression and are “thought to play a role in the regulation of inflammation following an infection,” the researchers write in their poster.

Of the 129 young people assessed, 32 (25%) developed severe infection and 97 (75%) did not. The researchers defined severe infection as an MIS-C diagnosis, death in the 30 days after diagnosis, or the need for at least 2 L of oxygen, inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The expression of 63 miRNAs was significantly different between young people who developed severe infection and those who did not (P < .05). In cases of severe disease, expression was downregulated for 38 of the 63 miRNAs (60%).

“A model of six miRNAs was able to discriminate between severe and nonsevere infections with high sensitivity and accuracy in a preliminary analysis,” Dr. Sethuraman reported. “While salivary miRNA has been shown in other studies to help differentiate persistent concussion in children, we did not expect them to be downregulated in children with severe COVID-19.”