User login

Enlarging Breast Lesion

The Diagnosis: Radiation-Associated Angiosarcoma

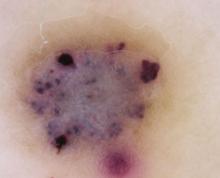

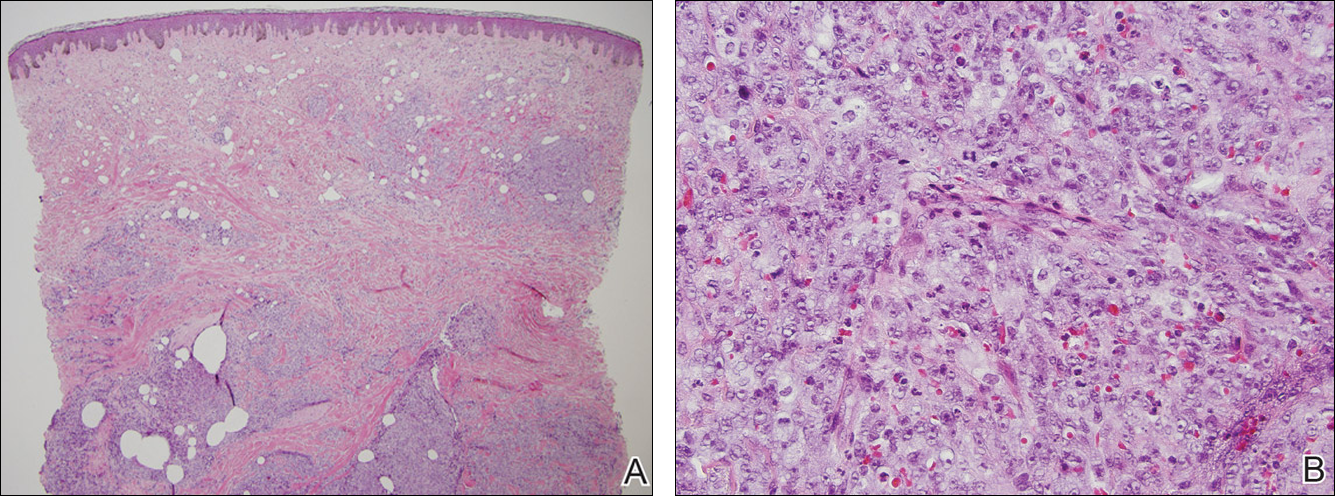

At the time of presentation, a 4-mm lesional punch biopsy was obtained (Figure), which revealed an epithelioid neoplasm within the dermis expressing CD31 and CD34, and staining negatively for S-100, CD45, and estrogen and progesterone receptors. The histologic and immunophenotypic findings were compatible with the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Given the patient’s history of radiation for breast carcinoma several years ago, this tumor was consistent with radiation-associated angiosarcoma (RAAS).

Development of secondary angiosarcoma has been linked to both prior radiation (RAAS) and chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome).1 Radiation-associated angiosarcoma is defined as a “pathologically confirmed breast or chest wall angiosarcoma arising within a previously irradiated field.”2 The incidence of RAAS is estimated to be 0.9 per 1000 individuals following radiation treatment of breast cancer over the subsequent 15 years and a mean time from radiation to development of 7 years.1 Incidence is expected to increase in the future due to improved likelihood of surviving early-stage breast carcinoma and the increased use of external beam radiation therapy for management of breast cancer.

Differentiating between primary and secondary angiosarcoma of the breast is important. Although primary breast angiosarcoma usually arises in women aged 30 to 40 years, RAAS tends to arise in older women (mean age, 68 years) and is seen only in those women with prior radiation.2 Additionally, high-level amplification of MYC, a known photo-oncogene, on chromosome 8 is a key genetic alteration of RAAS that helps to distinguish it from primary angiosarcoma, though this variance may be present in only half of RAAS cases.3 Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor cells for MYC expression correlates well with this amplification and also is helpful in distinguishing atypical vascular lesions from RAAS.4 Atypical vascular lesions, similar to RAAS, occur years after radiation exposure and may have a similar clinical presentation. Atypical vascular lesions do not progress to angiosarcoma in reported cases, but clinical and histologic overlap with RAAS make the diagnosis difficult.5 In these cases, analysis with fluorescence in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry for the MYC amplification is important to differentiate these tumors.6

