User login

Urologist Workforce Variation Across the VHA

The VHA is the nation’s largest integrated health care delivery system, providing comprehensive medical care to about 6 million patients annually. In addition to revolutionizing its primary care delivery through widespread implementation of patient-centered medical homes (Patient Aligned Care Teams), the VHA is also transforming its specialty care delivery through use of its specialist workforce and innovative technologies, such as telemedicine and electronic consultations (e-consults).1

VHA specialty care is currently distributed using a hub and spoke model within larger regional networks spanning the U.S. This approach helps overcome geographic variation in specialist workforce (eg, predilection for metropolitan areas) but limits specialty care access for patients and primary care providers (PCPs) due to distance barriers.2-4 With the VHA electronic medical record (EMR) system, it is now feasible to send expertise electronically across the system (eg, e-consult). Whether this should occur at the regional VISN or national level to smooth out variation in specialist workforce depends in part on current specialist distribution within and across regions.

Related: Recurrent Multidrug Resistant Urinary Tract Infections in Geriatric Patients

Hand in hand with an aging veteran population is a growing clinical demand for urologic specialty care to treat urinary incontinence, prostate enlargement, and prostate cancer. Unfortunately, over 60% of U.S. counties lack a urologist, creating troublesome workforce issues.3 For these reasons, this study analyzed existing administrative data to understand regional variations in the distribution of and demands for the VHA urologist workforce. This study tested whether workforce distribution is balanced or imbalanced across regional networks, in part to inform whether the VHA should offer electronic or other national access to its urologic specialty care.

Methods

Fiscal year (FY) 2011 Specialty Physician Workforce Annual Report data from the VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing was used to characterize the distribution and concentration of urologists at 130 VHA facilities.5 The annual report provided a longitudinal management tool for reporting clinical productivity, efficiency, and staffing, and included benchmark data for each facility (eg, physician workforce, annual patient visits).

Demand for Urologic Specialty Care

The number of unique urology patients from the report was used as one approach to the demand for VHA urologic specialty care. This measure represented the number of unique patients evaluated in a urology clinic at least once over the FY. The number of newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer in calendar year 2010 within each VISN was also used as a more discrete measure of regional urologic care demand. Whereas care for other common urologic conditions, such as incontinence or prostate enlargement, may or may not be referred (ie, latent demand), prostate cancer care consistently involves urologists and is more specific for caseload.

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Because each VISN covered a relatively large geographic area, most with roughly equivalent numbers of facilities, there was no a priori reason to expect a difference in urologic workload and consequently urologic workforce between networks. On the other hand, within networks one might expect that urologists would be concentrated in hospitals that have more complicated patient cases, because the hospitals serve a tertiary or referral role. Yet even within a network, significant imbalances in specialist supply might require creative solutions to maintain adequate access of patients and PCPs to specialists.

Urologist Workforce

The full-time equivalent employee (FTEE) variable for urologic specialty care from the 2011 annual report was used as the primary outcome measure for urology workforce.5 This facility-level measure represented the clinical time urologists spent in direct patient care at each facility. It included the clinical effort of full-time as well as contract physicians and was also reported as an aggregate measure at the regional VISN level. Urologist workforce at the VISN level was the sum of all urologist FTEEs within its facilities. Adjusted rates also were provided (eg, FTEE/10,000 urology patients).

Other Workforce Factors

Also examined as covariates in the analysis were other measures related to urologist workforce. As the nation’s largest provider of graduate medical education, urology residents rotate through many VHA facilities, contributing to the workforce totals. For this reason, resident FTEE was examined as an independent variable in this study.

Understanding facility complexity (ie, case mix) was also essential for rational allocation of specialty care resources, as demand generally increases with increasing case mix. Therefore, a medical center group (MCG) case mix measure of complexity and its relationship with urologist workforce was examined. It was expected that increasing specialty care volume, resident staff, and facility complexity would be associated with increasing urologist workforce.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize VHA urology patients and urologist workforce within each regional VISN and its facilities. To better understand the relationship between case mix and urologist workforce, facilities were sorted according to MCG and characterized the unique urology patients, urologists, and residents at each level. Analysis of variance was used to test whether increasing MCG was associated with a higher number of urology patient caseloads. Multivariable linear regression models were then used to determine whether complexity was associated with urologist workforce after adjusting for resident and patient volume.

Related: Antibiotic Therapy and Bacterial Resistance in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury

Multilevel regression modeling, an extension of linear regression modeling suitable for partitioning the variation in an outcome variable attributable to different levels (ie, facility and VISN), was used to examine whether variation in the urologist workforce was primarily based at the facility or regional VISN level.6 This approach accounted for the potentially correlated nature of the data (ie, multiple facilities within each VISN) by incorporating a VISN-level random effect in the model. A random intercept model with no explanatory variables, known as an empty model, was used as the primary model.6 The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) corresponding to the estimated variance components from the empty model was calculated to determine the portion of the total variation in unadjusted urologist workforce that occurs between VISNs.7 Prostate cancer caseload was then included to test whether allocation seemed to be driven by clinical need or other regional factors.

All analyses were performed using STATA, Version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and all testing was 2-sided. The probability of a type I error was set at .05. This study protocol was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Research and Development Committee and Institutional Review Board.

Results

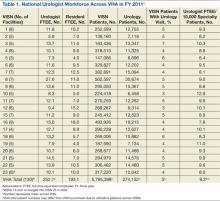

Nearly 1 in 20 VHA patients (n = 274,152) were evaluated in a urology clinic at least once in FY 2011. It was found that 252.7 FTEE and 193.1 residents comprised the VHA urologist workforce (Table 1). Marked regional variation was found in unadjusted urologist staffing at both the facility and VISN levels. The urologist workforce ranged from 0.17 to 5.91 FTEEs across the 130 VHA facilities. At the VISN level, staffing varied over 5-fold (5.8 FTEEs in VISN 2 to 27.6 FTEEs in VISN 8).

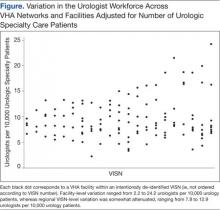

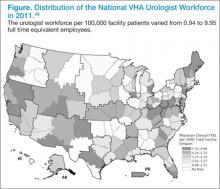

Variation in the VHA urologist workforce distribution persisted even after standardizing by patient volume. The urologist workforce continued to vary from 0.94 to 9.95 FTEEs per 100,000 facility patients. This was even more dramatic when adjusted for volume of unique urology patients, ranging from 2.2 to 24.2 FTEE urologists per 10,000 urology patients (Figure).5 From the specialist perspective, each might serve 18 to 64 newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer annually, depending on the VISN.

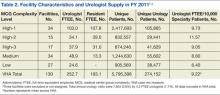

Forty percent of urologists were located in 34 of the most complex facilities (Table 2). Urology patient caseload was associated with facility complexity in univariate analysis (P < .001). In the adjusted multivariable model, increasing facility complexity was associated with increasing urologist workforce (P < .001) as well as resident staffing (P < .001), but not with urology patient caseload (P = .27). The empty multilevel model indicated that 27.3% of variation in unadjusted urologist workforce (ICC = 0.273, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.098-0.448) was attributable to differences at the regional network level. After adjustment for VISN prostate cancer caseload, this decreased to 24.8% (ICC = 0.248; 95% CI, 0.076-0.419).

