User login

As Director for Quality Improvement in an academic department, I frequently remind my colleagues that "quality" is not a 4-letter word. Unfortunately, quality is linked in many physicians’ minds to increasing practice complexity and an alphabet soup of acronyms, such as PQRS (Physician Quality Reporting System), MU (meaningful use), and MOC (Maintenance of Certification), among others. Quality improvement (QI) can and should be driven by a desire to improve patient outcomes, professional satisfaction, and operational efficiency, so how should dermatologists respond?

It is helpful to consider why measures of quality are increasingly tied to payment. Conventional wisdom suggests that the American health care system provides poor value. In 2014, total health care expenditures in the United States were $3.0 trillion ($9523 per person), representing 17.5% of the gross domestic product.1 In 1999, the Institute of Medicine estimated that 44,000 to 98,000 individuals die each year due to hospital-based medical errors.2 Noting poor outcomes and high costs, Berwick et al3 proposed the triple aim of improving the experience of care, improving health of populations, and reducing cost. If health care is too expensive and if quality includes outcomes and safety, then improved value of health care must couple cost reduction to QI. Although the future of health care reform is uncertain, it is reasonable to assume that physicians will be expected to care for more patients with fewer dollars. In that context, maximizing operational efficiency and thus economic viability is key. Our challenge is to remain focused on our patients and to identify opportunities to improve the value of their care, both by reducing costs and improving quality.

Health care systems, however, cannot improve with an unhappy and burned-out workforce. Recent data demonstrate high rates of professional burnout among physicians, including dermatologists.4 Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 propose the quadruple aim, which adds improving physician and staff work-life balance to the elements of the triple aim. Burned-out physicians cannot constructively participate in achieving the goals of the triple aim, and physician and staff satisfaction must be a component of any QI paradigm.

The Institute of Medicine has proposed 6 specific aims for improving health care systems: health care should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.6 These aims, taken together with the quadruple aim, can serve as a foundation for developing QI projects for practices and health systems.

Patient safety is a well-recognized issue in dermatology.7-9 Specimen labeling errors, medication errors, wrong-site surgery, and postprocedure complications are examples of safety issues. Quality improvement directed toward improved professional satisfaction for physicians and staff also is critical. The suggestions offered by Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 are directed to primary care providers but are applicable to many dermatology practices. The American Medical Association’s STEPS Forward initiative provides online tutorials that guide practice improvements aimed at improving professional satisfaction and operational efficiency.10

Patient-centered care need not focus solely on patient satisfaction. Clearly, a physician’s duty is to do what is best for each patient, but patient satisfaction and experience are increasingly common measures of quality. Although evidence suggests that measures of physician-patient communication correlate with patient compliance,11 higher patient satisfaction scores may also correlate with higher cost and increased mortality.12 A practice without happy patients is unlikely to thrive, but initiatives aimed at improving patient-centered care might do well to maximize the quality of communication with patients, rather than to focus solely on satisfaction.

Effective care can be particularly challenging to measure in the absence of widely accepted clinical quality measures. DataDerm measures, appropriate use criteria, and clinical guidelines all may serve to inspire QI projects for a broad range of practice settings. Diagnostic error is particularly challenging, but approaches to improving diagnostic accuracy have been published.13,14 Case reviews may reduce diagnostic errors, and dermatopathologists may consider second-opinion pathologic review of challenging cases.15

Promotion of equitable care is often overlooked as a QI opportunity. Lower socioeconomic status correlates with poorer medical outcomes. For example, melanoma patients who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid present with higher-stage disease, are less likely to be treated, and demonstrate worse survival compared to non-Medicaid insured patients.16 It is important to recognize inequity in health care access and outcomes, and dermatologists can participate in addressing disparities in care.

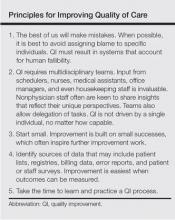

How can an individual physician proceed? There are general principles that can guide physicians in any practice setting (Table).

