User login

“Will this patient turn violent?” Psychiatrists face this tough question every day. Although predicting a complex behavior such as violence is nearly impossible, we can prepare for dangerous behavior and improve our safety by:

- knowing the risk factors for patient violence

- assessing individuals for violence potential before clinical encounters

- controlling situations to reduce injury risk.

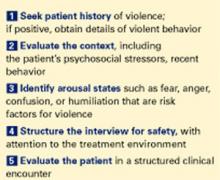

In one study, more than 50% of psychiatrists and 75% of mental health nurses reported an act or threat of violence from patients within the past year.1 To help you avoid becoming a statistic, this article provides a 5-step procedure (Figure 1). to quickly assess and respond to risk of violence in a psychiatric patient.

Step 1: Seek patient history

A careful review of past events and those immediately preceding the clinical encounter is the best tool for assessing potential for violence. The more you can learn from the patient chart and other sources before you see the patient, the better (Table 1). Valuable clues can be obtained from interviews with family members, outpatient providers, police officers, and others who have had pertinent social contact with the patient.

Figure 5 steps to assess and reduce the risk of patient violence

Past violence is the most powerful predictor of future violence, according to published studies. Higher frequency of aggressive episodes, greater degree of aggressive injury, and lack of apparent provocation in past episodes all increase the violence risk.3

A minority of patients account for most aggressive acts in clinical encounters. One study showed that recidivists committed 53% of all violent behaviors in a health care setting.4 A patient’s history of violence should be flagged in the chart and verbally passed on to staff to alert providers of increased risk.

However, not having a violent history does not guarantee that a patient will not become dangerous during a clinical encounter. All patients with a violent past had an initial violent episode, and that first time can occur in a practice setting.

Psychotic states by themselves appear to increase the risk of violence, although the literature is mixed.5,6 Clearly, however, psychotic states associated with arousal or agitation do predispose patients to violence, especially if the psychosis involves active paranoid delusions or hallucinations associated with negative affect (anger, sadness, anxiety).7

Increased rates of violence have also been reported in psychiatric patients with:

- acute manic states associated with arousal or agitation8

- nonspecific neurologic abnormalities such as abnormal EEGs, localizing neurologic signs, or “soft signs” (impaired face-hand test, graphesthesia, stereognosis).9

Demographic variables associated with higher violence rates include ages 15 to 24, nonwhite race, male gender, poverty, and low educational level. Other variables include history of abuse, victimization, family violence, limited employment skills, and “rootlessness,” such as poor family network and frequent moves or job changes.10

Psychiatric diagnoses associated with increased risk of violence include schizophrenia, bipolar mania, alcohol and other substance abuse, and personality disorders.11-13 In clinical practice, however, I find psychiatric diagnoses less useful in predicting violence than the patient’s arousal state and the other risk factors discussed above.

Step 2: Evaluate the context

In addition to evidence-supported risk factors (Table 2), context—or the broader situation in which a patient is embedded at the time of psychiatric evaluation—plays a prominent role in potentially violent situations. For example, if “divorce” is listed as a presenting factor:

- Is the patient recently divorced, or did it occur years ago?

- Does he hate all women or just his ex-wife?

- Was she having an affair, and did he just learn about this?

In other words, environmental stresses can be acute and destabilizing or part of the patient’s chronic life picture and serve in homeostatic functioning.

Step 3: Identify arousal states

Patients rarely commit violent acts when their anxiety and moods are well controlled. They are more likely to become aggressive in high arousal states.

Fear is probably an element of most situations where patients act out violently. Because the fearful patient may not exhibit easily interpreted danger signals, however, you may unwittingly provoke an assault by violating his or her personal space. A fearful, paranoid patient requires a greater-than-usual “intimate zone,” although this need for increased space may not be obvious.

Minimize provocation by explaining your actions and behaviors in advance (such as, “I would like to enter the room, sit down, and talk with you for about 20 minutes”). Be business-like with paranoid patients. Avoid exuding warmth, as they may view attempts at warmth as having sinister intent.

