User login

-

Suits or joggers? A doctor’s dress code

Look at this guy – NFL Chargers jersey and shorts with a RVCA hat on backward. And next to him, a woman wearing her spin-class-Lulu gear. There’s also a guy sporting a 2016 San Diego Rock ‘n Roll Marathon Tee. And that young woman is actually wearing slippers. A visitor from the 1950s would be thunderstruck to see such casual wear on people waiting to board a plane. Photos from that era show men buttoned up in white shirt and tie and women wearing Chanel with hats and white gloves. This dramatic transformation from formal to unfussy wear cuts through all social situations, including in my office. As a new doc out of residency, I used to wear a tie and shoes that could hold a shine. Now I wear jogger scrubs and sneakers. Rather than be offended by the lack of formality though, patients seem to appreciate it. Should they?

At first glance this seems to be a modern phenomenon. The reasons for casual wear today are manifold: about one-third of people work from home, Millennials are taking over with their TikTok values and general irreverence, COVID made us all fat and lazy. Heck, even the U.S. Senate briefly abolished the requirement to wear suits on the Senate floor. But getting dressed up was never to signal that you are elite or superior to others. It’s the opposite. To get dressed is a signal that you are serving others, a tradition that is as old as society.

Think of Downton Abbey as an example. The servants were always required to be smartly dressed when working, whereas members of the family could be dressed up or not. It’s clear who is serving whom. This tradition lives today in the hospitality industry. When you mosey into the lobby of a luxury hotel in your Rainbow sandals you can expect everyone who greets you will be in finery, signaling that they put in effort to serve you. You’ll find the same for all staff at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., which is no coincidence.