Any of us can be forgiven for being frustrated by ever-increasing mandates that purport to address quality and for feeling paralyzed when asked to do our part to improve the value of the American health care system. The key to successful QI is to continually identify small processes that can be improved while focusing on one’s patients, colleagues, staff, and community. A well-designed process can and will result in better care, lower costs, and happier physicians and staff. With time, disparate and coordinated efforts among physicians and systems can inform and promote national QI efforts.

1. Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, et al. National health spending in 2014: faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:150-160.

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Vol 627. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759-769.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600-1613.

5. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-576.

6. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

7. Elston DM, Taylor JS, Coldiron B, et al. Part I. patient safety and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:179-190.

8. Elston DM, Stratman E, Johnson-Jahangir H, et al. Part II. opportunities for improvement in patient safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:193-205.

9. Watson AJ, Redbord K, Taylor JS, et al. Medical error in dermatology practice: development of a classification system to drive priority setting in patient safety efforts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;68:729-737.

10. American Medical Association. STEPS Forward website. http://www.stepsforward.org. Accessed March 8, 2016.

11. Zolnierick KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.

12. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405-411.

13. Dunbar M, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Reducing cognitive errors in dermatology: can anything be done? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:810-813.

14. Groszkruger D. Diagnostic error: untapped potential for improving patient safety. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2014;34:38-43.

15. Middleton LP, Feeley TW, Albright HW, et al. Second-opinion pathologic review is a patient safety mechanism that helps reduce error and decrease waste. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:275-280.

16. Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18-64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316.

As Director for Quality Improvement in an academic department, I frequently remind my colleagues that "quality" is not a 4-letter word. Unfortunately, quality is linked in many physicians’ minds to increasing practice complexity and an alphabet soup of acronyms, such as PQRS (Physician Quality Reporting System), MU (meaningful use), and MOC (Maintenance of Certification), among others. Quality improvement (QI) can and should be driven by a desire to improve patient outcomes, professional satisfaction, and operational efficiency, so how should dermatologists respond?

It is helpful to consider why measures of quality are increasingly tied to payment. Conventional wisdom suggests that the American health care system provides poor value. In 2014, total health care expenditures in the United States were $3.0 trillion ($9523 per person), representing 17.5% of the gross domestic product.1 In 1999, the Institute of Medicine estimated that 44,000 to 98,000 individuals die each year due to hospital-based medical errors.2 Noting poor outcomes and high costs, Berwick et al3 proposed the triple aim of improving the experience of care, improving health of populations, and reducing cost. If health care is too expensive and if quality includes outcomes and safety, then improved value of health care must couple cost reduction to QI. Although the future of health care reform is uncertain, it is reasonable to assume that physicians will be expected to care for more patients with fewer dollars. In that context, maximizing operational efficiency and thus economic viability is key. Our challenge is to remain focused on our patients and to identify opportunities to improve the value of their care, both by reducing costs and improving quality.

Health care systems, however, cannot improve with an unhappy and burned-out workforce. Recent data demonstrate high rates of professional burnout among physicians, including dermatologists.4 Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 propose the quadruple aim, which adds improving physician and staff work-life balance to the elements of the triple aim. Burned-out physicians cannot constructively participate in achieving the goals of the triple aim, and physician and staff satisfaction must be a component of any QI paradigm.

The Institute of Medicine has proposed 6 specific aims for improving health care systems: health care should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.6 These aims, taken together with the quadruple aim, can serve as a foundation for developing QI projects for practices and health systems.

Patient safety is a well-recognized issue in dermatology.7-9 Specimen labeling errors, medication errors, wrong-site surgery, and postprocedure complications are examples of safety issues. Quality improvement directed toward improved professional satisfaction for physicians and staff also is critical. The suggestions offered by Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 are directed to primary care providers but are applicable to many dermatology practices. The American Medical Association’s STEPS Forward initiative provides online tutorials that guide practice improvements aimed at improving professional satisfaction and operational efficiency.10

Patient-centered care need not focus solely on patient satisfaction. Clearly, a physician’s duty is to do what is best for each patient, but patient satisfaction and experience are increasingly common measures of quality. Although evidence suggests that measures of physician-patient communication correlate with patient compliance,11 higher patient satisfaction scores may also correlate with higher cost and increased mortality.12 A practice without happy patients is unlikely to thrive, but initiatives aimed at improving patient-centered care might do well to maximize the quality of communication with patients, rather than to focus solely on satisfaction.