Discussion

The VHA urologist workforce served over 250,000 patients in FY 2011, and a substantial variation in workforce distribution at the facility and VISN levels was identified in this study. After adjusting for prostate cancer caseload as a proxy for clinical demand, there was some imbalance of urology specialists across regional networks, though most workforce variation occurred within networks in this integrated delivery system. Based on these findings, VHA specialty care initiatives should likely focus within regional networks rather than pursue electronic efforts nationally to improve specialty care access for patients and PCPs.

Regional variation in the VHA urologist workforce was expected, given a limited national supply of urologists and specialist preferences toward metropolitan areas.2-4 Overcoming this maldistribution has important implications for outcomes in many urologic disease processes.8-10 For example, counties with ≥ 1 urologist have up to a 20% reduction in bladder and prostate cancer-related mortality compared with those without a urologist.4 Moreover, the number of veterans with known urologic needs or currently receiving urologic specialty care likely significantly undercounts the total number who could benefit from this care. This is particularly true for facilities with fewer urology resources where patients may be less likely to get a referral, or if they are referred, it is likely outside VHA, creating fragmented care and potentially higher cost.

Understanding the urology workforce distribution, coupled with its sophisticated nationwide EMR, VHA has a unique opportunity to transform how urologic specialty care is delivered without moving around the current workforce. Based on these findings, the system could redistribute resources within each region to meet growing specialty care needs through telemedicine.

At least 2 innovative approaches are underway that might serve the system’s urology care needs: e-consults and the Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) video teleconsulting and education project.11,12 The first allows PCPs to request specialist review of the EMR, interpretation of the specific problem, and recommendation for a plan of care, which may or may not include a specialist visit.1,13 The second involves video conferences, which allow multiple PCPs from less complex facilities or rural areas to present cases to specialists from tertiary medical centers for real-time consultation and case-based learning. These initiatives could take advantage of the facility-based variation in urologist workforce by linking facilities with relatively generous urology resources with those with fewer resources to meet the needs of each region’s population and their PCPs while minimizing travel and wait times.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, FY 2011 data were used; notably, the VHA urologist workforce remained relatively stable from 2008 through 2011. Second, characteristics of individual VHA urologists, clinical productivity, and skill level were not examined. However, a 2008 study found that nearly all VHA urologists are board certified, mitigating skill level concerns.14 Third, it is possible that demand is partially driven by existence of resources, and there may be patients who might benefit from urologic care but who are not yet diagnosed. The analysis is conservative in this regard, in that demand may be greater than what was detected using the selected study methods. Last, this study examined specialist workforce within a single system. However, ensuring specialist resources are well distributed is a concern for most health systems, particularly in light of recent policy efforts, including accountable care organizations.15

Conclusion

Much of the variation in the VHA urologist workforce exists at the facility rather than the regional level. Optimizing the distribution of these specialty care resources could be achieved through novel care delivery models within each regional network that are well-aligned with current VHA initiatives. Successfully utilizing this workforce distribution has the potential to improve urologic care for veterans across the country and could be applied to improve access to all types of specialists in underserved and understaffed areas.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Skolarus is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 12-171).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Graham GD; Office of Specialty Care Transformation, Department of Veterans Affairs Patient Care Services. Specialty care transformation initiatives. http://www.pva.org/atf/cf/%7BCA2A0FFB-6859 -4BC1-BC96-6B57F57F0391%7D/Friday_Graham_Specialty%20Care%20Transformation%20Initiatives.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed February 3, 2015.

2. Neuwahl S, Thompson K, Fraher E, Ricketts T. HPRI data tracks. Urology workforce trends. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2012;97(1):46-49.

3. Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol. 2009;181(2):760-765; discussion 765-766.

4. Odisho AY, Cooperberg MR, Fradet V, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Urologist density and county-level urologic cancer mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2499-2504.

5. Fiscal Year 2011 VHA Physician Workforce & Support Staff Data. VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, & Staffing Website. https://opes.vscc.med.va.gov. Published December 2011.

6. Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc;1999.

7. Krein SL, Hofer TP, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Whom should we profile? Examining diabetes care practice variation among primary care providers, provider groups, and health care facilities. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1159-1180.

8. Weiner DM, McDaniel R, Lowe FC. Urologic manpower issues for the 21st century: Assessing the impact of changing population demographics. Urology. 1997;49(3):335-342.

9. Gee WF, Holtgrewe HL, Albertsen PC, et al. Subspecialization, recruitment and retirement trends of American urologists. J Urol. 1998;159(2): 509-511.

10. McCullough DL. Manpower needs in urology in the twenty-first century. Urol Clin North Am. 1998;25(1):15-22.

11. Saifu HN, Asch SM, Goetz MB, et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):207-212.

12. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

13. Hysong SJ, Esquivel A, Sittig DF, et al. Towards successful coordination of electronic health record based-referrals: A qualitative analysis. Implement Sci. 2011;6:84.

14. Tyson MD, Lerner LB. Profile of the veterans affairs urologist: Results from a national survey. J Urol. 2008;180(4):1460-1462.

15. Landon BE, Roberts DH. Reenvisioning specialty care and payment under global payment systems. JAMA. 2013;310(4):371-372.

The VHA is the nation’s largest integrated health care delivery system, providing comprehensive medical care to about 6 million patients annually. In addition to revolutionizing its primary care delivery through widespread implementation of patient-centered medical homes (Patient Aligned Care Teams), the VHA is also transforming its specialty care delivery through use of its specialist workforce and innovative technologies, such as telemedicine and electronic consultations (e-consults).1

VHA specialty care is currently distributed using a hub and spoke model within larger regional networks spanning the U.S. This approach helps overcome geographic variation in specialist workforce (eg, predilection for metropolitan areas) but limits specialty care access for patients and primary care providers (PCPs) due to distance barriers.2-4 With the VHA electronic medical record (EMR) system, it is now feasible to send expertise electronically across the system (eg, e-consult). Whether this should occur at the regional VISN or national level to smooth out variation in specialist workforce depends in part on current specialist distribution within and across regions.

Related: Recurrent Multidrug Resistant Urinary Tract Infections in Geriatric Patients

Hand in hand with an aging veteran population is a growing clinical demand for urologic specialty care to treat urinary incontinence, prostate enlargement, and prostate cancer. Unfortunately, over 60% of U.S. counties lack a urologist, creating troublesome workforce issues.3 For these reasons, this study analyzed existing administrative data to understand regional variations in the distribution of and demands for the VHA urologist workforce. This study tested whether workforce distribution is balanced or imbalanced across regional networks, in part to inform whether the VHA should offer electronic or other national access to its urologic specialty care.

Methods

Fiscal year (FY) 2011 Specialty Physician Workforce Annual Report data from the VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing was used to characterize the distribution and concentration of urologists at 130 VHA facilities.5 The annual report provided a longitudinal management tool for reporting clinical productivity, efficiency, and staffing, and included benchmark data for each facility (eg, physician workforce, annual patient visits).