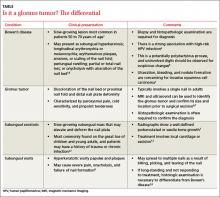

At the time of presentation, the majority of patients with RAAS of the breast have localized disease, often with a variable presentation. In all known cases, there have been skin changes present, emphasizing the importance of both patient and clinician vigilance on a regular basis in at-risk individuals. In one study, the most common presentation was breast ecchymosis, which was observed in 55% of patients.7 These lesions involve the dermis and are commonly mistaken for benign conditions such as infection or hemorrhage.2 In 2 other studies, RAAS most often manifested as a skin nodule or apparent tumor, closely followed by either a rash or bruiselike presentation.1,2

The overall recommendation for management of patients with ecchymotic skin lesions in previously irradiated regions is to obtain a biopsy specimen for tissue diagnosis. Although there is no standard of care for the management of RAAS, a multidisciplinary approach involving specialists from oncology, surgical oncology, and radiation oncology is recommended. Most often, radical surgery encompassing both the breast parenchyma and the at-risk radiated skin is performed. Extensive surgery has demonstrated the best survival benefits compared to mastectomy alone.7 Chemotherapeutics also may be used as adjuncts to surgery, which have been determined to decrease local recurrence rates but have no proven survival benefits.2 Adverse prognostic factors for survival are tumor size greater than 10 cm and development of local and/or distant metastases.2 Following the diagnosis of RAAS, our patient underwent radical mastectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy and remained disease free 6 months after surgery.

In summary, RAAS is a well-known, albeit relatively uncommon, consequence of radiation therapy. Dermatologists, oncologists, and primary care providers play an important role in recognizing this entity when evaluating patients with ecchymotic lesions as well as nodules or tumors within an irradiated field. Biopsy should be obtained promptly to prevent delay in diagnosis and to expedite referral to appropriate specialists for further evaluation and treatment.

- Seinen JM, Emelie S, Verstappen V, et al. Radiation-associated angiosarcoma after breast cancer: high recurrence rate and poor survival despite surgical treatment with R0 resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2700-2706.

- Torres KE, Ravi V, Kin K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with radiation-associated angiosarcomas of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1267-1274.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Ginter PS, Mosquera JM, MacDonald TY, et al. Diagnostic utility of MYC amplification and anti-MYC immunohistochemistry in atypical vascular lesions, primary or radiation-induced mammary angiosarcomas, and primary angiosarcomas of other sites. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:709-716.

- Mentzel T, Schildhaus HU, Palmedo G, et al. Postradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma after treatment of breast carcinoma is characterized by MYC amplification in contrast to atypical vascular lesions after radiotherapy and control cases: clinicopathological immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 66 cases. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:75-85.

- Fernandez AP, Sun Y, Tubbs RR, et al. FISH for MYC amplification and anti-MYC immunohistochemistry: useful diagnostic tools in the assessment of secondary angiosarcoma and atypical vascular proliferations. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:234-242.

- Morgan EA, Kozono DE, Wang Q, et al. Cutaneous radiation-associated angiosarcoma of the breast: poor prognosis in a rare secondary malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3801-3808.

The Diagnosis: Radiation-Associated Angiosarcoma

At the time of presentation, a 4-mm lesional punch biopsy was obtained (Figure), which revealed an epithelioid neoplasm within the dermis expressing CD31 and CD34, and staining negatively for S-100, CD45, and estrogen and progesterone receptors. The histologic and immunophenotypic findings were compatible with the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Given the patient’s history of radiation for breast carcinoma several years ago, this tumor was consistent with radiation-associated angiosarcoma (RAAS).

