User login

ObGyn: A leader in academic medicine, with progress still to be made in diversity

The nation’s population is quickly diversifying, making racial/ethnic disparities in health care outcomes even more apparent. Minority and non-English-speaking populations have grown and may become a majority in the next generation.1 A proposed strategy to reduce disparities in health care is to recruit more practitioners who better reflect the patient populations.2 Improved access to care with racial concordance between physicians and patients has been reported.3

Being increasingly aware of access-to-care data, more patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their providers.4 Despite progress (ie, more women entering the medical profession), the proportion of physicians who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM—eg, Black, Hispanic, and Native American) still lags US population demographics.3

Why diversity in medicine matters

In addition to improving access to care, diversity in medicine offers other benefits. Working within diverse learning environments has demonstrated educational advantages.5,6 Medical students and residents from diverse backgrounds are less likely to report depression symptoms, regardless of their race. Diversity may accelerate advancements in health care as well, since it is well-established that diverse teams outperform nondiverse teams when it comes to innovation and productivity.7 Finally, as a profession committed to equity, advocacy, and justice, physicians are positioned to lead the way toward racial equity.

Overall, racial and gender diversity in all clinical specialties is improving, but not at the same pace. While the diversity of US medical students and residents by sex and race/ethnicity is greater than among faculty, change in racial diversity has been slow for all 3 groups.8 During the past 40 years the number of full-time faculty has increased 6-fold for females and more than tripled for males.8 However, this rise has not favored URiM faculty, because their proportion is still underrepresented relative to their group in the general population. Clinical departments that are making the most progress in recruiting URiM residents and faculty are often primary or preventive care specialties rather than surgical or service or hospital-based specialties.8,9 ObGyn has consistently had a proportion of URiM residents (18%) that is highest in the surgical specialties and comparable to family medicine and pediatrics.10

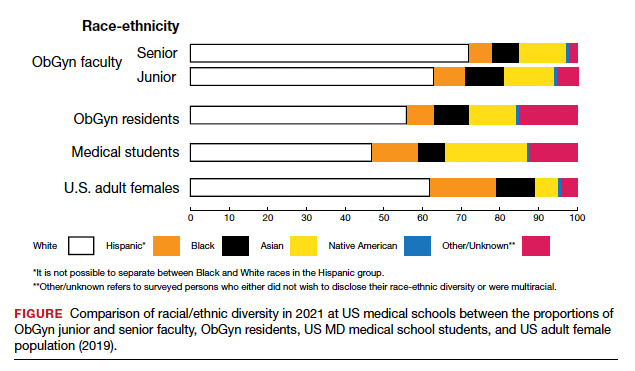

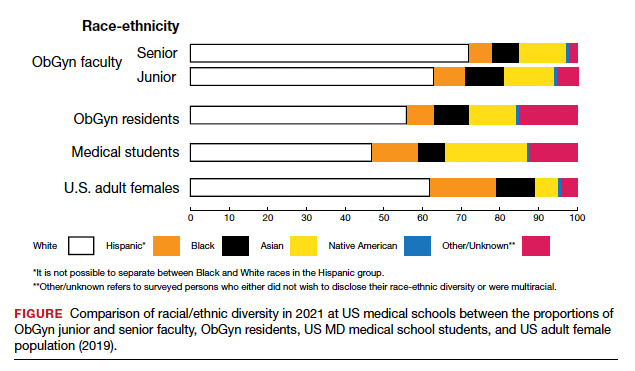

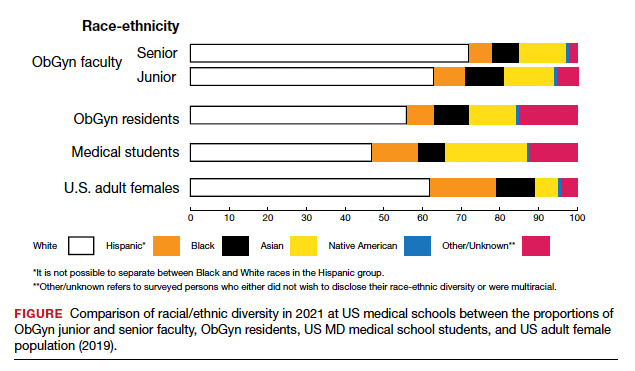

When examining physician workforce diversity, it is important to “drill down” to individual specialties to obtain a clearer understanding of trends. The continued need for increased resident and faculty diversity prompted us to examine ObGyn departments. The most recent nationwide data were gathered about full-time faculty from the 2021 AAMC Faculty Roster, residents from the 2021 Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Data Resource Book, medical student matriculants from 2021 AAMC, and US adult women (defined arbitrarily as 15 years or older) from the 2019 American Community Survey.11-13