Clinicians are sometimes injured when trying to prevent a fearful, paranoid patient from fleeing. To avoid injury, don’t stand between the patient and the door. Let the patient escape from the immediate situation, and enlist security or police in further intervention attempts.

Anger is easy to recognize by signs of mounting tension. Loud voice, inappropriate staring, banging objects, clenched fists, agitated pacing, and verbal threats are common in the angry patient before a violent episode. Although this seems self-evident, it is surprising how many violent acts occur when these signs are obvious and noted by staff, yet no de-escalation measures are taken.

A patient’s verbal threats can actually help the clinician. This “red flag” alerts staff to focus on de-escalation techniques and prepare for a violent situation.

Confusion can be an underlying risk factor in patients with delirium or nonspecific organic brain syndrome. These patients may strike out unexpectedly when health care personnel are attempting to do routine procedures, and clinicians are sometimes caught off-guard when operating in a care-giving rather than defensive mode.

Table 1

Will this patient become violent? Questions to consider before a clinical encounter

Long-term behavior

|

Immediate situation

|

Clinicians can often avoid arousing confused patients by using orienting techniques and explaining their actions. For example, a nurse might say, “Hello Mr. X, I am a nurse and you are in this hospital for treatment of your illness. I will need to use this machine to check your blood pressure.”

Humiliation. Men in particular can react aggressively to loss of self-esteem and feelings of powerlessness. Take note if a man has been humiliated in front of family before being brought for evaluation; for example, was he removed by police in an emergency detention situation? This patient may need to act out violently to restore his sense of self.

Staff can lessen a patient’s potential to act on humiliation by using a therapeutic, esteem-building interview technique. For example, address the patient as “Mr.” instead of by first name, and highlight his strengths or accomplishments early in the interview.

Table 2

Risk factors for violence among psychiatric patients*

|

| * As identified in the literature. |

Step 4: Structure the interview for safety

The time you take before an interview to learn about a patient’s violence history, context, and arousal state is time well-spent and more patient-specific than past diagnoses. This information allows you to prepare for a safe intervention.

Interview environment. The physical and social environment where you interview the patient may contribute to violence potential.

- Is the patient being interviewed in a cramped room or an open hallway?

- Is the evaluation unit overcrowded?

- Are security personnel visible?

- Is the examiner of the same race or ethnic background as the patient?

Cramped and overcrowded conditions on a psychiatric ward have been associated with higher rates of patient violence.2 In one case of context-specific violence, a veteran with known institutional transference issues toward the government attacked providers in a VA hospital on several occasions but did not exhibit this behavior in other, non-VA medical settings.

Take control of the interview and treatment situation. Use the physical space and personnel as you would any other intervention tool—to increase safety and decrease potential for violent behavior. For example, some patients do better when interviewed in a small, private setting. Other interviews must be conducted in a triage area while police escorts hold the patient and handcuffs remain on.

Ideally, you and the patient should have equal access to the door if you conduct the psychiatric interview in an enclosed room. With high-risk patients, arrange your seating at a 90-degree angle—rather than face-to-face—to limit sustained, confrontational eye contact. Sit at greater than an arm swing or leg kick away from the patient, and require him or her to remain seated during the interview (or you will promptly leave).

In the outpatient practice, terminate the interview or evaluation session if a patient in a negative affective arousal state does not allow verbal redirection. Before you make any movement to exit, however, announce, “I am leaving the room now.”

Trust your intuition. I do not enter a closed, private space with a patient unless I feel safe. If I feel afraid, I take that as a valuable warning that further safety measures are necessary.

Use restraints as needed. When patients with a history of violence are brought to the hospital in high arousal states, I let them remain in restraint with security present during the initial interview. If the patient cannot have a back-and-forth conversation with me, I keep the security force present until I believe my verbal interactions have a substantial effect.

Patients must be responsive to talking interventions before restraint, security, or other environmental safety measures are removed. Some patients do not reach this point until after tranquilizing medications are given.

