User login

Identifying and preventing IPV: Are clinicians doing enough?

Violence against women remains a global dilemma in need of attention. Physical violence in particular, is the most prevalent type of violence across all genders, races, and nationalities.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says more than 43 million women and 38 million men report experiencing psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime. Meanwhile, 11 million women and 5 million men report enduring sexual or physical violence and intimate partner violence (IPV), and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetimes, according to the CDC.1

Women who have endured this kind of violence might present differently from men. Some studies, for example, show a more significant association between mutual violence, depression, and substance use among women than men.2 Studies on the phenomenon of IPV victims/survivors becoming perpetrators of abuse are limited, but that this happens in some cases.

Having a psychiatric disorder is associated with a higher likelihood of being physically violent with a partner.3,4 One recent study of 250 female psychiatric patients who were married and had no history of drug abuse found that almost 68% reported psychological abuse, 52% reported sexual abuse, 38% social abuse, 37% reported economic abuse, and 25% reported physical abuse.5

Given those statistics and trends, it is incumbent upon clinicians – including those in primary care, psychiatry, and emergency medicine – to learn to quickly identify IPV survivors, and to use available prognostic tools to monitor perpetrators and survivors.

COVID pandemic’s influence

Isolation tied to the COVID-19 pandemic has been linked to increased IPV. A study conducted by researchers at the University of California, Davis, suggested that extra stress experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic caused by income loss, and the inability to pay for housing and food exacerbated the prevalence of IPV early during the pandemic.6

That study, where researchers collected in surveys of nearly 400 adults in the beginning in April 2020 for 10 weeks, showed that more services and communication are needed so that frontline health care and food bank workers, for example, in addition to social workers, doctors, and therapists, can spot the signs and ask clients questions about potential IPV. They could then link survivors to pertinent assistance and resources.

Furthermore, multiple factors probably have played a pivotal role in increasing the prevalence of IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, disruption to usual health and social services as well as diminished access to support systems, such as shelters, and charity helplines negatively affected the reporting of domestic violence.

Long before the pandemic, over the past decade, international and national bodies have played a crucial role in terms of improving the awareness and response to domestic violence.7,8 In addition, several policies have been introduced in countries around the globe emphasizing the need to inquire routinely about domestic violence. Nevertheless, mental health services often fail to adequately address domestic violence in clinical encounters. A systematic review of domestic violence assessment screening performed in a variety of health care settings found that evidence was insufficient to conclude that routine inquiry improved morbidity and mortality among victims of IPV.9 So the question becomes: How can we get our patients to tell us about these experiences so we can intervene?

Gender differences in perpetuating IPV

Several studies have found that abuse can result in various mental illnesses, such as depression, PTSD, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Again, men have a disproportionately higher rate of perpetrating IPV, compared with women. This theory has been a source of debate in the academic community for years, but recent research has confirmed that women do perpetuate violence against their partners to some extent.10,11

Some members of the LGBTQ+ community also report experiencing violence from partners, so as clinicians, we also need to raise our awareness about the existence of violence among same-sex couples. In fact, a team of Italian researchers report more than 50% of gay men and almost 75% of lesbian women reported that they had been psychologically abused by a partner.12 More research into this area is needed.

Our role as health care professionals

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advises that all clinic visits include regular IPV screening.13 But these screenings are all too rare. In fact, a meta-analysis of 19 trials of more than 1,600 participants showed only 9%-40% of doctors routinely test for IPV.14 That research clearly shows how important it is for all clinicians to execute IPV screening. However, numerous challenges toward screening exist, including personal discomfort, limited time during appointments, insufficient resources, and inadequate training.

One ongoing debate revolves around which clinician should screen for IPV. Should the psychiatrist carry out this role – or perhaps the primary care physician, nurse, or social worker? These issues become even more fraught when clinicians worry about offending the patient – especially if the clinician is a male.15

The bottom line is that physicians should inquire about intimate partner violence, because research indicates that women are more likely to reveal abuse when prompted. In addition, during physician appointments, they can use the physician-patient therapeutic connection to conduct a domestic violence evaluation, give resources to victims, and provide ongoing care. Patients who exhibit treatment resistance, persistent pain, depression, sleeplessness, and headaches should prompt psychiatrists to conduct additional investigations into the likelihood of intimate partner violence and domestic abuse.

W also should be attentive when counseling patients about domestic violence when suggesting life-changing events such as pregnancy, employment loss, separation, or divorce. Similar to the recommendations of the USPSTF that all women and men should be screened for IPV, it is suggested that physicians be conscious of facilitating a conversation and not being overtly judgmental while observing body cues. Using the statements such as “we have been hearing a lot of violence in our community lately” could be a segue to introduce the subject.

Asking the question of whether you are being hit rather than being abused has allowed more women to open up more about domestic violence. While physicians are aware that most victims might recant and often go back to their abusers, victims need to be counseled that the abuse might intensify and lead to death.

For women who perpetuate IPV and survivors of IPV, safety is the priority. Physicians should provide safety options and be the facilitators. Studies have shown that fewer victims get the referral to the supporting agencies when IPV is indicated, which puts their safety at risk. In women who commit IPV, clinicians should assess the role of the individual in an IPV disclosure. There are various treatment modalities, whether the violence is performed through self-defense, bidirectionally, or because of aggression.

With the advancement of technology, web-based training on how to ask for IPV, documentation, acknowledgment, and structured referral increase physicians’ confidence when faced with an IPV disclosure than none.16 Treatment modalities should include medication reconciliation and cognitive-behavioral therapy – focusing on emotion regulation.

Using instruments such as the danger assessment tool can help physicians intervene early, reducing the risk of domestic violence and IPV recurrence instead of using clinical assessment alone.17 Physicians should convey empathy, validate victims, and help, especially when abuse is reported.

Also, it is important to evaluate survivors’ safety. Counseling can help people rebuild their self-esteem. Structured referrals for psychiatric help and support services are needed to help survivors on the long road to recovery.

Training all physicians, regardless of specialty, is essential to improve prompt IPV identification and bring awareness to resources available to survivors when IPV is disclosed. Although we described an association between IPV victims becoming possible perpetrators of IPV, more long-term studies are required to show the various processes that influence IPV perpetration rates, especially by survivors.

We would also like international and national regulatory bodies to increase the awareness of IPV and adequately address IPV with special emphasis on how mental health services should assess, identify, and respond to services for people who are survivors and perpetrators of IPV.

Dr. Kumari, Dr. Otite, Dr. Afzal, Dr. Alcera, and Dr. Doumas are affiliated with Hackensack Meridian Health at Ocean Medical Center, Brick, N.J. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2020 Oct 9.

2. Yu R et al. PLOS Med. 16(12):e1002995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002995.

3. Oram S et al. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2014 Dec;23(4):361-76.

4. Munro OE and Sellbom M. Pers Ment Health. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1480.

5. Sahraian A et al. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102062.

6. Nikos-Rose K. “COVID-19 Isolation Linked to Increased Domestic Violence, Researchers Suggest.” 2021 Feb 24. University of California, Davis.

7. World Health Organization. “Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women.” WHO clinical policy guidelines. 2013.

8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. “Domestic violence and abuse: Multi-agency working.” PH50. 2014 Feb 26.

9. Feder GS et al. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):22-37.

10. Gondolf EW. Violence Against Women. 2014 Dec;20(12)1539-46.

11. Hamberger LK and Larsen SE. J Fam Violence. 2015;30(6):699-717.

12. Rollè L et al. Front Psychol. 21 Aug 2018. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506.

13. Paterno MT and Draughon JE. J Midwif Women Health. 2016;61(31):370-5.

14. Kalra N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 May 31;5(5)CD012423.

15. Larsen SE and Hamberger LK. J Fam Viol. 2015;30:1007-30.

16. Kalra N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD012423.

17. Campbell JC et al. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(4):653-74.

Violence against women remains a global dilemma in need of attention. Physical violence in particular, is the most prevalent type of violence across all genders, races, and nationalities.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says more than 43 million women and 38 million men report experiencing psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime. Meanwhile, 11 million women and 5 million men report enduring sexual or physical violence and intimate partner violence (IPV), and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetimes, according to the CDC.1

Women who have endured this kind of violence might present differently from men. Some studies, for example, show a more significant association between mutual violence, depression, and substance use among women than men.2 Studies on the phenomenon of IPV victims/survivors becoming perpetrators of abuse are limited, but that this happens in some cases.

