User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency for the hospitalist

Consider OIAI, even among patients with common infections

Case

A 60-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer using morphine extended release 30 mg twice daily and as-needed oxycodone for cancer-related pain presents with fever, dyspnea, and productive cough for 2 days. She also notes several weeks of fatigue, nausea, weight loss, and orthostatic lightheadedness. She is found to have pneumonia and is admitted for intravenous antibiotics. She remains borderline hypotensive after intravenous fluids and the hospitalist suspects opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency (OIAI).

How is OIAI diagnosed and managed?

Brief overview of issue

In the United States, 5.4% of the population is currently using long-term opioids.1 Patients using high doses of opioids for greater than 3 months are 40%-50% more likely to be hospitalized than those on a lower dose or no opioids.2 Hospitalists frequently encounter common opioid side effects such as constipation, nausea, and drowsiness, but may be less familiar with their effects on the endocrine system. Chronic, high-dose opioids can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and cause secondary, or central, adrenal insufficiency (AI).1

Recognition of OIAI is critical given the current opioid epidemic and life-threatening consequences of AI in systemically ill patients. While high-dose opioids may acutely suppress the HPA axis,3 OIAI is more commonly associated with long-term opioid use.4 The prevalence of OIAI among patients receiving long-term opioids ranges from 8.3% to 29%. This range reflects variations in opioid dose, duration of use, and different methods of assessing the HPA axis.1,4 When screening for HPA axis suppression in subjects taking chronic opioids, Lamprecht and colleagues found a prevalence of 22.5%.5 In comparison, Gibb and colleagues found the prevalence of secondary AI to be 8.3% in patients enrolled in a chronic pain clinic.6 Despite the high prevalence on biochemical screening, the clinical significance of OIAI is less clear. Clinical AI and adrenal crisis among patients on opioids are less frequent and mostly limited to case reports.7,8 In one retrospective cohort, one in 40 patients with OIAI presented with adrenal crisis during a hospitalization for viral gastroenteritis.9

With this prevalence, one would expect to diagnose OIAI more commonly in hospitalized patients. A concerning possibility is that this diagnosis is underrecognized because of either a lack of knowledge of the disease or the clinical overlap between the nonspecific symptoms of AI and other diagnoses. In patients reporting symptoms suggestive of OIAI, the diagnosis was delayed by a median of 12 months.9 The challenge for the hospitalist is to consider OIAI, even among patients with common infections such as pneumonia, viral gastroenteritis, or endocarditis who present with these nonspecific symptoms, while also avoiding unnecessary testing and treatment with glucocorticoids.

Overview of the data

Opiates and opioids exert their physiologic effect through activation of the mu, kappa, and delta receptors. These receptors are located throughout the body, including the hypothalamus and pituitary gland.4 Activation of these receptors results in tonic inhibition of the HPA axis and results in central AI.4 Central AI is characterized by a low a.m. cortisol, low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and low dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels.1,4 The low ACTH is indicative of central etiology. This effect of opioids is likely dose dependent with patients using more than 60 morphine-equivalent daily dose at greater risk.1,5

