User login

Timing of Blood Pressure Dosing Doesn’t Matter (Again): BedMed and BedMed-Frail

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: I’m joined today by Dr. Scott R. Garrison, MD, PhD. He is a professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and director of the Pragmatic Trials Collaborative.

You presented two studies at ESC. One is the BedMed study, comparing day vs nighttime dosing of blood pressure therapy. Can you tell us the top-line findings?

BedMed and BedMed-Frail

Dr. Garrison: We were looking to validate an earlier study that suggested a large benefit of taking blood pressure medication at bedtime, as far as reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs). That was the MAPEC study. They suggested a 60% reduction. The BedMed trial was in hypertensive primary care patients in five Canadian provinces. We randomized well over 3000 patients to bedtime or morning medications. We looked at MACEs — so all-cause death or hospitalizations for acute coronary syndrome, stroke, or heart failure, and a bunch of safety outcomes.

Essentially, . It was safe to take it at bedtime. But it did not convey any extra cardiovascular benefit.

Ms. Ward: And then you did a second study, called BedMed-Frail. Do you want to tell us the reason you did that?

Dr. Garrison: BedMed-Frail took place in a nursing home population. We believed that it was possible that frail, older adults might have very different risks and benefits, and that they would probably be underrepresented, as they normally are in the main trial.

We thought that because bedtime blood pressure medications would be theoretically preferentially lowering night pressure, which is already the lowest pressure of the day, that if you were at risk for hypotensive or ischemic adverse events, that might make it worse. We looked at falls and fractures; worsening cognition in case they had vascular dementia; and whether they developed decubitus ulcers (pressure sores) because you need a certain amount of pressure to get past any obstruction — in this case, it’s the weight of your body if you’re lying in bed all the time.

We also looked at problem behaviors. People who have dementia have what’s called “sundowning,” where agitation and confusion are worse as the evening is going on. We looked at that on the off chance that it had anything to do with blood pressures being lower. And the BedMed-Frail results mirror those of BedMed exactly. So there was no cardiovascular benefit, and in this population, that was largely driven by mortality; one third of these people died every year.

Ms. Ward: The median age was about 88?

Dr. Garrison: Yes, the median age was 88. There was no cardiovascular mortality advantage to bedtime dosing, but neither was there any signal of safety concerns.

Other Complementary and Conflicting Studies

Ms. Ward: These two studies mirror the TIME study from the United Kingdom.

Dr. Garrison: Yes. We found exactly what TIME found. Our point estimate was pretty much the same. The hazard ratio in the main trial was 0.96. Theirs, I believe, was 0.95. Our findings agree completely with those of TIME and differ substantially from the previous trials that suggested a large benefit.

Ms. Ward: Those previous trials were MAPEC and the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial.

Dr. Garrison: MAPEC was the first one. While we were doing our trial, and while the TIME investigators were doing their trial, both of us trying to validate MAPEC, the same group published another study called Hygia, which also reported a large reduction: a 45% reduction in MACE with bedtime dosing.

Ms. Ward: You didn’t present it, but there was also a meta-analysis presented here by somebody independent.

Dr. Garrison: Yes, Ricky Turgeon. I know Ricky. We gave him patient-level data for his meta-analysis, but I was not otherwise involved.

Ms. Ward: And the conclusion is the same.

Dr. Garrison: It’s the same. He only found the same five trials: MAPEC, Hygia, TIME, BedMed, and BedMed-Frail. Combining them all together, the CIs still span 1.0, so it didn’t end up being significant. But he also analyzed TIME and the BedMed trials separately — again suggesting that those trials showed no benefit.

Ms. Ward: There was a TIME substudy of night owls vs early risers or morning people, and there was a hint (or whatever you should say for a subanalysis of a neutral trial) that timing might make a difference there.

Dr. Garrison: They recently published, I guess it is a substudy, where they looked at people’s chronotype according to whether you consider yourself an early bird or a night owl. Their assessment was more detailed. They reported that if people were tending toward being early birds and they took their blood pressure medicine in the morning, or if they were night owls and they took it in the evening, that they tended to have statistically significantly better outcomes than the opposite timing. In that analysis, they were only looking at nonfatal myocardial infarction and nonfatal stroke.

We did ask something that was related. We asked people: “Do we consider yourself more of an early bird or a night owl?” So we do have those data. For what I presented at ESC, we just looked at the primary outcome; we did subgroups according to early bird, night owl, and neither, and that was not statistically significant. It didn’t rule it out. There were some trends in the direction that the TIME group were suggesting. We do intend to do a closer look at that.

But, you know, they call these “late-breaking trials,” and it really was in our case. We didn’t get the last of our data from the last province until the end of June, so we still are finishing up the analysis of the chronotype portion — so more to come in another month or so.

Do What You Like, or Stick to Morning Dosing?

Ms. Ward: For the purposes of people’s take-home message, does this mostly apply to once-daily–dosed antihypertensives?

Dr. Garrison: It was essentially once-daily medicines that were changed. The docs did have the opportunity to consolidate twice-daily meds into once-daily or switch to a different medication. That’s probably the area where adherence was the biggest issue, because it’s largely beta-blockers that were given twice daily at baseline, and they were less likely to want to change.

At 6 months, 83% of once-daily medications were taken per allocation in the bedtime group and 95% per allocation in the morning group, which was actually pretty good. For angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium-channel blockers, the adherence was excellent. Again, it was beta-blockers taken twice a day where it fell down, and then also diuretics. But if you combine all diuretic medications (ie, pure diuretics and combo agents), still, 75% of them were successful at taking them at bedtime. Only 15% of people switching a diuretic to bedtime dosing actually had problems with nocturia. Most physicians think that they can’t get their patients to take those meds at bedtime, but you can. There’s probably no reason to take it at bedtime, but most people do tolerate it.

Ms. Ward: Is your advice to take it whenever you feel like? I know when TIME came out, Professor George Stergiou, who’s the incoming president of the International Society of Hypertension, said, well, maybe we should stick with the morning, because that’s what most of the trials did.

Dr. Garrison: I think that›s a perfectly valid point of view, and maybe for a lot of people, that could be the default. There are some people, though, who will have a particular reason why one time is better. For instance, most people have no problems with calcium-channel blockers, but some get ankle swelling and you’re more likely to have that happen if you take them in the morning. Or lots of people want to take all their pills at the same time; blood pressure pills are easy ones to switch the timing of if you’re trying to accomplish that, and if that will help adherence. Basically, whatever time of day you can remember to take it the best is probably the right time.

Ms. Ward: Given where we are today, with your trials and TIME, do you think this is now settled science that it doesn’t make a difference?

Dr. Garrison: I’m probably the wrong person to ask, because I clearly have a bias. I think the methods in the TIME trial are really transparent and solid. I hope that when our papers come out, people will feel the same. You just have to look at the different trials. You need people like Dr. Stergiou to wade through the trials to help you with that.

Ms. Ward: Thank you very much for joining me today and discussing this trial.

Scott R. Garrison, MD, PhD, is Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and Staff Physician, Department of Family Medicine, Kaye Edmonton Clinic, and he has disclosed receiving research grants from Alberta Innovates (the Alberta Provincial Government) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (the Canadian Federal Government).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: I’m joined today by Dr. Scott R. Garrison, MD, PhD. He is a professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and director of the Pragmatic Trials Collaborative.

You presented two studies at ESC. One is the BedMed study, comparing day vs nighttime dosing of blood pressure therapy. Can you tell us the top-line findings?

BedMed and BedMed-Frail

Dr. Garrison: We were looking to validate an earlier study that suggested a large benefit of taking blood pressure medication at bedtime, as far as reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs). That was the MAPEC study. They suggested a 60% reduction. The BedMed trial was in hypertensive primary care patients in five Canadian provinces. We randomized well over 3000 patients to bedtime or morning medications. We looked at MACEs — so all-cause death or hospitalizations for acute coronary syndrome, stroke, or heart failure, and a bunch of safety outcomes.

Essentially, . It was safe to take it at bedtime. But it did not convey any extra cardiovascular benefit.

Ms. Ward: And then you did a second study, called BedMed-Frail. Do you want to tell us the reason you did that?

Dr. Garrison: BedMed-Frail took place in a nursing home population. We believed that it was possible that frail, older adults might have very different risks and benefits, and that they would probably be underrepresented, as they normally are in the main trial.

We thought that because bedtime blood pressure medications would be theoretically preferentially lowering night pressure, which is already the lowest pressure of the day, that if you were at risk for hypotensive or ischemic adverse events, that might make it worse. We looked at falls and fractures; worsening cognition in case they had vascular dementia; and whether they developed decubitus ulcers (pressure sores) because you need a certain amount of pressure to get past any obstruction — in this case, it’s the weight of your body if you’re lying in bed all the time.

We also looked at problem behaviors. People who have dementia have what’s called “sundowning,” where agitation and confusion are worse as the evening is going on. We looked at that on the off chance that it had anything to do with blood pressures being lower. And the BedMed-Frail results mirror those of BedMed exactly. So there was no cardiovascular benefit, and in this population, that was largely driven by mortality; one third of these people died every year.