Demand for Urologic Specialty Care

The number of unique urology patients from the report was used as one approach to the demand for VHA urologic specialty care. This measure represented the number of unique patients evaluated in a urology clinic at least once over the FY. The number of newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer in calendar year 2010 within each VISN was also used as a more discrete measure of regional urologic care demand. Whereas care for other common urologic conditions, such as incontinence or prostate enlargement, may or may not be referred (ie, latent demand), prostate cancer care consistently involves urologists and is more specific for caseload.

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Because each VISN covered a relatively large geographic area, most with roughly equivalent numbers of facilities, there was no a priori reason to expect a difference in urologic workload and consequently urologic workforce between networks. On the other hand, within networks one might expect that urologists would be concentrated in hospitals that have more complicated patient cases, because the hospitals serve a tertiary or referral role. Yet even within a network, significant imbalances in specialist supply might require creative solutions to maintain adequate access of patients and PCPs to specialists.

Urologist Workforce

The full-time equivalent employee (FTEE) variable for urologic specialty care from the 2011 annual report was used as the primary outcome measure for urology workforce.5 This facility-level measure represented the clinical time urologists spent in direct patient care at each facility. It included the clinical effort of full-time as well as contract physicians and was also reported as an aggregate measure at the regional VISN level. Urologist workforce at the VISN level was the sum of all urologist FTEEs within its facilities. Adjusted rates also were provided (eg, FTEE/10,000 urology patients).

Other Workforce Factors

Also examined as covariates in the analysis were other measures related to urologist workforce. As the nation’s largest provider of graduate medical education, urology residents rotate through many VHA facilities, contributing to the workforce totals. For this reason, resident FTEE was examined as an independent variable in this study.

Understanding facility complexity (ie, case mix) was also essential for rational allocation of specialty care resources, as demand generally increases with increasing case mix. Therefore, a medical center group (MCG) case mix measure of complexity and its relationship with urologist workforce was examined. It was expected that increasing specialty care volume, resident staff, and facility complexity would be associated with increasing urologist workforce.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize VHA urology patients and urologist workforce within each regional VISN and its facilities. To better understand the relationship between case mix and urologist workforce, facilities were sorted according to MCG and characterized the unique urology patients, urologists, and residents at each level. Analysis of variance was used to test whether increasing MCG was associated with a higher number of urology patient caseloads. Multivariable linear regression models were then used to determine whether complexity was associated with urologist workforce after adjusting for resident and patient volume.

Related: Antibiotic Therapy and Bacterial Resistance in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury

Multilevel regression modeling, an extension of linear regression modeling suitable for partitioning the variation in an outcome variable attributable to different levels (ie, facility and VISN), was used to examine whether variation in the urologist workforce was primarily based at the facility or regional VISN level.6 This approach accounted for the potentially correlated nature of the data (ie, multiple facilities within each VISN) by incorporating a VISN-level random effect in the model. A random intercept model with no explanatory variables, known as an empty model, was used as the primary model.6 The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) corresponding to the estimated variance components from the empty model was calculated to determine the portion of the total variation in unadjusted urologist workforce that occurs between VISNs.7 Prostate cancer caseload was then included to test whether allocation seemed to be driven by clinical need or other regional factors.

All analyses were performed using STATA, Version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and all testing was 2-sided. The probability of a type I error was set at .05. This study protocol was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Research and Development Committee and Institutional Review Board.

Results

Nearly 1 in 20 VHA patients (n = 274,152) were evaluated in a urology clinic at least once in FY 2011. It was found that 252.7 FTEE and 193.1 residents comprised the VHA urologist workforce (Table 1). Marked regional variation was found in unadjusted urologist staffing at both the facility and VISN levels. The urologist workforce ranged from 0.17 to 5.91 FTEEs across the 130 VHA facilities. At the VISN level, staffing varied over 5-fold (5.8 FTEEs in VISN 2 to 27.6 FTEEs in VISN 8).

Variation in the VHA urologist workforce distribution persisted even after standardizing by patient volume. The urologist workforce continued to vary from 0.94 to 9.95 FTEEs per 100,000 facility patients. This was even more dramatic when adjusted for volume of unique urology patients, ranging from 2.2 to 24.2 FTEE urologists per 10,000 urology patients (Figure).5 From the specialist perspective, each might serve 18 to 64 newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer annually, depending on the VISN.

Forty percent of urologists were located in 34 of the most complex facilities (Table 2). Urology patient caseload was associated with facility complexity in univariate analysis (P < .001). In the adjusted multivariable model, increasing facility complexity was associated with increasing urologist workforce (P < .001) as well as resident staffing (P < .001), but not with urology patient caseload (P = .27). The empty multilevel model indicated that 27.3% of variation in unadjusted urologist workforce (ICC = 0.273, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.098-0.448) was attributable to differences at the regional network level. After adjustment for VISN prostate cancer caseload, this decreased to 24.8% (ICC = 0.248; 95% CI, 0.076-0.419).

Discussion

The VHA urologist workforce served over 250,000 patients in FY 2011, and a substantial variation in workforce distribution at the facility and VISN levels was identified in this study. After adjusting for prostate cancer caseload as a proxy for clinical demand, there was some imbalance of urology specialists across regional networks, though most workforce variation occurred within networks in this integrated delivery system. Based on these findings, VHA specialty care initiatives should likely focus within regional networks rather than pursue electronic efforts nationally to improve specialty care access for patients and PCPs.

Regional variation in the VHA urologist workforce was expected, given a limited national supply of urologists and specialist preferences toward metropolitan areas.2-4 Overcoming this maldistribution has important implications for outcomes in many urologic disease processes.8-10 For example, counties with ≥ 1 urologist have up to a 20% reduction in bladder and prostate cancer-related mortality compared with those without a urologist.4 Moreover, the number of veterans with known urologic needs or currently receiving urologic specialty care likely significantly undercounts the total number who could benefit from this care. This is particularly true for facilities with fewer urology resources where patients may be less likely to get a referral, or if they are referred, it is likely outside VHA, creating fragmented care and potentially higher cost.

Understanding the urology workforce distribution, coupled with its sophisticated nationwide EMR, VHA has a unique opportunity to transform how urologic specialty care is delivered without moving around the current workforce. Based on these findings, the system could redistribute resources within each region to meet growing specialty care needs through telemedicine.

