User login

Brachioradial Pruritus: An Etiologic Review and Treatment Summary

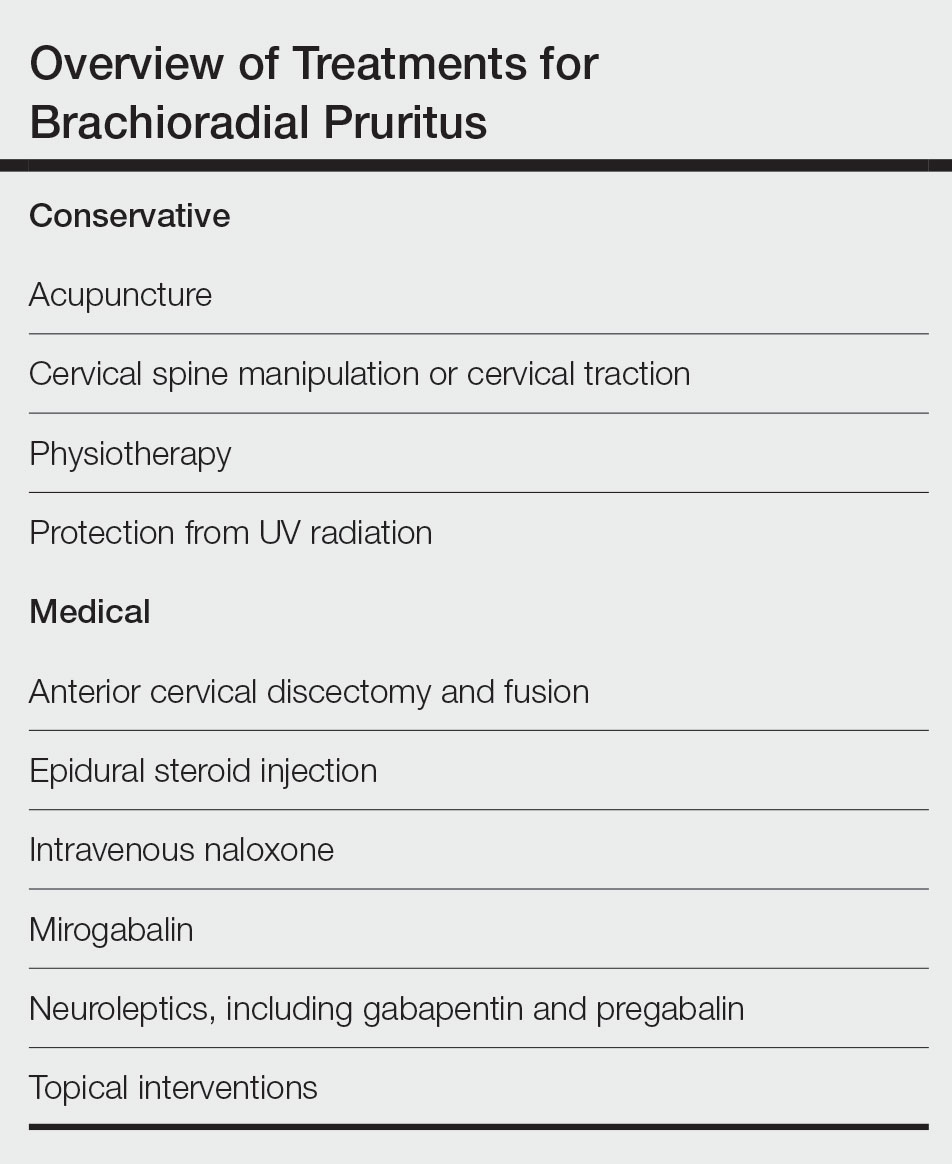

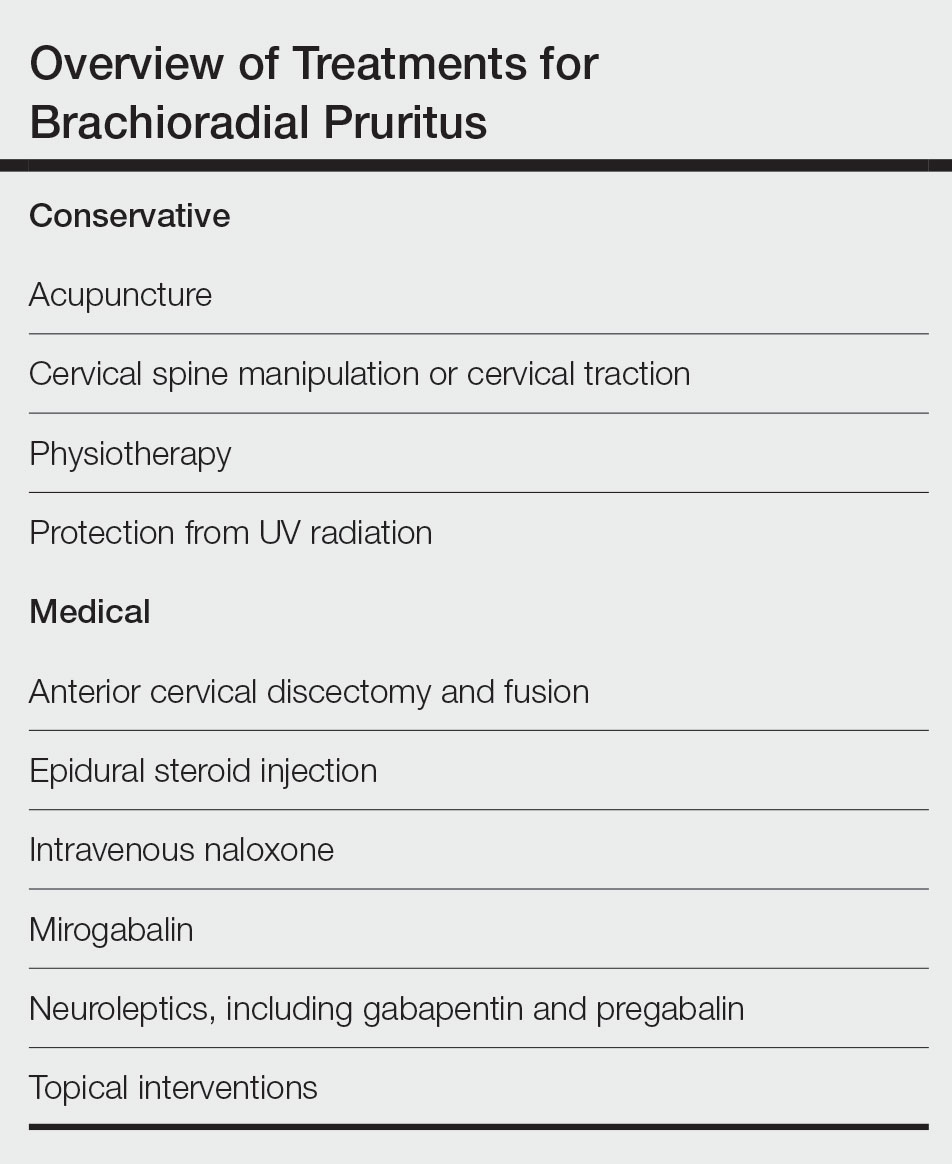

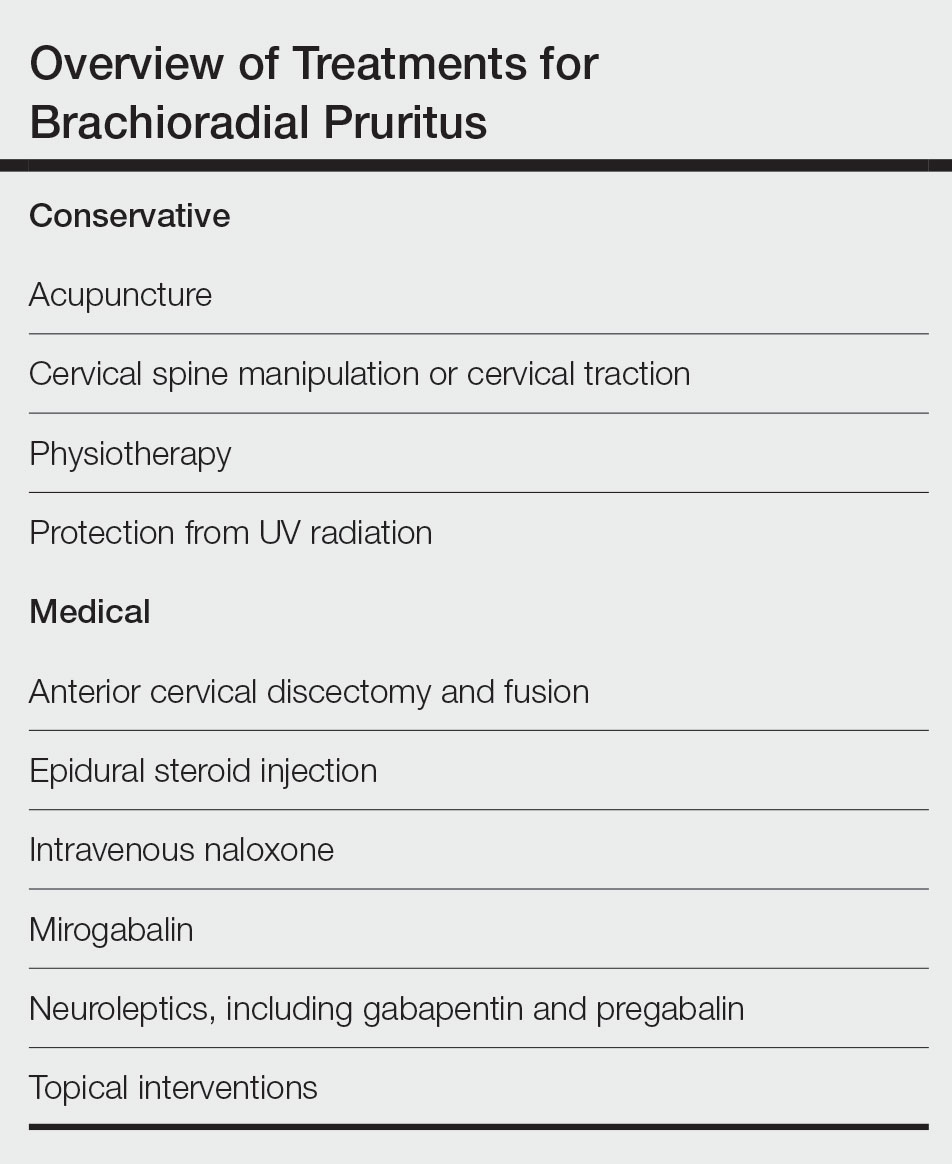

Brachioradial pruritus (BRP) is a neuropathic condition typically characterized by localized dysesthesia of the dorsolateral arms.1 This dysesthesia has been described as a persistent painful itching, burning, tingling, or stinging sensation2-4 and has a median duration of expression of 24 months.5,6 The condition may be unilateral or bilateral in nature but tends to have a predilection for a bilateral distribution along the C5 to C6 dermatomes.1,7,8 There are no primary skin lesions associated with BRP; however, excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichenification may arise secondary to scratching of the irritated skin.1,4,5,9 Brachioradial pruritus tends to have a predilection for adult females (3:1 ratio) with lighter skin. The mean age at diagnosis is 59 years, but cases have been reported in patients aged 12 to 84 years.1,5 The diagnosis of BRP is based on clinical signs and symptoms, though the ice-pack sign tends to be pathognomonic for the diagnosis.10,11 Although there is no clear evidence on the exact cause of BRP, there are 2 prevalent theories: cervical radiculopathy secondary to cervical spine pathology and/or excessive exposure to UV radiation (UVR) in the summer months.3-5,12 Brachioradial pruritus remains poorly described in the literature, and even its origin is under debate. As such, the clinician may have difficulty deciding on the best course of management. The goal of this article is to identify and discuss known treatment options for BRP (Table).

Etiology

Cervical Spine Pathology—A correlation appears to exist between BRP and cervical spine changes seen on plain film radiographs at the levels of C3 to C7, with increased incidence at the C5 to C6 levels. These plain film radiographs typically show degenerative joint disease and neural foraminal stenosis at levels that correlate to the dermatomal distribution of BRP.1,7,10,12-14 In addition to plain film radiography, some studies have utilized magnetic resonance imaging to view the cervical spine and have documented evidence of intervertebral disc protrusion/bulging, central canal stenosis, neuroforaminal stenosis, and spondylosis at the affected regions.5,15-17 Moreover, supporting the theory that the cervical spine is responsible for the emergence of BRP, Marziniak et al17 investigated 41 patients with BRP utilizing magnetic resonance tomography to find that 33 patients (80.5%) had changes in nerve compression, and 8 patients (19.5%) had degenerative changes. In addition to these findings, they found that there was a significant correlation (P<.01) between the dermatomal expression of BRP and the location of cervical anatomical changes.17 Further validating the relationship between cervical spine pathology and BRP is a case study of a patient who saw rapid and complete resolution of the pruritus following spinal decompression surgery.10 Another case study described an intramedullary tumor found in a patient with BRP that was diagnosed as an ependymoma after magnetic resonance imaging revealed an intramedullary lesion within the spinal cord between C4 and C7. The location of the tumor and dermatomal pattern of the neuropathic itch pointed to a possible association between nerve compression and BRP.14 Electromyography studies performed on individuals with BRP have shown an increase in polyphasic units, decreased motor units, and/or denervation changes along the C5/C6 or C6 nerve roots, which provides additional support for the theory of cervical spine pathology as a causative factor for BRP.16

UVR Exposure—Another etiologic theory for BRP is that UVR exposure may be responsible for the genesis of pruritus. Previously known as solar pruritus, BRP was deemed a clinical condition, as there was increased prevalence in patients living in warmer climates, such as Florida.9 Wallengren and Dahlbäck18 reported that sun exposure is a notable factor in the onset of BRP, as they saw an increase in symptoms during the late summer and a decrease in symptoms over the winter months. To further support the theory that UVR is linked to BRP, several studies have shown that the utilization of sun protection is linked to a reduction of symptoms, specifically in patients who showed seasonal variations of their symptoms.9,12,19 Additionally, a study by Mirzoyev and Davis5 retrospectively reviewed 111 patients diagnosed with BRP. Of these patients, 84 (75.7%) presented with bilateral symptoms, and 54 (48.6%) reported prolonged sun exposure. Both of these findings demonstrate correlation between UVR and BRP.5 Interestingly, UV light exposure is known to release β-endorphin in the skin and may theoretically provide an area of exploration between UVR and cervical spine theories.