Ms. Ward: The median age was about 88?

Dr. Garrison: Yes, the median age was 88. There was no cardiovascular mortality advantage to bedtime dosing, but neither was there any signal of safety concerns.

Other Complementary and Conflicting Studies

Ms. Ward: These two studies mirror the TIME study from the United Kingdom.

Dr. Garrison: Yes. We found exactly what TIME found. Our point estimate was pretty much the same. The hazard ratio in the main trial was 0.96. Theirs, I believe, was 0.95. Our findings agree completely with those of TIME and differ substantially from the previous trials that suggested a large benefit.

Ms. Ward: Those previous trials were MAPEC and the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial.

Dr. Garrison: MAPEC was the first one. While we were doing our trial, and while the TIME investigators were doing their trial, both of us trying to validate MAPEC, the same group published another study called Hygia, which also reported a large reduction: a 45% reduction in MACE with bedtime dosing.

Ms. Ward: You didn’t present it, but there was also a meta-analysis presented here by somebody independent.

Dr. Garrison: Yes, Ricky Turgeon. I know Ricky. We gave him patient-level data for his meta-analysis, but I was not otherwise involved.

Ms. Ward: And the conclusion is the same.

Dr. Garrison: It’s the same. He only found the same five trials: MAPEC, Hygia, TIME, BedMed, and BedMed-Frail. Combining them all together, the CIs still span 1.0, so it didn’t end up being significant. But he also analyzed TIME and the BedMed trials separately — again suggesting that those trials showed no benefit.

Ms. Ward: There was a TIME substudy of night owls vs early risers or morning people, and there was a hint (or whatever you should say for a subanalysis of a neutral trial) that timing might make a difference there.

Dr. Garrison: They recently published, I guess it is a substudy, where they looked at people’s chronotype according to whether you consider yourself an early bird or a night owl. Their assessment was more detailed. They reported that if people were tending toward being early birds and they took their blood pressure medicine in the morning, or if they were night owls and they took it in the evening, that they tended to have statistically significantly better outcomes than the opposite timing. In that analysis, they were only looking at nonfatal myocardial infarction and nonfatal stroke.

We did ask something that was related. We asked people: “Do we consider yourself more of an early bird or a night owl?” So we do have those data. For what I presented at ESC, we just looked at the primary outcome; we did subgroups according to early bird, night owl, and neither, and that was not statistically significant. It didn’t rule it out. There were some trends in the direction that the TIME group were suggesting. We do intend to do a closer look at that.

But, you know, they call these “late-breaking trials,” and it really was in our case. We didn’t get the last of our data from the last province until the end of June, so we still are finishing up the analysis of the chronotype portion — so more to come in another month or so.

Do What You Like, or Stick to Morning Dosing?

Ms. Ward: For the purposes of people’s take-home message, does this mostly apply to once-daily–dosed antihypertensives?

Dr. Garrison: It was essentially once-daily medicines that were changed. The docs did have the opportunity to consolidate twice-daily meds into once-daily or switch to a different medication. That’s probably the area where adherence was the biggest issue, because it’s largely beta-blockers that were given twice daily at baseline, and they were less likely to want to change.

At 6 months, 83% of once-daily medications were taken per allocation in the bedtime group and 95% per allocation in the morning group, which was actually pretty good. For angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium-channel blockers, the adherence was excellent. Again, it was beta-blockers taken twice a day where it fell down, and then also diuretics. But if you combine all diuretic medications (ie, pure diuretics and combo agents), still, 75% of them were successful at taking them at bedtime. Only 15% of people switching a diuretic to bedtime dosing actually had problems with nocturia. Most physicians think that they can’t get their patients to take those meds at bedtime, but you can. There’s probably no reason to take it at bedtime, but most people do tolerate it.

Ms. Ward: Is your advice to take it whenever you feel like? I know when TIME came out, Professor George Stergiou, who’s the incoming president of the International Society of Hypertension, said, well, maybe we should stick with the morning, because that’s what most of the trials did.

Dr. Garrison: I think that›s a perfectly valid point of view, and maybe for a lot of people, that could be the default. There are some people, though, who will have a particular reason why one time is better. For instance, most people have no problems with calcium-channel blockers, but some get ankle swelling and you’re more likely to have that happen if you take them in the morning. Or lots of people want to take all their pills at the same time; blood pressure pills are easy ones to switch the timing of if you’re trying to accomplish that, and if that will help adherence. Basically, whatever time of day you can remember to take it the best is probably the right time.

Ms. Ward: Given where we are today, with your trials and TIME, do you think this is now settled science that it doesn’t make a difference?

Dr. Garrison: I’m probably the wrong person to ask, because I clearly have a bias. I think the methods in the TIME trial are really transparent and solid. I hope that when our papers come out, people will feel the same. You just have to look at the different trials. You need people like Dr. Stergiou to wade through the trials to help you with that.

Ms. Ward: Thank you very much for joining me today and discussing this trial.

Scott R. Garrison, MD, PhD, is Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and Staff Physician, Department of Family Medicine, Kaye Edmonton Clinic, and he has disclosed receiving research grants from Alberta Innovates (the Alberta Provincial Government) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (the Canadian Federal Government).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: I’m joined today by Dr. Scott R. Garrison, MD, PhD. He is a professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and director of the Pragmatic Trials Collaborative.

You presented two studies at ESC. One is the BedMed study, comparing day vs nighttime dosing of blood pressure therapy. Can you tell us the top-line findings?

BedMed and BedMed-Frail

Dr. Garrison: We were looking to validate an earlier study that suggested a large benefit of taking blood pressure medication at bedtime, as far as reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs). That was the MAPEC study. They suggested a 60% reduction. The BedMed trial was in hypertensive primary care patients in five Canadian provinces. We randomized well over 3000 patients to bedtime or morning medications. We looked at MACEs — so all-cause death or hospitalizations for acute coronary syndrome, stroke, or heart failure, and a bunch of safety outcomes.

Essentially, . It was safe to take it at bedtime. But it did not convey any extra cardiovascular benefit.

Ms. Ward: And then you did a second study, called BedMed-Frail. Do you want to tell us the reason you did that?

Dr. Garrison: BedMed-Frail took place in a nursing home population. We believed that it was possible that frail, older adults might have very different risks and benefits, and that they would probably be underrepresented, as they normally are in the main trial.

We thought that because bedtime blood pressure medications would be theoretically preferentially lowering night pressure, which is already the lowest pressure of the day, that if you were at risk for hypotensive or ischemic adverse events, that might make it worse. We looked at falls and fractures; worsening cognition in case they had vascular dementia; and whether they developed decubitus ulcers (pressure sores) because you need a certain amount of pressure to get past any obstruction — in this case, it’s the weight of your body if you’re lying in bed all the time.

We also looked at problem behaviors. People who have dementia have what’s called “sundowning,” where agitation and confusion are worse as the evening is going on. We looked at that on the off chance that it had anything to do with blood pressures being lower. And the BedMed-Frail results mirror those of BedMed exactly. So there was no cardiovascular benefit, and in this population, that was largely driven by mortality; one third of these people died every year.

Ms. Ward: The median age was about 88?

Dr. Garrison: Yes, the median age was 88. There was no cardiovascular mortality advantage to bedtime dosing, but neither was there any signal of safety concerns.

Other Complementary and Conflicting Studies

Ms. Ward: These two studies mirror the TIME study from the United Kingdom.

Dr. Garrison: Yes. We found exactly what TIME found. Our point estimate was pretty much the same. The hazard ratio in the main trial was 0.96. Theirs, I believe, was 0.95. Our findings agree completely with those of TIME and differ substantially from the previous trials that suggested a large benefit.

Ms. Ward: Those previous trials were MAPEC and the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial.

Dr. Garrison: MAPEC was the first one. While we were doing our trial, and while the TIME investigators were doing their trial, both of us trying to validate MAPEC, the same group published another study called Hygia, which also reported a large reduction: a 45% reduction in MACE with bedtime dosing.

Ms. Ward: You didn’t present it, but there was also a meta-analysis presented here by somebody independent.

Dr. Garrison: Yes, Ricky Turgeon. I know Ricky. We gave him patient-level data for his meta-analysis, but I was not otherwise involved.

Ms. Ward: And the conclusion is the same.

Dr. Garrison: It’s the same. He only found the same five trials: MAPEC, Hygia, TIME, BedMed, and BedMed-Frail. Combining them all together, the CIs still span 1.0, so it didn’t end up being significant. But he also analyzed TIME and the BedMed trials separately — again suggesting that those trials showed no benefit.

Ms. Ward: There was a TIME substudy of night owls vs early risers or morning people, and there was a hint (or whatever you should say for a subanalysis of a neutral trial) that timing might make a difference there.