Increase in female faculty and residents

The expanding numbers of faculty and residents over a 40-year period (from 1973 to 2012) led to more women and underrepresented minorities in ObGyn than in other major clinical departments.14,15 Women now constitute two-thirds of all ObGyn faculty and are more likely to be junior rather than senior faculty.9 When looking at junior faculty, a higher proportion of junior faculty who are URiM are female. While more junior faculty and residents are female, male faculty are also racially and ethnically diverse.9

- ObGyn is a leader in racial/ethnic diversity in academic medicine.

- The rapid rise of faculty numbers in the past has not favored underrepresented faculty.

- The rise in ObGyn faculty and residents, who were predominantly female, has contributed to greater racial/ethnic diversity.

- Improved patient outcomes with racial concordance between physicians and patients have been reported.

- More patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their clinicians.

- Racial/ethnic diversity of junior faculty and residents is similar to medical students.

- The most underrepresented group is Hispanic, due in part to its rapid growth in the US population.

Continue to: Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn...

Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn

The distribution of racial/ethnic groups in 2021 were compared between senior and junior ObGyn faculty and residents with the US adult female population.9 As shown in the FIGURE, the proportion of ObGyn faculty who are White approximates the White US adult female population. The most rapidly growing racial/ethnic group in the US population is Hispanic. Although Hispanic is the best represented ethnicity among junior faculty, the proportions of Hispanics among faculty and residents lag well behind the US population. The proportion of ObGyn faculty who are Black has consistently been less than in the US adult female population. ObGyns who are Asian constitute higher proportions of faculty and residents than in the US adult female population. This finding about Asians is consistent across all clinical specialties.7

Recruiting URiM students into ObGyn is important. Racial and ethnic representation in surgical and nonsurgical residency programs has not substantially improved in the past decade and continues to lag the changing demographics of the US population.10 More students than residents and faculty are Hispanic, which represents a much-needed opportunity for recruitment. By contrast, junior ObGyn faculty are more likely to be Black than residents and students. Native Americans constitute less than 1% of all faculty, residents, students, and US adult females.9 Lastly, race/ethnicity being self-reported as “other” or “unknown” is most common among students and residents, which perhaps represents greater diversity.

Looking back

Increasing diversity in medicine and in ObGyn has not happened by accident. Transformational change requires rectifying any factors that detrimentally affect the racial/ethnic diversity of our medical students, residents, and faculty. For example, biases inherent in key residency application metrics are being recognized, and use of holistic review is increasing. Change is also accelerated by an explicit and public commitment from national organizations. In 2009, the Liaison Committee of Medical Education (LCME) mandated that medical schools engage in practices that focus on recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce. Increases in Black and Hispanic medical students were noted after implementation of this new mandate.16 The ACGME followed suit with similar guidelines in 2019.10

Diversity is one of the foundational strengths of the ObGyn specialty. Important aspects of the specialty are built upon the contributions of women of color, some voluntary and some not. One example is the knowledge of gynecology that was gained through the involuntary and nonanesthetized surgeries performed on

Moving forward

Advancing diversity in ObGyn offers advantages: better representation of patient populations, improving public health by better access to care, enhancing learning in medical education, building more comprehensive research agendas, and driving institutional excellence. While progress has been made, significant work is still to be done. We must continue to critically examine the role of biases and structural racism that are embedded in evaluating medical students, screening of residency applicants, and selecting and retaining faculty. In future work, we should explore the hypothesis that continued change in racial/ethnic diversity of faculty will only occur once more URiM students, especially the growing number of Hispanics, are admitted into medical schools and recruited for residency positions. We should also examine whether further diversity improves patient outcomes.

