User login

Clinical Endocrinology News is an independent news source that provides endocrinologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the endocrinologist's practice. Specialty topics include Diabetes, Lipid & Metabolic Disorders Menopause, Obesity, Osteoporosis, Pediatric Endocrinology, Pituitary, Thyroid & Adrenal Disorders, and Reproductive Endocrinology. Featured content includes Commentaries, Implementin Health Reform, Law & Medicine, and In the Loop, the blog of Clinical Endocrinology News. Clinical Endocrinology News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

addict

addicted

addicting

addiction

adult sites

alcohol

antibody

ass

attorney

audit

auditor

babies

babpa

baby

ban

banned

banning

best

bisexual

bitch

bleach

blog

blow job

bondage

boobs

booty

buy

cannabis

certificate

certification

certified

cheap

cheapest

class action

cocaine

cock

counterfeit drug

crack

crap

crime

criminal

cunt

curable

cure

dangerous

dangers

dead

deadly

death

defend

defended

depedent

dependence

dependent

detergent

dick

die

dildo

drug abuse

drug recall

dying

fag

fake

fatal

fatalities

fatality

free

fuck

gangs

gingivitis

guns

hardcore

herbal

herbs

heroin

herpes

home remedies

homo

horny

hypersensitivity

hypoglycemia treatment

illegal drug use

illegal use of prescription

incest

infant

infants

job

ketoacidosis

kill

killer

killing

kinky

law suit

lawsuit

lawyer

lesbian

marijuana

medicine for hypoglycemia

murder

naked

natural

newborn

nigger

noise

nude

nudity

orgy

over the counter

overdosage

overdose

overdosed

overdosing

penis

pimp

pistol

porn

porno

pornographic

pornography

prison

profanity

purchase

purchasing

pussy

queer

rape

rapist

recall

recreational drug

rob

robberies

sale

sales

sex

sexual

shit

shoot

slut

slutty

stole

stolen

store

sue

suicidal

suicide

supplements

supply company

theft

thief

thieves

tit

toddler

toddlers

toxic

toxin

tragedy

treating dka

treating hypoglycemia

treatment for hypoglycemia

vagina

violence

whore

withdrawal

without prescription

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-imn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Dining restrictions, mask mandates tied to less illness, death, CDC reaffirms

The numbers are in to back up two policies designed to restrict the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) found that when states lifted restrictions on dining on premises at restaurants, rates of daily COVID-19 cases jumped 41-100 days later. COVID-19-related deaths also increased significantly after 60 days.

On the other hand, the same report demonstrates that state mask mandates slowed the spread of SARS-CoV-2 within a few weeks.

The study was published online March 5 in the CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The investigators did not distinguish between outdoor and indoor restaurant dining. But they did compare COVID-19 case and death rates before and after most states banned restaurants from serving patrons on-premises in March and April 2020.

They found, for example, that COVID-19 daily cases increased by 0.9% at 41-60 days after on-premise dining was permitted. Similarly, rates jumped by 1.2% at 61-80 days, and 1.1% at 81-100 days after the restaurant restrictions were lifted.

The differences were statistically significant, with P values of .02, <.01, and .04, respectively.

COVID-19–related death rates did not increase significantly at first – but did jump 2.2% between 61 and 80 days after the return of on-premises dining, for example. Deaths also increased by 3% at 81-100 days.

Both these differences were statistically significant (P < .01).

This is not the first report where the CDC announced reservations about in-person dining. In September 2020, CDC investigators implicated the inability to wear a mask while eating and drinking as likely contributing to the heightened risk.

Masks make a difference

The CDC report also provided more evidence to back mask-wearing policies for public spaces. Between March 1 and Dec. 31, 2020, 74% of U.S. counties issued mask mandates.

Investigators found that these policies had a more immediate effect, reducing daily COVID-19 cases by 0.5% in the first 20 days. Mask mandates likewise were linked to daily cases dropping 1.1% between 21 and 40 days, 1.5% between 41 and 60 days, 1.7% between 61 and 80 days, and 1.8% between 81 and 100 days.

These decreases in daily COVID-19 cases were statistically significant (P < .01) compared with a reference period before March 1, 2020.

The CDC also linked mask mandates to lower mortality. For example, these state policies were associated with 0.7% fewer deaths at 1-20 days post implementation. The effect increased thereafter – 1.0% drop at 21-40 days, 1.4% decrease at 41-60 days, 1.6% drop between 61 and 80 days, and 1.9% fewer deaths between 81 and 100 days.

The decrease in deaths was statistically significant at 1-20 days after the mask mandate (P = .03), as well as during the other periods (each P < .01) compared with the reference period.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, reacted to the new findings at a White House press briefing. She cited how increases in COVID-19 cases and death rates “slowed significantly within 20 days of putting mask mandates into place. This is why I’m asking you to double down on prevention measures.

“We have seen this movie before,” Dr. Walensky added. “When prevention measures like mask-wearing mandates are lifted, cases go up.”

Recently, multiple states have announced plans to roll back restrictions related to the pandemic, including mask mandates, which prompted warnings from some public health officials.

These are not the first CDC data to show that mask mandates make a difference.

In February 2021, for example, the agency pointed out that state-wide mask mandates reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by 5.5% among adults 18-64 years old within 3 weeks of implementation.

Restrictions regarding on-premises restaurant dining and implementation of state-wide mask mandates are two tactics within a more comprehensive CDC strategy to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The researchers note that “such efforts are increasingly important given the emergence of highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants in the United States.”

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The numbers are in to back up two policies designed to restrict the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) found that when states lifted restrictions on dining on premises at restaurants, rates of daily COVID-19 cases jumped 41-100 days later. COVID-19-related deaths also increased significantly after 60 days.

On the other hand, the same report demonstrates that state mask mandates slowed the spread of SARS-CoV-2 within a few weeks.

The study was published online March 5 in the CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The investigators did not distinguish between outdoor and indoor restaurant dining. But they did compare COVID-19 case and death rates before and after most states banned restaurants from serving patrons on-premises in March and April 2020.

They found, for example, that COVID-19 daily cases increased by 0.9% at 41-60 days after on-premise dining was permitted. Similarly, rates jumped by 1.2% at 61-80 days, and 1.1% at 81-100 days after the restaurant restrictions were lifted.

The differences were statistically significant, with P values of .02, <.01, and .04, respectively.

COVID-19–related death rates did not increase significantly at first – but did jump 2.2% between 61 and 80 days after the return of on-premises dining, for example. Deaths also increased by 3% at 81-100 days.

Both these differences were statistically significant (P < .01).

This is not the first report where the CDC announced reservations about in-person dining. In September 2020, CDC investigators implicated the inability to wear a mask while eating and drinking as likely contributing to the heightened risk.

Masks make a difference

The CDC report also provided more evidence to back mask-wearing policies for public spaces. Between March 1 and Dec. 31, 2020, 74% of U.S. counties issued mask mandates.

Investigators found that these policies had a more immediate effect, reducing daily COVID-19 cases by 0.5% in the first 20 days. Mask mandates likewise were linked to daily cases dropping 1.1% between 21 and 40 days, 1.5% between 41 and 60 days, 1.7% between 61 and 80 days, and 1.8% between 81 and 100 days.

These decreases in daily COVID-19 cases were statistically significant (P < .01) compared with a reference period before March 1, 2020.

The CDC also linked mask mandates to lower mortality. For example, these state policies were associated with 0.7% fewer deaths at 1-20 days post implementation. The effect increased thereafter – 1.0% drop at 21-40 days, 1.4% decrease at 41-60 days, 1.6% drop between 61 and 80 days, and 1.9% fewer deaths between 81 and 100 days.

The decrease in deaths was statistically significant at 1-20 days after the mask mandate (P = .03), as well as during the other periods (each P < .01) compared with the reference period.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, reacted to the new findings at a White House press briefing. She cited how increases in COVID-19 cases and death rates “slowed significantly within 20 days of putting mask mandates into place. This is why I’m asking you to double down on prevention measures.