Development of secondary angiosarcoma has been linked to both prior radiation (RAAS) and chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome).1 Radiation-associated angiosarcoma is defined as a “pathologically confirmed breast or chest wall angiosarcoma arising within a previously irradiated field.”2 The incidence of RAAS is estimated to be 0.9 per 1000 individuals following radiation treatment of breast cancer over the subsequent 15 years and a mean time from radiation to development of 7 years.1 Incidence is expected to increase in the future due to improved likelihood of surviving early-stage breast carcinoma and the increased use of external beam radiation therapy for management of breast cancer.

Differentiating between primary and secondary angiosarcoma of the breast is important. Although primary breast angiosarcoma usually arises in women aged 30 to 40 years, RAAS tends to arise in older women (mean age, 68 years) and is seen only in those women with prior radiation.2 Additionally, high-level amplification of MYC, a known photo-oncogene, on chromosome 8 is a key genetic alteration of RAAS that helps to distinguish it from primary angiosarcoma, though this variance may be present in only half of RAAS cases.3 Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor cells for MYC expression correlates well with this amplification and also is helpful in distinguishing atypical vascular lesions from RAAS.4 Atypical vascular lesions, similar to RAAS, occur years after radiation exposure and may have a similar clinical presentation. Atypical vascular lesions do not progress to angiosarcoma in reported cases, but clinical and histologic overlap with RAAS make the diagnosis difficult.5 In these cases, analysis with fluorescence in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry for the MYC amplification is important to differentiate these tumors.6

At the time of presentation, the majority of patients with RAAS of the breast have localized disease, often with a variable presentation. In all known cases, there have been skin changes present, emphasizing the importance of both patient and clinician vigilance on a regular basis in at-risk individuals. In one study, the most common presentation was breast ecchymosis, which was observed in 55% of patients.7 These lesions involve the dermis and are commonly mistaken for benign conditions such as infection or hemorrhage.2 In 2 other studies, RAAS most often manifested as a skin nodule or apparent tumor, closely followed by either a rash or bruiselike presentation.1,2

The overall recommendation for management of patients with ecchymotic skin lesions in previously irradiated regions is to obtain a biopsy specimen for tissue diagnosis. Although there is no standard of care for the management of RAAS, a multidisciplinary approach involving specialists from oncology, surgical oncology, and radiation oncology is recommended. Most often, radical surgery encompassing both the breast parenchyma and the at-risk radiated skin is performed. Extensive surgery has demonstrated the best survival benefits compared to mastectomy alone.7 Chemotherapeutics also may be used as adjuncts to surgery, which have been determined to decrease local recurrence rates but have no proven survival benefits.2 Adverse prognostic factors for survival are tumor size greater than 10 cm and development of local and/or distant metastases.2 Following the diagnosis of RAAS, our patient underwent radical mastectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy and remained disease free 6 months after surgery.

In summary, RAAS is a well-known, albeit relatively uncommon, consequence of radiation therapy. Dermatologists, oncologists, and primary care providers play an important role in recognizing this entity when evaluating patients with ecchymotic lesions as well as nodules or tumors within an irradiated field. Biopsy should be obtained promptly to prevent delay in diagnosis and to expedite referral to appropriate specialists for further evaluation and treatment.

The Diagnosis: Radiation-Associated Angiosarcoma

At the time of presentation, a 4-mm lesional punch biopsy was obtained (Figure), which revealed an epithelioid neoplasm within the dermis expressing CD31 and CD34, and staining negatively for S-100, CD45, and estrogen and progesterone receptors. The histologic and immunophenotypic findings were compatible with the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Given the patient’s history of radiation for breast carcinoma several years ago, this tumor was consistent with radiation-associated angiosarcoma (RAAS).

Development of secondary angiosarcoma has been linked to both prior radiation (RAAS) and chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome).1 Radiation-associated angiosarcoma is defined as a “pathologically confirmed breast or chest wall angiosarcoma arising within a previously irradiated field.”2 The incidence of RAAS is estimated to be 0.9 per 1000 individuals following radiation treatment of breast cancer over the subsequent 15 years and a mean time from radiation to development of 7 years.1 Incidence is expected to increase in the future due to improved likelihood of surviving early-stage breast carcinoma and the increased use of external beam radiation therapy for management of breast cancer.