Having a psychiatric disorder is associated with a higher likelihood of being physically violent with a partner.3,4 One recent study of 250 female psychiatric patients who were married and had no history of drug abuse found that almost 68% reported psychological abuse, 52% reported sexual abuse, 38% social abuse, 37% reported economic abuse, and 25% reported physical abuse.5

Given those statistics and trends, it is incumbent upon clinicians – including those in primary care, psychiatry, and emergency medicine – to learn to quickly identify IPV survivors, and to use available prognostic tools to monitor perpetrators and survivors.

COVID pandemic’s influence

Isolation tied to the COVID-19 pandemic has been linked to increased IPV. A study conducted by researchers at the University of California, Davis, suggested that extra stress experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic caused by income loss, and the inability to pay for housing and food exacerbated the prevalence of IPV early during the pandemic.6

That study, where researchers collected in surveys of nearly 400 adults in the beginning in April 2020 for 10 weeks, showed that more services and communication are needed so that frontline health care and food bank workers, for example, in addition to social workers, doctors, and therapists, can spot the signs and ask clients questions about potential IPV. They could then link survivors to pertinent assistance and resources.

Furthermore, multiple factors probably have played a pivotal role in increasing the prevalence of IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, disruption to usual health and social services as well as diminished access to support systems, such as shelters, and charity helplines negatively affected the reporting of domestic violence.

Long before the pandemic, over the past decade, international and national bodies have played a crucial role in terms of improving the awareness and response to domestic violence.7,8 In addition, several policies have been introduced in countries around the globe emphasizing the need to inquire routinely about domestic violence. Nevertheless, mental health services often fail to adequately address domestic violence in clinical encounters. A systematic review of domestic violence assessment screening performed in a variety of health care settings found that evidence was insufficient to conclude that routine inquiry improved morbidity and mortality among victims of IPV.9 So the question becomes: How can we get our patients to tell us about these experiences so we can intervene?

Gender differences in perpetuating IPV

Several studies have found that abuse can result in various mental illnesses, such as depression, PTSD, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Again, men have a disproportionately higher rate of perpetrating IPV, compared with women. This theory has been a source of debate in the academic community for years, but recent research has confirmed that women do perpetuate violence against their partners to some extent.10,11

Some members of the LGBTQ+ community also report experiencing violence from partners, so as clinicians, we also need to raise our awareness about the existence of violence among same-sex couples. In fact, a team of Italian researchers report more than 50% of gay men and almost 75% of lesbian women reported that they had been psychologically abused by a partner.12 More research into this area is needed.

Our role as health care professionals

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advises that all clinic visits include regular IPV screening.13 But these screenings are all too rare. In fact, a meta-analysis of 19 trials of more than 1,600 participants showed only 9%-40% of doctors routinely test for IPV.14 That research clearly shows how important it is for all clinicians to execute IPV screening. However, numerous challenges toward screening exist, including personal discomfort, limited time during appointments, insufficient resources, and inadequate training.

One ongoing debate revolves around which clinician should screen for IPV. Should the psychiatrist carry out this role – or perhaps the primary care physician, nurse, or social worker? These issues become even more fraught when clinicians worry about offending the patient – especially if the clinician is a male.15

The bottom line is that physicians should inquire about intimate partner violence, because research indicates that women are more likely to reveal abuse when prompted. In addition, during physician appointments, they can use the physician-patient therapeutic connection to conduct a domestic violence evaluation, give resources to victims, and provide ongoing care. Patients who exhibit treatment resistance, persistent pain, depression, sleeplessness, and headaches should prompt psychiatrists to conduct additional investigations into the likelihood of intimate partner violence and domestic abuse.

W also should be attentive when counseling patients about domestic violence when suggesting life-changing events such as pregnancy, employment loss, separation, or divorce. Similar to the recommendations of the USPSTF that all women and men should be screened for IPV, it is suggested that physicians be conscious of facilitating a conversation and not being overtly judgmental while observing body cues. Using the statements such as “we have been hearing a lot of violence in our community lately” could be a segue to introduce the subject.

Asking the question of whether you are being hit rather than being abused has allowed more women to open up more about domestic violence. While physicians are aware that most victims might recant and often go back to their abusers, victims need to be counseled that the abuse might intensify and lead to death.

For women who perpetuate IPV and survivors of IPV, safety is the priority. Physicians should provide safety options and be the facilitators. Studies have shown that fewer victims get the referral to the supporting agencies when IPV is indicated, which puts their safety at risk. In women who commit IPV, clinicians should assess the role of the individual in an IPV disclosure. There are various treatment modalities, whether the violence is performed through self-defense, bidirectionally, or because of aggression.

With the advancement of technology, web-based training on how to ask for IPV, documentation, acknowledgment, and structured referral increase physicians’ confidence when faced with an IPV disclosure than none.16 Treatment modalities should include medication reconciliation and cognitive-behavioral therapy – focusing on emotion regulation.

Using instruments such as the danger assessment tool can help physicians intervene early, reducing the risk of domestic violence and IPV recurrence instead of using clinical assessment alone.17 Physicians should convey empathy, validate victims, and help, especially when abuse is reported.

Also, it is important to evaluate survivors’ safety. Counseling can help people rebuild their self-esteem. Structured referrals for psychiatric help and support services are needed to help survivors on the long road to recovery.

Training all physicians, regardless of specialty, is essential to improve prompt IPV identification and bring awareness to resources available to survivors when IPV is disclosed. Although we described an association between IPV victims becoming possible perpetrators of IPV, more long-term studies are required to show the various processes that influence IPV perpetration rates, especially by survivors.

We would also like international and national regulatory bodies to increase the awareness of IPV and adequately address IPV with special emphasis on how mental health services should assess, identify, and respond to services for people who are survivors and perpetrators of IPV.

Dr. Kumari, Dr. Otite, Dr. Afzal, Dr. Alcera, and Dr. Doumas are affiliated with Hackensack Meridian Health at Ocean Medical Center, Brick, N.J. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2020 Oct 9.

2. Yu R et al. PLOS Med. 16(12):e1002995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002995.

3. Oram S et al. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2014 Dec;23(4):361-76.

4. Munro OE and Sellbom M. Pers Ment Health. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1480.

5. Sahraian A et al. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102062.

6. Nikos-Rose K. “COVID-19 Isolation Linked to Increased Domestic Violence, Researchers Suggest.” 2021 Feb 24. University of California, Davis.

7. World Health Organization. “Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women.” WHO clinical policy guidelines. 2013.

8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. “Domestic violence and abuse: Multi-agency working.” PH50. 2014 Feb 26.

9. Feder GS et al. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):22-37.

10. Gondolf EW. Violence Against Women. 2014 Dec;20(12)1539-46.

11. Hamberger LK and Larsen SE. J Fam Violence. 2015;30(6):699-717.

12. Rollè L et al. Front Psychol. 21 Aug 2018. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506.

13. Paterno MT and Draughon JE. J Midwif Women Health. 2016;61(31):370-5.

14. Kalra N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 May 31;5(5)CD012423.

15. Larsen SE and Hamberger LK. J Fam Viol. 2015;30:1007-30.

16. Kalra N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD012423.

17. Campbell JC et al. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(4):653-74.

Violence against women remains a global dilemma in need of attention. Physical violence in particular, is the most prevalent type of violence across all genders, races, and nationalities.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says more than 43 million women and 38 million men report experiencing psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime. Meanwhile, 11 million women and 5 million men report enduring sexual or physical violence and intimate partner violence (IPV), and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetimes, according to the CDC.1

Women who have endured this kind of violence might present differently from men. Some studies, for example, show a more significant association between mutual violence, depression, and substance use among women than men.2 Studies on the phenomenon of IPV victims/survivors becoming perpetrators of abuse are limited, but that this happens in some cases.