At least 2 innovative approaches are underway that might serve the system’s urology care needs: e-consults and the Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) video teleconsulting and education project.11,12 The first allows PCPs to request specialist review of the EMR, interpretation of the specific problem, and recommendation for a plan of care, which may or may not include a specialist visit.1,13 The second involves video conferences, which allow multiple PCPs from less complex facilities or rural areas to present cases to specialists from tertiary medical centers for real-time consultation and case-based learning. These initiatives could take advantage of the facility-based variation in urologist workforce by linking facilities with relatively generous urology resources with those with fewer resources to meet the needs of each region’s population and their PCPs while minimizing travel and wait times.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, FY 2011 data were used; notably, the VHA urologist workforce remained relatively stable from 2008 through 2011. Second, characteristics of individual VHA urologists, clinical productivity, and skill level were not examined. However, a 2008 study found that nearly all VHA urologists are board certified, mitigating skill level concerns.14 Third, it is possible that demand is partially driven by existence of resources, and there may be patients who might benefit from urologic care but who are not yet diagnosed. The analysis is conservative in this regard, in that demand may be greater than what was detected using the selected study methods. Last, this study examined specialist workforce within a single system. However, ensuring specialist resources are well distributed is a concern for most health systems, particularly in light of recent policy efforts, including accountable care organizations.15

Conclusion

Much of the variation in the VHA urologist workforce exists at the facility rather than the regional level. Optimizing the distribution of these specialty care resources could be achieved through novel care delivery models within each regional network that are well-aligned with current VHA initiatives. Successfully utilizing this workforce distribution has the potential to improve urologic care for veterans across the country and could be applied to improve access to all types of specialists in underserved and understaffed areas.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Skolarus is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 12-171).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The VHA is the nation’s largest integrated health care delivery system, providing comprehensive medical care to about 6 million patients annually. In addition to revolutionizing its primary care delivery through widespread implementation of patient-centered medical homes (Patient Aligned Care Teams), the VHA is also transforming its specialty care delivery through use of its specialist workforce and innovative technologies, such as telemedicine and electronic consultations (e-consults).1

VHA specialty care is currently distributed using a hub and spoke model within larger regional networks spanning the U.S. This approach helps overcome geographic variation in specialist workforce (eg, predilection for metropolitan areas) but limits specialty care access for patients and primary care providers (PCPs) due to distance barriers.2-4 With the VHA electronic medical record (EMR) system, it is now feasible to send expertise electronically across the system (eg, e-consult). Whether this should occur at the regional VISN or national level to smooth out variation in specialist workforce depends in part on current specialist distribution within and across regions.

Related: Recurrent Multidrug Resistant Urinary Tract Infections in Geriatric Patients

Hand in hand with an aging veteran population is a growing clinical demand for urologic specialty care to treat urinary incontinence, prostate enlargement, and prostate cancer. Unfortunately, over 60% of U.S. counties lack a urologist, creating troublesome workforce issues.3 For these reasons, this study analyzed existing administrative data to understand regional variations in the distribution of and demands for the VHA urologist workforce. This study tested whether workforce distribution is balanced or imbalanced across regional networks, in part to inform whether the VHA should offer electronic or other national access to its urologic specialty care.

Methods

Fiscal year (FY) 2011 Specialty Physician Workforce Annual Report data from the VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing was used to characterize the distribution and concentration of urologists at 130 VHA facilities.5 The annual report provided a longitudinal management tool for reporting clinical productivity, efficiency, and staffing, and included benchmark data for each facility (eg, physician workforce, annual patient visits).

Demand for Urologic Specialty Care

The number of unique urology patients from the report was used as one approach to the demand for VHA urologic specialty care. This measure represented the number of unique patients evaluated in a urology clinic at least once over the FY. The number of newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer in calendar year 2010 within each VISN was also used as a more discrete measure of regional urologic care demand. Whereas care for other common urologic conditions, such as incontinence or prostate enlargement, may or may not be referred (ie, latent demand), prostate cancer care consistently involves urologists and is more specific for caseload.

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Because each VISN covered a relatively large geographic area, most with roughly equivalent numbers of facilities, there was no a priori reason to expect a difference in urologic workload and consequently urologic workforce between networks. On the other hand, within networks one might expect that urologists would be concentrated in hospitals that have more complicated patient cases, because the hospitals serve a tertiary or referral role. Yet even within a network, significant imbalances in specialist supply might require creative solutions to maintain adequate access of patients and PCPs to specialists.

Urologist Workforce

The full-time equivalent employee (FTEE) variable for urologic specialty care from the 2011 annual report was used as the primary outcome measure for urology workforce.5 This facility-level measure represented the clinical time urologists spent in direct patient care at each facility. It included the clinical effort of full-time as well as contract physicians and was also reported as an aggregate measure at the regional VISN level. Urologist workforce at the VISN level was the sum of all urologist FTEEs within its facilities. Adjusted rates also were provided (eg, FTEE/10,000 urology patients).

Other Workforce Factors

Also examined as covariates in the analysis were other measures related to urologist workforce. As the nation’s largest provider of graduate medical education, urology residents rotate through many VHA facilities, contributing to the workforce totals. For this reason, resident FTEE was examined as an independent variable in this study.

Understanding facility complexity (ie, case mix) was also essential for rational allocation of specialty care resources, as demand generally increases with increasing case mix. Therefore, a medical center group (MCG) case mix measure of complexity and its relationship with urologist workforce was examined. It was expected that increasing specialty care volume, resident staff, and facility complexity would be associated with increasing urologist workforce.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize VHA urology patients and urologist workforce within each regional VISN and its facilities. To better understand the relationship between case mix and urologist workforce, facilities were sorted according to MCG and characterized the unique urology patients, urologists, and residents at each level. Analysis of variance was used to test whether increasing MCG was associated with a higher number of urology patient caseloads. Multivariable linear regression models were then used to determine whether complexity was associated with urologist workforce after adjusting for resident and patient volume.

Related: Antibiotic Therapy and Bacterial Resistance in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury

Multilevel regression modeling, an extension of linear regression modeling suitable for partitioning the variation in an outcome variable attributable to different levels (ie, facility and VISN), was used to examine whether variation in the urologist workforce was primarily based at the facility or regional VISN level.6 This approach accounted for the potentially correlated nature of the data (ie, multiple facilities within each VISN) by incorporating a VISN-level random effect in the model. A random intercept model with no explanatory variables, known as an empty model, was used as the primary model.6 The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) corresponding to the estimated variance components from the empty model was calculated to determine the portion of the total variation in unadjusted urologist workforce that occurs between VISNs.7 Prostate cancer caseload was then included to test whether allocation seemed to be driven by clinical need or other regional factors.

All analyses were performed using STATA, Version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and all testing was 2-sided. The probability of a type I error was set at .05. This study protocol was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Research and Development Committee and Institutional Review Board.

Results

Nearly 1 in 20 VHA patients (n = 274,152) were evaluated in a urology clinic at least once in FY 2011. It was found that 252.7 FTEE and 193.1 residents comprised the VHA urologist workforce (Table 1). Marked regional variation was found in unadjusted urologist staffing at both the facility and VISN levels. The urologist workforce ranged from 0.17 to 5.91 FTEEs across the 130 VHA facilities. At the VISN level, staffing varied over 5-fold (5.8 FTEEs in VISN 2 to 27.6 FTEEs in VISN 8).

Variation in the VHA urologist workforce distribution persisted even after standardizing by patient volume. The urologist workforce continued to vary from 0.94 to 9.95 FTEEs per 100,000 facility patients. This was even more dramatic when adjusted for volume of unique urology patients, ranging from 2.2 to 24.2 FTEE urologists per 10,000 urology patients (Figure).5 From the specialist perspective, each might serve 18 to 64 newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer annually, depending on the VISN.