Differentiating between primary and secondary angiosarcoma of the breast is important. Although primary breast angiosarcoma usually arises in women aged 30 to 40 years, RAAS tends to arise in older women (mean age, 68 years) and is seen only in those women with prior radiation.2 Additionally, high-level amplification of MYC, a known photo-oncogene, on chromosome 8 is a key genetic alteration of RAAS that helps to distinguish it from primary angiosarcoma, though this variance may be present in only half of RAAS cases.3 Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor cells for MYC expression correlates well with this amplification and also is helpful in distinguishing atypical vascular lesions from RAAS.4 Atypical vascular lesions, similar to RAAS, occur years after radiation exposure and may have a similar clinical presentation. Atypical vascular lesions do not progress to angiosarcoma in reported cases, but clinical and histologic overlap with RAAS make the diagnosis difficult.5 In these cases, analysis with fluorescence in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry for the MYC amplification is important to differentiate these tumors.6

At the time of presentation, the majority of patients with RAAS of the breast have localized disease, often with a variable presentation. In all known cases, there have been skin changes present, emphasizing the importance of both patient and clinician vigilance on a regular basis in at-risk individuals. In one study, the most common presentation was breast ecchymosis, which was observed in 55% of patients.7 These lesions involve the dermis and are commonly mistaken for benign conditions such as infection or hemorrhage.2 In 2 other studies, RAAS most often manifested as a skin nodule or apparent tumor, closely followed by either a rash or bruiselike presentation.1,2

The overall recommendation for management of patients with ecchymotic skin lesions in previously irradiated regions is to obtain a biopsy specimen for tissue diagnosis. Although there is no standard of care for the management of RAAS, a multidisciplinary approach involving specialists from oncology, surgical oncology, and radiation oncology is recommended. Most often, radical surgery encompassing both the breast parenchyma and the at-risk radiated skin is performed. Extensive surgery has demonstrated the best survival benefits compared to mastectomy alone.7 Chemotherapeutics also may be used as adjuncts to surgery, which have been determined to decrease local recurrence rates but have no proven survival benefits.2 Adverse prognostic factors for survival are tumor size greater than 10 cm and development of local and/or distant metastases.2 Following the diagnosis of RAAS, our patient underwent radical mastectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy and remained disease free 6 months after surgery.

In summary, RAAS is a well-known, albeit relatively uncommon, consequence of radiation therapy. Dermatologists, oncologists, and primary care providers play an important role in recognizing this entity when evaluating patients with ecchymotic lesions as well as nodules or tumors within an irradiated field. Biopsy should be obtained promptly to prevent delay in diagnosis and to expedite referral to appropriate specialists for further evaluation and treatment.

- Seinen JM, Emelie S, Verstappen V, et al. Radiation-associated angiosarcoma after breast cancer: high recurrence rate and poor survival despite surgical treatment with R0 resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2700-2706.

- Torres KE, Ravi V, Kin K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with radiation-associated angiosarcomas of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1267-1274.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Ginter PS, Mosquera JM, MacDonald TY, et al. Diagnostic utility of MYC amplification and anti-MYC immunohistochemistry in atypical vascular lesions, primary or radiation-induced mammary angiosarcomas, and primary angiosarcomas of other sites. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:709-716.

- Mentzel T, Schildhaus HU, Palmedo G, et al. Postradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma after treatment of breast carcinoma is characterized by MYC amplification in contrast to atypical vascular lesions after radiotherapy and control cases: clinicopathological immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 66 cases. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:75-85.

- Fernandez AP, Sun Y, Tubbs RR, et al. FISH for MYC amplification and anti-MYC immunohistochemistry: useful diagnostic tools in the assessment of secondary angiosarcoma and atypical vascular proliferations. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:234-242.

- Morgan EA, Kozono DE, Wang Q, et al. Cutaneous radiation-associated angiosarcoma of the breast: poor prognosis in a rare secondary malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3801-3808.

- Seinen JM, Emelie S, Verstappen V, et al. Radiation-associated angiosarcoma after breast cancer: high recurrence rate and poor survival despite surgical treatment with R0 resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2700-2706.

