User login

Comparison of Renal Function Between Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate and Other Nucleos(t)ide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors in Patients With Hepatitis B Virus Infection

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is associated with risk of potentially lethal, chronic infection and is a major public health problem. Infection from HBV has the potential to lead to liver failure, cirrhosis, and cancer.1,2 Chronic HBV infection exists in as many as 2.2 million Americans, and in 2015 alone, HBV was estimated to be associated with 887,000 deaths worldwide.1,3 Suppression of viral load is the basis of treatment, necessitating long-term use of medication for treatment.4 Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine) and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (adefovir, tenofovir), have improved the efficacy and tolerability of chronic HBV treatment compared with interferon-based agents.4-7 However, concerns remain regarding long-term risk of nephrotoxicity, in particular with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which could lead to a limitation of safe and effective options for certain populations.5,6,8 A newer formulation, tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF), has improved the kidney risks, but expense remains a limiting factor for this agent.9

Nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) have demonstrated efficacy in reducing HBV viral load and other markers of improvement in chronic HBV, but entecavir and tenofovir have tended to demonstrate greater efficacy in clinical trials.5-7 Several studies have suggested potential benefits of tenofovir-based treatment over other NRTIs, including greater viral load achievement compared with adefovir, efficacy in patients with previous failure of lamivudine or adefovir, and long-term efficacy in chronic HBV infection.10-12 A 2019 systematic review suggests TDF and TAF are more effective than other NRTIs for achieving viral load suppression.13 Other NRTIs are not without their own risks, including mitochondrial dysfunction, mostly with lamivudine and telbivudine.4

Despite these data, guidelines have varied in their treatment recommendations in the context of chronic kidney disease partly due to variations in the evidence regarding nephrotoxicity.7,14 Cohort studies and case reports have suggested association between TDF and acute kidney injury in patients with HIV infection as well as long-term reductions in kidney function.15,16 In one study, 58% of patients treated with TDF did not return to baseline kidney function after an event of acute kidney injury.17 However, little data are available on whether this association exists for chronic HBV treatment in the absence of HIV infection. One retrospective analysis comparing TDF and entecavir in chronic HBV without HIV showed greater incidence of creatinine clearance < 60 mL/min with TDF but greater incidence of serum creatinine (SCr) ≥ 2.5 mg/dL in the entacavir group, making it difficult to reach a clear conclusion on risks.18 Other studies have either suffered from small cohorts with TDF or included patients with HIV coinfection.19,20 Although a retrospective comparison of TDF and entecavir, randomly matched 1:2 to account for differences between groups, showed lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in the TDF group, more data are needed.21 Entecavir remains an option for many patient, but for those who have failed nucleosides, few options remain.

With the advantages available from TDF and the continued expense of TAF, more data regarding the risks of nephrotoxicity with TDF would be beneficial. The objective of this study was to compare treatment with TDF and other NRTIs in chronic HBV monoinfection to distinguish any differences in kidney function changes over time. With hopes of gathering enough data to distinguish between groups, information was gathered from across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system.

Methods

A nationwide, multicenter, retrospective, cohort study of veterans with HBV infection was conducted to compare the effects of various NRTIs on renal function. Patient were identified through the US Department of Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), using data from July 1, 2005 to July 31, 2015. Patients were included who had positive HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) or newly prescribed NRTI. Multiple drug episodes could be included for each patient. That is, if a patient who had previously been included had another instance of a newly prescribed NRTI, this would be included in the analysis. Exclusion criteria were patients aged < 18 years, those with NRTI prescription for ≤ 1 month, and concurrent HIV infection. All patients with HBsAg were included for the study for increasing the sensitivity in gathering patients; however, those patients were included only if they received NRTI concurrent with the laboratory test results used for the primary endpoint (ie, SCr) to be included in the analysis.

How data are received from CDW bears some explanation. A basic way to understand the way data are received is that questions can be asked such as “for X population, at this point in time, was the patient on Y drug and what was the SCr value.” Therefore, inclusion and exclusion must first be specified to define the population, after which point certain data points can be received depending on the specifications made. For this reason, there is no way to determine, for example, whether a certain patient continued TDF use for the duration of the study, only at the defined points in time (described below) to receive the specific data.

For the patients included, information was retrieved from the first receipt of the NRTI prescription to 36 months after initiation. Baseline characteristics included age, sex, race, and ethnicity, and were defined at time of NRTI initiation. Values for SCr were compared at baseline, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after prescription of NRTI. The date of laboratory results was associated with the nearest date of comparison. Values for eGFR were determined by the modification of diet in renal disease equation. Values for eGFR are available in the CDW, whereas there is no direct means to calculate creatinine clearance with the available data, so eGFR was used for this study.

The primary endpoint was a change in eGFR in patients taking TDF after adjustment for time with the full cohort. Secondary analyses included the overall effect of time for the full cohort and change in renal function for each NRTI group. Mean and standard deviation for eGFR were determined for each NRTI group using the available data points. Analyses of the primary and secondary endpoints were completed using a linear mixed model with terms for time, to account for fixed effects, and specific NRTI used to account for random effects. A 2-sided α of .05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

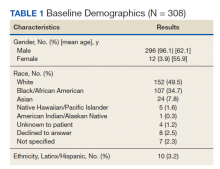

A total of 413 drug episodes from 308 subjects met inclusion criteria for the study. Of these subjects, 229 were still living at the time of query. Most study participants were male (96%), the mean age was 62.1 years for males and 55.9 years for females; 49.5% were White and 39.7% were Black veterans (Table 1).