Dr. Garrison: They recently published, I guess it is a substudy, where they looked at people’s chronotype according to whether you consider yourself an early bird or a night owl. Their assessment was more detailed. They reported that if people were tending toward being early birds and they took their blood pressure medicine in the morning, or if they were night owls and they took it in the evening, that they tended to have statistically significantly better outcomes than the opposite timing. In that analysis, they were only looking at nonfatal myocardial infarction and nonfatal stroke.

We did ask something that was related. We asked people: “Do we consider yourself more of an early bird or a night owl?” So we do have those data. For what I presented at ESC, we just looked at the primary outcome; we did subgroups according to early bird, night owl, and neither, and that was not statistically significant. It didn’t rule it out. There were some trends in the direction that the TIME group were suggesting. We do intend to do a closer look at that.

But, you know, they call these “late-breaking trials,” and it really was in our case. We didn’t get the last of our data from the last province until the end of June, so we still are finishing up the analysis of the chronotype portion — so more to come in another month or so.

Do What You Like, or Stick to Morning Dosing?

Ms. Ward: For the purposes of people’s take-home message, does this mostly apply to once-daily–dosed antihypertensives?

Dr. Garrison: It was essentially once-daily medicines that were changed. The docs did have the opportunity to consolidate twice-daily meds into once-daily or switch to a different medication. That’s probably the area where adherence was the biggest issue, because it’s largely beta-blockers that were given twice daily at baseline, and they were less likely to want to change.

At 6 months, 83% of once-daily medications were taken per allocation in the bedtime group and 95% per allocation in the morning group, which was actually pretty good. For angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium-channel blockers, the adherence was excellent. Again, it was beta-blockers taken twice a day where it fell down, and then also diuretics. But if you combine all diuretic medications (ie, pure diuretics and combo agents), still, 75% of them were successful at taking them at bedtime. Only 15% of people switching a diuretic to bedtime dosing actually had problems with nocturia. Most physicians think that they can’t get their patients to take those meds at bedtime, but you can. There’s probably no reason to take it at bedtime, but most people do tolerate it.

Ms. Ward: Is your advice to take it whenever you feel like? I know when TIME came out, Professor George Stergiou, who’s the incoming president of the International Society of Hypertension, said, well, maybe we should stick with the morning, because that’s what most of the trials did.

Dr. Garrison: I think that›s a perfectly valid point of view, and maybe for a lot of people, that could be the default. There are some people, though, who will have a particular reason why one time is better. For instance, most people have no problems with calcium-channel blockers, but some get ankle swelling and you’re more likely to have that happen if you take them in the morning. Or lots of people want to take all their pills at the same time; blood pressure pills are easy ones to switch the timing of if you’re trying to accomplish that, and if that will help adherence. Basically, whatever time of day you can remember to take it the best is probably the right time.

Ms. Ward: Given where we are today, with your trials and TIME, do you think this is now settled science that it doesn’t make a difference?

Dr. Garrison: I’m probably the wrong person to ask, because I clearly have a bias. I think the methods in the TIME trial are really transparent and solid. I hope that when our papers come out, people will feel the same. You just have to look at the different trials. You need people like Dr. Stergiou to wade through the trials to help you with that.

Ms. Ward: Thank you very much for joining me today and discussing this trial.

Scott R. Garrison, MD, PhD, is Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and Staff Physician, Department of Family Medicine, Kaye Edmonton Clinic, and he has disclosed receiving research grants from Alberta Innovates (the Alberta Provincial Government) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (the Canadian Federal Government).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC 2024

Calcium and CV Risk: Are Supplements and Vitamin D to Blame?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: Hi. I’m Tricia Ward, from theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. I’m joined today by Dr Matthew Budoff. He is professor of medicine at UCLA and the endowed chair of preventive cardiology at the Lundquist Institute. Welcome, Dr Budoff.

Matthew J. Budoff, MD: Thank you.

Dietary Calcium vs Coronary Calcium

Ms. Ward: The reason I wanted to talk to you today is because there have been some recent studies linking calcium supplements to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. I’m old enough to remember when we used to tell people that dietary calcium and coronary calcium weren’t connected and weren’t the same. Were we wrong?

Dr. Budoff: I think there’s a large amount of mixed data out there still. The US Preventive Services Task Force looked into this a number of years ago and said there’s no association between calcium supplementation and increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

As you mentioned, there are a couple of newer studies that point us toward a relationship. I think that we still have a little bit of a mixed bag, but we need to dive a little deeper into that to figure out what’s going on.

Ms. Ward: Does it appear to be connected to calcium in the form of supplements vs calcium from foods?

Dr. Budoff: We looked very carefully at dietary calcium in the MESA study, the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. There is no relationship between dietary calcium intake and coronary calcium or cardiovascular events. We’re talking mostly about supplements now when we talk about this increased risk that we’re seeing.

Does Vitamin D Exacerbate Risk?

Ms. Ward: Because it’s seen with supplements, is that likely because that’s a much higher concentration of calcium coming in or do you think it’s something inherent in its being in the form of a supplement?

Dr. Budoff: I think there are two things. One, it’s definitely a higher concentration all at once. You get many more milligrams at a time when you take a supplement than if you had a high-calcium food or drink.

Also, most supplements have vitamin D as well. I think vitamin D and calcium work synergistically. When you give them both together simultaneously, I think that may have more of a potentiating effect that might exacerbate any potential risk.

Ms. Ward: Is there any reason to think there might be a difference in type of calcium supplement? I always think of the chalky tablet form vs calcium chews.

Dr. Budoff: I’m not aware of a difference in the supplement type. I think the vitamin D issue is a big problem because we all have patients who take thousands of units of vitamin D — just crazy numbers. People advocate really high numbers and that stays in the system.

Personally, I think part of the explanation is that with very high levels of vitamin D on top of calcium supplementation, you now absorb it better. You now get it into the bone, but maybe also into the coronary arteries. If you’re very high in vitamin D and then are taking a large calcium supplement, it might be the calcium/vitamin D combination that’s giving us some trouble. I think people on vitamin D supplements really need to watch their levels and not get supratherapeutic.

Ms. Ward: With the vitamin D?

Dr. Budoff: With the vitamin D.

Diabetes and Renal Function

Ms. Ward: In some of the studies, there seems to be a higher risk in patients with diabetes. Is there any reason why that would be?

Dr. Budoff: I can’t think of a reason exactly why with diabetes per se, except for renal disease. Patients with diabetes have more intrinsic renal disease, proteinuria, and even a reduced eGFR. We’ve seen that the kidney is very strongly tied to this. We have a very strong relationship, in work I’ve done a decade ago now, showing that calcium supplementation (in the form of phosphate binders) in patients on dialysis or with advanced renal disease is linked to much higher coronary calcium progression.

We did prospective, randomized trials showing that calcium intake as binders to reduce phosphorus led to more coronary calcium. We always thought that was just relegated to the renal population, and there might be an overlap here with the diabetes and more renal disease. I have a feeling that it has to do with more of that. It might be regulation of parathyroid hormone as well, which might be more abnormal in patients with diabetes.

Avoid Supratherapeutic Vitamin D Levels

Ms. Ward:: What are you telling your patients?

Dr. Budoff: I tell patients with normal kidney function that the bone will modulate 99.9% of the calcium uptake. If they have osteopenia or osteoporosis, regardless of their calcium score, I’m very comfortable putting them on supplements.

I’m a little more cautious with the vitamin D levels, and I keep an eye on that and regulate how much vitamin D they get based on their levels. I get them into the normal range, but I don’t want them supratherapeutic. You can even follow their calcium score. Again, we’ve shown that if you’re taking too much calcium, your calcium score will go up. I can just check it again in a couple of years to make sure that it’s safe.

Ms. Ward:: In terms of vitamin D levels, when you’re saying “supratherapeutic,” what levels do you consider a safe amount to take?

Dr. Budoff: I’d like them under 100 ng/mL as far as their upper level. Normal is around 70 ng/mL at most labs. I try to keep them in the normal range. I don’t even want them to be high-normal if I’m going to be concomitantly giving them calcium supplements. Of course, if they have renal insufficiency, then I’m much more cautious. We’ve even seen calcium supplements raise the serum calcium, which you never see with dietary calcium. That’s another potential proof that it might be too much too fast.

For renal patients, even in mild renal insufficiency, maybe even in diabetes where we’ve seen a signal, maybe aim lower in the amount of calcium supplementation if diet is insufficient, and aim a little lower in vitamin D targets, and I think you’ll be in a safer place.

Ms. Ward: Is there anything else you want to add?

Dr. Budoff: The evidence is still evolving. I’d say that it’s interesting and maybe a little frustrating that we don’t have a final answer on all of this. I would stay tuned for more data because we’re looking at many of the epidemiologic studies to try to see what happens in the real world, with both dietary intake of calcium and calcium supplementation.

Ms. Ward: Thank you very much for joining me today.

Dr. Budoff: It’s a pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Dr. Budoff disclosed being a speaker for Amarin Pharma.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: Hi. I’m Tricia Ward, from theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. I’m joined today by Dr Matthew Budoff. He is professor of medicine at UCLA and the endowed chair of preventive cardiology at the Lundquist Institute. Welcome, Dr Budoff.