- Torres KE, Ravi V, Kin K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with radiation-associated angiosarcomas of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1267-1274.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Ginter PS, Mosquera JM, MacDonald TY, et al. Diagnostic utility of MYC amplification and anti-MYC immunohistochemistry in atypical vascular lesions, primary or radiation-induced mammary angiosarcomas, and primary angiosarcomas of other sites. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:709-716.

- Mentzel T, Schildhaus HU, Palmedo G, et al. Postradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma after treatment of breast carcinoma is characterized by MYC amplification in contrast to atypical vascular lesions after radiotherapy and control cases: clinicopathological immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 66 cases. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:75-85.

- Fernandez AP, Sun Y, Tubbs RR, et al. FISH for MYC amplification and anti-MYC immunohistochemistry: useful diagnostic tools in the assessment of secondary angiosarcoma and atypical vascular proliferations. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:234-242.

- Morgan EA, Kozono DE, Wang Q, et al. Cutaneous radiation-associated angiosarcoma of the breast: poor prognosis in a rare secondary malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3801-3808.

A 75-year-old woman with a history of stage II invasive ductal carcinoma of the right breast presented to the dermatology clinic with an enlarging, indurated, ecchymotic plaque on the inferior aspect of the right breast of 2 months’ duration. The patient underwent a lumpectomy, radiation, and adjuvant chemotherapy 13 years prior to presentation. Review of systems was otherwise noncontributory.

Painful Nail with Longitudinal Erythronychia

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

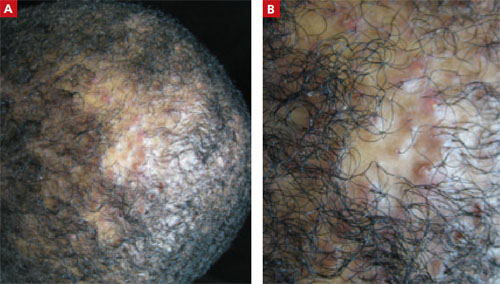

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

Patients report relief of symptoms following excision, although it may take several weeks for the pain to resolve completely.1 The rate of recurrence following excision is estimated at 10% to 20%.1 This may be due to incomplete excision or the development of a new lesion. Therefore, patients should be re-evaluated and considered for possible re-exploration if symptoms return or persist for more than 3 months after the excision.13

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

Patients report relief of symptoms following excision, although it may take several weeks for the pain to resolve completely.1 The rate of recurrence following excision is estimated at 10% to 20%.1 This may be due to incomplete excision or the development of a new lesion. Therefore, patients should be re-evaluated and considered for possible re-exploration if symptoms return or persist for more than 3 months after the excision.13

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

Patients report relief of symptoms following excision, although it may take several weeks for the pain to resolve completely.1 The rate of recurrence following excision is estimated at 10% to 20%.1 This may be due to incomplete excision or the development of a new lesion. Therefore, patients should be re-evaluated and considered for possible re-exploration if symptoms return or persist for more than 3 months after the excision.13

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

Painful nail with longitudinal erythronychia

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

Pruritic rash on trunk

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC MAN came into our dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of a pruritic rash that was confined mainly to the trunk. Prior to this visit, he had tried topical corticosteroids and antifungals, but they had not helped.

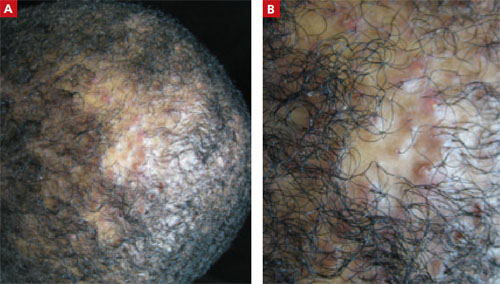

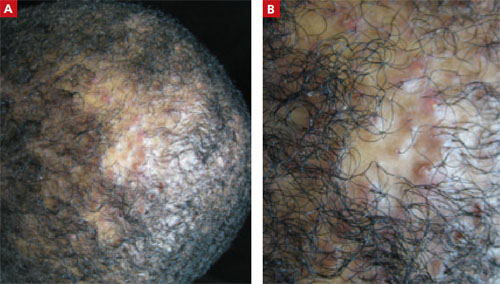

His trunk showed erythematous macules and reticulate patches with interspersed thin urticarial plaques without scale (FIGURE). Given that the patient had no vesicles or lichenification (which one would expect with eczematous dermatitis) and that the topical steroids did not provide any relief, we performed a biopsy.