It is encouraging to realize that ObGyn departments are leaders in racial/ethnic diversity at US medical schools. It is also critical that the specialty commits to the progress that still needs to be made, including increasing diversity among faculty and institutional leadership. To maintain diversity that mirrors the US adult female population, the specialty of ObGyn will require active surveillance and continued recruitment of Black and, especially Hispanic, faculty and residents.19 The national strategies aimed at building medical student and residency diversity are beginning to yield results. For those gains to help faculty diversity, institutional and departmental leaders will need to implement best practices for recruiting, retaining, and advancing URiM faculty.19 Those practices would include making workforce diversity an explicit priority, building diverse applicant pools, and establishing infrastructure and mentorship to advance URiM faculty to senior leadership positions.20

In conclusion

Building a physician workforce that is more representative of the US population should aid in addressing inequalities in health and health care. Significant strides have been made in racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn. This has resulted in a specialty that is among the most diverse in academic medicine. At the same time, there is more work to be done. For example, the specialty is far from reaching racial equity for Hispanic physicians. Also, continued efforts are necessary to advance URiM faculty to leadership positions. The legacy of racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn did not happen by accident and will not be maintained without intention. ●

- Hummes KR, Jones NA, Ramierez RR. United States Census: overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. http//www. census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2022.

- Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Zhang K, et al. AM last page: the urgency of physician workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2014;89:1192.

- Association of American Medical College. Diversity in the physician workforce. Facts & figures 2014. http://www .aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org. Accessed April 9, 2022.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: Diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJ, et al. Community-based education: The influence of role modeling on career choice and practice location. Med Teac. 2017;39:174-180.

- Umbach PD. The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res High Educ. 2006;47:317-345.

- Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Glod SA, et al. General internists as change agents: opportunities and barriers to leadership in health systems and medical education transformation. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1865-1869.

- Xierali IM, Fair MA, Nivet MA. Faculty diversity in U.S. medical schools: Progress and gaps coexist. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2016;16. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/decem ber2016facultydiversityinu.s.medicalschoolsprogressandga ps.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, McDade WA. Racial-ethnic diversity of obstetrics and gynecology faculty at medical schools in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;S00029378(22)00106-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.007.

- Hucko L, Al-khersan H, Lopez Dominguez J, et al. Racial and ethnic diversity of U.S. residency programs, 2011-2019. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:22-23.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets /publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook _document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021

- United States Census Bureau. The 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) Files.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme .org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021 _acgme_databook_document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021.

- Rayburn WF, Liu CQ, Elwell EC, et al. Diversity of physician faculty in obstetrics and gynecology. J Reprod Med. 2016;61:22-26.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Full-time faculty in clinical and basic science departments by sex and underrepresented in medicine status: A 40-year review. Acad Med. 2021;96: 568-575.

- Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer LJ, et al. Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s Diversity Standards and Changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320:2267-2269.

- United States National Library of Medicine. Changing the face of medicine.

- https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_82. html. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- Christmas M. #SayHerName: Should obstetrics and gynecology reckon with the legacy of JM Sims? Reprod Sci. 2021;28:3282-3284.

- Morgan HK, Winkel AF, Bands E, et al. Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in the selection of obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:272-277.

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, et al. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88:405-412.

The nation’s population is quickly diversifying, making racial/ethnic disparities in health care outcomes even more apparent. Minority and non-English-speaking populations have grown and may become a majority in the next generation.1 A proposed strategy to reduce disparities in health care is to recruit more practitioners who better reflect the patient populations.2 Improved access to care with racial concordance between physicians and patients has been reported.3

Being increasingly aware of access-to-care data, more patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their providers.4 Despite progress (ie, more women entering the medical profession), the proportion of physicians who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM—eg, Black, Hispanic, and Native American) still lags US population demographics.3

Why diversity in medicine matters

In addition to improving access to care, diversity in medicine offers other benefits. Working within diverse learning environments has demonstrated educational advantages.5,6 Medical students and residents from diverse backgrounds are less likely to report depression symptoms, regardless of their race. Diversity may accelerate advancements in health care as well, since it is well-established that diverse teams outperform nondiverse teams when it comes to innovation and productivity.7 Finally, as a profession committed to equity, advocacy, and justice, physicians are positioned to lead the way toward racial equity.