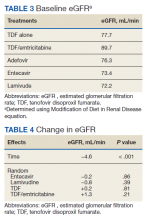

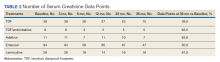

The NRTIs received by patients during the study period included TDF, TDF/emtricitabine, adefovir, entecavir, and lamivudine. No patients were on telbivudine. Formulations including TAF had not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by the end of the study period, and as such were not found in the study.13 A plurality of participants received entecavir (94 of 223 at baseline), followed by TDF (n = 38) (Table 2). Of note, only 8 participants received TDF/emtricitabine at baseline. Differences were found between the groups in number of SCr data points available at 36 months vs baseline. The TDF group had the greatest reduction in data points available with 38 laboratory values at baseline vs 15 at 36 months (39.5% of baseline). From the available data, it is not possible to determine whether these represent medication discontinuations, missing values, lost to follow-up, or some other cause. Baseline eGFR was highest in the 2 TDF groups, with TDF alone at 77.7 mL/min (1.4-5.5 mL/min higher than the nontenofovir groups) and TDF/emtricitabine at 89.7 mL/min (13.4-17.5 mL/min higher than nontenofovir groups) (Table 3).

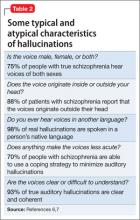

Table 4 contains data for the primarily and secondary analyses, examining change in eGFR. The fixed-effects analysis revealed a significant negative association between eGFR and time of −4.6 mL/min (P < .001) for all the NRTI groups combined. After accounting for this effect of time, there was no statistically significant correlation between use of TDF and change in eGFR (+0.2 mL/min, P = .81). For the TDF/emtricitabine group, a positive but statistically nonsignificant change was found (+1.3 mL/min, P = .21), but numbers were small and may have been insufficient to detect a difference. Similarly, no statistically significant change in eGFR was found after the fixed effects for either entecavir (−0.2 mL/min, P = .86) or lamivudine (−0.8 mL/min, P = .39). While included in the full analysis for fixed effects, random effects data were not received for the adefovir group due to heterogeneity and small quantity of the data, producing an unclear result.

Discussion

This study demonstrated a decline in eGFR over time in a similar fashion for all NRTIs used in patients treated for HBV monoinfection, but no greater decline in renal function was found with use of TDF vs other NRTIs. A statistically significant decline in eGFR of −4.55 mL/min over the 36-month time frame of the study was demonstrated for the full cohort, but no statistically significant change in eGFR was found for any individual NRTI after accounting for the fixed effect of time. If TDF is not associated with additional risk of nephrotoxicity compared with other NRTIs, this could have important implications for treatment when considering the evidence that tenofovir-based treatment seems to be more effective than other medications for suppressing viral load.13

This result runs contrary to data in patients given NRTIs for HIV infection as well as a more recent cohort study in chronic HBV infectioin, which showed a statistically significant difference in kidney dysfunction between TDF and entecavir (-15.73 vs -5.96 mL/min/m2, P < .001).5-7,21 Possible mechanism for differences in response between HIV and HBV patients has not been elucidated, but the inherent risk of developing chronic kidney disease from HIV disease may play a role.22 The possibility remains that all NRTIs cause a degree of kidney impairment in patients treated for chronic HBV infection as evidenced by the statistically significant fixed effect for time in the present study. The cause of this effect is unknown but may be independently related to HBV infection or may be specific to NRTI therapy. No control group of patients not receiving NRTI therapy was included in this study, so conclusions cannot be drawn regarding whether all NRTIs are associated with decline in renal function in chronic HBV infection.

Limitations

Although this study did not detect a difference in change in eGFR between TDF and other NRTI treatments, it is possible that the length of data collection was not adequate to account for possible kidney injury from TDF. A study assessing renal tubular dysfunction in patients receiving adefovir or TDF showed a mean onset of dysfunction of 49 months.15 It is possible that participants in this study would go on to develop renal dysfunction in the future. This potential also was observed in a more recent retrospective cohort study in chronic HBV infection, which showed the greatest degree of decline in kidney function between 36 and 48 months (−11.87 to −15.73 mL/min/m2 for the TDF group).21

The retrospective design created additional limitations. We attempted to account for some by using a matched cohort for the entecavir group, and there was no statistically significant difference between the groups in baseline characteristics. In HIV patients, a 10-year follow-up study continued to show decline in eGFR throughout the study, though the greatest degree of reduction occurred in the first year of the study.10 The higher baseline eGFR of the TDF recipients, 77.7 mL/min for the TDF alone group and 89.7 mL/min for the TDF/emtricitabine group vs 72.2 to 76.3 mL/min in the other NRTI groups, suggests high potential for selection bias. Some health care providers were likely to avoid TDF in patients with lower eGFR due to the data suggesting nephrotoxicity in other populations. Another limitation is that the reason for the missing laboratory values could not be determined. The TDF group had the greatest disparity in SCr data availability at baseline vs 36 months, with 39.5% concurrence with TDF alone compared with 50.0 to 63.6% in the other groups. Other treatment received outside the VHA system also could have influenced results.

Conclusions

This retrospective, multicenter, cohort study did not find a difference between TDF and other NRTIs for changes in renal function over time in patients with HBV infection without HIV. There was a fixed effect for time, ie, all NRTI groups showed some decline in renal function over time (−4.6 mL/min), but the effects were similar across groups. The results appear contrary to studies with comorbid HIV showing a decline in renal function with TDF, but present studies in HBV monotherapy have mixed results.