Conservative Treatment

Chiropractic Manipulation—Because one etiologic theory includes disease of the cervical spine, there is evidence that targeting this region with treatment is beneficial.7 Two case reports found in the literature noted that cervical spine manipulation and cervical traction yielded positive results.20,21 It has been established that pain generated by disc lesions can be the result of local nociceptive fiber activation, direct mechanical compression of the nerve roots, or inflammatory mediators.22 There are several postulated models describing the hypoalgesic effects of spinal manipulation, which contains both biomechanical and neurophysiological mechanisms. Biomechanical changes theorized to elicit analgesia include restoration of faulty biomechanical movement patterns, breaking up of periarticular adhesions, and reflexogenic muscle inhibition of hypertonic musculature. Hypothesized neurophysiological effects of joint manipulation include an increase in afferent information overwhelming the nociceptive input, reduction of temporal summation, and autonomic activation leading to non–opioid-induced hypoalgesia.23 Cervical traction is another plausible treatment for BRP, wherein the physiological effects of traction allow for a separation of vertebral bodies and expansion of the intervertebral foramen circumference, thus decreasing compression of the nerve roots.24

Acupuncture—Neurogenic pruritus, including BRP, is a group of conditions that have been treated using acupuncture. Acupuncture treatment consists of intramuscular needle stimulation and has been found to alleviate itching in patients with neurogenic pruritus. In 1 retrospective case series, acupuncture was used to treat 16 patients who were identified as having segmental pruritus. Acupuncture targeted the spasmed paravertebral muscles of the affected dermatomal levels as well as other regions of the body, and it was found that 12 patients (75%) experienced full resolution of symptoms. However, relapse did occur in 6 patients (37%) within 1 to 12 months following treatment.25 Multiple theories exist as to why acupuncture may help. One is that it relieves muscle spasms, which in turn relieves neural irritation of the spinal nerves as they traverse the respective paraspinal musculature. Another is that acupuncture decreases nociception by stimulating release of opioid peptides in the dorsal horn.26 A third proposed theory is that acupuncture acts on the afferent nerve fibers responsible for transmitting pain—Aδ and C fibers—activating these afferent nerves to produce an analgesic effect.27

Physiotherapy—The literature suggests that possible first-line therapies for neurogenic pruritus, including BRP and notalgia paresthetica, consist of noninvasive nondermatologic treatments that target cervical spine disease. Notalgia paresthetica and BRP have similar proposed mechanisms of nerve impingement; therefore, they often are grouped together when discussing proposed manual treatment options. Physiotherapy treatment includes cervical muscle strengthening, increased range of motion, application of cervical soft collars, massage, transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation, and cervical traction.7 A study of 12 patients by Raison-Peyron et al28 in 1999 discussed the use of spinal and paraspinal ultrasound or radiation physiotherapy. Six patients underwent this treatment, and the symptoms subsided in 4 cases.28 Another study by Fleischer et al29 in 2011 discussed improvement in 2 patients with notalgia paresthetica by exercise involving active range of motion and strengthening.

Photoprotection—Avoidance of UVR exposure has been beneficial to some patients to reduce symptoms. Use of sunscreen and long-sleeved UV-protective clothing during outdoor activities or the warmer summer months may be beneficial.1

Medical Treatment

Medication—Because of the nonspecific clinical presentation of BRP, initial treatment often involves prescription of first-line antipruritic agents, including steroid creams and systemic antihistamines, both of which generally fail to provide symptom relief.1,30 Medications with neurologic mechanisms of action appear to provide potentially superior outcomes.