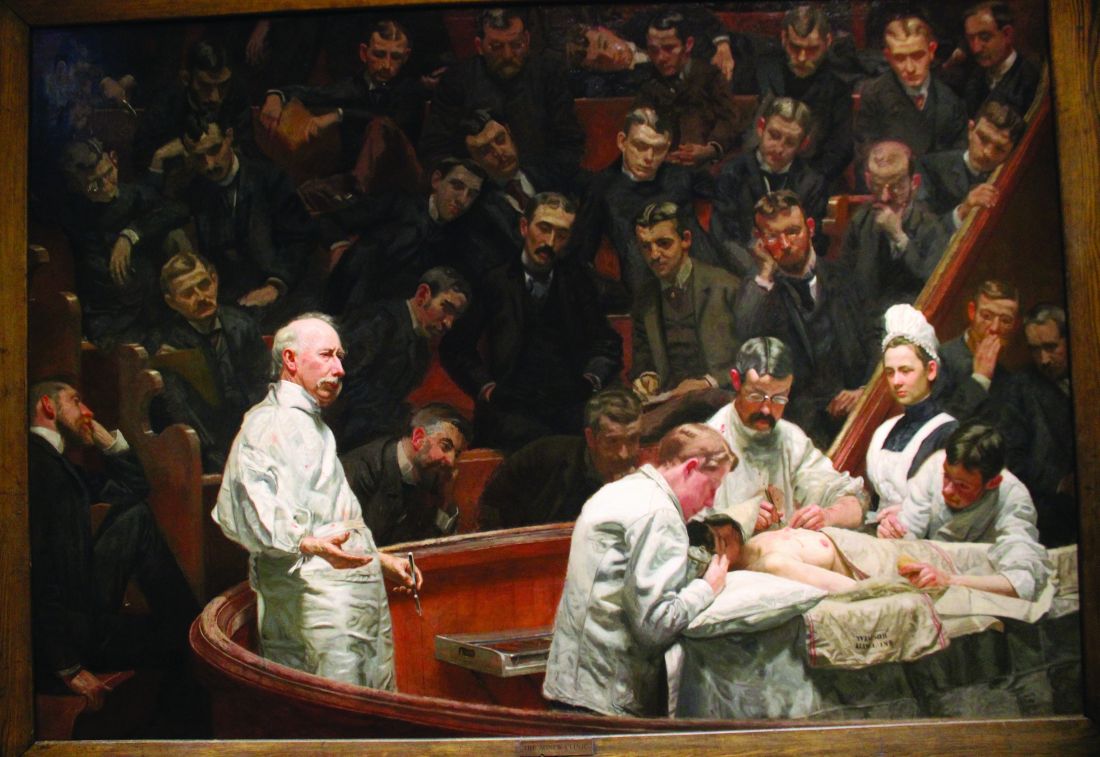

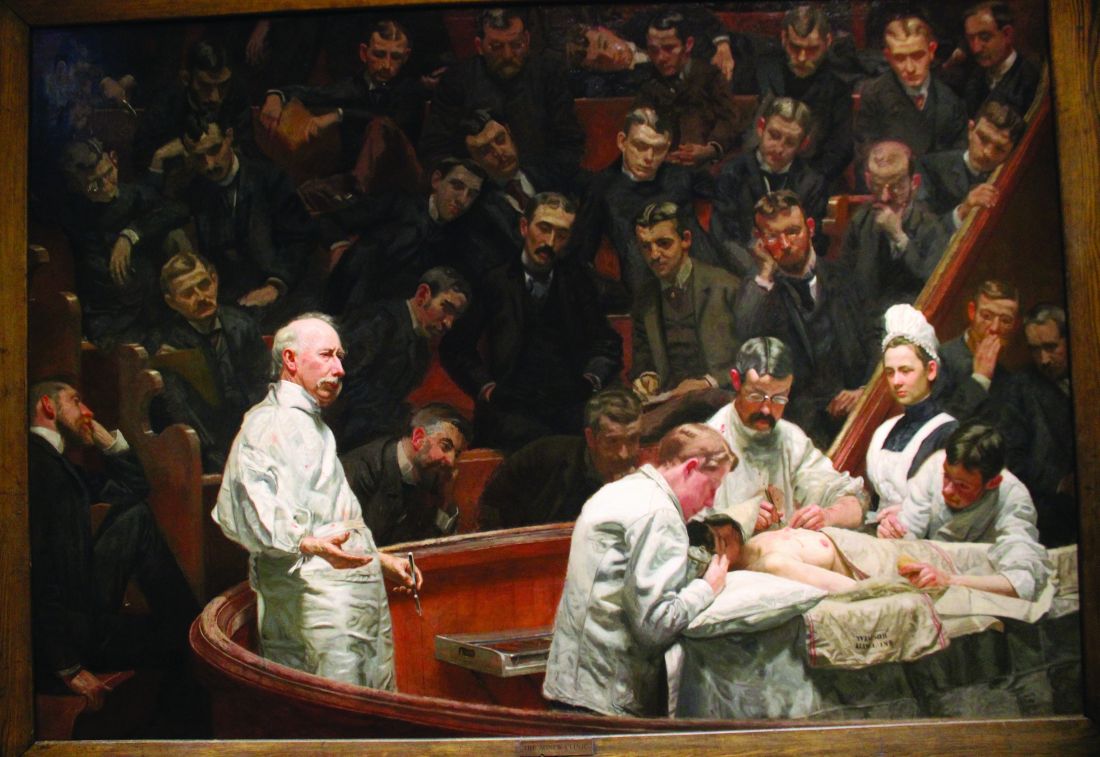

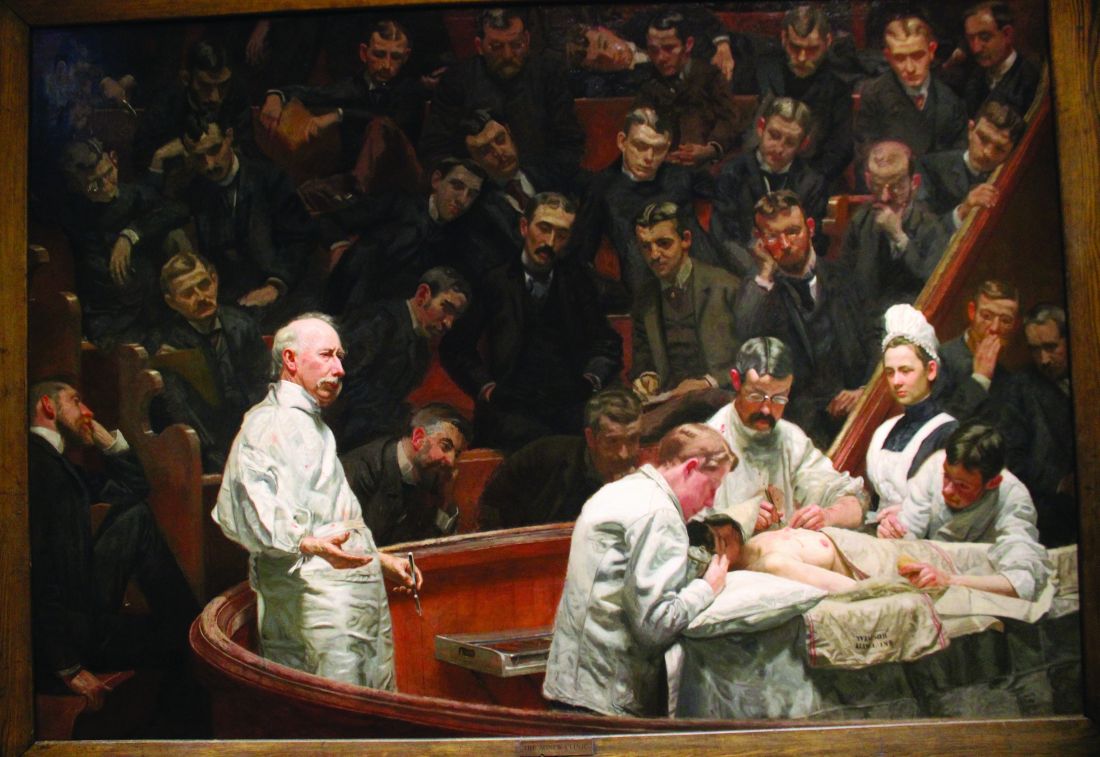

Suits used to be standard in medicine. In the 19th century, physicians wore formal black-tie when seeing patients. Unlike hospitality however, we had good reason to eschew the tradition: germs. Once we figured out that our pus-stained ties and jackets were doing harm, we switched to wearing sanitized uniforms. Casual wear for doctors isn’t a modern phenomenon after all, then. For proof, compare Thomas Eakins painting “The Gross Clinic” (1875) with his later “The Agnew Clinic” (1889). In the former, Dr. Gross is portrayed in formal black wear, bloody hand and all. In the latter, Dr. Agnew is wearing white FIGS (or the 1890’s equivalent anyway). Similarly, nurses uniforms traditionally resembled kitchen servants, with criss-cross aprons and floor length skirts. It wasn’t until the 1980’s that nurses stopped wearing dresses and white caps.

In the operating theater it’s obviously critical that we wear sanitized scrubs to mitigate the risk of infection. Originally white to signal cleanliness, scrubs were changed to blue-green because surgeons were blinded by the lights bouncing off the uniforms. (Green is also opposite red on the color wheel, supposedly enhancing the ability to distinguish shades of red).

But Over time we’ve lost significant autonomy in our practice and lost a little respect from our patients. Payers tell us what to do. Patients question our expertise. Choosing what we wear is one of the few bits of medicine we still have agency. Pewter or pink, joggers or cargo pants, we get to choose.

The last time I flew British Airways everyone was in lounge wear, except the flight crew, of course. They were all smartly dressed. Recently British Airways rolled out updated, slightly more relaxed dress codes. Very modern, but I wonder if in a way we’re not all just a bit worse off.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Look at this guy – NFL Chargers jersey and shorts with a RVCA hat on backward. And next to him, a woman wearing her spin-class-Lulu gear. There’s also a guy sporting a 2016 San Diego Rock ‘n Roll Marathon Tee. And that young woman is actually wearing slippers. A visitor from the 1950s would be thunderstruck to see such casual wear on people waiting to board a plane. Photos from that era show men buttoned up in white shirt and tie and women wearing Chanel with hats and white gloves. This dramatic transformation from formal to unfussy wear cuts through all social situations, including in my office. As a new doc out of residency, I used to wear a tie and shoes that could hold a shine. Now I wear jogger scrubs and sneakers. Rather than be offended by the lack of formality though, patients seem to appreciate it. Should they?

At first glance this seems to be a modern phenomenon. The reasons for casual wear today are manifold: about one-third of people work from home, Millennials are taking over with their TikTok values and general irreverence, COVID made us all fat and lazy. Heck, even the U.S. Senate briefly abolished the requirement to wear suits on the Senate floor. But getting dressed up was never to signal that you are elite or superior to others. It’s the opposite. To get dressed is a signal that you are serving others, a tradition that is as old as society.

Think of Downton Abbey as an example. The servants were always required to be smartly dressed when working, whereas members of the family could be dressed up or not. It’s clear who is serving whom. This tradition lives today in the hospitality industry. When you mosey into the lobby of a luxury hotel in your Rainbow sandals you can expect everyone who greets you will be in finery, signaling that they put in effort to serve you. You’ll find the same for all staff at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., which is no coincidence.

Suits used to be standard in medicine. In the 19th century, physicians wore formal black-tie when seeing patients. Unlike hospitality however, we had good reason to eschew the tradition: germs. Once we figured out that our pus-stained ties and jackets were doing harm, we switched to wearing sanitized uniforms. Casual wear for doctors isn’t a modern phenomenon after all, then. For proof, compare Thomas Eakins painting “The Gross Clinic” (1875) with his later “The Agnew Clinic” (1889). In the former, Dr. Gross is portrayed in formal black wear, bloody hand and all. In the latter, Dr. Agnew is wearing white FIGS (or the 1890’s equivalent anyway). Similarly, nurses uniforms traditionally resembled kitchen servants, with criss-cross aprons and floor length skirts. It wasn’t until the 1980’s that nurses stopped wearing dresses and white caps.

In the operating theater it’s obviously critical that we wear sanitized scrubs to mitigate the risk of infection. Originally white to signal cleanliness, scrubs were changed to blue-green because surgeons were blinded by the lights bouncing off the uniforms. (Green is also opposite red on the color wheel, supposedly enhancing the ability to distinguish shades of red).

But Over time we’ve lost significant autonomy in our practice and lost a little respect from our patients. Payers tell us what to do. Patients question our expertise. Choosing what we wear is one of the few bits of medicine we still have agency. Pewter or pink, joggers or cargo pants, we get to choose.

The last time I flew British Airways everyone was in lounge wear, except the flight crew, of course. They were all smartly dressed. Recently British Airways rolled out updated, slightly more relaxed dress codes. Very modern, but I wonder if in a way we’re not all just a bit worse off.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Look at this guy – NFL Chargers jersey and shorts with a RVCA hat on backward. And next to him, a woman wearing her spin-class-Lulu gear. There’s also a guy sporting a 2016 San Diego Rock ‘n Roll Marathon Tee. And that young woman is actually wearing slippers. A visitor from the 1950s would be thunderstruck to see such casual wear on people waiting to board a plane. Photos from that era show men buttoned up in white shirt and tie and women wearing Chanel with hats and white gloves. This dramatic transformation from formal to unfussy wear cuts through all social situations, including in my office. As a new doc out of residency, I used to wear a tie and shoes that could hold a shine. Now I wear jogger scrubs and sneakers. Rather than be offended by the lack of formality though, patients seem to appreciate it. Should they?

At first glance this seems to be a modern phenomenon. The reasons for casual wear today are manifold: about one-third of people work from home, Millennials are taking over with their TikTok values and general irreverence, COVID made us all fat and lazy. Heck, even the U.S. Senate briefly abolished the requirement to wear suits on the Senate floor. But getting dressed up was never to signal that you are elite or superior to others. It’s the opposite. To get dressed is a signal that you are serving others, a tradition that is as old as society.

Think of Downton Abbey as an example. The servants were always required to be smartly dressed when working, whereas members of the family could be dressed up or not. It’s clear who is serving whom. This tradition lives today in the hospitality industry. When you mosey into the lobby of a luxury hotel in your Rainbow sandals you can expect everyone who greets you will be in finery, signaling that they put in effort to serve you. You’ll find the same for all staff at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., which is no coincidence.

Suits used to be standard in medicine. In the 19th century, physicians wore formal black-tie when seeing patients. Unlike hospitality however, we had good reason to eschew the tradition: germs. Once we figured out that our pus-stained ties and jackets were doing harm, we switched to wearing sanitized uniforms. Casual wear for doctors isn’t a modern phenomenon after all, then. For proof, compare Thomas Eakins painting “The Gross Clinic” (1875) with his later “The Agnew Clinic” (1889). In the former, Dr. Gross is portrayed in formal black wear, bloody hand and all. In the latter, Dr. Agnew is wearing white FIGS (or the 1890’s equivalent anyway). Similarly, nurses uniforms traditionally resembled kitchen servants, with criss-cross aprons and floor length skirts. It wasn’t until the 1980’s that nurses stopped wearing dresses and white caps.

In the operating theater it’s obviously critical that we wear sanitized scrubs to mitigate the risk of infection. Originally white to signal cleanliness, scrubs were changed to blue-green because surgeons were blinded by the lights bouncing off the uniforms. (Green is also opposite red on the color wheel, supposedly enhancing the ability to distinguish shades of red).

But Over time we’ve lost significant autonomy in our practice and lost a little respect from our patients. Payers tell us what to do. Patients question our expertise. Choosing what we wear is one of the few bits of medicine we still have agency. Pewter or pink, joggers or cargo pants, we get to choose.

The last time I flew British Airways everyone was in lounge wear, except the flight crew, of course. They were all smartly dressed. Recently British Airways rolled out updated, slightly more relaxed dress codes. Very modern, but I wonder if in a way we’re not all just a bit worse off.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

When to treat DLBCL with radiotherapy?