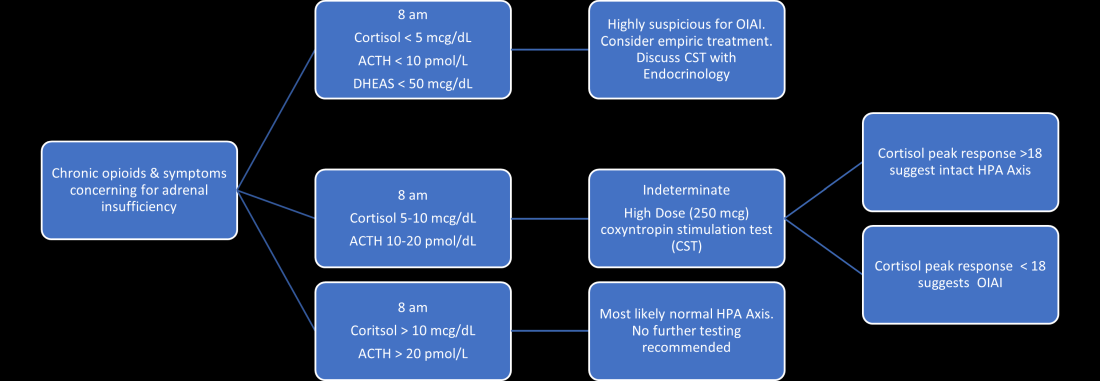

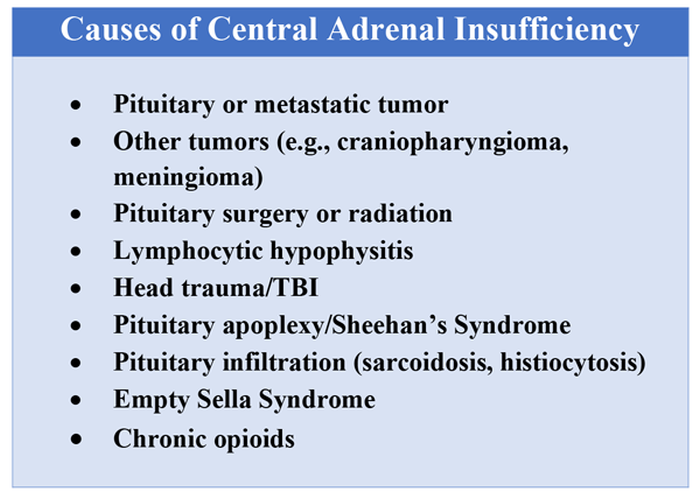

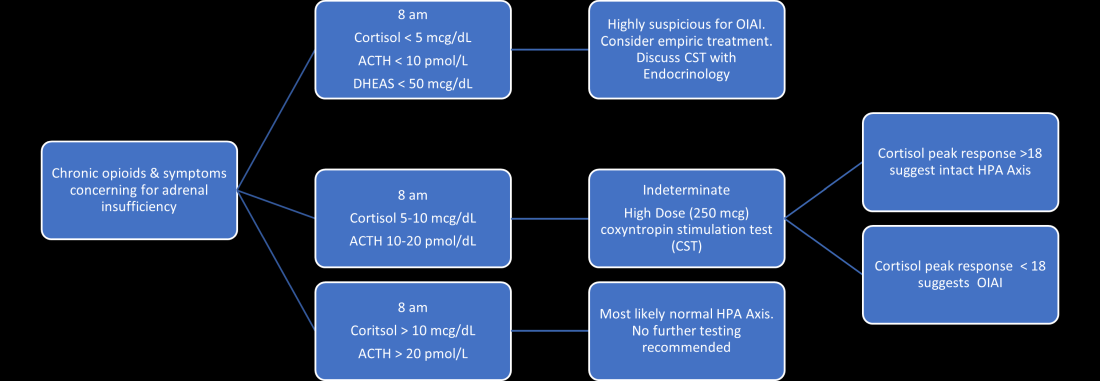

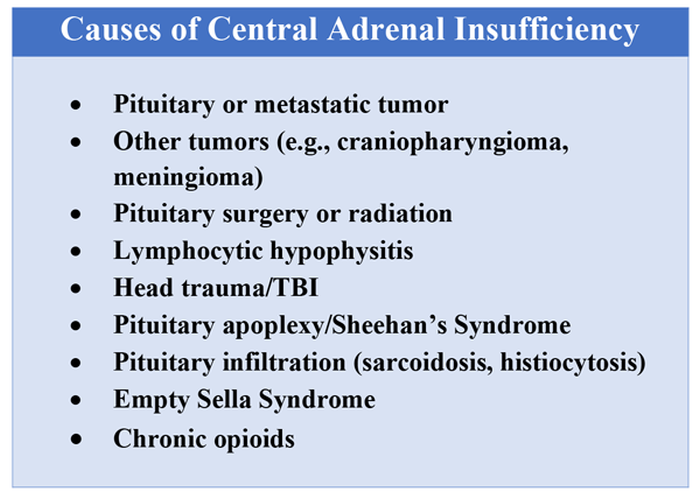

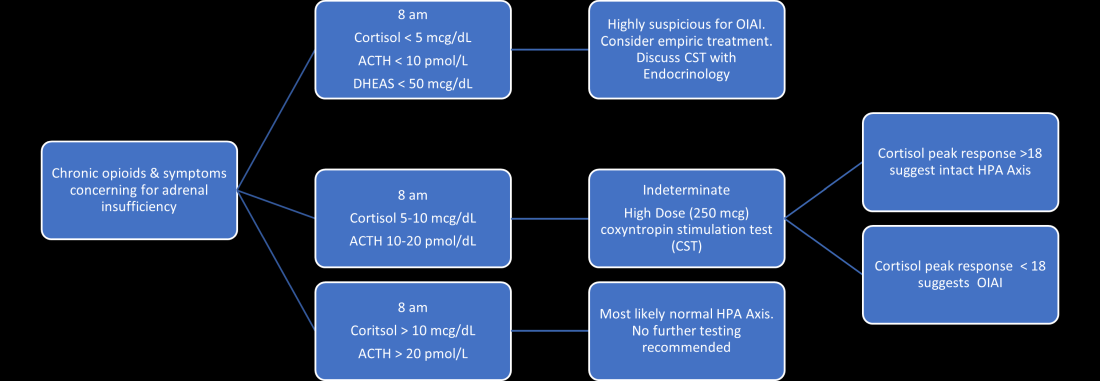

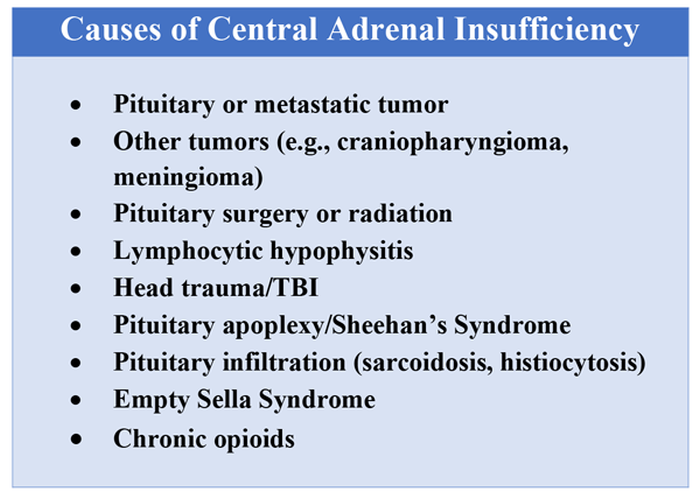

Unexplained or unresolved fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, and orthostatic hypotension in a patient on chronic opioids should prompt consideration of OIAI.9 Once suspected, an 8 a.m. cortisol, ACTH level, and DHEAS level should be ordered. Because of the diurnal variation of cortisol levels, 8 a.m. values are best validated for diagnosis.10 While cutoffs differ, an 8 a.m. cortisol less than 5 mcg/dL combined with ACTH less than 10 pmol/L, and DHEAS less than 50 mcg/dL are highly suggestive of OIAI. Low or indeterminate baseline a.m. cortisol levels warrant confirmatory testing.4,10 While the insulin tolerance test is considered the gold standard, the high dose (250 mcg) cosyntropin stimulation test (CST) is the more commonly used test to diagnose and confirm AI. A CST peak response greater than 18-20 mcg/dL suggests an intact HPA axis (see Figure 1).10 This testing will diagnose central AI, but is not specific for OIAI. Other causes of central AI such as exogenous steroid use, pituitary pathology, and head trauma should be considered before attributing AI to opioids (see Table 1).4

The abnormal CST in central AI is from chronic ACTH deficiency and lack of adrenal stimulation resulting in adrenal atrophy. Adrenal atrophy leaves the adrenal glands incapable of responding to exogenous ACTH. This process takes several weeks; therefore, those with ACTH suppression caused by recent high-dose opioid use or subacute pituitary injury may have an indeterminate or normal cortisol response to high-dose exogenous ACTH.4 Even in the setting of a normal CST, there may remain uncertainty in the diagnosis of OIAI. When evaluating for central AI, the sensitivity and negative likelihood ratio of the CST are only 0.64 and 0.39, respectively.4 In the same cohort of 40 patients with OIAI, 11 patients had a normal CST.9 The low-dose (1 mcg) CST may increase the sensitivity, but the use of this test is limited because of technical challenges.1 Endocrinology consultation can assist when the initial diagnostic and clinical presentation is unclear.

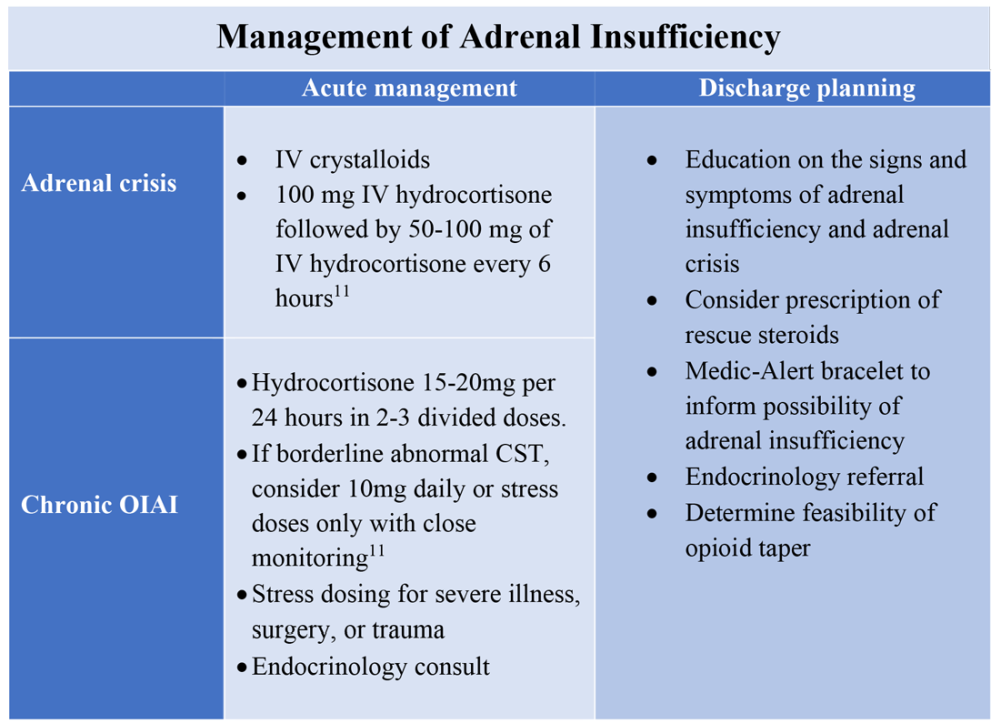

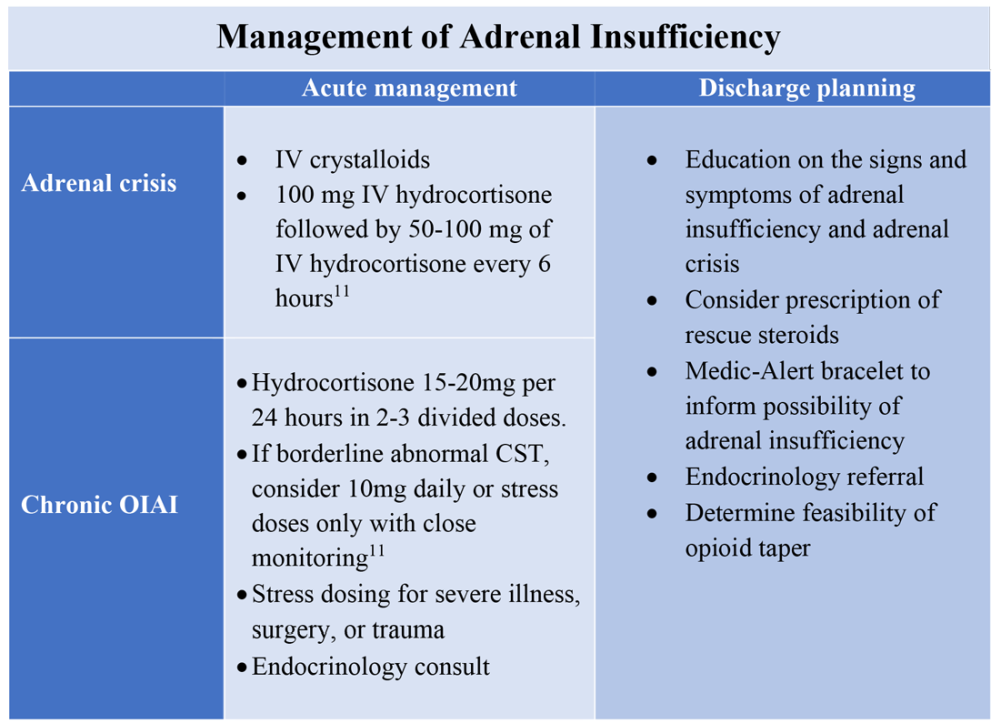

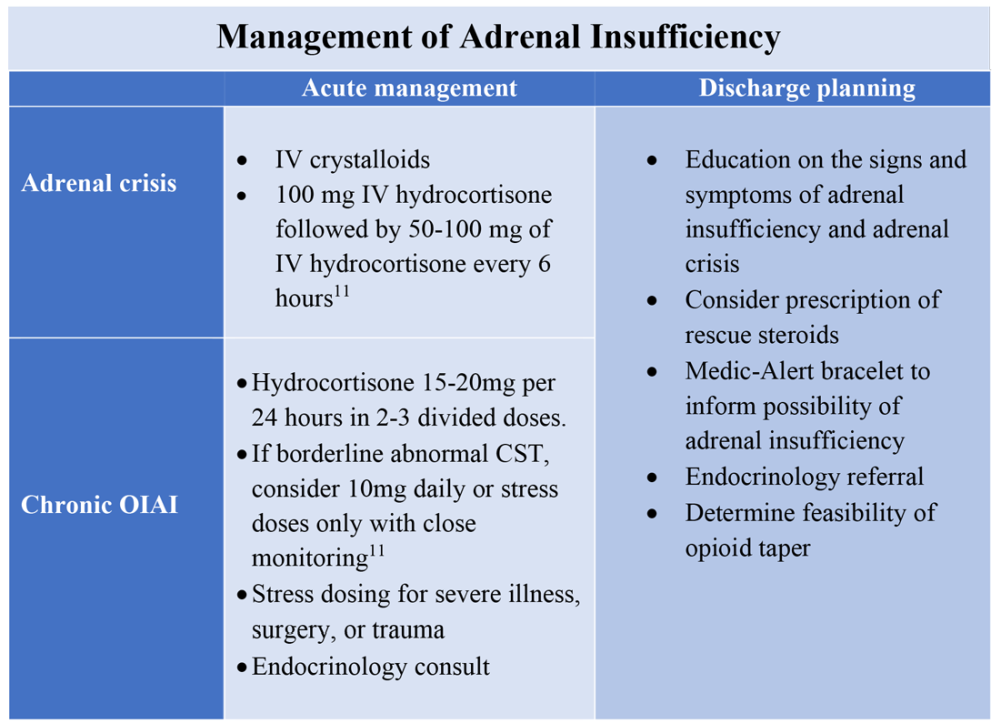

To manage a patient on opioid therapy who has laboratory data consistent with central AI, the clinician must weigh the severity of symptoms, probability of opioid weaning, and risks associated with glucocorticoid treatment. Patients presenting with acute adrenal crisis, hypotension, or critical illness should be managed with intravenous steroid replacement per existing guideline recommendations.10,11

Patients with mild symptoms of nausea, vomiting, or orthostatic symptoms that resolve with treatment of their admitting diagnosis but who have evidence of an abnormal HPA axis should be considered for weaning opioid therapy. Evidence suggests that OIAI is reversible with reduction and cessation of chronic opioid use.4,9 These patients may not need chronic steroid replacement; however, they should receive education on the symptoms of AI and potentially rescue steroids for home use in the setting of severe illness. Patients with OIAI admitted for surgical procedures should be managed in accordance with existing guidelines for perioperative stress dosing of glucocorticoids for AI.