“We have seen this movie before,” Dr. Walensky added. “When prevention measures like mask-wearing mandates are lifted, cases go up.”

Recently, multiple states have announced plans to roll back restrictions related to the pandemic, including mask mandates, which prompted warnings from some public health officials.

These are not the first CDC data to show that mask mandates make a difference.

In February 2021, for example, the agency pointed out that state-wide mask mandates reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by 5.5% among adults 18-64 years old within 3 weeks of implementation.

Restrictions regarding on-premises restaurant dining and implementation of state-wide mask mandates are two tactics within a more comprehensive CDC strategy to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The researchers note that “such efforts are increasingly important given the emergence of highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants in the United States.”

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The numbers are in to back up two policies designed to restrict the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) found that when states lifted restrictions on dining on premises at restaurants, rates of daily COVID-19 cases jumped 41-100 days later. COVID-19-related deaths also increased significantly after 60 days.

On the other hand, the same report demonstrates that state mask mandates slowed the spread of SARS-CoV-2 within a few weeks.

The study was published online March 5 in the CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The investigators did not distinguish between outdoor and indoor restaurant dining. But they did compare COVID-19 case and death rates before and after most states banned restaurants from serving patrons on-premises in March and April 2020.

They found, for example, that COVID-19 daily cases increased by 0.9% at 41-60 days after on-premise dining was permitted. Similarly, rates jumped by 1.2% at 61-80 days, and 1.1% at 81-100 days after the restaurant restrictions were lifted.

The differences were statistically significant, with P values of .02, <.01, and .04, respectively.

COVID-19–related death rates did not increase significantly at first – but did jump 2.2% between 61 and 80 days after the return of on-premises dining, for example. Deaths also increased by 3% at 81-100 days.

Both these differences were statistically significant (P < .01).

This is not the first report where the CDC announced reservations about in-person dining. In September 2020, CDC investigators implicated the inability to wear a mask while eating and drinking as likely contributing to the heightened risk.

Masks make a difference

The CDC report also provided more evidence to back mask-wearing policies for public spaces. Between March 1 and Dec. 31, 2020, 74% of U.S. counties issued mask mandates.

Investigators found that these policies had a more immediate effect, reducing daily COVID-19 cases by 0.5% in the first 20 days. Mask mandates likewise were linked to daily cases dropping 1.1% between 21 and 40 days, 1.5% between 41 and 60 days, 1.7% between 61 and 80 days, and 1.8% between 81 and 100 days.

These decreases in daily COVID-19 cases were statistically significant (P < .01) compared with a reference period before March 1, 2020.

The CDC also linked mask mandates to lower mortality. For example, these state policies were associated with 0.7% fewer deaths at 1-20 days post implementation. The effect increased thereafter – 1.0% drop at 21-40 days, 1.4% decrease at 41-60 days, 1.6% drop between 61 and 80 days, and 1.9% fewer deaths between 81 and 100 days.

The decrease in deaths was statistically significant at 1-20 days after the mask mandate (P = .03), as well as during the other periods (each P < .01) compared with the reference period.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, reacted to the new findings at a White House press briefing. She cited how increases in COVID-19 cases and death rates “slowed significantly within 20 days of putting mask mandates into place. This is why I’m asking you to double down on prevention measures.

“We have seen this movie before,” Dr. Walensky added. “When prevention measures like mask-wearing mandates are lifted, cases go up.”

Recently, multiple states have announced plans to roll back restrictions related to the pandemic, including mask mandates, which prompted warnings from some public health officials.

These are not the first CDC data to show that mask mandates make a difference.

In February 2021, for example, the agency pointed out that state-wide mask mandates reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by 5.5% among adults 18-64 years old within 3 weeks of implementation.

Restrictions regarding on-premises restaurant dining and implementation of state-wide mask mandates are two tactics within a more comprehensive CDC strategy to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The researchers note that “such efforts are increasingly important given the emergence of highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants in the United States.”

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

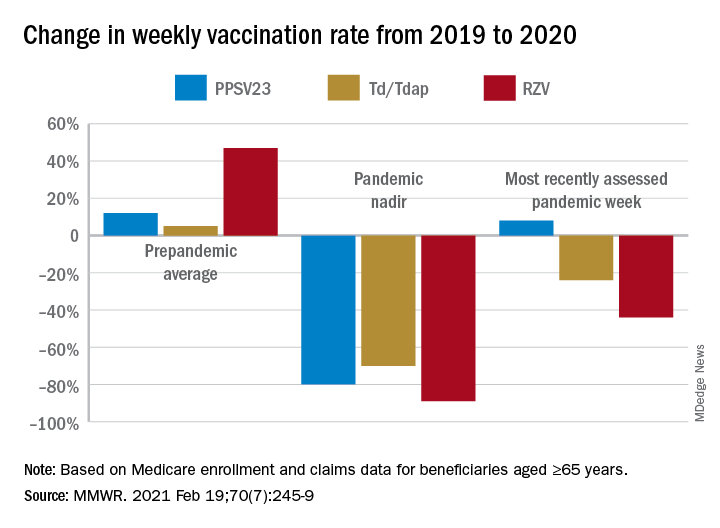

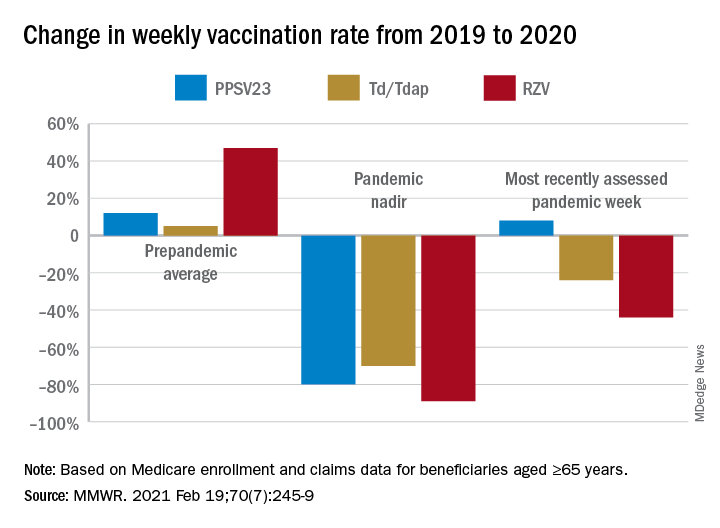

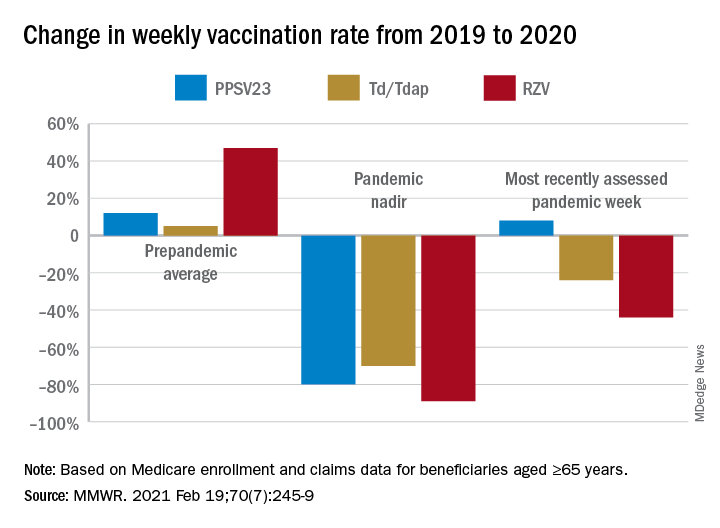

Routine vaccinations missed by older adults during pandemic

Physicians are going to have to play catch-up when it comes to getting older patients their routine, but important, vaccinations missed during the pandemic.

and have recovered only partially and gradually, according to a report by Kai Hong, PhD, and colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “As the pandemic continues,” the investigators stated, “vaccination providers should continue efforts to resolve disruptions in routine adult vaccination.”