SAN DIEGO –

For example, radiation may not be needed for advanced-stage patients who’ve received at least four cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone plus rituximab), and whose PET scans show no sign of disease at interim or end-of treatment phases, said Joanna Yang, MD, MPH, of Washington University in St. Louis, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

These patients “may be able to omit radiotherapy without sacrificing good outcomes,” Dr. Yang said. In contrast, those whose PET scans show signs of disease at interim and end-of-treatment points may benefit from radiotherapy to selected sites, she said.

Dr. Yang highlighted a 2021 study in Blood that tracked 723 patients with advanced-stage DLBCL who were diagnosed from 2005 to 2017. All were treated with R-CHOP, and some of those who were PET-positive – that is, showing signs of malignant disease – were treated with radiotherapy.

Over a mean follow-up of 4.3 years, the study reported “time to progression and overall survival at 3 years were 83% vs. 56% and 87% vs. 64% in patients with PET-NEG and PET-POS scans, respectively.”

These findings aren’t surprising, Dr. Yang said. But “the PET-positive patients who got radiation actually had outcomes that came close to the outcomes that the PET-negative patients were able to achieve.” Their 3-year overall survival was 80% vs. 87% in the PET-negative, no-radiation group vs. 44% in the PET-positive, no-radiation group.

Dr. Yang cautioned, however, that withholding radiation in PET-negative patients isn’t right for everyone: “This doesn’t mean this should be the approach for every single patient.”

What about early-stage DLBCL? In patients without risk factors, Dr. Yang recommends PET scans after four treatments with R-CHOP. “Getting that end-of-treatment PET is going to be super-critical because that’s going to help guide you in terms of the patients who you may feel comfortable omitting radiation versus the patients who remain PET-positive at the end of chemotherapy. Many places will also add an interim PET as well.”

According to her, radiotherapy is appropriate in patients who are PET-positive, based on the findings of the FLYER and LYSA-GOELAMS 02-03 trials.

In early-stage patients who have risk factors such as advanced age or bulky or extra-nodal disease, Dr. Yang suggests examining interim PET scans after three treatments with R-CHOP. If they are negative, another R-CHOP treatment is appropriate – with or without radiotherapy.

“There’s a lot that goes into that decision. The first thing I think about in patients who have risk factors is: What salvage options are available for my patient? Can they tolerate these salvage option? If they’re older, they might not be eligible for auto [autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation]. If they’re frail, they might not be eligible for auto or CAR T cells. If they have bulk, it’s certainly an area of concern. It seems like radiation does help control disease in areas of bulk for patients with DLBCL.”

If these patients are PET-positive, go directly to radiotherapy, Dr. Yang advised. Trials that support this approach include S1001, LYSA-GOELAMS 02-03, and RICOVER-noRTH, she said.

What about double-hit and triple-hit lymphomas, which are especially aggressive due to genetic variations? Research suggests that “even if double hit/triple hit is not responding to chemo, it still responds to radiation,” Dr. Yang said.

In regard to advanced-stage disease, “if patients are receiving full-dose chemo for least six cycles, I use that end-of-treatment PET to help guide me. And then I make an individualized decision based on how bulky that disease is, where the location is, how morbid a relapse would be. If they’re older or receiving reduced-dose chemotherapy, then I’ll more seriously consider radiation just because there are limited options for these patients. And we know that DLCBL is most commonly a disease of the elderly.”

In an adjoining presentation at ASTRO, Andrea Ng, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School/Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, Boston, discussed which patients with incomplete response or refractory/relapsed DLCBL can benefit from radiotherapy.

She highlighted patients with good partial response and end-of-treatment PET-positive with evidence of residual 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose activity via PET scan (Deauville 4/5) – a group that “we’re increasingly seeing.” In these patients, “radiation can be quite effective” at doses of 36-45 Gy. She highlighted a study from 2011 that linked consolidation radiotherapy to 5-year event-free survival in 65% of patients.

As for relapsed/refractory disease in patients who aren’t candidates for further systemic therapy – the “frail without good options” – Dr. Ng said data about salvage radiotherapy is limited. However, a 2015 study tracked 65 patients who were treated with a median dose of 40 Gy with “curative” intent. Local control was “not great” at 72% at 2 years, Dr. Ng said, while overall survival was 60% and progress-free survival was 46%.

Dr. Ng, who was one of this study’s authors, said several groups did better: Those with refractory vs. relapsed disease and those who were responsive to chemotherapy vs. those who were not.

She also highlighted a similar 2019 study of 32 patients with refractory/relapsed disease treated with salvage radiotherapy (median dose of 42.7 Gy) found that 61.8% reached progress-free survival at 5 years – a better outcome.

Dr. Yang has no disclosures. Dr. Ng discloses royalties from UpToDate and Elsevier.

SAN DIEGO –

For example, radiation may not be needed for advanced-stage patients who’ve received at least four cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone plus rituximab), and whose PET scans show no sign of disease at interim or end-of treatment phases, said Joanna Yang, MD, MPH, of Washington University in St. Louis, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

These patients “may be able to omit radiotherapy without sacrificing good outcomes,” Dr. Yang said. In contrast, those whose PET scans show signs of disease at interim and end-of-treatment points may benefit from radiotherapy to selected sites, she said.

Dr. Yang highlighted a 2021 study in Blood that tracked 723 patients with advanced-stage DLBCL who were diagnosed from 2005 to 2017. All were treated with R-CHOP, and some of those who were PET-positive – that is, showing signs of malignant disease – were treated with radiotherapy.

Over a mean follow-up of 4.3 years, the study reported “time to progression and overall survival at 3 years were 83% vs. 56% and 87% vs. 64% in patients with PET-NEG and PET-POS scans, respectively.”

These findings aren’t surprising, Dr. Yang said. But “the PET-positive patients who got radiation actually had outcomes that came close to the outcomes that the PET-negative patients were able to achieve.” Their 3-year overall survival was 80% vs. 87% in the PET-negative, no-radiation group vs. 44% in the PET-positive, no-radiation group.

Dr. Yang cautioned, however, that withholding radiation in PET-negative patients isn’t right for everyone: “This doesn’t mean this should be the approach for every single patient.”

What about early-stage DLBCL? In patients without risk factors, Dr. Yang recommends PET scans after four treatments with R-CHOP. “Getting that end-of-treatment PET is going to be super-critical because that’s going to help guide you in terms of the patients who you may feel comfortable omitting radiation versus the patients who remain PET-positive at the end of chemotherapy. Many places will also add an interim PET as well.”

According to her, radiotherapy is appropriate in patients who are PET-positive, based on the findings of the FLYER and LYSA-GOELAMS 02-03 trials.

In early-stage patients who have risk factors such as advanced age or bulky or extra-nodal disease, Dr. Yang suggests examining interim PET scans after three treatments with R-CHOP. If they are negative, another R-CHOP treatment is appropriate – with or without radiotherapy.

“There’s a lot that goes into that decision. The first thing I think about in patients who have risk factors is: What salvage options are available for my patient? Can they tolerate these salvage option? If they’re older, they might not be eligible for auto [autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation]. If they’re frail, they might not be eligible for auto or CAR T cells. If they have bulk, it’s certainly an area of concern. It seems like radiation does help control disease in areas of bulk for patients with DLBCL.”

If these patients are PET-positive, go directly to radiotherapy, Dr. Yang advised. Trials that support this approach include S1001, LYSA-GOELAMS 02-03, and RICOVER-noRTH, she said.

What about double-hit and triple-hit lymphomas, which are especially aggressive due to genetic variations? Research suggests that “even if double hit/triple hit is not responding to chemo, it still responds to radiation,” Dr. Yang said.

In regard to advanced-stage disease, “if patients are receiving full-dose chemo for least six cycles, I use that end-of-treatment PET to help guide me. And then I make an individualized decision based on how bulky that disease is, where the location is, how morbid a relapse would be. If they’re older or receiving reduced-dose chemotherapy, then I’ll more seriously consider radiation just because there are limited options for these patients. And we know that DLCBL is most commonly a disease of the elderly.”

In an adjoining presentation at ASTRO, Andrea Ng, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School/Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, Boston, discussed which patients with incomplete response or refractory/relapsed DLCBL can benefit from radiotherapy.

She highlighted patients with good partial response and end-of-treatment PET-positive with evidence of residual 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose activity via PET scan (Deauville 4/5) – a group that “we’re increasingly seeing.” In these patients, “radiation can be quite effective” at doses of 36-45 Gy. She highlighted a study from 2011 that linked consolidation radiotherapy to 5-year event-free survival in 65% of patients.

As for relapsed/refractory disease in patients who aren’t candidates for further systemic therapy – the “frail without good options” – Dr. Ng said data about salvage radiotherapy is limited. However, a 2015 study tracked 65 patients who were treated with a median dose of 40 Gy with “curative” intent. Local control was “not great” at 72% at 2 years, Dr. Ng said, while overall survival was 60% and progress-free survival was 46%.

Dr. Ng, who was one of this study’s authors, said several groups did better: Those with refractory vs. relapsed disease and those who were responsive to chemotherapy vs. those who were not.

