User login

How can doctors help kids recover from COVID-19 school disruptions?

Physicians may be able to help students get back on track after the pandemic derailed normal schooling, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician suggests.

The disruptions especially affected vulnerable students, such as those with disabilities and those affected by poverty. But academic setbacks occurred across grades and demographics.

“What we know is that, if it was bad before COVID, things are much worse now,” Eric Tridas, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “The pandemic disproportionately affected vulnerable populations. It exacerbated their learning and mental health problems to a high degree.”

In an effort to help kids catch up, pediatricians can provide information to parents about approaches to accelerated academic instruction, Dr. Tridas suggested. They also can monitor for depression and anxiety, and provide appropriate referrals and, if needed, medication, said Dr. Tridas, who is a member of the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities.

Doctors also can collaborate with educators to establish schoolwide plans to address mental health problems, he said.

Dr. Tridas focused on vulnerable populations, including students with neurodevelopmental disorders, as well as students of color, English language learners, and Indigenous populations. But other research presented at the AAP meeting focused on challenges that college students in general encountered during the pandemic.

Nelson Chow, a research intern at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues surveyed college students in June 2020 about academic barriers when their schools switched to virtual learning.

Nearly 80% of the 307 respondents had difficulties concentrating. Many students also agreed that responsibilities at home (57.6%), mental health issues (46.3%), family relationships (37.8%), financial hardships (31.5%), and limited Internet access (25.1%) were among the factors that posed academic barriers.

A larger proportion of Hispanic students reported that responsibilities at home were a challenge, compared with non-Hispanic students, the researchers found.

“It is especially important to have a particular awareness of the cultural and socioeconomic factors that may impact students’ outcomes,” Mr. Chow said in a news release highlighting the research.

Although studies indicate that the pandemic led to academic losses across the board in terms of students not learning as much as usual, these setbacks were more pronounced for vulnerable populations, Dr. Tridas said.

What can busy pediatricians do? “We can at least inquire about how the kids are doing educationally, and with mental health. That’s it. If we do that, we are doing an awful lot.”

Education

Dr. Tridas pointed meeting attendees to a report from the National Center for Learning Disabilities, “Promising Practices to Accelerate Learning for Students with Disabilities During COVID-19 and Beyond,” that he said could be a helpful resource for pediatricians, parents, and educators who want to learn more about accelerated learning approaches.

Research indicates that these strategies “may help in a situation like this,” Dr. Tridas said.

Accelerated approaches typically simplify the curriculum to focus on essential reading, writing, and math skills that most students should acquire by third grade, while capitalizing on students’ strengths and interests.

Despite vulnerable students having fallen farther behind academically, they likely are doing the same thing in school that they were doing before COVID-19, “which was not working to begin with,” he said. “That is why I try to provide parents and pediatricians with ways of ... recognizing when appropriate instruction is being provided.”

Sharing this information does not necessarily mean that schools will implement those strategies, or that schools are not applying them already. Still, making parents aware of these approaches can help, he said.

Emotional health

Social isolation, loss of routine and structure, more screen time, and changes in sleeping and eating patterns during the pandemic are factors that may have exacerbated mental health problems in students.

Vulnerable populations are at higher risk for these issues, and it will be important to monitor these kids for suicidal ideation and depression, especially in middle school and high school, Dr. Tridas said.

Doctors should establish alliances with mental health providers in their communities if they are not able to provide cognitive-behavioral therapy or medication management in their own practices.

And at home and at school, children should have structure and consistency, positive enforcement of appropriate conduct, and a safe environment that allows them to fail and try again, Dr. Tridas said.

Dr. Tridas and Mr. Chow had no relevant financial disclosures.

Physicians may be able to help students get back on track after the pandemic derailed normal schooling, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician suggests.

The disruptions especially affected vulnerable students, such as those with disabilities and those affected by poverty. But academic setbacks occurred across grades and demographics.

“What we know is that, if it was bad before COVID, things are much worse now,” Eric Tridas, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “The pandemic disproportionately affected vulnerable populations. It exacerbated their learning and mental health problems to a high degree.”

In an effort to help kids catch up, pediatricians can provide information to parents about approaches to accelerated academic instruction, Dr. Tridas suggested. They also can monitor for depression and anxiety, and provide appropriate referrals and, if needed, medication, said Dr. Tridas, who is a member of the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities.

Doctors also can collaborate with educators to establish schoolwide plans to address mental health problems, he said.

Dr. Tridas focused on vulnerable populations, including students with neurodevelopmental disorders, as well as students of color, English language learners, and Indigenous populations. But other research presented at the AAP meeting focused on challenges that college students in general encountered during the pandemic.

Nelson Chow, a research intern at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues surveyed college students in June 2020 about academic barriers when their schools switched to virtual learning.

Nearly 80% of the 307 respondents had difficulties concentrating. Many students also agreed that responsibilities at home (57.6%), mental health issues (46.3%), family relationships (37.8%), financial hardships (31.5%), and limited Internet access (25.1%) were among the factors that posed academic barriers.

A larger proportion of Hispanic students reported that responsibilities at home were a challenge, compared with non-Hispanic students, the researchers found.

“It is especially important to have a particular awareness of the cultural and socioeconomic factors that may impact students’ outcomes,” Mr. Chow said in a news release highlighting the research.

Although studies indicate that the pandemic led to academic losses across the board in terms of students not learning as much as usual, these setbacks were more pronounced for vulnerable populations, Dr. Tridas said.

What can busy pediatricians do? “We can at least inquire about how the kids are doing educationally, and with mental health. That’s it. If we do that, we are doing an awful lot.”

Education

Dr. Tridas pointed meeting attendees to a report from the National Center for Learning Disabilities, “Promising Practices to Accelerate Learning for Students with Disabilities During COVID-19 and Beyond,” that he said could be a helpful resource for pediatricians, parents, and educators who want to learn more about accelerated learning approaches.

Research indicates that these strategies “may help in a situation like this,” Dr. Tridas said.

Accelerated approaches typically simplify the curriculum to focus on essential reading, writing, and math skills that most students should acquire by third grade, while capitalizing on students’ strengths and interests.

Despite vulnerable students having fallen farther behind academically, they likely are doing the same thing in school that they were doing before COVID-19, “which was not working to begin with,” he said. “That is why I try to provide parents and pediatricians with ways of ... recognizing when appropriate instruction is being provided.”

Sharing this information does not necessarily mean that schools will implement those strategies, or that schools are not applying them already. Still, making parents aware of these approaches can help, he said.

Emotional health

Social isolation, loss of routine and structure, more screen time, and changes in sleeping and eating patterns during the pandemic are factors that may have exacerbated mental health problems in students.

Vulnerable populations are at higher risk for these issues, and it will be important to monitor these kids for suicidal ideation and depression, especially in middle school and high school, Dr. Tridas said.

Doctors should establish alliances with mental health providers in their communities if they are not able to provide cognitive-behavioral therapy or medication management in their own practices.

And at home and at school, children should have structure and consistency, positive enforcement of appropriate conduct, and a safe environment that allows them to fail and try again, Dr. Tridas said.

Dr. Tridas and Mr. Chow had no relevant financial disclosures.

Physicians may be able to help students get back on track after the pandemic derailed normal schooling, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician suggests.

The disruptions especially affected vulnerable students, such as those with disabilities and those affected by poverty. But academic setbacks occurred across grades and demographics.

“What we know is that, if it was bad before COVID, things are much worse now,” Eric Tridas, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “The pandemic disproportionately affected vulnerable populations. It exacerbated their learning and mental health problems to a high degree.”