Topical interventions for BRP and related neurogenic pruritus have shown limited success. A case series evaluating capsaicin for pruritus offered only transient relief, likely because of its temporary hyperstimulatory and desensitizing effect on neuropeptides.7,33 In small populations, the use of topical antidepressants has yielded cutaneous and pathological relief for BRP. A case study of a 70-year-old woman evaluated the efficacy of a combination cream of ketamine and amitriptyline (a tricyclic antidepressant) yielding moderate pruritus improvement and notable improvement of secondary brachial skin lesions.34 Oral steroids also have shown success in the treatment of chronic pruritus; however, limited research is available on the efficacy of such medications for BRP, and the long-term use of oral steroids is limited by many side effects.30

Interventional Pain Procedure—A 2018 case series investigated 3 patients with a clinical diagnosis of BRP who were treated between 2010 and 2016 with

Surgery—There are multiple case studies in the literature that discuss

Conclusion

The pathogenesis of BRP continues to be an area of debate—it may be secondary to cervical spine disease or UVR. This review found there is more research pointing to cervical spine disease. There is an abundance of literature discussing both conservative and invasive treatment strategies, both of which carry benefits. Further research is needed to better establish the etiology of BRP so that formal treatment guidelines may be established.

Neuropathic itch can be a frustrating condition for providers and patients, and many treatment modalities often are tried before arriving at a helpful treatment for a particular patient. Clinicians who may encounter BRP in practice benefit from up-to-date literature reviews that provide a summary of management strategies.

- Robbins BA, Schmieder GJ. Brachioradial pruritus. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459321/

- Crevits L. Brachioradial pruritus—a peculiar neuropathic disorder. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:803-805.

- Lane J, McKenzie J, Spiegel J. Brachioradial pruritus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:37-40.

- Wallengren J. Brachioradial pruritus: a recurrent solar dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:803-806.

- Mirzoyev S, Davis M. Brachioradial pruritus: Mayo Clinic experience over the past decade. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1007-1015.

- Pinto AC, Wachholz PA, Masuda PY, et al. Clinical, epidemiological and therapeutic profile of patients with brachioradial pruritus in a reference service in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:549-551. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.201644767

- Alai NN, Skinner HB. Concurrent notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus associated with cervical degenerative disc disease. Cutis. 2018;102:185, 186, 189, 190.

- Atis¸ G, Bilir Kaya B. Pregabalin treatment of three cases with brachioradial pruritus. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:e12459.

- Waisman M. Solar pruritus of the elbows (brachioradial summer pruritus). Arch Dermatol. 1968;98:481-485.

- Binder A, Fölster-Holst R, Sahan G, et al. A case of neuropathic brachioradial pruritus caused by cervical disc herniation. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:338-342.

- Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Medical pearl: the ice-pack sign in brachioradial pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1073.

- Veien N, Laurberg G. Brachioradial pruritus: a follow-up of 76 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:183-185.

- Mataix J, Silvestre JF, Climent JM, et al. Brachioradial pruritus as a symptom of cervical radiculopathy. Article in Spanish. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:719-722.

- Kavak A, Dosoglu M. Can a spinal cord tumor cause brachioradial pruritus? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:437-440.

- Zeidler C, Pereira MP, Ständer S. Brachioradial pruritus successfully treated with intravenous naloxone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:e87-e89. doi:10.1111/jdv.18553

- Shields LB, Iyer VG, Zhang Y, et al. Brachioradial pruritus: clinical, electromyographic, and cervical MRI features in nine patients. Cureus. 2022;14:e21811. doi:10.7759/cureus.21811

- Marziniak M, Phan NQ, Raap U, et al. Brachioradial pruritus as a result of cervical spine pathology: the results of a magneticresonance tomography study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:756-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.036

- Wallengren J, Dahlbäck K. Familial brachioradial pruritus. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1016-1018.

- Salzmann SN, Okano I, Shue J, et al. Disabling pruritus in a patient with cervical stenosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4:e19.00178. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00178

- Golden KJ, Diana RM. A case of brachioradial pruritus treated with chiropractic and acupuncture. Case Rep Dermatol. 2022;14:93-97. doi:10.1159/000524054

- Tait CP, Grigg E, Quirk CJ. Brachioradial pruritus and cervical spine manipulation. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:168-170. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01274.x

- Freynhagen R, Baron R. The evaluation of neuropathic components in low back pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13:185-190. doi:10.1007/s11916-009-0032-y

- Gyer G, Michael J, Inklebarger J, et al. Spinal manipulation therapy: is it all about the brain? A current review of the neurophysiological effects of manipulation. J Integr Med. 2019;17:328-337. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2019.05.004

- Graham N, Gross A, Goldsmith CH, et al. Mechanical traction for neck pain with or without radiculopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006408. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006408.pub2

- Stellon A. Neurogenic pruritus: an unrecognised problem? A retrospective case series of treatment by acupuncture. Acupunct Med. 2002;20:186-190. doi:10.1136/aim.20.4.186

- Bowsher D. Mechanisms of acupuncture. In: Filshie J, White A, eds. Medical Acupuncture: A Western Scientific Approach. Churchill Livingstone; 1998:69-82.

- Lim TK, Ma Y, Berger F, et al. Acupuncture and neural mechanism in the management of low back pain-an update. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5:63.

- Raison-Peyron N, Meunier L, Acevedo M, et al. Notalgia paresthetica: clinical, physiopathological and therapeutic aspects. a study of 12 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:215-221.

- Fleischer AB, Meade TJ, Fleischer AB. Notalgia paresthetica: successful treatment with exercises. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:356-357. doi:10.2340/00015555-1039

- Kouwenhoven TA, van de Kerkhof PCM, Kamsteeg M. Use of oral antidepressants in patients with chronic pruritus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1068-1073.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.025

- Matsuda KM, Sharma D, Schonfeld AR, et al. Gabapentin and pregabalin for the treatment of chronic pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:619-625.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1237

- Okuno S, Hashimoto T, Satoh T. Case of neuropathic itch-associated prurigo nodules on the bilateral upper arms after unilateral herpes zoster in a patient with cervical herniated discs: successful treatment with mirogabalin. J Dermatol. 2021;48:e585-e586.

- Papoiu AD, Yosipovitch G. Topical capsaicin. The fire of a ‘hot’ medicine is reignited. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1359-1371. doi:10.1517/14656566.2010.481670

- Magazin M, Daze RP, Okeson N. Treatment refractory brachioradial pruritus treated with topical amitriptyline and ketamine. Cureus. 2019;11:e5117. doi:10.7759/cureus.5117

- Weinberg BD, Amans M, Deviren S, et al. Brachioradial pruritus treated with computed tomography-guided cervical nerve root block: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:640-644. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.03.025

- De Ridder D, Hans G, Pals P, et al. A C-fiber-mediated neuropathic brachioradial pruritus. J Neurosurg. 2010;113:118-121. doi:10.3171/2009.9.JNS09620

- Morosanu CO, Etim G, Alalade AF. Brachioradial pruritus secondary to cervical disc protrusion—a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2022:rjac277. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjac277

Brachioradial pruritus (BRP) is a neuropathic condition typically characterized by localized dysesthesia of the dorsolateral arms.1 This dysesthesia has been described as a persistent painful itching, burning, tingling, or stinging sensation2-4 and has a median duration of expression of 24 months.5,6 The condition may be unilateral or bilateral in nature but tends to have a predilection for a bilateral distribution along the C5 to C6 dermatomes.1,7,8 There are no primary skin lesions associated with BRP; however, excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichenification may arise secondary to scratching of the irritated skin.1,4,5,9 Brachioradial pruritus tends to have a predilection for adult females (3:1 ratio) with lighter skin. The mean age at diagnosis is 59 years, but cases have been reported in patients aged 12 to 84 years.1,5 The diagnosis of BRP is based on clinical signs and symptoms, though the ice-pack sign tends to be pathognomonic for the diagnosis.10,11 Although there is no clear evidence on the exact cause of BRP, there are 2 prevalent theories: cervical radiculopathy secondary to cervical spine pathology and/or excessive exposure to UV radiation (UVR) in the summer months.3-5,12 Brachioradial pruritus remains poorly described in the literature, and even its origin is under debate. As such, the clinician may have difficulty deciding on the best course of management. The goal of this article is to identify and discuss known treatment options for BRP (Table).