Having a psychiatric disorder is associated with a higher likelihood of being physically violent with a partner.3,4 One recent study of 250 female psychiatric patients who were married and had no history of drug abuse found that almost 68% reported psychological abuse, 52% reported sexual abuse, 38% social abuse, 37% reported economic abuse, and 25% reported physical abuse.5

Given those statistics and trends, it is incumbent upon clinicians – including those in primary care, psychiatry, and emergency medicine – to learn to quickly identify IPV survivors, and to use available prognostic tools to monitor perpetrators and survivors.

COVID pandemic’s influence

Isolation tied to the COVID-19 pandemic has been linked to increased IPV. A study conducted by researchers at the University of California, Davis, suggested that extra stress experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic caused by income loss, and the inability to pay for housing and food exacerbated the prevalence of IPV early during the pandemic.6

That study, where researchers collected in surveys of nearly 400 adults in the beginning in April 2020 for 10 weeks, showed that more services and communication are needed so that frontline health care and food bank workers, for example, in addition to social workers, doctors, and therapists, can spot the signs and ask clients questions about potential IPV. They could then link survivors to pertinent assistance and resources.

Furthermore, multiple factors probably have played a pivotal role in increasing the prevalence of IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, disruption to usual health and social services as well as diminished access to support systems, such as shelters, and charity helplines negatively affected the reporting of domestic violence.

Long before the pandemic, over the past decade, international and national bodies have played a crucial role in terms of improving the awareness and response to domestic violence.7,8 In addition, several policies have been introduced in countries around the globe emphasizing the need to inquire routinely about domestic violence. Nevertheless, mental health services often fail to adequately address domestic violence in clinical encounters. A systematic review of domestic violence assessment screening performed in a variety of health care settings found that evidence was insufficient to conclude that routine inquiry improved morbidity and mortality among victims of IPV.9 So the question becomes: How can we get our patients to tell us about these experiences so we can intervene?

Gender differences in perpetuating IPV

Several studies have found that abuse can result in various mental illnesses, such as depression, PTSD, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Again, men have a disproportionately higher rate of perpetrating IPV, compared with women. This theory has been a source of debate in the academic community for years, but recent research has confirmed that women do perpetuate violence against their partners to some extent.10,11

Some members of the LGBTQ+ community also report experiencing violence from partners, so as clinicians, we also need to raise our awareness about the existence of violence among same-sex couples. In fact, a team of Italian researchers report more than 50% of gay men and almost 75% of lesbian women reported that they had been psychologically abused by a partner.12 More research into this area is needed.

Our role as health care professionals

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advises that all clinic visits include regular IPV screening.13 But these screenings are all too rare. In fact, a meta-analysis of 19 trials of more than 1,600 participants showed only 9%-40% of doctors routinely test for IPV.14 That research clearly shows how important it is for all clinicians to execute IPV screening. However, numerous challenges toward screening exist, including personal discomfort, limited time during appointments, insufficient resources, and inadequate training.

One ongoing debate revolves around which clinician should screen for IPV. Should the psychiatrist carry out this role – or perhaps the primary care physician, nurse, or social worker? These issues become even more fraught when clinicians worry about offending the patient – especially if the clinician is a male.15

The bottom line is that physicians should inquire about intimate partner violence, because research indicates that women are more likely to reveal abuse when prompted. In addition, during physician appointments, they can use the physician-patient therapeutic connection to conduct a domestic violence evaluation, give resources to victims, and provide ongoing care. Patients who exhibit treatment resistance, persistent pain, depression, sleeplessness, and headaches should prompt psychiatrists to conduct additional investigations into the likelihood of intimate partner violence and domestic abuse.

W also should be attentive when counseling patients about domestic violence when suggesting life-changing events such as pregnancy, employment loss, separation, or divorce. Similar to the recommendations of the USPSTF that all women and men should be screened for IPV, it is suggested that physicians be conscious of facilitating a conversation and not being overtly judgmental while observing body cues. Using the statements such as “we have been hearing a lot of violence in our community lately” could be a segue to introduce the subject.

Asking the question of whether you are being hit rather than being abused has allowed more women to open up more about domestic violence. While physicians are aware that most victims might recant and often go back to their abusers, victims need to be counseled that the abuse might intensify and lead to death.

For women who perpetuate IPV and survivors of IPV, safety is the priority. Physicians should provide safety options and be the facilitators. Studies have shown that fewer victims get the referral to the supporting agencies when IPV is indicated, which puts their safety at risk. In women who commit IPV, clinicians should assess the role of the individual in an IPV disclosure. There are various treatment modalities, whether the violence is performed through self-defense, bidirectionally, or because of aggression.

With the advancement of technology, web-based training on how to ask for IPV, documentation, acknowledgment, and structured referral increase physicians’ confidence when faced with an IPV disclosure than none.16 Treatment modalities should include medication reconciliation and cognitive-behavioral therapy – focusing on emotion regulation.

Using instruments such as the danger assessment tool can help physicians intervene early, reducing the risk of domestic violence and IPV recurrence instead of using clinical assessment alone.17 Physicians should convey empathy, validate victims, and help, especially when abuse is reported.

Also, it is important to evaluate survivors’ safety. Counseling can help people rebuild their self-esteem. Structured referrals for psychiatric help and support services are needed to help survivors on the long road to recovery.

Training all physicians, regardless of specialty, is essential to improve prompt IPV identification and bring awareness to resources available to survivors when IPV is disclosed. Although we described an association between IPV victims becoming possible perpetrators of IPV, more long-term studies are required to show the various processes that influence IPV perpetration rates, especially by survivors.

We would also like international and national regulatory bodies to increase the awareness of IPV and adequately address IPV with special emphasis on how mental health services should assess, identify, and respond to services for people who are survivors and perpetrators of IPV.

Dr. Kumari, Dr. Otite, Dr. Afzal, Dr. Alcera, and Dr. Doumas are affiliated with Hackensack Meridian Health at Ocean Medical Center, Brick, N.J. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2020 Oct 9.

2. Yu R et al. PLOS Med. 16(12):e1002995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002995.

3. Oram S et al. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2014 Dec;23(4):361-76.

4. Munro OE and Sellbom M. Pers Ment Health. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1480.

5. Sahraian A et al. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102062.

6. Nikos-Rose K. “COVID-19 Isolation Linked to Increased Domestic Violence, Researchers Suggest.” 2021 Feb 24. University of California, Davis.

7. World Health Organization. “Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women.” WHO clinical policy guidelines. 2013.

8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. “Domestic violence and abuse: Multi-agency working.” PH50. 2014 Feb 26.

9. Feder GS et al. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):22-37.

10. Gondolf EW. Violence Against Women. 2014 Dec;20(12)1539-46.

11. Hamberger LK and Larsen SE. J Fam Violence. 2015;30(6):699-717.

12. Rollè L et al. Front Psychol. 21 Aug 2018. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01506.

13. Paterno MT and Draughon JE. J Midwif Women Health. 2016;61(31):370-5.

14. Kalra N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 May 31;5(5)CD012423.

15. Larsen SE and Hamberger LK. J Fam Viol. 2015;30:1007-30.

16. Kalra N et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD012423.

17. Campbell JC et al. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(4):653-74.

Treated with a mood stabilizer, he becomes incontinent and walks oddly

CASE Rapid decline

Mr. X, age 67, is a businessman who had a diagnosis of bipolar depression 8 years ago, and who is being evaluated now for new-onset cognitive impairment, gait disturbance that resembles child-like steps, dyskinesia, and urinary incontinence of approximately 2 months’ duration. He has been treated for bipolar depression with valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and venlafaxine, 150 mg/d, without complaint until now, since the diagnosis was made 8 years ago. The serum valproic acid level, tested every month, is within the therapeutic range; liver function tests, ordered every 6 months, also are within the normal range.

