User login

Despite the ability of some couples to pull together and manage through the COVID-19 pandemic, other couples and families failed to thrive. Increasing divorce rates have been noted nationwide with many disagreements being specifically about COVID.1

A review of over 1 million tweets, between April 12 and July 16, 2020, found an increase in calls to hotlines and increased reports of a variety of types of family violence. There were also more inquiries about social services for family violence, an increased presence from social movements, and more domestic violence-related news.2

The literature addressing family violence uses a variety of terms, so here are some definitions.

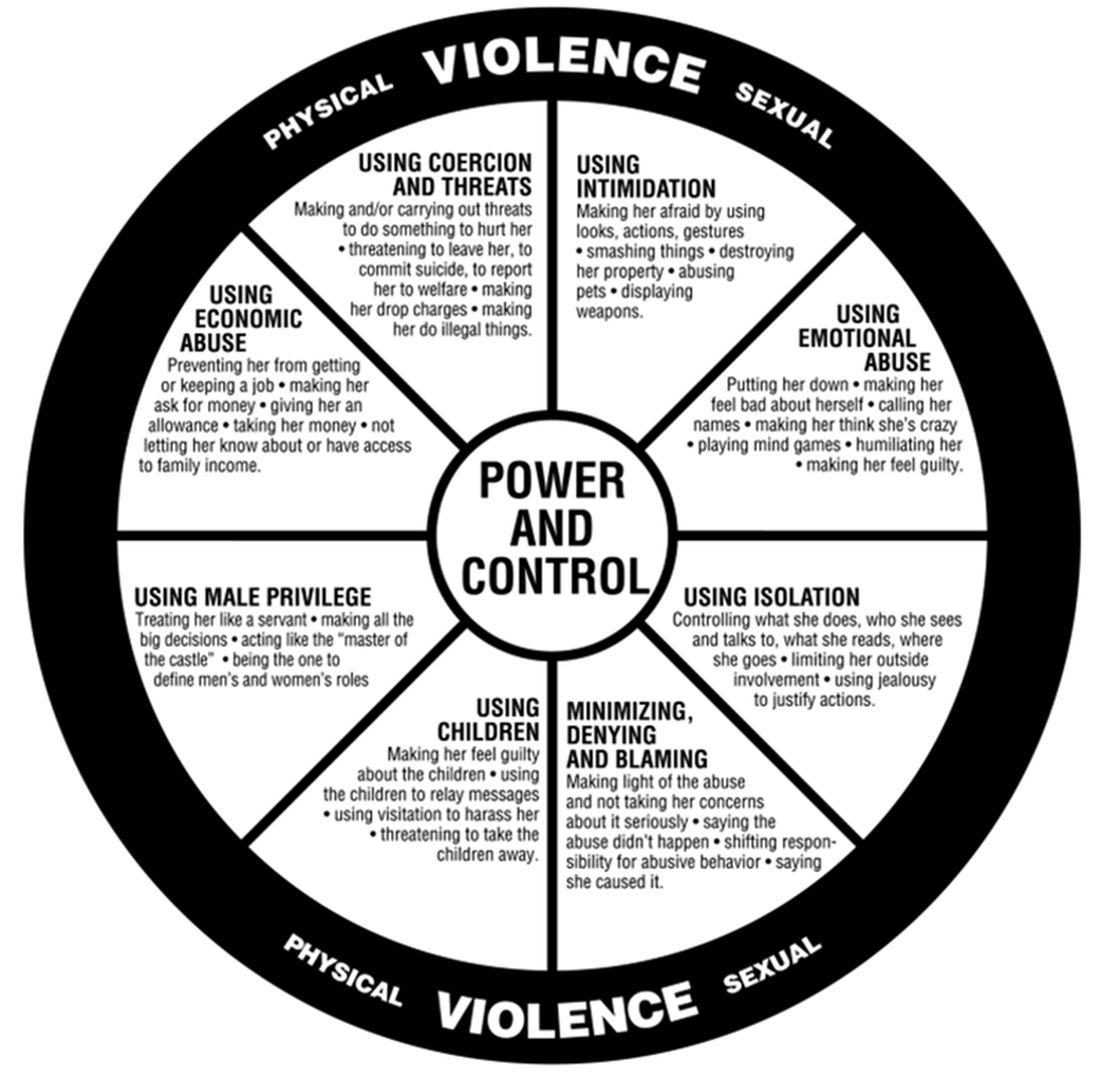

Domestic violence is defined as a pattern of behaviors used to gain or maintain power and control. Broadly speaking, domestic violence includes elder abuse, sibling abuse, child abuse, intimate partner abuse, parent abuse, and can also include people who don’t necessarily live together but who have an intimate relationship. Domestic violence centers use the Power and Control Wheel (see graphic) developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minn., to describe how domestic violence occurs.

Intimate partner violence is more specific, referring to violence that happens between people in an ongoing or former intimate or romantic relationship, and is a subcategory of domestic violence.

Coercive control is the use of power for control and compliance. It is a dynamic and systematic process described in the top left corner of the Power and Control Wheel. Overt control occurs with the implication that “if you don’t follow the rules, I’ll kill you.” More subtle control is when obedience is forced through monopolizing resources, dictating preferred choices, microregulating a partner’s behavior, and deprivation of supports needed to exercise independent judgment.

All interpersonal relationships have elements of persuasion and influence; however, the goal of coercive relationships is to maintain power and control. It is a dynamic of the relationship. Coercive control emphasizes the systematic, organized, multifaceted, and patterned nature of this interpersonal dynamic and can be considered to originate in the patriarchal dynamic where men control women.

Most professionals who work in this interdisciplinary area now refer to domestic violence as coercive control. Victimizers target women whom they sense they can control to get their own needs met. They are disinclined to invest in relationships with women who stress their own points of view, who do not readily accept blame when there is a disagreement, and who offer nurturing only when it is reciprocated.