The CDC issued guidance recommending postponement of routine adult vaccination in response to the March 13, 2020, COVID-19 national emergency declaration by the U.S. government and also to state and local shelter-in-place orders. Health care facility operations were restricted because of safety concerns around exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The result was a significant drop in routine medical care including adult vaccinations.

The investigators examined Medicare enrollment and claims data to assess the change in weekly receipt of four routine adult vaccines by Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 during the pandemic: (13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV13], 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine [PPSV23], tetanus-diphtheria or tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine [Td/Tdap], and recombinant zoster vaccine [RZV]). The comparison periods were Jan. 6–July 20, 2019, and Jan. 5–July 18, 2020.

Of the Medicare enrollees in the study sample, 85% were White, 7% Black, 2% Asian, 2% Hispanic, and 4% other racial and ethnic groups. For each of the four vaccines overall, weekly rates of vaccination declined sharply after the emergency declaration, compared with corresponding weeks in 2019. In the period prior to the emergency declaration (Jan. 5–March 14, 2020), weekly percentages of Medicare beneficiaries vaccinated with PPSV23, Td/Tdap, and RZV were consistently higher than rates during the same period in 2019.

After the March 13 declaration, while weekly vaccination rates plummeted 25% for PPSV23 and 62% for RZV in the first week, the greatest weekly declines were during April 5-11, 2020, for PCV13, PPSV23, and Td/Tdap, and during April 12-18, 2020, for RZV. The pandemic weekly vaccination rate nadirs revealed declines of 88% for PCV13, 80% for PPSV23, 70% for Td/Tdap, and 89% for RZV.

Routine vaccinations increased midyear

Vaccination rates recovered gradually. For the most recently assessed pandemic week (July 12-18, 2020), the rate for PPSV23 was 8% higher than in the corresponding period in 2019. Weekly corresponding rates for other examined vaccines, however, remained much lower than in 2019: 44% lower for RZV, 24% lower for Td/Tdap and 43% lower for PCV13. The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted in June 2019 to stop recommending PCV13 for adults aged ≥65 years and so vaccination with PCV13 among this population declined in 2020, compared with that in 2019.

Another significant drop in the rates of adult vaccinations may have occurred because of the surge in COVID-19 infections in the fall of 2020 and subsequent closures and renewal of lockdown in many localities.

Disparities in routine vaccination trends

Dr. Hong and colleagues noted that their findings are consistent with prior reports of declines in pediatric vaccine ordering, administration, and coverage during the pandemic. While the reductions were similar across all racial and ethnic groups, the magnitudes of recovery varied, with vaccination rates lower among racial and ethnic minority adults than among White adults.

In view of the disproportionate COVID-19 pandemic effects among some racial and ethnic minorities, the investigators recommended monitoring and subsequent early intervention to mitigate similar indirect pandemic effects, such as reduced utilization of other preventive services. “Many members of racial and ethnic minority groups face barriers to routine medical care, which means they have fewer opportunities to receive preventive interventions such as vaccination,” Dr. Hong said in an interview. “When clinicians are following up with patients who have missed vaccinations, it is important for them to remember that patients may face new barriers to vaccination such as loss of income or health insurance, and to work with them to remove those barriers,” he added.

“If vaccination is deferred, older adults and adults with underlying medical conditions who subsequently become infected with a vaccine-preventable disease are at increased risk for complications,” Dr. Hong said. “The most important thing clinicians can do is identify patients who are due for or who have missed vaccinations, and contact them to schedule visits. Immunization Information Systems and electronic health records may be able to support this work. In addition, the vaccination status of all patients should be assessed at every health care visit to reduce missed opportunities for vaccination.”

Physicians are going to have to play catch-up when it comes to getting older patients their routine, but important, vaccinations missed during the pandemic.

and have recovered only partially and gradually, according to a report by Kai Hong, PhD, and colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “As the pandemic continues,” the investigators stated, “vaccination providers should continue efforts to resolve disruptions in routine adult vaccination.”

The CDC issued guidance recommending postponement of routine adult vaccination in response to the March 13, 2020, COVID-19 national emergency declaration by the U.S. government and also to state and local shelter-in-place orders. Health care facility operations were restricted because of safety concerns around exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The result was a significant drop in routine medical care including adult vaccinations.

The investigators examined Medicare enrollment and claims data to assess the change in weekly receipt of four routine adult vaccines by Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 during the pandemic: (13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV13], 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine [PPSV23], tetanus-diphtheria or tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine [Td/Tdap], and recombinant zoster vaccine [RZV]). The comparison periods were Jan. 6–July 20, 2019, and Jan. 5–July 18, 2020.

Of the Medicare enrollees in the study sample, 85% were White, 7% Black, 2% Asian, 2% Hispanic, and 4% other racial and ethnic groups. For each of the four vaccines overall, weekly rates of vaccination declined sharply after the emergency declaration, compared with corresponding weeks in 2019. In the period prior to the emergency declaration (Jan. 5–March 14, 2020), weekly percentages of Medicare beneficiaries vaccinated with PPSV23, Td/Tdap, and RZV were consistently higher than rates during the same period in 2019.

After the March 13 declaration, while weekly vaccination rates plummeted 25% for PPSV23 and 62% for RZV in the first week, the greatest weekly declines were during April 5-11, 2020, for PCV13, PPSV23, and Td/Tdap, and during April 12-18, 2020, for RZV. The pandemic weekly vaccination rate nadirs revealed declines of 88% for PCV13, 80% for PPSV23, 70% for Td/Tdap, and 89% for RZV.

Routine vaccinations increased midyear

Vaccination rates recovered gradually. For the most recently assessed pandemic week (July 12-18, 2020), the rate for PPSV23 was 8% higher than in the corresponding period in 2019. Weekly corresponding rates for other examined vaccines, however, remained much lower than in 2019: 44% lower for RZV, 24% lower for Td/Tdap and 43% lower for PCV13. The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted in June 2019 to stop recommending PCV13 for adults aged ≥65 years and so vaccination with PCV13 among this population declined in 2020, compared with that in 2019.

Another significant drop in the rates of adult vaccinations may have occurred because of the surge in COVID-19 infections in the fall of 2020 and subsequent closures and renewal of lockdown in many localities.

Disparities in routine vaccination trends

Dr. Hong and colleagues noted that their findings are consistent with prior reports of declines in pediatric vaccine ordering, administration, and coverage during the pandemic. While the reductions were similar across all racial and ethnic groups, the magnitudes of recovery varied, with vaccination rates lower among racial and ethnic minority adults than among White adults.

In view of the disproportionate COVID-19 pandemic effects among some racial and ethnic minorities, the investigators recommended monitoring and subsequent early intervention to mitigate similar indirect pandemic effects, such as reduced utilization of other preventive services. “Many members of racial and ethnic minority groups face barriers to routine medical care, which means they have fewer opportunities to receive preventive interventions such as vaccination,” Dr. Hong said in an interview. “When clinicians are following up with patients who have missed vaccinations, it is important for them to remember that patients may face new barriers to vaccination such as loss of income or health insurance, and to work with them to remove those barriers,” he added.

“If vaccination is deferred, older adults and adults with underlying medical conditions who subsequently become infected with a vaccine-preventable disease are at increased risk for complications,” Dr. Hong said. “The most important thing clinicians can do is identify patients who are due for or who have missed vaccinations, and contact them to schedule visits. Immunization Information Systems and electronic health records may be able to support this work. In addition, the vaccination status of all patients should be assessed at every health care visit to reduce missed opportunities for vaccination.”

