User login

Pruritic rash on trunk

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC MAN came into our dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of a pruritic rash that was confined mainly to the trunk. Prior to this visit, he had tried topical corticosteroids and antifungals, but they had not helped.

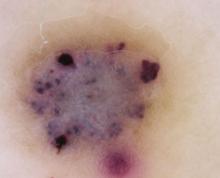

His trunk showed erythematous macules and reticulate patches with interspersed thin urticarial plaques without scale (FIGURE). Given that the patient had no vesicles or lichenification (which one would expect with eczematous dermatitis) and that the topical steroids did not provide any relief, we performed a biopsy.

FIGURE

Erythematous macules and reticulate patches without scale

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate. On higher magnification, the infiltrate proved to be predominately plasma cells. After further investigation and interview, the patient revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women; his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as “the great imitator.” Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. With the worldwide HIV epidemic, safe sex programs effectively dropped the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States to the lowest in recorded history in the year 2001 at 2.17/100,000.1

More recently, however, this infection appears to be making a comeback. Beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.1

Secondary syphilis usually appears 6 to 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. As the pathogen spreads into the bloodstream, a host of systemic symptoms may occur, including an influenza-like illness of body aches, fever, fatigue, and headache. While the exanthem of secondary syphilis is traditionally described as a nonpruritic, papular eruption involving the trunk, extremities, face, palms, and soles, a number of cutaneous manifestations are possible, including localized alopecia and syphilids.2 In addition, a number of atypical cases are described in the literature, although none has described an urticarial variant, as seen in our case.

The differential included urticaria and lupus erythematosus

The differential diagnosis for our patient included urticaria, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and mycosis fungoides. All of these conditions can be distinguished from secondary syphilis by serology and/or biopsy.

Urticaria is a common dermatologic problem with numerous etiologies. It presents as pruritic raised edematous erythematous wheels that blanch with pressure. Although it affects 15% to 25% of the general population at least once in their lives,3 it may progress to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Isolated acute urticaria usually responds to oral antihistamines.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis that appears as persistent macules that are red to brown and may exhibit telangiectasia.4 Systemic disease may be evaluated using serum tryptase levels. Patients without systemic disease are managed with oral antihistamines.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) often presents precipitously as erythematous maculopapular lesions that may coalesce into annular or papulosquamous plaques.5 It has a predilection for sun-exposed areas and is more common in women.5 Multiple drugs have been associated with SCLE, including phenytoin, calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.6 Treatment consists of discontinuing the offending drug (if one is identified), avoiding (or protecting against) sun exposure, and using topical corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials.

Mycosis fungoides is a form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that more commonly affects males.7 It begins as erythematous pruritic patches that typically involve the sun-spared areas of the lower abdomen and proximal extremities; it progresses slowly.7 As lesions develop into plaques, they may appear psoriasiform. Treatment depends on the stage of the disease and ranges from topical corticosteroids to systemic radiation and chemotherapy.8

Serology greatly aids diagnosis

If syphilis is not treated during the primary stage, it may progress directly into latency or into the second stage of infection. Preventing progression into late findings hinges upon proper diagnostics. While the initial suspicion should begin with history and physical examination, serology is most frequently used to confirm the presence of Treponema pallidum.

It may take as long as 3 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre for serology to become positive.9 During this interval, directly visualizing the pathogen via dark-field microscopy may be useful. Following this interval, nontreponemal serology such as the RPR and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) are frequently used as the initial serology. These rapid tests detect the antibody to cardiolipin and are relatively inexpensive.

Infection is confirmed with specific treponemal tests, including the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs), treponemal enzyme immunoassay, and treponemal particle agglutination tests. These tests are specific for T pallidum and confirm a positive RPR or VDRL. However, specific treponemal tests will not differentiate syphilis from nonvenereal treponematoses such as Bejel, Yaws, and Pinta.10

The common belief is that nontreponemal tests may become negative after successful treatment, and treponemal tests will remain positive indefinitely after successful treatment. However, a study found that 28% of patients treated during primary syphilis and 44% of patients treated during secondary syphilis had positive nontreponemal tests 3 years after treatment.11 In the same study, nearly a quarter of patients treated during primary syphilis no longer had positive FTA-abs 3 years after treatment.11

Penicillin remains the first-line treatment

Once the presence of T pallidum is confirmed, treatment depends on the stage of infection (TABLE). In nonallergic patients, benzathine penicillin G is the standard of care. It should be administered as a single intramuscular (IM) dose of 2.4 million units during primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis12 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Late latent and tertiary syphilis require 3 to 4 weeks of penicillin therapy that is usually achieved with 3 weekly IM injections of 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G12 (SOR: C). Owing largely to the selective permeability of the blood-brain barrier, neurosyphilis requires a larger dose of 3 million to 4 million units intravenous aqueous crystalline benzathine penicillin every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days12 (SOR: C).

Penicillin desensitization should be considered in penicillin-allergic patients, particularly in those who are pregnant or have HIV infection.12

Treatment success can be determined by a 4-fold decline in RPR/VDRL titer over a period of 3 to 6 months after treatment. During the first 24 hours after initial treatment, patients may develop an acute febrile illness known as the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This is largely the result of massive lysis of the pathogen, spilling large quantities of inflammatory cytokines into the bloodstream.13

Table

Syphilis treatment by stage of infection12

| Stage | Time since exposure | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | 10-90 days | Adults Children |

| Secondary | 4-10 weeks | Adults Children |

| Early latent | After primary or secondary stages, <1 year | Adults Children |

| Late latent | >1 year of no symptoms | Adults Children |

| Tertiary | Months to years | Adults See above |

| Neurosyphilis (at any stage) | Any time after infection | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18-24 million units/d, administered as 3-4 million units IV every 4 hours or continuous infusion, for 10-14 days Alternative |

| IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous. | ||

Our patient’s symptoms resolved with penicillin

Given the nebulous history of exposure, we treated the patient as having late latent syphilis (rather than secondary syphilis) and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Our case demonstrates a unique atypical presentation of secondary syphilis. To our knowledge, there is no mention of secondary syphilis mimicking urticaria in the literature. The pruritus that accompanied the lesions was also atypical; however, one study noted 42% of patients experience this symptom in secondary syphilis.14 Fortunately, serological studies confirmed the diagnosis and the patient’s symptoms resolved with standard therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter L. Mattei, MD, 641 Bainbridge Drive, Mullica Hill, NJ 08062; peterlmattei@gmail.com

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of notifiable diseases: United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;58:1-100.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. eds. Dermatology (e-dition). 2nd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008. Available at: http://www.expertconsultbook.com/expertconsult/op/book.do?method=display&type=bookPage&decorator=none&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-2999-1..50002-3&isbn=978-1-4160-2999-1. Accessed March 29, 2010.