Further studies are needed to validate these results, as this and previous studies have several limitations. If these results are confirmed, a possible mechanism for these differences between patients with and without HIV should be examined. In addition, a study looking specifically at incidence of acute kidney injury rather than overall decline in renal function would add important data. If the results of this study are confirmed, there could be clinical implications in choice of agent with treatment of HBV monoinfection. This would add to the overall armament of medications available for chronic HBV infection and could create cost savings in certain situations if providers feel more comfortable continuing to use TDF instead of switching to the more expensive TAF.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Veterans Health Administration.

1. Chartier M, Maier MM, Morgan TR, et al. Achieving excellence in hepatitis B virus care for veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2018;35(suppl 2):S49-S53.

2. Chayanupatkul M, Omino R, Mittal S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;66(2):355-362. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.013

3. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report, 2017. Published April 19, 2017. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-hepatitis-report-2017

4. Kayaaslan B, Guner R. Adverse effects of oral antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(5):227-241. doi:10.4254/wjh.v9.i5.227

5. Lampertico P, Chan HL, Janssen HL, Strasser SI, Schindler R, Berg T. Review article: long-term safety of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues in HBV-monoinfected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(1):16-34. doi:10.1111/apt.13659

6. Pipili C, Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis G. Review article: nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection and chronic kidney disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(1):35-46. doi:10.1111/apt.12538

7. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261-283. doi:10.1002/hep.28156

8. Gupta SK. Tenofovir-associated Fanconi syndrome: review of the FDA adverse event reporting system. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(2):99-103. doi:10.1089/apc.2007.0052

9. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Pharmacoeconomic review teport: tenofovir alafenamide (Vemlidy): (Gilead Sciences Canada, Inc.): indication: treatment of chronic hepatitis B in adults with compensated liver disease. Published April 2018. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532825/

10. Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2442-2455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802878

11. van Bömmel F, de Man RA, Wedemeyer H, et al. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy for hepatitis B virus-monoinfected patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):73-80. doi:10.1002/hep.23246

12. Gordon SC, Krastev Z, Horban A, et al. Efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate at 240 weeks in patients with chronic hepatitis B with high baseline viral load. Hepatology. 2013;58(2):505-513. doi:10.1002/hep.26277

13. Wong WWL, Pechivanoglou P, Wong J, et al. Antiviral treatment for treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):207. Published 2019 Aug 19. doi:10.1186/s13643-019-1126-1

14. Han Y, Zeng A, Liao H, Liu Y, Chen Y, Ding H. The efficacy and safety comparison between tenofovir and entecavir in treatment of chronic hepatitis B and HBV related cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;42:168-175. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2016.11.022

15. Laprise C, Baril JG, Dufresne S, Trottier H. Association between tenofovir exposure and reduced kidney function in a cohort of HIV-positive patients: results from 10 years of follow-up. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(4):567-575. doi:10.1093/cid/cis937

16. Hall AM, Hendry BM, Nitsch D, Connolly JO. Tenofovir-associated kidney toxicity in HIV-infected patients: a review of the evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(5):773-780. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.022

17. Veiga TM, Prazeres AB, Silva D, et al. Tenofovir nephrotoxicity is an important cause of acute kidney injury in hiv infected inpatients. Abstract FR-PO481 presented at: American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week 2015; November 6, 2015; San Diego, CA.

18. Tan LK, Gilleece Y, Mandalia S, et al. Reduced glomerular filtration rate but sustained virologic response in HIV/hepatitis B co-infected individuals on long-term tenofovir. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16(7):471-478. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01084.x

19. Gish RG, Clark MD, Kane SD, Shaw RE, Mangahas MF, Baqai S. Similar risk of renal events among patients treated with tenofovir or entecavir for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(8):941-e68. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.008

20. Gara N, Zhao X, Collins MT, et al. Renal tubular dysfunction during long-term adefovir or tenofovir therapy in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(11):1317-1325. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05093.x

21. Tsai HJ, Chuang YW, Lee SW, Wu CY, Yeh HZ, Lee TY. Using the chronic kidney disease guidelines to evaluate the renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in hepatitis B patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(12):1673-1681. doi:10.1111/apt.14682

22. Szczech LA, Gupta SK, Habash R, et al. The clinical epidemiology and course of the spectrum of renal diseases associated with HIV infection. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):1145-1152. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00865.x

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is associated with risk of potentially lethal, chronic infection and is a major public health problem. Infection from HBV has the potential to lead to liver failure, cirrhosis, and cancer.1,2 Chronic HBV infection exists in as many as 2.2 million Americans, and in 2015 alone, HBV was estimated to be associated with 887,000 deaths worldwide.1,3 Suppression of viral load is the basis of treatment, necessitating long-term use of medication for treatment.4 Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine) and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (adefovir, tenofovir), have improved the efficacy and tolerability of chronic HBV treatment compared with interferon-based agents.4-7 However, concerns remain regarding long-term risk of nephrotoxicity, in particular with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which could lead to a limitation of safe and effective options for certain populations.5,6,8 A newer formulation, tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF), has improved the kidney risks, but expense remains a limiting factor for this agent.9

Nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) have demonstrated efficacy in reducing HBV viral load and other markers of improvement in chronic HBV, but entecavir and tenofovir have tended to demonstrate greater efficacy in clinical trials.5-7 Several studies have suggested potential benefits of tenofovir-based treatment over other NRTIs, including greater viral load achievement compared with adefovir, efficacy in patients with previous failure of lamivudine or adefovir, and long-term efficacy in chronic HBV infection.10-12 A 2019 systematic review suggests TDF and TAF are more effective than other NRTIs for achieving viral load suppression.13 Other NRTIs are not without their own risks, including mitochondrial dysfunction, mostly with lamivudine and telbivudine.4