In an effort to help kids catch up, pediatricians can provide information to parents about approaches to accelerated academic instruction, Dr. Tridas suggested. They also can monitor for depression and anxiety, and provide appropriate referrals and, if needed, medication, said Dr. Tridas, who is a member of the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities.

Doctors also can collaborate with educators to establish schoolwide plans to address mental health problems, he said.

Dr. Tridas focused on vulnerable populations, including students with neurodevelopmental disorders, as well as students of color, English language learners, and Indigenous populations. But other research presented at the AAP meeting focused on challenges that college students in general encountered during the pandemic.

Nelson Chow, a research intern at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues surveyed college students in June 2020 about academic barriers when their schools switched to virtual learning.

Nearly 80% of the 307 respondents had difficulties concentrating. Many students also agreed that responsibilities at home (57.6%), mental health issues (46.3%), family relationships (37.8%), financial hardships (31.5%), and limited Internet access (25.1%) were among the factors that posed academic barriers.

A larger proportion of Hispanic students reported that responsibilities at home were a challenge, compared with non-Hispanic students, the researchers found.

“It is especially important to have a particular awareness of the cultural and socioeconomic factors that may impact students’ outcomes,” Mr. Chow said in a news release highlighting the research.

Although studies indicate that the pandemic led to academic losses across the board in terms of students not learning as much as usual, these setbacks were more pronounced for vulnerable populations, Dr. Tridas said.

What can busy pediatricians do? “We can at least inquire about how the kids are doing educationally, and with mental health. That’s it. If we do that, we are doing an awful lot.”

Education

Dr. Tridas pointed meeting attendees to a report from the National Center for Learning Disabilities, “Promising Practices to Accelerate Learning for Students with Disabilities During COVID-19 and Beyond,” that he said could be a helpful resource for pediatricians, parents, and educators who want to learn more about accelerated learning approaches.

Research indicates that these strategies “may help in a situation like this,” Dr. Tridas said.

Accelerated approaches typically simplify the curriculum to focus on essential reading, writing, and math skills that most students should acquire by third grade, while capitalizing on students’ strengths and interests.

Despite vulnerable students having fallen farther behind academically, they likely are doing the same thing in school that they were doing before COVID-19, “which was not working to begin with,” he said. “That is why I try to provide parents and pediatricians with ways of ... recognizing when appropriate instruction is being provided.”

Sharing this information does not necessarily mean that schools will implement those strategies, or that schools are not applying them already. Still, making parents aware of these approaches can help, he said.

Emotional health

Social isolation, loss of routine and structure, more screen time, and changes in sleeping and eating patterns during the pandemic are factors that may have exacerbated mental health problems in students.

Vulnerable populations are at higher risk for these issues, and it will be important to monitor these kids for suicidal ideation and depression, especially in middle school and high school, Dr. Tridas said.

Doctors should establish alliances with mental health providers in their communities if they are not able to provide cognitive-behavioral therapy or medication management in their own practices.

And at home and at school, children should have structure and consistency, positive enforcement of appropriate conduct, and a safe environment that allows them to fail and try again, Dr. Tridas said.

Dr. Tridas and Mr. Chow had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAP 2021

Biomarkers may indicate severity of COVID in children

Two biomarkers could potentially indicate which children with SARS-CoV-2 infection will develop severe disease, according to research presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“Most children with COVID-19 present with common symptoms, such as fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which are very similar to other common viruses,” said senior researcher Usha Sethuraman, MD, professor of pediatric emergency medicine at Central Michigan University in Detroit.

“It is impossible, in many instances, to predict which child, even after identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection, is going to develop severe consequences, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome [MIS-C] or severe pneumonia,” she said in an interview.

“In fact, many of these kids have been sent home the first time around as they appeared clinically well, only to return a couple of days later in cardiogenic shock and requiring invasive interventions,” she added. “It would be invaluable to have the ability to know which child is likely to develop severe infection so appropriate disposition can be made and treatment initiated.”

In their prospective observational cohort study, Dr. Sethuraman and her colleagues collected saliva samples from children and adolescents when they were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. They assessed the saliva for micro (mi)RNAs, which are small noncoding RNAs that help regulate gene expression and are “thought to play a role in the regulation of inflammation following an infection,” the researchers write in their poster.

Of the 129 young people assessed, 32 (25%) developed severe infection and 97 (75%) did not. The researchers defined severe infection as an MIS-C diagnosis, death in the 30 days after diagnosis, or the need for at least 2 L of oxygen, inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The expression of 63 miRNAs was significantly different between young people who developed severe infection and those who did not (P < .05). In cases of severe disease, expression was downregulated for 38 of the 63 miRNAs (60%).

“A model of six miRNAs was able to discriminate between severe and nonsevere infections with high sensitivity and accuracy in a preliminary analysis,” Dr. Sethuraman reported. “While salivary miRNA has been shown in other studies to help differentiate persistent concussion in children, we did not expect them to be downregulated in children with severe COVID-19.”

The significant differences in miRNA expression in those with and without severe disease is “striking,” despite this being an interim analysis in a fairly small sample size, said Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

“It will be interesting to see if these findings persist when larger numbers are analyzed,” she told this news organization. “Biomarkers that can predict potential severity can be very useful in making risk and management determinations. A child who has the biomarkers that indicate increased severity can be monitored more closely and complications can be preempted and prevented.”

The largest difference between severe and nonsevere cases was in the expression of miRNA 4495. In addition, miRNA 6125 appears to have prognostic potential, the researchers conclude. And three cytokines from saliva samples were elevated in cases of severe infection, but cytokine levels could not distinguish between severe and nonsevere infections, Dr. Sethuraman said.

If further research confirms these findings and determines that these miRNAs truly can provide insight into the likely course of an infection, it “would be a game changer, clinically,” she added, particularly because saliva samples are less invasive and less painful than blood draws.

The potential applications of these biomarkers could extend beyond children admitted to the hospital, Dr. Mohandas noted.

“For example, it would be a noninvasive and easy method to predict potential severity in a child seen in the emergency room and could help with deciding between observation, admission to the general floor, or admission to the ICU,” she told this news organization. “However, this test is not easily or routinely available at present, and cost and accessibility will be the main factors that will have to be overcome before it can be used for this purpose.”

These findings are preliminary, from a small sample, and require confirmation and validation, Dr. Sethuraman cautioned. And the team only analyzed saliva collected at diagnosis, so they have no data on potential changes in cytokines or miRNAs that occur as the disease progresses.

The next step is to “better characterize what happens with time to these profiles,” she explained. “The role of age, race, and gender differences in saliva biomarker profiles needs additional investigation as well.”

It would also be interesting to see whether varied expression of miRNAs “can help differentiate the various complications after COVID-19, like acute respiratory failure, MIS-C, and long COVID,” said Dr. Mohandas. “That would mean it could be used not only to potentially predict severity, but also to predict longer-term outcomes.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) program. Coauthor Steven D. Hicks, MD, PhD, reports being a paid consultant for Quadrant Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two biomarkers could potentially indicate which children with SARS-CoV-2 infection will develop severe disease, according to research presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“Most children with COVID-19 present with common symptoms, such as fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which are very similar to other common viruses,” said senior researcher Usha Sethuraman, MD, professor of pediatric emergency medicine at Central Michigan University in Detroit.

“It is impossible, in many instances, to predict which child, even after identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection, is going to develop severe consequences, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome [MIS-C] or severe pneumonia,” she said in an interview.

“In fact, many of these kids have been sent home the first time around as they appeared clinically well, only to return a couple of days later in cardiogenic shock and requiring invasive interventions,” she added. “It would be invaluable to have the ability to know which child is likely to develop severe infection so appropriate disposition can be made and treatment initiated.”