Matthew J. Budoff, MD: Thank you.

Dietary Calcium vs Coronary Calcium

Ms. Ward: The reason I wanted to talk to you today is because there have been some recent studies linking calcium supplements to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. I’m old enough to remember when we used to tell people that dietary calcium and coronary calcium weren’t connected and weren’t the same. Were we wrong?

Dr. Budoff: I think there’s a large amount of mixed data out there still. The US Preventive Services Task Force looked into this a number of years ago and said there’s no association between calcium supplementation and increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

As you mentioned, there are a couple of newer studies that point us toward a relationship. I think that we still have a little bit of a mixed bag, but we need to dive a little deeper into that to figure out what’s going on.

Ms. Ward: Does it appear to be connected to calcium in the form of supplements vs calcium from foods?

Dr. Budoff: We looked very carefully at dietary calcium in the MESA study, the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. There is no relationship between dietary calcium intake and coronary calcium or cardiovascular events. We’re talking mostly about supplements now when we talk about this increased risk that we’re seeing.

Does Vitamin D Exacerbate Risk?

Ms. Ward: Because it’s seen with supplements, is that likely because that’s a much higher concentration of calcium coming in or do you think it’s something inherent in its being in the form of a supplement?

Dr. Budoff: I think there are two things. One, it’s definitely a higher concentration all at once. You get many more milligrams at a time when you take a supplement than if you had a high-calcium food or drink.

Also, most supplements have vitamin D as well. I think vitamin D and calcium work synergistically. When you give them both together simultaneously, I think that may have more of a potentiating effect that might exacerbate any potential risk.

Ms. Ward: Is there any reason to think there might be a difference in type of calcium supplement? I always think of the chalky tablet form vs calcium chews.

Dr. Budoff: I’m not aware of a difference in the supplement type. I think the vitamin D issue is a big problem because we all have patients who take thousands of units of vitamin D — just crazy numbers. People advocate really high numbers and that stays in the system.

Personally, I think part of the explanation is that with very high levels of vitamin D on top of calcium supplementation, you now absorb it better. You now get it into the bone, but maybe also into the coronary arteries. If you’re very high in vitamin D and then are taking a large calcium supplement, it might be the calcium/vitamin D combination that’s giving us some trouble. I think people on vitamin D supplements really need to watch their levels and not get supratherapeutic.

Ms. Ward: With the vitamin D?

Dr. Budoff: With the vitamin D.

Diabetes and Renal Function

Ms. Ward: In some of the studies, there seems to be a higher risk in patients with diabetes. Is there any reason why that would be?

Dr. Budoff: I can’t think of a reason exactly why with diabetes per se, except for renal disease. Patients with diabetes have more intrinsic renal disease, proteinuria, and even a reduced eGFR. We’ve seen that the kidney is very strongly tied to this. We have a very strong relationship, in work I’ve done a decade ago now, showing that calcium supplementation (in the form of phosphate binders) in patients on dialysis or with advanced renal disease is linked to much higher coronary calcium progression.

We did prospective, randomized trials showing that calcium intake as binders to reduce phosphorus led to more coronary calcium. We always thought that was just relegated to the renal population, and there might be an overlap here with the diabetes and more renal disease. I have a feeling that it has to do with more of that. It might be regulation of parathyroid hormone as well, which might be more abnormal in patients with diabetes.

Avoid Supratherapeutic Vitamin D Levels

Ms. Ward:: What are you telling your patients?

Dr. Budoff: I tell patients with normal kidney function that the bone will modulate 99.9% of the calcium uptake. If they have osteopenia or osteoporosis, regardless of their calcium score, I’m very comfortable putting them on supplements.

I’m a little more cautious with the vitamin D levels, and I keep an eye on that and regulate how much vitamin D they get based on their levels. I get them into the normal range, but I don’t want them supratherapeutic. You can even follow their calcium score. Again, we’ve shown that if you’re taking too much calcium, your calcium score will go up. I can just check it again in a couple of years to make sure that it’s safe.

Ms. Ward:: In terms of vitamin D levels, when you’re saying “supratherapeutic,” what levels do you consider a safe amount to take?

Dr. Budoff: I’d like them under 100 ng/mL as far as their upper level. Normal is around 70 ng/mL at most labs. I try to keep them in the normal range. I don’t even want them to be high-normal if I’m going to be concomitantly giving them calcium supplements. Of course, if they have renal insufficiency, then I’m much more cautious. We’ve even seen calcium supplements raise the serum calcium, which you never see with dietary calcium. That’s another potential proof that it might be too much too fast.

For renal patients, even in mild renal insufficiency, maybe even in diabetes where we’ve seen a signal, maybe aim lower in the amount of calcium supplementation if diet is insufficient, and aim a little lower in vitamin D targets, and I think you’ll be in a safer place.

Ms. Ward: Is there anything else you want to add?

Dr. Budoff: The evidence is still evolving. I’d say that it’s interesting and maybe a little frustrating that we don’t have a final answer on all of this. I would stay tuned for more data because we’re looking at many of the epidemiologic studies to try to see what happens in the real world, with both dietary intake of calcium and calcium supplementation.

Ms. Ward: Thank you very much for joining me today.

Dr. Budoff: It’s a pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Dr. Budoff disclosed being a speaker for Amarin Pharma.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tricia Ward: Hi. I’m Tricia Ward, from theheart.org/Medscape Cardiology. I’m joined today by Dr Matthew Budoff. He is professor of medicine at UCLA and the endowed chair of preventive cardiology at the Lundquist Institute. Welcome, Dr Budoff.

Matthew J. Budoff, MD: Thank you.

Dietary Calcium vs Coronary Calcium

Ms. Ward: The reason I wanted to talk to you today is because there have been some recent studies linking calcium supplements to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. I’m old enough to remember when we used to tell people that dietary calcium and coronary calcium weren’t connected and weren’t the same. Were we wrong?

Dr. Budoff: I think there’s a large amount of mixed data out there still. The US Preventive Services Task Force looked into this a number of years ago and said there’s no association between calcium supplementation and increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

As you mentioned, there are a couple of newer studies that point us toward a relationship. I think that we still have a little bit of a mixed bag, but we need to dive a little deeper into that to figure out what’s going on.

Ms. Ward: Does it appear to be connected to calcium in the form of supplements vs calcium from foods?

Dr. Budoff: We looked very carefully at dietary calcium in the MESA study, the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. There is no relationship between dietary calcium intake and coronary calcium or cardiovascular events. We’re talking mostly about supplements now when we talk about this increased risk that we’re seeing.

Does Vitamin D Exacerbate Risk?

Ms. Ward: Because it’s seen with supplements, is that likely because that’s a much higher concentration of calcium coming in or do you think it’s something inherent in its being in the form of a supplement?

Dr. Budoff: I think there are two things. One, it’s definitely a higher concentration all at once. You get many more milligrams at a time when you take a supplement than if you had a high-calcium food or drink.

Also, most supplements have vitamin D as well. I think vitamin D and calcium work synergistically. When you give them both together simultaneously, I think that may have more of a potentiating effect that might exacerbate any potential risk.

Ms. Ward: Is there any reason to think there might be a difference in type of calcium supplement? I always think of the chalky tablet form vs calcium chews.

Dr. Budoff: I’m not aware of a difference in the supplement type. I think the vitamin D issue is a big problem because we all have patients who take thousands of units of vitamin D — just crazy numbers. People advocate really high numbers and that stays in the system.

Personally, I think part of the explanation is that with very high levels of vitamin D on top of calcium supplementation, you now absorb it better. You now get it into the bone, but maybe also into the coronary arteries. If you’re very high in vitamin D and then are taking a large calcium supplement, it might be the calcium/vitamin D combination that’s giving us some trouble. I think people on vitamin D supplements really need to watch their levels and not get supratherapeutic.

Ms. Ward: With the vitamin D?

Dr. Budoff: With the vitamin D.

Diabetes and Renal Function

Ms. Ward: In some of the studies, there seems to be a higher risk in patients with diabetes. Is there any reason why that would be?

Dr. Budoff: I can’t think of a reason exactly why with diabetes per se, except for renal disease. Patients with diabetes have more intrinsic renal disease, proteinuria, and even a reduced eGFR. We’ve seen that the kidney is very strongly tied to this. We have a very strong relationship, in work I’ve done a decade ago now, showing that calcium supplementation (in the form of phosphate binders) in patients on dialysis or with advanced renal disease is linked to much higher coronary calcium progression.

We did prospective, randomized trials showing that calcium intake as binders to reduce phosphorus led to more coronary calcium. We always thought that was just relegated to the renal population, and there might be an overlap here with the diabetes and more renal disease. I have a feeling that it has to do with more of that. It might be regulation of parathyroid hormone as well, which might be more abnormal in patients with diabetes.

Avoid Supratherapeutic Vitamin D Levels

Ms. Ward:: What are you telling your patients?

Dr. Budoff: I tell patients with normal kidney function that the bone will modulate 99.9% of the calcium uptake. If they have osteopenia or osteoporosis, regardless of their calcium score, I’m very comfortable putting them on supplements.