Physicians are going to have to play catch-up when it comes to getting older patients their routine, but important, vaccinations missed during the pandemic.

and have recovered only partially and gradually, according to a report by Kai Hong, PhD, and colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “As the pandemic continues,” the investigators stated, “vaccination providers should continue efforts to resolve disruptions in routine adult vaccination.”

The CDC issued guidance recommending postponement of routine adult vaccination in response to the March 13, 2020, COVID-19 national emergency declaration by the U.S. government and also to state and local shelter-in-place orders. Health care facility operations were restricted because of safety concerns around exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The result was a significant drop in routine medical care including adult vaccinations.

The investigators examined Medicare enrollment and claims data to assess the change in weekly receipt of four routine adult vaccines by Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 during the pandemic: (13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV13], 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine [PPSV23], tetanus-diphtheria or tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine [Td/Tdap], and recombinant zoster vaccine [RZV]). The comparison periods were Jan. 6–July 20, 2019, and Jan. 5–July 18, 2020.

Of the Medicare enrollees in the study sample, 85% were White, 7% Black, 2% Asian, 2% Hispanic, and 4% other racial and ethnic groups. For each of the four vaccines overall, weekly rates of vaccination declined sharply after the emergency declaration, compared with corresponding weeks in 2019. In the period prior to the emergency declaration (Jan. 5–March 14, 2020), weekly percentages of Medicare beneficiaries vaccinated with PPSV23, Td/Tdap, and RZV were consistently higher than rates during the same period in 2019.

After the March 13 declaration, while weekly vaccination rates plummeted 25% for PPSV23 and 62% for RZV in the first week, the greatest weekly declines were during April 5-11, 2020, for PCV13, PPSV23, and Td/Tdap, and during April 12-18, 2020, for RZV. The pandemic weekly vaccination rate nadirs revealed declines of 88% for PCV13, 80% for PPSV23, 70% for Td/Tdap, and 89% for RZV.

Routine vaccinations increased midyear

Vaccination rates recovered gradually. For the most recently assessed pandemic week (July 12-18, 2020), the rate for PPSV23 was 8% higher than in the corresponding period in 2019. Weekly corresponding rates for other examined vaccines, however, remained much lower than in 2019: 44% lower for RZV, 24% lower for Td/Tdap and 43% lower for PCV13. The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted in June 2019 to stop recommending PCV13 for adults aged ≥65 years and so vaccination with PCV13 among this population declined in 2020, compared with that in 2019.

Another significant drop in the rates of adult vaccinations may have occurred because of the surge in COVID-19 infections in the fall of 2020 and subsequent closures and renewal of lockdown in many localities.

Disparities in routine vaccination trends

Dr. Hong and colleagues noted that their findings are consistent with prior reports of declines in pediatric vaccine ordering, administration, and coverage during the pandemic. While the reductions were similar across all racial and ethnic groups, the magnitudes of recovery varied, with vaccination rates lower among racial and ethnic minority adults than among White adults.

In view of the disproportionate COVID-19 pandemic effects among some racial and ethnic minorities, the investigators recommended monitoring and subsequent early intervention to mitigate similar indirect pandemic effects, such as reduced utilization of other preventive services. “Many members of racial and ethnic minority groups face barriers to routine medical care, which means they have fewer opportunities to receive preventive interventions such as vaccination,” Dr. Hong said in an interview. “When clinicians are following up with patients who have missed vaccinations, it is important for them to remember that patients may face new barriers to vaccination such as loss of income or health insurance, and to work with them to remove those barriers,” he added.

“If vaccination is deferred, older adults and adults with underlying medical conditions who subsequently become infected with a vaccine-preventable disease are at increased risk for complications,” Dr. Hong said. “The most important thing clinicians can do is identify patients who are due for or who have missed vaccinations, and contact them to schedule visits. Immunization Information Systems and electronic health records may be able to support this work. In addition, the vaccination status of all patients should be assessed at every health care visit to reduce missed opportunities for vaccination.”

FROM MMWR

Heart health in pregnancy tied to CV risk in adolescent offspring

Children born to mothers in poor cardiovascular health during pregnancy had an almost eight times higher risk for landing in the poorest cardiovascular health category in early adolescence than children born to mothers who had ideal cardiovascular health during pregnancy.

In an observational cohort study that involved 2,302 mother-child dyads, 6.0% of mothers and 2.6% of children were considered to be in the poorest category of cardiovascular health on the basis of specific risk factors.

The children of mothers with any “intermediate” cardiovascular health metrics in pregnancy – for example, being overweight but not obese – were at just more than two times higher risk for poor cardiovascular health in early adolescence.

Although acknowledging the limitations of observational data, Amanda M. Perak, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, suggested that focusing on whether or not the relationships seen in this study are causal might be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

“I would suggest that it may not actually matter whether there is causality or correlation here, because if you can identify newborns at birth who have an eight times higher risk for poor cardiovascular health in childhood based on mom’s health during pregnancy, that’s valuable information either way,” said Dr. Perak.

“Even if you don’t know why their risk is elevated, you might be able to target those children for more intensive preventative efforts throughout childhood to help them hold on to their cardiovascular health for longer.”

That said, she thinks it’s possible that the intrauterine environment might actually directly affect offspring health, either through epigenetics modifications to cardiometabolic regulatory genes or possibly through actual organ development. Her group is collecting epigenetic data to study this further.

“We also need to do a study to see if intervening during pregnancy with mothers leads to better cardiovascular health in offspring, and that’s a question we can answer with a clinical trial,” said Dr. Perak.

This study was published on Feb. 16, 2021, in JAMA.

Equal footing

“We’ve always talked about cardiovascular health as if everyone is born with ideal cardiovascular health and loses it from there, and I think what this article points out is that not everybody starts on equal footing,” said Stephen R. Daniels, MD, PhD, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study.

“We need to start upstream, working with mothers before and during pregnancy, but it’s also important to understand, from a pediatric standpoint, that with some of these kids the horse is kind of already out of the barn very early.”

Dr. Daniels is pediatrician in chief and chair of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

This study is the first to examine the relevance of maternal gestational cardiovascular health to offspring cardiovascular health and an important first step toward developing new approaches to address the concept of primordial prevention, he said.

“If primary prevention is identifying risk factors and treating them, I think of primordial prevention as preventing the development of those risk factors in the first place,” said Dr. Daniels.

Future trials, he added, should focus on the various mechanistic pathways – biological effects, shared genetics, and lifestyle being the options – to better understand opportunities for intervention.

Mother-child pairs

Dr. Perak and colleagues used data from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study and the HAPO Follow-up Study.

Participants were 2,302 mother-child pairs from nine field centers in Barbados, Canada, China, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the United States, and represented a racially and ethnically diverse cohort.

The mean ages were 29.6 years for pregnant mothers and 11.3 years for children. The pregnancies occurred between 2000 and 2006, and the children were examined from 2013 to 2016, when the children were aged 10-14 years.

Using the American Heart Association’s definition of cardiovascular health, the scientists categorized pregnancy health for mothers based on their measures of body mass index, blood pressure, total cholesterol, glucose level, and smoking status at 28 weeks’ gestation. These five metrics of gestational cardiovascular health have been significantly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

They categorized cardiovascular health for offspring at age 10-14 years based on four of these five metrics: body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose.

Only 32.8% of mothers and 42.2% of children had ideal cardiovascular health.

In analyses adjusted for pregnancy and birth outcomes, the associations seen between poor gestational maternal health and offspring cardiovascular health persisted but were attenuated.

Dr. Perak reported receiving grants from the Woman’s Board of Northwestern Memorial Hospital; the Dixon Family; the American Heart Association; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Daniels reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children born to mothers in poor cardiovascular health during pregnancy had an almost eight times higher risk for landing in the poorest cardiovascular health category in early adolescence than children born to mothers who had ideal cardiovascular health during pregnancy.

In an observational cohort study that involved 2,302 mother-child dyads, 6.0% of mothers and 2.6% of children were considered to be in the poorest category of cardiovascular health on the basis of specific risk factors.