Those with persisting symptoms of OIAI and an abnormal HPA axis require endocrinology consultation and glucocorticoid replacement. There is limited evidence that suggests low dose steroid replacement in patients with OIAI can improve subjective perception of bodily pain, activity level, and mood in chronic opioid users.9 Li and colleagues found that 16 of 23 patients experienced improvement of symptoms on glucocorticoids, and 15 were able to discontinue opioids completely.9 The authors speculated that the improvement in fatigue and musculoskeletal pain after steroid replacement is what allowed for successful opioid weaning. Seven of 10 of these patients with available follow-up had recovery of the HPA axis during the follow-up period.9 In central AI, doses as low as 10-20 mg/day of hydrocortisone have been used.10,11 Hospitalists should educate patients on recognizing symptoms of AI, as this low dose may not be sufficient to prevent adrenal crisis.

All patients with evidence of abnormalities in the HPA axis should receive a Medic-Alert bracelet to inform other providers of the possibility of adrenal crisis should a major trauma or critical illness render them unconscious.4,10 Since OIAI is a form of central AI, mineralocorticoid replacement is not generally necessary.11 Endocrinology follow-up can help wean steroids as the HPA axis recovers after weaning opioid therapy. Recognizing and diagnosing OIAI can identify patients with untreated symptoms who are at risk for adrenal crisis, improve communication with patients on benefits of weaning opioids, and provide valuable patient education and safe transition of care.

Application of the data to the original case

To make the diagnosis of OIAI, 8 a.m. cortisol, ACTH, and DHEAS should be obtained. Her cortisol was less than 5 mcg/dL, ACTH was 6 pmol/L and DHEAS was 30 mcg/dL. A high dose CST was performed with 30-minute and 60-minute cortisol values of 6 mcg/dL and 9 mcg/dL, respectively. The abnormal CST and low ACTH indicate central AI. She should undergo testing for other etiologies of central AI, such as a brain MRI and pituitary hormone testing, before confirming the diagnosis of OIAI.

The insufficient adrenal response to ACTH in the setting of infection and hypotension should prompt glucocorticoid replacement. Tapering opioids could result in recovery of the HPA axis, though may not be realistic in this patient with chronic cancer-related pain. If the patient is at high risk for adverse effects of glucocorticoids, repeat testing of the HPA axis in the outpatient setting can assess if the patient truly needs steroid replacement daily rather than only during physiologic stress. The patient should be given a Medic-Alert bracelet and instructions on symptoms of AI and stress dosing upon discharge.

Bottom line

OIAI is underrecognized because of central adrenal insufficiency. Knowing its clinical characteristics, diagnostic pathways, and treatment options aids in recognition and management.

Dr. Cunningham, Dr. Munoa, and Dr. Indovina are based in the division of hospital medicine at Denver Health and Hospital Authority.

References

1. Donegan D. Opioid induced adrenal insufficiency: What is new? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Jun;26(3):133-8. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000474.

2. Liang Y and Turner BJ. Opioid risk measure for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2015 July;10(7):425-31. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2350.

3. Policola C et al. Adrenal insufficiency in acute oral opiate therapy. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2014;2014:130071. doi: 10.1530/EDM-13-0071.

4. Donegan D and Bancos I. Opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 July;93(7):937-44. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.010.

5. Lamprecht A et al. Secondary adrenal insufficiency and pituitary dysfunction in oral/transdermal opioid users with non-cancer pain. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018 Dec 1;179(6):353-62. doi: 10.1530/EJE-18-0530.

6. Gibb FW et al. Adrenal insufficiency in patients on long-term opioid analgesia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016 June;85(6):831-5. doi:10.1111/cen.13125.

7. Abs R et al. Endocrine consequences of long-term intrathecal administration of opioids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000 June;85(6):2215-22. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.6.6615.

8. Tabet EJ et al. Opioid-induced hypoadrenalism resulting in fasting hypoglycaemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Dec 11;12(12):e230551. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-230551.

9. Li T et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of opioid induced adrenal insufficiency. Endocr Pract. 2020 Nov;26(11):1291-1297. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0297.

10. Grossman AB. Clinical Review: The diagnosis and management of central hypoadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Nov;95(11):4855-63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0982.

11. Charmandari E et al. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2014 June 21;383(9935):2152-67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61684-0.

Key points

- Opioids can cause central adrenal insufficiency because of tonic suppression of the HPA axis. This effect is likely dose dependent, and reversible upon tapering or withdrawal of opioids.

- The prevalence of biochemical OIAI in chronic opioid users of 8%-29% clinical AI is less frequent but may be underrecognized in hospitalized patients leading to delayed diagnosis.

- Diagnosis of central adrenal insufficiency is based upon low 8 a.m. cortisol and ACTH levels and/or an abnormal CST. OIAI is the likely etiology in patients on chronic opioids for whom other causes of central adrenal insufficiency have been ruled out.

- Management with glucocorticoid replacement is variable depending on clinical presentation, severity of HPA axis suppression, and ability to wean opioid therapy. Patient education regarding symptoms of AI and stress dosing is essential.

Additional reading

Grossman AB. Clinical Review: The diagnosis and management of central hypoadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Nov;95(11):4855-63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0982.

Donegan D and Bancos I. Opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 July;93(7):937-44. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.010.

Li T et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of opioid induced adrenal insufficiency. Endocr Pract. 2020 Nov;26(11):1291-7. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0297.

Quiz

A 55-year-old man with chronic back pain, for which he takes a total of 90 mg of oral morphine daily, is admitted for pyelonephritis with fever, nausea, vomiting, dysuria, and abdominal pain. He is febrile and tachycardic on presentation, but his vitals quickly normalize after hydration and antibiotics. About 48 hours into his hospitalization his fevers, dysuria, and abdominal pain have resolved, but he has persistent nausea and headaches. On further questioning, he also reports weight loss and fatigue over the past 3 weeks. He is found to have a morning cortisol level less than 5 mcg/dL, as well as low levels of ACTH and DHEAS. OIAI is suspected.

Which of the following is true about management?

A. Glucocorticoid replacement therapy with oral hydrocortisone should be considered to improve his symptoms.

B. Tapering off opioids is unlikely to resolve his adrenal insufficiency.

C. Stress dose steroids should be started immediately with high-dose intravenous hydrocortisone.

D. Given high clinical suspicion for OIAI, further testing for other etiologies of central adrenal insufficiency is not recommended.

Explanation of correct answer

The correct answer is A. This patient’s ongoing nonspecific symptoms that have persisted despite treatment of his acute pyelonephritis are likely caused by adrenal insufficiency. In a symptomatic patient with OIAI, treatment with oral hydrocortisone should be considered to control symptoms and facilitate tapering opioids. Tapering and stopping opioids often leads to recovery of the HPA axis and resolution of the OIAI. Tapering opioids should be considered a mainstay of therapy for OIAI when clinically appropriate, as in this patient with chronic benign pain. Stress dose steroids are not indicated in the absence of critical illness, adrenal crisis, or major surgery. OIAI is a diagnosis of exclusion, and patients should undergo workup for other causes of secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Consider OIAI, even among patients with common infections

Consider OIAI, even among patients with common infections

Case

A 60-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer using morphine extended release 30 mg twice daily and as-needed oxycodone for cancer-related pain presents with fever, dyspnea, and productive cough for 2 days. She also notes several weeks of fatigue, nausea, weight loss, and orthostatic lightheadedness. She is found to have pneumonia and is admitted for intravenous antibiotics. She remains borderline hypotensive after intravenous fluids and the hospitalist suspects opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency (OIAI).

How is OIAI diagnosed and managed?

Brief overview of issue

In the United States, 5.4% of the population is currently using long-term opioids.1 Patients using high doses of opioids for greater than 3 months are 40%-50% more likely to be hospitalized than those on a lower dose or no opioids.2 Hospitalists frequently encounter common opioid side effects such as constipation, nausea, and drowsiness, but may be less familiar with their effects on the endocrine system. Chronic, high-dose opioids can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and cause secondary, or central, adrenal insufficiency (AI).1

Recognition of OIAI is critical given the current opioid epidemic and life-threatening consequences of AI in systemically ill patients. While high-dose opioids may acutely suppress the HPA axis,3 OIAI is more commonly associated with long-term opioid use.4 The prevalence of OIAI among patients receiving long-term opioids ranges from 8.3% to 29%. This range reflects variations in opioid dose, duration of use, and different methods of assessing the HPA axis.1,4 When screening for HPA axis suppression in subjects taking chronic opioids, Lamprecht and colleagues found a prevalence of 22.5%.5 In comparison, Gibb and colleagues found the prevalence of secondary AI to be 8.3% in patients enrolled in a chronic pain clinic.6 Despite the high prevalence on biochemical screening, the clinical significance of OIAI is less clear. Clinical AI and adrenal crisis among patients on opioids are less frequent and mostly limited to case reports.7,8 In one retrospective cohort, one in 40 patients with OIAI presented with adrenal crisis during a hospitalization for viral gastroenteritis.9

With this prevalence, one would expect to diagnose OIAI more commonly in hospitalized patients. A concerning possibility is that this diagnosis is underrecognized because of either a lack of knowledge of the disease or the clinical overlap between the nonspecific symptoms of AI and other diagnoses. In patients reporting symptoms suggestive of OIAI, the diagnosis was delayed by a median of 12 months.9 The challenge for the hospitalist is to consider OIAI, even among patients with common infections such as pneumonia, viral gastroenteritis, or endocarditis who present with these nonspecific symptoms, while also avoiding unnecessary testing and treatment with glucocorticoids.