Overall, racial and gender diversity in all clinical specialties is improving, but not at the same pace. While the diversity of US medical students and residents by sex and race/ethnicity is greater than among faculty, change in racial diversity has been slow for all 3 groups.8 During the past 40 years the number of full-time faculty has increased 6-fold for females and more than tripled for males.8 However, this rise has not favored URiM faculty, because their proportion is still underrepresented relative to their group in the general population. Clinical departments that are making the most progress in recruiting URiM residents and faculty are often primary or preventive care specialties rather than surgical or service or hospital-based specialties.8,9 ObGyn has consistently had a proportion of URiM residents (18%) that is highest in the surgical specialties and comparable to family medicine and pediatrics.10

When examining physician workforce diversity, it is important to “drill down” to individual specialties to obtain a clearer understanding of trends. The continued need for increased resident and faculty diversity prompted us to examine ObGyn departments. The most recent nationwide data were gathered about full-time faculty from the 2021 AAMC Faculty Roster, residents from the 2021 Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Data Resource Book, medical student matriculants from 2021 AAMC, and US adult women (defined arbitrarily as 15 years or older) from the 2019 American Community Survey.11-13

Increase in female faculty and residents

The expanding numbers of faculty and residents over a 40-year period (from 1973 to 2012) led to more women and underrepresented minorities in ObGyn than in other major clinical departments.14,15 Women now constitute two-thirds of all ObGyn faculty and are more likely to be junior rather than senior faculty.9 When looking at junior faculty, a higher proportion of junior faculty who are URiM are female. While more junior faculty and residents are female, male faculty are also racially and ethnically diverse.9

- ObGyn is a leader in racial/ethnic diversity in academic medicine.

- The rapid rise of faculty numbers in the past has not favored underrepresented faculty.

- The rise in ObGyn faculty and residents, who were predominantly female, has contributed to greater racial/ethnic diversity.

- Improved patient outcomes with racial concordance between physicians and patients have been reported.

- More patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their clinicians.

- Racial/ethnic diversity of junior faculty and residents is similar to medical students.

- The most underrepresented group is Hispanic, due in part to its rapid growth in the US population.

Continue to: Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn...

Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn

The distribution of racial/ethnic groups in 2021 were compared between senior and junior ObGyn faculty and residents with the US adult female population.9 As shown in the FIGURE, the proportion of ObGyn faculty who are White approximates the White US adult female population. The most rapidly growing racial/ethnic group in the US population is Hispanic. Although Hispanic is the best represented ethnicity among junior faculty, the proportions of Hispanics among faculty and residents lag well behind the US population. The proportion of ObGyn faculty who are Black has consistently been less than in the US adult female population. ObGyns who are Asian constitute higher proportions of faculty and residents than in the US adult female population. This finding about Asians is consistent across all clinical specialties.7

Recruiting URiM students into ObGyn is important. Racial and ethnic representation in surgical and nonsurgical residency programs has not substantially improved in the past decade and continues to lag the changing demographics of the US population.10 More students than residents and faculty are Hispanic, which represents a much-needed opportunity for recruitment. By contrast, junior ObGyn faculty are more likely to be Black than residents and students. Native Americans constitute less than 1% of all faculty, residents, students, and US adult females.9 Lastly, race/ethnicity being self-reported as “other” or “unknown” is most common among students and residents, which perhaps represents greater diversity.

Looking back

Increasing diversity in medicine and in ObGyn has not happened by accident. Transformational change requires rectifying any factors that detrimentally affect the racial/ethnic diversity of our medical students, residents, and faculty. For example, biases inherent in key residency application metrics are being recognized, and use of holistic review is increasing. Change is also accelerated by an explicit and public commitment from national organizations. In 2009, the Liaison Committee of Medical Education (LCME) mandated that medical schools engage in practices that focus on recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce. Increases in Black and Hispanic medical students were noted after implementation of this new mandate.16 The ACGME followed suit with similar guidelines in 2019.10

Diversity is one of the foundational strengths of the ObGyn specialty. Important aspects of the specialty are built upon the contributions of women of color, some voluntary and some not. One example is the knowledge of gynecology that was gained through the involuntary and nonanesthetized surgeries performed on

Moving forward

Advancing diversity in ObGyn offers advantages: better representation of patient populations, improving public health by better access to care, enhancing learning in medical education, building more comprehensive research agendas, and driving institutional excellence. While progress has been made, significant work is still to be done. We must continue to critically examine the role of biases and structural racism that are embedded in evaluating medical students, screening of residency applicants, and selecting and retaining faculty. In future work, we should explore the hypothesis that continued change in racial/ethnic diversity of faculty will only occur once more URiM students, especially the growing number of Hispanics, are admitted into medical schools and recruited for residency positions. We should also examine whether further diversity improves patient outcomes.