FIGURE

Erythematous macules and reticulate patches without scale

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate. On higher magnification, the infiltrate proved to be predominately plasma cells. After further investigation and interview, the patient revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women; his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as “the great imitator.” Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. With the worldwide HIV epidemic, safe sex programs effectively dropped the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States to the lowest in recorded history in the year 2001 at 2.17/100,000.1

More recently, however, this infection appears to be making a comeback. Beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.1

Secondary syphilis usually appears 6 to 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. As the pathogen spreads into the bloodstream, a host of systemic symptoms may occur, including an influenza-like illness of body aches, fever, fatigue, and headache. While the exanthem of secondary syphilis is traditionally described as a nonpruritic, papular eruption involving the trunk, extremities, face, palms, and soles, a number of cutaneous manifestations are possible, including localized alopecia and syphilids.2 In addition, a number of atypical cases are described in the literature, although none has described an urticarial variant, as seen in our case.

The differential included urticaria and lupus erythematosus

The differential diagnosis for our patient included urticaria, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and mycosis fungoides. All of these conditions can be distinguished from secondary syphilis by serology and/or biopsy.

Urticaria is a common dermatologic problem with numerous etiologies. It presents as pruritic raised edematous erythematous wheels that blanch with pressure. Although it affects 15% to 25% of the general population at least once in their lives,3 it may progress to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Isolated acute urticaria usually responds to oral antihistamines.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis that appears as persistent macules that are red to brown and may exhibit telangiectasia.4 Systemic disease may be evaluated using serum tryptase levels. Patients without systemic disease are managed with oral antihistamines.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) often presents precipitously as erythematous maculopapular lesions that may coalesce into annular or papulosquamous plaques.5 It has a predilection for sun-exposed areas and is more common in women.5 Multiple drugs have been associated with SCLE, including phenytoin, calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.6 Treatment consists of discontinuing the offending drug (if one is identified), avoiding (or protecting against) sun exposure, and using topical corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials.

Mycosis fungoides is a form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that more commonly affects males.7 It begins as erythematous pruritic patches that typically involve the sun-spared areas of the lower abdomen and proximal extremities; it progresses slowly.7 As lesions develop into plaques, they may appear psoriasiform. Treatment depends on the stage of the disease and ranges from topical corticosteroids to systemic radiation and chemotherapy.8

Serology greatly aids diagnosis

If syphilis is not treated during the primary stage, it may progress directly into latency or into the second stage of infection. Preventing progression into late findings hinges upon proper diagnostics. While the initial suspicion should begin with history and physical examination, serology is most frequently used to confirm the presence of Treponema pallidum.

It may take as long as 3 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre for serology to become positive.9 During this interval, directly visualizing the pathogen via dark-field microscopy may be useful. Following this interval, nontreponemal serology such as the RPR and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) are frequently used as the initial serology. These rapid tests detect the antibody to cardiolipin and are relatively inexpensive.

Infection is confirmed with specific treponemal tests, including the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs), treponemal enzyme immunoassay, and treponemal particle agglutination tests. These tests are specific for T pallidum and confirm a positive RPR or VDRL. However, specific treponemal tests will not differentiate syphilis from nonvenereal treponematoses such as Bejel, Yaws, and Pinta.10

The common belief is that nontreponemal tests may become negative after successful treatment, and treponemal tests will remain positive indefinitely after successful treatment. However, a study found that 28% of patients treated during primary syphilis and 44% of patients treated during secondary syphilis had positive nontreponemal tests 3 years after treatment.11 In the same study, nearly a quarter of patients treated during primary syphilis no longer had positive FTA-abs 3 years after treatment.11

Penicillin remains the first-line treatment

Once the presence of T pallidum is confirmed, treatment depends on the stage of infection (TABLE). In nonallergic patients, benzathine penicillin G is the standard of care. It should be administered as a single intramuscular (IM) dose of 2.4 million units during primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis12 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Late latent and tertiary syphilis require 3 to 4 weeks of penicillin therapy that is usually achieved with 3 weekly IM injections of 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G12 (SOR: C). Owing largely to the selective permeability of the blood-brain barrier, neurosyphilis requires a larger dose of 3 million to 4 million units intravenous aqueous crystalline benzathine penicillin every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days12 (SOR: C).