Overview of the data

Opiates and opioids exert their physiologic effect through activation of the mu, kappa, and delta receptors. These receptors are located throughout the body, including the hypothalamus and pituitary gland.4 Activation of these receptors results in tonic inhibition of the HPA axis and results in central AI.4 Central AI is characterized by a low a.m. cortisol, low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and low dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels.1,4 The low ACTH is indicative of central etiology. This effect of opioids is likely dose dependent with patients using more than 60 morphine-equivalent daily dose at greater risk.1,5

Unexplained or unresolved fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, and orthostatic hypotension in a patient on chronic opioids should prompt consideration of OIAI.9 Once suspected, an 8 a.m. cortisol, ACTH level, and DHEAS level should be ordered. Because of the diurnal variation of cortisol levels, 8 a.m. values are best validated for diagnosis.10 While cutoffs differ, an 8 a.m. cortisol less than 5 mcg/dL combined with ACTH less than 10 pmol/L, and DHEAS less than 50 mcg/dL are highly suggestive of OIAI. Low or indeterminate baseline a.m. cortisol levels warrant confirmatory testing.4,10 While the insulin tolerance test is considered the gold standard, the high dose (250 mcg) cosyntropin stimulation test (CST) is the more commonly used test to diagnose and confirm AI. A CST peak response greater than 18-20 mcg/dL suggests an intact HPA axis (see Figure 1).10 This testing will diagnose central AI, but is not specific for OIAI. Other causes of central AI such as exogenous steroid use, pituitary pathology, and head trauma should be considered before attributing AI to opioids (see Table 1).4

The abnormal CST in central AI is from chronic ACTH deficiency and lack of adrenal stimulation resulting in adrenal atrophy. Adrenal atrophy leaves the adrenal glands incapable of responding to exogenous ACTH. This process takes several weeks; therefore, those with ACTH suppression caused by recent high-dose opioid use or subacute pituitary injury may have an indeterminate or normal cortisol response to high-dose exogenous ACTH.4 Even in the setting of a normal CST, there may remain uncertainty in the diagnosis of OIAI. When evaluating for central AI, the sensitivity and negative likelihood ratio of the CST are only 0.64 and 0.39, respectively.4 In the same cohort of 40 patients with OIAI, 11 patients had a normal CST.9 The low-dose (1 mcg) CST may increase the sensitivity, but the use of this test is limited because of technical challenges.1 Endocrinology consultation can assist when the initial diagnostic and clinical presentation is unclear.

To manage a patient on opioid therapy who has laboratory data consistent with central AI, the clinician must weigh the severity of symptoms, probability of opioid weaning, and risks associated with glucocorticoid treatment. Patients presenting with acute adrenal crisis, hypotension, or critical illness should be managed with intravenous steroid replacement per existing guideline recommendations.10,11

Patients with mild symptoms of nausea, vomiting, or orthostatic symptoms that resolve with treatment of their admitting diagnosis but who have evidence of an abnormal HPA axis should be considered for weaning opioid therapy. Evidence suggests that OIAI is reversible with reduction and cessation of chronic opioid use.4,9 These patients may not need chronic steroid replacement; however, they should receive education on the symptoms of AI and potentially rescue steroids for home use in the setting of severe illness. Patients with OIAI admitted for surgical procedures should be managed in accordance with existing guidelines for perioperative stress dosing of glucocorticoids for AI.

Those with persisting symptoms of OIAI and an abnormal HPA axis require endocrinology consultation and glucocorticoid replacement. There is limited evidence that suggests low dose steroid replacement in patients with OIAI can improve subjective perception of bodily pain, activity level, and mood in chronic opioid users.9 Li and colleagues found that 16 of 23 patients experienced improvement of symptoms on glucocorticoids, and 15 were able to discontinue opioids completely.9 The authors speculated that the improvement in fatigue and musculoskeletal pain after steroid replacement is what allowed for successful opioid weaning. Seven of 10 of these patients with available follow-up had recovery of the HPA axis during the follow-up period.9 In central AI, doses as low as 10-20 mg/day of hydrocortisone have been used.10,11 Hospitalists should educate patients on recognizing symptoms of AI, as this low dose may not be sufficient to prevent adrenal crisis.

All patients with evidence of abnormalities in the HPA axis should receive a Medic-Alert bracelet to inform other providers of the possibility of adrenal crisis should a major trauma or critical illness render them unconscious.4,10 Since OIAI is a form of central AI, mineralocorticoid replacement is not generally necessary.11 Endocrinology follow-up can help wean steroids as the HPA axis recovers after weaning opioid therapy. Recognizing and diagnosing OIAI can identify patients with untreated symptoms who are at risk for adrenal crisis, improve communication with patients on benefits of weaning opioids, and provide valuable patient education and safe transition of care.

Application of the data to the original case

To make the diagnosis of OIAI, 8 a.m. cortisol, ACTH, and DHEAS should be obtained. Her cortisol was less than 5 mcg/dL, ACTH was 6 pmol/L and DHEAS was 30 mcg/dL. A high dose CST was performed with 30-minute and 60-minute cortisol values of 6 mcg/dL and 9 mcg/dL, respectively. The abnormal CST and low ACTH indicate central AI. She should undergo testing for other etiologies of central AI, such as a brain MRI and pituitary hormone testing, before confirming the diagnosis of OIAI.

The insufficient adrenal response to ACTH in the setting of infection and hypotension should prompt glucocorticoid replacement. Tapering opioids could result in recovery of the HPA axis, though may not be realistic in this patient with chronic cancer-related pain. If the patient is at high risk for adverse effects of glucocorticoids, repeat testing of the HPA axis in the outpatient setting can assess if the patient truly needs steroid replacement daily rather than only during physiologic stress. The patient should be given a Medic-Alert bracelet and instructions on symptoms of AI and stress dosing upon discharge.

Bottom line

OIAI is underrecognized because of central adrenal insufficiency. Knowing its clinical characteristics, diagnostic pathways, and treatment options aids in recognition and management.

Dr. Cunningham, Dr. Munoa, and Dr. Indovina are based in the division of hospital medicine at Denver Health and Hospital Authority.

References

1. Donegan D. Opioid induced adrenal insufficiency: What is new? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Jun;26(3):133-8. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000474.

2. Liang Y and Turner BJ. Opioid risk measure for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2015 July;10(7):425-31. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2350.

3. Policola C et al. Adrenal insufficiency in acute oral opiate therapy. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2014;2014:130071. doi: 10.1530/EDM-13-0071.

4. Donegan D and Bancos I. Opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 July;93(7):937-44. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.010.

5. Lamprecht A et al. Secondary adrenal insufficiency and pituitary dysfunction in oral/transdermal opioid users with non-cancer pain. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018 Dec 1;179(6):353-62. doi: 10.1530/EJE-18-0530.

6. Gibb FW et al. Adrenal insufficiency in patients on long-term opioid analgesia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016 June;85(6):831-5. doi:10.1111/cen.13125.

7. Abs R et al. Endocrine consequences of long-term intrathecal administration of opioids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000 June;85(6):2215-22. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.6.6615.

8. Tabet EJ et al. Opioid-induced hypoadrenalism resulting in fasting hypoglycaemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Dec 11;12(12):e230551. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-230551.

9. Li T et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of opioid induced adrenal insufficiency. Endocr Pract. 2020 Nov;26(11):1291-1297. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0297.

10. Grossman AB. Clinical Review: The diagnosis and management of central hypoadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Nov;95(11):4855-63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0982.

11. Charmandari E et al. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2014 June 21;383(9935):2152-67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61684-0.

Key points

- Opioids can cause central adrenal insufficiency because of tonic suppression of the HPA axis. This effect is likely dose dependent, and reversible upon tapering or withdrawal of opioids.

- The prevalence of biochemical OIAI in chronic opioid users of 8%-29% clinical AI is less frequent but may be underrecognized in hospitalized patients leading to delayed diagnosis.

- Diagnosis of central adrenal insufficiency is based upon low 8 a.m. cortisol and ACTH levels and/or an abnormal CST. OIAI is the likely etiology in patients on chronic opioids for whom other causes of central adrenal insufficiency have been ruled out.

- Management with glucocorticoid replacement is variable depending on clinical presentation, severity of HPA axis suppression, and ability to wean opioid therapy. Patient education regarding symptoms of AI and stress dosing is essential.

Additional reading

Grossman AB. Clinical Review: The diagnosis and management of central hypoadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Nov;95(11):4855-63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0982.

Donegan D and Bancos I. Opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 July;93(7):937-44. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.010.

Li T et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of opioid induced adrenal insufficiency. Endocr Pract. 2020 Nov;26(11):1291-7. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0297.

Quiz

A 55-year-old man with chronic back pain, for which he takes a total of 90 mg of oral morphine daily, is admitted for pyelonephritis with fever, nausea, vomiting, dysuria, and abdominal pain. He is febrile and tachycardic on presentation, but his vitals quickly normalize after hydration and antibiotics. About 48 hours into his hospitalization his fevers, dysuria, and abdominal pain have resolved, but he has persistent nausea and headaches. On further questioning, he also reports weight loss and fatigue over the past 3 weeks. He is found to have a morning cortisol level less than 5 mcg/dL, as well as low levels of ACTH and DHEAS. OIAI is suspected.