Mr. X has become confined to his bedroom and needs assistance to walk. He has to be lifted to a standing position by 2 attendants, who bear his weight and instruct him to take one step at a time. He wears a diaper and needs assistance shaving, showering, and getting dressed. When the treatment team asks him about his condition, Mr. X turns to his wife to respond on his behalf. He is slow to speak and struggles to remember the details about his condition or the duration of his disability.

Mr. X is referred to a neurologist, based on cognitive impairment and gait disturbance, who orders an MRI scan of the brain that shows enlarged ventricles and some cortical atrophy (Figure 1). A neurosurgeon removes approximately 25 mL of CSF as a diagnostic and therapeutic intervention.

Videography of his ambulation, recorded before and after the CSF tap, shows slight improvement in gait. Mr. X is seen by a neurosurgery team, who recommends that he receive a ventriculoperitoneal shunt for hydrocephalus.

While awaiting surgical treatment, Mr. X’s psychotropic medications are withheld, and he is closely monitored for reemergence of psychiatric symptoms. Mr. X shows gradual but significant improvement in his gait within 8 to 10 weeks. His dyskinesia improves significantly, as does his cognitive function.

What additional testing is recommended beyond MRI?

a) complete blood count with differential

b) blood ammonia level

c) neuropsychological evaluation

d) APOE-e4 genetic testing

e) all the above

The authors’ observations

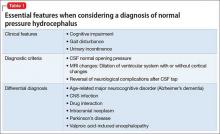

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is characterized by gait disturbance, dementia, or urinary incontinence that is associated with dilation of the brain’s ventricular system with normal opening CSF pressure (Table 1). Several studies have reported that patients with NPH might exhibit neuropsychiatric symptoms,1-4 possibly related to alterations in central neurotransmitter activity.5 NPH patients could present with symptoms reflecting frontal dominance (Table 2,6-9). In a study of 35 patients with idiopathic NPH in a tertiary hospital in Brazil,10 psychiatric symptoms were established by formal psychiatric evaluation in 71%, notably anxiety, depression, and psychotic syndromes.

Mechanism responsible for gait disturbance

Gait disturbance typically is the first and most prominent symptom of the NPH triad. Gait disturbance in NPH can be progressive because of expansion of the ventricular system, mainly the lateral ventricles, leading to pressure on the corticospinal motor fibers descending to the lumbosacral spinal cord. Although there is no one type of gait disturbance indicative of NPH, it often is described as shuffling, magnetic, and wide-based.11 Slowness of gait and gait imbalance or disequilibrium are common and more likely to respond to shunting.12

Drug-induced gait disturbance is likely to result in parkinsonian symptoms.13 A possible mechanism involves inhibition of neurite outgrowth. Qian et al14 found that therapeutic plasma levels of valproic acid reduced cell proliferation and neurite outgrowth, using SY5Y neuroblastoma cells as a neuronal model. Researchers also reported that valproic acid reduced mRNA and protein levels of neurofilament 160; a possible mechanistic explanation involves inhibition of neurite outgrowth that leads to gait disturbance. These effects reversed 2 days after stopping valproic acid.

Another possible mechanism is related to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) pathway disturbance leading to dopamine inhibition. This postulates that valproic acid or a metabolite of valproic acid, such as Δ-2-valproate, which may be a more potent inhibitor of the GABA-degrading enzyme than valproic acid, could cause a transient inhibitory effect on dopaminergic pathways.15

Mechanism of mood stabilizer action

Valproic acid is incorporated into neuronal membranes in a saturable manner and appears to displace naturally occurring branched-chain phospholipids.16 Chronic valproic acid use reduces protein kinase C (PKC) activity in patients with mania.17 Elevated PKC activity has been observed in patients with mania and in animal models of mania.18 Valproic acid has antioxidant effects and has reversed early DNA damage caused by amphetamine in an animal model of mania.19 Valproic acid and lithium both reduce inositol biosynthesis; the mechanism of action for valproic acid is unique, however, resulting from decreased myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase inhibition.20

There is not a strong correlation between serum valproic acid levels and antimanic effects, but levels in the range of 50 to 150 μg/mL generally are required for therapeutic effect.

Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of valproic acid

With most antiepileptic drugs, adverse effects mainly are dose-related and include sedation, drowsiness, incoordination, nausea, and fatigue. Careful dose titration can reduce the risk of these adverse effects. Research on mothers with epilepsy has shown an association between valproic acid exposure in utero and lower IQ and a higher prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in children.21

Adverse effects on cognitive functioning are infrequent; valproic acid improves cognition in select patients.22 In a 20-week randomized, observer-blinded, parallel-group trial, adding valproic acid to carbamazepine resulted in improvement in short-term verbal memory.23 In a group of geriatric patients (mean age 77 years), no adverse cognitive effects were observed with valproic acid use.24

Masmoudi et al25 evaluated dementia and extrapyramidal symptoms associated with long-term valproic acid use. Among the side effects attributed to valproic acid, parkinsonian syndromes and cognitive impairment were not commonly reported. In a prospective study, Armon et al26 found several abnormal symptoms and signs related to motor and cognitive function impairment in patients on long-term valproic acid therapy. These side effects might be related to a disturbance in the GABAergic pathways in the basal ganglia system. Note that Δ2-valproic acid, a metabolite of valproic acid, preferentially accumulates in select areas of the brain: the substantia nigra, superior and inferior colliculus, hippocampus, and medulla.

What is the next best step in management?

a) surgically implant a shunt

b) adjust the dosage of valproic acid

c) switch to monotherapy

d) switch to an alternative psychotropic medication

e) provide observation and follow-up

The authors’ observations

Unusual appearances of NPH symptoms could hinder early diagnosis and proper treatment. Mr. X was taking valproic acid and venlafaxine for bipolar depression, without any complaints, and was asymptomatic for 8 years—until he developed symptoms of NPH.

In patients who have what can be considered classic symptoms of NPH and are taking valproic acid, consider discontinuing the drug on a trial basis before resorting to a more invasive procedure. This strategy could significantly reduce the cost of health care and contribute to the overall well-being of the patient.

NPH associated with chronic valproic acid use is rare, supported by only 1 case report13 in our literature review. Based on the severity of symptoms and chance for misdiagnosis, it is essential to identify such cases and differentiate them from others with underlying neuropathology or a secondary cause, such as age-related dementia or Parkinson’s disease, to avoid the burden of unnecessary diagnostic testing on the patient and physician.

Family history also is important in cases presenting with sensorineural hearing loss,13 which follows a pattern of maternal inheritance. Consider genetic testing in such cases.

Earlier diagnosis of valproic acid-induced NPH enables specific interventions and treatment. Treatment of NPH includes one of several forms of shunting and appropriate neuroleptic therapy for behavioral symptoms. Although there is a significant risk (40% to 50%) of psychiatric and behavioral symptoms as a shunt-related complication, as many as 60% of operated patients showed objective improvement. This makes the diagnosis of NPH, and referral for appropriate surgical treatment of NPH, an important challenge to the psychiatrist.27

OUTCOME No reemergence

Findings on a repeat MRI 2.5 months after the CSF tap remain unchanged. Surgery is cancelled and medications are discontinued. Mr. X is advised to continue outpatient follow-up for monitoring of re-emerging symptoms of bipolar depression.

At a follow-up visit, Mr. X’s condition has returned to baseline. He ambulates spontaneously and responds to questions without evidence of cognitive deficit. He no longer is incontinent.

Follow-up MRI is performed and indicated normal results.

Neuropsychological testing is deemed unnecessary because Mr. X has fully recovered from cognitive clouding (and there would be no baseline results against which to compare current findings). Based on the medication history, the team concludes that prolonged use of valproic acid may have led to development of signs and symptoms of an NPH-like syndrome.