In my office, if I think there are elements of coercion in a relationship, I bring out the Power and Control Wheel and the patient and I go over it. Good education is our responsibility. However, we all have met women who decide to stay in unhealthy relationships.

Assessing people who stay in coercive relationships

Fear

The most important first step is to assess safety. Are they afraid of increased violence if they challenge their partner? Restraining orders or other legal deterrents may not offer solace, as many women are clear that their spouse will come after them, if not tomorrow, then next week, or even next month. They are sure that they will not be safe.

In these cases, I go over safety steps with them so that if they decide to go, they will be prepared. I bring out the “safety box,” which includes the following action steps:

- Memorize important phone numbers of people to call in an emergency.

- If your children are old enough, teach them important phone numbers, including when to dial 911.

- If you can, open your own bank account.

- Stay in touch with friends. Get to know your neighbors. Don’t cut yourself off from people, even if you feel like you want to be alone.

- Rehearse your escape plan until you know it by heart.

- Leave a set of car keys, extra money, a change of clothes and copies of important documents with a trusted friend or relative: your own and your children’s birth certificates, children’s school and medical records, bank books, welfare identification, passport/green card, immigration papers, social security card, lease agreements or mortgage payment books, insurance papers, important addresses, and telephone numbers.

- Keep information about domestic violence in a safe place, where your abuser won’t find it, but where you can get it when you need to review it.

Some women may acknowledge that the risk of physical violence is not the determining factor in their decision to stay and have difficulty explaining why they choose to stay. I suggest that we then consider the following frames that have their origin in the study of the impact of trauma.

Shame

From this lens, abusive events are humiliating experiences, now represented as shame experiences. Humiliation and shame hide hostile feelings that the patient is not able to acknowledge.

“In shame, the self is the failure and others may reject or be critical of this exposed, flawed self.”3 Women will therefore remain attached to an abuser to avoid the exposure of their defective self.

Action steps: Empathic engagement and acknowledgment of shame and humiliation are key. For someone to overcome shame, they must face their sense of their defective self and have strategies to manage these feelings. The development of such strategies is the next step.