Despite these data, guidelines have varied in their treatment recommendations in the context of chronic kidney disease partly due to variations in the evidence regarding nephrotoxicity.7,14 Cohort studies and case reports have suggested association between TDF and acute kidney injury in patients with HIV infection as well as long-term reductions in kidney function.15,16 In one study, 58% of patients treated with TDF did not return to baseline kidney function after an event of acute kidney injury.17 However, little data are available on whether this association exists for chronic HBV treatment in the absence of HIV infection. One retrospective analysis comparing TDF and entecavir in chronic HBV without HIV showed greater incidence of creatinine clearance < 60 mL/min with TDF but greater incidence of serum creatinine (SCr) ≥ 2.5 mg/dL in the entacavir group, making it difficult to reach a clear conclusion on risks.18 Other studies have either suffered from small cohorts with TDF or included patients with HIV coinfection.19,20 Although a retrospective comparison of TDF and entecavir, randomly matched 1:2 to account for differences between groups, showed lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in the TDF group, more data are needed.21 Entecavir remains an option for many patient, but for those who have failed nucleosides, few options remain.

With the advantages available from TDF and the continued expense of TAF, more data regarding the risks of nephrotoxicity with TDF would be beneficial. The objective of this study was to compare treatment with TDF and other NRTIs in chronic HBV monoinfection to distinguish any differences in kidney function changes over time. With hopes of gathering enough data to distinguish between groups, information was gathered from across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system.

Methods

A nationwide, multicenter, retrospective, cohort study of veterans with HBV infection was conducted to compare the effects of various NRTIs on renal function. Patient were identified through the US Department of Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), using data from July 1, 2005 to July 31, 2015. Patients were included who had positive HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) or newly prescribed NRTI. Multiple drug episodes could be included for each patient. That is, if a patient who had previously been included had another instance of a newly prescribed NRTI, this would be included in the analysis. Exclusion criteria were patients aged < 18 years, those with NRTI prescription for ≤ 1 month, and concurrent HIV infection. All patients with HBsAg were included for the study for increasing the sensitivity in gathering patients; however, those patients were included only if they received NRTI concurrent with the laboratory test results used for the primary endpoint (ie, SCr) to be included in the analysis.

How data are received from CDW bears some explanation. A basic way to understand the way data are received is that questions can be asked such as “for X population, at this point in time, was the patient on Y drug and what was the SCr value.” Therefore, inclusion and exclusion must first be specified to define the population, after which point certain data points can be received depending on the specifications made. For this reason, there is no way to determine, for example, whether a certain patient continued TDF use for the duration of the study, only at the defined points in time (described below) to receive the specific data.

For the patients included, information was retrieved from the first receipt of the NRTI prescription to 36 months after initiation. Baseline characteristics included age, sex, race, and ethnicity, and were defined at time of NRTI initiation. Values for SCr were compared at baseline, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after prescription of NRTI. The date of laboratory results was associated with the nearest date of comparison. Values for eGFR were determined by the modification of diet in renal disease equation. Values for eGFR are available in the CDW, whereas there is no direct means to calculate creatinine clearance with the available data, so eGFR was used for this study.

The primary endpoint was a change in eGFR in patients taking TDF after adjustment for time with the full cohort. Secondary analyses included the overall effect of time for the full cohort and change in renal function for each NRTI group. Mean and standard deviation for eGFR were determined for each NRTI group using the available data points. Analyses of the primary and secondary endpoints were completed using a linear mixed model with terms for time, to account for fixed effects, and specific NRTI used to account for random effects. A 2-sided α of .05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

A total of 413 drug episodes from 308 subjects met inclusion criteria for the study. Of these subjects, 229 were still living at the time of query. Most study participants were male (96%), the mean age was 62.1 years for males and 55.9 years for females; 49.5% were White and 39.7% were Black veterans (Table 1).

The NRTIs received by patients during the study period included TDF, TDF/emtricitabine, adefovir, entecavir, and lamivudine. No patients were on telbivudine. Formulations including TAF had not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by the end of the study period, and as such were not found in the study.13 A plurality of participants received entecavir (94 of 223 at baseline), followed by TDF (n = 38) (Table 2). Of note, only 8 participants received TDF/emtricitabine at baseline. Differences were found between the groups in number of SCr data points available at 36 months vs baseline. The TDF group had the greatest reduction in data points available with 38 laboratory values at baseline vs 15 at 36 months (39.5% of baseline). From the available data, it is not possible to determine whether these represent medication discontinuations, missing values, lost to follow-up, or some other cause. Baseline eGFR was highest in the 2 TDF groups, with TDF alone at 77.7 mL/min (1.4-5.5 mL/min higher than the nontenofovir groups) and TDF/emtricitabine at 89.7 mL/min (13.4-17.5 mL/min higher than nontenofovir groups) (Table 3).

Table 4 contains data for the primarily and secondary analyses, examining change in eGFR. The fixed-effects analysis revealed a significant negative association between eGFR and time of −4.6 mL/min (P < .001) for all the NRTI groups combined. After accounting for this effect of time, there was no statistically significant correlation between use of TDF and change in eGFR (+0.2 mL/min, P = .81). For the TDF/emtricitabine group, a positive but statistically nonsignificant change was found (+1.3 mL/min, P = .21), but numbers were small and may have been insufficient to detect a difference. Similarly, no statistically significant change in eGFR was found after the fixed effects for either entecavir (−0.2 mL/min, P = .86) or lamivudine (−0.8 mL/min, P = .39). While included in the full analysis for fixed effects, random effects data were not received for the adefovir group due to heterogeneity and small quantity of the data, producing an unclear result.