In their prospective observational cohort study, Dr. Sethuraman and her colleagues collected saliva samples from children and adolescents when they were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. They assessed the saliva for micro (mi)RNAs, which are small noncoding RNAs that help regulate gene expression and are “thought to play a role in the regulation of inflammation following an infection,” the researchers write in their poster.

Of the 129 young people assessed, 32 (25%) developed severe infection and 97 (75%) did not. The researchers defined severe infection as an MIS-C diagnosis, death in the 30 days after diagnosis, or the need for at least 2 L of oxygen, inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The expression of 63 miRNAs was significantly different between young people who developed severe infection and those who did not (P < .05). In cases of severe disease, expression was downregulated for 38 of the 63 miRNAs (60%).

“A model of six miRNAs was able to discriminate between severe and nonsevere infections with high sensitivity and accuracy in a preliminary analysis,” Dr. Sethuraman reported. “While salivary miRNA has been shown in other studies to help differentiate persistent concussion in children, we did not expect them to be downregulated in children with severe COVID-19.”

The significant differences in miRNA expression in those with and without severe disease is “striking,” despite this being an interim analysis in a fairly small sample size, said Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

“It will be interesting to see if these findings persist when larger numbers are analyzed,” she told this news organization. “Biomarkers that can predict potential severity can be very useful in making risk and management determinations. A child who has the biomarkers that indicate increased severity can be monitored more closely and complications can be preempted and prevented.”

The largest difference between severe and nonsevere cases was in the expression of miRNA 4495. In addition, miRNA 6125 appears to have prognostic potential, the researchers conclude. And three cytokines from saliva samples were elevated in cases of severe infection, but cytokine levels could not distinguish between severe and nonsevere infections, Dr. Sethuraman said.

If further research confirms these findings and determines that these miRNAs truly can provide insight into the likely course of an infection, it “would be a game changer, clinically,” she added, particularly because saliva samples are less invasive and less painful than blood draws.

The potential applications of these biomarkers could extend beyond children admitted to the hospital, Dr. Mohandas noted.

“For example, it would be a noninvasive and easy method to predict potential severity in a child seen in the emergency room and could help with deciding between observation, admission to the general floor, or admission to the ICU,” she told this news organization. “However, this test is not easily or routinely available at present, and cost and accessibility will be the main factors that will have to be overcome before it can be used for this purpose.”

These findings are preliminary, from a small sample, and require confirmation and validation, Dr. Sethuraman cautioned. And the team only analyzed saliva collected at diagnosis, so they have no data on potential changes in cytokines or miRNAs that occur as the disease progresses.

The next step is to “better characterize what happens with time to these profiles,” she explained. “The role of age, race, and gender differences in saliva biomarker profiles needs additional investigation as well.”

It would also be interesting to see whether varied expression of miRNAs “can help differentiate the various complications after COVID-19, like acute respiratory failure, MIS-C, and long COVID,” said Dr. Mohandas. “That would mean it could be used not only to potentially predict severity, but also to predict longer-term outcomes.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) program. Coauthor Steven D. Hicks, MD, PhD, reports being a paid consultant for Quadrant Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two biomarkers could potentially indicate which children with SARS-CoV-2 infection will develop severe disease, according to research presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“Most children with COVID-19 present with common symptoms, such as fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which are very similar to other common viruses,” said senior researcher Usha Sethuraman, MD, professor of pediatric emergency medicine at Central Michigan University in Detroit.

“It is impossible, in many instances, to predict which child, even after identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection, is going to develop severe consequences, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome [MIS-C] or severe pneumonia,” she said in an interview.

“In fact, many of these kids have been sent home the first time around as they appeared clinically well, only to return a couple of days later in cardiogenic shock and requiring invasive interventions,” she added. “It would be invaluable to have the ability to know which child is likely to develop severe infection so appropriate disposition can be made and treatment initiated.”

In their prospective observational cohort study, Dr. Sethuraman and her colleagues collected saliva samples from children and adolescents when they were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. They assessed the saliva for micro (mi)RNAs, which are small noncoding RNAs that help regulate gene expression and are “thought to play a role in the regulation of inflammation following an infection,” the researchers write in their poster.

Of the 129 young people assessed, 32 (25%) developed severe infection and 97 (75%) did not. The researchers defined severe infection as an MIS-C diagnosis, death in the 30 days after diagnosis, or the need for at least 2 L of oxygen, inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The expression of 63 miRNAs was significantly different between young people who developed severe infection and those who did not (P < .05). In cases of severe disease, expression was downregulated for 38 of the 63 miRNAs (60%).

“A model of six miRNAs was able to discriminate between severe and nonsevere infections with high sensitivity and accuracy in a preliminary analysis,” Dr. Sethuraman reported. “While salivary miRNA has been shown in other studies to help differentiate persistent concussion in children, we did not expect them to be downregulated in children with severe COVID-19.”

The significant differences in miRNA expression in those with and without severe disease is “striking,” despite this being an interim analysis in a fairly small sample size, said Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

“It will be interesting to see if these findings persist when larger numbers are analyzed,” she told this news organization. “Biomarkers that can predict potential severity can be very useful in making risk and management determinations. A child who has the biomarkers that indicate increased severity can be monitored more closely and complications can be preempted and prevented.”

The largest difference between severe and nonsevere cases was in the expression of miRNA 4495. In addition, miRNA 6125 appears to have prognostic potential, the researchers conclude. And three cytokines from saliva samples were elevated in cases of severe infection, but cytokine levels could not distinguish between severe and nonsevere infections, Dr. Sethuraman said.

If further research confirms these findings and determines that these miRNAs truly can provide insight into the likely course of an infection, it “would be a game changer, clinically,” she added, particularly because saliva samples are less invasive and less painful than blood draws.

The potential applications of these biomarkers could extend beyond children admitted to the hospital, Dr. Mohandas noted.

“For example, it would be a noninvasive and easy method to predict potential severity in a child seen in the emergency room and could help with deciding between observation, admission to the general floor, or admission to the ICU,” she told this news organization. “However, this test is not easily or routinely available at present, and cost and accessibility will be the main factors that will have to be overcome before it can be used for this purpose.”

These findings are preliminary, from a small sample, and require confirmation and validation, Dr. Sethuraman cautioned. And the team only analyzed saliva collected at diagnosis, so they have no data on potential changes in cytokines or miRNAs that occur as the disease progresses.

The next step is to “better characterize what happens with time to these profiles,” she explained. “The role of age, race, and gender differences in saliva biomarker profiles needs additional investigation as well.”

It would also be interesting to see whether varied expression of miRNAs “can help differentiate the various complications after COVID-19, like acute respiratory failure, MIS-C, and long COVID,” said Dr. Mohandas. “That would mean it could be used not only to potentially predict severity, but also to predict longer-term outcomes.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) program. Coauthor Steven D. Hicks, MD, PhD, reports being a paid consultant for Quadrant Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Kids in foster care get psychotropic meds at ‘alarming’ rates

Children in foster care are far more likely to be prescribed psychotropic medication, compared with children who are not in foster care, an analysis of Medicaid claims data shows.

Different rates of mental health disorders in these groups do not fully explain the “alarming trend,” which persists across psychotropic medication classes, said study author Rachael J. Keefe, MD, MPH.

Dr. Keefe, with Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues analyzed Medicaid claims data from two managed care organizations to compare the prevalence of psychotropic medication use among children in foster care versus children insured by Medicaid but not in foster care. The study focused on claims from the same region in southeast Texas between July 2014 and June 2016.