Trauma repetition and trauma bonding

Women subjected to domestic violence often respond with incapacitating traumatic syndromes. The concept of “trauma repetition” is suggested as a cause of vulnerability to repeated abuse, and “trauma bonding” is the term for the intense and tenacious bond that can form between abusers and victims.4

Trauma bonding implies that a sense of safety and closeness and secure attachment can only be reached through highly abusive engagement; anything else is experienced as “superficial, cold, or irrelevant.”5 Trauma bonding may have its origins in emotional neglect, according to self reports of 116 women.6Action steps: The literature on trauma is growing and many patients will benefit from good curated sources. Having a good list of books and website on hand is important. Discussion and exploration of the impact of trauma will be needed, and can be provided by someone who is available on a consistent and frequent basis. This work may be time consuming and difficult.

Some asides

1. Some psychiatrists proffer the explanation that these women who stay must be masochistic. The misogynistic concept of masochism still haunts the halls of psychiatry. It is usually offered as a way to dismiss these women’s concerns.

2. One of the obstacles to recognizing chronic mistreatment in relationships is that most abusive men simply “do not seem like abusers.” They have many good qualities, including times of kindness, warmth, and humor, especially in the initial period of a relationship. An abuser’s friends may think the world of him. He may have a successful work life and have no problems with drugs or alcohol. He may simply not fit anyone’s image of a cruel or intimidating person. So, when a woman feels her relationship spinning out of control, it may not occur to her that her partner is an abuser. Even if she does consider her partner to be overly controlling, others may question her perception.

3. Neutrality in family courts is systemic sexism/misogyny. When it comes to domestic violence, family courts tend to split the difference. Stephanie Brandt, MD, notes that The assumption that it is violence alone that matters has formed the basis of much clinical and legal confusion.7 As an analyst, she has gone against the grain of a favored neutrality and become active in the courts, noting the secondary victimization that occurs when a woman enters the legal system.

In summary, psychiatrists must reclaim our expertise in systemic dynamics and point out the role of systemic misogyny. Justices and other court officials need to be educated. Ideally, justice should be based on the equality of men and women in a society free of systemic misogyny. Unfortunately our society has not yet reached this position. In the meanwhile, we must think systemically about interpersonal dynamics. This is our lane. This should not be controversial.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at alisonheru@gmail.com. Dr. Heru would like to thank Dr. Stephanie Brandt for discussing this topic with her and supporting this work.

References

1. Ellyatt H. Arguing with your partner over Covid? You’re not alone, with the pandemic straining many relationships. 2022 Jan 21. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/21/covid-has-put-pressures-and-strains-on-relationships.html

2. Xue J et al. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 6;22(11):e24361. doi: 10.2196/24361.

3. Dorahy MJ. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):383-96. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295422.

4. Dutton DG and Painter SL. Victimology. 1981 Jan;6(1):139-55.

5. Sachs A. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):319-39. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295400.

6. Krüger C and Fletcher L. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):356-72. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295420.

7. Brandt S and Rudden M. Int J Appl Psychoanal Studies. 2020 Sept;17(3):215-31. doi: 10.1002/aps.1671.

Despite the ability of some couples to pull together and manage through the COVID-19 pandemic, other couples and families failed to thrive. Increasing divorce rates have been noted nationwide with many disagreements being specifically about COVID.1

A review of over 1 million tweets, between April 12 and July 16, 2020, found an increase in calls to hotlines and increased reports of a variety of types of family violence. There were also more inquiries about social services for family violence, an increased presence from social movements, and more domestic violence-related news.2

The literature addressing family violence uses a variety of terms, so here are some definitions.