3. Fonacier LS, Dreskin SC, Leung DY. Allergic skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 suppl 2):S138-S149.

4. Nguyen NQ. Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:1.-

5. Wechsler HL. Cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 1985;3:79-87.

6. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

7. Galper SL, Smith BD, Wilson LD. Diagnosis and management of mycosis fungoides. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24:491-501.

8. Lansigan F, Foss FM. Current and emerging treatment strategies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Drugs. 2010;70:273-286.

9. Eccleston K, Collins L, Higgins SP. Primary syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:145-151.

10. Koff AB, Rosen T. Nonvenereal treponematoses: yaws, endemic syphilis, and pinta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:519-535.

11. Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, et al. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:1005-1009.

12. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

13. Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2768–2784.

14. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC MAN came into our dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of a pruritic rash that was confined mainly to the trunk. Prior to this visit, he had tried topical corticosteroids and antifungals, but they had not helped.

His trunk showed erythematous macules and reticulate patches with interspersed thin urticarial plaques without scale (FIGURE). Given that the patient had no vesicles or lichenification (which one would expect with eczematous dermatitis) and that the topical steroids did not provide any relief, we performed a biopsy.

FIGURE

Erythematous macules and reticulate patches without scale

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate. On higher magnification, the infiltrate proved to be predominately plasma cells. After further investigation and interview, the patient revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women; his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as “the great imitator.” Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. With the worldwide HIV epidemic, safe sex programs effectively dropped the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States to the lowest in recorded history in the year 2001 at 2.17/100,000.1

More recently, however, this infection appears to be making a comeback. Beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.1

Secondary syphilis usually appears 6 to 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. As the pathogen spreads into the bloodstream, a host of systemic symptoms may occur, including an influenza-like illness of body aches, fever, fatigue, and headache. While the exanthem of secondary syphilis is traditionally described as a nonpruritic, papular eruption involving the trunk, extremities, face, palms, and soles, a number of cutaneous manifestations are possible, including localized alopecia and syphilids.2 In addition, a number of atypical cases are described in the literature, although none has described an urticarial variant, as seen in our case.

The differential included urticaria and lupus erythematosus

The differential diagnosis for our patient included urticaria, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and mycosis fungoides. All of these conditions can be distinguished from secondary syphilis by serology and/or biopsy.

Urticaria is a common dermatologic problem with numerous etiologies. It presents as pruritic raised edematous erythematous wheels that blanch with pressure. Although it affects 15% to 25% of the general population at least once in their lives,3 it may progress to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Isolated acute urticaria usually responds to oral antihistamines.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis that appears as persistent macules that are red to brown and may exhibit telangiectasia.4 Systemic disease may be evaluated using serum tryptase levels. Patients without systemic disease are managed with oral antihistamines.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) often presents precipitously as erythematous maculopapular lesions that may coalesce into annular or papulosquamous plaques.5 It has a predilection for sun-exposed areas and is more common in women.5 Multiple drugs have been associated with SCLE, including phenytoin, calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.6 Treatment consists of discontinuing the offending drug (if one is identified), avoiding (or protecting against) sun exposure, and using topical corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials.

Mycosis fungoides is a form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that more commonly affects males.7 It begins as erythematous pruritic patches that typically involve the sun-spared areas of the lower abdomen and proximal extremities; it progresses slowly.7 As lesions develop into plaques, they may appear psoriasiform. Treatment depends on the stage of the disease and ranges from topical corticosteroids to systemic radiation and chemotherapy.8

Serology greatly aids diagnosis

If syphilis is not treated during the primary stage, it may progress directly into latency or into the second stage of infection. Preventing progression into late findings hinges upon proper diagnostics. While the initial suspicion should begin with history and physical examination, serology is most frequently used to confirm the presence of Treponema pallidum.

It may take as long as 3 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre for serology to become positive.9 During this interval, directly visualizing the pathogen via dark-field microscopy may be useful. Following this interval, nontreponemal serology such as the RPR and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) are frequently used as the initial serology. These rapid tests detect the antibody to cardiolipin and are relatively inexpensive.

Infection is confirmed with specific treponemal tests, including the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs), treponemal enzyme immunoassay, and treponemal particle agglutination tests. These tests are specific for T pallidum and confirm a positive RPR or VDRL. However, specific treponemal tests will not differentiate syphilis from nonvenereal treponematoses such as Bejel, Yaws, and Pinta.10

The common belief is that nontreponemal tests may become negative after successful treatment, and treponemal tests will remain positive indefinitely after successful treatment. However, a study found that 28% of patients treated during primary syphilis and 44% of patients treated during secondary syphilis had positive nontreponemal tests 3 years after treatment.11 In the same study, nearly a quarter of patients treated during primary syphilis no longer had positive FTA-abs 3 years after treatment.11

Penicillin remains the first-line treatment

Once the presence of T pallidum is confirmed, treatment depends on the stage of infection (TABLE). In nonallergic patients, benzathine penicillin G is the standard of care. It should be administered as a single intramuscular (IM) dose of 2.4 million units during primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis12 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Late latent and tertiary syphilis require 3 to 4 weeks of penicillin therapy that is usually achieved with 3 weekly IM injections of 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G12 (SOR: C). Owing largely to the selective permeability of the blood-brain barrier, neurosyphilis requires a larger dose of 3 million to 4 million units intravenous aqueous crystalline benzathine penicillin every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days12 (SOR: C).