She also highlighted a similar 2019 study of 32 patients with refractory/relapsed disease treated with salvage radiotherapy (median dose of 42.7 Gy) found that 61.8% reached progress-free survival at 5 years – a better outcome.

Dr. Yang has no disclosures. Dr. Ng discloses royalties from UpToDate and Elsevier.

SAN DIEGO –

For example, radiation may not be needed for advanced-stage patients who’ve received at least four cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone plus rituximab), and whose PET scans show no sign of disease at interim or end-of treatment phases, said Joanna Yang, MD, MPH, of Washington University in St. Louis, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

These patients “may be able to omit radiotherapy without sacrificing good outcomes,” Dr. Yang said. In contrast, those whose PET scans show signs of disease at interim and end-of-treatment points may benefit from radiotherapy to selected sites, she said.

Dr. Yang highlighted a 2021 study in Blood that tracked 723 patients with advanced-stage DLBCL who were diagnosed from 2005 to 2017. All were treated with R-CHOP, and some of those who were PET-positive – that is, showing signs of malignant disease – were treated with radiotherapy.

Over a mean follow-up of 4.3 years, the study reported “time to progression and overall survival at 3 years were 83% vs. 56% and 87% vs. 64% in patients with PET-NEG and PET-POS scans, respectively.”

These findings aren’t surprising, Dr. Yang said. But “the PET-positive patients who got radiation actually had outcomes that came close to the outcomes that the PET-negative patients were able to achieve.” Their 3-year overall survival was 80% vs. 87% in the PET-negative, no-radiation group vs. 44% in the PET-positive, no-radiation group.

Dr. Yang cautioned, however, that withholding radiation in PET-negative patients isn’t right for everyone: “This doesn’t mean this should be the approach for every single patient.”

What about early-stage DLBCL? In patients without risk factors, Dr. Yang recommends PET scans after four treatments with R-CHOP. “Getting that end-of-treatment PET is going to be super-critical because that’s going to help guide you in terms of the patients who you may feel comfortable omitting radiation versus the patients who remain PET-positive at the end of chemotherapy. Many places will also add an interim PET as well.”

According to her, radiotherapy is appropriate in patients who are PET-positive, based on the findings of the FLYER and LYSA-GOELAMS 02-03 trials.

In early-stage patients who have risk factors such as advanced age or bulky or extra-nodal disease, Dr. Yang suggests examining interim PET scans after three treatments with R-CHOP. If they are negative, another R-CHOP treatment is appropriate – with or without radiotherapy.

“There’s a lot that goes into that decision. The first thing I think about in patients who have risk factors is: What salvage options are available for my patient? Can they tolerate these salvage option? If they’re older, they might not be eligible for auto [autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation]. If they’re frail, they might not be eligible for auto or CAR T cells. If they have bulk, it’s certainly an area of concern. It seems like radiation does help control disease in areas of bulk for patients with DLBCL.”

If these patients are PET-positive, go directly to radiotherapy, Dr. Yang advised. Trials that support this approach include S1001, LYSA-GOELAMS 02-03, and RICOVER-noRTH, she said.

What about double-hit and triple-hit lymphomas, which are especially aggressive due to genetic variations? Research suggests that “even if double hit/triple hit is not responding to chemo, it still responds to radiation,” Dr. Yang said.

In regard to advanced-stage disease, “if patients are receiving full-dose chemo for least six cycles, I use that end-of-treatment PET to help guide me. And then I make an individualized decision based on how bulky that disease is, where the location is, how morbid a relapse would be. If they’re older or receiving reduced-dose chemotherapy, then I’ll more seriously consider radiation just because there are limited options for these patients. And we know that DLCBL is most commonly a disease of the elderly.”

In an adjoining presentation at ASTRO, Andrea Ng, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School/Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, Boston, discussed which patients with incomplete response or refractory/relapsed DLCBL can benefit from radiotherapy.

She highlighted patients with good partial response and end-of-treatment PET-positive with evidence of residual 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose activity via PET scan (Deauville 4/5) – a group that “we’re increasingly seeing.” In these patients, “radiation can be quite effective” at doses of 36-45 Gy. She highlighted a study from 2011 that linked consolidation radiotherapy to 5-year event-free survival in 65% of patients.

As for relapsed/refractory disease in patients who aren’t candidates for further systemic therapy – the “frail without good options” – Dr. Ng said data about salvage radiotherapy is limited. However, a 2015 study tracked 65 patients who were treated with a median dose of 40 Gy with “curative” intent. Local control was “not great” at 72% at 2 years, Dr. Ng said, while overall survival was 60% and progress-free survival was 46%.

Dr. Ng, who was one of this study’s authors, said several groups did better: Those with refractory vs. relapsed disease and those who were responsive to chemotherapy vs. those who were not.

She also highlighted a similar 2019 study of 32 patients with refractory/relapsed disease treated with salvage radiotherapy (median dose of 42.7 Gy) found that 61.8% reached progress-free survival at 5 years – a better outcome.

Dr. Yang has no disclosures. Dr. Ng discloses royalties from UpToDate and Elsevier.

FROM ASTRO 2023

Survival on the upswing in myeloma

Back then, the treatments for MM were chemotherapy and steroids. Stem-cell transplants were on the horizon, as was a most unexpected therapy: the infamous drug thalidomide.

But in the wake of the rib facture, the health of Stanley Katz, MD, worsened and he died after 25 weeks, Dr. Berenson recalled in an interview. At that time, Dr. Katz’s horrifically shortened lifespan following diagnosis was not unusual.

About 4 decades later, hematologists like Dr. Berenson are heralding a new era in MM, a sharp reversal of the previous eras of grim prognoses.

In a new study, Dr. Berenson tracked 161 patients with MM treated at his West Hollywood, Calif., private clinic from 2006 to 2023 and found that their median survival was 136.2 months – more than 11 years. “The OS reported in this study ... is the longest reported to date in an unselected, newly diagnosed MM population,” the study authors write.

Dr. Berenson’s patients are unique: They’re largely White, and they didn’t undergo stem-cell transplants. But other recent studies also suggest that lifespans of more than 10 years are increasingly possible after MM diagnosis. Former TV news anchor Tom Brokaw, for one, has reached that point.

In fact, a pair of other hematologists say the overall survival in Dr. Berenson’s report is hardly out of the question. And, they say, patients diagnosed today could potentially live even longer, because treatments continue to improve.

“With data that’s 10 years old, we expect the median overall survival to be 10 years,” hematologist Sagar Lonial, MD, who’s been tracking survival data in MM, said in an interview. “When patients ask about my outlook, I say it’s a constantly evolving field. Things are changing fast enough that I use 10 years as a floor.”

Dr. Lonial is chair of the department of hematology and medical oncology and chief medical officer at Emory University, Atlanta, Winship Cancer Institute.

Hematologist Rafael Fonseca, MD, chief innovation officer at Mayo Clinic–Arizona, put it this way in an interview: Dr. Berenson’s results “are probably in sync with what we would anticipate with similar cohorts of patients. The reality is that we’ve seen a huge improvement in the life expectancy of patients who were diagnosed with multiple myeloma. It’s not unusual to see patients in the clinic now that are 15 or 20 years out from their diagnosis.”

According to Yale Medicine, MM accounts for 10% of blood cancers and 1%-2% of all cancers and is more common in men vs. women and Blacks vs. Whites. It’s most frequently diagnosed between the ages of 65 and 74, according to the National Cancer Institute, and the median age at diagnosis is 69.

Among the most famous American people currently battling MM are newsman Mr. Brokaw, the former NBC News anchor, and Republican Congressman Steve Scalise, majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives and a candidate for House speaker.

Mr. Brokaw was diagnosed in 2013 while in his early 70s and has talked about his intense struggle with the disease: the infections, operations, infusions, and daily regimens of 24 pills.

“I didn’t want to be Tom Brokaw, cancer victim,” he said in 2018 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. But he opened up about his illness, and became “the multiple myeloma poster boy.”

Rep. Scalise, who’s in his late 50s, is undergoing chemotherapy. He survived being gravely wounded in an assassination attempt in 2017.

Dr. Berenson’s new study, published in Targeted Oncology, tracked 161 patients (89 women, 72 men; median age, 65.4; 125 White, 3 Black, 10 Hispanic, 15 Asian, and 8 multi-ethnic).

All started frontline treatment at Dr. Berenson’s clinic and were included if they could read consent forms and gave permission for blood draws. None underwent stem-cell transplants as part of initial therapy. Another 1,036 patients had been treated elsewhere and were not included in the study.

Over a median of 42.7 months (range, 1.9-195.1), the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 97.5%, 85.3%, and 76.2%, respectively.

The study claims “these results are considerably better than those reported from patients enrolled in clinical trials and those from countries with national registries.”

In the interview, Dr. Berenson said the study is unique because it’s not limited like many studies to younger, healthier patients. Nor does it include those treated at other facilities, he said.