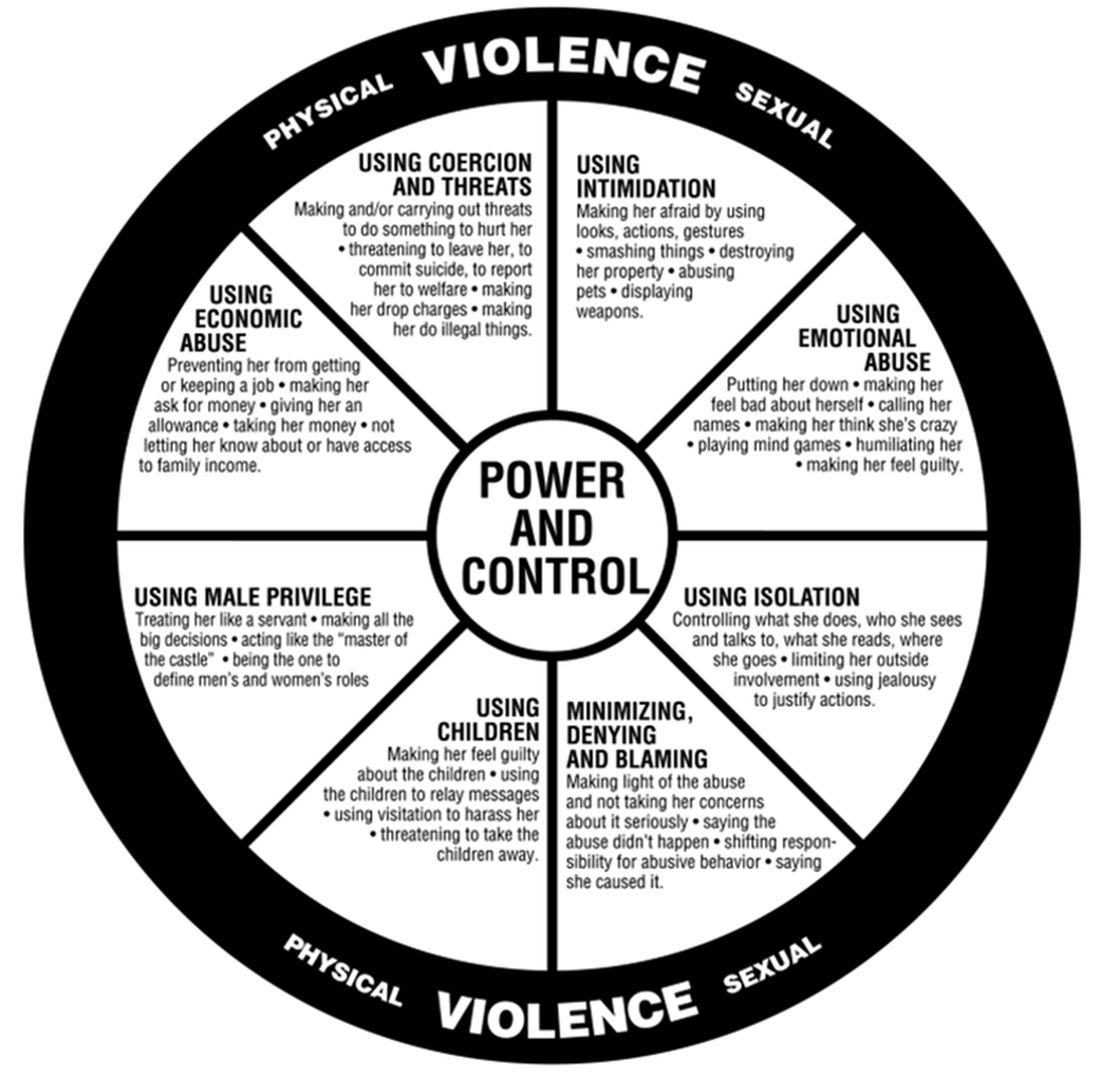

Domestic violence is defined as a pattern of behaviors used to gain or maintain power and control. Broadly speaking, domestic violence includes elder abuse, sibling abuse, child abuse, intimate partner abuse, parent abuse, and can also include people who don’t necessarily live together but who have an intimate relationship. Domestic violence centers use the Power and Control Wheel (see graphic) developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minn., to describe how domestic violence occurs.

Intimate partner violence is more specific, referring to violence that happens between people in an ongoing or former intimate or romantic relationship, and is a subcategory of domestic violence.

Coercive control is the use of power for control and compliance. It is a dynamic and systematic process described in the top left corner of the Power and Control Wheel. Overt control occurs with the implication that “if you don’t follow the rules, I’ll kill you.” More subtle control is when obedience is forced through monopolizing resources, dictating preferred choices, microregulating a partner’s behavior, and deprivation of supports needed to exercise independent judgment.

All interpersonal relationships have elements of persuasion and influence; however, the goal of coercive relationships is to maintain power and control. It is a dynamic of the relationship. Coercive control emphasizes the systematic, organized, multifaceted, and patterned nature of this interpersonal dynamic and can be considered to originate in the patriarchal dynamic where men control women.