Etiology

Cervical Spine Pathology—A correlation appears to exist between BRP and cervical spine changes seen on plain film radiographs at the levels of C3 to C7, with increased incidence at the C5 to C6 levels. These plain film radiographs typically show degenerative joint disease and neural foraminal stenosis at levels that correlate to the dermatomal distribution of BRP.1,7,10,12-14 In addition to plain film radiography, some studies have utilized magnetic resonance imaging to view the cervical spine and have documented evidence of intervertebral disc protrusion/bulging, central canal stenosis, neuroforaminal stenosis, and spondylosis at the affected regions.5,15-17 Moreover, supporting the theory that the cervical spine is responsible for the emergence of BRP, Marziniak et al17 investigated 41 patients with BRP utilizing magnetic resonance tomography to find that 33 patients (80.5%) had changes in nerve compression, and 8 patients (19.5%) had degenerative changes. In addition to these findings, they found that there was a significant correlation (P<.01) between the dermatomal expression of BRP and the location of cervical anatomical changes.17 Further validating the relationship between cervical spine pathology and BRP is a case study of a patient who saw rapid and complete resolution of the pruritus following spinal decompression surgery.10 Another case study described an intramedullary tumor found in a patient with BRP that was diagnosed as an ependymoma after magnetic resonance imaging revealed an intramedullary lesion within the spinal cord between C4 and C7. The location of the tumor and dermatomal pattern of the neuropathic itch pointed to a possible association between nerve compression and BRP.14 Electromyography studies performed on individuals with BRP have shown an increase in polyphasic units, decreased motor units, and/or denervation changes along the C5/C6 or C6 nerve roots, which provides additional support for the theory of cervical spine pathology as a causative factor for BRP.16

UVR Exposure—Another etiologic theory for BRP is that UVR exposure may be responsible for the genesis of pruritus. Previously known as solar pruritus, BRP was deemed a clinical condition, as there was increased prevalence in patients living in warmer climates, such as Florida.9 Wallengren and Dahlbäck18 reported that sun exposure is a notable factor in the onset of BRP, as they saw an increase in symptoms during the late summer and a decrease in symptoms over the winter months. To further support the theory that UVR is linked to BRP, several studies have shown that the utilization of sun protection is linked to a reduction of symptoms, specifically in patients who showed seasonal variations of their symptoms.9,12,19 Additionally, a study by Mirzoyev and Davis5 retrospectively reviewed 111 patients diagnosed with BRP. Of these patients, 84 (75.7%) presented with bilateral symptoms, and 54 (48.6%) reported prolonged sun exposure. Both of these findings demonstrate correlation between UVR and BRP.5 Interestingly, UV light exposure is known to release β-endorphin in the skin and may theoretically provide an area of exploration between UVR and cervical spine theories.

Conservative Treatment

Chiropractic Manipulation—Because one etiologic theory includes disease of the cervical spine, there is evidence that targeting this region with treatment is beneficial.7 Two case reports found in the literature noted that cervical spine manipulation and cervical traction yielded positive results.20,21 It has been established that pain generated by disc lesions can be the result of local nociceptive fiber activation, direct mechanical compression of the nerve roots, or inflammatory mediators.22 There are several postulated models describing the hypoalgesic effects of spinal manipulation, which contains both biomechanical and neurophysiological mechanisms. Biomechanical changes theorized to elicit analgesia include restoration of faulty biomechanical movement patterns, breaking up of periarticular adhesions, and reflexogenic muscle inhibition of hypertonic musculature. Hypothesized neurophysiological effects of joint manipulation include an increase in afferent information overwhelming the nociceptive input, reduction of temporal summation, and autonomic activation leading to non–opioid-induced hypoalgesia.23 Cervical traction is another plausible treatment for BRP, wherein the physiological effects of traction allow for a separation of vertebral bodies and expansion of the intervertebral foramen circumference, thus decreasing compression of the nerve roots.24

Acupuncture—Neurogenic pruritus, including BRP, is a group of conditions that have been treated using acupuncture. Acupuncture treatment consists of intramuscular needle stimulation and has been found to alleviate itching in patients with neurogenic pruritus. In 1 retrospective case series, acupuncture was used to treat 16 patients who were identified as having segmental pruritus. Acupuncture targeted the spasmed paravertebral muscles of the affected dermatomal levels as well as other regions of the body, and it was found that 12 patients (75%) experienced full resolution of symptoms. However, relapse did occur in 6 patients (37%) within 1 to 12 months following treatment.25 Multiple theories exist as to why acupuncture may help. One is that it relieves muscle spasms, which in turn relieves neural irritation of the spinal nerves as they traverse the respective paraspinal musculature. Another is that acupuncture decreases nociception by stimulating release of opioid peptides in the dorsal horn.26 A third proposed theory is that acupuncture acts on the afferent nerve fibers responsible for transmitting pain—Aδ and C fibers—activating these afferent nerves to produce an analgesic effect.27

Physiotherapy—The literature suggests that possible first-line therapies for neurogenic pruritus, including BRP and notalgia paresthetica, consist of noninvasive nondermatologic treatments that target cervical spine disease. Notalgia paresthetica and BRP have similar proposed mechanisms of nerve impingement; therefore, they often are grouped together when discussing proposed manual treatment options. Physiotherapy treatment includes cervical muscle strengthening, increased range of motion, application of cervical soft collars, massage, transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation, and cervical traction.7 A study of 12 patients by Raison-Peyron et al28 in 1999 discussed the use of spinal and paraspinal ultrasound or radiation physiotherapy. Six patients underwent this treatment, and the symptoms subsided in 4 cases.28 Another study by Fleischer et al29 in 2011 discussed improvement in 2 patients with notalgia paresthetica by exercise involving active range of motion and strengthening.

Photoprotection—Avoidance of UVR exposure has been beneficial to some patients to reduce symptoms. Use of sunscreen and long-sleeved UV-protective clothing during outdoor activities or the warmer summer months may be beneficial.1

Medical Treatment

Medication—Because of the nonspecific clinical presentation of BRP, initial treatment often involves prescription of first-line antipruritic agents, including steroid creams and systemic antihistamines, both of which generally fail to provide symptom relief.1,30 Medications with neurologic mechanisms of action appear to provide potentially superior outcomes.

Topical interventions for BRP and related neurogenic pruritus have shown limited success. A case series evaluating capsaicin for pruritus offered only transient relief, likely because of its temporary hyperstimulatory and desensitizing effect on neuropeptides.7,33 In small populations, the use of topical antidepressants has yielded cutaneous and pathological relief for BRP. A case study of a 70-year-old woman evaluated the efficacy of a combination cream of ketamine and amitriptyline (a tricyclic antidepressant) yielding moderate pruritus improvement and notable improvement of secondary brachial skin lesions.34 Oral steroids also have shown success in the treatment of chronic pruritus; however, limited research is available on the efficacy of such medications for BRP, and the long-term use of oral steroids is limited by many side effects.30

Interventional Pain Procedure—A 2018 case series investigated 3 patients with a clinical diagnosis of BRP who were treated between 2010 and 2016 with

Surgery—There are multiple case studies in the literature that discuss

Conclusion

The pathogenesis of BRP continues to be an area of debate—it may be secondary to cervical spine disease or UVR. This review found there is more research pointing to cervical spine disease. There is an abundance of literature discussing both conservative and invasive treatment strategies, both of which carry benefits. Further research is needed to better establish the etiology of BRP so that formal treatment guidelines may be established.

Neuropathic itch can be a frustrating condition for providers and patients, and many treatment modalities often are tried before arriving at a helpful treatment for a particular patient. Clinicians who may encounter BRP in practice benefit from up-to-date literature reviews that provide a summary of management strategies.

Brachioradial pruritus (BRP) is a neuropathic condition typically characterized by localized dysesthesia of the dorsolateral arms.1 This dysesthesia has been described as a persistent painful itching, burning, tingling, or stinging sensation2-4 and has a median duration of expression of 24 months.5,6 The condition may be unilateral or bilateral in nature but tends to have a predilection for a bilateral distribution along the C5 to C6 dermatomes.1,7,8 There are no primary skin lesions associated with BRP; however, excoriations, prurigo nodules, and lichenification may arise secondary to scratching of the irritated skin.1,4,5,9 Brachioradial pruritus tends to have a predilection for adult females (3:1 ratio) with lighter skin. The mean age at diagnosis is 59 years, but cases have been reported in patients aged 12 to 84 years.1,5 The diagnosis of BRP is based on clinical signs and symptoms, though the ice-pack sign tends to be pathognomonic for the diagnosis.10,11 Although there is no clear evidence on the exact cause of BRP, there are 2 prevalent theories: cervical radiculopathy secondary to cervical spine pathology and/or excessive exposure to UV radiation (UVR) in the summer months.3-5,12 Brachioradial pruritus remains poorly described in the literature, and even its origin is under debate. As such, the clinician may have difficulty deciding on the best course of management. The goal of this article is to identify and discuss known treatment options for BRP (Table).