Penicillin desensitization should be considered in penicillin-allergic patients, particularly in those who are pregnant or have HIV infection.12

Treatment success can be determined by a 4-fold decline in RPR/VDRL titer over a period of 3 to 6 months after treatment. During the first 24 hours after initial treatment, patients may develop an acute febrile illness known as the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This is largely the result of massive lysis of the pathogen, spilling large quantities of inflammatory cytokines into the bloodstream.13

Table

Syphilis treatment by stage of infection12

| Stage | Time since exposure | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | 10-90 days | Adults Children |

| Secondary | 4-10 weeks | Adults Children |

| Early latent | After primary or secondary stages, <1 year | Adults Children |

| Late latent | >1 year of no symptoms | Adults Children |

| Tertiary | Months to years | Adults See above |

| Neurosyphilis (at any stage) | Any time after infection | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18-24 million units/d, administered as 3-4 million units IV every 4 hours or continuous infusion, for 10-14 days Alternative |

| IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous. | ||

Our patient’s symptoms resolved with penicillin

Given the nebulous history of exposure, we treated the patient as having late latent syphilis (rather than secondary syphilis) and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Our case demonstrates a unique atypical presentation of secondary syphilis. To our knowledge, there is no mention of secondary syphilis mimicking urticaria in the literature. The pruritus that accompanied the lesions was also atypical; however, one study noted 42% of patients experience this symptom in secondary syphilis.14 Fortunately, serological studies confirmed the diagnosis and the patient’s symptoms resolved with standard therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter L. Mattei, MD, 641 Bainbridge Drive, Mullica Hill, NJ 08062; peterlmattei@gmail.com

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC MAN came into our dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of a pruritic rash that was confined mainly to the trunk. Prior to this visit, he had tried topical corticosteroids and antifungals, but they had not helped.

His trunk showed erythematous macules and reticulate patches with interspersed thin urticarial plaques without scale (FIGURE). Given that the patient had no vesicles or lichenification (which one would expect with eczematous dermatitis) and that the topical steroids did not provide any relief, we performed a biopsy.

FIGURE

Erythematous macules and reticulate patches without scale

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate. On higher magnification, the infiltrate proved to be predominately plasma cells. After further investigation and interview, the patient revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women; his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as “the great imitator.” Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. With the worldwide HIV epidemic, safe sex programs effectively dropped the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States to the lowest in recorded history in the year 2001 at 2.17/100,000.1

More recently, however, this infection appears to be making a comeback. Beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.1

Secondary syphilis usually appears 6 to 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre. As the pathogen spreads into the bloodstream, a host of systemic symptoms may occur, including an influenza-like illness of body aches, fever, fatigue, and headache. While the exanthem of secondary syphilis is traditionally described as a nonpruritic, papular eruption involving the trunk, extremities, face, palms, and soles, a number of cutaneous manifestations are possible, including localized alopecia and syphilids.2 In addition, a number of atypical cases are described in the literature, although none has described an urticarial variant, as seen in our case.

The differential included urticaria and lupus erythematosus

The differential diagnosis for our patient included urticaria, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and mycosis fungoides. All of these conditions can be distinguished from secondary syphilis by serology and/or biopsy.

Urticaria is a common dermatologic problem with numerous etiologies. It presents as pruritic raised edematous erythematous wheels that blanch with pressure. Although it affects 15% to 25% of the general population at least once in their lives,3 it may progress to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Isolated acute urticaria usually responds to oral antihistamines.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis that appears as persistent macules that are red to brown and may exhibit telangiectasia.4 Systemic disease may be evaluated using serum tryptase levels. Patients without systemic disease are managed with oral antihistamines.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) often presents precipitously as erythematous maculopapular lesions that may coalesce into annular or papulosquamous plaques.5 It has a predilection for sun-exposed areas and is more common in women.5 Multiple drugs have been associated with SCLE, including phenytoin, calcium channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.6 Treatment consists of discontinuing the offending drug (if one is identified), avoiding (or protecting against) sun exposure, and using topical corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, and/or antimalarials.

Mycosis fungoides is a form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that more commonly affects males.7 It begins as erythematous pruritic patches that typically involve the sun-spared areas of the lower abdomen and proximal extremities; it progresses slowly.7 As lesions develop into plaques, they may appear psoriasiform. Treatment depends on the stage of the disease and ranges from topical corticosteroids to systemic radiation and chemotherapy.8

Serology greatly aids diagnosis

If syphilis is not treated during the primary stage, it may progress directly into latency or into the second stage of infection. Preventing progression into late findings hinges upon proper diagnostics. While the initial suspicion should begin with history and physical examination, serology is most frequently used to confirm the presence of Treponema pallidum.

It may take as long as 3 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre for serology to become positive.9 During this interval, directly visualizing the pathogen via dark-field microscopy may be useful. Following this interval, nontreponemal serology such as the RPR and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) are frequently used as the initial serology. These rapid tests detect the antibody to cardiolipin and are relatively inexpensive.

Infection is confirmed with specific treponemal tests, including the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs), treponemal enzyme immunoassay, and treponemal particle agglutination tests. These tests are specific for T pallidum and confirm a positive RPR or VDRL. However, specific treponemal tests will not differentiate syphilis from nonvenereal treponematoses such as Bejel, Yaws, and Pinta.10

The common belief is that nontreponemal tests may become negative after successful treatment, and treponemal tests will remain positive indefinitely after successful treatment. However, a study found that 28% of patients treated during primary syphilis and 44% of patients treated during secondary syphilis had positive nontreponemal tests 3 years after treatment.11 In the same study, nearly a quarter of patients treated during primary syphilis no longer had positive FTA-abs 3 years after treatment.11

Penicillin remains the first-line treatment

Once the presence of T pallidum is confirmed, treatment depends on the stage of infection (TABLE). In nonallergic patients, benzathine penicillin G is the standard of care. It should be administered as a single intramuscular (IM) dose of 2.4 million units during primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis12 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Late latent and tertiary syphilis require 3 to 4 weeks of penicillin therapy that is usually achieved with 3 weekly IM injections of 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G12 (SOR: C). Owing largely to the selective permeability of the blood-brain barrier, neurosyphilis requires a larger dose of 3 million to 4 million units intravenous aqueous crystalline benzathine penicillin every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days12 (SOR: C).

