User login

Recruiting ObGyns: Starting salary considerations

Evidence continues to show that the number of practicing ObGyns lags the growing and diverse US population of women.1 Furthermore, approximately 1 in every 3 ObGyns will move usually once or twice every 10 years.2 Knowing what to expect in being recruited requires a better understanding of your needs and capabilities and what they may be worth in real time. Some ObGyns elect to use a recruitment firm to begin their search to more objectively assess what is fair and equitable.

Understanding physician compensation involves many factors, such as patient composition, sources of reimbursement, impact of health care systems, and geography.3 Several sources report trends in annual physician compensation, most notably the American Medical Association, medical specialty organizations, and recruitment firms. Sources such as the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), the American Medical Group Association (AMGA), and Medscape report total compensation.

Determining salaries for new positions

A standard and comprehensive benchmarking resource for salaries in new positions has been the annual review of physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives by AMN Healthcare (formerly Merritt Hawkins) Physician Solutions.4 This resource is used by hospitals, medical groups, academics, other health care systems, and others who track trends in physician supply, demand, and compensation. Their 2023 report considered starting salaries for more than 20 medical or surgical specialties.

Specialists’ revenue-generating potential is tracked by annual billings to commercial payers. The average annual billing by a full-time ObGyn ($3.8 million) is about the same as that of other specialties combined.5 As in the past, ObGyns are among the most consistently requested specialists in searches. In 2023, ObGyns were ranked the third most common physician specialists being recruited and tenth as the percentage of physicians per specialty (TABLE).4

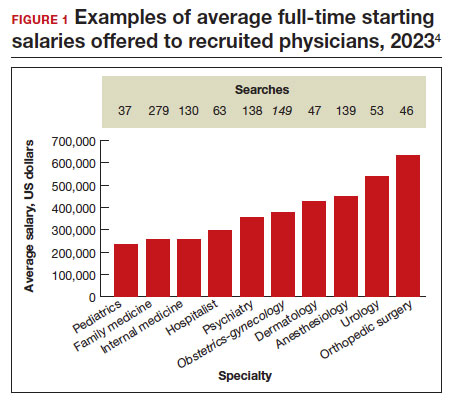

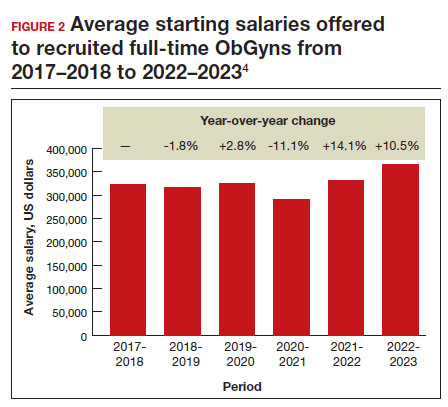

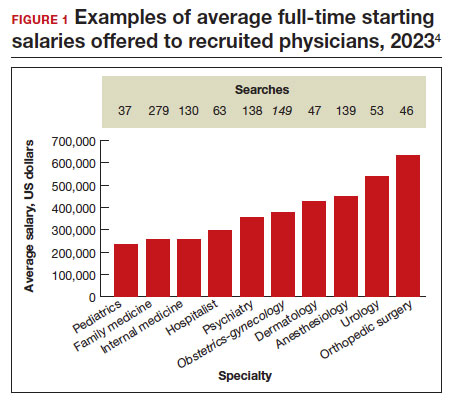

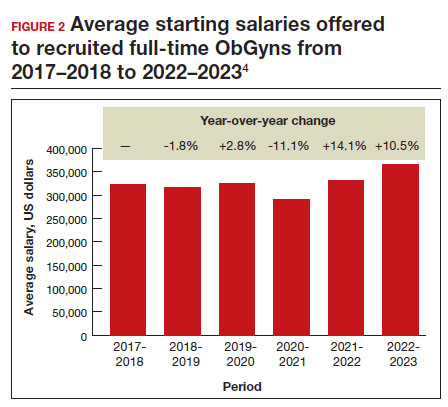

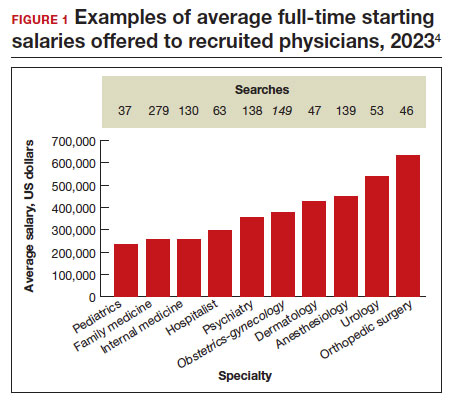

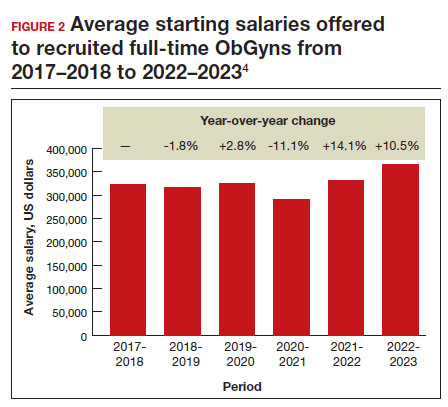

Full-time salaries for ObGyns have remained within the middle third of all specialties. They consistently have been higher than primary care physicians’ salaries but remain among the lowest of the surgical specialties. This impression is reinforced by 2023 data shown in FIGURE 1.4 In the past, salaries remained flat compared with other surgical specialties. As with other specialties, starting salaries decreased during the peak 2020 and 2021 COVID-19 years. It is encouraging that averaged full-time salaries for recruiting ObGyns increased by 14.1% from 2020–2021 to 2021–2022 and by 10.5% from 2021–2022 to 2022–2023 (FIGURE 2).4

Special considerations

Incomes tended to be highest for ObGyns practicing in metropolitan areas with population sizes less than 1 million rather than in larger metropolitan areas.3 However, differences in reported incomes do not control for cost of living and other determinants of income (for example, surgeries, deliveries, patient care hours worked). Averaged salaries can vary regionally in the following order from highest to lowest: Midwest/Great Plains, West, Southwest, and Northeast and Southeast.4

Differences in starting salaries between male and female ObGyns are often not reported, although they are a very important consideration.6,7 Both men and women desire “controllable lifestyles” with more flexibility and working in shifts. Sex-based differences in physician salary and compensation can be complex. Explanations may deal with the number of patients seen, number of procedures and surgeries performed, and frequency of after-hours duties. Women constitute most ObGyns, and their salary being at any lower end of the income spectrum may be partially explained by fewer desired work hours or less seniority.

Annual earnings can vary and are positively related to the number of working hours, being in the middle of one’s career (aged 42–51 years), working in a moderately large practice rather than in a solo or self-employed practice, and being board certified.3 A lower starting salary would be anticipated for a recent graduate. However, the resident going into a hard-to-fill position may be offered a higher salary than an experienced ObGyn who takes a relatively easy-to-fill position in a popular location. Practices would be more desirable in which patient volume is sufficient to invest in nonphysician clinicians and revenue-generating ancillary services that do not require costly layers of administration.

Information on physician salaries for new positions from individual recruiting or research firms can serve as a starting point for negotiation, although it may not entirely be representative. Sample sizes can be small, and information in some specialties may not separate salaries of physicians in academic versus nonacademic positions and generalists versus subspecialists. The information in this article reflects the average salaries offered to attract physicians to new practice settings rather than what they might earn and report on their tax return.

Continue to: Incentives...

Incentives

Negotiations involve incentives along with a starting salary. Signing bonuses, movingallowances, continuing education time and allowances, and medical education loan repayments are important incentives. Recent signing bonuses (average, $37,472) likely reflect efforts to bring physicians back to health care facilities post-COVID-19 or, more commonly, when candidates are considering multiple opportunities.4 It is important to clarify at the beginning any coverage for health insurance and professional liability insurance.

Relocation allowances are for those being recruited outside their current area of residence. The average continuing medical education allowance was $3,840 in 2023.4 Medical school debt is common, being approximately $200,000 at graduation for many. An educational loan repayment (average, $98,665) is typically an exchange for a commitment to stay in the community for a given period.

Starting employment contracts with hospitals or large medical groups often feature a production bonus to reward additional clinical work performed or an adherence to quality protocol or guidelines, rather than income guarantees alone. Metrics are usually volume driven (for example, relative value units, net collections, gross billings, patients seen). Initiatives by payers and health care organizations have included quality metrics, such as high patient satisfaction scores, low morbidity rates, and low readmission rates. Production-based formulas are straightforward, while use of quality-based formulas (up to 14% of total compensation) can be less clear to define.4 ●

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM. Expanded fellowship training and residency graduates’ availability for women’s general health needs. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:1119-1121.