It is encouraging to realize that ObGyn departments are leaders in racial/ethnic diversity at US medical schools. It is also critical that the specialty commits to the progress that still needs to be made, including increasing diversity among faculty and institutional leadership. To maintain diversity that mirrors the US adult female population, the specialty of ObGyn will require active surveillance and continued recruitment of Black and, especially Hispanic, faculty and residents.19 The national strategies aimed at building medical student and residency diversity are beginning to yield results. For those gains to help faculty diversity, institutional and departmental leaders will need to implement best practices for recruiting, retaining, and advancing URiM faculty.19 Those practices would include making workforce diversity an explicit priority, building diverse applicant pools, and establishing infrastructure and mentorship to advance URiM faculty to senior leadership positions.20

In conclusion

Building a physician workforce that is more representative of the US population should aid in addressing inequalities in health and health care. Significant strides have been made in racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn. This has resulted in a specialty that is among the most diverse in academic medicine. At the same time, there is more work to be done. For example, the specialty is far from reaching racial equity for Hispanic physicians. Also, continued efforts are necessary to advance URiM faculty to leadership positions. The legacy of racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn did not happen by accident and will not be maintained without intention. ●

The nation’s population is quickly diversifying, making racial/ethnic disparities in health care outcomes even more apparent. Minority and non-English-speaking populations have grown and may become a majority in the next generation.1 A proposed strategy to reduce disparities in health care is to recruit more practitioners who better reflect the patient populations.2 Improved access to care with racial concordance between physicians and patients has been reported.3

Being increasingly aware of access-to-care data, more patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their providers.4 Despite progress (ie, more women entering the medical profession), the proportion of physicians who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM—eg, Black, Hispanic, and Native American) still lags US population demographics.3

Why diversity in medicine matters

In addition to improving access to care, diversity in medicine offers other benefits. Working within diverse learning environments has demonstrated educational advantages.5,6 Medical students and residents from diverse backgrounds are less likely to report depression symptoms, regardless of their race. Diversity may accelerate advancements in health care as well, since it is well-established that diverse teams outperform nondiverse teams when it comes to innovation and productivity.7 Finally, as a profession committed to equity, advocacy, and justice, physicians are positioned to lead the way toward racial equity.

Overall, racial and gender diversity in all clinical specialties is improving, but not at the same pace. While the diversity of US medical students and residents by sex and race/ethnicity is greater than among faculty, change in racial diversity has been slow for all 3 groups.8 During the past 40 years the number of full-time faculty has increased 6-fold for females and more than tripled for males.8 However, this rise has not favored URiM faculty, because their proportion is still underrepresented relative to their group in the general population. Clinical departments that are making the most progress in recruiting URiM residents and faculty are often primary or preventive care specialties rather than surgical or service or hospital-based specialties.8,9 ObGyn has consistently had a proportion of URiM residents (18%) that is highest in the surgical specialties and comparable to family medicine and pediatrics.10

When examining physician workforce diversity, it is important to “drill down” to individual specialties to obtain a clearer understanding of trends. The continued need for increased resident and faculty diversity prompted us to examine ObGyn departments. The most recent nationwide data were gathered about full-time faculty from the 2021 AAMC Faculty Roster, residents from the 2021 Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Data Resource Book, medical student matriculants from 2021 AAMC, and US adult women (defined arbitrarily as 15 years or older) from the 2019 American Community Survey.11-13

Increase in female faculty and residents

The expanding numbers of faculty and residents over a 40-year period (from 1973 to 2012) led to more women and underrepresented minorities in ObGyn than in other major clinical departments.14,15 Women now constitute two-thirds of all ObGyn faculty and are more likely to be junior rather than senior faculty.9 When looking at junior faculty, a higher proportion of junior faculty who are URiM are female. While more junior faculty and residents are female, male faculty are also racially and ethnically diverse.9

- ObGyn is a leader in racial/ethnic diversity in academic medicine.

- The rapid rise of faculty numbers in the past has not favored underrepresented faculty.