Penicillin desensitization should be considered in penicillin-allergic patients, particularly in those who are pregnant or have HIV infection.12

Treatment success can be determined by a 4-fold decline in RPR/VDRL titer over a period of 3 to 6 months after treatment. During the first 24 hours after initial treatment, patients may develop an acute febrile illness known as the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This is largely the result of massive lysis of the pathogen, spilling large quantities of inflammatory cytokines into the bloodstream.13

Table

Syphilis treatment by stage of infection12

| Stage | Time since exposure | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | 10-90 days | Adults Children |

| Secondary | 4-10 weeks | Adults Children |

| Early latent | After primary or secondary stages, <1 year | Adults Children |

| Late latent | >1 year of no symptoms | Adults Children |

| Tertiary | Months to years | Adults See above |

| Neurosyphilis (at any stage) | Any time after infection | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18-24 million units/d, administered as 3-4 million units IV every 4 hours or continuous infusion, for 10-14 days Alternative |

| IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous. | ||

Our patient’s symptoms resolved with penicillin

Given the nebulous history of exposure, we treated the patient as having late latent syphilis (rather than secondary syphilis) and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Our case demonstrates a unique atypical presentation of secondary syphilis. To our knowledge, there is no mention of secondary syphilis mimicking urticaria in the literature. The pruritus that accompanied the lesions was also atypical; however, one study noted 42% of patients experience this symptom in secondary syphilis.14 Fortunately, serological studies confirmed the diagnosis and the patient’s symptoms resolved with standard therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter L. Mattei, MD, 641 Bainbridge Drive, Mullica Hill, NJ 08062; peterlmattei@gmail.com

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of notifiable diseases: United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;58:1-100.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. eds. Dermatology (e-dition). 2nd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008. Available at: http://www.expertconsultbook.com/expertconsult/op/book.do?method=display&type=bookPage&decorator=none&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-2999-1..50002-3&isbn=978-1-4160-2999-1. Accessed March 29, 2010.

3. Fonacier LS, Dreskin SC, Leung DY. Allergic skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 suppl 2):S138-S149.

4. Nguyen NQ. Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:1.-

5. Wechsler HL. Cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 1985;3:79-87.

6. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

7. Galper SL, Smith BD, Wilson LD. Diagnosis and management of mycosis fungoides. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24:491-501.

8. Lansigan F, Foss FM. Current and emerging treatment strategies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Drugs. 2010;70:273-286.

9. Eccleston K, Collins L, Higgins SP. Primary syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:145-151.

10. Koff AB, Rosen T. Nonvenereal treponematoses: yaws, endemic syphilis, and pinta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:519-535.

11. Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, et al. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:1005-1009.

12. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

13. Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2768–2784.

14. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of notifiable diseases: United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;58:1-100.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. eds. Dermatology (e-dition). 2nd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008. Available at: http://www.expertconsultbook.com/expertconsult/op/book.do?method=display&type=bookPage&decorator=none&eid=4-u1.0-B978-1-4160-2999-1..50002-3&isbn=978-1-4160-2999-1. Accessed March 29, 2010.

3. Fonacier LS, Dreskin SC, Leung DY. Allergic skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 suppl 2):S138-S149.

4. Nguyen NQ. Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:1.-

5. Wechsler HL. Cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 1985;3:79-87.

6. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

7. Galper SL, Smith BD, Wilson LD. Diagnosis and management of mycosis fungoides. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24:491-501.

8. Lansigan F, Foss FM. Current and emerging treatment strategies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Drugs. 2010;70:273-286.

9. Eccleston K, Collins L, Higgins SP. Primary syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:145-151.

10. Koff AB, Rosen T. Nonvenereal treponematoses: yaws, endemic syphilis, and pinta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:519-535.

11. Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, et al. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:1005-1009.

12. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

13. Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:2768–2784.

14. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164.

Verrucous papule on thigh

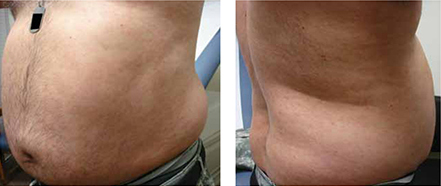

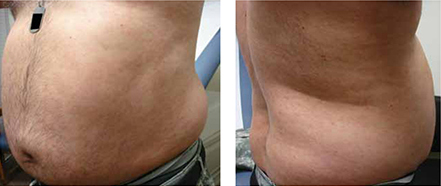

A 21-year-old man came into our medical center to have a lesion on his thigh examined. He said the lesion developed a few months earlier at the site of minimal trauma. He noted that, over the previous few months, the lesion had progressively darkened and it bled sporadically. On examination, we noted a solitary 7.5-mm firm, blue-black verrucous papule over the right medial thigh (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). There were no other lesions.

The patient indicated that he had gotten sunburned many times in the past. He also said that he had an aunt who’d had a melanoma.