Etiology

Cervical Spine Pathology—A correlation appears to exist between BRP and cervical spine changes seen on plain film radiographs at the levels of C3 to C7, with increased incidence at the C5 to C6 levels. These plain film radiographs typically show degenerative joint disease and neural foraminal stenosis at levels that correlate to the dermatomal distribution of BRP.1,7,10,12-14 In addition to plain film radiography, some studies have utilized magnetic resonance imaging to view the cervical spine and have documented evidence of intervertebral disc protrusion/bulging, central canal stenosis, neuroforaminal stenosis, and spondylosis at the affected regions.5,15-17 Moreover, supporting the theory that the cervical spine is responsible for the emergence of BRP, Marziniak et al17 investigated 41 patients with BRP utilizing magnetic resonance tomography to find that 33 patients (80.5%) had changes in nerve compression, and 8 patients (19.5%) had degenerative changes. In addition to these findings, they found that there was a significant correlation (P<.01) between the dermatomal expression of BRP and the location of cervical anatomical changes.17 Further validating the relationship between cervical spine pathology and BRP is a case study of a patient who saw rapid and complete resolution of the pruritus following spinal decompression surgery.10 Another case study described an intramedullary tumor found in a patient with BRP that was diagnosed as an ependymoma after magnetic resonance imaging revealed an intramedullary lesion within the spinal cord between C4 and C7. The location of the tumor and dermatomal pattern of the neuropathic itch pointed to a possible association between nerve compression and BRP.14 Electromyography studies performed on individuals with BRP have shown an increase in polyphasic units, decreased motor units, and/or denervation changes along the C5/C6 or C6 nerve roots, which provides additional support for the theory of cervical spine pathology as a causative factor for BRP.16

UVR Exposure—Another etiologic theory for BRP is that UVR exposure may be responsible for the genesis of pruritus. Previously known as solar pruritus, BRP was deemed a clinical condition, as there was increased prevalence in patients living in warmer climates, such as Florida.9 Wallengren and Dahlbäck18 reported that sun exposure is a notable factor in the onset of BRP, as they saw an increase in symptoms during the late summer and a decrease in symptoms over the winter months. To further support the theory that UVR is linked to BRP, several studies have shown that the utilization of sun protection is linked to a reduction of symptoms, specifically in patients who showed seasonal variations of their symptoms.9,12,19 Additionally, a study by Mirzoyev and Davis5 retrospectively reviewed 111 patients diagnosed with BRP. Of these patients, 84 (75.7%) presented with bilateral symptoms, and 54 (48.6%) reported prolonged sun exposure. Both of these findings demonstrate correlation between UVR and BRP.5 Interestingly, UV light exposure is known to release β-endorphin in the skin and may theoretically provide an area of exploration between UVR and cervical spine theories.

Conservative Treatment

Chiropractic Manipulation—Because one etiologic theory includes disease of the cervical spine, there is evidence that targeting this region with treatment is beneficial.7 Two case reports found in the literature noted that cervical spine manipulation and cervical traction yielded positive results.20,21 It has been established that pain generated by disc lesions can be the result of local nociceptive fiber activation, direct mechanical compression of the nerve roots, or inflammatory mediators.22 There are several postulated models describing the hypoalgesic effects of spinal manipulation, which contains both biomechanical and neurophysiological mechanisms. Biomechanical changes theorized to elicit analgesia include restoration of faulty biomechanical movement patterns, breaking up of periarticular adhesions, and reflexogenic muscle inhibition of hypertonic musculature. Hypothesized neurophysiological effects of joint manipulation include an increase in afferent information overwhelming the nociceptive input, reduction of temporal summation, and autonomic activation leading to non–opioid-induced hypoalgesia.23 Cervical traction is another plausible treatment for BRP, wherein the physiological effects of traction allow for a separation of vertebral bodies and expansion of the intervertebral foramen circumference, thus decreasing compression of the nerve roots.24

Acupuncture—Neurogenic pruritus, including BRP, is a group of conditions that have been treated using acupuncture. Acupuncture treatment consists of intramuscular needle stimulation and has been found to alleviate itching in patients with neurogenic pruritus. In 1 retrospective case series, acupuncture was used to treat 16 patients who were identified as having segmental pruritus. Acupuncture targeted the spasmed paravertebral muscles of the affected dermatomal levels as well as other regions of the body, and it was found that 12 patients (75%) experienced full resolution of symptoms. However, relapse did occur in 6 patients (37%) within 1 to 12 months following treatment.25 Multiple theories exist as to why acupuncture may help. One is that it relieves muscle spasms, which in turn relieves neural irritation of the spinal nerves as they traverse the respective paraspinal musculature. Another is that acupuncture decreases nociception by stimulating release of opioid peptides in the dorsal horn.26 A third proposed theory is that acupuncture acts on the afferent nerve fibers responsible for transmitting pain—Aδ and C fibers—activating these afferent nerves to produce an analgesic effect.27

Physiotherapy—The literature suggests that possible first-line therapies for neurogenic pruritus, including BRP and notalgia paresthetica, consist of noninvasive nondermatologic treatments that target cervical spine disease. Notalgia paresthetica and BRP have similar proposed mechanisms of nerve impingement; therefore, they often are grouped together when discussing proposed manual treatment options. Physiotherapy treatment includes cervical muscle strengthening, increased range of motion, application of cervical soft collars, massage, transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation, and cervical traction.7 A study of 12 patients by Raison-Peyron et al28 in 1999 discussed the use of spinal and paraspinal ultrasound or radiation physiotherapy. Six patients underwent this treatment, and the symptoms subsided in 4 cases.28 Another study by Fleischer et al29 in 2011 discussed improvement in 2 patients with notalgia paresthetica by exercise involving active range of motion and strengthening.

Photoprotection—Avoidance of UVR exposure has been beneficial to some patients to reduce symptoms. Use of sunscreen and long-sleeved UV-protective clothing during outdoor activities or the warmer summer months may be beneficial.1

Medical Treatment

Medication—Because of the nonspecific clinical presentation of BRP, initial treatment often involves prescription of first-line antipruritic agents, including steroid creams and systemic antihistamines, both of which generally fail to provide symptom relief.1,30 Medications with neurologic mechanisms of action appear to provide potentially superior outcomes.

Topical interventions for BRP and related neurogenic pruritus have shown limited success. A case series evaluating capsaicin for pruritus offered only transient relief, likely because of its temporary hyperstimulatory and desensitizing effect on neuropeptides.7,33 In small populations, the use of topical antidepressants has yielded cutaneous and pathological relief for BRP. A case study of a 70-year-old woman evaluated the efficacy of a combination cream of ketamine and amitriptyline (a tricyclic antidepressant) yielding moderate pruritus improvement and notable improvement of secondary brachial skin lesions.34 Oral steroids also have shown success in the treatment of chronic pruritus; however, limited research is available on the efficacy of such medications for BRP, and the long-term use of oral steroids is limited by many side effects.30

Interventional Pain Procedure—A 2018 case series investigated 3 patients with a clinical diagnosis of BRP who were treated between 2010 and 2016 with

Surgery—There are multiple case studies in the literature that discuss

Conclusion

The pathogenesis of BRP continues to be an area of debate—it may be secondary to cervical spine disease or UVR. This review found there is more research pointing to cervical spine disease. There is an abundance of literature discussing both conservative and invasive treatment strategies, both of which carry benefits. Further research is needed to better establish the etiology of BRP so that formal treatment guidelines may be established.

Neuropathic itch can be a frustrating condition for providers and patients, and many treatment modalities often are tried before arriving at a helpful treatment for a particular patient. Clinicians who may encounter BRP in practice benefit from up-to-date literature reviews that provide a summary of management strategies.

- Robbins BA, Schmieder GJ. Brachioradial pruritus. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459321/

- Crevits L. Brachioradial pruritus—a peculiar neuropathic disorder. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:803-805.

- Lane J, McKenzie J, Spiegel J. Brachioradial pruritus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:37-40.

- Wallengren J. Brachioradial pruritus: a recurrent solar dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:803-806.

- Mirzoyev S, Davis M. Brachioradial pruritus: Mayo Clinic experience over the past decade. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1007-1015.

- Pinto AC, Wachholz PA, Masuda PY, et al. Clinical, epidemiological and therapeutic profile of patients with brachioradial pruritus in a reference service in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:549-551. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.201644767

- Alai NN, Skinner HB. Concurrent notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus associated with cervical degenerative disc disease. Cutis. 2018;102:185, 186, 189, 190.

- Atis¸ G, Bilir Kaya B. Pregabalin treatment of three cases with brachioradial pruritus. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:e12459.

- Waisman M. Solar pruritus of the elbows (brachioradial summer pruritus). Arch Dermatol. 1968;98:481-485.

- Binder A, Fölster-Holst R, Sahan G, et al. A case of neuropathic brachioradial pruritus caused by cervical disc herniation. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:338-342.

- Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Medical pearl: the ice-pack sign in brachioradial pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1073.

- Veien N, Laurberg G. Brachioradial pruritus: a follow-up of 76 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:183-185.

- Mataix J, Silvestre JF, Climent JM, et al. Brachioradial pruritus as a symptom of cervical radiculopathy. Article in Spanish. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:719-722.

- Kavak A, Dosoglu M. Can a spinal cord tumor cause brachioradial pruritus? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:437-440.

- Zeidler C, Pereira MP, Ständer S. Brachioradial pruritus successfully treated with intravenous naloxone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:e87-e89. doi:10.1111/jdv.18553

- Shields LB, Iyer VG, Zhang Y, et al. Brachioradial pruritus: clinical, electromyographic, and cervical MRI features in nine patients. Cureus. 2022;14:e21811. doi:10.7759/cureus.21811

- Marziniak M, Phan NQ, Raap U, et al. Brachioradial pruritus as a result of cervical spine pathology: the results of a magneticresonance tomography study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:756-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.036

- Wallengren J, Dahlbäck K. Familial brachioradial pruritus. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1016-1018.