Step 5: Tthe clinical encounter

When discussing how to assess the likelihood of patient violence during a clinical encounter, a psychiatric colleague once commented, “Risk factors make you worry more; nothing makes you worry less.”

In other words, keep your guard up. Let clinical judgment take precedence over statistics when you are evaluating any patient. Statistics represent frequencies or averages; they may or may not apply to any one individual.

Techniques for assessing and treating violent patients are beyond the scope of this article, but at the very least:

- obtain training in safety/treatment protocols for violent patients

- ensure that your hospital/clinic has procedures in place to improve safety and to handle violent situations.

Visible, high numbers of confident-appearing—but not confrontational—staff or security may dissuade the patient from acting out. Then, most often, force will not be needed. If force is needed to control a violent patient, make sure the staff’s response is strong and overwhelming.

For every violent act requiring staff intervention, automatically schedule a debriefing session for those involved to assess the incident and allow them to express their feelings.

Related resources

- American Association for Emergency Psychiatry. www.emergencypsychiatry.org

- Volavka J. The neurobiology of violence: an update. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;11:307-14.

- McNiel DE, Eisner JP, Binder RL. The relationship between command hallucinations and violence. Psychiatric Services 2000;51:1288-92.

1. Nolan P, Dallender J, Soares J, et al. Violence in mental health care: the experiences of mental health nurses and psychiatrists. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:934-41.

2. Blomhoff S, Seim S, Friis S. Can prediction of violence among psychiatric inpatients be improved? Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:771-5.

3. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al. Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1112-5.

4. Taylor P. Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:491-8.

5. Junginger J, Parks-Levy J, McGuire L. Delusions and symptom-consistent violence. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:218-20.

6. Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley K, et al. Violence in schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Res 1997;26:181-90.

7. Binder R, McNiel D. Effects of diagnosis and context on dangerousness. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:728-32.

8. Convit A, Jaeger J, Pin Lin S, et al. Predicting assaultiveness in psychiatric inpatients: A pilot study. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1988;39:429-34.

9. Hyman S. The violent patient. In: Hyman S (ed). Manual of psychiatric emergencies. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1988;23-31.

10. Swartz M, Swanson J, Hiday V, et al. Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:226-31.

11. Owen C, Tarantello C, Jones M, et al. Repetitively violent patients in psychiatric units. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:1458-61.

12. Citrome L, Volavka J. Clinical management of persistent aggressive behavior in schizophrenia, part I. Definitions, epidemiology, assessment and acute treatment. Essen Psychopharmacol 2002;5:1-16.

13. Abeyasinghe R, Jayasekera R. Violence in a general hospital psychiatry unit for men. Ceylon Med J 2003;48(2):45-7.

“Will this patient turn violent?” Psychiatrists face this tough question every day. Although predicting a complex behavior such as violence is nearly impossible, we can prepare for dangerous behavior and improve our safety by:

- knowing the risk factors for patient violence

- assessing individuals for violence potential before clinical encounters

- controlling situations to reduce injury risk.

In one study, more than 50% of psychiatrists and 75% of mental health nurses reported an act or threat of violence from patients within the past year.1 To help you avoid becoming a statistic, this article provides a 5-step procedure (Figure 1). to quickly assess and respond to risk of violence in a psychiatric patient.

Step 1: Seek patient history

A careful review of past events and those immediately preceding the clinical encounter is the best tool for assessing potential for violence. The more you can learn from the patient chart and other sources before you see the patient, the better (Table 1). Valuable clues can be obtained from interviews with family members, outpatient providers, police officers, and others who have had pertinent social contact with the patient.

Figure 5 steps to assess and reduce the risk of patient violence

Past violence is the most powerful predictor of future violence, according to published studies. Higher frequency of aggressive episodes, greater degree of aggressive injury, and lack of apparent provocation in past episodes all increase the violence risk.3

A minority of patients account for most aggressive acts in clinical encounters. One study showed that recidivists committed 53% of all violent behaviors in a health care setting.4 A patient’s history of violence should be flagged in the chart and verbally passed on to staff to alert providers of increased risk.