FIGURE 1

A lesion that bled sporadically

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Angiokeratoma

An angiokeratoma is a benign pink-red to blue-black variably sized papule or plaque that is typically 2 to 10 mm in diameter.1 Angiokeratomas are composed of a series of subepidermal dilated capillaries that have a characteristic hyperkeratotic surface and bleed easily.2 These lesions are rare, with a prevalence estimated to be 0.16% in the general population.3

The pathogenesis of angiokeratoma formation is unclear; however, multiple theories exist. The development of these lesions may be related to repeated trauma or friction at a particular site.4 Alternatively, increased venous blood pressure or primary degeneration of vascular elastic tissue could explain their development.5 While their cause is unclear, the initial event in the development of an angiokeratoma is believed to be the development of a vascular ectasia within the papillary dermis. The epidermal reaction appears to be a secondary phenomenon due to increased proliferative capacity on the surface of the vessels.5

The most common form—as seen in this case—is the solitary or sporadic angiokeratoma. It comprises 70% to 83% of all cases of angiokeratomas3 and usually develops on the lower extremities. Angiokeratomas typically arise during the first 2 decades of life,6 and are more common in men.3 Other types of angiokeratomas include angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry’s disease).7,8

Angiokeratoma of Mibelli is characterized by pink to dark red papules or verrucoid nodules that occur most commonly in men7 and involve the bony prominences, such as the elbows.

Fordyce lesions involve the scrotum or vulva and are usually numerous and related to conditions with elevated venous pressure.

Angiokeratoma circumscriptum usually present as papules that commonly coalesce to form plaques.

Fabry’s disease, or angiokeratoma corporis diffusum, is an X-linked recessive disease related to a deficiency in alpha-galactosidase A. This leads to multiple, variably sized angiokeratomas occurring in childhood that are concentrated between the umbilicus and the knees. This disease invariably leads to involvement of other organs, which may result in renal failure, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accidents.1,7

A mimicker of melanoma

An angiokeratoma is an uncommon, though important, mimicker of melanoma. (For more on other lesions that can be confused with melanoma, see “Nonmelanocytic melanoma mimickers”.)

Melanoma is the most aggressive and potentially life-threatening neoplasm in the differential diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. Risk factors for melanoma include increasing age, fair skin and hair color, tendency for freckling, number of moles (5 large or >50 small nevi doubles the risk of melanoma), a personal or first-degree family history of melanoma, and a history of intermittent sunburns.9-12

A number of nonmelanocytic lesions can be confused with melanoma. They include the following:

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are a type of keratinocytic neoplasm that typically develops on the sun-exposed skin of the elderly. An AK is typically 3 to 10 mm in size, pink to red in color, and has scaling secondary to local hyperkeratosis. If these lesions are left untreated, they can develop into squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) at a rate of 0.24% annually.15,16 Thus, AKs are more often a concern for SCC than for melanoma. However, the pigmented variant of an AK can clinically and histologically raise concern for melanoma due to its pigmentation and microscopic evidence of melanin within keratinocytes and macrophages.15 If it is not possible to differentiate an AK from melanoma clinically or histologically, immunohistochemistry is often required to make the final diagnosis. For example, immunohistochemical staining with S-100 can be used to identify epidermal melanocytes and distinguish them from atypical keratinocytes.17

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer.18 While most BCCs are amelanocytic, 7% of BCCs are pigmented and present as irregularly pigmented nodules with irregular telangiectatic vessels on their surface. The center of a BCC may be depressed or ulcerated and may easily crust or bleed. Definitive diagnosis may be made histologically. A BCC typically consists of columns of basaloid cells with atypical nuclei, sparse cytoplasm, and peripheral cellular palisading.19 BCCs are easily differentiated from melanoma using immunohistochemistry, as they are negative for traditional melanocytic markers.17

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are among the most common skin lesions and represent a benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes. The appearance of an SK can vary from a smooth peppered appearance to a rough surface that may be irregularly pigmented, dry, and fissured. Given their range of presentation, it is common for SKs to be biopsied to evaluate for melanoma and occasionally BCC.20

Dermatofibromas (DFs) are common benign skin lesions that typically appear as pink-to brown-colored firm nodules that represent a localized response to skin injury and inflammation. DFs are typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter and are most commonly located on the anterior surface of the thigh. Histologic analysis of a DF reveals an acanthotic epidermis with a proliferation of spindle cells in the mid and lower dermis, with capillaries dispersed throughout. A common finding in DFs is the trapping of collagen within the spindle cell at the periphery of the lesion.21

How to diagnose angiokeratoma

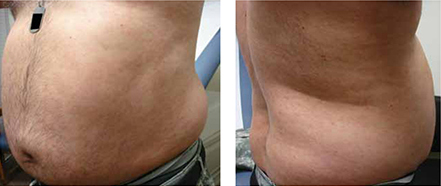

The clinical presentation typically suffices in making the diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. If dermoscopy is performed, the characteristic findings include the presence of scale and purple lacunae13 (FIGURE 2). However, when there is suspicion of melanoma or the clinical diagnosis is in doubt, the entire lesion should be removed (with narrow margins) in order to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Histological findings consist of dilated subepidermal vessels associated with epidermal hyperkeratosis.3

FIGURE 2

A view from the dermatoscope

No need to treat, unless there are cosmetic concerns

If the diagnosis is straightforward and a biopsy is not needed, no treatment is necessary because simple angiokeratomas are benign entities. However, treatment may be considered for cosmetic purposes, or to prevent bothersome bleeding. Angiokeratomas may be removed via shave or standard excision, electrodessication and curettage, or destroyed with a laser. For Fabry’s disease, in which numerous angiokeratomas pose a cosmetic concern, laser therapy, including the use of an argon, copper, Nd:Yag, KTP 532-nm, or Candela V-beam laser, is preferred.14

In our patient’s case, we performed a 2-mm punch biopsy, which revealed that the lesion was an angiokeratoma. It was subsequently removed by shave biopsy with clear margins.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/SG05D/ Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; tbeachkofsky@yahoo.com

1. Karen JK, Hale EK, Ma L. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2005;11:8. Available at: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/114/NYU/NYUtexts/0419054.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

2. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

3. Zaballos P, Dauft C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

4. Kim JH, Nam TS, Kim SH. Solitary angiokeratoma developed in one area of lymphangioma circumscriptum. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:169-170.

5. Sion-Vardy N, Manor E, Puterman M, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma of the tongue. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:12-14.

6. Vascular tumors and malformations In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Dinulos JG, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004:486–487.