The children of mothers with any “intermediate” cardiovascular health metrics in pregnancy – for example, being overweight but not obese – were at just more than two times higher risk for poor cardiovascular health in early adolescence.

Although acknowledging the limitations of observational data, Amanda M. Perak, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, suggested that focusing on whether or not the relationships seen in this study are causal might be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

“I would suggest that it may not actually matter whether there is causality or correlation here, because if you can identify newborns at birth who have an eight times higher risk for poor cardiovascular health in childhood based on mom’s health during pregnancy, that’s valuable information either way,” said Dr. Perak.

“Even if you don’t know why their risk is elevated, you might be able to target those children for more intensive preventative efforts throughout childhood to help them hold on to their cardiovascular health for longer.”

That said, she thinks it’s possible that the intrauterine environment might actually directly affect offspring health, either through epigenetics modifications to cardiometabolic regulatory genes or possibly through actual organ development. Her group is collecting epigenetic data to study this further.

“We also need to do a study to see if intervening during pregnancy with mothers leads to better cardiovascular health in offspring, and that’s a question we can answer with a clinical trial,” said Dr. Perak.

This study was published on Feb. 16, 2021, in JAMA.

Equal footing

“We’ve always talked about cardiovascular health as if everyone is born with ideal cardiovascular health and loses it from there, and I think what this article points out is that not everybody starts on equal footing,” said Stephen R. Daniels, MD, PhD, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study.

“We need to start upstream, working with mothers before and during pregnancy, but it’s also important to understand, from a pediatric standpoint, that with some of these kids the horse is kind of already out of the barn very early.”

Dr. Daniels is pediatrician in chief and chair of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

This study is the first to examine the relevance of maternal gestational cardiovascular health to offspring cardiovascular health and an important first step toward developing new approaches to address the concept of primordial prevention, he said.

“If primary prevention is identifying risk factors and treating them, I think of primordial prevention as preventing the development of those risk factors in the first place,” said Dr. Daniels.

Future trials, he added, should focus on the various mechanistic pathways – biological effects, shared genetics, and lifestyle being the options – to better understand opportunities for intervention.

Mother-child pairs

Dr. Perak and colleagues used data from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study and the HAPO Follow-up Study.

Participants were 2,302 mother-child pairs from nine field centers in Barbados, Canada, China, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the United States, and represented a racially and ethnically diverse cohort.

The mean ages were 29.6 years for pregnant mothers and 11.3 years for children. The pregnancies occurred between 2000 and 2006, and the children were examined from 2013 to 2016, when the children were aged 10-14 years.

Using the American Heart Association’s definition of cardiovascular health, the scientists categorized pregnancy health for mothers based on their measures of body mass index, blood pressure, total cholesterol, glucose level, and smoking status at 28 weeks’ gestation. These five metrics of gestational cardiovascular health have been significantly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

They categorized cardiovascular health for offspring at age 10-14 years based on four of these five metrics: body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose.

Only 32.8% of mothers and 42.2% of children had ideal cardiovascular health.

In analyses adjusted for pregnancy and birth outcomes, the associations seen between poor gestational maternal health and offspring cardiovascular health persisted but were attenuated.

Dr. Perak reported receiving grants from the Woman’s Board of Northwestern Memorial Hospital; the Dixon Family; the American Heart Association; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Daniels reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children born to mothers in poor cardiovascular health during pregnancy had an almost eight times higher risk for landing in the poorest cardiovascular health category in early adolescence than children born to mothers who had ideal cardiovascular health during pregnancy.

In an observational cohort study that involved 2,302 mother-child dyads, 6.0% of mothers and 2.6% of children were considered to be in the poorest category of cardiovascular health on the basis of specific risk factors.

The children of mothers with any “intermediate” cardiovascular health metrics in pregnancy – for example, being overweight but not obese – were at just more than two times higher risk for poor cardiovascular health in early adolescence.

Although acknowledging the limitations of observational data, Amanda M. Perak, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, suggested that focusing on whether or not the relationships seen in this study are causal might be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

“I would suggest that it may not actually matter whether there is causality or correlation here, because if you can identify newborns at birth who have an eight times higher risk for poor cardiovascular health in childhood based on mom’s health during pregnancy, that’s valuable information either way,” said Dr. Perak.

“Even if you don’t know why their risk is elevated, you might be able to target those children for more intensive preventative efforts throughout childhood to help them hold on to their cardiovascular health for longer.”

That said, she thinks it’s possible that the intrauterine environment might actually directly affect offspring health, either through epigenetics modifications to cardiometabolic regulatory genes or possibly through actual organ development. Her group is collecting epigenetic data to study this further.

“We also need to do a study to see if intervening during pregnancy with mothers leads to better cardiovascular health in offspring, and that’s a question we can answer with a clinical trial,” said Dr. Perak.

This study was published on Feb. 16, 2021, in JAMA.

Equal footing

“We’ve always talked about cardiovascular health as if everyone is born with ideal cardiovascular health and loses it from there, and I think what this article points out is that not everybody starts on equal footing,” said Stephen R. Daniels, MD, PhD, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study.

“We need to start upstream, working with mothers before and during pregnancy, but it’s also important to understand, from a pediatric standpoint, that with some of these kids the horse is kind of already out of the barn very early.”

Dr. Daniels is pediatrician in chief and chair of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

This study is the first to examine the relevance of maternal gestational cardiovascular health to offspring cardiovascular health and an important first step toward developing new approaches to address the concept of primordial prevention, he said.

“If primary prevention is identifying risk factors and treating them, I think of primordial prevention as preventing the development of those risk factors in the first place,” said Dr. Daniels.

Future trials, he added, should focus on the various mechanistic pathways – biological effects, shared genetics, and lifestyle being the options – to better understand opportunities for intervention.

Mother-child pairs

Dr. Perak and colleagues used data from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study and the HAPO Follow-up Study.

Participants were 2,302 mother-child pairs from nine field centers in Barbados, Canada, China, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the United States, and represented a racially and ethnically diverse cohort.

The mean ages were 29.6 years for pregnant mothers and 11.3 years for children. The pregnancies occurred between 2000 and 2006, and the children were examined from 2013 to 2016, when the children were aged 10-14 years.

Using the American Heart Association’s definition of cardiovascular health, the scientists categorized pregnancy health for mothers based on their measures of body mass index, blood pressure, total cholesterol, glucose level, and smoking status at 28 weeks’ gestation. These five metrics of gestational cardiovascular health have been significantly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

They categorized cardiovascular health for offspring at age 10-14 years based on four of these five metrics: body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose.

Only 32.8% of mothers and 42.2% of children had ideal cardiovascular health.

In analyses adjusted for pregnancy and birth outcomes, the associations seen between poor gestational maternal health and offspring cardiovascular health persisted but were attenuated.

Dr. Perak reported receiving grants from the Woman’s Board of Northwestern Memorial Hospital; the Dixon Family; the American Heart Association; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Daniels reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BMI, age, and sex affect COVID-19 vaccine antibody response

The capacity to mount humoral immune responses to COVID-19 vaccinations may be reduced among people who are heavier, older, and male, new findings suggest.

The data pertain specifically to the mRNA vaccine, BNT162b2, developed by BioNTech and Pfizer. The study was conducted by Italian researchers and was published Feb. 26 as a preprint.

The study involved 248 health care workers who each received two doses of the vaccine. Of the participants, 99.5% developed a humoral immune response after the second dose. Those responses varied by body mass index (BMI), age, and sex.

“The findings imply that female, lean, and young people have an increased capacity to mount humoral immune responses, compared to male, overweight, and older populations,” Raul Pellini, MD, professor at the IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, and colleagues said.

“To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze Covid-19 vaccine response in correlation to BMI,” they noted.