Forty percent of urologists were located in 34 of the most complex facilities (Table 2). Urology patient caseload was associated with facility complexity in univariate analysis (P < .001). In the adjusted multivariable model, increasing facility complexity was associated with increasing urologist workforce (P < .001) as well as resident staffing (P < .001), but not with urology patient caseload (P = .27). The empty multilevel model indicated that 27.3% of variation in unadjusted urologist workforce (ICC = 0.273, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.098-0.448) was attributable to differences at the regional network level. After adjustment for VISN prostate cancer caseload, this decreased to 24.8% (ICC = 0.248; 95% CI, 0.076-0.419).

Discussion

The VHA urologist workforce served over 250,000 patients in FY 2011, and a substantial variation in workforce distribution at the facility and VISN levels was identified in this study. After adjusting for prostate cancer caseload as a proxy for clinical demand, there was some imbalance of urology specialists across regional networks, though most workforce variation occurred within networks in this integrated delivery system. Based on these findings, VHA specialty care initiatives should likely focus within regional networks rather than pursue electronic efforts nationally to improve specialty care access for patients and PCPs.

Regional variation in the VHA urologist workforce was expected, given a limited national supply of urologists and specialist preferences toward metropolitan areas.2-4 Overcoming this maldistribution has important implications for outcomes in many urologic disease processes.8-10 For example, counties with ≥ 1 urologist have up to a 20% reduction in bladder and prostate cancer-related mortality compared with those without a urologist.4 Moreover, the number of veterans with known urologic needs or currently receiving urologic specialty care likely significantly undercounts the total number who could benefit from this care. This is particularly true for facilities with fewer urology resources where patients may be less likely to get a referral, or if they are referred, it is likely outside VHA, creating fragmented care and potentially higher cost.

Understanding the urology workforce distribution, coupled with its sophisticated nationwide EMR, VHA has a unique opportunity to transform how urologic specialty care is delivered without moving around the current workforce. Based on these findings, the system could redistribute resources within each region to meet growing specialty care needs through telemedicine.

At least 2 innovative approaches are underway that might serve the system’s urology care needs: e-consults and the Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) video teleconsulting and education project.11,12 The first allows PCPs to request specialist review of the EMR, interpretation of the specific problem, and recommendation for a plan of care, which may or may not include a specialist visit.1,13 The second involves video conferences, which allow multiple PCPs from less complex facilities or rural areas to present cases to specialists from tertiary medical centers for real-time consultation and case-based learning. These initiatives could take advantage of the facility-based variation in urologist workforce by linking facilities with relatively generous urology resources with those with fewer resources to meet the needs of each region’s population and their PCPs while minimizing travel and wait times.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, FY 2011 data were used; notably, the VHA urologist workforce remained relatively stable from 2008 through 2011. Second, characteristics of individual VHA urologists, clinical productivity, and skill level were not examined. However, a 2008 study found that nearly all VHA urologists are board certified, mitigating skill level concerns.14 Third, it is possible that demand is partially driven by existence of resources, and there may be patients who might benefit from urologic care but who are not yet diagnosed. The analysis is conservative in this regard, in that demand may be greater than what was detected using the selected study methods. Last, this study examined specialist workforce within a single system. However, ensuring specialist resources are well distributed is a concern for most health systems, particularly in light of recent policy efforts, including accountable care organizations.15

Conclusion

Much of the variation in the VHA urologist workforce exists at the facility rather than the regional level. Optimizing the distribution of these specialty care resources could be achieved through novel care delivery models within each regional network that are well-aligned with current VHA initiatives. Successfully utilizing this workforce distribution has the potential to improve urologic care for veterans across the country and could be applied to improve access to all types of specialists in underserved and understaffed areas.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Skolarus is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 12-171).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Graham GD; Office of Specialty Care Transformation, Department of Veterans Affairs Patient Care Services. Specialty care transformation initiatives. http://www.pva.org/atf/cf/%7BCA2A0FFB-6859 -4BC1-BC96-6B57F57F0391%7D/Friday_Graham_Specialty%20Care%20Transformation%20Initiatives.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed February 3, 2015.

2. Neuwahl S, Thompson K, Fraher E, Ricketts T. HPRI data tracks. Urology workforce trends. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2012;97(1):46-49.

3. Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol. 2009;181(2):760-765; discussion 765-766.

4. Odisho AY, Cooperberg MR, Fradet V, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Urologist density and county-level urologic cancer mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2499-2504.

5. Fiscal Year 2011 VHA Physician Workforce & Support Staff Data. VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, & Staffing Website. https://opes.vscc.med.va.gov. Published December 2011.

6. Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc;1999.

7. Krein SL, Hofer TP, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Whom should we profile? Examining diabetes care practice variation among primary care providers, provider groups, and health care facilities. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1159-1180.

8. Weiner DM, McDaniel R, Lowe FC. Urologic manpower issues for the 21st century: Assessing the impact of changing population demographics. Urology. 1997;49(3):335-342.

9. Gee WF, Holtgrewe HL, Albertsen PC, et al. Subspecialization, recruitment and retirement trends of American urologists. J Urol. 1998;159(2): 509-511.

10. McCullough DL. Manpower needs in urology in the twenty-first century. Urol Clin North Am. 1998;25(1):15-22.

11. Saifu HN, Asch SM, Goetz MB, et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):207-212.

12. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

13. Hysong SJ, Esquivel A, Sittig DF, et al. Towards successful coordination of electronic health record based-referrals: A qualitative analysis. Implement Sci. 2011;6:84.

14. Tyson MD, Lerner LB. Profile of the veterans affairs urologist: Results from a national survey. J Urol. 2008;180(4):1460-1462.

15. Landon BE, Roberts DH. Reenvisioning specialty care and payment under global payment systems. JAMA. 2013;310(4):371-372.

1. Graham GD; Office of Specialty Care Transformation, Department of Veterans Affairs Patient Care Services. Specialty care transformation initiatives. http://www.pva.org/atf/cf/%7BCA2A0FFB-6859 -4BC1-BC96-6B57F57F0391%7D/Friday_Graham_Specialty%20Care%20Transformation%20Initiatives.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed February 3, 2015.

2. Neuwahl S, Thompson K, Fraher E, Ricketts T. HPRI data tracks. Urology workforce trends. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2012;97(1):46-49.

3. Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol. 2009;181(2):760-765; discussion 765-766.

4. Odisho AY, Cooperberg MR, Fradet V, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Urologist density and county-level urologic cancer mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2499-2504.

5. Fiscal Year 2011 VHA Physician Workforce & Support Staff Data. VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, & Staffing Website. https://opes.vscc.med.va.gov. Published December 2011.

6. Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc;1999.

7. Krein SL, Hofer TP, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Whom should we profile? Examining diabetes care practice variation among primary care providers, provider groups, and health care facilities. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1159-1180.

8. Weiner DM, McDaniel R, Lowe FC. Urologic manpower issues for the 21st century: Assessing the impact of changing population demographics. Urology. 1997;49(3):335-342.

9. Gee WF, Holtgrewe HL, Albertsen PC, et al. Subspecialization, recruitment and retirement trends of American urologists. J Urol. 1998;159(2): 509-511.