The researchers included 388,914 children in Medicaid and 8,426 children in foster care in their analysis. They excluded children with a seizure or epilepsy diagnosis.

About 8% of children not in foster care received psychotropic medications, compared with 35% of those in foster care.

Children in foster care were 27 times more likely to receive antipsychotic medication (21.2% of children in foster care vs. 0.8% of children not in foster care) and twice as likely to receive antianxiety medication (6% vs. 3%).

For children in foster care, the rate of alpha-agonist use was 15 times higher, the rate of antidepressant use was 13 times higher, the rate of mood stabilizer use was 26 times higher, and the rate of stimulant use was 6 times higher.

The researchers have a limited understanding of the full context in which these medications were prescribed, and psychotropic medications have a role in the treatment of children in foster care, Dr. Keefe acknowledged.

“We have to be careful not to have a knee-jerk reaction” and inappropriately withhold medication from children in foster care, she said in an interview.

But overprescribing has been a concern. Dr. Keefe leads a foster care clinical service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

“The overprescribing of psychotropic medications to children in foster care is something I feel every day in my clinical practice, but it’s different to see it on paper,” Dr. Keefe said in a news release highlighting the research, which she presented on Oct. 11 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It’s especially shocking to see these dramatic differences in children of preschool and elementary age.”

Misdiagnosis can be a common problem among children in foster care, said Danielle Shaw, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist in Camarillo, Calif., during a question-and-answer period following the presentation.

“I see incorrect diagnoses very frequently,” Dr. Shaw said. “The history of trauma or [adverse childhood experiences] is not even included in the assessment. Mood lability from trauma is misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, despite not meeting criteria. This will justify the use of antipsychotic medication and mood stabilizers. Flashbacks can be mistaken for a psychotic disorder, which again justifies the use of antipsychotic medication.”

Children in foster care have experienced numerous traumatic experiences that affect brain development and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, Dr. Keefe said.

“Although from previous research we know that children in foster care are more likely to carry mental health and developmental disorder diagnoses, this does not account for the significant difference in prescribing practices in this population,” Dr. Keefe said in an interview.

Although the study focused on data in Texas, Dr. Keefe expects similar patterns exist in other regions, based on anecdotal reports. “I work with foster care pediatricians across the country, and many have seen similar concerning trends within their own clinical practices,” she said.

The use of appropriate therapies, minimizing transitions between providers, improved record keeping, the development of deprescribing algorithms, and placement of children in foster care in long-term homes as early as possible are measures that potentially could reduce inappropriate psychotropic prescribing for children in foster care, Dr. Keefe suggested.

The research was funded by a Texas Medical Center Health Policy Research Grant. The study authors and Dr. Shaw had no relevant financial disclosures.

Children in foster care are far more likely to be prescribed psychotropic medication, compared with children who are not in foster care, an analysis of Medicaid claims data shows.

Different rates of mental health disorders in these groups do not fully explain the “alarming trend,” which persists across psychotropic medication classes, said study author Rachael J. Keefe, MD, MPH.

Dr. Keefe, with Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues analyzed Medicaid claims data from two managed care organizations to compare the prevalence of psychotropic medication use among children in foster care versus children insured by Medicaid but not in foster care. The study focused on claims from the same region in southeast Texas between July 2014 and June 2016.

The researchers included 388,914 children in Medicaid and 8,426 children in foster care in their analysis. They excluded children with a seizure or epilepsy diagnosis.

About 8% of children not in foster care received psychotropic medications, compared with 35% of those in foster care.

Children in foster care were 27 times more likely to receive antipsychotic medication (21.2% of children in foster care vs. 0.8% of children not in foster care) and twice as likely to receive antianxiety medication (6% vs. 3%).

For children in foster care, the rate of alpha-agonist use was 15 times higher, the rate of antidepressant use was 13 times higher, the rate of mood stabilizer use was 26 times higher, and the rate of stimulant use was 6 times higher.

The researchers have a limited understanding of the full context in which these medications were prescribed, and psychotropic medications have a role in the treatment of children in foster care, Dr. Keefe acknowledged.

“We have to be careful not to have a knee-jerk reaction” and inappropriately withhold medication from children in foster care, she said in an interview.

But overprescribing has been a concern. Dr. Keefe leads a foster care clinical service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

“The overprescribing of psychotropic medications to children in foster care is something I feel every day in my clinical practice, but it’s different to see it on paper,” Dr. Keefe said in a news release highlighting the research, which she presented on Oct. 11 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It’s especially shocking to see these dramatic differences in children of preschool and elementary age.”

Misdiagnosis can be a common problem among children in foster care, said Danielle Shaw, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist in Camarillo, Calif., during a question-and-answer period following the presentation.

“I see incorrect diagnoses very frequently,” Dr. Shaw said. “The history of trauma or [adverse childhood experiences] is not even included in the assessment. Mood lability from trauma is misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, despite not meeting criteria. This will justify the use of antipsychotic medication and mood stabilizers. Flashbacks can be mistaken for a psychotic disorder, which again justifies the use of antipsychotic medication.”

Children in foster care have experienced numerous traumatic experiences that affect brain development and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, Dr. Keefe said.

“Although from previous research we know that children in foster care are more likely to carry mental health and developmental disorder diagnoses, this does not account for the significant difference in prescribing practices in this population,” Dr. Keefe said in an interview.

Although the study focused on data in Texas, Dr. Keefe expects similar patterns exist in other regions, based on anecdotal reports. “I work with foster care pediatricians across the country, and many have seen similar concerning trends within their own clinical practices,” she said.

The use of appropriate therapies, minimizing transitions between providers, improved record keeping, the development of deprescribing algorithms, and placement of children in foster care in long-term homes as early as possible are measures that potentially could reduce inappropriate psychotropic prescribing for children in foster care, Dr. Keefe suggested.

The research was funded by a Texas Medical Center Health Policy Research Grant. The study authors and Dr. Shaw had no relevant financial disclosures.

Children in foster care are far more likely to be prescribed psychotropic medication, compared with children who are not in foster care, an analysis of Medicaid claims data shows.

Different rates of mental health disorders in these groups do not fully explain the “alarming trend,” which persists across psychotropic medication classes, said study author Rachael J. Keefe, MD, MPH.

Dr. Keefe, with Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues analyzed Medicaid claims data from two managed care organizations to compare the prevalence of psychotropic medication use among children in foster care versus children insured by Medicaid but not in foster care. The study focused on claims from the same region in southeast Texas between July 2014 and June 2016.

The researchers included 388,914 children in Medicaid and 8,426 children in foster care in their analysis. They excluded children with a seizure or epilepsy diagnosis.

About 8% of children not in foster care received psychotropic medications, compared with 35% of those in foster care.

Children in foster care were 27 times more likely to receive antipsychotic medication (21.2% of children in foster care vs. 0.8% of children not in foster care) and twice as likely to receive antianxiety medication (6% vs. 3%).

For children in foster care, the rate of alpha-agonist use was 15 times higher, the rate of antidepressant use was 13 times higher, the rate of mood stabilizer use was 26 times higher, and the rate of stimulant use was 6 times higher.

The researchers have a limited understanding of the full context in which these medications were prescribed, and psychotropic medications have a role in the treatment of children in foster care, Dr. Keefe acknowledged.

“We have to be careful not to have a knee-jerk reaction” and inappropriately withhold medication from children in foster care, she said in an interview.

But overprescribing has been a concern. Dr. Keefe leads a foster care clinical service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

“The overprescribing of psychotropic medications to children in foster care is something I feel every day in my clinical practice, but it’s different to see it on paper,” Dr. Keefe said in a news release highlighting the research, which she presented on Oct. 11 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “It’s especially shocking to see these dramatic differences in children of preschool and elementary age.”