“Although further studies are needed, this data may have important implications to the development of vaccination strategies for COVID-19, particularly in obese people,” they wrote. If the data are confirmed by larger studies, “giving obese people an extra dose of the vaccine or a higher dose could be options to be evaluated in this population.”

Results contrast with Pfizer trials of vaccine

The BMI finding seemingly contrasts with final data from the phase 3 clinical trial of the vaccine, which were reported in a supplement to an article published Dec. 31, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine. In that study, vaccine efficacy did not differ by obesity status.

Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, professor of immunology at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an investigator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that, although the current Italian study showed somewhat lower levels of antibodies in people with obesity, compared with people who did not have obesity, the phase 3 trial found no difference in symptomatic infection rates.

“These results indicate that even with a slightly lower level of antibody induced in obese people, that level was sufficient to protect against symptomatic infection,” Dr. Iwasaki said in an interview.

Indeed, Dr. Pellini and colleagues pointed out that responses to vaccines against influenza, hepatitis B, and rabies are also reduced in those with obesity, compared with lean individuals.

However, they said, it was especially important to study the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people with obesity, because obesity is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.

“The constant state of low-grade inflammation, present in overweight people, can weaken some immune responses, including those launched by T cells, which can directly kill infected cells,” the authors noted.

Findings reported in British newspapers

The findings of the Italian study were widely covered in the lay press in the United Kingdom, with headlines such as “Pfizer Vaccine May Be Less Effective in People With Obesity, Says Study” and “Pfizer Vaccine: Overweight People Might Need Bigger Dose, Italian Study Says.” In tabloid newspapers, some headlines were slightly more stigmatizing.

The reports do stress that the Italian research was published as a preprint and has not been peer reviewed, or “is yet to be scrutinized by fellow scientists.”

Most make the point that there were only 26 people with obesity among the 248 persons in the study.

“We always knew that BMI was an enormous predictor of poor immune response to vaccines, so this paper is definitely interesting, although it is based on a rather small preliminary dataset,” Danny Altmann, PhD, a professor of immunology at Imperial College London, told the Guardian.

“It confirms that having a vaccinated population isn’t synonymous with having an immune population, especially in a country with high obesity, and emphasizes the vital need for long-term immune monitoring programs,” he added.

Antibody responses differ by BMI, age, and sex

In the Italian study, the participants – 158 women and 90 men – were assigned to receive a priming BNT162b2 vaccine dose with a booster at day 21. Blood and nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at baseline and 7 days after the second vaccine dose.

After the second dose, 99.5% of participants developed a humoral immune response; one person did not respond. None tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Titers of SARS-CoV-2–binding antibodies were greater in younger than in older participants. There were statistically significant differences between those aged 37 years and younger (453.5 AU/mL) and those aged 47-56 years (239.8 AU/mL; P = .005), those aged 37 years and younger versus those older than 56 years (453.5 vs 182.4 AU/mL; P < .0001), and those aged 37-47 years versus those older than 56 years (330.9 vs. 182.4 AU/mL; P = .01).

Antibody response was significantly greater for women than for men (338.5 vs. 212.6 AU/mL; P = .001).

Humoral responses were greater in persons of normal-weight BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2; 325.8 AU/mL) and those of underweight BMI (<18.5 kg/m2; 455.4 AU/mL), compared with persons with preobesity, defined as BMI of 25-29.9 (222.4 AU/mL), and those with obesity (BMI ≥30; 167.0 AU/mL; P < .0001). This association remained after adjustment for age (P = .003).

“Our data stresses the importance of close vaccination monitoring of obese people, considering the growing list of countries with obesity problems,” the researchers noted.

Hypertension was also associated with lower antibody titers (P = .006), but that lost statistical significance after matching for age (P = .22).

“We strongly believe that our results are extremely encouraging and useful for the scientific community,” Dr. Pellini and colleagues concluded.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Iwasaki is a cofounder of RIGImmune and is a member of its scientific advisory board.

This article was updated on 3/8/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The capacity to mount humoral immune responses to COVID-19 vaccinations may be reduced among people who are heavier, older, and male, new findings suggest.

The data pertain specifically to the mRNA vaccine, BNT162b2, developed by BioNTech and Pfizer. The study was conducted by Italian researchers and was published Feb. 26 as a preprint.

The study involved 248 health care workers who each received two doses of the vaccine. Of the participants, 99.5% developed a humoral immune response after the second dose. Those responses varied by body mass index (BMI), age, and sex.

“The findings imply that female, lean, and young people have an increased capacity to mount humoral immune responses, compared to male, overweight, and older populations,” Raul Pellini, MD, professor at the IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, and colleagues said.

“To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze Covid-19 vaccine response in correlation to BMI,” they noted.

“Although further studies are needed, this data may have important implications to the development of vaccination strategies for COVID-19, particularly in obese people,” they wrote. If the data are confirmed by larger studies, “giving obese people an extra dose of the vaccine or a higher dose could be options to be evaluated in this population.”

Results contrast with Pfizer trials of vaccine

The BMI finding seemingly contrasts with final data from the phase 3 clinical trial of the vaccine, which were reported in a supplement to an article published Dec. 31, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine. In that study, vaccine efficacy did not differ by obesity status.

Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, professor of immunology at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an investigator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that, although the current Italian study showed somewhat lower levels of antibodies in people with obesity, compared with people who did not have obesity, the phase 3 trial found no difference in symptomatic infection rates.

“These results indicate that even with a slightly lower level of antibody induced in obese people, that level was sufficient to protect against symptomatic infection,” Dr. Iwasaki said in an interview.

Indeed, Dr. Pellini and colleagues pointed out that responses to vaccines against influenza, hepatitis B, and rabies are also reduced in those with obesity, compared with lean individuals.

However, they said, it was especially important to study the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people with obesity, because obesity is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.

“The constant state of low-grade inflammation, present in overweight people, can weaken some immune responses, including those launched by T cells, which can directly kill infected cells,” the authors noted.

Findings reported in British newspapers

The findings of the Italian study were widely covered in the lay press in the United Kingdom, with headlines such as “Pfizer Vaccine May Be Less Effective in People With Obesity, Says Study” and “Pfizer Vaccine: Overweight People Might Need Bigger Dose, Italian Study Says.” In tabloid newspapers, some headlines were slightly more stigmatizing.

The reports do stress that the Italian research was published as a preprint and has not been peer reviewed, or “is yet to be scrutinized by fellow scientists.”

Most make the point that there were only 26 people with obesity among the 248 persons in the study.

“We always knew that BMI was an enormous predictor of poor immune response to vaccines, so this paper is definitely interesting, although it is based on a rather small preliminary dataset,” Danny Altmann, PhD, a professor of immunology at Imperial College London, told the Guardian.

“It confirms that having a vaccinated population isn’t synonymous with having an immune population, especially in a country with high obesity, and emphasizes the vital need for long-term immune monitoring programs,” he added.

Antibody responses differ by BMI, age, and sex

In the Italian study, the participants – 158 women and 90 men – were assigned to receive a priming BNT162b2 vaccine dose with a booster at day 21. Blood and nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at baseline and 7 days after the second vaccine dose.

After the second dose, 99.5% of participants developed a humoral immune response; one person did not respond. None tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Titers of SARS-CoV-2–binding antibodies were greater in younger than in older participants. There were statistically significant differences between those aged 37 years and younger (453.5 AU/mL) and those aged 47-56 years (239.8 AU/mL; P = .005), those aged 37 years and younger versus those older than 56 years (453.5 vs 182.4 AU/mL; P < .0001), and those aged 37-47 years versus those older than 56 years (330.9 vs. 182.4 AU/mL; P = .01).

Antibody response was significantly greater for women than for men (338.5 vs. 212.6 AU/mL; P = .001).