However, not having a violent history does not guarantee that a patient will not become dangerous during a clinical encounter. All patients with a violent past had an initial violent episode, and that first time can occur in a practice setting.

Psychotic states by themselves appear to increase the risk of violence, although the literature is mixed.5,6 Clearly, however, psychotic states associated with arousal or agitation do predispose patients to violence, especially if the psychosis involves active paranoid delusions or hallucinations associated with negative affect (anger, sadness, anxiety).7

Increased rates of violence have also been reported in psychiatric patients with:

- acute manic states associated with arousal or agitation8

- nonspecific neurologic abnormalities such as abnormal EEGs, localizing neurologic signs, or “soft signs” (impaired face-hand test, graphesthesia, stereognosis).9

Demographic variables associated with higher violence rates include ages 15 to 24, nonwhite race, male gender, poverty, and low educational level. Other variables include history of abuse, victimization, family violence, limited employment skills, and “rootlessness,” such as poor family network and frequent moves or job changes.10

Psychiatric diagnoses associated with increased risk of violence include schizophrenia, bipolar mania, alcohol and other substance abuse, and personality disorders.11-13 In clinical practice, however, I find psychiatric diagnoses less useful in predicting violence than the patient’s arousal state and the other risk factors discussed above.

Step 2: Evaluate the context

In addition to evidence-supported risk factors (Table 2), context—or the broader situation in which a patient is embedded at the time of psychiatric evaluation—plays a prominent role in potentially violent situations. For example, if “divorce” is listed as a presenting factor:

- Is the patient recently divorced, or did it occur years ago?

- Does he hate all women or just his ex-wife?

- Was she having an affair, and did he just learn about this?

In other words, environmental stresses can be acute and destabilizing or part of the patient’s chronic life picture and serve in homeostatic functioning.

Step 3: Identify arousal states

Patients rarely commit violent acts when their anxiety and moods are well controlled. They are more likely to become aggressive in high arousal states.

Fear is probably an element of most situations where patients act out violently. Because the fearful patient may not exhibit easily interpreted danger signals, however, you may unwittingly provoke an assault by violating his or her personal space. A fearful, paranoid patient requires a greater-than-usual “intimate zone,” although this need for increased space may not be obvious.

Minimize provocation by explaining your actions and behaviors in advance (such as, “I would like to enter the room, sit down, and talk with you for about 20 minutes”). Be business-like with paranoid patients. Avoid exuding warmth, as they may view attempts at warmth as having sinister intent.

Clinicians are sometimes injured when trying to prevent a fearful, paranoid patient from fleeing. To avoid injury, don’t stand between the patient and the door. Let the patient escape from the immediate situation, and enlist security or police in further intervention attempts.

Anger is easy to recognize by signs of mounting tension. Loud voice, inappropriate staring, banging objects, clenched fists, agitated pacing, and verbal threats are common in the angry patient before a violent episode. Although this seems self-evident, it is surprising how many violent acts occur when these signs are obvious and noted by staff, yet no de-escalation measures are taken.

A patient’s verbal threats can actually help the clinician. This “red flag” alerts staff to focus on de-escalation techniques and prepare for a violent situation.

Confusion can be an underlying risk factor in patients with delirium or nonspecific organic brain syndrome. These patients may strike out unexpectedly when health care personnel are attempting to do routine procedures, and clinicians are sometimes caught off-guard when operating in a care-giving rather than defensive mode.

Table 1

Will this patient become violent? Questions to consider before a clinical encounter

Long-term behavior

|

Immediate situation

|

Clinicians can often avoid arousing confused patients by using orienting techniques and explaining their actions. For example, a nurse might say, “Hello Mr. X, I am a nurse and you are in this hospital for treatment of your illness. I will need to use this machine to check your blood pressure.”