Discussion

This study demonstrated a decline in eGFR over time in a similar fashion for all NRTIs used in patients treated for HBV monoinfection, but no greater decline in renal function was found with use of TDF vs other NRTIs. A statistically significant decline in eGFR of −4.55 mL/min over the 36-month time frame of the study was demonstrated for the full cohort, but no statistically significant change in eGFR was found for any individual NRTI after accounting for the fixed effect of time. If TDF is not associated with additional risk of nephrotoxicity compared with other NRTIs, this could have important implications for treatment when considering the evidence that tenofovir-based treatment seems to be more effective than other medications for suppressing viral load.13

This result runs contrary to data in patients given NRTIs for HIV infection as well as a more recent cohort study in chronic HBV infectioin, which showed a statistically significant difference in kidney dysfunction between TDF and entecavir (-15.73 vs -5.96 mL/min/m2, P < .001).5-7,21 Possible mechanism for differences in response between HIV and HBV patients has not been elucidated, but the inherent risk of developing chronic kidney disease from HIV disease may play a role.22 The possibility remains that all NRTIs cause a degree of kidney impairment in patients treated for chronic HBV infection as evidenced by the statistically significant fixed effect for time in the present study. The cause of this effect is unknown but may be independently related to HBV infection or may be specific to NRTI therapy. No control group of patients not receiving NRTI therapy was included in this study, so conclusions cannot be drawn regarding whether all NRTIs are associated with decline in renal function in chronic HBV infection.

Limitations

Although this study did not detect a difference in change in eGFR between TDF and other NRTI treatments, it is possible that the length of data collection was not adequate to account for possible kidney injury from TDF. A study assessing renal tubular dysfunction in patients receiving adefovir or TDF showed a mean onset of dysfunction of 49 months.15 It is possible that participants in this study would go on to develop renal dysfunction in the future. This potential also was observed in a more recent retrospective cohort study in chronic HBV infection, which showed the greatest degree of decline in kidney function between 36 and 48 months (−11.87 to −15.73 mL/min/m2 for the TDF group).21

The retrospective design created additional limitations. We attempted to account for some by using a matched cohort for the entecavir group, and there was no statistically significant difference between the groups in baseline characteristics. In HIV patients, a 10-year follow-up study continued to show decline in eGFR throughout the study, though the greatest degree of reduction occurred in the first year of the study.10 The higher baseline eGFR of the TDF recipients, 77.7 mL/min for the TDF alone group and 89.7 mL/min for the TDF/emtricitabine group vs 72.2 to 76.3 mL/min in the other NRTI groups, suggests high potential for selection bias. Some health care providers were likely to avoid TDF in patients with lower eGFR due to the data suggesting nephrotoxicity in other populations. Another limitation is that the reason for the missing laboratory values could not be determined. The TDF group had the greatest disparity in SCr data availability at baseline vs 36 months, with 39.5% concurrence with TDF alone compared with 50.0 to 63.6% in the other groups. Other treatment received outside the VHA system also could have influenced results.

Conclusions

This retrospective, multicenter, cohort study did not find a difference between TDF and other NRTIs for changes in renal function over time in patients with HBV infection without HIV. There was a fixed effect for time, ie, all NRTI groups showed some decline in renal function over time (−4.6 mL/min), but the effects were similar across groups. The results appear contrary to studies with comorbid HIV showing a decline in renal function with TDF, but present studies in HBV monotherapy have mixed results.

Further studies are needed to validate these results, as this and previous studies have several limitations. If these results are confirmed, a possible mechanism for these differences between patients with and without HIV should be examined. In addition, a study looking specifically at incidence of acute kidney injury rather than overall decline in renal function would add important data. If the results of this study are confirmed, there could be clinical implications in choice of agent with treatment of HBV monoinfection. This would add to the overall armament of medications available for chronic HBV infection and could create cost savings in certain situations if providers feel more comfortable continuing to use TDF instead of switching to the more expensive TAF.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Veterans Health Administration.

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is associated with risk of potentially lethal, chronic infection and is a major public health problem. Infection from HBV has the potential to lead to liver failure, cirrhosis, and cancer.1,2 Chronic HBV infection exists in as many as 2.2 million Americans, and in 2015 alone, HBV was estimated to be associated with 887,000 deaths worldwide.1,3 Suppression of viral load is the basis of treatment, necessitating long-term use of medication for treatment.4 Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine) and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (adefovir, tenofovir), have improved the efficacy and tolerability of chronic HBV treatment compared with interferon-based agents.4-7 However, concerns remain regarding long-term risk of nephrotoxicity, in particular with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which could lead to a limitation of safe and effective options for certain populations.5,6,8 A newer formulation, tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF), has improved the kidney risks, but expense remains a limiting factor for this agent.9

Nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) have demonstrated efficacy in reducing HBV viral load and other markers of improvement in chronic HBV, but entecavir and tenofovir have tended to demonstrate greater efficacy in clinical trials.5-7 Several studies have suggested potential benefits of tenofovir-based treatment over other NRTIs, including greater viral load achievement compared with adefovir, efficacy in patients with previous failure of lamivudine or adefovir, and long-term efficacy in chronic HBV infection.10-12 A 2019 systematic review suggests TDF and TAF are more effective than other NRTIs for achieving viral load suppression.13 Other NRTIs are not without their own risks, including mitochondrial dysfunction, mostly with lamivudine and telbivudine.4

Despite these data, guidelines have varied in their treatment recommendations in the context of chronic kidney disease partly due to variations in the evidence regarding nephrotoxicity.7,14 Cohort studies and case reports have suggested association between TDF and acute kidney injury in patients with HIV infection as well as long-term reductions in kidney function.15,16 In one study, 58% of patients treated with TDF did not return to baseline kidney function after an event of acute kidney injury.17 However, little data are available on whether this association exists for chronic HBV treatment in the absence of HIV infection. One retrospective analysis comparing TDF and entecavir in chronic HBV without HIV showed greater incidence of creatinine clearance < 60 mL/min with TDF but greater incidence of serum creatinine (SCr) ≥ 2.5 mg/dL in the entacavir group, making it difficult to reach a clear conclusion on risks.18 Other studies have either suffered from small cohorts with TDF or included patients with HIV coinfection.19,20 Although a retrospective comparison of TDF and entecavir, randomly matched 1:2 to account for differences between groups, showed lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in the TDF group, more data are needed.21 Entecavir remains an option for many patient, but for those who have failed nucleosides, few options remain.