Humoral responses were greater in persons of normal-weight BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2; 325.8 AU/mL) and those of underweight BMI (<18.5 kg/m2; 455.4 AU/mL), compared with persons with preobesity, defined as BMI of 25-29.9 (222.4 AU/mL), and those with obesity (BMI ≥30; 167.0 AU/mL; P < .0001). This association remained after adjustment for age (P = .003).

“Our data stresses the importance of close vaccination monitoring of obese people, considering the growing list of countries with obesity problems,” the researchers noted.

Hypertension was also associated with lower antibody titers (P = .006), but that lost statistical significance after matching for age (P = .22).

“We strongly believe that our results are extremely encouraging and useful for the scientific community,” Dr. Pellini and colleagues concluded.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Iwasaki is a cofounder of RIGImmune and is a member of its scientific advisory board.

This article was updated on 3/8/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The capacity to mount humoral immune responses to COVID-19 vaccinations may be reduced among people who are heavier, older, and male, new findings suggest.

The data pertain specifically to the mRNA vaccine, BNT162b2, developed by BioNTech and Pfizer. The study was conducted by Italian researchers and was published Feb. 26 as a preprint.

The study involved 248 health care workers who each received two doses of the vaccine. Of the participants, 99.5% developed a humoral immune response after the second dose. Those responses varied by body mass index (BMI), age, and sex.

“The findings imply that female, lean, and young people have an increased capacity to mount humoral immune responses, compared to male, overweight, and older populations,” Raul Pellini, MD, professor at the IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, and colleagues said.

“To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze Covid-19 vaccine response in correlation to BMI,” they noted.

“Although further studies are needed, this data may have important implications to the development of vaccination strategies for COVID-19, particularly in obese people,” they wrote. If the data are confirmed by larger studies, “giving obese people an extra dose of the vaccine or a higher dose could be options to be evaluated in this population.”

Results contrast with Pfizer trials of vaccine

The BMI finding seemingly contrasts with final data from the phase 3 clinical trial of the vaccine, which were reported in a supplement to an article published Dec. 31, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine. In that study, vaccine efficacy did not differ by obesity status.

Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, professor of immunology at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an investigator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., noted that, although the current Italian study showed somewhat lower levels of antibodies in people with obesity, compared with people who did not have obesity, the phase 3 trial found no difference in symptomatic infection rates.

“These results indicate that even with a slightly lower level of antibody induced in obese people, that level was sufficient to protect against symptomatic infection,” Dr. Iwasaki said in an interview.

Indeed, Dr. Pellini and colleagues pointed out that responses to vaccines against influenza, hepatitis B, and rabies are also reduced in those with obesity, compared with lean individuals.

However, they said, it was especially important to study the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people with obesity, because obesity is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.

“The constant state of low-grade inflammation, present in overweight people, can weaken some immune responses, including those launched by T cells, which can directly kill infected cells,” the authors noted.

Findings reported in British newspapers

The findings of the Italian study were widely covered in the lay press in the United Kingdom, with headlines such as “Pfizer Vaccine May Be Less Effective in People With Obesity, Says Study” and “Pfizer Vaccine: Overweight People Might Need Bigger Dose, Italian Study Says.” In tabloid newspapers, some headlines were slightly more stigmatizing.

The reports do stress that the Italian research was published as a preprint and has not been peer reviewed, or “is yet to be scrutinized by fellow scientists.”

Most make the point that there were only 26 people with obesity among the 248 persons in the study.

“We always knew that BMI was an enormous predictor of poor immune response to vaccines, so this paper is definitely interesting, although it is based on a rather small preliminary dataset,” Danny Altmann, PhD, a professor of immunology at Imperial College London, told the Guardian.

“It confirms that having a vaccinated population isn’t synonymous with having an immune population, especially in a country with high obesity, and emphasizes the vital need for long-term immune monitoring programs,” he added.

Antibody responses differ by BMI, age, and sex

In the Italian study, the participants – 158 women and 90 men – were assigned to receive a priming BNT162b2 vaccine dose with a booster at day 21. Blood and nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at baseline and 7 days after the second vaccine dose.

After the second dose, 99.5% of participants developed a humoral immune response; one person did not respond. None tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Titers of SARS-CoV-2–binding antibodies were greater in younger than in older participants. There were statistically significant differences between those aged 37 years and younger (453.5 AU/mL) and those aged 47-56 years (239.8 AU/mL; P = .005), those aged 37 years and younger versus those older than 56 years (453.5 vs 182.4 AU/mL; P < .0001), and those aged 37-47 years versus those older than 56 years (330.9 vs. 182.4 AU/mL; P = .01).

Antibody response was significantly greater for women than for men (338.5 vs. 212.6 AU/mL; P = .001).

Humoral responses were greater in persons of normal-weight BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2; 325.8 AU/mL) and those of underweight BMI (<18.5 kg/m2; 455.4 AU/mL), compared with persons with preobesity, defined as BMI of 25-29.9 (222.4 AU/mL), and those with obesity (BMI ≥30; 167.0 AU/mL; P < .0001). This association remained after adjustment for age (P = .003).

“Our data stresses the importance of close vaccination monitoring of obese people, considering the growing list of countries with obesity problems,” the researchers noted.

Hypertension was also associated with lower antibody titers (P = .006), but that lost statistical significance after matching for age (P = .22).

“We strongly believe that our results are extremely encouraging and useful for the scientific community,” Dr. Pellini and colleagues concluded.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Iwasaki is a cofounder of RIGImmune and is a member of its scientific advisory board.

This article was updated on 3/8/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

JAMA podcast on racism in medicine faces backlash

Published on Feb. 23, the episode is hosted on JAMA’s learning platform for doctors and is available for continuing medical education credits.

“No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast,” JAMA wrote in a Twitter post to promote the episode. That tweet has since been deleted.

The episode features host Ed Livingston, MD, deputy editor for clinical reviews and education at JAMA, and guest Mitchell Katz, MD, president and CEO for NYC Health + Hospitals and deputy editor for JAMA Internal Medicine. Dr. Livingston approaches the episode as “structural racism for skeptics,” and Dr. Katz tries to explain how structural racism deepens health disparities and what health systems can do about it.

“Many physicians are skeptical of structural racism, the idea that economic, educational, and other societal systems preferentially disadvantage Black Americans and other communities of color,” the episode description says.

In the podcast, Dr. Livingston and Dr. Katz speak about health care disparities and racial inequality. Dr. Livingston, who says he “didn’t understand the concept” going into the episode, suggests that racism was made illegal in the 1960s and that the discussion of “structural racism” should shift away from the term “racism” and focus on socioeconomic status instead.

“What you’re talking about isn’t so much racism ... it isn’t their race, it isn’t their color, it’s their socioeconomic status,” Dr. Livingston says. “Is that a fair statement?”

But Dr. Katz says that “acknowledging structural racism can be helpful to us. Structural racism refers to a system in which policies or practices or how we look at people perpetuates racial inequality.”

Dr. Katz points to the creation of a hospital in San Francisco in the 1880s to treat patients of Chinese ethnicity separately. Outside of health care, he talks about environmental racism between neighborhoods with inequalities in hospitals, schools, and social services.

“All of those things have an impact on that minority person,” Dr. Katz says. “The big thing we can all do is move away from trying to interrogate each other’s opinions and move to a place where we are looking at the policies of our institutions and making sure that they promote equality.”

Dr. Livingston concludes the episode by reemphasizing that “racism” should be taken out of the conversation and it should instead focus on the “structural” aspect of socioeconomics.

“Minorities ... aren’t [in those neighborhoods] because they’re not allowed to buy houses or they can’t get a job because they’re Black or Hispanic. That would be illegal,” Dr. Livingston says. “But disproportionality does exist.”

Efforts to reach Dr. Livingston were unsuccessful. Dr. Katz distanced himself from Dr. Livingston in a statement released on March 4.