Humiliation. Men in particular can react aggressively to loss of self-esteem and feelings of powerlessness. Take note if a man has been humiliated in front of family before being brought for evaluation; for example, was he removed by police in an emergency detention situation? This patient may need to act out violently to restore his sense of self.

Staff can lessen a patient’s potential to act on humiliation by using a therapeutic, esteem-building interview technique. For example, address the patient as “Mr.” instead of by first name, and highlight his strengths or accomplishments early in the interview.

Table 2

Risk factors for violence among psychiatric patients*

|

| * As identified in the literature. |

Step 4: Structure the interview for safety

The time you take before an interview to learn about a patient’s violence history, context, and arousal state is time well-spent and more patient-specific than past diagnoses. This information allows you to prepare for a safe intervention.

Interview environment. The physical and social environment where you interview the patient may contribute to violence potential.

- Is the patient being interviewed in a cramped room or an open hallway?

- Is the evaluation unit overcrowded?

- Are security personnel visible?

- Is the examiner of the same race or ethnic background as the patient?

Cramped and overcrowded conditions on a psychiatric ward have been associated with higher rates of patient violence.2 In one case of context-specific violence, a veteran with known institutional transference issues toward the government attacked providers in a VA hospital on several occasions but did not exhibit this behavior in other, non-VA medical settings.

Take control of the interview and treatment situation. Use the physical space and personnel as you would any other intervention tool—to increase safety and decrease potential for violent behavior. For example, some patients do better when interviewed in a small, private setting. Other interviews must be conducted in a triage area while police escorts hold the patient and handcuffs remain on.

Ideally, you and the patient should have equal access to the door if you conduct the psychiatric interview in an enclosed room. With high-risk patients, arrange your seating at a 90-degree angle—rather than face-to-face—to limit sustained, confrontational eye contact. Sit at greater than an arm swing or leg kick away from the patient, and require him or her to remain seated during the interview (or you will promptly leave).

In the outpatient practice, terminate the interview or evaluation session if a patient in a negative affective arousal state does not allow verbal redirection. Before you make any movement to exit, however, announce, “I am leaving the room now.”

Trust your intuition. I do not enter a closed, private space with a patient unless I feel safe. If I feel afraid, I take that as a valuable warning that further safety measures are necessary.

Use restraints as needed. When patients with a history of violence are brought to the hospital in high arousal states, I let them remain in restraint with security present during the initial interview. If the patient cannot have a back-and-forth conversation with me, I keep the security force present until I believe my verbal interactions have a substantial effect.

Patients must be responsive to talking interventions before restraint, security, or other environmental safety measures are removed. Some patients do not reach this point until after tranquilizing medications are given.

Step 5: Tthe clinical encounter

When discussing how to assess the likelihood of patient violence during a clinical encounter, a psychiatric colleague once commented, “Risk factors make you worry more; nothing makes you worry less.”

In other words, keep your guard up. Let clinical judgment take precedence over statistics when you are evaluating any patient. Statistics represent frequencies or averages; they may or may not apply to any one individual.

Techniques for assessing and treating violent patients are beyond the scope of this article, but at the very least:

- obtain training in safety/treatment protocols for violent patients

- ensure that your hospital/clinic has procedures in place to improve safety and to handle violent situations.

Visible, high numbers of confident-appearing—but not confrontational—staff or security may dissuade the patient from acting out. Then, most often, force will not be needed. If force is needed to control a violent patient, make sure the staff’s response is strong and overwhelming.

For every violent act requiring staff intervention, automatically schedule a debriefing session for those involved to assess the incident and allow them to express their feelings.

Related resources

- American Association for Emergency Psychiatry. www.emergencypsychiatry.org

- Volavka J. The neurobiology of violence: an update. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;11:307-14.

- McNiel DE, Eisner JP, Binder RL. The relationship between command hallucinations and violence. Psychiatric Services 2000;51:1288-92.