With the advantages available from TDF and the continued expense of TAF, more data regarding the risks of nephrotoxicity with TDF would be beneficial. The objective of this study was to compare treatment with TDF and other NRTIs in chronic HBV monoinfection to distinguish any differences in kidney function changes over time. With hopes of gathering enough data to distinguish between groups, information was gathered from across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system.

Methods

A nationwide, multicenter, retrospective, cohort study of veterans with HBV infection was conducted to compare the effects of various NRTIs on renal function. Patient were identified through the US Department of Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), using data from July 1, 2005 to July 31, 2015. Patients were included who had positive HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) or newly prescribed NRTI. Multiple drug episodes could be included for each patient. That is, if a patient who had previously been included had another instance of a newly prescribed NRTI, this would be included in the analysis. Exclusion criteria were patients aged < 18 years, those with NRTI prescription for ≤ 1 month, and concurrent HIV infection. All patients with HBsAg were included for the study for increasing the sensitivity in gathering patients; however, those patients were included only if they received NRTI concurrent with the laboratory test results used for the primary endpoint (ie, SCr) to be included in the analysis.

How data are received from CDW bears some explanation. A basic way to understand the way data are received is that questions can be asked such as “for X population, at this point in time, was the patient on Y drug and what was the SCr value.” Therefore, inclusion and exclusion must first be specified to define the population, after which point certain data points can be received depending on the specifications made. For this reason, there is no way to determine, for example, whether a certain patient continued TDF use for the duration of the study, only at the defined points in time (described below) to receive the specific data.

For the patients included, information was retrieved from the first receipt of the NRTI prescription to 36 months after initiation. Baseline characteristics included age, sex, race, and ethnicity, and were defined at time of NRTI initiation. Values for SCr were compared at baseline, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after prescription of NRTI. The date of laboratory results was associated with the nearest date of comparison. Values for eGFR were determined by the modification of diet in renal disease equation. Values for eGFR are available in the CDW, whereas there is no direct means to calculate creatinine clearance with the available data, so eGFR was used for this study.

The primary endpoint was a change in eGFR in patients taking TDF after adjustment for time with the full cohort. Secondary analyses included the overall effect of time for the full cohort and change in renal function for each NRTI group. Mean and standard deviation for eGFR were determined for each NRTI group using the available data points. Analyses of the primary and secondary endpoints were completed using a linear mixed model with terms for time, to account for fixed effects, and specific NRTI used to account for random effects. A 2-sided α of .05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

A total of 413 drug episodes from 308 subjects met inclusion criteria for the study. Of these subjects, 229 were still living at the time of query. Most study participants were male (96%), the mean age was 62.1 years for males and 55.9 years for females; 49.5% were White and 39.7% were Black veterans (Table 1).

The NRTIs received by patients during the study period included TDF, TDF/emtricitabine, adefovir, entecavir, and lamivudine. No patients were on telbivudine. Formulations including TAF had not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by the end of the study period, and as such were not found in the study.13 A plurality of participants received entecavir (94 of 223 at baseline), followed by TDF (n = 38) (Table 2). Of note, only 8 participants received TDF/emtricitabine at baseline. Differences were found between the groups in number of SCr data points available at 36 months vs baseline. The TDF group had the greatest reduction in data points available with 38 laboratory values at baseline vs 15 at 36 months (39.5% of baseline). From the available data, it is not possible to determine whether these represent medication discontinuations, missing values, lost to follow-up, or some other cause. Baseline eGFR was highest in the 2 TDF groups, with TDF alone at 77.7 mL/min (1.4-5.5 mL/min higher than the nontenofovir groups) and TDF/emtricitabine at 89.7 mL/min (13.4-17.5 mL/min higher than nontenofovir groups) (Table 3).

Table 4 contains data for the primarily and secondary analyses, examining change in eGFR. The fixed-effects analysis revealed a significant negative association between eGFR and time of −4.6 mL/min (P < .001) for all the NRTI groups combined. After accounting for this effect of time, there was no statistically significant correlation between use of TDF and change in eGFR (+0.2 mL/min, P = .81). For the TDF/emtricitabine group, a positive but statistically nonsignificant change was found (+1.3 mL/min, P = .21), but numbers were small and may have been insufficient to detect a difference. Similarly, no statistically significant change in eGFR was found after the fixed effects for either entecavir (−0.2 mL/min, P = .86) or lamivudine (−0.8 mL/min, P = .39). While included in the full analysis for fixed effects, random effects data were not received for the adefovir group due to heterogeneity and small quantity of the data, producing an unclear result.