7. Leis-Dosil VM, Alijo-Serrano F, Aviles-Izquierdo JA, et al. Angiokeratoma of the glans penis: clinical, histopathological and dermoscopic correlation. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2007;13:19. Available from: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/132/case_presentations/angiokeratoma/dosil.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

8. Erkek E, Basar MM, Bagci Y, et al. Fordyce angiokeratomas as clues to local venous hypertension. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1325-1326.

9. Rager EL, Bridgeford EP, Ollila DW. Cutaneous melanoma: update on prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:269-276.

10. Chudnovsky Y, Khavari PA, Adams AE. Melanoma genetics and the development of rational therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:813-824.

11. Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:163-172.

12. Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. JAMA. 2004;292:2771-2776.

13. Johr RH, Soyer P, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:130.

14. Enjolras O. Vascular malformations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby; 2003: 1621–1622.

15. Peris K, Micantonio T, Piccolo D, et al. Dermoscopic features of actinic keratosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:970-976.

16. McIntyre WJ, Downs MR, Bedwell SA. Treatment options for actinic keratosis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:667-671.

17. Kamil ZS, Tong LC, Habeeb AA, et al. Non-melanocytic mimics of melanoma: part 1: intraepidermal mimics. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:120-127.

18. Wong CS, Strange RC, Lear JT. Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ. 2003;327:794-798.

19. Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

20. Braun RP, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Dermoscopic diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:270-272.

21. Agero AL, Taliercio S, Dusza SW, et al. Conventional and polarized dermoscopy features of dermatofibroma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1431-1437.

A 21-year-old man came into our medical center to have a lesion on his thigh examined. He said the lesion developed a few months earlier at the site of minimal trauma. He noted that, over the previous few months, the lesion had progressively darkened and it bled sporadically. On examination, we noted a solitary 7.5-mm firm, blue-black verrucous papule over the right medial thigh (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). There were no other lesions.

The patient indicated that he had gotten sunburned many times in the past. He also said that he had an aunt who’d had a melanoma.

FIGURE 1

A lesion that bled sporadically

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Angiokeratoma

An angiokeratoma is a benign pink-red to blue-black variably sized papule or plaque that is typically 2 to 10 mm in diameter.1 Angiokeratomas are composed of a series of subepidermal dilated capillaries that have a characteristic hyperkeratotic surface and bleed easily.2 These lesions are rare, with a prevalence estimated to be 0.16% in the general population.3

The pathogenesis of angiokeratoma formation is unclear; however, multiple theories exist. The development of these lesions may be related to repeated trauma or friction at a particular site.4 Alternatively, increased venous blood pressure or primary degeneration of vascular elastic tissue could explain their development.5 While their cause is unclear, the initial event in the development of an angiokeratoma is believed to be the development of a vascular ectasia within the papillary dermis. The epidermal reaction appears to be a secondary phenomenon due to increased proliferative capacity on the surface of the vessels.5

The most common form—as seen in this case—is the solitary or sporadic angiokeratoma. It comprises 70% to 83% of all cases of angiokeratomas3 and usually develops on the lower extremities. Angiokeratomas typically arise during the first 2 decades of life,6 and are more common in men.3 Other types of angiokeratomas include angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry’s disease).7,8

Angiokeratoma of Mibelli is characterized by pink to dark red papules or verrucoid nodules that occur most commonly in men7 and involve the bony prominences, such as the elbows.

Fordyce lesions involve the scrotum or vulva and are usually numerous and related to conditions with elevated venous pressure.

Angiokeratoma circumscriptum usually present as papules that commonly coalesce to form plaques.

Fabry’s disease, or angiokeratoma corporis diffusum, is an X-linked recessive disease related to a deficiency in alpha-galactosidase A. This leads to multiple, variably sized angiokeratomas occurring in childhood that are concentrated between the umbilicus and the knees. This disease invariably leads to involvement of other organs, which may result in renal failure, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accidents.1,7

A mimicker of melanoma

An angiokeratoma is an uncommon, though important, mimicker of melanoma. (For more on other lesions that can be confused with melanoma, see “Nonmelanocytic melanoma mimickers”.)

Melanoma is the most aggressive and potentially life-threatening neoplasm in the differential diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. Risk factors for melanoma include increasing age, fair skin and hair color, tendency for freckling, number of moles (5 large or >50 small nevi doubles the risk of melanoma), a personal or first-degree family history of melanoma, and a history of intermittent sunburns.9-12

A number of nonmelanocytic lesions can be confused with melanoma. They include the following:

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are a type of keratinocytic neoplasm that typically develops on the sun-exposed skin of the elderly. An AK is typically 3 to 10 mm in size, pink to red in color, and has scaling secondary to local hyperkeratosis. If these lesions are left untreated, they can develop into squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) at a rate of 0.24% annually.15,16 Thus, AKs are more often a concern for SCC than for melanoma. However, the pigmented variant of an AK can clinically and histologically raise concern for melanoma due to its pigmentation and microscopic evidence of melanin within keratinocytes and macrophages.15 If it is not possible to differentiate an AK from melanoma clinically or histologically, immunohistochemistry is often required to make the final diagnosis. For example, immunohistochemical staining with S-100 can be used to identify epidermal melanocytes and distinguish them from atypical keratinocytes.17

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer.18 While most BCCs are amelanocytic, 7% of BCCs are pigmented and present as irregularly pigmented nodules with irregular telangiectatic vessels on their surface. The center of a BCC may be depressed or ulcerated and may easily crust or bleed. Definitive diagnosis may be made histologically. A BCC typically consists of columns of basaloid cells with atypical nuclei, sparse cytoplasm, and peripheral cellular palisading.19 BCCs are easily differentiated from melanoma using immunohistochemistry, as they are negative for traditional melanocytic markers.17

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are among the most common skin lesions and represent a benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes. The appearance of an SK can vary from a smooth peppered appearance to a rough surface that may be irregularly pigmented, dry, and fissured. Given their range of presentation, it is common for SKs to be biopsied to evaluate for melanoma and occasionally BCC.20