Misdiagnosis can be a common problem among children in foster care, said Danielle Shaw, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist in Camarillo, Calif., during a question-and-answer period following the presentation.

“I see incorrect diagnoses very frequently,” Dr. Shaw said. “The history of trauma or [adverse childhood experiences] is not even included in the assessment. Mood lability from trauma is misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, despite not meeting criteria. This will justify the use of antipsychotic medication and mood stabilizers. Flashbacks can be mistaken for a psychotic disorder, which again justifies the use of antipsychotic medication.”

Children in foster care have experienced numerous traumatic experiences that affect brain development and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, Dr. Keefe said.

“Although from previous research we know that children in foster care are more likely to carry mental health and developmental disorder diagnoses, this does not account for the significant difference in prescribing practices in this population,” Dr. Keefe said in an interview.

Although the study focused on data in Texas, Dr. Keefe expects similar patterns exist in other regions, based on anecdotal reports. “I work with foster care pediatricians across the country, and many have seen similar concerning trends within their own clinical practices,” she said.

The use of appropriate therapies, minimizing transitions between providers, improved record keeping, the development of deprescribing algorithms, and placement of children in foster care in long-term homes as early as possible are measures that potentially could reduce inappropriate psychotropic prescribing for children in foster care, Dr. Keefe suggested.

The research was funded by a Texas Medical Center Health Policy Research Grant. The study authors and Dr. Shaw had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAP 2021

Gender-affirming care ‘can save lives,’ new research shows

Transgender and nonbinary young people experienced less depression and fewer suicidal thoughts after a year of gender-affirming care with hormones or puberty blockers, according to new research.

“Given the high rates of adverse mental health comorbidities, these data provide critical evidence that expansion of gender-affirming care can save lives,” said David J. Inwards-Breland, MD, MPH, chief of adolescent and young adult medicine and codirector of the Center for Gender-Affirming Care at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, during his presentation.

The findings, presented October 11 at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference, were not at all surprising to Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

“The younger we can provide gender-affirming care, the less likely they’re going to have depression, and then the negative outcomes from untreated depression, which includes suicide intent or even suicide completion,” Dr. Breuner told this news organization. “It’s so obvious that we are saving lives by providing gender-affirming care.”

For their study, Dr. Inwards-Breland and his colleagues tracked depression, anxiety, and suicidality in 104 trans and nonbinary people 13 to 21 years of age who received care at the Seattle Children’s gender clinic between August 2017 and June 2018.

The study population consisted of 63 transgender male or male participants, 27 transgender female or female participants, 10 nonbinary participants, and four participants who had not defined their gender identity. Of this cohort, 62.5% were receiving mental health therapy, and 34.7% reported some substance use.

Participants completed the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) at baseline and then at 3, 6, and 12 months. The researchers defined severe depression and severe anxiety as a score of 10 or greater on either scale.

At baseline, 56.7% of the participants had moderate to severe depression, 43.3% reported thoughts of self-harm or suicidal in the previous 2 weeks, and 50.0% had moderate to severe anxiety.

After 12 months of care, participants experienced a 60% decrease in depression (adjusted odds ratio, 0.4) and a 73% decrease in suicidality (aOR, 0.27), after adjustment for temporal trends and sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, level of parental support, ongoing mental health therapy, substance use, and victimization, including bullying, interpersonal violence, neglect, and abuse.

Although the decline in depression and suicidality after gender-affirming treatment was not a surprise, “those drops are huge,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said in an interview.

He said he attributes the improvement to a health care system that “affirms who these young people are” and enables changes that allow their outward appearance to reflect “who they know they are inside.”

There were no significant changes in anxiety during the study period. “Anxiety, I think, is just a little harder to treat, and it takes a little longer to treat,” he explained. And a lot of factors can trigger anxiety, and those can continue during treatment.

The slow pace of changes to gender identity can have an effect on people’s moods. “Since they’re not happening quickly, these young people are still being misgendered, they’re still seeing the body that they don’t feel like they should have, and they have to go to school and go out in public. I think that continues to fuel anxiety with a lot of these young people.”

Family support is important in reducing depression and suicidal thoughts in this population. Parents will often see positive changes after their child receives gender-affirming care, which can help contribute to positive changes in parents’ attitudes, Dr. Inwards-Breland said.

Such changes reinforce “that protective factor of connectedness with family,” he noted. “Families are crucial for any health care, and if there’s that connectedness with families, we know that, clinically, patients do better.”

Balancing risks

Although there are risks associated with gender-affirming hormones and puberty blockers, the risks of not receiving treatment must also be considered.

“Our young people are killing themselves,” he said. “Our young people are developing severe eating disorders that are killing them. Our young people are increasing their substance abuse, homelessness, depression. The list just goes on.”

For trans-masculine and nonbinary masculine patients, the potential permanent changes of hormone therapy include a deeper voice, hair growth, enlargement of the clitoris, and, in some patients, the development of male pattern baldness. In trans and nonbinary feminine patients, potential long-term effects include breast development and an increased risk for fertility issues.

The consent forms required for young people who want gender-affirming hormones or puberty blockers are extensive, with every possible reversible and irreversible effect described in detail, Dr. Breuner said.

“Parents sign them because they want their child to stay alive,” she explained. “When you compare the cost of someone who has severe debilitating depression and dying by suicide with some of the risks associated with gender-affirming hormone therapy, that’s a no-brainer to me.”

This study is limited by the fact that screening tests, not diagnostic tests, were used to identify depression, anxiety, and suicidality, and the fact that the use of antidepression or antianxiety medications was not taken into account, Dr. Inwards-Breland acknowledged.

“I think future studies should look at a mental health evaluation and diagnosis by a mental health provider,” he added. And mental health, gender dysphoria, suicidality, and self-harm should be tracked over the course of treatment.

He also acknowledged the study’s selection bias. All participants sought care at a multidisciplinary gender clinic, so were likely to be privileged and to have supportive families. “There’s a good chance that if we had more trans and nonbinary youth of color, we may have different findings,” he said.

More qualitative research is needed to assess the effect of gender-affirming therapy on the mental health of these patients, Dr. Breuner said.

“Being able to finally come into who you think you are and enjoy expressing who you are in a gender-affirming way has to be positive in such a way that you’re not depressed anymore,” she added. “It has to be tragic for people who cannot stand the body they’re in and cannot talk about it to anybody or express themselves without fear of recourse, to the point that they would be so devastated that they’d want to die by suicide.”

This research was funded by the Seattle Children’s Center for Diversity and Health Equity and the Pacific Hospital Development and Port Authority. Dr. Inwards-Breland and Dr. Breuner have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender and nonbinary young people experienced less depression and fewer suicidal thoughts after a year of gender-affirming care with hormones or puberty blockers, according to new research.

“Given the high rates of adverse mental health comorbidities, these data provide critical evidence that expansion of gender-affirming care can save lives,” said David J. Inwards-Breland, MD, MPH, chief of adolescent and young adult medicine and codirector of the Center for Gender-Affirming Care at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, during his presentation.

The findings, presented October 11 at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference, were not at all surprising to Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

“The younger we can provide gender-affirming care, the less likely they’re going to have depression, and then the negative outcomes from untreated depression, which includes suicide intent or even suicide completion,” Dr. Breuner told this news organization. “It’s so obvious that we are saving lives by providing gender-affirming care.”