Most professionals who work in this interdisciplinary area now refer to domestic violence as coercive control. Victimizers target women whom they sense they can control to get their own needs met. They are disinclined to invest in relationships with women who stress their own points of view, who do not readily accept blame when there is a disagreement, and who offer nurturing only when it is reciprocated.

In my office, if I think there are elements of coercion in a relationship, I bring out the Power and Control Wheel and the patient and I go over it. Good education is our responsibility. However, we all have met women who decide to stay in unhealthy relationships.

Assessing people who stay in coercive relationships

Fear

The most important first step is to assess safety. Are they afraid of increased violence if they challenge their partner? Restraining orders or other legal deterrents may not offer solace, as many women are clear that their spouse will come after them, if not tomorrow, then next week, or even next month. They are sure that they will not be safe.

In these cases, I go over safety steps with them so that if they decide to go, they will be prepared. I bring out the “safety box,” which includes the following action steps:

- Memorize important phone numbers of people to call in an emergency.

- If your children are old enough, teach them important phone numbers, including when to dial 911.

- If you can, open your own bank account.

- Stay in touch with friends. Get to know your neighbors. Don’t cut yourself off from people, even if you feel like you want to be alone.

- Rehearse your escape plan until you know it by heart.

- Leave a set of car keys, extra money, a change of clothes and copies of important documents with a trusted friend or relative: your own and your children’s birth certificates, children’s school and medical records, bank books, welfare identification, passport/green card, immigration papers, social security card, lease agreements or mortgage payment books, insurance papers, important addresses, and telephone numbers.

- Keep information about domestic violence in a safe place, where your abuser won’t find it, but where you can get it when you need to review it.

Some women may acknowledge that the risk of physical violence is not the determining factor in their decision to stay and have difficulty explaining why they choose to stay. I suggest that we then consider the following frames that have their origin in the study of the impact of trauma.

Shame

From this lens, abusive events are humiliating experiences, now represented as shame experiences. Humiliation and shame hide hostile feelings that the patient is not able to acknowledge.

“In shame, the self is the failure and others may reject or be critical of this exposed, flawed self.”3 Women will therefore remain attached to an abuser to avoid the exposure of their defective self.

Action steps: Empathic engagement and acknowledgment of shame and humiliation are key. For someone to overcome shame, they must face their sense of their defective self and have strategies to manage these feelings. The development of such strategies is the next step.

Trauma repetition and trauma bonding

Women subjected to domestic violence often respond with incapacitating traumatic syndromes. The concept of “trauma repetition” is suggested as a cause of vulnerability to repeated abuse, and “trauma bonding” is the term for the intense and tenacious bond that can form between abusers and victims.4

Trauma bonding implies that a sense of safety and closeness and secure attachment can only be reached through highly abusive engagement; anything else is experienced as “superficial, cold, or irrelevant.”5 Trauma bonding may have its origins in emotional neglect, according to self reports of 116 women.6Action steps: The literature on trauma is growing and many patients will benefit from good curated sources. Having a good list of books and website on hand is important. Discussion and exploration of the impact of trauma will be needed, and can be provided by someone who is available on a consistent and frequent basis. This work may be time consuming and difficult.

Some asides

1. Some psychiatrists proffer the explanation that these women who stay must be masochistic. The misogynistic concept of masochism still haunts the halls of psychiatry. It is usually offered as a way to dismiss these women’s concerns.

2. One of the obstacles to recognizing chronic mistreatment in relationships is that most abusive men simply “do not seem like abusers.” They have many good qualities, including times of kindness, warmth, and humor, especially in the initial period of a relationship. An abuser’s friends may think the world of him. He may have a successful work life and have no problems with drugs or alcohol. He may simply not fit anyone’s image of a cruel or intimidating person. So, when a woman feels her relationship spinning out of control, it may not occur to her that her partner is an abuser. Even if she does consider her partner to be overly controlling, others may question her perception.

3. Neutrality in family courts is systemic sexism/misogyny. When it comes to domestic violence, family courts tend to split the difference. Stephanie Brandt, MD, notes that The assumption that it is violence alone that matters has formed the basis of much clinical and legal confusion.7 As an analyst, she has gone against the grain of a favored neutrality and become active in the courts, noting the secondary victimization that occurs when a woman enters the legal system.