- Salzmann SN, Okano I, Shue J, et al. Disabling pruritus in a patient with cervical stenosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4:e19.00178. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00178

- Golden KJ, Diana RM. A case of brachioradial pruritus treated with chiropractic and acupuncture. Case Rep Dermatol. 2022;14:93-97. doi:10.1159/000524054

- Tait CP, Grigg E, Quirk CJ. Brachioradial pruritus and cervical spine manipulation. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:168-170. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01274.x

- Freynhagen R, Baron R. The evaluation of neuropathic components in low back pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13:185-190. doi:10.1007/s11916-009-0032-y

- Gyer G, Michael J, Inklebarger J, et al. Spinal manipulation therapy: is it all about the brain? A current review of the neurophysiological effects of manipulation. J Integr Med. 2019;17:328-337. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2019.05.004

- Graham N, Gross A, Goldsmith CH, et al. Mechanical traction for neck pain with or without radiculopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006408. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006408.pub2

- Stellon A. Neurogenic pruritus: an unrecognised problem? A retrospective case series of treatment by acupuncture. Acupunct Med. 2002;20:186-190. doi:10.1136/aim.20.4.186

- Bowsher D. Mechanisms of acupuncture. In: Filshie J, White A, eds. Medical Acupuncture: A Western Scientific Approach. Churchill Livingstone; 1998:69-82.

- Lim TK, Ma Y, Berger F, et al. Acupuncture and neural mechanism in the management of low back pain-an update. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5:63.

- Raison-Peyron N, Meunier L, Acevedo M, et al. Notalgia paresthetica: clinical, physiopathological and therapeutic aspects. a study of 12 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:215-221.

- Fleischer AB, Meade TJ, Fleischer AB. Notalgia paresthetica: successful treatment with exercises. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:356-357. doi:10.2340/00015555-1039

- Kouwenhoven TA, van de Kerkhof PCM, Kamsteeg M. Use of oral antidepressants in patients with chronic pruritus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1068-1073.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.025

- Matsuda KM, Sharma D, Schonfeld AR, et al. Gabapentin and pregabalin for the treatment of chronic pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:619-625.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1237

- Okuno S, Hashimoto T, Satoh T. Case of neuropathic itch-associated prurigo nodules on the bilateral upper arms after unilateral herpes zoster in a patient with cervical herniated discs: successful treatment with mirogabalin. J Dermatol. 2021;48:e585-e586.

- Papoiu AD, Yosipovitch G. Topical capsaicin. The fire of a ‘hot’ medicine is reignited. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1359-1371. doi:10.1517/14656566.2010.481670

- Magazin M, Daze RP, Okeson N. Treatment refractory brachioradial pruritus treated with topical amitriptyline and ketamine. Cureus. 2019;11:e5117. doi:10.7759/cureus.5117

- Weinberg BD, Amans M, Deviren S, et al. Brachioradial pruritus treated with computed tomography-guided cervical nerve root block: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:640-644. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.03.025

- De Ridder D, Hans G, Pals P, et al. A C-fiber-mediated neuropathic brachioradial pruritus. J Neurosurg. 2010;113:118-121. doi:10.3171/2009.9.JNS09620

- Morosanu CO, Etim G, Alalade AF. Brachioradial pruritus secondary to cervical disc protrusion—a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2022:rjac277. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjac277

- Robbins BA, Schmieder GJ. Brachioradial pruritus. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459321/

- Crevits L. Brachioradial pruritus—a peculiar neuropathic disorder. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:803-805.

- Lane J, McKenzie J, Spiegel J. Brachioradial pruritus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:37-40.

- Wallengren J. Brachioradial pruritus: a recurrent solar dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:803-806.

- Mirzoyev S, Davis M. Brachioradial pruritus: Mayo Clinic experience over the past decade. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1007-1015.

- Pinto AC, Wachholz PA, Masuda PY, et al. Clinical, epidemiological and therapeutic profile of patients with brachioradial pruritus in a reference service in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:549-551. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.201644767

- Alai NN, Skinner HB. Concurrent notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus associated with cervical degenerative disc disease. Cutis. 2018;102:185, 186, 189, 190.

- Atis¸ G, Bilir Kaya B. Pregabalin treatment of three cases with brachioradial pruritus. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:e12459.

- Waisman M. Solar pruritus of the elbows (brachioradial summer pruritus). Arch Dermatol. 1968;98:481-485.

- Binder A, Fölster-Holst R, Sahan G, et al. A case of neuropathic brachioradial pruritus caused by cervical disc herniation. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:338-342.

- Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Medical pearl: the ice-pack sign in brachioradial pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1073.

- Veien N, Laurberg G. Brachioradial pruritus: a follow-up of 76 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:183-185.

- Mataix J, Silvestre JF, Climent JM, et al. Brachioradial pruritus as a symptom of cervical radiculopathy. Article in Spanish. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:719-722.

- Kavak A, Dosoglu M. Can a spinal cord tumor cause brachioradial pruritus? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:437-440.

- Zeidler C, Pereira MP, Ständer S. Brachioradial pruritus successfully treated with intravenous naloxone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:e87-e89. doi:10.1111/jdv.18553

- Shields LB, Iyer VG, Zhang Y, et al. Brachioradial pruritus: clinical, electromyographic, and cervical MRI features in nine patients. Cureus. 2022;14:e21811. doi:10.7759/cureus.21811

- Marziniak M, Phan NQ, Raap U, et al. Brachioradial pruritus as a result of cervical spine pathology: the results of a magneticresonance tomography study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:756-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.036

- Wallengren J, Dahlbäck K. Familial brachioradial pruritus. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1016-1018.

- Salzmann SN, Okano I, Shue J, et al. Disabling pruritus in a patient with cervical stenosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4:e19.00178. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00178

- Golden KJ, Diana RM. A case of brachioradial pruritus treated with chiropractic and acupuncture. Case Rep Dermatol. 2022;14:93-97. doi:10.1159/000524054

- Tait CP, Grigg E, Quirk CJ. Brachioradial pruritus and cervical spine manipulation. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:168-170. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01274.x

- Freynhagen R, Baron R. The evaluation of neuropathic components in low back pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13:185-190. doi:10.1007/s11916-009-0032-y

- Gyer G, Michael J, Inklebarger J, et al. Spinal manipulation therapy: is it all about the brain? A current review of the neurophysiological effects of manipulation. J Integr Med. 2019;17:328-337. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2019.05.004

- Graham N, Gross A, Goldsmith CH, et al. Mechanical traction for neck pain with or without radiculopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006408. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006408.pub2

- Stellon A. Neurogenic pruritus: an unrecognised problem? A retrospective case series of treatment by acupuncture. Acupunct Med. 2002;20:186-190. doi:10.1136/aim.20.4.186

- Bowsher D. Mechanisms of acupuncture. In: Filshie J, White A, eds. Medical Acupuncture: A Western Scientific Approach. Churchill Livingstone; 1998:69-82.

- Lim TK, Ma Y, Berger F, et al. Acupuncture and neural mechanism in the management of low back pain-an update. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5:63.

- Raison-Peyron N, Meunier L, Acevedo M, et al. Notalgia paresthetica: clinical, physiopathological and therapeutic aspects. a study of 12 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:215-221.

- Fleischer AB, Meade TJ, Fleischer AB. Notalgia paresthetica: successful treatment with exercises. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:356-357. doi:10.2340/00015555-1039

- Kouwenhoven TA, van de Kerkhof PCM, Kamsteeg M. Use of oral antidepressants in patients with chronic pruritus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1068-1073.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.025

- Matsuda KM, Sharma D, Schonfeld AR, et al. Gabapentin and pregabalin for the treatment of chronic pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:619-625.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1237

- Okuno S, Hashimoto T, Satoh T. Case of neuropathic itch-associated prurigo nodules on the bilateral upper arms after unilateral herpes zoster in a patient with cervical herniated discs: successful treatment with mirogabalin. J Dermatol. 2021;48:e585-e586.

- Papoiu AD, Yosipovitch G. Topical capsaicin. The fire of a ‘hot’ medicine is reignited. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1359-1371. doi:10.1517/14656566.2010.481670

- Magazin M, Daze RP, Okeson N. Treatment refractory brachioradial pruritus treated with topical amitriptyline and ketamine. Cureus. 2019;11:e5117. doi:10.7759/cureus.5117

- Weinberg BD, Amans M, Deviren S, et al. Brachioradial pruritus treated with computed tomography-guided cervical nerve root block: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:640-644. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.03.025

- De Ridder D, Hans G, Pals P, et al. A C-fiber-mediated neuropathic brachioradial pruritus. J Neurosurg. 2010;113:118-121. doi:10.3171/2009.9.JNS09620

- Morosanu CO, Etim G, Alalade AF. Brachioradial pruritus secondary to cervical disc protrusion—a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2022:rjac277. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjac277

Practice Points

- The etiology of brachioradial pruritus (BRP) has been associated with cervical spine pathology and/or UV radiation exposure.

- Treatment options for BRP range from conservative to invasive, and clinicians should consider the evidence for all options to decide what is best for each patient.

Pruritic rash on trunk

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC MAN came into our dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of a pruritic rash that was confined mainly to the trunk. Prior to this visit, he had tried topical corticosteroids and antifungals, but they had not helped.