For their study, Dr. Inwards-Breland and his colleagues tracked depression, anxiety, and suicidality in 104 trans and nonbinary people 13 to 21 years of age who received care at the Seattle Children’s gender clinic between August 2017 and June 2018.

The study population consisted of 63 transgender male or male participants, 27 transgender female or female participants, 10 nonbinary participants, and four participants who had not defined their gender identity. Of this cohort, 62.5% were receiving mental health therapy, and 34.7% reported some substance use.

Participants completed the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) at baseline and then at 3, 6, and 12 months. The researchers defined severe depression and severe anxiety as a score of 10 or greater on either scale.

At baseline, 56.7% of the participants had moderate to severe depression, 43.3% reported thoughts of self-harm or suicidal in the previous 2 weeks, and 50.0% had moderate to severe anxiety.

After 12 months of care, participants experienced a 60% decrease in depression (adjusted odds ratio, 0.4) and a 73% decrease in suicidality (aOR, 0.27), after adjustment for temporal trends and sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, level of parental support, ongoing mental health therapy, substance use, and victimization, including bullying, interpersonal violence, neglect, and abuse.

Although the decline in depression and suicidality after gender-affirming treatment was not a surprise, “those drops are huge,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said in an interview.

He said he attributes the improvement to a health care system that “affirms who these young people are” and enables changes that allow their outward appearance to reflect “who they know they are inside.”

There were no significant changes in anxiety during the study period. “Anxiety, I think, is just a little harder to treat, and it takes a little longer to treat,” he explained. And a lot of factors can trigger anxiety, and those can continue during treatment.

The slow pace of changes to gender identity can have an effect on people’s moods. “Since they’re not happening quickly, these young people are still being misgendered, they’re still seeing the body that they don’t feel like they should have, and they have to go to school and go out in public. I think that continues to fuel anxiety with a lot of these young people.”

Family support is important in reducing depression and suicidal thoughts in this population. Parents will often see positive changes after their child receives gender-affirming care, which can help contribute to positive changes in parents’ attitudes, Dr. Inwards-Breland said.

Such changes reinforce “that protective factor of connectedness with family,” he noted. “Families are crucial for any health care, and if there’s that connectedness with families, we know that, clinically, patients do better.”

Balancing risks

Although there are risks associated with gender-affirming hormones and puberty blockers, the risks of not receiving treatment must also be considered.

“Our young people are killing themselves,” he said. “Our young people are developing severe eating disorders that are killing them. Our young people are increasing their substance abuse, homelessness, depression. The list just goes on.”

For trans-masculine and nonbinary masculine patients, the potential permanent changes of hormone therapy include a deeper voice, hair growth, enlargement of the clitoris, and, in some patients, the development of male pattern baldness. In trans and nonbinary feminine patients, potential long-term effects include breast development and an increased risk for fertility issues.

The consent forms required for young people who want gender-affirming hormones or puberty blockers are extensive, with every possible reversible and irreversible effect described in detail, Dr. Breuner said.

“Parents sign them because they want their child to stay alive,” she explained. “When you compare the cost of someone who has severe debilitating depression and dying by suicide with some of the risks associated with gender-affirming hormone therapy, that’s a no-brainer to me.”

This study is limited by the fact that screening tests, not diagnostic tests, were used to identify depression, anxiety, and suicidality, and the fact that the use of antidepression or antianxiety medications was not taken into account, Dr. Inwards-Breland acknowledged.

“I think future studies should look at a mental health evaluation and diagnosis by a mental health provider,” he added. And mental health, gender dysphoria, suicidality, and self-harm should be tracked over the course of treatment.

He also acknowledged the study’s selection bias. All participants sought care at a multidisciplinary gender clinic, so were likely to be privileged and to have supportive families. “There’s a good chance that if we had more trans and nonbinary youth of color, we may have different findings,” he said.

More qualitative research is needed to assess the effect of gender-affirming therapy on the mental health of these patients, Dr. Breuner said.

“Being able to finally come into who you think you are and enjoy expressing who you are in a gender-affirming way has to be positive in such a way that you’re not depressed anymore,” she added. “It has to be tragic for people who cannot stand the body they’re in and cannot talk about it to anybody or express themselves without fear of recourse, to the point that they would be so devastated that they’d want to die by suicide.”

This research was funded by the Seattle Children’s Center for Diversity and Health Equity and the Pacific Hospital Development and Port Authority. Dr. Inwards-Breland and Dr. Breuner have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender and nonbinary young people experienced less depression and fewer suicidal thoughts after a year of gender-affirming care with hormones or puberty blockers, according to new research.

“Given the high rates of adverse mental health comorbidities, these data provide critical evidence that expansion of gender-affirming care can save lives,” said David J. Inwards-Breland, MD, MPH, chief of adolescent and young adult medicine and codirector of the Center for Gender-Affirming Care at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, during his presentation.

The findings, presented October 11 at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference, were not at all surprising to Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

“The younger we can provide gender-affirming care, the less likely they’re going to have depression, and then the negative outcomes from untreated depression, which includes suicide intent or even suicide completion,” Dr. Breuner told this news organization. “It’s so obvious that we are saving lives by providing gender-affirming care.”

For their study, Dr. Inwards-Breland and his colleagues tracked depression, anxiety, and suicidality in 104 trans and nonbinary people 13 to 21 years of age who received care at the Seattle Children’s gender clinic between August 2017 and June 2018.

The study population consisted of 63 transgender male or male participants, 27 transgender female or female participants, 10 nonbinary participants, and four participants who had not defined their gender identity. Of this cohort, 62.5% were receiving mental health therapy, and 34.7% reported some substance use.

Participants completed the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) at baseline and then at 3, 6, and 12 months. The researchers defined severe depression and severe anxiety as a score of 10 or greater on either scale.

At baseline, 56.7% of the participants had moderate to severe depression, 43.3% reported thoughts of self-harm or suicidal in the previous 2 weeks, and 50.0% had moderate to severe anxiety.

After 12 months of care, participants experienced a 60% decrease in depression (adjusted odds ratio, 0.4) and a 73% decrease in suicidality (aOR, 0.27), after adjustment for temporal trends and sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, level of parental support, ongoing mental health therapy, substance use, and victimization, including bullying, interpersonal violence, neglect, and abuse.

Although the decline in depression and suicidality after gender-affirming treatment was not a surprise, “those drops are huge,” Dr. Inwards-Breland said in an interview.

He said he attributes the improvement to a health care system that “affirms who these young people are” and enables changes that allow their outward appearance to reflect “who they know they are inside.”

There were no significant changes in anxiety during the study period. “Anxiety, I think, is just a little harder to treat, and it takes a little longer to treat,” he explained. And a lot of factors can trigger anxiety, and those can continue during treatment.

The slow pace of changes to gender identity can have an effect on people’s moods. “Since they’re not happening quickly, these young people are still being misgendered, they’re still seeing the body that they don’t feel like they should have, and they have to go to school and go out in public. I think that continues to fuel anxiety with a lot of these young people.”

Family support is important in reducing depression and suicidal thoughts in this population. Parents will often see positive changes after their child receives gender-affirming care, which can help contribute to positive changes in parents’ attitudes, Dr. Inwards-Breland said.

Such changes reinforce “that protective factor of connectedness with family,” he noted. “Families are crucial for any health care, and if there’s that connectedness with families, we know that, clinically, patients do better.”

Balancing risks

Although there are risks associated with gender-affirming hormones and puberty blockers, the risks of not receiving treatment must also be considered.

“Our young people are killing themselves,” he said. “Our young people are developing severe eating disorders that are killing them. Our young people are increasing their substance abuse, homelessness, depression. The list just goes on.”