- Xierali IM, Nivett MA, Rayburn WF. Relocation of obstetriciangynecologists in the United States, 2005-2015. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:543-550.

- Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician-Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications. 2nd ed. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- AMN Healthcare. 2023 Review of physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives. July 24, 2023. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.amnhealthcare.com/amn -insights/physician/surveys/2023-physician-and-ap -recruiting-incentives/

- AMN Healthcare. 2023 Physician billing report. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.amnhealthcare. com/amn-insights/physician/whitepapers/2023-physician -billing-report/

- Bravender T, Selkie E, Sturza J, et al. Association of salary differences between medical specialties with sex distribution. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:524-525.

- Lo Sasso AT, Armstrong D, Forte G, et al. Differences in starting pay for male and female physicians persist; explanations for the gender gap remain elusive. Health Aff. 2020;39:256-263.

Evidence continues to show that the number of practicing ObGyns lags the growing and diverse US population of women.1 Furthermore, approximately 1 in every 3 ObGyns will move usually once or twice every 10 years.2 Knowing what to expect in being recruited requires a better understanding of your needs and capabilities and what they may be worth in real time. Some ObGyns elect to use a recruitment firm to begin their search to more objectively assess what is fair and equitable.

Understanding physician compensation involves many factors, such as patient composition, sources of reimbursement, impact of health care systems, and geography.3 Several sources report trends in annual physician compensation, most notably the American Medical Association, medical specialty organizations, and recruitment firms. Sources such as the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), the American Medical Group Association (AMGA), and Medscape report total compensation.

Determining salaries for new positions

A standard and comprehensive benchmarking resource for salaries in new positions has been the annual review of physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives by AMN Healthcare (formerly Merritt Hawkins) Physician Solutions.4 This resource is used by hospitals, medical groups, academics, other health care systems, and others who track trends in physician supply, demand, and compensation. Their 2023 report considered starting salaries for more than 20 medical or surgical specialties.

Specialists’ revenue-generating potential is tracked by annual billings to commercial payers. The average annual billing by a full-time ObGyn ($3.8 million) is about the same as that of other specialties combined.5 As in the past, ObGyns are among the most consistently requested specialists in searches. In 2023, ObGyns were ranked the third most common physician specialists being recruited and tenth as the percentage of physicians per specialty (TABLE).4

Full-time salaries for ObGyns have remained within the middle third of all specialties. They consistently have been higher than primary care physicians’ salaries but remain among the lowest of the surgical specialties. This impression is reinforced by 2023 data shown in FIGURE 1.4 In the past, salaries remained flat compared with other surgical specialties. As with other specialties, starting salaries decreased during the peak 2020 and 2021 COVID-19 years. It is encouraging that averaged full-time salaries for recruiting ObGyns increased by 14.1% from 2020–2021 to 2021–2022 and by 10.5% from 2021–2022 to 2022–2023 (FIGURE 2).4

Special considerations

Incomes tended to be highest for ObGyns practicing in metropolitan areas with population sizes less than 1 million rather than in larger metropolitan areas.3 However, differences in reported incomes do not control for cost of living and other determinants of income (for example, surgeries, deliveries, patient care hours worked). Averaged salaries can vary regionally in the following order from highest to lowest: Midwest/Great Plains, West, Southwest, and Northeast and Southeast.4

Differences in starting salaries between male and female ObGyns are often not reported, although they are a very important consideration.6,7 Both men and women desire “controllable lifestyles” with more flexibility and working in shifts. Sex-based differences in physician salary and compensation can be complex. Explanations may deal with the number of patients seen, number of procedures and surgeries performed, and frequency of after-hours duties. Women constitute most ObGyns, and their salary being at any lower end of the income spectrum may be partially explained by fewer desired work hours or less seniority.

Annual earnings can vary and are positively related to the number of working hours, being in the middle of one’s career (aged 42–51 years), working in a moderately large practice rather than in a solo or self-employed practice, and being board certified.3 A lower starting salary would be anticipated for a recent graduate. However, the resident going into a hard-to-fill position may be offered a higher salary than an experienced ObGyn who takes a relatively easy-to-fill position in a popular location. Practices would be more desirable in which patient volume is sufficient to invest in nonphysician clinicians and revenue-generating ancillary services that do not require costly layers of administration.

Information on physician salaries for new positions from individual recruiting or research firms can serve as a starting point for negotiation, although it may not entirely be representative. Sample sizes can be small, and information in some specialties may not separate salaries of physicians in academic versus nonacademic positions and generalists versus subspecialists. The information in this article reflects the average salaries offered to attract physicians to new practice settings rather than what they might earn and report on their tax return.

Continue to: Incentives...

Incentives

Negotiations involve incentives along with a starting salary. Signing bonuses, movingallowances, continuing education time and allowances, and medical education loan repayments are important incentives. Recent signing bonuses (average, $37,472) likely reflect efforts to bring physicians back to health care facilities post-COVID-19 or, more commonly, when candidates are considering multiple opportunities.4 It is important to clarify at the beginning any coverage for health insurance and professional liability insurance.

Relocation allowances are for those being recruited outside their current area of residence. The average continuing medical education allowance was $3,840 in 2023.4 Medical school debt is common, being approximately $200,000 at graduation for many. An educational loan repayment (average, $98,665) is typically an exchange for a commitment to stay in the community for a given period.

Starting employment contracts with hospitals or large medical groups often feature a production bonus to reward additional clinical work performed or an adherence to quality protocol or guidelines, rather than income guarantees alone. Metrics are usually volume driven (for example, relative value units, net collections, gross billings, patients seen). Initiatives by payers and health care organizations have included quality metrics, such as high patient satisfaction scores, low morbidity rates, and low readmission rates. Production-based formulas are straightforward, while use of quality-based formulas (up to 14% of total compensation) can be less clear to define.4 ●

Evidence continues to show that the number of practicing ObGyns lags the growing and diverse US population of women.1 Furthermore, approximately 1 in every 3 ObGyns will move usually once or twice every 10 years.2 Knowing what to expect in being recruited requires a better understanding of your needs and capabilities and what they may be worth in real time. Some ObGyns elect to use a recruitment firm to begin their search to more objectively assess what is fair and equitable.

Understanding physician compensation involves many factors, such as patient composition, sources of reimbursement, impact of health care systems, and geography.3 Several sources report trends in annual physician compensation, most notably the American Medical Association, medical specialty organizations, and recruitment firms. Sources such as the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), the American Medical Group Association (AMGA), and Medscape report total compensation.

Determining salaries for new positions

A standard and comprehensive benchmarking resource for salaries in new positions has been the annual review of physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives by AMN Healthcare (formerly Merritt Hawkins) Physician Solutions.4 This resource is used by hospitals, medical groups, academics, other health care systems, and others who track trends in physician supply, demand, and compensation. Their 2023 report considered starting salaries for more than 20 medical or surgical specialties.

Specialists’ revenue-generating potential is tracked by annual billings to commercial payers. The average annual billing by a full-time ObGyn ($3.8 million) is about the same as that of other specialties combined.5 As in the past, ObGyns are among the most consistently requested specialists in searches. In 2023, ObGyns were ranked the third most common physician specialists being recruited and tenth as the percentage of physicians per specialty (TABLE).4

Full-time salaries for ObGyns have remained within the middle third of all specialties. They consistently have been higher than primary care physicians’ salaries but remain among the lowest of the surgical specialties. This impression is reinforced by 2023 data shown in FIGURE 1.4 In the past, salaries remained flat compared with other surgical specialties. As with other specialties, starting salaries decreased during the peak 2020 and 2021 COVID-19 years. It is encouraging that averaged full-time salaries for recruiting ObGyns increased by 14.1% from 2020–2021 to 2021–2022 and by 10.5% from 2021–2022 to 2022–2023 (FIGURE 2).4

Special considerations

Incomes tended to be highest for ObGyns practicing in metropolitan areas with population sizes less than 1 million rather than in larger metropolitan areas.3 However, differences in reported incomes do not control for cost of living and other determinants of income (for example, surgeries, deliveries, patient care hours worked). Averaged salaries can vary regionally in the following order from highest to lowest: Midwest/Great Plains, West, Southwest, and Northeast and Southeast.4

Differences in starting salaries between male and female ObGyns are often not reported, although they are a very important consideration.6,7 Both men and women desire “controllable lifestyles” with more flexibility and working in shifts. Sex-based differences in physician salary and compensation can be complex. Explanations may deal with the number of patients seen, number of procedures and surgeries performed, and frequency of after-hours duties. Women constitute most ObGyns, and their salary being at any lower end of the income spectrum may be partially explained by fewer desired work hours or less seniority.