Penicillin desensitization should be considered in penicillin-allergic patients, particularly in those who are pregnant or have HIV infection.12

Treatment success can be determined by a 4-fold decline in RPR/VDRL titer over a period of 3 to 6 months after treatment. During the first 24 hours after initial treatment, patients may develop an acute febrile illness known as the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This is largely the result of massive lysis of the pathogen, spilling large quantities of inflammatory cytokines into the bloodstream.13

Table

Syphilis treatment by stage of infection12

| Stage | Time since exposure | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | 10-90 days | Adults Children |

| Secondary | 4-10 weeks | Adults Children |

| Early latent | After primary or secondary stages, <1 year | Adults Children |

| Late latent | >1 year of no symptoms | Adults Children |

| Tertiary | Months to years | Adults See above |

| Neurosyphilis (at any stage) | Any time after infection | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18-24 million units/d, administered as 3-4 million units IV every 4 hours or continuous infusion, for 10-14 days Alternative |

| IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous. | ||

Our patient’s symptoms resolved with penicillin

Given the nebulous history of exposure, we treated the patient as having late latent syphilis (rather than secondary syphilis) and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Our case demonstrates a unique atypical presentation of secondary syphilis. To our knowledge, there is no mention of secondary syphilis mimicking urticaria in the literature. The pruritus that accompanied the lesions was also atypical; however, one study noted 42% of patients experience this symptom in secondary syphilis.14 Fortunately, serological studies confirmed the diagnosis and the patient’s symptoms resolved with standard therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter L. Mattei, MD, 641 Bainbridge Drive, Mullica Hill, NJ 08062; peterlmattei@gmail.com

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of notifiable diseases: United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;58:1-100.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. eds. Dermatology (e-dition). 2nd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008. Available at: http://www.expertconsultbook.com/expertconsult/op/book.do?method=display&type=bookPage&decorator=none&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-2999-1..50002-3&isbn=978-1-4160-2999-1. Accessed March 29, 2010.

3. Fonacier LS, Dreskin SC, Leung DY. Allergic skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 suppl 2):S138-S149.

4. Nguyen NQ. Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:1.-

5. Wechsler HL. Cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 1985;3:79-87.

6. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

7. Galper SL, Smith BD, Wilson LD. Diagnosis and management of mycosis fungoides. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24:491-501.

8. Lansigan F, Foss FM. Current and emerging treatment strategies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Drugs. 2010;70:273-286.

9. Eccleston K, Collins L, Higgins SP. Primary syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:145-151.

10. Koff AB, Rosen T. Nonvenereal treponematoses: yaws, endemic syphilis, and pinta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:519-535.

11. Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, et al. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:1005-1009.

12. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

13. Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2768–2784.

14. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC MAN came into our dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of a pruritic rash that was confined mainly to the trunk. Prior to this visit, he had tried topical corticosteroids and antifungals, but they had not helped.

His trunk showed erythematous macules and reticulate patches with interspersed thin urticarial plaques without scale (FIGURE). Given that the patient had no vesicles or lichenification (which one would expect with eczematous dermatitis) and that the topical steroids did not provide any relief, we performed a biopsy.

FIGURE

Erythematous macules and reticulate patches without scale

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate. On higher magnification, the infiltrate proved to be predominately plasma cells. After further investigation and interview, the patient revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women; his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as “the great imitator.” Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. With the worldwide HIV epidemic, safe sex programs effectively dropped the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States to the lowest in recorded history in the year 2001 at 2.17/100,000.1

More recently, however, this infection appears to be making a comeback. Beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.1