The authors’ observations

Awareness of an association of NPH with neuropsychiatric changes is important for clinical psychiatrists because early assessment and appropriate intervention can prevent associated long-term complications. Valproic acid is considered a relatively safe medication with few neurologic side effects, but the association of an NPH-like syndrome with chronic valproic acid use, documented in this case report, emphasizes the importance of studying long-term consequences of using valproic acid in geriatric patients. More such case reports need to be evaluated to study the association of neuropsychiatric complications with chronic valproic use in the geriatric population.

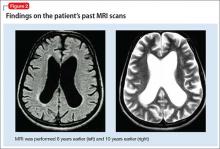

Mr. X apparently had cerebral atrophy with enlarged ventricles that was consistently evident for 10 years (Figure 2), although he has been maintained on valproic acid for 8 years. What is intriguing in this case is that discontinuing valproic acid relieved the triad of incontinence, imbalance, and memory deficits indicative of NPH. Mr. X remains free of these symptoms.

1. Pinner G, Johnson H, Bouman WP, et al. Psychiatric manifestations of normal-pressure hydrocephalus: a short review and unusual case. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(4):465-470.

2. Alao AO, Naprawa SA. Psychiatric complications of hydrocephalus. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31(3):337-340.

3. Lindqvist G, Andersson H, Bilting M, et al. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: psychiatric findings before and after shunt operation classified in a new diagnostic system for organic psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1993;373:18-32.

4. Kito Y, Kazui H, Kubo Y, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Behav Neurol. 2009;21(3):165-174.

5. Markianos M, Lafazanos S, Koutsis G, et al. CSF neurotransmitter metabolites and neuropsychiatric symptomatology in patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111(3):231-234.

6. McIntyre AW, Emsley RA. Shoplifting associated with normal-pressure hydrocephalus: report of a case. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1990;3(4):229-230.

7. Kwentus JA, Hart RP. Normal pressure hydrocephalus presenting as mania. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175(8):500-502.

8. Bloom KK, Kraft WA. Paranoia—an unusual presentation of hydrocephalus. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;77(2):157-159.

9. Yusim A, Anbarasan D, Bernstein C, et al. Normal pressure hydrocephalus presenting as Othello syndrome: case presentation and review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1119-1125.

10. Oliveira MF, Oliveira JR, Rotta JM, et al. Psychiatric symptoms are present in most of the patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72(6):435-438.

11. Marmarou A, Young HF, Aygok GA, et al. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus: a prospective study in 151 patients. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(6):987-997.

12. Bugalho P, Guimarães J. Gait disturbance in normal pressure hydrocephalus: a clinical study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(7):434-437.

13. Evans MD, Shinar R, Yaari R. Reversible dementia and gait disturbance after prolonged use of valproic acid. Seizure. 2011;20(6):509-511.

14. Qian Y, Zheng Y, Tiffany-Castiglioni E. Valproate reversibly reduces neurite outgrowth by human SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2009;1302:21-33.

15. Löscher W. Pharmacological, toxicological and neurochemical effects of delta 2(E)-valproate in animals. Pharm Weekbl Sci. 1992;14(3A):139-143.

16. Siafaka-Kapadai A, Patiris M, Bowden C, et al. Incorporation of [3H]-valproic acid into lipids in GT1-7 neurons. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56(2):207-212.

17. Hahn CG, Umapathy, Wagn HY, et al. Lithium and valproic acid treatments reduce PKC activation and receptor-G-protein coupling in platelets of bipolar manic patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39(4):35-63.

18. Einat H, Manji HK. Cellular plasticity cascades: genes-to-behavior pathways in animal models of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(12):1160-1171.

19. Andreazza AC, Frey BN, Stertz L, et al. Effects of lithium and valproate on DNA damage and oxidative stress markers in an animal model of mania [abstract P10]. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(suppl 1):16.

20. Galit S, Shirley M, Ora K, et al. Effect of valproate derivatives on human brain myo-inositol-1-phosphate (MIP) synthase activity and amphetamine-induced rearing. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59(4):402-407.

21. Kennedy GM, Lhatoo SD. CNS adverse events associated with antiepileptic drugs. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(9):739-760.

22. Prevey ML, Delaney RC, Cramer JA, et al. Effect of valproate on cognitive functioning. Comparison with carbamazepine. The Department of Veteran Affairs Epilepsy Cooperative Study 264 Group. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(10):1008-1016.

23. Aldenkamp AP, Baker G, Mulder OG, et al. A multicenter randomized clinical study to evaluate the effect on cognitive function of topiramate compared with valproate as add-on therapy to carbamazepine in patients with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2000;41(9):1167-1178.

24. Craig I, Tallis R. Impact of valproate and phenytoin on cognitive function in elderly patients: results of a single-blind randomized comparative study. Epilepsia. 1994;35(2):381-390.

25. Masmoudi K, Gras-Champel V, Bonnet I, et al. Dementia and extrapyramidal problems caused by long-term valproic acid [in French]. Therapie. 2000;55(5):629-634.

26. Armon C, Shin C, Miller P, et al. Reversible parkinsonism and cognitive impairment with chronic valproate use. Neurology. 1996;47(3):626-635.

27. Price TR, Tucker GJ. Psychiatric and behavioral manifestations of normal pressure hydrocephalus. A case report and brief review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1977;164(1):51-55.

CASE Rapid decline

Mr. X, age 67, is a businessman who had a diagnosis of bipolar depression 8 years ago, and who is being evaluated now for new-onset cognitive impairment, gait disturbance that resembles child-like steps, dyskinesia, and urinary incontinence of approximately 2 months’ duration. He has been treated for bipolar depression with valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and venlafaxine, 150 mg/d, without complaint until now, since the diagnosis was made 8 years ago. The serum valproic acid level, tested every month, is within the therapeutic range; liver function tests, ordered every 6 months, also are within the normal range.

Mr. X has become confined to his bedroom and needs assistance to walk. He has to be lifted to a standing position by 2 attendants, who bear his weight and instruct him to take one step at a time. He wears a diaper and needs assistance shaving, showering, and getting dressed. When the treatment team asks him about his condition, Mr. X turns to his wife to respond on his behalf. He is slow to speak and struggles to remember the details about his condition or the duration of his disability.

Mr. X is referred to a neurologist, based on cognitive impairment and gait disturbance, who orders an MRI scan of the brain that shows enlarged ventricles and some cortical atrophy (Figure 1). A neurosurgeon removes approximately 25 mL of CSF as a diagnostic and therapeutic intervention.

Videography of his ambulation, recorded before and after the CSF tap, shows slight improvement in gait. Mr. X is seen by a neurosurgery team, who recommends that he receive a ventriculoperitoneal shunt for hydrocephalus.

While awaiting surgical treatment, Mr. X’s psychotropic medications are withheld, and he is closely monitored for reemergence of psychiatric symptoms. Mr. X shows gradual but significant improvement in his gait within 8 to 10 weeks. His dyskinesia improves significantly, as does his cognitive function.

What additional testing is recommended beyond MRI?

a) complete blood count with differential

b) blood ammonia level

c) neuropsychological evaluation

d) APOE-e4 genetic testing

e) all the above

The authors’ observations

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is characterized by gait disturbance, dementia, or urinary incontinence that is associated with dilation of the brain’s ventricular system with normal opening CSF pressure (Table 1). Several studies have reported that patients with NPH might exhibit neuropsychiatric symptoms,1-4 possibly related to alterations in central neurotransmitter activity.5 NPH patients could present with symptoms reflecting frontal dominance (Table 2,6-9). In a study of 35 patients with idiopathic NPH in a tertiary hospital in Brazil,10 psychiatric symptoms were established by formal psychiatric evaluation in 71%, notably anxiety, depression, and psychotic syndromes.