Annual earnings can vary and are positively related to the number of working hours, being in the middle of one’s career (aged 42–51 years), working in a moderately large practice rather than in a solo or self-employed practice, and being board certified.3 A lower starting salary would be anticipated for a recent graduate. However, the resident going into a hard-to-fill position may be offered a higher salary than an experienced ObGyn who takes a relatively easy-to-fill position in a popular location. Practices would be more desirable in which patient volume is sufficient to invest in nonphysician clinicians and revenue-generating ancillary services that do not require costly layers of administration.

Information on physician salaries for new positions from individual recruiting or research firms can serve as a starting point for negotiation, although it may not entirely be representative. Sample sizes can be small, and information in some specialties may not separate salaries of physicians in academic versus nonacademic positions and generalists versus subspecialists. The information in this article reflects the average salaries offered to attract physicians to new practice settings rather than what they might earn and report on their tax return.

Continue to: Incentives...

Incentives

Negotiations involve incentives along with a starting salary. Signing bonuses, movingallowances, continuing education time and allowances, and medical education loan repayments are important incentives. Recent signing bonuses (average, $37,472) likely reflect efforts to bring physicians back to health care facilities post-COVID-19 or, more commonly, when candidates are considering multiple opportunities.4 It is important to clarify at the beginning any coverage for health insurance and professional liability insurance.

Relocation allowances are for those being recruited outside their current area of residence. The average continuing medical education allowance was $3,840 in 2023.4 Medical school debt is common, being approximately $200,000 at graduation for many. An educational loan repayment (average, $98,665) is typically an exchange for a commitment to stay in the community for a given period.

Starting employment contracts with hospitals or large medical groups often feature a production bonus to reward additional clinical work performed or an adherence to quality protocol or guidelines, rather than income guarantees alone. Metrics are usually volume driven (for example, relative value units, net collections, gross billings, patients seen). Initiatives by payers and health care organizations have included quality metrics, such as high patient satisfaction scores, low morbidity rates, and low readmission rates. Production-based formulas are straightforward, while use of quality-based formulas (up to 14% of total compensation) can be less clear to define.4 ●

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM. Expanded fellowship training and residency graduates’ availability for women’s general health needs. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:1119-1121.

- Xierali IM, Nivett MA, Rayburn WF. Relocation of obstetriciangynecologists in the United States, 2005-2015. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:543-550.

- Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician-Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications. 2nd ed. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- AMN Healthcare. 2023 Review of physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives. July 24, 2023. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.amnhealthcare.com/amn -insights/physician/surveys/2023-physician-and-ap -recruiting-incentives/

- AMN Healthcare. 2023 Physician billing report. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.amnhealthcare. com/amn-insights/physician/whitepapers/2023-physician -billing-report/

- Bravender T, Selkie E, Sturza J, et al. Association of salary differences between medical specialties with sex distribution. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:524-525.

- Lo Sasso AT, Armstrong D, Forte G, et al. Differences in starting pay for male and female physicians persist; explanations for the gender gap remain elusive. Health Aff. 2020;39:256-263.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM. Expanded fellowship training and residency graduates’ availability for women’s general health needs. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:1119-1121.

- Xierali IM, Nivett MA, Rayburn WF. Relocation of obstetriciangynecologists in the United States, 2005-2015. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:543-550.

- Rayburn WF. The Obstetrician-Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts, Figures, and Implications. 2nd ed. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017.

- AMN Healthcare. 2023 Review of physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives. July 24, 2023. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.amnhealthcare.com/amn -insights/physician/surveys/2023-physician-and-ap -recruiting-incentives/

- AMN Healthcare. 2023 Physician billing report. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.amnhealthcare. com/amn-insights/physician/whitepapers/2023-physician -billing-report/

- Bravender T, Selkie E, Sturza J, et al. Association of salary differences between medical specialties with sex distribution. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:524-525.

- Lo Sasso AT, Armstrong D, Forte G, et al. Differences in starting pay for male and female physicians persist; explanations for the gender gap remain elusive. Health Aff. 2020;39:256-263.

ObGyn: A leader in academic medicine, with progress still to be made in diversity

The nation’s population is quickly diversifying, making racial/ethnic disparities in health care outcomes even more apparent. Minority and non-English-speaking populations have grown and may become a majority in the next generation.1 A proposed strategy to reduce disparities in health care is to recruit more practitioners who better reflect the patient populations.2 Improved access to care with racial concordance between physicians and patients has been reported.3

Being increasingly aware of access-to-care data, more patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their providers.4 Despite progress (ie, more women entering the medical profession), the proportion of physicians who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM—eg, Black, Hispanic, and Native American) still lags US population demographics.3

Why diversity in medicine matters

In addition to improving access to care, diversity in medicine offers other benefits. Working within diverse learning environments has demonstrated educational advantages.5,6 Medical students and residents from diverse backgrounds are less likely to report depression symptoms, regardless of their race. Diversity may accelerate advancements in health care as well, since it is well-established that diverse teams outperform nondiverse teams when it comes to innovation and productivity.7 Finally, as a profession committed to equity, advocacy, and justice, physicians are positioned to lead the way toward racial equity.

Overall, racial and gender diversity in all clinical specialties is improving, but not at the same pace. While the diversity of US medical students and residents by sex and race/ethnicity is greater than among faculty, change in racial diversity has been slow for all 3 groups.8 During the past 40 years the number of full-time faculty has increased 6-fold for females and more than tripled for males.8 However, this rise has not favored URiM faculty, because their proportion is still underrepresented relative to their group in the general population. Clinical departments that are making the most progress in recruiting URiM residents and faculty are often primary or preventive care specialties rather than surgical or service or hospital-based specialties.8,9 ObGyn has consistently had a proportion of URiM residents (18%) that is highest in the surgical specialties and comparable to family medicine and pediatrics.10

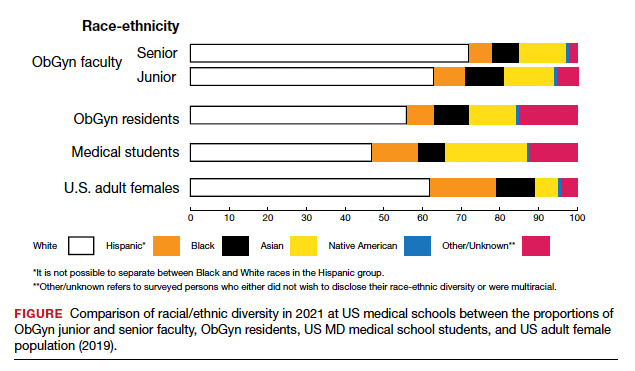

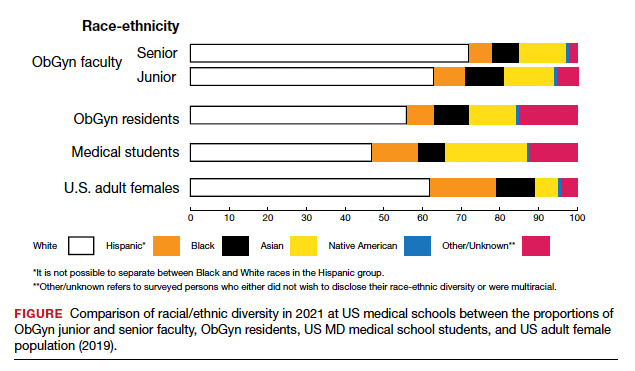

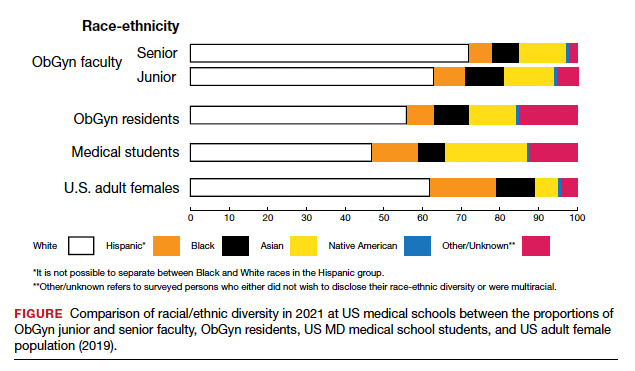

When examining physician workforce diversity, it is important to “drill down” to individual specialties to obtain a clearer understanding of trends. The continued need for increased resident and faculty diversity prompted us to examine ObGyn departments. The most recent nationwide data were gathered about full-time faculty from the 2021 AAMC Faculty Roster, residents from the 2021 Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Data Resource Book, medical student matriculants from 2021 AAMC, and US adult women (defined arbitrarily as 15 years or older) from the 2019 American Community Survey.11-13

Increase in female faculty and residents

The expanding numbers of faculty and residents over a 40-year period (from 1973 to 2012) led to more women and underrepresented minorities in ObGyn than in other major clinical departments.14,15 Women now constitute two-thirds of all ObGyn faculty and are more likely to be junior rather than senior faculty.9 When looking at junior faculty, a higher proportion of junior faculty who are URiM are female. While more junior faculty and residents are female, male faculty are also racially and ethnically diverse.9

- ObGyn is a leader in racial/ethnic diversity in academic medicine.