Discussion

This study demonstrated a decline in eGFR over time in a similar fashion for all NRTIs used in patients treated for HBV monoinfection, but no greater decline in renal function was found with use of TDF vs other NRTIs. A statistically significant decline in eGFR of −4.55 mL/min over the 36-month time frame of the study was demonstrated for the full cohort, but no statistically significant change in eGFR was found for any individual NRTI after accounting for the fixed effect of time. If TDF is not associated with additional risk of nephrotoxicity compared with other NRTIs, this could have important implications for treatment when considering the evidence that tenofovir-based treatment seems to be more effective than other medications for suppressing viral load.13

This result runs contrary to data in patients given NRTIs for HIV infection as well as a more recent cohort study in chronic HBV infectioin, which showed a statistically significant difference in kidney dysfunction between TDF and entecavir (-15.73 vs -5.96 mL/min/m2, P < .001).5-7,21 Possible mechanism for differences in response between HIV and HBV patients has not been elucidated, but the inherent risk of developing chronic kidney disease from HIV disease may play a role.22 The possibility remains that all NRTIs cause a degree of kidney impairment in patients treated for chronic HBV infection as evidenced by the statistically significant fixed effect for time in the present study. The cause of this effect is unknown but may be independently related to HBV infection or may be specific to NRTI therapy. No control group of patients not receiving NRTI therapy was included in this study, so conclusions cannot be drawn regarding whether all NRTIs are associated with decline in renal function in chronic HBV infection.

Limitations

Although this study did not detect a difference in change in eGFR between TDF and other NRTI treatments, it is possible that the length of data collection was not adequate to account for possible kidney injury from TDF. A study assessing renal tubular dysfunction in patients receiving adefovir or TDF showed a mean onset of dysfunction of 49 months.15 It is possible that participants in this study would go on to develop renal dysfunction in the future. This potential also was observed in a more recent retrospective cohort study in chronic HBV infection, which showed the greatest degree of decline in kidney function between 36 and 48 months (−11.87 to −15.73 mL/min/m2 for the TDF group).21

The retrospective design created additional limitations. We attempted to account for some by using a matched cohort for the entecavir group, and there was no statistically significant difference between the groups in baseline characteristics. In HIV patients, a 10-year follow-up study continued to show decline in eGFR throughout the study, though the greatest degree of reduction occurred in the first year of the study.10 The higher baseline eGFR of the TDF recipients, 77.7 mL/min for the TDF alone group and 89.7 mL/min for the TDF/emtricitabine group vs 72.2 to 76.3 mL/min in the other NRTI groups, suggests high potential for selection bias. Some health care providers were likely to avoid TDF in patients with lower eGFR due to the data suggesting nephrotoxicity in other populations. Another limitation is that the reason for the missing laboratory values could not be determined. The TDF group had the greatest disparity in SCr data availability at baseline vs 36 months, with 39.5% concurrence with TDF alone compared with 50.0 to 63.6% in the other groups. Other treatment received outside the VHA system also could have influenced results.

Conclusions

This retrospective, multicenter, cohort study did not find a difference between TDF and other NRTIs for changes in renal function over time in patients with HBV infection without HIV. There was a fixed effect for time, ie, all NRTI groups showed some decline in renal function over time (−4.6 mL/min), but the effects were similar across groups. The results appear contrary to studies with comorbid HIV showing a decline in renal function with TDF, but present studies in HBV monotherapy have mixed results.

Further studies are needed to validate these results, as this and previous studies have several limitations. If these results are confirmed, a possible mechanism for these differences between patients with and without HIV should be examined. In addition, a study looking specifically at incidence of acute kidney injury rather than overall decline in renal function would add important data. If the results of this study are confirmed, there could be clinical implications in choice of agent with treatment of HBV monoinfection. This would add to the overall armament of medications available for chronic HBV infection and could create cost savings in certain situations if providers feel more comfortable continuing to use TDF instead of switching to the more expensive TAF.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Veterans Health Administration.

1. Chartier M, Maier MM, Morgan TR, et al. Achieving excellence in hepatitis B virus care for veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2018;35(suppl 2):S49-S53.

2. Chayanupatkul M, Omino R, Mittal S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;66(2):355-362. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.013

3. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report, 2017. Published April 19, 2017. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-hepatitis-report-2017

4. Kayaaslan B, Guner R. Adverse effects of oral antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(5):227-241. doi:10.4254/wjh.v9.i5.227

5. Lampertico P, Chan HL, Janssen HL, Strasser SI, Schindler R, Berg T. Review article: long-term safety of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues in HBV-monoinfected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(1):16-34. doi:10.1111/apt.13659

6. Pipili C, Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis G. Review article: nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection and chronic kidney disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(1):35-46. doi:10.1111/apt.12538

7. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261-283. doi:10.1002/hep.28156

8. Gupta SK. Tenofovir-associated Fanconi syndrome: review of the FDA adverse event reporting system. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(2):99-103. doi:10.1089/apc.2007.0052

9. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Pharmacoeconomic review teport: tenofovir alafenamide (Vemlidy): (Gilead Sciences Canada, Inc.): indication: treatment of chronic hepatitis B in adults with compensated liver disease. Published April 2018. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532825/

10. Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2442-2455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802878

11. van Bömmel F, de Man RA, Wedemeyer H, et al. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy for hepatitis B virus-monoinfected patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):73-80. doi:10.1002/hep.23246

12. Gordon SC, Krastev Z, Horban A, et al. Efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate at 240 weeks in patients with chronic hepatitis B with high baseline viral load. Hepatology. 2013;58(2):505-513. doi:10.1002/hep.26277

13. Wong WWL, Pechivanoglou P, Wong J, et al. Antiviral treatment for treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):207. Published 2019 Aug 19. doi:10.1186/s13643-019-1126-1

14. Han Y, Zeng A, Liao H, Liu Y, Chen Y, Ding H. The efficacy and safety comparison between tenofovir and entecavir in treatment of chronic hepatitis B and HBV related cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;42:168-175. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2016.11.022

15. Laprise C, Baril JG, Dufresne S, Trottier H. Association between tenofovir exposure and reduced kidney function in a cohort of HIV-positive patients: results from 10 years of follow-up. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(4):567-575. doi:10.1093/cid/cis937

16. Hall AM, Hendry BM, Nitsch D, Connolly JO. Tenofovir-associated kidney toxicity in HIV-infected patients: a review of the evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(5):773-780. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.022

17. Veiga TM, Prazeres AB, Silva D, et al. Tenofovir nephrotoxicity is an important cause of acute kidney injury in hiv infected inpatients. Abstract FR-PO481 presented at: American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week 2015; November 6, 2015; San Diego, CA.