Dermatofibromas (DFs) are common benign skin lesions that typically appear as pink-to brown-colored firm nodules that represent a localized response to skin injury and inflammation. DFs are typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter and are most commonly located on the anterior surface of the thigh. Histologic analysis of a DF reveals an acanthotic epidermis with a proliferation of spindle cells in the mid and lower dermis, with capillaries dispersed throughout. A common finding in DFs is the trapping of collagen within the spindle cell at the periphery of the lesion.21

How to diagnose angiokeratoma

The clinical presentation typically suffices in making the diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. If dermoscopy is performed, the characteristic findings include the presence of scale and purple lacunae13 (FIGURE 2). However, when there is suspicion of melanoma or the clinical diagnosis is in doubt, the entire lesion should be removed (with narrow margins) in order to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Histological findings consist of dilated subepidermal vessels associated with epidermal hyperkeratosis.3

FIGURE 2

A view from the dermatoscope

No need to treat, unless there are cosmetic concerns

If the diagnosis is straightforward and a biopsy is not needed, no treatment is necessary because simple angiokeratomas are benign entities. However, treatment may be considered for cosmetic purposes, or to prevent bothersome bleeding. Angiokeratomas may be removed via shave or standard excision, electrodessication and curettage, or destroyed with a laser. For Fabry’s disease, in which numerous angiokeratomas pose a cosmetic concern, laser therapy, including the use of an argon, copper, Nd:Yag, KTP 532-nm, or Candela V-beam laser, is preferred.14

In our patient’s case, we performed a 2-mm punch biopsy, which revealed that the lesion was an angiokeratoma. It was subsequently removed by shave biopsy with clear margins.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/SG05D/ Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; tbeachkofsky@yahoo.com

A 21-year-old man came into our medical center to have a lesion on his thigh examined. He said the lesion developed a few months earlier at the site of minimal trauma. He noted that, over the previous few months, the lesion had progressively darkened and it bled sporadically. On examination, we noted a solitary 7.5-mm firm, blue-black verrucous papule over the right medial thigh (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). There were no other lesions.

The patient indicated that he had gotten sunburned many times in the past. He also said that he had an aunt who’d had a melanoma.

FIGURE 1

A lesion that bled sporadically

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Angiokeratoma

An angiokeratoma is a benign pink-red to blue-black variably sized papule or plaque that is typically 2 to 10 mm in diameter.1 Angiokeratomas are composed of a series of subepidermal dilated capillaries that have a characteristic hyperkeratotic surface and bleed easily.2 These lesions are rare, with a prevalence estimated to be 0.16% in the general population.3

The pathogenesis of angiokeratoma formation is unclear; however, multiple theories exist. The development of these lesions may be related to repeated trauma or friction at a particular site.4 Alternatively, increased venous blood pressure or primary degeneration of vascular elastic tissue could explain their development.5 While their cause is unclear, the initial event in the development of an angiokeratoma is believed to be the development of a vascular ectasia within the papillary dermis. The epidermal reaction appears to be a secondary phenomenon due to increased proliferative capacity on the surface of the vessels.5

The most common form—as seen in this case—is the solitary or sporadic angiokeratoma. It comprises 70% to 83% of all cases of angiokeratomas3 and usually develops on the lower extremities. Angiokeratomas typically arise during the first 2 decades of life,6 and are more common in men.3 Other types of angiokeratomas include angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry’s disease).7,8

Angiokeratoma of Mibelli is characterized by pink to dark red papules or verrucoid nodules that occur most commonly in men7 and involve the bony prominences, such as the elbows.

Fordyce lesions involve the scrotum or vulva and are usually numerous and related to conditions with elevated venous pressure.

Angiokeratoma circumscriptum usually present as papules that commonly coalesce to form plaques.

Fabry’s disease, or angiokeratoma corporis diffusum, is an X-linked recessive disease related to a deficiency in alpha-galactosidase A. This leads to multiple, variably sized angiokeratomas occurring in childhood that are concentrated between the umbilicus and the knees. This disease invariably leads to involvement of other organs, which may result in renal failure, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accidents.1,7

A mimicker of melanoma

An angiokeratoma is an uncommon, though important, mimicker of melanoma. (For more on other lesions that can be confused with melanoma, see “Nonmelanocytic melanoma mimickers”.)

Melanoma is the most aggressive and potentially life-threatening neoplasm in the differential diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. Risk factors for melanoma include increasing age, fair skin and hair color, tendency for freckling, number of moles (5 large or >50 small nevi doubles the risk of melanoma), a personal or first-degree family history of melanoma, and a history of intermittent sunburns.9-12

A number of nonmelanocytic lesions can be confused with melanoma. They include the following:

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are a type of keratinocytic neoplasm that typically develops on the sun-exposed skin of the elderly. An AK is typically 3 to 10 mm in size, pink to red in color, and has scaling secondary to local hyperkeratosis. If these lesions are left untreated, they can develop into squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) at a rate of 0.24% annually.15,16 Thus, AKs are more often a concern for SCC than for melanoma. However, the pigmented variant of an AK can clinically and histologically raise concern for melanoma due to its pigmentation and microscopic evidence of melanin within keratinocytes and macrophages.15 If it is not possible to differentiate an AK from melanoma clinically or histologically, immunohistochemistry is often required to make the final diagnosis. For example, immunohistochemical staining with S-100 can be used to identify epidermal melanocytes and distinguish them from atypical keratinocytes.17

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer.18 While most BCCs are amelanocytic, 7% of BCCs are pigmented and present as irregularly pigmented nodules with irregular telangiectatic vessels on their surface. The center of a BCC may be depressed or ulcerated and may easily crust or bleed. Definitive diagnosis may be made histologically. A BCC typically consists of columns of basaloid cells with atypical nuclei, sparse cytoplasm, and peripheral cellular palisading.19 BCCs are easily differentiated from melanoma using immunohistochemistry, as they are negative for traditional melanocytic markers.17