Effective care can be particularly challenging to measure in the absence of widely accepted clinical quality measures. DataDerm measures, appropriate use criteria, and clinical guidelines all may serve to inspire QI projects for a broad range of practice settings. Diagnostic error is particularly challenging, but approaches to improving diagnostic accuracy have been published.13,14 Case reviews may reduce diagnostic errors, and dermatopathologists may consider second-opinion pathologic review of challenging cases.15

Promotion of equitable care is often overlooked as a QI opportunity. Lower socioeconomic status correlates with poorer medical outcomes. For example, melanoma patients who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid present with higher-stage disease, are less likely to be treated, and demonstrate worse survival compared to non-Medicaid insured patients.16 It is important to recognize inequity in health care access and outcomes, and dermatologists can participate in addressing disparities in care.

How can an individual physician proceed? There are general principles that can guide physicians in any practice setting (Table).

Any of us can be forgiven for being frustrated by ever-increasing mandates that purport to address quality and for feeling paralyzed when asked to do our part to improve the value of the American health care system. The key to successful QI is to continually identify small processes that can be improved while focusing on one’s patients, colleagues, staff, and community. A well-designed process can and will result in better care, lower costs, and happier physicians and staff. With time, disparate and coordinated efforts among physicians and systems can inform and promote national QI efforts.

As Director for Quality Improvement in an academic department, I frequently remind my colleagues that "quality" is not a 4-letter word. Unfortunately, quality is linked in many physicians’ minds to increasing practice complexity and an alphabet soup of acronyms, such as PQRS (Physician Quality Reporting System), MU (meaningful use), and MOC (Maintenance of Certification), among others. Quality improvement (QI) can and should be driven by a desire to improve patient outcomes, professional satisfaction, and operational efficiency, so how should dermatologists respond?

It is helpful to consider why measures of quality are increasingly tied to payment. Conventional wisdom suggests that the American health care system provides poor value. In 2014, total health care expenditures in the United States were $3.0 trillion ($9523 per person), representing 17.5% of the gross domestic product.1 In 1999, the Institute of Medicine estimated that 44,000 to 98,000 individuals die each year due to hospital-based medical errors.2 Noting poor outcomes and high costs, Berwick et al3 proposed the triple aim of improving the experience of care, improving health of populations, and reducing cost. If health care is too expensive and if quality includes outcomes and safety, then improved value of health care must couple cost reduction to QI. Although the future of health care reform is uncertain, it is reasonable to assume that physicians will be expected to care for more patients with fewer dollars. In that context, maximizing operational efficiency and thus economic viability is key. Our challenge is to remain focused on our patients and to identify opportunities to improve the value of their care, both by reducing costs and improving quality.

Health care systems, however, cannot improve with an unhappy and burned-out workforce. Recent data demonstrate high rates of professional burnout among physicians, including dermatologists.4 Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 propose the quadruple aim, which adds improving physician and staff work-life balance to the elements of the triple aim. Burned-out physicians cannot constructively participate in achieving the goals of the triple aim, and physician and staff satisfaction must be a component of any QI paradigm.

The Institute of Medicine has proposed 6 specific aims for improving health care systems: health care should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.6 These aims, taken together with the quadruple aim, can serve as a foundation for developing QI projects for practices and health systems.

Patient safety is a well-recognized issue in dermatology.7-9 Specimen labeling errors, medication errors, wrong-site surgery, and postprocedure complications are examples of safety issues. Quality improvement directed toward improved professional satisfaction for physicians and staff also is critical. The suggestions offered by Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 are directed to primary care providers but are applicable to many dermatology practices. The American Medical Association’s STEPS Forward initiative provides online tutorials that guide practice improvements aimed at improving professional satisfaction and operational efficiency.10

Patient-centered care need not focus solely on patient satisfaction. Clearly, a physician’s duty is to do what is best for each patient, but patient satisfaction and experience are increasingly common measures of quality. Although evidence suggests that measures of physician-patient communication correlate with patient compliance,11 higher patient satisfaction scores may also correlate with higher cost and increased mortality.12 A practice without happy patients is unlikely to thrive, but initiatives aimed at improving patient-centered care might do well to maximize the quality of communication with patients, rather than to focus solely on satisfaction.