Mechanism responsible for gait disturbance

Gait disturbance typically is the first and most prominent symptom of the NPH triad. Gait disturbance in NPH can be progressive because of expansion of the ventricular system, mainly the lateral ventricles, leading to pressure on the corticospinal motor fibers descending to the lumbosacral spinal cord. Although there is no one type of gait disturbance indicative of NPH, it often is described as shuffling, magnetic, and wide-based.11 Slowness of gait and gait imbalance or disequilibrium are common and more likely to respond to shunting.12

Drug-induced gait disturbance is likely to result in parkinsonian symptoms.13 A possible mechanism involves inhibition of neurite outgrowth. Qian et al14 found that therapeutic plasma levels of valproic acid reduced cell proliferation and neurite outgrowth, using SY5Y neuroblastoma cells as a neuronal model. Researchers also reported that valproic acid reduced mRNA and protein levels of neurofilament 160; a possible mechanistic explanation involves inhibition of neurite outgrowth that leads to gait disturbance. These effects reversed 2 days after stopping valproic acid.

Another possible mechanism is related to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) pathway disturbance leading to dopamine inhibition. This postulates that valproic acid or a metabolite of valproic acid, such as Δ-2-valproate, which may be a more potent inhibitor of the GABA-degrading enzyme than valproic acid, could cause a transient inhibitory effect on dopaminergic pathways.15

Mechanism of mood stabilizer action

Valproic acid is incorporated into neuronal membranes in a saturable manner and appears to displace naturally occurring branched-chain phospholipids.16 Chronic valproic acid use reduces protein kinase C (PKC) activity in patients with mania.17 Elevated PKC activity has been observed in patients with mania and in animal models of mania.18 Valproic acid has antioxidant effects and has reversed early DNA damage caused by amphetamine in an animal model of mania.19 Valproic acid and lithium both reduce inositol biosynthesis; the mechanism of action for valproic acid is unique, however, resulting from decreased myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase inhibition.20

There is not a strong correlation between serum valproic acid levels and antimanic effects, but levels in the range of 50 to 150 μg/mL generally are required for therapeutic effect.

Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of valproic acid

With most antiepileptic drugs, adverse effects mainly are dose-related and include sedation, drowsiness, incoordination, nausea, and fatigue. Careful dose titration can reduce the risk of these adverse effects. Research on mothers with epilepsy has shown an association between valproic acid exposure in utero and lower IQ and a higher prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in children.21

Adverse effects on cognitive functioning are infrequent; valproic acid improves cognition in select patients.22 In a 20-week randomized, observer-blinded, parallel-group trial, adding valproic acid to carbamazepine resulted in improvement in short-term verbal memory.23 In a group of geriatric patients (mean age 77 years), no adverse cognitive effects were observed with valproic acid use.24

Masmoudi et al25 evaluated dementia and extrapyramidal symptoms associated with long-term valproic acid use. Among the side effects attributed to valproic acid, parkinsonian syndromes and cognitive impairment were not commonly reported. In a prospective study, Armon et al26 found several abnormal symptoms and signs related to motor and cognitive function impairment in patients on long-term valproic acid therapy. These side effects might be related to a disturbance in the GABAergic pathways in the basal ganglia system. Note that Δ2-valproic acid, a metabolite of valproic acid, preferentially accumulates in select areas of the brain: the substantia nigra, superior and inferior colliculus, hippocampus, and medulla.

What is the next best step in management?

a) surgically implant a shunt

b) adjust the dosage of valproic acid

c) switch to monotherapy

d) switch to an alternative psychotropic medication

e) provide observation and follow-up

The authors’ observations

Unusual appearances of NPH symptoms could hinder early diagnosis and proper treatment. Mr. X was taking valproic acid and venlafaxine for bipolar depression, without any complaints, and was asymptomatic for 8 years—until he developed symptoms of NPH.

In patients who have what can be considered classic symptoms of NPH and are taking valproic acid, consider discontinuing the drug on a trial basis before resorting to a more invasive procedure. This strategy could significantly reduce the cost of health care and contribute to the overall well-being of the patient.

NPH associated with chronic valproic acid use is rare, supported by only 1 case report13 in our literature review. Based on the severity of symptoms and chance for misdiagnosis, it is essential to identify such cases and differentiate them from others with underlying neuropathology or a secondary cause, such as age-related dementia or Parkinson’s disease, to avoid the burden of unnecessary diagnostic testing on the patient and physician.

Family history also is important in cases presenting with sensorineural hearing loss,13 which follows a pattern of maternal inheritance. Consider genetic testing in such cases.

Earlier diagnosis of valproic acid-induced NPH enables specific interventions and treatment. Treatment of NPH includes one of several forms of shunting and appropriate neuroleptic therapy for behavioral symptoms. Although there is a significant risk (40% to 50%) of psychiatric and behavioral symptoms as a shunt-related complication, as many as 60% of operated patients showed objective improvement. This makes the diagnosis of NPH, and referral for appropriate surgical treatment of NPH, an important challenge to the psychiatrist.27

OUTCOME No reemergence

Findings on a repeat MRI 2.5 months after the CSF tap remain unchanged. Surgery is cancelled and medications are discontinued. Mr. X is advised to continue outpatient follow-up for monitoring of re-emerging symptoms of bipolar depression.

At a follow-up visit, Mr. X’s condition has returned to baseline. He ambulates spontaneously and responds to questions without evidence of cognitive deficit. He no longer is incontinent.

Follow-up MRI is performed and indicated normal results.

Neuropsychological testing is deemed unnecessary because Mr. X has fully recovered from cognitive clouding (and there would be no baseline results against which to compare current findings). Based on the medication history, the team concludes that prolonged use of valproic acid may have led to development of signs and symptoms of an NPH-like syndrome.

The authors’ observations

Awareness of an association of NPH with neuropsychiatric changes is important for clinical psychiatrists because early assessment and appropriate intervention can prevent associated long-term complications. Valproic acid is considered a relatively safe medication with few neurologic side effects, but the association of an NPH-like syndrome with chronic valproic acid use, documented in this case report, emphasizes the importance of studying long-term consequences of using valproic acid in geriatric patients. More such case reports need to be evaluated to study the association of neuropsychiatric complications with chronic valproic use in the geriatric population.

Mr. X apparently had cerebral atrophy with enlarged ventricles that was consistently evident for 10 years (Figure 2), although he has been maintained on valproic acid for 8 years. What is intriguing in this case is that discontinuing valproic acid relieved the triad of incontinence, imbalance, and memory deficits indicative of NPH. Mr. X remains free of these symptoms.

CASE Rapid decline

Mr. X, age 67, is a businessman who had a diagnosis of bipolar depression 8 years ago, and who is being evaluated now for new-onset cognitive impairment, gait disturbance that resembles child-like steps, dyskinesia, and urinary incontinence of approximately 2 months’ duration. He has been treated for bipolar depression with valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and venlafaxine, 150 mg/d, without complaint until now, since the diagnosis was made 8 years ago. The serum valproic acid level, tested every month, is within the therapeutic range; liver function tests, ordered every 6 months, also are within the normal range.

Mr. X has become confined to his bedroom and needs assistance to walk. He has to be lifted to a standing position by 2 attendants, who bear his weight and instruct him to take one step at a time. He wears a diaper and needs assistance shaving, showering, and getting dressed. When the treatment team asks him about his condition, Mr. X turns to his wife to respond on his behalf. He is slow to speak and struggles to remember the details about his condition or the duration of his disability.

Mr. X is referred to a neurologist, based on cognitive impairment and gait disturbance, who orders an MRI scan of the brain that shows enlarged ventricles and some cortical atrophy (Figure 1). A neurosurgeon removes approximately 25 mL of CSF as a diagnostic and therapeutic intervention.

Videography of his ambulation, recorded before and after the CSF tap, shows slight improvement in gait. Mr. X is seen by a neurosurgery team, who recommends that he receive a ventriculoperitoneal shunt for hydrocephalus.

While awaiting surgical treatment, Mr. X’s psychotropic medications are withheld, and he is closely monitored for reemergence of psychiatric symptoms. Mr. X shows gradual but significant improvement in his gait within 8 to 10 weeks. His dyskinesia improves significantly, as does his cognitive function.