I’m a little more cautious with the vitamin D levels, and I keep an eye on that and regulate how much vitamin D they get based on their levels. I get them into the normal range, but I don’t want them supratherapeutic. You can even follow their calcium score. Again, we’ve shown that if you’re taking too much calcium, your calcium score will go up. I can just check it again in a couple of years to make sure that it’s safe.

Ms. Ward:: In terms of vitamin D levels, when you’re saying “supratherapeutic,” what levels do you consider a safe amount to take?

Dr. Budoff: I’d like them under 100 ng/mL as far as their upper level. Normal is around 70 ng/mL at most labs. I try to keep them in the normal range. I don’t even want them to be high-normal if I’m going to be concomitantly giving them calcium supplements. Of course, if they have renal insufficiency, then I’m much more cautious. We’ve even seen calcium supplements raise the serum calcium, which you never see with dietary calcium. That’s another potential proof that it might be too much too fast.

For renal patients, even in mild renal insufficiency, maybe even in diabetes where we’ve seen a signal, maybe aim lower in the amount of calcium supplementation if diet is insufficient, and aim a little lower in vitamin D targets, and I think you’ll be in a safer place.

Ms. Ward: Is there anything else you want to add?

Dr. Budoff: The evidence is still evolving. I’d say that it’s interesting and maybe a little frustrating that we don’t have a final answer on all of this. I would stay tuned for more data because we’re looking at many of the epidemiologic studies to try to see what happens in the real world, with both dietary intake of calcium and calcium supplementation.

Ms. Ward: Thank you very much for joining me today.

Dr. Budoff: It’s a pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Dr. Budoff disclosed being a speaker for Amarin Pharma.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Doc releases song after racist massacre in Buffalo

Physician-musician Cleveland Francis, MD, responded to the recent mass shooting in Buffalo, New York, which left 10 dead, in the only way he knew how. He wrote and recorded a song to honor the victims as “a plea to the other side to recognize us as people,” the Black cardiologist told this news organization.

He couldn’t sleep after the shooting, and “this song was just in my head.” In the 1990s, Dr. Francis took a 3-year sabbatical from medicine to perform and tour as a country singer. He leveraged his Nashville connections to get “Buffalo” produced and recorded.

Acclaimed artist James Threalkill created the accompanying art, titled “The Heavenly Escort of the Buffalo 10,” after listening to a scratch demo.

Dr. Francis doesn’t want people to overlook the massacre as just another gun violence incident because this was “overt hate-crime racism,” he said.

According to the affidavit submitted by FBI agent Christopher J. Dlugokinski, the suspect’s “motive for the mass shooting was to prevent Black people from replacing White people and eliminating the White race, and to inspire others to commit similar attacks.”

Dr. Francis views the Buffalo shooting as distinct from cases like the murder of George Floyd that involved crime or police. It immediately made him think of the Mother Emanuel Church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina. “Having a black skin is now a death warrant,” he said.

The song is also an appeal for White people to fight racism. Dr. Francis is concerned about young men caught up in white supremacy and suggests that we be more alert to children or grandchildren who disconnect from their families, spend time on the dark web, and access guns. The lyrics deliberately don’t mention guns because Dr. Francis wanted to stay out of that debate. “I just sang: ‘What else do I have to do to prove to you that I’m human too?’ ”

Despite his country credentials, Dr. Francis wrote “Buffalo” as a Gospel song because that genre “connects with Black people more and because that civil rights movement was through the church with Dr. Martin Luther King,” he explained. Although he sings all styles of music, the song is performed by Nashville-based singer Michael Lusk so that it’s not a “Cleve Francis thing,” he said, referring to his stage name.

Songwriter Norman Kerner collaborated on the song. The music was produced and recorded by David Thein and mixed by Bob Bullock of Nashville, who Dr. Francis had worked with when he was an artist on Capitol Records.

They sent the video and artwork to the Mayor of Buffalo, Byron Brown, but have yet to hear back. Dr. Francis hopes it could be part of their healing, noting that some people used the song in their Juneteenth celebrations.

The Louisiana native grew up during segregation and was one of two Black students in the Medical College of Virginia class of 1973. After completing his cardiology fellowship, no one would hire him, so Dr. Francis set up his own practice in Northern Virginia. He now works at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute in Alexandria, Va. He remains optimistic about race relations in America and would love a Black pop or Gospel star to record “Buffalo” and bring it to a wider audience.

Dr. Francis is a regular blogger for Medscape. His contribution to country music is recognized in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. You can find more of his music on YouTube.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physician-musician Cleveland Francis, MD, responded to the recent mass shooting in Buffalo, New York, which left 10 dead, in the only way he knew how. He wrote and recorded a song to honor the victims as “a plea to the other side to recognize us as people,” the Black cardiologist told this news organization.

He couldn’t sleep after the shooting, and “this song was just in my head.” In the 1990s, Dr. Francis took a 3-year sabbatical from medicine to perform and tour as a country singer. He leveraged his Nashville connections to get “Buffalo” produced and recorded.

Acclaimed artist James Threalkill created the accompanying art, titled “The Heavenly Escort of the Buffalo 10,” after listening to a scratch demo.

Dr. Francis doesn’t want people to overlook the massacre as just another gun violence incident because this was “overt hate-crime racism,” he said.

According to the affidavit submitted by FBI agent Christopher J. Dlugokinski, the suspect’s “motive for the mass shooting was to prevent Black people from replacing White people and eliminating the White race, and to inspire others to commit similar attacks.”

Dr. Francis views the Buffalo shooting as distinct from cases like the murder of George Floyd that involved crime or police. It immediately made him think of the Mother Emanuel Church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina. “Having a black skin is now a death warrant,” he said.

The song is also an appeal for White people to fight racism. Dr. Francis is concerned about young men caught up in white supremacy and suggests that we be more alert to children or grandchildren who disconnect from their families, spend time on the dark web, and access guns. The lyrics deliberately don’t mention guns because Dr. Francis wanted to stay out of that debate. “I just sang: ‘What else do I have to do to prove to you that I’m human too?’ ”

Despite his country credentials, Dr. Francis wrote “Buffalo” as a Gospel song because that genre “connects with Black people more and because that civil rights movement was through the church with Dr. Martin Luther King,” he explained. Although he sings all styles of music, the song is performed by Nashville-based singer Michael Lusk so that it’s not a “Cleve Francis thing,” he said, referring to his stage name.

Songwriter Norman Kerner collaborated on the song. The music was produced and recorded by David Thein and mixed by Bob Bullock of Nashville, who Dr. Francis had worked with when he was an artist on Capitol Records.

They sent the video and artwork to the Mayor of Buffalo, Byron Brown, but have yet to hear back. Dr. Francis hopes it could be part of their healing, noting that some people used the song in their Juneteenth celebrations.

The Louisiana native grew up during segregation and was one of two Black students in the Medical College of Virginia class of 1973. After completing his cardiology fellowship, no one would hire him, so Dr. Francis set up his own practice in Northern Virginia. He now works at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute in Alexandria, Va. He remains optimistic about race relations in America and would love a Black pop or Gospel star to record “Buffalo” and bring it to a wider audience.

Dr. Francis is a regular blogger for Medscape. His contribution to country music is recognized in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. You can find more of his music on YouTube.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physician-musician Cleveland Francis, MD, responded to the recent mass shooting in Buffalo, New York, which left 10 dead, in the only way he knew how. He wrote and recorded a song to honor the victims as “a plea to the other side to recognize us as people,” the Black cardiologist told this news organization.

He couldn’t sleep after the shooting, and “this song was just in my head.” In the 1990s, Dr. Francis took a 3-year sabbatical from medicine to perform and tour as a country singer. He leveraged his Nashville connections to get “Buffalo” produced and recorded.

Acclaimed artist James Threalkill created the accompanying art, titled “The Heavenly Escort of the Buffalo 10,” after listening to a scratch demo.

Dr. Francis doesn’t want people to overlook the massacre as just another gun violence incident because this was “overt hate-crime racism,” he said.

According to the affidavit submitted by FBI agent Christopher J. Dlugokinski, the suspect’s “motive for the mass shooting was to prevent Black people from replacing White people and eliminating the White race, and to inspire others to commit similar attacks.”

Dr. Francis views the Buffalo shooting as distinct from cases like the murder of George Floyd that involved crime or police. It immediately made him think of the Mother Emanuel Church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina. “Having a black skin is now a death warrant,” he said.

The song is also an appeal for White people to fight racism. Dr. Francis is concerned about young men caught up in white supremacy and suggests that we be more alert to children or grandchildren who disconnect from their families, spend time on the dark web, and access guns. The lyrics deliberately don’t mention guns because Dr. Francis wanted to stay out of that debate. “I just sang: ‘What else do I have to do to prove to you that I’m human too?’ ”

Despite his country credentials, Dr. Francis wrote “Buffalo” as a Gospel song because that genre “connects with Black people more and because that civil rights movement was through the church with Dr. Martin Luther King,” he explained. Although he sings all styles of music, the song is performed by Nashville-based singer Michael Lusk so that it’s not a “Cleve Francis thing,” he said, referring to his stage name.