Which of the following is true about management?

A. Glucocorticoid replacement therapy with oral hydrocortisone should be considered to improve his symptoms.

B. Tapering off opioids is unlikely to resolve his adrenal insufficiency.

C. Stress dose steroids should be started immediately with high-dose intravenous hydrocortisone.

D. Given high clinical suspicion for OIAI, further testing for other etiologies of central adrenal insufficiency is not recommended.

Explanation of correct answer

The correct answer is A. This patient’s ongoing nonspecific symptoms that have persisted despite treatment of his acute pyelonephritis are likely caused by adrenal insufficiency. In a symptomatic patient with OIAI, treatment with oral hydrocortisone should be considered to control symptoms and facilitate tapering opioids. Tapering and stopping opioids often leads to recovery of the HPA axis and resolution of the OIAI. Tapering opioids should be considered a mainstay of therapy for OIAI when clinically appropriate, as in this patient with chronic benign pain. Stress dose steroids are not indicated in the absence of critical illness, adrenal crisis, or major surgery. OIAI is a diagnosis of exclusion, and patients should undergo workup for other causes of secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Case

A 60-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer using morphine extended release 30 mg twice daily and as-needed oxycodone for cancer-related pain presents with fever, dyspnea, and productive cough for 2 days. She also notes several weeks of fatigue, nausea, weight loss, and orthostatic lightheadedness. She is found to have pneumonia and is admitted for intravenous antibiotics. She remains borderline hypotensive after intravenous fluids and the hospitalist suspects opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency (OIAI).

How is OIAI diagnosed and managed?

Brief overview of issue

In the United States, 5.4% of the population is currently using long-term opioids.1 Patients using high doses of opioids for greater than 3 months are 40%-50% more likely to be hospitalized than those on a lower dose or no opioids.2 Hospitalists frequently encounter common opioid side effects such as constipation, nausea, and drowsiness, but may be less familiar with their effects on the endocrine system. Chronic, high-dose opioids can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and cause secondary, or central, adrenal insufficiency (AI).1

Recognition of OIAI is critical given the current opioid epidemic and life-threatening consequences of AI in systemically ill patients. While high-dose opioids may acutely suppress the HPA axis,3 OIAI is more commonly associated with long-term opioid use.4 The prevalence of OIAI among patients receiving long-term opioids ranges from 8.3% to 29%. This range reflects variations in opioid dose, duration of use, and different methods of assessing the HPA axis.1,4 When screening for HPA axis suppression in subjects taking chronic opioids, Lamprecht and colleagues found a prevalence of 22.5%.5 In comparison, Gibb and colleagues found the prevalence of secondary AI to be 8.3% in patients enrolled in a chronic pain clinic.6 Despite the high prevalence on biochemical screening, the clinical significance of OIAI is less clear. Clinical AI and adrenal crisis among patients on opioids are less frequent and mostly limited to case reports.7,8 In one retrospective cohort, one in 40 patients with OIAI presented with adrenal crisis during a hospitalization for viral gastroenteritis.9

With this prevalence, one would expect to diagnose OIAI more commonly in hospitalized patients. A concerning possibility is that this diagnosis is underrecognized because of either a lack of knowledge of the disease or the clinical overlap between the nonspecific symptoms of AI and other diagnoses. In patients reporting symptoms suggestive of OIAI, the diagnosis was delayed by a median of 12 months.9 The challenge for the hospitalist is to consider OIAI, even among patients with common infections such as pneumonia, viral gastroenteritis, or endocarditis who present with these nonspecific symptoms, while also avoiding unnecessary testing and treatment with glucocorticoids.

Overview of the data

Opiates and opioids exert their physiologic effect through activation of the mu, kappa, and delta receptors. These receptors are located throughout the body, including the hypothalamus and pituitary gland.4 Activation of these receptors results in tonic inhibition of the HPA axis and results in central AI.4 Central AI is characterized by a low a.m. cortisol, low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and low dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels.1,4 The low ACTH is indicative of central etiology. This effect of opioids is likely dose dependent with patients using more than 60 morphine-equivalent daily dose at greater risk.1,5

Unexplained or unresolved fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, and orthostatic hypotension in a patient on chronic opioids should prompt consideration of OIAI.9 Once suspected, an 8 a.m. cortisol, ACTH level, and DHEAS level should be ordered. Because of the diurnal variation of cortisol levels, 8 a.m. values are best validated for diagnosis.10 While cutoffs differ, an 8 a.m. cortisol less than 5 mcg/dL combined with ACTH less than 10 pmol/L, and DHEAS less than 50 mcg/dL are highly suggestive of OIAI. Low or indeterminate baseline a.m. cortisol levels warrant confirmatory testing.4,10 While the insulin tolerance test is considered the gold standard, the high dose (250 mcg) cosyntropin stimulation test (CST) is the more commonly used test to diagnose and confirm AI. A CST peak response greater than 18-20 mcg/dL suggests an intact HPA axis (see Figure 1).10 This testing will diagnose central AI, but is not specific for OIAI. Other causes of central AI such as exogenous steroid use, pituitary pathology, and head trauma should be considered before attributing AI to opioids (see Table 1).4

The abnormal CST in central AI is from chronic ACTH deficiency and lack of adrenal stimulation resulting in adrenal atrophy. Adrenal atrophy leaves the adrenal glands incapable of responding to exogenous ACTH. This process takes several weeks; therefore, those with ACTH suppression caused by recent high-dose opioid use or subacute pituitary injury may have an indeterminate or normal cortisol response to high-dose exogenous ACTH.4 Even in the setting of a normal CST, there may remain uncertainty in the diagnosis of OIAI. When evaluating for central AI, the sensitivity and negative likelihood ratio of the CST are only 0.64 and 0.39, respectively.4 In the same cohort of 40 patients with OIAI, 11 patients had a normal CST.9 The low-dose (1 mcg) CST may increase the sensitivity, but the use of this test is limited because of technical challenges.1 Endocrinology consultation can assist when the initial diagnostic and clinical presentation is unclear.

To manage a patient on opioid therapy who has laboratory data consistent with central AI, the clinician must weigh the severity of symptoms, probability of opioid weaning, and risks associated with glucocorticoid treatment. Patients presenting with acute adrenal crisis, hypotension, or critical illness should be managed with intravenous steroid replacement per existing guideline recommendations.10,11

Patients with mild symptoms of nausea, vomiting, or orthostatic symptoms that resolve with treatment of their admitting diagnosis but who have evidence of an abnormal HPA axis should be considered for weaning opioid therapy. Evidence suggests that OIAI is reversible with reduction and cessation of chronic opioid use.4,9 These patients may not need chronic steroid replacement; however, they should receive education on the symptoms of AI and potentially rescue steroids for home use in the setting of severe illness. Patients with OIAI admitted for surgical procedures should be managed in accordance with existing guidelines for perioperative stress dosing of glucocorticoids for AI.

Those with persisting symptoms of OIAI and an abnormal HPA axis require endocrinology consultation and glucocorticoid replacement. There is limited evidence that suggests low dose steroid replacement in patients with OIAI can improve subjective perception of bodily pain, activity level, and mood in chronic opioid users.9 Li and colleagues found that 16 of 23 patients experienced improvement of symptoms on glucocorticoids, and 15 were able to discontinue opioids completely.9 The authors speculated that the improvement in fatigue and musculoskeletal pain after steroid replacement is what allowed for successful opioid weaning. Seven of 10 of these patients with available follow-up had recovery of the HPA axis during the follow-up period.9 In central AI, doses as low as 10-20 mg/day of hydrocortisone have been used.10,11 Hospitalists should educate patients on recognizing symptoms of AI, as this low dose may not be sufficient to prevent adrenal crisis.

All patients with evidence of abnormalities in the HPA axis should receive a Medic-Alert bracelet to inform other providers of the possibility of adrenal crisis should a major trauma or critical illness render them unconscious.4,10 Since OIAI is a form of central AI, mineralocorticoid replacement is not generally necessary.11 Endocrinology follow-up can help wean steroids as the HPA axis recovers after weaning opioid therapy. Recognizing and diagnosing OIAI can identify patients with untreated symptoms who are at risk for adrenal crisis, improve communication with patients on benefits of weaning opioids, and provide valuable patient education and safe transition of care.

Application of the data to the original case

To make the diagnosis of OIAI, 8 a.m. cortisol, ACTH, and DHEAS should be obtained. Her cortisol was less than 5 mcg/dL, ACTH was 6 pmol/L and DHEAS was 30 mcg/dL. A high dose CST was performed with 30-minute and 60-minute cortisol values of 6 mcg/dL and 9 mcg/dL, respectively. The abnormal CST and low ACTH indicate central AI. She should undergo testing for other etiologies of central AI, such as a brain MRI and pituitary hormone testing, before confirming the diagnosis of OIAI.

The insufficient adrenal response to ACTH in the setting of infection and hypotension should prompt glucocorticoid replacement. Tapering opioids could result in recovery of the HPA axis, though may not be realistic in this patient with chronic cancer-related pain. If the patient is at high risk for adverse effects of glucocorticoids, repeat testing of the HPA axis in the outpatient setting can assess if the patient truly needs steroid replacement daily rather than only during physiologic stress. The patient should be given a Medic-Alert bracelet and instructions on symptoms of AI and stress dosing upon discharge.

Bottom line

OIAI is underrecognized because of central adrenal insufficiency. Knowing its clinical characteristics, diagnostic pathways, and treatment options aids in recognition and management.