- The rise in ObGyn faculty and residents, who were predominantly female, has contributed to greater racial/ethnic diversity.

- Improved patient outcomes with racial concordance between physicians and patients have been reported.

- More patients are advocating and asking for physicians of color to be their clinicians.

- Racial/ethnic diversity of junior faculty and residents is similar to medical students.

- The most underrepresented group is Hispanic, due in part to its rapid growth in the US population.

Continue to: Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn...

Growth of URiM physicians in ObGyn

The distribution of racial/ethnic groups in 2021 were compared between senior and junior ObGyn faculty and residents with the US adult female population.9 As shown in the FIGURE, the proportion of ObGyn faculty who are White approximates the White US adult female population. The most rapidly growing racial/ethnic group in the US population is Hispanic. Although Hispanic is the best represented ethnicity among junior faculty, the proportions of Hispanics among faculty and residents lag well behind the US population. The proportion of ObGyn faculty who are Black has consistently been less than in the US adult female population. ObGyns who are Asian constitute higher proportions of faculty and residents than in the US adult female population. This finding about Asians is consistent across all clinical specialties.7

Recruiting URiM students into ObGyn is important. Racial and ethnic representation in surgical and nonsurgical residency programs has not substantially improved in the past decade and continues to lag the changing demographics of the US population.10 More students than residents and faculty are Hispanic, which represents a much-needed opportunity for recruitment. By contrast, junior ObGyn faculty are more likely to be Black than residents and students. Native Americans constitute less than 1% of all faculty, residents, students, and US adult females.9 Lastly, race/ethnicity being self-reported as “other” or “unknown” is most common among students and residents, which perhaps represents greater diversity.

Looking back

Increasing diversity in medicine and in ObGyn has not happened by accident. Transformational change requires rectifying any factors that detrimentally affect the racial/ethnic diversity of our medical students, residents, and faculty. For example, biases inherent in key residency application metrics are being recognized, and use of holistic review is increasing. Change is also accelerated by an explicit and public commitment from national organizations. In 2009, the Liaison Committee of Medical Education (LCME) mandated that medical schools engage in practices that focus on recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce. Increases in Black and Hispanic medical students were noted after implementation of this new mandate.16 The ACGME followed suit with similar guidelines in 2019.10

Diversity is one of the foundational strengths of the ObGyn specialty. Important aspects of the specialty are built upon the contributions of women of color, some voluntary and some not. One example is the knowledge of gynecology that was gained through the involuntary and nonanesthetized surgeries performed on

Moving forward

Advancing diversity in ObGyn offers advantages: better representation of patient populations, improving public health by better access to care, enhancing learning in medical education, building more comprehensive research agendas, and driving institutional excellence. While progress has been made, significant work is still to be done. We must continue to critically examine the role of biases and structural racism that are embedded in evaluating medical students, screening of residency applicants, and selecting and retaining faculty. In future work, we should explore the hypothesis that continued change in racial/ethnic diversity of faculty will only occur once more URiM students, especially the growing number of Hispanics, are admitted into medical schools and recruited for residency positions. We should also examine whether further diversity improves patient outcomes.

It is encouraging to realize that ObGyn departments are leaders in racial/ethnic diversity at US medical schools. It is also critical that the specialty commits to the progress that still needs to be made, including increasing diversity among faculty and institutional leadership. To maintain diversity that mirrors the US adult female population, the specialty of ObGyn will require active surveillance and continued recruitment of Black and, especially Hispanic, faculty and residents.19 The national strategies aimed at building medical student and residency diversity are beginning to yield results. For those gains to help faculty diversity, institutional and departmental leaders will need to implement best practices for recruiting, retaining, and advancing URiM faculty.19 Those practices would include making workforce diversity an explicit priority, building diverse applicant pools, and establishing infrastructure and mentorship to advance URiM faculty to senior leadership positions.20

In conclusion

Building a physician workforce that is more representative of the US population should aid in addressing inequalities in health and health care. Significant strides have been made in racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn. This has resulted in a specialty that is among the most diverse in academic medicine. At the same time, there is more work to be done. For example, the specialty is far from reaching racial equity for Hispanic physicians. Also, continued efforts are necessary to advance URiM faculty to leadership positions. The legacy of racial/ethnic diversity in ObGyn did not happen by accident and will not be maintained without intention. ●

- Hummes KR, Jones NA, Ramierez RR. United States Census: overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. http//www. census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2022.

- Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Zhang K, et al. AM last page: the urgency of physician workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2014;89:1192.

- Association of American Medical College. Diversity in the physician workforce. Facts & figures 2014. http://www .aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org. Accessed April 9, 2022.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: Diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJ, et al. Community-based education: The influence of role modeling on career choice and practice location. Med Teac. 2017;39:174-180.

- Umbach PD. The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res High Educ. 2006;47:317-345.

- Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Glod SA, et al. General internists as change agents: opportunities and barriers to leadership in health systems and medical education transformation. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1865-1869.

- Xierali IM, Fair MA, Nivet MA. Faculty diversity in U.S. medical schools: Progress and gaps coexist. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2016;16. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/decem ber2016facultydiversityinu.s.medicalschoolsprogressandga ps.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, McDade WA. Racial-ethnic diversity of obstetrics and gynecology faculty at medical schools in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;S00029378(22)00106-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.007.

- Hucko L, Al-khersan H, Lopez Dominguez J, et al. Racial and ethnic diversity of U.S. residency programs, 2011-2019. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:22-23.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets /publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook _document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021

- United States Census Bureau. The 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) Files.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme .org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021 _acgme_databook_document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021.

- Rayburn WF, Liu CQ, Elwell EC, et al. Diversity of physician faculty in obstetrics and gynecology. J Reprod Med. 2016;61:22-26.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Full-time faculty in clinical and basic science departments by sex and underrepresented in medicine status: A 40-year review. Acad Med. 2021;96: 568-575.

- Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer LJ, et al. Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s Diversity Standards and Changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320:2267-2269.

- United States National Library of Medicine. Changing the face of medicine.

- https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_82. html. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- Christmas M. #SayHerName: Should obstetrics and gynecology reckon with the legacy of JM Sims? Reprod Sci. 2021;28:3282-3284.

- Morgan HK, Winkel AF, Bands E, et al. Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in the selection of obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:272-277.

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, et al. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88:405-412.

- Hummes KR, Jones NA, Ramierez RR. United States Census: overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. http//www. census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2022.

- Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, Zhang K, et al. AM last page: the urgency of physician workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2014;89:1192.

- Association of American Medical College. Diversity in the physician workforce. Facts & figures 2014. http://www .aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org. Accessed April 9, 2022.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, et al. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: Diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174:289-291.

- Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJ, et al. Community-based education: The influence of role modeling on career choice and practice location. Med Teac. 2017;39:174-180.

- Umbach PD. The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res High Educ. 2006;47:317-345.

- Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Glod SA, et al. General internists as change agents: opportunities and barriers to leadership in health systems and medical education transformation. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1865-1869.

- Xierali IM, Fair MA, Nivet MA. Faculty diversity in U.S. medical schools: Progress and gaps coexist. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2016;16. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/decem ber2016facultydiversityinu.s.medicalschoolsprogressandga ps.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, McDade WA. Racial-ethnic diversity of obstetrics and gynecology faculty at medical schools in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;S00029378(22)00106-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.007.

- Hucko L, Al-khersan H, Lopez Dominguez J, et al. Racial and ethnic diversity of U.S. residency programs, 2011-2019. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:22-23.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets /publicationsbooks/2020-2021_acgme_databook _document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021

- United States Census Bureau. The 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) Files.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2020-2021. https://www.acgme .org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2020-2021 _acgme_databook_document.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2021.

- Rayburn WF, Liu CQ, Elwell EC, et al. Diversity of physician faculty in obstetrics and gynecology. J Reprod Med. 2016;61:22-26.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Full-time faculty in clinical and basic science departments by sex and underrepresented in medicine status: A 40-year review. Acad Med. 2021;96: 568-575.

- Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer LJ, et al. Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s Diversity Standards and Changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320:2267-2269.

- United States National Library of Medicine. Changing the face of medicine.

- https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_82. html. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- Christmas M. #SayHerName: Should obstetrics and gynecology reckon with the legacy of JM Sims? Reprod Sci. 2021;28:3282-3284.

- Morgan HK, Winkel AF, Bands E, et al. Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in the selection of obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:272-277.

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, et al. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88:405-412.