In summary, psychiatrists must reclaim our expertise in systemic dynamics and point out the role of systemic misogyny. Justices and other court officials need to be educated. Ideally, justice should be based on the equality of men and women in a society free of systemic misogyny. Unfortunately our society has not yet reached this position. In the meanwhile, we must think systemically about interpersonal dynamics. This is our lane. This should not be controversial.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at alisonheru@gmail.com. Dr. Heru would like to thank Dr. Stephanie Brandt for discussing this topic with her and supporting this work.

References

1. Ellyatt H. Arguing with your partner over Covid? You’re not alone, with the pandemic straining many relationships. 2022 Jan 21. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/21/covid-has-put-pressures-and-strains-on-relationships.html

2. Xue J et al. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 6;22(11):e24361. doi: 10.2196/24361.

3. Dorahy MJ. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):383-96. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295422.

4. Dutton DG and Painter SL. Victimology. 1981 Jan;6(1):139-55.

5. Sachs A. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):319-39. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295400.

6. Krüger C and Fletcher L. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):356-72. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295420.

7. Brandt S and Rudden M. Int J Appl Psychoanal Studies. 2020 Sept;17(3):215-31. doi: 10.1002/aps.1671.

Despite the ability of some couples to pull together and manage through the COVID-19 pandemic, other couples and families failed to thrive. Increasing divorce rates have been noted nationwide with many disagreements being specifically about COVID.1

A review of over 1 million tweets, between April 12 and July 16, 2020, found an increase in calls to hotlines and increased reports of a variety of types of family violence. There were also more inquiries about social services for family violence, an increased presence from social movements, and more domestic violence-related news.2

The literature addressing family violence uses a variety of terms, so here are some definitions.