Songwriter Norman Kerner collaborated on the song. The music was produced and recorded by David Thein and mixed by Bob Bullock of Nashville, who Dr. Francis had worked with when he was an artist on Capitol Records.

They sent the video and artwork to the Mayor of Buffalo, Byron Brown, but have yet to hear back. Dr. Francis hopes it could be part of their healing, noting that some people used the song in their Juneteenth celebrations.

The Louisiana native grew up during segregation and was one of two Black students in the Medical College of Virginia class of 1973. After completing his cardiology fellowship, no one would hire him, so Dr. Francis set up his own practice in Northern Virginia. He now works at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute in Alexandria, Va. He remains optimistic about race relations in America and would love a Black pop or Gospel star to record “Buffalo” and bring it to a wider audience.

Dr. Francis is a regular blogger for Medscape. His contribution to country music is recognized in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. You can find more of his music on YouTube.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Trans women in female sports: A sports scientist’s take

An interview with Ross Tucker, PhD

When Lia Thomas won the women’s 500-yard freestyle at the 2022 NCAA Division 1 swimming championships, the issue of trans women’s participation in female sports ignited national headlines.

which prohibit trans women’s participation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start with the proinclusion argument that there are always advantages in sports.

That’s true. The whole point of sports is to recognize people who have advantages and reward them for it. By the time this argument comes out, people have already accepted that males have advantages, right?

Some do, some don’t.

If someone uses this argument to say that we should allow trans women, basically biological males, to compete in women’s sports, they’ve implicitly accepted that there are advantages. Otherwise, what advantage are you talking about?

They would say it’s like the advantage Michael Phelps has because of his wingspan.

To answer that, you have to start by asking why women’s sports exist.

Women’s sports exist because we recognize that male physiology has biological differences that create performance advantages. Women’s sports exist to ensure that male advantages are excluded. If you allow male advantage in, you’re allowing something to cross into a category that specifically tries to exclude it. That makes the advantage possessed by trans women conceptually and substantively different from an advantage that’s possessed by Michael Phelps because his advantage doesn’t cross a category boundary line.

If someone wants to allow natural advantages to be celebrated in sports, they’re arguing against the existence of any categories, because every single category in sports is trying to filter out certain advantages.

Weight categories in boxing exist to get rid of the advantage of being stronger, taller, with greater reach. Paralympic categories filter out the natural advantage that someone has if, for example, they are only mildly affected by cerebral palsy, compared with more severely affected.

If someone wants to allow natural advantages, they’re making an argument for all advantages to be eliminated from regulation, and we would end up with sports dominated by males between the ages of 20 and 28.

There are some people suggesting open categories by height and weight.

The problem is that for any height, males will be stronger, faster, more powerful than females. For any mass, and we know this because weightlifting has categories by mass, males lift about 30% heavier than females. They’ll be about 10%-15% faster at the same height and weight.

There’d be one or two sports where you might have some women, like gymnastics. Otherwise you would have to create categories that are so small – say, under 100 pounds. But in every other category, most sports would be completely dominated by males.

It’s not a viable solution for me unless we as a society are satisfied with filtering out women.

Another argument is that if trans women have an advantage, then they would be dominating.

That one misunderstands how you assess advantage. For a trans woman to win, she still has to be good enough at the base level without the advantage, in order to parlay that advantage into winning the women’s events.

If I was in the Tour de France and you gave me a bicycle with a 100-watt motor, I wouldn’t win the Tour de France. I’d do better than I would have done without it, but I wouldn’t win. Does my failure to win prove that motors don’t give an advantage? Of course not. My failure says more about my base level of performance than it does about the motor.

In terms of trans athletes, the retention of biological attributes creates the retention of performance advantages, which means that the person’s ranking relative to their peers’ will go up when they compare themselves to women rather than men. Someone who’s ranked 500 might improve to the 250s, but you still won’t see them on a podium.

It’s the change in performance that matters, not the final outcome.

Wasn’t Lia Thomas ranked in the 500s in the men’s division?

There’s some dispute as to whether it was 460 or 550 in the 200- and 65th in the 500-yard freestyle. But the concept is the same and we can use that case because we know the percentage performance change.

As Will Thomas, the performance was 4:18 in the 500-yard freestyle. As Lia Thomas, it’s 4:33. Ms. Thomas has slowed by 5.8% as a result of testosterone suppression. That’s fairly typical; most studies so far suggest performance impairments in that range.

The thing is that the male-female gap in swimming times is 10%-12% on average. That means that Ms. Thomas has retained about half the male advantage.

In strength events, for instance, weightlifting, where the gap is 30% or more, if you lost 10%, you’d still retain a 20% advantage and you’d jump more ranking places.

The retention of about half the male advantage is enough for No. 1 in the NCAA, but it’s not enough to move Ms. Thomas to No. 1 in the world.

The record set by Katie Ledecky in the 500 freestyle is 4:24. Thomas swam 4:18 as a man so could only afford to lose about 1% to be the record holder in women’s swimming.

When Ms. Thomas was beaten by cisgender women in other events, your point is that’s just because her baseline (pretransition) time wasn’t good enough.

Exactly. Are your performances in men’s sports close enough to the best woman such that you can turn that retained advantage into dominance, winning in women’s sports?

If the answer to that is yes, then you get Thomas in the 500. If the answer to that is not quite, then you get Thomas in the other distances.

On your podcast, you expressed frustration at having to keep debunking these arguments. Why do you think they persist?

There are a few things in play. There are nuances around the idea of advantage that people from outside sports don’t always appreciate.

But then the second thing comes into play and that’s the fact that this is an emotive issue. If you come to this debate wanting trans inclusion, then you reject the idea that it’s unfair. You will dismiss everything I’ve just said.

There’s a third thing. When people invoke the Phelps wingspan argument, they haven’t thought through the implications. If you could sit them down and say: “Okay. If you want to get rid of regulating natural advantages, then we would get rid of male and female categories,” what do you think would happen then?

They may still support inclusion because that’s their world view, but at least they’re honest now and understand the implications. But most people don’t go through that process.