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are among the most common skin lesions and represent a benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes. The appearance of an SK can vary from a smooth peppered appearance to a rough surface that may be irregularly pigmented, dry, and fissured. Given their range of presentation, it is common for SKs to be biopsied to evaluate for melanoma and occasionally BCC.20

Dermatofibromas (DFs) are common benign skin lesions that typically appear as pink-to brown-colored firm nodules that represent a localized response to skin injury and inflammation. DFs are typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter and are most commonly located on the anterior surface of the thigh. Histologic analysis of a DF reveals an acanthotic epidermis with a proliferation of spindle cells in the mid and lower dermis, with capillaries dispersed throughout. A common finding in DFs is the trapping of collagen within the spindle cell at the periphery of the lesion.21

How to diagnose angiokeratoma

The clinical presentation typically suffices in making the diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. If dermoscopy is performed, the characteristic findings include the presence of scale and purple lacunae13 (FIGURE 2). However, when there is suspicion of melanoma or the clinical diagnosis is in doubt, the entire lesion should be removed (with narrow margins) in order to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Histological findings consist of dilated subepidermal vessels associated with epidermal hyperkeratosis.3

FIGURE 2

A view from the dermatoscope

No need to treat, unless there are cosmetic concerns

If the diagnosis is straightforward and a biopsy is not needed, no treatment is necessary because simple angiokeratomas are benign entities. However, treatment may be considered for cosmetic purposes, or to prevent bothersome bleeding. Angiokeratomas may be removed via shave or standard excision, electrodessication and curettage, or destroyed with a laser. For Fabry’s disease, in which numerous angiokeratomas pose a cosmetic concern, laser therapy, including the use of an argon, copper, Nd:Yag, KTP 532-nm, or Candela V-beam laser, is preferred.14

In our patient’s case, we performed a 2-mm punch biopsy, which revealed that the lesion was an angiokeratoma. It was subsequently removed by shave biopsy with clear margins.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/SG05D/ Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; tbeachkofsky@yahoo.com

1. Karen JK, Hale EK, Ma L. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2005;11:8. Available at: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/114/NYU/NYUtexts/0419054.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

2. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

3. Zaballos P, Dauft C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

4. Kim JH, Nam TS, Kim SH. Solitary angiokeratoma developed in one area of lymphangioma circumscriptum. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:169-170.

5. Sion-Vardy N, Manor E, Puterman M, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma of the tongue. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:12-14.

6. Vascular tumors and malformations In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Dinulos JG, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004:486–487.

7. Leis-Dosil VM, Alijo-Serrano F, Aviles-Izquierdo JA, et al. Angiokeratoma of the glans penis: clinical, histopathological and dermoscopic correlation. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2007;13:19. Available from: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/132/case_presentations/angiokeratoma/dosil.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

8. Erkek E, Basar MM, Bagci Y, et al. Fordyce angiokeratomas as clues to local venous hypertension. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1325-1326.

9. Rager EL, Bridgeford EP, Ollila DW. Cutaneous melanoma: update on prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:269-276.

10. Chudnovsky Y, Khavari PA, Adams AE. Melanoma genetics and the development of rational therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:813-824.

11. Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:163-172.

12. Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. JAMA. 2004;292:2771-2776.

13. Johr RH, Soyer P, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:130.

14. Enjolras O. Vascular malformations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby; 2003: 1621–1622.

15. Peris K, Micantonio T, Piccolo D, et al. Dermoscopic features of actinic keratosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:970-976.

16. McIntyre WJ, Downs MR, Bedwell SA. Treatment options for actinic keratosis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:667-671.

17. Kamil ZS, Tong LC, Habeeb AA, et al. Non-melanocytic mimics of melanoma: part 1: intraepidermal mimics. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:120-127.

18. Wong CS, Strange RC, Lear JT. Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ. 2003;327:794-798.

19. Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

20. Braun RP, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Dermoscopic diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:270-272.

21. Agero AL, Taliercio S, Dusza SW, et al. Conventional and polarized dermoscopy features of dermatofibroma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1431-1437.

1. Karen JK, Hale EK, Ma L. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2005;11:8. Available at: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/114/NYU/NYUtexts/0419054.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

2. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

3. Zaballos P, Dauft C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

4. Kim JH, Nam TS, Kim SH. Solitary angiokeratoma developed in one area of lymphangioma circumscriptum. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:169-170.

5. Sion-Vardy N, Manor E, Puterman M, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma of the tongue. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:12-14.

6. Vascular tumors and malformations In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Dinulos JG, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004:486–487.

7. Leis-Dosil VM, Alijo-Serrano F, Aviles-Izquierdo JA, et al. Angiokeratoma of the glans penis: clinical, histopathological and dermoscopic correlation. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2007;13:19. Available from: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/132/case_presentations/angiokeratoma/dosil.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

8. Erkek E, Basar MM, Bagci Y, et al. Fordyce angiokeratomas as clues to local venous hypertension. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1325-1326.

9. Rager EL, Bridgeford EP, Ollila DW. Cutaneous melanoma: update on prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:269-276.

10. Chudnovsky Y, Khavari PA, Adams AE. Melanoma genetics and the development of rational therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:813-824.

11. Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:163-172.

12. Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. JAMA. 2004;292:2771-2776.

13. Johr RH, Soyer P, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:130.

14. Enjolras O. Vascular malformations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby; 2003: 1621–1622.

15. Peris K, Micantonio T, Piccolo D, et al. Dermoscopic features of actinic keratosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:970-976.

16. McIntyre WJ, Downs MR, Bedwell SA. Treatment options for actinic keratosis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:667-671.

17. Kamil ZS, Tong LC, Habeeb AA, et al. Non-melanocytic mimics of melanoma: part 1: intraepidermal mimics. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:120-127.

18. Wong CS, Strange RC, Lear JT. Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ. 2003;327:794-798.

19. Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

20. Braun RP, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Dermoscopic diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:270-272.

21. Agero AL, Taliercio S, Dusza SW, et al. Conventional and polarized dermoscopy features of dermatofibroma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1431-1437.