Dr. Cunningham, Dr. Munoa, and Dr. Indovina are based in the division of hospital medicine at Denver Health and Hospital Authority.

References

1. Donegan D. Opioid induced adrenal insufficiency: What is new? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Jun;26(3):133-8. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000474.

2. Liang Y and Turner BJ. Opioid risk measure for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2015 July;10(7):425-31. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2350.

3. Policola C et al. Adrenal insufficiency in acute oral opiate therapy. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2014;2014:130071. doi: 10.1530/EDM-13-0071.

4. Donegan D and Bancos I. Opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 July;93(7):937-44. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.010.

5. Lamprecht A et al. Secondary adrenal insufficiency and pituitary dysfunction in oral/transdermal opioid users with non-cancer pain. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018 Dec 1;179(6):353-62. doi: 10.1530/EJE-18-0530.

6. Gibb FW et al. Adrenal insufficiency in patients on long-term opioid analgesia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016 June;85(6):831-5. doi:10.1111/cen.13125.

7. Abs R et al. Endocrine consequences of long-term intrathecal administration of opioids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000 June;85(6):2215-22. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.6.6615.

8. Tabet EJ et al. Opioid-induced hypoadrenalism resulting in fasting hypoglycaemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Dec 11;12(12):e230551. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-230551.

9. Li T et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of opioid induced adrenal insufficiency. Endocr Pract. 2020 Nov;26(11):1291-1297. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0297.

10. Grossman AB. Clinical Review: The diagnosis and management of central hypoadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Nov;95(11):4855-63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0982.

11. Charmandari E et al. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2014 June 21;383(9935):2152-67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61684-0.

Key points

- Opioids can cause central adrenal insufficiency because of tonic suppression of the HPA axis. This effect is likely dose dependent, and reversible upon tapering or withdrawal of opioids.

- The prevalence of biochemical OIAI in chronic opioid users of 8%-29% clinical AI is less frequent but may be underrecognized in hospitalized patients leading to delayed diagnosis.

- Diagnosis of central adrenal insufficiency is based upon low 8 a.m. cortisol and ACTH levels and/or an abnormal CST. OIAI is the likely etiology in patients on chronic opioids for whom other causes of central adrenal insufficiency have been ruled out.

- Management with glucocorticoid replacement is variable depending on clinical presentation, severity of HPA axis suppression, and ability to wean opioid therapy. Patient education regarding symptoms of AI and stress dosing is essential.

Additional reading

Grossman AB. Clinical Review: The diagnosis and management of central hypoadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Nov;95(11):4855-63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0982.

Donegan D and Bancos I. Opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 July;93(7):937-44. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.010.

Li T et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of opioid induced adrenal insufficiency. Endocr Pract. 2020 Nov;26(11):1291-7. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0297.

Quiz

A 55-year-old man with chronic back pain, for which he takes a total of 90 mg of oral morphine daily, is admitted for pyelonephritis with fever, nausea, vomiting, dysuria, and abdominal pain. He is febrile and tachycardic on presentation, but his vitals quickly normalize after hydration and antibiotics. About 48 hours into his hospitalization his fevers, dysuria, and abdominal pain have resolved, but he has persistent nausea and headaches. On further questioning, he also reports weight loss and fatigue over the past 3 weeks. He is found to have a morning cortisol level less than 5 mcg/dL, as well as low levels of ACTH and DHEAS. OIAI is suspected.

Which of the following is true about management?

A. Glucocorticoid replacement therapy with oral hydrocortisone should be considered to improve his symptoms.

B. Tapering off opioids is unlikely to resolve his adrenal insufficiency.

C. Stress dose steroids should be started immediately with high-dose intravenous hydrocortisone.

D. Given high clinical suspicion for OIAI, further testing for other etiologies of central adrenal insufficiency is not recommended.

Explanation of correct answer

The correct answer is A. This patient’s ongoing nonspecific symptoms that have persisted despite treatment of his acute pyelonephritis are likely caused by adrenal insufficiency. In a symptomatic patient with OIAI, treatment with oral hydrocortisone should be considered to control symptoms and facilitate tapering opioids. Tapering and stopping opioids often leads to recovery of the HPA axis and resolution of the OIAI. Tapering opioids should be considered a mainstay of therapy for OIAI when clinically appropriate, as in this patient with chronic benign pain. Stress dose steroids are not indicated in the absence of critical illness, adrenal crisis, or major surgery. OIAI is a diagnosis of exclusion, and patients should undergo workup for other causes of secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Unvaccinated people likely to catch COVID repeatedly

according to a recent study published in The Lancet Microbe.

Since COVID-19 hasn’t existed for long enough to perform a long-term study, researchers at Yale University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte looked at reinfection data for six other human-infecting coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS.

“Reinfection can reasonably happen in three months or less,” Jeffrey Townsend, PhD, lead study author and a biostatistics professor at the Yale School of Public Health, said in a statement.

“Therefore, those who have been naturally infected should get vaccinated,” he said. “Previous infection alone can offer very little long-term protection against subsequent infections.”

The research team looked at post-infection data for six coronaviruses between 1984-2020 and found reinfection ranged from 128 days to 28 years. They calculated that reinfection with COVID-19 would likely occur between 3 months to 5 years after peak antibody response, with an average of 16 months. This is less than half the duration seen for other coronaviruses that circulate among humans.

The risk of COVID-19 reinfection is about 5% at three months, which jumps to 50% after 17 months, the research team found. Reinfection could become increasingly common as immunity wanes and new variants develop, they said.

“We tend to think about immunity as being immune or not immune. Our study cautions that we instead should be more focused on the risk of reinfection through time,” Alex Dornburg, PhD, senior study author and assistant professor of bioinformatics and genomics at UNC, said in the statement.

“As new variants arise, previous immune responses become less effective at combating the virus,” he said. “Those who were naturally infected early in the pandemic are increasingly likely to become reinfected in the near future.”

Study estimates are based on average times of declining immunity across different coronaviruses, the researchers told the Yale Daily News. At the individual level, people have different levels of immunity, which can provide shorter or longer duration of protection based on immune status, immunity within a community, age, underlying health conditions, environmental exposure, and other factors.

The research team said that preventive health measures and global distribution of vaccines will be “critical” in minimizing reinfection and COVID-19 deaths. In areas with low vaccination rates, for instance, unvaccinated people should continue safety practices such as social distancing, wearing masks, and proper indoor ventilation to avoid reinfection.

“We need to be very aware of the fact that this disease is likely to be circulating over the long term and that we don’t have this long-term immunity that many people seem to be hoping to rely on in order to protect them from disease,” Dr. Townsend told the newspaper.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a recent study published in The Lancet Microbe.

Since COVID-19 hasn’t existed for long enough to perform a long-term study, researchers at Yale University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte looked at reinfection data for six other human-infecting coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS.

“Reinfection can reasonably happen in three months or less,” Jeffrey Townsend, PhD, lead study author and a biostatistics professor at the Yale School of Public Health, said in a statement.

“Therefore, those who have been naturally infected should get vaccinated,” he said. “Previous infection alone can offer very little long-term protection against subsequent infections.”

The research team looked at post-infection data for six coronaviruses between 1984-2020 and found reinfection ranged from 128 days to 28 years. They calculated that reinfection with COVID-19 would likely occur between 3 months to 5 years after peak antibody response, with an average of 16 months. This is less than half the duration seen for other coronaviruses that circulate among humans.

The risk of COVID-19 reinfection is about 5% at three months, which jumps to 50% after 17 months, the research team found. Reinfection could become increasingly common as immunity wanes and new variants develop, they said.

“We tend to think about immunity as being immune or not immune. Our study cautions that we instead should be more focused on the risk of reinfection through time,” Alex Dornburg, PhD, senior study author and assistant professor of bioinformatics and genomics at UNC, said in the statement.

“As new variants arise, previous immune responses become less effective at combating the virus,” he said. “Those who were naturally infected early in the pandemic are increasingly likely to become reinfected in the near future.”

Study estimates are based on average times of declining immunity across different coronaviruses, the researchers told the Yale Daily News. At the individual level, people have different levels of immunity, which can provide shorter or longer duration of protection based on immune status, immunity within a community, age, underlying health conditions, environmental exposure, and other factors.

The research team said that preventive health measures and global distribution of vaccines will be “critical” in minimizing reinfection and COVID-19 deaths. In areas with low vaccination rates, for instance, unvaccinated people should continue safety practices such as social distancing, wearing masks, and proper indoor ventilation to avoid reinfection.

“We need to be very aware of the fact that this disease is likely to be circulating over the long term and that we don’t have this long-term immunity that many people seem to be hoping to rely on in order to protect them from disease,” Dr. Townsend told the newspaper.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a recent study published in The Lancet Microbe.

Since COVID-19 hasn’t existed for long enough to perform a long-term study, researchers at Yale University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte looked at reinfection data for six other human-infecting coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS.

“Reinfection can reasonably happen in three months or less,” Jeffrey Townsend, PhD, lead study author and a biostatistics professor at the Yale School of Public Health, said in a statement.

“Therefore, those who have been naturally infected should get vaccinated,” he said. “Previous infection alone can offer very little long-term protection against subsequent infections.”

The research team looked at post-infection data for six coronaviruses between 1984-2020 and found reinfection ranged from 128 days to 28 years. They calculated that reinfection with COVID-19 would likely occur between 3 months to 5 years after peak antibody response, with an average of 16 months. This is less than half the duration seen for other coronaviruses that circulate among humans.

The risk of COVID-19 reinfection is about 5% at three months, which jumps to 50% after 17 months, the research team found. Reinfection could become increasingly common as immunity wanes and new variants develop, they said.