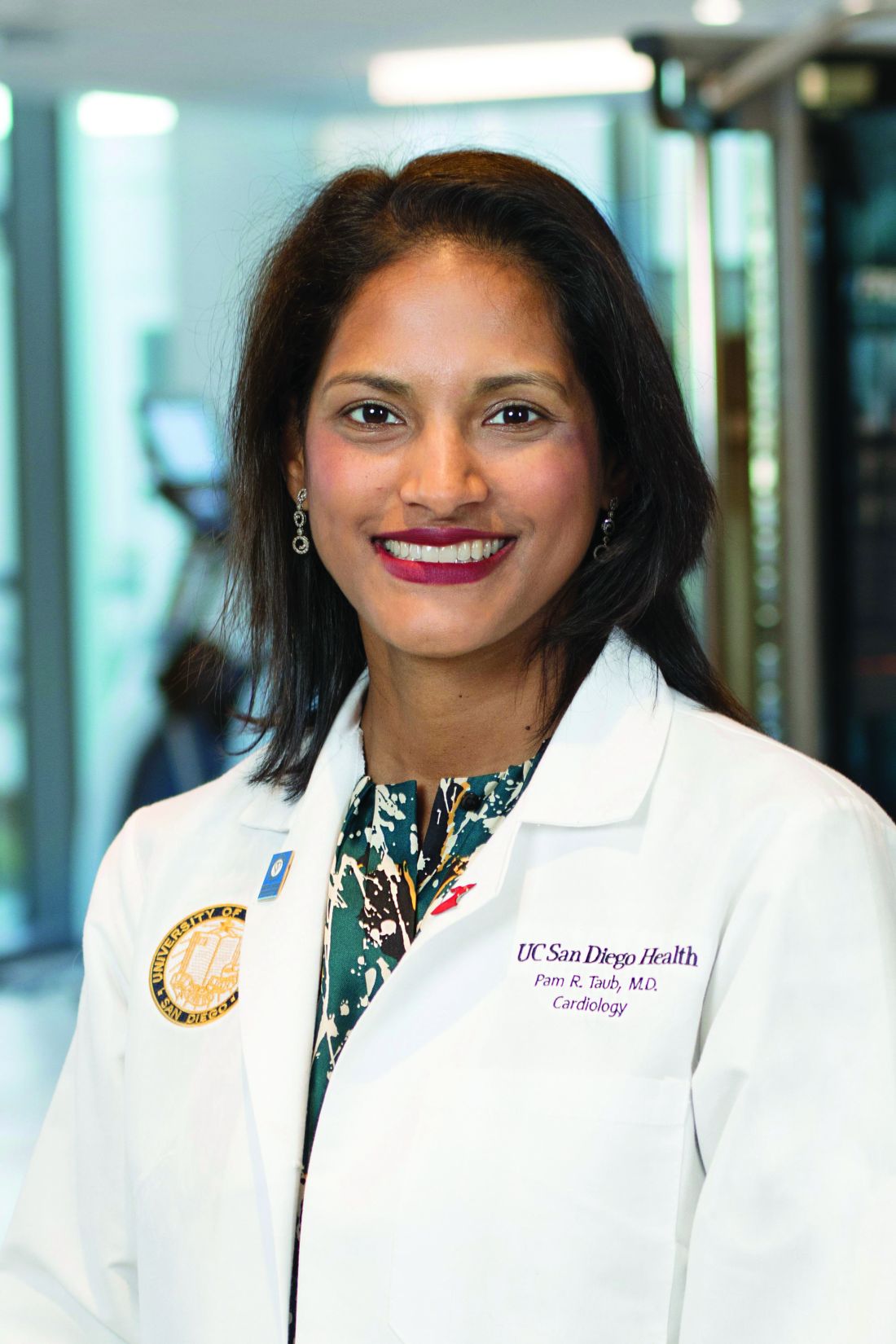

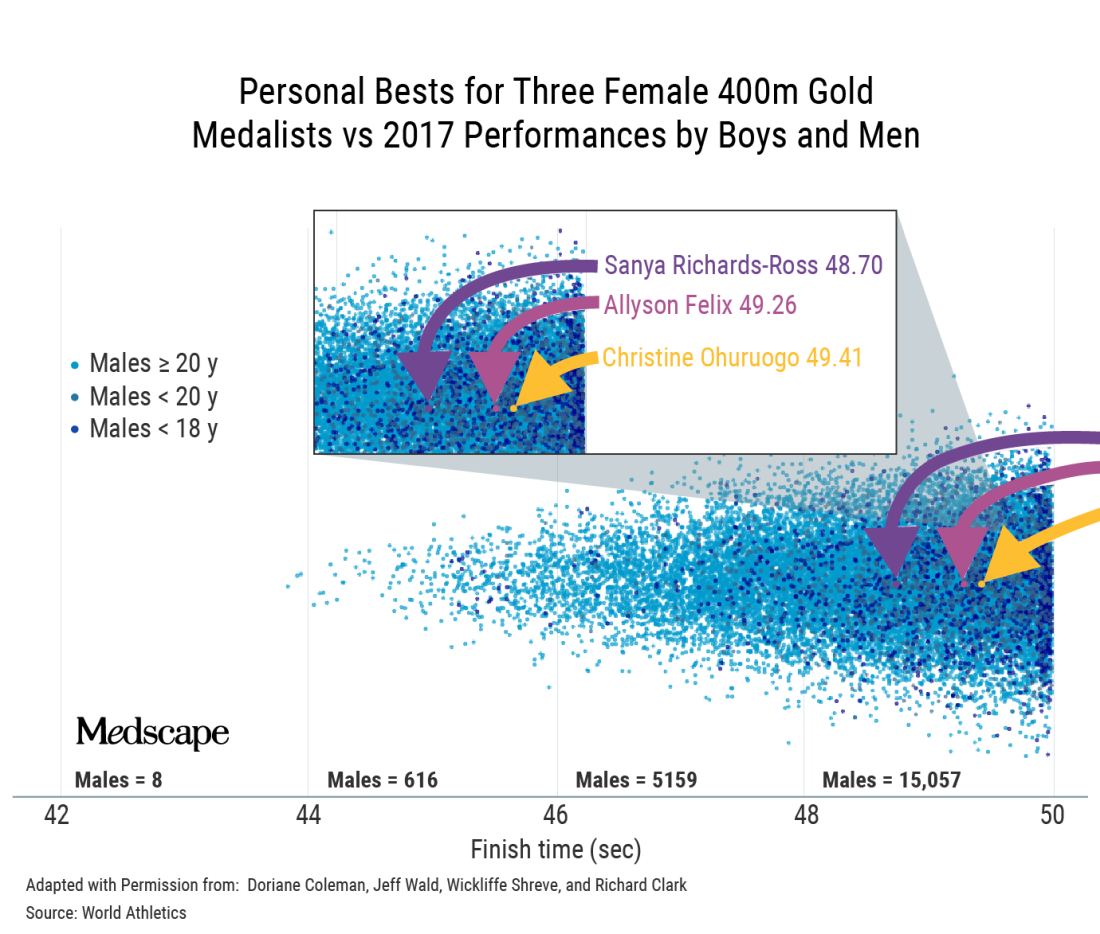

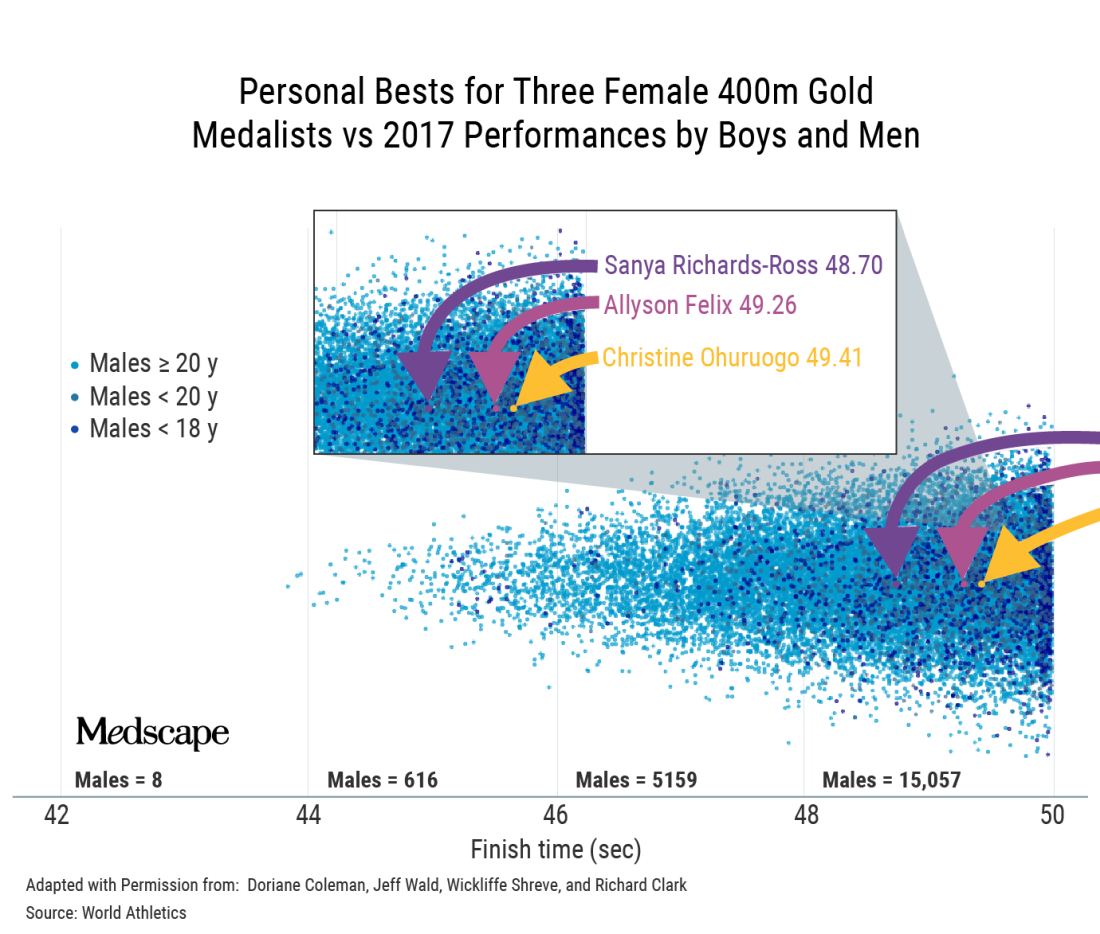

I get that men are faster but I was shocked at how many are faster than elite women – for example, Allyson Felix.

There’s an amazing visual representation of that.

That’s a classic example where, if you’re immersed in sports, it becomes intuitive. If you’re not, you do a double-take and think, is that right? Position determines perspective.

Do you think some of it is because we’re constantly told that girls and women can do anything?

It’s a paradox that is difficult for people to get their minds around because in most walks of life, we can say that women can do anything. Of course, it’s arguably more difficult for women to become CEOs of Fortune 500 companies. This is a work in progress.

But sports are different. In sports, it’s not possible to directly compare male and female, and then tell girls they can be the best at whatever in the whole human race. That’s the uniqueness of sports and the reason categories exist in the first place. The biology does matter.

Speaking of biology, you’ve said that the focus on testosterone levels is a bit of a red herring.

Yes. The authorities were looking for a solution.

They grabbed onto the idea that lowering testosterone was the solution and perpetuated that as the mechanism by which we would ensure fairness. The problem is that my concentration of testosterone today is only a tiny part of the story.

I’ve been exposed to testosterone my whole life. My twin sister has not. There are many differences between us, but in terms of sports, the main biological difference is not that my testosterone is higher today; it’s that my testosterone has been higher my whole life. It’s the work done by that hormone over many years that makes a difference.