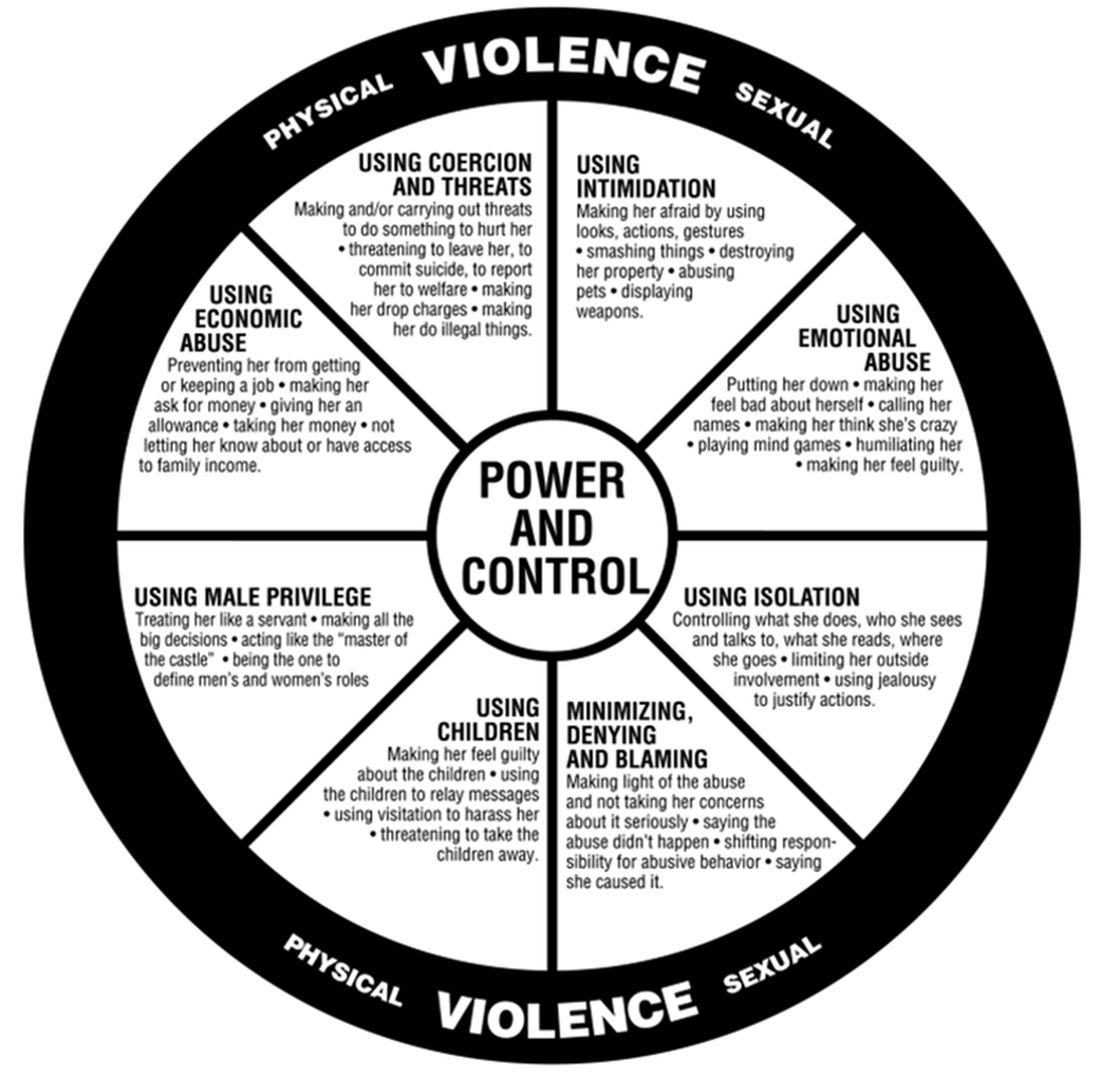

Domestic violence is defined as a pattern of behaviors used to gain or maintain power and control. Broadly speaking, domestic violence includes elder abuse, sibling abuse, child abuse, intimate partner abuse, parent abuse, and can also include people who don’t necessarily live together but who have an intimate relationship. Domestic violence centers use the Power and Control Wheel (see graphic) developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Duluth, Minn., to describe how domestic violence occurs.

Intimate partner violence is more specific, referring to violence that happens between people in an ongoing or former intimate or romantic relationship, and is a subcategory of domestic violence.

Coercive control is the use of power for control and compliance. It is a dynamic and systematic process described in the top left corner of the Power and Control Wheel. Overt control occurs with the implication that “if you don’t follow the rules, I’ll kill you.” More subtle control is when obedience is forced through monopolizing resources, dictating preferred choices, microregulating a partner’s behavior, and deprivation of supports needed to exercise independent judgment.

All interpersonal relationships have elements of persuasion and influence; however, the goal of coercive relationships is to maintain power and control. It is a dynamic of the relationship. Coercive control emphasizes the systematic, organized, multifaceted, and patterned nature of this interpersonal dynamic and can be considered to originate in the patriarchal dynamic where men control women.

Most professionals who work in this interdisciplinary area now refer to domestic violence as coercive control. Victimizers target women whom they sense they can control to get their own needs met. They are disinclined to invest in relationships with women who stress their own points of view, who do not readily accept blame when there is a disagreement, and who offer nurturing only when it is reciprocated.

In my office, if I think there are elements of coercion in a relationship, I bring out the Power and Control Wheel and the patient and I go over it. Good education is our responsibility. However, we all have met women who decide to stay in unhealthy relationships.

Assessing people who stay in coercive relationships

Fear

The most important first step is to assess safety. Are they afraid of increased violence if they challenge their partner? Restraining orders or other legal deterrents may not offer solace, as many women are clear that their spouse will come after them, if not tomorrow, then next week, or even next month. They are sure that they will not be safe.

In these cases, I go over safety steps with them so that if they decide to go, they will be prepared. I bring out the “safety box,” which includes the following action steps:

- Memorize important phone numbers of people to call in an emergency.

- If your children are old enough, teach them important phone numbers, including when to dial 911.

- If you can, open your own bank account.

- Stay in touch with friends. Get to know your neighbors. Don’t cut yourself off from people, even if you feel like you want to be alone.

- Rehearse your escape plan until you know it by heart.