- The rapid rise of faculty numbers in the past has not favored underrepresented faculty.

- The rise in ObGyn faculty and residents, who were predominantly female, has contributed to greater racial/ethnic diversity.

- Improved patient outcomes with racial concordance between physicians and patients have been reported.

- More patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their clinicians.

- Racial/ethnic diversity of junior faculty and residents is similar to medical students.

- The most underrepresented group is Hispanic, due in part to its rapid growth in the US population.

Continue to: Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn...

Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn

The distribution of racial/ethnic groups in 2021 were compared between senior and junior ObGyn faculty and residents with the US adult female population.9 As shown in the FIGURE, the proportion of ObGyn faculty who are White approximates the White US adult female population. The most rapidly growing racial/ethnic group in the US population is Hispanic. Although Hispanic is the best represented ethnicity among junior faculty, the proportions of Hispanics among faculty and residents lag well behind the US population. The proportion of ObGyn faculty who are Black has consistently been less than in the US adult female population. ObGyns who are Asian constitute higher proportions of faculty and residents than in the US adult female population. This finding about Asians is consistent across all clinical specialties.7

Recruiting URiM students into ObGyn is important. Racial and ethnic representation in surgical and nonsurgical residency programs has not substantially improved in the past decade and continues to lag the changing demographics of the US population.10 More students than residents and faculty are Hispanic, which represents a much-needed opportunity for recruitment. By contrast, junior ObGyn faculty are more likely to be Black than residents and students. Native Americans constitute less than 1% of all faculty, residents, students, and US adult females.9 Lastly, race/ethnicity being self-reported as “other” or “unknown” is most common among students and residents, which perhaps represents greater diversity.

Looking back

Increasing diversity in medicine and in ObGyn has not happened by accident. Transformational change requires rectifying any factors that detrimentally affect the racial/ethnic diversity of our medical students, residents, and faculty. For example, biases inherent in key residency application metrics are being recognized, and use of holistic review is increasing. Change is also accelerated by an explicit and public commitment from national organizations. In 2009, the Liaison Committee of Medical Education (LCME) mandated that medical schools engage in practices that focus on recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce. Increases in Black and Hispanic medical students were noted after implementation of this new mandate.16 The ACGME followed suit with similar guidelines in 2019.10

Diversity is one of the foundational strengths of the ObGyn specialty. Important aspects of the specialty are built upon the contributions of women of color, some voluntary and some not. One example is the knowledge of gynecology that was gained through the involuntary and nonanesthetized surgeries performed on

Moving forward

Advancing diversity in ObGyn offers advantages: better representation of patient populations, improving public health by better access to care, enhancing learning in medical education, building more comprehensive research agendas, and driving institutional excellence. While progress has been made, significant work is still to be done. We must continue to critically examine the role of biases and structural racism that are embedded in evaluating medical students, screening of residency applicants, and selecting and retaining faculty. In future work, we should explore the hypothesis that continued change in racial/ethnic diversity of faculty will only occur once more URiM students, especially the growing number of Hispanics, are admitted into medical schools and recruited for residency positions. We should also examine whether further diversity improves patient outcomes.

It is encouraging to realize that ObGyn departments are leaders in racial/ethnic diversity at US medical schools. It is also critical that the specialty commits to the progress that still needs to be made, including increasing diversity among faculty and institutional leadership. To maintain diversity that mirrors the US adult female population, the specialty of ObGyn will require active surveillance and continued recruitment of Black and, especially Hispanic, faculty and residents.19 The national strategies aimed at building medical student and residency diversity are beginning to yield results. For those gains to help faculty diversity, institutional and departmental leaders will need to implement best practices for recruiting, retaining, and advancing URiM faculty.19 Those practices would include making workforce diversity an explicit priority, building diverse applicant pools, and establishing infrastructure and mentorship to advance URiM faculty to senior leadership positions.20

In conclusion

Building a physician workforce that is more representative of the US population should aid in addressing inequalities in health and health care. Significant strides have been made in racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn. This has resulted in a specialty that is among the most diverse in academic medicine. At the same time, there is more work to be done. For example, the specialty is far from reaching racial equity for Hispanic physicians. Also, continued efforts are necessary to advance URiM faculty to leadership positions. The legacy of racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn did not happen by accident and will not be maintained without intention. ●

- Hummes KR, Jones NA, Ramierez RR. United States Census: overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. http//www. census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2022.

- Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Zhang K, et al. AM last page: the urgency of physician workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2014;89:1192.

- Association of American Medical College. Diversity in the physician workforce. Facts & figures 2014. http://www .aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org. Accessed April 9, 2022.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: Diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJ, et al. Community-based education: The influence of role modeling on career choice and practice location. Med Teac. 2017;39:174-180.

- Umbach PD. The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res High Educ. 2006;47:317-345.

- Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Glod SA, et al. General internists as change agents: opportunities and barriers to leadership in health systems and medical education transformation. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1865-1869.

- Xierali IM, Fair MA, Nivet MA. Faculty diversity in U.S. medical schools: Progress and gaps coexist. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2016;16. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/decem ber2016facultydiversityinu.s.medicalschoolsprogressandga ps.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, McDade WA. Racial-ethnic diversity of obstetrics and gynecology faculty at medical schools in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;S00029378(22)00106-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.007.

- Hucko L, Al-khersan H, Lopez Dominguez J, et al. Racial and ethnic diversity of U.S. residency programs, 2011-2019. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:22-23.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets /publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook _document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021

- United States Census Bureau. The 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) Files.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme .org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021 _acgme_databook_document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021.

- Rayburn WF, Liu CQ, Elwell EC, et al. Diversity of physician faculty in obstetrics and gynecology. J Reprod Med. 2016;61:22-26.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Full-time faculty in clinical and basic science departments by sex and underrepresented in medicine status: A 40-year review. Acad Med. 2021;96: 568-575.

- Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer LJ, et al. Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s Diversity Standards and Changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320:2267-2269.

- United States National Library of Medicine. Changing the face of medicine.

- https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_82. html. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- Christmas M. #SayHerName: Should obstetrics and gynecology reckon with the legacy of JM Sims? Reprod Sci. 2021;28:3282-3284.

- Morgan HK, Winkel AF, Bands E, et al. Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in the selection of obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:272-277.

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, et al. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88:405-412.

The nation’s population is quickly diversifying, making racial/ethnic disparities in health care outcomes even more apparent. Minority and non-English-speaking populations have grown and may become a majority in the next generation.1 A proposed strategy to reduce disparities in health care is to recruit more practitioners who better reflect the patient populations.2 Improved access to care with racial concordance between physicians and patients has been reported.3

Being increasingly aware of access-to-care data, more patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their providers.4 Despite progress (ie, more women entering the medical profession), the proportion of physicians who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM—eg, Black, Hispanic, and Native American) still lags US population demographics.3

Why diversity in medicine matters

In addition to improving access to care, diversity in medicine offers other benefits. Working within diverse learning environments has demonstrated educational advantages.5,6 Medical students and residents from diverse backgrounds are less likely to report depression symptoms, regardless of their race. Diversity may accelerate advancements in health care as well, since it is well-established that diverse teams outperform nondiverse teams when it comes to innovation and productivity.7 Finally, as a profession committed to equity, advocacy, and justice, physicians are positioned to lead the way toward racial equity.

Overall, racial and gender diversity in all clinical specialties is improving, but not at the same pace. While the diversity of US medical students and residents by sex and race/ethnicity is greater than among faculty, change in racial diversity has been slow for all 3 groups.8 During the past 40 years the number of full-time faculty has increased 6-fold for females and more than tripled for males.8 However, this rise has not favored URiM faculty, because their proportion is still underrepresented relative to their group in the general population. Clinical departments that are making the most progress in recruiting URiM residents and faculty are often primary or preventive care specialties rather than surgical or service or hospital-based specialties.8,9 ObGyn has consistently had a proportion of URiM residents (18%) that is highest in the surgical specialties and comparable to family medicine and pediatrics.10

When examining physician workforce diversity, it is important to “drill down” to individual specialties to obtain a clearer understanding of trends. The continued need for increased resident and faculty diversity prompted us to examine ObGyn departments. The most recent nationwide data were gathered about full-time faculty from the 2021 AAMC Faculty Roster, residents from the 2021 Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Data Resource Book, medical student matriculants from 2021 AAMC, and US adult women (defined arbitrarily as 15 years or older) from the 2019 American Community Survey.11-13

Increase in female faculty and residents

The expanding numbers of faculty and residents over a 40-year period (from 1973 to 2012) led to more women and underrepresented minorities in ObGyn than in other major clinical departments.14,15 Women now constitute two-thirds of all ObGyn faculty and are more likely to be junior rather than senior faculty.9 When looking at junior faculty, a higher proportion of junior faculty who are URiM are female. While more junior faculty and residents are female, male faculty are also racially and ethnically diverse.9

- ObGyn is a leader in racial/ethnic diversity in academic medicine.