The key issue is, has this body, this physiology, been exposed to and benefited in the sports context, from male hormones – yes or no?

If your answer is yes, then that body belongs in male sports. With gender identity, we want to accommodate as far as possible, but we can’t take away that difference. That’s where we create this collision of rights between trans women and women.

Ultimately, your point is that we can’t have both fairness and inclusion.

When we sat down to do the World Rugby trans guidance, we had an epiphany: It doesn’t matter which way we go; we’re going to face hostility.

Once you accept that there are two parties that are affected and one of them will always be unhappy, then you start to see that fairness and inclusion can’t be balanced.

What about Joanna Harper’s proposal to make rules case by case and sport by sport?

First, it could be tricky legally because you’re effectively discriminating against some people within a subset of a subset. You’re going to end up saying to some trans women: “You can play because you don’t pose a safety or fairness issue.” But to another: “You can’t because you’re too strong.”

Then the problem is, how do you do that screening? It’s not like you can measure half a dozen variables and then have an algorithm spit out a performance level that tells you that this trans woman can compete here safely and fairly. It’s a theoretical solution that is practically impossible.

At a conference in Boston recently, Joanna said that when there are no medals, prize money, scholarships, or record times, we should allow inclusion. But just because a woman isn’t winning medals or going to the Olympics doesn’t mean there’s not considerable value for her if she were to make her school team, for instance.

There are only 11 places on the soccer field, eight lanes in a swimming pool. The moment you allow someone in, you potentially exclude someone else. And that happens everywhere, not only at the elite level.

Would you ever make a distinction between elite and subelite?

One of the beauties of sports is that it’s a meritocracy; it functions on a pathway system. I don’t think the level matters if you can track that this person’s presence denied a place on the team or a place at the competition to someone else.

With Lia Thomas, it’s not only denying the silver medalist gold or fourth place a bronze; it’s also the fact that there are only so many places at that meet. For some, that was their ambition and they weren’t able to realize it.

Now, a lot of sports are played outside that pathway. Say your local tennis club has a social league. There is little there to stand in the way of inclusion. Although I’m mindful that there may be a women’s league where it does matter to them.

We can try to accommodate trans women when the stakes are not high, provided that two requirements are met: One is that there’s no disruption to the selection/meritocracy pathway; and the second key point is that women must be okay with that inclusion, particularly if there are safety considerations, but even if it’s just a fairness consideration.

That’s where it gets tricky, because there are bigoted people in the world. Unfortunately, sometimes it’s difficult to tell whether people are using scientific arguments to prop up bigotry or whether they are genuine.

Joanna Harper has said that if you support inclusion, you have to be okay with trans women winning.

Winning the summer tennis league is not winning in the same sense as winning at the NCAA.

But the moment winning means selection and performance pathways, then I think we have to draw a line. The moment participation disrupts the natural order in sports, then it’s a problem.

In World Rugby, we proposed open competitions lower in contact to deal with the safety concerns. That was rejected by the trans community because they felt it was othering – that we were trying to squeeze them off to the side.

If you offered me one of two choices: no participation, or inclusion and they have to be able to win, I’d go for the former.

How did you get involved in this topic?

I got involved because I testified in the Caster Semenya case at the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

That is not a transgender issue; it’s a difference of sex development issue. What it has in common is the question of what to do with male-bodied biological advantage in sports.

When World Rugby joined the Olympic Games, we followed the IOC transgender policy. In 2019, it became apparent from the latest research that male advantage isn’t removed by testosterone suppression. We decided to delete the previous policy and make a new one.

The latest IOC policy is kind of no policy; it leaves it up to the governing bodies for each sport.

The one element of progress in what the IOC released, and it really is the only one, is that they’ve recognized that sports have to manage three imperatives: fairness, inclusion, and safety.

The 2015 IOC document says something like “sports should strive to be as inclusive as possible, but the overriding objective remains to guarantee a fair competition.” Basically, fair competition was nonnegotiable and must be guaranteed.

Of course, that policy allowed for testosterone suppression, and you’d have a difficult time convincing a physiologist that lowering testosterone guarantees fair competition.

Where there is merit in the current policy is that it’s clear that sports like rugby, boxing, taekwondo, and judo have a different equation with respect to safety, fairness, and inclusion than sports like equestrian, shooting, and archery. I think that’s wise to acknowledge.

However, the IOC policy doesn’t do anything to lead. In fact, what they said was extraordinary: There should be no presumption of advantage. If there’s no presumption of advantage for male-bodied athletes, then why do they persist with two categories? If there’s no presumption of advantage for trans women, are they saying that gender identity removes the advantage? We know that’s not true. We know that at the very least, you should presume that there is some advantage. How you manage it is up to you, but you can’t say that it’s not there.

This is a hostile debate. Have you ever thought: Maybe I’ll just shut up and stick to other sports topics?

Big time. The Lia Thomas case brought out a lot of vitriol. From about 2017, the situation we had with Ms. Thomas was predictable. The problem is that 95% of the world didn’t know this was happening and were taken by surprise.

The number of people who have opinions has exploded. A lot wade in without much thought. I’ve seen people question Lia Thomas’s motives. Presumably, Lia Thomas is trans, identifies as a woman, and therefore thinks she belongs in women’s sports. But I’ve seen people saying she only wants to swim in women’s sports because she knows she’ll win. And that’s not the worst of it. I’ve seen people saying Lia Thomas is only identifying as a woman so she can get into women’s changing rooms.

I don’t see how that helps the conversation. It just polarizes to the point that neither side is listening to the other. Before it was the trans community that wasn’t interested in talking about the idea of advantage, fairness, and safety. Their position is that trans women are women; how do you even have a discussion when they’ve got that dogma as their foundation?

Now, unfortunately, on the other side, we’re seeing unnecessary offensive tactics. For example, I’ve referred to Lia Thomas as “she.” I’ll have people shouting at me for using “she.” You’ve got to pick your battles, and that’s not the one you want to be fighting, in my opinion.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An interview with Ross Tucker, PhD

An interview with Ross Tucker, PhD

When Lia Thomas won the women’s 500-yard freestyle at the 2022 NCAA Division 1 swimming championships, the issue of trans women’s participation in female sports ignited national headlines.

which prohibit trans women’s participation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start with the proinclusion argument that there are always advantages in sports.

That’s true. The whole point of sports is to recognize people who have advantages and reward them for it. By the time this argument comes out, people have already accepted that males have advantages, right?

Some do, some don’t.

If someone uses this argument to say that we should allow trans women, basically biological males, to compete in women’s sports, they’ve implicitly accepted that there are advantages. Otherwise, what advantage are you talking about?

They would say it’s like the advantage Michael Phelps has because of his wingspan.

To answer that, you have to start by asking why women’s sports exist.

Women’s sports exist because we recognize that male physiology has biological differences that create performance advantages. Women’s sports exist to ensure that male advantages are excluded. If you allow male advantage in, you’re allowing something to cross into a category that specifically tries to exclude it. That makes the advantage possessed by trans women conceptually and substantively different from an advantage that’s possessed by Michael Phelps because his advantage doesn’t cross a category boundary line.

If someone wants to allow natural advantages to be celebrated in sports, they’re arguing against the existence of any categories, because every single category in sports is trying to filter out certain advantages.

Weight categories in boxing exist to get rid of the advantage of being stronger, taller, with greater reach. Paralympic categories filter out the natural advantage that someone has if, for example, they are only mildly affected by cerebral palsy, compared with more severely affected.

If someone wants to allow natural advantages, they’re making an argument for all advantages to be eliminated from regulation, and we would end up with sports dominated by males between the ages of 20 and 28.

There are some people suggesting open categories by height and weight.

The problem is that for any height, males will be stronger, faster, more powerful than females. For any mass, and we know this because weightlifting has categories by mass, males lift about 30% heavier than females. They’ll be about 10%-15% faster at the same height and weight.

There’d be one or two sports where you might have some women, like gymnastics. Otherwise you would have to create categories that are so small – say, under 100 pounds. But in every other category, most sports would be completely dominated by males.

It’s not a viable solution for me unless we as a society are satisfied with filtering out women.

Another argument is that if trans women have an advantage, then they would be dominating.

That one misunderstands how you assess advantage. For a trans woman to win, she still has to be good enough at the base level without the advantage, in order to parlay that advantage into winning the women’s events.

If I was in the Tour de France and you gave me a bicycle with a 100-watt motor, I wouldn’t win the Tour de France. I’d do better than I would have done without it, but I wouldn’t win. Does my failure to win prove that motors don’t give an advantage? Of course not. My failure says more about my base level of performance than it does about the motor.

In terms of trans athletes, the retention of biological attributes creates the retention of performance advantages, which means that the person’s ranking relative to their peers’ will go up when they compare themselves to women rather than men. Someone who’s ranked 500 might improve to the 250s, but you still won’t see them on a podium.

It’s the change in performance that matters, not the final outcome.

Wasn’t Lia Thomas ranked in the 500s in the men’s division?