What additional testing is recommended beyond MRI?

a) complete blood count with differential

b) blood ammonia level

c) neuropsychological evaluation

d) APOE-e4 genetic testing

e) all the above

The authors’ observations

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is characterized by gait disturbance, dementia, or urinary incontinence that is associated with dilation of the brain’s ventricular system with normal opening CSF pressure (Table 1). Several studies have reported that patients with NPH might exhibit neuropsychiatric symptoms,1-4 possibly related to alterations in central neurotransmitter activity.5 NPH patients could present with symptoms reflecting frontal dominance (Table 2,6-9). In a study of 35 patients with idiopathic NPH in a tertiary hospital in Brazil,10 psychiatric symptoms were established by formal psychiatric evaluation in 71%, notably anxiety, depression, and psychotic syndromes.

Mechanism responsible for gait disturbance

Gait disturbance typically is the first and most prominent symptom of the NPH triad. Gait disturbance in NPH can be progressive because of expansion of the ventricular system, mainly the lateral ventricles, leading to pressure on the corticospinal motor fibers descending to the lumbosacral spinal cord. Although there is no one type of gait disturbance indicative of NPH, it often is described as shuffling, magnetic, and wide-based.11 Slowness of gait and gait imbalance or disequilibrium are common and more likely to respond to shunting.12

Drug-induced gait disturbance is likely to result in parkinsonian symptoms.13 A possible mechanism involves inhibition of neurite outgrowth. Qian et al14 found that therapeutic plasma levels of valproic acid reduced cell proliferation and neurite outgrowth, using SY5Y neuroblastoma cells as a neuronal model. Researchers also reported that valproic acid reduced mRNA and protein levels of neurofilament 160; a possible mechanistic explanation involves inhibition of neurite outgrowth that leads to gait disturbance. These effects reversed 2 days after stopping valproic acid.

Another possible mechanism is related to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) pathway disturbance leading to dopamine inhibition. This postulates that valproic acid or a metabolite of valproic acid, such as Δ-2-valproate, which may be a more potent inhibitor of the GABA-degrading enzyme than valproic acid, could cause a transient inhibitory effect on dopaminergic pathways.15

Mechanism of mood stabilizer action

Valproic acid is incorporated into neuronal membranes in a saturable manner and appears to displace naturally occurring branched-chain phospholipids.16 Chronic valproic acid use reduces protein kinase C (PKC) activity in patients with mania.17 Elevated PKC activity has been observed in patients with mania and in animal models of mania.18 Valproic acid has antioxidant effects and has reversed early DNA damage caused by amphetamine in an animal model of mania.19 Valproic acid and lithium both reduce inositol biosynthesis; the mechanism of action for valproic acid is unique, however, resulting from decreased myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase inhibition.20

There is not a strong correlation between serum valproic acid levels and antimanic effects, but levels in the range of 50 to 150 μg/mL generally are required for therapeutic effect.

Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of valproic acid

With most antiepileptic drugs, adverse effects mainly are dose-related and include sedation, drowsiness, incoordination, nausea, and fatigue. Careful dose titration can reduce the risk of these adverse effects. Research on mothers with epilepsy has shown an association between valproic acid exposure in utero and lower IQ and a higher prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in children.21

Adverse effects on cognitive functioning are infrequent; valproic acid improves cognition in select patients.22 In a 20-week randomized, observer-blinded, parallel-group trial, adding valproic acid to carbamazepine resulted in improvement in short-term verbal memory.23 In a group of geriatric patients (mean age 77 years), no adverse cognitive effects were observed with valproic acid use.24

Masmoudi et al25 evaluated dementia and extrapyramidal symptoms associated with long-term valproic acid use. Among the side effects attributed to valproic acid, parkinsonian syndromes and cognitive impairment were not commonly reported. In a prospective study, Armon et al26 found several abnormal symptoms and signs related to motor and cognitive function impairment in patients on long-term valproic acid therapy. These side effects might be related to a disturbance in the GABAergic pathways in the basal ganglia system. Note that Δ2-valproic acid, a metabolite of valproic acid, preferentially accumulates in select areas of the brain: the substantia nigra, superior and inferior colliculus, hippocampus, and medulla.

What is the next best step in management?

a) surgically implant a shunt

b) adjust the dosage of valproic acid

c) switch to monotherapy

d) switch to an alternative psychotropic medication

e) provide observation and follow-up

The authors’ observations

Unusual appearances of NPH symptoms could hinder early diagnosis and proper treatment. Mr. X was taking valproic acid and venlafaxine for bipolar depression, without any complaints, and was asymptomatic for 8 years—until he developed symptoms of NPH.

In patients who have what can be considered classic symptoms of NPH and are taking valproic acid, consider discontinuing the drug on a trial basis before resorting to a more invasive procedure. This strategy could significantly reduce the cost of health care and contribute to the overall well-being of the patient.

NPH associated with chronic valproic acid use is rare, supported by only 1 case report13 in our literature review. Based on the severity of symptoms and chance for misdiagnosis, it is essential to identify such cases and differentiate them from others with underlying neuropathology or a secondary cause, such as age-related dementia or Parkinson’s disease, to avoid the burden of unnecessary diagnostic testing on the patient and physician.

Family history also is important in cases presenting with sensorineural hearing loss,13 which follows a pattern of maternal inheritance. Consider genetic testing in such cases.

Earlier diagnosis of valproic acid-induced NPH enables specific interventions and treatment. Treatment of NPH includes one of several forms of shunting and appropriate neuroleptic therapy for behavioral symptoms. Although there is a significant risk (40% to 50%) of psychiatric and behavioral symptoms as a shunt-related complication, as many as 60% of operated patients showed objective improvement. This makes the diagnosis of NPH, and referral for appropriate surgical treatment of NPH, an important challenge to the psychiatrist.27

OUTCOME No reemergence

Findings on a repeat MRI 2.5 months after the CSF tap remain unchanged. Surgery is cancelled and medications are discontinued. Mr. X is advised to continue outpatient follow-up for monitoring of re-emerging symptoms of bipolar depression.

At a follow-up visit, Mr. X’s condition has returned to baseline. He ambulates spontaneously and responds to questions without evidence of cognitive deficit. He no longer is incontinent.

Follow-up MRI is performed and indicated normal results.

Neuropsychological testing is deemed unnecessary because Mr. X has fully recovered from cognitive clouding (and there would be no baseline results against which to compare current findings). Based on the medication history, the team concludes that prolonged use of valproic acid may have led to development of signs and symptoms of an NPH-like syndrome.

The authors’ observations

Awareness of an association of NPH with neuropsychiatric changes is important for clinical psychiatrists because early assessment and appropriate intervention can prevent associated long-term complications. Valproic acid is considered a relatively safe medication with few neurologic side effects, but the association of an NPH-like syndrome with chronic valproic acid use, documented in this case report, emphasizes the importance of studying long-term consequences of using valproic acid in geriatric patients. More such case reports need to be evaluated to study the association of neuropsychiatric complications with chronic valproic use in the geriatric population.

Mr. X apparently had cerebral atrophy with enlarged ventricles that was consistently evident for 10 years (Figure 2), although he has been maintained on valproic acid for 8 years. What is intriguing in this case is that discontinuing valproic acid relieved the triad of incontinence, imbalance, and memory deficits indicative of NPH. Mr. X remains free of these symptoms.

1. Pinner G, Johnson H, Bouman WP, et al. Psychiatric manifestations of normal-pressure hydrocephalus: a short review and unusual case. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(4):465-470.

2. Alao AO, Naprawa SA. Psychiatric complications of hydrocephalus. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31(3):337-340.

3. Lindqvist G, Andersson H, Bilting M, et al. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: psychiatric findings before and after shunt operation classified in a new diagnostic system for organic psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1993;373:18-32.

4. Kito Y, Kazui H, Kubo Y, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Behav Neurol. 2009;21(3):165-174.

5. Markianos M, Lafazanos S, Koutsis G, et al. CSF neurotransmitter metabolites and neuropsychiatric symptomatology in patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111(3):231-234.