The study is unusual in other ways. Dr. Berenson said his drug regimens aren’t necessarily standard, and he doesn’t treat patients with stem-cell transplants. “I stopped transplanting in about 2000 because clearly it was not improving the length of life,” he said.

Dr. Berenson said colleagues can learn from his insistence on sensitively treating the quality of life of patients, his embrace of clinical trials with novel combinations, and his close monitoring of myeloma proteins to gauge whether patients need to rapidly switch therapies.

He noted that his drug regimens are typically off-label and vary by patient. “We’re not using as high doses of drugs like Velcade [bortezomib] or Revlimid [lenalidomide] as my colleagues. We’re not necessarily giving as many doses. Also, we’re not adding as many drugs in many cases as they are. We’re taking it slower.”

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends bortezomib and lenalidomide as standard induction treatments in patients with MM who are candidates for stem-cell transplantation, a procedure it considers the “preferred approach in transplant-eligible patients.”

There are limitations to Dr. Berenson’s new study. The patients aren’t representative of people with MM as a whole: His cohort is overwhelmingly White (78%) and just 2% Black, while an estimated one-fifth of patients with MM in the United States are Black and have poorer outcomes.

Dr. Berenson also acknowledged that his patients are most likely a wealthier group, although he said it’s not feasible to ask them about income. The study provides no information about socioeconomics.

Dr. Lonial said survival of 10-11 years is fairly typical in MM, with standard-risk patients reaching 14 years.

He highlighted a 2021 Canadian study that tracked 3,030 patients with newly diagnosed MM from 2007 to 2018 (average age, 64; 58.6% men). Those who received an upfront autologous stem-cell transplant had a median overall survival of 122.0 months (95% confidence interval, 115.0-135.0 months) vs. 54.3 months (95% CI, 50.8-58.8 months) for those who didn’t get the transplants. Not surprisingly, survival dipped with each subsequent treatment regimen.

Dr. Lonial is coauthor of a 2020 study that tracked 1,000 consecutive patients (mean age, 61; 35.2% Black) with newly diagnosed myeloma who were treated with RVD (lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone) induction therapy from 2007 to 2016. The median overall survival was 126.6 months (95% CI, 113.3-139.8 months).

Dr. Fonseca noted that the news about MM survival rates is not entirely positive. Patients with high-risk disease often die early on in their disease course, he said.

Research suggests even the youngest patients with MM may die within years of diagnosis. A 2021 French study tracked 214 patients in the 18-40 age group for 15 years (2000-2015). At 5 years, “relative survival compared with same age- and sex-matched individuals was 83.5%,” and estimated overall survival was 14.5 years.

Still, a “very, very fertile environment for the development of drugs” has made a huge difference, Dr. Fonseca said. “We’ve had about 19 FDA approvals in the last 15 or 20 years.”

He urged colleagues to keep in mind that survival drops as patients decline in a line of therapy and need to switch to another one. “It might make intuitive sense to say ‘I’m gonna save something for later. I want to keep my powder dry.’ But put your best foot forward. Always go with your best treatments first.”

This approach can play out in a decision, say, to start with a four-drug initial regimen instead of a weaker two-drug regimen, he said. “Be mindful of managing toxicities, but hit harder.”

As he noted, side effects were worse with older generations of drugs. In regard to cost, multidrug treatments can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Dr. Fonseca said insurance tends to cover drugs that are approved by guidelines.

Dr. Fonseca discloses relationships with AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Binding Site, BMS (Celgene), Millennium Takeda, Janssen, Juno, Kite, Merck, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Regeneron, Sanofi, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Caris Life Sciences, Oncotracker, Antegene, and AZBio, and a patent in MM. Dr. Berenson discloses ties with Janssen, Amgen, Sanofi, BMS, Karyopharm, and Incyte. Dr. Lonial reports ties with TG Therapeutics, Celgene, BMS, Janssen, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, Takeda, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Novartis.

Back then, the treatments for MM were chemotherapy and steroids. Stem-cell transplants were on the horizon, as was a most unexpected therapy: the infamous drug thalidomide.

But in the wake of the rib facture, the health of Stanley Katz, MD, worsened and he died after 25 weeks, Dr. Berenson recalled in an interview. At that time, Dr. Katz’s horrifically shortened lifespan following diagnosis was not unusual.

About 4 decades later, hematologists like Dr. Berenson are heralding a new era in MM, a sharp reversal of the previous eras of grim prognoses.

In a new study, Dr. Berenson tracked 161 patients with MM treated at his West Hollywood, Calif., private clinic from 2006 to 2023 and found that their median survival was 136.2 months – more than 11 years. “The OS reported in this study ... is the longest reported to date in an unselected, newly diagnosed MM population,” the study authors write.

Dr. Berenson’s patients are unique: They’re largely White, and they didn’t undergo stem-cell transplants. But other recent studies also suggest that lifespans of more than 10 years are increasingly possible after MM diagnosis. Former TV news anchor Tom Brokaw, for one, has reached that point.

In fact, a pair of other hematologists say the overall survival in Dr. Berenson’s report is hardly out of the question. And, they say, patients diagnosed today could potentially live even longer, because treatments continue to improve.

“With data that’s 10 years old, we expect the median overall survival to be 10 years,” hematologist Sagar Lonial, MD, who’s been tracking survival data in MM, said in an interview. “When patients ask about my outlook, I say it’s a constantly evolving field. Things are changing fast enough that I use 10 years as a floor.”

Dr. Lonial is chair of the department of hematology and medical oncology and chief medical officer at Emory University, Atlanta, Winship Cancer Institute.

Hematologist Rafael Fonseca, MD, chief innovation officer at Mayo Clinic–Arizona, put it this way in an interview: Dr. Berenson’s results “are probably in sync with what we would anticipate with similar cohorts of patients. The reality is that we’ve seen a huge improvement in the life expectancy of patients who were diagnosed with multiple myeloma. It’s not unusual to see patients in the clinic now that are 15 or 20 years out from their diagnosis.”

According to Yale Medicine, MM accounts for 10% of blood cancers and 1%-2% of all cancers and is more common in men vs. women and Blacks vs. Whites. It’s most frequently diagnosed between the ages of 65 and 74, according to the National Cancer Institute, and the median age at diagnosis is 69.

Among the most famous American people currently battling MM are newsman Mr. Brokaw, the former NBC News anchor, and Republican Congressman Steve Scalise, majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives and a candidate for House speaker.

Mr. Brokaw was diagnosed in 2013 while in his early 70s and has talked about his intense struggle with the disease: the infections, operations, infusions, and daily regimens of 24 pills.

“I didn’t want to be Tom Brokaw, cancer victim,” he said in 2018 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. But he opened up about his illness, and became “the multiple myeloma poster boy.”

Rep. Scalise, who’s in his late 50s, is undergoing chemotherapy. He survived being gravely wounded in an assassination attempt in 2017.

Dr. Berenson’s new study, published in Targeted Oncology, tracked 161 patients (89 women, 72 men; median age, 65.4; 125 White, 3 Black, 10 Hispanic, 15 Asian, and 8 multi-ethnic).

All started frontline treatment at Dr. Berenson’s clinic and were included if they could read consent forms and gave permission for blood draws. None underwent stem-cell transplants as part of initial therapy. Another 1,036 patients had been treated elsewhere and were not included in the study.

Over a median of 42.7 months (range, 1.9-195.1), the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 97.5%, 85.3%, and 76.2%, respectively.

The study claims “these results are considerably better than those reported from patients enrolled in clinical trials and those from countries with national registries.”

In the interview, Dr. Berenson said the study is unique because it’s not limited like many studies to younger, healthier patients. Nor does it include those treated at other facilities, he said.

The study is unusual in other ways. Dr. Berenson said his drug regimens aren’t necessarily standard, and he doesn’t treat patients with stem-cell transplants. “I stopped transplanting in about 2000 because clearly it was not improving the length of life,” he said.

Dr. Berenson said colleagues can learn from his insistence on sensitively treating the quality of life of patients, his embrace of clinical trials with novel combinations, and his close monitoring of myeloma proteins to gauge whether patients need to rapidly switch therapies.

He noted that his drug regimens are typically off-label and vary by patient. “We’re not using as high doses of drugs like Velcade [bortezomib] or Revlimid [lenalidomide] as my colleagues. We’re not necessarily giving as many doses. Also, we’re not adding as many drugs in many cases as they are. We’re taking it slower.”

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends bortezomib and lenalidomide as standard induction treatments in patients with MM who are candidates for stem-cell transplantation, a procedure it considers the “preferred approach in transplant-eligible patients.”

There are limitations to Dr. Berenson’s new study. The patients aren’t representative of people with MM as a whole: His cohort is overwhelmingly White (78%) and just 2% Black, while an estimated one-fifth of patients with MM in the United States are Black and have poorer outcomes.

Dr. Berenson also acknowledged that his patients are most likely a wealthier group, although he said it’s not feasible to ask them about income. The study provides no information about socioeconomics.