“Systemic and interpersonal racism both still exist in our country — they must be rooted out. I do not share the JAMA host’s belief of doing away with the word ‘racism’ will help us be more successful in ending inequities that exists across racial and ethnic lines,” Dr. Katz said. “Further, I believe that we will only produce an equitable society when social and political structures do not continue to produce and perpetuate disparate results based on social race and ethnicity.”

Dr. Katz reiterated that both interpersonal and structural racism continue to exist in the United States, “and it is woefully naive to say that no physician is a racist just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade it.”

He also recommended JAMA use this controversy “as a learning opportunity for continued dialogue and create another podcast series as an open conversation that invites diverse experts in the field to have an open discussion about structural racism in healthcare.”

The podcast and JAMA’s tweet promoting it were widely criticized on Twitter. In interviews with WebMD, many doctors expressed disbelief that such a respected journal would lend its name to this podcast episode.

B. Bobby Chiong, MD, a radiologist in New York, said although JAMA’s effort to engage with its audience about racism is laudable, it missed the mark.

“I think the backlash comes from how they tried to make a podcast about the subject and somehow made themselves an example of unconscious bias and unfamiliarity with just how embedded in our system is structural racism,” he said.

Perhaps the podcast’s worst offense was its failure to address the painful history of racial bias in this country that still permeates the medical community, says Tamara Saint-Surin, MD, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“For physicians in leadership to have the belief that structural racism does not exist in medicine, they don’t really appreciate what affects their patients and what their patients were dealing with,” Dr. Saint-Surin said in an interview. “It was a very harmful podcast and goes to show we still have so much work to do.”

Along with a flawed premise, she says, the podcast was not nearly long enough to address such a nuanced issue. And Dr. Livingston focused on interpersonal racism rather than structural racism, she said, failing to address widespread problems such as higher rates of asthma among Black populations living in areas with poor air quality.

The number of Black doctors remains low and the lack of representation adds to an environment already rife with racism, according to many medical professionals.

Shirlene Obuobi, MD, an internal medicine doctor in Chicago, said JAMA failed to live up to its own standards by publishing material that lacked research and expertise.

“I can’t submit a clinical trial to JAMA without them combing through methods with a fine-tooth comb,” Dr. Obuobi said. “They didn’t uphold the standards they normally apply to anyone else.”

Both the editor of JAMA and the head of the American Medical Association issued statements criticizing the episode and the tweet that promoted it.

JAMA Editor-in-Chief Howard Bauchner, MD, said, “The language of the tweet, and some portions of the podcast, do not reflect my commitment as editorial leader of JAMA and JAMA Network to call out and discuss the adverse effects of injustice, inequity, and racism in society and medicine as JAMA has done for many years.” He said JAMA will schedule a future podcast to address the concerns raised about the recent episode.

AMA CEO James L. Madara, MD, said, “The AMA’s House of Delegates passed policy stating that racism is structural, systemic, cultural, and interpersonal, and we are deeply disturbed – and angered – by a recent JAMA podcast that questioned the existence of structural racism and the affiliated tweet that promoted the podcast and stated ‘no physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?’ ”

He continued: “JAMA has editorial independence from AMA, but this tweet and podcast are inconsistent with the policies and views of AMA, and I’m concerned about and acknowledge the harms they have caused. Structural racism in health care and our society exists, and it is incumbent on all of us to fix it.”

This article was updated 3/5/21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Published on Feb. 23, the episode is hosted on JAMA’s learning platform for doctors and is available for continuing medical education credits.

“No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast,” JAMA wrote in a Twitter post to promote the episode. That tweet has since been deleted.

The episode features host Ed Livingston, MD, deputy editor for clinical reviews and education at JAMA, and guest Mitchell Katz, MD, president and CEO for NYC Health + Hospitals and deputy editor for JAMA Internal Medicine. Dr. Livingston approaches the episode as “structural racism for skeptics,” and Dr. Katz tries to explain how structural racism deepens health disparities and what health systems can do about it.

“Many physicians are skeptical of structural racism, the idea that economic, educational, and other societal systems preferentially disadvantage Black Americans and other communities of color,” the episode description says.

In the podcast, Dr. Livingston and Dr. Katz speak about health care disparities and racial inequality. Dr. Livingston, who says he “didn’t understand the concept” going into the episode, suggests that racism was made illegal in the 1960s and that the discussion of “structural racism” should shift away from the term “racism” and focus on socioeconomic status instead.

“What you’re talking about isn’t so much racism ... it isn’t their race, it isn’t their color, it’s their socioeconomic status,” Dr. Livingston says. “Is that a fair statement?”

But Dr. Katz says that “acknowledging structural racism can be helpful to us. Structural racism refers to a system in which policies or practices or how we look at people perpetuates racial inequality.”

Dr. Katz points to the creation of a hospital in San Francisco in the 1880s to treat patients of Chinese ethnicity separately. Outside of health care, he talks about environmental racism between neighborhoods with inequalities in hospitals, schools, and social services.

“All of those things have an impact on that minority person,” Dr. Katz says. “The big thing we can all do is move away from trying to interrogate each other’s opinions and move to a place where we are looking at the policies of our institutions and making sure that they promote equality.”

Dr. Livingston concludes the episode by reemphasizing that “racism” should be taken out of the conversation and it should instead focus on the “structural” aspect of socioeconomics.

“Minorities ... aren’t [in those neighborhoods] because they’re not allowed to buy houses or they can’t get a job because they’re Black or Hispanic. That would be illegal,” Dr. Livingston says. “But disproportionality does exist.”

Efforts to reach Dr. Livingston were unsuccessful. Dr. Katz distanced himself from Dr. Livingston in a statement released on March 4.

“Systemic and interpersonal racism both still exist in our country — they must be rooted out. I do not share the JAMA host’s belief of doing away with the word ‘racism’ will help us be more successful in ending inequities that exists across racial and ethnic lines,” Dr. Katz said. “Further, I believe that we will only produce an equitable society when social and political structures do not continue to produce and perpetuate disparate results based on social race and ethnicity.”

Dr. Katz reiterated that both interpersonal and structural racism continue to exist in the United States, “and it is woefully naive to say that no physician is a racist just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade it.”

He also recommended JAMA use this controversy “as a learning opportunity for continued dialogue and create another podcast series as an open conversation that invites diverse experts in the field to have an open discussion about structural racism in healthcare.”

The podcast and JAMA’s tweet promoting it were widely criticized on Twitter. In interviews with WebMD, many doctors expressed disbelief that such a respected journal would lend its name to this podcast episode.

B. Bobby Chiong, MD, a radiologist in New York, said although JAMA’s effort to engage with its audience about racism is laudable, it missed the mark.

“I think the backlash comes from how they tried to make a podcast about the subject and somehow made themselves an example of unconscious bias and unfamiliarity with just how embedded in our system is structural racism,” he said.

Perhaps the podcast’s worst offense was its failure to address the painful history of racial bias in this country that still permeates the medical community, says Tamara Saint-Surin, MD, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“For physicians in leadership to have the belief that structural racism does not exist in medicine, they don’t really appreciate what affects their patients and what their patients were dealing with,” Dr. Saint-Surin said in an interview. “It was a very harmful podcast and goes to show we still have so much work to do.”

Along with a flawed premise, she says, the podcast was not nearly long enough to address such a nuanced issue. And Dr. Livingston focused on interpersonal racism rather than structural racism, she said, failing to address widespread problems such as higher rates of asthma among Black populations living in areas with poor air quality.

The number of Black doctors remains low and the lack of representation adds to an environment already rife with racism, according to many medical professionals.

Shirlene Obuobi, MD, an internal medicine doctor in Chicago, said JAMA failed to live up to its own standards by publishing material that lacked research and expertise.

“I can’t submit a clinical trial to JAMA without them combing through methods with a fine-tooth comb,” Dr. Obuobi said. “They didn’t uphold the standards they normally apply to anyone else.”

Both the editor of JAMA and the head of the American Medical Association issued statements criticizing the episode and the tweet that promoted it.