- The rapid rise of faculty numbers in the past has not favored underrepresented faculty.

- The rise in ObGyn faculty and residents, who were predominantly female, has contributed to greater racial/ethnic diversity.

- Improved patient outcomes with racial concordance between physicians and patients have been reported.

- More patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their clinicians.

- Racial/ethnic diversity of junior faculty and residents is similar to medical students.

- The most underrepresented group is Hispanic, due in part to its rapid growth in the US population.

Continue to: Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn...

Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn

The distribution of racial/ethnic groups in 2021 were compared between senior and junior ObGyn faculty and residents with the US adult female population.9 As shown in the FIGURE, the proportion of ObGyn faculty who are White approximates the White US adult female population. The most rapidly growing racial/ethnic group in the US population is Hispanic. Although Hispanic is the best represented ethnicity among junior faculty, the proportions of Hispanics among faculty and residents lag well behind the US population. The proportion of ObGyn faculty who are Black has consistently been less than in the US adult female population. ObGyns who are Asian constitute higher proportions of faculty and residents than in the US adult female population. This finding about Asians is consistent across all clinical specialties.7

Recruiting URiM students into ObGyn is important. Racial and ethnic representation in surgical and nonsurgical residency programs has not substantially improved in the past decade and continues to lag the changing demographics of the US population.10 More students than residents and faculty are Hispanic, which represents a much-needed opportunity for recruitment. By contrast, junior ObGyn faculty are more likely to be Black than residents and students. Native Americans constitute less than 1% of all faculty, residents, students, and US adult females.9 Lastly, race/ethnicity being self-reported as “other” or “unknown” is most common among students and residents, which perhaps represents greater diversity.

Looking back

Increasing diversity in medicine and in ObGyn has not happened by accident. Transformational change requires rectifying any factors that detrimentally affect the racial/ethnic diversity of our medical students, residents, and faculty. For example, biases inherent in key residency application metrics are being recognized, and use of holistic review is increasing. Change is also accelerated by an explicit and public commitment from national organizations. In 2009, the Liaison Committee of Medical Education (LCME) mandated that medical schools engage in practices that focus on recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce. Increases in Black and Hispanic medical students were noted after implementation of this new mandate.16 The ACGME followed suit with similar guidelines in 2019.10

Diversity is one of the foundational strengths of the ObGyn specialty. Important aspects of the specialty are built upon the contributions of women of color, some voluntary and some not. One example is the knowledge of gynecology that was gained through the involuntary and nonanesthetized surgeries performed on

Moving forward

Advancing diversity in ObGyn offers advantages: better representation of patient populations, improving public health by better access to care, enhancing learning in medical education, building more comprehensive research agendas, and driving institutional excellence. While progress has been made, significant work is still to be done. We must continue to critically examine the role of biases and structural racism that are embedded in evaluating medical students, screening of residency applicants, and selecting and retaining faculty. In future work, we should explore the hypothesis that continued change in racial/ethnic diversity of faculty will only occur once more URiM students, especially the growing number of Hispanics, are admitted into medical schools and recruited for residency positions. We should also examine whether further diversity improves patient outcomes.

It is encouraging to realize that ObGyn departments are leaders in racial/ethnic diversity at US medical schools. It is also critical that the specialty commits to the progress that still needs to be made, including increasing diversity among faculty and institutional leadership. To maintain diversity that mirrors the US adult female population, the specialty of ObGyn will require active surveillance and continued recruitment of Black and, especially Hispanic, faculty and residents.19 The national strategies aimed at building medical student and residency diversity are beginning to yield results. For those gains to help faculty diversity, institutional and departmental leaders will need to implement best practices for recruiting, retaining, and advancing URiM faculty.19 Those practices would include making workforce diversity an explicit priority, building diverse applicant pools, and establishing infrastructure and mentorship to advance URiM faculty to senior leadership positions.20

In conclusion

Building a physician workforce that is more representative of the US population should aid in addressing inequalities in health and health care. Significant strides have been made in racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn. This has resulted in a specialty that is among the most diverse in academic medicine. At the same time, there is more work to be done. For example, the specialty is far from reaching racial equity for Hispanic physicians. Also, continued efforts are necessary to advance URiM faculty to leadership positions. The legacy of racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn did not happen by accident and will not be maintained without intention. ●

The nation’s population is quickly diversifying, making racial/ethnic disparities in health care outcomes even more apparent. Minority and non-English-speaking populations have grown and may become a majority in the next generation.1 A proposed strategy to reduce disparities in health care is to recruit more practitioners who better reflect the patient populations.2 Improved access to care with racial concordance between physicians and patients has been reported.3

Being increasingly aware of access-to-care data, more patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their providers.4 Despite progress (ie, more women entering the medical profession), the proportion of physicians who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM—eg, Black, Hispanic, and Native American) still lags US population demographics.3

Why diversity in medicine matters

In addition to improving access to care, diversity in medicine offers other benefits. Working within diverse learning environments has demonstrated educational advantages.5,6 Medical students and residents from diverse backgrounds are less likely to report depression symptoms, regardless of their race. Diversity may accelerate advancements in health care as well, since it is well-established that diverse teams outperform nondiverse teams when it comes to innovation and productivity.7 Finally, as a profession committed to equity, advocacy, and justice, physicians are positioned to lead the way toward racial equity.

Overall, racial and gender diversity in all clinical specialties is improving, but not at the same pace. While the diversity of US medical students and residents by sex and race/ethnicity is greater than among faculty, change in racial diversity has been slow for all 3 groups.8 During the past 40 years the number of full-time faculty has increased 6-fold for females and more than tripled for males.8 However, this rise has not favored URiM faculty, because their proportion is still underrepresented relative to their group in the general population. Clinical departments that are making the most progress in recruiting URiM residents and faculty are often primary or preventive care specialties rather than surgical or service or hospital-based specialties.8,9 ObGyn has consistently had a proportion of URiM residents (18%) that is highest in the surgical specialties and comparable to family medicine and pediatrics.10

When examining physician workforce diversity, it is important to “drill down” to individual specialties to obtain a clearer understanding of trends. The continued need for increased resident and faculty diversity prompted us to examine ObGyn departments. The most recent nationwide data were gathered about full-time faculty from the 2021 AAMC Faculty Roster, residents from the 2021 Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Data Resource Book, medical student matriculants from 2021 AAMC, and US adult women (defined arbitrarily as 15 years or older) from the 2019 American Community Survey.11-13

Increase in female faculty and residents

The expanding numbers of faculty and residents over a 40-year period (from 1973 to 2012) led to more women and underrepresented minorities in ObGyn than in other major clinical departments.14,15 Women now constitute two-thirds of all ObGyn faculty and are more likely to be junior rather than senior faculty.9 When looking at junior faculty, a higher proportion of junior faculty who are URiM are female. While more junior faculty and residents are female, male faculty are also racially and ethnically diverse.9

- ObGyn is a leader in racial/ethnic diversity in academic medicine.

- The rapid rise of faculty numbers in the past has not favored underrepresented faculty.

- The rise in ObGyn faculty and residents, who were predominantly female, has contributed to greater racial/ethnic diversity.

- Improved patient outcomes with racial concordance between physicians and patients have been reported.

- More patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their clinicians.

- Racial/ethnic diversity of junior faculty and residents is similar to medical students.

- The most underrepresented group is Hispanic, due in part to its rapid growth in the US population.

Continue to: Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn...

Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn

The distribution of racial/ethnic groups in 2021 were compared between senior and junior ObGyn faculty and residents with the US adult female population.9 As shown in the FIGURE, the proportion of ObGyn faculty who are White approximates the White US adult female population. The most rapidly growing racial/ethnic group in the US population is Hispanic. Although Hispanic is the best represented ethnicity among junior faculty, the proportions of Hispanics among faculty and residents lag well behind the US population. The proportion of ObGyn faculty who are Black has consistently been less than in the US adult female population. ObGyns who are Asian constitute higher proportions of faculty and residents than in the US adult female population. This finding about Asians is consistent across all clinical specialties.7

Recruiting URiM students into ObGyn is important. Racial and ethnic representation in surgical and nonsurgical residency programs has not substantially improved in the past decade and continues to lag the changing demographics of the US population.10 More students than residents and faculty are Hispanic, which represents a much-needed opportunity for recruitment. By contrast, junior ObGyn faculty are more likely to be Black than residents and students. Native Americans constitute less than 1% of all faculty, residents, students, and US adult females.9 Lastly, race/ethnicity being self-reported as “other” or “unknown” is most common among students and residents, which perhaps represents greater diversity.

Looking back

Increasing diversity in medicine and in ObGyn has not happened by accident. Transformational change requires rectifying any factors that detrimentally affect the racial/ethnic diversity of our medical students, residents, and faculty. For example, biases inherent in key residency application metrics are being recognized, and use of holistic review is increasing. Change is also accelerated by an explicit and public commitment from national organizations. In 2009, the Liaison Committee of Medical Education (LCME) mandated that medical schools engage in practices that focus on recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce. Increases in Black and Hispanic medical students were noted after implementation of this new mandate.16 The ACGME followed suit with similar guidelines in 2019.10

Diversity is one of the foundational strengths of the ObGyn specialty. Important aspects of the specialty are built upon the contributions of women of color, some voluntary and some not. One example is the knowledge of gynecology that was gained through the involuntary and nonanesthetized surgeries performed on

Moving forward

Advancing diversity in ObGyn offers advantages: better representation of patient populations, improving public health by better access to care, enhancing learning in medical education, building more comprehensive research agendas, and driving institutional excellence. While progress has been made, significant work is still to be done. We must continue to critically examine the role of biases and structural racism that are embedded in evaluating medical students, screening of residency applicants, and selecting and retaining faculty. In future work, we should explore the hypothesis that continued change in racial/ethnic diversity of faculty will only occur once more URiM students, especially the growing number of Hispanics, are admitted into medical schools and recruited for residency positions. We should also examine whether further diversity improves patient outcomes.

It is encouraging to realize that ObGyn departments are leaders in racial/ethnic diversity at US medical schools. It is also critical that the specialty commits to the progress that still needs to be made, including increasing diversity among faculty and institutional leadership. To maintain diversity that mirrors the US adult female population, the specialty of ObGyn will require active surveillance and continued recruitment of Black and, especially Hispanic, faculty and residents.19 The national strategies aimed at building medical student and residency diversity are beginning to yield results. For those gains to help faculty diversity, institutional and departmental leaders will need to implement best practices for recruiting, retaining, and advancing URiM faculty.19 Those practices would include making workforce diversity an explicit priority, building diverse applicant pools, and establishing infrastructure and mentorship to advance URiM faculty to senior leadership positions.20

In conclusion

Building a physician workforce that is more representative of the US population should aid in addressing inequalities in health and health care. Significant strides have been made in racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn. This has resulted in a specialty that is among the most diverse in academic medicine. At the same time, there is more work to be done. For example, the specialty is far from reaching racial equity for Hispanic physicians. Also, continued efforts are necessary to advance URiM faculty to leadership positions. The legacy of racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn did not happen by accident and will not be maintained without intention. ●

- Hummes KR, Jones NA, Ramierez RR. United States Census: overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. http//www. census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2022.

- Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Zhang K, et al. AM last page: the urgency of physician workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2014;89:1192.

- Association of American Medical College. Diversity in the physician workforce. Facts & figures 2014. http://www .aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org. Accessed April 9, 2022.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: Diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJ, et al. Community-based education: The influence of role modeling on career choice and practice location. Med Teac. 2017;39:174-180.

- Umbach PD. The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res High Educ. 2006;47:317-345.

- Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Glod SA, et al. General internists as change agents: opportunities and barriers to leadership in health systems and medical education transformation. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1865-1869.

- Xierali IM, Fair MA, Nivet MA. Faculty diversity in U.S. medical schools: Progress and gaps coexist. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2016;16. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/decem ber2016facultydiversityinu.s.medicalschoolsprogressandga ps.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, McDade WA. Racial-ethnic diversity of obstetrics and gynecology faculty at medical schools in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;S00029378(22)00106-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.007.

- Hucko L, Al-khersan H, Lopez Dominguez J, et al. Racial and ethnic diversity of U.S. residency programs, 2011-2019. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:22-23.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets /publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook _document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021

- United States Census Bureau. The 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) Files.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme .org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021 _acgme_databook_document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021.

- Rayburn WF, Liu CQ, Elwell EC, et al. Diversity of physician faculty in obstetrics and gynecology. J Reprod Med. 2016;61:22-26.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Full-time faculty in clinical and basic science departments by sex and underrepresented in medicine status: A 40-year review. Acad Med. 2021;96: 568-575.

- Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer LJ, et al. Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s Diversity Standards and Changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320:2267-2269.

- United States National Library of Medicine. Changing the face of medicine.

- https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_82. html. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- Christmas M. #SayHerName: Should obstetrics and gynecology reckon with the legacy of JM Sims? Reprod Sci. 2021;28:3282-3284.

- Morgan HK, Winkel AF, Bands E, et al. Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in the selection of obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:272-277.

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, et al. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88:405-412.

- Hummes KR, Jones NA, Ramierez RR. United States Census: overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. http//www. census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2022.

- Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Zhang K, et al. AM last page: the urgency of physician workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2014;89:1192.

- Association of American Medical College. Diversity in the physician workforce. Facts & figures 2014. http://www .aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org. Accessed April 9, 2022.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: Diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJ, et al. Community-based education: The influence of role modeling on career choice and practice location. Med Teac. 2017;39:174-180.

- Umbach PD. The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res High Educ. 2006;47:317-345.

- Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Glod SA, et al. General internists as change agents: opportunities and barriers to leadership in health systems and medical education transformation. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1865-1869.

- Xierali IM, Fair MA, Nivet MA. Faculty diversity in U.S. medical schools: Progress and gaps coexist. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2016;16. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/decem ber2016facultydiversityinu.s.medicalschoolsprogressandga ps.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, McDade WA. Racial-ethnic diversity of obstetrics and gynecology faculty at medical schools in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;S00029378(22)00106-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.007.

- Hucko L, Al-khersan H, Lopez Dominguez J, et al. Racial and ethnic diversity of U.S. residency programs, 2011-2019. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:22-23.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets /publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook _document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021

- United States Census Bureau. The 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) Files.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme .org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021 _acgme_databook_document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021.

- Rayburn WF, Liu CQ, Elwell EC, et al. Diversity of physician faculty in obstetrics and gynecology. J Reprod Med. 2016;61:22-26.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Full-time faculty in clinical and basic science departments by sex and underrepresented in medicine status: A 40-year review. Acad Med. 2021;96: 568-575.

- Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer LJ, et al. Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s Diversity Standards and Changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320:2267-2269.

- United States National Library of Medicine. Changing the face of medicine.

- https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_82. html. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- Christmas M. #SayHerName: Should obstetrics and gynecology reckon with the legacy of JM Sims? Reprod Sci. 2021;28:3282-3284.

- Morgan HK, Winkel AF, Bands E, et al. Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in the selection of obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:272-277.

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, et al. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88:405-412.

Retail health clinics: What is their role in ObGyn care?

Retail Health Clinics (RHCs) are health care facilities located in high-traffic retail outlets with adjacent pharmacies that are intended to provide convenient and affordable care without sacrificing quality. The clinics add an option that complements services to individuals and families who otherwise would need to wait for an appointment with a traditional primary care physician or provider.1 Appointments are not necessary for episodic health needs. Usually open 7 days a week, RHCs offer extended hours on weekdays.2

The clinics are staffed by licensed, qualified advance practice providers, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, who are supervised by family physicians where required by state law. These clinicians have advanced education to diagnose, treat, and prescribe for nonemergent ailments such as colds and flu, rashes and skin irritation, and muscle strains or sprains.3 They are supported by an electronic health record that contains established evidence-based protocols.2,4

Evolution of retail health clinics

The first RHC, operated by QuickMedx, opened its doors in 2000 in Minneapolis– St. Paul.1,5 Only patients with a very limited number of illnesses were seen, and payment was cash. In 2005, this clinic was acquired by a major pharmacy retailer, which led to several acquisitions by other retailers and health care systems. In addition to accepting cash for a visit, the clinics formed contracts with health insurance companies. The average cost of a visit to an RHC in 2016 was estimated to be $70, considerably less than the cost at urgent care clinics ($124) and emergency rooms ($356).6