“Will this patient turn violent?” Psychiatrists face this tough question every day. Although predicting a complex behavior such as violence is nearly impossible, we can prepare for dangerous behavior and improve our safety by:

- knowing the risk factors for patient violence

- assessing individuals for violence potential before clinical encounters

- controlling situations to reduce injury risk.

In one study, more than 50% of psychiatrists and 75% of mental health nurses reported an act or threat of violence from patients within the past year.1 To help you avoid becoming a statistic, this article provides a 5-step procedure (Figure 1). to quickly assess and respond to risk of violence in a psychiatric patient.

Step 1: Seek patient history

A careful review of past events and those immediately preceding the clinical encounter is the best tool for assessing potential for violence. The more you can learn from the patient chart and other sources before you see the patient, the better (Table 1). Valuable clues can be obtained from interviews with family members, outpatient providers, police officers, and others who have had pertinent social contact with the patient.

Figure 5 steps to assess and reduce the risk of patient violence

Past violence is the most powerful predictor of future violence, according to published studies. Higher frequency of aggressive episodes, greater degree of aggressive injury, and lack of apparent provocation in past episodes all increase the violence risk.3

A minority of patients account for most aggressive acts in clinical encounters. One study showed that recidivists committed 53% of all violent behaviors in a health care setting.4 A patient’s history of violence should be flagged in the chart and verbally passed on to staff to alert providers of increased risk.

However, not having a violent history does not guarantee that a patient will not become dangerous during a clinical encounter. All patients with a violent past had an initial violent episode, and that first time can occur in a practice setting.

Psychotic states by themselves appear to increase the risk of violence, although the literature is mixed.5,6 Clearly, however, psychotic states associated with arousal or agitation do predispose patients to violence, especially if the psychosis involves active paranoid delusions or hallucinations associated with negative affect (anger, sadness, anxiety).7

Increased rates of violence have also been reported in psychiatric patients with:

- acute manic states associated with arousal or agitation8

- nonspecific neurologic abnormalities such as abnormal EEGs, localizing neurologic signs, or “soft signs” (impaired face-hand test, graphesthesia, stereognosis).9

Demographic variables associated with higher violence rates include ages 15 to 24, nonwhite race, male gender, poverty, and low educational level. Other variables include history of abuse, victimization, family violence, limited employment skills, and “rootlessness,” such as poor family network and frequent moves or job changes.10

Psychiatric diagnoses associated with increased risk of violence include schizophrenia, bipolar mania, alcohol and other substance abuse, and personality disorders.11-13 In clinical practice, however, I find psychiatric diagnoses less useful in predicting violence than the patient’s arousal state and the other risk factors discussed above.

Step 2: Evaluate the context

In addition to evidence-supported risk factors (Table 2), context—or the broader situation in which a patient is embedded at the time of psychiatric evaluation—plays a prominent role in potentially violent situations. For example, if “divorce” is listed as a presenting factor:

- Is the patient recently divorced, or did it occur years ago?

- Does he hate all women or just his ex-wife?

- Was she having an affair, and did he just learn about this?

In other words, environmental stresses can be acute and destabilizing or part of the patient’s chronic life picture and serve in homeostatic functioning.

Step 3: Identify arousal states

Patients rarely commit violent acts when their anxiety and moods are well controlled. They are more likely to become aggressive in high arousal states.

Fear is probably an element of most situations where patients act out violently. Because the fearful patient may not exhibit easily interpreted danger signals, however, you may unwittingly provoke an assault by violating his or her personal space. A fearful, paranoid patient requires a greater-than-usual “intimate zone,” although this need for increased space may not be obvious.

Minimize provocation by explaining your actions and behaviors in advance (such as, “I would like to enter the room, sit down, and talk with you for about 20 minutes”). Be business-like with paranoid patients. Avoid exuding warmth, as they may view attempts at warmth as having sinister intent.

Clinicians are sometimes injured when trying to prevent a fearful, paranoid patient from fleeing. To avoid injury, don’t stand between the patient and the door. Let the patient escape from the immediate situation, and enlist security or police in further intervention attempts.