Effective care can be particularly challenging to measure in the absence of widely accepted clinical quality measures. DataDerm measures, appropriate use criteria, and clinical guidelines all may serve to inspire QI projects for a broad range of practice settings. Diagnostic error is particularly challenging, but approaches to improving diagnostic accuracy have been published.13,14 Case reviews may reduce diagnostic errors, and dermatopathologists may consider second-opinion pathologic review of challenging cases.15

Promotion of equitable care is often overlooked as a QI opportunity. Lower socioeconomic status correlates with poorer medical outcomes. For example, melanoma patients who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid present with higher-stage disease, are less likely to be treated, and demonstrate worse survival compared to non-Medicaid insured patients.16 It is important to recognize inequity in health care access and outcomes, and dermatologists can participate in addressing disparities in care.

How can an individual physician proceed? There are general principles that can guide physicians in any practice setting (Table).

Any of us can be forgiven for being frustrated by ever-increasing mandates that purport to address quality and for feeling paralyzed when asked to do our part to improve the value of the American health care system. The key to successful QI is to continually identify small processes that can be improved while focusing on one’s patients, colleagues, staff, and community. A well-designed process can and will result in better care, lower costs, and happier physicians and staff. With time, disparate and coordinated efforts among physicians and systems can inform and promote national QI efforts.

1. Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, et al. National health spending in 2014: faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:150-160.

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Vol 627. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759-769.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600-1613.

5. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-576.

6. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

7. Elston DM, Taylor JS, Coldiron B, et al. Part I. patient safety and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:179-190.

8. Elston DM, Stratman E, Johnson-Jahangir H, et al. Part II. opportunities for improvement in patient safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:193-205.

9. Watson AJ, Redbord K, Taylor JS, et al. Medical error in dermatology practice: development of a classification system to drive priority setting in patient safety efforts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;68:729-737.

10. American Medical Association. STEPS Forward website. http://www.stepsforward.org. Accessed March 8, 2016.

11. Zolnierick KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.

12. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405-411.

13. Dunbar M, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Reducing cognitive errors in dermatology: can anything be done? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:810-813.

14. Groszkruger D. Diagnostic error: untapped potential for improving patient safety. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2014;34:38-43.

15. Middleton LP, Feeley TW, Albright HW, et al. Second-opinion pathologic review is a patient safety mechanism that helps reduce error and decrease waste. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:275-280.

16. Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18-64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316.

1. Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, et al. National health spending in 2014: faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:150-160.

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Vol 627. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759-769.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600-1613.

5. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-576.

6. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

7. Elston DM, Taylor JS, Coldiron B, et al. Part I. patient safety and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:179-190.

8. Elston DM, Stratman E, Johnson-Jahangir H, et al. Part II. opportunities for improvement in patient safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:193-205.

9. Watson AJ, Redbord K, Taylor JS, et al. Medical error in dermatology practice: development of a classification system to drive priority setting in patient safety efforts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;68:729-737.

10. American Medical Association. STEPS Forward website. http://www.stepsforward.org. Accessed March 8, 2016.

11. Zolnierick KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.

12. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405-411.

13. Dunbar M, Helms SE, Brodell RT. Reducing cognitive errors in dermatology: can anything be done? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:810-813.

14. Groszkruger D. Diagnostic error: untapped potential for improving patient safety. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2014;34:38-43.

15. Middleton LP, Feeley TW, Albright HW, et al. Second-opinion pathologic review is a patient safety mechanism that helps reduce error and decrease waste. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:275-280.

16. Amini A, Rusthoven CG, Waxweiler TV, et al. Association of health insurance with outcomes in adults ages 18-64 years with melanoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:309-316.