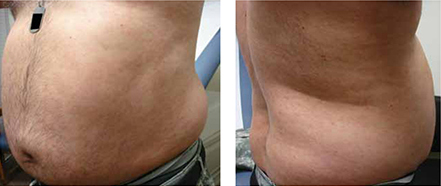

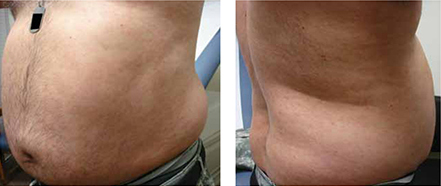

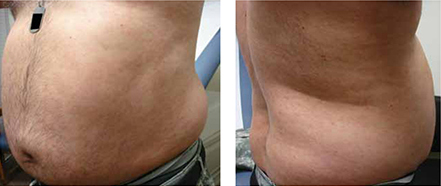

His trunk showed erythematous macules and reticulate patches with interspersed thin urticarial plaques without scale (FIGURE). Given that the patient had no vesicles or lichenification (which one would expect with eczematous dermatitis) and that the topical steroids did not provide any relief, we performed a biopsy.

FIGURE

Erythematous macules and reticulate patches without scale

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate. On higher magnification, the infiltrate proved to be predominately plasma cells. After further investigation and interview, the patient revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women; his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as “the great imitator.” Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. With the worldwide HIV epidemic, safe sex programs effectively dropped the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States to the lowest in recorded history in the year 2001 at 2.17/100,000.1

More recently, however, this infection appears to be making a comeback. Beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.1

Secondary syphilis usually appears 6 to 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. As the pathogen spreads into the bloodstream, a host of systemic symptoms may occur, including an influenza-like illness of body aches, fever, fatigue, and headache. While the exanthem of secondary syphilis is traditionally described as a nonpruritic, papular eruption involving the trunk, extremities, face, palms, and soles, a number of cutaneous manifestations are possible, including localized alopecia and syphilids.2 In addition, a number of atypical cases are described in the literature, although none has described an urticarial variant, as seen in our case.

The differential included urticaria and lupus erythematosus

The differential diagnosis for our patient included urticaria, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and mycosis fungoides. All of these conditions can be distinguished from secondary syphilis by serology and/or biopsy.

Urticaria is a common dermatologic problem with numerous etiologies. It presents as pruritic raised edematous erythematous wheels that blanch with pressure. Although it affects 15% to 25% of the general population at least once in their lives,3 it may progress to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Isolated acute urticaria usually responds to oral antihistamines.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis that appears as persistent macules that are red to brown and may exhibit telangiectasia.4 Systemic disease may be evaluated using serum tryptase levels. Patients without systemic disease are managed with oral antihistamines.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) often presents precipitously as erythematous maculopapular lesions that may coalesce into annular or papulosquamous plaques.5 It has a predilection for sun-exposed areas and is more common in women.5 Multiple drugs have been associated with SCLE, including phenytoin, calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.6 Treatment consists of discontinuing the offending drug (if one is identified), avoiding (or protecting against) sun exposure, and using topical corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials.

Mycosis fungoides is a form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that more commonly affects males.7 It begins as erythematous pruritic patches that typically involve the sun-spared areas of the lower abdomen and proximal extremities; it progresses slowly.7 As lesions develop into plaques, they may appear psoriasiform. Treatment depends on the stage of the disease and ranges from topical corticosteroids to systemic radiation and chemotherapy.8

Serology greatly aids diagnosis

If syphilis is not treated during the primary stage, it may progress directly into latency or into the second stage of infection. Preventing progression into late findings hinges upon proper diagnostics. While the initial suspicion should begin with history and physical examination, serology is most frequently used to confirm the presence of Treponema pallidum.

It may take as long as 3 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre for serology to become positive.9 During this interval, directly visualizing the pathogen via dark-field microscopy may be useful. Following this interval, nontreponemal serology such as the RPR and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) are frequently used as the initial serology. These rapid tests detect the antibody to cardiolipin and are relatively inexpensive.

Infection is confirmed with specific treponemal tests, including the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs), treponemal enzyme immunoassay, and treponemal particle agglutination tests. These tests are specific for T pallidum and confirm a positive RPR or VDRL. However, specific treponemal tests will not differentiate syphilis from nonvenereal treponematoses such as Bejel, Yaws, and Pinta.10

The common belief is that nontreponemal tests may become negative after successful treatment, and treponemal tests will remain positive indefinitely after successful treatment. However, a study found that 28% of patients treated during primary syphilis and 44% of patients treated during secondary syphilis had positive nontreponemal tests 3 years after treatment.11 In the same study, nearly a quarter of patients treated during primary syphilis no longer had positive FTA-abs 3 years after treatment.11

Penicillin remains the first-line treatment

Once the presence of T pallidum is confirmed, treatment depends on the stage of infection (TABLE). In nonallergic patients, benzathine penicillin G is the standard of care. It should be administered as a single intramuscular (IM) dose of 2.4 million units during primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis12 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Late latent and tertiary syphilis require 3 to 4 weeks of penicillin therapy that is usually achieved with 3 weekly IM injections of 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G12 (SOR: C). Owing largely to the selective permeability of the blood-brain barrier, neurosyphilis requires a larger dose of 3 million to 4 million units intravenous aqueous crystalline benzathine penicillin every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days12 (SOR: C).

Penicillin desensitization should be considered in penicillin-allergic patients, particularly in those who are pregnant or have HIV infection.12

Treatment success can be determined by a 4-fold decline in RPR/VDRL titer over a period of 3 to 6 months after treatment. During the first 24 hours after initial treatment, patients may develop an acute febrile illness known as the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This is largely the result of massive lysis of the pathogen, spilling large quantities of inflammatory cytokines into the bloodstream.13

Table

Syphilis treatment by stage of infection12

| Stage | Time since exposure | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | 10-90 days | Adults Children |

| Secondary | 4-10 weeks | Adults Children |

| Early latent | After primary or secondary stages, <1 year | Adults Children |

| Late latent | >1 year of no symptoms | Adults Children |

| Tertiary | Months to years | Adults See above |

| Neurosyphilis (at any stage) | Any time after infection | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18-24 million units/d, administered as 3-4 million units IV every 4 hours or continuous infusion, for 10-14 days Alternative |

| IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous. | ||

Our patient’s symptoms resolved with penicillin

Given the nebulous history of exposure, we treated the patient as having late latent syphilis (rather than secondary syphilis) and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Our case demonstrates a unique atypical presentation of secondary syphilis. To our knowledge, there is no mention of secondary syphilis mimicking urticaria in the literature. The pruritus that accompanied the lesions was also atypical; however, one study noted 42% of patients experience this symptom in secondary syphilis.14 Fortunately, serological studies confirmed the diagnosis and the patient’s symptoms resolved with standard therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter L. Mattei, MD, 641 Bainbridge Drive, Mullica Hill, NJ 08062; peterlmattei@gmail.com

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of notifiable diseases: United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;58:1-100.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. eds. Dermatology (e-dition). 2nd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008. Available at: http://www.expertconsultbook.com/expertconsult/op/book.do?method=display&type=bookPage&decorator=none&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-2999-1..50002-3&isbn=978-1-4160-2999-1. Accessed March 29, 2010.

3. Fonacier LS, Dreskin SC, Leung DY. Allergic skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 suppl 2):S138-S149.

4. Nguyen NQ. Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:1.-

5. Wechsler HL. Cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 1985;3:79-87.

6. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

7. Galper SL, Smith BD, Wilson LD. Diagnosis and management of mycosis fungoides. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24:491-501.

8. Lansigan F, Foss FM. Current and emerging treatment strategies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Drugs. 2010;70:273-286.

9. Eccleston K, Collins L, Higgins SP. Primary syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:145-151.

10. Koff AB, Rosen T. Nonvenereal treponematoses: yaws, endemic syphilis, and pinta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:519-535.

11. Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, et al. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:1005-1009.

12. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

13. Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2768–2784.

14. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC MAN came into our dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of a pruritic rash that was confined mainly to the trunk. Prior to this visit, he had tried topical corticosteroids and antifungals, but they had not helped.

His trunk showed erythematous macules and reticulate patches with interspersed thin urticarial plaques without scale (FIGURE). Given that the patient had no vesicles or lichenification (which one would expect with eczematous dermatitis) and that the topical steroids did not provide any relief, we performed a biopsy.

FIGURE

Erythematous macules and reticulate patches without scale

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate. On higher magnification, the infiltrate proved to be predominately plasma cells. After further investigation and interview, the patient revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women; his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as “the great imitator.” Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. With the worldwide HIV epidemic, safe sex programs effectively dropped the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States to the lowest in recorded history in the year 2001 at 2.17/100,000.1

More recently, however, this infection appears to be making a comeback. Beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.1

Secondary syphilis usually appears 6 to 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. As the pathogen spreads into the bloodstream, a host of systemic symptoms may occur, including an influenza-like illness of body aches, fever, fatigue, and headache. While the exanthem of secondary syphilis is traditionally described as a nonpruritic, papular eruption involving the trunk, extremities, face, palms, and soles, a number of cutaneous manifestations are possible, including localized alopecia and syphilids.2 In addition, a number of atypical cases are described in the literature, although none has described an urticarial variant, as seen in our case.