For trans-masculine and nonbinary masculine patients, the potential permanent changes of hormone therapy include a deeper voice, hair growth, enlargement of the clitoris, and, in some patients, the development of male pattern baldness. In trans and nonbinary feminine patients, potential long-term effects include breast development and an increased risk for fertility issues.

The consent forms required for young people who want gender-affirming hormones or puberty blockers are extensive, with every possible reversible and irreversible effect described in detail, Dr. Breuner said.

“Parents sign them because they want their child to stay alive,” she explained. “When you compare the cost of someone who has severe debilitating depression and dying by suicide with some of the risks associated with gender-affirming hormone therapy, that’s a no-brainer to me.”

This study is limited by the fact that screening tests, not diagnostic tests, were used to identify depression, anxiety, and suicidality, and the fact that the use of antidepression or antianxiety medications was not taken into account, Dr. Inwards-Breland acknowledged.

“I think future studies should look at a mental health evaluation and diagnosis by a mental health provider,” he added. And mental health, gender dysphoria, suicidality, and self-harm should be tracked over the course of treatment.

He also acknowledged the study’s selection bias. All participants sought care at a multidisciplinary gender clinic, so were likely to be privileged and to have supportive families. “There’s a good chance that if we had more trans and nonbinary youth of color, we may have different findings,” he said.

More qualitative research is needed to assess the effect of gender-affirming therapy on the mental health of these patients, Dr. Breuner said.

“Being able to finally come into who you think you are and enjoy expressing who you are in a gender-affirming way has to be positive in such a way that you’re not depressed anymore,” she added. “It has to be tragic for people who cannot stand the body they’re in and cannot talk about it to anybody or express themselves without fear of recourse, to the point that they would be so devastated that they’d want to die by suicide.”

This research was funded by the Seattle Children’s Center for Diversity and Health Equity and the Pacific Hospital Development and Port Authority. Dr. Inwards-Breland and Dr. Breuner have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Baby-wearing’ poses serious injury risks for infants, ED data show

Baby-wearing – carrying a child against your body in a sling, soft carrier, or other device – is associated with benefits like reduced crying and increased breastfeeding, studies have shown.

But this practice also entails risks. Babies can fall out of carriers, or be injured when an adult carrying them falls, for example.

researchers estimated in a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

To characterize the epidemiology of these injuries, Samantha J. Rowe, MD, chief resident physician at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues analyzed data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System between 2011 and 2020.

They included in their analysis data from patients aged 5 years and younger who sustained an injury associated with a baby-wearing product. Baby harnesses, carriers, slings, framed baby carriers, and soft baby carriers were among the devices included in the study. The researchers used 601 cases to generate national estimates.

An estimated 14,024 patients presented to EDs because of baby-wearing injuries, and 52% of the injuries occurred when a patient fell from the product.

Most injuries (61%) occurred in children aged 5 months and younger; 19.3% of these infants required hospitalization, most often for head injuries.

The investigators found that about 22% of the injuries were associated with a caregiver falling, noted Rachel Y. Moon, MD, who was not involved in the study.

“Carrying a baby changes your center of gravity – and can also obscure your vision of where you’re walking, so adults who use these devices should be cognizant of this,” said Dr. Moon, with the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Dr. Rowe often practiced baby-wearing with her daughter, and found that it was beneficial. And studies have demonstrated various benefits of baby-wearing, including improved thermoregulation and glycemic control.

Still, the new analysis illustrates the potential for baby-wearing products “to cause serious injury, especially in infants 5 months and younger,” Dr. Rowe said. “We need to provide more education to caregivers on safe baby-wearing and continue to improve our safety standards for baby-wearing products.”

Study coauthor Patrick T. Reeves, MD, with the Naval Medical Center at San Diego, offered additional guidance in a news release: “Like when buying a new pair of shoes, parents must be educated on the proper sizing, selection, and wear of baby carriers to prevent injury to themselves and their child.”

Parents also need to ensure that the child’s nose and mouth are not obstructed, Dr. Moon

In a recent article discussing the possible benefits of baby-wearing in terms of helping with breastfeeding, Dr. Moon also pointed out further safety considerations: “No matter which carrier is used, for safety reasons, we need to remind parents that the baby should be positioned so that the head is upright and the nose and mouth are not obstructed.”

The researchers and Dr. Moon had no relevant financial disclosures.

Baby-wearing – carrying a child against your body in a sling, soft carrier, or other device – is associated with benefits like reduced crying and increased breastfeeding, studies have shown.

But this practice also entails risks. Babies can fall out of carriers, or be injured when an adult carrying them falls, for example.

researchers estimated in a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

To characterize the epidemiology of these injuries, Samantha J. Rowe, MD, chief resident physician at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues analyzed data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System between 2011 and 2020.

They included in their analysis data from patients aged 5 years and younger who sustained an injury associated with a baby-wearing product. Baby harnesses, carriers, slings, framed baby carriers, and soft baby carriers were among the devices included in the study. The researchers used 601 cases to generate national estimates.

An estimated 14,024 patients presented to EDs because of baby-wearing injuries, and 52% of the injuries occurred when a patient fell from the product.

Most injuries (61%) occurred in children aged 5 months and younger; 19.3% of these infants required hospitalization, most often for head injuries.

The investigators found that about 22% of the injuries were associated with a caregiver falling, noted Rachel Y. Moon, MD, who was not involved in the study.

“Carrying a baby changes your center of gravity – and can also obscure your vision of where you’re walking, so adults who use these devices should be cognizant of this,” said Dr. Moon, with the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Dr. Rowe often practiced baby-wearing with her daughter, and found that it was beneficial. And studies have demonstrated various benefits of baby-wearing, including improved thermoregulation and glycemic control.

Still, the new analysis illustrates the potential for baby-wearing products “to cause serious injury, especially in infants 5 months and younger,” Dr. Rowe said. “We need to provide more education to caregivers on safe baby-wearing and continue to improve our safety standards for baby-wearing products.”

Study coauthor Patrick T. Reeves, MD, with the Naval Medical Center at San Diego, offered additional guidance in a news release: “Like when buying a new pair of shoes, parents must be educated on the proper sizing, selection, and wear of baby carriers to prevent injury to themselves and their child.”

Parents also need to ensure that the child’s nose and mouth are not obstructed, Dr. Moon

In a recent article discussing the possible benefits of baby-wearing in terms of helping with breastfeeding, Dr. Moon also pointed out further safety considerations: “No matter which carrier is used, for safety reasons, we need to remind parents that the baby should be positioned so that the head is upright and the nose and mouth are not obstructed.”

The researchers and Dr. Moon had no relevant financial disclosures.

Baby-wearing – carrying a child against your body in a sling, soft carrier, or other device – is associated with benefits like reduced crying and increased breastfeeding, studies have shown.

But this practice also entails risks. Babies can fall out of carriers, or be injured when an adult carrying them falls, for example.

researchers estimated in a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

To characterize the epidemiology of these injuries, Samantha J. Rowe, MD, chief resident physician at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues analyzed data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System between 2011 and 2020.

They included in their analysis data from patients aged 5 years and younger who sustained an injury associated with a baby-wearing product. Baby harnesses, carriers, slings, framed baby carriers, and soft baby carriers were among the devices included in the study. The researchers used 601 cases to generate national estimates.

An estimated 14,024 patients presented to EDs because of baby-wearing injuries, and 52% of the injuries occurred when a patient fell from the product.

Most injuries (61%) occurred in children aged 5 months and younger; 19.3% of these infants required hospitalization, most often for head injuries.

The investigators found that about 22% of the injuries were associated with a caregiver falling, noted Rachel Y. Moon, MD, who was not involved in the study.