Dr. Lonial said survival of 10-11 years is fairly typical in MM, with standard-risk patients reaching 14 years.

He highlighted a 2021 Canadian study that tracked 3,030 patients with newly diagnosed MM from 2007 to 2018 (average age, 64; 58.6% men). Those who received an upfront autologous stem-cell transplant had a median overall survival of 122.0 months (95% confidence interval, 115.0-135.0 months) vs. 54.3 months (95% CI, 50.8-58.8 months) for those who didn’t get the transplants. Not surprisingly, survival dipped with each subsequent treatment regimen.

Dr. Lonial is coauthor of a 2020 study that tracked 1,000 consecutive patients (mean age, 61; 35.2% Black) with newly diagnosed myeloma who were treated with RVD (lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone) induction therapy from 2007 to 2016. The median overall survival was 126.6 months (95% CI, 113.3-139.8 months).

Dr. Fonseca noted that the news about MM survival rates is not entirely positive. Patients with high-risk disease often die early on in their disease course, he said.

Research suggests even the youngest patients with MM may die within years of diagnosis. A 2021 French study tracked 214 patients in the 18-40 age group for 15 years (2000-2015). At 5 years, “relative survival compared with same age- and sex-matched individuals was 83.5%,” and estimated overall survival was 14.5 years.

Still, a “very, very fertile environment for the development of drugs” has made a huge difference, Dr. Fonseca said. “We’ve had about 19 FDA approvals in the last 15 or 20 years.”

He urged colleagues to keep in mind that survival drops as patients decline in a line of therapy and need to switch to another one. “It might make intuitive sense to say ‘I’m gonna save something for later. I want to keep my powder dry.’ But put your best foot forward. Always go with your best treatments first.”

This approach can play out in a decision, say, to start with a four-drug initial regimen instead of a weaker two-drug regimen, he said. “Be mindful of managing toxicities, but hit harder.”

As he noted, side effects were worse with older generations of drugs. In regard to cost, multidrug treatments can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Dr. Fonseca said insurance tends to cover drugs that are approved by guidelines.

Dr. Fonseca discloses relationships with AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Binding Site, BMS (Celgene), Millennium Takeda, Janssen, Juno, Kite, Merck, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Regeneron, Sanofi, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Caris Life Sciences, Oncotracker, Antegene, and AZBio, and a patent in MM. Dr. Berenson discloses ties with Janssen, Amgen, Sanofi, BMS, Karyopharm, and Incyte. Dr. Lonial reports ties with TG Therapeutics, Celgene, BMS, Janssen, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, Takeda, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Novartis.

Back then, the treatments for MM were chemotherapy and steroids. Stem-cell transplants were on the horizon, as was a most unexpected therapy: the infamous drug thalidomide.

But in the wake of the rib facture, the health of Stanley Katz, MD, worsened and he died after 25 weeks, Dr. Berenson recalled in an interview. At that time, Dr. Katz’s horrifically shortened lifespan following diagnosis was not unusual.

About 4 decades later, hematologists like Dr. Berenson are heralding a new era in MM, a sharp reversal of the previous eras of grim prognoses.

In a new study, Dr. Berenson tracked 161 patients with MM treated at his West Hollywood, Calif., private clinic from 2006 to 2023 and found that their median survival was 136.2 months – more than 11 years. “The OS reported in this study ... is the longest reported to date in an unselected, newly diagnosed MM population,” the study authors write.

Dr. Berenson’s patients are unique: They’re largely White, and they didn’t undergo stem-cell transplants. But other recent studies also suggest that lifespans of more than 10 years are increasingly possible after MM diagnosis. Former TV news anchor Tom Brokaw, for one, has reached that point.

In fact, a pair of other hematologists say the overall survival in Dr. Berenson’s report is hardly out of the question. And, they say, patients diagnosed today could potentially live even longer, because treatments continue to improve.

“With data that’s 10 years old, we expect the median overall survival to be 10 years,” hematologist Sagar Lonial, MD, who’s been tracking survival data in MM, said in an interview. “When patients ask about my outlook, I say it’s a constantly evolving field. Things are changing fast enough that I use 10 years as a floor.”

Dr. Lonial is chair of the department of hematology and medical oncology and chief medical officer at Emory University, Atlanta, Winship Cancer Institute.

Hematologist Rafael Fonseca, MD, chief innovation officer at Mayo Clinic–Arizona, put it this way in an interview: Dr. Berenson’s results “are probably in sync with what we would anticipate with similar cohorts of patients. The reality is that we’ve seen a huge improvement in the life expectancy of patients who were diagnosed with multiple myeloma. It’s not unusual to see patients in the clinic now that are 15 or 20 years out from their diagnosis.”

According to Yale Medicine, MM accounts for 10% of blood cancers and 1%-2% of all cancers and is more common in men vs. women and Blacks vs. Whites. It’s most frequently diagnosed between the ages of 65 and 74, according to the National Cancer Institute, and the median age at diagnosis is 69.

Among the most famous American people currently battling MM are newsman Mr. Brokaw, the former NBC News anchor, and Republican Congressman Steve Scalise, majority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives and a candidate for House speaker.

Mr. Brokaw was diagnosed in 2013 while in his early 70s and has talked about his intense struggle with the disease: the infections, operations, infusions, and daily regimens of 24 pills.

“I didn’t want to be Tom Brokaw, cancer victim,” he said in 2018 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. But he opened up about his illness, and became “the multiple myeloma poster boy.”

Rep. Scalise, who’s in his late 50s, is undergoing chemotherapy. He survived being gravely wounded in an assassination attempt in 2017.

Dr. Berenson’s new study, published in Targeted Oncology, tracked 161 patients (89 women, 72 men; median age, 65.4; 125 White, 3 Black, 10 Hispanic, 15 Asian, and 8 multi-ethnic).

All started frontline treatment at Dr. Berenson’s clinic and were included if they could read consent forms and gave permission for blood draws. None underwent stem-cell transplants as part of initial therapy. Another 1,036 patients had been treated elsewhere and were not included in the study.

Over a median of 42.7 months (range, 1.9-195.1), the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 97.5%, 85.3%, and 76.2%, respectively.

The study claims “these results are considerably better than those reported from patients enrolled in clinical trials and those from countries with national registries.”

In the interview, Dr. Berenson said the study is unique because it’s not limited like many studies to younger, healthier patients. Nor does it include those treated at other facilities, he said.

The study is unusual in other ways. Dr. Berenson said his drug regimens aren’t necessarily standard, and he doesn’t treat patients with stem-cell transplants. “I stopped transplanting in about 2000 because clearly it was not improving the length of life,” he said.

Dr. Berenson said colleagues can learn from his insistence on sensitively treating the quality of life of patients, his embrace of clinical trials with novel combinations, and his close monitoring of myeloma proteins to gauge whether patients need to rapidly switch therapies.

He noted that his drug regimens are typically off-label and vary by patient. “We’re not using as high doses of drugs like Velcade [bortezomib] or Revlimid [lenalidomide] as my colleagues. We’re not necessarily giving as many doses. Also, we’re not adding as many drugs in many cases as they are. We’re taking it slower.”

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends bortezomib and lenalidomide as standard induction treatments in patients with MM who are candidates for stem-cell transplantation, a procedure it considers the “preferred approach in transplant-eligible patients.”

There are limitations to Dr. Berenson’s new study. The patients aren’t representative of people with MM as a whole: His cohort is overwhelmingly White (78%) and just 2% Black, while an estimated one-fifth of patients with MM in the United States are Black and have poorer outcomes.

Dr. Berenson also acknowledged that his patients are most likely a wealthier group, although he said it’s not feasible to ask them about income. The study provides no information about socioeconomics.

Dr. Lonial said survival of 10-11 years is fairly typical in MM, with standard-risk patients reaching 14 years.

He highlighted a 2021 Canadian study that tracked 3,030 patients with newly diagnosed MM from 2007 to 2018 (average age, 64; 58.6% men). Those who received an upfront autologous stem-cell transplant had a median overall survival of 122.0 months (95% confidence interval, 115.0-135.0 months) vs. 54.3 months (95% CI, 50.8-58.8 months) for those who didn’t get the transplants. Not surprisingly, survival dipped with each subsequent treatment regimen.

Dr. Lonial is coauthor of a 2020 study that tracked 1,000 consecutive patients (mean age, 61; 35.2% Black) with newly diagnosed myeloma who were treated with RVD (lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone) induction therapy from 2007 to 2016. The median overall survival was 126.6 months (95% CI, 113.3-139.8 months).

Dr. Fonseca noted that the news about MM survival rates is not entirely positive. Patients with high-risk disease often die early on in their disease course, he said.

Research suggests even the youngest patients with MM may die within years of diagnosis. A 2021 French study tracked 214 patients in the 18-40 age group for 15 years (2000-2015). At 5 years, “relative survival compared with same age- and sex-matched individuals was 83.5%,” and estimated overall survival was 14.5 years.