10. McCullough DL. Manpower needs in urology in the twenty-first century. Urol Clin North Am. 1998;25(1):15-22.

11. Saifu HN, Asch SM, Goetz MB, et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):207-212.

12. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

13. Hysong SJ, Esquivel A, Sittig DF, et al. Towards successful coordination of electronic health record based-referrals: A qualitative analysis. Implement Sci. 2011;6:84.

14. Tyson MD, Lerner LB. Profile of the veterans affairs urologist: Results from a national survey. J Urol. 2008;180(4):1460-1462.

15. Landon BE, Roberts DH. Reenvisioning specialty care and payment under global payment systems. JAMA. 2013;310(4):371-372.

Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer diagnosis among U.S. veterans.1 More than 12,000 veterans will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2014, to join more than 200,000 veteran survivors.1 Because its incidence increases with age and nearly half of veterans are aged ≥ 65 years, the clinical and economic burdens of prostate cancer are expected to increase.2 Fortunately, > 80% of these men will have local disease with 5-year cancer-specific survivals of 98%.3 Even among the small population of veterans whose disease returns after treatment, < 1 in 5 will die of prostate cancer within 10 years.4

Thus, most men live with prostate cancer and its sequelae rather than die of it, similar to other chronic diseases. In 2003, the VHA outlined a National Cancer Strategy, indicating priorities for quality cancer care and access to care for all veterans with cancer.5 Importantly, this directive recognized prostate cancer as a service-connected condition for men exposed to the herbicide Agent Orange.6 For all these reasons, understanding the delivery of prostate cancer survivorship care has tremendous cost and quality implications for the VHA.

SURVIVORSHIP CARE

Due to the extensive focus on screening and initial treatment, very little prostate cancer survivorship research exists either within or outside VHA. In fact, a 2011 literature review found that < 10 prostate cancer survivorship studies were published annually.7 Because long-term survival is increasingly common after any cancer diagnosis, better understanding cancer survivorship (ie, the chronic care following diagnosis and treatment) and the distinct needs of cancer survivors are central to cancer care quality.8,9

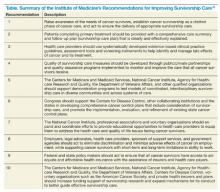

A 2005 breakthrough report from the Institute of Medicine, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, emphasized the distinct issues facing cancer survivors and called for an increased emphasis on cancer survivors and their care from both clinical and research perspectives (Table).10

Due to the expanding population of veteran prostate cancer survivors, this report has increasing relevance to VHA.11 For prostate cancer survivors in particular, up to 70% have persistent symptoms (eg, incontinence, impotence) with some symptoms persisting 15 years after treatment, indicating the need for ongoing care and similarity to other chronic diseases.12,13

Despite this growing need and the universal provider access to electronic medical records, VHA, like most other integrated delivery systems, does not have a systematic organizational approach to deal with its prostate cancer survivors, indicating a tremendous opportunity.

One recent proposal for supporting survivorship care in the VHA is a Patient-Aligned Specialty Team for oncology to provide comprehensive cancer care through tumor boards, multispecialty clinics, care coordinators/navigators, and patient education.14

Symptom Burden

The 3 usual approaches to treatment of prostate cancer are (1) surgery (radical prostatectomy); (2) radiation therapy (brachytherapy or external “beam” radiation); and (3) observation (watchful waiting and active surveillance).15-18 While some men do choose observation initially, ultimately many undergo some form of surgical or radiation treatment.19 Unfortunately, long-term adverse effects (AEs) of these treatments are common and vary by treatment type. Men may experience ongoing problems with urinary control (eg, urinary incontinence), sexual function (eg, impotence), hormonal (eg, fatigue, depression), and bowel function (eg, diarrhea and fecal incontinence) far beyond that of age-matched controls.13,15,20-27

Up to 75% of men report problems with erectile dysfunction after prostatectomy, compared with 25% who receive brachytherapy, and 40% who receive brachytherapy plus external beam radiation.20,22,26,28 Urinary problems include both incontinence and pain with urination, which may improve over time with medical and nonmedical management approaches.26,27 Among patients treated with radiation therapy, between 40% and 55% report urinary problems as long as 8 years posttreatment (incontinence and/or pain).26,27,29,30 Unlike surgery, radiation therapy is also associated with bowel problems posttreatment, including rectal urgency and diarrhea.25,31

Although the greatest symptom burden and associated reduction in quality of life (QOL) occurs initially following treatment, many prostate cancer survivors experience considerable symptom burden for years following treatment.21,22,26,32-35 This persistence of symptoms is documented among thousands of patients after prostate cancer treatment, most of which are nonveterans. For example, among men with prostate cancer and no sexual, urinary, or hormonal problems at baseline, 9% to 83% reported severe problems in at least 1 domain 3 years after treatment with surgery or radiation.36

Gore and colleagues demonstrated persistent symptoms among 475 prostate cancer patients for up to 48 months following initial treatment.27 The Michigan Prostate Cancer Survivor Study, a registry-based survey of 2,500 prostate cancer survivors responding about 9 years postdiagnosis, found that up to 70% reported ongoing problems with AEs, some of whom were more than 15 years removed from primary treatment.12 Addressing these symptoms through medical and self-management approaches is one way to reduce their impact and improve QOL among prostate cancer survivors.

Despite the size of the veteran prostate cancer survivor population, most research documenting symptom burden and reduced QOL is from nonveterans. Because veterans often experience greater disease burden than that of the general population, their symptom burden would be expected to be similar or greater than that reported among nonveterans. Although there has been no comprehensive assessment of symptom burden across the VHA as a whole, research to understand optimal approaches to support veteran prostate cancer survivors with self- and medical management of their treatment related symptoms seems warranted.

Self-Management

Though there have been no comprehensive self-management interventions directed to help survivors limit the impact of prostate cancer treatment sequelae in everyday life, evidence suggests that such an intervention is likely to have a positive impact.37 For example, urinary symptoms can be self-managed through a variety of approaches, including emptying the bladder at regular intervals before it gets too full and pelvic floor (ie, Kegel) exercises to help decrease urinary leakage episodes. In fact, a randomized trial demonstrated a 50% decrease in incontinence episodes among prostate cancer survivors who used pelvic floor muscle training and bladder control strategies.38 A recent systematic review suggests that exercise, another self-management strategy, improves incontinence, energy level, body constitution, and QOL after treatment for prostate cancer.37 Exercise among prostate cancer survivors is also associated with decreased prostate cancer-specific and overall mortality.39

For sexual function after prostate cancer treatment, minimizing tobacco and excessive alcohol use and communicating with partners about feelings and sex are self-management strategies for improving sexual relationships.40 Avoiding spicy and greasy foods, coffee and alcohol, and staying well-hydrated may help limit the adverse bowel effects of radiation (ie, radiation proctitis) among prostate cancer survivors.41 However, there are no systematic mechanisms to share these strategies with veterans or nonveterans.

Medical Management

Recommendations for the medical management of prostate cancer-related AEs have recently been updated by the Michigan Cancer Consortium’s Prostate Cancer Action Committee and are available at www.prostatecancerdecision.org.42 Originally developed in 2009, these recommendations were directed toward the management of common posttreatment problems to minimize their impact on men who have been treated for prostate cancer, their families, caregivers, partners, and primary care providers (PCPs).