“We tend to think about immunity as being immune or not immune. Our study cautions that we instead should be more focused on the risk of reinfection through time,” Alex Dornburg, PhD, senior study author and assistant professor of bioinformatics and genomics at UNC, said in the statement.

“As new variants arise, previous immune responses become less effective at combating the virus,” he said. “Those who were naturally infected early in the pandemic are increasingly likely to become reinfected in the near future.”

Study estimates are based on average times of declining immunity across different coronaviruses, the researchers told the Yale Daily News. At the individual level, people have different levels of immunity, which can provide shorter or longer duration of protection based on immune status, immunity within a community, age, underlying health conditions, environmental exposure, and other factors.

The research team said that preventive health measures and global distribution of vaccines will be “critical” in minimizing reinfection and COVID-19 deaths. In areas with low vaccination rates, for instance, unvaccinated people should continue safety practices such as social distancing, wearing masks, and proper indoor ventilation to avoid reinfection.

“We need to be very aware of the fact that this disease is likely to be circulating over the long term and that we don’t have this long-term immunity that many people seem to be hoping to rely on in order to protect them from disease,” Dr. Townsend told the newspaper.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Fluoroquinolones linked to sudden death risk for those on hemodialysis

, a large observational study suggests.

However, in many cases, the absolute risk is relatively small, and the antimicrobial benefits of a fluoroquinolone may outweigh the potential cardiac risks, the researchers say.

“Pathogen-directed treatment of respiratory infections is of the utmost importance. Respiratory fluoroquinolones should be prescribed whenever an amoxicillin-based antibiotic offers suboptimal antimicrobial coverage and clinicians should consider electrocardiographic monitoring,” first author Magdalene M. Assimon, PharmD, PhD, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, told this news organization.

The study was published online Oct. 20 in JAMA Cardiology (doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.4234).

Nearly twofold increased risk

The QT interval-prolonging potential of fluoroquinolone antibiotics are well known. However, evidence linking respiratory fluoroquinolones to adverse cardiac outcomes in the hemodialysis population is limited.

These new observational findings are based on a total of 626,322 antibiotic treatment episodes among 264,968 adults (mean age, 61 years; 51% men) receiving in-center hemodialysis – with respiratory fluoroquinolone making up 40.2% of treatment episodes and amoxicillin-based antibiotic treatment episodes making up 59.8%.

The rate of SCD within 5 days of outpatient initiation of a study antibiotic was 105.7 per 100,000 people prescribed a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) versus with 40.0 per 100,000 prescribed amoxicillin or amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (weighted hazard ratio: 1.95; 95% confidence interval, 1.57-2.41).

The authors estimate that one additional SCD would occur during a 5-day follow-up period for every 2,273 respiratory fluoroquinolone treatment episodes. Consistent associations were seen when follow-up was extended to 7, 10, and 14 days.

“Our data suggest that curtailing respiratory fluoroquinolone prescribing may be one actionable strategy to mitigate SCD risk in the hemodialysis population. However, the associated absolute risk reduction would be relatively small,” wrote the authors.

They noted that the rate of SCD in the hemodialysis population exceeds that of the general population by more than 20-fold. Most patients undergoing hemodialysis have a least one risk factor for drug-induced QT interval prolongation.

In the current study, nearly 20% of hemodialysis patients prescribed a respiratory fluoroquinolone were taking other medications with known risk for torsades de pointes.

“Our results emphasize the importance of performing a thorough medication review and considering pharmacodynamic drug interactions before prescribing new drug therapies for any condition,” Dr. Assimon and colleagues advised.

They suggest that clinicians consider electrocardiographic monitoring before and during fluoroquinolone therapy in hemodialysis patients, especially in high-risk individuals.

Valuable study

Reached for comment, Ankur Shah, MD, of the division of kidney diseases and hypertension, Brown University, Providence, R.I., called the analysis “valuable” and said the results are “consistent with the known association of cardiac arrhythmias with respiratory fluoroquinolone use in the general population, postulated to be due to increased risk of torsades de pointes from QTc prolongation. This abnormal heart rhythm can lead to sudden cardiac death.

“Notably, the population receiving respiratory fluoroquinolones had a higher incidence of cardiac disease at baseline, but the risk persisted after adjustment for this increased burden of comorbidity,” Dr. Shah said in an interview. He was not involved in the current research.

Dr. Shah cautioned that observational data such as these should be considered more “hypothesis-generating than practice-changing, as there may be unrecognized confounders or differences in the population that received the respiratory fluoroquinolones.

“A prospective randomized trial would provide a definitive answer, but in the interim, caution should be taken in using respiratory fluoroquinolones when local bacterial resistance patterns or patient-specific data offer another option,” Dr. Shah concluded.

Dr. Assimon reported receiving grants from the Renal Research Institute (a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care), honoraria from the International Society of Nephrology for serving as a statistical reviewer for Kidney International Reports, and honoraria from the American Society of Nephrology for serving as an editorial fellow for the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a large observational study suggests.

However, in many cases, the absolute risk is relatively small, and the antimicrobial benefits of a fluoroquinolone may outweigh the potential cardiac risks, the researchers say.

“Pathogen-directed treatment of respiratory infections is of the utmost importance. Respiratory fluoroquinolones should be prescribed whenever an amoxicillin-based antibiotic offers suboptimal antimicrobial coverage and clinicians should consider electrocardiographic monitoring,” first author Magdalene M. Assimon, PharmD, PhD, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, told this news organization.

The study was published online Oct. 20 in JAMA Cardiology (doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.4234).

Nearly twofold increased risk

The QT interval-prolonging potential of fluoroquinolone antibiotics are well known. However, evidence linking respiratory fluoroquinolones to adverse cardiac outcomes in the hemodialysis population is limited.

These new observational findings are based on a total of 626,322 antibiotic treatment episodes among 264,968 adults (mean age, 61 years; 51% men) receiving in-center hemodialysis – with respiratory fluoroquinolone making up 40.2% of treatment episodes and amoxicillin-based antibiotic treatment episodes making up 59.8%.

The rate of SCD within 5 days of outpatient initiation of a study antibiotic was 105.7 per 100,000 people prescribed a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) versus with 40.0 per 100,000 prescribed amoxicillin or amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (weighted hazard ratio: 1.95; 95% confidence interval, 1.57-2.41).

The authors estimate that one additional SCD would occur during a 5-day follow-up period for every 2,273 respiratory fluoroquinolone treatment episodes. Consistent associations were seen when follow-up was extended to 7, 10, and 14 days.

“Our data suggest that curtailing respiratory fluoroquinolone prescribing may be one actionable strategy to mitigate SCD risk in the hemodialysis population. However, the associated absolute risk reduction would be relatively small,” wrote the authors.

They noted that the rate of SCD in the hemodialysis population exceeds that of the general population by more than 20-fold. Most patients undergoing hemodialysis have a least one risk factor for drug-induced QT interval prolongation.

In the current study, nearly 20% of hemodialysis patients prescribed a respiratory fluoroquinolone were taking other medications with known risk for torsades de pointes.

“Our results emphasize the importance of performing a thorough medication review and considering pharmacodynamic drug interactions before prescribing new drug therapies for any condition,” Dr. Assimon and colleagues advised.

They suggest that clinicians consider electrocardiographic monitoring before and during fluoroquinolone therapy in hemodialysis patients, especially in high-risk individuals.

Valuable study

Reached for comment, Ankur Shah, MD, of the division of kidney diseases and hypertension, Brown University, Providence, R.I., called the analysis “valuable” and said the results are “consistent with the known association of cardiac arrhythmias with respiratory fluoroquinolone use in the general population, postulated to be due to increased risk of torsades de pointes from QTc prolongation. This abnormal heart rhythm can lead to sudden cardiac death.

“Notably, the population receiving respiratory fluoroquinolones had a higher incidence of cardiac disease at baseline, but the risk persisted after adjustment for this increased burden of comorbidity,” Dr. Shah said in an interview. He was not involved in the current research.

Dr. Shah cautioned that observational data such as these should be considered more “hypothesis-generating than practice-changing, as there may be unrecognized confounders or differences in the population that received the respiratory fluoroquinolones.

“A prospective randomized trial would provide a definitive answer, but in the interim, caution should be taken in using respiratory fluoroquinolones when local bacterial resistance patterns or patient-specific data offer another option,” Dr. Shah concluded.

Dr. Assimon reported receiving grants from the Renal Research Institute (a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care), honoraria from the International Society of Nephrology for serving as a statistical reviewer for Kidney International Reports, and honoraria from the American Society of Nephrology for serving as an editorial fellow for the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a large observational study suggests.

However, in many cases, the absolute risk is relatively small, and the antimicrobial benefits of a fluoroquinolone may outweigh the potential cardiac risks, the researchers say.

“Pathogen-directed treatment of respiratory infections is of the utmost importance. Respiratory fluoroquinolones should be prescribed whenever an amoxicillin-based antibiotic offers suboptimal antimicrobial coverage and clinicians should consider electrocardiographic monitoring,” first author Magdalene M. Assimon, PharmD, PhD, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, told this news organization.

The study was published online Oct. 20 in JAMA Cardiology (doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.4234).

Nearly twofold increased risk

The QT interval-prolonging potential of fluoroquinolone antibiotics are well known. However, evidence linking respiratory fluoroquinolones to adverse cardiac outcomes in the hemodialysis population is limited.

These new observational findings are based on a total of 626,322 antibiotic treatment episodes among 264,968 adults (mean age, 61 years; 51% men) receiving in-center hemodialysis – with respiratory fluoroquinolone making up 40.2% of treatment episodes and amoxicillin-based antibiotic treatment episodes making up 59.8%.

The rate of SCD within 5 days of outpatient initiation of a study antibiotic was 105.7 per 100,000 people prescribed a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) versus with 40.0 per 100,000 prescribed amoxicillin or amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (weighted hazard ratio: 1.95; 95% confidence interval, 1.57-2.41).