Still, a “very, very fertile environment for the development of drugs” has made a huge difference, Dr. Fonseca said. “We’ve had about 19 FDA approvals in the last 15 or 20 years.”

He urged colleagues to keep in mind that survival drops as patients decline in a line of therapy and need to switch to another one. “It might make intuitive sense to say ‘I’m gonna save something for later. I want to keep my powder dry.’ But put your best foot forward. Always go with your best treatments first.”

This approach can play out in a decision, say, to start with a four-drug initial regimen instead of a weaker two-drug regimen, he said. “Be mindful of managing toxicities, but hit harder.”

As he noted, side effects were worse with older generations of drugs. In regard to cost, multidrug treatments can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Dr. Fonseca said insurance tends to cover drugs that are approved by guidelines.

Dr. Fonseca discloses relationships with AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Binding Site, BMS (Celgene), Millennium Takeda, Janssen, Juno, Kite, Merck, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Regeneron, Sanofi, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Caris Life Sciences, Oncotracker, Antegene, and AZBio, and a patent in MM. Dr. Berenson discloses ties with Janssen, Amgen, Sanofi, BMS, Karyopharm, and Incyte. Dr. Lonial reports ties with TG Therapeutics, Celgene, BMS, Janssen, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, Takeda, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Novartis.

MOC opposition continues to gain momentum as ASH weighs in

ASH president Robert A. Brodsky, MD, sent a letter to ABIM’s President and Chief Executive Officer Richard Baron, MD, highlighting hematologists’ concerns about the MOC process and outlining immediate actions ABIM should take.

“ASH continues to support the importance of lifelong learning for hematologists via a program that is evidence-based, relevant to one’s practice, and transparent; however, these three basic requirements are not met by the current ABIM MOC program,” Dr. Brodsky stated in the Sept. 27 letter to Baron.

Dr. Brodsky highlighted, for instance, the fact that the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment – the alternative to the 10-year exam – “does not reflect real life practice, nor does it target each individual’s scope of practice.” Dr. Brodsky added that, according to members of ASH, the assessment is also “creating high levels of stress and contributing to burnout.”

The letter from Dr. Brodsky urged ABIM to “establish a new MOC program” that does not involve high-stakes assessments, reduces the number of Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment questions physicians receive, and eliminates redundancy between the MOC requirement to have a current license and the requirement to report continued medical education to ABIM.

The ABIM shared a copy of the letter in a Sept. 28 blog post defending the MOC process, highlighting past collaboration with ASH that “has led to meaningful enhancements to the [MOC] program” and committing to “continue to listen to and learn from the physician community going forward.”

The recent backlash against the MOC process stemmed from a petition demanding an end to the MOC. The petition was launched in July by hematologist-oncologist Aaron Goodman, MD, from the University of California, San Diego, who has been a vocal critic of the MOC process.

The criticism largely centered around the high costs and the “complex and time-consuming process that poses significant challenges to practicing physicians,” Dr. Goodman wrote in the petition, which has garnered more than 20,700 signatures.

In August, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) published “SCAI Position on ABIM Revocation of Certification for Not Participating in MOC.” The Electrophysiology Advocacy Foundation and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) issued statements pushing back on the MOC as well.

On Sept. 21, the SCAI, HRS, American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Failure Society of America went a step further and announced plans to create a new certification process that is independent of the ABIM MOC system.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) is now also surveying members about their MOC experience. A Sept. 26 announcement encouraged recipients to check their inboxes for a link to an anonymous MOC Experience Questionnaire before Oct. 12 and thanked respondents for their “engagement as ASCO works to address this critical issue for the oncology community.”

After ASH sent its letter to ABIM, Dr. Goodman applauded the society’s stance in a post on his X (formerly Twitter) account. Vincent Rajkumar, MD, a hematologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., commented on ABIM’s response to ASH’s letter via X, noting, “If I were @ASH_hematology leadership, I would take ABIM response as disrespectful. A hasty response within a day is not a sign of good faith.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ASH president Robert A. Brodsky, MD, sent a letter to ABIM’s President and Chief Executive Officer Richard Baron, MD, highlighting hematologists’ concerns about the MOC process and outlining immediate actions ABIM should take.

“ASH continues to support the importance of lifelong learning for hematologists via a program that is evidence-based, relevant to one’s practice, and transparent; however, these three basic requirements are not met by the current ABIM MOC program,” Dr. Brodsky stated in the Sept. 27 letter to Baron.

Dr. Brodsky highlighted, for instance, the fact that the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment – the alternative to the 10-year exam – “does not reflect real life practice, nor does it target each individual’s scope of practice.” Dr. Brodsky added that, according to members of ASH, the assessment is also “creating high levels of stress and contributing to burnout.”

The letter from Dr. Brodsky urged ABIM to “establish a new MOC program” that does not involve high-stakes assessments, reduces the number of Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment questions physicians receive, and eliminates redundancy between the MOC requirement to have a current license and the requirement to report continued medical education to ABIM.

The ABIM shared a copy of the letter in a Sept. 28 blog post defending the MOC process, highlighting past collaboration with ASH that “has led to meaningful enhancements to the [MOC] program” and committing to “continue to listen to and learn from the physician community going forward.”

The recent backlash against the MOC process stemmed from a petition demanding an end to the MOC. The petition was launched in July by hematologist-oncologist Aaron Goodman, MD, from the University of California, San Diego, who has been a vocal critic of the MOC process.

The criticism largely centered around the high costs and the “complex and time-consuming process that poses significant challenges to practicing physicians,” Dr. Goodman wrote in the petition, which has garnered more than 20,700 signatures.

In August, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) published “SCAI Position on ABIM Revocation of Certification for Not Participating in MOC.” The Electrophysiology Advocacy Foundation and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) issued statements pushing back on the MOC as well.

On Sept. 21, the SCAI, HRS, American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Failure Society of America went a step further and announced plans to create a new certification process that is independent of the ABIM MOC system.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) is now also surveying members about their MOC experience. A Sept. 26 announcement encouraged recipients to check their inboxes for a link to an anonymous MOC Experience Questionnaire before Oct. 12 and thanked respondents for their “engagement as ASCO works to address this critical issue for the oncology community.”

After ASH sent its letter to ABIM, Dr. Goodman applauded the society’s stance in a post on his X (formerly Twitter) account. Vincent Rajkumar, MD, a hematologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., commented on ABIM’s response to ASH’s letter via X, noting, “If I were @ASH_hematology leadership, I would take ABIM response as disrespectful. A hasty response within a day is not a sign of good faith.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ASH president Robert A. Brodsky, MD, sent a letter to ABIM’s President and Chief Executive Officer Richard Baron, MD, highlighting hematologists’ concerns about the MOC process and outlining immediate actions ABIM should take.

“ASH continues to support the importance of lifelong learning for hematologists via a program that is evidence-based, relevant to one’s practice, and transparent; however, these three basic requirements are not met by the current ABIM MOC program,” Dr. Brodsky stated in the Sept. 27 letter to Baron.

Dr. Brodsky highlighted, for instance, the fact that the Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment – the alternative to the 10-year exam – “does not reflect real life practice, nor does it target each individual’s scope of practice.” Dr. Brodsky added that, according to members of ASH, the assessment is also “creating high levels of stress and contributing to burnout.”

The letter from Dr. Brodsky urged ABIM to “establish a new MOC program” that does not involve high-stakes assessments, reduces the number of Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment questions physicians receive, and eliminates redundancy between the MOC requirement to have a current license and the requirement to report continued medical education to ABIM.

The ABIM shared a copy of the letter in a Sept. 28 blog post defending the MOC process, highlighting past collaboration with ASH that “has led to meaningful enhancements to the [MOC] program” and committing to “continue to listen to and learn from the physician community going forward.”

The recent backlash against the MOC process stemmed from a petition demanding an end to the MOC. The petition was launched in July by hematologist-oncologist Aaron Goodman, MD, from the University of California, San Diego, who has been a vocal critic of the MOC process.

The criticism largely centered around the high costs and the “complex and time-consuming process that poses significant challenges to practicing physicians,” Dr. Goodman wrote in the petition, which has garnered more than 20,700 signatures.

In August, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) published “SCAI Position on ABIM Revocation of Certification for Not Participating in MOC.” The Electrophysiology Advocacy Foundation and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) issued statements pushing back on the MOC as well.

On Sept. 21, the SCAI, HRS, American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Failure Society of America went a step further and announced plans to create a new certification process that is independent of the ABIM MOC system.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) is now also surveying members about their MOC experience. A Sept. 26 announcement encouraged recipients to check their inboxes for a link to an anonymous MOC Experience Questionnaire before Oct. 12 and thanked respondents for their “engagement as ASCO works to address this critical issue for the oncology community.”

After ASH sent its letter to ABIM, Dr. Goodman applauded the society’s stance in a post on his X (formerly Twitter) account. Vincent Rajkumar, MD, a hematologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., commented on ABIM’s response to ASH’s letter via X, noting, “If I were @ASH_hematology leadership, I would take ABIM response as disrespectful. A hasty response within a day is not a sign of good faith.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

These adverse events linked to improved cancer prognosis

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Emerging evidence suggests that the presence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events may be linked with favorable outcomes among patients with cancer who receive ICIs.