- Leave a set of car keys, extra money, a change of clothes and copies of important documents with a trusted friend or relative: your own and your children’s birth certificates, children’s school and medical records, bank books, welfare identification, passport/green card, immigration papers, social security card, lease agreements or mortgage payment books, insurance papers, important addresses, and telephone numbers.

- Keep information about domestic violence in a safe place, where your abuser won’t find it, but where you can get it when you need to review it.

Some women may acknowledge that the risk of physical violence is not the determining factor in their decision to stay and have difficulty explaining why they choose to stay. I suggest that we then consider the following frames that have their origin in the study of the impact of trauma.

Shame

From this lens, abusive events are humiliating experiences, now represented as shame experiences. Humiliation and shame hide hostile feelings that the patient is not able to acknowledge.

“In shame, the self is the failure and others may reject or be critical of this exposed, flawed self.”3 Women will therefore remain attached to an abuser to avoid the exposure of their defective self.

Action steps: Empathic engagement and acknowledgment of shame and humiliation are key. For someone to overcome shame, they must face their sense of their defective self and have strategies to manage these feelings. The development of such strategies is the next step.

Trauma repetition and trauma bonding

Women subjected to domestic violence often respond with incapacitating traumatic syndromes. The concept of “trauma repetition” is suggested as a cause of vulnerability to repeated abuse, and “trauma bonding” is the term for the intense and tenacious bond that can form between abusers and victims.4

Trauma bonding implies that a sense of safety and closeness and secure attachment can only be reached through highly abusive engagement; anything else is experienced as “superficial, cold, or irrelevant.”5 Trauma bonding may have its origins in emotional neglect, according to self reports of 116 women.6Action steps: The literature on trauma is growing and many patients will benefit from good curated sources. Having a good list of books and website on hand is important. Discussion and exploration of the impact of trauma will be needed, and can be provided by someone who is available on a consistent and frequent basis. This work may be time consuming and difficult.

Some asides

1. Some psychiatrists proffer the explanation that these women who stay must be masochistic. The misogynistic concept of masochism still haunts the halls of psychiatry. It is usually offered as a way to dismiss these women’s concerns.

2. One of the obstacles to recognizing chronic mistreatment in relationships is that most abusive men simply “do not seem like abusers.” They have many good qualities, including times of kindness, warmth, and humor, especially in the initial period of a relationship. An abuser’s friends may think the world of him. He may have a successful work life and have no problems with drugs or alcohol. He may simply not fit anyone’s image of a cruel or intimidating person. So, when a woman feels her relationship spinning out of control, it may not occur to her that her partner is an abuser. Even if she does consider her partner to be overly controlling, others may question her perception.

3. Neutrality in family courts is systemic sexism/misogyny. When it comes to domestic violence, family courts tend to split the difference. Stephanie Brandt, MD, notes that The assumption that it is violence alone that matters has formed the basis of much clinical and legal confusion.7 As an analyst, she has gone against the grain of a favored neutrality and become active in the courts, noting the secondary victimization that occurs when a woman enters the legal system.

In summary, psychiatrists must reclaim our expertise in systemic dynamics and point out the role of systemic misogyny. Justices and other court officials need to be educated. Ideally, justice should be based on the equality of men and women in a society free of systemic misogyny. Unfortunately our society has not yet reached this position. In the meanwhile, we must think systemically about interpersonal dynamics. This is our lane. This should not be controversial.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at alisonheru@gmail.com. Dr. Heru would like to thank Dr. Stephanie Brandt for discussing this topic with her and supporting this work.

References

1. Ellyatt H. Arguing with your partner over Covid? You’re not alone, with the pandemic straining many relationships. 2022 Jan 21. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/21/covid-has-put-pressures-and-strains-on-relationships.html

2. Xue J et al. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 6;22(11):e24361. doi: 10.2196/24361.

3. Dorahy MJ. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):383-96. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295422.

4. Dutton DG and Painter SL. Victimology. 1981 Jan;6(1):139-55.

5. Sachs A. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):319-39. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295400.

6. Krüger C and Fletcher L. J Trauma Dissociation. 2017 May-Jun;18(3):356-72. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1295420.

7. Brandt S and Rudden M. Int J Appl Psychoanal Studies. 2020 Sept;17(3):215-31. doi: 10.1002/aps.1671.