The authors estimate that one additional SCD would occur during a 5-day follow-up period for every 2,273 respiratory fluoroquinolone treatment episodes. Consistent associations were seen when follow-up was extended to 7, 10, and 14 days.

“Our data suggest that curtailing respiratory fluoroquinolone prescribing may be one actionable strategy to mitigate SCD risk in the hemodialysis population. However, the associated absolute risk reduction would be relatively small,” wrote the authors.

They noted that the rate of SCD in the hemodialysis population exceeds that of the general population by more than 20-fold. Most patients undergoing hemodialysis have a least one risk factor for drug-induced QT interval prolongation.

In the current study, nearly 20% of hemodialysis patients prescribed a respiratory fluoroquinolone were taking other medications with known risk for torsades de pointes.

“Our results emphasize the importance of performing a thorough medication review and considering pharmacodynamic drug interactions before prescribing new drug therapies for any condition,” Dr. Assimon and colleagues advised.

They suggest that clinicians consider electrocardiographic monitoring before and during fluoroquinolone therapy in hemodialysis patients, especially in high-risk individuals.

Valuable study

Reached for comment, Ankur Shah, MD, of the division of kidney diseases and hypertension, Brown University, Providence, R.I., called the analysis “valuable” and said the results are “consistent with the known association of cardiac arrhythmias with respiratory fluoroquinolone use in the general population, postulated to be due to increased risk of torsades de pointes from QTc prolongation. This abnormal heart rhythm can lead to sudden cardiac death.

“Notably, the population receiving respiratory fluoroquinolones had a higher incidence of cardiac disease at baseline, but the risk persisted after adjustment for this increased burden of comorbidity,” Dr. Shah said in an interview. He was not involved in the current research.

Dr. Shah cautioned that observational data such as these should be considered more “hypothesis-generating than practice-changing, as there may be unrecognized confounders or differences in the population that received the respiratory fluoroquinolones.

“A prospective randomized trial would provide a definitive answer, but in the interim, caution should be taken in using respiratory fluoroquinolones when local bacterial resistance patterns or patient-specific data offer another option,” Dr. Shah concluded.

Dr. Assimon reported receiving grants from the Renal Research Institute (a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care), honoraria from the International Society of Nephrology for serving as a statistical reviewer for Kidney International Reports, and honoraria from the American Society of Nephrology for serving as an editorial fellow for the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A pill for C. difficile works by increasing microbiome diversity

CP101, under development by Finch Therapeutics, proved more effective than a placebo in preventing recurrent infections for up to 24 weeks.

The CP101 capsules contain a powder of freeze-dried human stools from screened donors. They restore natural diversity that has been disrupted by antibiotics, said Jessica Allegretti, MD, MPH a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The treatment offers an alternative to fecal microbiota transplant, which can effectively treat antibiotic-resistant C. difficile infections but is difficult to standardize and administer – and doesn’t have full approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, she added.

“I think this marks a moment in this space where we’re going to have better, safer, and more available options for patients,” she said in an interview. “It’s exciting.”

Dr. Allegretti is an author on three presentations of results from PRISM3, a phase 2 trial of CP101. They will be presented this week at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. These results extend out to 24 weeks, whereas the 8-week results of this trial were presented a year ago at the same meeting.

Study details

The study enrolled 198 people who received antibiotics for recurrent C. difficile infections. Some patients had two or more recurrences, while others had only one recurrence but were 65 years of age or older.

“That was a unique aspect of this study, to see the effect of bringing a therapy like CP101 earlier in the treatment paradigm,” said Dr. Allegretti. “You can imagine for an older, frail, or more fragile patient that you would want to get rid of this [infection] earlier.”

After waiting 2-6 days for the antibiotics to wash out, the researchers randomly assigned 102 of these patients to take the CP101 pills orally and 96 to take placebo pills, both without bowel preparation.

The two groups were not significantly different in age, gender, comorbidities, the number of C. difficile recurrences, or the type of test used to diagnose the infection (PCR-based vs. toxin EIA-based).

After 8 weeks, 74.5% of those given the CP101 pills had not had a recurrence, compared with 61.5% of those given the placebo. The difference was just barely statistically significant (P = .0488).

Sixteen weeks later, the effect endured, with 73.5% of the CP101 group and 59.4% of the placebo group still free of recurrence. The statistical significance of the difference improved slightly (P = .0347).

Drug-related emergent adverse events were similar between the two groups: 16.3% for the CP101 group vs. 19.2% for the placebo group. These were mostly gastrointestinal symptoms, and none were serious.

Some of the patients received vancomycin as a first-line treatment for C. difficile infections, and the researchers wondered if the washout period was not sufficient to purge that antibiotic, leaving enough to interfere with the effectiveness of CP101.

Therefore, they separately analyzed 40 patients treated with fidaxomicin, which they expected to wash out more quickly. Among these patients, 81% who received CP101 were free of recurrences, at 8 weeks and 24 weeks. This compared with 42.1% of those who received the placebo, at both time points. This difference was more statistically significant (P = .0211).

Understanding how it works

To understand better how CP101 achieves its effects, the researchers collected stool samples from the patients and counted the number of different kinds organisms in each sample.

At baseline, the patients had about the same number, but after a week the diversity was greater in the patients treated with CP101, and that difference had increased at week 8. The researchers also found much less diversity of organisms in the stools of those patients who had recurrences of C. difficile infection.

The diversity of microbes in the successfully treated patients appeared to have been introduced by CP101. Dr. Allegretti and colleagues measured the number of organisms in the stool samples that came from CP101. They found that 96% of patients colonized by the CP101 organisms had avoided recurrence of the C. difficile infections, compared with 54.2% of those patients not colonized by these microbes.

“We now have some microbiome-based markers that show us as early as week 1 that the patient is going to be cured or not,” Dr. Allegretti said.

Based on these results, Finch plans to launch a phase 3 trial soon, she said.

The data on colonization is interesting because it has not been found with fecal microbiota transplants, said Purna Kashyap, MBBS, codirector of the Microbiome Program at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn., who was not involved in the study.

But to better interpret the data, it would be helpful to know more about how the placebo and CP101 groups compared at baseline with regard to medications, immunosuppression, and antibiotics used to treat the C. difficile infections, Dr. Kashyap said. He was struck by the lower cure rate in the portion of the placebo group treated with fidaxomicin.

“Overall, I think these are exciting observations based on the data but require careful review of the entire data to make sense of [them], which will happen when it goes through peer review,” he told this news organization in an email.

Several other standardized microbiota restoration products are under development, including at least two other capsules. In contrast to CP101, which is made up of whole stool, VE303 (Vedanta Biosciences) is a “rationally defined bacterial consortium,” and SER-109 (Seres Therapeutics) is a “consortium of highly purified Firmicutes spores.” VE303 has completed a phase 2 trial, and SER-109 has completed a phase 3 trial.

Dr. Allegretti is a consultant for Finch Therapeutics, which funded the trial. Dr. Kashyap has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CP101, under development by Finch Therapeutics, proved more effective than a placebo in preventing recurrent infections for up to 24 weeks.

The CP101 capsules contain a powder of freeze-dried human stools from screened donors. They restore natural diversity that has been disrupted by antibiotics, said Jessica Allegretti, MD, MPH a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The treatment offers an alternative to fecal microbiota transplant, which can effectively treat antibiotic-resistant C. difficile infections but is difficult to standardize and administer – and doesn’t have full approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, she added.

“I think this marks a moment in this space where we’re going to have better, safer, and more available options for patients,” she said in an interview. “It’s exciting.”

Dr. Allegretti is an author on three presentations of results from PRISM3, a phase 2 trial of CP101. They will be presented this week at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. These results extend out to 24 weeks, whereas the 8-week results of this trial were presented a year ago at the same meeting.

Study details

The study enrolled 198 people who received antibiotics for recurrent C. difficile infections. Some patients had two or more recurrences, while others had only one recurrence but were 65 years of age or older.

“That was a unique aspect of this study, to see the effect of bringing a therapy like CP101 earlier in the treatment paradigm,” said Dr. Allegretti. “You can imagine for an older, frail, or more fragile patient that you would want to get rid of this [infection] earlier.”

After waiting 2-6 days for the antibiotics to wash out, the researchers randomly assigned 102 of these patients to take the CP101 pills orally and 96 to take placebo pills, both without bowel preparation.

The two groups were not significantly different in age, gender, comorbidities, the number of C. difficile recurrences, or the type of test used to diagnose the infection (PCR-based vs. toxin EIA-based).

After 8 weeks, 74.5% of those given the CP101 pills had not had a recurrence, compared with 61.5% of those given the placebo. The difference was just barely statistically significant (P = .0488).

Sixteen weeks later, the effect endured, with 73.5% of the CP101 group and 59.4% of the placebo group still free of recurrence. The statistical significance of the difference improved slightly (P = .0347).

Drug-related emergent adverse events were similar between the two groups: 16.3% for the CP101 group vs. 19.2% for the placebo group. These were mostly gastrointestinal symptoms, and none were serious.

Some of the patients received vancomycin as a first-line treatment for C. difficile infections, and the researchers wondered if the washout period was not sufficient to purge that antibiotic, leaving enough to interfere with the effectiveness of CP101.

Therefore, they separately analyzed 40 patients treated with fidaxomicin, which they expected to wash out more quickly. Among these patients, 81% who received CP101 were free of recurrences, at 8 weeks and 24 weeks. This compared with 42.1% of those who received the placebo, at both time points. This difference was more statistically significant (P = .0211).

Understanding how it works

To understand better how CP101 achieves its effects, the researchers collected stool samples from the patients and counted the number of different kinds organisms in each sample.