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 23 studies and a total of 22,749 patients with cancer who received ICI treatment; studies compared outcomes among patients with and those without cutaneous immune-related adverse events.

- The major outcomes evaluated in the analysis were overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS); subgroup analyses assessed cutaneous immune-related adverse event type, cancer type, and other factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- The occurrence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events was associated with improved PFS (hazard ratio, 0.52; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 0.61; P < .001).

- In the subgroup analysis, patients with eczematous (HR, 0.69), lichenoid or lichen planus–like skin lesions (HR, 0.51), pruritus without rash (HR, 0.70), psoriasis (HR, 0.63), or vitiligo (HR, 0.30) demonstrated a significant overall survival advantage. Vitiligo was the only adverse event associated with a PFS advantage (HR, 0.28).

- Among patients with melanoma, analyses revealed a significant association between the incidence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events and improved overall survival (HR, 0.51) and PFS (HR, 0.45). The authors highlighted similar findings among patients with non–small cell lung cancer (HR, 0.50 for overall survival and 0.61 for PFS).

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that [cutaneous immune-related adverse events] may have useful prognostic value in ICI treatment,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The analysis, led by Fei Wang, MD, Zhong Da Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Most of the data came from retrospective studies, and there were limited data on specific patient subgroups. The Egger tests, used to assess potential publication bias in meta-analyses, revealed publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. The study was supported by a grant from the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Emerging evidence suggests that the presence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events may be linked with favorable outcomes among patients with cancer who receive ICIs.

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 23 studies and a total of 22,749 patients with cancer who received ICI treatment; studies compared outcomes among patients with and those without cutaneous immune-related adverse events.

- The major outcomes evaluated in the analysis were overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS); subgroup analyses assessed cutaneous immune-related adverse event type, cancer type, and other factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- The occurrence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events was associated with improved PFS (hazard ratio, 0.52; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 0.61; P < .001).

- In the subgroup analysis, patients with eczematous (HR, 0.69), lichenoid or lichen planus–like skin lesions (HR, 0.51), pruritus without rash (HR, 0.70), psoriasis (HR, 0.63), or vitiligo (HR, 0.30) demonstrated a significant overall survival advantage. Vitiligo was the only adverse event associated with a PFS advantage (HR, 0.28).

- Among patients with melanoma, analyses revealed a significant association between the incidence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events and improved overall survival (HR, 0.51) and PFS (HR, 0.45). The authors highlighted similar findings among patients with non–small cell lung cancer (HR, 0.50 for overall survival and 0.61 for PFS).

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that [cutaneous immune-related adverse events] may have useful prognostic value in ICI treatment,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The analysis, led by Fei Wang, MD, Zhong Da Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Most of the data came from retrospective studies, and there were limited data on specific patient subgroups. The Egger tests, used to assess potential publication bias in meta-analyses, revealed publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. The study was supported by a grant from the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- Emerging evidence suggests that the presence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events may be linked with favorable outcomes among patients with cancer who receive ICIs.

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 23 studies and a total of 22,749 patients with cancer who received ICI treatment; studies compared outcomes among patients with and those without cutaneous immune-related adverse events.

- The major outcomes evaluated in the analysis were overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS); subgroup analyses assessed cutaneous immune-related adverse event type, cancer type, and other factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- The occurrence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events was associated with improved PFS (hazard ratio, 0.52; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 0.61; P < .001).

- In the subgroup analysis, patients with eczematous (HR, 0.69), lichenoid or lichen planus–like skin lesions (HR, 0.51), pruritus without rash (HR, 0.70), psoriasis (HR, 0.63), or vitiligo (HR, 0.30) demonstrated a significant overall survival advantage. Vitiligo was the only adverse event associated with a PFS advantage (HR, 0.28).

- Among patients with melanoma, analyses revealed a significant association between the incidence of cutaneous immune-related adverse events and improved overall survival (HR, 0.51) and PFS (HR, 0.45). The authors highlighted similar findings among patients with non–small cell lung cancer (HR, 0.50 for overall survival and 0.61 for PFS).

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that [cutaneous immune-related adverse events] may have useful prognostic value in ICI treatment,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The analysis, led by Fei Wang, MD, Zhong Da Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Most of the data came from retrospective studies, and there were limited data on specific patient subgroups. The Egger tests, used to assess potential publication bias in meta-analyses, revealed publication bias.

DISCLOSURES:

No disclosures were reported. The study was supported by a grant from the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves bosutinib for children with CML

The agency also approved new 50-mg and 100-mg capsules to help treat children.

For newly diagnosed disease, the dose is 300 mg/m2 once daily with food. For resistant/intolerant disease, the dose is 400 mg/m2 once daily. For children who cannot swallow capsules, the contents can be mixed into applesauce or yogurt, the FDA said in a press release announcing the approval.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) was previously approved for adults. Three other TKIs were previously approved for pediatric CML.

The approval was based on the BCHILD trial, a pediatric dose-finding study involving patients aged 1 year or older. Among the 21 children with newly diagnosed chronic phase, Ph+ CML treated with 300 mg/m2, the rate of major cytogenetic response was 76.2%, the rate of complete cytogenetic response was 71.4%, and the rate of major molecular response rate was 28.6% over a median duration of 14.2 months.

Among the 28 children with relapsed/intolerant disease treated with up to 400 mg/m2, the rate of major cytogenetic response was 82.1%, the rate of complete cytogenetic response was 78.6%, and the rate of major molecular response was 50% over a median duration of 23.2 months. Among the 14 patients who had a major molecular response, two lost it – one after 13.6 months of treatment, and the other after 24.7 months of treatment.

Adverse events that occurred in 20% or more of children included diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, rash, fatigue, hepatic dysfunction, headache, pyrexia, decreased appetite, and constipation. Overall, 45% or more of patients experienced an increase in creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, or aspartate aminotransferase levels, or a decrease in white blood cell count or platelet count.

The full labeling information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency also approved new 50-mg and 100-mg capsules to help treat children.

For newly diagnosed disease, the dose is 300 mg/m2 once daily with food. For resistant/intolerant disease, the dose is 400 mg/m2 once daily. For children who cannot swallow capsules, the contents can be mixed into applesauce or yogurt, the FDA said in a press release announcing the approval.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) was previously approved for adults. Three other TKIs were previously approved for pediatric CML.

The approval was based on the BCHILD trial, a pediatric dose-finding study involving patients aged 1 year or older. Among the 21 children with newly diagnosed chronic phase, Ph+ CML treated with 300 mg/m2, the rate of major cytogenetic response was 76.2%, the rate of complete cytogenetic response was 71.4%, and the rate of major molecular response rate was 28.6% over a median duration of 14.2 months.

Among the 28 children with relapsed/intolerant disease treated with up to 400 mg/m2, the rate of major cytogenetic response was 82.1%, the rate of complete cytogenetic response was 78.6%, and the rate of major molecular response was 50% over a median duration of 23.2 months. Among the 14 patients who had a major molecular response, two lost it – one after 13.6 months of treatment, and the other after 24.7 months of treatment.

Adverse events that occurred in 20% or more of children included diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, rash, fatigue, hepatic dysfunction, headache, pyrexia, decreased appetite, and constipation. Overall, 45% or more of patients experienced an increase in creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, or aspartate aminotransferase levels, or a decrease in white blood cell count or platelet count.

The full labeling information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency also approved new 50-mg and 100-mg capsules to help treat children.

For newly diagnosed disease, the dose is 300 mg/m2 once daily with food. For resistant/intolerant disease, the dose is 400 mg/m2 once daily. For children who cannot swallow capsules, the contents can be mixed into applesauce or yogurt, the FDA said in a press release announcing the approval.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) was previously approved for adults. Three other TKIs were previously approved for pediatric CML.

The approval was based on the BCHILD trial, a pediatric dose-finding study involving patients aged 1 year or older. Among the 21 children with newly diagnosed chronic phase, Ph+ CML treated with 300 mg/m2, the rate of major cytogenetic response was 76.2%, the rate of complete cytogenetic response was 71.4%, and the rate of major molecular response rate was 28.6% over a median duration of 14.2 months.

Among the 28 children with relapsed/intolerant disease treated with up to 400 mg/m2, the rate of major cytogenetic response was 82.1%, the rate of complete cytogenetic response was 78.6%, and the rate of major molecular response was 50% over a median duration of 23.2 months. Among the 14 patients who had a major molecular response, two lost it – one after 13.6 months of treatment, and the other after 24.7 months of treatment.

Adverse events that occurred in 20% or more of children included diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, rash, fatigue, hepatic dysfunction, headache, pyrexia, decreased appetite, and constipation. Overall, 45% or more of patients experienced an increase in creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, or aspartate aminotransferase levels, or a decrease in white blood cell count or platelet count.