The recommendations combine expert opinion and evidence-based strategies for identifying recurrence and managing specific symptoms, including erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, bowel problems, hot flashes, bone health, gynecomastia, relationship issues, and metabolic syndrome. The increasing recognition that comprehensive, point-of-care resources are needed to direct survivorship care is fueling tremendous efforts targeting primary and specialty care providers from many major cancer stakeholder organizations (ie, American Cancer Society, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, etc).43-45

Primary care providers often consult prostate cancer specialists (urologists and radiation and medical oncologists) for assistance in managing prostate cancer survivors.46 However, it is not clear whether the supply of cancer specialists is capable of meeting the increasing needs of cancer survivors and their PCPs.47 VHA urologists vary tremendously in their regional availability from < 1 per 100,000 patients in Little Rock, Arkansas, to > 10 urologists per 100,000 patients in New York City.48 Similar variation exists for medical oncologists in the VHA. For prostate cancer, the urologist workforce impacts screening rates and cancer-related mortality.49,50 Yet how this workforce variation influences quality of survivorship care, particularly among PCPs dependent on specialist expertise, is unknown.

A better understanding of these relationships will help inform whether interventions to improve survivorship quality of care need to target PCPs with less access to prostate cancer specialists (eg, rural providers through telemedicine initiatives); survivorship care coordination at sites with more cancer specialists; or other potential barriers, such as knowledge gaps pertaining to AE evaluation and management. Each of these barriers to optimal care would be addressed through different interventions.

The long natural history of prostate cancer coupled with the number of survivors basically ensures that PCPs are faced with managing these men and their symptom burdens.51 However, it is often undecided who has primary responsibility for survivorship care.52,53 When queried regarding responsibility for prostate cancer survivorship care, about half of PCPs from one state-based survey felt that it was appropriate for either the cancer specialist or themselves to provide such care.12 Another study revealed high discordance among cancer specialists and PCPs regarding who should provide follow-up care, cancer screening, and general preventive care.54 Without clear role identification, poor communication between primary and specialty care fosters fragmented, expensive, and even poor quality survivorship care.55

Optimizing the delivery of survivorship care among cancer specialists and PCPs is also difficult, because comprehensive prostate cancer survivorship guidelines that might delineate responsibilities and recommend referral practices are just becoming available. In fact, the American Cancer Society just released its Prostate Cancer Survivorship Guidelines in June 2014.10,56,57 Primary care providers may be willing to take on increased responsibility for survivorship care with appropriate specialist support, including timely access to specialist evaluation.54,58 Moreover, PCPs are usually better at supporting cancer survivors’ general health as well.51,58 Therefore, defining the interface between PCPs, their medical home (ie, Patient-Aligned Care Team), and the limited supply of cancer specialists is necessary to streamline information exchange and care transitions.59

Understanding symptom management (eg, incontinence, impotence) across this interface is also critical to the design and implementation of survivorship quality improvement interventions. Promoting clear responsibilities for prostate-specific antigen surveillance, symptom management, and bone density testing for men treated with androgen deprivation therapy across the primary-specialty care interface is a potential starting point.

Transformative Tools

Whether targeting cancer care or not, quality improvement interventions often lack insight into the causal mechanisms by which they effect change.60-62 This is particularly true for interventions targeting clinician behavior change, such as improving uptake of evidence-based practice.63,64 For example, the effectiveness of audit with feedback interventions to improve guideline adherence ranges from 1% to 16%.65-69 The same intervention can vary in its effectiveness, depending on context.70-72 Barriers and enablers that vary by provider, facility, and other contextual factors (eg, workforce, location) contribute to this variable effectiveness.73-79 For this reason, a guiding theoretical framework is useful to understand an intervention’s transferability among different settings, as well as to ensure comprehensive assessment of the factors that can prevent uptake of evidence-based practice.80-83 For example, a theoretical framework might provide insight into how causal mechanisms of an intervention to improve cancer survivorship care might vary in a community-based outpatient clinic vs a tertiary center.84-86

A guiding theoretical framework is even more useful when used to design quality improvement interventions.82,83,87,88 Mapping barriers to theoretical constructs, and theoretical constructs to interventions to facilitate clinician behavior change can assist in planning strategies for effective implementation across a range of settings.88 While psychological theories like the Theoretical Domains Framework and Theory of Planned Behavior are pertinent for individual behavior change, understanding how best to implement interventions targeted at the facility level requires a broader perspective focused on context.83,88-92

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) provides a comprehensive, practical taxonomy for understanding important organizational, individual, and intervention characteristics to consider during an implementation process.75,76 The CFIR framework provides the broader contextual milieu contributing to the quality of survivorship care at the facility level across 5 domains: (1) intervention characteristics—evidence, complexity, relative advantage; (2) outer setting—peer pressure, external policies; (3) inner setting—structural characteristics, readiness for implementation, culture; (4) individual characteristics—knowledge about intervention, self-efficacy; and (5) process—planning, engaging stakeholders, champions, execution.

Using both individual and organizational constructs to effectively characterize the relationships, needs, intentions, and organizational characteristics of primary and cancer care providers throughout VHA will be key to designing successful interventions to broadly ensure quality survivorship care. The best interventions to improve survivorship care will likely vary across facilities based on contextual factors such as cancer specialist availability, facility characteristics, and the current delivery system for survivorship care.

Intervention modalities currently being used by the VHA Office of Specialty Care Transformation to improve access to specialty care are indeed transformative tools to optimize the quality of survivorship care. The latter builds on a successful approach developed and widely used in New Mexico, which makes the expertise of academic specialists at the University of New Mexico available throughout the state, using video teleconferencing.93,94 The opportunities for video-enabled interaction between specialists and PCPs in VHA, both in consultation about specific patients and in educational sessions to enhance PCP knowledge and self-efficacy in managing patients requiring specialty knowledge, are revolutionary for cancer care.93,95

Conclusions

Due to the expanding population of veteran prostate cancer survivors, improving their QOL by ensuring proper cancer surveillance, effectively managing their treatment complications and transitions of cancer care will reduce risk and provide timely management of symptoms and disease recurrence.

Understanding how variation in the VHA cancer specialist workforce impacts the quality of cancer survivorship care is a critical step towards optimizing veteran cancer care. Through this understanding, communication between PCPs, PACT, and cancer specialists can be improved via theory-based quality improvement tools to address gaps in the quality of prostate and other VHA cancer survivorship care. Interventions designed to enhance PCP self-efficacy in delivering high-quality prostate cancer survivor care may improve job satisfaction among PCPs and specialists.