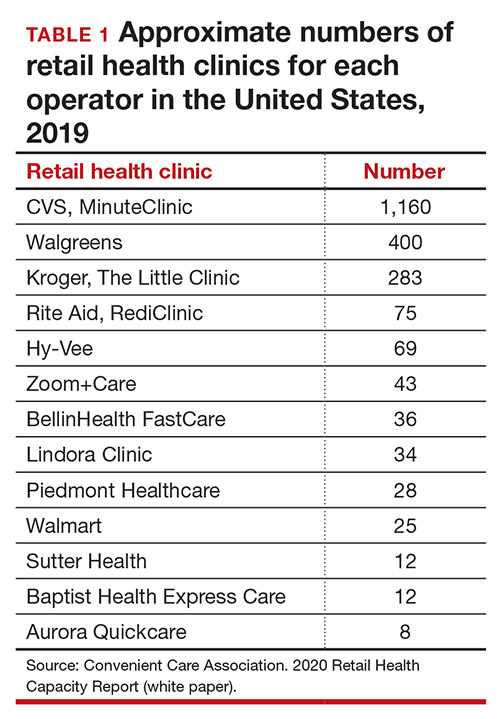

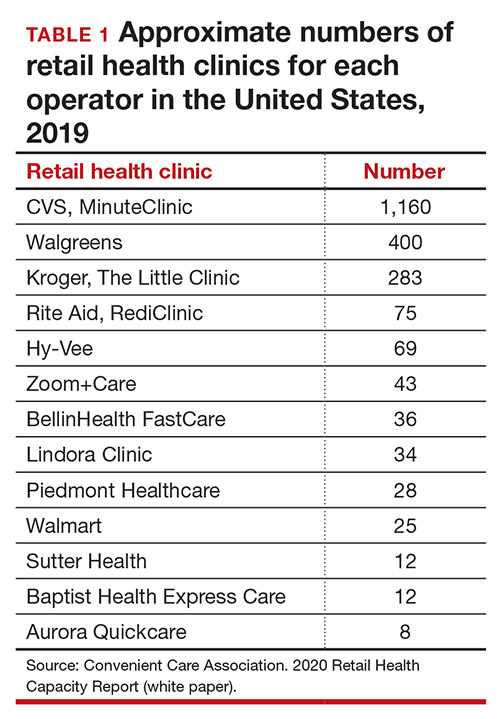

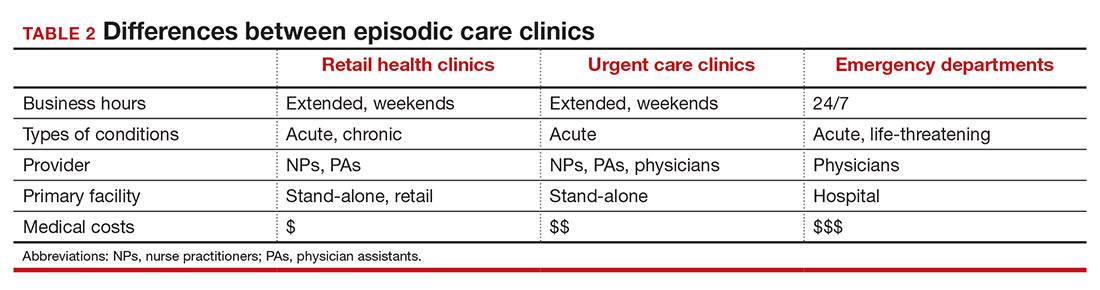

Today, more than 20 companies provide health care services at RHCs (TABLE 1). CVS (MinuteClinic) has the most retail clinics, followed by Walgreens, Kroger, Rite Aid, and Zoom+Care.1,2 There are now about 3,300 clinics in the United States, Canada, and Mexico (nearly all are located in the United States).2 Currently, RHCs are present in 44 states and the District of Columbia. Alabama, Alaska, Idaho, North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming are the only states without an RHC, while large-population states (California, Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas) have experienced an explosion in clinic openings.2

RHCs are found in high foot traffic locations, such as large retailers and grocery stores, and in prioritizing services such as drug stores. By analyzing 2019 clinic openings and population centers, the Convenient Care Association determined that more than half of the US population now lives within a 10-minute drive of an RHC.2 New locations are established on a regular basis, resulting in some flux in the total number of clinics.

Continue to: Services that RHCs provide...

Services that RHCs provide

As RHC locations expand, so do their services. Most RHCs pursue 1 of 2 models: health hubs or virtual care. Health hubs offer an expansion of services, which has resulted in retail health looking and operating more like the primary care providers in their communities.1,2 While most chains intend for patient visits to be brief, the growing health hub model intends to expand the period for patient visits. The major companies, CVS, Kroger, and Walmart, are offering an increase in their services and granting their providers a greater capacity to screen and treat patients for a wider range of conditions. By contrast, other clinic operators, such as Rite Aid RediClinics, are pursuing a more episodic and convenient care model with a greater adoption and expansion of telehealth and telemedicine.

Services at RHCs involve primarily acute care as well as some basic chronic disease management. About 90% of visits are for the following conditions: influenza, immunizations, upper respiratory infections, sinusitis, bronchitis, sore throat, inner ear infection, conjunctivitis, urinary tract infections, and blood tests.1-3 Other services available at most RHC locations involve screening and monitoring, wellness and physicals, travel health, treatment of minor injuries, and vaccinations and injections.

Women constitute half of all customers, and all RHCs offer women’s health services.7 Along with addressing acute care needs, women’s health services include contraception care and options, human papillomavirus (HPV) screening, pregnancy testing and initial prenatal evaluation, and evaluation for and treatment of urinary tract, bladder, and yeast infections.2,6

All RHCs provide counseling on sexual health concerns. Nearly all retail clinics in the United States provide screening and treatment for patients and their partners with sexually transmitted infections. RHC providers are required to follow up with patients regarding any blood work or culture results. When positive test results are confirmed for serious infections, such as hepatitis B and C, syphilis, and HIV, patients customarily are referred for treatment.2

The RHC patient base

RHCs serve an expanding base of patients who cite convenience as their primary motivation for utilizing these clinics. This consumer-driven market now encompasses, by some measures, nearly 50 million visits annually.2 These numbers have risen every year alongside a consistent increase in the number and spread of clinics across the country. During the COVID-19 pandemic, visits declined, consistent with other health care touchpoints, due to concerns about spreading the coronavirus.

The RHC industry has continued to adapt to a changing health care climate by embracing new telehealth solutions, enabling remote care, and expanding services by consumer demand.1,7 While convenience is a primary motivation for visiting an RHC, about two-thirds of RHC patients do not have a primary care provider.1 To support a broader continuum of care, RHCs regularly refer patients who do not have a primary care provider to other health care touchpoints when necessary.

Young and middle-aged adults (18–44 years) comprise the largest group of RHC patients. When patients were asked why they chose an RHC over “traditional doctors’ clinics,” many cited difficulties in accessing care, the appeal of lower costs, and proximity. The proportion of female RHC users was 50.9% and 56.8% for RHC nonusers.1-3