Anger is easy to recognize by signs of mounting tension. Loud voice, inappropriate staring, banging objects, clenched fists, agitated pacing, and verbal threats are common in the angry patient before a violent episode. Although this seems self-evident, it is surprising how many violent acts occur when these signs are obvious and noted by staff, yet no de-escalation measures are taken.

A patient’s verbal threats can actually help the clinician. This “red flag” alerts staff to focus on de-escalation techniques and prepare for a violent situation.

Confusion can be an underlying risk factor in patients with delirium or nonspecific organic brain syndrome. These patients may strike out unexpectedly when health care personnel are attempting to do routine procedures, and clinicians are sometimes caught off-guard when operating in a care-giving rather than defensive mode.

Table 1

Will this patient become violent? Questions to consider before a clinical encounter

Long-term behavior

|

Immediate situation

|

Clinicians can often avoid arousing confused patients by using orienting techniques and explaining their actions. For example, a nurse might say, “Hello Mr. X, I am a nurse and you are in this hospital for treatment of your illness. I will need to use this machine to check your blood pressure.”

Humiliation. Men in particular can react aggressively to loss of self-esteem and feelings of powerlessness. Take note if a man has been humiliated in front of family before being brought for evaluation; for example, was he removed by police in an emergency detention situation? This patient may need to act out violently to restore his sense of self.

Staff can lessen a patient’s potential to act on humiliation by using a therapeutic, esteem-building interview technique. For example, address the patient as “Mr.” instead of by first name, and highlight his strengths or accomplishments early in the interview.

Table 2

Risk factors for violence among psychiatric patients*

|

| * As identified in the literature. |

Step 4: Structure the interview for safety

The time you take before an interview to learn about a patient’s violence history, context, and arousal state is time well-spent and more patient-specific than past diagnoses. This information allows you to prepare for a safe intervention.

Interview environment. The physical and social environment where you interview the patient may contribute to violence potential.

- Is the patient being interviewed in a cramped room or an open hallway?

- Is the evaluation unit overcrowded?

- Are security personnel visible?

- Is the examiner of the same race or ethnic background as the patient?

Cramped and overcrowded conditions on a psychiatric ward have been associated with higher rates of patient violence.2 In one case of context-specific violence, a veteran with known institutional transference issues toward the government attacked providers in a VA hospital on several occasions but did not exhibit this behavior in other, non-VA medical settings.

Take control of the interview and treatment situation. Use the physical space and personnel as you would any other intervention tool—to increase safety and decrease potential for violent behavior. For example, some patients do better when interviewed in a small, private setting. Other interviews must be conducted in a triage area while police escorts hold the patient and handcuffs remain on.

Ideally, you and the patient should have equal access to the door if you conduct the psychiatric interview in an enclosed room. With high-risk patients, arrange your seating at a 90-degree angle—rather than face-to-face—to limit sustained, confrontational eye contact. Sit at greater than an arm swing or leg kick away from the patient, and require him or her to remain seated during the interview (or you will promptly leave).

In the outpatient practice, terminate the interview or evaluation session if a patient in a negative affective arousal state does not allow verbal redirection. Before you make any movement to exit, however, announce, “I am leaving the room now.”

Trust your intuition. I do not enter a closed, private space with a patient unless I feel safe. If I feel afraid, I take that as a valuable warning that further safety measures are necessary.

Use restraints as needed. When patients with a history of violence are brought to the hospital in high arousal states, I let them remain in restraint with security present during the initial interview. If the patient cannot have a back-and-forth conversation with me, I keep the security force present until I believe my verbal interactions have a substantial effect.

Patients must be responsive to talking interventions before restraint, security, or other environmental safety measures are removed. Some patients do not reach this point until after tranquilizing medications are given.

Step 5: Tthe clinical encounter

When discussing how to assess the likelihood of patient violence during a clinical encounter, a psychiatric colleague once commented, “Risk factors make you worry more; nothing makes you worry less.”