Clarifying issues in the delivery of optimal prostate cancer survivorship care may inform models for other cancer survivorship care in the VHA. The contextual factors contributing to a VHA facility’s performance for prostate cancer survivorship care may be very relevant to the facility’s performance for other types of cancer survivorship care. A facility’s primary care organizational structure, cancer specialist workforce, and oncology-specific facility characteristics vary little across cancer types, suggesting that a better understanding of how to improve PSA surveillance for prostate cancer, the most common cancer treated in the VHA, should apply to carcinoembryonic antigen surveillance for colon cancer, hematology studies for lymphoma, and the surveillance of other malignancies in the VHA.96,97

The VHA National Cancer Strategy stressed the importance of meeting or exceeding accepted national standards of quality cancer care. Therefore, understanding the relationship between quality of cancer survivorship care and the cancer specialist workforce and its interface with primary care is critical to this goal, as is elucidation of the other barriers preventing optimal care. Last, embracing VHA’s latest telemedicine initiatives, including video teleconferencing to improve prostate cancer care, has the potential to transform this system into a national leader in prostate cancer survivorship care.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article. Dr. Skolarus is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award - 2 (CDA 12-171). Drs. Hawley (PI) and Skolarus (Co-I) are supported by VA HSR&D IIR (12-116).

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect an endorsement by or opinion of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications, the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drug combinations–including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects–before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry (VACCR) [intranet database]. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; 1995.

2. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of Veterans: 2009. Data from the American Community Survey. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2009_FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2014.

3. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER Website. http://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed July 23, 2014.

4. Uchio EM, Aslan M, Wells CK, Calderone J, Concato J. Impact of biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer among US veterans. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1390-1395.

5. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA DIRECTIVE 2003-034. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration Website. http://www1.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=261. Accessed July 23, 2014.

6. Chamie K, DeVere White RW, Lee D, Ok JH, Ellison LM. Agent Orange exposure, Vietnam War veterans, and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(9):2464-2470.

7. Harrop JP, Dean JA, Paskett ED. Cancer survivorship research: A review of the literature and summary of current NCI-designated cancer center projects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):2042-2047.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer survivors—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(9):269-272.

9. Ganz PA. Survivorship: Adult cancer survivors. Prim Care. 2009;36(4):721-741.

10. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Translation. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

11. Moye J, Schuster JL, Latini DM, Naik AD. The future of cancer survivorship care for veterans. Fed Pract. 2010;27(3):36-43.

12. Darwish-Yassine M, Berenji M, Wing D, et al. Evaluating long-term patient-centered outcomes following prostate cancer treatment: findings from the Michigan Prostate Cancer Survivor study. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(1):121-130.

13. Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1250-1261.

14. Kelley M. VA Proposes Team-Based Model for Prostate Cancer Care. U.S. Medicine Website. http://www.usmedicine.com/agencies/department-of-veterans-affairs/va-proposes-team-based-model-for-prostate-cancer-care. Published May 2013. Accessed April 28, 2014.

15. Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, et al; Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study No. 4. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(19):1977-1984.

16. Skolarus TA, Miller DC, Zhang Y, Hollingsworth JM, Hollenbeck BK. The delivery of prostate cancer care in the United States: Implications for delivery system reform. J Urol. 2010;184(6):2279-2284.

17. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Prostate Cancer, Version 2.2014. NCCN Website. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2014.

18. Bolla M, Collette L, Blank L, et al. Long-term results with immediate androgen suppression and external irradiation in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer (an EORTC study): a phase III randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):103-106.

19. Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, Nam R, Mamedov A, Loblaw A. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):126-131.

20. Alemozaffar M, Regan MM, Cooperberg MR, et al. Prediction of erectile function following treatment for prostate cancer. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1205-1214.

21. Dandapani SV, Sanda MG. Measuring health-related quality of life consequences from primary treatment for early-state prostate cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2008;18(1):67-72.

22. Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, et al; SPCG-4 Investigators. Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Proste Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):891-899.

23. Johansson E, Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Onelöv E, Johansson JE, Steineck G; Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study No 4. Time, symptom burden, androgen deprivation, and self-assessed quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Randomized Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4) clinical trial. Eur Urol. 2009;55(2):422-430.

24. Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adofsson J, et al; Scandanavian Prostatic Cancer Group Study Number 4. Quality of life after radial prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):790-796.

25. Penson DF, Litwin MS. Quality of life after treatment for prostate cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2003;4(3):185-195.

26. Ferrer M, Suárez JF, Guedea F, et al; Multicentric Spanish Group of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. Health-related quality of life 2 years after treatment with radical prostatectomy, prostate brachytherapy, or external beam radiotherapy in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiation Oncology Bio Phys. 2008;72(2):421-432.

27. Gore JL, Kwan L, Lee SP, Reiter RE, Litwin MS. Survivorship beyond convalescence: 48-month quality-of-life outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(12):888-892.

28. Miller DC, Wei JT, Dunn RL, et al. Use of medications or devices for erectile dysfunction among long-term prostate cancer treatment survivors: potential influence of sexual motivation and/or indifference. Urology. 2006;68(1):166-171.

29. Wilt TJ, Shamliyan TA, Taylor BC, MacDonald R, Kane RL. Association between hospital and surgeon radical prostatectomy volume and patient outcomes: A systematic review. J Urol. 2008;180(3):820-828; discussion 828-829.

30. Miller DC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, et al. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: Health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy, external radiation, and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2772-2780.

31. Michaelson MD, Cotter SE, Gargollo PC, Zietman AL, Dahl DM, Smith MR. Management of complications of prostate cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(4):196-213.

32. Potosky AL, Legler J, Albertsen PC, et al. Health outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(19):1582-1592.

33. Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, et al. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: The prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(18):1358-1367.

34. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sandler HM, et al. Comprehensive comparison of health-related quality of life after contemporary therapies for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(2):557-566.

35. Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Fuerestein M. It’s not over when it’s over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40(2):163-181.

36. Pardo Y, Guedea F, Aguiló F, et al. Quality-of-life impact of primary treatments for localized prostate cancer in patients without hormonal treatment [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):779]. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4687-4696.

37. Baumann FT, Zoph EM, Bloch W. Clinical exercise interventions in prostate cancer patients—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2011;20(2):221-233.

38. Goode PS, Burgio KL, Johnson TM II, et al. Behavioral therapy with or without biofeedback and pelvic floor electrical stimulation for persistent postprostatectomy incontinence: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(2):151-159.

39. Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Chan JM. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the health professionals follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):726-732.

40. Meldrum DR, Gambone JC, Morris MA, Ignarro LJ. A multifaceted approach to maximize erectile function and vascular health. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2514-2520.

41. National Cancer Institute. Gastrointestinal Complications. NCCN Website. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/gastrointestinalcomplications/HealthProfessional. Accessed June 27, 2014.

42. Michigan Cancer Consortium. Michigan Cancer Consortium Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care. Prostate Cancer Decision Website. http://www.prostatecancerdecision.org/PDFs/Algorithms2013/RecommProstateCancerCare-09182013.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2014.

43. Cowens-Alvarado R, Sharpe K, Pratt-Chapman M, et al. Advancing survivorship care through the National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center: Developing American Cancer Society guidelines for primary care providers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(3):147-150.

44. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Cancer Survivorship. American Society of Clinical Cancer Website. http://www.asco.org/practice-research

/cancer-survivorship. Accessed May 1, 2014.

45. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Survivorship. V1. 2014. NCCN Website. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#survivorship. Accessed April 24, 2014.

46. Skolarus TA, Holmes-Rovner M, Northouse LL, et al. Primary care perspectives on prostate cancer survivorship: Implications for improving quality of care. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(6):727-732.