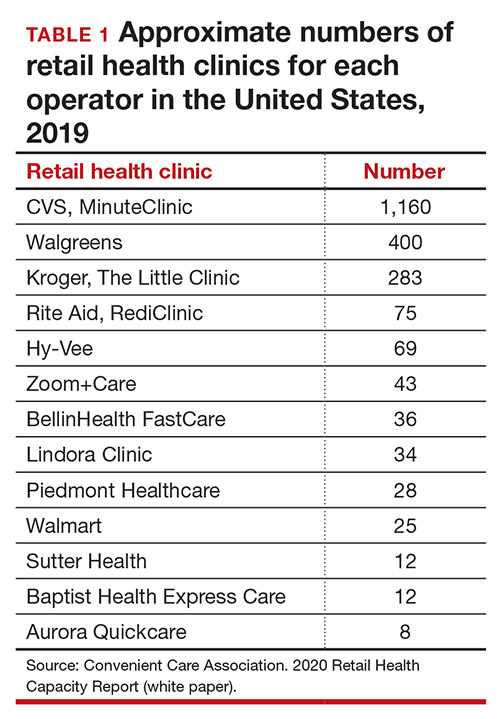

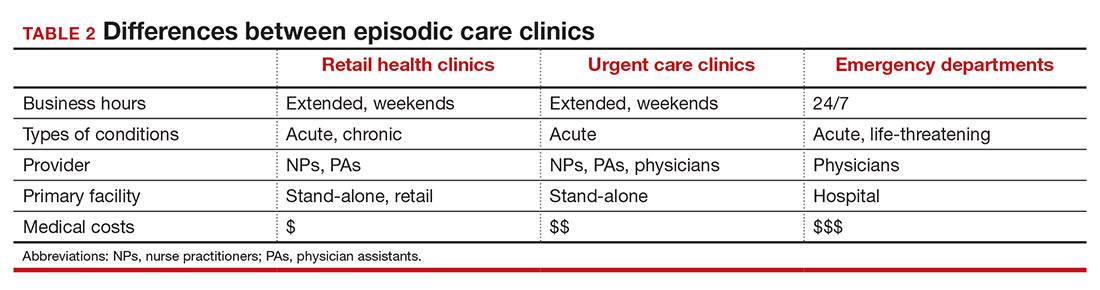

How RHCs compare with other episodic care clinics

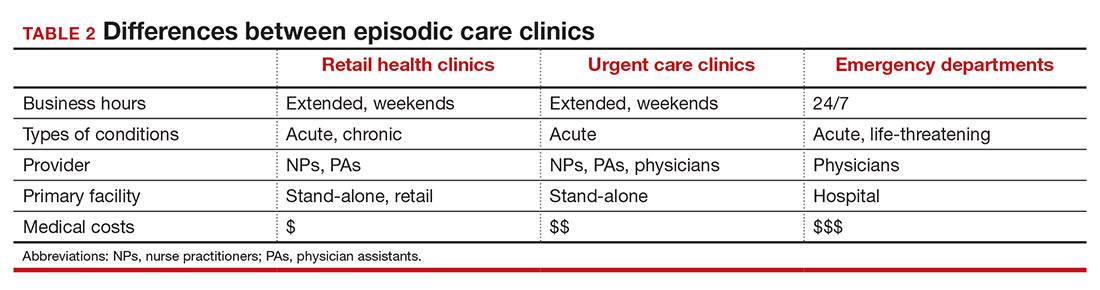

The consumer has more choices to seek episodic care other than at physicians’ clinics or emergency rooms. An RHC, urgent care clinic, or freestanding emergency clinic increase access points for consumers. Along with the expanding number of RHCs, there are nearly 9,000 US urgent care centers, according to the Urgent Care Association, and more than 550 freestanding emergency rooms.8

The main differences between these episodic care clinics are shown in TABLE 2. Hours of operation, types of conditions, available providers, location of the facility, and estimated costs are compared. All provide expanded business hours. Retail clinics address some chronic disease management along with acute care, engage only advanced practitioners, use retail stores, and are less costly to consumers.3,4,9

An RHC, urgent care clinic, or emergency department increases access points for consumers. Many emergency department visits can be handled in ambulatory settings such as RHCs and urgent care clinics.9,10 This can be helpful, especially in rural areas with a shortage of physicians. Most people want a relationship with a physician who will manage their care rather than seeing a different provider at every visit. While ObGyns deliver comprehensive care to women, however, in some underserved areas non-ObGyn clinics can fill the void. For example, RHCs can sometimes provide needed immunizations and health care information required in underserved areas.11

Many physicians are frustrated when they see patients who do not have a complete copy of their medical record and must piecemeal how to treat a patient. RHCs have adopted electronic medical records, and they regularly encourage patients to contact their physician (or find one, which can be difficult). Another limitation can be a referral from an RHC to a subspecialist rather than a primary care physician who could equally handle the condition.

Continue to: What ObGyns can do...

What ObGyns can do

Consumers have become accustomed to obtaining services where and when they want them, and they expect the same from their health care providers. While ObGyn practices are less affected by RHCs than family physicians or general internists, health care delivery in traditional clinics must be user friendly—that is, better, cheaper, and faster—for the patient-consumer to be more satisfied. Looking ahead, a nearby women’s health care group needs to have someone on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. That way, you can tell your patients that they can call you first if they need help. In the case of an ObGyn recommending that a patient go to an RHC or urgent care center, you will be aware of the visit and can follow up with your patient afterward.

Traditional clinics need to create ways for patients with acute illnesses to be seen that same day. Offering extended hours or technology options, such as online support, can help. Text message reminders, same-day access for appointments, and price transparency are necessary. It is important to encourage your women’s health patients to become more responsible for their own health and care, while taking into consideration their social determinants of health. While ObGyns should discuss with their patients when to visit an RHC (especially when their clinic is closed), emphasize that your own clinic is the patient’s medical home and encourage the importance of communicating what occurred during the RHC visit.

Working as a team by communicating well can create a community of health. It would be appropriate for you to represent your group by meeting practitioners at the nearby RHC. Being accessible and helpful would create a friendly and open professional relationship. Conversely, providers at retail clinics need to continually appreciate that women’s health clinics offer more comprehensive care. Select referrals from RHCs would help the most important person, the patient herself. ●

- Bachrach D, Frohlich J, Garcimonde A, et al. Building a culture of health: the value proposition of retail clinics. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Manatt Health. April 2015. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/04/the-value-proposition-of-retail-clinics.html. Accessed March 26, 2021.

- Bronstein N. Convenient Care Association–National Trade Association of Companies and Healthcare Systems for the Convenient Care Industry, January 1, 2020. https://www.ccaclinics.org/about-us/about-cca. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- Mehrotra A, Liu H, Adams JL, et al. Comparing costs and quality of care at retail clinics with that of other medical settings for 3 common illnesses. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:321-328.

- Woodburn JD, Smith KL, Nelson GD. Quality of care in the retail health care setting using national clinical guidelines for acute pharyngitis. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22:457-462.

- Zamosky L. What retail clinic growth can teach physicians about patient demand. Threat or opportunity: retail clinic popularity is about convenience. Med Econ. 2014;91:22-24.

- SolvHealth website. Urgent care center vs emergency room. https://www.solvhealth.com/faq/urgent-care-center-vs-emergency-room. Accessed January, 13, 2021.

- Kvedar J, Coye MJ, Everett W. Connected health: a review of technologies and strategies to improve patient care with telemedicine and telehealth. Health Aff. 2014;33:194-199.

- Urgent Care Association website. Industry news: urgent care industry grows to more than 9,000 centers nationwide. February 24, 2020. https://www.ucaoa.org/About-UCA/Industry-News/ArtMID/10309/ArticleID/1468/INDUSTRY-NEWS-Urgent-Care-Industry-Grows-to-More-than-9000-Centers-Nationwide. Accessed March 26, 2021.

- Sussman A, Dunham L, Snower K, et al. Retail clinic utilization associated with lower total cost of care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:e148-57.

- Weinik RM, Burns RM, Mehrotra A. Many emergency department visits could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics. Health Aff. 2010;29:1630-1636.

- Goad JA, Taitel MS, Fensterheim LE, et al. Vaccinations administered during off-clinic hours at a national community pharmacy: implications for increasing patient access and convenience. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:429-436.

Retail Health Clinics (RHCs) are health care facilities located in high-traffic retail outlets with adjacent pharmacies that are intended to provide convenient and affordable care without sacrificing quality. The clinics add an option that complements services to individuals and families who otherwise would need to wait for an appointment with a traditional primary care physician or provider.1 Appointments are not necessary for episodic health needs. Usually open 7 days a week, RHCs offer extended hours on weekdays.2

The clinics are staffed by licensed, qualified advance practice providers, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, who are supervised by family physicians where required by state law. These clinicians have advanced education to diagnose, treat, and prescribe for nonemergent ailments such as colds and flu, rashes and skin irritation, and muscle strains or sprains.3 They are supported by an electronic health record that contains established evidence-based protocols.2,4

Evolution of retail health clinics

The first RHC, operated by QuickMedx, opened its doors in 2000 in Minneapolis– St. Paul.1,5 Only patients with a very limited number of illnesses were seen, and payment was cash. In 2005, this clinic was acquired by a major pharmacy retailer, which led to several acquisitions by other retailers and health care systems. In addition to accepting cash for a visit, the clinics formed contracts with health insurance companies. The average cost of a visit to an RHC in 2016 was estimated to be $70, considerably less than the cost at urgent care clinics ($124) and emergency rooms ($356).6

Today, more than 20 companies provide health care services at RHCs (TABLE 1). CVS (MinuteClinic) has the most retail clinics, followed by Walgreens, Kroger, Rite Aid, and Zoom+Care.1,2 There are now about 3,300 clinics in the United States, Canada, and Mexico (nearly all are located in the United States).2 Currently, RHCs are present in 44 states and the District of Columbia. Alabama, Alaska, Idaho, North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming are the only states without an RHC, while large-population states (California, Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas) have experienced an explosion in clinic openings.2

RHCs are found in high foot traffic locations, such as large retailers and grocery stores, and in prioritizing services such as drug stores. By analyzing 2019 clinic openings and population centers, the Convenient Care Association determined that more than half of the US population now lives within a 10-minute drive of an RHC.2 New locations are established on a regular basis, resulting in some flux in the total number of clinics.