The differential included urticaria and lupus erythematosus

The differential diagnosis for our patient included urticaria, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and mycosis fungoides. All of these conditions can be distinguished from secondary syphilis by serology and/or biopsy.

Urticaria is a common dermatologic problem with numerous etiologies. It presents as pruritic raised edematous erythematous wheels that blanch with pressure. Although it affects 15% to 25% of the general population at least once in their lives,3 it may progress to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Isolated acute urticaria usually responds to oral antihistamines.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis that appears as persistent macules that are red to brown and may exhibit telangiectasia.4 Systemic disease may be evaluated using serum tryptase levels. Patients without systemic disease are managed with oral antihistamines.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) often presents precipitously as erythematous maculopapular lesions that may coalesce into annular or papulosquamous plaques.5 It has a predilection for sun-exposed areas and is more common in women.5 Multiple drugs have been associated with SCLE, including phenytoin, calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.6 Treatment consists of discontinuing the offending drug (if one is identified), avoiding (or protecting against) sun exposure, and using topical corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials.

Mycosis fungoides is a form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that more commonly affects males.7 It begins as erythematous pruritic patches that typically involve the sun-spared areas of the lower abdomen and proximal extremities; it progresses slowly.7 As lesions develop into plaques, they may appear psoriasiform. Treatment depends on the stage of the disease and ranges from topical corticosteroids to systemic radiation and chemotherapy.8

Serology greatly aids diagnosis

If syphilis is not treated during the primary stage, it may progress directly into latency or into the second stage of infection. Preventing progression into late findings hinges upon proper diagnostics. While the initial suspicion should begin with history and physical examination, serology is most frequently used to confirm the presence of Treponema pallidum.

It may take as long as 3 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre for serology to become positive.9 During this interval, directly visualizing the pathogen via dark-field microscopy may be useful. Following this interval, nontreponemal serology such as the RPR and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) are frequently used as the initial serology. These rapid tests detect the antibody to cardiolipin and are relatively inexpensive.

Infection is confirmed with specific treponemal tests, including the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs), treponemal enzyme immunoassay, and treponemal particle agglutination tests. These tests are specific for T pallidum and confirm a positive RPR or VDRL. However, specific treponemal tests will not differentiate syphilis from nonvenereal treponematoses such as Bejel, Yaws, and Pinta.10

The common belief is that nontreponemal tests may become negative after successful treatment, and treponemal tests will remain positive indefinitely after successful treatment. However, a study found that 28% of patients treated during primary syphilis and 44% of patients treated during secondary syphilis had positive nontreponemal tests 3 years after treatment.11 In the same study, nearly a quarter of patients treated during primary syphilis no longer had positive FTA-abs 3 years after treatment.11

Penicillin remains the first-line treatment

Once the presence of T pallidum is confirmed, treatment depends on the stage of infection (TABLE). In nonallergic patients, benzathine penicillin G is the standard of care. It should be administered as a single intramuscular (IM) dose of 2.4 million units during primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis12 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Late latent and tertiary syphilis require 3 to 4 weeks of penicillin therapy that is usually achieved with 3 weekly IM injections of 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G12 (SOR: C). Owing largely to the selective permeability of the blood-brain barrier, neurosyphilis requires a larger dose of 3 million to 4 million units intravenous aqueous crystalline benzathine penicillin every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days12 (SOR: C).

Penicillin desensitization should be considered in penicillin-allergic patients, particularly in those who are pregnant or have HIV infection.12

Treatment success can be determined by a 4-fold decline in RPR/VDRL titer over a period of 3 to 6 months after treatment. During the first 24 hours after initial treatment, patients may develop an acute febrile illness known as the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This is largely the result of massive lysis of the pathogen, spilling large quantities of inflammatory cytokines into the bloodstream.13

Table

Syphilis treatment by stage of infection12

| Stage | Time since exposure | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | 10-90 days | Adults Children |

| Secondary | 4-10 weeks | Adults Children |

| Early latent | After primary or secondary stages, <1 year | Adults Children |

| Late latent | >1 year of no symptoms | Adults Children |

| Tertiary | Months to years | Adults See above |

| Neurosyphilis (at any stage) | Any time after infection | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18-24 million units/d, administered as 3-4 million units IV every 4 hours or continuous infusion, for 10-14 days Alternative |

| IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous. | ||

Our patient’s symptoms resolved with penicillin

Given the nebulous history of exposure, we treated the patient as having late latent syphilis (rather than secondary syphilis) and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Our case demonstrates a unique atypical presentation of secondary syphilis. To our knowledge, there is no mention of secondary syphilis mimicking urticaria in the literature. The pruritus that accompanied the lesions was also atypical; however, one study noted 42% of patients experience this symptom in secondary syphilis.14 Fortunately, serological studies confirmed the diagnosis and the patient’s symptoms resolved with standard therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter L. Mattei, MD, 641 Bainbridge Drive, Mullica Hill, NJ 08062; peterlmattei@gmail.com

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC MAN came into our dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of a pruritic rash that was confined mainly to the trunk. Prior to this visit, he had tried topical corticosteroids and antifungals, but they had not helped.

His trunk showed erythematous macules and reticulate patches with interspersed thin urticarial plaques without scale (FIGURE). Given that the patient had no vesicles or lichenification (which one would expect with eczematous dermatitis) and that the topical steroids did not provide any relief, we performed a biopsy.

FIGURE

Erythematous macules and reticulate patches without scale

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate. On higher magnification, the infiltrate proved to be predominately plasma cells. After further investigation and interview, the patient revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women; his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as “the great imitator.” Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. With the worldwide HIV epidemic, safe sex programs effectively dropped the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States to the lowest in recorded history in the year 2001 at 2.17/100,000.1

More recently, however, this infection appears to be making a comeback. Beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.1

Secondary syphilis usually appears 6 to 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. As the pathogen spreads into the bloodstream, a host of systemic symptoms may occur, including an influenza-like illness of body aches, fever, fatigue, and headache. While the exanthem of secondary syphilis is traditionally described as a nonpruritic, papular eruption involving the trunk, extremities, face, palms, and soles, a number of cutaneous manifestations are possible, including localized alopecia and syphilids.2 In addition, a number of atypical cases are described in the literature, although none has described an urticarial variant, as seen in our case.

The differential included urticaria and lupus erythematosus

The differential diagnosis for our patient included urticaria, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and mycosis fungoides. All of these conditions can be distinguished from secondary syphilis by serology and/or biopsy.

Urticaria is a common dermatologic problem with numerous etiologies. It presents as pruritic raised edematous erythematous wheels that blanch with pressure. Although it affects 15% to 25% of the general population at least once in their lives,3 it may progress to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Isolated acute urticaria usually responds to oral antihistamines.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis that appears as persistent macules that are red to brown and may exhibit telangiectasia.4 Systemic disease may be evaluated using serum tryptase levels. Patients without systemic disease are managed with oral antihistamines.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) often presents precipitously as erythematous maculopapular lesions that may coalesce into annular or papulosquamous plaques.5 It has a predilection for sun-exposed areas and is more common in women.5 Multiple drugs have been associated with SCLE, including phenytoin, calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.6 Treatment consists of discontinuing the offending drug (if one is identified), avoiding (or protecting against) sun exposure, and using topical corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials.

Mycosis fungoides is a form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that more commonly affects males.7 It begins as erythematous pruritic patches that typically involve the sun-spared areas of the lower abdomen and proximal extremities; it progresses slowly.7 As lesions develop into plaques, they may appear psoriasiform. Treatment depends on the stage of the disease and ranges from topical corticosteroids to systemic radiation and chemotherapy.8

Serology greatly aids diagnosis

If syphilis is not treated during the primary stage, it may progress directly into latency or into the second stage of infection. Preventing progression into late findings hinges upon proper diagnostics. While the initial suspicion should begin with history and physical examination, serology is most frequently used to confirm the presence of Treponema pallidum.

It may take as long as 3 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre for serology to become positive.9 During this interval, directly visualizing the pathogen via dark-field microscopy may be useful. Following this interval, nontreponemal serology such as the RPR and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) are frequently used as the initial serology. These rapid tests detect the antibody to cardiolipin and are relatively inexpensive.

Infection is confirmed with specific treponemal tests, including the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs), treponemal enzyme immunoassay, and treponemal particle agglutination tests. These tests are specific for T pallidum and confirm a positive RPR or VDRL. However, specific treponemal tests will not differentiate syphilis from nonvenereal treponematoses such as Bejel, Yaws, and Pinta.10

The common belief is that nontreponemal tests may become negative after successful treatment, and treponemal tests will remain positive indefinitely after successful treatment. However, a study found that 28% of patients treated during primary syphilis and 44% of patients treated during secondary syphilis had positive nontreponemal tests 3 years after treatment.11 In the same study, nearly a quarter of patients treated during primary syphilis no longer had positive FTA-abs 3 years after treatment.11

Penicillin remains the first-line treatment