“Carrying a baby changes your center of gravity – and can also obscure your vision of where you’re walking, so adults who use these devices should be cognizant of this,” said Dr. Moon, with the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Dr. Rowe often practiced baby-wearing with her daughter, and found that it was beneficial. And studies have demonstrated various benefits of baby-wearing, including improved thermoregulation and glycemic control.

Still, the new analysis illustrates the potential for baby-wearing products “to cause serious injury, especially in infants 5 months and younger,” Dr. Rowe said. “We need to provide more education to caregivers on safe baby-wearing and continue to improve our safety standards for baby-wearing products.”

Study coauthor Patrick T. Reeves, MD, with the Naval Medical Center at San Diego, offered additional guidance in a news release: “Like when buying a new pair of shoes, parents must be educated on the proper sizing, selection, and wear of baby carriers to prevent injury to themselves and their child.”

Parents also need to ensure that the child’s nose and mouth are not obstructed, Dr. Moon

In a recent article discussing the possible benefits of baby-wearing in terms of helping with breastfeeding, Dr. Moon also pointed out further safety considerations: “No matter which carrier is used, for safety reasons, we need to remind parents that the baby should be positioned so that the head is upright and the nose and mouth are not obstructed.”

The researchers and Dr. Moon had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAP 2021

Pediatricians can effectively promote gun safety

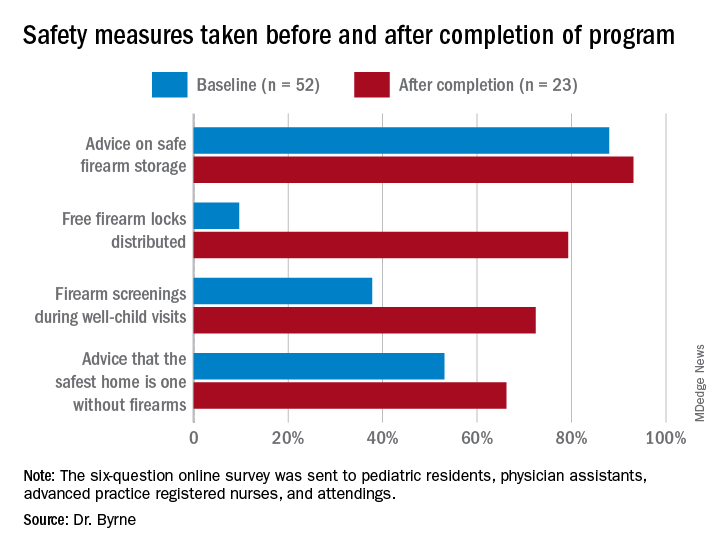

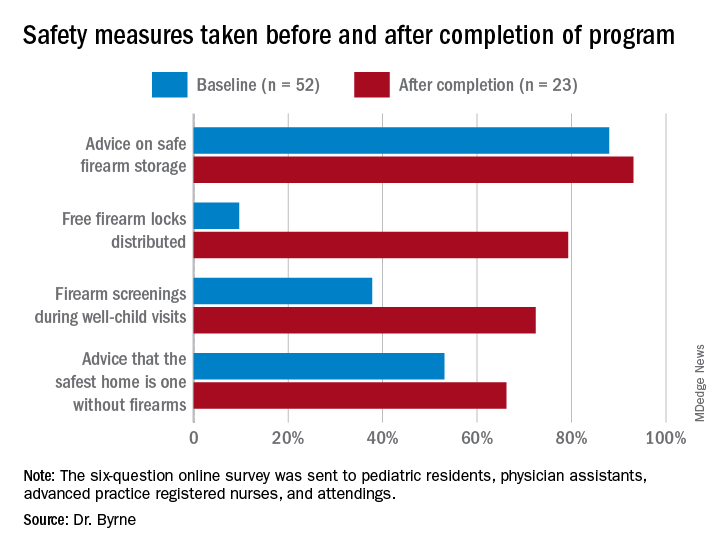

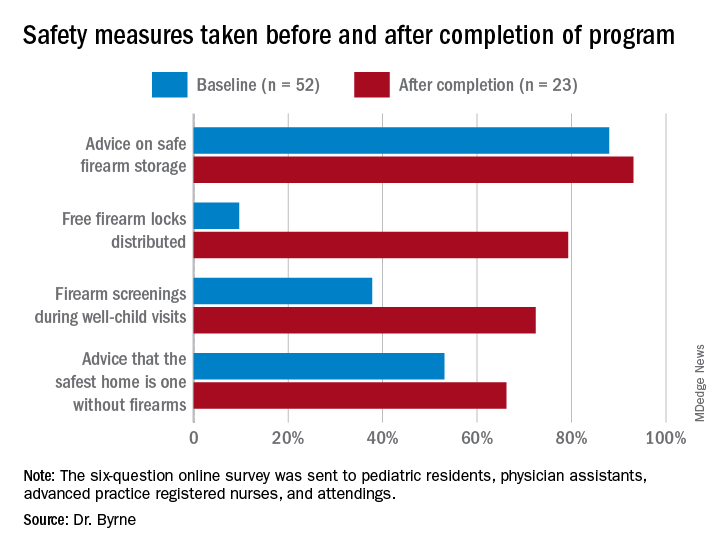

When pediatricians and other pediatric providers are given training and resource materials, levels of firearm screenings and anticipatory guidance about firearm safety increase significantly, according to two new studies presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“With the rise in firearm sales and injuries during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is more important than ever that pediatricians address the firearm epidemic,” said Alexandra Byrne, MD, a pediatric resident at the University of Florida in Gainesville, who presented one of the studies.

There were 4.3 million more firearms purchased from March through July 2020 than expected, a recent study estimates, and 4,075 more firearm injuries than expected from April through July 2020.

In states with more excess purchases, firearm injuries related to domestic violence increased in April (rate ratio, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.32-5.93) and May (RR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.19-2.91) 2020. However, excess gun purchases had no effect on rates of firearm violence outside the home.

In addition to the link between firearms in the home and domestic violence, they are also linked to a three- to fourfold greater risk for teen suicide, and both depression and suicidal thoughts have risen in teens during the pandemic.

“The data are pretty clear that if you have an unlocked, loaded weapon in your home, and you have a kid who’s depressed or anxious or dysregulated or doing maladaptive things for the pandemic, they’re much more likely to inadvertently take their own or someone else’s life by grabbing [a gun],” said Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

However, there is no difference in gun ownership or gun-safety measures between homes with and without at-risk children, previous research shows.

Training, guidance, and locks

Previous research has also shown that there has been a reluctance by pediatricians to conduct firearm screenings and counsel parents about gun safety in the home.

For their two-step program, Dr. Byrne’s team used a plan-do-study-act approach. They started by providing training on firearm safety, evidence-based recommendations for firearm screening, and anticipatory guidance regarding safe firearm storage to members of the general pediatrics division at the University of Florida. And they supplied clinics with free firearm locks.

Next they supplied clinics with posters and educational cards from the Be SMART campaign, an initiative of the Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, which provides materials for anyone, including physicians, to use.

During their study, the researchers sent three anonymous six-question online surveys – at baseline and 3 to 4 months after each of the two steps – to pediatric residents, physician assistants, advanced practice registered nurses, and attendings to assess the project. There were 52 responses to the first survey, for a response rate of 58.4%, 42 responses to the second survey, for a response rate of 47.2%, and 23 responses to the third survey, for a rate of response 25.8%.

The program nearly doubled screenings during well-child visits and dramatically increased the proportion of families who received a firearm lock when they told providers they had a firearm at home.