18. Tan LK, Gilleece Y, Mandalia S, et al. Reduced glomerular filtration rate but sustained virologic response in HIV/hepatitis B co-infected individuals on long-term tenofovir. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16(7):471-478. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01084.x

19. Gish RG, Clark MD, Kane SD, Shaw RE, Mangahas MF, Baqai S. Similar risk of renal events among patients treated with tenofovir or entecavir for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(8):941-e68. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.008

20. Gara N, Zhao X, Collins MT, et al. Renal tubular dysfunction during long-term adefovir or tenofovir therapy in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(11):1317-1325. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05093.x

21. Tsai HJ, Chuang YW, Lee SW, Wu CY, Yeh HZ, Lee TY. Using the chronic kidney disease guidelines to evaluate the renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in hepatitis B patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(12):1673-1681. doi:10.1111/apt.14682

22. Szczech LA, Gupta SK, Habash R, et al. The clinical epidemiology and course of the spectrum of renal diseases associated with HIV infection. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):1145-1152. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00865.x

1. Chartier M, Maier MM, Morgan TR, et al. Achieving excellence in hepatitis B virus care for veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2018;35(suppl 2):S49-S53.

2. Chayanupatkul M, Omino R, Mittal S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;66(2):355-362. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.013

3. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report, 2017. Published April 19, 2017. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-hepatitis-report-2017

4. Kayaaslan B, Guner R. Adverse effects of oral antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(5):227-241. doi:10.4254/wjh.v9.i5.227

5. Lampertico P, Chan HL, Janssen HL, Strasser SI, Schindler R, Berg T. Review article: long-term safety of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues in HBV-monoinfected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(1):16-34. doi:10.1111/apt.13659

6. Pipili C, Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis G. Review article: nucleos(t)ide analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection and chronic kidney disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(1):35-46. doi:10.1111/apt.12538

7. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261-283. doi:10.1002/hep.28156

8. Gupta SK. Tenofovir-associated Fanconi syndrome: review of the FDA adverse event reporting system. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(2):99-103. doi:10.1089/apc.2007.0052

9. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Pharmacoeconomic review teport: tenofovir alafenamide (Vemlidy): (Gilead Sciences Canada, Inc.): indication: treatment of chronic hepatitis B in adults with compensated liver disease. Published April 2018. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532825/

10. Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2442-2455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802878

11. van Bömmel F, de Man RA, Wedemeyer H, et al. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy for hepatitis B virus-monoinfected patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):73-80. doi:10.1002/hep.23246

12. Gordon SC, Krastev Z, Horban A, et al. Efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate at 240 weeks in patients with chronic hepatitis B with high baseline viral load. Hepatology. 2013;58(2):505-513. doi:10.1002/hep.26277

13. Wong WWL, Pechivanoglou P, Wong J, et al. Antiviral treatment for treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):207. Published 2019 Aug 19. doi:10.1186/s13643-019-1126-1

14. Han Y, Zeng A, Liao H, Liu Y, Chen Y, Ding H. The efficacy and safety comparison between tenofovir and entecavir in treatment of chronic hepatitis B and HBV related cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;42:168-175. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2016.11.022

15. Laprise C, Baril JG, Dufresne S, Trottier H. Association between tenofovir exposure and reduced kidney function in a cohort of HIV-positive patients: results from 10 years of follow-up. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(4):567-575. doi:10.1093/cid/cis937

16. Hall AM, Hendry BM, Nitsch D, Connolly JO. Tenofovir-associated kidney toxicity in HIV-infected patients: a review of the evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(5):773-780. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.022

17. Veiga TM, Prazeres AB, Silva D, et al. Tenofovir nephrotoxicity is an important cause of acute kidney injury in hiv infected inpatients. Abstract FR-PO481 presented at: American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week 2015; November 6, 2015; San Diego, CA.

18. Tan LK, Gilleece Y, Mandalia S, et al. Reduced glomerular filtration rate but sustained virologic response in HIV/hepatitis B co-infected individuals on long-term tenofovir. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16(7):471-478. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01084.x

19. Gish RG, Clark MD, Kane SD, Shaw RE, Mangahas MF, Baqai S. Similar risk of renal events among patients treated with tenofovir or entecavir for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(8):941-e68. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.008

20. Gara N, Zhao X, Collins MT, et al. Renal tubular dysfunction during long-term adefovir or tenofovir therapy in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(11):1317-1325. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05093.x

21. Tsai HJ, Chuang YW, Lee SW, Wu CY, Yeh HZ, Lee TY. Using the chronic kidney disease guidelines to evaluate the renal safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in hepatitis B patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(12):1673-1681. doi:10.1111/apt.14682

22. Szczech LA, Gupta SK, Habash R, et al. The clinical epidemiology and course of the spectrum of renal diseases associated with HIV infection. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):1145-1152. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00865.x

Take caution: Look for DISTURBED behaviors when you assess violence risk

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

Take caution: Look for DISTURBED behaviors when you assess violence risk

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.