In other words, keep your guard up. Let clinical judgment take precedence over statistics when you are evaluating any patient. Statistics represent frequencies or averages; they may or may not apply to any one individual.

Techniques for assessing and treating violent patients are beyond the scope of this article, but at the very least:

- obtain training in safety/treatment protocols for violent patients

- ensure that your hospital/clinic has procedures in place to improve safety and to handle violent situations.

Visible, high numbers of confident-appearing—but not confrontational—staff or security may dissuade the patient from acting out. Then, most often, force will not be needed. If force is needed to control a violent patient, make sure the staff’s response is strong and overwhelming.

For every violent act requiring staff intervention, automatically schedule a debriefing session for those involved to assess the incident and allow them to express their feelings.

Related resources

- American Association for Emergency Psychiatry. www.emergencypsychiatry.org

- Volavka J. The neurobiology of violence: an update. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;11:307-14.

- McNiel DE, Eisner JP, Binder RL. The relationship between command hallucinations and violence. Psychiatric Services 2000;51:1288-92.

1. Nolan P, Dallender J, Soares J, et al. Violence in mental health care: the experiences of mental health nurses and psychiatrists. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:934-41.

2. Blomhoff S, Seim S, Friis S. Can prediction of violence among psychiatric inpatients be improved? Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:771-5.

3. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al. Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1112-5.

4. Taylor P. Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:491-8.

5. Junginger J, Parks-Levy J, McGuire L. Delusions and symptom-consistent violence. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:218-20.

6. Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley K, et al. Violence in schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Res 1997;26:181-90.

7. Binder R, McNiel D. Effects of diagnosis and context on dangerousness. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:728-32.

8. Convit A, Jaeger J, Pin Lin S, et al. Predicting assaultiveness in psychiatric inpatients: A pilot study. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1988;39:429-34.

9. Hyman S. The violent patient. In: Hyman S (ed). Manual of psychiatric emergencies. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1988;23-31.

10. Swartz M, Swanson J, Hiday V, et al. Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:226-31.

11. Owen C, Tarantello C, Jones M, et al. Repetitively violent patients in psychiatric units. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:1458-61.

12. Citrome L, Volavka J. Clinical management of persistent aggressive behavior in schizophrenia, part I. Definitions, epidemiology, assessment and acute treatment. Essen Psychopharmacol 2002;5:1-16.

13. Abeyasinghe R, Jayasekera R. Violence in a general hospital psychiatry unit for men. Ceylon Med J 2003;48(2):45-7.

1. Nolan P, Dallender J, Soares J, et al. Violence in mental health care: the experiences of mental health nurses and psychiatrists. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:934-41.

2. Blomhoff S, Seim S, Friis S. Can prediction of violence among psychiatric inpatients be improved? Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:771-5.

3. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al. Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1112-5.

4. Taylor P. Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:491-8.

5. Junginger J, Parks-Levy J, McGuire L. Delusions and symptom-consistent violence. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:218-20.

6. Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley K, et al. Violence in schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Res 1997;26:181-90.

7. Binder R, McNiel D. Effects of diagnosis and context on dangerousness. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:728-32.

8. Convit A, Jaeger J, Pin Lin S, et al. Predicting assaultiveness in psychiatric inpatients: A pilot study. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1988;39:429-34.

9. Hyman S. The violent patient. In: Hyman S (ed). Manual of psychiatric emergencies. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1988;23-31.

10. Swartz M, Swanson J, Hiday V, et al. Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:226-31.

11. Owen C, Tarantello C, Jones M, et al. Repetitively violent patients in psychiatric units. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:1458-61.

12. Citrome L, Volavka J. Clinical management of persistent aggressive behavior in schizophrenia, part I. Definitions, epidemiology, assessment and acute treatment. Essen Psychopharmacol 2002;5:1-16.

13. Abeyasinghe R, Jayasekera R. Violence in a general hospital psychiatry unit for men. Ceylon Med J 2003;48(2):45-7.