6. McIntyre AW, Emsley RA. Shoplifting associated with normal-pressure hydrocephalus: report of a case. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1990;3(4):229-230.

7. Kwentus JA, Hart RP. Normal pressure hydrocephalus presenting as mania. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175(8):500-502.

8. Bloom KK, Kraft WA. Paranoia—an unusual presentation of hydrocephalus. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;77(2):157-159.

9. Yusim A, Anbarasan D, Bernstein C, et al. Normal pressure hydrocephalus presenting as Othello syndrome: case presentation and review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1119-1125.

10. Oliveira MF, Oliveira JR, Rotta JM, et al. Psychiatric symptoms are present in most of the patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72(6):435-438.

11. Marmarou A, Young HF, Aygok GA, et al. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus: a prospective study in 151 patients. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(6):987-997.

12. Bugalho P, Guimarães J. Gait disturbance in normal pressure hydrocephalus: a clinical study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(7):434-437.

13. Evans MD, Shinar R, Yaari R. Reversible dementia and gait disturbance after prolonged use of valproic acid. Seizure. 2011;20(6):509-511.

14. Qian Y, Zheng Y, Tiffany-Castiglioni E. Valproate reversibly reduces neurite outgrowth by human SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2009;1302:21-33.

15. Löscher W. Pharmacological, toxicological and neurochemical effects of delta 2(E)-valproate in animals. Pharm Weekbl Sci. 1992;14(3A):139-143.

16. Siafaka-Kapadai A, Patiris M, Bowden C, et al. Incorporation of [3H]-valproic acid into lipids in GT1-7 neurons. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56(2):207-212.

17. Hahn CG, Umapathy, Wagn HY, et al. Lithium and valproic acid treatments reduce PKC activation and receptor-G-protein coupling in platelets of bipolar manic patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39(4):35-63.

18. Einat H, Manji HK. Cellular plasticity cascades: genes-to-behavior pathways in animal models of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(12):1160-1171.

19. Andreazza AC, Frey BN, Stertz L, et al. Effects of lithium and valproate on DNA damage and oxidative stress markers in an animal model of mania [abstract P10]. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(suppl 1):16.

20. Galit S, Shirley M, Ora K, et al. Effect of valproate derivatives on human brain myo-inositol-1-phosphate (MIP) synthase activity and amphetamine-induced rearing. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59(4):402-407.

21. Kennedy GM, Lhatoo SD. CNS adverse events associated with antiepileptic drugs. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(9):739-760.

22. Prevey ML, Delaney RC, Cramer JA, et al. Effect of valproate on cognitive functioning. Comparison with carbamazepine. The Department of Veteran Affairs Epilepsy Cooperative Study 264 Group. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(10):1008-1016.

23. Aldenkamp AP, Baker G, Mulder OG, et al. A multicenter randomized clinical study to evaluate the effect on cognitive function of topiramate compared with valproate as add-on therapy to carbamazepine in patients with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2000;41(9):1167-1178.

24. Craig I, Tallis R. Impact of valproate and phenytoin on cognitive function in elderly patients: results of a single-blind randomized comparative study. Epilepsia. 1994;35(2):381-390.

25. Masmoudi K, Gras-Champel V, Bonnet I, et al. Dementia and extrapyramidal problems caused by long-term valproic acid [in French]. Therapie. 2000;55(5):629-634.

26. Armon C, Shin C, Miller P, et al. Reversible parkinsonism and cognitive impairment with chronic valproate use. Neurology. 1996;47(3):626-635.

27. Price TR, Tucker GJ. Psychiatric and behavioral manifestations of normal pressure hydrocephalus. A case report and brief review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1977;164(1):51-55.

1. Pinner G, Johnson H, Bouman WP, et al. Psychiatric manifestations of normal-pressure hydrocephalus: a short review and unusual case. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(4):465-470.

2. Alao AO, Naprawa SA. Psychiatric complications of hydrocephalus. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31(3):337-340.

3. Lindqvist G, Andersson H, Bilting M, et al. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: psychiatric findings before and after shunt operation classified in a new diagnostic system for organic psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1993;373:18-32.

4. Kito Y, Kazui H, Kubo Y, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Behav Neurol. 2009;21(3):165-174.

5. Markianos M, Lafazanos S, Koutsis G, et al. CSF neurotransmitter metabolites and neuropsychiatric symptomatology in patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111(3):231-234.

6. McIntyre AW, Emsley RA. Shoplifting associated with normal-pressure hydrocephalus: report of a case. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1990;3(4):229-230.

7. Kwentus JA, Hart RP. Normal pressure hydrocephalus presenting as mania. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175(8):500-502.

8. Bloom KK, Kraft WA. Paranoia—an unusual presentation of hydrocephalus. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;77(2):157-159.

9. Yusim A, Anbarasan D, Bernstein C, et al. Normal pressure hydrocephalus presenting as Othello syndrome: case presentation and review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1119-1125.

10. Oliveira MF, Oliveira JR, Rotta JM, et al. Psychiatric symptoms are present in most of the patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72(6):435-438.

11. Marmarou A, Young HF, Aygok GA, et al. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus: a prospective study in 151 patients. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(6):987-997.

12. Bugalho P, Guimarães J. Gait disturbance in normal pressure hydrocephalus: a clinical study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(7):434-437.

13. Evans MD, Shinar R, Yaari R. Reversible dementia and gait disturbance after prolonged use of valproic acid. Seizure. 2011;20(6):509-511.

14. Qian Y, Zheng Y, Tiffany-Castiglioni E. Valproate reversibly reduces neurite outgrowth by human SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2009;1302:21-33.

15. Löscher W. Pharmacological, toxicological and neurochemical effects of delta 2(E)-valproate in animals. Pharm Weekbl Sci. 1992;14(3A):139-143.

16. Siafaka-Kapadai A, Patiris M, Bowden C, et al. Incorporation of [3H]-valproic acid into lipids in GT1-7 neurons. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56(2):207-212.

17. Hahn CG, Umapathy, Wagn HY, et al. Lithium and valproic acid treatments reduce PKC activation and receptor-G-protein coupling in platelets of bipolar manic patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39(4):35-63.

18. Einat H, Manji HK. Cellular plasticity cascades: genes-to-behavior pathways in animal models of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(12):1160-1171.

19. Andreazza AC, Frey BN, Stertz L, et al. Effects of lithium and valproate on DNA damage and oxidative stress markers in an animal model of mania [abstract P10]. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(suppl 1):16.

20. Galit S, Shirley M, Ora K, et al. Effect of valproate derivatives on human brain myo-inositol-1-phosphate (MIP) synthase activity and amphetamine-induced rearing. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59(4):402-407.

21. Kennedy GM, Lhatoo SD. CNS adverse events associated with antiepileptic drugs. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(9):739-760.

22. Prevey ML, Delaney RC, Cramer JA, et al. Effect of valproate on cognitive functioning. Comparison with carbamazepine. The Department of Veteran Affairs Epilepsy Cooperative Study 264 Group. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(10):1008-1016.

23. Aldenkamp AP, Baker G, Mulder OG, et al. A multicenter randomized clinical study to evaluate the effect on cognitive function of topiramate compared with valproate as add-on therapy to carbamazepine in patients with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2000;41(9):1167-1178.

24. Craig I, Tallis R. Impact of valproate and phenytoin on cognitive function in elderly patients: results of a single-blind randomized comparative study. Epilepsia. 1994;35(2):381-390.

25. Masmoudi K, Gras-Champel V, Bonnet I, et al. Dementia and extrapyramidal problems caused by long-term valproic acid [in French]. Therapie. 2000;55(5):629-634.

26. Armon C, Shin C, Miller P, et al. Reversible parkinsonism and cognitive impairment with chronic valproate use. Neurology. 1996;47(3):626-635.

27. Price TR, Tucker GJ. Psychiatric and behavioral manifestations of normal pressure hydrocephalus. A case report and brief review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1977;164(1):51-55.